Abstract

Background

Although the prognosis of core‐binding factor (CBF) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is better than other subtypes of AML, 30% of patients still relapse and may require allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT). However, there is no validated widely accepted scoring system to predict patient subsets with higher risk of relapse.

Methods

Eleven centers in the US and Europe evaluated 247 patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22).

Results

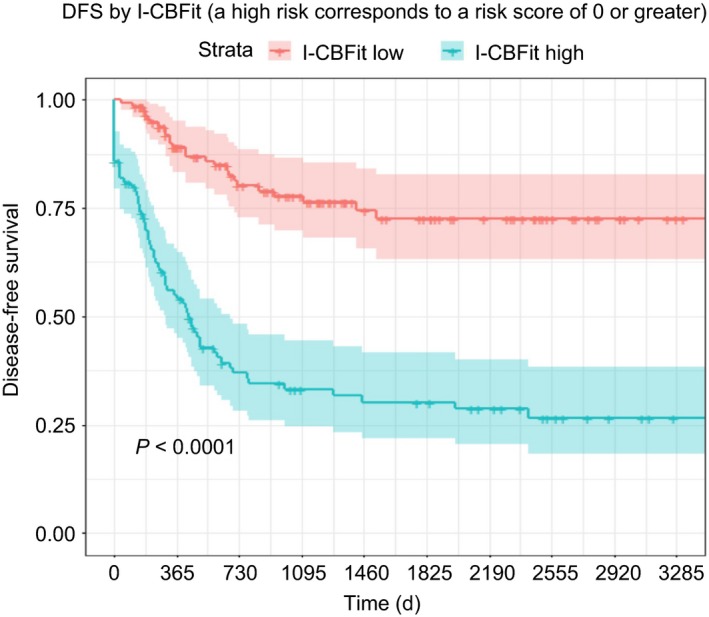

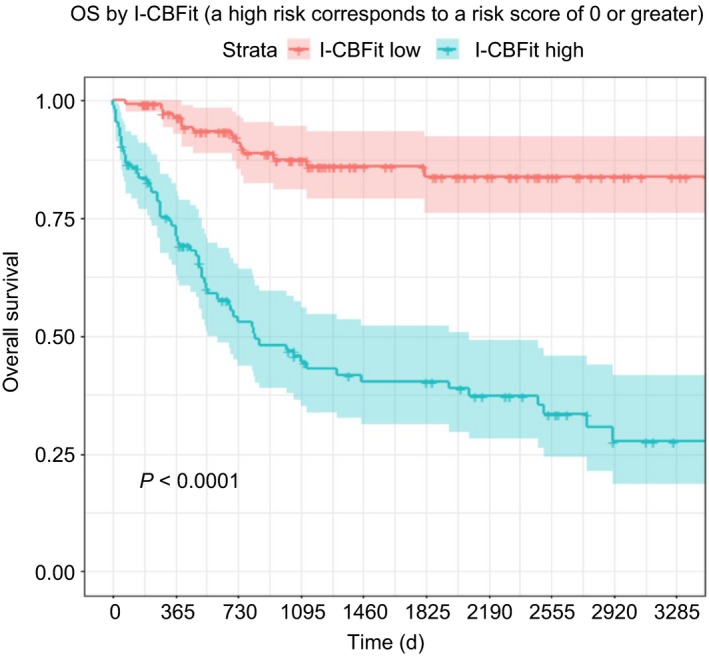

Complete remission (CR) rate was high (92.7%), yet relapse occurred in 27.1% of patients. A total of 24.7% of patients received alloHCT. The median disease‐free (DFS) and overall (OS) survival were 20.8 and 31.2 months, respectively. Age, KIT D816V mutated (11.3%) or nontested (36.4%) compared with KIT D816V wild type (52.5%), high white blood cell counts (WBC), and pseudodiploidy compared with hyper‐ or hypodiploidy were included in a scoring system (named I‐CBFit). DFS rate at 2 years was 76% for patients with a low‐risk I‐CBFit score compared with 36% for those with a high‐risk I‐CBFit score (P < 0.0001). Low‐ vs high‐risk OS at 2 years was 89% vs 51% (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

I‐CBFit composed of readily available risk factors can be useful to tailor the therapy of patients, especially for whom alloHCT is not need in CR1 (ie, patients with a low‐risk I‐CBFit score).

