Abstract

Brucella suis is a facultative intracellular pathogen of mammals, residing in macrophage vacuoles. In this work, we studied the phagosomal environment of these bacteria in order to better understand the mechanisms allowing survival and multiplication of B. suis. Intraphagosomal pH in murine J774 cells was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of opsonized, carboxyfluorescein-rhodamine- and Oregon Green 488-rhodamine-labeled bacteria. Compartments containing live B. suis acidified to a pH of about 4.0 to 4.5 within 60 min. Acidification of B. suis-containing phagosomes in the early phase of infection was abolished by treatment of host cells with 100 nM bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar proton-ATPases. This neutralization at 1 h postinfection resulted in a 2- to 34-fold reduction of opsonized and nonopsonized viable intracellular bacteria at 4 and 6 h postinfection, respectively. Ammonium chloride and monensin, other pH-neutralizing reagents, led to comparable loss of intracellular viability. Addition of ammonium chloride at 7 h after the beginning of infection, however, did not affect intracellular multiplication of B. suis, in contrast to treatment at 1 h postinfection, where bacteria were completely eradicated within 48 h. Thus, we conclude that phagosomes with B. suis acidify rapidly after infection, and that this early acidification is essential for replication of the bacteria within the macrophage.

As a response to bacterial attack, phagocytic cells have developed various instruments to kill pathogens. These antimicrobial defense mechanisms comprise the generation of oxygen radicals during the oxidative burst, the acidification of pathogen-containing phagosomes to a harmful, low pH, and the fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes, allowing pathogen killing by defensins or degradation by lysosomal enzymes. Facultatively intracellular bacteria, in return, have developed various strategies to counteract these host cell assaults, leading to survival and multiplication in macrophages (14): (i) escape from the phagosome into the cytoplasm, as reported for Listeria monocytogenes and Shigella spp. (11), (ii) inhibition of phagosome acidification, associated with (iii) the absence of phagosome-lysosome fusion, as described for mycobacteria, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia trachomatis (10, 18, 19, 20, 32, 40, 42), and (iv) adaptation to acidic phagolysosomes, achieved by Coxiella burnetii and Francisella tularensis (4, 12, 18, 28). Salmonella typhimurium, another facultative intracellular bacterium, survives and replicates in an acidic phagosome as well (38). Pathogens have adapted to these hostile growth conditions, imposing numerous stresses on the bacteria by synthesizing a complex set of specific proteins within the intracellular environment (1, 2). In the case of S. typhimurium, phagosome acidification is essential for the activation of virulence gene transcription via a two-component system (3, 15).

Brucella spp. are gram-negative, facultatively intracellular bacteria divided into six species, which infect humans and animals. These organisms belong to the group that can survive and replicate within host phagocytic cells, and multiplication in phagocytes is crucial to the pathogenesis of Brucella infections (25). It has been shown for Brucella abortus that the bacteria multiply within bovine macrophages (35) and remain enclosed in intracellular compartments during phagocyte infection (17). Similar results have been obtained for B. abortus and B. suis in studies using murine and human monocytes or macrophage-like cell lines (8, 16, 22).

However, very little is known about the intracellular compartment containing Brucella spp., and the environmental conditions that the bacteria encounter. It has not been established whether Brucella spp. inhibit phagosome maturation or whether they have developed mechanisms allowing resistance to bactericidal factors encountered along the normal endocytic pathway of the phagocyte. It has been shown that the chaperones GroEL and DnaK are induced during heat shock, reduced pH, and intracellular survival of B. abortus (26, 36), suggesting harsh conditions inside the phagosome. Earlier, we have demonstrated that DnaK is induced under the same conditions in B. suis and that dnaK inactivation abolishes bacterial multiplication in U937-derived phagocytes (23).

As a consequence of these results and earlier work on other intracellular bacteria suggesting a coordinated gene activation in response to the microenvironment encountered inside the phagosome (29), we contributed in this study to the characterization of B. suis-containing vacuoles. We measured by videofluorescence microscopy the phagosomal pH in murine J774 macrophages infected by B. suis and analyzed the influence of vacuolar pH on survival and replication of the pathogen within the macrophages. Our results demonstrate that Brucella-containing phagosomes acidify rapidly and that an acidic environment during the early phase of infection is necessary for the survival and multiplication of B. suis in macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

N-Hydroxysuccinimidyl ester 5- (and -6)-carboxyfluorescein (NHS-CF), N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester 5- (and -6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (NHS-Rho), and Oregon Green 488 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester (Oregon Green 488) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.); bafilomycin A1 and monensin were purchased from Sigma.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strain used throughout the experiments was B. suis 1330 (ATCC 23444). Bacteria were grown in tryptic soy (TS) broth (Difco Laboratories) at 37°C for 24 h to stationary phase. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and used immediately. Killed organisms were obtained either by incubation at 65°C for 30 min or by incubation at 37°C for 1 h with 300 μg of gentamicin per ml.

