Abstract

The existence of coronaviruses in bats is unknown until the recent discovery of bat-SARS-CoV in Chinese horseshoe bats and a novel group 1 coronavirus in other bat species. Among 309 bats of 13 species captured from 20 different locations in rural areas of Hong Kong over a 16-month period, coronaviruses were amplified from anal swabs of 37 (12%) bats by RT-PCR. Phylogenetic analysis of RNA-dependent-RNA-polymerase (pol) and helicase genes revealed six novel coronaviruses from six different bat species, in addition to the two previously described coronaviruses. Among the six novel coronaviruses, four were group 1 coronaviruses (bat-CoV HKU2 from Chinese horseshoe bat, bat-CoV HKU6 from rickett's big-footed bat, bat-CoV HKU7 from greater bent-winged bat and bat-CoV HKU8 from lesser bent-winged bat) and two were group 2 coronaviruses (bat-CoV HKU4 from lesser bamboo bats and bat-CoV HKU5 from Japanese pipistrelles). An astonishing diversity of coronaviruses was observed in bats.

Keywords: Bats, Coronavirus, Diversity

Introduction

Coronaviruses are found in a wide variety of animals in which they can cause respiratory, enteric, hepatic and neurological diseases of varying severity. Based on genotypic and serological characterization, coronaviruses were divided into three distinct groups (Lai and Cavanagh, 1997, Ziebuhr, 2004, Brian and Baric, 2005). As a result of the unique mechanism of viral replication, coronaviruses have a high frequency of recombination (Lai and Cavanagh, 1997). Their tendency for recombination and high mutation rates may allow them to adapt to new hosts and ecological niches.

The recent severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, the discovery of SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the identification of SARS-CoV-like viruses from Himalayan palm civets and a raccoon dog from wild live markets in mainland China have led to a boost in interests in discovery of novel coronaviruses in both humans and animals (Guan et al., 2003, Marra et al., 2003, Peiris et al., 2003, Rota et al., 2003, Woo et al., 2004a, Woo et al., 2004b). In 2004, a novel group 1 human coronavirus, human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) was reported independently by two groups (Fouchier et al., 2004, van der Hoek et al., 2004). In 2005, we described the discovery, complete genome sequence, clinical features and molecular epidemiology of another novel group 2 human coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1 (CoV-HKU1) (Woo et al., 2005a, Woo et al., 2005b, Woo et al., 2005c, Woo et al., 2005d). Recently, we have also described the discovery of SARS-CoV-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats and a novel group 1 coronavirus in large bent-winged bats, lesser bent-winged bats and Japanese long-winged bats in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) (Lau et al., 2005, Poon et al., 2005). Others have also discovered the presence of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats in other provinces in China (Li et al., 2005). Based on these findings, we suspected that a previously unrecognized large diversity of coronaviruses is present in bats in our locality. To test this hypothesis, we carried out a territory-wide coronavirus surveillance study in bats in HKSAR.

In this article, we report the discovery of six different novel coronaviruses in 13 bats of six different species in HKSAR. The molecular epidemiology of the novel and previously reported coronaviruses in bats are also described.

Results

Bat surveillance and identification of novel coronaviruses

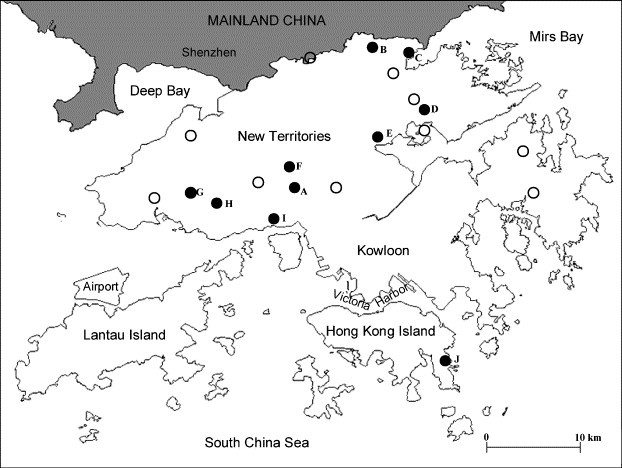

A total of 618 nasopharyngeal and anal swabs from 309 bats of 13 different species were obtained from rural areas in HKSAR (Fig. 1 , Table 1 ). RT-PCR for a 440-fragment in the pol genes of coronaviruses were positive in anal swabs from 37 (12%) of 309 bats. These 37 bats were of five genera and six species, distributed over 10 of the 20 different sampling sites (Table 1). None of the nasopharyngeal swabs was positive for coronaviruses.

