Abstract

Neuroimaging studies reliably reveal ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) activation for processing of abstract relative to concrete words, but the cause of this effect is unclear. Here, in a convergent neuropsychological and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) investigation, we tested the hypothesis that abstract words require VLPFC because they depend heavily on the semantic–executive control processes mediated by this region. Specifically, we hypothesized that accessing the meanings of abstract words require more executive regulation because they have variable, context-dependent meanings. In the neuropsychology component of the study, aphasic patients with multimodal semantic deficits following VLPFC lesions had impaired comprehension of abstract words, but this deficit was ameliorated by providing a sentence cue that placed the word in a specific context. Concrete words were better comprehended and showed more limited benefit from the cues. In the second part of the study, rTMS applied to left VLPFC in healthy subjects slowed reaction times to abstract but not concrete words, but only when words were presented out of context. TMS had no effect when words were preceded by a contextual cue. These converging results indicate that VLPFC plays an executive regulation role in the processing of abstract words. This role is less critical when words are presented with a context that guides the system toward a particular meaning or interpretation. Regulation is less important for concrete words because their meanings are constrained by their physical referents and do not tend to vary with context.

Introduction

Abstract words form a critical part of human vocabulary yet relatively little is known about how they are processed in the brain. Though neuroimaging studies indicate differences in the neural substrates of concrete and abstract words, there is little consensus regarding the source of these differences. One of the areas most reliably activated in abstract word processing is left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) (Binder et al., 2009). Some researchers have interpreted VLPFC involvement within the dual-coding framework (Paivio, 1986), concluding that abstract words depend heavily on a verbal semantic network that includes VLPFC, whereas concrete words also activate a more widely distributed set of regions associated with perceptual experience (Sabsevitz et al., 2005; Binder et al., 2009).

An alternative perspective is provided by the context availability theory, which holds that abstract words are processed less efficiently because they are used in a diverse range of contexts, resulting in greater ambiguity in their meanings (Saffran et al., 1980; Schwanenflugel et al., 1988; Hoffman et al., 2010). Following this approach, comprehending an abstract word requires selection of a contextually appropriate meaning from multiple possible interpretations, a process that requires executive control processes (Fiebach and Friederici, 2004; Noppeney and Price, 2004; Bedny and Thompson-Schill, 2006). This view is in line with functional neuroimaging (Fiez, 1997; Thompson-Schill et al., 1997; Badre et al., 2005) and neuropsychological studies (Thompson-Schill et al., 1998; Jefferies and Lambon Ralph, 2006; Noonan et al., 2010) linking left VLPFC with executive regulation of semantic knowledge. The theory predicts that VLPFC involvement in abstract word processing is modulated by context and is maximized when words are presented individually, without disambiguating information (as is the case in most neuroimaging studies). Here, we tested this prediction for the first time by contrasting word comprehension in the presence or absence of sentence cues that placed the word in a specific context.

Most evidence of the relationship between VLPFC and abstract word knowledge comes from functional imaging studies. Although this technique reliably reveals VLPFC activation, it does not indicate whether the area is critical (Price and Friston, 2002). Here, in a two-part investigation, we established under what circumstances VLPFC makes a necessary contribution to abstract word comprehension. First, we tested comprehension in stroke patients with multimodal semantic impairment following VLPFC lesions. VLPFC damage was expected to have a more detrimental effect on abstract words. However, we predicted that when context was available to guide the semantic system toward the correct interpretation, there would be less need for VLPFC-mediated executive control, resulting in better performance for abstract words. In the second part, we used the region of maximum lesion overlap in the patient group to guide the targeting of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in healthy subjects, using the same experimental materials. Using this convergent approach, we were able to localize the robust behavioral effects found in the patient group to a specific cortical region (pars triangularis/BA 45).

Materials and Methods

Neuropsychological study

In the first part of this study, we investigated context effects in concrete and abstract word comprehension in patients with left VLPFC lesions following cerebral vascular accident. These individuals had multimodal semantic impairments as a result of poor regulation and control of semantic knowledge (which we refer to as semantic aphasia) (Corbett et al., 2009; Jefferies and Lambon Ralph, 2006; Noonan et al., 2010). We expected these patients to show particularly poor comprehension of abstract words because these words tend to have a number of possible interpretations and shades of meaning. As such, executive regulation is needed to select the appropriate aspects of meaning in any particular instance (Schwanenflugel and Shoben, 1983). The meanings of concrete words tend to be better specified because they refer to a specific class of tangible objects (e.g., “spinach” is used only in food-related contexts and always refers to a particular variety of vegetable). In contrast, abstract words are more nebulous and their precise meaning often depends on the context in which they are used. For example, the word “chance” can denote a situation governed by luck (“It's down to chance”), an opportunity that may arise in the future (“I'll do it when I get a chance”), or a risky option (“Take a chance”). In each of these examples, “chance” has the same core meaning relating to luck or uncertainty, but its precise interpretation is subtly different in each case. As a consequence, if “chance” is presented out of context, a number of potential ways of interpreting the word will come to mind and executive regulation will play an important role in biasing processing toward the relevant aspects of the meaning. The context availability theory states that this ambiguity in meaning comes about because abstract words can be used in wider range of contexts than concrete words. Empirical evidence for this assertion comes from a recent study in which latent semantic analysis was used to analyze variability in the linguistic contexts in which different words appear (Hoffman et al., 2010). Abstract words tended to appear in a more diverse range of contexts than concrete words.

