Abstract

NMR spectroscopy can be used to quantify the binding affinity between proteins and low-complexity molecules, termed ‘fragments’; this versatile screening approach allows researchers to assess the druggability of new protein targets. Protein-observed 19F-NMR (PrOF NMR) using 19F-labeled amino acids generates relatively simple spectra that are able to provide dynamic structural information toward understanding protein folding and function. Changes in these spectra upon the addition of fragment molecules can be observed and quantified. This protocol describes the sequence-selective labeling of three proteins (the first bromodomains of Brd4 and BrdT, and the KIX domain of the CREB-binding protein) using commercially available fluorinated aromatic amino acids and fluorinated precursors as example applications of the method developed by our research group. Fragment-screening approaches are discussed, as well as Kd determination, ligand-efficiency calculations and druggability assessment, i.e., the ability to target these proteins using small-molecule ligands. Experiment times on the order of a few minutes and the simplicity of the NMR spectra obtained make this approach well-suited to the investigation of small- to medium-sized proteins, as well as the screening of multiple proteins in the same experiment.

INTRODUCTION

NMR spectroscopy, using either labeled proteins or labeled small molecules, is emerging as a preferred method for screening low-complexity molecules (typically <300 Da with a minimal number of functional groups), termed ‘fragments’ in early-stage ligand discovery campaigns1,2. Fragments typically bind to their protein target with low affinity (mid-micromolar to millimolar dissociation constants). These low-affinity interactions are readily detected using NMR methods3,4. Fragment molecules can be compared with higher-molecular-weight counterparts found in traditional high-throughput screening libraries, via evaluation of their ligand efficiency (LE), which compares binding affinity or activity relative to the number of atoms in the molecules5,6. Highly ligand-efficient compounds can be developed in an atom-economical manner into more potent compounds by fragment linking or growing approaches7,8. Enthusiasm for this approach remains high with the approval of vemurafenib in 2011, discovered through an initial fragment screening campaign, and several more lead molecules that emerged from fragment screens are in late-stage clinical trials9,10.

Fluorine NMR is an attractive approach for fragment screening because the spin-1/2 nucleus 19F is stable, has a natural abundance of 100% and is nearly absent in biological systems. Many fluorinated amino acids and building blocks are commercially available, including aromatic amino acids 3-fluorotyrosine (3FY), 4-fluorophenylalanine (4FF) and 5-fluoroindole, described herein. In many cases, minimal structural and functional perturbation has been observed11–13. 19F chemical shifts are also sensitive to changes in the molecular environment, and therefore 19F is an ideal background-free NMR-active nucleus for studying challenging problems of molecular recognition by biopolymers12,14. In the case of fluorine-labeled proteins, the environmental sensitivity of fluorine nuclei typically results in well-resolved 1D 19F NMR spectra of proteins whose fluorine-labeled side chains are observed at low to mid-micromolar concentrations (e.g., 25–100 μM; ref. 12).

Fragment screening using low-molecular-weight, low-complexity molecules has attracted considerable attention because of the reduction of chemical space compared with that of higher-molecular-weight, functional-group-rich small molecules used in high-throughput screening. As a result, fragment libraries are typically smaller than high-throughput screening libraries1,2,10,15. An analysis by Scanlon and co-workers16 of 20 different fragment libraries developed in the context of academic or industrial research yielded an average library size of 4,543 fragment library members and a median size of 1,280. The use of smaller library sizes is further supported by the hit rates from these fragment screens, in which the researchers detected a binding event averaging 8.2%, as reported by 11 different screening centers. The high hit rates suggest that adequate chemical space is being covered. Fragments identified as hits have been used to develop efficient ligands with favorable physicochemical properties17.

One of the challenges when screening fragment molecules for binding to a specific protein target is the detection and quantification of low-affinity interactions. Achieving this important research goal often forces researchers to use high ligand concentrations. NMR is a technique that is well-suited for working at these high concentrations. With NMR, mixtures of fragment molecules can also be tested simultaneously. In experiments using proteins labeled with NMR-active nuclei, the NMR spectrum of a mixture that results in a large change in chemical shift of the NMR-active nucleus is deconvoluted by obtaining NMR spectra of the protein with individual molecules to find the small molecule that actively binds the protein (thus causing the observed change in chemical shift). One advantage of this fragment mixture approach is that it enables researchers to test a large number of compounds in a shorter period of time than would be needed to test individual compounds one at a time. A second advantage when using a labeled protein (i.e., protein-observed NMR methods) is the added structural information that the protein resonances provide. These specific resonance perturbations can be used to guide molecular designs that are aimed at increasing fragment affinity.

Ligand-observed NMR methods, such as saturation transfer difference or transverse relaxation Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill-based experiments18,19, provide complementary information that can be used in parallel with protein-observed methods. Ligand-observed and PrOF NMR-based methods are tolerant of a variety of experimental conditions. For example, contrary to many 1H NMR-based experiments, NMR spectra of fluorine-labeled small molecules or fluorine-labeled proteins are not affected by the presence of detergents and buffers that are traditionally used20. Advantages associated with the implementation of ligand-observed experiments with respect to protein-observed experiments are the lower protein concentration (0.1–10 μM) needed in many cases—although increasing protein concentration can lead to a better signal21—and the lack of an upper limit in protein size. In addition, with respect to protein-observed experiments, the active ligand can be readily identified from the fragment mixture without deconvolution. However, in saturation transfer difference NMR, false-positive hit rates can be as high as 50% (ref. 16), although the occurrence of such false positives can be partly mitigated by repeating the experiment in the presence of a competitor ligand (if one is known).

We have proposed a PrOF NMR screening method in which we rapidly monitor changes in the chemical shifts of fluorine resonances in 19F-labeled protein side chains induced by the presence of small molecules (Fig. 1). This approach is analogous to that adopted in determining structure–activity relationships by NMR using labeled amides in 1H–15N heteronuclear single-quantum coherence spectroscopy experiments7. The increasing availability of improved instrumentation using 19F-tuned cryoprobes (e.g., the QCI-F cryoprobe from Bruker), speed of PrOF NMR experiments and ease of spectral interpretation have increased the accessibility of these experiments in academic and industrial settings. We recently applied PrOF NMR for fragment screening with the transcription-factor-binding domain KIX22,23. In this study, we analyzed 85 mixtures (comprising a total of 508 small molecules) in 10 h using a total of 20 mg of protein. This method has been used by others, including follow-up screens against the SPRY-domain-containing SOCS box protein 2 (ref. 24) and AMA1 (ref. 25), and it was shown to be more than twice as fast as 1H–15N heteronuclear single-quantum coherence spectroscopy NMR for small proteins23,26. We have also used the bromodomain BrdT, which is described below27. G-protein-coupled receptor agonists and antagonists can also be identified by this method28. 2D PrOF NMR methods have validated binding modes of fluorinated ligands via 19F–19F homonuclear nuclear Overhauser effect experiments with BcL-xL29. As the incorporation of fluorine in drug molecules increases, nuclear Overhauser effect experiments provide an additional structural biology tool for the characterization of ligand-binding modes. Our lab recently demonstrated a simultaneous analysis (i.e., multiplexed) of small-molecule binding using two 15-kDa bromodomains, Brd4 and BPTF27. In this study, 229 small molecules were screened using this approach30. Because a protein and the potential off-target are screened together, this multiplexed experiment is similar to the RAMPED-UP 2D NMR experiments with differently labeled proteins31. These approaches are advantageous for studies in which protein selectivity is important.

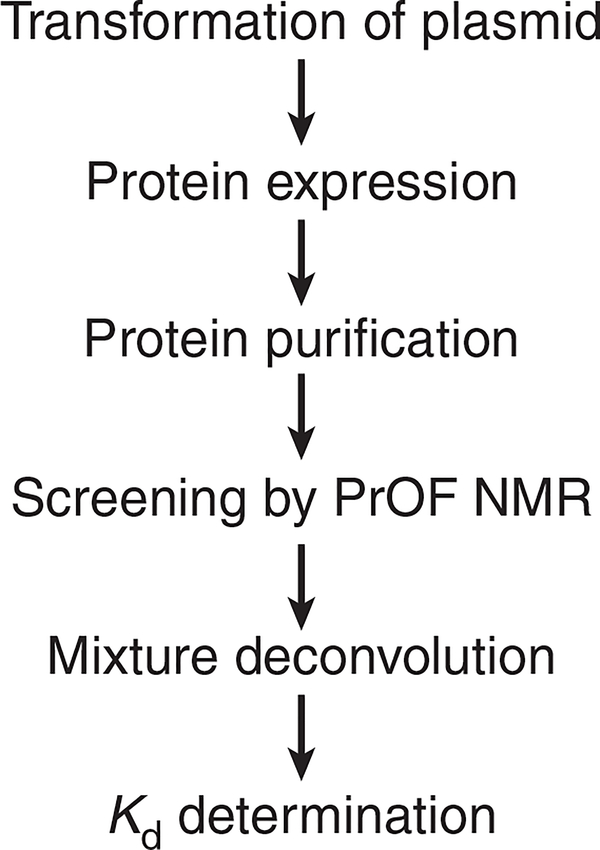

Figure 1 |.

