Goult et al. propose that talin acts as series of mechanochemical switches to form a mechanosensitive signaling hub that integrates adhesion signaling.

Abstract

Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM), mediated by transmembrane receptors of the integrin family, is exquisitely sensitive to biochemical, structural, and mechanical features of the ECM. Talin is a cytoplasmic protein consisting of a globular head domain and a series of α-helical bundles that form its long rod domain. Talin binds to the cytoplasmic domain of integrin β-subunits, activates integrins, couples them to the actin cytoskeleton, and regulates integrin signaling. Recent evidence suggests switch-like behavior of the helix bundles that make up the talin rod domains, where individual domains open at different tension levels, exerting positive or negative effects on different protein interactions. These results lead us to propose that talin functions as a mechanosensitive signaling hub that integrates multiple extracellular and intracellular inputs to define a major axis of adhesion signaling.

Introduction

Cell adhesion to the ECM is fundamental to multicellular life. Deletion of major integrins or ECM proteins impairs the development and survival of multicellular organisms (Danen and Sonnenberg, 2003; Dzamba and DeSimone, 2018). It is a requirement for cell cycle progression of normal mammalian cells and survival of most normal cell types. Integrins comprise the main family of ECM receptors (Hynes, 1992) and are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via multicomponent protein adhesion complexes of varying sizes and compositions, thus connecting intracellular and extracellular structures. Integrin-mediated adhesions sense the mechanical features of the matrix, including stiffness, texture, and externally applied strains, transducing these forces into biological signals (Iskratsch et al., 2014). They further serve as signaling hubs that coordinate multiple inputs to regulate cell behavior (Cabodi et al., 2010). Talin plays a central role in cell adhesion, first by converting integrins to high-affinity states (“activation”) and by coupling integrins to the cytoskeleton. Indeed, deletion of talin results in developmental defects in multiple organisms that resemble total loss of integrins (Monkley et al., 2000).

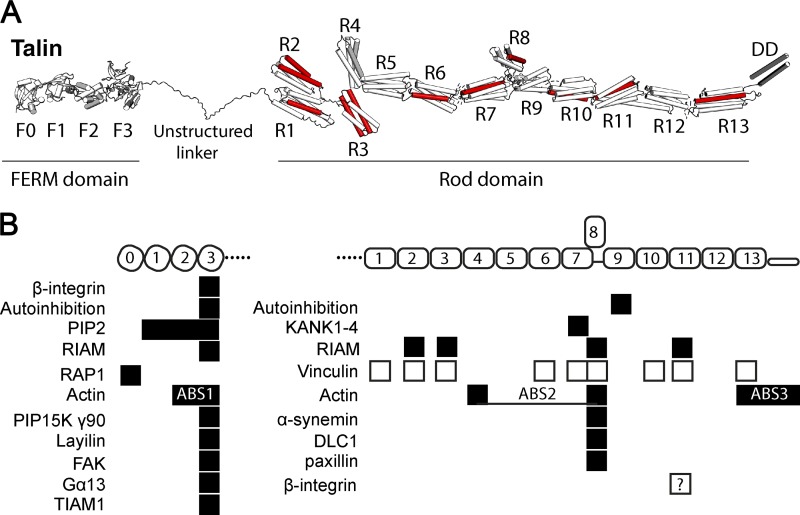

Talin is a large (270 kD) multidomain cytosolic protein (Fig. 1) that links integrins to F-actin in part via binding of its N-terminal FERM domain to integrin cytoplasmic domains as well as via two sites in its C-terminal flexible rod domain that bind F-actin (Calderwood et al., 2013). These binding events are followed by application of tension from actomyosin that acts on the talin rod, triggering recruitment of a second actin-binding protein, vinculin (Humphries et al., 2007; del Rio et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2014). This mechanism thus strengthens adhesions under tension, a form of mechanosensitivity (del Rio et al., 2009; Carisey et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Talin domain organization and interactions. (A) Talin contains an N-terminal FERM domain (F0–F3) connected via an 80-aa unstructured linker to the 13 talin rod domains R1–R13. 9 of the 13 rod domains contain VBSs (red). (B) Major binding sites for folded talin domains (black boxes) and unfolded domains (white boxes).

Despite the presence of the same core components, adhesion complexes are strikingly diverse. Highly dynamic transient adhesions enable cell migration; dynamic and proteolytic adhesions mediate invasion; stable adhesions promote tissue organization; and specialized myotendinous junctions transmit very high forces for animal movements. Around the central core of integrin, talin, and actin, numerous additional proteins show selective recruitment that vary widely between adhesion types (Winograd-Katz et al., 2014; Horton et al., 2015), likely reflecting distinct effector, signaling, and mechanosensing functions.

The purpose of this perspective is to summarize existing knowledge and propose a new view of talin function. It is therefore split into two sections: the first section reviews recent data on talin and the emerging functional implications, and the second, more speculative section proposes that there exists a “talin code” of force-dependent interactions with signaling proteins and cytoskeletal components, which exhibits some internal hierarchy. This view, where talin serves as a flexible mechanosensitive signaling hub (MSH), has the potential to explain diverse responses of cells to distinct mechanical stimuli on different time scales.

Talin interactions and functions

The multiple domains with numerous force-sensitive binding sites in talin, coupled with their linear arrangement in the path of force transmission (Fig. 1), provides opportunities for enormous functional flexibility. This section summarizes recent findings on talin interactions and functions in coordinating adhesion dynamics.

Adhesion dynamics

Regulated adhesion complex assembly and disassembly is vital for cell spreading and migration (Wehrle-Haller, 2012). In cells freshly plated on ECM or in rapidly migrating cells, activated integrins form small clusters under the lamellipodia. These small adhesions can either rapidly disassemble or can connect to larger actin templates and mature into slightly larger, more stable structures called focal complexes (Bachir et al., 2014; Changede et al., 2015), which themselves either disassemble or further mature into much larger adhesive structures including focal adhesions (FAs; e.g., in contractile cells on rigid substrates), podosomes (in activated cells on soft substrates), or very stable adhesions as in myocytes or myofibroblasts (in highly contractile cells on rigid substrates; Yu et al., 2013; Changede et al., 2015). In all cases, talin is a major player in force-dependent adhesion growth and stabilization (Giannone et al., 2003; Critchley, 2009; Kanchanawong et al., 2010; Austen et al., 2015; Changede et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2016). Indeed, cardiac and skeletal muscle express an alternatively spliced β1-integrin (β1D) with increased affinity for talin, a key event in exertion of ultra-high forces (Belkin et al., 1996; Anthis et al., 2010).

Force transmission between actin and integrins at the leading edges of migrating or spreading cells is mediated by a unique, dynamic mechanism in which talin plays a central role. Actin polymerizes at cell edges and flows rearwards, pushed by the force generated by polymerization and/or pulled by myosin motors further back in the cell (Ponti et al., 2004; Gupton and Waterman-Storer, 2006). This retrograde flow of actin couples to integrins via talin, thereby exerting traction force on the matrix or substrate for spreading, migration, or contraction. This force transfer must occur through highly dynamic bonds that exhibit variable coupling efficiency: the so-called FA clutch (Case et al., 2015).