On this basis, we predicted that the greater executive demands of comprehending abstract words could be ameliorated by preceding each word with a sentential context in which it could be used, helping to bias the system toward a particular interpretation. Concrete words should derive less benefit from context because their meanings are better specified to begin with. We also presented words following irrelevant sentences that were unrelated to their meaning. These could impair performance further by introducing additional competition into semantic processing that must be resolved by the damaged VLPFC executive system.

Patients.

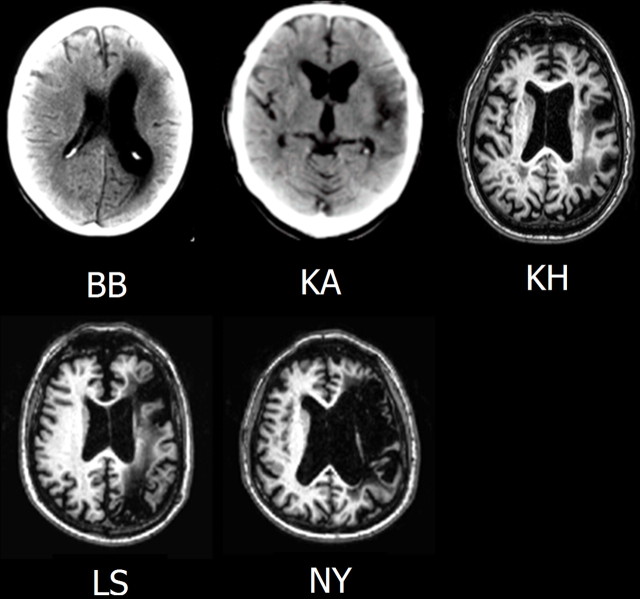

We tested six stroke aphasic patients with multimodal comprehension deficits, all of whom had left hemisphere damage that included VLPFC. They had participated in a number of previous studies in which their semantic impairments were linked to poor executive regulation of semantic knowledge (Jefferies and Lambon Ralph, 2006; Jefferies et al., 2007; Noonan et al., 2010). CT or MRI scans were available in five of the six cases (Fig. 1). Each patient's lesion was manually traced onto the standard template brain in MRIcro (Rorden and Brett, 2000); the resulting overlap map is shown in Figure 2. Prefrontal damage was present in all cases, although its precise focus and extent varied, with additional posterior cortical damage present in most cases. The area of maximal overlap was in BA 45, the region stimulated in our subsequent TMS experiment. Background information and results of neuropsychological tests are shown in Table 1, alongside published norms from healthy older adults. All patients displayed verbal and nonverbal semantic impairment. There were also signs of impairment in executive function.

Figure 1.

Structural CT and MRI images for patients. BB, KA, KH, LS, and NY, Patient initials.

Figure 2.

Lesion overlap map for patients and site of stimulation for rTMS. Left, Lesion overlap map for five of the six patients, showing maximum overlap in BA 45. Lighter shades indicate regions damaged in more patients. No scan was available for patient PG, though a radiologist's report of an earlier CT scan indicates left prefrontal lesion. Right, Site stimulated in rTMS experiment. Crosshairs indicate coordinates of rTMS site. Coordinates are in MNI space.

Table 1.

Demographic information and background neuropsychological tests

| Test | Patients |

Healthy subjectsg |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NY | PG | KH | BB | LS | KA | Mean | SD | |||||

| Sex | M | M | M | F | M | M | ||||||

| Age | 65 | 61 | 74 | 57 | 73 | 56 | ||||||

| Education [left school at age (years)] | 15 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | ||||||

| Semantica | ||||||||||||

| Picture naming (n = 64) | 51 | 44 | 29 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 62.3 | 1.6 | ||||

| Spoken word–picture matching (n = 64) | 60 | 58 | 54 | 54 | 37 | 26 | 63.7 | 0.5 | ||||

| Camel and Cactus Test | ||||||||||||

| Pictures (n = 64) | 36 | 44 | 46 | 38 | 15 | 46 | 59.0 | 3.1 | ||||

| Words (n = 64) | 39 | 40 | 41 | 30 | 16 | 36 | 60.7 | 2.1 | ||||

| Category fluency (8 categories) | 27 | 7 | 21 | 13 | 13 | NT | 113.9 | 12.3 | ||||

| Attention/executive | ||||||||||||

| Digit spanb | ||||||||||||

| Forwards | 3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 6.8 | 0.9 | ||||

| Backwards | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | NT | 4.7 | 1.2 | ||||

| Colored progressive matricesc (n = 36) | 26 | 23 | 12 | 24 | 16 | 12 | >15 | |||||

| Wisconsin card-sorting taskd (n = 6) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | >1 | |||||

| Brixton spatial rule attainmente (n = 54) | 34 | 26 | 7 | 23 | 14 | 6 | >28 | |||||

| Visuospatialf | ||||||||||||

| Incomplete letters (n = 20) | 17 | 18 | 19 | 0 | 0 | NT | 19.2 | 0.8 | ||||

| Dot counting (n = 10) | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 6 | NT | 9.9 | 0.3 | ||||

| Position discrimination (n = 20) | 20 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 19.8 | 0.6 | ||||

| Cube analysis (n = 10) | 5 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 4 | NT | 9.7 | 2.5 | ||||

