Abstract

Although it is well established that many glutamatergic neurons sequester Zn2+ within their synaptic vesicles, the physiological significance of synaptic Zn2+ remains poorly understood. In experiments performed in a Zn2+-enriched auditory brainstem nucleus -- the dorsal cochlear nucleus -- we discovered that synaptic Zn2+ and GPR39, a putative metabotropic Zn2+-sensing receptor (mZnR), are necessary for triggering the synthesis of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). The postsynaptic production of 2-AG, in turn, inhibits presynaptic probability of neurotransmitter release, thus shaping synaptic strength and short-term synaptic plasticity. Zn2+-induced inhibition of transmitter release is absent in mutant mice that lack either vesicular Zn2+ or the mZnR. Moreover, mass spectrometry measurements of 2-AG levels reveal that Zn2+-mediated initiation of 2-AG synthesis is absent in mice lacking the mZnR. We reveal a previously unknown action of synaptic Zn2+: synaptic Zn2+ inhibits glutamate release by promoting 2-AG synthesis.

Introduction

Zn2+ is, after iron, the second most abundant trace element in humans. As an essential element for living organisms, Zn2+ plays a catalytic and structural role in many enzymes and regulatory proteins (Vallee, 1988). Since the surprising discovery that Zn2+ is present in large amounts within synaptic vesicles in many areas of the brain (Maske, 1955), numerous studies have investigated the possible roles of this metal on synaptic function. These studies have revealed that synaptic Zn2+ -- as an allosteric modulator -- inhibits GABAA, NMDA, and kainate receptors (Paoletti et al., 1997; Vogt et al., 2000; Ruiz et al., 2004; Mott et al., 2008; Nozaki et al., 2011; Veran et al., 2012), while potentiating glycine receptors (Hirzel et al., 2006). Moreover, synaptic Zn2+ -- as a trigger of signaling pathways -- is thought to be required for mossy fiber long-term potentiation (LTP) via pre– and postsynaptic mechanisms (Huang et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2011); however, these results are not consistent with other studies suggesting that Zn2+ signaling does not affect mossy fiber LTP (Vogt et al., 2000; Lavoie et al., 2011). Indeed, the establishment of specific pre- or postsynaptic pathways of Zn2+-mediated signaling and their physiological role on neuronal processing remain poorly understood.

The uniquely high concentrations of synaptic Zn2+ in the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) (Frederickson et al., 1988), an auditory brainstem nucleus with well-characterized circuitry and cellular mechanisms modulating synaptic transmission (Oertel and Young, 2004; Bender and Trussell, 2011), provides an attractive model for studying the role of synaptically-released Zn2+ in regulating synaptic transmission. DCN principal neurons receive Zn2+-rich excitatory parallel fiber inputs in their apical dendrites, yet the physiological consequences of synaptic Zn2+ release in this circuit are completely unknown. Here, we report an unexpected Zn2+-mediated signaling pathway wherein synaptic Zn2+ reduces presynaptic glutamate release by triggering endocannabinoid synthesis. Our results reveal a previously unknown Zn2+-mediated signaling pathway that establishes a role of synaptic Zn2+ release in regulating neurotransmission.

Material and Methods

Slice preparation

Experiments were conducted according to the methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Coronal brainstem slices were prepared from either sex ICR, mZnR wild type (mZnR WT) and knockout (mZnR KO), and ZnT3 wild type (ZnT3 WT) and knockout (ZnT3 KO) mice (P17–P25). The preparation of coronal slices containing DCN has been described in detail (Tzounopoulos et al., 2004).

Electrophysiology

In vitro recordings

Whole cell voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings were obtained from visually identified fusiform pyramidal neurons at a temperature of 31–33 °C. Fusiform cells were identified on the basis of morphological and electrophysiological criteria (Tzounopoulos et al., 2004). For DCN recordings the external solution contained the following (in mM): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 21 NaHCO3, 3.5 HEPES, and 10 glucose; saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

For EPSC recordings fusiform cells were voltage clamped at -70 mV using pipettes with a K+-based internal solution of (in mM): 113 K-gluconate, 1.5 MgCl2, 14 trisphosphocreatine, 9 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 4 Na-ATP, 0.3 tris-GTP, and 10 sucrose. All the internal solutions were adjusted to pH 7.3, ~ 285 mOsmol. Voltage-clamp experiments were not included if the series and/or input resistance changed >20% during the recording. EPSCs in fusiform cells were evoked by stimulating parallel fiber tracts (0.2 Hz) in the presence of SR95531 (GABAA receptor antagonist, 20 μM) and strychnine (glycine receptor antagonist, 0.5 μM). Fiber tracts were stimulated with voltage pulses (10-30 V). To measure the time course of pharmacological manipulations, EPSC peak amplitude was measured and averaged every minute, then normalized to baseline. To ensure wash-out of bath applied Zn2+ we perfused the slices at a rate of 6 ml / min. Synaptic Zn2+ release was induced by electrical stimulation of the parallel fibers using a protocol consisting of 100 pulses at 100 Hz and 30 pulses at 30 Hz. For DSE experiments, baseline EPSCs were acquired at a stimulation frequency of 0.67 Hz, followed by a depolarization of 5 s to 10 mV delivered to the postsynaptic cell. EPSC amplitude was measured and averaged from ten sweeps in each cell and normalized to the average value before depolarization. DSE is reported as a percentage of average EPSCs 1–3 s after depolarization versus before depolarization. Electrophysiological data were acquired and analyzed using pClamp (Molecular Devices), IGOR PRO (Wavemetrics), and GRAPHPAD PRISM (GraphPad Software). All means are reported ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using analysis of variance, and paired and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests. Statistical significance was based on P values <0.05. All means are reported ± SEM.

mEPSCs recordings

mEPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV in the presence of TTX (0.5 μM), SR95531 (20 μM) and strychnine (0.5 μM). The intracellular solution contained (in mM): 128 CsMeSO3, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 4 MgCl2, 4 ATP, 0.3 GTP, 10 phosphocreatine, 1 Cs-EGTA, 3 ascorbate, and 0.5 QX-314 (a blocker of voltage-activated Na+ channels). Ten-second blocks of mEPSCs were acquired at a sample rate of 50 kHz and low pass filtered at 10 kHz. Negative-voltage pulses (5 mV, 50 ms) were delivered every 10 sec to monitor input and access resistance; mEPSC experiments were not included if the series and/or input resistance changed >20% during the recording. mEPSCs were detected and analyzed using Mini-analysis software (Synaptosoft) with amplitude and area threshold set at 3 RMS (root mean square) noise level. All events were verified by visual inspection. Amplitude values were obtained by subtracting the average baseline from the amplitude at the local maximum during the event. Rise times were measured as time difference between 10 and 90% of the peak amplitude. Decay time was calculated as a time that took the event to decay to 37% of the peak amplitude.

Fluorescence Imaging

For Ca2+ imaging, slices were loaded with Fura-2 AM (25 μM, TefLabs) for 20 min. at room temperature, in the presence of 0.02% pluronic acid, and then washed in ACSF for at least 20 min (Besser et al., 2009). For extracellular Zn2+ imaging, Newport Green (2 μM) was added to the slice. Slices were then loaded in a microscope chamber and perfused with PO4-free ACSF to avoid Zn2+ precipitation (Chorin et al., 2011). Fluorescent imaging measurements were acquired every 3 s (Imaging Workbench 4, INDEC BioSystems; and polychrome monochromator, TILL Photonics) using a 10X objective (Olympus BX51) with 4 × 4 binning of the image (SensiCam, PCO). Regions of interest (ROI) were chosen throughout the DCN molecular layer that was not covered by the stimulating electrode, and traces from 4 ROIs were averaged for each slice. Cell bodies are surrounded by our selected ROIs, thus, the observed Fura-2 fluorescence changes mostly represent the result of Ca2+ rises in neuronal cell bodies. Fura-2 fluorescence signals are represented as a ratio of the signal obtained using excitation of 340 nm/380 nm wavelengths and a 510 nm emission bandpass filter (Chroma Technology). Newport Green fluorescent signals were normalized to the initial fluorescent level (F0) and the signal is represented as F/F0. Bar graphs represent the averaged difference in the fluorescent signal averaged over n slices as indicated. The stimulating electrode was placed on the molecular layer of the DCN and a train of 100 pulses at 100 Hz was applied (Master-8 stimulator unit, A.M.P.I.). When required, the initial baseline was used to calculate a linear regression curve that was subtracted from the trace.

2-AG quantification

A modified isotopic dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) method (Zhang et al., 2010) was used to determine 2-AG in dorsal cochlear nucleus slices. DCN slices were incubated at 37° C for ~30 min to allow the tissue to recover after the cutting procedure (similarly to electrophysiological experiments). 2-AG concentrations were measured in control samples and samples exposed to Zn2+ (100 μM, 5 min) in the presence or absence of U73122 (5μM). In experiments in which U73122 was used, slices were pretreated with this drug or vehicle for 30 min. After this pretreatment, both control and treated slices were transferred to a chamber with either normal solution or Zn2+ containing solution for 5 min (U73122 was also present during the 5 min treatment). Samples were then immediately flash-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. The tissues were later thawed and homogenized in 20 μl of H20 with 0.02 % trifluoroacetic acid and 2 μl aliquots were used for protein concentration determinations using the Bradford method. Then, 180 μl cold acetonitrile was added to the samples previously spiked with 9 pmoles 2-AG-d8 internal standard and followed by homogenization. The samples were centrifuged at 14000g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant transferred into vials. Brain homogenates at a 5 mg tissue/ml were used to perform quantification quality controls by spiking samples with internal standard and 300 pmol of 1-AG and 2-AG per mg of tissue. Samples were thawed and homogenized in the presence of deuterated 2-AG internal standard, thus controlling for any loss during sample work-up. The internal standard corrects for losses due to degradation, extraction efficiency, binding to silica present in the glass tubes, gas phase equilibrium and ionization efficiencies. The concentration of 2-AG was normalized to amounts of DCN protein to avoid the errors introduced by handling small amounts of tissue per DCN slice (typically below 1 mg).

Standard curve preparation

A calibration curve was prepared by serial stock dilutions of 2-AG and 1-AG. Three independent standard curves were prepared and the LOD (3 × signal to noise ratio (S/N)) and LOQ concentrations calculated (LOQ was defined as the lowest concentration displaying a RSD % lower than 15).

Liquid Chromatography

The chromatography was performed on a Shimadzu SIL-20A HPLC equipped with a degasser, autosampler and column oven (set at 37°C) on a 2.0 mm ID, 150 mm long, 3μm C-18 Luna column (Phenomenex). The solvent system used consisted of 0.1 % acetic acid in H2O and 0.1 % acetic acid in acetonitrile (ACN).

