Abstract

Ligation of PD-1 in the tumor microenvironment is known to inhibit effective adaptive anti-tumor immunity. Blockade of PD-1 in humans has resulted in impressive, durable regression responses in select tumor types. However, durable responses have been elusive in ovarian cancer patients. PD-1 was recently shown to be expressed on and thereby impair the functions of tumor-infiltrating murine and human myeloid dendritic cells (TIDC) in ovarian cancer. In the present work, we characterize the regulation of PD-1 expression and the effects of PD-1 blockade on TIDC. Treatment of TIDC and bone marrow-derived DC with IL-10 led to increased PD-1 expression. Both groups of DC also responded to PD-1 blockade by increasing production of IL-10. Similarly, treatment of ovarian tumor-bearing mice with PD-1 blocking antibody resulted in an increase in IL-10 levels in both serum and ascites. While PD-1 blockade or IL-10 neutralization as monotherapies were inefficient, combination of these two led to improved survival and delayed tumor growth; this was accompanied by augmented anti-tumor T and B cell responses and decreased infiltration of immunosuppressive MDSC. Taken together, our findings implicate compensatory release of IL-10 as one of the adaptive resistance mechanisms that undermine the efficacy of anti-PD-1 (or anti-PD-L1) monotherapies and prompts further studies aimed at identifying such resistance mechanisms.

Keywords: tumor microenvironment, checkpoint

INTRODUCTION

Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) and Program Cell Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) constitute a major immune regulatory axis that blocks anti-tumor effector responses in the tumor microenvironment. PD-1 is an inhibitory receptor expressed on several adaptive and innate immune cells including T cells, B-cells, monocytes, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) (1–4). Known PD-1 ligands include PD-L1 (B7-H1 or CD274) and PD-L2 (B7-DC or CD273) (1). PD-L1 is constitutively expressed on many cells types like DCs and macrophages. PD-L1 is inducible on T cells, B-cells, tumor cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. Similarly, PD-L2 is primarily induced, depending on the cytokine milieu, on DCs, B-cells, macrophages, and monocytes (1, 5–7). The ligation of PD-1 by its ligands, during T-lymphocyte activation, has been shown to result in the tyrosine phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic tail leading to recruitment of Src homology domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2). Activated SHP-2 subsequently dephosphorylates T cell receptor (TCR) proximal signaling complexes such as ZAP70/CD3ζ, PI3K and inhibits Akt phosphorylation culminating in the inhibition of T cell proliferation, cytotoxic functions and cytokine release, and promotion of apoptosis (8, 9).

PD-1 expression on lymphocytes is dynamic and is upregulated following TCR or B cell receptor (BCR) ligation. Studies also have shown that T cells are programmed epigenetically upon persistent antigenic stimulation for rapid PD-1 expression upon restimulation (10, 11). One crucial observation that is made frequently is that the expression of PD-1 on T cells infiltrating in tumors is very high compared to their peripheral or normal tissue counterparts (12, 13). This high expression of PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating T cells not only identifies them as tumor antigen-specific but also correlates with blunted responsiveness to further stimulation (13, 14). Furthermore, infiltration by PD-1+ lymphocytes often correlates with distant metastatic relapse and poor prognosis in many tumor types (12, 14, 15).

In many malignant tissues it has been observed that up to 40% of the infiltrating immune cells are TIDCs and disease progression correlates with the phenotypic switch of TIDCs from immune stimulatory to immune suppressive (4, 16). We have shown in a murine model of ovarian carcinoma that TIDCs also become increasingly PD-1+ as disease progresses rendering them ineffective as immune stimulators by inhibiting the cytokine release, co-stimulatory molecules expression, and antigen presentation capacity (4). It is now clear from many recent studies that the TME is adept at inducing PD-1 expression on the infiltrating immune effector cells, rendering them ineffective. The identification of TME-associated factors and mechanisms responsible for the unique regulation of PD-1 expression on infiltrating immune cells remains underdeveloped.

As we and others have shown, ovarian cancer creates a pronounced immune suppressive TME (17) and of many factors, the cytokine IL-10 has been correlated with volume of ascites, poor survival and relapse (18–20). In the ID8 murine model of ovarian cancer, we have seen that IL-10 is present at high levels in both the blood serum and ascites. Additionally, the ascites and tumor-infiltrating immune cells, including the TIDCs, express very high levels of PD-1 compared to their peripheral counterparts (4). Given the immune regulatory role of IL-10 and its correlation with disease severity and poor prognosis in ovarian cancer, we sought to explore if IL-10 induces PD-1 expression on the TIDCs. Our results show that IL-10 treatment of TIDCs results in increased expression of PD-1 in a STAT3-dependent manner. Antibody-mediated blockade of PD-1 on TIDCs subsequently leads to increased release of IL-10 into the TME of treated mice. Co-blockade of both PD-1 and IL-10 results in significant enhancement in survival of tumor bearing mice, reduced tumor burden, and augmented adaptive anti-tumor immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Four- to 12-wk-old female C57BL/6J (B/6J) mice, obtained from an in-house breeding program or from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), were used for experimentation. Animal care and use was in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Mayo Clinic.

Cell lines

Leukocytes were cultured in modified RPMI 1640 media as previously described (4). ID8 tumor cells, obtained from Dr. K. Roby, University of Kansas in 2005, were derived from immortalized ovarian epithelial cells generated by repeated passage in culture and were grown in complete DMEM media (4). They were last authenticated as mouse origin by IDEXX BioResearch in 2014. ID8 cells used in the described experiments were used within 12 passages upon receipt.

Tumor implantation

ID8 tumor cells (5 × 106 cells) were injected i.p. at a volume of 500 μl in PBS. Tumor and ascites were harvested from the mice when moribund, usually 50–100 days following challenge. For comparison of tumor burden, the weight of omentum was measured from tumor bearing mice as a surrogate. This was done to reduce variability associated with harvesting diffuse nodules scattered throughout the peritoneal cavity. We found in preliminary studies that the weight of the tumor bearing greater omentum is linearly proportional to the total tumor burden (R2=0.81, p<0.0001, n=56). In order to more accurately represent tumor burden, the weight of omentum of age-matched healthy mice were subtracted from the omentum of the tumor bearing mice.

In vivo PD-1 and IL-10 blockade

Mice were inoculated with ID8 cells and on day 25 received either 200 μg hamster IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or 200 μg G4 clone PD-1–blocking monoclonal antibody i.p. as described (21, 22). Mice were treated until moribund up to 11 treatments (8 - 11 times up to 7 weeks). IL-10 neutralizing antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and IL-10R antagonist antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) were injected i.p alternating between the two antibodies at a concentration of 100 μg and 200 μg per mouse, respectively. The same amount of isotype matched antibodies (Rat IgG1κ or Rat IgG1χ) from the respective suppliers was injected in the control groups. Tumor and ascites were harvested as necessary when mice were moribund.

