Abstract

Purpose

This phase I expansion cohort study evaluated the safety and clinical activity of mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853), an antibody–drug conjugate consisting of a humanized anti–folate receptor alpha (FRα) monoclonal antibody linked to the tubulin-disrupting maytansinoid DM4, in a population of patients with FRα-positive and platinum-resistant ovarian cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer received IMGN853 at 6.0 mg/kg (adjusted ideal body weight) once every 3 weeks. Eligibility included a minimum requirement of FRα positivity by immunohistochemistry (≥ 25% of tumor cells with at least 2+ staining intensity). Adverse events, tumor response (via Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1), and progression-free survival (PFS) were determined.

Results

Forty-six patients were enrolled. Adverse events were generally mild (≤ grade 2), with diarrhea (44%), blurred vision (41%), nausea (37%), and fatigue (30%) being the most commonly observed treatment-related toxicities. Grade 3 fatigue and hypotension were reported in two patients each (4%). For all evaluable patients, the confirmed objective response rate was 26%, including one complete and 11 partial responses, and the median PFS was 4.8 months. The median duration of response was 19.1 weeks. Notably, in the subset of patients who had received three or fewer prior lines of therapy (n = 23), an objective response rate of 39%, PFS of 6.7 months, and duration of response of 19.6 weeks were observed.

Conclusion

IMGN853 exhibited a manageable safety profile and was active in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, with the strongest signals of efficacy observed in less heavily pretreated individuals. On the basis of these findings, the dose, schedule, and target population were identified for a phase III trial of IMGN853 monotherapy in patients with platinum-resistant disease.

INTRODUCTION

The American Cancer Society estimates that 22,280 women in the United States will be diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) in 2016, and 14,240 will die as a result of this disease.1 EOC, overwhelmingly diagnosed at an advanced stage, is typically initially chemotherapy sensitive, and most patients achieve remission with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Unfortunately, up to 80% of these women will relapse and require further treatment without the expectation of cure.2 Recurrent EOC is classified based on the length of time since receiving treatment with a platinum agent. Relapsed disease within 6 months of completing initial platinum therapy is classified as primary platinum resistant. Relapsed disease beyond 6 months is classified as platinum sensitive, and these patients have a high likelihood of responding to additional platinum-based therapy. However, almost all platinum-sensitive patients will eventually develop resistance, at which point they are considered to have acquired secondary platinum resistance.3-6 Both primary and acquired resistance to platinum impart a highly negative prognosis for patients with EOC, and active agents for this population represent an urgent unmet clinical need.

Folate receptor alpha (FRα) is a cell-surface transmembrane glycoprotein that facilitates the unidirectional transport of folates into cells.7 This receptor shows a restricted distribution pattern in normal tissues, with expression limited to a variety of polarized epithelia, such as those found in the choroid plexus, kidney, uterus, ovary, lung, and placenta.7,8 In contrast, aberrant FRα overexpression is characteristic of a number of epithelial tumors, including ovarian, endometrial, and non–small-cell lung cancers.9 In EOC specifically, approximately 80% of tumors constitutively express FRα10; moreover, elevated receptor expression may be a negative prognostic factor with respect to chemotherapeutic response in this malignancy.11 Thus, FRα has emerged as an attractive candidate for molecularly targeted therapeutic approaches, particularly in EOC.9,12,13

Early approaches to targeting the folate receptor evaluated small-molecule folate–cytotoxic agent conjugates (BMS-748285, vintafolide) and a nonconjugated humanized antibody (farletuzumab),9,14,15 but with disappointing clinical activity. The differential expression of FRα and its ability to internalize large molecules make this receptor well suited for antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) –based strategies that can couple the targeting and pharmacokinetic features of an antibody with the cancer-killing impact of a cytotoxic agent. In this regard, mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853) is an ADC comprising a humanized FRα-binding monoclonal antibody conjugated to the cytotoxic maytansinoid effector molecule DM4.15,16 IMGN853 binds with high affinity and specificity to FRα on the surface of tumor cells, which, upon antigen binding, promotes ADC internalization and intracellular release of DM4.17 DM4 subsequently acts as an antimitotic agent to inhibit tubulin polymerization and disrupt microtubule assembly, resulting in cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis.18 In addition, the cleavable linker design of IMGN853 allows active DM4 metabolites to diffuse into proximal tumor cells and kill them, an effect known as bystander killing.19 In preclinical studies, IMGN853 has shown robust antitumor activity in FRα-positive tumors, including in models of EOC.20 The primary objective of our study was to evaluate the safety and clinical activity of mirvetuximab soravtansine in patients with FRα-positive and platinum-resistant EOC, fallopian tube cancer, or primary peritoneal cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