General workflow for using PrOF NMR for fragment screening and ligand characterization.

In 1974, Sykes et al.32 first reported the 19F NMR analysis of an 86-kDa protein, alkaline phosphatase, using 3FY to label the protein. Sequence-selective labeling of recombinant proteins with fluorinated amino acids is now a well-documented methodology that facilitates the general use of the present screening method based on PrOF NMR33,34. In this protocol, using sequence-selective labeling with fluorinated aromatic amino acids, we describe the application of PrOF NMR to the screening of small-molecule libraries for potential protein ligands and the quantification of the micromolar to millimolar dissociation constants from chemical shift perturbation analysis. We demonstrate our ligand-binding screening method with two proteins, the transcription-factor-binding domain of the CREB-binding protein, KIX, and the bromodomain Brd4 (Fig. 2). Application of PrOF NMR with a third protein, the first bromodomain of BrdT, will be subsequently described to highlight several additional important aspects of the PrOF NMR protocol. The sequence-selective incorporation of the three fluorinated aromatic amino acids, 3FY, 4FF and 5-fluorotryptophan (5FW), into recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli using either the auxotrophic bacterial cell lines (e.g., DL39(DE3)) or standard bacterial strains (e.g., BL21(DE3)) will first be detailed, as previously described22,33,34. This section of the PROCEDURE will then be followed by our ligand-discovery procedures.

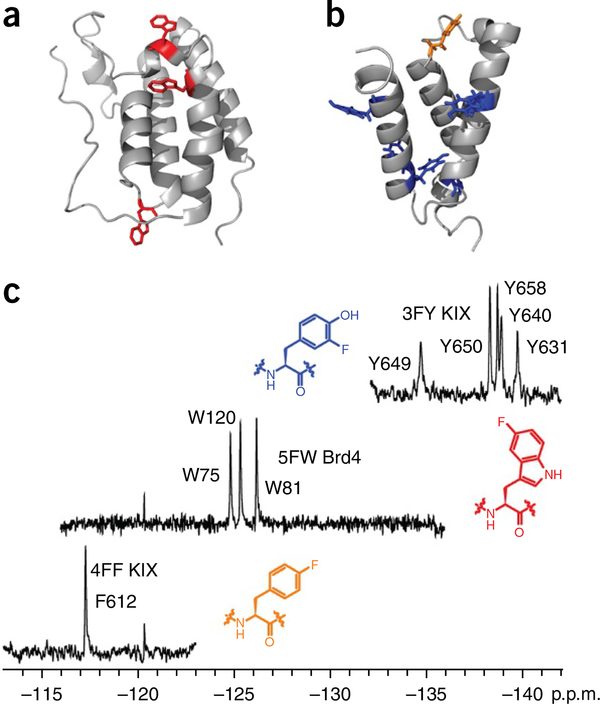

Figure 2 |.

PrOF NMR examples. (a) Crystal structure of Brd4 (PDB 3MXF) with its three tryptophan residues shown in red. (b) Crystal structure of KIX (PDB 1KDX) with its phenylalanine residue shown in orange and its tyrosine residues shown in blue. (c) PrOF NMR spectra for each of these variants, in which the residues highlighted in a and b were replaced by 5FW (Brd4), 3FY (KIX) or 4FF (KIX). In these spectra, the wide chemical shift dispersion of the signals due to the fluorine-labeled, aromatic amino acid analogs are highlighted. The structures of the mentioned fluorinated amino acids are shown next to their corresponding spectra.

Experimental design

Fluorinated protein expression and characterization.

All expressed proteins in the PROCEDURE are characterized for purity and fluorine incorporation via SDS–PAGE and protein mass spectrometry via electrospray ionization. Protein yields vary on the basis of the protein system, fluorinated amino acid and the cell line used. We have achieved yields as high as 70 mg/l for 3FY-labeled KIX and 65 mg/l for 4FF-labeled KIX using auxotrophic DL39(DE3) cells, and obtained up to 62 mg/l 5FW-labeled KIX23 (C.T.G., unpublished data) using non-auxotrophic BL21(DE3) cells with 5-fluoroindole added to the cell culture medium. All expressions led to a high labeling efficiency. We observed even higher yields with our fluorinated bromodomains (84 mg/l for 5FW BPTF and 88 mg/l for 5FW Brd4) (ref. 30). The SDS–PAGE gel in Figure 3a shows four KIX protein samples that are unlabeled, 3FY-labeled, 4FF-labeled or 5FW-labeled.

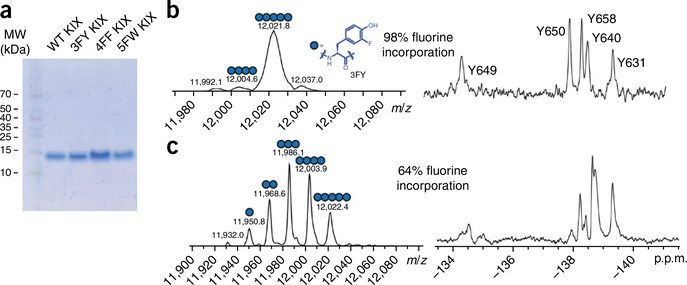

Figure 3 |.

Characterization of fluorinated proteins expressed according to the present Protocol. (a) SDS–PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue showing wild-type and three fluorinated variants of KIX. (b) Deconvoluted electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectrum (left) and 19FNMR spectrum (right) of 3FY-labeled KIX with 98% fluorine incorporation. The dominant population present is the fully fluorinated variant. See Box 3 for directions for how to calculate the fluorine incorporation percentage. (c) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectrum (left) and 19FNMR spectrum (right) of 3FY-labeled KIX with 64% fluorine incorporation. Figure 3b adapted from ref. 23, Wiley-VCH Verlag.

Mass spectrometry is used to assess fluorine incorporation into the protein. For the mass spectrogram of 3FY-labeled KIX, the dominant mass of 12,021.8 Da corresponds to the incorporation of a fully labeled protein (five 3FY residues). The minor mass of 12,004.6 Da corresponds to four of the five tyrosine residues being replaced with 3FY. These major and minor populations lead to a 98% labeled protein (Fig. 3b). Low levels of incorporation can result in a heterogeneous protein sample, which can complicate the analysis of 19F NMR spectra (see Troubleshooting Table). A 19F NMR spectrum of 3FY-labeled protein that is only 64% labeled is reported for comparison (Fig. 3c). The resulting spectrum is a statistical mixture of multiply labeled proteins, and it can result in additional (e.g., Y650) or broadened resonances. In some instances, if needed, the concentration of fluorinated amino acids can be increased in the culture medium with respect to those recommended in the PROCEDURE, to increase the extent of protein labeling. Low levels of labeling can also be attributed to residual unlabeled amino acid from the initial expression conditions, an inconvenience that can be reduced with careful washings of bacterial pellets and preincubations with fluorinated amino acids.

TABLE 1 |.

Troubleshooting table.

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Low protein yield relative to protein expression yields using natural amino acids | Cell line may not be robust for protein expression Poor compatibility with tRNA synthetase Toxic levels of fluorinated amino acids |

Change cell lines. Auxotrophic cell lines tend to provide lower yields than nonauxotrophic cell lines Use glyphosate to induce auxotrophy in a standard cell line (e.g., BL21(DE3)) (refs. 53,54) Cotransform with a plasmid to increase tRNA synthetase levels47 Use cell-free methods55 Reduce the concentration of fluorinated amino acids |

| 13 | Extremely broad NMR resonances | Magnetic field strength is too high or side chain dynamics are too slow, which can cause significant broadening of resonances because of CSA Protein is too large |

We find ideal field strengths to be 500 –600 MHz. The signal sensitivity and resolution benefits of higher-field-strength magnets can be cancelled out by CSA and shortened T2 relaxation Use alternative labeling strategies that utilize fluorinated amino acids with more rapidly rotating fluorine groups (e.g., trifluoromethyl)43,46 |

| Unknown fluorine resonances in the NMR spectrum | A fluorinated impurity is present | Fluorinated impurities in your sample may be removed by a buffer exchange Alter the spectral window. Polymer background is most pronounced beyond −140 p.p.m. Increase the prescan delay |

|

| 14 | Fluorine referencing problems | Fluorine reference is sensitive to solution conditions or the presence of small-molecule ligands | Alternative fluorine references (e.g., trifluoroethanol) can be used Alternative NMR pulses (e.g., ERETIC) can be used56,57 |

| 19 | Protein signal overwhelmed by additional fluorine resonances | A fluorine-containing molecule is present in the mixture | Deconvolute the mixture to ascertain whether other ligands are binding Test fluorinated molecules separately and at lower concentrations Use a different fluorinated-amino-acid–labeled protein |

| 23 | No deconvolved compounds exhibit the same change in chemical shift as the mixture | Small molecules may have additive effects on the protein signals | Select the compound that contributes the most toward the change Prioritize other mixtures with more distinct effects from the compounds |

| 29 | Data do not fit well for Kd value determination (poor R2 value) | Saturation point not yet reached, making it difficult to accurately determine a Kd value using the equation Nonspecific or multisite binding |