Talin conformation and mechanotransduction

There are two talin isoforms, talins 1 and 2, that are 76% identical and have identical domain structure (Debrand et al., 2009). Both contain an N-terminal FERM domain containing four globular segments (F0 to F3), a disordered linker region, and a C-terminal rod with 13 four- and five-helix bundles (R1 to R13; Goult et al., 2013) terminating in a single α-helix that mediates homodimerization (dimerization domain [DD]; Fig. 1). With the exception of R8, which is positioned outside the force transmission pathway as will be discussed, the rod domains are arranged linearly like beads on a string, transmitting tension along the talin rod. At least 9 of the 13 rod domains contain cryptic vinculin-binding sites (VBSs; Gingras et al., 2005) that are exposed when unfolded by mechanical force, allowing vinculin binding and adhesion reinforcement. Talin is autoinhibited by an interaction between the head (F3) and R9, which must be released for actin and integrin binding and recruitment to FAs (Goksoy et al., 2008; Goult et al., 2009; Song et al., 2012; Ellis et al., 2013). Interaction of talin with negatively charged phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate of the plasma membrane inner leaflet also contributes to talin activation and membrane association (Saltel et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2016).

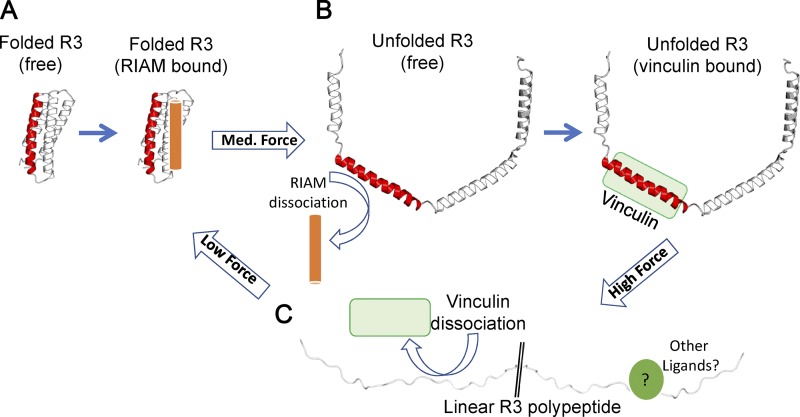

Force-dependent switching of binding partners to the R3 rod domain defines a mechanochemical switch

The best-studied talin activation pathway depends on the small GTPase Rap1, whose effector Rap1-GTP–interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM) binds directly to talin via a high-affinity RIAM binding site in R2–R3 (note that talin R8 and R11 also contain RIAM-binding sites [Goult et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2014] and that Rap1 has been shown to bind directly to talin F0 [Goult et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2017]). Rap1/RIAM recruits talin to the plasma membrane (Han et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009) and antagonizes talin autoinhibition to promote integrin and actin binding. Importantly, RIAM engages folded talin R3 (Fig. 2; Goult et al., 2013). R3 is the least stable of the 13 talin rod domains due to a cluster of four threonines in the central hydrophobic core of the four-helix bundle (Fillingham et al., 2005; Goult et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2014). Consequently, R3 opens under the relatively low force of 5 pN, converting the folded four-helix bundle into a string of helices that could be further unfolded into a disordered conformation. This transition exposes two high-affinity VBSs, which in the absence of force, were cryptic, buried inside the core of the folded R3. Therefore, force-dependent unfolding of R3 results in exposure of VBS-recruiting vinculin while simultaneously disrupting RIAM binding, severing the link to Rap1 signaling. This switch in ligands is mirrored in cells, where an integrin–talin–RIAM complex at the tip of cell protrusions (“sticky fingers”) is replaced by an integrin–talin–vinculin complex in mature, high-tension FAs, which are devoid of RIAM (Lagarrigue et al., 2015). This exchange of RIAM, bound to talin in the absence of force for vinculin in the presence of forces, thus defines a mechanochemical switch (Fig. 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

Talin rod domains as mechanochemical switches. (A–C) Each talin rod domain can adopt a number of conformations under different force regimes. (A) Folded bundle at low force. (B) Unfolded string of helices at forces above the mechanical threshold. (C) A fully unfolded polypeptide at high forces. Force-induced domain unfolding leads to a switch in the ligand binding profile of that domain. Complete unfolding at high force will result in a linear polypeptide unable to bind folded-domain ligands or helix-binding ligands. While no ligands for this form have been identified so far, many proteins bind linear peptide motifs.

Structural basis for talin rod interactions

To date, there have been no comprehensive proteomic analyses of the talin interactome; however, structural studies on ligands that bind talin rod domains have begun to reveal interesting themes. Deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC1), a RhoGAP and tumor suppressor, binds the talin R8 domain via an α-helical leucine–aspartic acid (LD) motif (Li et al., 2011; Alam et al., 2014). Elucidation of the structure of the DLC1–talin complex (Zacharchenko et al., 2016) revealed a helix-addition mechanism with an amphipathic LD helix of DLC1 packed between two adjacent helices on the surface of the R8 four-helix bundle, effectively converting it to a five-helix bundle. These findings led to the realization that the talin-binding sequence (TBS) in RIAM is also an LD motif as well as the identification of paxillin, which has several LD motifs, as a novel talin ligand (Zacharchenko et al., 2016). R8 is structurally similar to the FAK FA targeting (FAT) domain, a four-helix bundle that also binds LD motifs (Hoellerer et al., 2003). Another class of LD motif–containing proteins, the KANKs (kidney ankyrin repeat containing), bind to talin R7, a five-helix bundle (Bouchet et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b), and mediate connections of microtubules to adhesion complexes. Five-helix-bundle LD motif recognition is also shown with RIAM TBS1 binding the R11 five-helix bundle (Goult et al., 2013). Helix addition thus appears to be a general mechanism for binding to talin rod domain helix bundles in their folded state.

Binding to folded talin rod domains is not, however, limited to LD motifs. Talin autoinhibition involves the F3 domain of talin, a phosphotyrosine binding domain binding to R9 (Goult et al., 2009; Song et al., 2012). Thus, talin rod domains can interact with proteins via a variety of different mechanisms.

