Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection has affected close to 4 million people globally with more than 200,000 deaths and associated with various forms of morbidity and complications (Chan et al., 2020). The current virology tests are either time consuming or of low sensitivity, which has serious implications on affected patients and general population. There is an urgent need for diagnostic tests so that effective treatment can be instituted. Secretory IgA plays a crucial role in the immune defense of mucosal surfaces, the first point of entry of SARS-CoV-2. IgA-based serology tests targeting the SARS-CoV-2 specific Spike protein and nucleocapsid protein (NP) may thus represent an important diagnostic and therapeutic approach (Petherick, 2020, Okba et al., 2020).

Current evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection follows a similar antibody pattern and dynamic change as SARS-CoV and other viral infections. The Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) on Spike protein of the virus can recognize human receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) which is expressed by alveolar epithelial cells and facilitates the virus to enter host cells. Anti-RBD immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies are the first isotype to be generated against the novel antigen. They can be detected as early as day 3 post symptoms and typically class-switch to IgG. Alternatively, the class-switching can also result in the formation of IgA. IgA is mostly produced by plasma cells in the lamina propria adjacent to mucosal surfaces. This isotype switching does not change the RBD specificity of the antibody, but instead enables different biological effects through the tail region of the antibody.

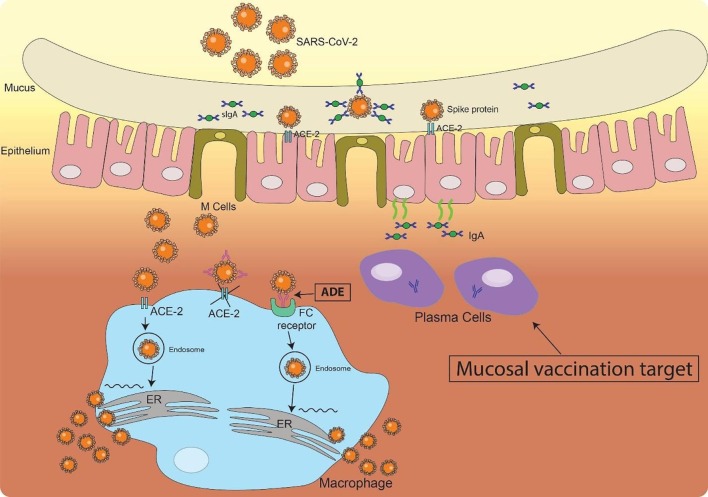

There is a lack of systematic study on IgA production in COVID-19 patients. Reported serology tests focus on IgM, IgG and total immunoglobulins although IgA is playing an important role in mucosal immunity. It is in fact the most important immunoglobulin to fight infectious pathogen in respiratory system and digestive system at the point of pathogen entry. As an immune barrier, secretory IgA can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 before they reach and bind the epithelial cells (Fig. 1 ). The amount of RBD specific IgA in the respiratory mucosa may thus serve as an indicator of host immune response, which can be directly measured in the saliva and tears and makes it possible to use IgA detection as an early diagnosis marker.

Fig. 1.

Mucosal Immunity in the nostril upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. Upon SARSE-CoV-2 infection in the nostril, both innate and adaptive immunity at the epithelium will be activated. Plasma cells, which can be the target of mucosal vaccine, produce IgA and secreted into the mucus where they meet and neutralize the invaded virus through binding to the Spike protein on the surface of SARS-Cov-2. Upon large dose of virus infection or a decreased secretory IgA response, virus will break through the barrier and infect the epithelia cells and other cells such as macrophages in the tissue through the interaction of RBD on Spike protein and ACE-2. Other neutralization antibodies can also bind to SARS-Cov-2 to prevent it from infecting other cells. However, the binding of non-neutralization antibodies may help SARS-Cov-2 entering the cells through Fc-Fc receptor interaction and cause antibody dependent enhancement (ADE).

Current strategies of immunotherapy are trying to achieve high serum levels of virus-specific immunoglobulins to neutralize the virus either through stimulating the host immune response (active immunization) or passively through transfusion with plasma from recovered patients. However, Zhao and colleagues reported that higher titer of total serum antibodies was associated with a more severe clinical classification (Zhao et al., 2019). Another report by To and colleagues didn’t find a correlation of serum antibody levels with clinical severity but found IgG developed faster peak anti-RBD responses in severe cases compared with mild cases (To et al., 2020). Similar findings have also been reported in SARS-CoV and MERS infection and this may be due to a detrimental T cell response with cytokine storm or antibody dependent enhancement (ADE) (Fig. 1).

IgA as a novel therapeutic antibody has gained an increasing amount of attention in recent years for mucosal infections. Unlike serum antibodies, secretory IgA may form polymers and has a unique structure which may not have the Fc receptor binding sites in some forms(Kumar et al., 2020) (Kumar 2020). Mucosal vaccine targeting SARS-CoV-2 RBD given via oral or nasal targets to induce secretion of IgA within the mucosa may be a therapeutic strategy for preventing COVID-19 development. While stimulating a systematic immune response through injections is an option, mucosal vaccination to induce a local protective immunity within the mucosa (where pathogenic infection is initiated) should be further explored despite potential challenges.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

E.K.-T. and Y.X.-C. are supported by grants from the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council STaR (E.K.-T), PD Clinical translational research, SPARK II (E.K.-T. and Y.X.-C).

References

- Chan C., Oey N.E., Tan E.K. Mental Health of Scientists in the time of COVID-19. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Arthur C.P., Ciferri C., Matsumoto M.L. Structure of the secretory immunoglobulin A core. Science. 2020;367(6481):1008–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okba N.M.A., Müller M.A., Li W., Wang C., GeurtsvanKessel C.H., Corman V.M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-specific antibody responses in coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(7) doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petherick A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K.K., Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV- 2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;(20):30196–30201. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. pii: S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. pii: ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]