Abstract

Objective

To evaluate progressive white matter (WM) degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Methods

Sixty-six patients with ALS and 43 healthy controls were enrolled in a prospective, longitudinal, multicenter study in the Canadian ALS Neuroimaging Consortium (CALSNIC). Participants underwent a harmonized neuroimaging protocol across 4 centers that included diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for assessment of WM integrity. Three visits were accompanied by clinical assessments of disability (ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised [ALSFRS-R]) and upper motor neuron (UMN) function. Voxel-wise whole-brain and quantitative tract-wise DTI assessments were done at baseline and longitudinally. Correction for site variance incorporated data from healthy controls and from healthy volunteers who underwent the DTI protocol at each center.

Results

Patients with ALS had a mean progressive decline in fractional anisotropy (FA) of the corticospinal tract (CST) and frontal lobes. Tract-wise analysis revealed reduced FA in the CST, corticopontine/corticorubral tract, and corticostriatal tract. CST FA correlated with UMN function, and frontal lobe FA correlated with the ALSFRS-R score. A progressive decline in CST FA correlated with a decline in the ALSFRS-R score and worsening UMN signs. Patients with fast vs slow progression had a greater reduction in FA of the CST and upper frontal lobe.

Conclusions

Progressive WM degeneration in ALS is most prominent in the CST and frontal lobes and, to a lesser degree, in the corticopontine/corticorubral tracts and corticostriatal pathways. With the use of a harmonized imaging protocol and incorporation of analytic methods to address site-related variances, this study is an important milestone toward developing DTI biomarkers for cerebral degeneration in ALS.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

White matter (WM) tract degeneration is a major pathologic component of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). There is consensus that biomarkers are urgently needed to serve several roles in clinical trials to improve the chances of identifying effective therapies.1 Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) provides a standardized, quantitative measure of tract pathology and has consistently revealed WM tract degeneration of the corticospinal tract (CST) in ALS,2 including sensitivity to disease progression.3 The encouraging results to date have been from single-center studies; however, generalization to the clinic and clinical trials requires similar demonstration in standardized multicenter initiatives. To that goal, we studied progressive cerebral degeneration in the Canadian ALS Neuroimaging Consortium (CALSNIC) prospectively using a protocol harmonized across sites. In addition to a whole-brain voxel-wise analysis, we used methodologic improvements that focused on cerebral WM tracts clinically relevant to ALS and its pathologic staging4 using a tract-of-interest approach.5,6

Methods

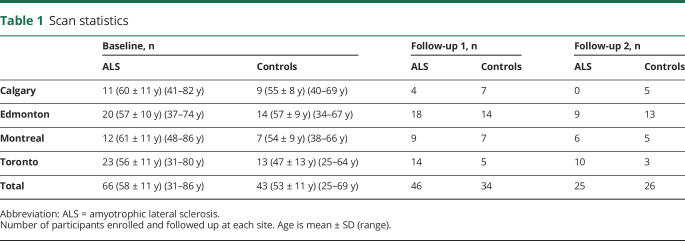

Sixty-six patients with ALS (age 59 ± 11 years) and 43 age-adapted healthy controls (age 53 ± 11 years) from 4 centers in CALSNIC contributed DTI scans to the study. The study schedule included MRI visits at 0, 4, and 8 months. Forty-six patients with ALS and 34 controls contributed at least 1 follow-up scan. The interval between the baseline and first and second follow visits was 133 ± 21 and 269 ± 36 days, respectively (table 1). Patients had a diagnosis of ALS according to El Escorial criteria at a designation of possible ALS or higher. Thus, all had upper motor neuron (UMN) and lower motor neuron signs together in at least 1 region. Participants were ineligible if they had a history of other neurologic or psychiatric disorders or met MRI exclusion criteria (e.g., claustrophobia, ferromagnetic implants).

Table 1.

Scan statistics

Patients with ALS had their disability quantified with the ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised (ALSFRS-R) questionnaire.7 Finger-tapping rate was assessed as a measure of UMN function,8 and a neurologic exam was performed that included elements that allowed calculation of a UMN score.9

Six healthy volunteers (“traveling heads,” separate from the healthy controls) were scanned twice at each center to assess intersite and intrasite reliability. Two volunteers were scanned a second time in 1 center with a time interval of 913 days to determine the stability of fractional anisotropy (FA) progression over a long duration in healthy participants.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the health research ethics boards of each participating site, and all participants gave written informed consent. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02405182).

MRI protocol

Participants underwent a multimodal MRI protocol that was harmonized across the 4 centers on clinical research scanners operating at 3T. DTI was conducted axially with full-brain coverage using a 2D echo planar imaging sequence: 70 slices, slice thickness 2.0 mm, voxel size 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm3, field of view 256 × 256 mm2, matrix 128 × 128, b0 images 5, diffusion gradient directions 30, and b value 1,000 s/mm2. Individual parameters for the 2 platforms used were as follows: (1) Siemens (University of Alberta [Siemens Prisma, Munich, Germany], McGill University [Siemens TimTrio]), repetition time 10,000 milliseconds, echo time 90 milliseconds; and (2) General Electric (University of Calgary [Discovery MR750, Fairfield, CT], University of Toronto [Discovery MR750, Fairfield, CT]), repetition time 9,000 milliseconds, echo time 85 milliseconds.