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, core‐binding factor, disease‐free survival, KIT mutation, predictive value, relapse, scoring system

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with rearrangements involving genes encoding subunits of core‐binding factor (CBF), a group of DNA‐binding transcription factor complexes composed of α and β subunits, shares similar pathogenesis and clinical features and is considered as a distinct subset in AML.1, 2, 3, 4 Translocation(8;21)(q22;q22) and inv(16)(p13q22), the most frequent cytogenetic abnormalities occurring in CBF‐AML, lead to the creation of the fusion genes RUNX1/RUNXT1 and CBFB/MYH11 that disrupt, respectively, the α and β subunits of CBF, dysregulate hematopoiesis, and thus contribute to leukemogenesis.5

Although the prognosis of CBF‐AML is better than other subtypes of AML, approximately 30%‐40% of the patients still relapse and may require allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).6, 7, 8 A scoring system to predict who has a higher risk of relapse at the time of diagnosis may be clinically valuable to guide decision‐making. There have been only a few studies attempting to develop a scoring system for poor outcomes of CBF‐AML (eg, relapse and disease‐free survival [DFS]).6, 8 The relative rarity of CBF‐AML (approximately 15%‐20% of AML cases) in adults9 and its relatively good prognosis may have limited these efforts. A useful prognostic system requires a large sample size and long follow‐up time including all treatment data. This is challenging, even for large registries or cooperative groups. For example, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) only has data of patients with CBF‐AML receiving a HCT, while US cooperative groups may have too few patients with a long follow‐up to examine outcomes after HCT. Moreover, recent studies clearly indicate that AMLs with t(8;21) (q22;q22) and AMLs with inv(16) (p13q22) are two different diseases regarding patient and disease characteristics.2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Each cytogenetic subgroup therefore should be evaluated separately to develop a specific prognostic scoring system.

In this multicenter study, we created an extensive database including US and European centers for CBF‐AML patients with t(8;21) (q22;q22), and developed and validated a significant risk scoring system with high predictive probabilities.

2. METHODS

Eleven centers in the US and Europe collaborated to collect data on 550 CBF‐AML patients. Two‐hundred and forty‐seven of these patients had t(8;21)(q22;q22) and are the subject of this report. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) AML patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22) or RUNX1‐RUNX1T1 confirmed by the reporting institutions; (b) cases diagnosed between July 1996 and January 2017. Data were uniformly collected by completing a predesigned data spreadsheet. The data form included the following: patient characteristics (age, sex, race); disease characteristics (date of diagnosis, white blood cell count [WBC] at diagnosis [×109/L], cytogenetics, KIT D816V mutational status, primary or secondary AML); therapy characteristics (induction regimens and their number, consolidation regimens, and number of cycles); HCT (autologous or allogeneic, donor type, remission status at HCT); and events (relapse, death, or alive at last contact). Patients’ data were anonymously transferred to University of Minnesota where the main database was created and managed. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee at the University of Minnesota.

2.1. Definitions

Secondary AML was assigned if a patient had a history of chemotherapy/radiation therapy for a malignancy and/or had a history of preleukemic disease (eg, myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS], myeloproliferative neoplasm [MPN]). In cytogenetic evaluation, a total number of 46 chromosomes were defined as pseudodiploidy in one clone or each clone (given this patients had translocation, it was not named diploidy), and if chromosome number was higher or lower than 46 chromosomes in any clone, it was defined, respectively, as hyperdiploidy and hypodiploidy.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The sample of 247 patients was described using the median and range for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables.

The binary outcome was defined as death or relapse within 2 years of diagnosis. A total of 89 patients experienced death or relapse within 2 years, while 158 patients survived without relapse or were censored at the last contact alive (or in remission).