Leukocyte isolation and culture

Leukocytes from ascites of tumor-bearing mice were isolated by discontinuous Ficoll gradient as described previously (23). Tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) were harvested by mincing the tumor through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer and separation with a discontinuous Ficoll gradient. From single-cell suspensions, DCs were magnetically isolated based on the cells of interest using CD11c microbeads obtained from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Naive mouse leukocytes were obtained from BL/6J mice spleens by grinding the spleen through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer. The splenocytes were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min and resuspended in 4 ml (Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium) ACK buffer to lyse red blood cells. The remaining cells were then washed and resuspended in culture media. Bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were obtained from BL/6J by flushing femurs and tibias with media and centrifuging cells at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes, followed by ACK treatment. Cells were re-suspended with media containing 10 ng/ml mGM-CSF and 1 ng/ml mIL-4 and plated into 6 well plates. Culture media was changed with fresh media containing 10 ng/ml mGM-CSF and 1ng/ml mIL4 at 48 and 96 hours. The cells were matured with 40 ng/mL TNFα on day 5 of cell culture. After 2 additional days, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in fresh media and cytokines (VEGF-A, Genway Biotech, San Diego CA; IL-4, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ); IL-10, Peprotech; IL-12, Peprotech) or control vehicle were added to respective wells.

Flow cytometry

Cell-surface molecule staining and flow cytometry were done essentially as previously described on whole populations and/or enriched populations (21, 22). For flow cytometric analysis, a similar number of events, usually 20,000 – 200,000 were collected for all groups. Antibodies against CD3, CD8, CD11c, F4/80, PD-1, CD45, PD-L1, PD-L2, CD40, CD27, CD69, CD80, and CD86 were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against CD4, CD25 were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Appropriate isotype-matched non-specific antibodies were used as controls.

STAT3 inhibition and siRNA knockdown

For STAT3 inhibition, STAT3 Inhibitor VI (InSolution™ Calbiochem, Billerica, MA) was used at 150 uM. IL-10 was added to the respective wells one hour following the addition of the STAT3 inhibitor. STAT3 siRNAs (siRNA I and siRNA II) and the control siRNA were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, Massachusetts) and were used at a concentration of 150 nM. Mission siRNA transfection reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as transfection agent. SiRNA-mediated reduction in STAT3 protein was confirmed using Western Blot analysis after 48 or 72 hrs. Forty-eight hours after addition of siRNA, cells were either left untreated or treated with IL-10 (10 ng/mL) for an additional 48 hours. Cells were then stained for flow cytometric analysis.

Western Blot

BMDCs in respective experiments were lysed in lysis buffer A (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris Cl (pH7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM NaF, 1% Triton X 100, 5% glycerol, HALT protease/phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific). 10 μgs protein were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting for PD-1 (Novus Biologicals, AF1021), STAT3 (79D7) and p-STAT3 (D3A7) (Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (LI-COR, Lincoln NE). Corresponding anti-goat, anti-mouse, and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to IRDyes were purchased from LI-COR. Signal was detected using LI-COR Odyssey Imaging System.

Reverse-transcription-polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated from purified TIDCs using Qiagen RNeasy plus mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PD-1 specific quantitative PCR was performed using the PD-1 (NM_008798.2) primer/probe set (Mm01285676_m1) purchased from ThermoFisher. GAPDH was used as internal control using the primer/probe set (Mm99999915_g1) from ThermoFischer. IL-10 (NM_010548.2) specific PCR amplification was performed using the following primers: forward primer 5′-ATGCCTGGCTCAGCACTGCT -3′, reverse primer 5′-CATTCATGGCCTTGTAGACACCTTGG-3′. β-actin (NM_007393.5) was used as control. Following primers were used for β-actin specific PCR amplification: Murine forward primer 5′-GTCCCTCACCCTCCCAAAAG-3′, murine reverse primer 5′-GCTGCCTCAACACCTCAAC CC-3′. Bands were resolved by running PCR products on a 1% agarose gel.

Cytokine ELISA

TIDCs or BMDCs were treated with 10 μg/ml anti-PD1 antibody (G4 clone), 10 μg/ml isotype control IgG, or left untreated for 24 or 48 hrs, after which the supernatants were collected for IL-10 and soluble PD-L1 assessments. TIDCs, serum and ascites samples were also collected for IL-10 and PD-L1 assessments. To measure mouse IL-10, a Ready-Set-Go ELISA kit from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) was used according to manufacturer’s protocol. Soluble PD-L1 ELISA was performed on the cell culture supernatants according to the manufacturer’s protocol (My BioSource, San Diego, CA).

FRα antibody ELISA

ELISA plates were coated in bicarbonate coating buffer with recombinant mouse FRα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. Wells that did not receive any serum were used to determine the background. Serial dilutions of purified mouse IgG were used as a standard curve to convert the O.D. reading to a concentration of antigen-specific IgG. After overnight incubation at 4C, the plates were washed with 0.05% Tween in PBS, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, washed again, and then serum samples were added. Plates were then incubated overnight at 4C followed by wash with PBS/Tween. Anti-mouse HRP secondary Ab was then added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature before washing and developing with TMB substrate. OD was read using an ELISA reader after reaction was stopped by reducing the pH of the reactions with acid.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA; http://www.graphpad.com). The Student t test, Mann–Whitney U test, or two-way ANOVA test was performed to determine statistically significant difference. A p value ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

IL-10 increases the expression of PD-1 and its ligand PD-Ll on ovarian TIDCs

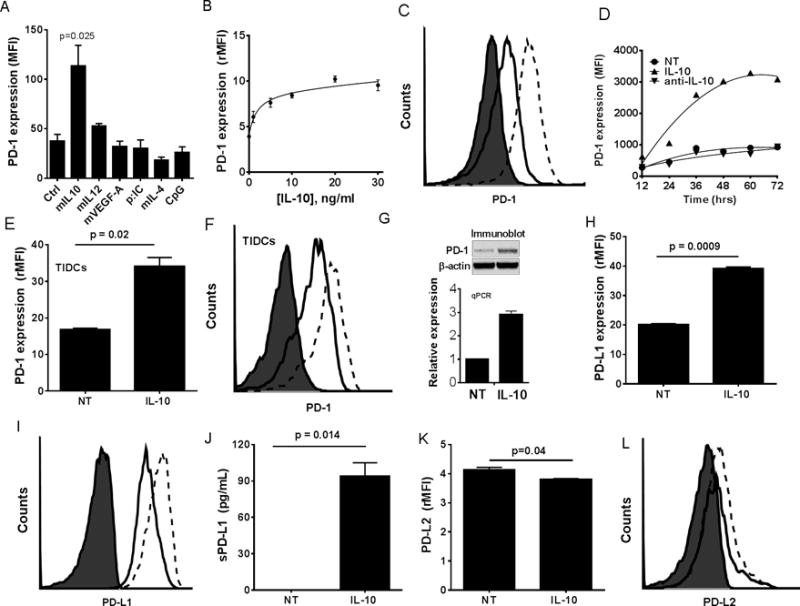

Our recent studies have shown that PD-1, which has been primarily studied in T cells, is also expressed on the TIDCs (4). In the present study, we wanted to determine what factors (e.g. cytokines), commonly found in tumor microenvironment, lead to the increased expression of PD-1 on the TIDCs. Since TIDCs already have upregulated PD-1, and in general are difficult to access, we developed an in vitro model using BMDCs which consistently have a much lower level expression of PD-1 relative to TIDCs (4). TNF-α-activated BMDCs were treated with a variety of well-described immunologic agonists (IL-10, 10 ng/mL; IL-12, 20 ng/ml; VEGF-A, 25 ng/ml; poly: IC, 50 ug/mL; CpG, 50 ug/ml; or IL-4, 5 ng/mL) for 48 hours after maturation, followed by flow cytometric analysis of PD-1 expression. As shown in Fig. 1A, of the agents tested, only IL-10 was able to induce significantly elevated expression of PD-1 on BMDCs. IL-10 dose assessments (Fig. 1B) showed dose dependency with maximal effective concentration of 5.1 ± 1.3 ng/ml (n=18). Fig. 1C shows a flow cytometry histogram of PD-1 expression on BMDCs upon treatment with 10 ng/mL Il-10. Time course experiments showed PD-1 was maximally upregulated at 48 hours following exposure to IL-10 (10 ng/ml) (Fig. 1D). To determine the validity of the BMDC, we also observed the effects of IL-10 on expression of PD-1 on the surface of murine ovarian TIDCs-derived from ascites. As shown in Figs. 1E–F, while TIDCs express high levels of PD-1, treatment with IL-10 for 48 hrs. led to a further increase in PD-1 expression by approximately double. Increased expression of PD-1 induced by IL-10 was due to augmented pdcd1 gene expression which resulted in increased total cellular levels of PD-1 protein (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1. IL-10 increases the expression of PD-1 and its ligand PD-Ll on ovarian DCs.