Increase the concentration of the ligand to approach saturation Deprioritize this compound Change nonlinear regression analysis to include multiple binding sites |

| Box 3 | Poor label incorporation (<90%) | Nonoptimized recovery time Not enough fluorinated amino acid or amino acid precursor |

Experiment with longer recovery times after the media swap Increase the amount of the fluorinated amino acid |

| Box 4, step 2 | Site-directed mutagenesis failure | The specific amino acid may be necessary for the protein to adopt its proper secondary structure, or it affects more than one resonance | Site-selective labeling of 4FF and 3FY can be used to label individual residue positions rather than globally changing all of a given amino acid58,59 Kitevski-LeBlanc et al.60 describe a multidimensional NMR method to assign resonances Paramagnetic metals (e.g., Gd3+) can be used to broaden surface-exposed residues |

Fluorine is not an element that is naturally found in proteins. Therefore, before the implementation of the screening protocol, the structural and functional perturbation caused by the introduction of the fluorine-based label into the protein must be carried out. We have characterized our proteins by a variety of methods, using X-ray crystallography, circular dichroism and thermal stability measurements to assess structure22,27. When a ligand was known beforehand, we have also used isothermal titration calorimetry or fluorescence anisotropy ligand-binding experiments to compare the affinity of the known ligand with those of the fluorinated and nonfluorinated proteins. Supplementary Figure 1 shows an example of a direct binding experiment with a fluorescently labeled bromodomain ligand, BI-BODIPY, with 5FW-labeled Brd4 and unlabeled Brd4 yielding dissociation constants of 110 and 55 nM, respectively. In our experience, we have considered a two-to threefold change in binding affinity between fluorine-labeled and unlabeled protein to be acceptable for continuing on with the labeled protein in a ligand screen. We recommend trying alternative labeling approaches or using different amino acids (e.g., 6-fluoro versus 5-fluorotryptophan) if larger perturbations are observed.

PrOF NMR.

PrOF NMR spectra of small- to medium-sized fluorinated proteins typically reveal well-resolved resonances for each labeled aromatic amino acid, but not in all cases. The different aromatic residues are seen in close but distinct chemical shift regions (Fig. 2). A well-dispersed NMR spectrum is an additional confirmation of a well-folded protein. Protein resonances tend to be broad. Fluorine resonances from small-molecule impurities or peptides resulting from proteolytic degradation appear as sharp signals in 19F NMR spectra, and their presence can help assess the stability and purity of the protein. A resonance due to a small-molecule impurity can be seen in Figure 2c at −120 p.p.m. In some cases, protein precipitation or aggregation leads to loss of signal for all of the protein resonances, which can be useful for the identification of false positives in a ligand screen.

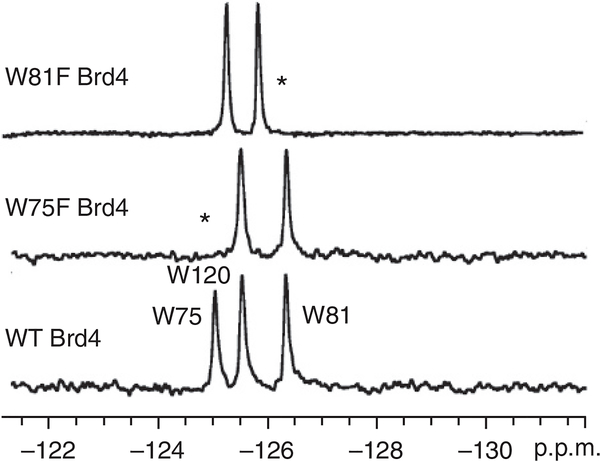

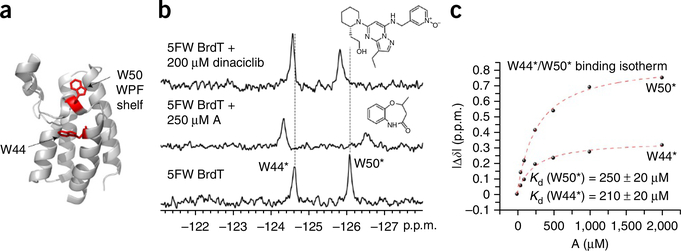

Resonances can be assigned by recording the spectrum of a fluorinated protein for which one residue has been mutated to an amino acid that can no longer be fluorine-labeled in the expression conditions because the corresponding fluorinated analog is not present in the culture medium (e.g., Trp to Phe). As an example, three relevant spectra are reported in Figure 4. In this case, the bromodomain Brd4 is labeled with three 5FW residues, which results in three well-resolved resonances. The disappearance of the resonances at −124.9 and −126.2 p.p.m. upon directed mutation of specific tryptophan residues leads to the assignment of these resonances to fluorine-labeled W75 and fluorine-labeled W81 (Fig. 4, middle and top spectra). However, because of the sensitivity of fluorine to subtle changes in environment, additional chemical shift changes can occur, which, in some cases, preclude assignment. In this case, the addition of a known ligand can help identify side-chain resonances in the ligand-binding site. For example, the first bromodomain of BrdT has two tryptophan resonances, and W50 is known to be located in the ‘WPF shelf’ at the histone-binding site. Addition of the known BrdT ligand dinaciclib (IC50 = 61 μM) was used to help assign the resonance due to the fluorine-labeled W50. The broadening and the 0.25-p.p.m. chemical shift perturbation of the upfield resonance is consistent with X-ray crystallography data on the co-crystal structures, which show a conformational change of W50 upon binding35 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Chemical shift perturbation upon the addition of a known ligand can also serve as a useful confirmation of the functional integrity of a fluorine-labeled protein22,27. Alternative strategies for assignments are described in the Troubleshooting Table. Fragment screening can be carried out once a well-folded, highly labeled protein has been obtained, although the protein NMR spectrum does not necessarily need to be assigned first.

Figure 4 |.

Using site-directed mutagenesis to assign PrOF resonances (see directions in Box 4). Asterisks denote the resonance that has disappeared after mutation of the relevant (fluorine-labeled) tryptophan into a phenylalanine, which allows assignment of that resonance to the specific mutated amino acid residue. Figure 4 adapted (with minor stylistic changes) with permission from ref. 27, American Chemical Society (http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/cb5007344 )

Figure 5 |.

Results from experiments involving small-molecule ligands for BrdT. (a) Crystal structure of BrdT (PDB 4FLP) showing the two tryptophans in red. Please note that W50 is located in the protein’s WPF shelf. (b) PrOF NMR spectra of 5FW-BrdT by itself (bottom spectrum) and in the presence of two different small molecules, fragment A, middle spectrum (see also the structure of the compound above the spectrum, to the right-hand side), and dinaciclib, top spectrum (see also the structure of the compound above the spectrum, to the right-hand side). (c) Binding isotherms for fragment A generated by plotting the change in chemical shift for both 5FW resonances as a function of ligand concentration, which yield comparable Kd values. *Resonance assignments that were inferred from small-molecule binding.

Dissociation constant and LE determination.

The affinity of fragment hits from the screen can be readily assessed for protein ligands with up to millimolar dissociation constants via ligand titration and subsequent nonlinear regression of the binding isotherm produced by monitoring changes in chemical shift. This chemical shift perturbation experiment is valid when the molecules are in fast exchange, as indicated by the presence of a single resonance signal whose chemical shift is the weighted average of the bound and unbound states. The speed of the experiment, the low concentration of proteins needed for it and the possible automation of the procedure enable the rapid testing of multiple small molecules.

