ABSTRACT

Brattleboro rats harbor a spontaneous deletion of the arginine-vasopressin (Avp) gene. In addition to diabetes insipidus, these rats exhibit low levels of anxiety and depressive behaviors. Recent work on the gut-brain axis has revealed that gut microbiota can influence anxiety behaviors. Therefore, we studied the effects of Avp gene deletion on gut microbiota. Since Avp gene expression is sexually different, we also examined how Avp deletion affects sex differences in gut microbiota. Males and females show modest but differentiated shifts in taxa abundance across 3 separate Avp deletion genotypes: wildtype (WT), heterozygous (Het) and AVP-deficient Brattleboro (KO) rats. For each sex, we found examples of taxa that have been shown to modulate anxiety behavior, in a manner that correlates with anxiety behavior observed in homozygous knockout Brattleboro rats. One prominent example is Lactobacillus, which has been reported to be anxiolytic: Lactobacillus was found to increase in abundance in inverse proportion to increasing gene dosage (most abundant in KO rats). This genotype effect of Lactobacillus abundance was not found when females were analyzed independently. Therefore, Avp deletion appears to affect microbiota composition in a sexually differentiated manner.

KEYWORDS: 16S rRNA, Brattleboro, gut microbiota, sex differences, rat

Introduction

The neuropeptide arginine-vasopressin (AVP) is released from hypothalamic neurons into the bloodstream of mammals, where it regulates water balance and other autonomic functions.1 However, AVP is also released within the brain where it has been shown to influence social and anxiety-like behavior,2 and modulate stress responses.3 The Brattleboro rat, which contains a base-pair deletion in the Avp gene which prevents functional AVP expression, is a model for studying the effects of AVP on behavior.4,5 Many of the behavioral abnormalities observed in Brattleboro rats, such as decreases in anxiety-like behavior6 and abnormal social preference,7 are assumed to result from a lack of direct activation of AVP-responsive behavioral circuits. However, systemic factors that may be influenced by AVP expression may also influence anxiety and social behaviors in this model. One such systemic factor may be the gut microbiome, which has recently been shown to influence both social and anxiety behaviors.8

Treatment of mice with antibiotics, which produces large-scale reconfiguration and depletion of gut microbiota, decreases hypothalamic AVP expression.9 This suggests that microbiota may influence AVP expression. However, this axis may be bidirectional and there are multiple ways in which AVP expression could influence microbiota composition. For example, AVP expression influences stress responses, systemic inflammation, and behaviors that could subsequently influence microbiota composition. Furthermore, it is plausible that AVP expression and gut microbial compositional changes that are influenced by AVP expression could reinforce each other in a positive feedback loop.

This study seeks to establish whether there are compositional differences in gut microbiota between AVP knockout rats and wildtype rats. In addition, as AVP expression is sexually dimorphic, with male rodents expressing more than female rodents in centrally-releasing projections as well as in neurosecretory cells,10,11 we sought to observe the effects of AVP deletion on sex differences in gut microbiota. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: i) to compare microbiota composition across AVP deletion genotypes (homozygous knockout, heterozygous, and wildtype Long Evans rats) and ii) to identify changes in sex differences of the microbiota upon haploid or diploid deletion of the AVP gene.

Results

Metadata. Long Evans rats with heterozygous expression of a functional and nonfunctional copy of the arginine-vasopressin gene (Avp) were bred to produce subjects expressing wildtype (WT), heterozygous (Het) and homozygous knockout (KO) variants of the Avp gene deletion. A total of 42 fecal samples (6 WT male, 8 WT female, 6 Het male, 7 Het female, 8 KO male, and 7 KO female) were collected with one sample per subject, from which DNA was amplified and sent for sequencing. After OTU picking and checking for chimeric transcripts, a total of 1,322,857 reads were assigned to 4,189 OTUs. Each sample had an average of 31,497 reads.

Differences in bacterial communities between Avp deletion genotypes

Gut microbial richness was not statistically different across the 3 Avp deletion genotypes. Between genotypes, we found no difference in any of the 3 measures of α-diversity, which measures community richness (Shannon's diversity index, observed species and Chao1), when all data points were combined nor when genotypes were analyzed for each sex separately (data not shown).