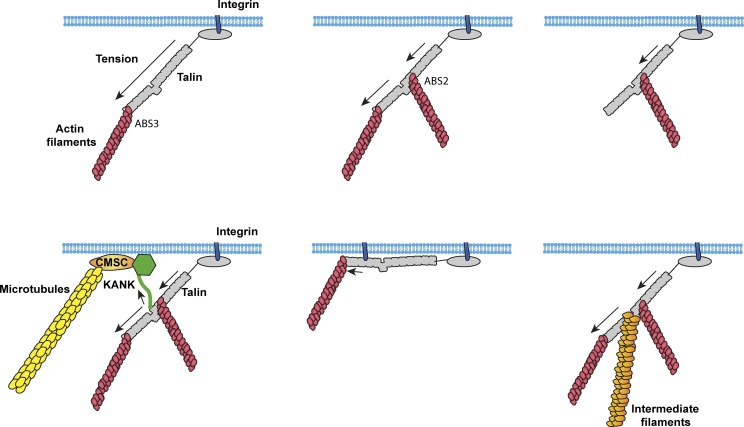

Mechanical constraints on talin

Talin contains three actin-binding sites (ABSs; Hemmings et al., 1996), with ABS1 in the N-terminal FERM domain (Lee et al., 2004), ABS2 spanning R4–R8 (Atherton et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2016) in the center of the rod domain, and ABS3 in R13-DD at the C terminus (Fig. 1; McCann and Craig, 1997; Gingras et al., 2008). This introduces the possibility of multiple paths of force transmission (Fig. 3). Indeed, studies in Drosophila melanogaster strongly suggest that talin adopts distinct conformations in cell types with different cytoskeletal–ECM linkages (Klapholz et al., 2015). In cultured cells, the initial linkage is thought to involve the talin FERM domain bound to integrin and the C-terminal ABS3 bound to actin (Gingras et al., 2008; Kopp et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2016; Ciobanasu et al., 2018). Adhesion maturation is accompanied by engagement of ABS2 with actin (Atherton et al., 2015), and mutational studies implicate ABS2 as the major site required for force transmission (Kumar et al., 2016). Whether ABS3 and ABS2 can be simultaneously bound to actin is unknown but seems plausible. These linkages imply the potential for distinct mechanical and conformational dynamics. Talin anchored to integrins via the FERM domain and to actin via ABS3 will subject the entire rod to tension; talin anchored through the FERM domain and ABS2 will only subject R1–R8 to tension; and talin anchored through ABS2 and ABS3 would subject R9–R12 domains to mechanical tension (Fig. 3). A further consideration of the mechanical constraints on talin arises from the additional linkages vinculin can make to actin filaments. These vinculin-mediated connections between talin and actin likely exert additional force vectors on talin, adding further context-dependent complexity to conformational arrangements adopted by talin.

Figure 3.

Talin as an MSH. Talin contains multiple linkages to the actin cytoskeleton and also links to microtubules (Bouchet et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b) and intermediate filaments (Sun et al., 2008). Depending on the cytoskeletal linkages engaged, different domains will be under tension, resulting in different sets of bound ligands and different signaling outputs.

The talin rod acts as a series of mechanochemical switches

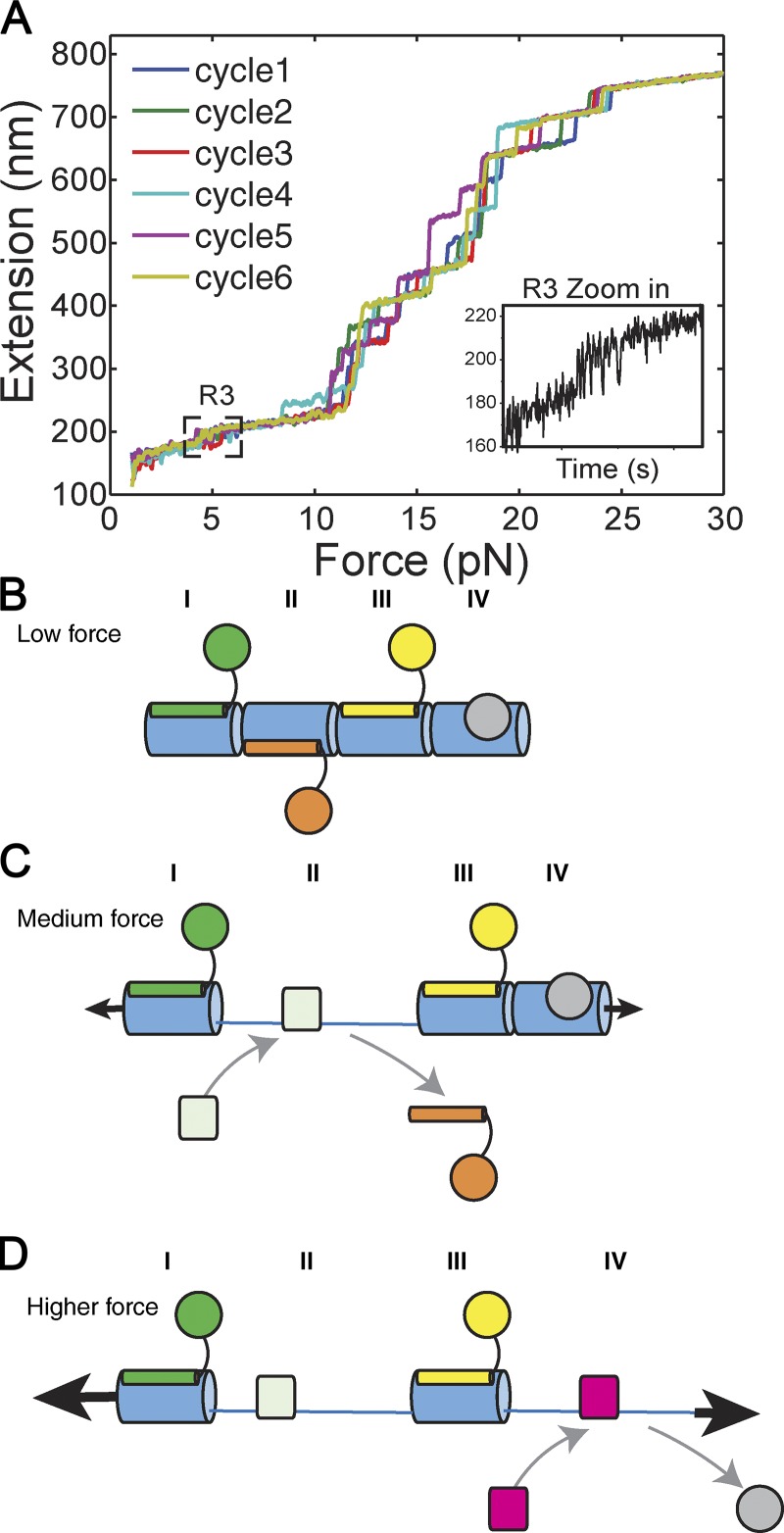

The mechanical stability of each domain in the talin rod has been analyzed using high-precision magnetic tweezers (Yao et al., 2016). Among the 13 rod domains, R3 is unique, not only because it unfolds under the lowest force, but also because it undergoes rapid equilibrium unfolding and refolding. This allows R3 to respond rapidly to changes in force (Yan et al., 2015). The two VBSs in R3 are the first to engage vinculin to initiate adhesion reinforcement. However, 9 of the other 12 talin rod domains contain one or more cryptic VBSs (Fig. 1), and stretching full-length talin in the presence of vinculin in vitro revealed that all 11 talin VBSs can be activated by stretching (Yao et al., 2016); indeed, vinculin binding to both N- and C-terminal regions of the talin rod has been observed in cells (Hu et al., 2016).

