Abstract

Background:

The frequency of clinicoepidemiological variants of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) differs markedly throughout the world. The iatrogenic variant is mainly associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapy.

Aims:

We aimed to investigate the distribution of KS variants in our practice and elucidate the underlying causes of iatrogenic KS.

Methods:

Consecutive KS patients seen in a single tertiary center were grouped according to the tumor variants and iatrogenic KS patients were evaluated about associated conditions.

Results:

Among 137 patients, classic variant was the most frequent presentation (n = 88), followed by iatrogenic (n = 37) variant. Among the iatrogenic group, ten were transplant recipients. In 16 iatrogenic KS patients, systemic corticosteroid was used, in four for myasthenia gravis (MG) and in three for rheumatoid arthritis. In three patients, KS developed under topical corticosteroid (TC) treatment. Among iatrogenic KS patients, ten of them had a second primary neoplasm and one had congenital immunodeficiency syndrome.

Conclusions:

Our study revealed one of the highest rates for iatrogenic KS (27%) reported in the literature. Besides well-known causes, relatively frequent association with MG was remarkable. Usage of different forms of TCs was the cause of KS in a few cases.

KEY WORDS: Corticosteroid, iatrogenic, Kaposi's sarcoma, myasthenia gravis, mycosis fungoides

Introduction

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a multicentric angioproliferative tumor of the mesenchymal origin. In addition to the HHV-8 infection, genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors are also usually required for the development of KS.[1] Four clinicoepidemiological variants of KS have been described: classic, African, AIDS-associated, and iatrogenic.[1,2] The iatrogenic variant is typically associated with immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants and other diseases.[2] The frequency of these variants changes markedly in many reports from different countries.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] We evaluated long-term data of our center about KS to investigate the distribution of the tumor variants focusing on the underlying causes of iatrogenic KS cases.

Materials and Methods

Consecutive KS patients seen between January 2007 and November 2017 were retrospectively investigated. In all patients, diagnosis was established due to skin and/or mucous membrane lesions and was confirmed histopathologically. The demographic features of the patients were recorded. All patients were tested for HIV serology. The patients were grouped according to the four major clinicoepidemiological variants of the tumor. Patients with iatrogenic KS were evaluated about underlying causes such as organ transplantation, other diseases associated with immunosuppression and causative immunosuppressive treatments including also the topical medications. The long-term follow-up data of patients in this group were also reviewed. This study has been approved by our Institutional Review Board (approval number: 2017/207).

Results

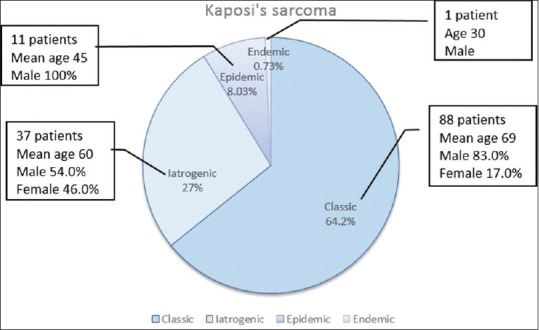

Among 137 KS patients (M/F: 3.3, mean age: 64.6 ± 16) included in the study, 88 corresponded to the classic form, 37 to iatrogenic, 11 to epidemic, and 1 to endemic form [Figure 1]. The mean ages of the patients were 69.2 ± 14, 60.3 ± 15, 45.4 ± 14 in the classical, iatrogenic, and epidemic KS groups, respectively. The male-to-female ratio was 4.9 in the classical and 1.2 in the iatrogenic group. All patients in the epidemic group and the single African patient were male.

Figure 1.

The distribution of 137 Kaposi's sarcoma patients according to clinicoepidemiological variants

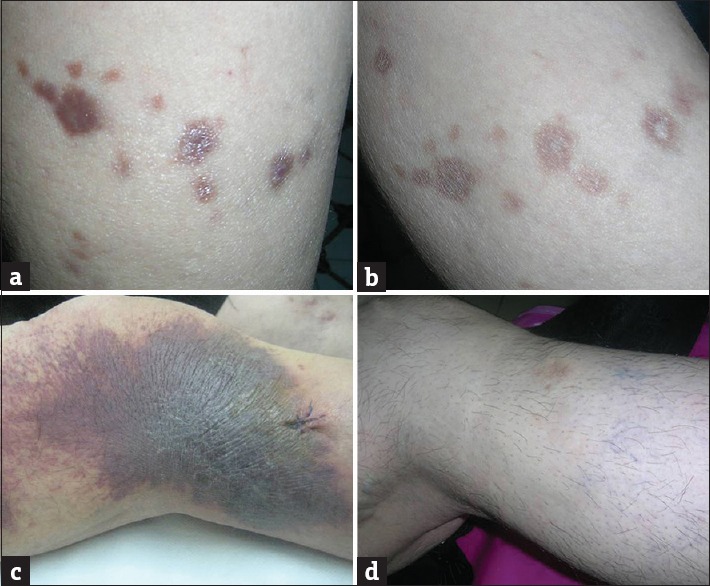

All but 1 iatrogenic KS patients had skin lesions [Figures 2 and 3], 1 of them had only mucosal involvement and 11 of them had biopsy-proven extracutaneous involvement. The clinical features and follow-up data of iatrogenic KS patients are summarized in Tables 1–3.