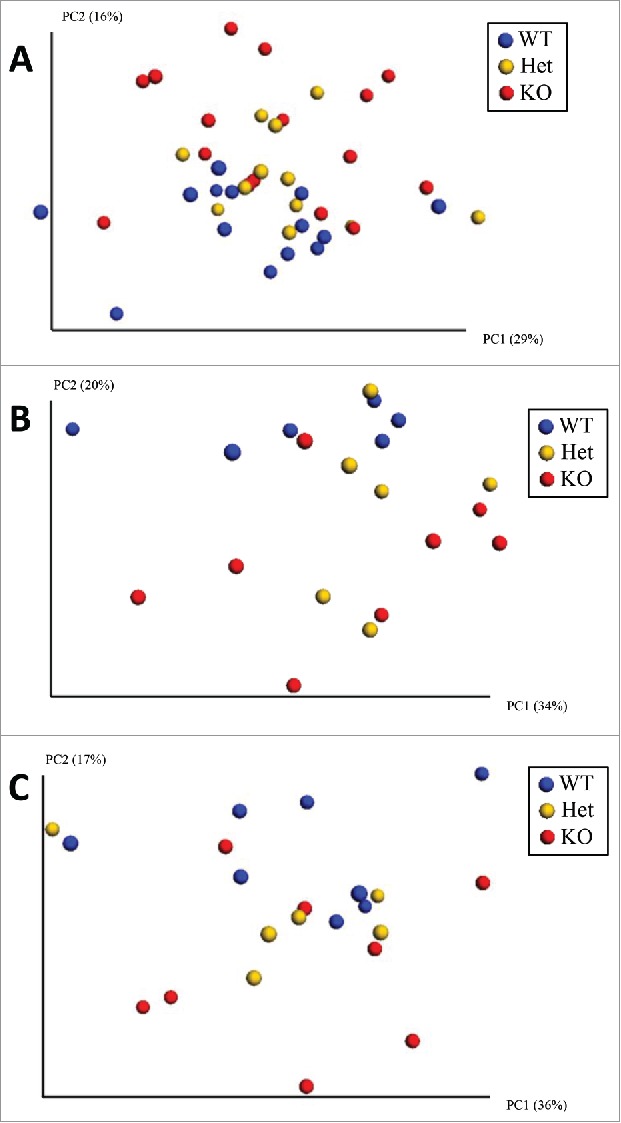

The relationships between global microbiota compositions were examined using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on weighted UniFrac distances. With males and females combined, weighted UniFrac-based cluster analysis revealed modest but differentiated microbiota compositions for each genotype (Fig. 1A). The observed clustering of each group was confirmed by PERMANOVA (p = 0.024). Separation between WT and KO samples was particularly evident when Het samples were excluded (Supplementary Figure). When males and females were analyzed independently, clustering by genotype was observed (Fig. 1B and C), with trends in differentiation by genotype for both males and females (p = 0.051 and 0.071, respectively). These data suggest that the microbial community structures found in the guts of WT, Het, and KO Brattleboro rats are differentiated across a limited number of taxa.

Figure 1.

Covariation of community structure using weighted UniFrac distances demonstrates limited clustering of samples by genotype when (A) both sexes are analyzed together [KO are clustered in upper right, WT are clustered in lower left, while Het are found in the middle; PERMANOVA, p< = 0.05] and when (B) males [PERMANOVA, p = 0.051] and (C) females [PERMANOVA, p = 0.071] are analyzed separately.