Preparation of opsonized bacteria.

B. suis were opsonized with polyclonal murine anti-Brucella antibodies for 30 min at 37°C and washed once in PBS.

Labeling of bacteria with fluorescent probes.

Log-phase cultures (109 bacteria/ml) were washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80. After addition of the mix of fluorescent probes NHS-CF or Oregon Green 488 and NHS-Rho (10 μl of each at 10 mg/ml), the suspension was vortexed. The bacteria were incubated at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. The labeled bacteria were centrifuged, and the reaction was stopped by addition of Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) at a final concentration of 100 mM. The bacteria were again incubated at 4°C for 15 min in the dark, washed twice in PBS, and used immediately for infection. Under these conditions 100% of the bacteria were labeled, as controlled by fluorescence microscopy.

Cell culture.

J774.A1 cells (ATCC TIB 67), a murine macrophage-like cell line, were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco/BRL) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 5 mM glutamine (complete medium) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were resuspended at 105 cells/ml and cultured for 1 day.

Infection and intracellular viability assay of B. suis in J774 cells.

Experiments were performed as described previously (8). Briefly, J774 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 bacteria per cell with stationary-phase B. suis 1330 in RPMI 1640 for 30 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS and reincubated in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf serum and gentamicin at 30 μg/ml for at least 1 h (1 h postinfection). At different time points, cells were washed once with PBS and lysed in 0.2% Triton X-100. Bacterial counts (CFU) were determined by plating serial dilutions on TS agar and incubation at 37°C for 3 days. The relative intracellular survival has been defined as 100% at 1 h postinfection.

Addition of vacuolar-pH-neutralizing reagents to infected cells.

At 1 h postinfection, one of the following reagents was added to J774 cells: 30 mM NH4Cl, 100 nM bafilomycin, or 50 μM monensin. The effect of these substances was studied by determining the number of viable bacteria 3 and 5 h after addition of the reagents. Infected but untreated cells were analyzed in parallel. All experiments were performed in quadruplicate. A possible toxic effect of the substances on B. suis was tested by exposure in TS broth for 5 h followed by viability assays. Macrophage viability was verified by trypan blue dye exclusion assays.

In another set of experiments, NH4Cl (30 mM, final concentration) was added to J774 cells at 90 min and at 7 h after the beginning of infection with B. suis as described above. Infected but untreated cells were analyzed in parallel. The intracellular survival was determined at 1.5, 7, 24, and 48 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Measurement of phagosomal pH by fluorescence microscopy.

J774 cells were cultured in Lab-Tek chambered coverglass (Nunc) with 400 μl per well of a suspension at 105 cells/ml. After 1 day of incubation, cells were infected for 45 min by adding carboxyfluorescein (CF)-Rho or Oregon Green 488-rhodamine (Rho)-labeled bacteria in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (200 μl per well) at a ratio of 100 bacteria per cell. Cells were then washed twice in PBS and incubated in complete medium containing gentamicin at 30 μg/ml to eliminate extracellular bacteria. For pH neutralization, bafilomycin A1 was added at a concentration of 100 nM together with gentamicin at the end of the infection period. At various time points postinfection, the medium was removed and replaced by PBS for observation. For each point, several pairs of images (generally four) were acquired at CF- and Rho-specific wavelengths. Acquisitions were made by videofluorescence microscopy with a Cool View camera (Photonic Science, East Sussex, England) and an image processor linked to an inverted Leica DM IRB microscope (Leica, Rueil-Malmaison, France). Filters used to detect CF or Oregon Green 488 fluorescence consisted of an excitation bandpass filter (450 to 490 nm), a dichroic mirror (510 nm), and an emission bandpass filter (515 to 560 nm). Filters used to detect Rho fluorescence consisted of an excitation bandpass filter (515 to 560 nm), a dichroic mirror (580 nm), and a longpass emission filter (>590 nm). Microscope settings were performed under Rho fluorescence to avoid extensive CF photobleaching, and CF or Oregon Green 488 fluorescence was acquired rapidly. After acquisition, images were analyzed by the imaging system VISIOLAB 1000 (Biocom, Les Ulis, France). For each image, background was defined as the grey-level value corresponding to the majority of pixels. Fluorescent objects were selected by the software on the Rho image (the number of objects per image generally varied from 20 to 50), and the selection was reported on the CF or Oregon Green 488 image. The average grey-level value was calculated for each selection, the background was subtracted from the corresponding value, and the CF/Rho or Oregon Green 488/Rho ratio was calculated for each pair of image. Standard deviations were obtained from the mean of four CF/Rho or Oregon Green 488/Rho ratio values.

