Abstract

We have purified GST-fused recombinant mouse Dnmt3a and three isoforms of mouse Dnmt3b to near homogeneity. Dnmt3b3, an isoform of Dnmt3b, did not have DNA methylation activity. Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 or Dnmt3b2 showed similar activity toward poly(dG-dC)-poly(dG-dC) for measuring de novo methylation activity, and toward poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) for measuring total activity. This indicates that the enzymes are de novo-type DNA methyltransferases. The enzyme activity was inhibited by NaCl or KCl at concentrations >100 mM. The kinetic parameter, KmAdoMet, for Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 was 0.4, 1.2 and 0.9 µM when poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) was used, and 0.3, 1.2 and 0.8 µM when poly(dG-dC)-poly(dG-dC) was used, respectively. The KmDNA values for Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 were 2.7, 1.3 and 1.5 µM when poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) was used, and 3.5, 1.0 and 0.9 µM when poly(dG-dC)-poly(dG-dC) was used, respectively. For the methylation specificity, Dnmt3a significantly methylated CpG >> CpA. On the other hand, Dnmt3b1 methylated CpG > CpT ≥ CpA. Immuno-purified Dnmt3a, Myc-tagged and overexpressed in HEK 293T cells, methylated CpG >> CpA > CpT. Neither Dnmt3a nor Dnmt3b1 methylated the first cytosine of CpC.

INTRODUCTION

In vertebrates, the fifth position of cytosine residues in CpG sequences in genomic DNA is often methylated (1). Dynamic regulation of DNA methylation is known to contribute to physiological or pathological phenomena such as tissue-specific gene expression (2–4), genomic imprinting (5), X chromosome inactivation (6) and carcinogenesis (7). In vertebrates, two types of DNA methyltransferase activity have been reported, i.e. de novo- and maintenance-type DNA methyltransferase activities. In mouse, de novo-type DNA methylation activity creates tissue-specific methylation patterns at the implantation stage of embryogenesis (8), and maintenance-type activity ensures clonal transmission of lineage-specific methylation patterns during replication. Dnmt1 is responsible for the latter activity. Recently, two DNA methyltransferases, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, were identified (9), and this Dnmt3 family is expected to be responsible for the creation of methylation patterns at an early stage of embryogenesis (10,11). A mutation in DNMT3b gene, a human homolog of Dnmt3b, has been proven to be the cause of ICF syndrome (10,12,13), a rare autosomal recessive disease that triggers chromosomal instability due to hypomethylation of the satellite 2 and 3 regions of chromosomes 1, 9 and 16 (10,14). Although the Dnmt3 family is capable of creating a methylation pattern in vivo (15), its ability to create a methylation pattern in vitro has only been reported for a crude extract overexpressed in insect cells (9).

It has been reported that non-CpG methylation occurs in integrated adenovirus DNA (16), an integrated plasmid (17), an L1 element from embryonic fibroblasts (18), and embryonic stem cells (19). Using embryonic stem cells that lack Dnmt1, Ramsahoye et al. showed that a DNA methyltransferase other than Dnmt1, possibly Dnmt3a, is responsible for the non-CpG methylation (19).

To address the questions of whether (i) Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are real de novo methylases, (ii) the three isoforms of Dnmt3b, i.e. 3b1, 3b2 and 3b3, exhibit an enzymatic difference, and (iii) Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b can exhibit non-CpG methylation activity in vitro, we have purified recombinant Dnmt3a and all three isoforms of Dnmt3b. Using the purified proteins, we have shown that Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b exhibit similar de novo methylation activity with similar kinetic parameters, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 show almost identical enzymatic properties, and Dnmt3b3 has no DNA methylation activity. Interestingly, both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b exhibit non-CpG methylating activity. In particular, Dnmt3b appears to have the ability to methylate CpT and CpA more than does Dnmt3a.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The coding sequences of mouse Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b1, 2 and 3 cDNAs were subcloned into the BamHI site of the pGEX vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK). The ATG coding initiation methionine was directly connected to the BamHI site in the pGEX vector without any spacer sequence. For Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b1, the cDNA was also subcloned into the pCS2+MT vector, which was kindly provided by Drs H. B. Sucic and D. Turner (University of Michigan, USA) harboring the Myc-tag sequence in the 5′ site.