A set of potential predictors for our outcome of relapse‐free survival was selected to build the risk score model, which were used to predict the probability of death or relapse in 2 years. The predictors included age, sex, race (Caucasian), WBC at diagnosis, ‐X, ‐Y, chromosome 5 or 7 abnormalities, chromosome 4 abnormalities, chromosome 9 abnormalities, trisomy 8, number of chromosomes, KIT D816V mutation, and primary AML. The missing values for the variable KIT D816V mutation were combined into the category nontested instead of imputing the variable, so as to allow risk prediction when this variable is missing. The remaining covariates that had missing values in the dataset were variables considered unlikely to be missing in clinical practice, and thus, multiple imputation was used so as to construct a clinically meaningful risk score that made full use of available patient information.

Full details of the statistical analysis are provided in the Appendix S1. In brief, forward stepwise logistic regression was used, with the binary outcome of two‐year relapse or death and the predictors discussed above. The optimal threshold for binary predictions was chosen to maximize equally the sensitivity and specificity. A validation study was used to assess the performance of the risk score model using fivefold cross‐validation to estimate specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

We performed three sensitivity analyses. In the first, patients were censored upon allogeneic HCT (alloHCT) at CR1, as this is not a standard therapy. In the second, we considered only survival (rather than disease‐free survival). In the final sensitivity analysis, we imputed all missing values (including KIT D816V mutation) to create a risk score that would require all relevant covariates to be observed rather than allowing for the possibility that some are unavailable to the clinician.

3. RESULTS

The characteristics of the test and validation groups combined are provided in Table 1. Patients were mostly male, were Caucasian, and had a median age of 47 years, and 17.4% had secondary AML. Additional cytogenetic abnormalities were frequently observed (58.7%), and 44.5% of patients had a hypodiploid or hyperdiploid clone. KIT D816V mutation was present in 11.3% of patients (17.8% of the patients tested), and any KIT mutations were detected in 16.6% of patients (25.7% of the patients tested). There was no association between KIT mutation (positive, negative, nontested) and WBC (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Variable | Total |

|---|---|

| Number | 247 |

| Age, median (range) y | 47.0 (2.0‐81.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 101 (40.9%) |

| Male | 132 (53.4%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 14 (5.6%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 176 (71.3%) |

| Other | 48 (19.4%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 23 (9.3%) |

| Year of diagnosis, median (range) | 2009 (1995‐2017) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| WBC at diagnosis, median (range) ×109/L | 11.7 (1.3‐139.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 19 (7.7%) |

| AML, n (%) | |

| Primary | 194 (78.5%) |

| Secondary | 43 (17.4%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 10 (4.0%) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| ‐X, n (%) | |

| No | 206 (83.4%) |

| Yes | 33 (13.4%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| ‐Y, n (%) | |

| No | 192 (77.7%) |

| Yes | 48 (19.4%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 7 (2.8%) |

| Chromosome 9 abnormalities, n (%) | |

| No | 210 (85.0%) |

| Yes | 29 (11.7%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Chromosome 4 abnormalities, n (%) | |

| No | 232 (94.0%) |

| Yes | 7 (2.8%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Chromosome 5 or 7 abnormalities, n (%) | |

| No | 210 (85.0%) |

| Yes | 28 (11.3%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 9 (3.6%) |

| +8, n (%) | |

| No | 211 (85.4%) |

| Yes | 28 (11.3%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Number of Chromosomes, n (%) | |

| 46 | 129 (52.2%) |

| <46 | 87 (35.2%) |

| >46 | 23 (9.3%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Additional cytogenetic abnormality, n (%) | |

| Yes | 145 (58.7%) |

| No | 95 (38.5%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 7 (2.8%) |

| KIT mutation, n (%) | |

| Negative | 118 (47.8%) |

| Positive | 41 (16.6%) |

| Nontested/Missing, n (%) | 88 (35.6%) |

| KIT D816V mutation, n (%) | |

| Negative | 129 (52.5%) |

| Positive | 28 (11.3%) |

| Nontested/Missing | 90 (36.4%) |

| CR status, n (%) | |

| Yes | 229 (92.7%) |

| Relapse, n (%) | |

| Yes | 67 (27.1%) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Does not apply (%) | 18 (7.3%) |

| AlloHCT, n (%) | |

| Yes | 61 (24.7%) |

| Disease status at alloHCT n (%) | |

| No CR | 10 (4.0%) |

| CR1 | 31 (12.5%) |

| CR2 | 18 (7.3%) |

| >CR2 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4%) |

| Does not apply | 186 (75.3%) |

| DFS, median (range) mo | 20.8 (0‐225.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| OS, median (range) months | 31.2 (1‐245.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) |

AlloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; CR, complete remission; DFS, disease‐free survival; OS, overall survival; WBC, white blood cell count.