Data analysis

The DTI analysis software Tensor Imaging and Fiber Tracking was used for preprocessing and postprocessing.10,11 A graphic illustration of the data processing and analysis pipeline is provided in data available from Dryad (figure e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6).

Quality control

Before standardized preprocessing and postprocessing, DTI data underwent a detailed quality assurance protocol, eddy current correction, and motion correction.12 Data were transferred onto a 1-mm iso-grid for all further analysis.13 In the following, all voxel sizes refer to 1-mm3 voxels.

Preprocessing of longitudinal data

In a first step, follow-up DTI data and baseline DTI data for each participant with follow-up scans were aligned by fitting of the (b = 0) volumes to perform consequent stereotaxic Montreal Neurologic Institute transformation of baseline and follow-up data with the identical parameters. For this task, baseline and follow-up data were aligned to a template from the individual datasets of each participant (comparable to a halfway linear registration14) to avoid a bias of the baseline data.

Preprocessing: Stereotactic normalization and harmonization of FA maps from different protocols

In the second step, a nonlinear spatial normalization to the Montreal Neurologic Institute stereotaxic standard space15 was performed in an iterative manner with study-specific templates for the DTI data from all patients and controls.12,16,17 Fractional anisotropy (FA) maps of each dataset were calculated and were smoothed with a gaussian filter of 8-mm full width at half-maximum. The filter size of 8 mm (which is 4 times the acquired voxel size) provides a good balance between sensitivity and specificity.16 The FA maps of the controls for each scanning protocol were used to calculate the differences between scanners.18 Furthermore, the effect of age on FA maps12 was calculated and compared with previous results.19,20

Preprocessing: Fiber tracking and tract-wise FA statistics

Brain structures according to the ALS-associated staging system were defined by identifying specific tracts using a seed-to-target approach based on an averaged control DTI dataset (iso-grid 1 mm3, no smoothing).5,6,21,22 The FA threshold was set at 0.2.22 Fiber tracking was performed with a modified deterministic streamline tracking approach23: the eigenvector scalar product threshold was set at 0.9; the regions of interest for the seed regions had a radius of 5 mm; and the regions of interest for the target region had a radius of 10 mm. The following tracts of interest (TOIs) were thus defined, representing progressively greater WM tract involvement in ALS: the CST (stage 1), the corticorubral and corticopontine tracts (stage 2), the corticostriatal pathway (stage 3), and the proximal portion of the perforant path (stage 4). The optic tract where no involvement in ALS-associated neurodegeneration could be anticipated was used as a reference tract.5,6

Preprocessing: Harmonization of FA maps and pooling

FA maps of the different protocols were separately corrected for age according to the regression for age calculated from datasets of 43 controls. In a subsequent step, FA maps of patients with ALS and controls were center-wise harmonized by application of respective 3D correction matrices (linear first-order correction). The 3D correction matrices were calculated as linear corrections from the differences in the DTI scans of controls from each center.12,18 To control for consistency, 3D correction matrices were also calculated separately using the FA maps from the traveling heads. Averaged FA values for whole brain and relevant pathways are summarized for the 6 traveling heads for the 4 centers (data available from Dryad, figure e-2, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6).

Postprocessing: Whole brain–based voxel-wise statistics at the group level

Whole brain–based spatial statistics (WBSS)12,17 was performed for the calculation of cross-sectional differences of FA maps. Statistical comparisons of the 66 patients with ALS vs 43 controls were performed voxel-wise with the Student t test with the FA threshold set at 0.2.17,24 Statistical results were corrected for multiple comparisons according to the false discovery rate (FDR) algorithm at p < 0.05.25 Type 1 error was in addition reduced with the use of a spatial correction algorithm that eliminated isolated voxels or small clusters of voxels in the size range of the smoothing kernel, leading to a cluster size threshold of 256 voxels (256 mm3).

Postprocessing: Cross-sectional tract-wise comparison at the group level

For quantification of the directionality of the underlying tract structures, the technique of tract-wise FA statistics (TFAS)13 was applied. Age- and scanner-corrected FA maps from baseline scans of 66 patients with ALS and 43 controls were used to calculate mean FA values for the investigated tracts. Then, cross-sectional comparisons between patients with ALS and controls of mean FA values in the respective tract structures were performed with the Student t test. Bihemispheric FA values of tracts were averaged.

Postprocessing: Whole brain–based voxel-wise longitudinal comparison at the group level

WBSS was performed for the calculation of longitudinal differences in FA maps. Differences in FA values were linearly normalized to 1 day for each participant (patients with ALS and controls) to an identical time interval before statistical comparison according to the following: ΔFA/d = [FA(t1) – FA(t2)]/(t1-t2), where d is day and t1 and t2 are the dates of baseline and respective follow-up scan. Statistical comparisons of ΔFA/d for 46 patients with ALS vs 34 controls were performed voxel-wise by means of the Student t test. Statistical results were corrected for multiple comparisons by use of the FDR algorithm at p < 0.05, with additional cluster-size correction for type 1 error as described above.

