Abstract

This case series uses patient hospital data to summarize the clinical presentation and laboratory and imaging findings of 13 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV infection admitted to hospitals in Beijing in January 2020.

In December 2019, cases of pneumonia appeared in Wuhan, China. The etiology of these infections was a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV),1,2 possibly connected to zoonotic or environmental exposure from the seafood market in Wuhan. Human-to-human transmission has accounted for most of the infections, including among health care workers.3,4 The virus has spread to different parts of China and at least 26 other countries.1 A high number of men have been infected, and the reported mortality rate has been approximately 2%, which is lower than that reported from other coronavirus epidemics including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS; mortality rate, >40% in patients aged >60 years)5 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS; mortality rate, 30%).6 However, little is known about the clinical manifestations of 2019-nCoV in healthy populations or cases outside Wuhan. We report early clinical features of 13 patients with confirmed 2019-nCoV infection admitted to hospitals in Beijing.

Methods

Data were obtained from 3 hospitals in Beijing, China (Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, School of Medicine, Tsinghua University [8 patients], Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University [4 patients], and College of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Chinese PLA General Hospital [1 patient]). Patients were hospitalized from January 16, 2020, to January 29, 2020, with final follow-up for this report on February 4, 2020. Patients with possible 2019-nCoV were admitted and quarantined, and throat swab samples were collected and sent to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for detection of 2019-nCoV using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay.3 Chest radiography or computed tomography was performed. Data were obtained as part of standard care. Patients were transferred to a specialized hospital after diagnosis. This study was approved by the ethics commissions of the 3 hospitals, with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

The median age of the patients was 34 years (25th-75th percentile, 34-48 years); 2 patients were children (aged 2 years and 15 years), and 10 (77%) were male. Twelve patients either visited Wuhan, including a family (parents and son), or had family members (grandparents of the 2-year-old child) who visited Wuhan after the onset of the 2019-nCoV epidemic (mean stay, 2.5 days). One patient did not have any known contact with Wuhan.

Twelve patients reported fever (mean, 1.6 days) before hospitalization. Symptoms included cough (46.3%), upper airway congestion (61.5%), myalgia (23.1%), and headache (23.1%) (Table). No patient required respiratory support before being transferred to the specialty hospital after a mean of 2 days. The youngest patient (aged 2 years) had intermittent fever for 1 week and persistent cough for 13 days before 2019-nCoV diagnosis. Levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein were elevated, and numbers of lymphocytes were marginally elevated (Table).

Table. Clinical Presentation and Pertinent Laboratory Findings of Patient Population With 2019-nCoV (N = 13).

| Overall, Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (25th-75th percentile), y | 34 (34-48) |

| Febrile days | 1.58 (1.82) |

| Maximum temperature, °C | 38.4 (0.883) |

| Cough, No. (%) | 6 (46.2) |

| Days of cough | 8.33 (4.16) |

| Productive cough, No. (%) | 2 (15.4) |

| Rhinorrhea, No. (%) | 1 (7.7) |

| Myalgia, No. (%) | 3 (23.1) |

| Diarrhea, No. (%) | 1 (7.7) |

| Upper airway congestion, No. (%) | 8 (61.5) |

| Headache, No. (%) | 3 (23.1) |

| CRP, mg/L | 14.7 (10.2) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 147 (12.1) |

| Hematocrit, % | 43.2 (3.36) |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 199 (72.5) |

| WBCs, ×109/L | 5.83 (2.32) |

| Lymphocytes, % | 27.9 (7.10) |

| Absolute lymphocytes, ×109/L | 1.58 (0.653) |

| Neutrophils, % | 58.0 (18.3) |

| Absolute neutrophils, ×109/L | 3.67 (1.71) |

| Eosinophils, % | 0.677 (0.988) |

| Absolute eosinophils, ×109/L | 0.0454 (0.0724) |

| Basophils, % | 0.169 (0.103) |

| Absolute basophils, ×109/L | 0.00846 (0.00555) |

| Monocytes, % | 9.39 (3.28) |

| Absolute monocytes, ×109/L | 0.526 (0.208) |

| Procalcitonin, % | 0.187 (0.0633) |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; 2019-nCoV, 2019 novel coronavirus; WBC, white blood cell.