NT, Not tested; M, male; F, female.

aFrom the Cambridge Semantic Memory battery (Adlam et al., 2010).

c Raven (1962).

d Milner (1964).

f From the Visual Object and Space Perception battery (Warrington and James, 1991).

gData for healthy older adults are taken from published test norms and, for the semantic tests, from Bozeat et al. (2000) and Adlam et al. (2010).

Materials.

Patients performed comprehension judgments on 96 words split into high, medium, and low imageability conditions using values from the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Coltheart, 1981). Imageability ratings are a measure of how easily a word elicits a mental image. Concrete words have high imageability ratings and abstract words have lower ratings. Words in the high imageability condition had imageability values of >600 (mean, 622) and those in the low imageability condition had values of <300 (mean, 275). Medium imageability words ranged from 400 to 500 (mean, 452). In all analyses, medium and low imageability words were collapsed into a single abstract word condition to compare them with the more concrete high imageability words. To determine whether the abstract words had more variable meanings, we calculated their semantic diversity. Semantic diversity is a measure of how broad a range of linguistic contexts a word can be used in (Hoffman et al., 2010). High values indicate that the word occurs in a diverse set of contexts on very different topics, whereas low values indicate that the word is associated with a more restricted set of contexts. Abstract words were significantly more semantically diverse than abstract words (concrete mean, 1.48; abstract mean, 1.74; t(91) = 3.81, p < 0.001). The majority of the words were nouns but the abstract condition contained 11 verbs and three adjectives. Results below are based on the full set of words, but analyses conducted on the nouns only produced very similar results.

Procedure.

Patients completed two versions of a standard verbal comprehension test—synonym judgment—each containing the same 96 stimuli. In the first version (originally used by Jefferies et al., 2009), semantic judgments were made with minimal contextual information. Each trial consisted of a probe word presented with three choices, one of which had a similar meaning to the probe. The remaining two choices were not semantically related (e.g., “frog” was presented with “toad,” “jewel,” and “pickle”). The probe and three choices were presented in a written format and were also read aloud by the examiner. In the second version of the test, each probe and its choices were presented twice, preceded each time by a verbal cue consisting of two sentences. In one presentation, the cue was designed to reduce the executive control demands of comprehension by placing the probe in a specific context, and in the other, the cue was irrelevant to the meaning of the probe (Table 2). The test was completed over two sessions so that each probe was only presented once per session. Trials with contextual and irrelevant cues were interspersed in a random order and the cues were presented in written form and read aloud by the experimenter.

Table 2.

Examples of cues for concrete and abstract words

| Word | Contextual cue | Irrelevant cue |

|---|---|---|

| Advantage (abstract) | Sue got the job. Her skills were an advantage. | He is late to work. This is out of the ordinary. |

| Frog (concrete) | I saw something in the pond. It was a frog. | It was a windy day. We flew our kite. |

rTMS study

The neuropsychological study allowed us to test the hypothesis that abstract word comprehension is impaired in VLPFC patients due to the greater need for executive control in retrieving and selecting the appropriate semantic information for these words. This turned out to be the case (see Results). However, the neuroanatomical locus of this effect was difficult to ascertain precisely. An area within BA 45 was damaged in all five patients but, as Figure 2 indicates, there was considerable variation in the extent of the prefrontal damage and there was also damage to temporoparietal cortex in most cases. To determine whether VLPFC damage was responsible for the observed effects, we targeted the same region in healthy individuals using rTMS. Previous TMS studies have indicated a general role for VLPFC in semantic processing (Devlin et al., 2003; Gough et al., 2005). Here, we used TMS to probe its specific contribution to concrete and abstract words and the modulation of these effects by context.

Participants.

Thirteen students from the University of Manchester took part (six male; mean age, 22.2 years). All were right-handed native English speakers with no history of neurological disease or mental illness. They were not on any medication and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. All gave written informed consent and the experiment was reviewed and approved by the local ethics board. Subjects were reimbursed for their participation.

Materials.

