Abstract

Maintaining immune tolerance requires the production of Foxp3-expressing regulatory T (Treg) cells in the thymus. Activation of NF-κB transcription factors is critically required for Treg cell development, partly via initiating Foxp3 expression. NF-κB activation is controlled by a negative feedback regulation through the ubiquitin editing enzyme A20, which reduces proinflammatory signaling in myeloid cells and B cells. In naive CD4+ T cells, A20 prevents kinase RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. Using mice deficient for A20 in T lineage cells, we show that thymic and peripheral Treg cell compartments are quantitatively enlarged because of a cell-intrinsic developmental advantage of A20-deficient thymic Treg differentiation. A20-deficient thymic Treg cells exhibit reduced dependence on IL-2 but unchanged rates of proliferation and apoptosis. Activation of the NF-κB transcription factor RelA was enhanced, whereas nuclear translocation of c-Rel was decreased in A20-deficient thymic Treg cells. Furthermore, we found that the increase in Treg cells in T cell–specific A20-deficient mice was already observed in CD4+ single-positive CD25+ GITR+ Foxp3− thymic Treg cell progenitors. Treg cell precursors expressed high levels of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily molecule GITR, whose stimulation is closely linked to thymic Treg cell development. A20-deficient Treg cells efficiently suppressed effector T cell–mediated graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, suggesting normal suppressive function. Holding thymic production of natural Treg cells in check, A20 thus integrates Treg cell activity and increased effector T cell survival into an efficient CD4+ T cell response.

Tcell–mediated immune tolerance requires induced and naturally derived regulatory T (Treg) cells, the latter generated during thymic T cell selection. Foxp3 is a master transcription factor for the development and function of Treg cells, and defective Foxp3 expression results in severe autoimmune phenotypes in mice and men (1, 2). Although the regulation of naturally derived Treg cell development is still incompletely understood (3), it is clear that TCR stimulation along with signals from common γ-chain (γc) receptor–linked cytokines IL-2 and IL-7 are essential to induce Foxp3 expression and Treg cell development (4). Upon TCR engagement, protein kinase C and the Carma1/Bcl10/Malt1 protein complex are recruited to finally induce NF-κB transcription factor activity, key regulator of lymphocyte differentiation, expansion, activation, and survival (5, 6). Mice bearing defects in the TCR signaling pathway (including TAK1, Bcl10, CARMA1, protein kinase C u, and IKK2) show selective impairments in development and function of Treg cells, whereas conventional T cell development seems to be less affected (7–12). Furthermore, mice deficient for γc receptors, which transmit signaling initiated by homeostatic cytokines such as IL-2 and whose expression is regulated by various mechanisms including the NF-κB pathway, also lack Treg cells (13–15). The NF-κB transcription factor c-Rel is highly expressed in thymic Treg cells and directly promotes transcription of Foxp3 in the thymus. Accordingly, Treg cell numbers are strongly reduced in the absence of the NF-κB family proteins p50 and c-Rel (16–18). One of the key regulators of both NF-κB activation and TCR signaling is the ubiquitin editing enzyme A20, which limits NF-κB signaling after activation by TNF, IL-1/TLRs, and the TCR (19). Consistent with this, A20-deficient mice are hypersensitive to LPS and TNF exposure, and die perinatally because of severe inflammation and multiorgan failure (20). Lineage-specific A20 deficiency in various cell types such as B cells, dendritic cells, intestinal epithelial cells, and hepatocytes results in autoimmunity, higher susceptibility to inflammatory diseases, or hepatocellular carcinoma (21–25), and clinical studies link genetic A20 polymorphisms to human autoimmune and lymphoproliferative disorders (26–30). In T cells, TCR activation and Carma1/Bcl10/Malt1 complex formation is followed by K63-linked polyubiquitination of MALT1, resulting in IκB kinase complex activation and NF-κB signaling. A20 cleaves the polyubiquitin chains from MALT1, thus suppressing NF-κB activation. In return, MALT1 also has a proteolytic activity, which can inactivate A20 (31, 32). In CD8+ T cells, A20 deletion leads to sustained expression of the NF-κB family members c-Rel/RelA and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 (33). In CD4+ T cells, A20 is essential for survival and expansion by promoting autophagy and protecting from necroptotic cell death (34, 35). Intriguingly, unrestricted necroptosis in A20-deficient CD4+ cells affects both the Th1 and the Th17 compartment, leading to reduced inflammation in a CD4+ T cell–dependent model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis (34). In NKT cell sub-lineages NKT1 and NKT2, A20 was also shown to restrict TCR-dependent activation and survival, thereby controlling NKT cell differentiation (36). However, the role of A20 for Treg cell differentiation, central modulators of inflammatory responses in vivo, remains unexplored. In this article, we demonstrate that A20 regulates the de novo generation of naturally derived Treg cells in the thymus in a cell-intrinsic fashion independent of γc-cytokine IL-2 signaling. This developmental advantage could be attributed to enhanced emergence of thymic Treg cell progenitors. Importantly, the functionality of A20-deficient Treg cells is unchanged in vitro and in the prevention of lethal allogeneic T cell activity in a preclinical model of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice with cell type–specific deficiency of A20 in T cells were generated by breeding A20F/F mice (25) with CD4Cre transgenic mice (37) as previously described (38). C57BL/6 (H-2Kb, Thy-1.2) and BALB/c (H-2Kd, Thy-1.2) mice were purchased from Janvier Labs. Mice were between 6 and 12 wk of age at the onset of experiments if not indicated otherwise. Animal protocols were approved by the local regulatory agency (Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany).

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and GVHD

Allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantations were performed as previously described (39). In brief, female, 6- to 8-wk-old BALB/c recipients were lethally irradiated with total body irradiation (TBI; 2 × 4.5 Gy). Directly after the second irradiation step mice received 5 × 106 T cell– depleted C57BL/6 wild type (WT) BM cells for reconstitution. T cell depletion of freshly isolated BM cells was performed using CD90.2 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). In addition, some mice received 2 × 105 CD8+ T cells and 2 × 105 CD4+ CD25− effector T cells with or without 6 × 105 CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells as indicated in the figure legends. All T cell subsets were isolated from complete splenocytes using the Treg cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and the CD8 T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Syngeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and competitive T cell development

CD45.1+ CD45.2+ (double-positive) C57BL/6 WT mice were used for competitive T cell development experiments. Conditioning therapy of C57BL/6 recipient mice before the syngeneic BM transplantation was performed as previously described (40). After conditioning therapy (2 × 5.5 Gy), recipient mice received 2.5 × 106 T cell–depleted C57BL/6 WT CD45.1+ CD45.2− BM cells. In addition, recipient mice received either 2.5 × 106 A20F/F CD4cre− or 2.5 × 106 A20F/F CD4cre+ T cell–depleted C57BL/6 BM cells, expressing only CD45.2, but not CD45.1. Mice were analyzed 3 mo after transplantation. Exact ratios of transplanted and engrafted CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ BM cells were determined by analysis of CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression of CD4− CD8− cells. The engraftment ratio was calculated for all transplanted animals separately. Further analysis of cell subsets was normalized to this ratio.