Purification of GST-fused Dnmt3

Dnmt3-harboring plasmids were expressed in BL21(DE3) at 20°C. After the OD at 650 nm reached 0.6, 0.5 mM IPTG was added to the culture medium, followed by further culturing for 18 h. All the purification steps thereafter were performed on ice or at 4°C. Harvested bacteria were suspended in 5 vol of solubilization (S) buffer [0.33 M NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100, 1/20 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Nakarai Tesque, Japan) in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]. The cell suspension was sonicated and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant fraction recovered. For Dnmt3a, the solubilized fraction was loaded onto a DEAE–Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column and the unbound fraction was collected. For Dnmt3b, the solubilized fraction was precipitated and recovered by 20–30% saturation with ammonium sulfate, and the precipitate was dissolved in 5 ml of S buffer. Samples were loaded onto glutathione–Sepharose, washed with 10 bed vol of S buffer, and then eluted with 4 bed vol of elution (E) buffer [0.33 M NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100, 1/200 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail, 10 mM glutathione, reduced form, 1 mM DTT in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0]. The eluted fractions were collected in tubes already containing a 1/10 vol of 1 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, and quickly mixed. The main fractions were pooled and loaded onto a Superdex 200 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column equilibrated with E buffer minus reduced form glutathione. The Dnmt3 at each step was checked by SDS–PAGE on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel (20), and purity was monitored by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (CBB) staining.

Preparation of Myc-tagged Dnmt3

Myc-tagged Dnmt3 was expressed in HEK 293T cells. Transfection with lipofectoamine (Gibco BRL, MD) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells transfected with the plasmid were washed with PBS, and then solubilized with 2 M NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100, 1/50 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4. Dnmt3 thus extracted was immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10)-coupled Sepharose at 4°C for 4 h. The matrix was washed with the extraction buffer and then used for the methylation reaction.

Antibodies

Antisera reacted with mouse Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b were raised against maltose binding protein fusion proteins, and an antiserum reacted with glutathione S-transferase (GST) was raised against GST. The antibodies raised in rabbits were immunoselected using GST fusion protein- or GST-coupled Sepharose as affinity matrices. To this end, a DNA [232 (SmaI)–701 (SmaI), encoding amino acids 7–162] of mouse Dnmt3a (accesion no. AF068625) and a DNA [1–662 (SalI), encoding amino acids 1–181] of mouse Dnmt3b1 (accession no. AF068626) were ligated into pMAL-c2 (NEB, MA) and pGEX vectors, and expressed in BL21(DE3) in the presence of IPTG. GST and the fusion proteins were purified with glutathione–Sepharose or amylose resin according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b and GST bands electrophoresed on SDS–PAGE were immunodetected as described elsewhere (21).

DNA methylation activity

Poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC) (dIdC) and poly(dG-dC)-poly(dG-dC) (dGdC) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used as the methyl acceptors for total and de novo methylation activity measurements, respectively (22,23). The methylation activity was measured in 25 µl of reaction (R) buffer (5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 26 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4) containing 50 ng (∼0.5 pmol) of the purified enzyme, 0.1 µg DNA, which was ∼150 pmol CpI or CpG when 1 mol double-stranded DNA with 1 CpI or CpG site was calculated to be 2 mol, and 134 pmol [3H]S-adenosyl-l-methione (AdoMet) (15 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), unless otherwise stated. After the reaction, the mixtures were incubated with 0.1 µg of proteinase K (Nakalai Tesque, Japan) at 50°C for 20 min, and then the radioactivity was measured as described previously (21). Protein concentrations were determined by quantifying the CBB-stained SDS–PAGE gels with an image analyzer (MCID; Imaging Research, Canada), using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The specific activities were expressed as moles of transferred methyl group per hour per mole of each Dnmt3 (mol/h/mol Dnmt3).

Determination of the cytosine methylation

As a methyl acceptor, the HindIII fragment of the myoD gene (accession no. X61655) subcloned into pUC19 (24) was used. AdoMet (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) was purified on a Sep-Pack Plus C18 column (Waters, Japan) before use.

For the methylation by GST-fused enzymes, the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h with 0.1 µg pUC-myoD, 3–5 µg Dnmt3 protein, 100 µM AdoMet in 500 µl of R buffer. For the Myc-tagged Dnmt3 bound to Sepharose, the reaction mixture contained 1 µg pUC-myoD, 5 µg Dnmt3 protein and 160 µM AdoMet in 200 µl of R buffer, and was then incubated at 37°C for 3 h under agitation. After the reaction, the plasmid was recovered, and the methylation reaction was repeated twice more with fresh enzyme-coupled Sepharose and AdoMet.

