Highlights

-

•

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia has caused 355 confirmed cases on the Diamond Princess cruise ship as of February 16, 2020.

-

•

We estimated that the Maximum-Likelihood (ML) value of reproductive number (R0) was 2.28 for COVID-19 outbreak at the early stage on the ship.

-

•

If R0 value was reduced by 25% and 50%, the estimated total number of cumulative cases would be reduced from 1296 (1145–1452) to 874 (780–978) and 573 (512–644) as of February 26, 2020, respectively.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Mathematical model, Reproductive number, Epidemiology

Abstract

Backgrounds

Up to February 16, 2020, 355 cases have been confirmed as having COVID-19 infection on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. It is of crucial importance to estimate the reproductive number (R0) of the novel virus in the early stage of outbreak and make a prediction of daily new cases on the ship.

Method

We fitted the reported serial interval (mean and standard deviation) with a gamma distribution and applied “earlyR” package in R to estimate the R0 in the early stage of COVID-19 outbreak. We applied “projections” package in R to simulate the plausible cumulative epidemic trajectories and future daily incidence by fitting the data of existing daily incidence, a serial interval distribution, and the estimated R0 into a model based on the assumption that daily incidence obeys approximately Poisson distribution determined by daily infectiousness.

Results

The Maximum-Likelihood (ML) value of R0 was 2.28 for COVID-19 outbreak at the early stage on the ship. The median with 95% confidence interval (CI) of R0 values was 2.28 (2.06–2.52) estimated by the bootstrap resampling method. The probable number of new cases for the next ten days would gradually increase, and the estimated cumulative cases would reach 1514 (1384–1656) at the tenth day in the future. However, if R0 value was reduced by 25% and 50%, the estimated total number of cumulative cases would be reduced to 1081 (981–1177) and 758 (697–817), respectively.

Conclusion

The median with 95% CI of R0 of COVID-19 was about 2.28 (2.06–2.52) during the early stage experienced on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. The future daily incidence and probable outbreak size is largely dependent on the change of R0. Unless strict infection management and control are taken, our findings indicate the potential of COVID-19 to cause greater outbreak on the ship.

Introduction

A novel coronavirus (COVID-19), which originated from Wuhan, China, has spread to 25 countries worldwide. Up to February 16, 2020, the cumulative number of confirmed cases were 70548 in China (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2020) and 683 in other countries (World Health Organization, 2020). The whole world, especially China, has taken extraordinary measures to contain the outbreak of COVID-19, and the effects were already present.

Unfortunately, the Diamond Princess cruise ship, with 3711 people on board, was found to have the epidemic of the novel coronavirus. As reported, the COVID-19 was traced to a passenger from Hong Kong, who boarded the cruise ship in Yokohama on January 20, then disembarked in Hong Kong on January 25. He had a symptom of coughing before boarding and was diagnosed as COVID-19 infection on February 1 in Hong Kong. The first 10 cases were confirmed on February 4 after the ship arrived in Yokohama port. Therefore, the Diamond Princess with the people on board was mandated to quarantine off the coast of Japan for 14 days. Up to February 16, 2020, 355 cases have been identified as having COVID-19 infection on the ship (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, 2020).

Because human-to-human transmission of COVID-19 has been confirmed (Huang et al., 2020), and there is limited space and relative high population density on the ship, it is of crucial importance to evaluate the transmissibility of COVID-19, and to forecast the probable size of the epidemic on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in the future. Accordingly, in this study, we estimated the reproductive number (R0) of COVID-19 in the early stage of outbreak on the ship and made a prediction of daily new cases for the next ten days.

Methods

Definitions

A confirmed case of COVID-19 infection was defined as a case with a positive result for viral nucleic acid testing in respiratory specimens. Suspected case was defined as a case with symptoms of COVID-19 infection but not confirmed by viral nucleic acid testing. Serial interval was defined as the duration between symptom onset of the primary case and symptom onset of the secondary in a transmission chain. R0 was defined as the expected number of secondary cases that one primary case will generate in a susceptible population (Li et al., 2020).