Complete remission (CR) was achieved in the vast majority of patients (92.7) (Table 1). Relapse occurred in 67 patients (27.1%) at a median of 10.6 months (range 1‐65.5 months). AlloHCT was performed in 61 patients (24.7%): 31 with CR1 (12.5%), 19 with ≥CR2 (7.6%), and 10 (4.0%) with active leukemia (all relapsed after CR). AlloHCT in CR1 was performed at a median of 6 months (range 2 to 13.1 months) from diagnosis and 4 months (1.1‐12 months) from the date of CR1. The median follow‐up was 64 months (0.5 to 1378 months).

The risk factors and risk ratios from a logistic regression model are presented in Table 2. Older age, higher WBC at diagnosis, KIT D816V mutation, and a pseudodiploid karyotype were associated with higher risks of death or disease relapse. Race, sex, and primary vs. secondary AML had no impact.

Table 2.

Risk ratios of risk factors for death or relapse

| Risk factor | Risk ratio | P‐value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.031 | 0.0017 |

| KIT D816V mutation positive (Ref = negative) | 4.331 | 0.0018 |

| KIT D816V mutation nontested/missing (Ref = negative) | 2.567 | 0.0036 |

| WBC at diagnosis | 1.018 | 0.0361 |

| Number of chromosomes (Ref = nonpseudodiploidy) | 2.552 | 0.0035 |

WBC indicates white blood cell count.

The risk of death or relapse within 2 years associated with the covariates retained in the predictive risk score is shown in Table 2. The concordance statistic (a measure of the model fit, also called the area under curve (AUC), or area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for the predictions) is 0.756 (Figure S2). The optimal risk score is found by computing the following linear score:

The full set of results of the validation study along with the sensitivity analysis results (the highest of the conditional probabilities was negative predictive value [NPV], 80%) are presented in Table S1. When I‐CBFit > 0, a patient is classed as being at high risk of death or relapse within 2 years. DFS rate at 2 years was 76% for patients with a low‐risk I‐CBFit score compared with 36% for those with a high‐risk I‐CBFit score (P < 0.0001). Low‐ vs high‐risk OS at 2 years was 89% vs 51%, P < 0.0001 (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Patients with a low I‐CBFit score (red curve with 95% CI) had significantly higher DFS compared with those who had a higher score (green curve with 95% CI)

Figure 2.

Patients with a low I‐CBFit score (red curve with 95% CI) had significantly higher OS compared with those who had a higher score (green curve with 95% CI)