The sodium bisulfite reaction was performed basically as described elsewhere (25) with a slight modification. Briefly, HindIII-digested plasmids were treated with 0.3 M NaOH for 30 min and then incubated in a mixture comprising 2.9 M Na2S2O5 and 100 mM hydroquinone, with the pH adjusted to 5. The reaction mixture was incubated for a total of 5 h at 55°C with 1 min incubation at 95°C every 1 h. The recovered DNA was alkaline-treated and then used for PCR with three sets of primers designed to amplify intron2 of the myoD gene as follows: upperF, GGTGGATTTAGGAGGATGAGTAATGGAG; upperR, CCCCAAATACTAAAAACCAACCACACAC; lower1F: GGTTTTAGGATTGGGTTAGTTTTAGGTGTTAGG; lower1R, CCCTCATACCTAAATACTCCTAACATCTAACA; lower2F, GTGTTAGATGTTAGGAGTATTTAGGTATGAGGG; lower2R, CACCTAAACCACTACCCCCAAACC. Primer set upperF and upperR amplifies the upper strand of modified intron2, and primer sets lower1F and lower1R, and lower2F and lower2R amplify the lower strand of intron2. The amplification reaction comprised 35 cycles of incubation of the reaction mixture for denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The amplified fragment was subcloned into the SmaI site of pUC19 and the modified nucleotides were determined by the dideoxy method (26).

RESULTS

Expression and purification of Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1, Dnmt3b2 and Dnmt3b3 in Escherichia coli

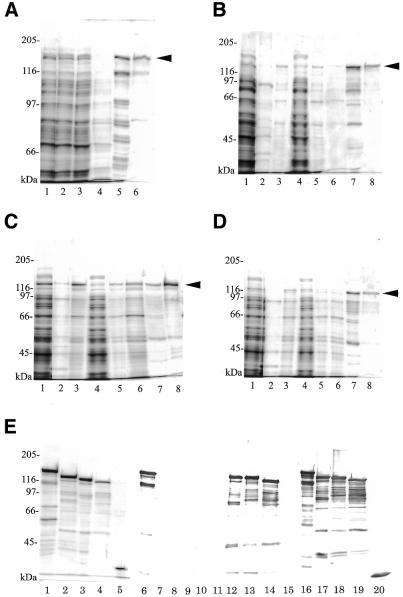

Each Dnmt3 was expressed as a fusion protein with GST (GST-Dnmt3) in the pGEX vector (Fig. 1), and then expressed in E.coli as described in the Materials and Methods. The fractions at each purification step were electrophoresed and stained (Fig. 2). The Dnmt3a expressed was purified with DEAE–Sepharose (Fig. 2A, lane 2), glutathione–Sepharose (lane 5) and Superdex 200 (lane 6). Expressed Dnmt3b1, 3b2, and 3b3 were fractionated with ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2B, C and D, lanes 3), glutathione–Sepharose (lanes 7) and Superdex 200 (lanes 8). The apparent molecular weights of the GST-fused Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1, Dnmt3b2 and Dnmt3b3 were 130, 120, 115 and 110 kDa, as calculated by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2). Considering the size of GST (26 kDa), and the calculated molecular weights of Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1, Dnmt3b2 and Dnmt3b3 are 102, 97, 95 and 88 kDa, respectively (9), the major bands (indicated by arrowheads) are expected to be intact forms of the proteins. Since these bands reacted with both anti-GST and anti-Dnmt3 antibodies (Fig. 2E, lanes 6–19), all the purified Dnmt3 proteins possessed an intact N-terminal region. The final preparations were ∼80% pure, as judged on densitometry (Fig. 2E, lanes 1–4).

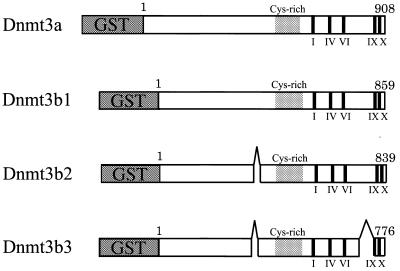

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of Dnmt3a, Dnnmt3b1, Dnmt3b2 and Dnmt3b3. The regions of the conserved motifs in the C-terminal catalytic domain (I∼X) and the Cys-rich region (Cys-rich) are indicated. Dnmt3b2 lacks amino acid residues 363–382, and Dnmt3b3 lacks amino acid residues 363–382 and 731–813, of Dnmt3b1. GST in the N-terminus of each Dnmt3 indicates the fused GST moiety. The numbers above the bars are amino acid numbers.

