Abstract

Copper is an essential co-factor for all organisms, and yet it becomes toxic if concentrations exceed a threshold maintained by evolutionarily conserved homeostatic mechanisms. How excess copper induces cell death, however, is unknown. Here, we show in human cells that copper-dependent, regulated cell death is distinct from known death mechanisms, and is dependent on mitochondrial respiration. We show that copper-dependent death occurs via direct binding of copper to lipoylated components of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This results in lipoylated protein aggregation and subsequent iron-sulfur cluster protein loss leading to proteotoxic stress and ultimately cell death. These findings may explain the need for ancient copper homeostatic mechanisms.

One sentence summary:

Copper-induced cell death is regulated by mitochondrial ferredoxin 1-mediated protein lipoylation.

The requirement of copper as a co-factor for essential enzymes has been recognized across the animal kingdom, spanning bacteria to human cells (1). However, intracellular copper concentrations are kept at extraordinarily low levels via active homeostatic mechanisms that work across concentration gradients in order to prevent the accumulation of free intracellular copper that is detrimental to cells (1–4). Whereas the mechanism of toxicity of other essential metals, such as iron, are well-established, the mechanisms of copper-induced cytotoxicity remain unclear (5–7).

Copper ionophores are copper-binding small molecules that shuttle copper into the cell, and are thereby useful tools to study copper toxicity (8, 9). Multiple lines of evidence indicate that the mechanism of copper ionophore-induced cell death involves intracellular copper accumulation and not the effect of the small molecule chaperones themselves. Multiple, structurally distinct small molecules that bind copper share killing profiles across hundreds of cell lines (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A and (5, 10)). Structure-function relationship experiments show that modifications that abrogate the copper binding capacity of these compounds result in loss of cell killing (5), and copper chelation eliminates the cytotoxicity of the compounds (fig. S1, B to C and (5)).

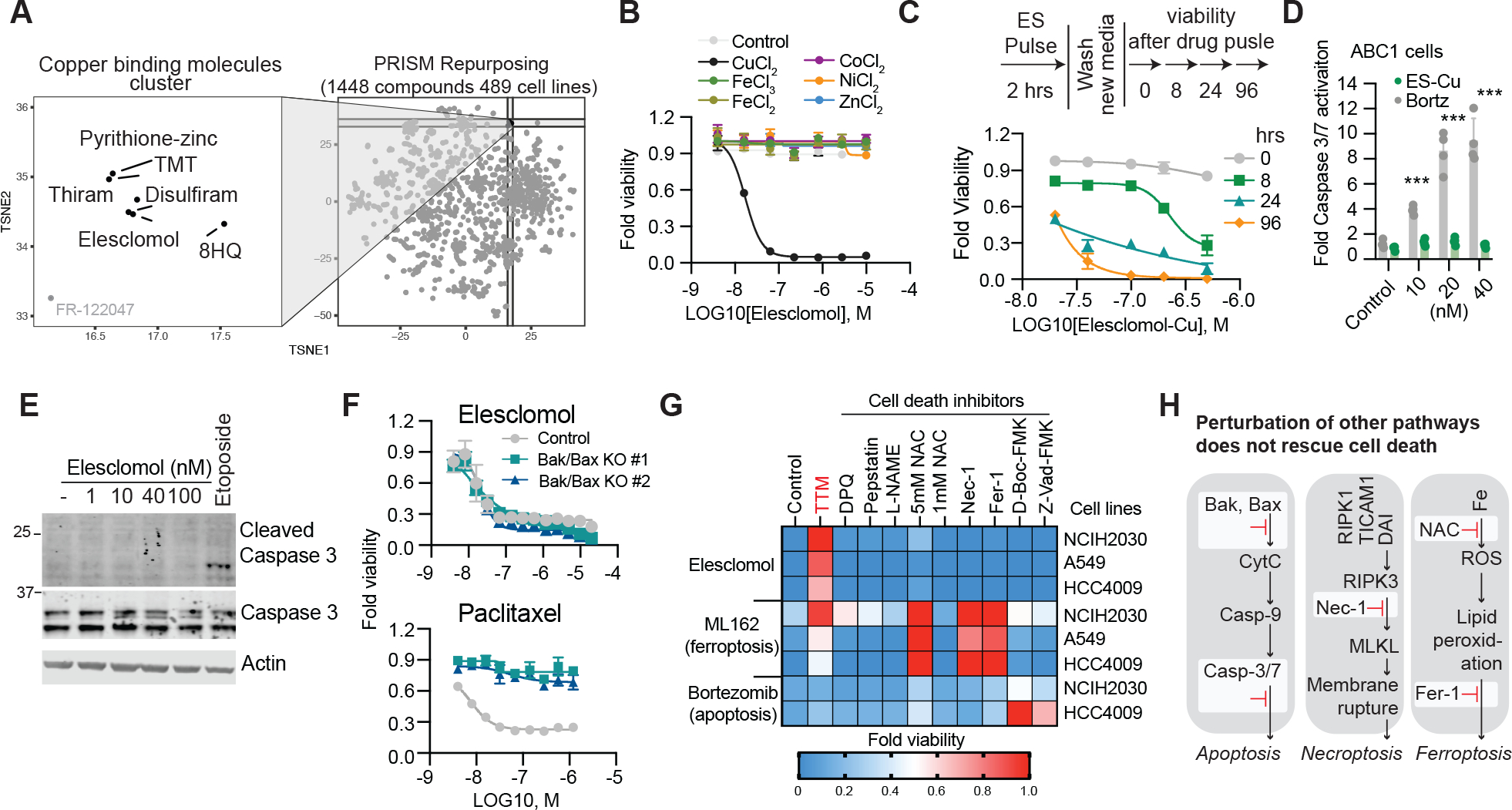

Figure 1. Copper ionophore-induced cell death is non-apoptotic, non-ferroptotic and non-necroptotic.

(A) PRISM Repurposing Secondary screen - growth-inhibition estimates for 1,448 drugs against 489 cell lines. (B) Viability of cells (MON) after treatment with elesclomol ± 10μM of indicated metals. (C) Viability of ABC1 cells was assessed at the indicated times after elesclomol-Cu (1:1 ratio) pulse treatment and growth in fresh media (D) Caspase 3/7 cleavage in ABC1 cells after 16 hours following indicted treatments (fold change over control). (E) G402 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of elesclomol or 25μM etoposide for 6 hours. (F) Viability of HMC18 cells or two HMC18 clones with Bax/Bak deleted after treatment with elesclomol-CuCl2 (1:1) (top) and paclitaxel (bottom). (G) Heatmap of viability of cells pretreated overnight with 20μM necrostatin-1, 10μM ferrostatin-1, 1mM and 5mM N-Acetylcysteine, 30μM Z-VAD-FMK, 50μM D-Boc-FMK, 20μM TTM, 300μM L-NAME, 1μM Pepstatin A and 10μM DPQ and then treated with either 30nM elesclomol-CuCl2 (1:1), 1μM ML162 (GPX4 inhibitor) or 40nM bortezomib for 72h (average of three replicas).(H) Schematic diagram of apoptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis. Inhibited pathways are marked in red. (B, D and F) mean ± SD, n≥3. (D,E) media supplemented with 1μM CuCl2

A clear picture of the mechanisms underlying copper-induced toxicity has not yet emerged, with contradictory reports suggesting either the induction of apoptosis(11, 12), caspase-independent cell death (5, 7, 13), ROS induction(14–16), or inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (17–19). The cross-kingdom efficacy of copper binding molecules as cell death inducers suggests that they target evolutionarily conserved cellular machinery, but such mechanisms have yet to be elucidated.