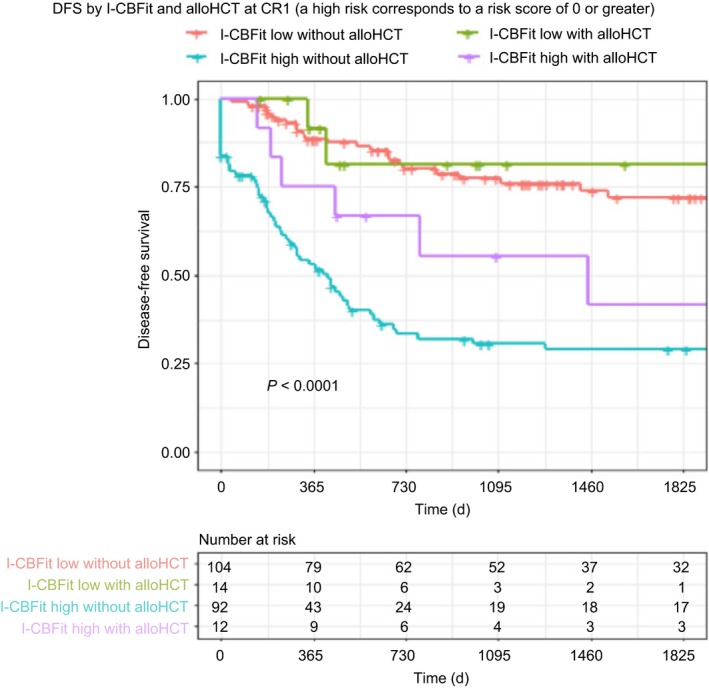

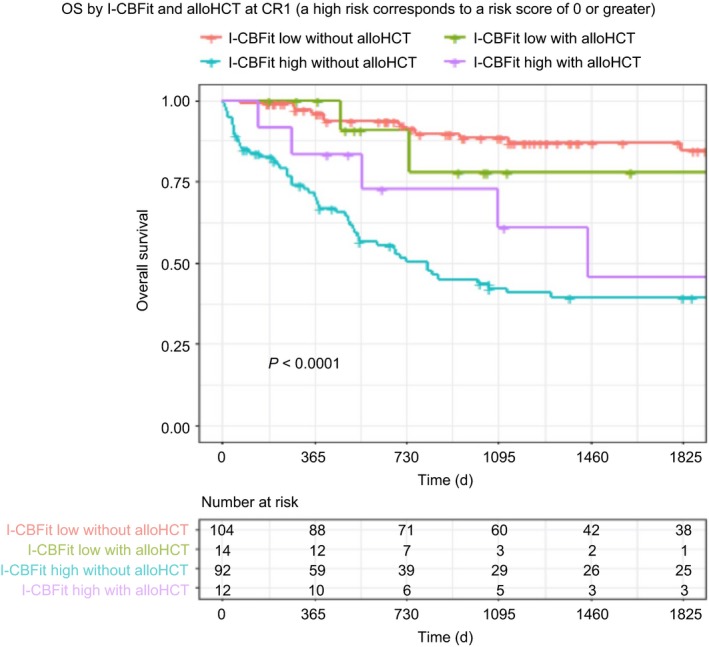

DFS at 2 years was 80% for patients with I‐CBFit low risk not undergoing alloHCT in CR1, was 82% for patients with I‐CBFit low risk undergoing alloHCT in CR1, was 33% for patients with I‐CBFit high risk not undergoing alloHCT in CR1, and was 67% for patients with I‐CBFit high risk undergoing alloHCT in CR1, P = <0.0001 (Figure 3). OS at 2 years was 91% for patients with I‐CBFit low risk regardless of alloHCT in CR1, was 52% for patients with I‐CBFit high risk not undergoing alloHCT in CR1, and was 73% for patients with I‐CBFit high risk undergoing alloHCT in CR1, P < 0.0001 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

DFS is stratified by alloHCT and I‐CBFit score. AlloHCT did not have an impact on DFS in patients with a low I‐CBFit score (red and green curves); however, patients with high I‐CBFit‐risk had improved DFS after alloHCT compared with those who did not undergo alloHCT (purple and green curves)

Figure 4.

OS is stratified by alloHCT and I‐CBFit score. AlloHCT did not have an impact on OS in patients with a low I‐CBFit score (red and green curves); however, patients with high I‐CBFit risk had improved OS after alloHCT compared with those who did not undergo alloHCT (purple and green curves)

4. DISCUSSION

In this large study with a long follow‐up, we were able to create and validate the risk scoring system we are calling the “International CBF group index for t(8;21)” (I‐CBFit) in t(8;21) AML. We show that older age, higher WBC at diagnosis, and KIT D816V mutation were risk factors associated with treatment failure (relapse or death). In addition, we found that pseudodiploidy was also a risk factor in t(8;21), a novel finding. I‐CBFit had a high NPV (80%) and a modest specificity and accuracy for DFS, and the NPV was even higher for the prediction of OS.