Mass spectrometry

The flow after the column was split and 1/3 was sent to a triple quadrupole for quantification purposes and 2/3 were diverted into a LTQ Velos Orbitrap for high mass spectrometer resolution ion and product ion determinations. The quantification of 1-AG and 2-AG was performed in positive ion mode using a 4000 QTrap triple quadrupole (Applied Biosystems). The following transitions were optimized and used for quantification of 1-AG and 2-AG (m/z 379 → 287) and 2-AG-d8 (m/z 387 → 295) using a collision energy of 15, a declustering potential of 50V, an entrance potential 8V and a collision cell exit potential of 15V. High resolution spectra and accurate mass determinations (at a resolving power of 10000) were obtained in samples and standards for 2-AG and 1-AG and its product ions.

Experiments with KO mice

Imaging and biochemical experiments were blinded (Fig. 4, 8). Electrophysiological experiments were partially blinded: initial experiments were not blinded (approximately half n), but all subsequent experiments were blinded (Fig. 11). As we did not observe any differences in the two data sets, we have included all these experiments.

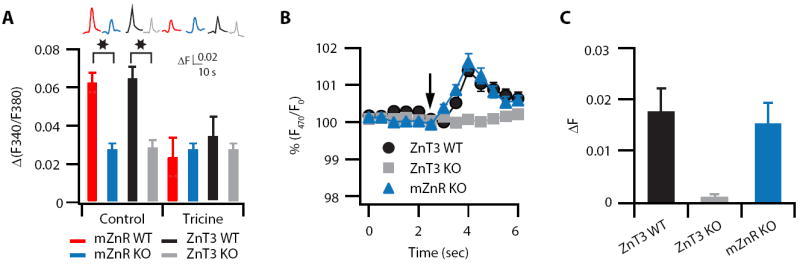

Figure 4. mZnR, a Zn2+ sensing Gq protein-coupled receptor, mediates Zn2+-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ in DCN neurons.

(A) Intracellular Ca2+ rise was monitored following a 100 Hz, 1s stimulation of the molecular layer of the DCN in the presence or absence of tricine (10 mM, top traces). Slices from WT and KO mice were loaded with Fura-2. The conditions for the different traces are indicated at the bottom of the bar graph. Bar graph showing averaged changes of Ca2+ rises. The residual Ca2+ response in the slices from mZnR KO and ZnT3 KO mice is not further attenuated by tricine and is similar to the response observed in the presence of tricine in slices from WT mice (ΔF/F: mZnR WT Control: 0.062 ± 0.005, n = 8; mZnR KO Control: 0.027 ± 0.003, n = 9, p<0.01; mZnR WT in tricine: 0.023 ± 0.01, n = 9, p<0.01 when compared to mZnR WT control; mZnR KO in tricine: 0.027 ± 0.003, n = 7, p = 0.48 when compared to mZnR WT in tricine; ZnT3 WT control: 0.064 ± 0.006, n=4; ZnT3 KO control: 0.028 ± 0.004, n = 8, p<0.01 when compared to ZnT3 WT control; ZnT3 WT in tricine; 0.034 ± 0.01, n=8, p<0.01 when compared to WT control; ZnT3 KO in tricine: 0.026 ± 0.004, n = 8, p= 0.52 when compared to ZnT3 KO control) (B) Representative response illustrating extracellular Zn2+-dependent changes in 2μM Newport Green (a non-permeable, extracellular Zn2+ sensor) fluorescence in the DCN fusiform cell layer after 1s, 100 Hz stimulation of the parallel fibers in a slice from WT, ZnT3 KO, and mZnR KO mice. (C) Average responses showing that Newport Green fluorescence in response to 1s, 100 Hz stimulation of the parallel fibers was abolished in ZnT3 KO mice, but was normal in mZnR KO mice (ΔF: ZnT3 WT: 0.018 ± 0.004, n = 7 slices; ZnT3 KO: 0.001 ± 0.0004, n = 11 slices, p<0.01 compared to ZnT3 WT; mZnR KO: 0.015 ± 0.004, n = 8 slices). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

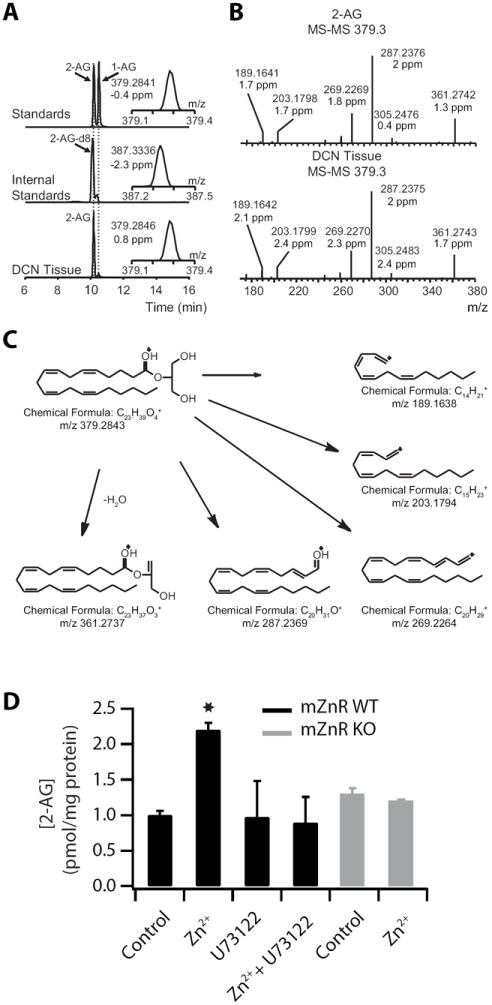

Figure 8. HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis reveals that Zn2+ induces a mZnR-dependent increase of 2-AG synthesis in the DCN.

(A) The two different AG isomers (2-AG and 1-AG) were chromatographically resolved and base peak separations were achieved. 2-AG and 2-AG-d8 were detected following the 379.3 to 287.2 m/z and 387.3 to 295.2 transitions respectively using a triple quadrupole. In parallel accurate mass determination using a Velos Orbitrap resulted in mass confirmations at the 2 ppm level for standards and for tissue obtained 2-AG (inserts). (B) 2-AG identity was confirmed by coelution with internal standard (a) and by high resolution MS and MS/MS data obtained on the 2-AG peak, where a similar fragmentation pattern was observed between the 2-AG standard and the DCN tissue samples. (C) Molecular structures of product ions obtained upon ion trap collision-induced dissociations of 2-AG shown in (B). (D) Zn2+ application increased 2-AG levels in a PLC and mZnR-dependent manner. HPLC-mass spectrometry measurements of 2-AG levels in DCN slices from WT and mZnR KO littermates in the presence of Zn2+ and/or U73122 (5 μM, PLC inhibitor applied for 30 min prior to Zn2+ application; mZnR WT Control: 1 ± 0.06 pmol / μg protein, n = 8; mZnR WT in Zn2+: 2.2 ± 0.1 pmol / μg protein, n = 8, p<0.01; mZnR WT in U73122: 0.97 ± 0.51 pmol / μg protein, n = 6 when compared to mZnR WT control; p = 0.6; mZnR WT in U73122 and Zn2+: 0.89 ± 0.37 pmol / μg protein, n = 7; p = 0.42 when compared to mZnR WT control; mZnR KO: 1.3 ± 0.08 pmol / μg protein in control, n = 6; mZnR KO in Zn2+: 1.2 ± 0.02 pmol / μg protein, n = 4, p = 0.5 when compared to mZnR KO control). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

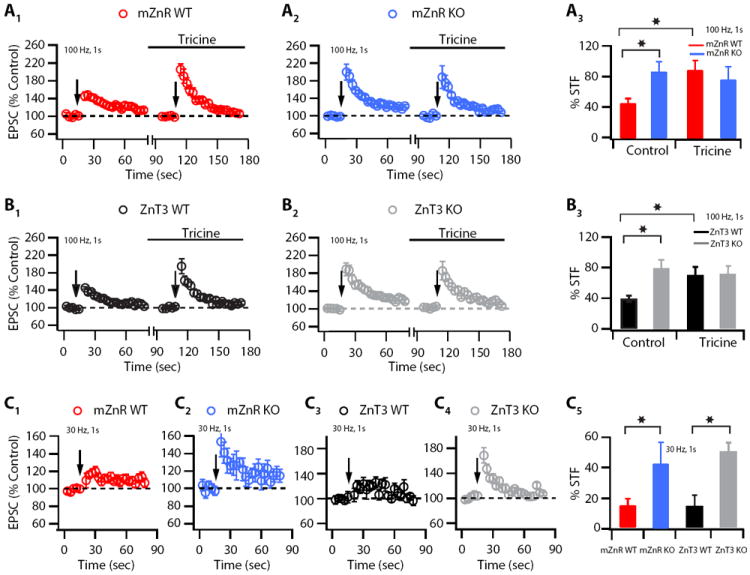

Figure 11. Synaptically released Zn2+ -induced modulation of short-term facilitation is absent in mZnR KO and in ZnT3 KO mice.

In (A1-A3) baseline short-term facilitation (STF), elicited by 100 Hz, 1s stimulation is increased in mZnR KO mice; tricine-mediated enhancement of STF is absent in mZnR KO littermates: (A1) Summary graph showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine in mZnR WT mice (100 Hz, 1s stimulation was applied before and after tricine for the same and for each cell; 10 mM tricine was bath-applied for at least 10 min prior to 100 Hz, 1 s stimulation; STF: mZnR WT: 45.41 ± 6.65 %, n = 10; mZnR KO: 87.28 ± 13.54 %, n = 10, p<0.01). (A2) Summary graph showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine as in (A1), but now in mZnR KO mice (STF: mZnR KO control: 87.28 ± 13.54 %, n = 10; mZnR KO in tricine: 76.83 ± 17.10 %, n=10, p = 0.30). (A3) Average values of STF from A1 and A2. % STF magnitude is the average of first three points after the train. In (B1-B3) baseline STF elicited by 100 Hz, 1s stimulation is increased in ZnT3KO mice; tricine-mediated enhancement of STF is absent in ZnT3 KO littermates. (B1) Summary graph showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine in ZnT3 WT mice (conditions are the same as in A1; STF: ZnT3 WT: 39.28 ± 3.97 %, n = 9; ZnT3 KO: 87.36 ± 10.92 %, n = 9, p<0.01). (B2) Summary graph showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine in ZnT3 KO mice (conditions are the same as in A1; STF: ZnT3 KO control: 87.36 ± 10.92 %, n = 9; ZnT3 KO in tricine: 71.6 ± 12.29 %, n = 9, p = 0.42)). (B3) Average values of STF from B1 and B2. % STF magnitude is the average of first three points after the train. In (C1-C5) baseline STF elicited by 30 Hz, 1 s stimulation is revealed in mZnR KO and in ZnT3 KO mice. (C1-C2) Summary graphs showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 30 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in mZnR WT and in mZnR KO littermates (STF: mZnR WT: 14.35 ± 4.41 %, n = 6; mZnR KO: 42.7 ± 14.10 %, n = 6 p<0.01 when compared to mZnR WT). (C3-C4) Summary graphs showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 30 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in ZnT3 WT and in ZnT3 KO littermates (STF: ZnT3 WT; 14.25 ± 6.91%, n = 6; ZnT3 KO; 49.34 ± 6.01%, n = 6, p<0.01 when compared to ZnT3 WT). (C5) Average values of STF from C1-C4. % STF magnitude is the average of first three points after the train. Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Drugs and KO mice

SR95531, NBQX disodium salt, QX-314, AM251, TTX, WIN55, 212-2 mesylate (WIN), were purchased from Ascent Scientific. ZnCl2, strychnine, BAPTA, GDP-β-S, tricine, and tetrahydrolipstatin (THL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The 2-AG, 1-AG and 2H8 2-AG standards were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). U73122 was purchased from Tocris Cookson. Fura-2AM and Newport Green were purchased from TefLabs and Invitrogen, respectively. GPR39/mZnR KO mice were kindly provided by D. Moechars from Janssen, Pharmaceutical companies of Johnson & Johnson. ZnT3 KO mice were purchased from Jackson.