Examination of the full talin rod, R1–R13 (Yao et al., 2016), showed that all 13 rod domains exhibit fully reversible switch-like behavior, each one at a characteristic force level (Fig. 4). Indeed, unfolding of individual talin rod domains, when examined under a constant force loading rate (∼4 pN/s), required forces that varied by fivefold (5–25 pN). Further, all 13 talin rod domains rapidly refold to their respective original folded conformations once the force is reduced to <3 pN (Yao et al., 2016). In other words, each talin rod domain undergoes mechanochemical switching with a rate depending on the level of tension and the specific cytoskeletal connections. These mechanical and structural considerations gain support from single-molecule superresolution microscopic studies in cells. Using talin tagged with N- and C-terminal fluorophores, the distance between N and C termini was observed to be several times longer than the folded talin structure (Margadant et al., 2011). A substantial fraction of the bundles in talin rod (between one and nine domains; Yao et al., 2016) must therefore be unfolded in living cells.

Figure 4.

Talin as a series of mechanochemical switches. (A) The force-induced unfolding of the 13 talin rod domains R1–R13. Six force-extension curves are shown (at a loading rate of 3.8 pN/s), and each step in the profile corresponds with a single domain unfolding independently and undergoing mechanical switching. Adapted with permission from Yao et al. (2016). (B–D) Schematic diagram representing mechanochemical switches I–IV. (B) In the absence of mechanical force, the four domains are folded, and multiple ligands can bind simultaneously. (C) Mechanical force causes one domain (in this figure, domain II) to unfold, which drives a switch in binding partners on that domain. The other three domains remain folded and bound to their ligands. (D) Higher mechanical force causes a second domain (in this figure, domain IV) to unfold, switch binding partner, and further alter the signaling complex on that talin. Talin has 13 rod domains that exhibit this switch-like behavior, so multiple permutations of switch states and MSH complexes are possible on a single talin.

While ligands for all 13 domains have not yet been identified, we predict that all or most rod domains may bind one set of ligands when in the folded state and different ligands when unfolded. Vinculin, which binds to nine of the unfolded domains, is the canonical ligand for unfolded domains, but other ligands for unfolded domains seem likely. Discrete force-induced conformational changes in each domain would thus enable talin to recruit distinct cytoskeletal, adaptor, and signaling proteins dependent on mechanical tension, the nature of the cytoskeletal linkage, and the cell type–dependent expression of ligands (Fig. 4).

One further prediction is that binding of ligands to helix bundle domains will stabilize the state to which they are bound. This point has been demonstrated for vinculin, which stabilizes the open state of talin (Yao et al., 2014). Conversely, ligands bound to folded domains likely increase the tension required to unfold those domains. The ways in which talin structure and interactions introduce complexity into cellular mechanical responses are central to the notion of the talin MSH.

The mechanochemical switch in R7 controls microtubule targeting to adhesion sites

One example that illustrates this potential regulatory complexity is KANK-dependent microtubule association to adhesion complexes (Bouchet et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b). Microtubules do not stably associate with adhesion complexes, but cortical microtubules are captured and stabilized in their vicinity; these transient contacts mediate adhesion disassembly via endocytosis of the integrins and associated proteins (Stehbens et al., 2014). Microtubule stabilization and capture around FAs involves a cortical microtubule stabilization complex (CMSC), which comprises KANKs, the microtubule plus end–binding cytoplasmic linker–associated proteins (CLASPs; required for microtubule localization to FAs; Stehbens et al., 2014), and multiple other cortical adapters (Sun et al., 2016a; Bouchet and Akhmanova, 2017). The CMSC accumulates around FAs and stabilizes microtubule plus ends at the cell cortex (van der Vaart et al., 2013). The molecular link between the CMSC and FAs requires binding of the LD motif in KANK proteins to folded talin R7, which occurs in a thin rim around the FA outer edge (Fig. 3; Bouchet et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b). KANK1 was identified as a myosin-II–dependent component of adhesions (Kuo et al., 2011) consistent with tension-dependent microtubule targeting of adhesions (Kaverina et al., 2002). FAs thus exhibit a KANK-dependent spatially and mechanically regulated microtubule-targeting mechanism that is crucial for cell migration.

Cellular mechanosensing through the FA clutch

Multiple studies have identified a key role for talin in cellular sensing of the mechanical properties of the matrix and externally applied forces through the matrix/substrate (Sun et al., 2016a). Current models propose that the dynamic linkage between the matrix and actin—the FA “clutch”—mediates these processes, with talin rod domain unfolding a key element. The central notion here is that changes in substrate stiffness or externally applied forces alter the rate of force loading onto the bonds within the matrix–integrin–talin–actin pathway. These bonds are intrinsically dynamic, binding and unbinding rapidly to transmit force while allowing retrograde actin flow.

Forces often stabilize adhesions, suggestive of “catch bonds,” which paradoxically stabilize under tension. This behavior is quite rare in nature but is common in cytoskeletal and adhesive proteins, as befits proteins that evolved to transmit tension. Talin rod domain unfolding to allow vinculin binding and reinforcement of the actin connection is one mechanism of force-dependent strengthening, operating on time scales of 10s of seconds and longer. The integrin–ECM bond also exhibits tension-dependent stabilization on time scales of seconds or less (Kong et al., 2009, 2013). Importantly, matrix compliance and external forces modify the ongoing dynamics to control not only adhesion strength but also signaling outputs. A recently developed computational model linking the lifetime of the matrix–integrin–talin–actin connection to stiffness sensing closely related bond lifetimes to downstream signaling (Elosegui-Artola et al., 2017). In this model, the force-loading rate was the critical variable that controlled the lifetime of the bonds within adhesion complexes, thereby controlling multiple signaling outputs.

The FA clutch introduces a temporal aspect to the MSH model. Talin within the molecular clutch will undergo cycles of tension and release. We hypothesize that the duration of these cycles as well as the magnitude of the forces should determine which domains unfold or refold and which ligands are induced to bind or unbind during the cycles. Furthermore, these temporal features are predicted to determine the talin-dependent signaling outputs involved in mechanosensing through integrin-mediated adhesion.

Talin tension and adhesion assembly

Data from multiple approaches paint a picture in which adhesion assembly requires a series of progressive talin-mediated mechanosensitive events. These presumably begin when activated talin binds the integrin β-cytoplasmic domain via the talin FERM domain and actin via ABS3 (Fig. 3). The resultant tension on talin initially opens the R3 domain, which acts as a gatekeeper to adhesion assembly (Goult et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2014; Atherton et al., 2015; Elosegui-Artola et al., 2016). This conformational change has several consequences. First, it allows vinculin recruitment, strengthening the connection to actin and driving adhesion maturation (Atherton et al., 2016). Furthermore, ABS2 binds actin poorly in the absence of force, as it is inhibited by the adjacent rod domains R3 and R9 (Atherton et al., 2015). Force through ABS3 and unfolding of the R3 domain is thus expected to release this autoinhibition to activate ABS2. Doing so would also expose the VBS immediately adjacent to ABS2. Maintaining ABS2 in an inactive state until the initiation of adhesion assembly is likely important to prevent inadvertent high-affinity engagement with actin in the wrong place, keeping it cryptic until adhesion maturation.

Integrating these ideas with newer data from tension sensors (Kumar et al., 2016; Ringer et al., 2017) implies that distinct domains will be under tension at different stages of adhesion maturation. Tension may be lower in newer talin–actin linkages but will affect the entire length of the protein. Mature linkages appear to contain talin under higher tension but also tension that is mainly carried by ABS2; R9–R13 would then be under low/no tension and fully folded. These ideas lead to the hypothesis that talin in young versus old adhesions will be bound to a distinct set of ligands and transmit a distinct set of signals.