Postprocessing: Longitudinal tract-wise comparison at the group level

FA maps from 46 patients with ALS and 34 controls who had received at least 1 follow-up scan were analyzed to calculate group-averaged differences in the staging-associated tracts. Data from patients with ALS with >1 follow-up scan were analyzed with regression analysis to obtain an average result of all follow-up scans. Rate of change was calculated for each participant (equation above) and then averaged for the ALS patient and control groups.

Postprocessing: Intraparticipant reliability

FA maps were tested on intraparticipant reliability for the traveling head participants. Because these 6 individuals each were scanned twice at the 4 centers, 24 pairs of scans were used to assess intraparticipant reliability in comparison to longitudinal ALS-related FA reductions in relevant tracts.

Postprocessing: Cross-sectional correlation of FA maps to clinical scores

FA maps from 66 patients with ALS were voxel-wise correlated with Pearson correlation to UMN, ALSFRS-R, and finger-tapping scores. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons with the FDR and cluster-size approach described above. The average FA values underlying the respective fiber tracts (as estimated by TFAS analysis) were also correlated using Pearson correlation to UMN, ALSFRS-R, and finger-tapping-scores.

Postprocessing: Correlation of longitudinal FA map alterations to alterations of clinical scores

The ΔFA/d values from 46 patients with ALS were voxel-wise correlated by Pearson correlation to longitudinal changes in UMN, ALSFRS-R, and finger-tapping scores. Results were corrected for multiple comparisons with the FDR and cluster-size approach described above. The ΔFA/d values underlying the respective fiber tracts (as estimated by TFAS analysis) were also correlated using Pearson correlation to longitudinal changes in UMN, ALSFRS-R, and finger-tapping scores.

Intraparticipant reliability

In this study, 3 approaches were used to estimate test-retest reliability. (1) Rescanning of healthy controls with 2 follow-up scans (identical to the protocol that the patients with ALS underwent) was done to confirm whether FA maps of controls are really stable or whether there are other contributing factors (e.g., scanner make) that influence the FA maps. Thus, to perform a mathematically correct and complete follow-up analysis, ALS-associated alterations are compared with the test-retest longitudinal alterations of controls (and not solely to the controls' baseline data, which are assumed to be stable). (2) The variability of FA maps of the 2 traveling heads with a long-time follow-up interval of 913 days was calculated. This does not require incorporating age-related effects that are negligible during this time period (compare with previous study19). (3) Intraparticipant reproducibility was assessed for the 6 traveling head participants, revealing 24 pairs of scans that can be used to calculate average FA variability of controls for all tract systems.

These data were used to model change of FA in controls and traveling heads over time and compared to the observed change in patients with ALS to derive interscan time interval estimates.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared at the request of qualified investigators.

Results

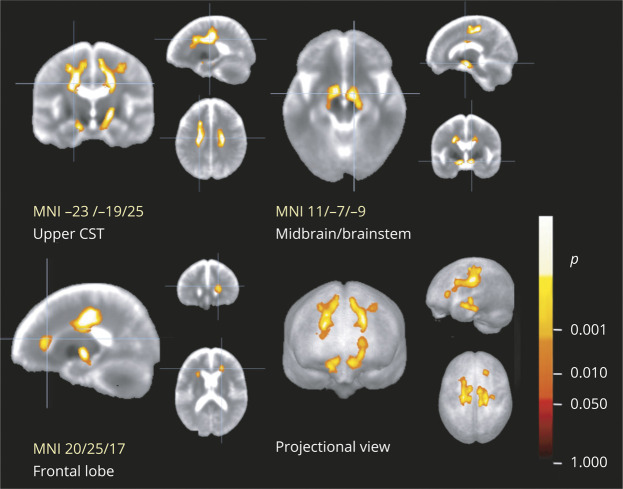

WBSS of cross-sectional differences at the group level

The group differences in FA of 66 patients with ALS vs 43 controls show significant alterations along the CST and in the frontal lobes (figure 1; details of the respective clusters are summarized in data available from Dryad, table e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). These findings were in accordance with the alterations in the ALS-related TOIs (see the “Differences in the tracts at the group level” section below). The WBSS results were compared for the 2 types of intercenter correction matrices that had been applied, i.e., 3D correction matrices that provided linear correction from the differences in the scans of controls from each center12,18 and 3D correction matrices that provided linear correction from the 6 traveling head participants. Results for the 2 types of correction matrices were almost identical, showing the same clusters for cross-sectional FA comparison between patients with ALS and controls.

Figure 1. Whole-brain-based spatial statistics for cross-sectional comparison of FA maps of patients with ALS vs controls.

This figure shows slice-wise and projectional views of cross-sectional differences in baseline fractional anisotropy (FA) in 66 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) vs 43 controls. Major significant alterations are localized along the corticospinal tract (CST) and in the frontal lobes. Representative slices demonstrate the main voxel clusters of results for the cluster along the CST (top left), in the brainstem (top right), and in the frontal lobe (bottom left). A projectional overlay reveals all clusters in a pseudo-3D view (bottom right). Significance level is coded according to the color bar. Corrections for multiple comparisons were made with the false discovery rate at p < 0.05 and a cluster-size approach. MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute.