Fig. 1.

Map of HKSAR showing locations of bat surveillance indicated by dots. Areas belonging to Shenzhen of mainland China are shaded. Solid dots represent the 10 locations with bats positive for coronaviruses. Location A is where CoV HKU4-1, bat-CoV HKU4-2 and bat-CoV HKU4-3 were found, location B is where bat-CoV HKU4-4 and bat-CoV HKU5-1 were found, and location C is where bat-CoV HKU5-2, bat-CoV HKU5-3 and bat-CoV HKU5-5 were found.

Table 1.

Bat species captured and associated coronaviruses in the present surveillance study

| Bats |

Coronaviruses | Sampling locations for the positive specimensa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific name | Common name | No. of bats tested | No. (%) of bats positive for coronaviruses | ||

| Cynopterus sphinx | Short-nosed fruit bat | 2 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Hipposideros armiger | Great round-leaf bat | 13 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Hipposideros pomona | Pomona roundleaf bat | 18 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Miniopterus magnater | Greater bent-winged bat | 51 | 1 (2) | Bat-CoV HKU7b | B |

| Miniopterus pusillus | Lesser bent-winged bat | 25 | 4 (16) | Bat-CoV HKU8b (n = 1)c | D (Bat-CoV HKU8-1) |

| Coronavirus previously reported (n = 3)c | E (Bat-CoV 61-1, 61-2 and 61-3) | ||||

| Myotis chinensis | Greater mouse-eared bat | 8 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Myotis ricketti | Rickett's big-footed bat | 23 | 1 (4) | Bat-CoV HKU6b | H |

| Nyctalus noctula | Noctule bat | 7 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Pipistrellus abramus | Japanese pipistrelle | 14 | 4 (29) | Bat-CoV HKU5b | B (Bat-CoV HKU5-1) C (Bat-CoV HKU5-2, HKU5-3 and HKU5-5) |

| Rhinolophus affinus | Intermediate horseshoe bat | 7 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Rhinolophus sinicus | Chinese horseshoe bat | 118 | 23 (19) | Bat-CoV HKU2b (n = 2)c | D (Bat-CoV HKU2-1) J (Bat-CoV HKU2-2) |

| Bat-SARS-CoV (n = 21)c | F, H, I (Bat-SARS-CoV HKU3) | ||||

| Rousettus lechenaulti | Leschenault's rousette | 2 | 0 (0) | – | |

| Tylonycteris pachypus | Lesser bamboo bat | 21 | 4 (19) | Bat-CoV HKU4b | A (Bat-CoV HKU4-1, HKU4-2 and HKU4-3) B (Bat-CoV HKU4-4) |

The sampling locations are those depicted in Fig. 1.

Novel coronaviruses described in the present study.

No. of bats positive for this coronavirus species.

Viral culture

No cytopathic effect was observed in any of the cell lines inoculated with bat specimens. Quantitative RT-PCR using the culture supernatants and cell lysates for monitoring the presence of viral replication also showed negative results.

Phylogenetic and other in silico analysis of pol and helicase genes of coronaviruses