Panel A shows mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 staining on BMDCs following 48 hrs exposure to cytokines and TLR agonists. Each bar represents mean ± SEM (n=3). Panel B shows line graph of mean ± SEM (n=3) relative MFI (rMFI) values for PD-1 expression on BMDCs treated for 48 hrs with increasing concentrations of IL-10. Panel C shows a representative histogram of PD-1 expression on BMDCs treated with IL-10. Panel D shows a line graph of the MFI values for PD-1 expression on BMDCs treated over a time course with 10 ng/ml IL-10, control vehicle (NT), or anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody. Panel E shows the mean ± SEM (n=3) rMFI values for PD-1 on ID8-derived TIDCs, obtained from ascites, treated or untreated with IL-10 for 48 hrs. Panel F shows a representative histogram of data from Panel E. Panel G shows photograph of representative western blot (top) and PCR (bottom) of PD-1 protein and mRNA levels respectively in BMDCS. Panel H shows the mean ± SEM (n=3) rMFI values of surface bound PD-L1 expression on BMDCs treated as above. Panel I is a representative histogram for Panel H. Panels J shows the mean ± SEM (n=3) levels of soluble PD-L1 (sPD-L1) in supernatants of BMDCs either untreated or treated with IL-10. Panel K shows the mean ± SEM (n=3) rMFI values of surface bound PD-L2 expression on BMDCs treated as above. Panel L is a representative histogram for Panel K. Filled histogram = isotype stain, solid line = untreated (NT) DCs, and dashed lines = IL-10-treated DCs. P values were calculated with a Student’s Paired T test. All data is representative of three individual experiments with similar results.

We previously showed that PD-1 maintains an immune suppressive phenotype of TIDCs and that a primary mediator of T cell suppression is TIDC-expressed PD-L1 (4, 24). Thus, as a readout for immune suppressive potential, we also analyzed PD-L1 expression following IL-10 treatment of BMDCs. As shown in Figs. 2H–I, IL-10 also led to an increased expression of PD-L1 on the surface. We also observed that IL-10 treatment of BMDCs induced the release of soluble PD-L1 (sPD-L1) by these cells (Fig. 1J). In contrast, DCs express only low levels of PD-L2, which was not increased following treatment with IL-10 (Figs. 1K–L). The effects of IL-6 were also examined in comparison with IL-10 since both cytokines have common proximal signaling elements (e.g. JAK-STAT3) (25). IL-6 was able to induce PD-1 expression in BMDCs but was not nearly as effective as IL-10 (Fig. S1A). In fact, the effect of IL-6 was biphasic, peaking at 30 ng/ml and then ineffective at higher concentrations. In contrast, IL-6 appeared to be more efficient at driving PD-1 expression on CD4 T cells during T cells activation, whereas, IL-10 had no effect (Fig. S1B). Similar effects were observed with CD8 T cells, although much less pronounced (Fig. S1C). Thus, IL-10, which is typically at high levels in the ovarian cancer TME, is a key driver of PD-1 expression on TIDCs.

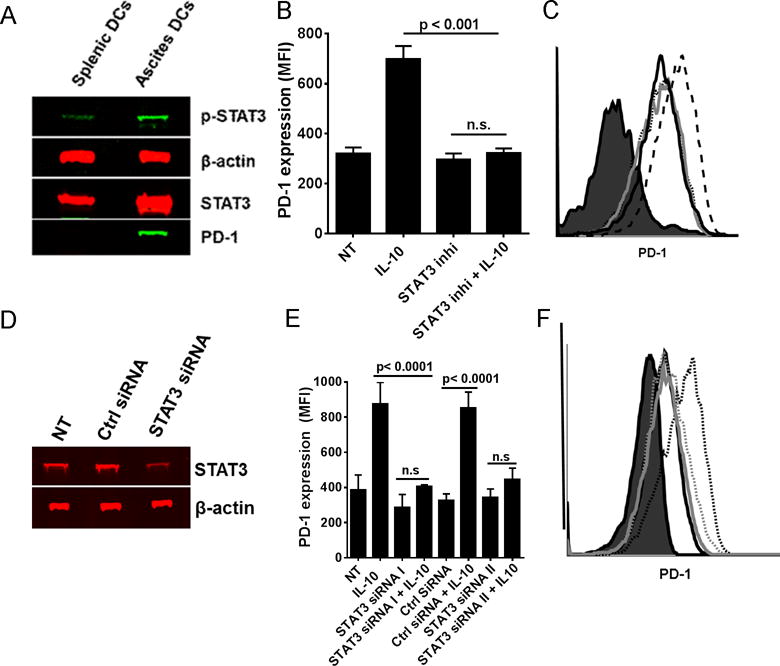

Figure 2. IL-10 mediated increase in PD-1 expression on DCs is STAT3 dependent.

Panel A shows representative western blot of phospho-STAT3 (p-stat3), STAT3, PD-1, and β-actin on lysates from CD11c+ DCs isolated from spleen and ascites of ID8 tumor-bearing mice. Panel B shows the bar graph (± SEM, N=3) and Panel C representative histograms of MFI values of PD-1 on BMDCs either treated with IL-10 alone, STAT3 inhibitor alone, or STAT3 inhibitor followed by IL-10 for 48 hrs. Filled histogram = isotype stain, solid dark line = Untreated, solid gray line = STAT3 inhibitor treated, dotted line = IL-10 + STAT3 inhibitor treated, and dashed line = IL-10 treated BMDCs. Panel D shows the representative western blot (left) of STAT3 on lysates from STAT3 siRNA treated BMDCs. Panel E shows the bar graph (± SEM, N=2–5) and the Panel F shows the representative histogram of PD-1 expression (MFI) on BMDCs either treated or untreated with IL-10 post siRNA transfection. Filled histogram = isotype stain, solid dark line = Ctrl siRNA treated, dotted dark line = Ctrl siRNA + IL-10 treated, solid gray line = STAT3 siRNA treated, and dotted gray line = STAT3 siRNA + IL-10 treated BMDCs. The p values were calculated with a Student’s T test. All data is representative of three individual experiments with similar results.