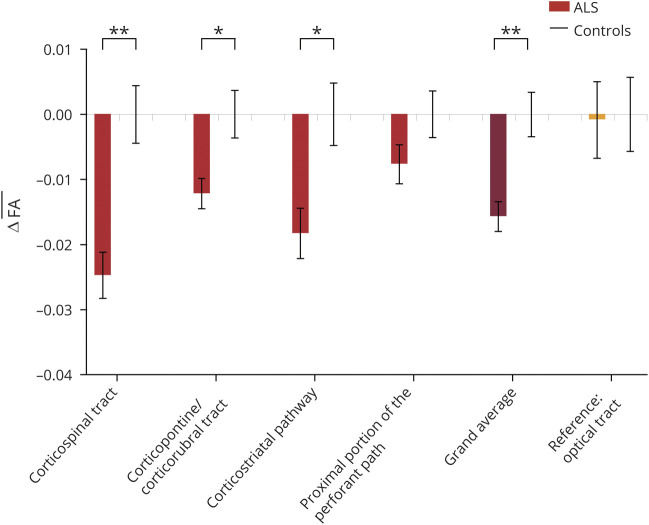

Differences in the tracts at the group level

Mean FA was reduced at baseline in patients with ALS. The analogous group differences in mean FA between patients with ALS and controls were significantly different for the TOIs (figure 2): the CST, the corticopontine and corticorubral tracts, the corticostriatal pathway, and the grand average of all tracts (p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). In addition, the proximal portion of the perforant path showed a trend toward reduced FA in patients with ALS. No significant differences were found in the reference tract. TFAS results were also compared for the 2 types of intercenter correction matrices. Cross-sectional FA comparisons for the 2 types of correction matrices were almost identical, showing the same significant alterations for cross-sectional FA comparison for tracts between patients with ALS and controls.

Figure 2. Cross-sectional comparison of FA values in ALS-related tracts by tract-wise FA statistics.

This figure shows the differences in mean fractional anisotropy (FA) values of different tracts at baseline in 66 patients with ALS compared to 43 controls. Tracts of interest were defined according to the sequential white matter tract involvement in agreement with the neuropathologic staging pattern in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): the corticospinal tract (CST; stage 1), corticorubral and corticopontine tracts (stage 2), corticostriatal pathway (stage 3), and proximal portion of the perforant path (stage 4). The optical tract was used as a reference tract. Mean FA was significantly reduced in patients with ALS in the CST, corticopontine/corticorubral tracts, corticostriatal pathway, and the grand average of all tracts, and the perforant path showed a trend toward reduced FA. Values are given as differences between mean FA values of controls and mean values of patients with ALS (Δmean FA); error bars are given as SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, corrected for multiple comparisons.

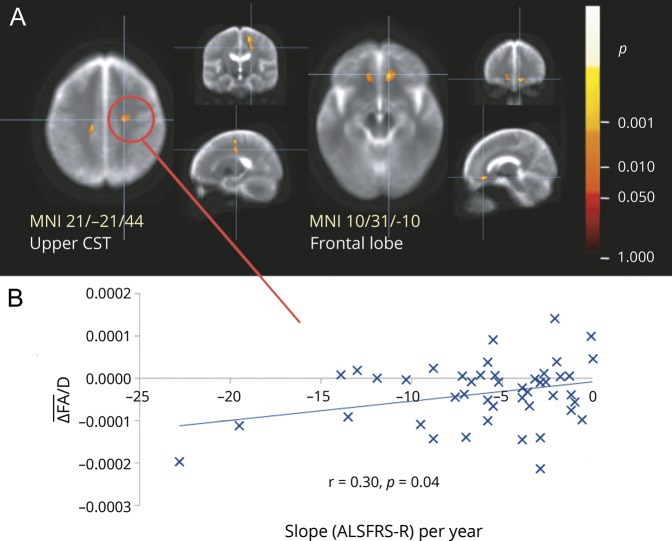

WBSS of longitudinal differences at the group level

For the WBSS analysis of mean ΔFA, group differences between 46 patients with ALS and 34 controls were significant along the CST and in the frontal lobes (figure 3 and data available from Dryad, table e-2, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). These significant longitudinal alterations were in agreement with the findings observed in the ALS-related TOIs (see below).

Figure 3. Whole-brain-based spatial statistics for the longitudinal comparison of FA maps in patients with ALS vs controls.

(A) Slice-wise representations of significant longitudinal alterations (decline) of fractional anisotropy (FA) in 46 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) vs 34 controls. Major significant alterations are localized along the upper corticospinal tract (top left) and in the frontal lobes (top right). Significance level is coded according to the color bar. Corrections for multiple comparisons were made with the false discovery rate at p < 0.05 and a cluster-size approach. (B) The correlation of ΔFA per day with the slope of ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised (ALSFRS-R) score in a results cluster localized in the upper corticospinal tract (CST). Mean (ΔFA)/d is the mean FA alteration per day. MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute.