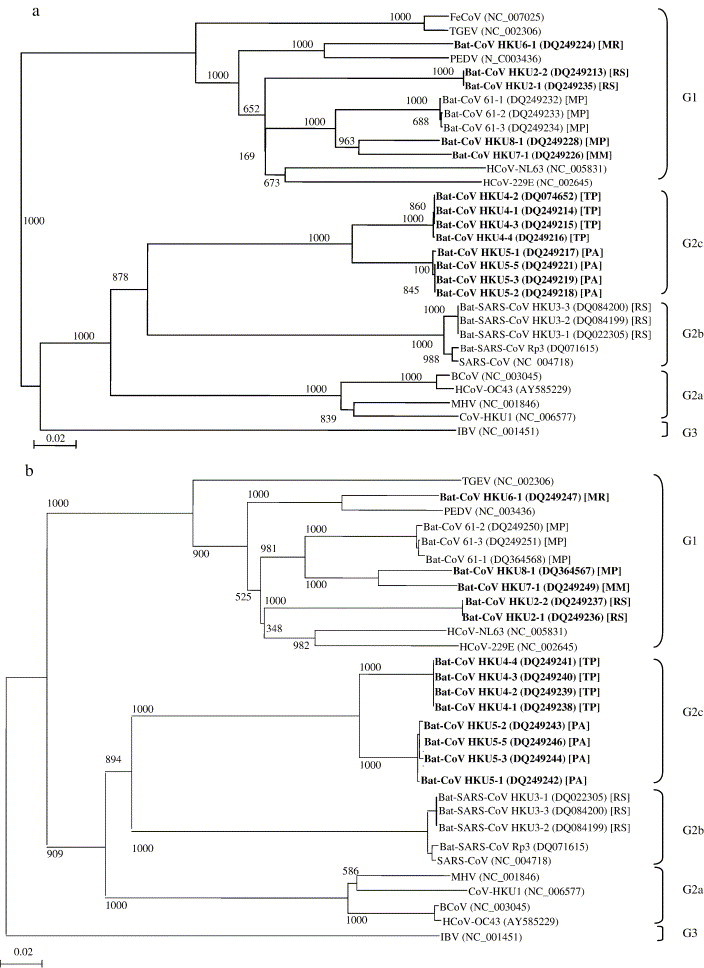

The complete pol and helicase genes of the coronaviruses from the bats were amplified and sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis of both genes revealed the presence of eight different coronaviruses (Table 1, Fig. 2 ). The bat-SARS-CoV that we described recently was present in anal swabs of 21 Chinese horseshoe bats (Lau et al., 2005). Another coronavirus that we described previously (Poon et al., 2005) was detected in anal swabs of three lesser bent-winged bats (bat-CoV strains 61-1, 61-2 and 61-3).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic trees of Pol (2a) and helicase (2b) showing the relationship of the novel bat coronaviruses to known coronaviruses. The trees were inferred from amino acid sequence data (949 amino acid positions for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and 609 amino acid positions for helicase) by the neighbor-joining method. Numbers at nodes indicated levels of bootstrap support calculated from 1000 trees. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 50 amino acids. Only three of the 21 strains of bat-SARS-CoV are shown. GenBank accession numbers are in brackets and names of bats from which the coronaviruses were recovered are in square brackets. The 13 strains of the six novel coronaviruses in bats are in bold. HCoV-229E, human coronavirus 229E; PEDV, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus; TGEV, porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus; FeCoV, feline coronavirus; HCoV-NL63, human coronavirus NL63; HCoV-OC43, human coronavirus OC43; MHV, murine hepatitis virus; BCoV, bovine coronavirus; CoV-HKU1, coronavirus HKU1; SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus; bat-SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus-like virus found in bats; IBV, infectious bronchitis virus; MR, Myotis ricketti; RS, Rhinolophus sinicus; MP, Miniopterus pusillus; MM, Miniopterus magnater; TP, Tylonycteris pachypus; PA, Pipistrellus abramus.

In addition to these two known coronaviruses, six novel coronaviruses were identified from 13 bats of six different species. They include a novel coronavirus in two Chinese horseshoe bats, a novel coronavirus in four lesser bamboo bats, a novel coronavirus in four Japanese pipistrelles, a novel coronavirus in a rickett's big-footed bat, a novel coronavirus in a greater bent-winged bat, and a novel coronavirus in a lesser bent-winged bat. These six novel coronaviruses were named as bat coronaviruses HKU2, HKU4, HKU5, HKU6, HKU7 and HKU8 (bat-CoV HKU2, bat-CoV HKU4, bat-CoV HKU5, bat-CoV HKU6, bat-CoV HKU7 and bat-CoV HKU8) respectively. Phylogenetic analysis of both pol and helicase genes showed similar topologies and revealed that bat-CoV HKU2, bat-CoV HKU6, bat-CoV HKU7 and bat-CoV HKU8 are group 1 coronaviruses, whereas bat-CoV HKU4 and bat-CoV HKU5 are group 2 coronaviruses (Fig. 2, Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Comparison of G + C contents and amino acid identities among the RNA dependent RNA polymerases and helicases of the six novel coronaviruses in bats and those of other coronaviruses

| Coronavirusesa | G + C contents of coronaviruses | Features of the RNA dependent RNA polymerases/Helicases of the six novel bat coronaviruses |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G + C contents | Pairwise amino acid identity (%) |