Results

Zn2+ Decreases Probability of Release via Activation of Endocannabinoid Signaling

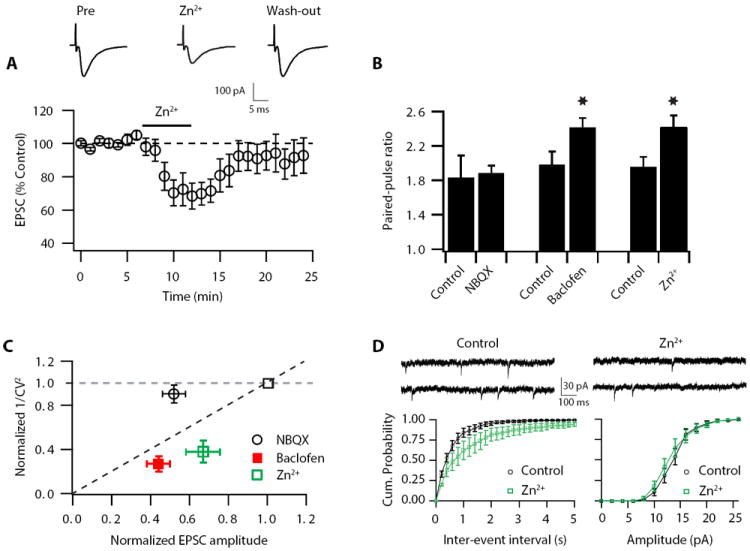

To investigate the effects of Zn2+ on parallel fiber excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) strength, we obtained whole-cell recordings from DCN principal neurons (fusiform cells). Bath application of Zn2+ (100 μM, 5 min) significantly decreased EPSC amplitude (Fig.1A). The inhibitory effect of Zn2+ on EPSC strength was reversed upon Zn2+ removal, suggesting that extracellular Zn2+ mediates a short-lasting decrease in synaptic strength (Fig.1A). The observed Zn2+-induced decrease in synaptic strength is due to pre- and or postsynaptic mechanisms. To investigate whether the effects of Zn2+ on synaptic strength are mediated by presynaptic mechanisms, we used two assays that are sensitive to changes in presynaptic neurotransmitter release (Pr): paired-pulse ratio (PPR) and coefficient of variation (CV) analysis (Faber and Korn, 1991; Tsien and Malinow, 1991). Paired-pulse facilitation, an increased second response to two stimuli applied in rapid succession, is thought to reflect an increase in Pr. The coefficient of variation (CV) is the standard deviation of the EPSC amplitudes normalized to the mean amplitude and varies oppositely with quantal content; the inverse square, CV-2, is directly proportional to quantal content (quantal content = n p, where n = number of release sites and p = Pr). Application of Zn2+ increased PPR and decreased 1/CV2 both of which indicate a decrease in Pr (Fig. 1 B, C). Baclofen (2-5 μM), which is known to inhibit synaptic strength via a presynaptic mechanism (Dutar and Nicoll, 1988), caused a similar increase in PPR and a similar reduction in 1/CV2, indicating that PPR and CV assays are highly sensitive to changes in Pr (Fig. 1B, C). Conversely, 0.5 μM NBQX (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione), which reduces synaptic strength by partially blocking postsynaptic glutamate receptors, left PPR and 1/CV2 unaffected, thus confirming that PPR and CV assays are not sensitive to changes in synaptic strength that are mediated by postsynaptic manipulations (Fig.1B, C). Consistent with these results, application of Zn2+ decreased miniature EPSC (mEPSC) frequency without affecting mEPSC amplitude (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these findings show that the Zn2+-induced EPSC depression is mediated by a decrease in Pr.

Figure 1. Zn2+ reduces synaptic strength by lowering probability of release (Pr).

(A) Time course of EPSC peak amplitude reversible depression by 100 μM, 5 min Zn2+ application (During Zn2+ application: 67.9 ± 9.0 % of baseline, n=7, p<0.01; after Zn2+ washout: 94.5 ± 9.5 % of baseline, n=7, p=0.7) Top, representative averaged traces of EPSCs before (pre), during (Zn2+) and after removal of Zn2+ (washout). (B) Paired-pulse ratio (20 ms interstimulus interval) is increased after Zn2+ application (PPR: baseline: 1.96 ± 0.11; after Zn2+: 2.42 ± 0.13; n = 7, p < 0.01). (C) Zn2+-induced EPSC depression is associated with a decrease in Pr. 1/CV2 is decreased after Zn2+ (1/CV2 in Zn2+: 0.38 ± 0.1% of baseline, n = 7, p < 0.01). Effect of baclofen on PPR and 1/CV2 (PPR: baseline: 2.00 ± 0.15; after baclofen: 2.42 ± 0.10; n = 6, p < 0.01; 1/CV2 in baclofen: 0.27 ± 0.07% of baseline, n = 6, p < 0.01). Effect of NBQX on PPR and 1/CV2 (PPR: baseline: 1.84 ± 0.25; after NBQX: 1.89 ± 0.08; n = 6, p = 0.47; 1/CV2 in NBQX: 0.90 ± 0.08 % of baseline, n = 8, p=0.55). (D) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC frequencies shows that Zn2+ application decreased frequencies (left panel). Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC amplitudes shows Zn2+ application did not affect amplitudes (right panel) Top, sample traces of mEPSCs before and after Zn2+ application (mean mEPSC frequency: baseline: 1.89 ± 0.3 Hz; after Zn2+: 1.22 ± 0.5 Hz; n = 4, p <0.05 paired t-test; mean mEPSC amplitude: baseline: 13.79 ± 0.81 pA; after Zn2+: 13.35 ± 0.94 pA; n = 4, p >0.12 paired t-test) Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Given the role of endocannabinoid retrograde signaling in determining the Pr of DCN parallel fiber synapses (Tzounopoulos et al., 2007; Tzounopoulos and Kraus, 2009; Sedlacek et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011; Zhao and Tzounopoulos, 2011), we tested whether endocannabinoids are involved in Zn2+-mediated modulation of Pr. We found that the specific cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) antagonist AM-251 (1μM) prevented Zn2+-mediated EPSC depression and the concomitant changes in PPR and 1/CV2 (Fig. 2A-C). Bath application of AM-251 (1 μM) did not affect baseline synaptic transmission, indicating lack of tonic activation of CB1Rs and lack of tonic endocannabinoid signaling in modulating baseline Pr (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that Zn2+- dependent endocannabinoid signaling mediates a Pr reduction, thus revealing an unexpected link between Zn2+ and endocannabinoid signaling.

Figure 2. Zn2+-induced decrease in Pr is mediated by endocannabinoid signaling.

(A) Zn2+-induced EPSC depression is blocked by 1 μM AM-251 (EPSC amplitude: in control: 66.4 ± 4.8 % of baseline, n=8, p<0.01; in AM-251: 91.4 ± 7 % of baseline, n= 6, p = 0.3). (B) Paired-pulse ratio (20 ms interstimulus interval) is increased after Zn2+ application in control conditions, but this increase is blocked in the presence of AM-251 (PPR in control: baseline: 1.88 ± 0.12; after Zn2+: 2.36 ± 0.11, n=8, p<0.01; PPR baseline in AM-251: 1.86 ± 0.2; after Zn2+: 1.91 ± 0.12; n = 6; p = 0.19. (C) 1/CV2 is decreased after Zn2+ application in control conditions, but this decrease is blocked in the presence of AM-251 (1/CV2 in Zn2+: 0.45 ± 0.12 %, n = 8, p<0.01; 1/CV2 in Zn2+ + AM-251: 0.97 ± 0.11 % of baseline, n = 6, p = 0.78). (D) Time course of baseline EPSC amplitude before and after application of AM-251 (EPSC amplitude after AM-251 application: 107.6 ± 10.2% of baseline, n =5, p=0.34). Summary data represent mean ± SEM

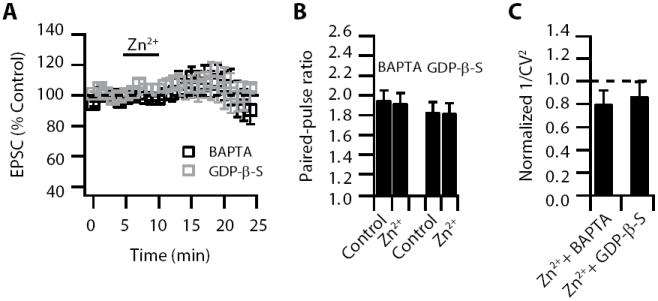

Endocannabinoid modulation of Pr has both postsynaptic (endocannabinoid synthesis and release) and presynaptic (activation of cannabinoid receptors, CB1Rs) components (Alger, 2012). Therefore, we investigated whether Zn2+-dependent modulation of Pr is mediated through direct presynaptic activation or allosteric modulation of CB1Rs, or through initiation of a postsynaptic signaling cascade leading to endocannabinoid synthesis and release. Intracellular application of the calcium chelator BAPTA (10 mM) in fusiform cells blocked Zn2+-induced depression of EPSCs and the concomitant changes in PPR and 1/CV2, indicating that an increase in postsynaptic Ca2+ is necessary for Zn2+-mediated modulation of Pr (Fig. 3A-C). While BAPTA also chelates intracellular Zn2+ (Hyrc et al., 2000), subsequent experiments using the extracellular zinc chelator tricine (e.g. see Figs. 4, 9 and 11) are consistent with a lack of dependence of our proposed mechanism on an intracellular Zn2+ increase. In addition, loading of fusiform cells with GDP-β-S (0.5 mM), a nonhydrolyzable analog of GDP, blocked the effects of Zn2+ on EPSC amplitude, PPR and 1/CV2, suggesting that postsynaptic activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) mediate Zn2+-induced activation of endocannabinoid signaling (Fig. 3A-C; see also figure legend for control experiments on the lack of effects on GDP-β-S on baseline synaptic transmission). Given that endocannabinoid synthesis from the postsynaptic neuron can be induced by elevations in intracellular Ca2+, by activation of GPCRs, or by concerted activation of GPCRs and elevations in intracellular Ca2+ (Wilson and Nicoll, 2001; Kim et al., 2002; Zhao and Tzounopoulos, 2011), our results indicate that Zn2+ likely promotes endocannabinoid production through a postsynaptic activation of GPCRs and a rise in intracellular Ca2+.