IL-10 mediated increase in PD-1 on the surface of DCs is STAT3 dependent

Various transcription factors have been implicated in either promoting or blocking PD-1 expression primarily in T cells (26, 27). We found that pSTAT3 and STAT3 levels were increased in the DCs isolated from ascites of ID8 ovarian tumor-bearing mice and correlated with increased PD-1 expression (Fig 2A). Since signaling emanating from IL-10 receptor involves the activation of STAT3 molecules via tyrosine phosphorylation, subsequent dimerization, and nuclear translocation resulting in binding to the DNA and gene transcription, we next asked if STAT3 activity has a role in IL-10-mediated up-regulation of PD-1 expression on DCs. BMDCs in this experiment were treated with STAT3 inhibitor (which prevents the dimerization and hence the nuclear translocation of STAT3) 1 hour prior to addition of IL-10. As shown in Figs. 2B–C, STAT3 inhibition completely reversed the IL-10-mediated increase in expression of PD-1 on the BMDCs. In a separate approach, we suppressed STAT3 in the BMDCs with siRNA (Fig. 2D) prior to the addition of IL-10, which resulted in a decrease in PD-1 expression (Figs. 2E–F). These results are consistent with the recent findings that implicate activated STAT3 as an important transcription factor in PD-1 expression (28).

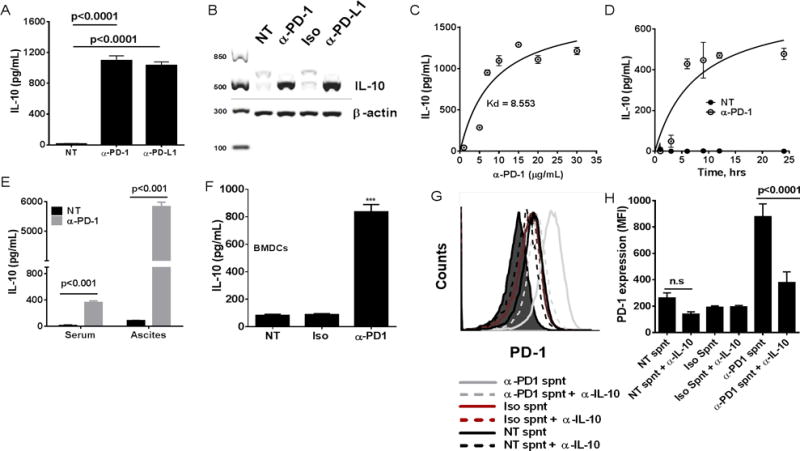

PD-1 blockade results in compensatory release of IL-10 by TIDCs

PD-1 blockade has been shown to be therapeutic in mouse models as well as in humans for certain types of cancers; yet a majority of patients among various tumor types don’t benefit (29). Although the response of T and B cells to PD-1 therapy continues to be extensively explored, the effects of PD-1 blockade on DCs are not well established (21). We have shown that TIDCs respond to PD-1 blockade by increasing co-stimulatory molecule and MHC class I expression as well as increasing antigen presentation, the effects that were primarily dependent on release of inhibition on NFκB pathway (21). Here we show that disruption of PD-1: PD-L1 axis on TIDCs using PD-1 blocking or PD-L1 blocking antibody leads to increased release of the immune regulatory cytokine, IL-10 (Fig. 3A). We also show that PD-1 blockade on TIDCs leads to an increase of IL-10 mRNA suggesting that the increased production of IL-10 upon PD-1 blockade is not merely due to enhanced release of pre-existing intracellular stores of IL-10 (Fig. 3B). The effect of different concentrations of PD-1 blocking antibody on IL-10 release by TIDCs was also measured. As shown in Fig. 3C, progressive increases in the concentration of the blocking antibody beyond 10 μg/ml did not progressively increase the production of IL-10. In all the experiments onwards, 10 μg/mL antibody was used in the in vitro experiments. From time course experiments, a significant difference in IL-10 release was detected as early as 7 hrs. (Fig. 3D). In the ID8 tumor-bearing mice, a significant increase in the IL-10 levels were detected both in the blood serum and ascites of mice that were treated with PD-1 blocking antibody compared to the untreated ones (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. PD-1 blockade on DCs enhances the release of IL-10 creating a feedback loop.

Panel A shows bar graph of mean (± SEM; N=3 replicates) IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) on the culture supernatants from the TIDCs treated for 24 hrs with irrelevant ab (Iso), PD-1 blocking ab (α-PD-1), or PD-L1 blocking ab (α-PD-L1). Panel B shows representative photo of an RT-PCR reaction evaluating both IL-10 and β-actin expression in TIDCs that were either treated with Iso or α-PD-1 for 24 hrs in vitro. Panel C shows line graph of IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) in the culture supernatants from the TIDCs treated for 24 hrs with increasing concentrations of anti-PD-1 blocking antibody. Each data point is the mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements. Panel D shows line graph of IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) in culture supernatants of TIDCs cultured in vitro over a time course. Each data point is the mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements. Panel E shows bar graph of mean IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) (± SEM; n=5) in ascites and blood serum of tumor bearing mice that were either untreated or treated with PD-1 blocking Ab as described in materials and methods. Panel F shows bar graph of mean (± SEM; N=3 replicates) IL-10 concentrations (pg/mL) on the culture supernatants from the IL-10 treated BMDCs (PD-1+) that were treated for 24 hrs as in A. Panel G shows representative histograms (left) and bar graph (± SEM, N=3) of MFI values of PD-1 (right) on BMDCs that were treated with conditioned media (culture supernatants) from BMDCs that were either untreated or treated with isotype Ab or PD-1 blocking Ab as in B. Culture supernatants were then either pretreated with IL-10 neutralizing Ab or untreated before adding on to the fresh cultures of BMDCs.

The effect of PD-1 blockade on BMDCs was also evaluated. PD-1+ BMDCs (BMDCs post treatment with IL-10 as shown in Fig. 1C) were treated with PD-1 blocking Ab for 24 hrs. PD-1 blockade on these cells also led to significantly increased release of IL-10 (Fig. 3F). In order to check if IL-10, released upon PD-1 blockade, can in turn lead to increased expression of PD-1 on surface of BMDCs, we collected the cell culture supernatants from the BMDCs treated as in Fig. 3F. Cell culture supernatants were then either left untreated or pre-treated with IL-10 neutralizing Ab before adding to fresh BMDC cultures. As shown in Figs. 3G–H, IL-10 pre-neutralization prevented the increase in PD-1 expression on BMDCs treated with conditioned media from BMDCs treated with anti-PD1. This shows that PD-1 and IL-10 form a feedback loop that amplifies upon PD-1 blockade. These results identify a mechanism in DCs whereby the blockade of PD-1 on these cells leads to a compensatory release of IL-10, hence potentially maintaining and fostering the suppressive environment despite PD-1 blockade.

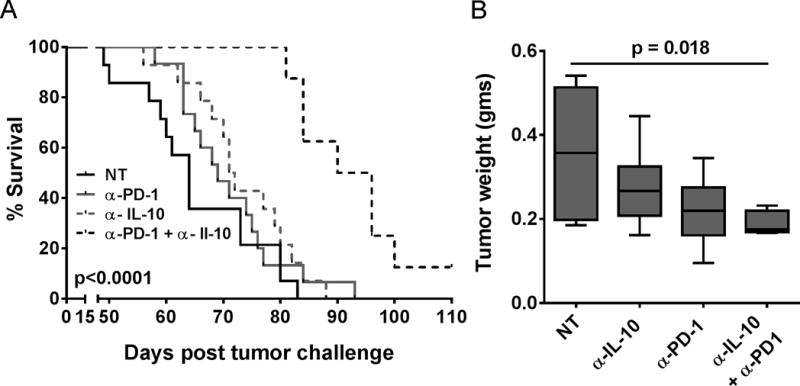

Combination treatment with PD-1 blocking Ab and IL-10 neutralization/IL-10R blockade reduces tumor burden and enhances survival in tumor bearing mice

Given the complex interdependent interaction between IL-10 and PD-1 that we observed in the above studies and their role in immune suppression in tumor microenvironment, we looked to see if combining these two therapies (PD-1 and IL-10/IL-10R blockade) has any effect in the generation of anti-tumor immunity. As shown in Fig. 4A, anti-PD-1 or anti-IL-10(R) as monotherapy had minimal effect on the overall survival or tumor burden; but the combination of these significantly delayed tumor growth and enhanced the survival of the tumor-bearing mice. Combination treatment also significantly reduced the tumor burden in the mice (Fig. 4B) compared to the control group.