Figure 2.

Purification of GST-fused Dnmt3s. An aliquot of a sample obtained at each purification step was subjected to SDS–PAGE and then stained with CBB. (A) Solubilized (lane 1), DEAE–Sepharose unbound (lane 2), glutathione–Sepharose unbound (lane 3), washed (lane 4), eluted (lane 5) and Superdex 200 eluted (lane 6) fractions of GST-fused Dnmt3a. 1/20 000 (lanes 1–4), 1/1000 (lane 5) and 1/100 (lane 6) of the recovered fractions were loaded. (B–D) Solubilized (lane 1), ammonium sulfate-precipitated with 20% saturation (lane 2), 20–30%-saturation (lane 3), supernatant on 30% saturation (lane 4), glutathione–Sepharose unbound (lane 5), washed (lane 6), eluted (lane 7) and Superdex 200 eluted (lane 8) fractions of GST-fused Dnmt3b1 (B), Dnmt3b2 (C) and Dnmt3b3 (D). 1/20 000 (lanes 1–5), 1/1000 (lanes 6 and 7) and 1/100 (lane 8) of the recovered fractions were loaded. Arrowheads indicate the position of Dnmt3. (E) Purified Dnmt3a (lane 1), Dnmt3b1 (lane 2), Dnmt3b2 (lane 3), Dnmt3b3 (lane 4) and GST (lane 5) were electrophoresed in the same gel and then CBB-stained. Purified Dnmt3a (lanes 6, 11 and 16), Dnmt3b1 (lanes 7, 12 and 17), Dnmt3b2 (lanes 8, 13 and 18), Dnmt3b3 (lanes 9, 14 and 19) and GST (lanes 10, 15 and 20) were immunodetected with specific antibodies reactive with Dnmt3a (lanes 6–10), Dnmt3b (lanes 11–15) and GST (lanes 16–20), respectively. Molecular weight sizes (kDa) are indicated beside each gel.

DNA methylation activities of purified Dnmt3s

The DNA methylation activities were determined for the purified enzymes. Purified Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 showed similar activities toward dI-dC compared to those toward dG-dC when fixed amounts of AdoMet and DNA were used (Table 1). The results clearly suggest that both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b act as a de novo methylase. Interestingly, Dnmt3b3, which lacks 62 amino acid residues of the C-terminal catalytic domain of Dnmt3b1 or Dnmt3b2, showed no DNA methylation activity.

Table 1. Specific activities of GST-fused Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1, Dnmt3b2 and Dnmt3b3. The methyltransferase activity was determined for each Dnmt3.

| |

Dnmt3a |

Dnmt3b1 |

Dnmt3b2 |

Dnmt3b3 |

| dIdC |

1.07 ± 0.34a (4)b |

0.68 ± 0.10 (5) |

0.64 ± 0.08 (5) |

0.00 ± 0.00 (3) |

| dGdC | 0.52 ± 0.09 (4) | 0.43 ± 0.12 (3) | 0.40 ± 0.07 (5) | 0.00 ± 0.01 (3) |

aDNA methylation activity was expressed as mol/h/mol Dnmt3 ± standard deviation.

bThe numbers in parentheses are the numbers of DNA methylation activity measurements with different enzyme preparations.

We next examined the effect of salt on the methylation activities of each Dnmt3. As shown in Figure 3, all the Dnmt3s were inhibited in the presence of >100 mM NaCl. Even when the salt was changed to KCl, the profiles of inhibition of the enzymes were similar to those for NaCl.

Figure 3.

Effects of salts on the DNA methylation activity of Dnmt3s. The effects of KCl (A) and NaCl (B) on the DNA methylation activities [specific activity (s.a.) in mol/h/mol Dnmt3] of Dnmt3a (circles), Dnmt3b1 (open squares) and Dnmt3b2 (filled squares) was determined for methyl acceptors dIdC (left) and dGdC (right).

