Abstract

Background:

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective for preventing HIV acquisition. However, adherence among young women has been challenging. SMS reminders have been shown to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in some contexts, including in combination with real-time adherence monitoring. We therefore assessed the impact of SMS reminders on PrEP adherence among young women in Kenya over 2 years.

Methods:

The MPYA (Monitoring PrEP among Young Adult women) study was a randomized controlled trial involving 18–24-year-old women with high risk for HIV (NCT02915367). Participants were recruited from colleges/vocational institutions, informal settlements, and community-based organizations supporting young women. PrEP adherence was measured with a real-time electronic monitor and pharmacy refill. Study staff randomized participants 1:1 to SMS reminders versus no reminders. Reminders were initially sent daily and participants could switch to “as needed” reminders (i.e., sent only if they missed opening the monitor as expected) after 1 month. Study arm assignment was known to study staff but masked to investigators. Study visits occurred at 1 month, 3 months, and then quarterly. Effects of SMS reminders on adherence were assessed as the primary outcome by negative binomial models adjusted for study site and quarter.

Findings:

We enrolled 348 women between December 21, 2016 and February 5, 2018. The median age was 21 years; two-thirds reported condomless sex in the month before baseline. We assigned 173 participants to receive daily SMS reminders (24 [14%] later opted for “as needed” reminders) and 175 participants to no reminders; 97% (N=69,291/71,791) of SMS reminders were sent as planned. Among participants picking up PrEP (thus potentially indicating desire for HIV protection), electronically monitored adherence averaged 26.8% over 24 months and was similar by arm (27.0% with SMS; 26.6% without SMS; adjusted incidence rate ratio 1.16 ([95% CI 0.93, 1.45; p=0.19]). We also found no significant intervention effect when assessing electronically monitored adherence by site or for all participants regardless of PrEP refills over both 6 and 24 months. We additionally found no intervention effect when comparing study arms by pharmacy refill data over 6 and 24 months. There were no serious adverse events related to trial participation; 5 social harms occurred in each study arm, primarily related to PrEP use.

Conclusions:

SMS reminders were ineffective in promoting PrEP adherence among young Kenyan women. Given the overall low adherence in the trial, additional interventions are needed to support PrEP use in this population.

Keywords: PrEP, adherence, SMS reminders, young women, sub-Saharan Africa

Background

HIV prevention for young women in sub-Saharan Africa is a key priority for the global strategy to end the HIV epidemic. This population is particularly vulnerable to HIV acquisition based on a multitude of factors, including disproportionate power relationships with sexual partners, limited access to sexual health resources, and the biology of HIV transmission as a receptive partner during sex (1). Typical neurodevelopment associated with adolescence and young adulthood also promotes the pursuit of immediate needs (e.g., food, friends, and love) over abstract concepts (e.g., disease prevention) (2), and assessment of HIV risk is complex (3). With this backdrop, 25% of new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa occur among adolescent girls and young women (1). Concerted efforts are therefore needed to support use of effective HIV prevention tools in this population.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly effective means for preventing HIV acquisition when consistent adherence aligns with risk (4). However, adherence has been challenging for many young women. In phase III clinical trials (i.e., FEM-PrEP and VOICE), adherence was low enough that PrEP was not effective for this population (5, 6). Similar experiences have been seen in more recent studies and demonstration projects, despite adherence interventions such as tailored counseling, PrEP champions, and drug level feedback (7, 8).

SMS reminders and outreach have been shown to improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) in some, but not all, contexts (9). One study in Uganda showed significant, sustained improvement in adherence among adults initiating ART when SMS reminders were combined with a real-time adherence monitor (10); participants reported that both tools helped establish the habit of adherence and provided a sense of connection and support from the clinic (11). SMS reminders have been less well studied for adherence to PrEP, although initial experience with men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States has been mixed (12–14). Importantly, SMS may be attractive, particularly for youth, given the high and rising rates of mobile phone usage in sub-Saharan Africa (15).

To determine the impact of SMS reminders on PrEP adherence, we conducted a randomized controlled trial among young Kenyan women at high risk for HIV acquisition who were offered PrEP over a two-year period.

Methods

Setting and participants

The Monitoring PrEP among Young Adult women (MPYA, meaning “new” in Swahili) study involved 18–24-year-old women in Thika and Kisumu, Kenya at high risk for HIV acquisition. The estimated rates of HIV prevalence among women in Thika and Kisumu are 5.9% and 17.4%, respectively. We defined risk using the VOICE risk score— an evidence-based, readily usable metric that is based on age, marriage or living with a husband or primary sexual partner, provision of financial or material support by the partner, the partner having other sexual partners, and alcohol use (16). Participants were eligible if their risk score was >5, which was associated with an incidence of >5 HIV infections per 100 person-years in the VOICE study. Alternatively, women were eligible if they were in a serodifferent relationship (i.e., their sexual partner was known or suspected to be living HIV). We identified potential participants from a variety of locations: colleges/vocational institutions, informal settlements, and community-based organizations providing primary healthcare and other services to young women, including those engaged in sex work. Additional inclusion criteria were being clinically appropriate to start PrEP, sexually active within the prior three months, owning a personal cellular phone and being able to send a text message, and intending to stay in the local area for at least a year. Pregnancy and breast-feeding were exclusion criteria for entry into the study (reflecting evolving data at the time of study initiation on PrEP safety in those contexts), but those who became pregnant during follow-up had the option to continue PrEP.

Study design

The MPYA study involved an open label randomized controlled trial with parallel 1:1 intervention allocation. Study arm assignment was known to study staff but masked to investigators. The only significant protocol change was the ability to continue PrEP use during breastfeeding, if desired. This change occurred in 2017, reflecting new evidence of safety (17). The primary outcome of the study was the effect of SMS reminders on PrEP adherence, which we present in this analysis. Additional study outcomes include the impact of HIV risk behaviors and perceptions on PrEP adherence, as well as an in-depth assessment of the functionality, acceptability, and cost of the real-time adherence monitor and SMS reminders; these secondary outcomes will be published separately.