To further establish whether copper ionophore cytotoxicity is dependent on copper itself, we analyzed the killing potential of the potent copper ionophore, elesclomol. The source of copper in cell culture medium is serum (fig. S1D), and accordingly, cells grown in the absence of serum were resistant to elesclomol. In contrast, elesclomol sensitivity was completely restored by the addition of copper in a 1:1 ratio (fig. S1, E and F). Copper supplementation similarly sensitized cells to treatment with six structurally distinct copper ionophores (Fig. 1B and fig. S1, G to P), but supplementation with other metals including iron, cobalt, zinc and nickel failed to potentiate cell death (Fig. 1B, and fig. S1, G to P). Consistent with this observation, depletion of the endogenous intracellular copper chelator glutathione, using buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), sensitized cells to elesclomol-copper induced cell death (fig. S1Q), whereas chelation of copper with tetrathiomolybdate (TTM) rescued killing (fig. S1, B to C) while chelators of other metals had no effect (fig. S1R). Lastly, 2 hour pulse treatment with potent copper ionophores (elesclomol, disulfiram and NSC319726) resulted in a ~5–10 fold increase in levels of intracellular copper but not zinc (fig. S2A). These results suggest that copper ionophore-induced cell death is primarily dependent upon intracellular copper accumulation.

Copper ionophores induce a distinct form of regulated cell death

We first asked if copper ionophore-mediated cell death is regulated, and specifically whether short-term exposure leads to irrevocable, subsequent cell cytotoxicity. Pulse treatment with the copper ionophore elesclomol at concentrations as low as 40 nM for only 2 hours resulted in a 15- to 60-fold increase in intracellular copper levels (fig. S2, B to C) that triggered cell death more than 24 hours later (Fig. 1C). This result suggests that copper-mediated cell death is indeed regulated.

Cell death involves signaling cascades and molecularly-defined effector mechanisms (20) involving proteins and lipids such as those characteristic of apoptosis (21), necroptosis (22), pyroptosis (23) and ferroptosis (24), which is a recently discovered iron-dependent cell death pathway. Previous reports suggested that elesclomol induces ROS-dependent apoptotic cell death (6, 12), but elesclomol-induced cell death did not involve either the cleavage or activation of caspase 3 activity, the hallmark of apoptosis (25) (Fig. 1, D to E, and fig. S2D). Similarly, elesclomol killing potential was maintained when the key effectors of apoptosis, BAX and BAK1, were knocked out (Fig. 1F and fig. S2, E to I) or when cells were co-treated with pan-caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD-FMK and Boc-D-FMK) (Fig. 1G), again indicating the copper-induced cell death is distinct from apoptosis. Furthermore, treatment with inhibitors of other known cell death mechanisms including ferroptosis (ferrostatin-1), necroptosis (necrostatin-1), oxidative stress (N-acetyl cysteine) all failed to abrogate copper ionophore-induced cell death (Fig. 1G), suggesting a mechanism distinct from known cell death pathways (Fig. 1H).