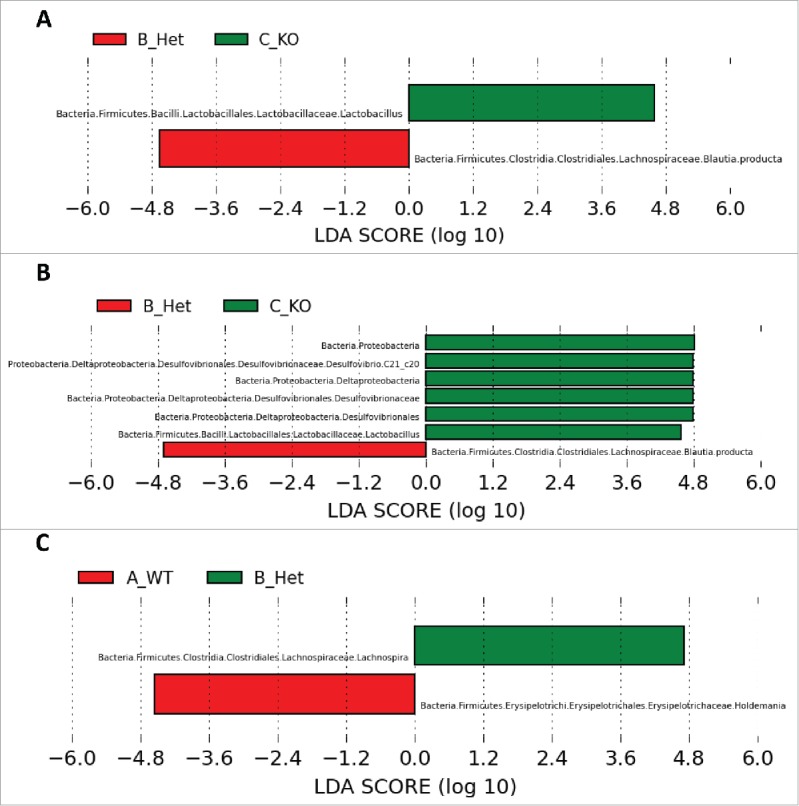

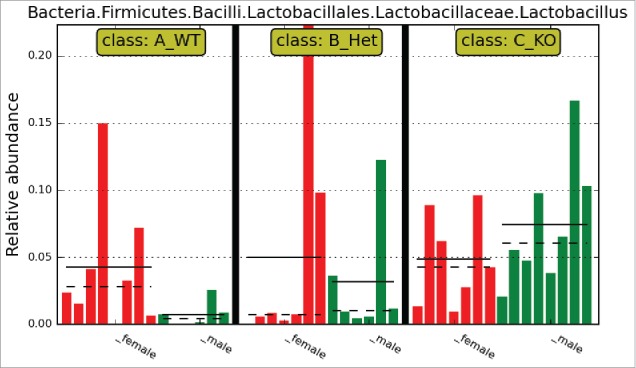

We used LEfSe to identify specific bacterial taxa that are significantly differentiated between groups. All features identified by LEfSe exceed an LDA score of 2.0, which indicates significant differences between groups. Figure 2 shows bacterial taxa differentially represented between genotypes identified with the one-against-all algorithm, which identifies taxa that are only differentiated in one genotype relative to the other 2 genotypes. When both sexes were analyzed together, Lactobacillus spp. were most abundant in KO rats and Blautia producta was most abundant in Het rats (Fig. 2A). When male samples were analyzed separately by genotype, the same taxa were differentiated, with the addition of Desulfovibrio c21_c20 being more abundant in KO rats (Fig. 2B). When female samples were analyzed independently, Lachnospira spp were most abundant in Het rats while Holdemania spp were most abundant in WT rats (Fig. 2C). Using the all-against-all algorithm within LEfSe, which identifies features that are significantly differentiated among all pairwise comparisons, we found zero significantly differentiated taxa between genotypes when both sexes were combined. However, when the sexes were analyzed separately, significantly differentiated taxa between genotypes were identical to those identified with the one-against-all algorithm. For example, Lactobacillus is significantly differentiated between all 3 genotypes among male rats but is not significantly differentiated among female rats (Fig. 3). The all-against-all LEfSe algorithm indicates that the relative abundance of Lactobacillus is differentiated across all 3 genotypes for males (LDA score = 4.6), and the average abundance for each class increases with haploid and diploid deletion of the Avp gene. In keeping with differentiated clustering of Het animals identified via PCoA plots, this LDA analysis suggests that Het rats harbor a microbiota that is differentiated from that found in WT and KO rats, particularly for these bacterial taxa.

Figure 2.

Bacterial taxa significantly differentiated between genotypes identified by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe). (A) shows differentiated taxa between WT, Het, and KO rats when males and females are combined. (B) and (C) show differences between genotypes for males and females, respectively. All LDA scores exceed 2.0, which is the threshold for significantly differentiated features.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of Lactobacillus taxon between genotypes. All-against-all algorithm of Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe) identifies this taxon as significantly differentiated between all genotypes [WT, Het, and KO] for male rats. (LDA score = 4.6, which exceeds the score threshold of 2.0, indicating statistical significance). Neither the all-against-all or one-against-all algorithms detect Lactobacillus as a significantly differentiated taxon between genotypes for female rats.

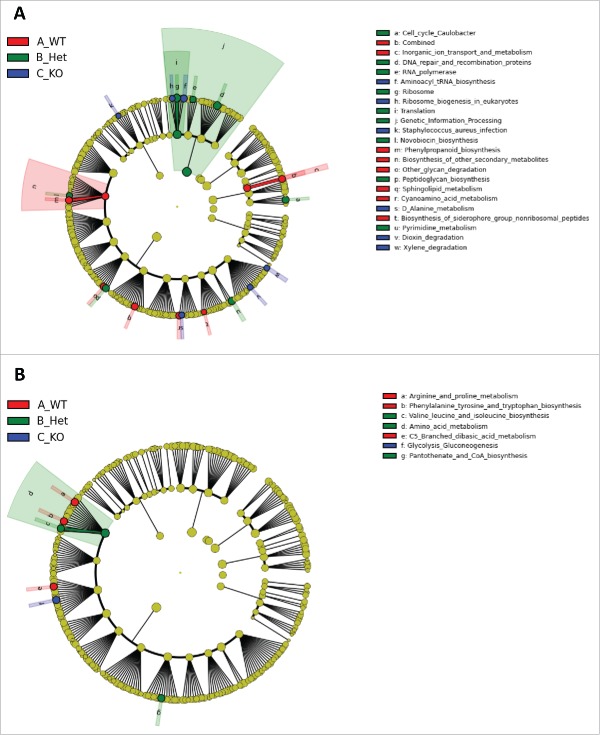

Using PICRUSt (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States), we explored the predicted functional consequences of these compositionally differentiated microbiota for males and females separately. The OTU table was normalized by 16S rRNA copy number and gene pathways were predicted using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. This generated the pathway abundance table that was analyzed by LEfSe. Males show more differentiation in pathways between genotypes. In males, 6 pathways were most abundant in KO rats (e.g. “Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes,” aminoacyl tRNA biosynthesis,” “Xylene degradation, ” etc.), 9 pathways most abundant in Het rats (e.g., “Genetic information processing,” “Translation,” and “Ribosome,” etc.) and 8 pathways most abundant in WT rats (e.g., “Other glycan degradation,” “Sphingolipid metabolism,” “Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites,” etc.) (Fig. 4A). Between female rats, “Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis” was most abundant in KO rats, “Amino acid metabolism,” “Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis,” and “Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis” were most abundant in Het rats, and “Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis,” “Arginine and proline metabolism,” and “C5 branched dibasic acid metabolism” were most abundant in WT rats (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Cladogram of gene pathways significantly differentiated between genotypes identified by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe). The innermost ring represents KEGG Level 1 pathways, the middle ring represents KEGG Level 2 pathways, and the outermost ring represents KEGG Level 3 pathways. (A) and (B) show predicted functional differences between genotypes [WT, Het, and KO] for males and females, respectively. All highlighted pathways have LDA scores that exceed 2.0, which is the threshold for significantly differentiated features.

Differences in bacterial communities between sexes

When considering overall community composition via PCoA analysis, we observed no sex differences in gut microbiota. When we compared α-diversities between sexes with all of the genotypes combined, or between sexes for each separate genotype, no significant differences in species diversity were observed. No sex differences in overall community composition were identified via PCoA analysis of all of the samples combined, or for any of the 3 separate genotypes (data not shown).