Kinetic parameters of purified Dnmt3s

To determine the Km for AdoMet, a methyl donor for methylation activity, we measured the activity with AdoMet concentrations of 0.15–5.4 µM. A typical titration curve for each enzyme is shown in Figure 4, and the calculated KmAdoMet and VmaxAdoMet values obtained on three measurements with different preparations of enzymes are summarized in Table 2. The KmAdoMet value for Dnmt3a was 2–4-fold smaller than those of Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2, indicating that Dnmt3a has higher affinity for AdoMet than Dnmt3bs. For the calculated VmaxAdoMet values, Dnmt3a showed a higher value than those of Dnmt3bs.

Figure 4.

Effect of the AdoMet concentration on the activity of Dnmt3s. The DNA methylation activities [specific activity (s.a.) in mol/h/mol Dnmt3] of GST-fused Dnmt3a (A), Dnmt3b1 (B) and Dnmt3b2 (C) were titrated with AdoMet (left). As methyl acceptors, dIdC (circles) and dGdC (squares) were used. A typical example for each enzyme is demonstrated. Right panels show double reciprocal plots of the respective titration curves.

Table 2. Km values of Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 for AdoMet.

| KmAdoMet (µM) | VmaxAd°Met (mol/h/mol Dnmt3) | |||

| |

dIdC |

dGdC |

dIdC |

dGdC |

| Dnmt3a |

0.4 ± 0.1a |

0.3 ± 0.0 |

1.33 ± 0.31 |

1.22 ± 0.22 |

| Dnmt3b1 |

1.2 ± 0.3 |

1.2 ± 0.3 |

1.00 ± 0.01 |

0.73 ± 0.11 |

| Dnmt3b2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.70 ± 0.17 | 0.69 ± 0.09 |

Three independent experiments similar to that shown in Figure 4 were performed using different Dnmt3 preparations.

aThe values are means ± standard deviation.

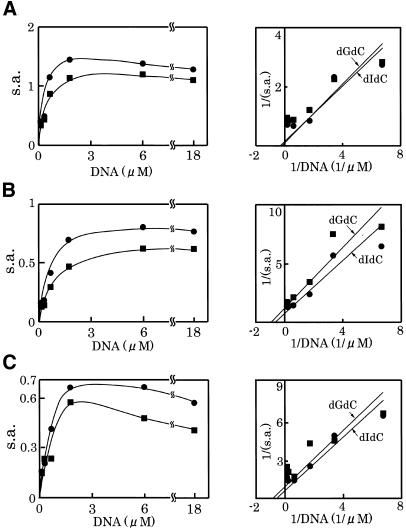

Km for DNA, a methyl acceptor, was also determined in the presence of dI-dC or dG-dC (0.15–18 µM of CpI or CpG). Typical titration profiles are shown in Figure 5, and the calculated KmDNA and VmaxDNA values obtained on three measurements with different preparations of enzymes are summarized in Table 3. The KmDNA values of each enzyme for dI-dC and dG-dC expressed as the concentrations of CpI and CpG, respectively, were similar, suggesting that Dnmt3s fulfill the conditions for a de novo methylase. On comparison of their KmDNA values, Dnmt3a showed a relatively high KmDNA value compared with Dnmt3bs, indicating that Dnmt3a may have lower affinity for DNA than Dnmt3bs. In the presence of high concentration of DNA, the activities were inhibited for both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of the DNA concentration on the activity of Dnmt3s. The DNA methylation activities [specific activity (s.a.) in mol/h/mol Dnmt3] of GST-fused Dnmt3a (A), Dnmt3b1 (B) and Dnmt3b2 (C) were titrated with dIdC (circles) or dGdC (squares). One mole double-stranded DNA with 1 CpI or CpG site was calculated to be 2 mol. A typical example for each enzyme is demonstrated. Right panels show double reciprocal plot of the respective titration curves.

Table 3. Km values of Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 for DNA.

| KmDNA (µM) | VmaxDNA (mol/h/mol Dnmt3) | |||

| |

dI-dC |

dG-dC |

dI-dC |

dG-dC |

| Dnmt3a |

2.7 ± 0.4a |

3.5 ± 1.2 |

1.7 ± 1.2 |

1.2 ± 0.7 |

| Dnmt3b1 |

1.3 ± 0.4 |

1.0 ± 0.3 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Dnmt3b2 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

Three independent experiments similar to that shown in Figure 5 were performed using different Dnmt3 preparations.

aThe values are means ± standard deviation.