Nonmechanical signaling through the talin MSH

In addition to regulation by force, talin can be posttranslationally modified, including phosphorylation (Ratnikov et al., 2005), glycosylation (Hagmann et al., 1992), methylation (Gunawan et al., 2015), arginylation (Zhang et al., 2012), SUMOylation (Huang et al., 2018), and ubiquitination (Huang et al., 2009) on a number of sites (Gough and Goult, 2018). All of these will likely impact talin interactions and function. Intracellular pH is also well recognized as a second messenger that is precisely regulated by the sodium–protein antiporter and other ion transporters (Schönichen et al., 2013). Indeed, some of the first evidence that integrins can signal came from studies of intracellular pH (Schwartz et al., 1989, 1991). Local activation of the antiporter at sites of adhesion can result in local pH gradients, with the highest pH within the adhesions (Choi et al., 2013). Talin ABS3 binding to actin is strongly pH dependent (Srivastava et al., 2008), and other interactions may be as well. Talin interacts with moesin, which directly recruits sodium/hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE-1; Beaty et al., 2014), thus forming a key autoregulatory loop.

Further implications and speculations

Ligand interactions

The talin R8 rod domain is unique in two respects. First, R8 in its folded state appears to be particularly active in binding ligands, including RIAM, DLC1, actin, paxillin, and α-synemin (Calderwood et al., 2013). This characteristic may be related to its unique position in the talin rod as it is held outside the line of force via insertion into a loop in R7. Thus, it remains folded and able to bind ligands under relatively high tension (Gingras et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2016). However, multiple binding partners introduce additional possibilities. While individual ligand proteins might compete for the same binding site, the helix addition binding mechanism creates a distinct opportunity. Four- and five-helix bundles contain four or five interfaces between adjacent helices, each of which has the potential to bind ligands. Indeed, the FAK four-helix-bundle FAT domain can engage LD motif peptides on opposite faces (Hoellerer et al., 2003). Importantly, a ligand that binds to the folded state will stabilize the folded state required for other ligands. Under mechanical loads, binding of multiple ligands will thus be cooperative. Conversely, a ligand that stabilizes the unfolded state will facilitate binding by other unfolded state ligands. While it remains to be experimentally validated, this favors a scenario where individual talin domains might tend to have multiple ligands bound or else none. One particularly interesting but unanswered question is how actin binding is affected by domain unfolding and vinculin binding.

Temporal interactions

Talin rod domains exhibit hysteresis: forces of 10–15 pN at a force-loading rate of a few piconewtons per second may be required to induce unfolding, but refolding only occurs once force drops below ∼3 pN (Yao et al., 2016). One would predict that proteins like vinculin that bind the unfolded state should further stabilize the unfolded domains, essentially locking talin rod domains in an open conformation and further increasing hysteresis. Indeed, activated vinculin constructs stabilize adhesions to inhibition of myosin-dependent contractility (Humphries et al., 2007; Carisey et al., 2013). We speculate that this hysteresis effectively provides adhesions with “memory” of past forces: a talin that experiences a spike in force at some point will have unfolded rod domains that will not refold until force drops to <3 pN. In this way, early forces in adhesion development could imprint talin, locking domains in a given combination of folded and unfolded states that persist for longer times and influence signaling outputs.

A second form of temporal complexity derives from the fact that vinculin and probably other ligands for the unfolded state bind to a single talin α-helix in each bundle. If unengaged, these helices will completely unfold to random coils under rather low forces. This result implies that an exposed VBS helix that does not immediately engage vinculin can be pulled into a disordered conformation that inhibits vinculin engagement. Such effects introduce the potential for biphasic effects of force, and may be important, for example, in adhesion disassembly under high forces (Yao et al., 2014). Many protein–protein interactions are mediated by linear polypeptide motifs, suggesting that the fully unfolded linear form of the bundles may reveal additional binding sites for hitherto unknown ligands that can engage talin via this mode of binding.

Lastly, talin domain unfolding may impact the previously discussed force-loading rate that mediates molecular dynamics within the adhesions. Stochastic simulations based on the force-dependent unfolding and refolding rates of talin rod domains suggest that talin can act as a molecular “shock absorber” (Yao et al., 2016). This idea is based on the simple physical principle that unfolding of talin rod domains under tension should decrease the tension and slow the loading rate on other components in the mechanical chain. In contrast, refolding of the domains after tension decreases could slow the rate of tension decrease. This has important implications on all mechanosensitive interactions taking place along each talin molecule. These effects have the potential to alter the loading or unloading rate on talin and on the entire matrix–integrin–cytoskeleton assembly to affect the behavior of mechanosensitive (catch or slip) bonds.

Conclusion: The talin code

We envisage a talin molecule as a series of mechanochemical switches simultaneously decorated with numerous ligand proteins to form a signaling hub that we name the MSH. The talin MSH can integrate the magnitude and history of mechanical forces, the expression and activation state of ligand proteins, and its own posttranslational modifications to determine adhesion structure and signaling outputs. This role for talin fits with its high evolutionary conservation (Senetar and McCann, 2005), including the length of its rod domain and the universal presence of all 13 talin rod domains.

The ability of talin to parse diverse multiple inputs to determine robust, reproducible signaling responses leads us to view the role of talin as an MSH as a type of “code”; that is, a network of binding events organized in time and space that confers meaning in the form of signaling outputs. We propose that such a talin code enables cells to generate diverse adhesive structures with high fidelity. Deciphering the talin code in the face of multiple ligands, different force thresholds, and different structural configurations will require combining single-molecule approaches with systems biology to reveal and integrate vast amounts of information encodable within this network. While this task may seem daunting, we should remind ourselves that the cells figured it out some time ago.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mingxi Yao and David Critchley for stimulating discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