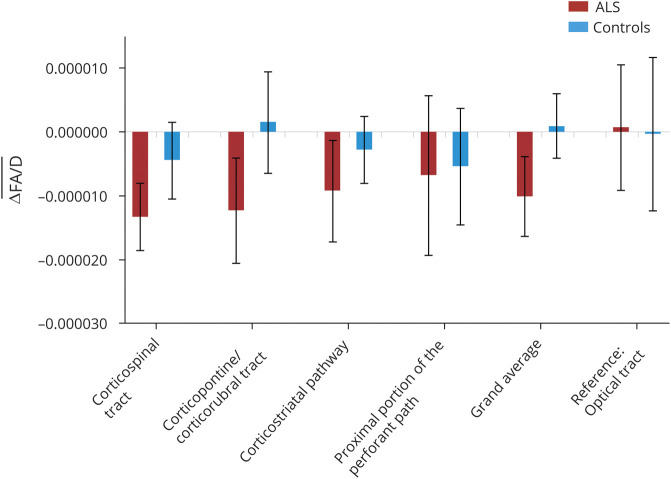

Longitudinal differences in the tracts at the group level

The analogous mean ΔFA differences between patients with ALS and controls in the TOIs showed trends toward negative values (i.e., reduced FA longitudinally from the baseline scan) for the CST, the corticopontine and corticorubral tracts, the corticostriatal pathway, the proximal portion of the perforant path, and the grand average of the 4 tracts (figure 4). No alterations were found for the reference path.

Figure 4. Longitudinal comparison of FA values in ALS-related tracts by tract-wise FA statistics.

This figure shows the longitudinal fractional anisotropy (FA) change (ΔFA/d is the slope of FA decrease in units per day) between baseline and 1 follow-up scan in 46 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) vs 34 controls. Tracts of interest were defined according to the sequential white matter tract involvement in agreement with the neuropathologic staging pattern in ALS: the corticospinal tract (stage 1), corticorubral and corticopontine tracts (stage 2), corticostriatal pathway (stage 3), and proximal portion of the perforant path (stage 4). The optical tract was used as a reference tract. Values are given as differences between mean difference FA values of ALS and mean difference values of controls; error bars are given as SEM.

Intraparticipant reliability

The minimum time for a given scan to detect ALS-associated alterations was set as the crossover point of the curve of FA progression in patients with ALS and the curve of the variability of controls; the latter is defined as the sum of the curve of FA progression of variability in controls, and the long time (913 days) controls variability (data available from Dryad, figure e-3A, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). The minimum time interval to observe FA reductions when considering all ALS-related tract systems was 110 days. The reliability of the tract in question affected the interval estimate (e.g., CST ≈20 days, proximal portion of the perforant path ≈200 days).

The intraparticipant average change in FA for the 6 traveling heads was smaller than the average FA reduction in patients with ALS over 200 days (data available from Dryad, figure e-3B, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). Thus, for studies at the group level, 110 days can be regarded as an appropriate time interval for follow-up scans in patients with ALS to demonstrate alterations in FA values that were averaged over all ALS-related tracts, and 200 days can be regarded as a time interval for follow-up scans in patients with ALS to demonstrate alterations (that are larger than intraparticipant alterations) in FA values in all separate ALS-related tracts.

Notably, the results concerning ΔFA/d refer to analyses at the group level, and any FA progression and the resulting calculation of rescan time intervals also refer to studies at the group level.

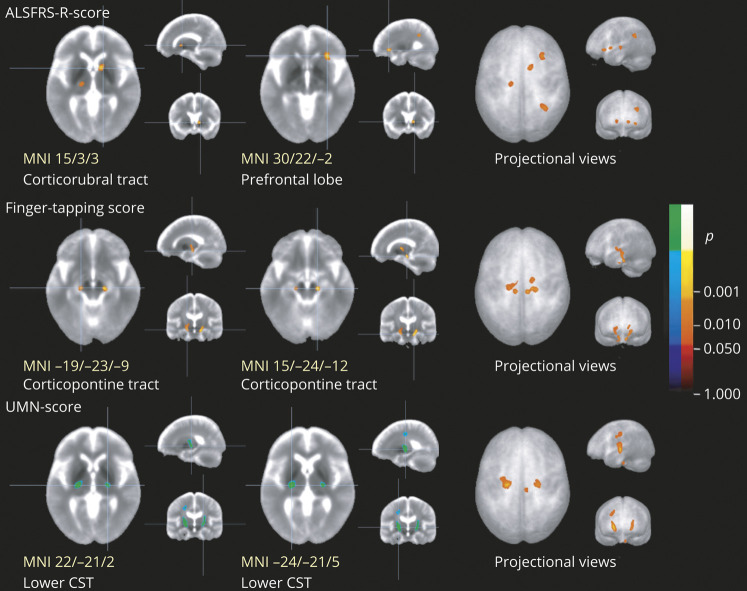

Cross-sectional correlation of voxel-wise FA values with clinical scores

Voxel-wise correlation of FA maps from 66 patients with ALS with their clinical scores showed significant negative correlations for the UMN score bilaterally in the lower CST, significant positive correlation clusters for the finger-tapping-score bilaterally in the lower corticopontine tract, and significant positive correlations for the ALSFRS-R-score along the corticorubral tract/frontal lobe (figure 5).