Flow cytometry and Abs

All Abs were purchased from eBioscience, BioLegend, and Miltenyi Biotec. For cell viability analysis, a near-infrared Live/Dead reagent (Molecular Probes; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following Abs were used for cell surface or intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis: CD4 (GK 1.5/RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD25 (PC61.5), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), c-Rel (REA397), Foxp3 (FJK16s), GITR (DTA-1), and KI-67 (16A8). Cells were stained in PBS supplemented with 2.5% BSA using fluorochrome-conjugated Abs against specific cell surface markers in different dilutions for 20 min at 4°C. For Foxp3 staining, the Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set (eBioscience) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Active caspase-3 stain was performed directly before further viability and cell surface staining using the CaspGLOW Fluorescein Active Caspase-3 Staining Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In vivo cell proliferation was analyzed using the Click-iT Plus EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assay was performed 24 h after i.p. injection of EdU. Treatment dose of EdU (50 mg/kg per mouse) was used as previously described (41). Analyses of cell populations were performed by flow cytometry with a FACSCanto II (BD). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Flow cytometry sorting was performed with a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences). The anti-mouse IL-2 Ab (JES6-1A12; BioXCell) was used to neutralize IL-2 in vivo. In indicated experiments, 500 mg of anti–IL-2 was injected i.p. 6 and 3 d before analysis.

Imaging flow cytometry

Thymocytes were subjected to MACS-based depletion of CD8+ T cells (CD8 microbeads; Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were then either left untreated or were stimulated with 100 nM PMA (Sigma) and 1 mM ionomycin (Calbiochem) for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. Extracellular and intracellular Foxp3 staining was performed as described earlier. Intracellular c-Rel staining was performed overnight. DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was applied as a nuclear stain subsequent to Ab stainings. Stained cell suspensions were acquired on an ImageStreamX Mark II (Amnis; Merck Millipore) imaging flow cytometer. Data analysis was performed using the wizard for nuclear translocation of the IDEAS software (Amnis), where determination of nuclear translocation is based on a similarity score that quantifies the correlation of nuclear stain and translocation probe intensities. High correlation and thus high similarity scores represent strong nuclear translocation, whereas low scores are indicative of cytoplasmic localization (42).

Phospho–NF-κB p65 (S536) phosphoflow

Cells were either left untreated or were stimulated with 100 nM PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM ionomycin (Calbiochem) for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2. After washing the cells with PBS, live/dead cell staining was performed with a fixable viability dye (eBioscience) followed by surface staining. Cells were fixed with 2% PFA for 40 min, permeabilized by two washes with Perm/Wash buffer (eBioscience), and stained overnight with anti-Foxp3 and anti–phospho-NFKBp65 (Ser536) (93H1; Cell Signaling) Abs. After two washes with Perm/Wash buffer, cells were stained with an allophycocyanin-labeled anti-rabbit IgG Ab (A10931; Invitrogen).

Isolation of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells with magnetic cell sorting

CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells were isolated from splenic single-cell suspensions using the MACS Treg cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Treg cell suppression assay

MACS-sorted CD4+ CD25− T effector cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells per well. Soluble anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml; clone 2C11; BD Pharmingen) and irradiated APCs were used in a 1:2 ratio. APCs as stimulator cells were prepared from syngeneic mice by depleting the CD4+ T cell fraction using anti-CD4 microbeads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). For suppression, CD4+ CD25+ MACS-sorted A20F/F CD4cre+ or A20F/F CD4cre− Treg cells were added at the indicated ratio to A20F/F CD4cre− T effector cells. Proliferation of CD4+ CD25− T effector cells was analyzed using the CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of proliferating cells was analyzed after 72 h.

Treg cell expansion and differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells in vitro

Treg cell expansion

Treg cells (CD4+ CD25+) were prepared by FACS or MACS isolation. Cells were activated with anti-murine CD3 (1 μg/ml; clone 17A2; BioLegend) plus soluble anti-murine CD28 (1 μg/ml; clone 37.51; BioLegend) with or without 50 international units human IL-2 (PeproTech) after precoating of 96-well tissue culture plates (Sigma-Aldrich) with 10 μg/ml F(ab′)2 fragment of IgG H+L (Jackson ImmunoResearch). In indicated experiments, cells were activated with soluble beads preloaded with CD3 and CD28 Abs according to the manufacturer's instructions (130-095-925; Miltenyi Biotec). At indicated time points after activation (days 4 and 8), intracellular Foxp3 was stained and Treg cells were counted. Cell number was determined with flow cytometry cell counting beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fischer Scientific).

Differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells

Naive CD4+ T cells (CD62L+ CD44−) were prepared by FACS; sorted cells were activated with anti-murine CD3 (0.2 μg/ml) plus soluble anti-murine CD28 (1 μg/ml). Generation of induced Treg (iTreg) cells was performed in the presence of 10 ng/ml human TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) with or without 50 international units human IL-2. CD4+ T cells were cultured under polarizing conditions (for 4 d), and cell polarization was assessed by intracellular Foxp3 staining. Cell number was determined as described above.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism version 6 was used for statistical analysis. Survival was analyzed using the log-rank test. Differences between means of experimental groups were analyzed using the one- or two-tailed unpaired Student t test, corresponding to the distribution shape of our observations. We used ordinary one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and always performed Dunnett's test for multiple-test corrections. The applied statistical tests are indicated in the figure legends. For visual clarity, data are shown as mean ± SEM throughout.

Results

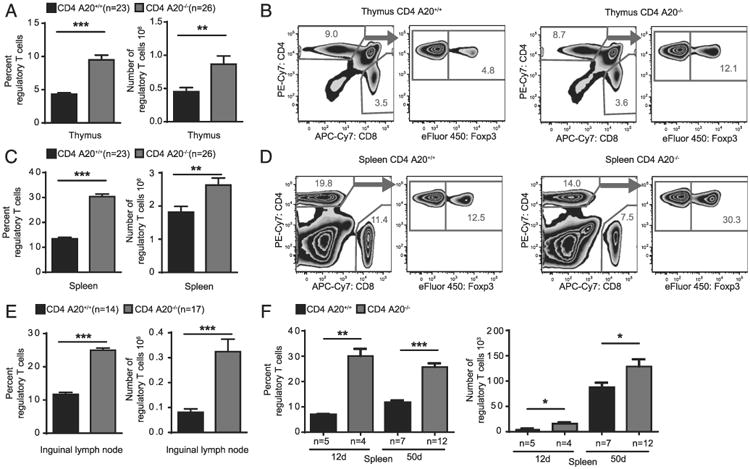

Increased numbers of Treg cells in mice with T cell–specific A20 deletion

To investigate the role of A20 in T cells, we analyzed A20F/F CD4Cre+ mice, which specifically lack A20 in T cells. The population of Foxp3+ Treg cells was quantitatively enlarged in thymus, spleen, and inguinal lymph nodes of naive A20F/F CD4Cre+ mice (CD4 A20−/−) as compared with A20F/F CD4Cre− mice (CD4 A20+/+) (Fig. 1A–E, Supplemental Fig. 1A). At the same time, the total thymic CD4+ and CD8+ T cell population was not significantly different between CD4 A20−/− mice and controls. In the spleen, both total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations were reduced in CD4 A20−/− mice (Fig. 1B, 1D, Supplemental Fig. 1B, 1C), which is in line with previous observations (38). To exclude a bias of age on the development of Treg cells (43), we analyzed splenocytes of young (12-d-old) and adult (50-d-old) CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice. We found frequencies and absolute numbers of Treg cells to be significantly increased in both young and adult mice (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