Sequence specificity of the Dnmt3 methylation site

It has been postulated that Dnmt3a may methylate the cytosine residues in sequences other than CpG sequences in vivo, as judged by analysis of Dnmt1-targeted embryonic stem cells (19). To directly analyze the sequence specificity of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, we used the myoD gene as the methyl acceptor and determined the methylated sequences by the sodium bisulfite method (25). The results are summarized in Table 4. Dnmt3a methylated CpG (101.6 per 1000 CpN dinucleotides) more than other dinucleotide sequences. Under identical conditions, Dnmt3a methylated 10.4, 4.0 and 3.5 cytosine residues in CpA, CpT and CpC per 1000 CpN dinucleotides. Considering the background (experimental error) with inactive Dnmt3b3, which was 2.1, 3.1, 2.6 and 3.7 cytosine methylation for CpG, CpA, CpT and CpC per 1000 CpN dinucleotides, respectively, Dnmt3a significantly methylated CpA, although the level was very low.

Table 4. Methylation specificities of GST-fused Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b1.

| |

CpG |

CpA |

CpT |

CpC |

| Dnmt3a |

101.6 |

10.4 |

4.0 |

3.5 |

| Dnmt3b1 |

47.1 |

15.7 |

24.3 |

1.4 |

| Dnmt3b3a | 2.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

The methylation sites of the subcloned myoD gene were determined by the sodium bisulfite method. Totals of 1729, 700 and 1909 of CpN were analyzed after treatment with Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b3, respectively, and the numbers of methylated dinucleotides were determined and normalized as to 1000 CpN.

aSince Dnmt3b3 had no DNA methylation activity, the number of methylated CpN was taken as the background in this experiment.

Dnmt3b1 also methylated the CpG sequence most (47.1/1000) among the dinucleotide sequences; however, the specificity was not as strict as in the case of Dnmt3a. Dnmt3b1 methylated CpA (15.7/1000) and CpT (24.3/1000) at relatively high frequencies compared to Dnmt3a. Neither Dnmt3a nor Dnmt3b1 methylated the first cytosine in the CpC sequence. We could not find any rule for the methylation sequence as to the third nucleotide specificity (CpNpN).

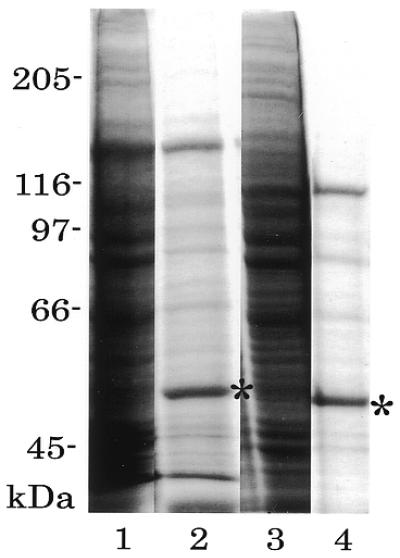

In the recombinant Dnmt3, GST was in the N-terminus. To eliminate the effect of GST, we changed the GST N-terminal tag to a Myc-tag. Myc-tagged Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b1 were expressed in HEK 293T cells under the CMV promoter and then immuno-purified with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody-coupled Sepharose. The expressed and purified Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b1 are shown in Figure 6. The enzymes bound to a matrix were used directly for the in vitro methylation reaction. The results are summarized in Table 5. Although the activity was low compared to that of the GST-fused enzymes, the dinucleotide specificity of Dnmt3a was shown to be similar to that of GST-fused Dnmt3a (Table 4). Interestingly, Myc-tagged Dnmt3a significantly methylated CpT, which was not obvious when GST-fused Dnmt3a was used. The activity of Dnmt3b1 was significantly low, only the CpG sequence specificity being significant (11.1/5000 CpN dinucleotides).

Figure 6.

Expression and immuno-purification of Dnmt3s. Myc-tagged Dnmt3a (lanes 1 and 2) and Dnmt3b1 (lanes 3 and 4) were expressed in HEK 293T cells, extracted (lanes 1 and 3), and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10)-coupled Sepharose (lanes 2 and 4). Asterisks indicate the heavy chain of 9E10. Molecular weight sizes (kDa) are indicated beside the gel.

Table 5. Methylation specificities of Myc-tagged Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b1.

| |

CpG |

CpA |

CpT |

CpC |

| Dnmt3a |

62.6 |

9.9 |

5.8 |

0.0 |

| Dnmt3b1 |

11.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

| –Dnmt3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

The methylation sites of the subcloned myoD gene were determined by the sodium bisulfite method. Totals of 6075, 4485 and 2793 of CpN were analyzed after treatment with Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1, and without Dnmt3, respectively, and the numbers of methylated dinucleotides were determined and normalized as to 5000 CpN.