In the present approach, separate samples are set up with varying concentrations of the small molecule. The dissociation constant (Kd) is obtained by fitting the obtained data to a nonlinear regression curve using equation 1, accounting for receptor depletion26. Analysis of the affinity of the small molecule and location of perturbed resonances can then be used to assess valuable structure-activity relationships between molecules and differential binding to various surfaces on a protein.

| (1) |

In equation 1, S is the observed change in chemical shift, D is the maximum change in chemical shift, Kd is the dissociation constant of the ligand, L is the ligand concentration and P is the protein concentration. The maximal shift, D, can be obtained through nonlinear regression, or experimentally, when further addition of a small molecule no longer perturbs the resonance. In addition, as a means of prioritizing ligands for future development, these affinity data can be used to calculate the LE using equation 2, which enables this efficiency to be calculated on the basis of the binding affinity of the ligand and the contribution of each nonhydrogen atom to the free energy of the interaction.

| (2) |

Although this scenario is not commonly encountered in fragment screens, ligands with high affinity may have a sufficiently long residence time on the protein that the bound and unbound states are partially resolved (intermediate exchange) or fully resolved (slow exchange) during the 19F NMR experiment. In these instances, titration will not result in a binding isotherm. Intermediate exchange kinetics results when interchanging species at equal populations (e.g., bound and unbound states) lead to coalescence into a single resonance36,37.

| (3) |

In equation 3, the frequency difference in Hertz between the two resonances (Δν)—bound versus unbound state—establishes a relationship that enables researchers to estimate the residence time of the ligand on the protein based on the rate of dissociation (k−1). In the case in which the rate of exchange approaches the coalescence point (τ ≈ Δν) during a protein-ligand titration, the resonances will coalesce so that the signal will initially broaden, but it will become sharp again, in a dose-dependent manner, as the chemical shift is perturbed by the titration process. With slow exchange kinetics (likely to be associated with a low dissociation constant), both resonances can be well resolved, and, during a protein–ligand titration, one resonance will gradually disappear while another will grow from the baseline in a dose-dependent manner.

Experimental considerations and assay limitations.

The additional rotational freedom in protein side chains versus the amide backbone can lead to smaller linewidths relative to amide resonances. One consideration that should be made before using 19F-labeled proteins for NMR is the sensitivity of the fluorine nucleus to substantial chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) relaxation effects. CSA relaxation leads to resonance broadening, which is enhanced by protein dynamics, including long rotational correlation times of amino acids found in large proteins38. CSA relaxation is proportional to the square of the magnetic field strength. From a practical standpoint, we carry out NMR experiments at 471–564 MHz using fluorinated aromatic amino acids. 5FW experiences a lower degree of CSA relative to other fluorinated tryptophan analogs, and in some cases it has been used with proteins as large as 65 kDa (ref. 39). As an alternative to 5FW, fluorine-labeled cysteine or methionine derivatives with substantially reduced CSA effects are recommended for proteins larger than 40 kDa, as has been demonstrated in experiments with G-protein-coupled receptors and amyloid-β aggregates28,40–42. Site-selective fluorine labeling with trifluoromethylphenylalanine has also been used for large proteins43,44. For small- to medium-sized proteins, PrOF NMR is applicable using a variety of fluorine-labeled amino acids, including singly fluorinated (tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan, Fig. 2) and more heavily fluorinated amino acids such as di- and trifluoromethylmethionine45,46, and tri- and hexafluoroleucine47–49. We propose using singly fluorinated aromatic amino acids, as this approach reduces spectral complexity with respect to using amino acids with multiple nonequivalent fluorines. Furthermore, it allows high levels of enrichment in labeled amino acids at protein–protein interaction interfaces50 while minimizing the perturbing effect of fluorine substitution. Nevertheless, we reiterate that protein structural and functional perturbation caused by fluorine substitution should always be assessed by conducting preliminary complementary structural and functional biophysical experiments.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

▲ CRITICAL Unless noted, reagents of comparable quality from alternative suppliers can be substituted.

Protein expression components

Fragment mixtures ▲ CRITICAL These are prepared according to guidelines outlined in Box 1. Sources of fragment libraries include Maybridge and Chembridge.

Plasmid encoding your protein of choice that also encodes for resistance to an antibiotic of choice ▲ CRITICAL For nickel affinity purification, ensure that the plasmid includes a His tag, described in Step 9 and in the Supplementary Method.

Plasmid vectors pRARE (Novagen), pRSETB-HIS6KIX (Invitrogen), and pNIC28-BSA4 (Addgene; used in the Supplementary Method)

Competent DL39(DE3)* (DL39, CGSC) or BL21(DE3) (Novagen) E. coli cell lines A CRITICAL The choice of cell lines must be made carefully. Auxotrophic cell lines (e.g., DL39(DE3)) are necessary for labeling with 3FY or 4FF. For tryptophan labeling, 5-fluoroindole with non-auxotrophic cell lines (e.g., BL21(DE3)) is recommended for higher protein yields.

Box 1 |. Preparation of fragment mixture ● TIMING variable.

-

Obtain or prepare concentrated ligand stock solutions (200 mM) in a given solvent (e.g., DMSO or ethylene glycol) for the fragments of interest. Please note that solvent choice will depend on ligand solubility and solvent effects on the protein of interest.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The maximum volume of the solvent that will be tolerated without significantly perturbing the chemical shifts or the shapes of the 19F NMR resonances must be determined in order to accurately assess ligand binding. We recommend that the final solution be composed of 1–5% organic solvent.

Determine the desired number of fragments for each screening mixture. Common screening mixtures include 5–10 fragment compounds. Fragment mixtures of five of six compounds will reduce the number of compounds needed in the deconvolution step, if a high hit rate is anticipated.

Decide the concentration at which each fragment will be screened. Fragment mixture concentrations will depend on the expected Kd values for ligands in the mixture. Because of the low-affinity nature of fragment compounds, mid-micromolar to low millimolar Kd values for individual fragments are common. For example, using six fragments per mixture, starting from 200 mM DMSO stock solutions, yields mixtures containing ligands at 33.3 mM with a final ligand concentration of 833 μM at 2.5% (vol/vol) DMSO in the NMR sample. Screening ligands at lower concentrations will yield smaller changes in chemical shift, potentially resulting in more false negatives. If the ligandability and/or druggability of the protein is unknown, a pilot screen with ligands at various concentrations can be performed.

Compile the fragment mixtures, taking into account the number of acidic, basic and neutral compounds present to avoid significant pH-dependent effects.

QiAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (250) (Qiagen, cat. no. 27106)

Lennox L Broth (LB) (powdered or granulated, RPI, cat. no. L24066)

Lennox L Agar (powdered or granulated, RPI, cat. no. L24030)

Super optimal broth with catabolite repression (SOC) (SOB with added glucose; RPI, cat. no. S25000)

ampicillin (RPI, cat. no. A40040)

Kanamycin (RPI, cat. no. K22000)

Chloramphenicol (RPI, cat. no. C61000)

Natural amino acids (see Box 2, Step 1)

Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; RPI, cat. no. I56000)

Imidazole (RPI, cat. no. I52000)

Sodium phosphate, monobasic, monohydrate (RPI, cat. no. S23120)

Sodium phosphate, dibasic, heptahydrate (Sigma, cat. no. S9390)

Sodium chloride (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. S2713)

HEPES (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. BP310)

Tris (Acros, cat. no. 167620010)

3-Fluoro-DL-tyrosine (Alfa Aesar, cat. no. L01479)

4-Fluoro-DL-phenylalanine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F5251)

5-Fluoro-indole (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. F9108)

Ultrapure water, 18.2 MΩ · cm

Box 2 |. Preparation of the defined medium ● TIMING 3–4 h.

To simplify the preparation if the protocol is going to be performed multiple times, a sterile-filtered stock solution consisting of the reagents listed in Step 2 (CaCl2 through biotin) may be prepared and stored at 4 °C for several months; an appropriate volume of stock solution would then be added to the defined medium instead of adding the components individually.

-

1

Combine the amino acids, salts and nucleotide bases listed below in a total volume of 1 l of deionized water, omitting the amino acid that will be labeled, and autoclave the solution. Natural amino acids were all purchased from RPI.

| Component | Supplier (cat. no.) | Amount for 1-l expression |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine | RPI (A20060) | 500 mg |

| Arginine | RPI (A50010) | 400 mg |

| Asparagine | RPI (A50030) | 400 mg |

| Aspartic acid | RPI (A50060) | 400 mg |

| Cysteine HCl | RPI (C81020) | 50 mg |

| Glutamine | RPI (G36040) | 400 mg |

| Glutamic acid | RPI (G36020) | 650 mg |

| Glycine | RPI (G36050) | 550 mg |

| Histidine | RPI (H75040) | 100 mg |

| Isoleucine | RPI (I54020) | 230 mg |

| Leucine | RPI (L22000) | 230 mg |

| Lysine HCl | RPI (L37040) | 420 mg |

| Methionine | RPI (M22060) | 250 mg |

| Phenylalanine | RPI (P20260) | 130 mg |

| Proline | RPI (P50200) | 100 mg |

| Serine | RPI (S22020) | 2.1 g |

| Threonine | RPI (T21060) | 230 mg |

| Tyrosine | RPI (T68500) | 170 mg |

| Valine | RPI (V42020) | 230 mg |

| Sodium acetate | Macron (7372) | 1.5 g |

| Succinic acid | Sigma-Aldrich (S3674) | 1.5 g |

| Ammonium chloride | Fisher Scientific (A661) | 500 mg |

| Sodium hydroxide | Alfa Aesar (A16037) | 850 mg |

| Potassium phosphate (dibasic) | RPI (P41300) | 10.5 g |

| Adenine | RPI (A11500) | 500 mg |

| Guanosine | Alfa Aesar (A11328) | 650 mg |

| Thymine | TCI (T0234) | 200 mg |

| Uracil | RPI (U32000) | 500 mg |

| Cytosine | Alfa Aesar (A14731) | 200 mg |

■ PAUSE POINT If the defined medium is not going to be used right away, do not continue media preparation beyond this step. Medium with just the amino acids and salts with no carbon source (glucose) or vitamins can be stored covered at room temperature for several months.