We made two changes to the task used in the neuropsychological study. First, due to the time limit associated with the rTMS-induced refractory effect, we eliminated the irrelevant sentence condition. Second, to maximize the difference between concrete and abstract words, we removed the medium imageability words. We also supplemented the original test with additional words to give a total of 200 stimuli. Concrete words had a mean imageability rating of 576 and semantic diversity value of 1.53. Abstract words had a mean imageability of 289 and semantic diversity of 1.85 (both quantities were significantly different in the two conditions; t > 8.4, p < 0.0001). In this expanded set of words, there were more verbs; they accounted for 30% of the abstract words and 22% of the concrete words. In addition to the analyses for the full set of words reported below, we conducted a separate analysis restricted to only the nouns, which gave very similar results.

Task.

Each trial began with a fixation cross presented for 500 ms. On no-context trials, this was followed by the probe word and three choices appearing on the screen. Subjects indicated their response with a key press. Context trials began with the sentence cue, which appeared on screen for 6000 ms. Subjects were instructed to read this silently as it would be relevant to their next semantic judgment. The cue was followed by the fixation cross and then the probe and three choices in the same format as the no-context trials.

Control task.

To control for nonspecific effects of rTMS, we used a number judgment task matched in difficulty to the semantic task (Pobric et al., 2007). Subjects saw a probe number and three numerical choices and selected the number closest in value to the probe. There were 100 trials. Following the experiment, we split the number judgment trials into easy and hard trials based on the mean reaction time (RT) for each trial. This was to ensure that we had a set of easy control trials matched in RT to the concrete words and a set of harder control trials matched to the abstract words.

Design.

A within-subject factorial design was used with three factors: TMS (before vs after VLPFC stimulation), task (synonym judgment with context vs synonym judgment without context vs number judgment), and concreteness/difficulty (concrete vs abstract synonym trials and easy vs hard number trials). We used the virtual lesion stimulation method, in which a baseline level of behavioral performance is first obtained, then rTMS is delivered offline (with no concurrent behavioral task) and behavioral performance is probed immediately following stimulation during the temporary refractory period induced by the TMS. Subjects began by completing a practice block of 20 trials for each condition. This was followed by baseline testing, in which subjects completed 50 trials in each condition. Synonym judgment conditions each contained 25 concrete and 25 abstract trials and the order of conditions was counterbalanced across participants. Subjects then received 10 min of 1 Hz rTMS (see below). Immediately following TMS, subjects completed another 50 trials in each condition. The assignment of trials to before or after TMS was counterbalanced across subjects. In addition, stimuli were counterbalanced such that each synonym judgment trial was seen with context by half of the subjects and without context by the other half.

Stimulation parameters.

Focal magnetic stimulation was delivered using a 50 mm figure-of-eight coil attached to a MagStim Rapid2 stimulator (Magstim). For every participant, motor threshold (MT) was determined before the experiment as the minimum stimulation level that reliably induced a visible twitch in the relaxed contralateral abductor pollicis brevis muscle. Stimulation was set at 120% of MT. Average MT was 56% of the maximal stimulator output and the average stimulation intensity during rTMS was 66%. In selecting which area within VLPFC to stimulate, we were guided by the area of maximal lesion overlap in the patient group and a recent fMRI study that used a similar synonym judgment task to ours (Binney et al., 2010). This indicated a large cluster of activation in VLPFC with a peak in BA 45 at MNI coordinates −54, 24, 3 (Fig. 2). Structural T1-weighted MRI scans were obtained for each subject and the target coordinates converted into each subject's native space using SPM5. To locate this site in each subject, their T1-weighted scan was coregistered with their scalp using an Ascension minibird magnetic tracking system and MRIreg software (http://www.cabiatl.com/mricro/mricro/mrireg/index.html). Eight fiducial markers present during the scan (oil capsules attached to nasion, vertex, inion, tip of the nose, left/right mastoids, and left/right tragus during scanning) were used during the coregistration process.

The coil was held securely over the site to be stimulated and oriented to produce minimum discomfort to the subject. Particular care was taken in the placing of the coil because TMS over frontal regions can be more uncomfortable than over occipital or parietal areas. Subjects received TMS stimulation for 10 min (1 Hz for 600 s at 120% MT). This protocol has been shown to produce behavioral effects that last for several minutes following stimulation (Kosslyn et al., 1999; Hilgetag et al., 2001).