Figure 4. Combination of PD-1 blockade and IL-10 neutralization reduces tumor burden and enhances survival of tumor bearing mice.

Panel A shows Kaplan-Meier plot of ID8 tumor-bearing mice (N=12–16) that were treated intraperitoneally with respective antibodies starting at day 25 post tumor implantation. Panel B shows mean tumor weights in gms (±SEM, N = 5–6), from different treatment groups, as measured at the time of ascites harvest.

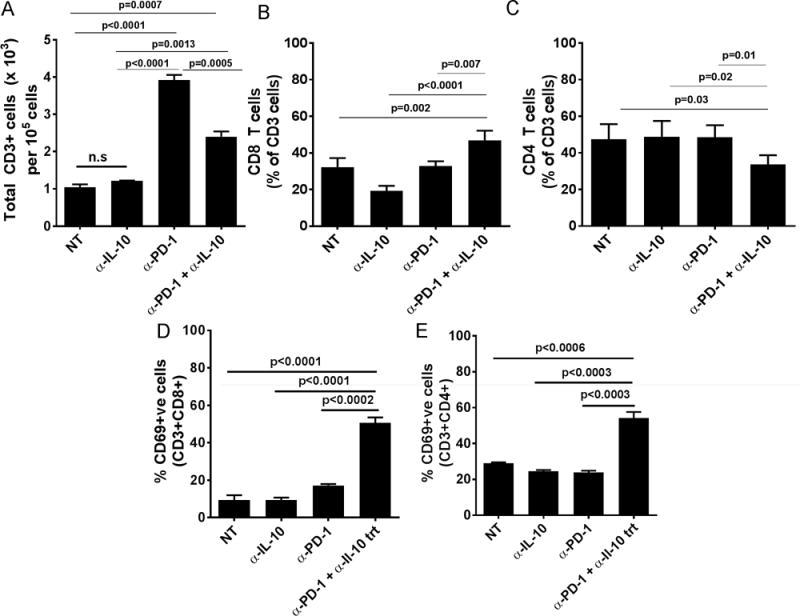

Combination treatment enhances the infiltration of immune effectors in the ascites of tumor bearing mice

In order to determine if the combination treatment modulated the quantity and quality of infiltrating immune cells, we looked for T and B-cell infiltrates in the ascites of tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was a significant increase in the total number of T cells in the ascites of tumor bearing mice that were treated with the PD-1 blocking antibody alone or the combination regimen of PD-1 blocking and IL-10(R) neutralizing antibodies. A slight increase in the fraction of CD8+ T cells and a slight decrease in the frequency of CD4+ T cells among the total CD3+ T cells compared to other treatment groups, were observed in the ascites of mice from the combination treatment group (Figs. 5B–C). Importantly and consistent with an inhibitory role of IL-10, we observed a robust increase in both the numbers of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the combination treatment group (Figs. 5D–E), whereas those levels were not different from controls in the monotherapy groups.

Figure 5. Combination treatment enhances the infiltration of activated T cells in the ascites of tumor bearing mice.

Panel A shows are the mean (±SEM, N=6) number of T cells per 1 × 105 leukocytes in the ascites of tumor-bearing mice from different treatment groups. Panels B–C show the mean (±SEM, N=4) percentages of CD8+ T cells (Panel B) and CD4+ T cells (Panel C) among total CD3 cells from the ascites of tumor bearing mice from treatment groups. Panels D–E show the mean (±SEM, N=5–7) percentages of CD69+ cells among CD8+ T cells (Panel D) and CD4+ T cells (Panel E) from the ascites of tumor bearing mice from treatment groups.

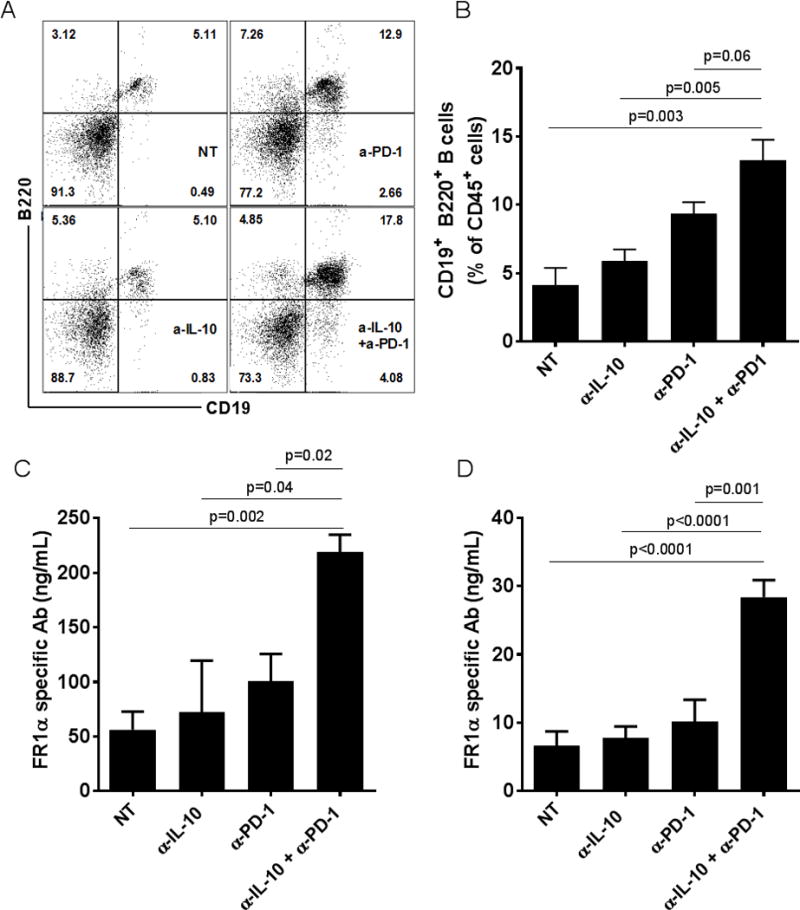

Similar to the changes in T cell numbers in the ascites, a significant increase in the frequency of B-cells (CD19+B220+) was observed in the ascites of tumor-bearing mice that were treated with PD-1 blocking antibodies alone or the combination regimen (Figs. 6A–B). Thus, we sought to determine if tumor antigen-specific antibody response was enhanced in the combination treatment group. Folate receptor alpha (FRα) is a well-known tumor antigen that has been shown to be overexpressed in various epithelial derived cancer cells, including ovarian cancer, and deemed capable of driving oncogenic transformation (30). In order to determine if an antigen specific antibody response was generated, the sera from different treatment groups were assayed for FRα-specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 6C, there were significantly increased levels of circulating FRα specific antibodies in the serum of mice from combination treatment group. Also, increased levels of FRα specific antibodies were observed in ascites of mice from the combination treatment group compared to the other groups (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that the combination of PD-1 blockade and IL-10(R) neutralization modulates the adaptive immunity by enhancing the infiltration of activated and antigen specific immune effectors into the TME.