An in situ calibration curve of the CF/Rho or Oregon Green 488/Rho emission ratio versus pH was made at the end of each experiment with the same data acquisition parameters (39). Infected J774 were incubated for 1 h in a buffer of defined pH containing 10 μM K+/H+ ionophore nigericin to collapse pH gradients across membranes, 130 mM KCl–30 mM sodium acetate-acetic acid (for pH 3.6, 4.0, 4.5, or 5.0) or 10 μM nigericin–130 mM KCl–30 mM Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 (for pH 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, or 9.0). Pairs of CF-Rho or Oregon Green 488-Rho images were acquired and processed as described above, and a calibration curve was obtained.

RESULTS

Labeling of B. suis with fluorescent probes does not affect bacterial viability and intracellular replication of the bacteria.

The method that we used to determine the pH in Brucella-containing vacuoles was first described by Oh and Straubinger (32) and is based on the fact that CF emission intensity varies with pH whereas Rho fluorescence intensity is independent of pH and is used as a reference signal. The ratio of CF and Rho fluorescence therefore allows calculation of the pH. The fluorescent products NHS-CF and NHS-Rho had to be covalently bound to the surface of the bacteria prior to infection. Compared to control labelings performed with Escherichia coli in preliminary experiments, the efficiency of CF and Rho labeling of B. suis was always lower, regardless of the labeling conditions with respect to concentrations of probes, temperature, or time of incubation (not shown). With heat-killed B. suis, the labeling efficiency was significantly higher, possibly due to alterations of the bacterial cell surface structure. However, the method was validated for the labeling of live B. suis as well, allowing measurement of the pH of phagosomes containing live or nonviable B. suis.

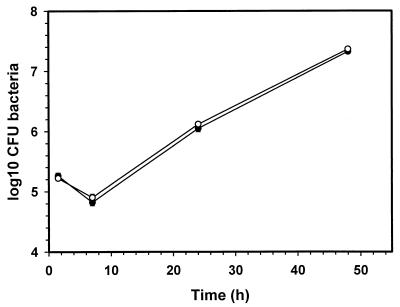

To examine a possible effect of bacterial labeling with the fluorescent marker mixture on viability of B. suis, we compared the viability of dye-labeled bacteria with that of nonlabeled bacteria. There was no significant difference (data not shown). To compare the intracellular behavior within J774 macrophages, we performed infection experiments and monitored the multiplication of labeled and unlabeled opsonized bacteria over a period of 48 h (Fig. 1). The rates of bacterial uptake, as determined by the ratio of CFU at 1 h postinfection to CFU at the end of the 30-min infection period, were identical for unlabeled and labeled bacteria, and both intracellular growth curves showed an identical behavior of the bacteria with respect to survival and replication (Fig. 1), leading to the assumption that binding of the pH probes does not affect the course of the events taking place during phagocytosis and within the Brucella-containing phagosome.

FIG. 1.

Intracellular survival of B. suis 1330 in murine J774 cells. Macrophages were infected with unlabeled (●) and with CF-Rho-labeled (○), opsonized bacteria as described in the text. Each point represents the mean ± standard deviation of three experiments.

Quantitation of pH in individual phagosomes containing B. suis.

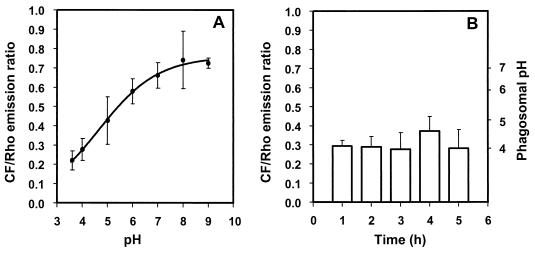

For in situ calibration allowing the calculation of pH from the CF/Rho emission ratio, the ionophore nigericin was used to artificially adjust the intracellular pH to the values defined for the incubation buffers, i.e., pH 3.6, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0. A representative calibration curve is shown in Fig. 2A. For each experiment, an independent calibration curve was established because of variability in labeling intensity and in data acquisition parameters.

FIG. 2.

Acidification of phagosomes containing live B. suis labeled with CF and Rho. Bacteria were labeled with fluorescent probes and then opsonized with specific antibodies. (A) In situ calibration curve for the calculation of phagosomal pH from the CF/Rho emission ratio. Cells infected with live B. suis were incubated in buffers of defined pH containing the ionophore nigericin. The plotted emission ratios represent the means ± standard deviations calculated from the acquisition of four pairs of images for each pH value. (B) Phagosomal pH after infection with live bacteria. At the times indicated, ranging from 1 to 5 h postinfection, four pairs of CF and Rho images were acquired from every observation, and pH was calculated from the calibration curve. Experiments were done in quadruplicate.