Results

Neuropsychological study

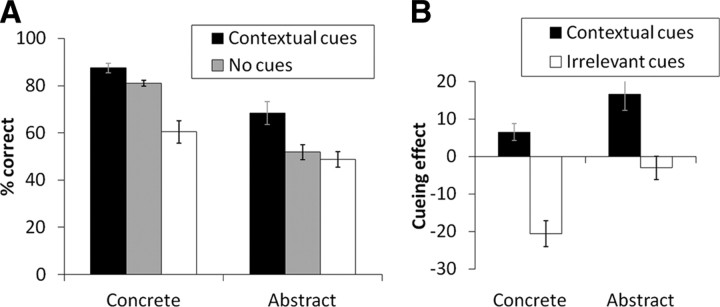

Correct responses in each condition are shown in Figure 3A. We performed a 2 × 3 (imageability × cue type, contextual cue vs no cue vs irrelevant cue) within-subjects ANOVA, which revealed main effects of imageability (F(1,5) = 46.2, p = 0.001) and cue type (F(2,10) = 25.2, p < 0.001) as well as an interaction (F(2,10) = 5.26, p < 0.05). Overall, concrete words were better comprehended than abstract words. Post hoc tests indicated that performance on trials with a contextual cue was better than those with no cue (t(5) > 5.5, p < 0.005) whereas trials featuring irrelevant cues were comprehended more poorly than those with no cue (t(5) = 3.2, p < 0.05). As indicated by the significant interaction shown in Figure 3B, cueing effects differed for concrete versus more abstract words. For the more abstract words, patients performed better when given a contextual cue (contextual cue vs no cue, t(5) = 5.0, p = 0.004) whereas the negative effect of irrelevant cues did not reach statistical significance (no cue vs irrelevant cue, t(5) = 2.36, p = 0.065). In contrast, the effect of contextual cues was less pronounced for the highest imageability words (t(5) = 2.75, p = 0.04) but irrelevant cues had a highly significant negative effect on performance (t(5) = 5.33, p = 0.003). Finally, a 2 × 2 (imageability × cue type) ANOVA was performed on the contextual cue and no cue data, excluding the irrelevant cue condition. There was again an interaction (F(1,5) = 6.11, p = 0.056), confirming that the positive effect of contextual cues differed for concrete and abstract words.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Results of neuropsychological study. A, Proportion of correct responses in each condition. B, Effect of contextual and irrelevant cues, relative to no cue condition, calculated by subtracting accuracy in the no-cue condition from accuracy in contextual cue and irrelevant cue conditions. Bars indicate SE of mean, adjusted to reflect the between-condition variance used in repeated-measure designs (Loftus and Masson, 1994).

Analyses performed on individual patients' data revealed a similar pattern. Five of six patients benefited from contextual cues when comprehending more abstract words (McNemar one-tailed p < 0.06), whereas only one patient showed this effect for concrete words (patient LS, p = 0.05). Conversely, irrelevant cues had a negative effect on four patients for concrete words (p < 0.02) but only two patients showed a similar effect for abstract words (patients KA and NY, p < 0.06).

Summary

Patients with VLPFC damage showed poorer comprehension of abstract relative to concrete words. In line with their deficit in executive regulation of semantic knowledge, their comprehension improved significantly when they were provided with a contextual cue that reduced ambiguity in word meaning. As predicted by the context availability theory, these cues boosted comprehension of abstract words to a greater extent than concrete words, reducing the difference between the two word types. Irrelevant sentences, on the other hand, had a particularly detrimental effect on concrete word comprehension. This may be because they activated competing semantic information that interfered with the otherwise simple process of retrieving concrete word meanings. In effect, the presentation of irrelevant cues induced similar executive demands to those inherently posed by more semantically variable abstract words.

rTMS Study

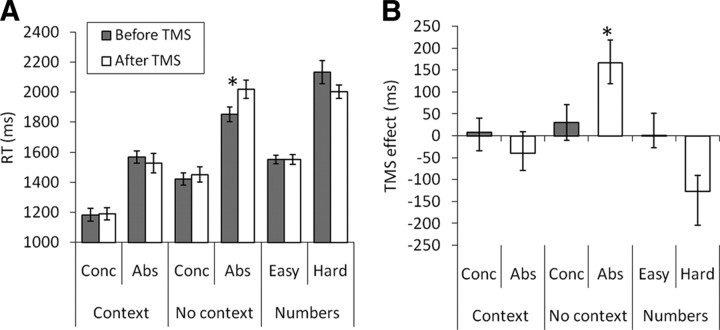

Reaction times in each condition are summarized in Figure 4. Outliers more than three SDs from a subject's mean in any condition were removed (1.0% of trials). A within-subjects ANOVA was conducted that included task (no context vs with context vs numbers), condition (concrete/easy vs abstract/hard), and TMS as factors. This revealed main effects of task (F(2,24) = 33.8, p < 0.001) and condition (F(1,12) = 160, p < 0.001). There was also a task × condition interaction (F(2,24) = 4.29, p < 0.05). There was no main effect of TMS but there was a task × TMS interaction (F(2,24) = 6.52, p = 0.005) and, critically, a three-way interaction between task, condition, and TMS (F(2,24) = 4.16, p < 0.05). Post hoc t tests indicated that the TMS slowed responses for abstract words only, and only when these were presented with no sentential context (t(12) = 2.2, p < 0.05). TMS had no effect on the number judgment task; in fact there was a nonsignificant trend toward faster responses after TMS for the harder stimuli (t(12) = 1.86, p = 0.09). This might reflect greater familiarity with the task post-TMS. We also performed a separate analysis of the synonym judgment data following TMS. As expected, this revealed main effects of context (F(1,12) = 35.4, p < 0.001) and imageability (F(1,12) = 126, p < 0.001). Subjects were faster to respond to concrete words and faster when provided with context. There was also an interaction (F(1,12) = 6.72, p < 0.05), indicating that context benefited abstract words more than concrete. In the pre-TMS data, the same main effects were present but there was no interaction (F < 1), suggesting that the contextual dependence of abstract words was heightened following TMS.