Adults with histologically confirmed EOC, primary peritoneal cancer, or fallopian tube cancer who had experienced progression or relapse within 6 months of completing prior platinum-based therapy were eligible to enroll in the platinum-resistant expansion cohort. Patients had to have met the minimum requirement of FRα positivity on archival tumor samples by immunohistochemistry (IHC; ≥ 25% of tumor staining at ≥ 2+ intensity). Tumor tissues were analyzed for FRα expression at Ventana Medical Systems (Tucson, AZ), using a validated assay for sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility (per College of American Pathologists and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act guidelines). This assay uses FOLR1-2.1, a murine monoclonal antibody discovered at ImmunoGen (Waltham, MA), which recognizes FRα in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Samples were evaluated by board-certified pathologists and intensity scored semiquantitatively on a scale of 0 to 3 for negative (0), low (1), moderate (2), or high (3) expression, respectively. Patients with less than 25% expression were not eligible. Valid IHC results were obtained for 154 individuals as part of screening for the trial; 124 (81%) met enrollment eligibility. Enrolled patients had to have at least one lesion, measurable by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (version 1.1).21 Patients were also required to be ≥ 18 years of age; have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1; and have adequate hematologic, renal, and hepatic function. Key exclusion criteria included neuropathy higher than grade 1; known hypersensitivity to monoclonal antibody or maytansinoid therapy; any active or chronic corneal disorder; or a previous solid tumor malignancy with disease-free interval shorter than 3 years, except for adequately treated basal cell or squamous cell skin cancer, in situ cervical cancer, or in situ breast cancer. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines.

Study Design

After dose escalation and determination of the recommended phase II dose, an expansion cohort was opened as part of an ongoing open-label, phase I study of IMGN853 monotherapy in adults with FRα-positive tumors. The primary objective in creating this cohort was to evaluate the safety and clinical activity of IMGN853 in a population of patients with FRα-positive, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Patients were administered IMGN853 intravenously once every 3 weeks at 6.0 mg/kg (adjusted ideal body weight), established as the recommended phase II dose during the dose-finding stage of the study.22 Patients continued to receive IMGN853 until intolerable toxicity or adverse events (AEs), disease progression, or investigator or patient decision. The study was conducted in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration regulations, the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was compliant with institutional review board and independent ethics committee requirements.

Assessments

Baseline assessments included medical history and physical examination, ECOG performance status, blood chemistry and hematology, serum pregnancy test, ophthalmologic examination, and ECG. During screening, radiologic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed. Overall tumor response was defined by RECIST (version 1.1) and assessed using computed tomography scans and cancer antigen 125 measurements performed every 6 weeks. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0) and monitored continuously throughout the study from the time of the first study dose until 28 days after treatment cessation. A serious AE was defined as any AE that was fatal or life threatening, required prolonged existing hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or required medical or surgical intervention.

Statistical Analysis

The objective of this expansion study was to explore the activity of IMGN853 in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer who had been treated with up to five prior lines of therapy. There was no prespecified sample-size justification; at the beginning, the cohort included 20 patients, and once encouraging activity was observed, more patients were added for a total of 46. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and baseline characteristics, and analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For the safety evaluations, baseline was defined as the last available assessment before day 1, cycle one, and any AE with the same onset date as the start of study treatment or later was reported as treatment emergent. The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of IMGN853. Efficacy analyses were based on the safety population, and all response-evaluable patients who underwent a postbaseline assessment were included in the objective response rate (ORR) analyses, along with the corresponding exact 95% CIs based on the Clopper-Pearson method. Progression-free survival (PFS) was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