Data source

All the data were captured from the official website (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, 2020) that reported the situation of COVID-19 infection in Japan. The data for model development were updated to February 16, 2020.

Model development and statistical analysis

To evaluate the transmissibility of COVID-19 on the ship, we applied the “earlyR” package to estimate the R0 in the early stage of outbreak (Jombart et al., 2017). Serial interval distribution is required for R0 estimation, and there was insufficient information about cluster cases for serial interval estimation. Therefore, we assumed the serial interval of COVID-19 on the ship was equal to that of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, with a mean of 7.5 days and a standard deviation of 3.4 days (Li et al., 2020). We fitted the value of serial interval (mean and standard deviation) with a gamma distribution, as previously described (Li et al., 2020). The “get_R” function with Maximum-Likelihood (ML) estimation was used to obtain the distribution of R0.

To derive other statistics for R0 distribution estimation, we used a bootstrap strategy with 1000 times resampling to get a large set of likely R0 values. We displayed these R0 values in histogram format and computed the median and interquantile range for these R0 values.

R package of “projections” was used for plausible epidemic trajectories simulation and future daily incidence prediction (Jombart et al., 2018). The simulation and prediction were generated by fitting the data of existing daily incidence, a serial interval distribution, and the estimated R0 into a model based on the assumption that daily incidence obeys approximately Poisson distribution determined by daily infectiousness, which was denoted as

was the vector of probability mass function (PMF) of serial interval distribution. was the real-time incidence at time (Jombart et al., 2018, Nouvellet et al., 2018). We computed the prediction of daily incidence for the next ten days using a bootstrap resampling method (1000 times). We also plotted the possible cumulative incidence range for the next ten days. All statistical analyses and model development were performed using R version 3.6.2.

Results

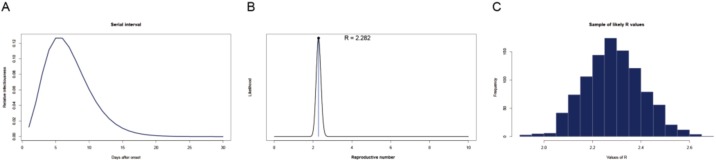

Serial interval distribution of COVID-19 is shown in Figure 1 A. Using the serial interval distribution described above, we estimated that the ML value of R0 was 2.28 for COVID-19 outbreak at the early stage on the ship (Figure 1B). With a bootstrap strategy, we obtained 1000 likely R0 values. The distribution of these R0 values was displayed as histogram plot in Figure 1C. The estimated median with 95% confidence interval (CI) of R0 values was 2.28 (2.06–2.52).

Figure 1.

The distribution of serial interval (A), the distribution of likely values of reproductive number (R0) with the Maximum-Likelihood (ML) estimation (B), a sample of 1000 likely R0 values using a bootstrap resampling method (C) for COVID-19 on Diamond Princess cruise ship.

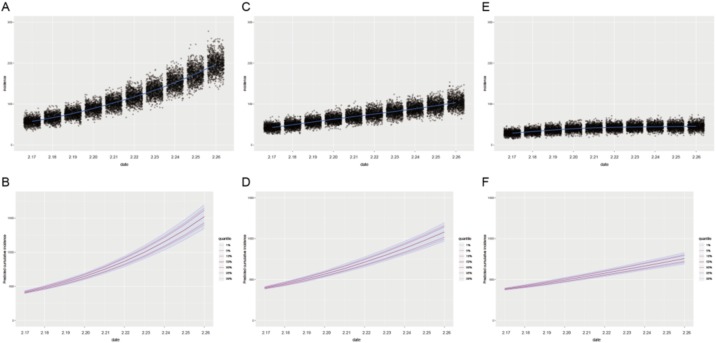

We then computed the probable number of new cases for the next ten days based on existing data and estimated R0. As shown in Figure 2 A, the daily median number with 95% confidence interval (CI) of new cases was 57 (42–75), 66 (49–84), 77 (59–96), 89 (68–111), 102 (81–125), 117 (93–142), 133 (107–164), 150 (123–184), 171 (138–208), 194 (156–235), respectively. We also simulated the range of cumulative number of cases for the next ten days, which is shown in Figure 2B. The daily cumulative number of cases with 95% CI was 413 (397–430), 478 (456–503), 555 (528–588), 645 (606–684), 747 (696–798), 863 (800–925), 996 (919–1071), 1148 (1055–1242), 1321 (1210–1437), 1514 (1384–1656), respectively.