Figure 3. Zn2+-induced decrease in Pr requires rises in postsynaptic Ca2+ and postsynaptic activation of a G protein-coupled receptor pathway.

Zn2+-induced EPSC depression is blocked by: (A) 10 mM intracellular BAPTA and 0.5 mM intracellular GDP-β-S (BAPTA: EPSC amplitude: 99.9 ± 8.5% of baseline, n= 5, p = 0.3; GDP-β-S: EPSC amplitude: 105.87 ± 4.39 % of baseline, n = 7, p = 0.38) Our previous studies have shown that GDP-β-S does not affect parallel fiber EPSCs in fusiform cells; yet, application of GDP-β-S decreases the input resistance of fusiform cells (Zhao and Tzounopoulos, 2011). Thus, to avoid possible complications in the interpretation of our findings due to changes in input resistance and to allow diffusion of GDP-β-S in fusiform cells, we investigated the effect of GDP-β-S on Zn2+-mediated modulation of Pr after the GDP-β-S-mediated effect on input resistance reached a steady state: Zn2+ application took place ~ 30 min after break-in the cell (B) Paired-pulse ratio (20 ms interstimulus interval) was not increased after Zn2+ application in the presence of BAPTA and GDP-β-S (BAPTA: PPR: baseline: 1.95 ± 0.1; PPR after Zn2+: 1.92 ± 0.1; n = 5; p = 0.49; GDP-β-S: PPR baseline: 1.83 ± 0.1; PPR after Zn2+: 1.82 ± 0.1; n = 7; p = 0.8) (C) 1/CV2 was not decreased after Zn2+ application in the presence of BAPTA and GDP-β-S (BAPTA: 1/CV2: 0.8 ± 0.12 % of baseline, n = 5, p = 0.61; GDP-β-S: 1/CV2: 0.87 ± 0.13 % of baseline, n = 7, p = 0.78). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

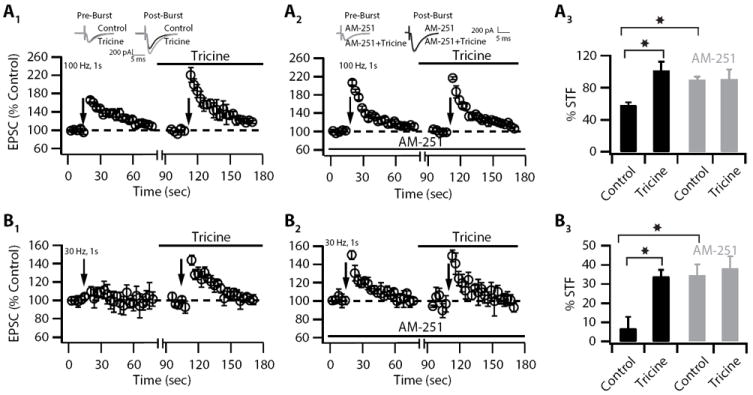

Figure 9. Synaptically released Zn2+ modulates short-term facilitation via endocannabinoid signaling.

(A1) Short-term facilitation (STF) is enhanced after Zn2+ chelation (STF: control: 58.24 ± 3.4%, n = 9; tricine: 101.5 ± 11.16 %, n = 9, p<0.01). Summary graph showing the time course of the change in EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine (100 Hz, 1s stimulation was applied before and after tricine for the same and for each cell; 10 mM tricine was bath-applied for at least 10 min prior to 100 Hz, 1 s stimulation). The high frequency stimulus was delivered under current-clamp to allow postsynaptic spiking. Top, representative traces of EPSCs before the train (pre-burst), and after the 100 Hz train (post-burst). (A2) AM-251 enhanced baseline STF and blocked the enhancement of PPT after Zn2+ chelation (STF: control in AM-251: 90.32 ± 3.40 %, n = 10, p<0.05 when compared to control from 9A1; tricine in AM-251: 90.55 ± 11.16 %, n = 10, p = 0.28 when compared to control in AM-251). Summary graph showing the time of the change in the EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation as in (A1), but now in the presence of AM-251 (preincubation of slices with 1 μM AM-251 for at 1 hr and bath application during the experiment). Top, representative traces of EPSCs before the train (pre-burst), and after the 100 Hz train (post-burst). (A3) Average values of STF from A1 and A2. % STF magnitude is the average of first three points after the train. (B1) Short-term facilitation is revealed after Zn2+ chelation; synaptic Zn2+ modulates the threshold for short-term facilitation (STF: control: 6.66 ± 6.10 %, n = 6, p=0.25; tricine: 33.95 ± 3.31%, n = 6, p<0.01). Summary graph showing the time course of the change in the EPSC amplitude after 30 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation, in control and after endogenous Zn2+ chelation with tricine (30 Hz, 1s stimulation was applied before and after tricine for the same and for each cell; 10 mM tricine was bath-applied for at least 10 min prior to 30 Hz, 1 s stimulation). The high frequency stimulus was delivered under current-clamp to allow postsynaptic spiking. (B2) AM-251 enhanced baseline STF and blocked the enhancement of PPT after Zn2+ chelation. Summary graph showing the time of the change in the EPSC amplitude after 100 Hz, 1s parallel fiber stimulation as in (B1), but now in the presence of AM-251 (preincubation of slices with 1 μM AM-251 for at 1 hr and bath application during the experiment; STF: control in AM-251: 34.27 ± 5.97 %, n = 6, p<0.01 when compared to control from 6B1; tricine in AM-251: 38.16 ± 6.23%, n = 6, p = 0.38 when compared to control in AM-251). (B3) Average values of STF from B1 and B2. % STF magnitude is the average of first three points after the train. Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Zn2+-Induced Decrease in Pr Is Mediated by a mZnR-dependent Increase of 2-AG Synthesis

Since endocannabinoid production is tightly linked to Gq-coupled receptors in the DCN (Zhao and Tzounopoulos, 2011), and because the previously orphan Gq-coupled receptor 39 (GPR39) has emerged as a putative metabotropic Zn2+-sensing receptor (mZnR) (Besser et al., 2009), we evaluated whether mZnR activation is involved in the Zn2+-triggered promotion of endocannabinoid production in the DCN. As activation of mZnRs is thought to lead to Zn2+-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ in the hippocampus and in cortical neurons (Besser et al., 2009; Saadi et al., 2012; but see Evstratova and Toth, 2011), we determined whether synaptically released Zn2+ leads to an mZnR-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ in the DCN. We measured intracellular Ca2+ responses in the fusiform cell layer of DCN slices from wild type (WT) and from genetically modified mice lacking GPR39 (Moechars et al., 2006) (mZnR KO mice). While parallel fiber stimulation (100 Hz, 1s) caused robust intracellular Ca2+ responses in slices from mZnR WT mice, measurements from littermate mZnR KO mice displayed significantly reduced Ca2+ responses (Fig. 4A). To determine whether reduced Ca2+ responses in mZnR KO mice are due to the lack of Zn2+-triggered, mZnR mediated signaling, we measured the sensitivity of the Ca2+ responses to tricine: an extracellular Zn2+ chelator (Paoletti et al., 2009). Application of 10 mM tricine reduced Ca2+ responses in WT mice and left Ca2+ responses unaffected in mZnR KO mice; tricine also reduced Ca2+ responses in WT mice to levels similar to those observed in mZnR KO mice (Fig. 4A). Because tricine only reduces Ca2+ responses in WT mice, but not in KO mice, we conclude that the observed differences in Ca2+ responses are due to Zn2+-mediated, mZnR-dependent signaling.

To further support that vesicular Zn2+ triggers Zn2+-mediated signaling via mZnR, we used a mouse genetic model lacking the transporter that loads Zn2+ into synaptic vesicles (ZnT3 KO) mice (Cole et al., 1999). ZnT3 KO mice lack vesicular Zn2+ staining and vesicular Zn2+ release (Cole et al., 1999; Qian and Noebels, 2005; Chorin et al., 2011). As expected, while ZnT3 WT mice displayed DCN vesicular Zn2+ release after parallel fiber stimulation, DCN vesicular Zn2+ release was undetectable in ZnT3 KO mice (Fig. 4B-C). In response to parallel fiber stimulation, ZnT3 KO mice displayed reduced Ca2+ responses when compared to WT mice; in addition, tricine did not affect Ca2+ responses in ZnT3 KO mice (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that a significant proportion of the Ca2+ response following stimulation of the parallel fibers requires both vesicular Zn2+ and the mZnR. While Fura-2 can also detect changes in intracellular Zn2+, previous studies have established that activation of mZnRs by extracellular Zn2+ leads to a PLC-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ that is not associated with Zn2+ influx (Besser et al., 2009; Chorin et al., 2011; Saadi et al., 2012). Finally, mZnR KO mice displayed normal DCN vesicular Zn2+ release (Fig. 4B-C). Together these findings suggest that mZnRs are functionally expressed in the DCN neurons and participate in Zn2+-triggered increases in intracellular Ca2+ responses.

