Abstract

Introduction

Accurate identification of patients with cirrhosis is important for research using administrative databases. We aimed to examine the accuracy of several major ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis diagnosis in a large and diverse patient cohort; there is little existing research on this topic.

Methods

Using data from 3,396 patients with chronic liver disease (hepatitis B or C or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) from 1 university and several community medical centers, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for several major ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, which was verified by individual chart review. We performed a secondary validation in a general cohort of 1,560 randomly selected patients.

Results

While each of the individual study ICD-10 codes were specific (98.08–100%), none of the codes were sufficiently sensitive (0.27–55.70%). PPVs were high in the chronic liver disease cohort (88.41–100%) but lower in the general population (55.53–66.76%). The AUROC for having at least 1 code was higher (0.79) than any code alone (0.50–0.65).

Discussion/Conclusion

Individual ICD-10 codes are suboptimal for identifying patients with cirrhosis in the general patient population. We recommend conditioning ICD-10 code searches with a chronic liver disease diagnosis code and/or combining diagnostic codes to maximize performance.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, International Classification of Diseases, Validation study

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis affects more than 600,000 persons in the USA [1] and causes over 1 million deaths per year worldwide [2]. Clinical research teams, health-care administrators, and other stakeholders use the International Classification of Diseases coding system to identify patients with cirrhosis from databases and electronic health records for various purposes, including outcomes research [3, 4]. The USA transitioned from the ninth (ICD-9) to the tenth revision (ICD-10) of this coding system on October 1, 2015, but it is not clear how sensitive and specific the ICD-10 coding system is for the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. To the best of our knowledge, there is only 1 existing brief research correspondence presenting only the positive predictive value (PPV) for ICD-10 codes (no data on sensitivity, specificity, or negative predictive value [NPV]) using a Veterans Affairs (VA) cohort [5]. In this study, we aimed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for several major ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, using patients pulled from diverse health-care settings.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively studied 3,396 adult patients from our chronic viral hepatitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) databases, who were seen at academic medical centers and community-based health-care clinics and hospitals between January 10, 2015, when the ICD-10 system was instituted, and June 11, 2017 (1127 HBV, 524 HCV, and 1745 NAFLD patients). The entire medical record of each patient was reviewed individually by a researcher, using a case report form to confirm liver disease etiology, presence of cirrhosis, and other relevant demographic, laboratory, radiological, histological, and clinical data. The gold standard was cirrhosis diagnosis by individual chart review, confirmed by the presence of at least one of the following: stage IV fibrosis on liver biopsy; transient elastography (FibroScan®) or FibroSure® results consistent with cirrhosis; evidence of cirrhosis on imaging (ultrasound, CT, or MRI); presence of hepatic decompensation in the context of underlying liver disease (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, or variceal hemorrhage); or documentation of cirrhosis in physician notes.

To generalize our results to the patient population without known chronic liver disease, we performed a secondary validation using a cohort of 1,560 adult patients, randomly selected from a total of 4,714 patients identified with at least one of the study ICD-10 codes between January 10, 2015, and June 11, 2017, from the entire Stanford University Medical Center EHR (as opposed to our viral hepatitis and NAFLD research databases). We then performed individual chart review of these 1,560 patients to confirm cirrhosis diagnosis using the criteria described above.

We calculated sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUROC for each code in the chronic liver disease cohort. Sensitivity is the probability that a patient with cirrhosis was correctly assigned a given ICD-10 code. Specificity is the probability that a patient without cirrhosis was not assigned a given code. PPV is the probability that a patient with a given code actually had cirrhosis. NPV is the probability that a patient without a given code actually did not have cirrhosis. AUROC measures the overall diagnostic performance, and values range from 0.5 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect prediction and 0.5 indicates prediction that is no better than chance alone. AUROC values above 0.7 are considered acceptable.

Note that we only calculated PPV in the secondary validation, as all patients in this cohort already had at least 1 ICD-10 code for cirrhosis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Results