Figure 6. Combination treatment enhances the antigen specific antibody response in tumor bearing mice.

Panel A shows the representative dot plot and Panel B shows a bar graph of the the mean frequency (±SEM., N=4–5 replicates) of CD19+B220+ B cells among CD45+ cells from the ascites of tumor-bearing mice. Panels C and D show are the mean levels (ng/ml) of FRα specific antibodies measured in the serum (±SEM, N=3 replicates) and ascites (±SEM, N=7 replicates) respectively, of mice from the different treatment groups.

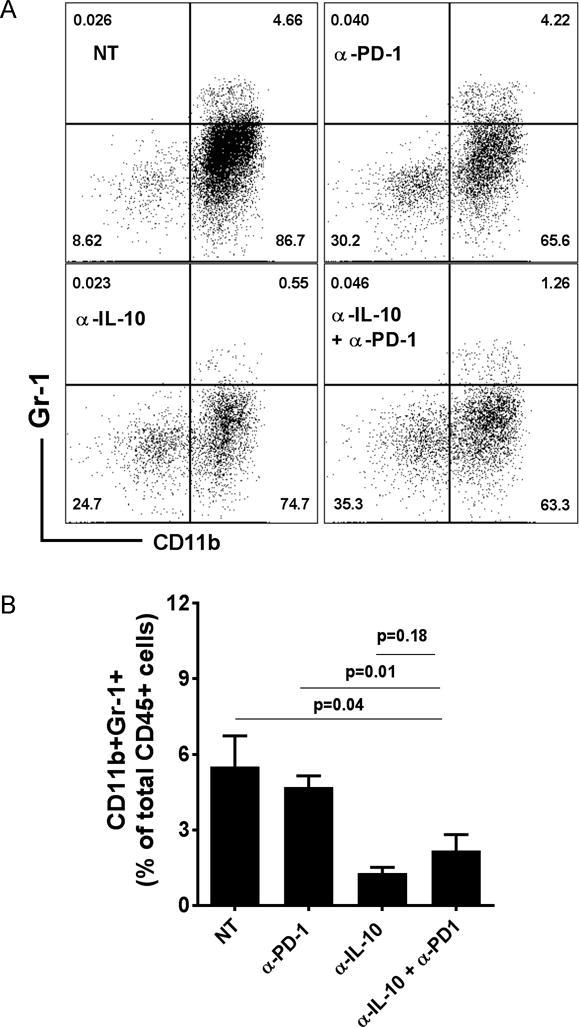

Combination treatment leads to a decrease in infiltration of MDSCs in the ascites

Immune suppressive cells present in the TME are adept at suppressing the effector responses against the tumor and hence promote tumor escape and progression. Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a subset of such suppressive cells that have been shown to play a major role in immune suppression in the ovarian cancer microenvironment (31). In a murine model of breast cancer, we have shown that a combination regimen of peptide vaccine (MHC Class I binding immunogenic peptides from rat neu (neu), legumain and β-catenin targeting tumor cells, cancer stem cells, and tumor associated macrophages) and PD-1 blocking antibody leads to a decrease in the frequency of MDSCs in the tumor (22, 32). In this study, we found that although anti-PD-1 treatment alone did not change the frequency of MDSCs in the ascites, anti-IL-10 and the combination treatment significantly reduced the frequency of MDSCs in the ascites of tumor bearing mice (Fig. 7A and 7B).

Figure 7. Combination treatment results in decreased infiltration of MDSCs in the ascites of tumor bearing mice.

Panel A shows the representative dot plots of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the ascites from different treatment groups. For analysis, live cells were pre-gated on CD45+ cells. Panel B shows the mean frequency (±SEM, N=5–7) of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the ascites of the different treatment groups.

DISCUSSION

In the present work, we have identified the TME-associated cytokine IL-10 as a critical regulator of PD-1/PD-L1 axis in the TME. First, we found that IL-10, a cytokine whose expression in increased in the TME of several cancers is capable of increasing PD-1 surface expression in a STAT-3 dependent manner. Second, we found that blockade of PD-1, with an antagonistic monoclonal antibody, on DCs led to increased release of IL-10 by DC which is further capable of increasing PD-1 expression on DCs; hence creating a vicious immune escape loop. Lastly, we show that PD-1 blockade and IL-10 signal antagonism as a combination therapy, using blocking antibodies, enhances the anti-tumor T and B cell immunity in ovarian cancer-bearing mice leading to significantly improved survival and decrease in tumor burden.

Although the critical role of DCs in initiating and shaping the response of immune system against pathogens and malignancies is widely acknowledged, the contribution of this subset, among tumor-infiltrating immune cells, in cancer malignancies remains obscure (33). Despite comprising up to 40% of infiltrating immune cells in the tumors, studies of the role of DCs in the TME have been conflicting. Recent studies have shown that DCs may switch phenotype from immune stimulatory to immune suppressive along the course of disease progression and PD-1 expression among TIDCs potentially contributes to this process by paralyzing the cells in a persistent immune suppressive state (4, 16). Various cytokines factors have been shown to upregulate PD-1 expression on T cells, including IFN-α, IFN-γ, and most of the γ chain cytokines (26, 34–37). To the best of our knowledge, the present work is the first demonstration that cytokines, particularly IL-10, is able to drive increased expression on DCs derived from either BMDCs or TIDCs. IL-10 is a cytokine whose levels have been shown to be elevated in the TME and blood of tumor bearing mice as well as ovarian cancer patients (18, 38–40). Despite elevated levels of IL-10 in sera of both tumor-bearing mice and humans, PD-1 is selectively expressed on the TIDCs and not their peripheral DCs (4, 21). Potential reasons for this observation is that IL-10, while elevated in sera, may not be at the levels needed to activate pdcd1 gene expression. Indeed, our recent work that shows that while elevated, IL-10 levels reach only about a mean of 0.65 ng/ml in the blood of patients which may not be enough to mediate PD-1 expression and/or systemic immune suppression (38). The IL-10-mediated increase in PD-1 expression on DCs was dependent on STAT-3 activity, as use of STAT-3 inhibitor or siRNA mediated knockdown of STAT3 both resulted in inability of IL-10 to increase PD-1 expression on DCs. These results support the previous findings implicating STAT-3 in mediating PD-1 expression on CD3/CD28 stimulated T cells upon IL-6 treatment (28).

A unique finding from our studies of PD-1 biology on TIDC is that the blockade of PD-1 results in augmented cytokine release including high level release of IL-10 (4). Thus, the observation that IL-10 drives PD-1 expression and that blockade of PD-1 results in highly elevated IL-10 production and release reveals a potentially rapid acting compensatory or adaptive immune regulatory loop which may foster escape from anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Indeed, we find that PD-1 blockade-induced IL-10 induces further PD-1 expression on the DCs favoring continued functional paralysis. Furthermore, IL-10 may also result in maintaining the immune suppressive phenotype of ovarian TIDCs by upregulating surface PD-L1 expression which as we previously showed is dominant means that TIDCs are able to mediate immune suppression in the ovarian cancer microenvironment (24). Although PD-1 and PD-L1 bind each other, they each have other ligands they bind (1). In this regard, future studies should examine if PD-L1 blockade in vivo, with or without IL-10(R) blockade, results in similar therapeutic efficacy in ovarian cancer as seen with the PD-1 blockade. Lastly, another potentially important finding is that IL-10 activated release of soluble PD-L1 (sPD-L1), a form of PD-L1 which induces apoptosis of T cells and has been repeatedly shown to be associated with poor outcome in patients with advanced cancers (41–45).