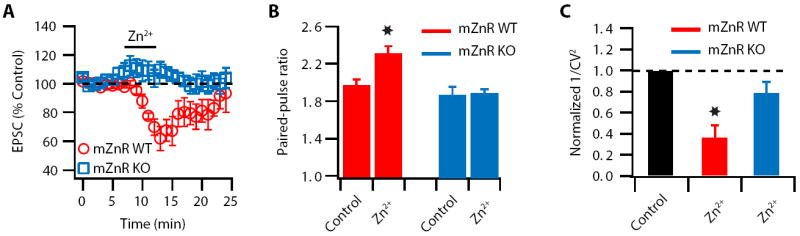

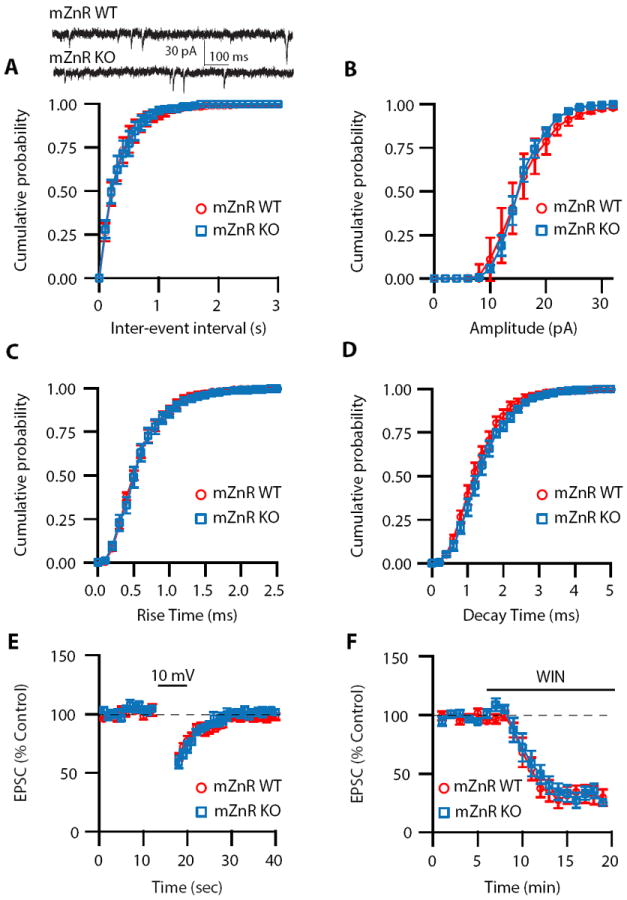

Given the dependence of the Zn2+-induced reduction of Pr on postsynaptic Ca2+ increases and GPCRs activation (Fig. 3A), as well as the mZnR-mediated increase in Ca2+ responses in DCN neurons (Fig. 4A), we tested whether mZnRs are necessary for the Zn2+-induced reduction of synaptic strength. We found that Zn2+-mediated modulation of EPSC amplitude, PPR and 1/CV2 were absent in mZnR KO mice (Fig. 5A-C). In contrast, littermate WT mice displayed reversible Zn2+-induced reductions on EPSC amplitude and Pr (Fig. 5A-C). PPR levels were not different between WT mZnR and mZnR KO mice, suggesting that the absence of mZnR does not affect baseline Pr (Fig. 5B, p=0.22). Importantly, mEPSC analysis revealed that basal quantal properties -- mini EPSC frequency and amplitude -- were not different between mZnR WT and KO mice (Fig. 6A, B). Moreover, mEPSC rise and decay times were not different between WT and KO mice (Fig. 6 C, D). These results indicate that the lack of effect of Zn2+ on reducing synaptic strength and Pr in mZnR KO mice is not due to differences in basal synaptic properties between WT and KO mice. The lack of Zn2+-mediated changes in Pr in mZnR KO mice was not caused by non-functional endocannabinoid signaling in mZnR KO mice. This was determined by the fact that depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE; DSE is induced by postsynaptic depolarization leading to rises in post synaptic Ca2+ levels that, in turn, trigger endocannabinoid synthesis and Pr reduction) was not different between mZnR WT and KO mice (Fig. 6E). DSE in mZnR KOs was blocked by AM-251, confirming that it is mediated by CB1Rs (n=5, not shown). These results reveal that baseline Pr and depolarization-induced endocannabinoid signaling are intact in mZnR KO mice. Finally, application of 2μM WIN-55, 212-2 (WIN, a CB1R agonist) caused a quantitatively and kinetically similar decrease in EPSC amplitude in WT and KO mice (Fig. 6F), suggesting that CB1R function is not altered between mZnR WT and mZnR KO mice. Because Zn2+-induced modulation of Pr and the Zn2+-induced promotion of endocannabinoid signaling are absent in mZnR KO mice, we conclude that mZnRs are necessary for the Zn2+-induced reduction of Pr, this Pr reduction is likely occurring via the activation of postsynaptic endocannabinoid synthesis.

Figure 5. mZnR is necessary for Zn2+-induced decrease in Pr.

(A) Zn2+-induced reversible depression of EPSCs was observed in WT mice but not in mZnR KO littermates (EPSC amplitude: mZnR WT: 65.7 ± 8 % of baseline, n = 6, p<0.01; mZnR KO: 107.4 ± 5.6 % of baseline, n = 5, p = 0.27). (B) Paired-pulse ratio (20 ms interstimulus interval) is increased after Zn2+ application in mZnR WT mice but is unaffected in mZnR KO littermates (mZnR WT: PPR baseline: 1.97 ± 0.05; PPR after Zn2+: 2.32 ± 0.06; n = 6, p<0.01; mZnR KO: PPR baseline: 1.88 ± 0.07; PPR after Zn2+: 1.90 ± 0.03; n = 5, p = 0.75). (C) 1/CV2 is decreased after Zn2+ application in mZnR WT mice but is unaffected in mZnR KO littermates (mZnR WT: 1/CV2: 0.36 ± 0.11 % of baseline, n = 6, p<0.01; mZnR KO: 1/CV2: 0.79 ± 0.11 % of baseline, n = 5, p = 0.15). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Figure 6. Quantal properties and depolarization-induced endocannabinoid signaling are not altered in mZnR KO mice.

(A) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC frequencies shows that frequencies are not different between mZnR WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC frequency: mZnR WT: 3.03 ± 0.45 Hz, n=5; mZnR KO: 3.52 ± 0.59 Hz; n = 5, p =0.51). Top, sample traces of mEPSCs from mZnR WT and KO mice (B) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC amplitudes shows that amplitudes are identical in mZnR WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC amplitude: mZnR WT: 16.62 ± 2.09 pA, n=5; mZnR KO: 15.56 ± 0.65 pA; n = 5, p = 0.64). (C) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC rise times shows that rise times are not different between mZnR WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC rise time: mZnR WT: 0.63 ± 0.05 ms, n=5; mZnR KO: 0.66 ± 0.05 ms; n = 5, p =0.61). (D) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC decay times shows that decay times are not different between mZnR WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC decay time: mZnR WT: 1.3 ± 0.09 ms, n=5; mZnR KO: 1.43 ± 0.07 ms; n = 5, p = 0.28). (E) Time course of DSE, induced by 5 s depolarization to 10 mV in mZnR WT and mZnR KO mice (mZnR WT: DSE: 37 ± 3.1% of control, n=5; mZnR KO: DSE: 41 ± 5.3% of control, n=6, p=0.35). (F) Time course of 2 μM WIN on baseline synaptic transmission of mZnR WT and mZnR KO mice (mZnR WT: 31.8 ± 0.77% of baseline, n=5, mZnR KO: 30.84 ± 1.9%, n=5, p=0.32). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

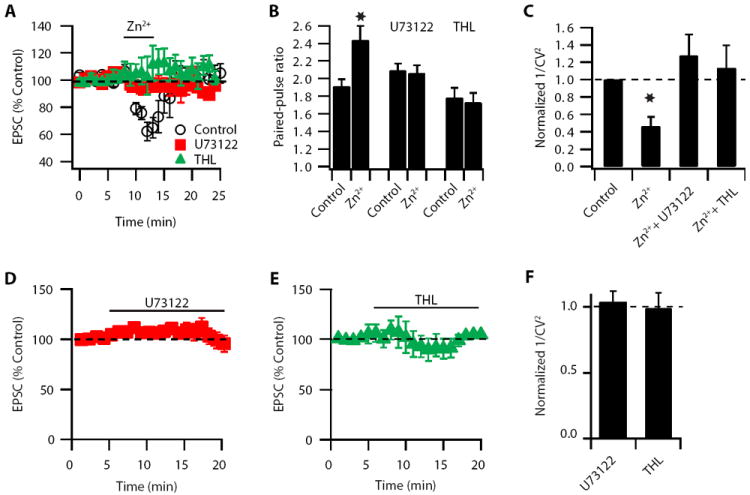

To determine the specific endocannabinoid that leads to mZnR mediated endocannabinoid signaling and subsequent Pr reduction, we used a combined electrophysiological and biochemical approach. 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), the endocannabinoid that mediates retrograde signaling in the DCN, is synthesized following phospholipase-C (PLC) activation and the cleavage of diacylglycerol by a diacylglycerol lipase (DGL) (Zhao et al., 2009). To determine whether Zn2+-induced changes in Pr are mediated through the 2-AG biosynthetic pathway, we first investigated the effect of pharmacological blockade of PLC and DGL on Zn2+-mediated Pr modulation. We observed that incubation of slices with either a PLC inhibitor (5 μM U73122), or a DGL inhibitor (10 μM tetrahydrolipstatin, THL) blocked Zn2+-induced depression of EPSC amplitude and the concomitant Zn2+-induced changes in PPR and 1/CV2 (Fig. 7A-C). Moreover, bath application of both these inhibitors did not affect baseline synaptic transmission, or CV of evoked EPSCs, indicating that their inhibitory effect on Zn2+-induced Pr reduction is not due to a non-specific change of baseline Pr that occludes or blocks further changes in Pr by Zn2+ (Fig. 7D-F). Taken together, these results suggest that application of Zn2+ leads to a PLC-dependent production of 2-AG.

Figure 7. Zn2+-induced decrease in Pr is mediated by a PLC- and DGL-dependent metabolic pathway.

(A) Zn2+-induced reversible depression of EPSCs was blocked by bath application of 5 μM U73122 or10 μM THL (EPSC amplitude: control: 67.60 ± 6.10 % of baseline, n = 5, p<0.01; U73122: 98.30 ± 3.66 % of baseline, n = 6, p = 0.33; THL: 105.40 ± 7.70 % of baseline, n = 6, p=0.42). (B) Paired-pulse ratio (20 ms interstimulus interval) is increased after Zn2+ application in control conditions, but this increase is blocked in the presence of either U73122 or THL (PPR: Control: baseline: 1.91 ± 0.08; after Zn2+: 2.44 ± 0.16; n = 5; p<0.01; U73122: baseline: 2.09 ± 0.08; after Zn2+: 2.06 ± 0.09; n = 6; p = 0.59; THL: baseline: 1.78 ± 0.11; after Zn2+: 1.72 ± 0.10; n = 6; p = 0.3). (C) 1/CV2 is decreased after Zn2+ application in control but this decrease is blocked in the presence of either U73122 or THL (1/CV2: after Zn2+: 0.46 ± 0.11% of baseline, n = 6, p<0.01; + U73122: 1.27 ± 0.24 % of baseline, n = 6, p = 0.41; + THL: 1.13 ± 0.26 % of baseline, n = 6, p = 0.56). (D) Bath application of U73122 does not affect baseline synaptic transmission (EPSC amplitude: 104.9 ± 2.9%, of baseline, n=5, p=0.25). (E) Bath application of THL does not affect baseline synaptic transmission (EPSC amplitide: 101.5 ± 2.1%, n=5, p=0.35). (F) Bath application of either U73122 or THL (10 μM) does not affect 1/CV2 (1/CV2: U73122: 1.03 ± 0.08% of baseline, n=5, p=0.52; THL: 0.99 ± 0.12% of baseline, n=5, p=0.59). Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Next, we employed isotopic dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) to quantify 2-AG levels and their dependence on Zn2+. The two different isomers of AG (2-AG and 1-AG) were chromatographically resolved and base peak separations were achieved (Fig. 8A). Consistent with previous reports (Zhang et al., 2010), the isotopically labeled 2-AG-d8 had a 0.12 min shorter retention time (Fig. 8A). The formation of endogenous 2-AG was confirmed by coelution with internal standard (Fig. 8A) and by high resolution MS and MS/MS data obtained on the 2-AG peak, where a similar fragmentation pattern was observed between the standard and the DCN tissue samples (Fig. 8B, C). In agreement with our hypothesis on the enhancing effect of Zn2+ on the 2-AG metabolic pathway (Fig. 7), HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis showed that DCN 2-AG levels increased significantly after Zn2+ (100 μM for 5 minutes) application (Fig. 8D). Moreover, Zn2+-mediated increases in 2-AG levels were abolished when slices were either pretreated with the PLC inhibitor (U73122, 5 μM for 30 min prior to Zn2+ application) or in mZnR KO mice (Fig. 8D). These results indicate that exogenous Zn2+ leads to increased 2-AG synthesis via a PLC-dependent pathway. Given that 2-AG synthesizing enzymes have been localized in the dendrites of DCN fusiform cells (Zhao et al., 2009), our results suggest that activation of mZnR leads to the activation of postsynaptic PLC and DGL leading to enhanced postsynaptic 2-AG production.