-

2

Once the solution is sterilized, add the components sequentially, adding MgSO4 last.

| Component | Supplier (cat. no.) | Amount for 1-l expression. |

| 40% (wt/vol) Glucose solution | RPI (G32030) | 50 ml |

| 0.01 M FeCl3 | Sigma-Aldrich (157740) | 1 ml |

| Vitamin solution | ||

| Component | Supplier (cat. no.) | Amount for 1-liter expression |

| Tryptophan | RPI (T60080) | 50 mg |

| CaCl2 dihydrate | Sigma-Aldrich (C3306) | 2 mg |

| ZnSO4 heptahydrate | Sigma-Aldrich (Z4750) | 2 mg |

| MnSO4 monohydrate | Sigma-Aldrich (M7634) | 2 mg |

| Thiamine | RPI (T21020) | 50 mg |

| Niacin | Sigma-Aldrich (72340) | 50 mg |

| Biotin | RPI (B40040) | 1 mg |

| 1 M MgSO4 | Sigma-Aldrich (M7506) | 4 ml |

-

3

Adjust the pH to 7.2 using HCL or NaOH. The medium can be stored at room temperature for a few weeks, although it is recommended that the glucose and vitamin solutions not be added until immediately before use.

-

4

Add the necessary fluorinated amino acid(s) or amino acid precursor for appropriate fluorine labeling.

| Fluorine label | Fluorinated substitution | Amount for 1-l expression | Final concentration in medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3FY | 3-fluoro-DL-tyrosine | 80 mg | 400 μM |

| 4FF | 4-fluoro-DL-phenylalaninea | 29 mg | 160 μM |

| 5FW | 5-fluoroindole | 60 mg | 444 μM |

Addition of 5 μM phenylalanine to the defined medium when using 4-fluoro-DL-phenylalanine has led to increased protein yield but minimal effects on fluorinated amino acid incorporation.

Protein purification components

Lysozyme (Gold Biotech, cat. no. L040)

β-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M6250)

PMSF (RPI, cat. no. P20270)

NMR components

Dimethylsulfoxide (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. D128)

Ethylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 102466)

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. T6508)

Deuterium oxide (Cambridge Isotope Labs, cat. no. DLM-6)

Protein characterization: SDS–PAGE components:

Formic acid (Sigma, cat. no. 56302)

Acetonitrile (J.T. Baker, cat. no. 9853)

40% (wt/vol) acrylamide and bis-acrylamide solution, 37.5:1 (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 1610148)

Ammonium persulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 248614)

Bis-Tris (RPI, cat. no. B75000)

Tetramethylethylenediamine (RPI, cat. no. T18000)

Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 161–0400)

EQUIPMENT

Refrigerated incubator shaker

UV-visible spectrophotometer (e.g., Varian Cary 50 Bio UV/Vis spectrophotometer)

High-speed centrifuge

Sonicator (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. FB505) with 1/8-inch microtip (cat. no. FB 4418)

FPLC (GE Áktapurifier)

HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, cat. no. 17–5087-01)

50-ml Superloop (GE Healthcare, cat. no. 18–1113-82)

Ni-NTA agarose beads (Life Technologies, cat. no. R901–01)

-

NMR spectrometer (recommended 19F signal-to-noise ratio > 550:1)

▲ CRITICAL The NMR probe must be able to tune to the 19F nucleus.

For optimal PrOF NMR experiments, a cryoprobe (e.g., Bruker TCI-Prodigy) should be used for increased signal-to-noise ratio.

19F tuned NMR probe (e.g., TCI-Prodigy cryoprobe, Bruker)

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometer ▲ CRITICAL The mass spectrometer must be capable of resolving proteins to 2–3 a.m.u. for accurate protein characterization, as fluorinated proteins will differ by 18 a.m.u. per incorporated fluorine.

SDS–PAGE gel apparatus and power supply (for use in protein characterization)

NMR tubes

Microcentrifuge tube

15-ml Falcon tubes

50-ml Falcon tubes

Protein concentrators (Millipore Centricon, cat. nos. UFC900324 and UFC800324)

Software

NMR processing software (e.g., TopSpin, MNova)

Nonlinear regression software (e.g., OriginPro, GraphPad)

REAGENT SETUP

LB medium or LB agar

Autoclave the medium before use.

Defined medium recipe

Prepare this medium as described in Box 2.

Lysis buffer

Combine 50 mM phosphate with 300 mM NaCl; adjust pH to 7.4.

▲ CRITICAL All buffers should be filtered and stored at room temperature (22–27 °C).

Wash buffer

Dilute phosphate, NaCl and imidiazole to final concentrations of 50, 100 and 30 mM, respectively, and adjust pH to 7.2.

Elution buffer

Dilute phosphate, NaCl and imidazole to final concentrations of 50, 100 and 400 mM, respectively, and adjust pH to 7.2.

NMR buffer for Brd4

Dilute Tris and NaCl to final concentrations of 50 and 100 mM, respectively, and adjust pH to 7.4.

NMR buffer for KIX

Dilute HEPES and NaCl to final concentrations of 50 and 100 mM, respectively, and adjust pH to 7.2.

EQUIPMENT SETUP

Sonicator program

Sonication time = 4 min at 30% amplitude (this entails 8 × 30-s pulses with 60-s rest times between pulses). Total elapsed time is 12 min.

Ni affinity gradient elution method

Set up the FPLC method that will be used in Step 9. In our laboratory, we use a GE Aktapurifier with a column packed with Ni-NTA Agarose for affinity purification. The four steps are as follows: wash the nickel column with 15 column volumes of wash buffer. Perform a gradient elution across 20 column volumes, ramping from 0 to 100% elution buffer. Wash the column with 5 column volumes of 100% elution buffer. Return it to a 0% elution buffer by applying the reverse gradient in 5 column volumes. UV absorbance should be monitored at 280 nm. Total time (at 1 ml/min flow rate) is 4 h.

Buffer exchange method

Set up the FPLC method that will be used in Step 10. In our laboratory, we use a GE Äktapurifier with a GE HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (17–5087-01). Equilibrate the column with 0.5–1 column volume of buffer before loading the sample. Elute the column with 1 column volume of buffer, and monitor the UV absorbance at 280 nm. Total time (at 2 ml/min flow rate) is 40 min.

PROCEDURE

Bacterial transformation ● TIMING 1 d

-

1|

Prepare bacterial colonies transformed with the plasmid for the protein of interest using standard transformation and inoculation methods. A detailed sample protocol is provided in the Supplementary Method.

▲ CRITICAL STEP As noted in the materials section, the choice of cell lines must be made carefully. Auxotrophic cell lines (e.g., DL39(DE3)) are necessary for labeling with 3FY or 4FF. For tryptophan labeling, 5-fluoroindole with nonauxotrophic cell lines (e.g., BL21(DE3)) is recommended for higher protein yields.

■ PAUSE POINT Culture plates with transformed bacteria may be stored at 4 °C for up to a month.

Fluorinated protein expression and purification ● TIMING 2 d

▲ CRITICAL Maintain sterile conditions while working with media. Standard protein expression methods can be used; these steps are those that are used routinely in our laboratory, and they provide information about when in the process the fluorinated amino acids should be added.

-

2|

Inoculate primary and secondary cultures using standard E. coli expression methods. Detailed steps of a sample protocol are provided in the Supplementary Method.

-

3|

Using a spectrophotometer, determine the optical dispersion at 600 nm (OD600). Remove the culture from the shaker when the OD600 is between 0.6 and 0.8. Please note that this value may vary based on the cuvette distance from the detector in the spectrophotometer.

-

4|

Centrifuge the culture for 20 min at 6,000g at 4 °C.

-

5|

Decant the LB medium and resuspend the pellet in an equivalent amount of the defined medium containing the desired fluorinated amino acid or amino acid precursor (see Reagent Setup section) and appropriate antibiotic.

-

6|

Shake the solution prepared in the previous step at 37 °C and 250 r.p.m. for 90 min as a recovery time for the bacteria, and then decrease the temperature to 20 °C to cool the medium. Continue to shake the medium for an additional 30 min to allow the solution to equilibrate. Please note that the most suitable temperature and recovery time will vary for each protein. Our lab has generally found the above conditions to work well, although there are cases in which a shorter recovery time has produced better results.