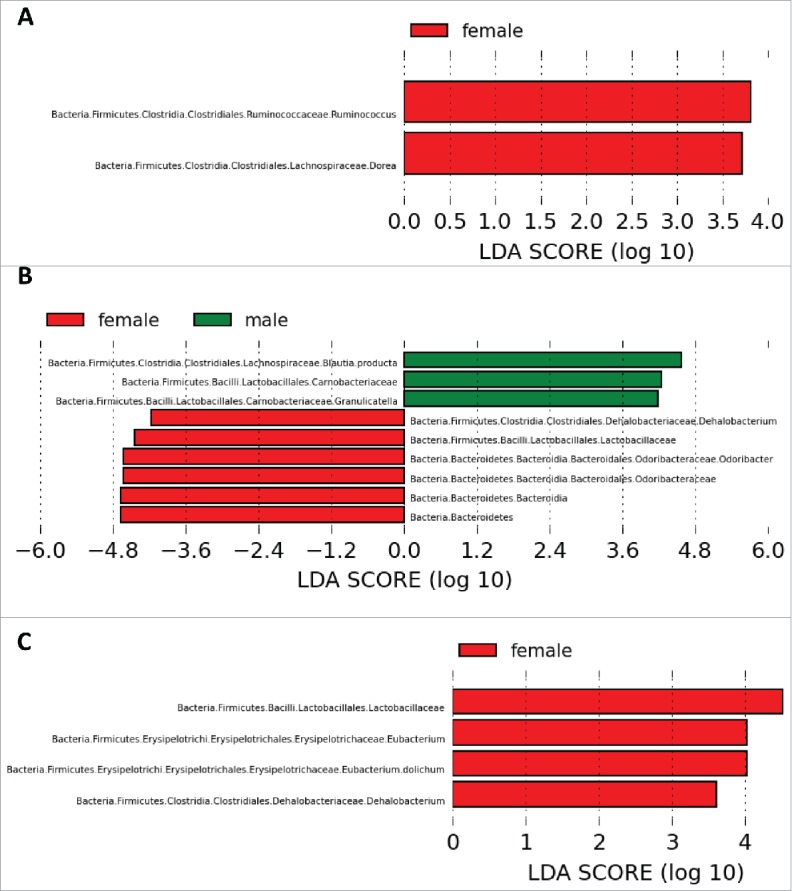

At the level of individual taxa (as analyzed via LEfSe), we were able to identify sex differences across all 3 genotypes. Between WT males and females, Dorea spp and Ruminococcus spp were more abundant in female rats (Fig. 5A). This sex difference in community composition was altered in Het and KO rats. Among Het rats, Odoribacter spp, Lactobacillaceae spp and Dehalobacterium spp were more abundant in females, whereas Granulicatella spp and Blautia producta were more abundant in males (Fig. 5B). Among KO rats, Lactobacillaceae spp, Dehalobacterium spp, and Eubacterium dolichum were more abundant in females (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Bacterial taxa significantly differentiated between sexes identified by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe). Differentiated taxa between males and females of the (A) WT, (B) Het and (C) KO genotypes are shown. All LDA scores exceed 2.0, which is the threshold for significantly differentiated features.

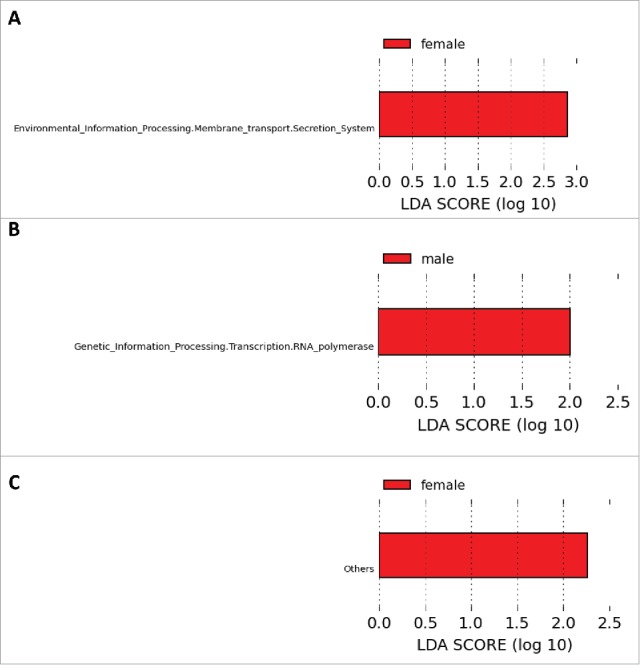

The metabolic potentials between sexes for each genotype were explored using PICRUSt-generated BIOM tables analyzed via LEfSe. We were only able to identify one gene pathway category that was sexually differentiated across each of the 3 distinct genotypes. In WT rats, “Secretion Systems” predominated in females (Fig. 6A), whereas in Het rats, “RNA polymerase” pathways were more abundant in males (Fig. 6B). These pathways were not sexually differentiated in KO rats, where an unclassified group of pathways was more abundant in females (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Gene pathways significantly differentiated between sexes identified by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe). Differentiated taxa between males and females of the (A) WT, (B) Het and (C) KO genotypes are shown. All highlighted pathways have LDA scores that exceed 2.0, which is the threshold for significantly differentiated features.

Discussion

This study is the first to identify differences in gut microbiota between arginine-vasopressin (AVP) deletion genotypes: namely homozygous (KO), heterozygous (Het) and wildtype (WT) Brattleboro rats. We found differences in microbiota across all 3 genotypes, suggesting that Avp is haploinsufficient to restore microbiota observed in WT rats. Interestingly, we also found that sex differences in gut microbiota were affected by Avp genotype.

Breeding genetic knockout and WT colonies in isolation may result in compositional differences in gut microbiota that are not truly reflective of genotype effects on microbiota composition.12 We avoided this confounding effect by generating all genotypes used in this study from heterozygous breeding pairs. To ensure that fecal samples were only collected from the subject animal and not from a cagemate, subject animals were single housed for 18–24 hours before sample collection. Single housing can affect stress reactivity,13 and chronic stress exposure could potentially alter microbiota composition.14 We reasoned that a 24-hour separation would not significantly alter microbiota composition, as large-scale differentiation of microbiota composition requires several days in other models14–16 All animals were subjected to the same single housing protocol.

Our data suggest that haploid or diploid expression of the Avp gene differentially affects the abundance of specific bacterial taxa, and that it does so in a sex-specific manner. Microbial differences were detected with QIIME via PCoA analysis to determine whether large scale microbial population differences exist between groups17 and with LEfSe, a very conservative biomarker discovery tool which detects the most robust taxa and pathway differences most likely to explain differences in host physiology and behavior between groups.18,19 Both PCoA analysis and LEfSe indicate that each genotype is significantly differentiated from the others. Also, females exhibit a separate set of differentially abundant taxa between genotypes relative to those found in males. Unique findings of sex-specific compositional differences between genotypes are supported by analysis of microbiota composition by sex. The sexually differentiated taxa found in WT rats are not observed in Het and KO rats, and vice versa. PICRUSt analysis, which demonstrates differences in the functional capacity of gut microbiota, also suggests a differentiated microbiota for Het rats and highlights the effects of subject sex on genotype differences in microbiota composition. It is important to note that while PICRUSt has demonstrated a high level of predictive validity in mammalian microbial samples, PICRUSt analyzes data from a “closed-reference” subset of the original community composition BIOM table, and the accuracy of PICRUSt predictions still lie between 60–90% for mammals.20

KO rats show less anxiety behavior than WT rats.6 Our data suggest this may, in part, be driven by the higher abundance of Lactobacillus spp found in the gut microbiota of KO rats relative to WT rats. Oral administration of Lactobacillus spp decreases anxiety behavior in mice and rats.21–27 Of note, male Het rats show levels of Lactobacillus spp intermediate to those found in male WT and male KO rats. As Avp has been shown to be haploinsufficient in restoring normal working memory28 and in selective parameters of developmental behavior,29 a thorough investigation of differences in other behaviors, such as anxiety behavior, between Het and WT rats is warranted. The anxiety modulating properties of Desulfovibrio spp and Blautia producta, most abundant in KO and Het rats respectively, have not been investigated in conventional WT rats. However, a gnotobiotic mouse model solely colonized with a Blautia sp. demonstrates decreases in marble burying behavior and moderate decreases in time spent in the periphery of the open field test relative to germ-free mice, suggesting decreases in repetitive and anxiety-like behaviors in these mice.30 This is particularly notable, as germ-free mice show decreased anxiety-like behavior with respect to conventionally colonized mice.31,32

Some differentiated taxa that have been associated with weakened immune systems or with pro-inflammatory states are more abundant in KO or WT rats, respectively. AVP is important for shaping immune responses, and rats with a homozygous Avp deletion harbor a hyporesponsive immune system, showing deficits in macrophage activation, IgG antibody response, a smaller spleen and premature involution of the thymus.33 Desulfovibrio c21_c20, found most abundantly in male KO rats relative to male WT rats, is a bacterial species of the Proteobacteria phylum, which has been found to be highly abundant in mice with a disruption in their innate immune system (namely, toll-like receptor 5 which recognizes flagellated bacteria).34 Between female rats, Lachnospira spp are most abundant in Het rats and Holdemania spp are most abundant in WT rats. Holdemania is a genus of the Erysipelotrichales order; Erysipelotrichales bloom in response to a high-fat diet,35 which has been shown to promote intestinal inflammation. Children with asthma have a lower abundance of Lachnospira spp in their gut microbiota, and germ-free mice colonized with a Lachnospira species show decreases in airway inflammation.36 Given the 2-way relationship between microbiota and the immune system,37,38 it is possible that Lachnospira spp suppress inflammation in a manner that promotes further replication of Lachnospira spp in female KO rats.

One mechanism by which Avp deletion may alter gut microbiota is via regulation of water consumption. Drinking water conditions, such as the pH of consumed water, can alter gut microbiota.39,40 As AVP is important for water retention, Brattleboro rats display signs of diabetes insipidus, i.e. increased water intake and urine output. However, restoring systemic AVP levels via osmotic minipumps, which corrects water balance and diabetes symptoms, does not normalize anxiety and depressive behaviors in Brattleboro rats.6 In addition, the heterozygous Brattleboro condition is sufficient to correct for outward signs of diabetes insipidus,41,42 but the heterozygous condition is still unable to correct working memory deficits that are observed in homozygous knockout Brattleboro rats.28 This suggests diabetes symptoms, such as water consumption, are not the sole driver of behavioral differences between Brattleboro and WT rats.

There are other potential mechanistic links between AVP expression and microbiota composition. It is possible that maternal behaviors such as pup licking/grooming affect microbiota composition. KO Brattleboro dams have been demonstrated to exhibit maternal neglect, spending less time licking/grooming their pups than Het dams.43 However, all subjects in this study were raised by Het dams. Nevertheless, KO pups may elicit differing levels of maternal licking/grooming behavior than Het and WT rats. KO rats exhibit differing levels of ultrasonic calls relative to WT and Het rats29 and pup ultrasonic calls may be associated with rates of licking/grooming,44 which may potentially affect adult gut microbiota composition.

Moving from behavior to cellular biology, AVP may directly affect microbiota composition via receptors present on bacteria that may be structurally similar to host neurotransmitter/neuropeptide receptors.45 Indeed, many neurotransmitters are suggested to derive from bacterial origins through lateral gene transfer into the metazoan lineage.46 An in vitro study found that AVP was stable in a colonic environment devoid of fecal microbiota.47 Therefore, AVP may be metabolized by the microbiota in a manner that influences their growth, cell death, or functional output, and may subsequently affect the host.

AVP release, potentially both centrally and systemically, modulates the activity of immune cells,48,49 and AVP-producing nuclei are responsive to inflammatory stimuli.50 Many immune cells also express AVP receptors.51 Similar to AVP, gut microbiota both regulate, and are shaped by, the immune system.37,38 Therefore, there may be a bidirectional link between gut microbiota and AVP expression mediated by the immune system. Future studies could investigate differences in behavioral and cytokine profiles in germ-free rats administered microbiota from WT versus KO Brattleboro rats.