Unopsonized B. suis were taken up poorly by J774 cells (1 to 2% infected cells). The rate of phagocytosis was markedly increased (90 to 100% infected cells), however, when the bacteria were opsonized with polyclonal anti-Brucella antibodies. As a consequence, in all experiments performed for the measurement of intraphagosomal pH which required rapid acquisition of a large number of images, B. suis was opsonized before infection. Video-fluorescence microscopy analysis showed that the pH in the phagosomes containing live B. suis decreased to values of pH 4.0 ± 0.5 (Fig. 2B). The rate of acidification was high: at 1 h postinfection, the phagosome was already acidic and remained at this level for at least 5 h, the duration of the experiment. pH values measured at the various time points were not significantly different from one another.

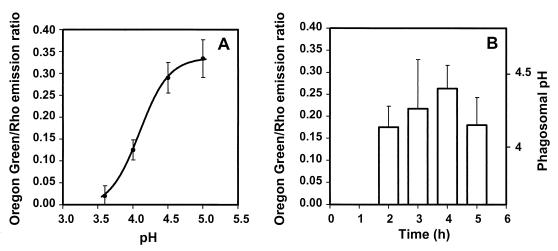

Quantitation of pH in individual phagosomes containing live B. suis, using Oregon Green 488 as reporter of pH.

Fluorescein derivatives are the most widely used pH-sensitive probes, with a pKa of around 6.4, which therefore allows accurate pH measurements in the range 5 to 8. Nevertheless, by using NHS-CF in our experiments, we could determine phagosomal pH values in the range 4 to 8 (Fig. 2A), as also reported previously by Oh and Straubinger (32) and Montcourrier et al. (30). Recently, a new probe, Oregon Green 488, was described as a more appropriate reporter of acid pH, since its pKa of around 4.7 allows a more accurate measurement of pH in the range 3.5 to 6.0 (41) than CF. Oregon Green 488 has the same maximum excitation and emission wavelengths as CF. Using the method described above, we performed experiments with this probe. A representative calibration curve, obtained with Oregon Green 488-Rho-double-labeled B. suis, is shown in Fig. 3A. The pH dependence was optimal between pH 3.6 and 5.0. Our results revealed that the pH inside phagosomes containing live bacteria varied between 4.2 and 4.5 and remained at this level until at least 5 h postinfection (Fig. 3B). These results confirmed those obtained with CF.

FIG. 3.

Acidification of phagosomes containing live B. suis labeled with Oregon Green 488 and Rho. Bacteria were labeled with fluorescent probes and then opsonized with specific antibodies. (A) In situ calibration curve for the calculation of phagosomal pH from the Oregon Green/Rho emission ratio. Cells infected with live B. suis were incubated in buffers of defined pH containing the ionophore nigericin. The plotted emission ratios, represent the means ± standard deviations calculated from the acquisition of four pairs of images for each pH value. (B) Phagosomal pH after infection with live bacteria. At the times indicated, ranging from 2 to 5 h postinfection, four pairs of Oregon green 488 and Rho images were acquired from every observation, and pH was calculated from the calibration curve.

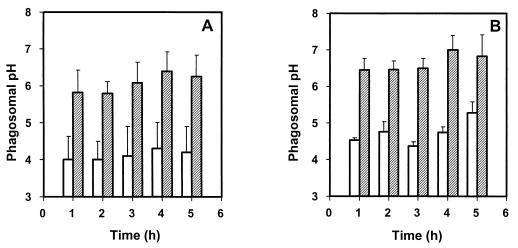

Effect of the specific vacuolar proton-ATPases inhibitor bafilomycin A1 on phagosome acidification.

Vacuolar proton-ATPases participate in the variety of mechanisms that have been found to be implicated in the acidification of vacuoles (27). To investigate the nature of the mechanism responsible for acidification of the compartment containing B. suis, we studied the effect of the macrolide antibiotic bafilomycin A1 on phagosome acidification. BafilomycinA1 has been described as a specific inhibitor of vacuolar ATPases (38), but it has no toxic effect on B. suis (our control experiments [data not shown]) or on other gram-negative bacteria (6). Acidification of the compartment containing live B. suis was inhibited by bafilomycin A1 compared to the vacuoles in untreated cells (Fig. 4A). One hour of treatment with the inhibitor was sufficient to obtain a shift of the pH to about 6.

FIG. 4.