DISCUSSION

De novo DNA methyltransferase activity plays a crucial role in the creation of methylation patterns in genomic DNA during embryogenesis and germ line cells. Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are the most likely candidates responsible for the de novo DNA methyltransferase activity (10). However, it has not been proven that Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs exhibit de novo DNA methylation activity in vitro using purified enzymes. In the present study, we have expressed and purified GST-fused recombinant Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs, and have shown that both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs exhibit de novo methylation activity in vitro. For Dnmt1 with dI-dC as the methyl acceptor, the activity is >10-fold higher than that toward dG-dC (27), and this property of Dnmt1 is the basis for its maintenance activity. On the other hand, although the specific activities were very low, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs showed similar activities toward both dI-dC and dG-dC, indicating that these enzymes have the ability to create a methylation pattern.

Dnmt3a and Dnmt3bs each have a catalytic domain in the C-terminal half, in which the 10 motifs conserved in DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases exist (28). Dnmt3b3 lacks 62 amino acid residues in the sequence between motifs VIII and IX, called the TRD (target recognition domain) (28) in bacterial methylases, and the part of motif IX. It was not known whether Dnmt3b3 exhibits DNA methylation activity or not. In the present study, it has been shown that Dnmt3b3 has no DNA methylation activity. As Dnmt3b3 is expressed in vivo under physiological conditions, the protein may play a role as a dominant negative factor.

Similar to human maintenance-type DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase (DNMT1) (29), interestingly, all Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b1 and Dnmt3b2 were inhibited at high concentrations of DNA (Fig. 5). Pradhan et al. proposed that DNMT1 may form a catalytically inactive complex with DNA at high concentrations of DNA through the domain other than its catalytic domain (29). The inhibitory effect of DNA on Dnmt3s could be an indication that Dnmt3s also have a DNA binding domain other than their catalytic domain.

Recently, the methylated cytosine residues in genomic DNA prepared from embryonic stem cells that lack Dnmt1 were analyzed (19). In these cells, the cytosine methylation frequencies for CpA and CpT were reported to be ∼50 and 15% of that for the CpG sequence. In our study, with Dnmt3a, after subtracting the background, CpA and CpT were methylated to ∼7 and 1%, respectively, of the methylated CpG level. On the other hand, Dnmt3b1 methylated CpA and CpT to ∼28 and 46%, respectively, of the CpG methylation level. The ability of Dnmt3a to methylate CpA and CpT itself cannot explain the levels of CpA and CpT methylation in Dnmt1-targeted embryonic stem cells (19). Dnmt3b is expected to contribute mainly to non-CpG methylation, especially of the CpT sequence. Although we added an equal amount of Dnmt3b1 as Dnmt3a protein to the methylation reaction mixture, the myc-tagged Dnmt3b1 bound to the matrix showed extremely low activity. The low activity of Dnmt3b1 could be due to the instability of Dnmt3b1 compared to Dnmt3a.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

In the course of revision, Gowher and Jeltsch published work on purified recombinant Dnmt3a reporting a similar Km for DNA and an ability for non-CpG methylation activity (30).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Program for the Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research of Japan, the Program for the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences, and Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

References

- 1.Antequera F. and Bird,A. (1993) CpG islands in DNA methylation. In Jost,J.P. and Saluz,H.P. (eds), Molecular Biology and Biological Significance. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, pp. 169–185.

- 2.Shen C.K.J. and Maniatis,T. (1980) Tissue-specific DNA methylation in a cluster of rabbit β-like globin genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 6634–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razin A. and Cedar,H. (1991) DNA methylation and gene expression. Microbiol. Rev., 55, 451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tajima S. and Suetake,I. (1998) Regulation and function of DNA methylation in vertebrates. J. Biochem., 123, 993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaenisch R. (1997) DNA methylation and imprinting: Why bother? Trends Genet., 13, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riggs A.D. and Porter,T.N. (1996) X-chromosome inactivation and epigenetic mechanisms. In Russo,V.E.A., Martinssen,R.A. and Riggs,A.D. (eds), Epigenetic Mechanisms of Gene Regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 231–248.