|||||||

| Bat-CoV HKU2 | Bat-CoV HKU4 | Bat-CoV HKU5 | Bat-CoV HKU6 | Bat-CoV HKU7 | Bat-CoV HKU8 | |||

| Group 1 | ||||||||

| HCoV-229E | 0.38 | 0.38/0.39 | 81/81 | 58/62 | 57/62 | 78/78 | 80/81 | 74/82 |

| PEDV | 0.42 | 0.40/0.42 | 78/78 | 60/62 | 59/63 | 88/90 | 81/81 | 75/82 |

| TGEV | 0.38 | 0.37/0.38 | 75/77 | 59/61 | 59/61 | 75/75 | 75/73 | 70/74 |

| FeCoV | 0.38 | 0.38/− | 76/− | 60/− | 60/− | 75/− | 75/− | 76/− |

| HCoV-NL63 | 0.34 | 0.34/0.35 | 79/81 | 57/61 | 57/62 | 79/82 | 81/83 | 75/83 |

| Bat-CoV 61–3 | – | 0.39/0.39 | 75/81 | 63/64 | 60/64 | 75/82 | 79/86 | 79/87 |

| Bat-CoV HKU2 | – | 0.39/0.40 | – | 58/61 | 58/62 | 78/78 | 82/80 | 74/81 |

| Bat-CoV HKU6 | – | 0.39/0.39 | 78/78 | 59/63 | 59/63 | – | 82/80 | 76/81 |

| Bat-CoV HKU7 | – | 0.40/0.40 | 82/80 | 59/62 | 59/62 | 82/80 | – | 84/92 |

| Bat-CoV HKU8 | – | 0.40/0.42 | 74/81 | 56/61 | 56/62 | 76/81 | 84/92 | – |

| Group 2 | ||||||||

| CoV-HKU1 | 0.32 | 0.32/0.33 | 55/53 | 67/66 | 68/66 | 57/56 | 57/54 | 52/54 |

| HCoV-OC43 | 0.37 | 0.36/0.38 | 56/54 | 68/67 | 68/67 | 57/57 | 56/55 | 53/55 |

| MHV | 0.42 | 0.39/0.39 | 56/55 | 68/67 | 68/67 | 57/57 | 57/56 | 53/55 |

| BCoV | 0.37 | 0.36/0.38 | 56/54 | 68/67 | 68/67 | 58/57 | 57/56 | 53/55 |

| SARS-CoV | 0.41 | 0.39/0.41 | 59/61 | 71/70 | 71/71 | 60/61 | 58/60 | 55/61 |

| Bat-SARS-CoV HKU3 (Lau et al., 2005) | 0.41 | 0.40/0.40 | 59/61 | 71/70 | 71/71 | 60/61 | 58/60 | 59/61 |

| Bat-SARS-CoV (Li et al., 2005) | 0.41 | 0.40/0.41 | 59/61 | 71/70 | 71/71 | 60/61 | 58/60 | 59/61 |

| Bat-CoV HKU4 | – | 0.37/0.38 | 58/61 | – | 92/93 | 59/63 | 59/62 | 56/61 |

| Bat-CoV HKU5 | – | 0.41/0.44 | 58/62 | 92/93 | – | 59/63 | 59/62 | 56/62 |

| Group 3 | ||||||||

| IBV | 0.38 | 0.38/0.37 | 57/55 | 60/57 | 59/58 | 56/57 | 57/55 | 54/56 |

HCoV-229E, human coronavirus 229E; PEDV, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus; TGEV, porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus; FeCoV, feline coronavirus; HCoV-NL63, human coronavirus NL63; HCoV-OC43, human coronavirus OC43; MHV, murine hepatitis virus; BCoV, bovine coronavirus; CoV-HKU1, coronavirus HKU1; SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus; bat-SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus-like virus found in bats; IBV, infectious bronchitis virus.

For the coronaviruses with complete genome sequences available, the G + C contents of the genomes concurred with the G + C contents of the pol and helicase genes of the corresponding coronavirus (Table 2). The G + C contents of the six novel coronaviruses were 0.39, 0.37, 0.41, 0.39, 0.40 and 0.40 for pol genes and 0.40, 0.38, 0.44, 0.39, 0.40 and 0.42 for helicase genes respectively.