Effect of bafilomycin A1 on acidification of phagosomes containing live or gentamicin-killed B. suis. (A) Phagosomal pH after infection with live bacteria, in the absence (open bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 nM bafilomycin A1, added at the end of the infection period. Live bacteria were labeled with fluorescent probes (CF and Rho) and then opsonized with specific antibodies. (B) Phagosomal pH after infection with killed bacteria, in the absence (open bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 nM bafilomycin A1. Bacteria were first gentamicin killed, labeled with fluorescent probes (CF and Rho), and then opsonized with specific antibodies. Calibration curves were made for each experiment. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

Similar experiments were conducted with gentamicin-killed B. suis (Fig. 4B). Phagosomes containing killed bacteria are usually routed to lysosomes. The pH of the vacuoles containing gentamicin-killed B. suis was rapidly acidified to an average value of 4.5 (1 h postinfection), and again, the pH values measured over the 5 h-period were not significantly different from one another. After treatment with bafilomycin A1, the intraphagosomal pH fluctuated between 6.5 and 7. Thus, the major mechanism of acidification of Brucella-containing vacuoles appeared to be proton pumping via vacuolar proton-ATPases sensitive to bafilomycin.

Effect of bafilomycin A1 and other vacuolar-pH-neutralizing reagents on short-term survival of B. suis in macrophages.

The results described above led us to investigate the importance of low phagosomal pH in the survival and replication of B. suis within J774 cells. In addition to bafilomycin, two other reagents raising the pH of acidic compartments by different mechanisms were used: NH4Cl as a lysosomotrophic substance, and monensin as a cationic ionophore. One hour postinfection, macrophages were treated with the vacuolar-pH-neutralizing reagents, and viable intracellular bacteria were enumerated following recovery 3 and 5 h later, i.e., 4 and 6 h postinfection. Infected but untreated cells were analyzed in parallel.

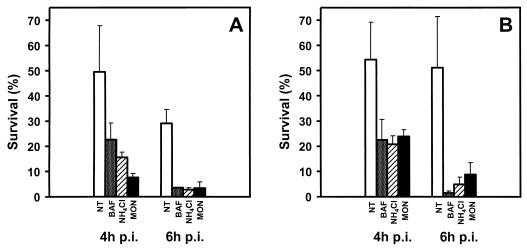

Experiments were performed on bacteria opsonized with specific antibodies as already described for the pH quantitation experiments (Fig. 5A) and on nonopsonized bacteria (Fig. 5B). In both cases, the three reagents significantly decreased the viability of intracellular B. suis. After a 3-h treatment, the number of viable B. suis in J774 cells was clearly reduced; the survival rate was 7.6 to 22.6%, compared to 49.5% for the untreated control. After a 5-h treatment, only 2.8 to 3.6% of the bacteria were recovered, as opposed to 29% for the control (Fig. 5A). With nonopsonized bacteria, the survival of intracellular B. suis varied from 20.8 to 23.9% (untreated control, 54.4%) 3 h after the beginning of the treatments, and only 1.5 to 8.8% survived (untreated control, 51.2%) after 5 h of treatment (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that the observed enhanced decrease in survival and replication of B. suis could be linked to the loss of acidification in the compartment containing the bacteria. Differences in survival observed for all treated samples, compared to the respective untreated controls, were statistically significant (P < 0.01; Student t test). We excluded a direct toxic effect of bafilomycin, NH4Cl, and monensin on the bacteria by incubation for 5 h in TS broth containing the same concentrations of the three reagents as in the J774 infection assays described above. The viability of B. suis was not affected under these conditions (data not shown). To mimic intraphagosomal conditions, we incubated B. suis in TS broth at pH 4 and 6 in the absence and presence of bafilomycin (100 nM) over a period of 24 h and then performed viability assays by serial dilutions and plating at 0, 3, 6, and 24 h of incubation. Viability was not affected in the presence of bafilomycin (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effects of vacuolar-pH-neutralizing reagents on survival of opsonized (A) or nonopsonized (B) B. suis in macrophages. Bafilomycin (BAF; 100 nM), NH4Cl (30 mM), or monensin (MON; 50 μM) was added to J774 cells 1 h postinfection. The number of surviving bacteria was determined 3 and 5 h later (4 and 6 h postinfection [p.i.]). Percentages are indicated with respect to the number of viable bacteria at 1 h, prior to addition of the reagents, considered to be 100%. NT, no treatment (control). All experiments were performed in quadruplicate. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

Early but not late neutralization of vacuolar pH by ammonium chloride inhibits survival of B. suis in J774 macrophages.