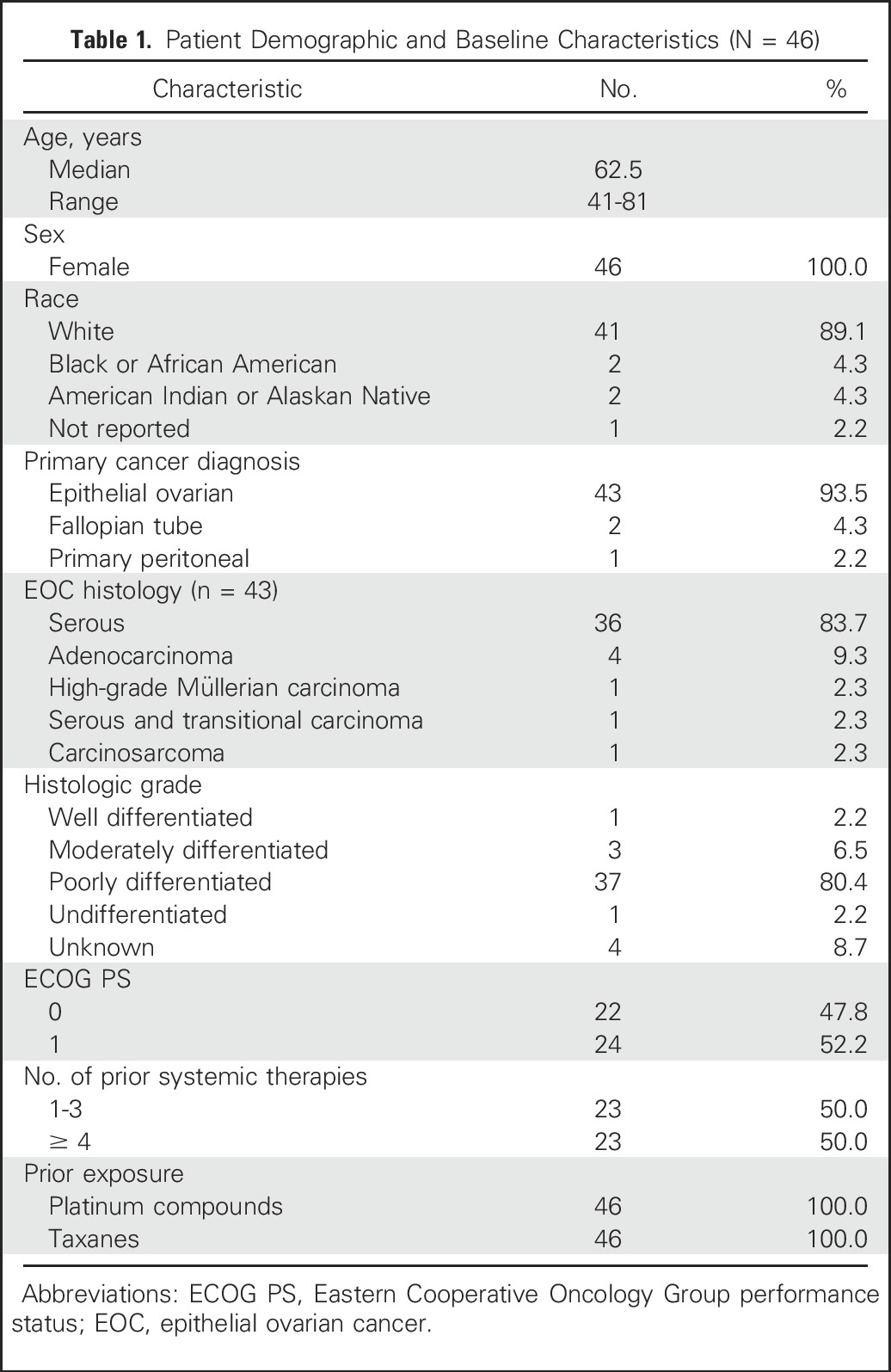

During screening, approximately 80% of patients with ovarian cancer met the inclusion criteria for FRα positivity by IHC assessment.23 Forty-six eligible patients were enrolled in the platinum-resistant expansion cohort and treated with IMGN853 at 6.0 mg/kg. The first patient enrolled in August 2014, and as of the data cutoff date of April 29, 2016, two patients remained in the study. Table 1 lists patient demographics for the safety population. The median age was 62.5 years (range, 41 to 81 years), and the distribution of primary tumor types was primarily epithelial ovarian carcinoma (94%), fallopian tube cancer (4%), and peritoneal cancer (2%). A majority of patients with EOC (84%) presented with serous histology. Most patients were white (89%) and had an ECOG performance status of 1 (52%). All individuals were heavily pretreated, with 100% having prior platinum and taxane exposure. Eleven patients (24%) had received only one prior platinum regimen (ie, primary platinum resistance), with the remaining 35 (76%) having received at least two lines of platinum-based therapy (ie, secondary resistance). One half of the study population (n = 23) had received one to three previous systemic therapies, and the other half had received four or five prior lines. The median duration of treatment with IMGN853 was 3.8 months, and the median follow-up period was 5.5 months.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Baseline Characteristics (N = 46)