B.T. Goult is funded by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/N007336/1; J. Yan is funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF), Prime Minister's Office, Singapore, under its NRF Investigatorship Program (NRF Investigatorship Award No. NRF-NRFI2016-03); and B.T. Goult and J. Yan are funded by Human Frontier Science Program grant (RGP00001/2016).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alam T., Alazmi M., Gao X., and Arold S.T.. 2014. How to find a leucine in a haystack? Structure, ligand recognition and regulation of leucine-aspartic acid (LD) motifs. Biochem. J. 460:317–329. 10.1042/BJ20140298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthis N.J., Wegener K.L., Critchley D.R., and Campbell I.D.. 2010. Structural diversity in integrin/talin interactions. Structure. 18:1654–1666. 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton P., Stutchbury B., Wang D.-Y., Jethwa D., Tsang R., Meiler-Rodriguez E., Wang P., Bate N., Zent R., Barsukov I.L., et al. 2015. Vinculin controls talin engagement with the actomyosin machinery. Nat. Commun. 6:10038 10.1038/ncomms10038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton P., Stutchbury B., Jethwa D., and Ballestrem C.. 2016. Mechanosensitive components of integrin adhesions: Role of vinculin. Exp. Cell Res. 343:21–27. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austen K., Ringer P., Mehlich A., Chrostek-Grashoff A., Kluger C., Klingner C., Sabass B., Zent R., Rief M., and Grashoff C.. 2015. Extracellular rigidity sensing by talin isoform-specific mechanical linkages. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:1597–1606. 10.1038/ncb3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachir A.I., Zareno J., Moissoglu K., Plow E.F., Gratton E., and Horwitz A.R.. 2014. Integrin-associated complexes form hierarchically with variable stoichiometry in nascent adhesions. Curr. Biol. 24:1845–1853. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty B.T., Wang Y., Bravo-Cordero J.J., Sharma V.P., Miskolci V., Hodgson L., and Condeelis J.. 2014. Talin regulates moesin-NHE-1 recruitment to invadopodia and promotes mammary tumor metastasis. J. Cell Biol. 205:737–751. 10.1083/jcb.201312046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin A.M., Zhidkova N.I., Balzac F., Altruda F., Tomatis D., Maier A., Tarone G., Koteliansky V.E., and Burridge K.. 1996. β 1D integrin displaces the β 1A isoform in striated muscles: localization at junctional structures and signaling potential in nonmuscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 132:211–226. 10.1083/jcb.132.1.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet B.P., and Akhmanova A.. 2017. Microtubules in 3D cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 130:39–50. 10.1242/jcs.189431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet B.P., Gough R.E., Ammon Y.-C., van de Willige D., Post H., Jacquemet G., Altelaar A.F.M., Heck A.J.R., Goult B.T., and Akhmanova A.. 2016. Talin-KANK1 interaction controls the recruitment of cortical microtubule stabilizing complexes to focal adhesions. eLife. 5:e18124 10.7554/eLife.18124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabodi S., Di Stefano P., Leal M.P., Tinnirello A., Bisaro B., Morello V., Damiano L., Aramu S., Repetto D., Tornillo G., and Defilippi P.. 2010. Integrins and signal transduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 674:43–54. 10.1007/978-1-4419-6066-5_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood D.A., Campbell I.D., and Critchley D.R.. 2013. Talins and kindlins: partners in integrin-mediated adhesion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14:503–517. 10.1038/nrm3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carisey A., Tsang R., Greiner A.M., Nijenhuis N., Heath N., Nazgiewicz A., Kemkemer R., Derby B., Spatz J., and Ballestrem C.. 2013. Vinculin regulates the recruitment and release of core focal adhesion proteins in a force-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 23:271–281. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case L.B., Baird M.A., Shtengel G., Campbell S.L., Hess H.F., Davidson M.W., and Waterman C.M.. 2015. Molecular mechanism of vinculin activation and nanoscale spatial organization in focal adhesions. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:880–892. 10.1038/ncb3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.C., Zhang H., Franco-Barraza J., Brennan M.L., Patel T., Cukierman E., and Wu J.. 2014. Structural and mechanistic insights into the recruitment of talin by RIAM in integrin signaling. Structure. 22:1810–1820. 10.1016/j.str.2014.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changede R., Xu X., Margadant F., and Sheetz M.P.. 2015. Nascent Integrin Adhesions Form on All Matrix Rigidities after Integrin Activation. Dev. Cell. 35:614–621. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C.H., Webb B.A., Chimenti M.S., Jacobson M.P., and Barber D.L.. 2013. pH sensing by FAK-His58 regulates focal adhesion remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 202:849–859. 10.1083/jcb.201302131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanasu C., Wang H., Henriot V., Mathieu C., Fente A., Csillag S., Vigouroux C., Faivre B., and Le Clainche C.. 2018. Integrin-bound talin head inhibits actin filament barbed-end elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 293:2586–2596. 10.1074/jbc.M117.808204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley D.R. 2009. Biochemical and structural properties of the integrin-associated cytoskeletal protein talin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 38:235–254. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danen E.H.J., and Sonnenberg A.. 2003. Integrins in regulation of tissue development and function. J. Pathol. 200:471–480. 10.1002/path.1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrand E., El Jai Y., Spence L., Bate N., Praekelt U., Pritchard C.A., Monkley S.J., and Critchley D.R.. 2009. Talin 2 is a large and complex gene encoding multiple transcripts and protein isoforms. FEBS J. 276:1610–1628. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06893.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio A., Perez-Jimenez R., Liu R., Roca-Cusachs P., Fernandez J.M., and Sheetz M.P.. 2009. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 323:638–641. 10.1126/science.1162912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzamba B.J., and DeSimone D.W.. 2018. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and the Sculpting of Embryonic Tissues. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 130:245–274. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott P.R., Goult B.T., Kopp P.M., Bate N., Grossmann J.G., Roberts G.C.K., Critchley D.R., and Barsukov I.L.. 2010. The Structure of the talin head reveals a novel extended conformation of the FERM domain. Structure. 18:1289–1299. 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S.J., Goult B.T., Fairchild M.J., Harris N.J., Long J., Lobo P., Czerniecki S., Van Petegem F., Schöck F., Peifer M., and Tanentzapf G.. 2013. Talin autoinhibition is required for morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 23:1825–1833. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elosegui-Artola A., Oria R., Chen Y., Kosmalska A., Pérez-González C., Castro N., Zhu C., Trepat X., and Roca-Cusachs P.. 2016. Mechanical regulation of a molecular clutch defines force transmission and transduction in response to matrix rigidity. Nat. Cell Biol. 18:540–548. 10.1038/ncb3336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elosegui-Artola A., Andreu I., Beedle A.E.M., Lezamiz A., Uroz M., Kosmalska A.J., Oria R., Kechagia J.Z., Rico-Lastres P., Le Roux A.-L., et al. 2017. Force Triggers YAP Nuclear Entry by Regulating Transport across Nuclear Pores. Cell. 171:1397–1410. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingham I., Gingras A.R., Papagrigoriou E., Patel B., Emsley J., Critchley D.R., Roberts G.C.K., Barsukov I.L., and Le L.. 2005. A Vinculin Binding Domain from the Talin Rod Unfolds to Form a Complex with the Vinculin Head. Structure. 13:65–74. 10.1016/j.str.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannone G., Jiang G., Sutton D.H., Critchley D.R., and Sheetz M.P.. 2003. Talin1 is critical for force-dependent reinforcement of initial integrin-cytoskeleton bonds but not tyrosine kinase activation. J. Cell Biol. 163:409–419. 