Figure 2.

(a) A solitary nodule of Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with mycosis fungoides (Table 2, Patient 4). (b) Plaque lesions of Kaposi's sarcoma on the foot and verrucae on the hand in a child with congenital immunodeficiency (Table 3, Patient 19). (c) Verrucous plaque of Kaposi's sarcoma on the dorsum of the foot in a patient with myasthenia gravis (Table 3, Patient 2). (d) Large plaque of Kaposi's sarcoma covering the lower leg in a patient with myasthenia gravis (Table 3, Patient 1). (e) Large tumor of Kaposi's sarcoma on the tongue of a patient with myasthenia gravis (Table 3, Patient 1). (f) Papules and nodules of Kaposi's sarcoma on the trunk occurred after liver transplantation (Table 1, Patient 7)

Figure 3.

(a and b) Regression of papulonodular Kaposi's sarcoma lesions on the lower leg in a patient with liver transplantation after switch of cyclosporine to sirolimus. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is noticeable (Table 1, Patient 7). (c and d) Complete regression of Kaposi's sarcoma lesions on the leg in a patient with Crohn's disease after cessation of systemic corticosteroid (Table 3, Patient 4)

Table 1.

Clinical features of iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma patients associated with organ transplantation

| Patient age/sex | Underlying disease | Immunosuppressive treatment before KS development | Localization (skin lesions) | Extracutaneous involvement | Management of KS | Follow-up (after KS diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 46/male | Renal tx | CsA | Face | Gastrointestinal | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 2. 50/male | IgA nephropathy, renal tx* | AZA, SC, MMF | Upper and lower extremity, ears, penis | Urethra | Sirolimus used from the early period of tx, excision, RT, CT | Relapse and dissemination after tx showing no response to therapy, remission following transplant rejection |

| 3. 60/female | Renal tx, SLE | CsA, SC | Lower extremity | - | Radiotherapy | No relapse in 9 years follow-up, MDS development |

| 4. 60/male | Renal tx | CsA, MMF, tacrolimus | Lower extremity, torso | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 5. 46/female | Renal tx | CsA, AZA, SC | Lower extremity | Oral mucosa | Switch to sirolimus | Remission in 1-year follow-up |

| 6. 55/male | Renal tx | CsA, SC | Face, lower extremity | Oral mucosa, gastrointestinal | Switch to sirolimus | Remission, relapse after 10 years followed by remission with SC tapering |

| 7. 58/female | Liver tx | CsA | Lower extremity | - | Switch to sirolimus | Remission in 2 years follow-up |

| 8. 47/male | Liver tx, HCV infection (recurring after tx) | CsA | Lower extremity | - | - | Deceased in 1-month due to another reason |

| 9. 70/male | Renal tx | SC, MMF† | Lower extremity | - | - | Relapse after 22 years |

| 10. 65/female | Renal tx | SC, MMF | Lower extremity | - | Excision | Remission in 2 years follow-up |

*Transplantation was performed after development of KS while the patient was in remission, †Treatment during KS relapse. tx: Transplantation, AZA: Azathioprine, CsA: Cyclosporine A, MMF: Mycophenolate mofetil, SC: Systemic corticosteroid, CT: Chemotherapy, RT: Radiotherapy, SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus, MDS: Myelodysplastic syndrome, IgA: Immunoglobulin A, HCV: Hepatitis C virus, KS: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Table 3.

Clinical features of iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma patients associated with immunosuppressive therapy in miscellaneous diseases including myasthenia gravis, rheumatoid arthritis and congenital immunodeficiency

| Patient age/sex | Underlying disease | Immunosuppressive treatment before KS | Localization (skin lesions) | Extracutaneous involvement | Management of KS | Follow-up (after KS diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 52/male* | MG, thymoma | SC | Lower extremity | Oral mucosa | Decrement in SC dosage, chemotherapy | No remission, deceased after 5-year follow-up due to MG |

| 2. 66/male* | MG, thymoma | SC, IVIG | Upper and lower extremity, torso | Conjunctiva | Decrement in SC dosage | No remission, deceased after 4-year follow-up due to MG |

| 3. 81/female | IgA nephropathy | SC | Lower extremity | - | - | Deceased after 1-month follow-up due to another condition |