Safety

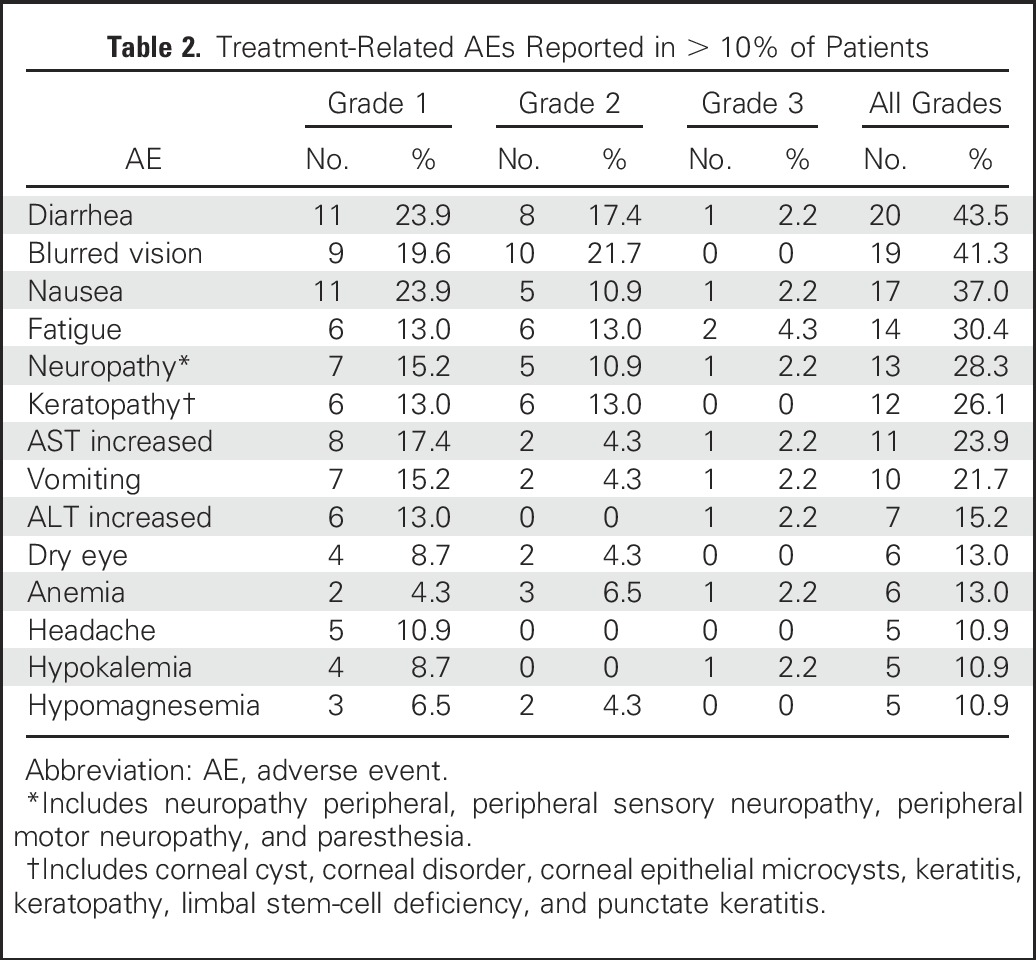

The most common treatment-related AEs occurring in more than 10% of patients were diarrhea (44%), blurred vision (41%), nausea (37%), fatigue (30%), neuropathy (28%), keratopathy (26%; including cases of corneal cyst, corneal disorder, corneal epithelial microcysts, keratitis, keratopathy, limbal stem-cell deficiency, and punctate keratitis), increased AST (24%), and vomiting (22%), the majority of which were grade 1 or 2 (Table 2). Overall, 12 patients (26%) experienced a grade 3 event, with the most frequent being fatigue and hypotension (both 4%). One patient experienced grade 4 febrile neutropenia and septic shock, which resolved after withdrawal from the study, and no fatalities resulting from related AEs were seen. Additional AEs leading to discontinuation involved individual cases of low-grade ocular disorders (grade 1 eye pain, corneal cysts, and grade 2 blurred vision), grade 2 pneumonitis, grade 3 hypersensitivity, and grade 3 myelodysplastic syndrome. In total, serious AEs deemed treatment related were observed in 11 patients (22%), with no individual events being observed for more than one patient.

Table 2.

Treatment-Related AEs Reported in > 10% of Patients

Clinical Activity

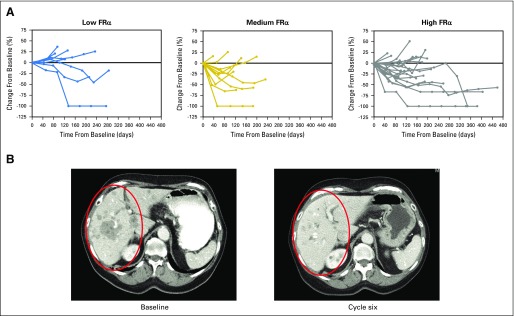

All 46 patients were included in the efficacy analyses. In the overall patient population, the ORR was 26% (95% CI, 14.3 to 41.1), including one complete and 11 partial responses (Table 3). As part of the analyses, patients were sorted based on FRα positivity (by IHC of archival tissue samples) as follows: low (25% to 49% of tumor