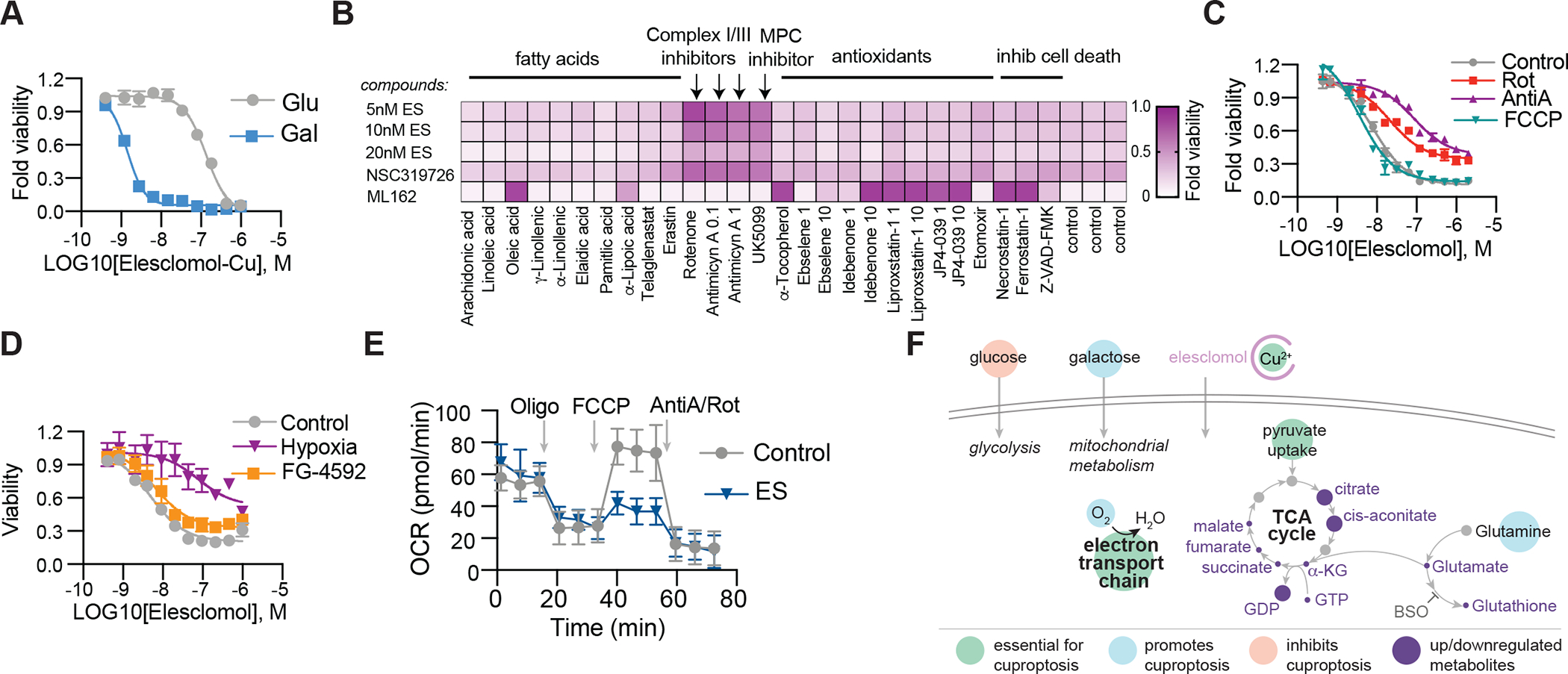

Mitochondrial respiration regulates copper ionophore induced cell death

One hint to the pathways that mediate copper ionophore-induced cell death is the observation that cells more reliant on mitochondrial respiration are nearly 1,000-fold more sensitive to copper ionophores than cells undergoing glycolysis (Fig. 2A, and fig. S3, A to F). Treatment with mitochondrial antioxidants, fatty acids, and inhibitors of mitochondrial function had a very distinct effect on the sensitivity to copper ionophores as compared to sensitivity to the ferroptosis-inducing GPX4 inhibitor ML162 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, inhibitors of complex I and II of the electron transport chain (ETC) as well as inhibitors of mitochondrial pyruvate uptake attenuated cell death with no effect on ferroptosis (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP had no effect on copper toxicity, suggesting that mitochondrial respiration, not ATP production, is required for copper-induced cell death (Fig. 2C). Consistent with this finding, growing cells in hypoxic conditions (1% O2) attenuated copper ionophore induced cell death, whereas forced stabilization of the HIF pathway with the HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 under normoxic conditions (21% O2) did not (Fig. 2D and fig. S3, G to J), further emphasizing the role of cellular respiration in mediating copper-induced cell death. However, treatment with copper ionophores did not induce significant reduction in basal or ATP-linked respiration, but rather significantly reduced the spare capacity of respiration (Fig. 2E and fig. S3, K to N) suggesting that copper does not target the ETC directly but rather components of the TCA cycle. In support of this, metabolite profiling of cells pulse-treated with elesclomol showed a time-dependent increase in metabolite dysregulation of many TCA cycle-associated metabolites in elesclomol-sensitive ABC1 cells but not in elesclomol-resistant A549 cells (table S1 and fig. S3, O to S). These results establish a link between copper ionophore induced cell death and mitochondrial metabolism, not the ETC (Fig. 2F), leading us to further elucidate the precise connection between copper and the TCA cycle.

Figure 2. Mitochondria respiration regulates copper ionophore induced cell death.

(A) Viability of NCIH2030 cells grown in media containing either glucose or galactose treated with elesclomol-Cu (ratio 1:1). (B) Viability of ABC1 cells pretreated with indicated compounds (x-axis) and then treated with elesclomol (ES), NSC319726 or ML162 (y-axis). Average of at least three replicas is plotted and color coded. (C) Viability of ABC1 cells pretreated with 0.1μM rotenone (Rot), 0.1μM Antimycin A (AntiA) or 1μM FCCP and then treated with elesclomol. (D) Viability of ABC1 cells grown in control (21% O2), hypoxia (1% O2) or 50 μM FG-4592 (21% O2) after treatment with elesclomol. (E) The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was detected following treatment with 2.5 nM elesclomol (+1μM CuCl2 in media) for 16 hours of ABC1 cells before (basal) and after the addition of oligomycin (ATP-linked), the uncoupler FCCP (maximal), or the electron transport inhibitor antimycin A/rotenone (baseline) (mean ± SD, n= 8). (F) Schematic of metabolites altered following elesclomol treatment of ABC1 cells (purple circles mark metabolites changing abundance as detailed in table S1. Larger circles –metabolites upregulated, smaller circles- metabolites downregulated). (A, C and D) mean ± SD, n≥ 3.

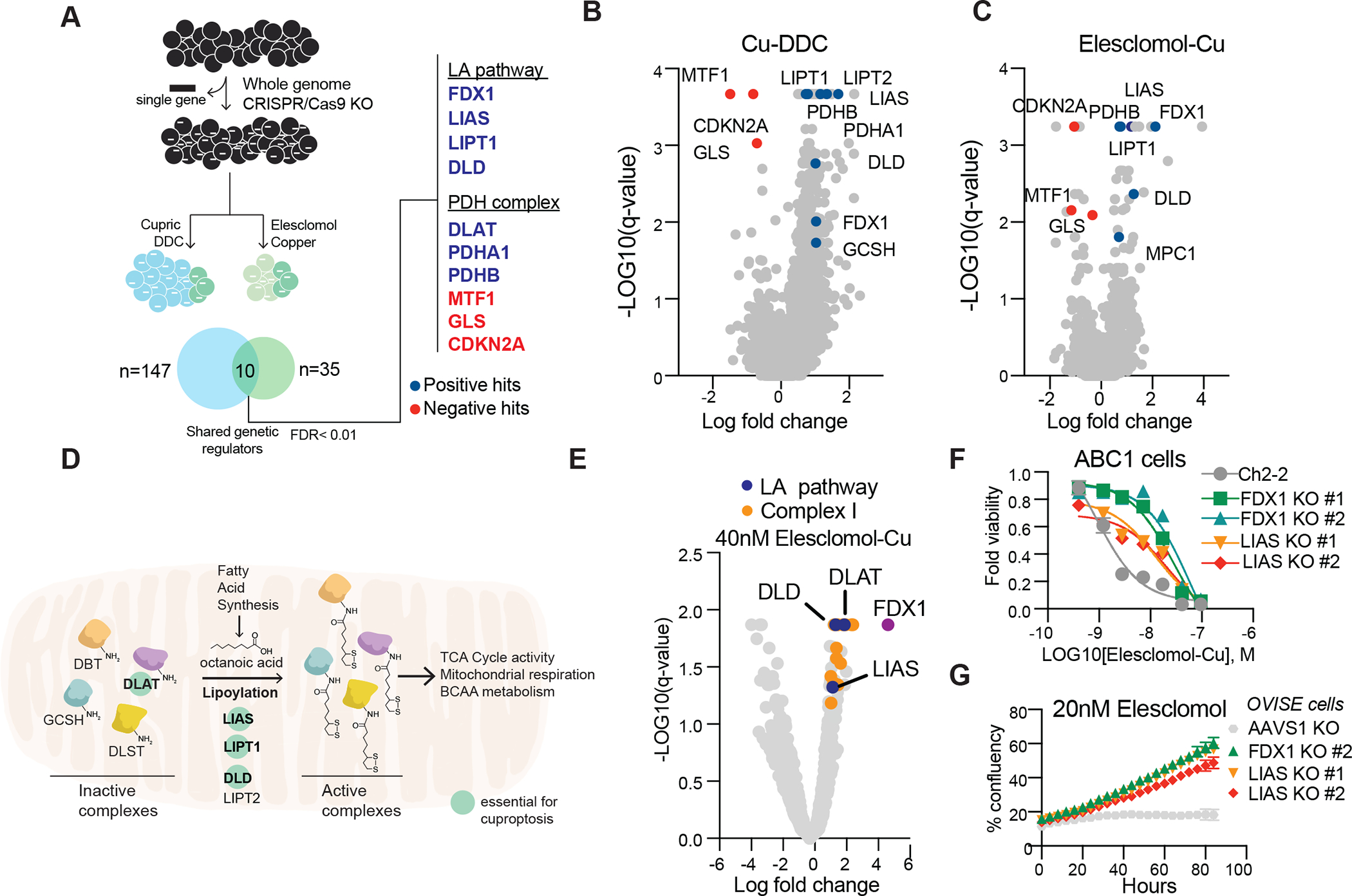

FDX1 and protein lipoylation are the key regulators of copper ionophore induced cell death