Figure 2.

The epidemic trajectories of probable daily and cumulative cases for COVID-19 on Diamond Princess cruise ship February 17, 2020 and February 26, 2020. Panels (A) and (B) show the probable number of new and cumulative cases for the next ten days if the R0 value was unchanged, respectively. Panels (C) and (D) show the probable number of new and cumulative cases for the next ten days if R0 value was decreased by 0.25-fold, respectively. Panels (E) and (F) show the probable number of new and cumulative cases for the next ten days if the R0 value was decreased by 0.5-fold, respectively.

We considered that the crew had taken measures to control the spread of infection, which would reduce the value of R0. We assume that if R0 value was reduced by 25%, the corresponding median number with 95% CIs of new cases for the next ten days would be 43 (30–57), 49 (35–64), 56 (41–72), 63 (47–81), 69 (51–90), 75 (56–96), 83 (63–105), 89 (68–111), 96 (74–123), 104 (79–133) (Figure 2C). The total number of cumulative cases would be reduced to 1081 (981–1177) at the tenth day in the future (Figure 2D). If the R0 value was further reduced by 50%, the corresponding new cases for the next ten days would be 28 (19–41), 32 (21–45), 36 (25–50), 39 (27–54), 42 (29–55), 43 (30–57), 44 (31–59), 44 (31–59), 45 (31–61), 45 (32–62) (Figure 2E). The total number of cumulative cases would be reduced to 758 (697–817) at the tenth day in the future (Figure 2F).

Discussion

Using the existing data and the epidemic model incorporating these data, we provide an estimation of the R0 of COVID-19 during the early stage experienced on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. We estimated that distribution of R0 was about 2.28 (2.06–2.52), which had overlaps with a set of previously published estimates, ranging from 2.2 (95% CI, 1.4–3.9) to 3.58 (95%CI: 2.89–4.39) (Li et al., 2020, Zhao et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020), but lower than the reported estimate from a recent study with a large sample size, which suggested the R0 was 3.77 (95% CI 3.51–4.05). The wide range and the variability in R0 values reported by different studies indicate that precisely estimating R0 is quite challenging, because it is difficult to calculate the exact number of infected cases during an epidemic. Otherwise, the R0 value is affected by environmental circumstances, demography, statistical caliber, and modeling methodology (Delamater et al., 2019). In our study, the accuracy of estimated R0 is largely dependent on whether all the infected cases have been identified. According to the report from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, all the suspected cases and cases who had close contact with confirmed cases had received viral nucleic acid testing. Therefore, the proportion of unidentified cases is supposed to be low. In contrast, prior published studies were mainly focused on the estimation of R0 in Wuhan, China (Li et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020). These estimates of R0 may be biased because a large population of infected cases were not identified during the early phase of disease outbreak. Another attractive feature of investigating the R0 on the ship is that the total number of population on board is relatively fixed, which perfectly matches the premise of epidemic models when studying the transmissibility of COVID-19 (Yan, 2008). Moreover, compared with prior studies (Li et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020), the driving force of zoonotic infection was absent among the population on the ship. Therefore, the R0 in our study only reflected the human-to-human transmissibility of COVID-19, rather than a composite of zoonotic and human-level transmissibility. Our findings suggested that the R0 was still high although quarantine measures have been taken on the ship, indicating that other transmission routes may be neglected, such as aerosol transmission via the central air conditioning system or drainage systems. The latter was thought to be the cause of the SARS-CoV outbreak in a building in Hong Kong in 2003 (Anon, 2020). Otherwise, unidentified asymptomatic cases or cases within incubation may also cause continuous spread of the novel virus, which may also partially explain why R0 was still high at this stage.