| 4. 63/female | Crohn’s disease | SC | Lower extremity | - | Cessation of SC | Remission, no relapse in 8-year follow-up |

| 5. 45/male | Nephrotic syndrome | SC, CsA | Upper and lower extremity, torso | - | Cessation of CsA and SC | Remission, no relapse in 6-year follow-up |

| 6. 68/male | MG | SC, AZA | Lower extremity | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 7. 71/male | MG | SC | Lower extremity | Oral mucosa | Decrement in SC dosage | No remission in 1-year follow-up |

| 8. 42/female | Dermatomyositis | SC, AZA | Upper and lower extremity | - | Cessation of AZA, decrement in SC dosage, switch to IVIG | Remission, relapse after 4-year follow-up |

| 9. 69/male | Rheumatoid arthritis | SC | Lower extremity, torso | - | - | Deceased in 1 month due to another condition |

| 10. 60/male | Systemic vasculitis | SC | Upper and lower extremity | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 11. 79/female | Rheumatoid arthritis | SC | Upper and lower extremity | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 12. 50/female | Pemphigus vulgaris | SC, AZA, MMF | Lower extremity | - | Imiquimod cream | Remission, deceased after 1-year follow-up due to another condition |

| 13. 61/female | Rheumatoid arthritis | SC, MTX, leflunomide | Upper and lower extremity, neck | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 14. 80/female | Adrenal insufficiency | SC | Lower extremity | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 15. 55/female | Sarcoidosis | SC | Upper and lower extremity | Oral mucosa | Cessation of SC | Remission |

| 16. 80/male | ITP | SC | Lower extremity | - | Cessation of SC, etoposide | Remission |

| 17. 83/female | Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy | TC (eyedrop) | - | Conjunctiva (solitary) | Surgical excision | Remission, relapse after 10 months, re-excision |

| 18. 72/female | Psoriasis vulgaris | TC (ointment) | Lower extremity | - | Cessation of TC, etoposide | Lost to follow-up |

| 19. 16/female | Congenital immunodeficiency | No treatment | Upper and lower extremity, face, ear | Bone | IFN-alpha, chemotherapy | No remission in 10-year follow-up |

*Patients also associated with neoplasia (thymoma). SC: Systemic corticosteroid, TC: Topical corticosteroid, MG: Myasthenia gravis, MMF: Mycophenolate mofetil, IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin, CsA: Cyclosporine, AZA: Azathioprine, MTX: Methotrexate, ITP: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, IgA: Immunoglobulin A, IFN: Interferon, KS: Kaposi’s sarcoma

In the group of patients with iatrogenic KS, 10 were transplant recipients (eight of them with renal and two with liver transplantation) [Table 1, Figure 2f]. In one of these patients, renal transplantation was performed following diagnosis of KS, which seemed to be related to systemic corticosteroid (SC) and azathioprine treatment for IgA nephropathy. KS showed complete regression with cessation of immunosuppressive therapy. However, the lesions relapsed after transplantation although sirolimus was used from the beginning. All of the other transplant recipients had used cyclosporine or mycophenolate mofetil therapy before development of KS [Table 1].

Ten patients in iatrogenic KS group had a variety of neoplasia: two mycosis fungoides (MF), one myelodysplastic syndrome, one Hodgkin lymphoma, one peripheral T-cell lymphoma, two systemic follicular lymphomas, two thymomas, and one bladder adenocarcinoma [Table 2].

Table 2.

Clinical features of iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma patients associated with neoplasia

| Patient age/sex | Underlying disease | Immunosuppressive treatment before KS development | Localization (skin lesions) | Extracutaneous involvement | Management of KS | Follow-up (after KS diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 53/female | Follicular NHL | CT (fludarabine) | Lower extremity | - | - | Deceased after 1-year follow-up due to lymphoma |

| 2. 81/male | Follicular NHL | SC, CT (unknown regimen) | Torso | - | - | Deceased after 2-month follow-up due to lymphoma |

| 3. 55/female | Myelodysplastic syndrome | SC | Upper and lower extremity | - | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 4. 77/male | Mycosis fungoides (stage 1B) | PUVA, TC (cream) | Lower extremity (solitary) | - | Surgical excision | No relapse in 2-year follow-up, deceased due to another condition |

| 5. 79/male | Mycosis fungoides (stage 1B)* | PUVA, IFN-alpha, acitretin | Lower extremity (solitary) | - | Surgical excision | Relapsed after 2-year follow-up |

| 6. 38/male | Hodgkin lymphoma | CT (ABVD), RT | Upper and lower extremity | Tonsil | Unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 7. 44/male | Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | CT (CHOP) | Upper and lower extremity, torso, face | - | RT, IFN-alpha, CT (paclitaxel) | Deceased after 1-year follow-up due to lymphoma |

| 8. 54/male | Bladder adenocarcinoma | CT, RT | Lower extremity, face | - | - | Deceased after 2-month follow-up due to another condition |