Study procedures

We presented study procedures to community advisory boards and groups of young women at each study site for input and made changes prior to implementation to reflect the interests and consensus of the community. We enrolled participants from December 21, 2016 through February 5, 2018 and followed prospectively for a two-year period as planned. The study concluded on March 27, 2020. Study visits occurred at adolescent-friendly research clinics in Thika (N=1) and Kisumu (N=1) at 1 month, 3 months, and then quarterly thereafter. Participants completed demographic and socio-behavioral questionnaires, including queries about social harms, and clinical monitoring at each study visit with data capture in REDCap. We selected socio-behavioral scales based on prior validation or use in similar settings and brevity, given the need to limit the burden of study procedures in a young population. Study sites provided PrEP as open label emtricitabine (200mg)/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (300mg) to be taken as a single, once daily tablet. Consistent with the concept of prevention-effective adherence (18), study counselors encouraged all participants to take PrEP for the first six months of the study based on high HIV risk at enrollment and thereafter advised continued PrEP use if they remained at high risk and felt like PrEP was a good option for them. Counselors used adherence data to inform counseling sessions but did not share data directly with participants to avoid potential interventional effects.

We used a real-time electronic monitor (Wisepill Technologies, South Africa) to measure PrEP adherence in all participants. This device transmits a date-and-time stamp of each opening as a proxy for medication ingestion. It also demonstrates functionality through transmission of a daily electronic heartbeat (i.e., battery life and signal strength). Records of device openings are stored on the device for later transmission in the event of poor cellular network coverage. Devices have a battery life of approximately six months. Study staff educated participants about the device at enrollment, encouraged them to open it once for each dose, and asked them to bring their devices to each study visit for battery charging or replacement. We collected dried blood spots (DBS) for tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) levels, which reflect average adherence over the several weeks prior to collection, at each study visit to assess accuracy of the electronically monitored adherence data. We analyzed DBS for TFV-DP levels (fmol/punch) among a 15% sample of non-pregnant participants randomly selected from available DBS across all visits using a validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry assay (19). We additionally tracked pharmacy refills of PrEP.

SMS intervention

We randomized participants to SMS reminders versus no reminders using a variable size block randomization scheme, stratified by study site and implemented with numbered envelopes. A study analyst generated the randomization and research assistants implemented it at each study site. Consistent with the nature of the intervention, neither participants nor study staff were blinded to each participant’s assignment. The analyst confirmed the fidelity of randomization with tracking in REDCap. We managed the SMS reminders through an automated platform (Ajua, Kenya), which limited contamination of the intervention between study arms (e.g., human error leading to SMS reminders being sent to the participants in the control arm). The platform initially sent daily SMS, although participants could opt for “as needed” reminders at any time from Month 1 onwards (i.e., SMS sent only if they missed opening the monitor at the expected time). To personalize the impact of the SMS reminders, participants chose the content of their reminder and study staff asked if they wished to change it at each study visit. We encouraged participants to avoid words like “HIV” and “PrEP” and to routinely delete the SMS to help protect their privacy.

Data analysis

We analyzed participant characteristics descriptively and compared categories with chi-squared tests. We considered participants retained if they attended a study visit and/or their adherence continued to be monitored electronically. The latter criterion leveraged the data available with real-time technology that contributed to our primary study outcome. Importantly, PrEP obtained at study visits could be taken at any time throughout the study period.

The primary outcome of the study was electronically monitored adherence, defined as openings of the adherence monitoring device recorded among days with functional monitoring (number of days on which an opening event was recorded divided by the number of days with functional monitoring). We summarized data over the period prior to each study visit, censoring data if the study drug was held for an adverse event. We capped adherence at one opening per day to avoid potential misclassification from “curiosity openings” (i.e., opening the device without removing a dose). Secondary adherence outcomes were pharmacy refill and TFV-DP levels by DBS. We predefined two co-primary analyses. First, we restricted data to time periods during which participants chose to pick up PrEP. We considered assessment of executed adherence to be most relevant for those with the potential to take it. Additionally, this population may reflect prevention-effective adherence (i.e., they indicated perceived ongoing risk for HIV by picking up the prescription), although other factors could have influenced refills. Second, we analyzed all participants regardless of PrEP refills (i.e., an intention-to-treat approach). We planned both analyses for 6 and 24 months of follow-up. The study had 80% power to assess a 10% difference in mean individual adherence between randomization arms, assuming a two-sided alpha of 0.05, standard deviation of 30% in both arms, and 15% loss-to-follow up with a sample of 337 participants.

We assessed the effect of SMS reminders on adherence using a population averaged negative binomial count model with robust standard errors adjusted for study site and quarter. We had initially planned to use Poisson regression; however, the count data was overdispersed with the variance is greater than the mean. For each participant, the outcome was the count of pills taken, offset by the number of days pill taking was expected (accounting for device functionality). We used an interaction term in a post-hoc analysis to assess for different effects by site. The model produced estimates of the adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR), describing the increase in rate of pill taking associated with the randomization arm. We similarly assessed differences in pharmacy pick up by randomization arm using a negative binomial model adjusted for study site and quarter. We used Spearman’s correlation to examine the strength of correlation between DBS TFV-DP levels and electronically monitored adherence over the preceding 30 days in the same participant. We conducted all analyses using STATA (version 13.0, StataCorp, Texas, USA) and registered the trial at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02915367)

Trial oversight

An independent data safety and monitoring board reviewed the study biannually with particular attention to potential for social harms. The board evaluated data in a unblinded fashion and made no recommendations for premature study termination. Investigators also presented the study to community advisory groups in each site.