Nucleotide polymorphisms in Bat-CoV HKU2, Bat-CoV HKU4 and Bat-CoV HKU5

Both strains of bat-CoV HKU2 possessed the same nucleotide sequence for pol and helicase genes. Of the four strains of bat-CoV HKU4, bat-CoV HKU4-1, bat-CoV HKU4-2 and bat-CoV HKU4-3 possessed the same nucleotide sequence in their pol genes, whereas bat-CoV HKU4-4 contained one non-synonymous substitution, at position 871 [TAT (Tyr) → CAT (His)], and two synonymous substitutions, at positions 384 and 2637, compared to the other three strains. All four strains possessed the same nucleotide sequence in their helicase genes. Of the four strains of bat-CoV-HKU5, bat-CoV HKU5-2, bat-CoV HKU5-3 and bat-CoV HKU5-5 possessed the same nucleotide sequence in their pol genes, whereas bat-CoV HKU5-1 contained two non-synonymous substitutions, at positions 2158 and 2160 [AAA (Lys) → GAG (Glu)] and 84 synonymous substitutions compared to the other three strains. In addition, two peaks (T and C) were consistently observed at nucleotide position 1279 of the pol gene in bat-CoV HKU5-1, suggesting the presence of quasi-species. As for the helicase genes, bat-CoV HKU5-2, bat-CoV HKU5-3 and bat-CoV HKU5-5 are also more closely related to each other than to bat-CoV HKU5-1. There were 62 synonymous substitutions between bat-CoV HKU5-1 and the other three strains. In addition, between bat-CoV HKU5-3 and the other three strains, there were two nucleotide substitutions, at positions 412 and 413, resulting in non-synonymous substitution [CTT (Leu) → ACT (Thr)], and one synonymous substitution at position 411 (ACA → ACT). Between bat-CoV HKU5-2 and the other three strains, there were two non-synonymous substitutions, at positions 815 [GCA (Ala) → GTA (Val)] and 1435 [AGT (Ser) → TGT (Cys)].

Discussion

An astonishing diversity of coronaviruses was observed in bats in HKSAR. In this study, among the 13 different species of bats captured, a total of eight coronaviruses were observed, with six being previously undescribed. This diversity of coronaviruses in bats could be related to the unique properties of this group of mammals. First, bats account for about 980 of the 4800 mammalian species recorded in the world. Although HKSAR is an urbanized, subtropical city, it has extensive natural areas with 52 different species of terrestrial mammals, with 40% of the species being bats. This diversity of bat species would potentially provide a large number of different cell types for different coronaviruses. Second, the ability to fly has given bats the opportunity to go almost anywhere, free from obstacles to land-based mammals. Bats have been found at altitudes of as high as 5000 m. This ability of bats would have allowed possible exchange of viruses and/or their genetic materials with different kinds of living organisms. Third, the different environmental pressures such as food, climates, shelters and predators would have provided different selective pressures on parasitisation of different coronaviruses in different species of bats. Fourth, the habit of roosting gives the opportunity to a large number of bats gather together. This would have also facilitated exchange of viruses among individual bats. Interestingly, the nucleotide sequences of the pol genes of bat-CoV HKU4-1, bat-CoV HKU4-2 and bat-CoV HKU4-3, collected at the same location (location A, Fig. 1), were the same, but different from that of bat-CoV HKU4-4, collected at another location (location B, Fig. 1); and the nucleotide sequences of the pol and helicase genes of bat-CoV HKU5-2, bat-CoV HKU5-3 and bat-CoV HKU5-5, collected at the same location (location C, Fig. 1), were also more closely related to each other, than to those of bat-CoV HKU5-1, collected at another location (location B, Fig. 1). We speculate that this was due to circulation of closely related strains of coronaviruses among bats found at the same locations.