Figure 4.

Results of rTMS study. A, Reaction times before and after rTMS in each condition. B, Difference between pre-TMS and post-TMS reaction times for each condition. *, Significant TMS effect (paired-samples t test; p < 0.05). Bars indicate SE of mean, adjusted to reflect the between-condition variance used in repeated-measure designs (Loftus and Masson, 1994). Conc, Concrete; Abs, abstract.

Error data for the three tasks were analyzed in the same manner as the RT data. There were main effects of condition (F(2,24) = 10.3, p = 0.001) and task (F(2,24) = 25.9, p < 0.001) and an interaction (F(2,24) = 7.84, p = 0.002), mirroring the results in RT (more errors for abstract words and words without context). However, there was no main effect of TMS or interactions with TMS, indicating that the TMS effect was observed solely in RTs.

Summary

rTMS to left VLPFC selectively slowed comprehension of abstract words but only when these were presented without contextual cues. When words with preceded by a contextual cue that reduced the executive demands of comprehension, rTMS had no effect on reaction times. Overall, subjects took longer to respond to the uncued abstract words than to other conditions in the semantic task, raising the possibility that VLPFC involvement is not specific to abstract words and, instead, is simply a general response to task difficulty (Binder et al., 2005). This interpretation can be ruled out on the basis that the hard number judgment trials were unaffected by TMS, despite being even more demanding in terms of reaction times. Instead, the TMS effect appeared to be a consequence of the additional executive control requirements of focusing on a specific meaning of semantically variable abstract words.

Discussion

The neural basis of abstract word comprehension is poorly understood. Although neuroimaging studies reliably reveal more VLPFC activation for abstract relative to concrete words (Binder et al., 2009), it is not clear how this should be interpreted. Here, we used a convergent combination of neuropsychology and rTMS to test the hypothesis that VLPFC is involved in comprehending abstract words because their meanings are inherently variable and executive control is needed to select the appropriate interpretation for the task at hand (Fiebach and Friederici, 2004; Bedny and Thompson-Schill, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2010). Patients with left VLPFC lesions showed poorer comprehension of abstract words relative to concrete when they were presented without a specific context. However, when preceded by a sentence cue that provided a context in which to interpret the word, abstract word comprehension was significantly boosted, since the executive demands of selecting an appropriate meaning were reduced. We found a similar result when healthy subjects received rTMS to left VLPFC. Reaction times for abstract words were slowed but only when they were presented without context. These results indicate that VLPFC is important for processing abstract words when competition between different possible interpretations must be resolved, in keeping with the role of this region in resolving lexical–semantic ambiguity (Rodd et al., 2005; Bedny et al., 2007; Zempleni et al., 2007) and in the executive regulation of semantic knowledge more generally (Fiez, 1997; Thompson-Schill et al., 1997, 1998; Badre et al., 2005; Jefferies and Lambon Ralph, 2006; Noonan et al., 2010).

These findings are in line with the context availability theory, which states that abstract words are more difficult to process because they do not readily bring to mind a specific context (Schwanenflugel and Shoben, 1983). Some previous studies have dismissed this view on the basis that if concrete words activate more detailed contextual information then they should also produce greater activation in the brain, whereas in fact abstract words tend to produce more activation (Binder et al., 2005; Sabsevitz et al., 2005). However, if one assumes that the lack of a strongly associated context necessitates greater executive regulation then this puzzle is easily resolved, since the additional activation observed for abstract words can be attributed to control processes. As we have demonstrated here, the involvement of VLPFC is inversely related to the amount of contextual information available, supporting this interpretation.

An alternative perspective on concreteness effects is provided by dual-coding theory, which states that the meanings of abstract words are determined primarily by their associations with other words, whereas concrete words are also coded in terms of multimodal sensory experiences (Paivio, 1986). The dual-coding explanation of VLPFC activation—that it is a store for verbal semantic representations—provides no explanation for the contextual dependence of VLPFC effects observed here. Verbal semantic information must be accessed to comprehend abstract words, regardless of whether a context is provided. Although dual coding cannot explain the context-based effects in this study, it is likely that concrete–abstract differences in other brain regions reflect differences in the types of experience we have with these words. The anterior superior temporal sulcus, for example, is often active in abstract word processing (Noppeney and Price, 2004; Sabsevitz et al., 2005; Binder et al., 2009) and is also heavily involved in comprehending speech (Scott et al., 2000; Sharp et al., 2004; Hickok and Poeppel, 2007). This might reflect the greater reliance of abstract words on verbal associative information to determine their meaning. In contrast, posterior ventral temporal lobe activations are commonly reported for concrete words (Wise et al., 2000; Sabsevitz et al., 2005; Binder et al., 2009) and this area has been linked to processing of the visual features of objects (Chao et al., 1999; Martin, 2007).