Increased numbers of Treg cells in mice lacking A20 specifically in T cells. (A) Thymocytes of adult A20F/F CD4Cre− (CD4 A20+/+) and A20F/F CD4Cre+ (CD4 A20−/−) mice were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-Foxp3, and live/dead reagent. The population of Foxp3+ Treg cells of live CD4+ CD8− cells was determined by flow cytometry (left panel), and total Treg cell number was calculated (right panel). Pooled data of five independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (B) Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of the experiments depicted in (A). (C) Splenocytes of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were stained as in (A). The population of Foxp3+ Treg cells of live CD4+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (left panel), and total Treg cell number was calculated (right panel). Pooled data of five independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (D) Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of the experiments depicted in (C). (E) Lymph node cells of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were stained as in (A). The Foxp3+ Treg cell fraction of all live CD4+ cells was determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (F) Splenocytes of 12- and 50-d–old CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were analyzed for CD4 and Foxp3 expression by flow cytometry. Treg cell fractions of live CD4 cells and absolute Treg cell numbers are shown. Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Data were analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons or one- and two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

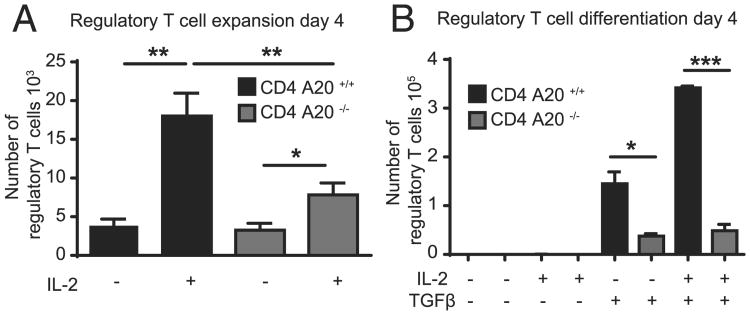

A20-deficient T cells show reduced Treg cell expansion and differentiation in vitro

To investigate whether this absolute increase of peripheral Treg cell numbers in CD4 A20−/− mice was due to enhanced sensitivity of Treg cells to external proliferation signals, we stimulated FACS-purified CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells from CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice in vitro with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and IL-2 (44). Although IL-2 induced a significant increase in the absolute numbers of both control and A20-deficient Treg cells after 4 or 8 d of culture, the in vitro expansion of A20-deficient Treg cells was significantly less pronounced (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Fig. 2A). Next, we wanted to know whether enhanced sensitivity to peripheral differentiation signals of Treg cells was responsible for the enlarged Treg cell population in CD4 A20−/− mice. However, stimulation of FACS-purified CD62Lhigh CD44low naive T cells with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and either TGF-β alone or TGF-β and IL-2 resulted in decreased proportions and absolute numbers of A20-deficient compared with control Treg cells (Fig. 2B, Supplemental Fig. 2B). In summary, the sensitivity to expansion or differentiation signals of A20-deficient Treg cells or CD4+ T cells in vitro was reduced compared with controls, and thus could not explain the increase of total Treg cell numbers in CD4 A20−/− mice.

Figure 2.

A20-deficient T cells show reduced Treg cell expansion and differentiation in vitro. (A) A total of 50 × 103 FACS-sorted A20+/+ and A20−/− CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells was cultured in vitro in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 with or without IL-2 for 4 d, and absolute numbers of live cells were determined. One representative of three independent experiments is shown. (B) A total of 40 × 103 CD4+ CD62Lhigh CD44low A20+/+ and A20−/− T cells was cultured in vitro in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28, ± IL-2 and ± TGF-β for 4 d. Conversion toward a Treg cell phenotype was determined by intracellular Foxp3 staining, and absolute numbers of live cells were determined. One representative of three independent experiments is shown. Data were analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

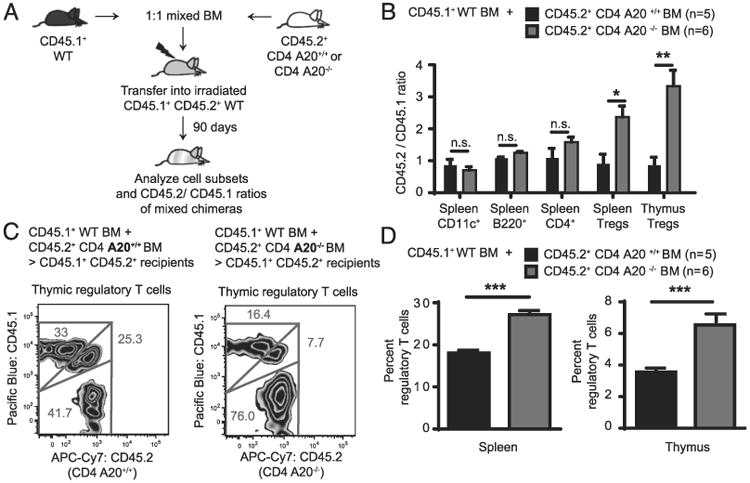

A20 deficiency in T cells drives thymic Treg cell development cell-intrinsically

We assumed that an intrinsic effect could account for increased Treg cell development and enhanced Treg cell numbers in CD4 A20−/− animals. To test this hypothesis, we established a model of competitive BM engraftment and T cell development in which CD45.1+ CD45.2+ double-positive C57BL/6 recipient mice were lethally irradiated (TBI) to eradicate the recipient hematopoietic system. Then T cell–depleted BM cells mixed in a 1:1 ratio from both CD45.1 (WT) and CD45.2 (either CD4 A20+/+ or CD4 A20−/−) donors (Fig. 3A) were introduced for hematopoietic reconstitution.

Figure 3.

A20 deficiency in T cells drives thymic Treg cell development cell-intrinsically. (A) CD45.1+ CD45.2+ double-positive C57BL/6 recipient mice received 11 Gy TBI and were then transplanted with 2.5 × 106 T cell–depleted C57BL/6 WT BM expressing only CD45.1. In addition, recipient mice received either 2.5 × 106 CD4 A20+/+ or 2.5 × 106 CD4 A20−/− T cell–depleted C57BL/6 BM, both expressing only CD45.2. (B) Three months after transplantation, numbers and frequencies of CD11c+ dendritic cells, B220+ B cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD4+ CD8− Foxp3+ Treg cells were determined in thymus and spleen of corresponding animals by FACS analysis. CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression of cell subsets were analyzed, and CD45.2+/CD45.1+ ratios were calculated. Residual recipient cells were identified (CD45.1+ CD45.2+ double-positives) and were excluded from the calculation. One representative of two independent experiments is shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (C) Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of thymic Treg cells of the analysis depicted in (B). (D) Percentage of Foxp3+ Treg cells of CD4+ CD8− cells were determined in thymus and spleen of recipient mice that were transplanted as described in (A). One representative of two independent experiments is shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In this model, tracing the genetic markers by FACS analysis allows to quantify whether one of the BM compartments transferred to the host at day 0 (WT plus CD4 A20+/+ or WT plus CD4 A20−/−) would outperform another or would favor the development of certain T cell or other immune cell subsets. Ninety days after transplantation, recipients that had received CD45.1 WT + CD45.2 CD4 A20+/+ BM showed CD45.2 and CD45.1 Treg cell fractions with a balanced ratio. In contrast, recipients that had received CD45.1 WT + CD45.2 CD4 A20−/− BM showed an ∼2.6-fold (spleen) and 3.8-fold (thymus) increased ratio between CD45.2+ A20−/− and CD45.1 WT Treg cell fractions (Fig. 3B, 3C). Ratios of CD45.2/CD45.1 populations of splenic dendritic cells, B cells, and total CD4+ T cells did not differ significantly between CD4 A20+/+ BM or CD4 A20−/− BM (Fig. 3B). Accordingly, we found increased fractions of Foxp3+ Treg cells within the CD4+ T cell compartment in spleen and thymus of mice that had received CD45.1 WT plus CD4 A20−/− BM compared with mice that had received CD45.1 WT plus CD4 A20+/+ BM (Fig. 3D), whereas populations of CD11c+, B220+, and CD4+ T cells were similar in both cohorts (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Together with our findings that in vitro Treg cell differentiation and expansion through common external stimuli were not enhanced in CD4 A20−/− cells, these data suggest that early events in the BM or thymus favor Treg cell development in CD4 A20−/− mice via cell-intrinsic mechanisms.