To identify the specific metabolic pathways that mediate copper toxicity, we performed genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 loss-of-function screens to identify the genes involved in copper ionophore-induced death. To maximize the generalizability of the screen, we focused on the intersection of two structurally distinct copper-loaded ionophores (elesclomol and the active form of disulfiram, diethyldithiocarbamate) (table S2 and Fig. 3, A to C). Killing by both compounds was rescued by knockout of seven genes (Fig. 3A marked in blue), including FDX1 (a reductase known to reduce Cu2+ to its more toxic form, Cu1+, and to be a direct target of elesclomol (5)) and six genes that encode either components of the lipoic acid pathway (LIPT1, LIAS and DLD) or protein targets of lipoylation (the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex including DLAT, PDHA1 and PDHB (26) (Fig. 3D). These observations were validated by an independent knock-out screen focusing on 3,000 metabolic enzymes (27) (table S2 and Fig. 3E and fig. S4, A and B). The metabolic enzyme screen also showed that genetic suppression of complex I also rescued cells from copper-induced death (table S2 and Fig. 3E and fig. S4, A and B) consistent with our finding that chemical inhibitors of the ETC block cell death mediated by copper ionophores (Fig. 2).

Figure 3. FDX1 and lipoic acid genes are critical mediators of copper ionophore-induced cell death.

(A-C) Whole genome CRIPSR/Cas9 positive selection screen using two copper ionophores (Cu-DDC and elesclomol-copper) in OVISE cells (schematic on the left). Overlapping hits with FDR score< 0.01 were analyzed (right). Positive hits (resistance) are marked in blue, negative hits (sensitizers) in red (B-C) Summary scatter of the screen results for Cu-DDC (B) or elesclomol-copper (C). (D) Schematic of the lipoic acid (LA) pathway. Genes that scored in our genetic screens are marked as essential for copper-induced cell death. (E) Summary scatter indicating top hits in metabolism gene focused CRISPR–Cas9 gene knockout screen of A549 cells treated with 40nM of elesclomol-Cu(II) (1:1 ratio). Genes associated with the lipoic acid pathway are marked in blue, complex I related genes in orange and FDX1 in purple. (F) Viability of ABC1 cells with CRIPSR/Cas9 deletion of LIAS or FDX1 following treatment with elesclomol in the presence of 1μM CuCl2 in the media. (G) Growth curve measurements of OVISE cells with CRIPSR/Cas9 deletion of LIAS and FDX1 in the presence of 20nM elesclomol. (F-G) mean ±SD of n≥3.

Individual gene knock-out studies further confirmed that deletion of FDX1 and LIAS (lipoyl synthase) conferred resistance to copper-induced cell death (Fig. 3, F to G and fig. S4, C to K), further strengthening a functional link between FDX1, the protein lipoylation machinery and copper toxicity. Moreover, FDX1 deletion resulted in consistent resistance to a number of copper ionophores (disulfiram, NSC319726, Thiram, 8-HQ and Zn-Pyrithione) (fig. S5, A to G) but showed no significant effects on either caspase activation (fig S5, H to K), the potency of apoptosis-inducers (bortezomib, paclitaxel and topotecan) or the ferroptosis-inducer ML162 (fig. S5, L to O). Of note, the strong connection between copper-mediated cell death and both FDX1 expression and protein lipoylation was lost at high concentrations of elesclomol (>40 nM) (fig. S4, L to P), thereby suggesting that off-target mechanisms of cell death may occur at such concentrations, and possibly explaining conflicting mechanisms of action reported in the literature (5, 7, 14–16, 19, 28, 29). Moreover, whereas the most copper-selective compounds (e.g. elesclomol, disulfiram and NSC319726) lost killing activity when cells were grown under glycolytic conditions, compounds with more promiscuous metal-binding compounds (e.g. pyrithione and 8-HQ) killed independent of metabolic state. This result is consistent with copper’s unique connection to mitochondrial metabolism-mediated protein lipoylation. (Fig. 2A, fig. S3, A to F and fig. S5, A to G).