From the results of the present study, we speculate that coronaviruses found in bats are bat genus/species specific, although one bat genus/species may harbor more than one type of coronavirus. Previous studies have shown that coronaviruses are particularly host specific and coevolved with their hosts, although host-shifting has also been demonstrated (Jonassen et al., 2005, Liu et al., 2005, Lai, 1990, Sturman and Holmes, 1983, Rest and Mindell, 2003). In this study, a huge variety of coronaviruses of groups 1 and 2, but not group 3, are found in bats in HKSAR, with the different coronaviruses being present in specific genus/species of bats. For SARS-CoV-like viruses, it was detected in Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus) in our locality (Lau et al., 2005), whereas in some other provinces in China, it was detected in some other species of horseshoe bats of the same genus (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Rhinolophus macrotis, Rhinolophus pearsoni and Rhinolophus pussilus) (Li et al., 2005). In addition to SARS-CoV-like viruses, one additional type of coronavirus (bat-CoV HKU2) was also detected in Rhinolophus sinicus in the present study. Similarly, a coronavirus that we described previously was detected in species of the genus Miniopterus, Miniopterus pusillus in the present study and Miniopterus magnater, Miniopterus pusillus and Miniopterus schreibersii in the previous study (Poon et al., 2005), and bat-CoV HKU8 was also found in Miniopterus pusillus. Furthermore, bat-CoV HKU4 was detected in lesser bamboo bat, bat-CoV HKU5 detected in Japanese pipistrelle, bat-CoV HKU6 detected in rickett's big-footed bat, and bat-CoV HKU7 detected in greater bent-winged bats. On the other hand, there is no strict association between the group that a bat coronavirus belongs to and the corresponding bat genus/species that the virus resides, as both groups 1 and 2 coronaviruses can be found in Chinese horseshoe bats. This absence of association between coronavirus group among groups 1 and 2 coronaviruses and the species of the host is also observed in human coronaviruses, as humans are hosts to both group 1 (HCoV229E and HCoV-NL63) and group 2 (HCoV229E, CoV-HKU1 and SARS-CoV) coronaviruses. A larger scale study expanded to different regions will confirm this phenomenon of host specificity. The availability of genomic and mitochondrial sequence data on the bat species that harbor the coronaviruses discovered in the present study will enable analysis of the phylogenetic relationship of these viruses in relation to the phylogeny of their hosts.

Strains of bat-CoV HKU4 and bat-CoV HKU5 may constitute a new subgroup, group 2c, of group 2 coronaviruses. Using molecular and serological approaches, coronaviruses are divided into three groups. When SARS-CoV was discovered and its genome completely sequenced, it was first proposed that SARS-CoV belonged to “a fourth group” of coronavirus (Marra et al., 2003, Rota et al., 2003). However, using multiple approaches, including both genomic and proteomic approaches, it was confirmed that SARS-CoV probably is an early split-off from the group 2 coronavirus lineage (Eickmann et al., 2003, Snijder et al., 2003). It is now the consensus that SARS-CoV and the SARS-CoV-like viruses belong to a subgroup, group 2b, of group 2 coronaviruses, whereas the other group 2 coronaviruses, including murine hepatitis virus, bovine coronavirus, HCoV-OC43, and the recently discovered CoV-HKU1, belong to group 2a. In the present study, phylogenetic analysis of two independent genes, pol and helicase genes, showed that the four strains of bat-CoV HKU4 and four strains of bat-CoV HKU5 were clustered and formed a unique lineage within group 2 coronaviruses, distinct from the group 2a and group 2b coronaviruses. The results were in line with those obtained from partial sequencing of about 200 nucleotides of the nucleocapsid genes of these two coronaviruses (unpublished data). Moreover, these two novel coronaviruses appear to be more closely related to group 2b than group 2a coronaviruses in both phylogenetic trees. Complete genome sequencing will confirm whether they represent a novel subgroup in group 2 coronaviruses, are more related to group 2a (e.g. presence of hemagglutinin esterase gene) or group 2b coronaviruses (e.g. presence of unique domain in nsp3), and have evolved as a result of recombination. Interestingly, the bootstrap values were particularly low at some nodes in the group 1 coronaviruses (Fig. 2), implying the phylogenetic relationships among some members of this group remained unclear. Unfortunately, the inherent difficulty in cultivating coronaviruses, the low viral load in the small volumes of samples from these small mammals, together with the huge differences in their nucleotide sequences from known coronaviruses, have caused major difficulties in achieving complete genome sequencing on the novel coronaviruses at this stage.

Materials and methods

Bat surveillance and sample collection

The study was approved by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation, HKSAR; and Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research, The University of Hong Kong. Three hundred and nine bats, of 13 species, were captured from 20 different locations in rural areas of HKSAR, including water tunnels, abandoned mines, sea caves and forested areas, over a 16-month period (April 2004–July 2005) (Fig. 1, Table 1). Nasopharyngeal and anal swabs were collected by a veterinary surgeon. Swabs were taken with sterile swabs and kept in viral transport medium at 4 °C before processing (Poon et al., 2005).