10.1083/jcb.200302001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A.R., Ziegler W.H., Frank R., Barsukov I.L., Roberts G.C.K., Critchley D.R., and Emsley J.. 2005. Mapping and consensus sequence identification for multiple vinculin binding sites within the talin rod. J. Biol. Chem. 280:37217–37224. 10.1074/jbc.M508060200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A.R., Bate N., Goult B.T., Hazelwood L., Canestrelli I., Grossmann J.G., Liu H., Putz N.S.M., Roberts G.C.K., Volkmann N., et al. 2008. The structure of the C-terminal actin-binding domain of talin. EMBO J. 27:458–469. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A.R., Bate N., Goult B.T., Patel B., Kopp P.M., Emsley J., Barsukov I.L., Roberts G.C.K., and Critchley D.R.. 2010. Central region of talin has a unique fold that binds vinculin and actin. J. Biol. Chem. 285:29577–29587. 10.1074/jbc.M109.095455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goksoy E., Ma Y.-Q., Wang X., Kong X., Perera D., Plow E.F., and Qin J.. 2008. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of talin in regulating integrin activation. Mol. Cell. 31:124–133. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough R.E., and Goult B.T.. 2018. The tale of two talins - two isoforms to fine-tune integrin signalling. FEBS Lett. 592:2108–2125. 10.1002/1873-3468.13081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goult B.T., Bate N., Anthis N.J., Wegener K.L., Gingras A.R., Patel B., Barsukov I.L., Campbell I.D., Roberts G.C.K., and Critchley D.R.. 2009. The structure of an interdomain complex that regulates talin activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284:15097–15106. 10.1074/jbc.M900078200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goult B.T., Bouaouina M., Elliott P.R., Bate N., Patel B., Gingras A.R., Grossmann J.G., Roberts G.C.K., Calderwood D.A., Critchley D.R., and Barsukov I.L.. 2010. Structure of a double ubiquitin-like domain in the talin head: a role in integrin activation. EMBO J. 29:1069–1080. 10.1038/emboj.2010.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goult B.T., Zacharchenko T., Bate N., Tsang R., Hey F., Gingras A.R., Elliott P.R., Roberts G.C.K., Ballestrem C., Critchley D.R., and Barsukov I.L.. 2013. RIAM and vinculin binding to talin are mutually exclusive and regulate adhesion assembly and turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 288:8238–8249. 10.1074/jbc.M112.438119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan M., Venkatesan N., Loh J.T., Wong J.F., Berger H., Neo W.H., Li L.Y.J., La Win M.K., Yau Y.H., Guo T., et al. 2015. The methyltransferase Ezh2 controls cell adhesion and migration through direct methylation of the extranuclear regulatory protein talin. Nat. Immunol. 16:505–516. 10.1038/ni.3125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupton S.L., and Waterman-Storer C.M.. 2006. Spatiotemporal feedback between actomyosin and focal-adhesion systems optimizes rapid cell migration. Cell. 125:1361–1374. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann J., Grob M., and Burger M.M.. 1992. The Cytoskeletal Protein Talin Is 0-Glycosylated. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14424–14428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lim C.J., Watanabe N., Soriani A., Ratnikov B., Calderwood D.A., Puzon-McLaughlin W., Lafuente E.M., Boussiotis V.A., Shattil S.J., and Ginsberg M.H.. 2006. Reconstructing and deconstructing agonist-induced activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Curr. Biol. 16:1796–1806. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings L., Rees D.J., Ohanian V., Bolton S.J., Gilmore A.P., Patel B., Priddle H., Trevithick J.E., Hynes R.O., and Critchley D.R.. 1996. Talin contains three actin-binding sites each of which is adjacent to a vinculin-binding site. J. Cell Sci. 109:2715–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoellerer M.K., Noble M.E.M., Labesse G., Campbell I.D., Werner J.M., and Arold S.T.. 2003. Molecular recognition of paxillin LD motifs by the focal adhesion targeting domain. Structure. 11:1207–1217. 10.1016/j.str.2003.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton E.R., Byron A., Askari J.A., Ng D.H.J., Millon-Frémillon A., Robertson J., Koper E.J., Paul N.R., Warwood S., Knight D., et al. 2015. Definition of a consensus integrin adhesome and its dynamics during adhesion complex assembly and disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:1577–1587. 10.1038/ncb3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Jing C., Xu X., Nakazawa N., Cornish V.W., Margadant F.M., and Sheetz M.P.. 2016. Cooperative vinculin binding to talin mapped by time-resolved super resolution microscopy. Nano Lett. 16:4062–4068. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Rajfur Z., Yousefi N., Chen Z., Jacobson K., and Ginsberg M.H.. 2009. Talin phosphorylation by Cdk5 regulates Smurf1-mediated talin head ubiquitylation and cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:624–630. 10.1038/ncb1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Barker D., Gibbins J.M., and Dash P.R.. 2018. Talin is a substrate for SUMOylation in migrating cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 370:417–425. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries J.D., Wang P., Streuli C., Geiger B., Humphries M.J., and Ballestrem C.. 2007. Vinculin controls focal adhesion formation by direct interactions with talin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 179:1043–1057. 10.1083/jcb.200703036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R.O. 1992. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 69:11–25. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskratsch T., Wolfenson H., and Sheetz M.P.. 2014. Appreciating force and shape—the rise of mechanotransduction in cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15:825–833. 10.1038/nrm3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanchanawong P., Shtengel G., Pasapera A.M., Ramko E.B., Davidson M.W., Hess H.F., and Waterman C.M.. 2010. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature. 468:580–584. 10.1038/nature09621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina I., Krylyshkina O., Beningo K., Anderson K., Wang Y.-L., and Small J.V.. 2002. Tensile stress stimulates microtubule outgrowth in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 115:2283–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapholz B., Herbert S.L., Wellmann J., Johnson R., Parsons M., and Brown N.H.. 2015. Alternative mechanisms for talin to mediate integrin function. Curr. Biol. 25:847–857. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., García A.J., Mould A.P., Humphries M.J., and Zhu C.. 2009. Demonstration of catch bonds between an integrin and its ligand. J. Cell Biol. 185:1275–1284. 10.1083/jcb.200810002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., Li Z., Parks W.M., Dumbauld D.W., García A.J., Mould A.P., Humphries M.J., and Zhu C.. 2013. Cyclic mechanical reinforcement of integrin-ligand interactions. Mol. Cell. 49:1060–1068. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp P.M., Bate N., Hansen T.M., Brindle N.P.J., Praekelt U., Debrand E., Coleman S., Mazzeo D., Goult B.T., Gingras A.R., et al. 2010. Studies on the morphology and spreading of human endothelial cells define key inter- and intramolecular interactions for talin1. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89:661–673. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Ouyang M., Van den Dries K., McGhee E.J., Tanaka K., Anderson M.D., Groisman A., Goult B.T., Anderson K.I., and Schwartz M.A.. 2016. Talin tension sensor reveals novel features of focal adhesion force transmission and mechanosensitivity. J. Cell Biol. 213:371–383. 10.1083/jcb.201510012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J.-C., Han X., Hsiao C.-T., Yates J.R. III, and Waterman C.M.. 2011. Analysis of the myosin-II-responsive focal adhesion proteome reveals a role for β-Pix in negative regulation of focal adhesion maturation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:383–393. 10.1038/ncb2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarrigue F., Vikas Anekal P., Lee H.S., Bachir A.I., Ablack J.N., Horwitz A.F., and Ginsberg M.H.. 2015. A RIAM/lamellipodin-talin-integrin complex forms the tip of sticky fingers that guide cell migration. Nat. Commun. 