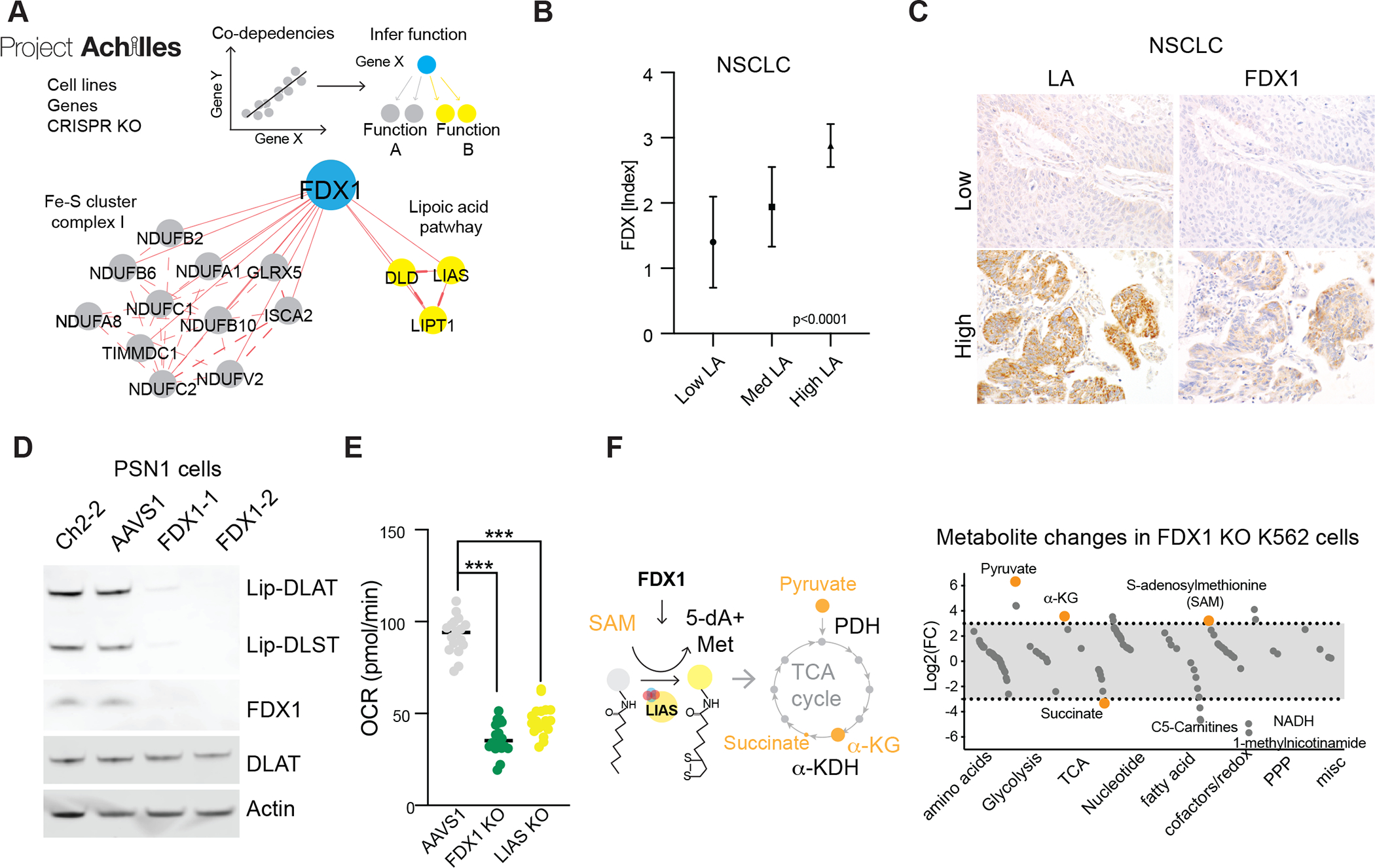

FDX1 is an upstream regulator of protein lipoylation

Protein lipoylation is a highly conserved lysine post-translational modification known to occur on only four enzymes, all of which involve metabolic complexes that regulate carbon entry points to the TCA cycle (26, 30). These include DBT (Dihydrolipoamide Branched Chain Transacylase E2), GCSH (Glycine Cleavage System Protein H), DLST (Dihydrolipoamide S-Succinyltransferase) and DLAT (Dihydrolipoamide S-Acetyltransferase), an essential component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex. Lipoylation of these proteins is known to be required for enzymatic function (30) (Fig. 3D). Our findings that knock-out of either FDX1 or lipoylation-related enzymes rescues cells from copper toxicity led us to explore whether FDX1 might be an upstream regulator of protein lipoylation. To test this hypothesis, we performed three analyses. First, we looked for evidence of coordinated dependencies across the Cancer Dependency Map (www.depmap.org), a resource of genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out screens in hundreds of cancer cell lines. Genes showing similar patterns of viability effects, even if subtle, suggest that they have shared function or regulation. Strikingly, FDX1 and components of the lipoic acid pathway were highly correlated in their viability effects across the cell line panel (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. FDX1 is an upstream regulator of protein lipoylation.

(A) Correlation analysis of gene dependencies taken from the Achilles project; presented is the gene network that correlates with FDX1 deletion using FIREWORKS (51). The correlating genes are marked by their described functionality (lipoic acid pathway and mitochondria complex I and Fe-S cluster regulation). (B) A tissue microarray (TMA) of Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) (n=57) were stained with LA and FDX IHC and expression was scored semi-quantitatively by two pathologists (S.C., S.S.), showing a strong direct correlation between LA and FDX expression (mean ± S.D.; p<0.0001). (C) Representative cases of NSCLC with correlated low (top-row) and high (bottom-row) expression of LA and FDX1 by IHC (scale bars 20μm). (D) Immunoblot of lipoylated proteins, FDX1, DLAT and actin from extracts of PSN1 cells with deletion of FDX1. (E) Basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) as measured in PSN1 cells with CRIPSR/Cas9 deletion of FDX1, LIAS or AAVS1 genes (unpaired t-test *** p< 0.001). (F) Plot of the average Log2 fold change in metabolites between FDX1 KO and AAVS1 control K562 cell lines separated by functional annotations. Metabolites relevant to the lipoic acid pathway are marked in orange.

Second, we performed immunohistochemical staining for FDX1 and lipoic acid in 208 human tumor specimens and semi-quantitative light-microscopic scoring by two independent pathologists. Expression of FDX1 and lipoylated proteins were highly correlated (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4, B and C and fig. S6 A to D). Third, we determined whether FDX1 knock-out impacted protein lipoylation using a lipoic acid-specific antibody as a measure of DLAT and DLST lipoylation. FDX1 knock-out resulted in complete loss of protein lipoylation as measured either by immunoblot or immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4D and fig. S6, E to I) and also led to a significant drop in cellular respiration similar to the levels observed with the deletion of the LIAS itself (Fig. 4E and fig. S6J). Furthermore, metabolite profiling following deletion of FDX1 led to an accumulation of pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate, and depletion of succinate, as would be expected when protein lipoylation is compromised due to inhibition of the TCA cycle at PDH and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGD) (31) (table S3 and Fig. 4F). Also of interest, we observed an increase in S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), a key substrate of LIAS in the lipoic acid pathway, consistent with FDX1 being a previously unrecognized upstream regulator of protein lipoylation.