Figure 5. Cross-sectional voxel-wise correlation of FA maps of patients with ALS with clinical scores.

This figure shows slice-wise and projectional views of cross-sectional correlations of fractional anisotropy (FA) in the 66 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised (ALSFRS-R) score (top row), finger-tapping-score (center row), and upper motor neuron (UMN) score (bottom row). Main clusters are demonstrated at the level of the center (left and central column, with Montreal Neurologic Institute [MNI] coordinates of the peak voxel). ALSFRS-R score shows correlation with FA values in the corticorubral tract and in the prefrontal lobes; finger-tapping shows correlation with FA values in the corticopontine tract; and UMN score shows correlation with FA values in the lower corticospinal tract (CST). The right column is a projectional overlay of all clusters in a pseudo-3D view. Significance level is coded according to the color bar: hot colors represent positive correlation; cold colors represent negative correlation. Corrections for multiple comparisons were made with the false discovery rate at p < 0.05 and a cluster-size approach.

Correlations of FA values in tracts with clinical scores are summarized in table e-3 (available from Dryad, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). Negative significant correlation was found for the UMN score with the CST, coinciding with a previous study.9

Correlation of longitudinal FA map alterations with alterations in clinical scores

The changes in ΔFA values in the CST correlated significantly with the rate of change in the ALSFRS-R-score (slope) and UMN score, while no significant correlations for the other tracts were observed (data available from Dryad, table e-4, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). Correlations between ΔFA changes and rate of change of clinical score were observed in 1 cluster located in the CST (figure 3). The remaining clusters showed no such correlations.

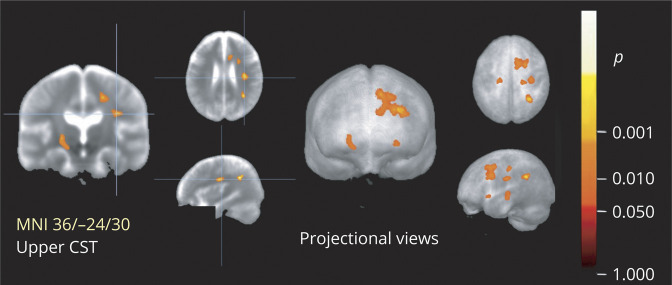

Fast progressors vs slow progressors

The patients with ALS were divided into fast and slow progressors on the basis of the rate of change in clinical score; i.e., 28 fast progressors with an ALSFRS-R score loss of >5 points per year were compared to the remaining 38 slow progressors. With the use of WBSS, clusters of significant FA reduction between fast and slow progressors were observed along the CST and in the upper frontal lobe (the projection area of the corticostriatal pathway and corticopontine tract; figure 6 and data available from Dryad, table e-5, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2bvq83bm6). No significant differences were found for slow vs fast progressors by a TFAS analysis.

Figure 6. Whole-brain-based spatial statistics for cross-sectional comparison of FA maps in fast vs slow ALS progressors.

This figure shows slice-wise and projectional views of the cross-sectional voxel-wise comparison of fractional anisotropy (FA) in 28 fast amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) progressors vs 38 slow ALS progressors. Major alterations are localized along the corticospinal tract (CST). Significance level is coded according to the color bar. Corrections for multiple comparisons were made with the false discovery rate at p < 0.05 and a cluster-size approach. MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute.

Discussion

This study represents the first prospective, multicenter effort using a harmonized DTI acquisition protocol to investigate cerebral neurodegeneration in ALS. Longitudinal assessment of ALS-specific WM tracts showed progressive decline in the FA of patients, which was associated with clinical progression of the disease. These progressive changes in FA were higher than intraparticipant variations in healthy controls, thus demonstrating their reliability. Intercenter standardization of data acquisition and analysis protocols is critical for the generalizability of potential MRI-based biomarkers in multicenter therapeutic trials.26 The current study marks an important step toward the development and validation of FA as a biomarker for cerebral WM degeneration in ALS.

Reduction of FA in the CST is a well-recognized and consistent DTI finding in ALS.27 Recent studies have recapitulated this finding with WBSS and TFAS analyses of large-scale DTI datasets; here, reduced FA is observed in the CST of patients with ALS, and additional FA decline occurs in the frontal and temporal regions of the brain.6,12 Similarly, we observed FA to be reduced in the CST and in regions of the frontal lobe in this novel dataset. In vivo DTI analysis has been shown to demonstrate a sequential spread of disease across defined WM tracts at the individual level,5 which mirrors the proposed postmortem stages of TAR DNA-binding protein-43 pathology in ALS.4,5 This DTI-based in vivo staging system has been shown to correlate with functional severity6 and cognitive decline28 in ALS. It is important to note that these studies were conducted in retrospective, heterogeneous cohorts and that no large-scale prospective multisite DTI studies currently exist in the ALS literature. In agreement with the previous findings, the largest reduction in FA in our prospective cohort was observed in tracts associated with stage 1 of the disease (CST), which theoretically would be present in all patients with ALS, and progressively smaller reductions were observed in tracts associated with later pathologic stages of the disease. These results from the TFAS analysis, particularly alterations in the corticopontine, corticorubral, and corticostriatal tracts, were recapitulated in whole-brain analysis—a useful validation.