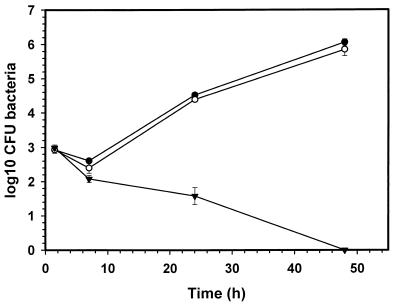

The strong reduction of early intracellular survival of opsonized and nonopsonized B. suis observed in the presence of the three vacuolar-pH-neutralizing agents described above led us to investigate the fate of the intracellular bacteria over a longer period of infection, until 48 h. Our study had to be limited to the effects of NH4Cl, as monensin and bafilomycin were cytotoxic to J774 cells starting at 12 and 24 h postinfection, respectively, whereas 30 mM NH4Cl had no toxic effect until the end of the experiments (not shown). Early neutralization of intracellular compartments at 90 min after the beginning of infection resulted in a constant decline of the bacteria until their complete eradication at 48 h postinfection, as opposed to infection of untreated cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, the addition of NH4Cl to J774 cells at 7 h had no effect on normal intracellular growth of B. suis: after an initial reduction in intracellular viability of 30 to 50%, the bacteria multiplied 800- to 1,000-fold (Fig. 6). These results indicated that for intracellular multiplication of B. suis, an acidic intraphagosomal pH is essential only in the early phase of infection. In our system, neutralization at 6 to 7 h after the first contact of B. suis with the macrophage, i.e., when bacteria began to multiply, did not alter the outcome of infection.

FIG. 6.

Time-dependent effect of the neutralization of cellular compartments by 30 mM NH4Cl on intracellular survival of B. suis 1330 in murine J774 cells. During the course of infection, macrophages remained untreated (●) or were treated with NH4Cl at 90 min (▾) or 7 h (○) after the beginning of infection. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the values represent means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

This work has provided for the first time evidence that in murine macrophages, vacuoles containing live B. suis rapidly acidified to a pH of around 4.0 to 4.5. The mechanism responsible for this acidification was linked to the activity of host cell vacuolar proton-ATPases, which can be specifically inhibited by bafilomycin A1. In our hands, phagosomes containing killed B. suis acidified to pH values of about 4.5 to 4.7, slightly higher than the values obtained for live brucellae. It is interesting to speculate that live B. suis may enhance phagosome acidification by a yet unknown, active mechanism. In analogy to certain results obtained with S. typhimurium (38), acidification was an early and fast event in the process of macrophage infection: the low pH values were measured 1 h after the infection period and remained at that level for at least 5 h, the duration of the experiment. Analysis at time points beyond 5 h was difficult and unreliable with our approach, due to the division of labeled bacteria and hence dilution of the fluorescent markers within the intracellular bacterial population. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that the pH of the phagosomes varies at later stages of infection.

Quantitation of pH has been feasible only with opsonized bacteria, as the rate of phagocytosis is very poor for nonopsonized brucellae, independently of the bacterial species and the origin of the macrophages used (9, 17). As a consequence, we have no direct experimental data proving that the pH is as acidic in phagosomes containing nonopsonized B. suis. Nevertheless, survival and replication of opsonized and nonopsonized bacteria within macrophages were inhibited by bafilomycin A1, suggesting vacuolar acidification in both cases. Recently, Oh and Straubinger (32) found little difference in the environmental pH encountered by opsonized and nonopsonized Mycobacterium avium in the intracellular compartments of J774 cells. Other studies, in contrast, have reported the important role of phagocytosis receptors in the intracellular fate of pathogens (5, 21). In the work described here, phagosome acidification by a vacuolar proton-ATPase(s) was undoubtedly a phenomenon associated with B. suis in murine macrophages, independently of the mechanism of bacterial entry. This can be either Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis involved in uptake of opsonized brucellae or uptake of nonopsonized bacteria that could be mediated by integrins or mannose-binding receptors (7).

Our results furthermore described the survival of B. suis in these acidic compartments. Strong reduction of intracellular bacterial viability by addition of vacuolar-pH-neutralizing reagents may have several reasons: the inhibitors may have side effects on a variety of cellular processes, compromising cell functions necessary for B. suis survival. These effects include inhibition of the interactions between endocytic compartments, dissipation of membrane potentials, and effect on the host cell exocytic pathway. An alternate hypothesis is that the bacterium requires a low-pH environment for survival and multiplication inside the macrophage, at least in the early phase of infection. One explanation for the necessity of an acidic pH in the vacuoles has been given for the intracellular bacterium F. tularensis, where it was found that endosome acidification favors dissociation of iron from transferrin, making it available for the bacteria (12).