Ethics

The institutional regulatory boards at the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Partners Healthcare/Massachusetts General Hospital, and the University of Washington approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent in Swahili, Luo, or English per the participant’s preference.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all data in the study, and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

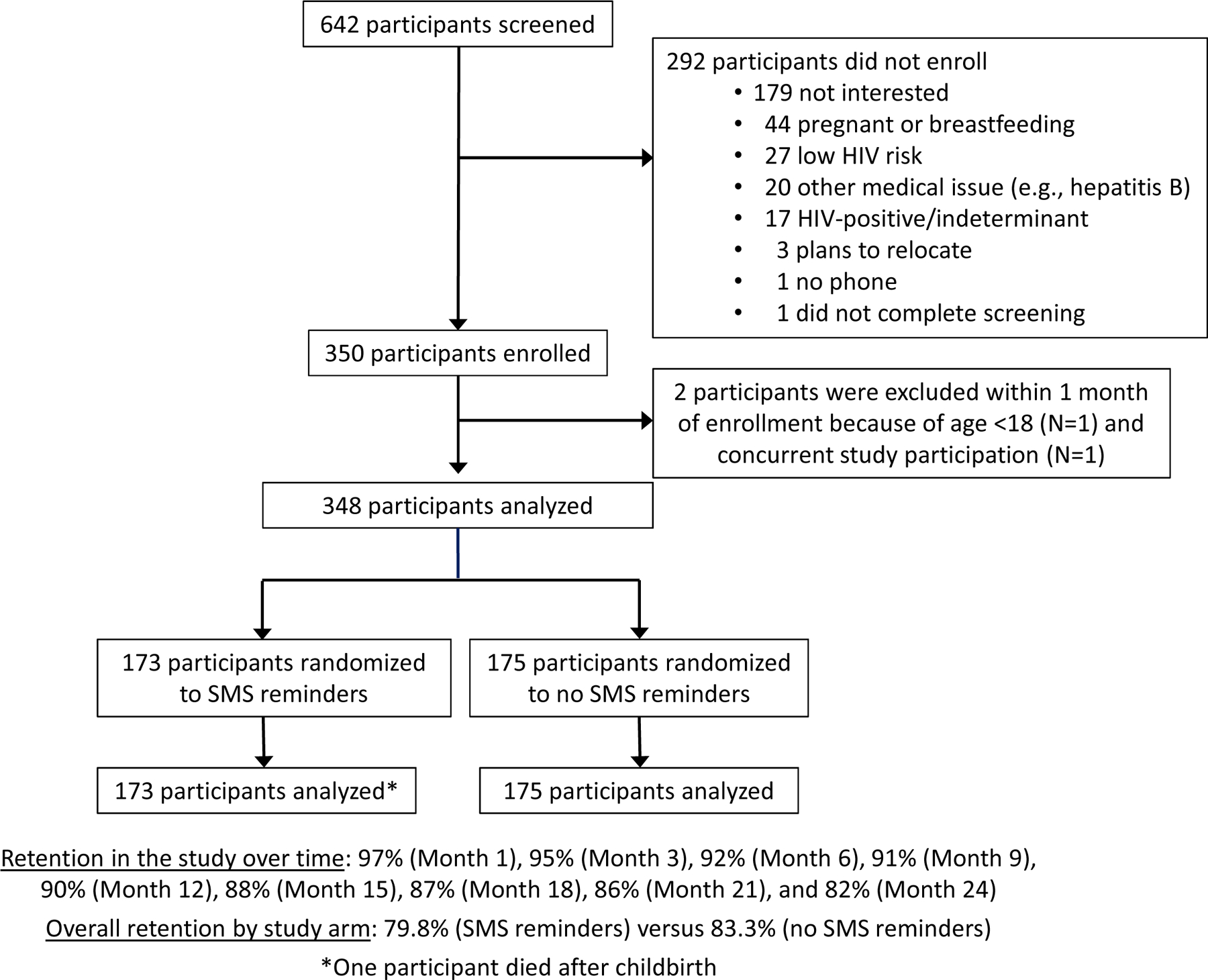

We screend 642 participants for study participation; the primary reason for non-participation was lack of interest in the study. As shown in Figure 1, we enrolled and followed 348 participants. Median follow-up was 22.1 months (interquartile range [IQR] 22.0, 23.0) per participant.

Figure 1.

Participant flow

Participant characteristics at enrollment are presented in Table 1. Demographic and behavioral characteristics were largely similar (i.e., <10% difference) between the two arms with the exception of problematic alcohol use, which was more common in the SMS reminder arm (41 [24%] versus 25 [14%]).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline by randomization arm.

| Characteristic | SMS reminders (N=173) |

No SMS reminders (N=175) |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) or Median (IQR) | N (%) or Median (IQR) | |

| Study site | ||

| Thika | 86 (50%) | 88 (51%) |

| Kisumu | 87 (50%) | 86 (49%) |

| Age (years) | 21 (19, 22) | 21 (19, 22) |

| Education (years) | 12 (9.5, 13.0) | 12 (10.0, 13.0) |

| VOICE risk score (16) | 7 (6, 7) | 7 (6, 7) |

| Sex acts in prior month | 2 (1, 5) | 2 (1, 5) |

| >1 total current sexual partner | 64 (37%) | 57 (33%) |

| Any condomless sex in past month | 111 (65%) | 117 (67%) |

| Partner provides financial or material support | 77 (45%) | 92 (53%) |

| Sexual relationship powera | 2.7 (2.5, 2.9) | 2.7 (2.5, 2.9) |

| Sexual intimate partner violenceb | 27 (16%) | 28 (16%) |

| Possible depressionc | 11 (6%) | 11 (6%) |

| Problematic alcohol used | 41 (24%) | 25 (14%) |

| Travel to study site >1 hour | 56 (33%) | 59 (34%) |

IQR = interquartile range, N = number participants.