*With a plaque showing large cell transformation. Patients with thymoma and MG are given in Table 3 TC: Topical corticosteroid, NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, IFN: Interferon, CT: Chemotherapy, RT: Radiotherapy, ABVD: Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, doxorubicin, CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, SC: Systemic corticosteroid, KS: Kaposi’s sarcoma, PUVA: Psoralen and Ultraviolet A

In 16 iatrogenic KS patients, SC was the possible triggering factor; in three of them combined usage with azathioprine and in others with cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, leflunomide, and methotrexate were observed. In four of these patients, SC was used for myasthenia gravis (MG) (two of them had also thymoma), in three for rheumatoid arthritis, in others for dermatomyositis, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), systemic vasculitis, Crohn's disease, IgA nephropathy, nephrotic syndrome, sarcoidosis, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. A patient with adrenal insufficiency using physiologic corticosteroid dose for a long period was also evaluated as having iatrogenic KS [Table 3].

In three patients, KS developed under long-term topical corticosteroid (TC) therapy [Tables 2 and 3]. Two of these cases (one with MF and one with psoriasis) had used corticosteroid ointments, and the other one had been treated with TC eyedrops, which resulted in unilesional conjunctival KS development.

The single patient diagnosed in childhood had some other findings of an immunodeficiency syndrome such as disseminated verruca [Figure 2b] and progressive course of KS resulting in bone involvement.[14,15]

There were 11 patients (8.03%) with association of HIV infection. In one of these patients, lesions of KS were aggravated after SC therapy for proteinuria.

Discussion

This single-center study about 137 KS patients seen over an 11-year period provides useful information about percentages of KS variants in Turkey; remarkably, iatrogenic KS was the second common (27%) variant following classic KS. There is no common distribution pattern of KS subtypes in studies reported from different regions of the world [Table 4].[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] In the great majority of case series, classic KS is the most common variant, as in our series.[3,4,5,6,8,9,10,12,13] From large KS series conducted with more than 100 patients, the previous highest rate of iatrogenic KS was reported from Israel (13.6%).[3] In two smaller series of 20 and 28 non-AIDS-related KS patients from Germany and Turkey, the frequency of iatrogenic KS was 25%[6] and 32.2%,[4] respectively. The results of our series with >100 patients (27% in general and 29.4% in non-AIDS-related patients) represent the highest rate of iatrogenic KS. Our clinic is a tertiary care center in Istanbul where many hematology, oncology, and transplant unit consultations are performed which may be a cause of this high rate.

Table 4.

Kaposi’s sarcoma series reported in the literature evaluating clinicoepidemiological variants of the disease

| Study/Country/Year | Patient number/study period | Classic KS (%) | Iatrogenic KS (%) | Epidemic KS (%) | Endemic KS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weissmann et al./Israel/2000[3]* | 125/1957-1993 | 108 (86.4) | 17 (13.6) | * | - |

| Senturk et al./Turkey/2001[4]* | 28/1987-1997 | 19 (67.8) | 9 (32.2) | * | - |

| Dogan et al./Turkey/2010[5] | 51/1998-2009 | 50 (98.03) | - | 1 (1.9) | - |

| Jakob et al./Germany/2011[6]* | 20/1987-2009 | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | * | - |

| Tiussi et al./Brazil/2012[7] | 15/1986-2009 | 3 (20) | - | 12 (80) | - |

| Zaraa et al./Tunis/2012[8] | 75/1982-2007 | 70 (93.3) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.3) | - |

| Wu et al./China/2014[9]† | 105/1997-2013 | 77 (73.3) | † | 28 (26.7) | - |

| Rescigno et al./Italy/2013[10]* | 32/2008-2012 | 27 (84.3) | 5 (15.7) | * | - |

| Laresche et al./France/2014[11] | 57/1977-2009 | 17 (30) | 5 (9) | 35 (61) | - |

| Kamyab et al./Iran/2014[12] | 34/2006-2011 | 29 (85) | 5 (15) | - | - |

| Sen et al./Turkey/2016[13]* | 128/1997-2014 | 113 (88.3) | 15 (11.7) | * | - |

| Present study/Turkey/2018 | 137/2007-2017 | 88 (64.2) | 37 (27) | 11 (8.03) | 1 (0.73) |

*Non-AIDS-associated KS cases included only, †Iatrogenic KS cases excluded. KS: Kaposi’s sarcoma

The predisposition to iatrogenic KS among transplant recipients varies between populations.[16,17] Furthermore, iatrogenic KS is seen relatively frequently among renal transplant recipients of Jewish or Mediterranean origin, including Turkey.[17,18,19] A lower incidence of KS observed among transplant recipients in the United States was attributed to the much lower HHV-8 prevalence in the United States compared to other countries.[16] However, it is still uncertain whether iatrogenic KS is due to the reactivation of HHV-8 or to primary infection.[16,20] In our series, organ transplantation was the cause of iatrogenic KS in ten patients (in one of them only the cause of KS's relapse); eight of them were renal and the other two were liver transplant recipients.