- 7.Laird P.W. and Jaenisch,R. (1996) The role of DNA methylation in cancer genetics and epigenetics. Annu. Rev. Genet., 30, 441–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monk M. (1990) Changes in DNA methylation during mouse embryonic development in relation to X-chromosome activity and imprinting. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 326, 299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okano M., Xie,S. and Li,E. (1998) Cloning and characterization of a family of novel mammalian DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nature Genet., 19, 219–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okano M., Bell,D.W., Haber,D.A. and Li,E. (1999) DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell, 99, 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyko F., Ramsahoye,B.H., Kashevsky,H., Tudor,M., Mastrangelo,M.A., Orr-Weaver,T.L. and Jaenisch,R. (1999) Mammalian (cytosine-5) methyltransferases cause genomic DNA methylation and lethality in Drosophila. Nature Genet., 23, 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu G.L., Bestor,T.H., Bourc’his,D., Hsieh,C.L., Tommerup,N., Bugge,M., Hulten,M., Qu,X., Russo,J.J. and Viegas-Pequignot,E. (1999) Chromosome instability and immunodeficiency syndrome caused by mutations in a DNA methyltransferase gene. Nature, 402, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen R.S., Wijmenga,C., Luo,P., Stanek,A.M., Canfield,T.K., Weemaes,C.M.R. and Gartler,S.M. (1999) The DNMT3B DNA methyltransferase gene is mutated in the ICF immunodeficiency syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14412–14417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miniou P., Jeanpierre,M., Bourc’his,D., Coutinho Barbosa,A.C., Blanquet,V. and Viegas-Pequignot,E. (1997) Alpha-satellite DNA methylation in normal individuals and in ICF patients: heterogeneous methylation of constitutive heterochromatin in adult and fetal tissues. Hum. Genet., 99, 738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh C.L. (1999) In vivo activity of murine de novo methyltransferases, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8211–8218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toth M., Müeller,U. and Doerfler,W. (1990) Establishment of a de novo methylation pattern. Transcription factor binding and deoxycytidine methylation at CpG and non-CpG sequences in an integrated adenovirus promoter. J. Mol. Biol., 214, 673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark S.J., Harrison,J. and Frommer,M. (1995) CpNpG methylation in mammalian cells. Nature Genet., 10, 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodcock D.M., Lawler,C.B., Linsenmeyer,M.E., Doherty,J.P. and Warren,W.D. (1997) Asymmetric methylation in the hypermethylated CpG promoter region of the human L1 retrotransposon. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 7810–7816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsahoye B.H., Biniszkiewicz,D., Lyko,F., Clark,V., Bird,A. and Jaenisch,R. (2000) Non-CpG methylation is prevalent in embryonic stem cells and may be mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3a. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5237–5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura H., Suetake,I. and Tajima,S. (1999) Xenopus maintenance-type DNA methyltransferase is accumulated in and translocated into germinal vesicles of oocytes. J. Biochem., 125, 1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedrali-Noy G. and Weissbach,A. (1986) Mammalian DNA methyltransferases prefer poly(dI-dC) as a substrate. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 7600–7602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeifer G.P. and Drahvosky,D. (1986) Preferential binding of DNA methyltransferase and increased de novo methylation of deoxyinosine-containing DNA. FEBS Lett., 207, 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takagi H., Tajima,S. and Asano,A. (1995) Overexpression of DNA methyltransferase in myoblast cells accelerates myotube formation. Eur. J. Biochem., 231, 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark S.J., Harrison,J., Paul,C.L. and Frommer,M. (1994) High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosine. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 2990–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tajima S., Tsuda,H., Wakabayashi,N., Asano,A., Mizuno,S. and Nishimori,K. (1995) Isolation and expression of a chicken DNA methyltransferase cDNA. J. Biochem., 117, 1050–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S., Cheng,X., Klimasauskas,S., Mi,S., Posfai,J., Roberts,R.J. and Wilson,G.G. (1994) The DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pradhan S., Bacolla,A., Wells,R.D. and Roberts,R.J. (1999) Recombinant human DNA (cytosine-5) methyltranasferase. I. Expression, purification and comparison of de novo and maintenance methylation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33002–33010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gowher H. and Jeltsch,A. (2001) Enzymatic properties of recombinant Dnmt3a DNA methyltransferase from mouse: the enzyme modifies DNA in a non-processive manner and also methylates non-CpA sites. J. Mol. Biol., 309, 1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]