We also made a prediction of daily incidence and the probable size of the outbreak for the next ten days. According to our analysis, the daily incidence and the size of outbreak are largely dependent on the value of R0. If the R0 value remained unchanged, the cumulative number of infected cases may reach 1514 at the tenth day, suggesting more than forty percent of the population would be infected. Fortunately, the crew has taken more stringent measures to control the spread of infection. As a result, the transmissibility is expected to be reduced in the coming days. If the R0 value is reduced by 50%, the infected cases will be reduced by about half. If the R0 value can further be reduced to less than 1, the number of infectious disease cases will gradually taper off and finally perish. Our data-driven analysis highlights the importance of controlling the transmissibility among population at this stage.

The current study has some limitations. First, because of the limited population number on board and the high infectiousness of COVID-19, with the rapid increase in number of infected cases, the proportion of susceptible population will be decreased rapidly. Therefore, our findings are constrained to a limited time frame and the result may be changed after a considerable number of cases were infected. Second, some confirmed cases were intentionally removed from the ship for treatment, and this measure would affect the natural process of disease transmission. If a considerable number of confirmed cases were removed, the computed R0 would be underestimated. Third, the prediction was based on the existing data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; a delay in case confirmation or reporting would result in an underestimation of R0.

Conclusion

We estimated that the median with 95% CI of R0 of COVID-19 was about 2.28 (2.06–2.52) during the early stage experienced on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. The future daily incidence and probable outbreak size is largely dependent on the change of R0. Our findings emphasize the importance of reducing R0 in controlling the outbreak size at this stage.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Funding source

None.

Ethical approval

Approval was not required.

Contributor Information

Zhaofen Lin, Email: linzhaofen@hotmail.com.

Dechang Chen, Email: chendechangsh@hotmail.com.

References

- Delamater P.L., Street E.J., Leslie T.F., Yang Y.T., Jacobsen K.H. Complexity of the basic reproduction number (R0) Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(1):1–4. doi: 10.3201/eid2501.171901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.L., Wang Y.M., Li X.S., Ren L.L., Zhao J.P., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [Accessed 24 January 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart Thibaut, Cori Anne, Nouvellet Pierre. 2017. earlyR: Estimation of transmissibility in the early stages of a disease outbreak. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=earlyR. [Accessed 6 December 2017] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart Thibaut, Nouvellet Pierre, Bhatia Sangeeta, Kamvar Zhian N. 2018. projections: Project future case incidence. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=projections. [Accessed 27 August 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X.H., Wu P., Wang X.Y., Zhou L., Tong Y.Q. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [Accessed 29 January 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . 2020. Identification of novel coronavirus infection on cruise ship in quarantine at Yokohama Port (report 8) Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_09425.html. [Accessed 16 February 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvellet P., Cori A., Garske T., Blake I.M., Dorigatti I., Hinsley W. A simple approach to measure transmissibility and forecast incidence. Epidemics. 2018;22:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2020. The latest situation of new coronavirus pneumonia. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202002/553ff43ca29d4fe88f3837d49d6b6ef1.shtml. [Accessed 16 February 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Anon . APNEWS; 2020. Virus cases in Hong Kong apartments recall SARS memories. Available from: https://apnews.com/2b93091de34ceb1b5ac9443be8abee4c. [Accessed 11 February 2020] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-19. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200213-sitrep-24-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=9a7406a4_4. [Accessed 16 February 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [Accessed 31 January 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Ping. Distribution theory, stochastic processes and infectious disease modelling. In: Brauer Fred, van den Driessche Pauline, Jianhong Wu., editors. Mathematical epidemiology. 2008. pp. 229–293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Lin Q.Y., Ran J.J., Musa S.S., Yang G.P., Wang W.M. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: a data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.050. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.050. [Accessed 30 January 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]