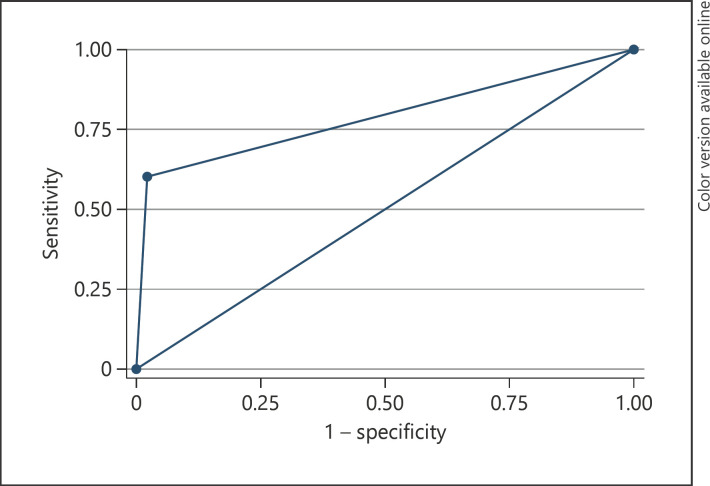

The main patient cohort included 3,396 patients, all with chronic liver diseases. Among these, 21.94% had cirrhosis (Table 1). The mean age of this cohort was 55.6 ± 13.9 years, and 52.5% were male. The cohort was also ethnically diverse, with 32.1% non-Hispanic white, 16.6% Hispanic/Latino, 46.5% Asian, 2.5% non-Hispanic black, and 2.3% other/unknown. About half of the cohort had viral diseases (33.19% HBV and 15.43% HCV) and about half had NAFLD (51.38%). In this cohort, we found that each of the individual study ICD-10 codes were specific (98.08–100%), but none of them were sufficiently sensitive (0.27–55.70%) (Table 2). Only code K74.60 had an AUROC value above 0.7 (0.77). The presence of any of the selected codes improved sensitivity to 60.4% and AUROC to 0.79 (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the PPV and NPV were high for all selected codes (88.4–100% and 78.1–88.74%, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 3,396)

| Age on January 10, 2015, mean ± SD | 55.59±13.91 |

| Male, n (%) | 1,784 (52.53) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,082 (32.06) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 559 (16.56) |

| Asian | 1,570 (46.52) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 85 (2.52) |

| Other/unknown | 69 (2.34) |

| Cirrhotic (total), n (%) | 745 (21.94) |

| Compensated, n (%) | 317 (42.55) |

| Decompensated,* n (%) | 428 (57.45) |

| Etiology, n (%) | |

| HBV | 1,127 (33.19) |

| HCV | 524 (15.43) |

| NAFLD | 1,745 (51.38) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma, n (%) | 147 (4.33) |

NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Defined as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, or variceal hemorrhage in the context of underlying liver disease.

Table 2.

Performance characteristics of ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis

| Code | Definition | Sensitivity, % (n) [95% CI] | Specificity, % (n) [95% CI] | PPV, % (n) [95% CI] | NPV, % (n) [95% CI] | AUROC, % [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K74.60 | Unspecified cirrhosis of liver | 55.70 (415/745) [52.14–59.27] |

98.08 (2,600/2,651) [97.55–98.60] |

89.06 (415/466) [86.22–91.89] |

88.74 (2,600/2,930) [87.59–89.88] |

0.7689 [0.7509–0.7869)] |

| K76.6 | Portal hypertension | 30.47 (227/745) [27.16–33.77] |

99.55 (2,639/2,651) [99.29–99.80] |

94.98 (227/239) [92.21–97.75] |

83.59 (2,639/3,157) [82.30–84.88] |

0.6501 [0.6335–0.6667] |

| K74.69 | Other cirrhosis of liver | 29.26 (218/745) [25.99–32.53] |

99.40 (2,635/2,651) [99.10–99.69] |

93.16 (218/234) [89.93–96.4] |

83.33 (2,635/3,162) [82.03–84.63] |

0.6433 [0.6269–0.6597] |

| K70.30 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver without ascites | 7.25 (54/745) [5.39–9.11] |

100 (2,651/2,651) [99.86–100] |

100 (54/54) [93.40–100] |

79.32 (2,651/3,342) [77.95–80.70] |

0.5362 [0.5269–0.5456] |

| K70.31 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver with ascites | 8.05 (60/745) [6.10–10.01] |

100 (2,651/2,651) [99.86–100] |

100 (60/60) [94.04–100] |

79.47 (2,651/3,336) [78.10–80.84] |

0.5403 [0.5305–0.5501] |

| K71.7 | Toxic liver disease with fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver | 0.27 (2/745) [0.03–0.97] |

100 (2,651/2,651) [99.86–100] |

100 (2/2) [15.81–100] |

78.11 (2,651/3,394) [76.72–79.5] |

0.5013 [0.4995–0.5032] |

| Any code(s) | Any of the above | 60.00 (447/745) [56.48–63.52] |

97.77 (2,592/2,651) [97.21–98.34] |

88.34 (447/506) [85.54–91.14] |

89.69 (2,592/2,890) [88.58–90.8] |

0.7889 [0.7711–0.8067] |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the presence of any ICD-10 code.

The secondary validation cohort included 1,560 patients who were seen at any general or subspecialty clinics (not limited to gastroenterology of liver clinics) at our medical center. The mean age of this cohort was 59.8 ± 12.5 years, and slightly more than half (59.2%) were male (Table 3). The cohort was 40.1% non-Hispanic white, 22.0% Hispanic/Latino, 16.2% Asian, 3.1% non-Hispanic black, and 18.6% other/unknown. We found that the PPVs for ICD-10 codes in this general cohort were notably lower (55.53–66.76%) than those from the main cohort who all had a known chronic liver disease (Table 4).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients in secondary validation (n = 1,560)

| Age on January 10, 2015, mean ± SD, years | 59.80±12.51 |

| Male, n (%) | 924 (59.23) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 626 (40.13) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 343 (21.99) |

| Asian | 252 (16.15) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 49 (3.14) |

| Other/unknown | 290 (18.59) |

Table 4.