Endogenous Synaptic Zn2+ Levels Decrease Pr via mZnR and Endocannabinoid Signaling

Next, we investigated whether endogenous, synaptically released Zn2+ reduces Pr via promotion of endocannabinoid signaling. Brief bursts of presynaptic activity can promote the synthesis and release of endocannabinoids from postsynaptic cells, leading to presynaptic CB1 receptors activation that, in turn, suppress neurotransmitter release (Brown et al., 2003). This process leads to endocannabinoid-mediated short-term plasticity: short-term depression in this case. Therefore, to determine whether endogenous Zn2+ triggers endocannabinoid signaling, we investigated the role of synaptically-released Zn2+ in short-term plasticity. We measured parallel fiber-evoked EPSCs at low frequencies (0.3 Hz) before and after a high frequency stimulus train (100 Hz, 1sec). This stimulus train produced short-term facilitation in EPSC amplitude (termed in figures STF; Fig. 9A1). Bath application of the extracellular Zn2+ chelator tricine after the initial stimulus train -- in the same cell -- significantly increased the magnitude of short-term facilitation induced by an identical stimulus train (Fig. 9A1, A3). These results suggest that chelation of synaptically released Zn2+ during the high frequency train enhanced the magnitude of induced short-term facilitation. Brief trains of presynaptic activity -- apart from promoting synthesis and release of endocannabinoids -- trigger a build-up of calcium in presynaptic boutons resulting in forms of short-term plasticity (Zucker and Regehr, 2002), such as augmentation and post-tetanic potentiation (PTP). In many synapses, the combined effect of PTP and endocannabinoid signaling determines the size and the sign of short-term plasticity (Beierlein et al., 2007). Therefore, one possible interpretation of the effect of tricine in enhancing the amount of short-term facilitation is that the chelation of Zn2+ blocks Zn2+-mediated endocannabinoid signaling and short-term depression, thereby leading to enhanced short-term facilitation. This hypothesis predicts that blockade of endocannabinoid signaling should increase the amount of short-term facilitation and occlude the enhancing effect of tricine. Consistent with this hypothesis, application of AM-251 increased short-term facilitation and occluded the enhancement of short-term facilitation produced by Zn2+ chelation (Fig. 9A2, A3). These results suggest that endogenous, synaptically-released Zn2+ modulates short-term facilitation by enhancing endocannabinoid signaling.

If chelation of synaptic Zn2+ enhances short-term facilitation (Fig. 9A) by affecting the balance between opposing forms of modulation of Pr, we expect that synaptic Zn2+ would modulate the threshold for inducing short-term facilitation. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effect of zinc chelation on threshold conditions under which presynaptic trains of action potentials fail to induce short-term plasticity. We varied the frequency of presynaptic bursts and investigated the effect of tricine on the resulting short-term plasticity. We found that although a 30 Hz, 1 sec stimulation did not affect synaptic strength, application of tricine -- under identical conditions -- resulted in significant short-term facilitation (Fig. 9B1, B3). Moreover, application of AM-251 alone under these conditions also revealed short-term facilitation and, importantly, occluded the enhancing effect of tricine (Fig. 9B2, B3). Taken together, these results suggest that the release of endogenous Zn2+ during bursts of presynaptic activity promotes endocannabinoid signaling and shifts the balance of opposing short-term plasticity mechanisms towards reduction -- or decreased enhancement -- of synaptic strength.

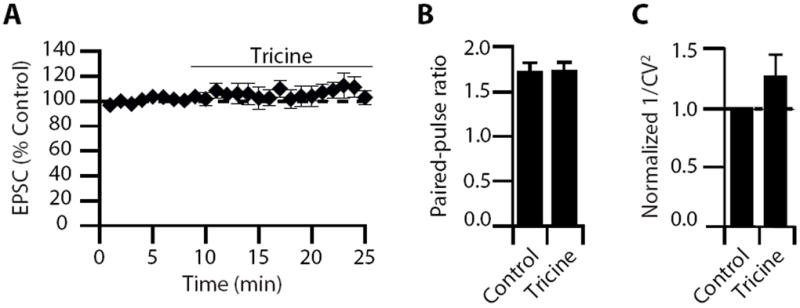

Because PTP depends on baseline Pr (Zucker and Regehr, 2002) potential effects of tricine on baseline Pr would affect the amount of observed short-term facilitation. However, tricine did not affect baseline EPSC strength, PPR or CV, thus suggesting that its effects on short-term plasticity are not due to changes of baseline Pr (Fig. 10A-C). Moreover, these observations indicate that any release of synaptic Zn2+ during baseline synaptic transmission is not capable of promoting endocannabinoid signaling; presynaptic trains of action potentials are needed for Zn2+-induced promotion of endocannabinoid signaling. Taken together, these findings (Figs 9-10) reveal a previously unknown role for synaptic Zn2+ in setting the threshold for short-term plasticity via enhancement of endocannabinoid signaling.

Figure 10. Tricine does not affect either baseline synaptic transmission or Pr.

(A) Time course of the effect of tricine on EPSC amplitude (EPSC amplitude: 106.4 ± 6.7% of control, n=6, p=0.57). (B) PPR (PPR control: 1.71 ± 0.11; tricine: 1.72 ± 0.10, n = 6, p =0.51) and (C) 1/CV2 (1/CV2 in tricine: 1.28 ± 0.18% of control, n = 6, p=0.3) did not change after 10 mM tricine application. Summary data represent mean ± SEM.

Given that exogenous Zn2+ triggers endocannabinoid synthesis is dependent on mZnRs (Figs. 2-8), we hypothesized that endogenous Zn2+-mediated reduction of short-term facilitation (Fig. 9) is also dependent on mZnRs. If mZnRs are necessary for the Zn2+-induced endocannabinoid synthesis, then we expect that short-term facilitation should be increased in mZnR KO mice; the enhancing effect of tricine on short-term facilitation should also be absent in mZnR KO mice. In agreement with our hypotheses, short-term facilitation in response to 100 Hz stimulation was enhanced in mZnR KO mice (Fig. 11 A1, A3). Moreover, chelation of synaptically-released Zn2+ by tricine did not increase the magnitude of short-term facilitation in mZnR KO mice, suggesting that the lack of the zinc receptor -- similarly to application of AM-251 in control mice in Fig. 9 -- occludes the effect of tricine (Fig. 11A2, A3). Since depolarization-induced endocannabinoid signaling is intact in mZnR KO and baseline Pr is not affected by the absence of mZnR (Fig. 6), these results suggest that the enhancing effect of synaptic Zn2+ on short-term plasticity is dependent on mZnR activation of endocannabinoid signaling.

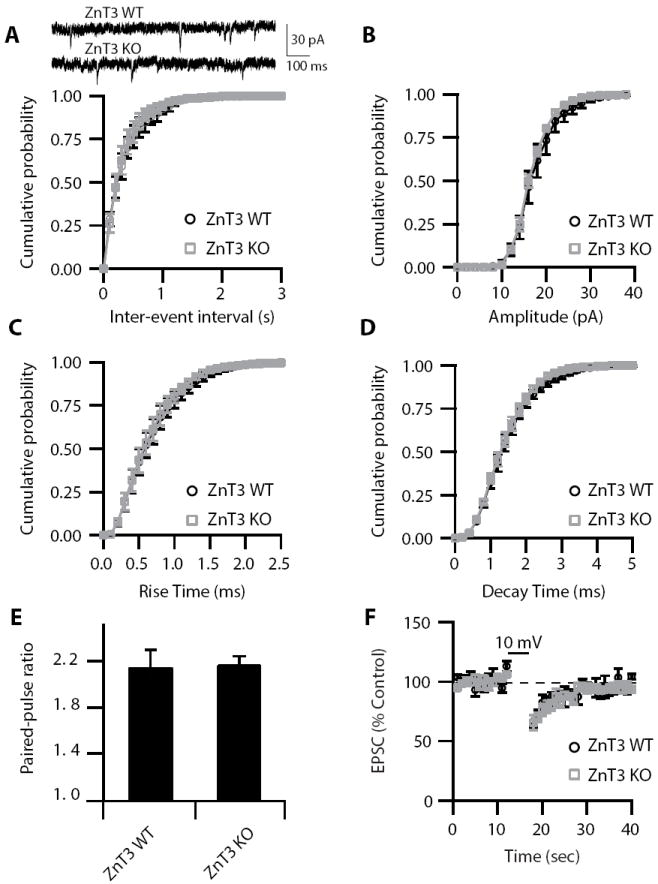

To determine the effect of elimination of synaptic Zn2+ release on endocannabinoid signaling and short-term plasticity, we also used ZnT3 KO mice, which do not display any DCN vesicular Zn2+ release (Fig. 4B,C). Given that Zn2+-chelation experiments with tricine suggest that the release of vesicular Zn2+ decreases short-term facilitation levels (Fig. 9), ZnT3 KO mice are expected to show more robust short-term facilitation than WT littermate mice. Moreover, we expected that the enhancing effect of tricine on short-term facilitation would be occluded in ZnT3 KO mice. Indeed, comparison of short-term facilitation levels between ZnT3 WT and ZnT3 KO littermates revealed increased levels of short-term facilitation (100 Hz stimulation) in ZnT3 KO mice (Fig. 11B1, B3). Additionally, the enhancing effect of tricine was occluded in ZnT3 KO mice (Fig. 11 B2, B3). Together these results suggest that endogenous, synaptically-released Zn2+ mediates the depressing effects in short-term plasticity observed in fusiform cells.

During milder presynaptic stimulation (30 Hz, 1sec) synaptic Zn2+ increased the threshold for short-term facilitation (Fig. 9B1-B3). Based on this finding, we hypothesized that the threshold for inducing short-term facilitation would be lower in mZnR KO and in ZnT3 KO mice. To test this hypothesis we investigated the amount of short-term facilitation after a 30 Hz 1sec presynaptic stimulus. In accordance with our hypothesis, while mZnR WT and ZnT3 WT mice revealed minimal levels of short-term facilitation, mZnR KO and ZnT3 KO mice revealed significantly enhanced levels of short-term facilitation (Fig. 11C1-C5). The observed effects in ZnT3KO mice are not due to changes in either, basal quantal properties, baseline Pr, or in deficient endocannabinoid signaling in ZnT3 KO mice, as WT and KO mice displayed similar mEPSC frequency, amplitude, rise time, decay time, similar levels of baseline PPR, and similar depolarization-induced endocannabinoid signaling (Fig 12 A-F). Taken together, our physiological, pharmacological, genetic and biochemical results show that release of endogenous, vesicular Zn2+ reduces neurotransmitter release via mZnR-dependent, Gq-coupled receptor activation of 2-AG synthesis. While a Gq-coupled receptor promotion of endocannabinoid synthesis has been well established during the last decade, our results reveal a surprising link between synaptically released Zn2+ and retrograde endocannabinoid signaling, thus providing a significant advance towards the elucidation of the role of Zn2+ in synaptic physiology.