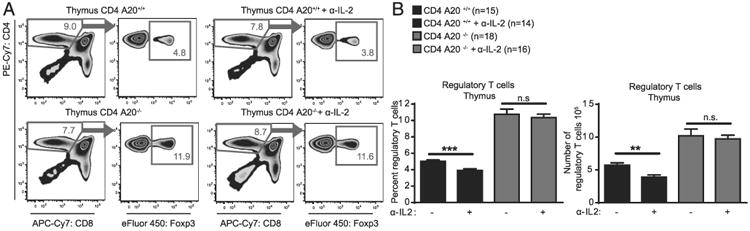

A20 deficiency reduces the dependence of thymic Treg cells on IL-2

IL-2 was shown to play a crucial role in thymic Treg cell development by stabilizing the Foxp3+ phenotype and counterbalancing Foxp3-induced apoptosis (45). To investigate effects of IL-2 signaling on A20−/− Treg cells, we used in vivo application of an anti–IL-2 Ab that antagonizes effects of IL-2 (46). We injected anti–IL-2 into naive CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice, and analyzed T cell frequencies and numbers 6 d later. The number of total thymocytes and the frequency of CD4 single-positive (CD4SP) T cells were unchanged after 6 d in all groups (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Fig. 2D). However, frequencies and numbers of Treg cells in the thymus of CD4 A20+/+ mice were significantly reduced 6 d after injection of anti–IL-2 (Fig. 4). In contrast, CD4 A20−/− mice showed unchanged Treg frequencies after neutralization of IL-2 (Fig. 4). We examined the expression of the integral IL-2R component IL-2RA (CD25) in the population of Foxp3+ CD4+ Treg cells to test whether differences in IL-2R expression, which could possibly lead to altered sensitivity for IL-2, contributed to this phenotype. We found similar proportions of CD25+ and CD25− Foxp3+ Treg cells in CD4 A20+/+ or CD4 A20−/− mice and marginally decreased CD25 expression levels of CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells in CD4 A20−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 2E). Overall, these data indicate that the dependence of thymic Treg cell development on IL-2 is reduced in the absence of A20.

Figure 4.

A20 deficiency reduces the dependence of thymic T regulatory cells on IL-2. (A) CD4 A20+/+ or CD4 A20−/− mice were injected i.p. with anti–IL-2 neutralizing Ab and analyzed 6 d after first treatment. One group of each genotype was left without anti–IL-2 treatment as control. Thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-Foxp3, and live/dead reagent, and the population of Foxp3+ Treg cells of live CD4+ CD8− cells was determined by flow cytometry. Shown are the gating strategy and representative FACS plots of thymic Treg cells. (B) Experiments and analyses as described in (A). (Left panel) Frequency of Foxp3+ Treg cells of CD4+ CD8− cells. (Right panel) Absolute number of Foxp3+ CD4+ CD8− Treg cells. Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

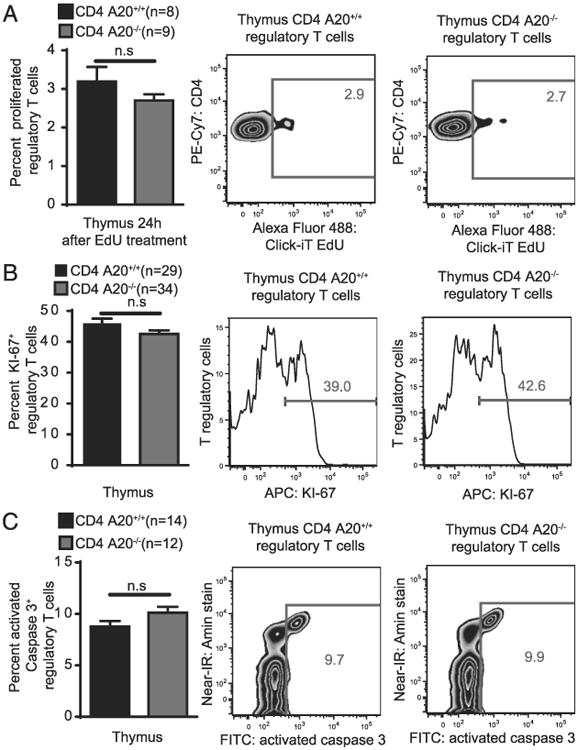

Thymic A20-deficient Treg cells show unchanged proliferation and apoptosis

We next wanted to analyze the role of A20 for Treg proliferation and apoptosis in vivo. First, we treated CD4 A20−/− and CD4 A20+/+ mice with EdU, a nucleoside analog that is incorporated into DNA during active DNA synthesis and can be analyzed by flow cytometry. We found similar frequencies of EdU+ thymic Treg cells in CD4 A20−/− and CD4 A20+/+ mice 24 h after EdU injection (Fig. 5A). We then tested the expression rate of the proliferation marker KI-67 (47) in thymic Treg cells and again found no significant difference between CD4 A20−/− and CD4 A20+/+ mice (Fig. 5B). Next, we determined the frequency of thymic Treg cells that stain positive for activated caspase-3 to evaluate the role of apoptosis in Treg cells but found no significant difference between CD4 A20−/− and CD4 A20+/+ mice (Fig. 5C). In contrast, when analyzing Foxp3−, CD4SP thymic cells, we observed reduced frequencies of EdU+, similar frequencies of KI-67+, and increased frequencies of activated caspase-3+ cells in CD4 A20−/− versus A20+/+ mice (Supplemental Fig. 3). Our data indicate that A20 does not regulate Treg cell proliferation or apoptosis in vivo under the conditions tested in our study and suggest that these mechanisms are not responsible for the enlarged Treg cell population in CD4 A20−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Thymic A20-deficient Treg cells show unchanged proliferation and apoptosis. (A) CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were treated with 50 mg/kg EdU. Twenty-four hours after application, harvested thymocytes were stained with live/dead reagent, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-Foxp3, and EdU Click-iT staining was performed. The population of EdU+ Treg cells of all Foxp3+ Treg cells was determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of two independent experiments are shown (left panel). Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of the experiments are shown (right panels). (B) Thymocytes of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were stained with live/dead reagent, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-Foxp3, and anti–KI-67. The population of KI-67+ Treg cells of all Foxp3+ Treg cells was determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of six independent experiments are shown (left panel). Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Gating strategy and representative histograms of the experiments are shown (right panels). (C) Thymocytes of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were incubated with an active caspase-3 staining reagent for 45 min and stained with live/dead reagent, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-Foxp3. The population of activated caspase-3+ Treg cells of all Foxp3+ Treg cells was determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown (left panel). Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of the experiments are shown (right panels). Experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