Copper directly binds and induces the oligomerization of lipoylated DLAT

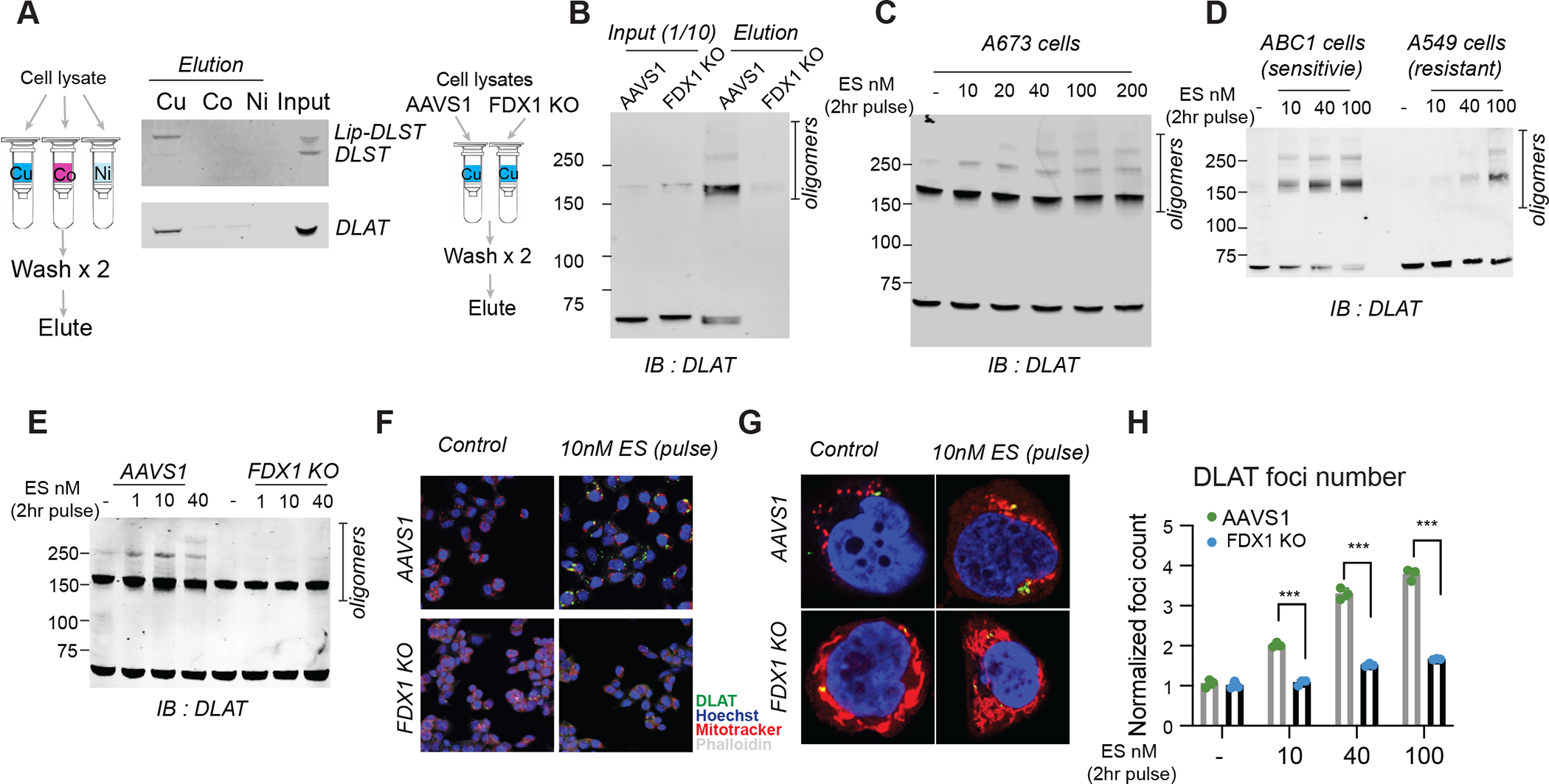

The experiments described above establish a connection between copper toxicity and protein lipoylation, but do not establish a direct mechanistic link. We hypothesized that copper might directly bind to lipoylated proteins, a possibility suggested by the observation that copper binds free lipoic acid with a measured KD of 10−17 (32). To test this hypothesis, we purified DLAT and DLST from cell lysates and found that these proteins bound to Cu-charged resin, but not to cobalt or nickel resins (Fig. 5A). When protein lipoylation was abrogated by FDX1 deletion (Fig. 4), DLAT and DLST no longer bound copper (Fig. 5B) suggesting that the lipoyl moiety is required for copper binding.

Figure 5. Copper directly binds and promotes the oligomerization of lipoylated DLAT.

(A) The binding of indicated proteins to copper (Cu), Cobalt (Co) and Nickel (Ni) was assessed by immunoblot analysis of eluted proteins from the indicated metal loaded resins. (B) Copper binding was assessed by loading cell lysates from either ABC1 AAVS1 or FDX1 KO cells on copper loaded resin followed by washing and analysis of the eluted proteins. Input and eluted proteins are presented. (C) Protein content was analyzed in A673 cells that were pulse (2hr) treated with the indicated concentrations of elesclomol. (D) Protein content was analyzed in ABC1 and A549 cells that were pulse treated with the indicated concentrations of elesclomol. (E-H) AAVS1 control or FDX1 KO ABC1 cells were pulse treated with indicated concentrations of elesclomol for 2 hours; protein oligomerization was analyzed after 24 hours by immunoblotting (E) and both wide-field (F) and confocal (G) immunofluorescence imaging (DLAT - green, Mitotracker- red, Hoechst -blue, phalloidin -white). (H) Foci were segmented and quantified in each condition(n=3, multiple unpaired t-test analysis was conducted with desired FDR(Q)= 1% *** q< 0.001). (C-H) 1μM CuCl2 was supplemented to the media.

We noted that copper binding to lipoylated proteins did not simply lead to loss of function, given that deletion of the proteins rescues (not phenocopies) copper ionophore treatment. We proposed that copper binding to lipoylated TCA cycle proteins results in a toxic gain of function. Interestingly, we found that the copper binding to lipoylated TCA cycle proteins resulted in lipoylation-dependent oligomerization of DLAT detectable by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5, B and C). Similarly, treatment of elesclomol-sensitive cells increased levels of DLAT oligomers and insoluble DLAT, whereas treatment of elesclomol-insensitive cell lines or FDX1 KO cells resulted in DLAT oligomerization only at much higher concentrations (Fig. 5, D and E and fig. S7, A and B). Treatment with the strong reducing agent TCEP and boiling eliminated the oligomeric form of DLAT (fig. S7, C to E), suggesting that the aggregates are disulfide bond-dependent. We confirmed these findings by immunofluorescence, observing pronounced induction of DLAT foci by short-pulse elesclomol treatment, whereas such foci were diminished in FDX1 knock-out, lipoylation-deficient cells (Fig. 5, F to H and fig. S7F). These findings support a model where the toxic gain of function of lipoylated proteins following exposure to copper ionophores is mediated at least in part by their aberrant oligomerization. Mass spectrometric analysis also revealed that copper ionophore treatment leads to loss of Fe-S cluster proteins (Fig. 6, A and B) in an FDX1-dependent manner (Fig. 6C) as well as the induction of proteotoxic stress (table S4 and Fig. 6, B and C and fig. S8A). These findings are consistent with the observation in bacteria and yeast that copper can destabilize Fe-S containing proteins (33–35). Whether such loss of Fe-S cluster proteins contributes to the copper ionophore death phenotype remains to be determined.

Figure 6. Shared mechanisms in chemically and genetically induced copper dependent cell death.

(A) Proteomic analysis of control and elesclomol (100nM) pulse-treated ABC1 cells 24h post-treatment. Top (GO) enriched categories are presented (table S4). (B-C) Protein content in A673 (B) and AAVS1 and FDX1-KO ABC1 cells (C) 16h after 2h-pulse-treatment with elesclomol. (A-C) performed with 1μM CuCl2 supplementation. (D) Copper homeostasis schematic. (E-F) 293T cells overexpressing GFP or SLC31A1 analyzed for viability 72h post-supplementation with CuCl2 and (E) for protein content 24h post-treatment (F). (G) SLC31A1-overexpressing cells were pre-treated with 10μM necrostatin-1, 10μM ferrostatin-1, 100μM α-Tocopherol, 40μM Z-VAD-FMK, 10μM tetrathiomolybdate or 40μM Bathocuproinedisulfonic acid; Viability was measured after 72 hours of cells growing in the presence or absence of 3 μM CuCl2. (H) Viability of ABC1 Ch2–2, FDX1, and LIAS-KO cells overexpressing SLC31A1 was analyzed 72h post-treatment with 2μM CuCl2. In (G) and (H) viability is presented as box and whiskers plots representing interquartile ranges (boxes), medians (horizontal lines), and range (whiskers). For both, n≥5, and an ordinary one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (****adjusted p-value<0.0001). (I) Viability of control and 100μM BSO-pretreated A549 cells 48h post-treatment with indicated metals. Average of three replicas plotted. (J) Viability of control, FDX1 and LIAS-KO HEK293T cells pretreated with 20μM BSO and then with CuCl2. (K) Protein content in Atpb7b−/− mouse livers (≥5 Atp7b−/−) compared to control (six Atp7b +/−; one wt). Multiple unpaired t-test analysis were conducted ***q< 0.001, **q< 0.01. (L) Schematic of mechanisms promoting copper-induced cell death. (E, J) mean ±SD of n≥4.