Current treatment guidelines for CBF‐AML with t(8;21) do not recognize heterogeneity in these patients, and thus, all t(8;21) AML patients generally receive the same induction and consolidation treatments. This might be appropriate for patients with a low‐risk score who are predicted to have nearly an 80% chance of extended DFS. On the other hand, high‐risk score patients may benefit from more intensive approaches in CR1. Current guidelines do not identify patients needing alloHCT in CR1. This new model may clarify this uncertainty, especially identifying patients who do not require intensive consolidations (eg, alloHCT) in CR1 given its high NPV. Although patients receiving alloHCT in CR1 was limited, when we analyzed the impact of alloHCT it seemed that patients with an I‐CBFit low‐risk score had similar DFS and OS regardless of alloHCT.

KIT mutations have been reported in 15%‐46% of adults patients with t(8;21) CBF‐AML.13, 15, 16, 17, 18 KIT D816V mutations were reported in 4%‐28% and strongly associated with poorer DFS (6%‐48%).13, 16, 19, 20 In pediatric populations, KIT mutations clustered in exon 17 and exon 8 were identified in 20‐30% of the CBF‐AML patients,21, 22, 23 yet its effect on prognosis is not agreed upon.22, 24 A meta‐analysis indicated KIT mutation increased relapse risk (RR at 2 years 1.76 [95% CI: 1.45‐2.12]) and decreased OS 1.35 (95% CI: 1.09‐1.66).25

Chromosomal abnormalities secondary to t(8;21), mostly involving loss of a sex chromosome, ‐Y in men and ‐X in women, trisomy 8, and deletion of the long arm of chromosome 9 [del(9p)] are frequently reported.6, 8, 14, 18 In our patients, additional cytogenetic abnormalities were common, as in other reports.14, 18, 26 Sex chromosome loss was reported as favorable for two‐year event‐free survival (66.9% vs 43.0%, P = 0.031).18 In contrast, DFS was shorter for male patients with loss of the Y chromosome. In another study,8 loss of a sex chromosome was associated with increased CR rates in CBF‐AML.14 We found no particular chromosomal abnormality to be associated with poor outcome. However, consistent with findings of Krauth et al18 loss of a sex chromosome had a modestly favorable, but not significant effect on DFS. We also found that the chromosome number was important, with patients with pseudodiploid karyotypes having worse outcome compared with those with hypodiploidy or hyperdiploidy.

Higher WBCs were found to be associated with poorer outcomes.8 Schlenk et al8 described a scoring system using two factors, high WBC, and low platelet counts, to be prognostic. Low platelet count was also a poor prognostic factor in a CALGB/Alliance study.6 In our study, we did not find a correlation between KIT mutation and WBC.

An earlier CALGB/Alliance study showed that age was associated with shorter overall survival (OS).6 In a more recent CALGB/Alliance study,27 3‐year OS rate was 61% for adults younger than 60 years vs only 47% for those at least 60 years old. Appelbaum et al14 showed that age is associated with a shorter OS.

We were able to collect data over a two‐decade period and believe this long time period does not adversely impact the validity of the study as (a) the type and number of induction or consolidation therapies did not have an impact on outcomes and (b) the most widely used treatments (7 + 3 in induction phase and high‐dose cytarabine in consolidation phase) have not changed over this time. Although this is a retrospective study, we find the data robust and substantial given the lengthy time period of patient follow‐up. In fact, long‐term follow‐up allowed complete evaluation in this relatively good prognostic disease.

Another limitation is that molecular abnormalities, including mutations in the KIT and FLT3 genes, were not uniformly tested. As a result, information on KIT mutational status is missing in approximately one‐third of the patients. However, KIT mutation was associated with significantly decreased survival compared with KIT wild type, whereas outcomes of patients with the KIT mutational status untested fell between outcomes of patients with KIT mutations and those with wild‐type KIT; this might be expected given that some but not all untested patients would have mutated KIT. This strongly supports the adverse effect of a KIT mutation.

This new scoring system, I‐CBFit, uses known and novel risk factors to provide a binary prediction of the risk of death or relapse within 2 years. Importantly, all factors and thus the scoring system can easily be determined at diagnosis. Although its validation by other studies is needed, I‐CBFit can contribute to current treatment of patients with t(8;21) and tailor consolidation treatments for individual patients in the spirit of precision medicine to identify those who do not need intensified management including alloHCT during CR1.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to the study to disclose.