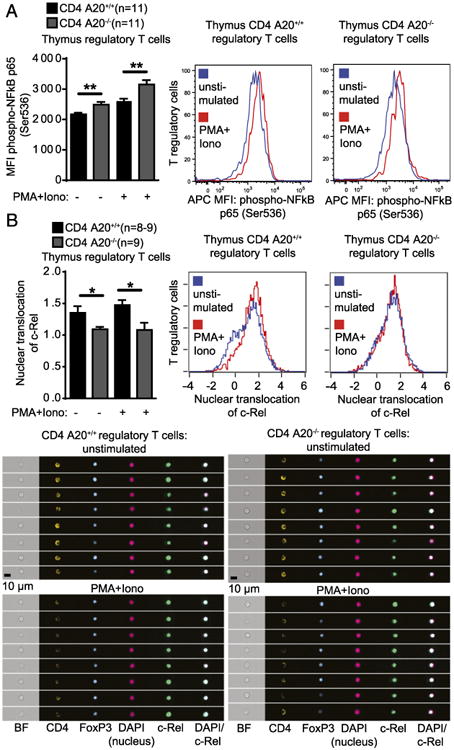

Thymic A20-deficient Treg cells show enhanced RelA phosphorylation and reduced nuclear translocation of c-Rel

Because A20 was shown to be a central negative regulator of NF-κB activity in several cell types, we then asked whether deleting A20 in CD4+ T cells led to increased NF-κB activity in those cells. In fact, both Foxp3+ CD4SP thymic Treg cells and Foxp3− CD4SP thymic T cells displayed increased NF-κB activity as measured by p65 phosphorylation intensity after stimulation. In Foxp3+ CD4SP thymic Treg cells, p65 phosphorylation intensity was already increased at baseline without stimulation, which was also the case for Foxp3− CD4SP thymic T cells (Fig. 6A, Supplemental Fig. 4A). Because the NF-κB transcription factor c-Rel was shown to play a pronounced role in thymic Treg cell development (17), we assessed c-Rel translocation to the nucleus of thymic Treg cells on single-cell levels. Although c-Rel translocation was somewhat decreased in thymic Foxp3+ CD4SP A20−/− Treg cells compared with A20+/+ Treg cells, thymic Treg cells were characterized by a high degree of nuclear c-Rel translocation in both genotypes even in the absence of stimulation (Fig. 6B). Foxp3− CD4SP thymic A20−/− T cells also showed a trend for reduced nuclear c-Rel translocation (Supplemental Fig. 4B).

Figure 6.

Thymic A20-deficient Treg cells show enhanced RelA activation and reduced nuclear trans-location of c-Rel. (A) Thymocytes of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were left unstimulated or stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (Iono) for 30 min and stained with live/dead reagent, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-Foxp3, and anti–phospho-NF-κB p65. Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of phospho–NF-κB of CD4+ CD8− (CD4SP) Foxp3+ Treg cells was determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of two independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted (left panel). Representative histograms showing fluorescence intensity of phospho–NF-κB p65 of Treg cells are shown (right panels). (B) CD8+ cell MACS-depleted thymocytes of CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were left unstimulated or stimulated with PMA and Iono for 30 min; stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-Foxp3, anti–c-Rel, and DAPI; and acquired on an imaging flow cytometer. Nuclear translocation of CD4SP Foxp3+ Treg cells was quantified based on the similarity score of c-Rel and nuclear image intensities. Pooled data of two independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted (left panel). Representative histograms show the nuclear translocation score of unstimulated and stimulated CD4SP Foxp3+ Treg cell populations (right panels). Exemplary images are representative for the mean nuclear translocation score of indicated populations (lower panels). Experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

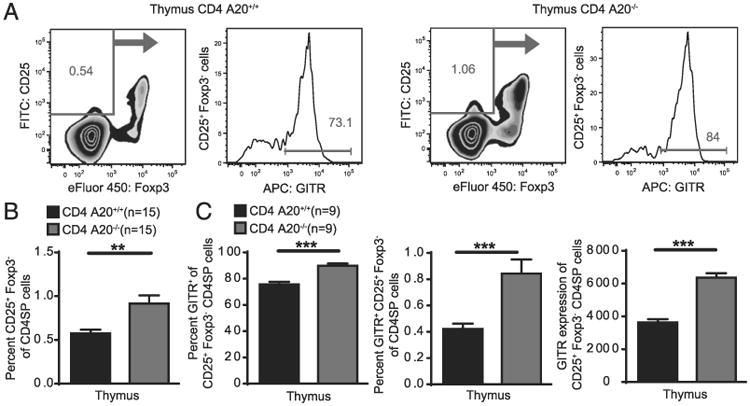

A20 limits development of thymic Treg cell progenitors

Considering the observations that NF-κB transcription factors and especially c-Rel modulates various steps of Treg cell development including the generation of thymic Treg cell progenitors before Foxp3 expression (48), we examined thymic Treg precursors in the absence of A20. Mice with A20−/− T cells exhibited increased frequencies of CD25+ Foxp3− CD4SP thymocytes, revealing an enhanced Treg cell precursor compartment (Fig. 7A, 7B). Furthermore, we observed an increased fraction of GITR+ cells within this population, resulting in a ∼2-fold increased Treg cell progenitor (CD4SP CD25+ GITR+ Foxp3−) compartment (Fig. 7C). In addition, GITR expression of the CD25+ Foxp3− CD4SP A20−/− thymic Treg precursors was enhanced compared with Foxp3-expressing Treg cells (Fig. 7C, Supplemental Fig. 4C). This population increase at the Treg precursor differentiation stage in CD4 A20−/− mice suggests that early intrinsic mechanisms preceding Foxp3 expression are responsible for the developmental advantage of the CD4 A20−/− versus CD4 A20+/+ Treg cell population.

Figure 7.