Although this study was concerned with the role played by VLPFC in regulating semantic information, it is likely that other regions also contribute to this function. Neuroimaging studies of semantic control often reveal posterior temporal and inferior parietal activations in addition to VLPFC, as discussed by Noonan et al. (2010). Moreover, although patients with semantic control deficits often present with VLPFC damage, very similar deficits can occur as a result of temporoparietal lesions (Jefferies and Lambon Ralph, 2006; Noonan et al., 2010). It is likely that the VLPFC and temporoparietal region form a distributed network for regulation of semantic knowledge. A similar network has been proposed for domain-general cognitive control (Peers et al., 2005; Collette et al., 2006; Nagel et al., 2008).

In addition to the theoretical issues addressed in this study, it is noteworthy because we took the novel methodological approach of testing the same hypothesis using two complementary neuroscience techniques. Neuropsychology and rTMS each have their own sets of inherent advantages and limitations. One advantage shared by both is that, unlike functional neuroimaging studies, they test the effects of disruption to an area of cortex, allowing inferences as to whether the region is necessarily involved in a particular task (Price and Friston, 2002). The two techniques diverge, however, with respect to the size of the behavioral effects they produce and the degree of neuroanatomical specificity they afford. Brain lesions can have striking and robust effects on behavior. As a consequence, neuropsychological studies have often provided highly influential demonstrations of cognitive phenomena and have acted as a starting point for the development of cognitive theories (Scoville and Milner, 1957; Warrington and Shallice, 1969; Warrington, 1975). Effect sizes in patients are typically large and stable, meaning that the factors underlying their deficits can be investigated with relative ease. One of the reasons for this is that patients' lesions are often sufficiently large that they affect an entire functional area, producing a marked effect on tasks that depend on it. The disadvantage of this widespread damage is that it can be difficult to localize which region within the damaged tissue is responsible for the deficit. In rTMS, conversely, a single, specific region can be targeted precisely (studies typically report a spatial resolution of up to 1 cm) (Walsh and Rushworth, 1999). This focal stimulation is spatially precise but has much more subtle effects on cognitive processing (typically observed only in reaction times). This may be because stimulation is limited to part of a functional region and unstimulated tissue within the region can compensate. It is also, of course, because the neurophysiological effects of TMS are much milder than those of stroke or other forms of pathology. Whatever the reason, a researcher can find that reliable behavioral effects of TMS are somewhat elusive and small changes to the task or materials can determine whether an effect is observed. By combining neuropsychology and rTMS in the present study, we took the best of both worlds. This convergent approach confirmed that the necessary involvement of VLPFC in the comprehension of abstract words was due to their executively demanding and context-dependent meanings.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust project grant (078734/Z05/Z) and by a National Institute for Health Research senior investigator grant to M.A.L.R. We thank the patients and their caregivers for their generous assistance with this study.