Estimates for rescan time intervals over which longitudinal changes at the group level in WM integrity are measurable (i.e., alterations that were larger than intraparticipant alterations) resulted in 110 days for the grand average over all 4 ALS-related tracts and 200 days for all separate ALS-related WM tracts. These estimations might be improved by increasing the number of repeated control scans and by increasing the number of follow-up scans of patients with ALS.29

Longitudinal DTI studies in ALS have been conducted to monitor changes in the WM, and decline in FA of the CST over time has been reported in previous studies, mirroring the results of the present study,3,6,30,31 whereas others have reported relative stability in its value over time.32–34 Inconsistencies between studies can be ascribed to a number of factors, including differences in patient characteristics (symptom duration, extent of cerebral involvement at time of scanning) and differences in study methodology (imaging acquisition, analysis, interscan interval, extent of quality control measures). In this study, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were used. Harmonization of imaging protocols, rigorous quality control measures, and the use of correction for site-specific image variance with control and traveling head data were all incorporated to mitigate these methodologic issues. Furthermore, this study is strengthened with the use of longitudinal data from healthy controls. This was accomplished to ensure that progressive changes observed in patients with ALS are not a reflection of a healthy ageing process. The limitations of this study include a restricted sample size and the lack of cognitive and behavioral assessments of participants.

For biomarkers to be used in clinical trials as measures of therapeutic effects, they must show sensitivity to biological disease progression.33 Here, the longitudinal decline in FA of the CST in ALS correlated with functional decline and increased UMN burden over time. Because of the very heterogeneous phenotype in ALS and small sample sizes in previous studies, consistent clinical correlations with imaging metrics have remained elusive.34 A key feature of CALSNIC is the deep phenotypic characterization of study participants with multiple measures of UMN dysfunction (finger-tapping and UMN scores). The association of FA of the CST with clinical UMN burden underscores the internal validity of FA as a marker for UMN dysfunction in ALS. The correlation of the ALSFRS-R score with motor and extramotor regions suggests its nonspecificity to UMN dysfunction and the involvement of extramotor systems in severe forms of the disease.35

In addition to clinical examination features, disease progression rate is an aspect of the phenotypic heterogeneity in ALS and is a well-recognized predictor of survival in ALS.36 We found that patients with a fast progression rate had lower FA in the internal capsule and nonmotor (frontal and parietal) regions compared to those with a slower progression rate. Similar associations of disease progression rate have been observed with WM degeneration in the internal capsule37 and temporal regions of the brain.38,39 This suggests that there are indeed large, biological differences between these 2 subgroups of patients with ALS with relevance to clinical outcomes. Future clinical trials may benefit from predefined disease progression subgroups based on clinical or MRI-based characterization to improve the efficacy of novel therapeutics.

In this study, the variability of FA across multiple centers using a harmonized DTI protocol was incorporated into the analysis as a corrective measure. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such demonstration within the context of ALS biomarker research. Studies in the past have aimed to establish the intrasite and intersite reliability of DTI measures in healthy controls and patients with other neurodegenerative diseases.40–42 Harmonization of the acquisition protocol is crucial in ensuring that data collected from multiple centers are comparable in large multicenter studies. This study showed that the intraparticipant FA differences in healthy traveling controls for all tracts were smaller than the average FA reduction of patients with ALS in the relevant tracts. In multicenter studies, 3D correction matrices can be calculated as linear corrections from the differences in the scans of controls from each center12,18 or from traveling head controls. Both correction types were used and showed consistent results for cross-sectional comparisons either by WBSS or by TFAS; thus, either is reasonable to obtain valid 3D correction matrices.

This study demonstrates the feasibility and validity of using FA as a marker for cerebral degeneration in ALS in a prospective multicenter cohort. MRI measures are at the forefront of biomarker research and discovery in ALS because they are noninvasive and provide spatial sensitivity.33 The prospective multicenter performance of other potential MRI-based biomarkers requires similar clinical investigation and validation. Associations with detailed cognitive and behavioral assessments and pathologic validation would assist to further corroborate the in vivo MRI findings in ALS.

Glossary

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ALSFRS-R

ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised

- CALSNIC

Canadian ALS Neuroimaging Consortium

- CST

corticospinal tract

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- FDR

false discovery rate

- TFAS

tract-wise FA statistics

- TOI

tract of interest

- UMN

upper motor neuron

- WBSS

whole brain–based spatial statistics

- WM

white matter

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 327

Study funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the ALS Society of Canada, and the Brain Canada Foundation. Data management and quality control were facilitated by the Canadian Neuromuscular Disease Registry.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/Nhttps://n.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010235 for full disclosures.