A20 limits development of thymic Treg cell progenitors. (A) Thymocytes of adult CD4 A20+/+ and CD4 A20−/− mice were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-Foxp3, anti-GITR, and live/dead reagent. The population of CD4+ CD8− CD25+ Foxp3− GITR+ live cells was determined by flow cytometry. Gating strategy and representative FACS plots of cells that were previously gated on single, live CD4+ CD8− (CD4SP) thymocytes are depicted. (B) Frequencies of CD25+ Foxp3− of CD4SP live cells were determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (C) Frequencies of GITR+ cells of CD25+ Foxp3− CD4SP cells (left panel), frequencies of GITR+ CD25+ Foxp3− of CD4SP live cells (middle panel), and mean GITR expression of CD25+ Foxp3− CD4SP live cells (right panel) were determined by flow cytometry. Pooled data of two independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

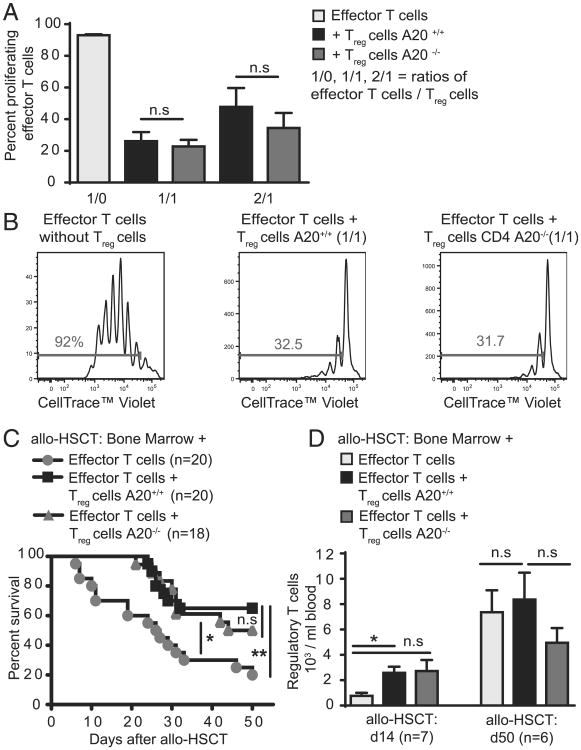

A20-deficient Treg cells are functional

Having demonstrated that deleting A20 in CD4 T cells induces a specific Treg cell population increase, we next analyzed whether A20-deficient Treg cells are functional. In vitro, we found that CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells purified from CD4 A20+/+ or CD4 A20−/− mice both efficiently suppressed proliferation of A20+/+ T effector cells to a similar extent (Fig. 8A, 8B). To analyze Treg cell function in vivo, we used a model of major mismatch allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), in which the hematopoietic system of recipient mice is eradicated by TBI and then reconstituted with BM and T cells from allogeneic donors. Lethal effects of acute GVHD, mediated by allogeneic effector T cells, can be significantly reduced in this model by cotransplantation of Treg cells (49). Survival of mice that received either A20+/+ or A20−/− Treg cells together with WT donor BM and T cells was similarly increased in both groups compared with controls that did not receive additional Treg cells (Fig. 8C). This was attributable to the function of individual Treg cells and not due to numerical changes throughout the course of the experiment, because the absolute number of Treg cells in animals cotransplanted with effector and Treg cells was not significantly different when CD4 A20+/+ or CD4 A20−/− Treg cells were used (Fig. 8D). Together, our data show that loss of A20 does not impair the suppressive functions of Treg cells.

Figure 8.

A20-deficient Treg cells are functional. (A) MACS-sorted A20+/+ or A20−/− CD4+ CD25− T effector cells were labeled with a cell tracer dye (CellTrace Violet) and cultured together with CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 and irradiated APCs at different ratios. Numbers of proliferating effector T (Teff) cells were determined on day 4. Pooled data of two independent experiments are shown. (B) Gating strategy and representative histograms of labeled Teff cells of one representative experiment described in (A). (C) Survival curve of allo-HSCT recipient mice (BALB/c) after 9 Gy TBI + 5 × 106 T cell–depleted BM cells + 2 × 105 CD4+ CD25− + 2 × 105 CD8+ T cells (C57BL/6) and either 6 × 105 A20+/+ or A20−/− CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells (C57BL/6). Pooled data of three independent experiments are shown. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. (D) Number of donor-derived Treg cells in the blood of allo-HSCT recipient mice that were transplanted as described in (C). Blood was taken at indicated time points. The experiment was performed once. Animal numbers per group (n) are depicted. Survival was analyzed using the log-rank test. Other experiments were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Discussion

NF-κB activation modulates Treg cell development through various mechanisms, including induction of Foxp3 transcription in the thymus (16). We hypothesized that enhanced NF-κB activity in CD4+ T cells, as in the absence of its negative regulator A20, might have an impact on the development, maintenance, and functionality of Treg cells. We observed that mice lacking A20 specifically in CD4+ T cells had increased numbers of CD4+ Treg cells in spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus.

Because the increase in Treg cells, which are known to arise in the thymus very early after birth (50), was already detectable in 12-d-old mice and could not be explained by enhanced iTreg cell differentiation or expansion, we hypothesized that a cell-intrinsic effect during thymic Treg cell generation may account for Treg cell expansion in CD4 A20−/− mice. In fact, competitive engraftment experiments in chimeras with BM from CD4 A20−/− mice equally mixed with BM from WT mice established a significantly larger Treg cell compartment compared with chimeras with BM from CD4 A20+/+ mice equally mixed with BM from additional WT mice. We observed that the majority of Treg cells contributing to the enlarged Treg cell compartment were derived from A20−/− BM. This is in line with previous findings that increased NF-κB activity, in particular of c-Rel (17), leads to increased proportions and absolute numbers of thymic Foxp3+ natural Treg cells (16).

Complementary to our data with CD4 A20−/− BM chimeras, less Treg cells were generated from c-Rel–deficient BM than from WT BM in a competitive setting (18). The differentiation of naive T cells toward iTreg cells was regulated by c-Rel independently of IL-2 (18). Remarkably, in our setting, CD4 A20−/− Treg cells were less responsive to IL-2 in vitro. IL-2 is known to maintain Treg cells by preventing Foxp3-induced apoptosis (46) and through regulation of MCL-1 that is essential for Treg cell survival (45). In this context, we observed that A20−/− Treg cells were less affected by both the presence and absence of IL-2. Although the Treg compartment originating from CD4 A20−/− BM was expanded in vivo, A20−/− cells displayed a reduced response to classical Treg cell proliferative or differentiating factors such as IL-2 and TGF-β in vitro. In vivo, neither proliferation nor apoptosis was significantly affected in A20-deficient Treg cells, contrary to A20−/− effector T cells, which showed increased rates of apoptosis. This is in line with previous findings that show that A20 regulates cell death and survival of effector T cells (34, 35, 38). At the current stage, the molecular mechanisms to explain the relative insensitivity of A20−/− Treg cells toward IL-2 remain unclear. Intrinsic effects of differential NF-κB regulation in CD4 A20−/− mice rather than a higher cell turnover are the most likely explanation for Treg expansion in these mice in vivo. In this context, we found that the activity of the NF-κB subunit RelA (p65) was enhanced in Foxp3+ thymic Treg cells in the absence of A20. In contrast, A20−/− thymic Treg cells showed reduced nuclear translocation of the NF-κB subunit c-Rel. Because NF-κB signaling was shown to modulate multiple steps of Treg cell development in the thymus (48), we hypothesize that A20 influences the thymic development of natural Treg cells through modulation of NF-κB activation in Treg cell progenitors. In line with this hypothesis, we discovered that the population increase in CD4 A20−/− compared with CD4 A20+/+ mice was not restricted to the Foxp3+ thymic Treg cell compartment, but was also comparably elevated in CD4SP CD25+ GITR+ Foxp3− thymic Treg cell progenitors. Furthermore, we observed elevated GITR expression levels of CD4SP CD25+ Foxp3− thymic Treg cell precursors. In this regard, it was shown recently that costimulation of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily molecules, such as GITR, connects TCR signal strength to thymic differentiation of Treg cells (51). Further studies are needed to examine a possible role of A20 and NF-κB activation in this context and to define how A20 restrains thymic Treg cell progenitor generation molecularly. In addition, whether deleting A20 at other time points of Treg cell generation that coincide with CD4 expression would entail different outcomes remains to be determined.