The Sexual Relationship Power Scale has been validated in young Kenyan women (20) and reflects the median of 15 items with Likert responses; scores range from 1–4 with higher scores indicating less power in the relationship.

We measured intimate partner violence with a modified Conflict Tactics scale (21), which has been widely used internationally including in East Africa (a response of ‘yes’ to one or more of the three items indicates the presences of violence).

We assessed depression by the PHQ-2, which has been found to be valid and reliable in Western Kenya (22) (a response of ‘yes’ to either question is considered as possible depression).

We measured alcohol use with the RAPS-4, which has been used with high sensitivity in numerous countries, including South Africa (23); a response of ‘yes’ to one or more items is considered problematic alcohol use in the past year).

Of the 348 women enrolled in the study, we assigned 173 to SMS reminders and 175 to no reminders; 97% (N=69,291/71,791) of all SMS reminders were sent as planned. Technical difficulties early in implementation prevented the transmission of the remaining 3% (N=2,500) of SMS reminders. Twenty-four participants opted for “as needed” reminders (14% overall and 16% of the 153 participants taking PrEP from Month 1 onward). Table 2 indicates the most common SMS content selected by participants. No cross-over of study arms occurred.

Table 2.

SMS content selected by participants at enrollment (N=173)

| Message category | Examples | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Name or greeting with a name | “Good evening Mary” | 40 (23%) |

| Generic reminders | “It’s time” | 35 (20%) |

| Generic greeting | “Hi”, “Mambo” (“What’s up” in Swahili) | 28 (16%) |

| Food or drink | “Take your tea” | 26 (15%) |

| Study reference or PrEP | “PrEP reminder”, “MPYA” | 14 (8%) |

| Prayer or inspirational words | “Pray”, “Tialala” (“Yes” in local slang) | 9 (5%) |