Figure 12. Quantal properties, baseline Pr and depolarization-induced endocannabinoid signaling are not altered in ZnT3 KO mice.

(A) Top, sample traces of mEPSCs from ZnT3 WT and KO mice. Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC frequencies shows that frequencies are not different between ZnT3 WT and ZnT3 KO mice (mean mEPSC frequency: WT: 3.25 ± 0.60 Hz, n=5; KO: 3.57 ± 0.73 Hz; n = 5, p =0.74). (B) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC amplitudes shows that amplitudes are not different between ZnT3 WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC amplitude: WT: 17.50 ± 1.2 pA, n=5; KO: 16.7 ± 0.33 pA; n = 5, p = 0.54). (C) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC rise times showing that rise times are not different between ZnT3 WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC rise time: WT: 0.67 ± 0.06 ms, n=5; KO: 0.59 ± 0.03 ms; n = 5, p =0.3). (D) Cumulative probability plot of mEPSC decay times showing that decay times are not different between ZnT3 WT and KO mice (mean mEPSC decay time: WT: 1.44 ± 0.08 ms, n=5; KO: 1.42 ± 0.07 ms; n = 5, p = 0.84). (E) PPR is similar in ZnT3 WT and ZnT3 KO littermates (PPR: WT: 2.13 ± 0.15, n=7; KO: 2.16 ± 0.11, n = 7, p =0.85). (F) DSE is similar in ZnT3 WT and KO mice. Time course of DSE, induced by a 5s depolarization to 10 mV (DSE WT: 33.5 ± 4.9% of control, n=5; KO: DSE: 35 ± 3.2% of control, p=0.54). Summary data represent mean ± SEM

Discussion

We report that synaptic Zn2+ modulates probability of release of glutamatergic terminals via activation of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. We propose that Zn2+-mediated modulation of Pr via endocannabinoid signaling reveals a previously unrecognized synaptic signaling pathway that includes presynaptic ZnT3 and CB1Rs as well as postsynaptic mZnRs, PLC and DGL. This signaling pathway provides a fundamental substrate for both neuromodulatory and state-dependent regulation of neuronal properties, thus shaping synaptic strength in an activity-dependent manner.

The Role of Zn2+ and mZnR in Modulating Synaptic Transmission

Our studies provide the first evidence for inhibitory effects of Zn2+-mediated signaling on Pr. We demonstrate a synaptic Zn2+-mediated negative feedback loop that reduces Pr at DCN parallel fiber synapses through a signaling pathway linking Zn2+ release to endocannabinoid synthesis. Bath application of exogenous Zn2+ as well as release of endogenous Zn2+ caused a reversible reduction of Pr. This inhibitory effect of Zn2+ is opposite to the effect that has been observed in mossy fiber synapses (Li et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2008), where exogenous Zn2+ application leads to LTP of synaptic response via presynaptic increases in Pr (Huang et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2011). Given that mZnRs are likely present in mossy fiber synapses (Besser et al., 2009; Chorin et al., 2011), the lack of the inhibitory effect of Zn2+ on Pr is likely due to the absence of endocannabinoid signaling in mossy fiber synapses (Hofmann et al., 2008). Our results suggest that the synaptic effects of Zn2+ are synapse-specific and, similar to other neuromodulatory systems, Zn2+ -mediated effects depend on the molecular composition of specific synapses.

While previous studies have shown that Zn2+ is released in an activity and Ca2+-dependent manner (Qian and Noebels, 2005, 2006), there has a been a controversy whether synaptic Zn2+ is released or whether Zn2+ creates a layer in the extracellular space that maps onto the synaptic Zn2+ stained region (Zn2+ veneer theory; (Kay, 2003; Kay and Toth, 2008). Indeed, the amount of synaptic Zn2+ that reaches the postsynaptic membrane during synaptic stimulation remains unknown with estimates from ~0 or no Zn2+ release (Kay, 2003; Kay and Toth, 2008), to more than 100 μM (Vogt et al., 2000). Here, we focused on determining whether synaptically-released (endogenous) Zn2+ -- regardless of the actual concentration reached in synaptic cleft -- was sufficient to trigger endocannabinoid signaling. The results presented in Figs 9 and 11 show that endogenous Zn2+ reduces Pr via endocannabinoid signaling in the DCN. Thus, our pharmacological and genetic manipulations support a ZnT3/mZnR–dependent, endocannabinoid-mediated decrease of Pr as a result of release of endogenous levels of Zn2+ in response to brief stimulus trains.

While recent results have indicated that synaptically released Zn2+ induced by a single action potential blocks NMDAR responses (Pan et al., 2011), our results show that mZnR-dependent triggering of endocannabinoid signaling requires trains of presynaptic action potentials. The requirement for trains of presynaptic action potentials is consistent with the recent proposal that Zn2+-containing synaptic mossy fiber vesicles populate the reserve -- not the readily released -- pool (Lavoie et al., 2011). Although the detailed physiological conditions leading to mZnR-mediated signaling remain undetermined, our findings suggest that, in response to a brief 30 Hz train, endogenous Zn2+ levels set the threshold for eliciting short-term plasticity (Fig. 9 B1 and Fig. 11C). While in vivo recordings from DCN granule cells have not been obtained, sensory stimulation can produce bursts of spikes in cerebellar granule cells at very high firing frequencies (more than 200 Hz) (Chadderton et al., 2004). Given the strong parallels between DCN and cerebellar granule cells (Oertel and Young, 2004), the brief 30 Hz stimulation that we used is expected to be well within the physiological range of parallel fiber activity, thus suggesting that Zn2+-mediated endocannabinoid pathway can be engaged by physiologically relevant stimuli.

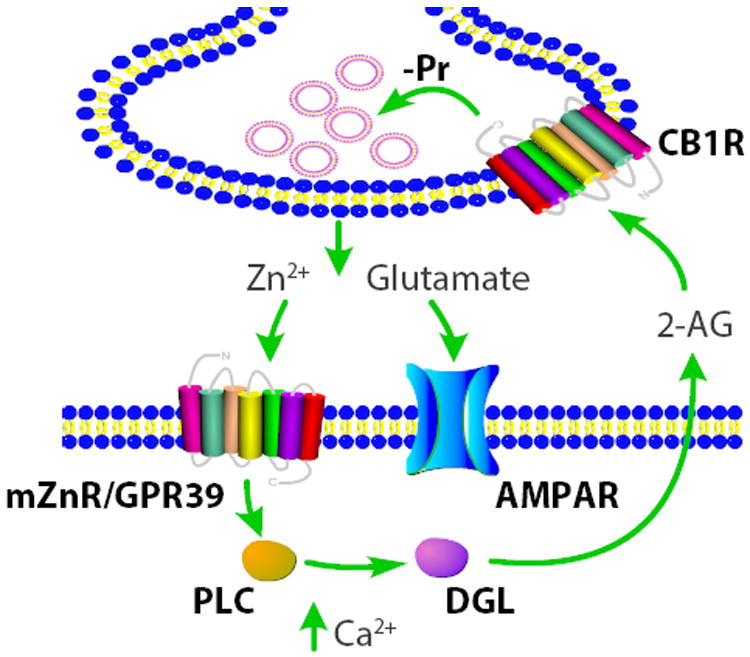

Our results demonstrate that GPR39 (mZnR) is necessary for Zn2+-mediated endocannabinoid synthesis; it is likely that synaptically released Zn2+ mediates its effects on endocannabinoid signaling and Pr via direct activation of GPR39 (mZnR, Figure 13). GPR39, a previously orphan G-protein coupled receptor was initially proposed to mediate obestatin signaling and to regulate food intake (Zhang et al., 2005). However, the absence of GPR39 in the hypothalamus (Jackson et al., 2006) and the identification of Zn2+, rather than obestatin, as its putative endogenous ligand (Yasuda et al., 2007) have raised questions regarding the physiological role of GPR39. Recent studies have suggested that synaptically released Zn2+ triggers metabotropic signaling via mZnR in the hippocampus (Besser et al., 2009), enhancing the activity of the potassium chloride co-transporter 2 in CA3 pyramidal neurons (Chorin et al., 2011). We show that during synaptic activation of excitatory terminals, similar to group 1 mGluRs (Maejima et al., 2001; Varma et al., 2001; Kushmerick et al., 2004), the mZnR is necessary for 2-AG synthesis and thus, contributes to the overall signaling profile of excitatory synaptic transmission that is tightly coupled to postsynaptic endocannabinoid synthesis. Because the 2-AG synthesizing enzymes -- DGLα and DGLβ — have been localized to the dendrites of DCN fusiform cells (Zhao et al., 2009), our electrophysiological, imaging and biochemical results are consistent with a postsynaptic localization of mZnRs.

Figure 13. Schematic representation illustrating the mechanism of Zn2+-induced decrease in Pr.

Synaptically released Zn2+, mZnR activation, rises in postsynaptic Ca2 and PLC stimulation are necessary for 2-AG synthesis. 2-AG is produced by cleavage of diacylglycerol (DAG) by DAG lipase (DGL). 2-AG diffuses to the presynaptic terminal where decreases Pr.

The Role of Zn2+ in Brain Function

The allosteric modulation of NMDA and glycine receptors by Zn2+ has suggested roles in learning, and motor control respectively (Hirzel et al., 2006; Adlard et al., 2010). Synaptically released Zn2+ has also been associated with Alzheimer’s disease and pain processing (Deshpande et al., 2009; Duce et al., 2010; Nozaki et al., 2011). Although initial studies did not uncover cognitive deficits in ZnT3KO mice (Cole et al., 2001), recent evidence reveals impaired fear memory (Martel et al., 2010), impaired spatial memory and impaired behavior dependent on hippocampus and perirhinal cortex (Martel et al., 2011), accelerated aging-related decline of spatial memory (Adlard et al., 2010), as well as impairments in spatial working memory and contextual discrimination in mice that lack vesicular Zn2+ (Sindreu et al., 2011). Our studies, by demonstrating a Zn2+-mediated negative feedback loop that reduces Pr at central auditory synapses -- through a specific pathway linking mZnR activation, endocannabinoid synthesis and Pr inhibition -- pave the way for novel in-vivo and behavioral experimental paradigms aimed at further defining the role of Zn2+ on brain function.

In sensory systems, the levels of synaptic Zn2+ in somatosensory cortex can be rapidly and dynamically regulated by sensory experience, although the physiological consequences of these changes have not been determined (Brown and Dyck, 2003; Nakashima and Dyck, 2009, 2010). Although it has been known for 25 years that DCN parallel fibers contain very large amounts of synaptic Zn2+ (Frederickson et al., 1988), the physiological role of this metal in modulating auditory circuits has not been previously evaluated. Based on our observations, we propose that synaptic Zn2+ -- by providing a negative feedback loop that reduces synaptic strength -- may decrease the responsiveness of the cochlear nucleus to acoustic stimuli: thus, synaptic Zn2+ release is expected to reduce the gain of input-output transformations between the auditory nerve and the cochlear nucleus. This is consistent with the proposed inhibitory role of Zn2+ in visual and auditory processing centers (Hirzel et al., 2006; Chappell et al., 2008), thus supporting the notion that Zn2+ is an inhibitory neuromodulator in sensory systems.