Glucocorticoids have been associated with the development of KS and also rapid growth or dissemination of the disease.[21,22,23] Studies suggest that corticosteroids induce KS by indirectly inhibiting transforming growth factor-beta, a protein that inhibits the growth of endothelial cells.[21] KS was reported in patients receiving corticosteroids for a large spectrum of indications, mainly autoimmune diseases.[2] In a recently published large series of 143 iatrogenic KS patients, rheumatoid arthritis (12.7%) was the most common cause of this KS type in nonorgan transplant recipients, followed by polymyalgia rheumatica (10%) and MG (8.2%).[24] Remarkably in our series, 4 of the 16 iatrogenic KS patients with SC usage had MG [Figure 2c–e], 2 of them associated with thymoma. The potential correlation between KS and MG has been suggested previously.[25] The high percentage of MG patients in our series supports an additional possible etiologic factor for KS in this neurologic disease. In the above-mentioned large series, 5.5% of nonorgan transplant patients with KS had bullous pemphigoid.[24] There are also rare KS cases reported in pemphigus patients.[26,27] However, a study comparing the frequency of skin tumors in PV patients with renal transplant recipients did not show an increased risk for KS in PV group.[28] Similarly, in our clinic, >200 patients with pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid were treated with SC in the last 10 years (unpublished data) and KS was observed only in one PV patient. In one of our iatrogenic KS patients, KS occurred following SC treatment used for sarcoidosis. Concomitant KS and sarcoidosis have been described previously, but the studies aiming to clarify the relationship between HHV-8 infection and sarcoidosis have failed to demonstrate a link between them.[29,30,31] The co-occurrence of iatrogenic KS with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura receiving SC treatment was limited to only a few cases reported previously with no risk factor other than corticosteroid-induced immunosuppression, as in one of our iatrogenic KS patients.[32]

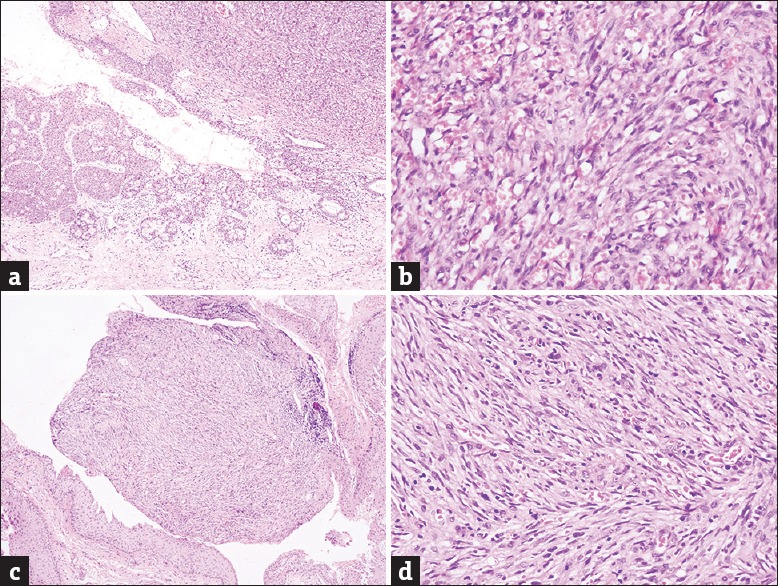

Although SC usage is one of the major causes of iatrogenic KS, there are only three KS cases reported after intraarticular and/or epidural injections of corticosteroids,[23,33,34] and a few cases related to topical use of corticosteroids.[35,36,37] In two reports about KS development in PV patients, the role of TC (ointment/intralesional) was emphasized.[26,27] The authors suggested that although both patients were receiving immunosuppressive treatment including SC, local application of corticosteroid might have caused additional decrease in immunity leading to KS development.[26,27] In another report, recurrence of KS on the tongue was reported after TC usage for erosive oral lichen planus and the lesion regressed after withdrawal of local therapy.[37] On the other hand, in three cases, we suspected TC as the probable cause of KS. One of them had used corticosteroid eyedrops for a very long period due to pseudophakic bullous keratopathy resulting in unilesional conjunctival KS development [Figure 4]. Iatrogenic KS due to eyedrop usage containing corticosteroid was not formerly reported. Another case had stage 1B MF which was treated only with PUVA and TC before development of unilesional KS [Figure 2a] in close proximity to the treated MF lesions. Finally, the third case who had not received any other topical or systemic treatment than potent TC for generalized psoriasis developed multilesional KS on the legs only. Interestingly in a large series from Turkey, two cases (2.7%) of KS showed association with psoriasis vulgaris, but usage of TC was not stated in these patients.[38] Although there is insufficient data regarding the relationship between TC usage and skin cancer (melanoma and nonmelanoma),[39] cases of KS related with TC usage reported in the literature along with our cases might be significant.[23,26,27,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 4.