cells with ≥ 2+ staining intensity), medium (50% to 74% of cells with ≥ 2+ intensity), or high (≥ 75% of cells with ≥ 2+ intensity). Figure 1A plots changes in patient target lesion burden as a function of time, with individuals grouped according to FRα level. Regardless of FRα expression (Table 3), a majority of patients experienced tumor shrinkage in response to IMGN853 treatment. An example of an objective response observed in a patient with high FRα expression with recurrent serous ovarian cancer after six cycles of therapy is shown in Figure 1B. After two cycles of IMGN853 treatment, the 74-year-old patient achieved a confirmed partial response, including a 45% decrease in a 5-cm liver mass and clearance of multiple smaller metastatic lesions. The patient remained in the study for 5.7 months until disease progression.

Table 3.

Summary of Efficacy Measures Grouped by FRα Expression

Fig 1.

(A) Percentage of tumor change in target lesions from baseline in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer grouped by folate receptor alpha (FRα) expression. Three patients are not represented in the plots: two with clinical progression and another who died before undergoing baseline assessment. (B) Activity of mirvetuximab soravtansine in a patient with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer with a partial response to therapy. Results are shown for a 74-year-old woman with recurrent serous ovarian cancer who presented with large, measurable liver metastases. Red circles show regression and clearance of multiple hepatic lesions by computed tomography after six cycles of treatment.