RNA extraction

Viral RNA was extracted from the nasopharyngeal and anal swabs using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA pellet was resuspended in 10 μl of DNase-free, RNase-free double-distilled water and was used as the template for RT-PCR.

RT-PCR of pol gene of coronaviruses using conserved primers and DNA sequencing

Coronavirus screening was performed by amplifying a 440-bp fragment of the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (pol) gene of coronaviruses using conserved primers (5′-GGTTGGGACTATCCTAAGTGTGA-3′ and 5′-CCATCATCAGATAGAATCATCATA-3′) designed by multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of available pol genes of known coronaviruses (Woo et al., 2005c). Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained cDNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 0.01% gelatin), 200 μM of each dNTPs and 1.0 U Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). The mixtures were amplified in 40 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 48 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min in an automated thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Gouda, The Netherlands). Standard precautions were taken to avoid PCR contamination and no false-positive was observed in negative controls.

The PCR products were gel-purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). Both strands of the PCR products were sequenced twice with an ABI Prism 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), using the two PCR primers. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with known sequences of the pol genes of coronaviruses in the GenBank database.

Viral culture

One to two samples of each novel coronavirus were cultured on LLC-Mk2 (rhesus monkey kidney), MRC-5 (human lung fibroblast), FRhK-4 (rhesus monkey kidney), Huh-7.5 (human hepatoma), Vero E6 (African green monkey kidney), and HRT-18 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) cells.

RT-PCR and sequencing of the complete pol and helicase genes of coronaviruses in bats

The complete pol and helicase genes of the coronaviruses identified from bats were amplified and sequenced using different sets of degenerate primers designed by multiple alignment of the pol and helicase genes of the various groups of coronaviruses and additional primers designed from the results of the first and subsequent rounds of sequencing. Detailed primer sequences will be provided on request. Sequences were assembled and manually edited to produce the final sequences of the pol and helicase genes. The nucleotide and the deduced amino acid sequences of the pol and helicase genes were compared to those of other coronaviruses. Phylogenetic tree construction was performed by using the neighbor-joining method with GrowTree software (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences of the six novel coronaviruses identified from 13 bats in the present study have been lodged within the GenBank sequence database under accession numbers DQ249213–DQ249219DQ249213DQ249214DQ249215DQ249216DQ249217DQ249218DQ249219, DQ249221, DQ249224, DQ249226, DQ249228, DQ249235 and DQ074652 for pol genes and DQ249236–DQ249244DQ249236DQ249237DQ249238DQ249239DQ249240DQ249241DQ249242DQ249243DQ249244, DQ249246, DQ249247, DQ249249 and DQ364567 for helicase genes respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor York Y. N. Chow, Secretary of Health, Welfare and Food, HKSAR, The Peoples' Republic of China; Thomas C. Y. Chan, Chik-Chuen Lay and Ping-Man So [HKSAR Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Conservation (AFCD)]; and Hong Kong Police Force for facilitation and support; Chung-Tong Shek and Cynthia S. M. Chan from AFCD for their excellent technical assistance; Dr. King-Shun Lo (Laboratory Animal Unit) and Dr. Cassius Chan for collection of animal specimens. This work is partly supported by the Research Grant Council Grant; University Development Fund, The University of Hong Kong; The Tung Wah Group of Hospitals' Fund for Research in Infectious Diseases; and the HKSAR Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Diseases of the Health, Welfare and Food Bureau.