Our finding that A20 restricts thymic Treg cell generation is consistent with previous data for CYLD, another negative regulator of NF-κB, which, as A20, was shown to remove nonproteolytic K63-linked polyubiquitin chains from signaling molecules in the TCR pathway. CYLD deficiency promotes constitutive NF-κB activity in thymocytes and peripheral T cells, and is associated with enhanced Treg cell frequencies (52, 53). Interestingly, CD25 expression is decreased in CYLD-deficient Treg cells (52), which is in line with our findings revealing lower expression levels of CD25 in A20−/− CD4+ Foxp3+ CD25+ Treg cells. However, CYLD-deficient Treg cells were shown to be less functional, failing to inhibit colitis in an adoptive transfer colitis model (52). This is in contrast with our data demonstrating that increased natural A20−/− Treg cells are functional to suppress allogeneic effector T cell toxicity in a preclinical model of acute GVHD. Perhaps differential NF-κB regulation may explain2 those discrepancies, because A20 terminates NF-κB signaling (19), whereas CYLD prevents spontaneous NF-κB activation (54).

In summary, we propose that A20 holds the thymic development of natural Treg cells in check and thereby contributes to fine-tuning the CD4+ T cell response. Given that A20 inhibits T effector cell death in CD4+ T cells, unleashing T effector cell–mediated inflammatory activity, our data complement the picture of A20 as a potent regulator of T cell–mediated inflammation, inducing T effector cell survival while reducing Treg cell generation. In light of the largely anti-inflammatory effects that have been attributed to A20 in many cell types, this proinflammatory aspect of A20 physiology in effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells is particularly important because it may contribute to a change of perception of the functions of A20 as a negative regulator of NF-κB in the context of inflammation. Whether targeted modulation of A20 activity may allow to promote Treg cell–mediated immune tolerance or, alternatively, favorable T cell immunity is a question of translational relevance that needs to be addressed in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung Grants 2015_A06 (to S.S.) and 2012_A61 (to H.P.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant PO 1575/3-1 (to H.P.), German Cancer Aid Grant 111620 (to H.P. and S.H.), the European Hematology Association (to H.P.), the TUM Medical Graduate Center (to V.O.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1054 Project A02 to M.K., C.D., and M.S.-S.), and a fellowship of the Kommission für Klinische Forschung von Technische Universität Zentrum Medizin (to S.S.).