| Other | “Flower”, “Safaricom”, “Sasa” (“Now” in Swahili) | 21 (12%) |

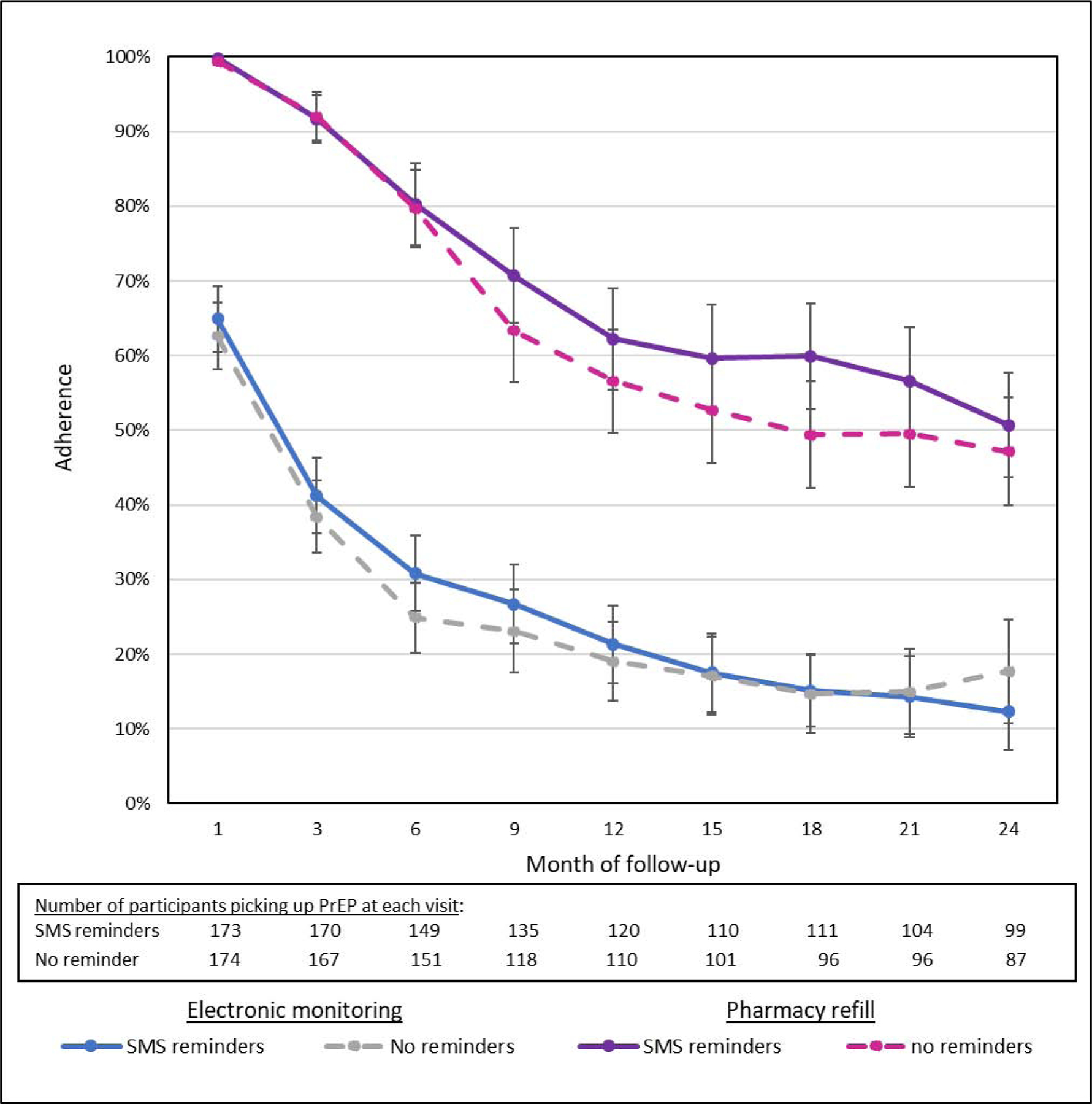

Figure 2 shows electronically monitored adherence and pharmacy refill data. We considered 4,543 participant-months in the analysis of prevention-effective adherence (i.e., during periods when PrEP was picked up) and 7,848 participant-months in the intention-to-treat analysis. Fifty-nine (34.1%) participants in the SMS reminder arm and 58 (33.1%) participants in the no SMS reminder arm chose to permanently stop PrEP during the course of the study. The availability of PrEP adherence monitoring data was similar by study arm. We censored electronically monitored adherence data for 12.8% (15,165/118,456) and 11.2% (13,445/120,550) of participant-days in the SMS reminder and no SMS reminder study arms, respectively, due to non-functional monitors; the primary cause of non-functional devices was participants not bringing them to the study site for charging. We censored an additional 111/3,600 (3%) and 71/3,638 (2%) participant-months primarily due to breastfeeding and seroconversion (N=4) in the SMS reminder and no SMS reminder study arms, respectively. We did not detect drug resistance among three participants who acquired HIV; the test for the fourth participant acquiring HIV could not be amplified.

Figure 2.

PrEP adherence by electronic monitoring and pharmacy refill by study arm. Adherence was averaged for participants picking up PrEP at each visit; error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals.