References

- Brian D.A., Baric R.S. Coronavirus genome structure and replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;287:1–30. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickmann M., Becker S., Klenk H.D., Doerr H.W., Stadler K., Censini S., Guidotti S., Masignani V., Scarselli M., Mora M., Donati C., Han J.H., Song H.C., Abrignani S., Covacci A., Rappuoli R. Phylogeny of the SARS coronavirus. Science. 2003;302:1504–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.302.5650.1504b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier R.A., Hartwig N.G., Bestebroer T.M., Niemever B., de Jong J.C., Simon J.H., Osterhaus A.D. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6212–6216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400762101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L., Luo S.W., Li P.H., Zhang L.J., Guan Y.J., Butt K.M., Wong K.L., Chan K.W., Lim W., Shortridge K.F., Yuen K.Y., Peiris J.S., Poon L.L. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen C.M., Kofstad T., Larsen I.L., Lovland A., Handeland K., Follestad A., Lillehaug A. Molecular identification and characterization of novel coronaviruses infecting graylag geese (Anser anser), feral pigeons (Columbia livia) and mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:1597–1607. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80927-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M. Coronavirus: organization, replication and expression of genome. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1990;44:303–3333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M., Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Li K.S., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Wong B.H., Wong S.S., Leung S.Y., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Shi Z., Yu M., Ren W., Smith C., Epstein J.H., Wang H., Crameri G., Hu Z., Zhang H., Zhang J., McEachern J., Field H., Daszak P., Eaton B.T., Zhang S., Wang L.F. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Chen J., Chen J., Kong X., Shao Y., Han Z., Feng L., Cai X., Gu S., Liu M. Isolation of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus from domestic peafowl (Pavo cristatus) and teal (Anas) J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:719–725. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y., Cloutier A., Coughlin S.M., Freeman D., Girn N., Griffith O.L., Leach S.R., Mayo M., McDonald H., Montgomery S.B., Pandoh P.K., Petrescu A.S., Robertson A.G., Schein J.E., Siddiqui A., Smailus D.E., Stott J.M., Yang G.S., Plummer F., Andonov A., Artsob H., Bastien N., Bernard K., Booth T.F., Bowness D., Czub M., Drebot M., Fernando L., Flick R., Garbutt M., Gray M., Grolla A., Jones S., Feldmann H., Meyers A., Kabani A., Li Y., Normand S., Stroher U., Tipples G.A., Tyler S., Vogrig R., Ward D., Watson B., Brunham R.C., Krajden M., Petric M., Skowronski D.M., Upton C., Roper R.L. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon L.L., Chu D.K., Chan K.H., Wong O.K., Ellis T.M., Leung Y.H., Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Suen K.Y., Yuen K.Y., Guan Y., Peiris J.S. Identification of a novel coronavirus in bats. J. Virol. 2005;79:2001–2009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2001-2009.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest J.S., Mindell D.P. SARS associated coronavirus has a recombinant polymerase and coronaviruses have a history of host-shifting. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2003;3:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.H., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., DeRisi J.L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D.D., Peret T.C., Burns C., Ksiazek T.G., Rollin P.E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen-Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Gunther S., Osterhaus A.D., Drosten C., Pallansch M.A., Anderson L.J., Bellini W.J. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Dobbe J.C., Thiel V., Ziebuhr J., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Rozanov M., Spaan W.J., Gorbalenya A.E. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman L.S., Holmes K.V. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1983;38:35–112. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek L., Pyrc K., Jebbink M.F., Vermeulen-Oost W., Berkhout R.J., Wolthers K.C., Wertheim-Van Dillen P.M., Kaandorp J., Spaargaren J., Berkhout B. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat. Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H., Wong B.H., Che X.Y., Tam V.K., Tam S.C., Cheng V.C., Hung I.F., Wong S.S., Zheng B.J., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y. Relative rates of non-pneumonic SARS coronavirus infection and SARS coronavirus pneumonia. Lancet. 2004;363:841–845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wong B.H., Tsoi H.W., Fung A.M., Chan K.H., Tam V.K., Peiris J.S., Yuen K.Y. Detection of specific antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:2306–2309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2306-2309.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Huang Y., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Yuen K.Y. In silico analysis of ORF1ab in coronavirus HKU1 genome reveals a unique putative cleavage site of coronavirus HKU1 3C-like protease. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;49:899–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Poon R.W., Chu C.M., Lee R.A., Luk W.K., Wong G.K., Wong B.H., Cheng V.C., Tang B.S., Wu A.K., Yung R.W., Chen H., Guan Y., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Clinical and molecular epidemiological features of coronavirus HKU1 associated community-acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:1898–1907. doi: 10.1086/497151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Chu C.M., Chan K.H., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y., Wong B.H., Poon R.W., Cai J.J., Luk W.K., Poon L.L., Wong S.S., Guan Y., Peiris J.S., Yuen K.Y. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J. Virol. 2005;79:884–895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Chan K.H., Yuen K.Y. Phylogenetic and recombination analysis of coronavirus HKU1, a novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia. Arch. Virol. 2005;150:2299–2311. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr J. Molecular biology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]