-

7|

Induce protein expression by adding IPTG to the solution to a final 1 mM concentration. Continue to shake the culture at 20 °C and 250 r.p.m. for 16–20 h. Please note that the most suitable IPTG concentration and induction time will vary for each protein.

-

8|

Centrifuge the cell culture at 6,000g at 4 °C for 20 min. For ease of purification, we recommend centrifuging cultures in 500-ml or smaller aliquots. Decant the supernatant medium and store the cell pellet at −20 or −80 °C.

■ PAUSE POINT The cell pellet may be stored at −20 or −80 °C for months.

-

9|

Purify and characterize overexpressed protein. Sample purification methods are described in the Supplementary Method, and mass spectrometry characterization is described in Box 3. SDS-PAGE characterization can be performed at this step to evaluate the presence of the desired protein. However, because of the low-resolution nature of SDS–PAGE characterization, it will not be able to quantify fluorine incorporation or distinguish between fluorinated variants (Fig. 3a).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

10|

Buffer-exchange the protein into the desired buffer. In our lab, we use a HiPrep desalting column, but other methods work as well (Nap-5 columns, PD-10 columns and dialysis are all viable options). For PrOF NMR, it is best to avoid buffers with high concentrations of high-mobility salts because of their impact on NMR signal sensitivity. When possible, the lower-mobility salts (e.g., Tris, HEPES) are preferred.

■ PAUSE POINT The purified protein can be stored at 4 °C or flash-frozen and stored at −20 °C for several months. For long-term storage, we recommend flash-freezing and storing at −20 °C. Exact storage conditions may vary from one protein to another.

Box 3 |. Fluorine incorporation characterization ● TIMING 30 min to 1 h.

Concentrate the protein to at least a low micromolar concentration. In our lab, we use centrifugal protein concentrators with either a 3 or 5k MW cutoff. The exact membrane cutoff needed will depend on the size of the protein of interest.

On an ESI mass spectrometer equipped with a liquid chromatography system, use 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid in water and acetonitrile as solvents and a C18 column for separation. Run a gradient elution, ramping from 8% acetonitrile to 80% acetonitrile.

Select the protein peak on the chromatogram and deconvolute the corresponding mass spectrum.

Integrate the peaks corresponding to the protein of interest and its fluorinated variants.

- Use the following formula to calculate the percentage of fluorine incorporation.

Where n corresponds to the number of incorporated fluorinated residues.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

PrOF NMR ● TIMING 5 min to 1 h

-

11|

Concentrate the protein solution to 40–50 μM, as done in Step 1 of Box 3.

-

12|

To a microcentrifuge tube, add 2 μl of 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA, 25 μl of D2O and 473 μl of just-prepared protein solution. Mix well and transfer the solution to a 5-mm NMR tube.

-

13|

Acquire two fluorine NMR spectra. Focus the first experiment on the TFA reference peak, which can be obtained within several scans, and focus the second experiment on the protein. We find that a spectral width of 10–20 p.p.m. is sufficient with an offset (O1P/tof) of −76.5 p.p.m. for the TFA, −136 p.p.m. for 3FY-labeled proteins, −125 p.p.m. for 5FW-labeled proteins or −117 p.p.m. for 4FF-labeled proteins. Experiment time and number of scans required will be dependent on the availability of a cryoprobe versus a room-temperature probe, as well as the protein. On a 500-MHz NMR with a Prodigy inverse cryoprobe (19F S:N 2,100:1), 400 scans are sufficient for the proteins KIX and bromodomain Brd4, which would lead to a 4- to 5-min experiment.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

14|

Process the data by setting the TFA reference peak to −76.5 p.p.m. and applying the same correction factor to the second experiment. Resonance assignments can be performed as described in Box 4.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Box 4 |. (Optional) Assigning PrOF resonances ● TIMING ~3 weeks.

PrOF NMR screening and binding experiments can be performed even if resonances are not assigned. The assignments can provide additional structural information but are not necessary to evaluate small-molecule binding.

Perform site-directed mutagenesis to mutate each amino acid of interest to an alternative amino acid chosen such that it will have very little effect on the protein structure (e.g., Y > F).

-

Obtain PrOF NMR spectra of each mutant (Steps 11–14 of the PROCEDURE). The resonance that has disappeared corresponds to the mutated amino acid residue.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Fragment screening via PrOF NMR ● TIMING variable

-

15|

Prepare a blank sample (Step 10) with the addition of the selected amount of the organic solvent for the fragment mixtures (no ligand or ligand mixtures), maintaining a total sample volume of 500 μl (e.g., 2 μl of 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA, 25 μJ. of D2O, 468 μJ. of protein solution and 5 μl of DMSO).

▲ CRITICAL STEP This blank sample must be identical to the screening samples in regard to the protein concentration and amount of solvents used. The only difference should be that the blank contains organic solvent (with no ligands), whereas the screening samples will contain the same amount of organic solvent (with the ligand mixtures).

-

16|

Prepare the fragment mixture NMR samples in a similar manner to that outlined in Step 15, with the ligand mixture in place of just the organic solvent.

-

17|

Acquire and process PrOF NMR spectra for each mixture (Steps 13 and 14).

-

18|

Record the chemical shift of each fluorine resonance, and calculate the change in chemical shift for each resonance relative to the ‘blank’ spectrum.

-

19|

Using the results obtained in the library screen, identify promising mixtures by statistically analyzing the changes in chemical shifts for each resonance from each mixture, and select the mixtures that yield a change in chemical shift between one and two standard deviations above the average change in chemical shifts from all experiments obtained from the library screen.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Deconvolution of fragment mixtures ● TIMING variable

-

20|

Identify the compounds comprising the mixtures that yielded changes in chemical shift >1–2 standard deviations above the mean.

-

21|

Prepare NMR samples with each of these compounds separately, maintaining equivalent ligand concentrations.

-

22|

Collect the PrOF NMR spectra for each new sample (Step 13).

-

23|

Process and analyze the data as before, calculating the changes in chemical shift to identify the ligand or ligands that bind to the protein target (Steps 14 and 19).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Kd determination of fragment compounds ● TIMING variable

-

24|

Select a range of ligand concentrations for the binding isotherm, being sure to include points below and above the anticipated Kd.

-

25|

Prepare NMR samples with varying concentrations of ligands, making sure to add solvent until the final volume of ligand solution is equal to the total amount of solvent that was added to the blank prepared in Step 15 (1 μl of ligand per 4 μl of DMSO, 2 μJ. of ligand per 3 μl of DMSO and so on).

-

26|

Mix the solutions well and transfer them to NMR tubes.

-

27|

Collect PrOF NMR spectra for each sample and analyze the data (Steps 13, 14 and 18).

-

28|

Plot the change in chemical shift (Δδ) as a function of ligand concentration.

-

29|

Fit the data using nonlinear regression software (e.g., OriginPro or GraphPad Prism) with the following equation to solve for Kd using equation 1, shown above.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 1.

● TIMING

Step 1, bacterial transformation: 1 d

Steps 2–10, fluorinated protein expression and purification: 2 d (plus characterization time; Box 3)

Steps 11–14, PrOF NMR: 5 min to 1 h (plus resonance assignments; Box 4)

Steps 15–19, fragment screening via PrOF NMR: variable (plus fragment mixture preparation time; Box 1)

Steps 20–23, deconvolution of fragment mixtures: variable

Steps 24–29, Kd determination of fragment compounds: variable

Box 1, fragment mixture preparation: variable

Box 2, preparation of the defined medium: 3–4 h

Box 3, fluorine incorporation characterization: 30 min to 1 h

Box 4, assigning PrOF resonances: ~3 weeks

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

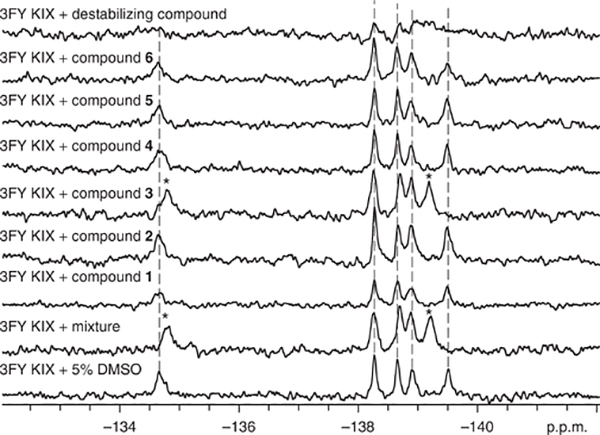

During fragment screening, resonance assignments facilitate the characterization of the binding site of small molecules and of the environmental changes experienced by the labeled protein side chain. Fragment-mixture hits can result in a large change in chemical shift (e.g., 0.1–1 p.p.m.) due to the responsiveness of fluorine to changes in its chemical environment. The 19F NMR spectra shown in Figure 6 show that a peak at −134.5 p.p.m. observed in the spectrum of the fluorinated protein 3FY-KIX undergoes a change in chemical shift of 0.32 p.p.m. in the spectrum of the same protein in the presence of a mixture of different potential ligands.