Supporting information

Ustun C, Morgan E, Moodie EEM, et al. Core‐binding factor acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21): Risk factors and a novel scoring system (I‐CBFit). Cancer Med. 2018;7:4447–4455. 10.1002/cam4.1733

REFERENCES

- 1. Ustun C, Marcucci G. Emerging diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in core binding factor acute myeloid leukaemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:85‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Solh M, Yohe S, Weisdorf D, Ustun C. Core‐binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: heterogeneity, monitoring, and therapy. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:1121‐1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dohner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1136‐1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng CK, Li L, Cheng SH, et al. Transcriptional repression of the RUNX3/AML2 gene by the t(8;21) and inv(16) fusion proteins in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:3391‐3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcucci G, Mrozek K, Ruppert AS, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21) differ from those of patients with inv(16): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5705‐5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jourdan E, Boissel N, Chevret S, et al. Prospective evaluation of gene mutations and minimal residual disease in patients with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:2213‐2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schlenk RF, Benner A, Krauter J, et al. Individual patient data‐based meta‐analysis of patients aged 16 to 60 years with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a survey of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3741‐3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sinha C, Cunningham LC, Liu PP. Core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: new prognostic categories and therapeutic opportunities. Semin Hematol. 2015;52:215‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mosna F, Papayannidis C, Martinelli G, et al. Complex karyotype, older age, and reduced first‐line dose intensity determine poor survival in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia patients with long‐term follow‐up. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:515‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bullinger L, Rucker FG, Kurz S, et al. Gene‐expression profiling identifies distinct subclasses of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:1291‐1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duployez N, Marceau‐Renaut A, Boissel N, et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2451‐2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cairoli R, Beghini A, Grillo G, et al. Prognostic impact of c‐KIT mutations in core binding factor leukemias: an Italian retrospective study. Blood. 2006;107:3463‐3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Appelbaum FR, Kopecky KJ, Tallman MS, et al. The clinical spectrum of adult acute myeloid leukaemia associated with core binding factor translocations. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:165‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allen C, Hills RK, Lamb K, et al. The importance of relative mutant level for evaluating impact on outcome of KIT, FLT3 and CBL mutations in core‐binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27:1891‐1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boissel N, Leroy H, Brethon B, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of c‐Kit, FLT3, and Ras gene mutations in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF‐AML). Leukemia. 2006;20:965‐970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park SH, Chi HS, Min SK, Park BG, Jang S, Park CJ. Prognostic impact of c‐KIT mutations in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1376‐1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krauth MT, Eder C, Alpermann T, et al. High number of additional genetic lesions in acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)/RUNX1‐RUNX1T1: frequency and impact on clinical outcome. Leukemia. 2014;28:1449‐1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of KIT mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) and t(8;21): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3904‐3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Care RS, Valk PJ, Goodeve AC, et al. Incidence and prognosis of c‐KIT and FLT3 mutations in core binding factor (CBF) acute myeloid leukaemias. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:775‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tokumasu M, Murata C, Shimada A, et al. Adverse prognostic impact of KIT mutations in childhood CBF‐AML: the results of the Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group AML‐05 trial. Leukemia. 2015;29:2438‐2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pollard JA, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of KIT mutations in pediatric patients with core binding factor AML enrolled on serial pediatric cooperative trials for de novo AML. Blood. 2010;115:2372‐2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shimada A, Taki T, Tabuchi K, et al. KIT mutations, and not FLT3 internal tandem duplication, are strongly associated with a poor prognosis in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21): a study of the Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study Group. Blood. 2006;107:1806‐1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen X, Dou H, Wang X, et al. KIT mutations correlate with adverse survival in children with core‐binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:829‐839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen W, Xie H, Wang H, et al. Prognostic significance of KIT mutations in core‐binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuchenbauer F, Schnittger S, Look T, et al. Identification of additional cytogenetic and molecular genetic abnormalities in acute myeloid leukaemia with t(8;21)/AML1‐ETO. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:616‐619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mrozek K, Marcucci G, Nicolet D, et al. Prognostic significance of the European LeukemiaNet standardized system for reporting cytogenetic and molecular alterations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4515‐4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials