Key Points

MCMV induces type 1 IFN that alters the differentiation of MDSCs critical for transplantation tolerance.

Abstract

Clinical tolerance without immunosuppression has now been achieved for organ transplantation, and its scope will likely continue to expand. In this context, a previously understudied and now increasingly relevant area is how microbial infections might affect the efficacy of tolerance. A highly prevalent and clinically relevant posttransplant pathogen is cytomegalovirus (CMV). Its impact on transplantation tolerance and graft outcomes is not well defined. Employing a mouse model of CMV (MCMV) infection and allogeneic pancreatic islet transplantation in which donor-specific tolerance was induced by infusing donor splenocytes rendered apoptotic by treatment with ethylenecarbodiimide, we investigated the effect of CMV infection on transplantation tolerance induction. We found that acute MCMV infection abrogated tolerance induction and that this abrogation correlated with an alteration in the differentiation and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). These effects on MDSCs were mediated in part through MCMV induced type 1 interferon (IFN) production. During MCMV infection, the highly immunosuppressive Gr1HI-granulocytic MDSCs were markedly reduced in numbers, and the accumulating Ly6CHI-monocytic cells lost their MDSC-like function but instead acquired an immunostimulatory phenotype to cross-present alloantigens and prime alloreactive CD8 T cells. Consequently, the islet allograft exhibited an altered effector to regulatory T-cell ratio that correlated with the ultimate graft demise. Blocking type 1 IFN signaling during MCMV infection rescued MDSC populations and partially restored transplantation tolerance. Our mechanistic studies now provide a solid foundation for seeking effective therapies for promoting transplantation tolerance in settings of CMV infection.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a highly prevalent viral pathogen whose infection in immunocompetent individuals is generally mild or asymptomatic.1 However, in immune-suppressed hosts such as in transplant recipients, CMV infection can cause significant morbidity and mortality, and has long been associated with acute and chronic allograft dysfunction,2-4 and therefore remains a major health hazard.2,5 An important factor that facilitates CMV infection and its replication in transplant recipients is impaired host antiviral immunity because of indefinite use of immunosuppression.6 Clinically, donor-specific tolerance has now been achieved in transplant recipients.7-11 This could potentially eliminate the need for indefinite immunosuppression, therefore minimizing the risk for CMV infection. However, the reciprocal impact of CMV infection on the ability to induce and/or maintain transplantation tolerance has not been studied.

Currently, successful clinical tolerance protocols involve donor bone marrow (BM) transplantation and chimerism induction. Such protocols, without an exception, require recipient conditioning with chemotherapeutic agents, which carry significant toxicities12 and may directly impact allograft function.13 Alternatively, we have shown that donor splenocytes simply treated with the chemical cross-linker ethylenecarbodiimide (ECDI-SPs) effectively undergo apoptosis and, when infused IV in recipients, readily induce robust donor-specific tolerance in murine models of allogeneic and xenogeneic transplantation.14-20 Recently, 2 independent studies have demonstrated the remarkable safety and efficacy of this approach of antigen delivery via apoptotic cells for immune tolerance induction in human BM transplantation and multiple sclerosis.21,22 Employing this approach, we have previously shown that infusion of ECDI-SP induces CD11b+ cells phenotypically and functionally resembling myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs).18 MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of immature cells largely composed of 2 subpopulations in mice (ie, CD11b+Gr1HI granulocytic-MDSCs and CD11b+Ly6CHI monocytic-MDSCs).23 In multiple transplant settings, MDSCs have been critically implicated in promoting transplantation tolerance by infiltrating transplanted allografts and locally subverting alloreactive T-cell activation.18,24

In the current study, we used murine CMV (MCMV) infection in an ECDI-SP tolerance model to investigate the impact of this highly clinically relevant pathogen on the induction of donor-specific tolerance and its effects on MDSCs via type 1 interferon (IFN) production as a mechanism of tolerance disruption.

Materials and methods

Mice

Eight- to 10-week-old male BALB/c and C57BL/6 (B6) mice were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed under specific-pathogen–free conditions and used according to approved protocols by Northwestern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Islet transplantation

Mice were rendered diabetic by streptozotocin (Sigma Aldrich). Islet transplantation was performed as described.14 Graft function was monitored by blood glucose using OneTouch glucometer (LifeScan Inc.). Rejection was confirmed when 2 consecutive readings were >250 mg/dL.

MCMV infection

Mouse CMV strain Δm157 was a gift from Michael Abecassis (Northwestern University). Working stocks were prepared as described.25,26 Recipients were infected (108 plaque-forming units; intraperitoneally [IP]) on indicated days.

Apoptotic cell preparation

Donor-specific tolerance was induced by IV injection of ECDI-SPs.14,15 Briefly, splenocytes were incubated with ECDI (Calbiochem) (3.2 × 108 cells per mL with 30 mg/mL ECDI) on ice for 1 hour followed by washing and IV injection (1 × 108 cells per mouse) on indicated days.

Anti-IFNAR1 antibody and recombinant IFN-α treatment

Anti-IFNAR1 antibody (MAR1-5A3; BioXCell) or isotype antibody (mouse immunoglobulin G1) was given at 250 μg per mouse (IP) on indicated days. Recombinant mouse IFN-α (accession# NM_206870 expressed in Escherichia coli; BioLegend) was given at 400 U/g per day subcutaneously on indicated days. Control mice received phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

MDSC depletion

MDSCs were depleted via IP injections of anti-Gr1 antibody (RB6-8C5; BioXCell) as described.18 Control mice received isotype antibody (rat immunoglobulin G2b).

Adoptive transfer of Gr1HI MDSCs

Gr1HI MDSCs were sorted from BM and spleens of naïve B6 mice using biotin-labeled anti-Gr1 antibody (Miltenyi). Purity of sorted Gr1HI cells by this method was routinely >90% with very few Ly6CHI cells. Gr1HI cells (30 × 106; equivalent to the number of Gr1HI cells pooled from spleen and BM of 1 naïve mouse) were injected IV on the indicated days.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes on ice, washed, acquired on CantoII (BD Biosciences), and analyzed using FlowJo V.10.1 (Tree Star LLC). For intracellular staining, cells were permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm buffers (BD) followed by staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Antibodies used were as follows: Gr1-eFluor780 (RB6-8C5), CD11c–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (HL3), CD86-allophycocyanin (APC) (16-10A1), CD11b-phycoerythrin (PE), PerCPCy5.5 (M1/70), Ly6C-eFluor450 (HK1.4), F4/80-PECy7 (BM8), major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II)–FITC (MS/114.15.2), interleukin 12 (IL-12)–PE (C17.8), CD4-eFluor450 (GK1.5), CD8-PerCPCy5.5 (53-6.7), CD3-FITC (17A2), and FcγRII/III-FITC (93), all from eBioscience; and Ly6G-APCCy7 (1A8) and C5aR-PECy7 (20/70), from BioLegend. Dead cells were excluded using Aqua live/dead dye (Molecular Probes).

T-cell proliferation

Splenic Gr1HI and Ly6CHI cells were obtained using the MDSC isolation kit per the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi). Magnetic-activated cell sorted CD8 T cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Life Technologies), seeded at 104 per well, and cocultured with 104 anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads and indicated numbers of Gr1HI or Ly6CHI cells. T-cell proliferation was determined by CFSE dilution after 72 to 96 hours. For alloantigen cross-presentation, CFSE-labeled CD8 T cells were seeded at 33 × 104/well and cultured with 166 × 104 splenic Ly6CHI cells from indicated mice in the presence of donor splenocyte lysates (50 µg/mL), followed by measuring CFSE dilution in 96 hours.

BM cell culture

BM was flushed from long bones of naïve B6 mice. Single cell suspension was magnetic-activated cell sorted for lineage negative (Lin−) cells to a purity of >97% per the manufacturer’s protocol (Lineage Depletion Kit, Miltenyi). Sorted cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antimicrobials) for 2 days in the presence of recombinant IFN-α (100 U/mL; PBL Assay Science) or PBS. Following cultures, cells were stained with CD11b-APC, lineage markers (CD3, CD19, NKp46, and Ter-119) conjugated with PerCPCy5.5 as a dump channel, Gr1-eF780, Ly6C-eF450, CD11c-FITC, and IRF8-PE, and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

IFN-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum IFN-α levels were determined using mouse IFN-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (PBL Assay Science).

MCMV DNA detection

DNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (ABI Prism 7500) was performed in triplicates using TaqMan master mix.27 Primers and TaqMan probes were as follows: MCMV major-immediate-early protein (MIEP): 5′GGTGGTCAGACC-GAAGACT 3′ (forward), 5′GCTGAGCTGCGTTCTACGT 3′- (reverse), 5′CTGGTCGCGCCTCTTA 3′ (probe); mouse β-actin: 5′CGTTCCGAAAGTTGCCTTTTA 3′ (forward), 5′GCCGCCGG-GTTTTATAGG 3′ (reverse), 5′CTCGAGTGGCCGCTG 3′ (probe). Cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 minutes and 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 5.0a (GraphPad Inc.). Data were analyzed using nonparametric Student t test (Mann-Whitney U test for 2 groups) or analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis for 3 groups). Graft-survival was analyzed using log-rank test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Acute MCMV infection impairs induction of transplantation tolerance

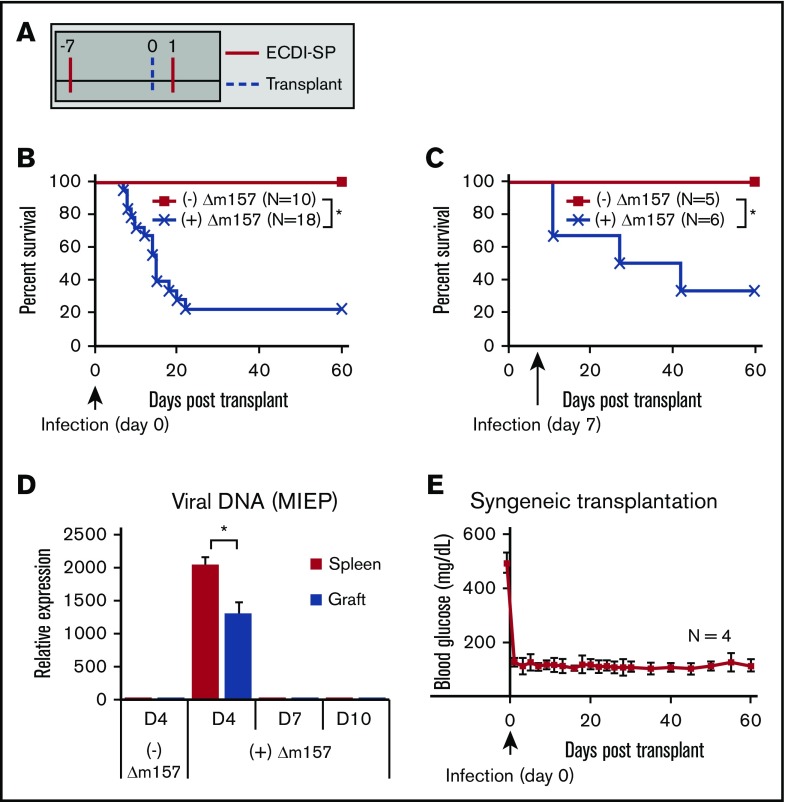

We first examined the effect of acute MCMV infection on tolerance induction in a mouse model of allogeneic islet transplantation. Donor-specific tolerance was induced by IV infusion of donor splenocytes treated with ECDI (ECDI-SP) on days −7 and +1, with day 0 being the day of transplantation (Figure 1A) as previously described.14,15,18,20 Infusion of donor ECDI-SP in uninfected recipients induced transplantation tolerance and promoted indefinite islet allograft survival (Figure 1B). We used the Δm157 strain of MCMV to infect transplant recipients. Δm157 is a mutated strain of MCMV that lacks the m157 glycoprotein recognized by the natural killer cell Ly49H receptor and therefore has improved virulence in B6 mice compared with wild-type MCMV.28 Acute Δm157 infection (108 plaque-forming units, day 0) of donor ECDI-SP–treated, otherwise tolerized recipients resulted in acute rejection of the majority of islet allografts within 2 to 3 weeks (Figure 1B). Furthermore, delaying Δm157 infection to day 7 posttransplantation also resulted in eventual rejection of ∼70% islet allografts, although over a more extended period (Figure 1C). To determine whether direct viral cytopathogenic effects on islets could be the cause of acute islet graft loss in Δm157-infected recipients, we performed syngeneic islet transplant (B6 to B6) in recipients acutely infected with the same dose of Δm157 on day 0. In these recipients, measurement of MCMV MIEP DNA in islet isografts revealed viral presence on day 4 and clearance by day 7 postinfection, a pattern similar to that of the spleen (Figure 1D). Despite direct viral infection of islets, function of the islet isograft remained intact over a prolonged period (Figure 1E). These data ruled out the possibility that direct islet infection by Δm157 caused islet graft loss, instead pointing to interference of tolerogenic pathways by ECDI-SP as the underlying cause of tolerance abrogation by the virus.

Figure 1.

Acute MCMV (Δm157) infection abrogates tolerance induction by donor ECDI-SPs. (A) Schematic treatment plan of tolerance induction in B6 transplant recipients. Donor (Balb/c) ECDI-SPs (1×108) were infused IV on day −7 and +1. Approximately 200 Balb/c islets were implanted in the kidney capsule of diabetic B6 recipients on day 0. (B) Percent graft survival of islet allografts in uninfected or Δm157-infected recipients, with the infection given on day 0. Data shown in panel B were from at least 5 independent experiments with a total of 10 to 18 mice in each group. (C) Percent graft survival of islet allografts in uninfected or Δm157-infected recipients, with the infection given on day 7. Data shown in panel C were from 2 independent experiments with a total of 5 to 6 mice in each group. (D) Detection of MCMV DNA in the spleen and islet isograft following Δm157 infection. MCMV MEIP gene was quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data were normalized to values from tissues of uninfected hosts and presented as mean ± SD (N = 4). (E) Sygeneic transplantation. Percent graft survival of islet isografts in uninfected or Δm157-infected recipients, with the infection given on day 0. *P < .05 (log-rank test). Data presented in panels D and E were compiled from 2 independent experiments with a total of 4 mice in each group.

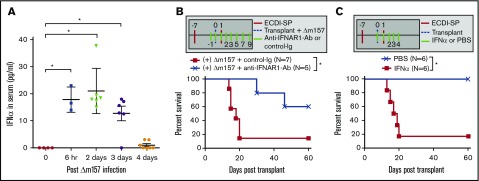

MCMV infection interferes with transplant tolerance via IFN-α production

IFN-α production in response to MCMV infection is crucial for host antiviral immunity29,30 and homeostasis.31 In our model of acute Δm157 infection, we found that IFN-α in circulation peaked by day 2 and subsided by day 4 postinfection (Figure 2A). Considering the immunostimulatory nature of IFN-α,32 we hypothesized that MCMV-induced IFN-α may underlie the observed tolerance abrogation seen in our model. To test this hypothesis, we first examined if blocking its receptor could improve the efficacy of donor ECDI-SPs in infected recipients. IFN-α signals through heterodimeric receptors IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. A blocking antibody to IFNAR1 (anti-IFNAR1-Ab) was given for the period spanning Δm157 infection and the ensuing IFN-α production to allogeneic islet transplant recipients treated with donor ECDI-SPs as shown in Figure 2B. This treatment alone was indeed sufficient to restore tolerance efficacy by donor ECDI-SPs in a substantial proportion of recipients acutely infected with Δm157 (Figure 2B). Reciprocally, we treated transplant recipients otherwise tolerized by donor ECDI-SPs with recombinant IFN-α instead of acute Δm157 infection. As shown in Figure 2C, similar to Δm157 infection, IFN-α also resulted in rapid rejection of islet allografts in ∼80% of recipients otherwise tolerized by donor ECDI-SPs. Collectively, these findings suggest that MCMV-induced type 1 IFN is the underlying cause of tolerance abrogation seen in our model.

Figure 2.

Acute MCMV infection induces type 1 IFN that impairs tolerance induction by donor ECDI-SPs. (A) Kinetics of serum IFN-α level post–MCMV infection (N = 4-6, compiled from 4 independent experiments). (B) Schematic treatment plan and percent graft survival with anti-IFNAR1-Ab blockade. Two cohorts of ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients were infected with Δm157 on the day of transplantation. The first cohort additionally received anti-IFNAR1 blocking antibody (IP injection; 250 µg/mouse per day) on the indicated days, while the other cohort additionally received isotype antibody on the same indicated days (N = 5-7, compiled from 3 independent experiments). (C) Schematic treatment plan and percent graft survival with recombinant IFN-α treatment. Two cohorts of ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients were additionally treated with vehicle (PBS) or mouse recombinant IFN-α (400 U/g per day) on the indicated days (N = 6, compiled from 2 independent experiments). *P < .05 (log-rank test).

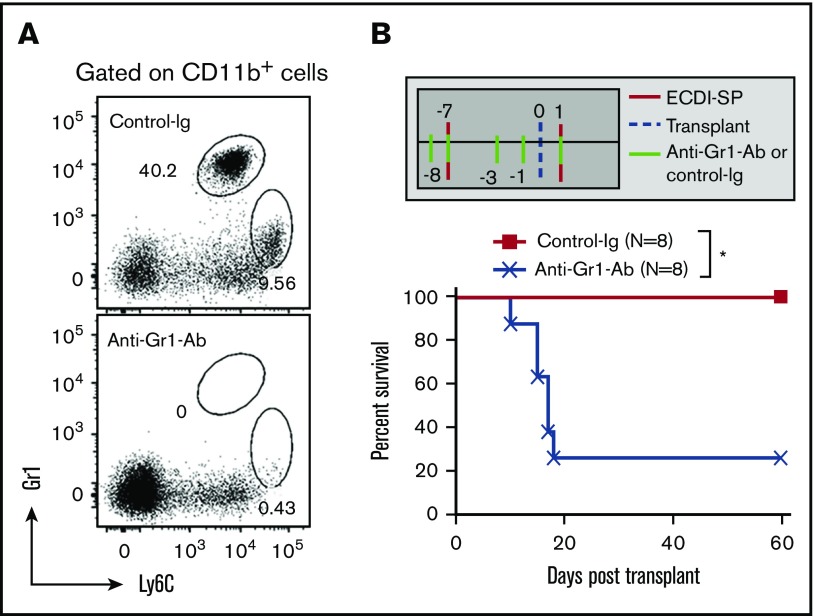

ECDI-SP–mediated tolerance to allogeneic islets requires MDSCs

Generated in the BM, MDSCs can be divided into 2 subpopulations in mice: Gr1HI-MDSCs and Ly6CHI-MDSCs. Both have been implicated in promoting allograft tolerance by inhibiting T-cell responses.24,33 We hypothesized that Δm157 may critically alter the differentiation of MDSC subpopulations, leading to abrogation of tolerance otherwise induced by donor ECDI-SPs. To test this, we first examined whether MDSCs were indeed required for tolerance induction to allogeneic islets by donor ECDI-SPs. As shown in Figure 3A (with gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 1), anti-Gr1-Ab thoroughly depleted both Gr1HI and Ly6CHI-MDSCs as previously reported.16,18 Furthermore, depletion of MDSCs resulted in acute rejection of the islet allograft in ∼80% of recipients treated with donor ECDI-SPs (Figure 3B), similar to what we previously observed in cardiac allograft recipients.16,18 These data highlight the critical role of MDSCs in tolerance induction by donor ECDI-SPs in our current model of allogeneic islet transplantation.

Figure 3.

MDSCs are critical for tolerance induction to allogeneic islets by donor ECDI-SPs. (A) Representative FACS plots depicting depletion of both populations of MDSCs (Gr1HI-granulocytic MDSCs and Ly6CHI-monocytic MDSCs) in the blood by the anti-Gr1 antibody. Upper panel: mice treated with isotype control antibody. Lower panel: mice treated with anti-Gr1 antibody. Dot plots were both gated on live CD11b+ cells. Dot plots shown were representative of a total of 4 mice in each group from 2 experiments. (B) Schematic treatment plan and percent graft survival with anti-Gr1 antibody treatment. ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients further received either anti-Gr1 antibody or isotype control antibody (first dose: 200 µg/mouse; subsequent doses: 100 µg/mouse; IP) on the indicated days (N = 8, data were compiled from 3 independent experiments). *P < .05 (log-rank test).

We next investigated the effects of MCMV infection on the individual MDSC subpopulations in ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients.

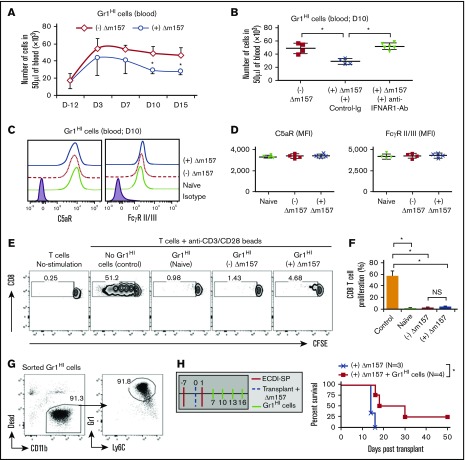

Acute MCMV infection impairs generation of immunosuppressive Gr1HI-MDSCs

We first determined the effect of acute Δm157 infection on Gr1HI-MDSCs in ECDI-SP–treated recipients. As shown in Figure 4A, infusion of donor ECDI-SPs promoted a significant increase of circulating Gr1HI-MDSCs compared with prior to treatment (day −12). This increase was initially observed on day 3 posttransplantation and persisted during subsequent time points (Figure 4A). Interestingly, acute Δm157 infection on day 0 in the same hosts led to a subsequent gradual but sustained decrease of circulating Gr1HI-MDSCs compared with uninfected hosts (Figure 4A). A similar pattern of reduction of Gr1HI-MDSCs in the spleen by Δm157 infection was also observed (data not shown). To determine whether MCMV-induced IFN-α played a role in the observed decline of Gr1HI-MDSCs, we treated Δm157-infected recipients with anti-IFNAR1-Ab as in Figure 2B. As shown in Figure 4B (scatter graph) and supplemental Figure 2 (dot plots), the decline of circulatory Gr1HI-MDSCs by Δm157 infection was indeed completely rescued by anti-IFNAR1-Ab.

Figure 4.

Acute MCMV infection impairs generation of Gr1HI-MDSCs. (A) Kinetics of circulating CD11b+Gr1HI MDSCs in ECDI-SP–treated, either uninfected or Δm157-infected (on day 0), transplant recipients. Total live CD11b+Gr1HI cells were enumerated by FACS in 50 µL of blood drawn on the indicated days. (B) Quantitative analysis of total CD11b+Gr1HI cells in 50 µL of blood collected on day 10 posttransplantation from recipients of the indicated groups. Data shown in panels A and B were from 2 to 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 to 6 mice in each group. *P < .05. (C) Representative histograms of expression of C5aR and FcγRII/III on circulating Gr1HI-MDSCs on day 10 posttransplantation from naïve or transplant recipients with or without day 0 Δm157 infection. (D) Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of C5aR and FcγRII/III of groups shown in panel C. Data presented in panels C and D were obtained from 2 independent experiments with a total of 4 mice in each group. (E) In vitro suppression assay using Gr1HI-MDSCs sorted from the spleen of the indicated groups 10 days posttransplantation. Sorted Gr1HI-MDSCs were cocultured with CFSE-labeled syngeneic CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads (at a ratio of 1:1:1). Proliferation of CD8 T cells was measured by CFSE dilution by FACS. (F) Quantification of CD8 T-cell proliferation in the presence of Gr1HI-MDSCs sorted from the indicated groups shown in panel E. Data shown in panels E and F were obtained from 2 independent experiments with a total of 4 mice in each group. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05. (G) Representative FACS plot depicting the purity of sorted Gr1HI cells pooled from the BM and the spleen of naïve B6 mice used for adoptive transfers. (H) Schematic treatment plan and percent graft survival with adoptive transfer of sorted Gr1HI cells. Two cohorts of ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients were infected with Δm157 on day 0. The first cohort additionally received ∼30 × 106 sorted Gr1HI cells on the indicated days, while the other cohort did not receive any cells (N = 3-4, compiled from 2 independent experiments). *P < .05 (log-rank test).

We next determined if Gr1HI-MDSCs were also phenotypically and/or functionally altered by Δm157 infection. Expression levels of complement receptors C5aR and FcγRII/III (CD32/CD16) on Gr1HI-MDSCs have been associated with their maturation state.34,35 As shown in Figure 4C-D, Δm157 infection did not alter the expression levels of these markers on the Gr1HI-MDSCs. We next examined the suppressive potential of Gr1HI-MDSCs retrieved form Δm157-infected recipients. Ten days posttransplantation, Gr1HI-MDSCs sorted from the spleens of uninfected or Δm157-infected transplant recipients treated with donor ECDI-SPs were cocultured with syngeneic CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. As shown in Figure 4E, in the absence of Gr1HI-MDSCs, CD8 T cells proliferated rigorously upon anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. Addition of Gr1HI-MDSCs at a 1:1 ratio (MDSC:CD8), either from uninfected or Δm157-infected hosts, equally suppressed CD8 T-cell proliferation (Figure 4E-F), similar to their counterpart from naïve untransplanted mice. As a control for nutrient deprivation, addition of an identical number of non-MDSCs failed to suppress T-cell proliferation (data not shown). These data are consistent with published literature demonstrating a predominant effect of CD11b+Gr1+ MDSCs on CD8 T cells.36 A dose titration of Gr1HI-MDSCs in the suppression assay revealed a similar dose response of Gr1HI-MDSCs whether they were from naïve, uninfected, or Δm157-infected ECDI-SP–treated B6 mice (supplemental Figure 3), indicating that MCMV infection did not alter their suppressive capacity. Collectively, these data reveal that MCMV infection impairs generation of the highly immunosuppressive Gr1HI-MDSCs, likely via stimulating type 1 IFN production, but does not alter their phenotype or function.

We next tested whether adoptive transfer of Gr1HI-MDSCs in Δm157-infected recipients could rescue the tolerance induced by donor ECDI-SPs. To do so, we sorted B6 Gr1HI-MDSCs using biotin-labeled anti-Gr1 antibody (Figure 4G); 30 × 106 sorted Gr1HI-MDSCs were adoptively transferred to Δm157-infected recipients on the indicated days (Figure 4H). This resulted in a significant prolongation of graft survival in Δm157-infected recipients (Figure 4H). These data suggest that impairment of tolerance by acute MCMV infection can in part be rescued by adoptive transfers of Gr1HI-MDSCs.

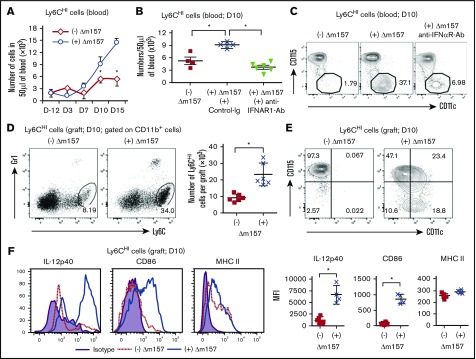

Acute MCMV infection promotes differentiation of inflammatory Ly6CHI monocytes

We next examined the effect of acute Δm157 infection on Ly6CHI-MDSCs. As shown in Figure 5A, in comparison with uninfected recipients, acutely infected recipients exhibited an impressive increase of circulating Ly6CHI cells by day 10 and continued to increase by day 15. This increase of Ly6CHI cells by Δm157 infection was again reversed by recipient anti-IFNAR-Ab treatment (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 2). Phenotypically, we found that the peripheral Ly6CHI cells in Δm157-infected recipients contained a substantial subpopulation (∼40%) that now expressed CD11c while downregulating CD115 (Figure 5C) and F4/80 (supplemental Figure 4). These changes were also largely reversed by anti-IFNAR1-Ab treatment (Figure 5C). Interestingly, we observed a similar increase of Ly6CHI cells in the islet allografts (Figure 5D) of Δm157-infected recipients, which similarly upregulated CD11c while downregulating CD115 (Figure 5E). Furthermore, intragraft Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected recipients expressed a significantly enhanced level of IL-12p40 and CD86 compared with their counterpart from uninfected recipients (Figure 5F). The expression of MHC II was comparable in both groups (Figure 5F). Collectively, these data suggest that Δm157 infection promotes the differentiation of immature Ly6CHI cells to CD11c+CD115− inflammatory monocytes that exhibit an immunostimulatory phenotype.

Figure 5.

Acute MCMV infection promotes differentiation of inflammatory Ly6CHImonocytes. (A) Kinetics of circulating CD11b+Ly6CHI cells in ECDI-SP–treated, either uninfected or Δm157-infected (on day 0), transplant recipients. Total live CD11b+Ly6CHI cells were enumerated by FACS in 50 µL of blood drawn on the indicated days. (B) Quantitative analysis of total CD11b+Ly6CHI cells in 50 µL of blood collected on day 10 posttransplantation from recipients of the indicated groups. (C) Representative FACS plots demonstrating the expression pattern of CD115 and CD11c on circulating Ly6CHI cells from the indicated groups on day 10 posttransplantation. Data shown in panels A-C were from 2 to 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 to 6 mice in each group. *P < .05. (D) Representative FACS plot demonstrating graft-infiltrating Ly6CHI cells (gated on total graft-infiltrating live CD11b+ cells; day 10 posttransplant). Scatter graph showing quantitative analysis of the number of graft-infiltrating Ly6CHI cells (N = 6 in each group). (E) Representative FACS plots demonstrating phenotypic expression of CD115 and CD11c on graft-infiltrating Ly6CHI cells shown in panel D. (F) Representative FACS plots demonstrating expression of intracellular IL-12p40, surface CD86, and MHC II from graft-infiltrating Ly6CHI cells shown in panel D. Scatter graphs showing quantitative analysis of MFIs of the indicated markers. Data shown in panels D-F were obtained from 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 to 6 mice in each group. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05.

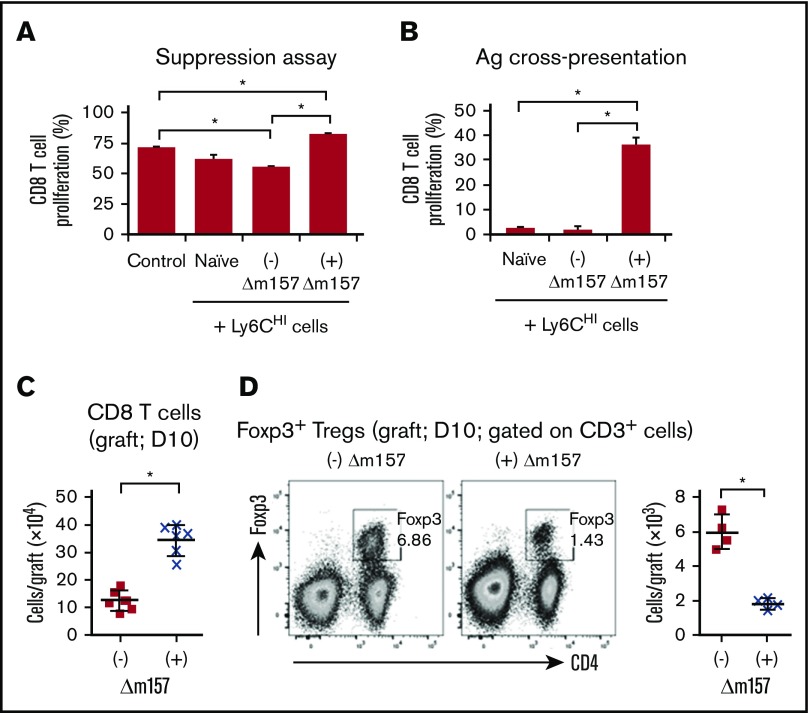

Inflammatory Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected recipients promote priming of CD8 T cells

Next, we evaluated the functional characteristics of Ly6CHI cells in transplant recipients acutely infected with Δm157. To do so, we sorted splenic Ly6CHI cells 10 days posttransplant from either uninfected or Δm157-infected transplant recipients treated with donor ECDI-SPs. We used splenic Ly6CHI cells because they shared a similar phenotype as graft-infiltrating Ly6CHI cells (supplemental Figure 5), and a sufficient number could be obtained for in vitro experiments. Sorted splenic Ly6CHI cells were cocultured with syngeneic CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. As shown in Figure 6A, splenic Ly6CHI cells from uninfected ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients exerted a measurable suppression on CD8 T-cell proliferation. In contrast, splenic Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients completely failed to suppress CD8 proliferation and were in fact further stimulatory to their proliferation (Figure 6A). Next, we examined the ability of the Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected recipients to cross-present alloantigens to stimulate donor-specific T-cell proliferation. To do so, splenic Ly6CHI cells were obtained from Δm157-infected transplant recipients, pulsed with donor splenocyte lysate, and cocultured with syngeneic CD8 T cells at a ratio of 5:1 (Ly6CHI:CD8). Splenic Ly6CHI cells from naïve or uninfected transplanted recipients served as controls. As shown in Figure 6B, in contrast to Ly6CHI cells from naïve or uninfected recipients, Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected recipients readily cross-presented alloantigens to CD8 T cells and stimulated a significant alloantigen-driven proliferation of these cells. Consistent with these data, we observed a marked increase of graft-infiltrating CD8 T cells in ∆m157-infected recipients compared with uninfected recipients (Figure 6C). We further observed that the total number of intragraft CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) was markedly reduced in Δm157-infected recipients (Figure 6D), again suggesting that the Ly6CHI cells from infected recipients may no longer be MDSCs, as functional Ly6CHI-MDSCs have been shown to promote Treg expansion.37 Collectively, these data demonstrate that Ly6CHI cells from Δm157-infected recipients lose MDSC-like immunosuppressive characteristics and instead acquire an immunostimulatory phenotype and gain the ability to prime alloreactive CD8 T cells.

Figure 6.

Functional assessment of Ly6CHIcells and intragraft CD8 T cells and CD4+Foxp3+Tregs. (A) In vitro suppression assay using sorted splenic Ly6CHI cells from the indicated groups 10 days posttransplantation. Control: no Ly6CHI cells were added. Sorted splenic Ly6CHI cells were cocultured with CFSE-labeled syngeneic CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads (at a ratio of 1:1:1). Proliferation of CD8 T cells was quantified by CFSE dilution. Data shown were averaged from a total of 4 mice in each group from 2 independent experiments. (B) Alloantigen cross-presentation by Ly6CHI cells to CD8 T cells. Sorted splenic Ly6CHI cells from the indicated groups were cocultured with CFSE-labeled naïve B6 CD8 T cells at a ratio of 5:1 (Ly6CHI:CD8) in the presence of BALB/c splenocyte lysates (50 µg/mL). CD8 T-cell proliferation was measured by CFSE dilution on day 4 of cocultures. Data shown in panels A and B were averaged from a total of 4 mice in each group from 2 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05. (C) Quantitative analysis of graft-infiltrating CD3+CD8+ T cells (day 10 posttransplant) from the indicated groups. (D) Representative FACS plots demonstrating graft-infiltrating CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs (day 10 posttransplant; gated on CD3+ cells) from the indicated groups. Scatter graph showing quantitation of Treg numbers. Data shown in panels C and D were from 2 to 3 independent experiments with a total of 4 to 6 grafts in each group. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05.

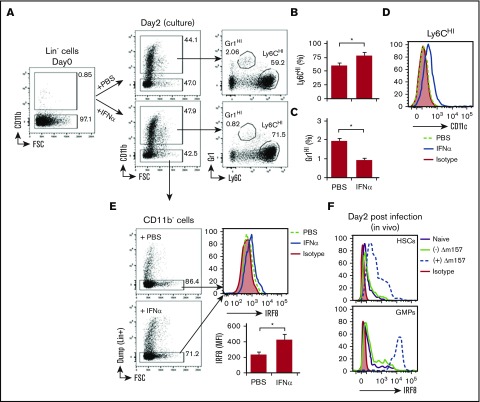

IFN-α regulates the differentiation of Gr1HI and Ly6CHI cells

Gr1HI and Ly6CHI cells arise from BM lineage negative (Lin−) progenitor cells. Therefore, we next examined whether IFN-α induced by MCMV infection could directly alter Gr1HI and Ly6CHI cell differentiation from BM progenitors. Sorted BM Lin− cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IFN-α for 2 days and examined for their differentiation to CD11b+Gr1HI and CD11b+Ly6CHI cells. As shown in Figure 7A, a substantial fraction of Lin− cells spontaneously differentiated to CD11b+ cells regardless of the presence or absence of IFN-α. These differentiated CD11b+ cells were identified largely as Ly6CHI cells but also a small fraction of Gr1HI cells (Figure 7A). Interestingly, IFN-α significantly augmented the generation of Ly6CHI cells (Figure 7B), whereas it suppressed the generation of Gr1HI cells (Figure 7C). Consistent with our in vivo observations in Figure 5C, the in vitro differentiated Ly6CHI cells in the presence of IFN-α also expressed a heightened level of CD11c (Figure 7D). It has been recently shown that enhanced expression of IRF8 in Lin− progenitors promotes their differentiation to inflammatory Ly6CHI monocytes but inhibits their differentiation to Gr1HI cells.38-40 Consistent with this notion, we found that IRF8 expression by Lin− cells in our culture was significantly increased by IFN-α (Figure 7E), further supporting the observed effects of IFN-α on Ly6CHI and Gr1HI cell differentiation from Lin− progenitors (Figure 7A-C). Interestingly, following Δm157 infection in donor ECDI-SP–treated mice, we also observed a significant increase in IRF8 expression in BM Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ hematopoietic stem cells as well as in Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−FcγRII/III+ granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) (Figure 7F; supplemental Figure 6) in these mice. An increased expression of IRF8 in GMPs in Δm157-infected mice coupled with a reduction of Gr1HI cells in these mice is consistent with a recent report demonstrating the effect of IRF8 in the differential generation of granulocytes and/or monocytes.39 Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that MCMV-induced IFN-α inhibits the generation of immunosuppressive Gr1HI cells from BM Lin− progenitors while promoting the differentiation of immunostimulatory Ly6CHI cells.

Figure 7.

IFN-α regulates the differentiation of CD11b+Gr1HIand CD11b+Ly6CHIcells from lineage negative (Lin−) BM progenitor cells. (A) Representative FACS plots showing preculture Lin−CD11b− cells and their differentiation to CD11b+Gr1HI or CD11b+Ly6CHI cells following a 2-day culture in the presence of vehicle (PBS) or IFN-α (100 U/mL). (B) Bar graphs showing quantitation of Ly6CHI cells (B) or Gr1HI cells (C) following 2 days of culture. (D) Representative histogram showing CD11c expression by Ly6CHI cells differentiated from Lin− cells in the presence or absence of IFN-α. (E) Representative FACS plots showing the gating of the remaining CD11b−Lin− cells following the 2-day culture to be examined for intracellular IRF8 expression and representative histogram showing IRF8 expression by CD11b−Lin− cells in the presence or absence of IFN-α. Bar graph showing the MFIs of IRF8 normalized over isotype control. Data shown in panels A-E were obtained from 2 independent culture experiments performed in triplicates and presented as mean ± SD of 6 replicates. *P < .05. (F) Representative histograms depicting the expression of IRF8 in BM hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs: Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+) and GMPs (Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−FcγRII/III+) from naïve mice (solid purple line), uninfected ECDI-SP–treated mice (solid green line), or Δm157-infected ECDI-SP–treated mice (dashed blue line) 2 days post–Δm157 infection. Data shown in panel F were obtained from 2 independent experiments with a total of 4 mice in each group.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the impact of acute MCMV infection on donor-specific transplant tolerance induced by donor ECDI-SPs.14,15 We show that acute MCMV infection impairs the induction of donor-specific tolerance by this approach, resulting in loss of graft function in a significant number of recipients (Figure 1). Modeling various pathogens (including viral, bacterial, and parasitic) has suggested that they may precipitate graft rejection by activating cross-reactive or alloreactive T cells.41-44 However, the precise mechanisms underlying such T-cell activation remain unclear. To our best knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating interference with MDSC differentiation by virus-induced IFN-α as an underlying mechanism for alloreactive T-cell activation and consequent tolerance abrogation.

Direct CMV cytopathic effects on transplanted allografts have been shown to cause graft destruction.45 However, our data show that direct MCMV infection of transplanted islets does not result in islet destruction or loss of islet graft function. This finding suggests that MCMV-mediated abrogation of transplant tolerance is not because of its direct cytopathic effects on islets, but rather is because of its interference with tolerogenic mechanisms of donor ECDI-SPs. Our observations from acute MCMV infection during tolerance induction now provide the basis for future studies of 2 additional highly relevant questions surrounding the interplay between MCMV infection and transplant tolerance: (1) whether maintenance of tolerance is impaired by MCMV infection and (2) whether chronic MCMV infection impairs tolerance induction and/or maintenance.

In the present study, we show that following MCMV infection, IFNAR1 signaling plays a critical role in impairing differentiation and/or function of both granulocytic and monocytic MDSCs critical for tolerance induction. A near complete restoration of the number and phenotype of both cell types by IFNAR1 blockade in MCMV-infected hosts and subsequent restoration of transplant tolerance further confirm this notion. Consistent with our previous reports,18 we find that the highly immunosuppressive Gr1HI cells are markedly increased following ECDI-SPs. However, with concurrent MCMV infection, their number is significantly reduced, although their phenotype and suppressive function remain unchanged. It has been recently reported that enhanced expression of IRF8 suppresses granulocyte differentiation via inhibiting the activity of C/EBPα.38 Interestingly, we observed a higher level of IRF8 expressed by Lin− BM progenitors upon IFN-α stimulation in vitro or by MCMV infection in vivo (Figure 7E-F), and this correlated with a diminished number of Gr1HI cells under these conditions. In experimental models and in the clinic, impairment of granulocyte and neutrophil generation by CMV infection has been well documented.46,47 Our data now provide a possible mechanistic link between these observations.

Ly6CHI monocytic cells have been shown to mediate host antimicrobial defense in many infections.48 In transplantation, Ly6CHI monocytic cells have been shown to promote both graft tolerance37,49 and graft rejection.50,51 Our data show that Ly6CHI cells from uninfected ECDI-SP–treated transplant recipients exhibit MDSC-like characteristics. Following acute MCMV infection, Ly6CHI monocytes significantly expand in periphery and in allografts. However, the expanded Ly6CHI cells no longer exhibit the same MDSC-like phenotype. In contrast, these cells acquire an immunostimulatory phenotype and are now capable of cross-presenting alloantigens and stimulating alloreactive CD8 T cells. These data are consistent with recent reports demonstrating a role of Ly6CHI monocytes in allograft rejection.50,51 Interestingly, we observe that Ly6CHI monocytes from MCMV-infected recipients acquire CD11c expression while losing F4/80 and CD115 expression, suggesting their differentiation to professional antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Such a differentiation of Ly6CHI monocytic cells into dendritic cells has been previously associated with inflammation,52 increased immunogenicity,53 and graft rejection,50 whereas persistent F4/80 and CD115 expression by Ly6CHI monocytes has been associated with their immunosuppressive potential.54 Therefore, downregulation of F4/80 and CD115 coupled with upregulation of CD11c by Ly6CHI monocytes following MCMV infection explains their loss of MDSC-like immunosuppressive function while developing the ability to activate alloreactive CD8 T cells. Elevated expression of CD115, also known as the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), on tumor infiltrating myeloid cells has been reported to promote their immunosuppressive potential and prolong tumor survival. Recently, blocking CD115 and its downstream signaling has become a novel therapeutic approach in cancer therapies.55 It would be highly intriguing to investigate whether agonizing CD115 to promote its downstream signaling would preserve transplant tolerance in settings of CMV infection.

Another interesting observation in our study is the significant reduction of intragraft Foxp3+ Tregs in MCMV-infected recipients. It has been previously reported that CD11b+CD115+ monocytic MDSCs promote antigen-specific Tregs in tumors and cardiac transplantation models.49,54,56 Corroborating these studies, we found that in uninfected recipients intragraft Ly6CHI monocytic cells with a prominent CD115 expression correlated with an elevated number of Tregs in these grafts. In contrast, loss of CD115 on a significant fraction of the intragraft Ly6CHI cells in MCMV-infected recipients correlated with a significant reduction of Tregs in these grafts. Collectively, these data suggest that phenotypic and functional alterations of Ly6CHI monocytes in MCMV-infected recipients may indeed alter both intragraft effector (Teff) and Tregs, resulting in an unfavorable ratio of these 2 populations leading to eventual graft demise.

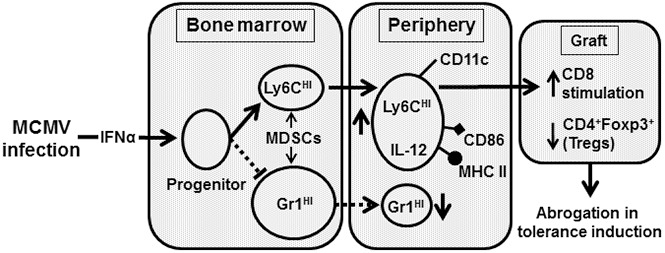

In summary, we demonstrate that acute MCMV infection induces type 1 IFN production, which in turn alters the differentiation of tolerance-promoting MDSCs. This alteration results in an increase of intragraft alloreactive CD8 T cells and a concurrent decline of intragraft Tregs, correlated with ultimate graft rejection in infected recipients. Mechanisms of tolerance impairment by CMV infection demonstrated by this study, coupled with additional evidence demonstrating that CMV infection impairs transplant tolerance in models other than ours,13 now provide timely information needed for investigating effective therapies for preserving transplant tolerance in settings of CMV infection.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (P01 AI112522) (A.D. and X.L.), and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health (R01 EB009910) (X.Z. and X.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.D. and X.L. designed experiments; A.D., L.Z., and X.Z. performed experiments; A.D., L.Z., and X.L. analyzed data; A.D. and X.L. wrote the manuscript; and X.L. edited and finalized the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Xunrong Luo, Center for Kidney Research and Therapeutics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 303 E Chicago Ave, Searle Building 10-515, Chicago, IL 60611; e-mail: xunrongluo@northwestern.edu.