In summary, we characterized the gut microbiota of wildtype (WT) Long Evans rats and Long Evans rats carrying haploid (heterozygous, Het), or diploid (knockout, KO) deletions of the Avp gene (also known as Brattleboro Rats), and found a limited but potentially influential subset of significantly differentiated taxa that correspond with the immune status and anxiety behavior differences observed between WT and KO rats. Rats heterozygous for the Avp gene harbor a differentiated microbiota, which appears to be intermediate to that found in the guts of WT and KO rats. In addition, Avp gene deletion appears to affect the community composition of the gut microbiota of males and females in a sexually differentiated manner. Future studies should more fully explore the behavioral phenotype of Het rats relative to WT rats, and how sex differences in behavior are altered by Avp gene deletion.

Methods

Experimental design and fecal collection

Brattleboro rats carrying a homozygous (KO) or heterozygous (Het) deletion of the AVP gene against a Long-Evans background, along with wildtype (WT) Long-Evans rats, were bred from Het breeding pairs. Offspring from 11 litters resulting from 11 separate breeding pairs, all born within a 5-day span, were used in this study, yielding a total of 42 subjects. Upon weaning, all offspring were genotyped and pair-housed with the same genotype and sex. Prior to this study, at around 4 weeks of age, the rats were used in a play testing study.29 These rats endured no further manipulations before the study. All of the animals were pair-housed with the same genotype and sex at the beginning of the study. We did not want to disturb this pairing to avoid the additional confound of introducing socially novel cage mates, which may independently affect microbial composition. The rats were housed in 2 separate subspaces of a housing room with generally regular exposure to the same set of researchers and environmental cues. The rats were housed in cages with ALPHA-Dri bedding (Shepherd Specialty Papers, Kalamazoo, MI), fed non-autoclaved rodent chow (5001 Diet, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO), and kept on a 12L:12D light cycle.

At 12 weeks of age, subjects from each cage were chosen at random and were single housed into clean cages for 16–24 h. Three to four fecal pellets per cage were then collected with ethanol-cleaned forceps and promptly stored at -80°C. From each litter, no more than one rat per experimental group was used, with 7 of the 11 litters producing animals from all 3 genotypes used in the study. With the exception of 4 animals, cage mates were not used (i.e., only one rat per pair housed cage was used in the study).

DNA extraction and 16s rRNA sequencing

Fecal microbial 16s rRNA was sequenced according to the protocol outlined in Chassaing et al. (2015).16 Briefly, total bacterial DNA was isolated from feces using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to manufacturer's instructions, and was stored at -80°C before further analysis. The 16S rRNA genes, region V4, were PCR amplified using the 515F/806R primer set (see Chassaing et al. [2015] for full sequence).16 PCR reactions consisted of Hot Master PCR mix (Five Prime, San Francisco, CA), 0.2 μM of each primer, and 10–100 ng template. Reaction conditions were 3 minutes at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 45 seconds at 95°C, 60 seconds at 50°C and 90 seconds at 72°C on a Biorad thermocycler. PCR products were purified with Agencourt Ampure magnetic purification beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (paired-end reads, 2 × 250 base pairs) at Cornell University, Ithaca.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

The sequences were demultiplexed, quality filtered using the Qualitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME, version 1.8.0) software package, and forward and reverse reads were joined using the fastq-join method (http://code.google.com/p/ea-utils).52 Sequences were assigned to OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units, a proxy for species classification, grouping closely related individuals) using the UCLUST algorithm with a 97% threshold of pairwise identity, and classified taxonomically using the Greengenes reference database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov) using uclust method with the suppression of new clusters (closed reference OTU picking strategy). FastTree was used to generate a phylogenetic tree and to compute unweighted UniFrac distances per sample (http://microbesonline.org/fasttree/). OTUs that were assigned to only one read for a sample were excluded from analysis. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots, constructed with weighted UniFrac distances, were used to assess the variation between experimental groups (β-diversity) and jackknifed β diversity was used to estimate the uncertainty in PCoA plots. Metagenomic data prediction of the functional profiles of fecal microbial composition was generated using PICRUSt.20

Measures of α diversity were compared across groups using the Mann-Whitney U test of significance. Significant tests of β diversity difference between sample groups were obtained using PERMANOVA in QIIME. The program Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) coupled with Effect Size (LEfSe) was used to identify significantly differentiated bacterial taxa.18 LEfSe was also used to analyze differential abundance in gene pathways between microbial samples predicted by PICRUSt. Bootstrap Kruskal-Wallis-test was used to identify taxa or gene pathways with significantly differentiated abundance, with the LDA score computed with a bootstrapping algorithm repeated over 30 cycles, each sampling 2-thirds of the data with replacement. Unless otherwise stated, one-against-all multiclass analysis was used, and posthoc Wilcoxon pairwise comparisons among subclasses were only performed among identically named subclasses: in cross-genotype analyses, males were only compared with males and females only compared with females; in cross-sex analyses, subjects of the same genotype were compared with each other. The one-against-all algorithm detects whether at least one of the classes is significantly different from the other compared classes. However, the all-against-all algorithm detects whether all of the classes are significantly different from each other. The threshold on the logarithmic LDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis) score for discriminative features was set to 2.0 (indicating significant differential abundance between classes), and the α values for the factorial Kruskal-Wallis test among classes and the pairwise Wilcoxon test between subclasses were both set to 0.05.

Availability of data and material

The sequence data and mapping file for all the samples included in this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive and have been assigned accession number PRJEB19277.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- AVP

arginine-vasopressin

- Het

heterozygous

- KEGG

kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- KO

knockout

- LDA

linear discriminant analysis

- LEfSe

linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size

- OTU

operational taxonomic unit

- PICRUSt

phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states

- PCoA

principle coordinate analysis

- QIIME

quantitative insights into microbial ecology

- WT

wildtype

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GSU Department of Animal Resources for their expert animal care.

Funding

This work was supported by grants funded through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to ATG (5 R01 DK 083890) and GJD (R21 MH 108345).

Authors' contributions

CTF and BC performed the research and data analysis. CTF and MJP generated the colony. CTF wrote the manuscript. ATG and GJD funded the research and provided scientific guidance.

References

- [1].Knepper MA, Kwon TH, Nielsen S. Molecular physiology of water balance. N Eng J Med. 2015; 373:196; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMc1505505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Neumann ID, Landgraf R. Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2012; 35:649-59; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tins.2012.08.004; PMID:22974560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Joels M, Baram TZ. The neuro-symphony of stress. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009; 10:459-66. PMID:19339973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sokol HW, Zimmerman EA. The hormonal status of the Brattleboro rat. Annals N York Acad Sci. 1982; 394:535-48; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb37468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Surget A, Belzung C. Involvement of vasopressin in affective disorders. European J Pharmacol. 2008; 583:340-9; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Balazsfi D, Pinter O, Klausz B, Kovacs KB, Fodor A, Torok B, Engelmann M, Zelena D. Restoration of peripheral V2 receptor vasopressin signaling fails to correct behavioral changes in Brattleboro rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015; 51:11-23; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.011; PMID:25278460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Feifel D, Mexal S, Melendez G, Liu PY, Goldenberg JR, Shilling PD. The brattleboro rat displays a natural deficit in social discrimination that is restored by clozapine and a neurotensin analog. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009; 34:2011-8; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/npp.2009.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012; 13:701-12; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrn3346; PMID:22968153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Traplin A, O'Sullivan O, Crispie F, Moloney RD, Cotter PD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence in mice: implications for brain and behaviour. Brain Behavior Immunity. 2015; 48:165-73; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].de Vries GJ. Sex differences in vasopressin and oxytocin innervation of the brain. Progress Brain Res. 2008; 170:17-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Taylor PV, Veenema AH, Paul MJ, Bredewold R, Isaacs S, de Vries GJ. Sexually dimorphic effects of a prenatal immune challenge on social play and vasopressin expression in juvenile rats. Biol Sex Differences. 2012; 3:15; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/2042-6410-3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ubeda C, Lipuma L, Gobourne A, Viale A, Leiner I, Equinda M, Khanin R, Pamer EG. Familial transmission rather than defective innate immunity shapes the distinct intestinal microbiota of TLR-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2012; 209:1445-56; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20120504; PMID:22826298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Das SK, Barhwal K, Hota SK, Thakur MK, Srivastava RB. Disrupting monotony during social isolation stress prevents early development of anxiety and depression like traits in male rats. BMC Neurosci. 2015; 16:2; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12868-015-0141-y; PMID:25880744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stilling RM, Bordenstein SR, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Friends with social benefits: host-microbe interactions as a driver of brain evolution and development? Frontiers Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014; 4:147; https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mason KL, Erb Downward JR, Mason KD, Falkowski NR, Eaton KA, Kao JY, Young VB, Huffnagle GB. Candida albicans and bacterial microbiota interactions in the cecum during recolonization following broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Infect Immunity. 2012; 80:3371-80; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00449-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chassaing B, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Poole AC, Srinivasan S, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015; 519:92-6; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14232; PMID:25731162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Navas-Molina JA, Peralta-Sanchez JM, Gonzalez A, McMurdie PJ, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Xu Z, Ursell LK, Lauber C, Zhou H, Song SJ, et al.. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol. 2013; 531:371-444. PMID:24060131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011; 12:R60; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60; PMID:21702898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Paulson JN, Stine OC, Bravo HC, Pop M. Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys. Nat Methods. 2013; 10:1200-2; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.2658; PMID:24076764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Langille MG, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Vega Thurber RL, Knight R, et al.. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013; 31:814-21; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt.2676; PMID:23975157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:16050-5; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1102999108; PMID:21876150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liang S, Wang T, Hu X, Luo J, Li W, Wu X, Duan Y, Jin F. Administration of Lactobacillus helveticus NS8 improves behavioral, cognitive, and biochemical aberrations caused by chronic restraint stress. Neuroscience. 2015; 310:561-77; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.033; PMID:26408987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu WH, Chuang HL, Huang YT, Wu CC, Chou GT, Wang S, Tsai YC. Alteration of behavior and monoamine levels attributable to Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 in germ-free mice. Behavioural Brain Res. 2015; 298(Pt B):202-9. PMID:26522841; doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang T, Hu X, Liang S, Li W, Wu X, Wang L, Jin F. Lactobacillus fermentum NS9 restores the antibiotic induced physiological and psychological abnormalities in rats. Beneficial Microbes. 2015; 6:707-17; https://doi.org/ 10.3920/BM2014.0177; PMID:25869281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luo J, Wang T, Liang S, Hu X, Li W, Jin F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain reduces anxiety and improves cognitive function in the hyperammonemia rat. Science China Life Sci. 2014; 57:327-35; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11427-014-4615-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mackos AR, Eubank TD, Parry NM, Bailey MT. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri attenuates the stressor-enhanced severity of Citrobacter rodentium infection. Infect Immunity. 2013; 81:3253-63; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00278-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ohland CL, Kish L, Bell H, Thiesen A, Hotte N, Pankiv E, Madsen KL. Effects of Lactobacillus helveticus on murine behavior are dependent on diet and genotype and correlate with alterations in the gut microbiome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013; 38:1738-47; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.02.008; PMID:23566632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Aarde SM, Jentsch JD. Haploinsufficiency of the arginine-vasopressin gene is associated with poor spatial working memory performance in rats. Hormones Behavior. 2006; 49:501-8; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.11.002; PMID:16375903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Paul MJ, Peters NV, Holder MK, Kim AM, Whylings J, Terranova JI, de Vries GJ. Atypical social development in Vasopressin-Deficient Brattleboro Rats. eNeuro. 2016; 3:pii: ENEURO.0150-15.2016; https://doi.org/ 10.1523/ENEURO.0150-15.2016; PMID:27066536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nishino R, Mikami K, Takahashi H, Tomonaga S, Furuse M, Hiramoto T, Aiba Y, Koga Y, Sudo N. Commensal microbiota modulate murine behaviors in a strictly contamination-free environment confirmed by culture-based methods. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013; 25:521-8; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/nmo.12110; PMID:23480302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011; 23:255-64, e119; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x; PMID:21054680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Bjorkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:3047-52; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1010529108; PMID:21282636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Khegai II, Gulyaeva MA, Popova NA, Zakharova LA, Ivanova LN. Immune system in vasopressin-deficient rats during ontogeny. Bulletin Exp Biol Med. 2003; 136:448-50; https://doi.org/ 10.1023/B:BEBM.0000017089.28428.1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Carvalho FA, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Johansson ME, Nalbantoglu I, Aitken JD, Su Y, Chassaing B, Walters WA, González A, et al.. Transient inability to manage proteobacteria promotes chronic gut inflammation in TLR5-deficient mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2012; 12:139-52; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.004; PMID:22863420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Magnusson KR, Hauck L, Jeffrey BM, Elias V, Humphrey A, Nath R, Perrone A, Bermudez LE. Relationships between diet-related changes in the gut microbiome and cognitive flexibility. Neuroscience. 2015; 300:128-40; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.016; PMID:25982560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, Thorson L, Russell S, Yurist-Doutsch S, Kuzeljevic B, Gold MJ, Britton HM, Lefebvre DL, et al.. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Translational Med. 2015; 7:307ra152; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tomkovich S, Jobin C. Microbiota and host immune responses: a love-hate relationship. Immunology. 2015; 147(1):1-10. PMID:26439191; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/imm.12538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lei YM, Nair L, Alegre ML. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the immune system. Clinics Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015; 39:9-19; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sofi MH, Gudi R, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Johnson BM, Vasu C. pH of drinking water influences the composition of gut microbiome and type 1 diabetes incidence. Diabetes. 2014; 63:632-44; https://doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-0981; PMID:24194504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wolf KJ, Daft JG, Tanner SM, Hartmann R, Khafipour E, Lorenz RG. Consumption of acidic water alters the gut microbiome and decreases the risk of diabetes in NOD mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014; 62:237-50; https://doi.org/ 10.1369/0022155413519650; PMID:24453191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Opava-Stitzer S, Fernandez-Repollet E, Stern P. Sodium and potassium balance in the Brattleboro rat. Annals N York Acad Sci. 1982; 394:188-208; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb37428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Laycock JF. The Brattleboro rat with hereditary hypothalamic diabetes insipidus. General Pharmacol. 1977; 8:297-302; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0306-3623(77)90002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fodor A, Klausz B, Pinter O, Daviu N, Rabasa C, Rotllant D, Balazsfi D, Kovacs KB, Nadal R, Zelena D. Maternal neglect with reduced depressive-like behavior and blunted c-fos activation in Brattleboro mothers, the role of central vasopressin. Hormones Behavior. 2012; 62:539-51; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.09.003; PMID:23006866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Brouette-Lahlou I, Vernet-Maury E, Vigouroux M. Role of pups' ultrasonic calls in a particular maternal behavior in Wistar rat: pups' anogenital licking. Behavioural Brain Res. 1992; 50:147-54; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-4328(05)80296-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Corringer PJ, Poitevin F, Prevost MS, Sauguet L, Delarue M, Changeux JP. Structure and pharmacology of pentameric receptor channels: from bacteria to brain. Structure. 2012; 20:941-56; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.003; PMID:22681900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Iyer LM, Aravind L, Coon SL, Klein DC, Koonin EV. Evolution of cell-cell signaling in animals: did late horizontal gene transfer from bacteria have a role? Trends Genetics. 2004; 20:292-9; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tig.2004.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wang J, Yadav V, Smart AL, Tajiri S, Basit AW. Stability of peptide drugs in the colon. European J Pharmaceutical Sci. 2015; 78:31-6; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hu SB, Zhao ZS, Yhap C, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Westphal H, Gold P. Vasopressin receptor 1a-mediated negative regulation of B cell receptor signaling. J Neuroimmunol. 2003; 135:72-81; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00442-3; PMID:12576226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shibasaki T, Hotta M, Sugihara H, Wakabayashi I. Brain vasopressin is involved in stress-induced suppression of immune function in the rat. Brain Res. 1998; 808:84-92; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00843-9; PMID:9795154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nava F, Carta G, Haynes LW. Lipopolysaccharide increases arginine-vasopressin release from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus slice cultures. Neurosci Letters. 2000; 288:228-30; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01199-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Russell JA, Walley KR. Vasopressin and its immune effects in septic shock. J Innate Immunity. 2010; 2:446-60; https://doi.org/ 10.1159/000318531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al.. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010; 7:335-6; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nmeth.f.303; PMID:20383131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.