References

- 1.van den Berg LH, Sorenson E, Gronseth G, et al. Revised Airlie House consensus guidelines for design and implementation of ALS clinical trials. Neurology 2019;92:e1610–e1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassubek J, Pagani M. Imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: MRI and PET. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32:740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Schuff N, Woolley SC, et al. Progression of white matter degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Toledo JB, et al. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013;74:20–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassubek J, Müller HP, Del Tredici K, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging analysis of sequential spreading of disease in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis confirms patterns of TDP-43 pathology. Brain 2014;137:1733–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassubek J, Müller HP, Del Tredici K, et al. Imaging the pathoanatomy of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in vivo: targeting a propagation-based biological marker. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018;89:374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J Neurol Sci 1999;169:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold G, Boone KB, Lu P, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of finger tapping test scores for the detection of suspect effort. Clin Neuropsychol 2005;19:105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo JH, Wang S, Melhem ER, et al. Linear associations between clinically assessed upper motor neuron disease and diffusion tensor imaging metrics in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One 2014;9:e105753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller HP, Unrath A, Ludolph AC, Kassubek J. Preservation of diffusion tensor properties during spatial normalization by use of tensor imaging and fibre tracking on a normal brain database. Phys Med Biol 2007;52:N99–N109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller HP, Kassubek J. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging in the analysis of neurodegenerative diseases. J Vis Exp 2013;77:e50427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller HP, Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, et al. A large-scale multicentre cerebral diffusion tensor imaging study in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller HP, Unrath A, Sperfeld AD, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractwise fractional anisotropy statistics: quantitative analysis in white matter pathology. Biomed Eng Online 2007;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menke RAL, Körner S, Filippini N, et al. Widespread grey matter pathology dominates the longitudinal cerebral MRI and clinical landscape of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2014;137:2546–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brett M, Johnsrude IS, Owen AM. The problem of functional localization in the human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002;3:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unrath A, Müller HP, Riecker A, et al. Whole brain-based analysis of regional white matter tract alterations in rare motor neuron diseases by diffusion tensor imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 2010;31:1727–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller HP, Unrath A, Huppertz HJ, et al. Neuroanatomical patterns of cerebral white matter involvement in different motor neuron diseases as studied by diffusion tensor imaging analysis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosskopf J, Müller HP, Dreyhaupt J, et al. Ex post facto assessment of diffusion tensor imaging metrics from different MRI protocols: preparing for multicentre studies in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener 2015;16:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salat DH, Tuch DS, Greve DN, et al. Age-related alterations in white matter microstructure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging 2005;26:1215–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim S, Han CE, Uhlhaas PJ, Kaiser M. Preferential detachment during human brain development: age- and sex-specific structural connectivity in diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data. Cereb Cortex 2015;25:1477–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassubek J, Müller HP. Computer-based magnetic resonance imaging as a tool in clinical diagnosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Rev Neurother 2016;16:295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller HP, Kassubek J. MRI-based mapping of cerebral propagation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurosci 2018;12:655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller HP, Unrath A, Riecker A, et al. Intersubject variability in the analysis of diffusion tensor images at the group level: fractional anisotropy mapping and fiber tracking techniques. Magn Reson Imaging 2009;27:324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunimatsu A, Aoki S, Masutani Y, et al. The optimal trackability threshold of fractional anisotropy for diffusion tensor tractography of the corticospinal tract. Magn Reson Med Sci 2004;3:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage 2002;15:870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menke RAL, Agosta F, Grosskreutz J, et al. Neuroimaging endpoints in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics 2017;14:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner MR, Agosta F, Bede P, et al. Neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biomark Med 2012;6:319–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lulé D, Böhm S, Müller HP, et al. Cognitive phenotypes of sequential staging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cortex 2018;101:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldaranov D, Khomenko A, Kobor I, et al. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging-based assessment of tract alterations: an application to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardenas-Blanco A, Machts J, Acosta-Cabronero J, et al. Structural and diffusion imaging versus clinical assessment to monitor amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin 2016;11:408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keil C, Prell T, Peschel T, et al. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC Neurosci 2012;13:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Albuquerque M, Branco LMT, Rezende TJR, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of cerebral and spinal cord damage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage Clin 2017;14:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner MR, Kiernan MC, Leigh PN, Talbot K. Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:94–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verstraete E, Turner MR, Grosskreutz J, et al. Mind the gap: the mismatch between clinical and imaging metrics in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener 2015;16:524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishaque A, Mah D, Seres P, et al. Evaluating the cerebral correlates of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1350–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:310–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menke RAL, Abraham I, Thiel CS, et al. Fractional anisotropy in the posterior limb of the internal capsule and prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verstraete E, Veldink JH, Hendrikse J, et al. Structural MRI reveals cortical thinning in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.d'Ambrosio A, Gallo A, Trojsi F, et al. Frontotemporal cortical thinning in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JY, Abdi H, Bakhadirov K, et al. A comprehensive reliability assessment of quantitative diffusion tensor tractography. Neuroimage 2012;60:1127–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole JH, Farmer RE, Rees EM, et al. Test-retest reliability of diffusion tensor imaging in Huntington's disease. PLoS Curr 2014;6:ecurrents.hd.f19ef63fff962f5cd9c0e88f4844f43b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vollmar C, O'Muircheartaigh J, Barker GJ, et al. Identical, but not the same: intra-site and inter-site reproducibility of fractional anisotropy measures on two 3.0T scanners. Neuroimage 2010;51:1384–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared at the request of qualified investigators.