References

- Adlam AL, Patterson K, Bozeat S, Hodges JR. The Cambridge semantic memory test battery: detection of semantic deficits in semantic dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Neurocase. 2010;16:193–207. doi: 10.1080/13554790903405693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badre D, Poldrack RA, Paré-Blagoev EJ, Insler RZ, Wagner AD. Dissociable controlled retrieval and generalized selection mechanisms in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2005;47:907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedny M, Thompson-Schill SL. Neuroanatomically separable effects of imageability and grammatical class during single-word comprehension. Brain Lang. 2006;98:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedny M, Hulbert JC, Thompson-Schill SL. Understanding words in context: the role of Broca's area in word comprehension. Brain Res. 2007;1146:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Westbury CF, McKiernan KA, Possing ET, Medler DA. Distinct brain systems for processing concrete and abstract concepts. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17:905–917. doi: 10.1162/0898929054021102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL. Where is the semantic system?: A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2767–2796. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binney RJ, Embleton KV, Jefferies E, Parker GJM, Lambon Ralph MA. The ventral and inferolateral aspects of the anterior temporal lobe are crucial in semantic memory: evidence from a novel direct comparison of distortion-corrected fMRI, rTMS and semantic dementia. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2728–2738. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat S, Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K, Garrard P, Hodges JR. Non-verbal semantic impairment in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess P, Shallice T. The Hayling and Brixton tests. Suffolk, England: Thames Valley Test Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chao LL, Haxby JV, Martin A. Attribute-based neural substrates in temporal cortex for perceiving and knowing about objects. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:913–919. doi: 10.1038/13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collette F, Hogge M, Salmon E, Van der Linden M. Exploration of the neural substrates of executive functioning by neuroimaging. Neuroscience. 2006;139:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M. The MRC psycholinguistic database quarterly. J Exp Psychol. 1981;33:497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett F, Jefferies E, Ehsan S, Lambon Ralph MA. Different impairments of semantic cognition in semantic dementia and semantic aphasia: evidence from the non-verbal domain. Brain. 2009;132:2593–2608. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Matthews PM, Rushworth MF. Semantic processing in the left inferior prefrontal cortex: a combined functional magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15:71–84. doi: 10.1162/089892903321107837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebach CJ, Friederici AD. Processing concrete words: fMRI evidence against a specific right-hemisphere involvement. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:62–70. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiez JA. Phonology, semantics, and the role of the left inferior prefrontal cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 1997;5:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough PM, Nobre AC, Devlin JT. Dissociating linguistic processes in the left inferior frontal cortex with transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8010–8016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2307-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgetag CC, Théoret H, Pascual-Leone A. Enhanced visual spatial attention ipsilateral to rTMS-induced ‘virtual lesions’ of human parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:953–957. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P, Rogers TT, Lambon Ralph MA. Semantic diversity accounts for the “missing” word frequency effect in stroke aphasia: insights using a novel method to quantify contextual variability in meaning. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1162/jocn.2011.21614. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies E, Lambon Ralph MA. Semantic impairment in stroke aphasia vs. semantic dementia: a case-series comparison. Brain. 2006;129:2132–2147. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies E, Baker SS, Doran M, Lambon Ralph MA. Refractory effects in stroke aphasia: a consequence of poor semantic control. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies E, Patterson K, Jones RW, Lambon Ralph MA. Comprehension of concrete and abstract words in semantic dementia. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:492–499. doi: 10.1037/a0015452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslyn SM, Pascual-Leone A, Felician O, Camposano S, Keenan JP, Thompson WL, Ganis G, Sukel KE, Alpert NM. The role of Area 17 in visual imagery: convergent evidence from PET and rTMS. Science. 1999;284:167–170. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus GR, Masson ME. Using confidence intervals in within-subject designs. Psychon Bull Rev. 1994;1:476–490. doi: 10.3758/BF03210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. The representation of object concepts in the brain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:25–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner B. Effects of different brain lesions on card sorting: the role of the frontal lobes. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel IE, Schumacher EH, Goebel R, D'Esposito M. Functional MRI investigation of verbal selection mechanisms in lateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2008;43:801–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan KA, Jefferies E, Corbett F, Lambon Ralph MA. Elucidating the nature of deregulated semantic cognition in semantic aphasia: evidence for the roles of the prefrontal and temporoparietal cortices. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:1597–1613. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noppeney U, Price CJ. Retrieval of abstract semantics. Neuroimage. 2004;22:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Mental representations: a dual-coding approach. Oxford: Oxford UP; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Peers PV, Ludwig CJ, Rorden C, Cusack R, Bonfiglioli C, Bundesen C, Driver J, Antoun N, Duncan J. Attentional functions of parietal and frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1469–1484. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobric G, Jefferies E, Lambon Ralph MA. Anterior temporal lobes mediate semantic representation: Mimicking semantic dementia by using rTMS in normal participants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20137–20141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707383104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Friston KJ. Degeneracy and cognitive anatomy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:416–421. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JC. Coloured progressive matrices sets A, AB, B. London: H. K. Lewis; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Rodd JM, Davis MH, Johnsrude IS. The neural mechanisms of speech comprehension: fMRI studies of semantic ambiguity. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1261–1269. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behav Neurol. 2000;12:191–200. doi: 10.1155/2000/421719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabsevitz DS, Medler DA, Seidenberg M, Binder JR. Modulation of the semantic system by word imageability. Neuroimage. 2005;27:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffran EM, Bogyo L, Schwartz MF, Marin OSM. Does deep dyslexia reflect right hemisphere reading? In: Coltheart M, Marshall JC, Patterson KE, editors. Deep dyslexia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1980. pp. 361–406. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Harnishfeger KK, Stowe RW. Context availability and lexical decisions for abstract and concrete words. J Mem Lang. 1988;27:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Shoben EJ. Differential context effects in the comprehension of abstract and concrete verbal materials. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1983;9:82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Scott SK, Blank CC, Rosen S, Wise RJ. Identification of a pathway for intelligable speech in the left temporal lobe. Brain. 2000;123:2400–2406. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp DJ, Scott SK, Wise RJ. Retrieving meaning after temporal lobe infarction: the role of the basal language area. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:836–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Schill SL, D'Esposito M, Aguirre GK, Farah MJ. Role of left inferior prefrontal cortex in retrieval of semantic knowledge: a reevaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14792–14797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Schill SL, Swick D, Farah MJ, D'Esposito M, Kan IP, Knight RT. Verb generation in patients with focal frontal lesions: a neuropsychological test of neuroimaging findings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15855–15860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh V, Rushworth M. A primer of magnetic stimulation as a tool for neuropsychology. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK. The selective impairment of semantic memory. Q J Exp Psychol. 1975;27:635–657. doi: 10.1080/14640747508400525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK, James M. The visual object and space perception battery. Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk: Thames Valley Test Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington EK, Shallice T. The selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. Brain. 1969;92:885–896. doi: 10.1093/brain/92.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler memory scale: revised (WMS-R) New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wise RJ, Howard D, Mummery CJ, Fletcher P, Leff A, Büchel C, Scott SK. Noun imageability and the temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:985–994. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempleni MZ, Renken R, Hoeks JC, Hoogduin JM, Stowe LA. Semantic ambiguity processing in sentence context: evidence from event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1270–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]