(a) Conjunctival lesion of Kaposi's sarcoma located on the junctional area between normal epithelium containing numerous goblet cells and tumor area in upper right (H and E, ×100) (Table 3, Patient 2). (b) Higher magnification from tumor area shows spindle cell fascicles and slit-like small vascular spaces filled with erythrocytes (H and E, ×400). (c) Conjunctival tumor of another patient causing a small nodule surrounded by epithelial parts (H and E, ×100) (Table 3, Patient 17). (d) The nodule is composed of interlacing bundles of spindle cells and many tiny vascular spaces seen in higher magnification (H and E, x400)

The association of KS with other primary malignancies (15%–37%), especially of the hematolymphoid system (6%–27%) has been well-known.[40,41,42] The second primary malignancy may precede, coincide with or follow the occurrence of KS.[3,40,41,42] In our series, a second primary neoplasm was noted in ten patients in iatrogenic KS group, of which seven were hematolymphoid system disorders. All tumors were diagnosed before KS diagnosis. Unlike for nodal lymphomas, the relationship of cutaneous lymphoma and KS is not well understood.[43] However, in a literature review of 65 cases investigating the association of KS and other types of neoplasia, six patients (9%) had MF.[41] In our study period, nearly 500 MF patients were followed in our department (unpublished data), and interestingly, we diagnosed KS in two patients. Patients in the early stages of MF are not under risk of immunosuppression,[44] therefore the co-occurrence of these tumors in two patients seems to be noteworthy.

The relationship of inborn immunodeficiency and KS is not well understood. One of our patients was diagnosed with KS in early childhood. She was also reported elsewhere as “classic KS born to consanguineous kindreds” and in another report “OX40 deficiency” was detected in this patient.[14,15] However, the tumor was persistent and resulted in bone involvement by the time when the patient reached age 23. Furthermore, KS occurring in childhood with primary immunodeficiency conditions has only been reported in a few cases.[45,46] Although exceedingly rare, classic KS may be seen in otherwise healthy children.[47]

The term iatrogenic KS theoretically covers only “KS cases associated with therapy-induced immunosuppression” and its course is generally accepted to be more severe than classic type. However, the term “immunosuppression-associated KS” has also been used for this type,[48,49] but it has not been well described whether it also includes all immunosuppression associated conditions such as congenital immunodeficiency syndromes and acquired diseases such as lymphoproliferative disorders independent of their therapy. We classified our child patient with congenital immunodeficiency showing aggressive course as iatrogenic- or immunosuppression-associated KS. The classification of KS cases associated with hematolymphoid malignancies, in which KS occurs before therapy may also be a matter of debate. On the other hand, in two of our cases triggered by TC usage, KS presented as a solitary lesion. The term “iatrogenic” is convenient within to the etiology in these latter cases, but the mild course was different from SC-induced cases. Therefore, iatrogenic KS seems to have a wider spectrum than previously recognized.

Iatrogenic KS can present a therapeutic dilemma. Restoring immune competency by reducing or withdrawing immunosuppression may induce spontaneous remission of KS and represents the first-line management option in this variant.[2,50] However, reducing immunosuppression may sometimes not be possible or may result organ rejection in transplant recipients or organ damage in patients with autoimmune disorders.[2,50] Some cases do not improve after reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppression, and consequently, require systemic treatment. In transplant recipients, use of sirolimus may lead to resolution of KS.[51,52] Since mTOR inhibitors are primarily cytostatic, their clinical efficacy is probably more a reflection of disease stabilization rather than regression.[52] In three of our transplant patients switching from immunosuppressive therapy to sirolimus resulted in long-term regression of lesions, even though in one of them KS relapsed after 10 years of remission period. On the other hand, in one of the patients in whom KS was diagnosed before transplantation, using sirolimus immediately following transplantation was not effective, but lesions partially regressed after complete cessation of immunosuppressive therapy and renal rejection. Moreover, in three MG patients, the lesions could not be controlled by steroid tapering and even despite chemotherapy in one.

The main limitations of the study were the retrospective design and the fact that it was conducted in a single center, which may have affected the distribution of the subtypes of the disease.