In addition to increased PD-L1 expression, the increased IL-10 can also act on many if not all immune cells, and blunt their effector responses (46). Interestingly, Sun and colleagues showed that blockade of PD-1 signaling led to an increase in IL-10R expression on tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells; hence rendering them increasing susceptible to IL-10 mediated inhibition and suggesting that compensatory mechanisms can also become activated in T cells following PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade (47). That IL-10 has a major role in evasion of immune-mediated regression of tumor following checkpoint blockade in the present model is demonstrated by the observation that combination treatment, blockade of PD-1 and IL-10(R) significantly increased the survival of tumor bearing mice and reduced the tumor burden. One potentially key finding from the current study is that although PD-1 was largely ineffective alone as a monotherapy it was able to nearly quadruple the numbers of T cells and double the number of B cells in the TME. Despite that, both subsets of effector lymphocytes appeared unable to activate as indicated by CD69 and antibody production for T and B cells, respectively, unless the mice also received anti-IL-10(R) therapy. This indicates that, in this model, IL-10 is a major compensatory suppression mechanism. These observations suggest that while PD-1 blockade alone may be ineffective as therapy in some tumors (29) owing to the induction of secondary suppressive mechanisms such as the one driven by IL-10, a combination of PD-1 blockade and disruption of IL-10/IL-10R signaling enhances the endogenous anti-tumor immunity resulting in improved survival and reduced tumor burden. While the paucity of intraperitoneal tumor tissue made it difficult to assess for the functional changes in the T and B cells induced by the combination therapy, it is notable that in our prior breast cancer studies that both Th1 and Th2 responses were associated with tumor regression in mice treated with the combination of vaccine and anti-PD-1 (22). These latter results suggest that other phenotypes may contribute to regression if appropriately coordinated with Th1 cell mediated immune responses.

We have previously shown that PD-1 blockade on TIDCs leads to an increase in IL-6 release (21). In the current study, we show that IL-6 is able to induce PD-1 expression on DCs, albeit the effect was much less pronounced compared to IL-10. Although not studied in ovarian cancer, the combination of IL-6 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has been evaluated in HCC and PDAC, with results showing synergistic anti-tumor effects (48, 49). Future studies should determine if IL-6 blockade combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade results in therapeutic efficacy in ovarian cancer comparable to the effects of IL-10 and PD-1 blockade.

The increase in FRα specific IgG may contribute to antitumor efficacy by directly blocking FRα dependent tumor cell proliferation and indirectly inducing antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) by binding to Fcγ receptors on NK cells as shown in a preclinical study of anti-folate receptor alpha antibody (50). Although, we showed that IL-10 is released by TIDCs at high levels following PD-1 blockade, there are other IL-10 sources, such as macrophages, Bregs and Tregs that could also contribute to the IL-10 mediated immune suppression (46). Future studies needs to evaluate if these cells, similarly to TIDCs, respond to PD-1 blockade by increasing IL-10 release. IL-10 mediates its immune suppressive effects both directly suppressing lymphocyte responses and indirectly by blocking DC functions (51–54). It is notable however, that IL-10 may under conditions have antitumor activity by enhancing the activity of cytotoxic T cells (55–57).

In conclusion, the approval of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 for the treatment of several cancers has generated widespread excitement in the field of tumor immunotherapy. But anti-PD-1 treatment is still suboptimal in various cancer subtypes and has not yet been tested in late stage clinical trials for ovarian cancer. In a recent clinical study of 20 patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, an overall response rate of 15% was achieved (58). Although these results are encouraging, there is still need for improvements in these therapies. Our results show that anti-PD-1 can induce a compensatory production of IL-10 by DCs infiltrating the ascites of ovarian cancer. Given the presence of IL-10 in high levels in the patients with ovarian carcinoma and its role in immune suppression, our results implicating it in regulation of PD-1 expression and consequently PD-1 blockade resulting in enhanced IL-10 production is significant. These results open up possibilities to explore if such combination therapy is a viable option in clinical settings for added benefits in patients receiving PD-1 based therapies. Other mechanisms of resistance to PD-1 therapy, including induction of other checkpoint molecules, lack of T cell infiltration, and low tumor mutational load, have also been identified in various tumors and combinatorial approaches to target these mechanisms are being explored (59).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the technical support of Laura Lewis-Tuffin and the Mayo Clinic Florida Flow Cytometry and Cell Analysis Shared Resource.