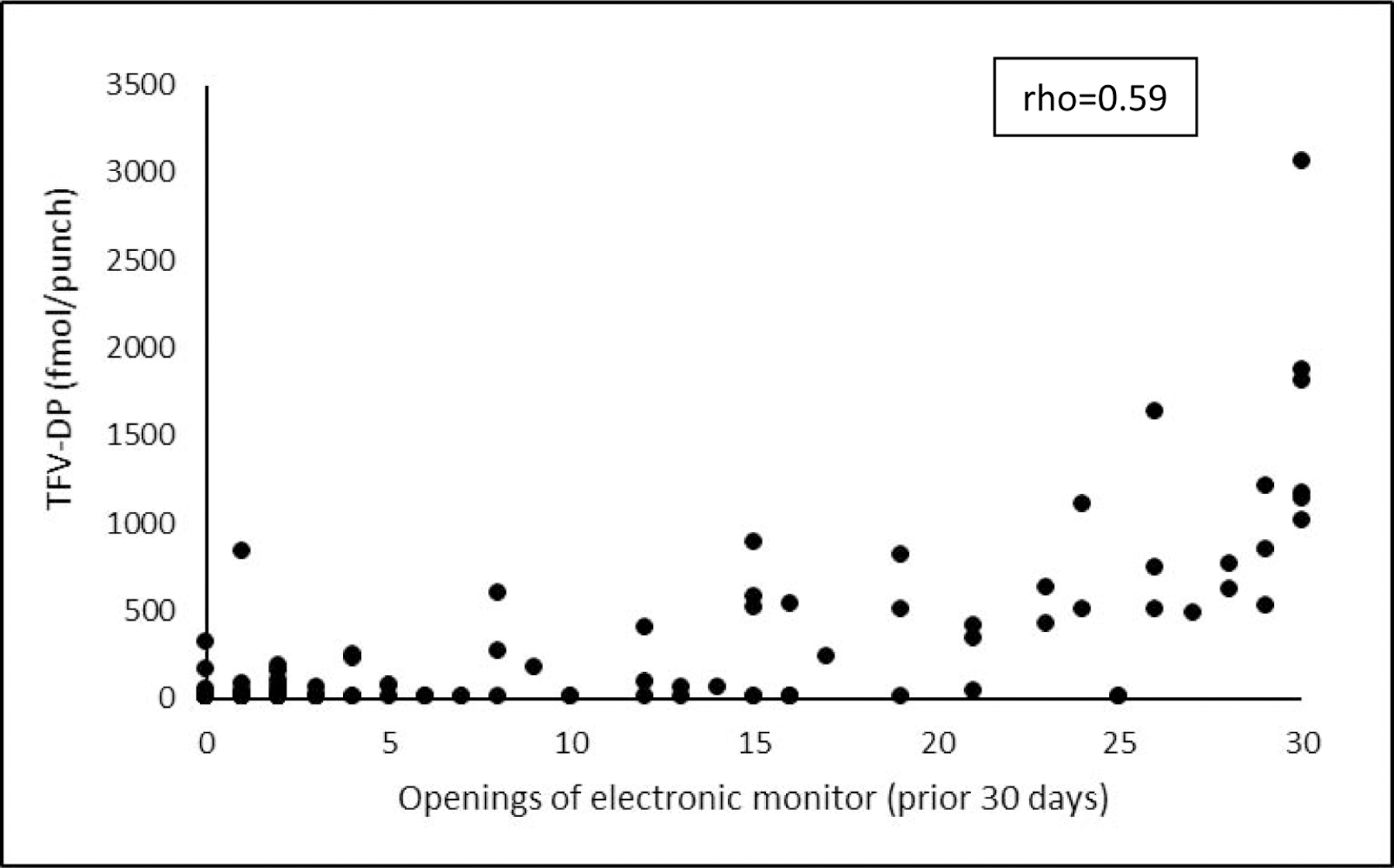

During periods when participants chose to pick up PrEP, electronically monitored adherence was 38.5% of doses over 6 months of follow-up and was similar by arm (40.2% among women receiving SMS reminders; 36.8% without SMS). Over 24 months of follow-up, electronically monitored adherence was 26.8% of doses and was again similar by arm (27.0% among women receiving SMS; 26.6% without SMS). When adjusting for site and study quarter, no statistically significant difference was present at 6 months (aIRR 1.14 [95% CI 0.96, 1.34; p=0.13] or at 24 months (aIRR 1.16 [95% CI 0.92, 1.45; p=0.19]). We found significant differences in electronically monitored adherence levels between the two study sites (aIRR 0.65 [95% CI 0.54, 0.84; p<0.001]); however, the effect of the intervention did not differ statistically by site (p=0.86 for the interaction term). No intervention effect was present when assessing electronically monitored adherence regardless of PrEP refills (aIRR 1.14 [95% CI 0.90, 1.43; p=0.28]). Additionally, we observed no difference in pharmacy pick-up between the two randomization arms over 6 months (aIRR 1.01 [95% CI 0.95, 1.07]; p=0.86) or 24 months (aIRR 1.10 [95% CI 0.97, 1.24; p=0.13]). As shown in Figure 3, the correlation between electronic adherence monitoring and DBS had a rho of 0.59 overall (0.56 in the SMS reminder arm and 0.66 in the no SMS reminder arm; p=0.41).

Figure 3.

Correlation between electronically-monitored adherence and tenofovir-diphosphate levels (fmol/punch). Electronically-monitored values reflect the 30 days prior to collection of the drug level.

No serious adverse events were related to study participation. The only adverse drug event was vomiting in one participant in the SMS reminder arm. Social harms probably or definitely related to study participation were also the same in both study arms (5 each) and consisted of verbal and physical abuse with a sexual partner. These harms were primarily related to PrEP use, although one also involved the SMS. No participants declined SMS reminders or left the study because of social harms. Forty-six and 56 participants became pregnant in the SMS reminder and no SMS reminder arms, respectively, of whom 32 (70%) and 34 (61%) chose to continue PrEP during the pregnancy.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, SMS reminders did not improve PrEP adherence among young women in Kenya. This finding was consistent for both electronically monitored adherence and pharmacy refill data and did not vary over time or by study site. One of the primary analyses purposefully focused on the women choosing to take PrEP, given that executed adherence is most relevant for those choosing to take it. Moreover, pharmacy refill may serve as a proxy for a desire and/or need for HIV prevention. This approach is consistent with prevention-effective adherence, or the alignment of adherence with periods of risk (18), although other factors may be relevant (e.g., inaccurate self-assessment of risk). When considering an intention-to-treat approach, results were similar.

Adherence by both electronic adherence monitoring and pharmacy refill decreased considerably after a few months of PrEP use, as has been seen in several other PrEP studies and demonstration projects (8, 24). Pharmacy refill indicates the maximal possible adherence, and the consistently lower adherence by electronic monitoring suggests that participants may not have taken many of the doses available to them. Alternatively, some women may have taken PrEP without opening the monitor for each dose (i.e., “pocket doses”); however, the moderately high correlation between electronically monitored adherence and TFV-DP levels gives some confidence in the accuracy of the former. In any case, even if misclassification occurred by either measure, bias between the study arms would be unlikely and would not impact the null findings of the trial.

We considered SMS reminders as a promising means to promote adherence among young women for several reasons. First, they have been shown in prior research to help establish a daily habit of adherence (11). Most young women do not take medication on a daily basis, especially for disease prevention, and have had similar adherence challenges with taking daily oral contraceptives (25). Although widely available, oral contraceptives constitute a small fraction of utilized family planning options and may reflect lack of desire or ability to take a daily pill. Long acting injectables and implantable contraception are clearly preferred, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and have higher rates of success. Similar formulations for PrEP are currently in development (26) and may serve young (and older) women well if they have rapidly changing or difficult to assess HIV risk, have trouble with accessing the clinic, and/or simply desire the convenience. Morover, choice is empowering and the ability to switch between methods depending on life circumstances could lead to higher adherence.

We also saw SMS reminders as a promising means of social support for young women. Prior research has indicated that SMS are perceived as an extension of the clinic, indicating clinicians’ concern for their well-being (11, 27). The high retention in this study speaks to the comfort the participants had with the study staff. The high levels of pharmacy refills may also reflect a desire to reciprocate on their support, rather than to actually take the pills. Qualitative research to understand the meaning of SMS reminders, feelings of social support, and any associated social desirability bias will be important to explore.

Finally, we saw SMS reminders as a possible way to harness the pervasive presence of digital technology in the lives of young women. In our study, all but one young woman approached for study participation had her own cell phone and none required training. Similar experience with technology can be found across sub-Saharan Africa with particularly high rates of cell phone ownership in Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria (15). However, the ubiquitous presence of technology may have been a detriment rather than an advantage. When the landmark Wel-Tel study first showed SMS reminders to be supportive of adherence to ART in Kenya a decade ago, SMS were novel and may have been experienced as more special and meaningful than they are today. SMS are now commonplace and often a nuisance (e.g., uninvited and undesirable marketing messages, or SPAM). Indeed, a study of SMS reminders for ART adherence among adolescents in Uganda similarly found no benefit in 2017 (28), and the authors concluded that simple reminder messages may not be enough to capture the attention of recipients. We tried to anticipate SMS fatigue by offering the option of “as needed” reminders, but only a minority of participants selected them over the daily reminders for unclear reasons. Given the rapidly evolving nature of digital technology, on-going assessment of the latest apps and devices will be important for future intervention development.