Abbreviations used in this article

- allo-HSCT

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- BM

bone marrow

- γc

common γ-chain

- CD4SP

CD4 single-positive

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- iTreg

induced Treg

- TBI

total body irradiation

- Treg

regulatory T

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

J.C.F. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, introduced V.O. into laboratory techniques, and wrote the manuscript; V.O. performed, analyzed, and helped to design experiments; M.K. helped to design, performed, and analyzed experiments; M.R. performed and analyzed experiments; C.D. and M.S. helped to perform experiments; C.D. and M.S.-S. provided critical input; S.H., R.B., G.v.L., X.C.L., and C.P. provided further help; S.S. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments; T.H., S.S., and H.P. wrote the manuscript and guided the study.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh CS, Lee HM, Lio CW. Selection of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:157–167. doi: 10.1038/nri3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huehn J, Polansky JK, Hamann A. Epigenetic control of FOXP3 expression: the key to a stable regulatory T-cell lineage? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:83–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thome M, Charton JE, Pelzer C, Hailfinger S. Antigen receptor signaling to NF-kappaB via CARMA1, BCL10, and MALT1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003004. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J, So T, Croft M. Activation of NF-kappaB1 by OX40 contributes to antigen-driven T cell expansion and survival. J Immunol. 2008;180:7240–7248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medoff BD, Sandall BP, Landry A, Nagahama K, Mizoguchi A, Luster AD, Xavier RJ. Differential requirement for CARMA1 in agonist-selected T-cell development. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:78–84. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Manicassamy S, Vasu C, Kumar A, Shang W, Sun Z. Differential requirement of PKC-theta in the development and function of natural regulatory T cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;46:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.08.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt-Supprian M, Tian J, Grant EP, Pasparakis M, Maehr R, Ovaa H, Ploegh HL, Coyle AJ, Rajewsky K. Differential dependence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory and natural killer-like T cells on signals leading to NF-kappaB activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4566–4571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt-Supprian M, Courtois G, Tian J, Coyle AJ, Israël A, Rajewsky K, Pasparakis M. Mature T cells depend on signaling through the IKK complex. Immunity. 2003;19:377–389. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan YY, Chi H, Xie M, Schneider MD, Flavell RA. The kinase TAK1 integrates antigen and cytokine receptor signaling for T cell development, survival and function. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:851–858. doi: 10.1038/ni1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes MJ, Krebs P, Harris N, Eidenschenk C, Gonzalez-Quintial R, Arnold CN, Crozat K, Sovath S, Moresco EM, Theofilopoulos AN, et al. Commitment to the regulatory T cell lineage requires CARMA1 in the thymus but not in the periphery. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e51. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallabhapurapu S, Powolny-Budnicka I, Riemann M, Schmid RM, Paxian S, Pfeffer K, Körner H, Weih F. Rel/NF-kappaB family member RelA regulates NK1.1- to NK1.1+ transition as well as IL-15-induced expansion of NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3508–3519. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellavia D, Campese AF, Alesse E, Vacca A, Felli MP, Balestri A, Stoppacciaro A, Tiveron C, Tatangelo L, Giovarelli M, et al. Constitutive activation of NF-kappaB and T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Notch3 transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:3337–3348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long M, Park SG, Strickland I, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Nuclear factor-kappaB modulates regulatory T cell development by directly regulating expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;31:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isomura I, Palmer S, Grumont RJ, Bunting K, Hoyne G, Wilkinson N, Banerjee A, Proietto A, Gugasyan R, Wu L, et al. c-Rel is required for the development of thymic Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3001–3014. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091411. Published erratum appears in 2010 J. Exp. Med. 207: 899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruan Q, Kameswaran V, Tone Y, Li L, Liou HC, Greene MI, Tone M, Chen YH. Development of Foxp3(+) regulatory t cells is driven by the c-Rel enhanceosome. Immunity. 2009;31:932–940. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catrysse L, Vereecke L, Beyaert R, van Loo G. A20 in inflammation and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee EG, Boone DL, Chai S, Libby SL, Chien M, Lodolce JP, Ma A. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science. 2000;289:2350–2354. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catrysse L, Farhang Ghahremani M, Vereecke L, Youssef SA, Mc Guire C, Sze M, Weber A, Heikenwalder M, de Bruin A, Beyaert R, van Loo G. A20 prevents chronic liver inflammation and cancer by protecting hepatocytes from death. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2250. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu Y, Vahl JC, Kumar D, Heger K, Bertossi A, Wójtowicz E, Soberon V, Schenten D, Mack B, Reutelshöfer M, et al. B cells lacking the tumor suppressor TNFAIP3/A20 display impaired differentiation and hyperactivation and cause inflammation and autoimmunity in aged mice. Blood. 2011;117:2227–2236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-306019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavares RM, Turer EE, Liu CL, Advincula R, Scapini P, Rhee L, Barrera J, Lowell CA, Utz PJ, Malynn BA, Ma A. The ubiquitin modifying enzyme A20 restricts B cell survival and prevents autoimmunity. Immunity. 2010;33:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kool M, van Loo G, Waelput W, De Prijck S, Muskens F, Sze M, van Praet J, Branco-Madeira F, Janssens S, Reizis B, et al. The ubiquitin-editing protein A20 prevents dendritic cell activation, recognition of apoptotic cells, and systemic autoimmunity. Immunity. 2011;35:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vereecke L, Sze M, Mc Guire C, Rogiers B, Chu Y, Schmidt-Supprian M, Pasparakis M, Beyaert R, van Loo G. Enterocyte-specific A20 deficiency sensitizes to tumor necrosis factor-induced toxicity and experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1513–1523. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musone SL, Taylor KE, Lu TT, Nititham J, Ferreira RC, Ortmann W, Shifrin N, Petri MA, Kamboh MI, Manzi S, et al. Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1062–1064. doi: 10.1038/ng.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Parkin M, Gates C, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matmati M, Jacques P, Maelfait J, Verheugen E, Kool M, Sze M, Geboes L, Louagie E, Mc Guire C, Vereecke L, et al. A20 (TNFAIP3) deficiency in myeloid cells triggers erosive polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:908–912. doi: 10.1038/ng.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitz R, Hansmann ML, Bohle V, Martin-Subero JI, Hartmann S, Mechtersheimer G, Klapper W, Vater I, Giefing M, Gesk S, et al. TNFAIP3 (A20) is a tumor suppressor gene in Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2009;206:981–989. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Düwel M, Welteke V, Oeckinghaus A, Baens M, Kloo B, Ferch U, Darnay BG, Ruland J, Marynen P, Krappmann D. A20 negatively regulates T cell receptor signaling to NF-kappaB by cleaving Malt1 ubiquitin chains. J Immunol. 2009;182:7718–7728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coornaert B, Baens M, Heyninck K, Bekaert T, Haegman M, Staal J, Sun L, Chen ZJ, Marynen P, Beyaert R. T cell antigen receptor stimulation induces MALT1 paracaspase-mediated cleavage of the NF-kappaB inhibitor A20. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:263–271. doi: 10.1038/ni1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giordano M, Roncagalli R, Bourdely P, Chasson L, Buferne M, Yamasaki S, Beyaert R, van Loo G, Auphan-Anezin N, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Verdeil G. The tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20) imposes a brake on antitumor activity of CD8 T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11115–11120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406259111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onizawa M, Oshima S, Schulze-Topphoff U, Oses-Prieto JA, Lu T, Tavares R, Prodhomme T, Duong B, Whang MI, Advincula R, et al. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 restricts ubiquitination of the kinase RIPK3 and protects cells from necroptosis. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:618–627. doi: 10.1038/ni.3172. Published erratum appears in 2015 Nat. Immunol. 16: 785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuzawa Y, Oshima S, Takahara M, Maeyashiki C, Nemoto Y, Kobayashi M, Nibe Y, Nozaki K, Nagaishi T, Okamoto R, et al. TNFAIP3 promotes survival of CD4 T cells by restricting MTOR and promoting autophagy. Autophagy. 2015;11:1052–1062. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1055439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drennan MB, Govindarajan S, Verheugen E, Coquet JM, Staal J, McGuire C, Taghon T, Leclercq G, Beyaert R, van Loo G, et al. NKT sublineage specification and survival requires the ubiquitin-modifying enzyme TNFAIP3/A20. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1973–1981. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee PP, Fitzpatrick DR, Beard C, Jessup HK, Lehar S, Makar KW, Pérez-Melgosa M, Sweetser MT, Schlissel MS, Nguyen S, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer JC, Otten V, Steiger K, Schmickl M, Slotta-Huspenina J, Beyaert R, van Loo G, Peschel C, Poeck H, Haas T, Spoerl S. A20 deletion in T cells abrogates acute graft-versus-host disease. Eur J Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/eji.201646911. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer JC, Wintges A, Haas T, Poeck H. Assessment of mucosal integrity by quantifying neutrophil granulocyte influx in murine models of acute intestinal injury. Cell Immunol. 2017;316:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer JC, Bscheider M, Eisenkolb G, Lin CC, Wintges A, Otten V, Lindemans CA, Heidegger S, Rudelius M, Monette S, et al. RIG-I/MAVS and STING signaling promote gut integrity during irradiation- and immune-mediated tissue injury. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaag2513. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schurgers E, Kelchtermans H, Mitera T, Geboes L, Matthys P. Discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivo effects of murine mesenchymal stem cells on T-cell proliferation and collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R31. doi: 10.1186/ar2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George TC, Fanning SL, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Medeiros RB, Highfill S, Shimizu Y, Hall BE, Frost K, Basiji D, Ortyn WE, et al. Quantitative measurement of nuclear translocation events using similarity analysis of multi-spectral cellular images obtained in flow. J Immunol Methods. 2006;311:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.01.018. Published erratum appears in 2009 J. Immunol. Methods 344: 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas DC, Mellanby RJ, Phillips JM, Cooke A. An early age-related increase in the frequency of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells in BDC2.5NOD mice. Immunology. 2007;121:565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang CH, Tian L, Ling GS, Trendell-Smith NJ, Ma L, Lo CK, Stott DI, Liew FY, Huang FP. Immunological mechanisms and clinical implications of regulatory T cell deficiency in a systemic autoimmune disorder: roles of IL-2 versus IL-15. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1664–1676. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierson W, Cauwe B, Policheni A, Schlenner SM, Franckaert D, Berges J, Humblet-Baron S, Schönefeldt S, Herold MJ, Hildeman D, et al. Antiapoptotic Mcl-1 is critical for the survival and niche-filling capacity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ni.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker HH, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984;133:1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulford TS, Ellis D, Gerondakis S. Understanding the roles of the NF-κB pathway in regulatory T cell development, differentiation and function. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;136:57–67. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Drago K, Fathman CG, Strober S, Negrin RS. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fontenot JD, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Developmental regulation of Foxp3 expression during ontogeny. J Exp Med. 2005;202:901–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahmud SA, Manlove LS, Schmitz HM, Xing Y, Wang Y, Owen DL, Schenkel JM, Boomer JS, Green JM, Yagita H, et al. Costimulation via the tumor-necrosis factor receptor superfamily couples TCR signal strength to the thymic differentiation of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:473–481. doi: 10.1038/ni.2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reissig S, Hövelmeyer N, Weigmann B, Nikolaev A, Kalt B, Wunderlich TF, Hahn M, Neurath MF, Waisman A. The tumor suppressor CYLD controls the function of murine regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:4770–4776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reiley WW, Jin W, Lee AJ, Wright A, Wu X, Tewalt EF, Leonard TO, Norbury CC, Fitzpatrick L, Zhang M, Sun SC. Deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD negatively regulates the ubiquitin-dependent kinase Tak1 and prevents abnormal T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1475–1485. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiley W, Zhang M, Wu X, Granger E, Sun SC. Regulation of the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD by IkappaB kinase gamma-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3886–3895. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.3886-3895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.