References

- 1.Forbes BA. Acquisition of cytomegalovirus infection: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2(2):204-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman JA, Emery V, Freeman R, et al. Cytomegalovirus in transplantation—challenging the status quo. Clin Transplant. 2007;21(2):149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eid AJ, Razonable RR. New developments in the management of cytomegalovirus infection after solid organ transplantation. Drugs. 2010;70(8):965-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern M, Hirsch H, Cusini A, et al. ; Members of Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Cytomegalovirus serology and replication remain associated with solid organ graft rejection and graft loss in the era of prophylactic treatment. Transplantation. 2014;98(9):1013-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azevedo LS, Pierrotti LC, Abdala E, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. Clinics (São Paulo). 2015;70(7):515-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams MA, Onami TM, Adams AB, et al. Cutting edge: persistent viral infection prevents tolerance induction and escapes immune control following CD28/CD40 blockade-based regimen. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5387-5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spitzer TR, Delmonico F, Tolkoff-Rubin N, et al. Combined histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-matched donor bone marrow and renal transplantation for multiple myeloma with end stage renal disease: the induction of allograft tolerance through mixed lymphohematopoietic chimerism. Transplantation. 1999;68(4):480-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millan MT, Shizuru JA, Hoffmann P, et al. Mixed chimerism and immunosuppressive drug withdrawal after HLA-mismatched kidney and hematopoietic progenitor transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(9):1386-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fudaba Y, Spitzer TR, Shaffer J, et al. Myeloma responses and tolerance following combined kidney and nonmyeloablative marrow transplantation: in vivo and in vitro analyses. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(9):2121-2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):353-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LoCascio SA, Morokata T, Chittenden M, et al. Mixed chimerism, lymphocyte recovery, and evidence for early donor-specific unresponsiveness in patients receiving combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation to induce tolerance. Transplantation. 2010;90(12):1607-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal JR, Elliott MJ, Yolcu ES, et al. Immune reconstitution/immunocompetence in recipients of kidney plus hematopoietic stem/facilitating cell transplants. Transplantation. 2015;99(2):288-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duran-Struuck R, Sondermeijer HP, Bühler L, et al. Effect of ex vivo-expanded recipient regulatory T cells on hematopoietic chimerism and kidney allograft tolerance across MHC barriers in cynomolgus macaques. Transplantation. 2017;101(2):274-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo X, Pothoven KL, McCarthy D, et al. ECDI-fixed allogeneic splenocytes induce donor-specific tolerance for long-term survival of islet transplants via two distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14527-14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kheradmand T, Wang S, Bryant J, et al. Ethylenecarbodiimide-fixed donor splenocyte infusions differentially target direct and indirect pathways of allorecognition for induction of transplant tolerance. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):804-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G, Kheradmand T, Bryant J, et al. Intragraft CD11b(+) IDO(+) cells mediate cardiac allograft tolerance by ECDI-fixed donor splenocyte infusions. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(11):2920-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Tasch J, Kheradmand T, et al. Transient B-cell depletion combined with apoptotic donor splenocytes induces xeno-specific T- and B-cell tolerance to islet xenografts. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3143-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant J, Lerret NM, Wang JJ, et al. Preemptive donor apoptotic cell infusions induce IFN-γ-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells for cardiac allograft protection. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):6092-6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Zhang X, Zhang L, et al. Preemptive tolerogenic delivery of donor antigens for permanent allogeneic islet graft protection. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(6):1155-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HK, Wang S, Dangi A, et al. Differential role of B cells and IL-17 versus IFN-γ during early and late rejection of pig islet xenografts in mice. Transplantation. 2017;101(8):1801-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mevorach D, Zuckerman T, Reiner I, et al. Single infusion of donor mononuclear early apoptotic cells as prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease in myeloablative HLA-matched allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a phase I/IIa clinical trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(1):58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutterotti A, Yousef S, Sputtek A, et al. Antigen-specific tolerance by autologous myelin peptide-coupled cells: a phase 1 trial in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(188):188ra75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dilek N, van Rompaey N, Le Moine A, Vanhove B. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(6):765-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brune W, Hengel H, Koszinowski UH. A mouse model for cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;43(19.7):19.7.1-19.7.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zurbach KA, Moghbeli T, Snyder CM. Resolving the titer of murine cytomegalovirus by plaque assay using the M2-10B4 cell line and a low viscosity overlay. Virol J. 2014;11:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XF, Yan S, Abecassis M, Hummel M. Biphasic recruitment of transcriptional repressors to the murine cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter during the course of infection in vivo. J Virol. 2010;84(7):3631-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt V, Forbes CA, Tonkin JN, et al. Murine cytomegalovirus m157 mutation and variation leads to immune evasion of natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(23):13483-13488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalod M, Hamilton T, Salomon R, et al. Dendritic cell responses to early murine cytomegalovirus infection: subset functional specialization and differential regulation by interferon alpha/beta [published correction appears in J Exp Med 2003;197(9):1229]. J Exp Med. 2003;197(7):885-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider K, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, et al. Lymphotoxin-mediated crosstalk between B cells and splenic stroma promotes the initial type I interferon response to cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(2):67-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(2):125-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexandre YO, Cocita CD, Ghilas S, Dalod M. Deciphering the role of DC subsets in MCMV infection to better understand immune protection against viral infections. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood KJ, Bushell A, Hester J. Regulatory immune cells in transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(6):417-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo RF, Ward PA. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23(1):821-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogarth PM. Fc receptors are major mediators of antibody based inflammation in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14(6):798-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delano MJ, Scumpia PO, Weinstein JS, et al. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med. 2007;204(6):1463-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochando J, Conde P, Bronte V. Monocyte-derived suppressor cells in transplantation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2015;2(2):176-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurotaki D, Yamamoto M, Nishiyama A, et al. IRF8 inhibits C/EBPα activity to restrain mononuclear phagocyte progenitors from differentiating into neutrophils. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yáñez A, Ng MY, Hassanzadeh-Kiabi N, Goodridge HS. IRF8 acts in lineage-committed rather than oligopotent progenitors to control neutrophil vs monocyte production. Blood. 2015;125(9):1452-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sichien D, Scott CL, Martens L, et al. IRF8 transcription factor controls survival and function of terminally differentiated conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, respectively. Immunity. 2016;45(3):626-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pantenburg B, Heinzel F, Das L, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. T cells primed by Leishmania major infection cross-react with alloantigens and alter the course of allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2002;169(7):3686-3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang T, Chen L, Ahmed E, et al. Prevention of allograft tolerance by bacterial infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):5991-5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, et al. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J Virol. 2000;74(5):2210-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG, et al. TLR agonists abrogate costimulation blockade-induced prolongation of skin allografts. J Immunol. 2006;176(3):1561-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koskinen PK, Kallio EA, Tikkanen JM, Sihvola RK, Häyry PJ, Lemström KB. Cytomegalovirus infection and cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Transpl Infect Dis. 1999;1(2):115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell BM, Leung A, Stevens JG. Murine cytomegalovirus DNA in peripheral blood of latently infected mice is detectable only in monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Virology. 1996;223(1):198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirayama Y, Sakamaki S, Tsuji Y, et al. Recovery of neutrophil count by ganciclovir in patients with chronic idiopathic neutropenia associated with cytomegalovirus infection in bone marrow stromal cells. Int J Hematol. 2004;79(4):337-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):762-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia MR, Ledgerwood L, Yang Y, et al. Monocytic suppressive cells mediate cardiovascular transplantation tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2486-2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberbarnscheidt MH, Zeng Q, Li Q, et al. Non-self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(8):3579-3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakkis FG, Li XC. Innate allorecognition by monocytic cells and its role in graft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(2):289-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keizer GD, Te Velde AA, Schwarting R, Figdor CG, De Vries JE. Role of p150,95 in adhesion, migration, chemotaxis and phagocytosis of human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17(9):1317-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garnotel R, Rittié L, Poitevin S, et al. Human blood monocytes interact with type I collagen through alpha x beta 2 integrin (CD11c-CD18, gp150-95). J Immunol. 2000;164(11):5928-5934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):1123-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cannarile MA, Weisser M, Jacob W, Jegg AM, Ries CH, Rüttinger D. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan PY, Ma G, Weber KJ, et al. Immune stimulatory receptor CD40 is required for T-cell suppression and T regulatory cell activation mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(1):99-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.