In light of our trial findings and the ever more crowded space of digital technology, we must reenvision the role for mHealth in supporting medication adherence. Some promise may be seen in another study among Ugandan adolescents living with HIV in which SMS were used to inform participants not only of their own adherence, but that of their peers (29). That approach also involved a real-time adherence monitor and built on “reference dependence bias”—the tendency of individuals to want to equal or surpass the performance of their peers. Similar efforts could be tried with PrEP. Drug level feedback has shown some potential impact for PrEP adherence among MSM in the US (30). Similar benefit was not seen with young African women (8), although feedback of results was delayed by several weeks. Real-time adherence feedback could be achieved through text messages associated with electronic or ingestion monitoring or through immediate display of results with point-of-care urine-based adherence monitoring (31); these novel approaches may be considered for future research.

Alternatively, mHealth tools could be used to trigger and facilitate engagement with PrEP beyond reminders. Structural barriers (e.g., distance to clinic, adolescent-unfriendly services) and stigma are known barriers to PrEP uptake and persistence (32). Digital communication platforms could be used to request and support PrEP delivery for community-based care in preferred settings. The PrEP@Home intervention uses a web portal and video to support PrEP use for MSM in the US and has been shown to be feasible and acceptable (33). A similar intervention is underway for young women in Kenya that uses SMS or WhatsApp to arrange convenient PrEP delivery with supporting video guidance on smart phones (NCT04408729). These approaches reflect an evolution in mHealth that aims to keep pace with its target audience.

This study has a number of strengths and limitations. The randomized, controlled nature of the study design supports the rigor of the findings, and the populations in the two study arms were quite similar. This study was also well-powered and had high levels of retention. Additionally, contamination was minimized through the automated SMS delivery in the study, although sharing of messages among participants may have occurred. One limitation is reduced generalizability through the use of electronic adherence monitors. Although these monitors enhanced understanding of adherence, effects of SMS reminders on PrEP adherence without concurrent monitoring is unknown. Additionally, risk for HIV acquisition is complex and may not have been adequately captured through our use of the VOICE risk score. Use of PrEP and the effect of SMS reminders may vary in other groups of young women.

In conclusion, our randomized, controlled trial found no benefit for SMS reminders in supporting PrEP adherence among young women in Kenya. Most women expressed prolonged interest in PrEP based on continued pharmacy refills, yet a minority persisted in taking PrEP over the study period according to the electronic monitoring data. Future work should consider alternate PrEP formulation options that are less reliant on daily behaviors, which may appeal to many women. For those who desire a daily pill and/or struggle with engagement in their sexual and reproductive health, alternative strategies to promote adherence will be needed. Novel uses of technology to mitigate challenges in both the use and delivery of PrEP may also be beneficial.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Because SMS reminders have been successful in promoting adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy in some contexts, SMS reminders are now being considered to support adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In a PubMed search, unrestricted by language or date, we used the search terms “HIV”, “pre-exposure prophylaxis”, “PrEP”, “adherence”, and (“text message” or “SMS”). We identified 27 unique articles from 2012–2020, of which eight described studies of adherence interventions. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involved men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US and had mixed results. Three additional articles described proposed or ongoing studies of text message interventions to improve PrEP adherence in young women in Zimbabwe, black MSM in New York, and MSM and transgender women who have sex with men (TGWSM) in Thailand. Another study is also underway involving a social networking gamification app with adherence counseling delivered via two-way text messaging among young MSM and TGWSM in the US. Nineteen studies described preferences and feasibility assessments or utilized text messages for the collection of data on adherence, sexual activity, and/or other behaviors. No studies presented RCTs of text message interventions for PrEP use in young women. The only study involving young women was a pilot pre-post assessment in Kenya that found two-way SMS communication was associated with improved follow-up and PrEP continuation at one month.

Added value of this study

The findings of this trial present the first RCT of text message reminders for PrEP adherence among young women and show no benefit. We utilized multiple objective measures of adherence and assessed both short- and long-term follow-up, which add strength to our findings.

Implications of all the available evidence

Given the body of evidence to date, the impact of text message reminders on PrEP adherence appears to vary by population. Evidence to date among young women is quite limited, but the lack of intervention effect in our study suggests the need for additional interventions to support PrEP use in this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the MPYA Study participants and our community advisory boards. The US National Institutes of Health (R01MH109309) funded the study and Gilead provided emtricitabine-tenofovir for use as PrEP.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH109309); study medication was provided by Gilead.

Funding: National Institutes Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Prior presentation of results: An abstract with the primary findings of this manuscript was submitted to the Research for Prevention (R4P) Conference 2020.

Trial registration: NCT02915367; the full protocol is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

JEH reports personal fees from Merck, outside the submitted work; KN reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences and Merck; PA reports personal fees and grants from Gilead Sciences; and JMB reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences, Janssen, and Merck, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data sharing

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification, are available following the article’s publication and under appropriate data sharing agreements. We will also provide the study protocol, data dictionary, statistical analysis plan, and language of the consent forms. Data are available for researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal, which should be directed to jhaberer@mgh.harvard.edu.

Contributor Information

Jessica E. Haberer, Center for Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Elizabeth A. Bukusi, Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya; Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Nelly R. Mugo, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Center for Clinical Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Thika, Kenya

Maria Pyra, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Catherine Kiptinness, Center for Clinical Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Thika, Kenya.

Kevin Oware, Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya.

Lindsey E. Garrison, Center for Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Katherine K. Thomas, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Nicholas Musinguzi, Global Health Collaborative, Mbarara, Uganda.

Susan Morrison, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Peter L. Anderson, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA

Kenneth Ngure, Center for Clinical Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Thika, Kenya; Department of Community Heath, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nairobi, Kenya.