Copper-induced death mechanisms are shared by genetic models of copper homeostasis dysregulation

The experiments described to this point utilize copper ionophores to overcome the homeostatic mechanisms that normally keep intracellular copper concentration low. These mechanisms include the copper importer SLC31A1 (CTR1) and the copper exporters ATP7A and ATP7B, encoded by genes mutated in copper dysregulation syndromes Menke’s disease and Wilson’s disease, respectively (3, 36) (Fig. 6D). To explore whether the mechanisms of copper toxicity associated with copper ionophore treatment are shared by these naturally occurring disorders of copper homeostasis, we examined three experimental models. First, we overexpressed SLC31A1 in HEK293T and ABC1 cells, which dramatically increased sensitivity to physiological concentrations of copper (Fig. 6E and fig. S8B). Consistent with our findings using copper ionophores in wild-type cells, copper supplementation resulted in overall reduction in proteins involved in mitochondrial respiration (table S4 and fig. S8C), reduced protein lipoylation, reduced the levels of Fe-S cluster proteins, and increased levels of HSP70 (Fig. 6F). Importantly, ferroptosis, necroptosis and apoptosis inhibitors did not prevent copper-induced cell death in SLC31A1 overexpressing cells (Fig. 6G and fig. S8, D to F), whereas copper chelators, FDX1 KO and LIAS KO each partially rescued from copper induced cell-death (Fig. 6, G and H and fig. S8, D to G). In addition, depletion of the natural intracellular copper chaperone glutathione resulted in copper dependent cell death (Fig. 6I), associated with reduced lipoylation and increased DLAT oligomerization (fig. S8, I and J) that was attenuated by FDX1 and LIAS KO, just as was observed with copper ionophore treatment of SCL31A1 wild-type cells (Fig. 6J and fig. S8H).

Lastly, we used a mouse model of Wilson’s disease, whereby Atp7b deletion leads to intracellular copper accumulation and cell death with increasing animal age (37, 38). Comparing the livers of aged Atp7b-deficient (Atp7b−/−) to Atp7b heterozygous (Atp7b−/+) and wild-type (WT) control mice, we observed loss of lipoylated and Fe-S cluster proteins, as well as an increase in Hsp70 abundance (table S5 and Fig. 6K). These findings in mouse models of copper toxicity suggest that copper overload results in the same cellular effects as those induced by copper ionophores. Taken together, our data supports a model whereby excess copper promotes the aggregation of lipoylated proteins and destabilization of Fe-S cluster proteins that results in proteotoxic stress and ultimately cell death (Fig. 6L).

Discussion

Copper is a double-edged sword – it is essential as a co-factor for enzymes across the animal kingdom, and yet even modest intracellular concentrations can be toxic, resulting in cell death (2). Genetic variation in copper homeostasis results in life-threatening disease (39, 40), and both copper ionophores (11, 17, 41, 42) and copper chelators (43–46) have been suggested as anticancer agents. However, the mechanism by which copper overload leads to cell death has been obscure. Here, we have shown that copper toxicity occurs via a mechanism distinct from all other known mechanisms of regulated cell death including apoptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis. We therefore propose that this novel cell death mechanism be termed cuproptosis.

We have shown that copper-induced cell death is mediated by an ancient mechanism: protein lipoylation. Remarkably few mammalian proteins are known to be lipoylated, and these are concentrated in the TCA cycle, where lipoylation is required for enzymatic function (26, 47). Our study explains the relationship between mitochondrial metabolism and the sensitivity to copper mediated cell death – respiring, TCA-cycle active cells have increased levels of lipoylated TCA enzymes (in particular, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex), and the lipoyl moiety serves as a direct copper-binder, resulting in lipoylated protein aggregation, loss of Fe-S cluster-containing proteins, and induction of HSP70, reflective of acute proteotoxic stress. The targets of copper induced toxicity we describe here in human cancer cells (lipoylation and Fe-S cluster proteins) are evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to humans, suggesting that copper-induced cell death might be also utilized by microorganisms where copper ionophores are naturally synthesized and exhibit antimicrobial activity (48, 49).

In the case of genetic disorders of copper homeostasis (Wilson’s and Menke’s disease), copper chelation is an effective form of therapy (50). In cancer, however, the exploitation of copper toxicity has been less successful (42). Copper ionophores, including elesclomol, have been tested in clinical trials, but such testing occurred without the benefit of either a biomarker of the appropriate patient population, or an understanding of the drug’s mechanism of action. A phase 3 combination clinical trial of elesclomol in patients with melanoma showed lack of efficacy in this unselected population, but a post-hoc analysis of patients with low plasma lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels showed evidence of anti-tumor activity (42). Low LDH reflects higher cellular dependency on mitochondrial metabolism (as opposed to glycolysis), consistent with our finding that cells undergoing mitochondrial respiration are particularly sensitive to copper ionophores, and that this sensitivity is explained by their high levels of lipoylated TCA enzymes. Moreover, our observation that the abundance of FDX1 and lipoylated proteins is highly correlated across a diversity of human tumors, and that cell lines with high levels of lipoylated proteins are sensitive to copper induced cell-death, suggests that copper ionophore treatment should be directed toward tumors with such a metabolic profile. Future clinical trials of copper ionophores using a biomarker-driven approach should therefore be considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Markley, H. Adelmann, M. Slabicki, V. Wang and H. Keys for constructive discussion and help with genetic screens. We thank T. Woo for help with immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence studies and A. Muchenditsi for help with the Atp7b mice. We thank C. Lewis (Whitehead metabolomics), W. Salmon (Whitehead imaging) and R. Rodrigues (HMS-TCMP proteomic facility) for the technical help. We thank the Image and Data Analysis Core at Harvard Medical school for coding support.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant 1 R35 CA242457–01 (T.R.G.) and Novo Holdings (T.R.G., P.T.), K08 CA230220 (S.M.C.), T32-GM007748 (S.C.), Research and Recruitment Funding by BCH (B.P. and N.K.) and R01-CA194005, U54-CA225088 and the Ludwig Center at Harvard Medical School (S.S).