On the assumption that B. suis has to be located in an acidic phagosome for survival in macrophages, we defend the hypothesis that low pH acts as an intracellular signal on the regulation of genes involved in survival and multiplication within the phagocytic cell. This has been shown to be true for virulence gene transcription in S. typhimurium, where the acidified phagosome has been previously described as the trigger for PhoP-dependent gene expression (3). Recent studies indicated, however, that changes in pH are not sensed by PhoQ or transmitted to PhoP by a sensor that might respond to pH (15). Two-dimensional gel electrophoretical analysis of protein profiles of the same pathogen revealed that certain subsets of stress-induced proteins are also induced during macrophage infection (1). Studies on proteins of B. abortus induced under stress conditions and during macrophage infection describe the existence of several proteins with increased expression at low pH and inside bovine or murine macrophages (26, 36). We have demonstrated that the molecular chaperone DnaK is induced at low pH in B. suis in vitro and is required for bacterial growth in U937 macrophages (23). Moreover, B. suis maintains its capacity to grow, though slowly, at acid pH as low as pH 4.6 and to resist well pH 3.2 for several hours (24). Thus, acid pH rapidly encountered by B. suis inside the phagosome could be a signal for the induction of a specific set of genes essential for subsequent multiplication within the host cell. The results presented here on the effects of early or late neutralization of Brucella-containing phagosomes on intracellular survival favored this hypothesis. Early neutralization at 1 h postinfection by substances that differ in their mechanisms of action always led to a strong decrease in live intramacrophagic brucellae. Infection assays over 48 h resulted in complete eradication of the bacteria. In contrast, later neutralization, at 7 h, did not affect intracellular multiplication, suggesting that the pH of the phagosome containing B. suis either was still low but not essential for the outcome of infection or had changed to less acidic values. Additional work has to be done on the later stages of brucellae-macrophage interactions to address this question. The characteristic decrease of 30 to 50% in viable intracellular brucellae always observed during the first 7 h of infection might be explained by a lag phase during which part of the bacteria were eliminated before having adapted to this potentially hostile environment. This period coincided with the phase of infection where low pH was essential to allow subsequent multiplication of B. suis. These observations further support the idea of a specific adaptation, possibly by differential gene activation in B. suis during the early phase of infection.

The question is raised whether acidification of phagosomes containing B. suis is linked to phagolysosome fusion. Several reports described a decrease in the fusion of Brucella spp.-containing phagosomes with lysosomes within macrophages (13, 17, 31). Recently, Pizarro-Cerda et al. (33) reported that virulent B. abortus avoid lysosome fusion in HeLa cells. Experiments studying phagolysosome fusion by confocal microscopy revealed that phagosomes containing live B. suis never fused with lysosomes and that in contrast, phagosomes containing killed B. suis fused with these compartments, to be processed along the degradative route of the host cell (34). The process of fusion appeared to be dissociated from the acquisition of a vacuolar proton-ATPase, since phagosome acidification takes place with killed and live bacteria. Fusion and phagosome acidification are clearly regulated by different mechanisms. Live B. suis can avoid killing in the phagosome, either by actively inducing a mechanism which prevents fusion with the lysosome or by following a different, nondegradative route which is still unknown for brucellae but may be similar to that described for S. typhimurium (37). Moreover, our experiments (data not shown) revealed that opsonization of B. suis did not affect intracellular traffic and allowed us to use opsonized bacteria when necessary, for example, for the determination of intraphagosomal pH.