Figure 6 |.

Deconvolution of fragment mixture. The bottom spectrum corresponds to the fluorinated protein with no ligands added. Asterisks denote resonances that have been significantly perturbed. In this particular mixture, compound 3 is responsible for the chemical shift perturbation seen in the mixture. The top spectrum represents a global reduction in signal due to nonspecific effects.

Protein aggregators and denaturants, whose presence is common in many screens, can be detected by global analysis of all of the resonances present in the protein. Global coalescence, broadening or a decrease in intensity are all indications of nonspecific effects induced by the small molecule on the protein, which may lead to false positives in ligand-observed experiments (e.g., top spectrum in Fig. 6). Active molecules within a mixture are then identified by testing the molecules from the fragment mixture hit one at a time. Figure 6 shows an example of such a ‘deconvolution’, which helps to identify compound 3 as the active compound, i.e., the compound that caused the change in chemical environment sensed by the fluorine labels in the protein.

Chemical shifts are easily measured and highly reproducible. In supplementary Table 1 are reported data from two screens with 3FY-KIX and 5FW-Brd4 showing high reproducibility and low variability of chemical shifts for the protein resonances. In particular, 3FY-KIX, across 23 replicate experiments, had a standard deviation in chemical shift over five resonances from 0.011 to 0.037 p.p.m. The latter measurement was from the broadest resonance, the one assigned to fluorine-labeled Y649. Although only one resonance was observed for fluorine-labeled Y649, the potential for rotamers of the ortho-substituted phenol, from restricted motion in this environment, leads to a broadened resonance. In the case of 5FW-labeled Brd4, for which the resonances are sharper, the standard deviation range for the fluorine resonances was narrower, from 0.009 to 0.026 p.p.m. In addition, although aromatic amino acids are commonly found at protein binding sites50, labeled amino acids that are far away from the binding site serve as important internal control resonances for nonspecific binding and other factors that may globally affect the chemical shift. In the 229-compound screen with 5FW-labeled Brd4, the average change in chemical shift (Δδ) of fluorine-labeled W120, which is located outside the ligand binding site, was 0.001 ± 0.014 p.p.m. However, in the case of W81, which is located at the ligand binding site, the average Δδ of W81’s fluorine-labeled analog was 0.033 ± 0.026 p.p.m. (supplementary table 2).

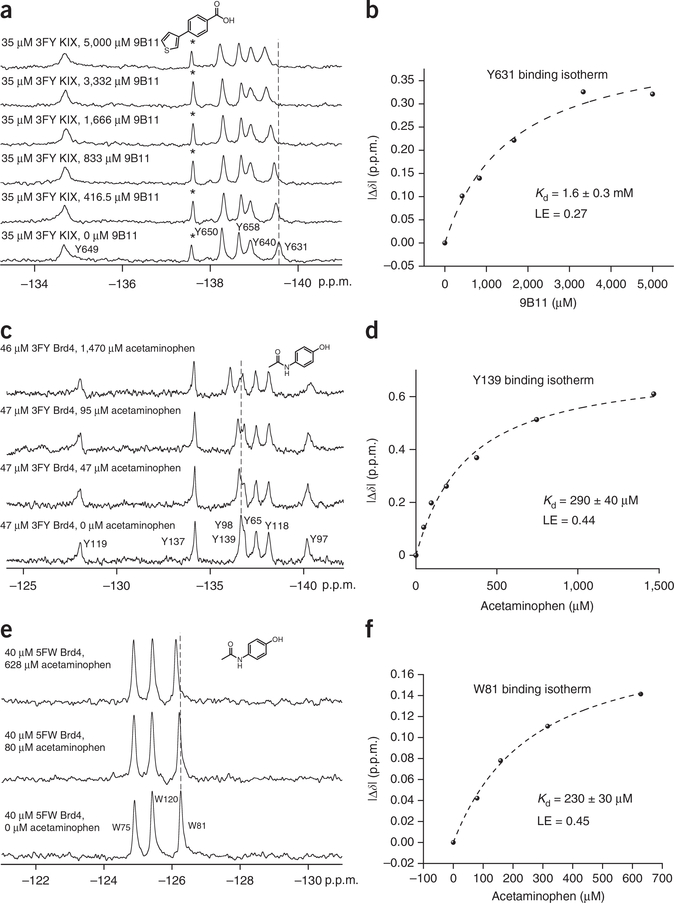

Compound affinity is determined for each fragment-hit molecule. Figure 7 shows three binding isotherms. The first binding isotherm was used to identify molecule 9B11, which is a ligand that binds to the protein KIX in the presumed MLL-binding site near Y631 (Kd = 1.6 mM, LE = 0.27). The six experiments can be completed in 30 min. In the following two binding isotherms, the protein Brd4 was separately labeled with 5FW and 3FY. Titration with the Brd4 ligand acetaminophen yielded a similar Kd value for the two proteins (LE = 0.44). Titration of two alternatively labeled proteins is a useful control for assessing any perturbing effects of fluorine on ligand-protein binding. In addition, the magnitude of chemical shift change was substantially larger for the protein labeled with 3FY than for that labeled with 5FW (0.61 p.p.m. versus 0.14 p.p.m.). These data are consistent with acetaminophen binding farther away from W81 than the affected tyrosine side chains. In some cases, more than one resonance in the NMR spectrum is affected by ligand binding. In these instances, binding isotherms can be obtained based on perturbation of each resonance, thus providing multiple dissociation constant determinations from the same experiment. An example of two affected resonance perturbations for the 5FW-labeled bromodomain, BrdT, in the presence of a new fragment is shown in Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 3, yielding comparable dissociation constants of 250 and 210 μM. The larger magnitude of the change in chemical shift is consistent with ligand binding near the presumed WPF resonance W50.

Figure 7 |.

Small-molecule titrations for Kd determination. (a) Stacked spectra for the titration of 3FY KIX with molecule 9B11 (see structure at the top of the panel). A dashed line is added for reference. The asterisk denotes a partial degradation resonance. (b) Binding isotherm generated by monitoring the change in chemical shift of fluorine-labeled Y631 as a function of small-molecule concentration. (c) Stacked spectra for the titration of 3FY Brd4 with acetaminophen (see structure at the top of the panel). A dashed line is added for reference. (d) Binding isotherm generated by monitoring the change in chemical shift of fluorine-labeled Y139 as a function of small-molecule concentration. (e) Stacked spectra for the titration of 5FW Brd4 with acetaminophen (see structure at the top of the panel). A dashed line is added for reference. (f) Binding isotherm generated by monitoring the change in chemical shift of fluorine-labeled W81 as a function of small-molecule concentration. Figure 7a,b adapted from ref. 23, Wiley-VCH Verlag/John Wiley and Sons. Figure 7c–f adapted with permission (with minor stylistic changes) from ref. 27, American Chemical Society (http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/cb5007344 ).

Hajduk et al.51 have demonstrated the efficacy of NMR-based screening methods for assessing the druggability of a protein target. Proteins with screening hit rates that are lower than 0.1% using fragment libraries are characterized as having low druggability. Upon completion of the fragment screen, PrOF NMR can also provide druggability information based on the screening hit rate, both for different proteins and for different binding sites within a single protein. As an example, of the 508 compounds screened against KIX, the MLL site was preferential for ligand binding (0.8% hit rate) over the CREB site (0% hit rate)23, consistent with previously reported work52.