Footnotes

Competing interests: S.M.C and T.R.G. receive research funding unrelated to this project from Bayer HealthCare and Calico Life Sciences. T.R.G receives research funding unrelated to this project from Novo Holdings; recently held equity in FORMA Therapeutics; is a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline and Anji Pharmaceuticals and is a founder of Sherlock Biosciences. S.S is a consultant for RareCyte, Inc. P.T and T.R.G. are inventors on the patent application PCT/US21/19871 submitted by the Broad Institute entitled “Method of treating cancer”. J.E. is currently an employee of Kojin Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary materials.

References:

- 1.Kim BE, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ, Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation. Nat Chem Biol 4, 176–185 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge EJ et al. , Connecting copper and cancer: from transition metal signalling to metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutsenko S, Human copper homeostasis: a network of interconnected pathways. Curr Opin Chem Biol 14, 211–217 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O’Halloran TV, Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science 284, 805–808 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsvetkov P et al. , Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Nat Chem Biol 15, 681–689 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasinoff BB, Yadav AA, Patel D, Wu X, The cytotoxicity of the anticancer drug elesclomol is due to oxidative stress indirectly mediated through its complex with Cu(II). J Inorg Biochem 137, 22–30 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tardito S et al. , Copper binding agents acting as copper ionophores lead to caspase inhibition and paraptotic cell death in human cancer cells. J Am Chem Soc 133, 6235–6242 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunsaker EW, Franz KJ, Emerging Opportunities To Manipulate Metal Trafficking for Therapeutic Benefit. Inorg Chem 58, 13528–13545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveri V, Biomedical applications of copper ionophores. Coordin Chem Rev 422, (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corsello SM et al. , Discovering the anticancer potential of non-oncology drugs by systematic viability profiling. Nature Cancer 1, 235–248 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cen D, Brayton D, Shahandeh B, Meyskens FL Jr., Farmer PJ, Disulfiram facilitates intracellular Cu uptake and induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Med Chem 47, 6914–6920 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirshner JR et al. , Elesclomol induces cancer cell apoptosis through oxidative stress. Mol Cancer Ther 7, 2319–2327 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tardito S et al. , Copper-dependent cytotoxicity of 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives correlates with their hydrophobicity and does not require caspase activation. J Med Chem 55, 10448–10459 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagai M et al. , The oncology drug elesclomol selectively transports copper to the mitochondria to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 52, 2142–2150 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimada K et al. , Copper-Binding Small Molecule Induces Oxidative Stress and Cell-Cycle Arrest in Glioblastoma-Patient-Derived Cells. Cell Chem Biol 25, 585–594 e587 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yip NC et al. , Disulfiram modulated ROS-MAPK and NFkappaB pathways and targeted breast cancer cells with cancer stem cell-like properties. Br J Cancer 104, 1564–1574 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H, Dou QP, Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity. Cancer Res 66, 10425–10433 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu N, Huang H, Dou QP, Liu J, Inhibition of 19S proteasome-associated deubiquitinases by metal-containing compounds. Oncoscience 2, 457–466 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skrott Z et al. , Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregase adaptor NPL4. Nature 552, 194–199 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G, The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res 29, 347–364 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carneiro BA, El-Deiry WS, Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17, 395–417 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM, Green DR, Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 127–136 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT, Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 99–109 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon SJ et al. , Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elmore S, Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 35, 495–516 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solmonson A, DeBerardinis RJ, Lipoic acid metabolism and mitochondrial redox regulation. J Biol Chem 293, 7522–7530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birsoy K et al. , An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell 162, 540–551 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeder NL et al. , Zinc pyrithione inhibits yeast growth through copper influx and inactivation of iron-sulfur proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55, 5753–5760 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav AA, Patel D, Wu X, Hasinoff BB, Molecular mechanisms of the biological activity of the anticancer drug elesclomol and its complexes with Cu(II), Ni(II) and Pt(II). J Inorg Biochem 126, 1–6 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowland EA, Snowden CK, Cristea IM, Protein lipoylation: an evolutionarily conserved metabolic regulator of health and disease. Curr Opin Chem Biol 42, 76–85 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni M et al. , Functional Assessment of Lipoyltransferase-1 Deficiency in Cells, Mice, and Humans. Cell Rep 27, 1376–1386 e1376 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smirnova J et al. , Copper(I)-binding properties of de-coppering drugs for the treatment of Wilson disease. alpha-Lipoic acid as a potential anti-copper agent. Sci Rep 8, 1463 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brancaccio D et al. , [4Fe-4S] Cluster Assembly in Mitochondria and Its Impairment by Copper. J Am Chem Soc 139, 719–730 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chillappagari S et al. , Copper stress affects iron homeostasis by destabilizing iron-sulfur cluster formation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 192, 2512–2524 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macomber L, Imlay JA, The iron-sulfur clusters of dehydratases are primary intracellular targets of copper toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 8344–8349 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevitt T, Ohrvik H, Thiele DJ, Charting the travels of copper in eukaryotes from yeast to mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823, 1580–1593 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lutsenko S, Atp7b−/− mice as a model for studies of Wilson’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans 36, 1233–1238 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muchenditsi A et al. , Systemic deletion of Atp7b modifies the hepatocytes’ response to copper overload in the mouse models of Wilson disease. Sci Rep 11, 5659 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandmann O, Weiss KH, Kaler SG, Wilson’s disease and other neurological copper disorders. Lancet Neurol 14, 103–113 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G, Copper homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer’s, prion, and Parkinson’s diseases and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Chem Rev 106, 1995–2044 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Day S et al. , Phase II, randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial of weekly elesclomol plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone for stage IV metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 27, 5452–5458 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Day SJ et al. , Final results of phase III SYMMETRY study: randomized, double-blind trial of elesclomol plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone as treatment for chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31, 1211–1218 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui L et al. , Mitochondrial copper depletion suppresses triple-negative breast cancer in mice. Nat Biotechnol 39, 357–367 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsang T et al. , Copper is an essential regulator of the autophagic kinases ULK1/2 to drive lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Cell Biol 22, 412–424 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis CI et al. , Altered copper homeostasis underlies sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to copper chelation. Metallomics 12, 1995–2008 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brady DC, Crowe MS, Greenberg DN, Counter CM, Copper Chelation Inhibits BRAF(V600E)-Driven Melanomagenesis and Counters Resistance to BRAF(V600E) and MEK1/2 Inhibitors. Cancer Res 77, 6240–6252 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayr JA, Feichtinger RG, Tort F, Ribes A, Sperl W, Lipoic acid biosynthesis defects. J Inherit Metab Dis 37, 553–563 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patteson JB et al. , Biosynthesis of fluopsin C, a copper-containing antibiotic from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 374, 1005–1009 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raffa N et al. , Dual-purpose isocyanides produced by Aspergillus fumigatus contribute to cellular copper sufficiency and exhibit antimicrobial activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggarwal A, Bhatt M, Advances in Treatment of Wilson Disease. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 8, 525 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amici DR et al. , FIREWORKS: a bottom-up approach to integrative coessentiality network analysis. Life Sci Alliance 4, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary materials.