6:8492 10.1038/ncomms9492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-S., Bellin R.M., Walker D.L., Patel B., Powers P., Liu H., Garcia-Alvarez B., de Pereda J.M., Liddington R.C., Volkmann N., et al. 2004. Characterization of an actin-binding site within the talin FERM domain. J. Mol. Biol. 343:771–784. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-S., Lim C.J., Puzon-McLaughlin W., Shattil S.J., and Ginsberg M.H.. 2009. RIAM activates integrins by linking talin to ras GTPase membrane-targeting sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 284:5119–5127. 10.1074/jbc.M807117200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Du X., Vass W.C., Papageorge A.G., Lowy D.R., and Qian X.. 2011. Full activity of the deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC1) tumor suppressor depends on an LD-like motif that binds talin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:17129–17134. 10.1073/pnas.1112122108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margadant F., Chew L.L., Hu X., Yu H., Bate N., Zhang X., and Sheetz M.. 2011. Mechanotransduction in vivo by repeated talin stretch-relaxation events depends upon vinculin. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001223 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann R.O., and Craig S.W.. 1997. The I/LWEQ module: a conserved sequence that signifies F-actin binding in functionally diverse proteins from yeast to mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:5679–5684. 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkley S.J., Zhou X.-H., Kinston S.J., Giblett S.M., Hemmings L., Priddle H., Brown J.E., Pritchard C.A., Critchley D.R., and Fässler R.. 2000. Disruption of the talin gene arrests mouse development at the gastrulation stage. Dev. Dyn. 219:560–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti A., Machacek M., Gupton S.L., Waterman-Storer C.M., and Danuser G.. 2004. Two distinct actin networks drive the protrusion of migrating cells. Science. 305:1782–1786. 10.1126/science.1100533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnikov B., Ptak C., Han J., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D.F., and Ginsberg M.H.. 2005. Talin phosphorylation sites mapped by mass spectrometry. J. Cell Sci. 118:4921–4923. 10.1242/jcs.02682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringer P., Weißl A., Cost A.-L., Freikamp A., Sabass B., Mehlich A., Tramier M., Rief M., and Grashoff C.. 2017. Multiplexing molecular tension sensors reveals piconewton force gradient across talin-1. Nat. Methods. 14:1090–1096. 10.1038/nmeth.4431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltel F., Mortier E., Hytönen V.P., Jacquier M.-C., Zimmermann P., Vogel V., Liu W., and Wehrle-Haller B.. 2009. New PI(4,5)P2- and membrane proximal integrin-binding motifs in the talin head control beta3-integrin clustering. J. Cell Biol. 187:715–731. 10.1083/jcb.200908134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönichen A., Webb B.A., Jacobson M.P., and Barber D.L.. 2013. Considering protonation as a posttranslational modification regulating protein structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42:289–314. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.A., Both G., and Lechene C.. 1989. Effect of cell spreading on cytoplasmic pH in normal and transformed fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:4525–4529. 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.A., Lechene C., and Ingber D.E.. 1991. Insoluble fibronectin activates the Na/H antiporter by clustering and immobilizing integrin alpha 5 beta 1, independent of cell shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:7849–7853. 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senetar M.A., and McCann R.O.. 2005. Gene duplication and functional divergence during evolution of the cytoskeletal linker protein talin. Gene. 362:141–152. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Yang J., Hirbawi J., Ye S., Perera H.D., Goksoy E., Dwivedi P., Plow E.F., Zhang R., and Qin J.. 2012. A novel membrane-dependent on/off switch mechanism of talin FERM domain at sites of cell adhesion. Cell Res. 22:1533–1545. 10.1038/cr.2012.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava J., Barreiro G., Groscurth S., Gingras A.R., Goult B.T., Critchley D.R., Kelly M.J.S., Jacobson M.P., and Barber D.L.. 2008. Structural model and functional significance of pH-dependent talin-actin binding for focal adhesion remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:14436–14441. 10.1073/pnas.0805163105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens S.J., Paszek M., Pemble H., Ettinger A., Gierke S., and Wittmann T.. 2014. CLASPs link focal-adhesion-associated microtubule capture to localized exocytosis and adhesion site turnover. Nat. Cell Biol. 16:558–573. 10.1038/ncb2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N., Critchley D.R., Paulin D., Li Z., and Robson R.M.. 2008. Identification of a repeated domain within mammalian α-synemin that interacts directly with talin. Exp. Cell Res. 314:1839–1849. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Guo S.S., and Fässler R.. 2016a Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J. Cell Biol. 215:445–456. 10.1083/jcb.201609037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Tseng H.-Y.Y., Tan S., Senger F., Kurzawa L., Dedden D., Mizuno N., Wasik A.A., Thery M., Dunn A.R., and Fässler R.. 2016b Kank2 activates talin, reduces force transduction across integrins and induces central adhesion formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 18:941–953. 10.1038/ncb3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart B., van Riel W.E., Doodhi H., Kevenaar J.T., Katrukha E.A., Gumy L., Bouchet B.P., Grigoriev I., Spangler S.A., Yu K.L., et al. 2013. CFEOM1-associated kinesin KIF21A is a cortical microtubule growth inhibitor. Dev. Cell. 27:145–160. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle-Haller B. 2012. Assembly and disassembly of cell matrix adhesions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24:569–581. 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd-Katz S.E., Fässler R., Geiger B., and Legate K.R.. 2014. The integrin adhesome: from genes and proteins to human disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15:273–288. 10.1038/nrm3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Yao M., Goult B.T., and Sheetz M.P.. 2015. Talin Dependent Mechanosensitivity of Cell Focal Adhesions. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 8:151–159. 10.1007/s12195-014-0364-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M., Goult B.T., Chen H., Cong P., Sheetz M.P., and Yan J.. 2014. Mechanical activation of vinculin binding to talin locks talin in an unfolded conformation. Sci. Rep. 4:4610 10.1038/srep04610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M., Goult B.T., Klapholz B., Hu X., Toseland C.P., Guo Y., Cong P., Sheetz M.P., and Yan J.. 2016. The mechanical response of talin. Nat. Commun. 7:11966 10.1038/ncomms11966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., McLean M.A., and Sligar S.G.. 2016. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate Modulates the Affinity of Talin-1 for Phospholipid Bilayers and Activates Its Autoinhibited Form. Biochemistry. 55:5038–5048. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C.H., Rafiq N.B.M., Krishnasamy A., Hartman K.L., Jones G.E., Bershadsky A.D., and Sheetz M.P.. 2013. Integrin-matrix clusters form podosome-like adhesions in the absence of traction forces. Cell Reports. 5:1456–1468. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharchenko T., Qian X., Goult B.T., Jethwa D., Almeida T.B., Ballestrem C., Critchley D.R., Lowy D.R., and Barsukov I.L.. 2016. LD Motif Recognition by Talin: Structure of the Talin-DLC1 Complex. Structure. 24:1130–1141. 10.1016/j.str.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Saha S., and Kashina A.. 2012. Arginylation-dependent regulation of a proteolytic product of talin is essential for cell-cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 197:819–836. 10.1083/jcb.201112129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Yang J., Bromberger T., Holly A., Lu F., Liu H., Sun K., Klapproth S., Hirbawi J., Byzova T.V., et al. 2017. Structure of Rap1b bound to talin reveals a pathway for triggering integrin activation. Nat. Commun. 8:1744 10.1038/s41467-017-01822-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]