Jared M. Baeten, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

References

- 1.Ziraba A, Orindi B, Muuo S, Floyd S, Birdthistle IJ, Mumah J, et al. Understanding HIV risks among adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: Lessons for DREAMS. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0197479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg L A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-Taking. Dev Rev 2008; 28:78–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psaros C, Milford C, Smit JA, Greener L, Mosery N, Matthews LT, et al. HIV Prevention Among Young Women in South Africa: Understanding Multiple Layers of Risk. Arch Sex Behav 2018; 47:1969–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution: from clinical trials to routine practice. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11:10–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mugwanya KK, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, Lagat H, Begnel ER, et al. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis delivery in routine family planning clinics: A feasibility programmatic evaluation in Kenya. PLoS Med 2019; 16:e1002885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celum C, Mgodi N, Bekker L-G, Hosek S, Donnell D, Anderson PL, et al. , editors. PrEP adherence and effect of drug level feedback among young African women in HPTN 082. International AIDS Conference 2019; Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amankwaa I, Boateng D, Quansah DY, Akuoko CP, Evans C. Effectiveness of short message services and voice call interventions for antiretroviral therapy adherence and other outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0204091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haberer JE, Musiimenta A, Atukunda EC, Musinguzi N, Wyatt MA, Ware NC, et al. Short message service (SMS) reminders and real-time adherence monitoring improve antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural Uganda. AIDS 2016; 30:1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware NC, Pisarski EE, Tam M, Wyatt MA, Atukunda E, Musiimenta A, et al. The Meanings in the messages: how SMS reminders and real-time adherence monitoring improve antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural Uganda. AIDS 2016; 30:1287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colson PW, Franks J, Wu Y, Winterhalter FS, Knox J, Ortega H, et al. Adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis in Black Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in a Community Setting in Harlem, NY. AIDS Behav 2020. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, von Felten P, Rivet Amico K, Anderson PL, Lester R, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mobile Health Intervention to Promote Retention and Adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Young People at Risk for Human Immunodeficiency Virus: The EPIC Study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:2010–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore DJ, Jain S, Dube MP, Daar ES, Sun X, Young J, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Daily Text Messages to Support Adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis in Individuals at Risk for Human Immunodeficiency Virus: The TAPIR Study. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1566–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GSM Association. The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa, 2019. Available from: www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/sub-saharan-africa/. Accessed 27 September 2020.

- 16.Balkus JE, Brown E, Palanee T, Nair G, Gafoor Z, Zhang J, et al. An Empiric HIV Risk Scoring Tool to Predict HIV-1 Acquisition in African Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 72:333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mugwanya KK, Hendrix CW, Mugo NR, Marzinke M, Katabira ET, Ngure K, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis Use by Breastfeeding HIV-Uninfected Women: A Prospective Short-Term Study of Antiretroviral Excretion in Breast Milk and Infant Absorption. PLOS Medicine 2016; 13:e1002132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, Curran K, Koechlin F, Amico KR, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS 2015; 29:1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng JH, Rower C, McAllister K, Castillo-Mancilla J, Klein B, Meditz A, et al. Application of an intracellular assay for determination of tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate from erythrocytes using dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2016; 122:16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulerwitz J, Mathur S, Woznica D. How empowered are girls/young women in their sexual relationships? Relationship power, HIV risk, and partner violence in Kenya. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0199733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young CR, Kaida A, Kabakyenga J, Muyindike W, Musinguzi N, Martin JN, et al. Prevalence and correlates of physical and sexual intimate partner violence among women living with HIV in Uganda. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0202992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monahan P, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong’or WO, Omollo O, et al. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in Western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Borges G, Cremonte M, Marais S, et al. Cross-national performance of the RAPS4/RAPS4-QF for tolerance and heavy drinking: data from 13 countries. J Stud Alcohol 2005; 66:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyongo J, Kiragu M, Karuga R, Ochieng C, Ngunjiri A, Wachihi C, et al. , editors. How long will they take it? Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) retention for female sex workers, men who have sex with men and young women in a demonstration project in Kenya. International AIDS Conference; 2018; Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooper DJ. Attitudes, awareness, compliance and preferences among hormonal contraception users: a global, cross-sectional, self-administered, online survey. Clin Drug Investig 2010; 30:749–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho LE, Torres TS, Veloso VG, Landovitz RJ, Grinsztejn B. Pre-exposure prophylaxis 2.0: new drugs and technologies in the pipeline. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e788–e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairbanks J, Beima-Sofie K, Akinyi P, Matemo D, Unger JA, Kinuthia J, et al. You Will Know That Despite Being HIV Positive You Are Not Alone: Qualitative Study to Inform Content of a Text Messaging Intervention to Improve Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018; 6:e10671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linnemayr S, Huang H, Luoto J, Kambugu A, Thirumurthy H, Haberer JE, et al. Text Messaging for Improving Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence: No Effects After 1 Year in a Randomized Controlled Trial Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Am J Public Health 2017; 107:1944–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacCarthy S, Wagner Z, Mendoza-Graf A, Gutierrez CI, Samba C, Birungi J, et al. A randomized controlled trial study of the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary impact of SITA (SMS as an Incentive To Adhere): a mobile technology-based intervention informed by behavioral economics to improve ART adherence among youth in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landovitz RJ, Beymer M, Kofron R, Amico KR, Psaros C, Bushman L, et al. Plasma Tenofovir Levels to Support Adherence to TDF/FTC Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in MSM in Los Angeles, California. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:501–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinelli MA, Haberer JE, Chai PR, Castillo-Mancilla J, Anderson PL, Gandhi M. Approaches to Objectively Measure Antiretroviral Medication Adherence and Drive Adherence Interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2020; 17:301–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maseko B, Hill LM, Phanga T, Bhushan N, Vansia D, Kamtsendero L, et al. Perceptions of and interest in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use among adolescent girls and young women in Lilongwe, Malawi. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0226062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegler AJ, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Patel RR, Ahlschlager LM, Kraft CS, et al. Developing and Assessing the Feasibility of a Home-based Preexposure Prophylaxis Monitoring and Support Program. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:501–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.