In conclusion, our results reveal the existence of a cellular pathway linking synaptically released Zn2+ and endocannabinoids: a previously unrecognized connection between two fundamental neuromodulatory systems, leading to activity-dependent inhibition of synaptic strength.

Acknowledgments

We thank Veronica Choi, Courtney Pedersen and Karen Hartnett for technical assistance. We thank Drs. Karl Kandler, Carlos Aizenman and Paul Rosenberg for critical reading of earlier versions of the manuscript. GPR39/mZnR KO mice were kindly provided by Dr. Moechars from Janssen, Pharmaceutical companies of Johnson & Johnson. This work was supported by NIH grants DC007905 (TT), NS043277 (EA), HL058115 (BAF), HL64937 (BAF), DK072506 (BAF), HL103455 (BAF), and AT006822 (FJS), by a Hemsley Trust grant (BSF2011126) from the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation (EA, MH), and by NIH training grant F32DC011664 (TP-R).

References

- Adlard PA, Parncutt JM, Finkelstein DI, Bush AI. Cognitive loss in zinc transporter-3 knock-out mice: a phenocopy for the synaptic and memory deficits of Alzheimer’s disease? J Neurosci. 2010;30:1631–1636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE. Endocannabinoids at the synapse a decade after the dies mirabilis (29 March 2001): what we still do not know. J Physiol. 2012;590:2203–2212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Fioravante D, Regehr WG. Differential expression of posttetanic potentiation and retrograde signaling mediate target-dependent short-term synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender KJ, Trussell LO. Synaptic plasticity in inhibitory neurons of the auditory brainstem. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:774–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser L, Chorin E, Sekler I, Silverman WF, Atkin S, Russell JT, Hershfinkel M. Synaptically released zinc triggers metabotropic signaling via a zinc-sensing receptor in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2890–2901. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5093-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CE, Dyck RH. Experience-dependent regulation of synaptic zinc is impaired in the cortex of aged mice. Neuroscience. 2003;119:795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton P, Margrie TW, Hausser M. Integration of quanta in cerebellar granule cells during sensory processing. Nature. 2004;428:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nature02442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell RL, Anastassov I, Lugo P, Ripps H. Zinc-mediated feedback at the synaptic terminals of vertebrate photoreceptors. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorin E, Vinograd O, Fleidervish I, Gilad D, Herrmann S, Sekler I, Aizenman E, Hershfinkel M. Upregulation of KCC2 Activity by Zinc-Mediated Neurotransmission via the mZnR/GPR39 Receptor. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12916–12926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2205-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TB, Martyanova A, Palmiter RD. Removing zinc from synaptic vesicles does not impair spatial learning, memory, or sensorimotor functions in the mouse. Brain Res. 2001;891:253–265. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TB, Wenzel HJ, Kafer KE, Schwartzkroin PA, Palmiter RD. Elimination of zinc from synaptic vesicles in the intact mouse brain by disruption of the ZnT3 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1716–1721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Kawai H, Metherate R, Glabe CG, Busciglio J. A role for synaptic zinc in activity-dependent Abeta oligomer formation and accumulation at excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4004–4015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5980-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duce JA, et al. Iron-export ferroxidase activity of beta-amyloid precursor protein is inhibited by zinc in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2010;142:857–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutar P, Nicoll RA. Pre- and postsynaptic GABAB receptors in the hippocampus have different pharmacological properties. Neuron. 1988;1:585–591. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evstratova A, Toth K. Synaptically evoked Ca2+ release from intracellular stores is not influenced by vesicular zinc in CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 2011;589:5677–5689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.216598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber DS, Korn H. Applicability of the coefficient of variation method for analyzing synaptic plasticity. Biophysical Journal. 1991;60:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82162-2. erratum appears in Biophys J 1992 Mar;61(3):following 831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ, Howell GA, Haigh MD, Danscher G. Zinc-containing fiber systems in the cochlear nuclei of the rat and mouse. Hear Res. 1988;36:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirzel K, Muller U, Latal AT, Hulsmann S, Grudzinska J, Seeliger MW, Betz H, Laube B. Hyperekplexia phenotype of glycine receptor alpha1 subunit mutant mice identifies Zn(2+) as an essential endogenous modulator of glycinergic neurotransmission. Neuron. 2006;52:679–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann ME, Nahir B, Frazier CJ. Excitatory afferents to CA3 pyramidal cells display differential sensitivity to CB1 dependent inhibition of synaptic transmission. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1140–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Pan E, Xiong ZQ, McNamara JO. Zinc-mediated transactivation of TrkB potentiates the hippocampal mossy fiber-CA3 pyramid synapse. Neuron. 2008;57:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyrc KL, Bownik JM, Goldberg MP. Ionic selectivity of low-affinity ratiometric calcium indicators: mag-Fura-2, Fura-2FF and BTC. Cell Calcium. 2000;27:75–86. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson VR, Nothacker HP, Civelli O. GPR39 receptor expression in the mouse brain. Neuroreport. 2006;17:813–816. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000215779.76602.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR. Evidence for chelatable zinc in the extracellular space of the hippocampus, but little evidence for synaptic release of Zn. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6847–6855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06847.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR, Toth K. Is zinc a neuromodulator? Sci Signal. 2008;1:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.119re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Isokawa M, Ledent C, Alger BE. Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors enhances the release of endogenous cannabinoids in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10182–10191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10182.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2001;29:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick C, Price GD, Taschenberger H, Puente N, Renden R, Wadiche JI, Duvoisin RM, Grandes P, von Gersdorff H. Retroinhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ currents by endocannabinoids released via postsynaptic mGluR activation at a calyx synapse. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5955–5965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0768-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie N, Jeyaraju DV, Peralta MR, 3rd, Seress L, Pellegrini L, Toth K. Vesicular zinc regulates the Ca2+ sensitivity of a subpopulation of presynaptic vesicles at hippocampal mossy fiber terminals. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18251–18265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4164-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hough CJ, Frederickson CJ, Sarvey JM. Induction of mossy fiber --> Ca3 long-term potentiation requires translocation of synaptically released Zn2+ J Neurosci. 2001;21:8015–8025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08015.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima T, Hashimoto K, Yoshida T, Aiba A, Kano M. Presynaptic inhibition caused by retrograde signal from metabotropic glutamate to cannabinoid receptors. Neuron. 2001;31:463–475. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel G, Hevi C, Kane-Goldsmith N, Shumyatsky GP. Zinc transporter ZnT3 is involved in memory dependent on the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2011;223:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel G, Hevi C, Friebely O, Baybutt T, Shumyatsky GP. Zinc transporter 3 is involved in learned fear and extinction, but not in innate fear. Learn Mem. 2010;17:582–590. doi: 10.1101/lm.1962010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maske H. Topochemical detection of zinc in the Ammon’s horn of different mammals. Naturwissennschaften. 1955;42 [Google Scholar]

- Moechars D, Depoortere I, Moreaux B, de Smet B, Goris I, Hoskens L, Daneels G, Kass S, Ver Donck L, Peeters T, Coulie B. Altered gastrointestinal and metabolic function in the GPR39-obestatin receptor-knockout mouse. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1131–1141. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott DD, Benveniste M, Dingledine RJ. pH-dependent inhibition of kainate receptors by zinc. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1659–1671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3567-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima AS, Dyck RH. Zinc and cortical plasticity. Brain Res Rev. 2009;59:347–373. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima AS, Dyck RH. Dynamic, experience-dependent modulation of synaptic zinc within the excitatory synapses of the mouse barrel cortex. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1015–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki C, Vergnano AM, Filliol D, Ouagazzal AM, Le Goff A, Carvalho S, Reiss D, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Neyton J, Paoletti P, Kieffer BL. Zinc alleviates pain through high-affinity binding to the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nn.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Young ED. What’s a cerebellar circuit doing in the auditory system? Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 2001;29:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan E, Zhang XA, Huang Z, Krezel A, Zhao M, Tinberg CE, Lippard SJ, McNamara JO. Vesicular zinc promotes presynaptic and inhibits postsynaptic long-term potentiation of mossy fiber-CA3 synapse. Neuron. 2011;71:1116–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Ascher P, Neyton J. High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1-NR2A receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Vergnano AM, Barbour B, Casado M. Zinc at glutamatergic synapses. Neuroscience. 2009;158:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Noebels JL. Visualization of transmitter release with zinc fluorescence detection at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol. 2005;566:747–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Noebels JL. Exocytosis of vesicular zinc reveals persistent depression of neurotransmitter release during metabotropic glutamate receptor long-term depression at the hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6089–6095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0475-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Walker MC, Fabian-Fine R, Kullmann DM. Endogenous zinc inhibits GABA(A) receptors in a hippocampal pathway. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1091–1096. doi: 10.1152/jn.00755.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi RA, He K, Hartnett KA, Kandler K, Hershfinkel M, Aizenman E. SNARE-dependent upregulation of potassium chloride co-transporter 2 activity after metabotropic zinc receptor activation in rat cortical neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlacek M, Tipton PW, Brenowitz SD. Sustained firing of cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus evokes endocannabinoid release and retrograde suppression of parallel fiber synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15807–15817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindreu C, Palmiter RD, Storm DR. Zinc transporter ZnT-3 regulates presynaptic Erk1/2 signaling and hippocampus-dependent memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3366–3370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019166108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Malinow R. Changes in presynaptic function during long-term potentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;635:208–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb36493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T, Kraus N. Learning to encode timing: mechanisms of plasticity in the auditory brainstem. Neuron. 2009;62:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T, Kim Y, Oertel D, Trussell LO. Cell-specific, spike timing-dependent plasticities in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:719–725. doi: 10.1038/nn1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T, Rubio ME, Keen JE, Trussell LO. Coactivation of pre- and postsynaptic signaling mechanisms determines cell-specific spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee BL. Zinc: biochemistry, physiology, toxicology and clinical pathology. Biofactors. 1988;1:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma N, Carlson GC, Ledent C, Alger BE. Metabotropic glutamate receptors drive the endocannabinoid system in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veran J, Kumar J, Pinheiro PS, Athane A, Mayer ML, Perrais D, Mulle C. Zinc potentiates GluK3 glutamate receptor function by stabilizing the ligand binding domain dimer interface. Neuron. 2012;76:565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt K, Mellor J, Tong G, Nicoll R. The actions of synaptically released zinc at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Miyazaki T, Munechika K, Yamashita M, Ikeda Y, Kamizono A. Isolation of Zn2+ as an endogenous agonist of GPR39 from fetal bovine serum. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2007;27:235–246. doi: 10.1080/10799890701506147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JV, Ren PG, Avsian-Kretchmer O, Luo CW, Rauch R, Klein C, Hsueh AJ. Obestatin, a peptide encoded by the ghrelin gene, opposes ghrelin’s effects on food intake. Science. 2005;310:996–999. doi: 10.1126/science.1117255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]