SI conversion factor: To convert CRP values to nmol/L, multiply by 9.524.

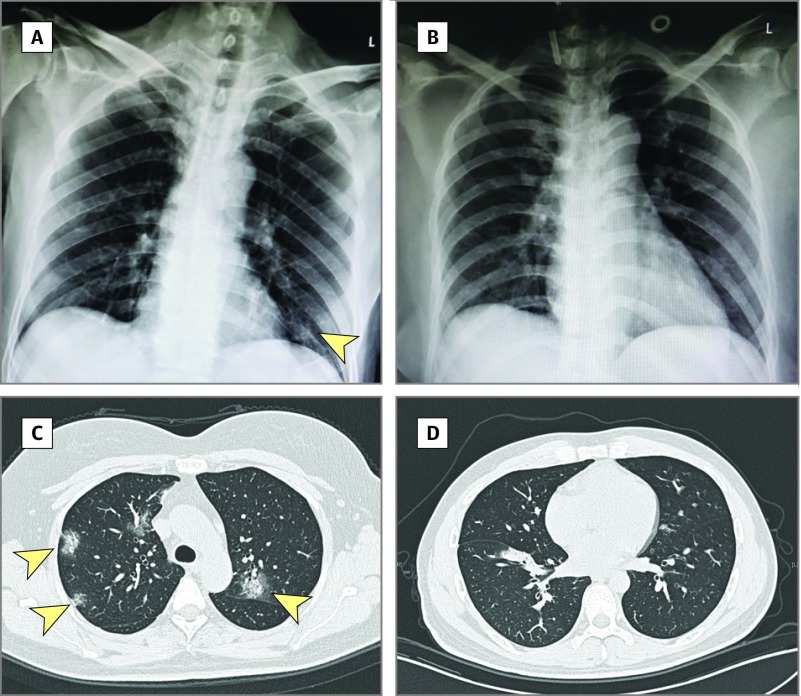

Four patients had chest radiographs and 9 had computed tomography. Five images did not demonstrate any consolidation or scarring. One chest radiograph demonstrated scattered opacities in the left lower lung; in 6 patients, ground glass opacity was observed in the right or both lungs (Figure). As of February 4, 2020, all the patients recovered, but 12 were still being quarantined in the hospital.

Figure. Chest Imaging of Patients Infected With 2019 Novel Coronavirus.

A, Chest radiograph from a 69-year-old man, showing scattered opacities in lower left lobe (arrowhead). B, Normal chest radiograph from a 32-year-old woman. C, Chest computed tomography (CT) scan from a 49-year-old woman, showing bilateral ground glass opacities (arrowheads). D, Normal chest CT scan from a 34-year-old man.

Discussion

The current coronavirus outbreak in China is the third epidemic caused by coronavirus in the 21st century, already surpassing SARS and MERS in the number of individuals infected.1 The higher number of infections may be attributable to late identification of the etiologic agent and the ability of the host to shed the infection while asymptomatic, rather than to greater infectivity of the virus compared with SARS.3

This case series provides information on the epidemiology of the disease outside Wuhan. Most patients visited or came in close contact with individuals from Wuhan, but 1 patient did not, suggesting possible active viral transmission in Beijing. Close monitoring will be needed to prevent large-scale spread of the virus to other cities in China.

Most of the infected patients were healthy adults; only 1 patient was older than 50 years and 1 younger than 5 years. This might be related to limited travel by younger and older patients rather than decreased susceptibility of these populations. Recovery of all patients suggests milder infections. The study is limited by lack of detailed data after transfer. These data contribute information to understanding the early clinical manifestations of 2019-nCoV.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report-15. Published February 4, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200204-sitrep-15-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=88fe8ad6_2

- 2.Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold [published online January 23, 2020]. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia [published online January 29, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. [published online January 24, 2020]. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Leung GM, et al. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1761-1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed AE. The predictors of 3- and 30-day mortality in 660 MERS-CoV patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):615. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2712-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]