Conclusions

We observed iatrogenic variant of KS more commonly than reported in large series in the literature. KS may occur in the course of several diseases treated with SC as our study also shows and MG was a relatively common underlying disease of SC-induced lesions. Although being not very common, two skin malignancies, MF and KS may develop in the same patient. Usage of different forms of TC should be questioned in KS patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ruocco E, Ruocco V, Tornesello ML, Gambardella A, Wolf R, Buonaguro FM, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: Etiology and pathogenesis, inducing factors, causal associations, and treatments: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buonaguro FM, Tornesello ML, Buonaguro L, Satriano RA, Ruocco E, Castello G, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: Aetiopathogenesis, histology and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:138–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissmann A, Linn S, Weltfriend S, Friedman-Birnbaum R. Epidemiological study of classic Kaposi's sarcoma: A retrospective review of 125 cases from Northern Israel. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:91–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senturk N, Sahin S, Ercis S, Kocagoz T, Atakan N. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) in non-HIV associated forms of Kaposi's sarcoma from Turkey. Turk J Med Sci. 2001;31:503–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogan M, Dogan L, Ozdemir F, Ozdemir NY, Coskun HS, Arslan UY, et al. Fifty-one Kaposi sarcoma patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:629–33. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakob L, Metzler G, Chen KM, Garbe C. Non-AIDS associated Kaposi's sarcoma: Clinical features and treatment outcome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiussi RM, Caus AL, Diniz LM, Lucas EA. Kaposi's sarcoma: Clinical and pathological aspects in patients seen at the hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio Moraes-Vitória-Espírito Santo-Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:220–7. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaraa I, Labbene I, El Guellali N, Ben Alaya N, Mokni M, Ben Osman A, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: Epidemiological, clinical, anatomopathological and therapeutic features in 75 patients. Tunis Med. 2012;90:116–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu XJ, Pu XM, Kang XJ, Halifu Y, An CX, Zhang DZ, et al. One hundred and five Kaposi sarcoma patients: A clinical study in Xinjiang, Northwest of China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1545–52. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rescigno P, Di Trolio R, Buonerba C, De Fata G, Federico P, Bosso D, et al. Non-AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: A single-institution experience. World J Clin Oncol. 2013;4:52–7. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v4.i2.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laresche C, Fournier E, Dupond AS, Woronoff AS, Drobacheff-Thiebaut C, Humbert P, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: A population-based cancer registry descriptive study of 57 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1977 and 2009. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e549–54. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamyab K, Ehsani AH, Azizpour A, Mehdizad Z, Aryanian Z, Goodarzi A, et al. Demographic and histopathologic study of Kaposi's sarcoma in a dermatology clinic in the years of 2006 to 2011. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen F, Tambas M, Ciftci R, Toz B, Kilic L, Bozbey HU, et al. Factors affecting progression-free survival in non-HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:275–7. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1094177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin G, Palanduz A, Aydogan G, Cassar O, Ertem AU, Telhan L, et al. Classic Kaposi sarcoma in 3 unrelated Turkish children born to consanguineous kindreds. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e704–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byun M, Ma CS, Akçay A, Pedergnana V, Palendira U, Myoung J, et al. Inherited human O×40 deficiency underlying classic Kaposi sarcoma of childhood. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1743–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbulaiteye SM, Engels EA. Kaposi's sarcoma risk among transplant recipients in the United States (1993-2003) Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2685–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zavos G, Bokos J, Papaconstantinou I, Boletis J, Gazouli M, Kakisis J, et al. Clinicopathological aspects of 18 Kaposi's sarcoma among 1055 Greek renal transplant recipients. Artif Organs. 2004;28:595–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2004.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iscovich J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88:500–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berber I, Altaca G, Aydin C, Dural A, Kara VM, Yigit B, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma in renal transplant patients: Predisposing factors and prognosis. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:967–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreoni M, Goletti D, Pezzotti P, Pozzetto A, Monini P, Sarmati L, et al. Prevalence, incidence and correlates of HHV-8/KSHV infection and Kaposi's sarcoma in renal and liver transplant recipients. J Infect. 2001;43:195–9. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai J, Zheng T, Lotz M, Zhang Y, Masood R, Gill P, et al. Glucocorticoids induce Kaposi's sarcoma cell proliferation through the regulation of transforming growth factor-beta. Blood. 1997;89:1491–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, Sandbank M. The appearance of Kaposi sarcoma during corticosteroid therapy. Cancer. 1993;72:1779–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930901)72:5<1779::aid-cncr2820720543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trattner A, Hodak E, David M, Neeman A, Sandbank M. Kaposi's sarcoma with visceral involvement after intraarticular and epidural injections of corticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:890–4. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70264-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brambilla L, Tourlaki A, Genovese G. Iatrogenic Kaposi's sarcoma: A Retrospective cohort study in an Italian tertiary care centre. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017;29:e165–e171. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantero V, Mascolo M, Bandettini di Poggio M, Caponnetto C, Pardini M. Myasthenia gravis developing in an HIV-negative patient with Kaposi's sarcoma. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:1249–50. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avalos-Peralta P, Herrera A, Ríos-Martín JJ, Perez-Bernal AM, Moreno-Ramirez D, Camacho F. Localized Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serdaroglu S, Antonov M, Demirkesen C, Tuzun Y. Iatrogenic Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:839–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharquie KE, Noaimi AA, Al-Jobori AA. Skin tumors and skin infections in kidney transplant recipients vs. patients with pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:288–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salle de Chou C, Tazi A, Battistella M, Saussine A, Petit A, Rybojad M, et al. Sarcoidosis associated with Kaposi's sarcoma: Description of four cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:550–1. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fredricks DN, Martin TM, Edwards AO, Rosenbaum JT, Relman DA. Human herpesvirus 8 and sarcoidosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:559–60. doi: 10.1086/338406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.di Gennaro G, Canzonieri V, Schioppa O, Nasti G, Carbone A, Tirelli U, et al. Discordant HHV8 detection in a young HIV-negative patient with Kaposi's sarcoma and sarcoidosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1100–2. doi: 10.1086/319603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi KH, Byun JH, Lee JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. Kaposi sarcoma after corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:297–9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnet SP, McNeil JD. Kaposi's sarcoma in an elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis after intra-articular corticosteroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:107–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azais I, Lambert de Cursay G, Deblais F, Deschamps O, Gandon P, Alcalay M, et al. Association of rheumatoid arthritis and Kaposi disease. Apropos of a case arising after intraarticular corticotherapy. Rev Rhum Ed Fr. 1993;60:240–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyros G, Potouridou I, Tsaraklis A, Korkolopoulou P, Christofidou E, Polydorou D, et al. A generalized Kaposi's sarcoma after chronic and extensive topical corticosteroid use. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:111–2. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boudhir H, Mael-Ainin M, Senouci K, Hassam B, Benzekri L. Kaposi's disease: An unusual side-effect of topical corticosteroids. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140:459–61. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2013.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pérez E, Barnadas MA, García-Patos V, Pedro C, Curell R, Sander CA, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with erythroblastopenia and thymoma: Reactivation after topical corticosteroids. Dermatology. 1998;197:264–7. doi: 10.1159/000018010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demirel BG, Koca R, Tekin NS, Kandemir NO, Gün BD, Köktürk F. Classic Kaposi's sarcoma: The clinical, demographic and treatment characteristics of seventy-four patients. Turkderm. 2016;50:136–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ratib S, Burden-The E, Leonardi-Bee J, Harwood C, Bath-Hextall F. Long-term topical corticosteroid use and risk of skin cancer: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16:1387–97. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Safai B, Miké V, Giraldo G, Beth E, Good RA. Association of Kaposi's sarcoma with second primary malignancies: Possible etiopathogenic implications. Cancer. 1980;45:1472–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800315)45:6<1472::aid-cncr2820450629>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulbright TM, Santa Cruz DJ. Kaposi's sarcoma: Relationship with hematologic, lymphoid, and thymic neoplasia. Cancer. 1981;47:963–73. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810301)47:5<963::aid-cncr2820470524>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ascoli V, Minelli G, Kanieff M, Crialesi R, Frova L, Conti S, et al. Cause-specific mortality in classic Kaposi's sarcoma: A population-based study in Italy (1995-2002) Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1085–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalamkarian AA, Sych LI. A case of coexistence of mycosis fungoides and Kaposi's sarcoma. Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1968;42:12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camcioglu Y, Picard C, Lacoste V, Dupuis S, Akçakaya N, Cokura H, et al. HHV-8-associated Kaposi sarcoma in a child with IFNgammaR1 deficiency. J Pediatr. 2004;144:519–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kusenbach G, Rübben A, Schneider EM, Barker M, Büssing A, Lassay L, et al. Herpes virus (KSHV) associated Kaposi sarcoma in a 3-year-old child with non-HIV-induced immunodeficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:440–3. doi: 10.1007/s004310050633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalkan G, Akbay G, Gungor E, Eken A, Ozkaya O, Kutzner H, et al. A case of classic Kaposi sarcoma in a 11-year-old male. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:730. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.86504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. Dermal and subcutaneous tumors; Kaposi sarcoma; pp. 590–2. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Innes AJ, Lee M, Francis N, Olavarria E. Immunosuppression-associated Kaposi sarcoma following stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2017;178:9. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lebbé C, Legendre C, Francès C. Kaposi sarcoma in transplantation. Transplant Rev. 2008;22:252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raeisi D, Payandeh M, Madani SH, Zare ME, Kansestani AN, Hashemian AH, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma after kidney transplantation: A 21-years experience. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2013;7:29–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Fijter JW. Cancer and mTOR inhibitors in transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:45–55. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]