Secondary validation of PPV in general population (n = 1,560)

| Code | PPV, % (n) [95% CI] |

|---|---|

| K74.60 | 62.11 (718/1,156) [59.31–64.91] |

| K76.6 | 57.62 (348/604) [53.67–61.56] |

| K74.69 | 55.53 (241/434) [50.85–60.21] |

| K70.30 | 66.76 (239/358) [61.88–71.64] |

| K70.31 | 63.27 (186/294) [57.75–68.78] |

| K71.7 | 55.56 (5/9) [21.20–86.30] |

| Any code(s) | 60.77 (948/1,560) [58.35–63.19] |

PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion/Conclusion

In our study, we found that the PPVs for the individual ICD-10 codes included in this study were high in the cohort of patients with chronic liver disease (88.41–100%) but noticeably lower in the more general population (55.53–66.76%). This is consistent with the fact that PPV tends to increase with increased disease prevalence [6].

Mapakshi et al. [5] found consistently high PPVs (approximately 93%) of the ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis and its complications but did not report other important statistics such as sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and AUROC. Furthermore, the results from this VA cohort may not be generalizable to other care settings, as the VA population is disproportionately male and white and has higher liver disease prevalence [5]. By using a large patient population pulled from a university medical center and several community-based subspecialty and primary clinics, our results are more representative of the non-VA population. Our findings were also consistent with results for AUROCs with individual ICD-9 codes (ranging 0.46–0.68) by Nehra et al. [3].

We also found that the AUROC, a quantitative measure of overall diagnostic performance, for the presence of any one among the selected codes was higher (0.79) than that of any individual code alone (0.50–0.65). This suggests that more research should be done investigating the efficacy of ICD-10 code combinations, as has been done with the ICD-9 system [3]. It may also be useful to incorporate other noninvasive, serum-based fibrosis indices such as FIB-4 in the ICD-10 code diagnostic algorithm for cirrhosis [7], as there are newer databases that contain a limited set of laboratory data for their patients.

It is important to note that we only analyzed a small fraction of the ICD-10 codes that can be used to identify cirrhosis. We chose to focus our analysis on the 5 most commonly used ICD-10 codes with descriptions that specifically mention cirrhosis (K74.60, K74.69, K70.30, K70.31, and K71.7) and the code for portal hypertension (K76.6) because it was one of the most frequently appearing codes in our cohort and is strongly correlated with cirrhosis.

In addition, since alcohol is a common cause or cofactor for liver disease, we chose to include codes for alcoholic liver disease in our analysis despite the fact that our patient population was identified from databases of patients with chronic liver disease due to viral hepatitis and NAFLD. Codes for biliary cirrhosis were not tested since our database did not include patients with primary biliary cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis.

In summary, our results show that individual ICD-10 codes can identify cirrhosis in chronic liver disease cohorts with reasonable accuracy but are insufficient for studies of the general patient population. Therefore, we recommend conditioning ICD-10 code searches with a chronic liver disease diagnosis to optimize accuracy. Our findings also support further research to develop an algorithm using a combination of codes, as using any code from a set of several selected codes had better performance than individual codes.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. The IRB protocol number for this study is 13927.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

Study design: Nathan Ramrakhiani, Yee Hui Yeo, and Mindie H. Nguyen. Data collection: Nathan Ramrakhiani, Michael Le, An Le, Mayumi Maeda, and Mindie H. Nguyen. Data analysis: Nathan Ramrakhiani, An Le, and Mindie H. Nguyen. Drafting of the manuscript: Nathan Ramrakhiani and Mindie H. Nguyen. Data interpretation and review/revision of the manuscript: all authors. Study concept and supervision: Mindie H. Nguyen.

References

- 1.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49((8)):690–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12((1)):145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, Amarasingham R, Rockey DC, Singal AG. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47((5)):e50–4. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182688d2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer JR, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in veterans affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;27((3)):274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mapakshi S, Kramer JR, Richardson P, El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Positive predictive value of international classification of diseases, 10th revision, codes for cirrhosis and its related complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16((10)):1677–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vecchio T. Predictive value of a single diagnostic test in unselected populations. N Engl J Med. 1966;274((21)):1171–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196605262742104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim BK, Kim DY, Park JY, Ahn SH, Chon CY, Kim JK, et al. Validation of FIB-4 and comparison with other simple noninvasive indices for predicting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Liver Int. 2010;30((4)):546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]