Grant support: This work was supported by the Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance (K.L. Knutson and L. Karyampudi), the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation (K.L. Knutson and K.R. Kalli), the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research (L. Karyampudi, K.L. Knutson, and M.J. Cannon), Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center grant P30-CA015083 (R. Diasio) and the Mayo Clinic Ovarian Cancer SPORE (P50-CA136393 to K.L. Knutson, E.L. Goode, M.S. Block, and M.J. Cannon).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin HT, Ahmed R, Okazaki T. Role of PD-1 in regulating T-cell immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;350:17–37. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H, Ishida Y, Tsubata T, Yagita H, et al. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:765–72. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krempski J, Karyampudi L, Behrens MD, Erskine CL, Hartmann L, Dong H, et al. Tumor-infiltrating programmed death receptor-1+ dendritic cells mediate immune suppression in ovarian cancer. J Immunol. 2011;186:6905–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carreno BM, Collins M. The B7 family of ligands and its receptors: new pathways for costimulation and inhibition of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091101.091806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins M, Ling V, Carreno BM. The B7 family of immune-regulatory ligands. Genome Biol. 2005;6:223. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-6-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:467–77. doi: 10.1038/nri2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheppard KA, Fitz LJ, Lee JM, Benander C, George JA, Wooters J, et al. PD-1 inhibits T-cell receptor induced phosphorylation of the ZAP70/CD3zeta signalosome and downstream signaling to PKCtheta. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders PA, Hendrycks VR, Lidinsky WA, Woods ML. PD-L2:PD-1 involvement in T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and integrin-mediated adhesion. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3561–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youngblood B, Oestreich KJ, Ha SJ, Duraiswamy J, Akondy RS, West EE, et al. Chronic virus infection enforces demethylation of the locus that encodes PD-1 in antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells. Immunity. 2011;35:400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youngblood B, Noto A, Porichis F, Akondy RS, Ndhlovu ZM, Austin JW, et al. Cutting edge: Prolonged exposure to HIV reinforces a poised epigenetic program for PD-1 expression in virus-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:540–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myklebust JH, Irish JM, Brody J, Czerwinski DK, Houot R, Kohrt HE, et al. High PD-1 expression and suppressed cytokine signaling distinguish T cells infiltrating follicular lymphoma tumors from peripheral T cells. Blood. 2013;121:1367–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-421826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, et al. Tumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood. 2009;114:1537–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, Li YF, Turcotte S, Tran E, et al. PD-1 identifies the patient-specific CD8(+) tumor-reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2246–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI73639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang MJ, Kim KM, Bae JS, Park HS, Lee H, Chung MJ, et al. Tumor-infiltrating PD1-Positive Lymphocytes and FoxP3-Positive Regulatory T Cells Predict Distant Metastatic Relapse and Survival of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:282–9. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scarlett UK, Rutkowski MR, Rauwerdink AM, Fields J, Escovar-Fadul X, Baird J, et al. Ovarian cancer progression is controlled by phenotypic changes in dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:495–506. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charbonneau B, Goode EL, Kalli KR, Knutson KL, Derycke MS. The immune system in the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer. Crit Rev Immunol. 2013;33:137–64. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.2013006813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustea A, Konsgen D, Braicu EI, Pirvulescu C, Sun P, Sofroni D, et al. Expression of IL-10 in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1715–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger S, Siegert A, Denkert C, Kobel M, Hauptmann S. Interleukin-10 in serous ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:328–33. doi: 10.1007/s002620100196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J, Ye F, Chen H, Lv W, Gan N. The expression of interleukin-10 in patients with primary ovarian epithelial carcinoma and in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. J Int Med Res. 2007;35:290–300. doi: 10.1177/147323000703500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karyampudi L, Lamichhane P, Krempski J, Kalli KR, Behrens MD, Vargas DM, et al. PD-1 Blunts the Function of Ovarian Tumor-Infiltrating Dendritic Cells by Inactivating NF-kappaB. Cancer Res. 2016;76:239–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karyampudi L, Lamichhane P, Scheid AD, Kalli KR, Shreeder B, Krempski JW, et al. Accumulation of memory precursor CD8 T cells in regressing tumors following combination therapy with vaccine and anti-PD-1 antibody. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2974–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knutson KL, Dang Y, Lu H, Lukas J, Almand B, Gad E, et al. IL-2 immunotoxin therapy modulates tumor-associated regulatory T cells and leads to lasting immune-mediated rejection of breast cancers in neu-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:84–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2003;9:562–7. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston PA, Grandis JR. STAT3 signaling: anticancer strategies and challenges. Mol Interv. 2011;11:18–26. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao C, Oestreich KJ, Paley MA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Ali MA, et al. Transcription factor T-bet represses expression of the inhibitory receptor PD-1 and sustains virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses during chronic infection. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:663–71. doi: 10.1038/ni.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:219–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin JW, Lu P, Majumder P, Ahmed R, Boss JM. STAT3, STAT4, NFATc1, and CTCF regulate PD-1 through multiple novel regulatory regions in murine T cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:4876–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen MF, Greibe E, Skovbjerg S, Rohde S, Kristensen AC, Jensen TR, et al. Folic acid mediates activation of the pro-oncogene STAT3 via the Folate Receptor alpha. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1356–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan AN, Kolomeyevskaya N, Singel KL, Grimm MJ, Moysich KB, Daudi S, et al. Targeting myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment enhances vaccine efficacy in murine epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:11310–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obermajer N, Muthuswamy R, Odunsi K, Edwards RP, Kalinski P. PGE(2)-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer research. 2011;71:7463–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran Janco JM, Lamichhane P, Karyampudi L, Knutson KL. Tumor-Infiltrating Dendritic Cells in Cancer Pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2015;194:2985–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao G, Deng A, Liu H, Ge G, Liu X. Activator protein 1 suppresses antitumor T-cell function via the induction of programmed death 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206370109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oestreich KJ, Yoon H, Ahmed R, Boss JM. NFATc1 regulates PD-1 expression upon T cell activation. J Immunol. 2008;181:4832–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terawaki S, Chikuma S, Shibayama S, Hayashi T, Yoshida T, Okazaki T, et al. IFN-alpha directly promotes programmed cell death-1 transcription and limits the duration of T cell-mediated immunity. J Immunol. 2011;186:2772–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinter AL, Godbout EJ, McNally JP, Sereti I, Roby GA, O’Shea MA, et al. The common gamma-chain cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 induce the expression of programmed death-1 and its ligands. J Immunol. 2008;181:6738–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Block MS, Maurer MJ, Goergen K, Kalli KR, Erskine CL, Behrens MD, et al. Plasma immune analytes in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Cytokine. 2015;73:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coosemans A, Decoene J, Baert T, Laenen A, Kasran A, Verschuere T, et al. Immunosuppressive parameters in serum of ovarian cancer patients change during the disease course. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1111505. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1111505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Napoletano C, Bellati F, Landi R, Pauselli S, Marchetti C, Visconti V, et al. Ovarian cancer cytoreduction induces changes in T cell population subsets reducing immunosuppression. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2748–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi N, Iwasa S, Sasaki Y, Shoji H, Honma Y, Takashima A, et al. Serum levels of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 as a prognostic factor on the first-line treatment of metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1727–38. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, Wang L, Liu WJ, Xia ZJ, Huang HQ, Jiang WQ, et al. High post-treatment serum levels of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 predict early relapse and poor prognosis in extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:33035–45. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkelmeier F, Canli O, Tal A, Pleli T, Trojan J, Schmidt M, et al. High levels of the soluble programmed death-ligand (sPD-L1) identify hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a poor prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossille D, Gressier M, Damotte D, Maucort-Boulch D, Pangault C, Semana G, et al. High level of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 in blood impacts overall survival in aggressive diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma: results from a French multicenter clinical trial. Leukemia. 2014;28:2367–75. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frigola X, Inman BA, Lohse CM, Krco CJ, Cheville JC, Thompson RH, et al. Identification of a soluble form of B7-H1 that retains immunosuppressive activity and is associated with aggressive renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1915–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5771–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Z, Fourcade J, Pagliano O, Chauvin JM, Sander C, Kirkwood JM, et al. IL-10 and PD-1 cooperate to limit the activity of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mace TA, Shakya R, Pitarresi JR, Swanson B, McQuinn CW, Loftus S, et al. IL-6 and PD-L1 antibody blockade combination therapy reduces tumour progression in murine models of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2016 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H, Shen J, Lu K. IL-6 and PD-L1 blockade combination inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cancer development in mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ebel W, Routhier EL, Foley B, Jacob S, McDonough JM, Patel RK, et al. Preclinical evaluation of MORAb-003, a humanized monoclonal antibody antagonizing folate receptor-alpha. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruffell B, Chang-Strachan D, Chan V, Rosenbusch A, Ho CM, Pryer N, et al. Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:623–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma S, Stolina M, Lin Y, Gardner B, Miller PW, Kronenberg M, et al. T cell-derived IL-10 promotes lung cancer growth by suppressing both T cell and APC function. J Immunol. 1999;163:5020–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seo N, Hayakawa S, Takigawa M, Tokura Y. Interleukin-10 expressed at early tumour sites induces subsequent generation of CD4(+) T-regulatory cells and systemic collapse of antitumour immunity. Immunology. 2001;103:449–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emmerich J, Mumm JB, Chan IH, LaFace D, Truong H, McClanahan T, et al. IL-10 directly activates and expands tumor-resident CD8(+) T cells without de novo infiltration from secondary lymphoid organs. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3570–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanikawa T, Wilke CM, Kryczek I, Chen GY, Kao J, Nunez G, et al. Interleukin-10 ablation promotes tumor development, growth, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:420–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berman RM, Suzuki T, Tahara H, Robbins PD, Narula SK, Lotze MT. Systemic administration of cellular IL-10 induces an effective, specific, and long-lived immune response against established tumors in mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Ikeda T, Minami M, Kawaguchi A, Murayama T, et al. Safety and Antitumor Activity of Anti-PD-1 Antibody, Nivolumab, in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4015–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim JM, Chen DS. Immune escape to PD-L1/PD-1 blockade: seven steps to success (or failure) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1492–504. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.