In this study, we reported that phagosomes containing live B. suis are rapidly acidified by a vacuolar proton-ATPase in murine macrophages. The acidic environment is necessary for survival and replication of bacteria within cells. Further investigations on the bacterial factors and the host cell processes involved will contribute to our understanding of the endocytic traffic of B. suis within the macrophage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. F. Huguet for her kind gift of murine anti-Brucella antiserum and J. Teyssier and M. Layssac for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grant PL 980089 from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abshire K Z, Neidhardt F C. Analysis of proteins synthesized by Salmonella typhimurium during growth within a host macrophage. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3734–3743. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3734-3743.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu Kwaik Y, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C. Phenotypic modulation of Legionella pneumophila upon infection of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1320–1329. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1320-1329.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpuche-Aranda C M, Swanson J A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baca O G, Li Y-P, Kumar H. Survival of the Q fever agent Coxiella burnetii in the phagolysosome. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:476–480. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvier G, Benoliel A M, Foa C, Bongrand P. Relationship between phagosome acidification, phagosome-lysosome fusion, and mechanism of particle ingestion. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:729–734. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman E J, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell G A, Adams L G, Sowa B A. Mechanisms of binding of Brucella abortus to mononuclear phagocytes from cows naturally resistant or susceptible to brucellosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;41:295–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron E, Liautard J P, Köhler S. Differentiated U937 cells exhibit increased bactericidal activity upon LPS activation and discriminate between virulent and avirulent Listeria and Brucella species. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:174–181. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caron E, Peyrard T, Köhler S, Cabane S, Liautard J P, Dornand J. Live Brucella spp. fail to induce tumor necrosis factor alpha excretion upon infection of U937-derived phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5267–5274. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5267-5274.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowle A J, Dahl R, Ross E, May M H. Evidence that vesicles containing living, virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium in cultured human macrophages are not acidic. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1823–1831. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1823-1831.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkow S, Isberg R R, Portnoy D A. The interaction of bacteria with mammalian cells. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortier A H, Leiby D A, Narayanan R B, Asafoadjei E, Crawford R M, Nacy C A, Meltzer M S. Growth of Francisella tularensis LSV in macrophages: the acidic intracellular compartment provides essential iron required for growth. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1478–1483. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1478-1483.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frenchick P J, Markham J F, Cochrane A H. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages by soluble extracts of virulent Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:332–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-del Portillo F, Finlay B B. The varied lifestyles of intracellular pathogens within eukaryotic vacuolar compartments. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Véscovi E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halling S M, Detilleux P G, Tatum F M, Judge B A, Mayfield J E. Deletion of the BCSP31 gene of Brucella abortus by replacement. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3863–3868. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3863-3868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmon B G, Adams L G, Frey M. Survival of rough and smooth strains of Brucella abortus in bovine mammary gland macrophages. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:1092–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinzen R A, Scidmore M A, Rockey D D, Hackstadt T. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:796–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.796-809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz M A. The Legionnaire’s disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2108–2126. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horwitz M A, Maxfield F R. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1936–1943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joiner K A, Fuhrman S A, Miettinen H M, Jasper L H, Mellman I. Toxoplasma gondii: fusion competence of parasitophorous vacuoles in Fc receptor transfected fibroblasts. Science. 1990;249:641–646. doi: 10.1126/science.2200126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones S M, Winter A J. Survival of virulent and attenuated strains of Brucella abortus in normal and gamma interferon-activated murine peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3011–3017. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.3011-3014.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhler S, Teyssier J, Cloeckaert A, Rouot B, Liautard J P. Participation of the molecular chaperone DnaK in intracellular growth of Brucella suis within U937-derived phagocytes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:701–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulakov Y K, Guigue-Talet P G, Ramuz M R, O’Callaghan D. Response of Brucella suis 1330 and B. canis RM6/66 to growth at acid pH and induction of an adaptative acid tolerance response. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)87645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liautard J P, Gross A, Dornand J, Köhler S. Interactions between professional phagocytes and Brucella spp. Microbiologia. 1996;12:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, Ficht T. Protein synthesis in Brucella abortus induced during macrophage infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1409–1414. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1409-1414.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacs G L, Rotstein O D, Grinstein S. Phagosomal acidification is mediated by a vacuolar-type H+-ATPase in murine macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21099–21107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurin M, Benoliel A M, Bongrand P, Raoult D. Phagolysosomes of Coxiella burnetii-infected cell lines maintain an acidic pH during persistent infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5013–5016. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5013-5016.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J F, Mekalanos J J, Falkow S. Coordinate regulation and sensory transduction in the control of bacterial virulence. Science. 1989;243:916–922. doi: 10.1126/science.2537530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montcourrier P, Mangeat P H, Valembois C, Salazar G, Sahuquet A, Duperray C, Rochefort H. Characterization of very acidic phagosomes in breast cancer cells and their association with invasion. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2381–2391. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.9.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberti J, Caravano R, Roux J. Attempts of quantitative determination of phagosome-lysosome fusion during infection of mouse macrophages by Brucella suis. Ann Immunol (Inst Pasteur) 1981;132D:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh Y K, Straubinger R B. Intracellular fate of Mycobacterium avium: use of dual-label spectrofluorometry to investigate the influence of bacterial viability and opsonization on phagosomal pH and phagosome-lysosome interaction. Infect Immun. 1996;64:319–325. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.319-325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege J L, Gorvel J P. Virulent Brucella abortus avoids lysosome fusion and distributes within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porte, F. Unpublished results.

- 35.Price R E, Templeton J W, Smith III R, Adams L G. Ability of mononuclear phagocytes from cattle naturally resistant or susceptible to brucellosis to control in vitro intracellular survival of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:879–886. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.879-886.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafie-Kolpin M, Essenberg R C, Wyckoff J H., III Identification and comparison of macrophage-induced proteins and proteins induced under various stress conditions in Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5274–5283. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5274-5283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathman M, Barker L P, Falkow S. The unique trafficking pattern of Salmonella typhimurium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages is independent of the mechanism of bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1475–1485. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1475-1485.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rathman M, Sjaastad M D, Falkow S. Acidification of phagosomes containing Salmonella typhimurium in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2765–2773. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2765-2773.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schramm N, Bagnell C R, Wyrick P B. Vesicles containing Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 remain above pH 6 within HEC-1B cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1208–1214. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1208-1214.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P H, Chakraborty P, Haddix P L, Collins H L, Fok A K, Allen R D, Gluck S L, Heuser J, Russell D G. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergne I, Constant P, Lanéelle G. Phagosomal pH determination by dual fluorescence flow cytometry. Anal Biochem. 1998;255:127–132. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu S, Cooper A, Sturgill-Koszycki S, van Heyningen T, Chatterjee D, Orme I, Allen P, Russell D G. Intracellular trafficking in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-infected macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:2568–2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]