In conclusion, PrOF NMR offers the medicinal chemist a useful screening platform for small-molecule fragments in early-stage ligand discovery campaigns as either a primary or secondary screen informing future ligand optimization efforts. Since the seminal studies by Sykes et al.32 on alkaline phosphatase, 19F probe developments and improvements in fluorinated amino acid incorporation have led to ligand identification and affinity quantification with small- to medium-sized proteins in a time-efficient manner11. However, in all cases, fluorine perturbation to protein function should be assessed. Although current limitations to PrOF NMR exist—including mixture deconvolution steps and CSA relaxation effects on fluorine nuclei located on protein side chains with limited mobility or in large proteins—these challenges are beginning to be addressed by complementary ligand-observed NMR methods, as well as new fluorinated amino acid labeling strategies12.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded in part by the NSF-CAREER Award CHE-1352091 (to W.C.K.P., N.K.M. and L.M.L.H.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Biotechnology training grant 5T32GM008347-23 (to A.K.U.) and NIH chemistry-biology interface training grant T32-GM08700 (to C.T.G.). The Pomerantz lab also thanks the Garber family and relatives for their generous support of this research. We also thank I. Ropson (Penn State University) for providing the DL39(DE3) cell line.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Lepre CA Practical aspects of NMR-based fragment screening. Methods Enzymol. 493, 219–239 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalvit C et al. A General NMR method for rapid, efficient, and reliable biochemical screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14620–14625 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fielding L NMR methods for the determination of protein-ligand dissociation constants. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3, 39–53 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williamson MP Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 73, 1–16 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka D et al. A Practical use of ligand efficiency indices out of the fragment-based approach: ligand efficiency-guided lead identification of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 54, 851–857 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins AL, Keseru GM, Leeson PD, Rees DC & Reynolds CH The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 105–121 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuker SB, Hajduk PJ, Meadows RP & Fesik SW Discovering high-affinity ligands for proteins: SAR by NMR. Science 274, 1531–1534 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erlanson DA, McDowell RS & O’Brien T Fragment-based drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 47, 3463–3482 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollag G et al. Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 873–886 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajduk PJ. & Greer J A decade of fragment-based drug design: strategic advances and lessons learned. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 211–219 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arntson KE & Pomerantz WCK Protein-observed fluorine NMR: a bioorthogonal approach for small molecule discovery. J. Med. Chem. 59, 5158–5171 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitevski-LeBlanc JL & Prosser RS Current applications of 19F NMR to studies of protein structure and dynamics. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 62, 1–33 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharaf NG & Gronenborn AM (19)F-Modified proteins and (19)F-containing ligands as tools in solution NMR studies of protein interactions. Methods Enzymol. 565, 67–95 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerig J Fluorine NMR. Biophysics Textbook Online 1–35 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu B et al. HTS by NMR of combinatorial libraries: a fragment-based approach to ligand discovery. Chem. Biol. 20, 19–33 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doak BC, Morton CJ, Simpson JS & Scanlon MJ Design and evaluation of the performance of an NMR screening fragment library. Aust. J. Chem. 66, 1465–1472 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegal G, Ab E & Schultz J Integration of fragment screening and library design. Drug Discov. Today 12, 1032–1039 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim SS et al. Development of inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 based on fragment screening. Aust. J. Chem. 66, 1530 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vom A et al. Detection and prevention of aggregation-based false positives in STD-NMR-based fragment screening. Aust. J. Chem. 66, 1518 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalvit C, Fagerness PE, Hadden DT, Sarver RW & Stockman BJ Fluorine-NMR experiments for high-throughput screening: theoretical aspects, practical considerations, and range of applicability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7696–7703 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dias DM et al. Is NMR fragment screening fine-tuned to assess druggability of protein-protein interactions? ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 5, 23–28 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pomerantz WC et al. Profiling the dynamic interfaces of fluorinated transcription complexes for ligand discovery and characterization. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1345–1350 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gee CT, Koleski EJ & Pomerantz WC Fragment screening and druggability assessment for the CBP/p300 KIX domain through protein-observed 19F NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 3735–3739 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung EW et al. 19F NMR as a probe of ligand interactions with the iNOS binding site of SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein 2. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 84, 616–625 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge X et al. Ligand-induced conformational change of Plasmodium falcparum AMA1 detected using 19F NMR. J. Med. Chem. 57, 6419–6427 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis-Marof R et al. 19F NMR spectroscopy monitors ligand binding to recombinantly fluorine-labelled b’x from human protein disulphide isomerase (hPDI). Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 3808–3812 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra NK, Urick AK, Ember SW, Schonbrunn E & Pomerantz WC Fluorinated aromatic amino acids are sensitive 19F NMR probes for bromodomain-ligand interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 2755–2760 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC & Wuthrich K Biased signaling pathways in beta(2)-adrenergic receptor characterized by F-19-NMR. Science 335, 1106–1110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu L, Hajduk PJ, Mack J & Olejniczak ET Structural studies of Bcl-xL/ligand complexes using 19F NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 34, 221–227 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urick AK et al. Dual screening of BPTF and Brd4 using protein-observed fluorine NMR Uncovers new bromodomain probe molecules. ACS Chem. Biol. 10 2246–2256 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zartler ER et al. RAMPED-UP NMR: multiplexed NMR-based screening for drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10941–10946 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sykes BD, Weingarten HI & Schlesinger MJ Fluorotyrosine alkaline phosphatase from Escherichia coli: preparation, properties, and fluorine-19 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71, 469–473 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frieden C, Hoeltzli SD & Bann JG The preparation of 19F-labeled proteins for NMR studies. in Methods Enzymol. Vol. 380 (eds. Michael L, Holt Johnson Jo M. & Ackers Gary K) 400–415 (Academic Press, 2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crowley PB, Kyne C & Monteith WB Simple and inexpensive incorporation of 19F-tryptophan for protein NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 48, 10681–10683 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin MP, Olesen SH, Georg GI & Schönbrunn E Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib interacts with the acetyl-lysine recognition site of bromodomains. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2360–2365 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant RG The NMR time scale. J. Chem. Educ. 60, 933 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers MT & Woodbrey JC A proton magnetic resonance study of hindered internal rotation in some substituted N,N-dimethylamides. J. Phys. Chem. 66, 540–546 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hull WE & Sykes BD Fluorotyrosine alkaline phosphatase: internal mobility of individual tyrosines and the role of chemical shift anisotropy as a 19F nuclear spin relaxation mechanism in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 98, 121–153 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho C, Pratt EA & Rule GS Membrane-bound D-lactate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli: a model for protein interactions in membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 988, 173–184 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein-Seetharaman J, Getmanova EV, Loewen MC, Reeves PJ. & Khorana HG NMR spectroscopy in studies of light-induced structural changes in mammalian rhodopsin: applicability of solution 19F NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13744–13749 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung KY et al. Role of detergents in conformational exchange of a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 36305–36311 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki Y et al. Resolution of oligomeric species during the aggregation of Abeta1–40 using (19)F NMR. Biochemistry 52, 1903–1912 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C et al. Protein (19)F NMR in Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 321 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.HammiU JT, Miyake-Stoner S, Hazen JL, Jackson JC & Mehl RA Preparation of site-specifically labeled fluorinated proteins for 19F-NMR structural characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2601–2607 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salopek-Sondi B, Vaughan MD, Skeels MC, Honek JF & Luck LA (19)F NMR studies of the leucine-isoleucine-valine binding protein: evidence that a closed conformation exists in solution. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 21, 235–246 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duewel H, Daub E, Robinson V & Honek JF Incorporation of trifluoromethionine into a phage lysozyme: implications and a new marker for use in protein 19F NMR. Biochemistry 36, 3404–3416 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang Y & Tirrell DA Biosynthesis of a highly stable coiled-coil protein containing hexafluoroleucine in an engineered bacterial host. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11089–11090 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang Y et al. Stabilization of coiled-coil peptide domains by introduction of trifluoroleucine. Biochemistry 40, 2790–2796 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HY, Lee KH, Al-Hashimi HM & Marsh EN Modulating protein structure with fluorous amino acids: increased stability and native-like structure conferred on a 4-helix bundle protein by hexafluoroleucine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 337–343 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogan AA & Thorn KS Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 280, 1–9 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hajduk PJ, Huth JR & Fesik SW Druggability indices for protein targets derived from NMR-based screening data. J. Med. Chem. 48, 2518–2525 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lodge JM, Justin Rettenmaier T, Wells JA, Pomerantz WC & Mapp AK FP tethering: a screening technique to rapidly identify compounds that disrupt protein-protein interactions. Medchemcomm. 5, 370–375 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HW, Perez JA, Ferguson SJ & Campbell ID The specific incorporation of labelled aromatic amino acids into proteins through growth of bacteria in the presence of glyphosate. Application to fluorotryptophan labelling to the H(+)-ATPase of Escherichia coli and NMR studies. FEBS Lett. 272, 34–36 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bai P, Luo L & Peng Z Side chain accessibility and dynamics in the molten globule state of alpha-lactalbumin: a (19)F-NMR study. Biochemistry 39, 372–380 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neerathilingam M, Greene LH, Colebrooke SA, Campbell ID & Staunton D Quantitation of protein expression in a cell-free system: efficient detection of yields and 19F NMR to identify folded protein. J. Biomol. NMR 31, 11–19 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akoka S, Barantin L & Trierweiler M Concentration measurement by proton NMR using the ERETIC method. Anal. Chem. 71, 2554–2557 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dalvit C et al. Sensitivity improvement in 19F NMR-based screening experiments: theoretical considerations and experimental applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13380–13385 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seyedsayamdost MR, Reece SY, Nocera DG & Stubbe J Mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted fluorotyrosines: new probes for enzymes that use tyrosyl radicals in catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1569–1579 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furter R Expansion of the genetic code: site-directed p-fluoro-phenylalanine incorporation in Escherichia coli. Prot. Sci. 7, 419–426 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitevski-LeBlanc JL, Al-Abdul-Wahid MS & Prosser RS A mutagenesis-free approach to assignment of 19F NMR resonances in biosynthetically labeled proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2054–2055 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.