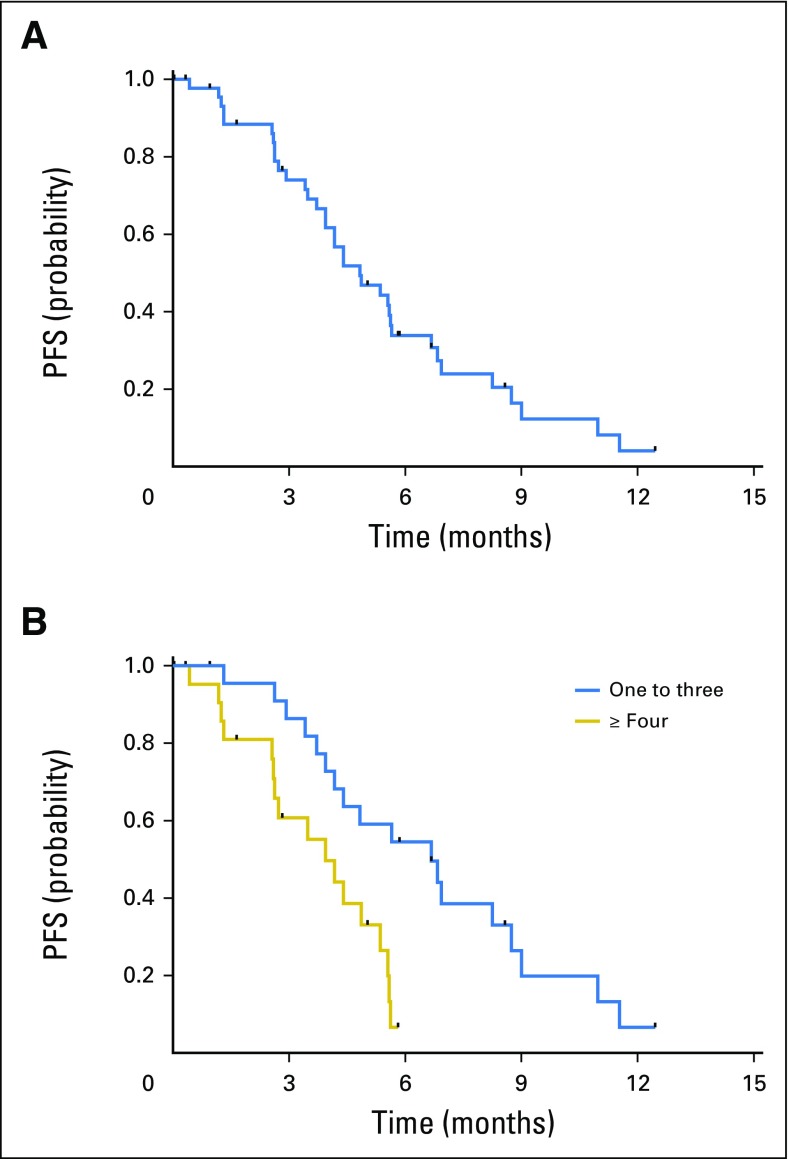

Of note, and although not a prespecified criterion for efficacy analysis, when patients were stratified based on previous lines of therapy (one to three v ≥ four [each n = 23]), a potential relationship with response was identified. The ORR in the cohort of patients who had received one to three prior lines was 39% (95% CI, 19.7 to 61.5), compared with 13% (95% CI, 2.8 to 33.6) in patients who had received four or more. For responding patients in the one-to-three subset, the median time to response was 11.1 weeks, and the median response duration was 19.6 weeks (95% CI, 17.7 to 44.1). This duration of response was similar to that seen for all responders (19.1 weeks; 95% CI, 16.1 to 33.1). Further evidence of improved outcomes in the less heavily pretreated population was provided by the PFS results (Figs 2A and 2B). The median PFS was 4.8 months (95% CI, 3.9 to 5.7 months) for the total population, 6.7 months (95% CI, 3.9 to 8.7 months) for the cohort of patients who had received one to three prior lines of therapy, and 3.9 months (95% CI, 2.6 to 5.4 months) for those who had received four or more.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) in (A) all patients (median, 4.8 months) and (B) cohorts of patients who had received one to three and four or more prior lines of therapy (median, 6.7 and 3.9 months, respectively; log-rank P = .002).

DISCUSSION

Although therapeutic options currently exist for patients with recurrent EOC, their response rates and durations of response remain disappointingly poor. Primary platinum-resistant disease in particular carries a dismal prognosis, with response rates to subsequent lines of therapy less than 20%. This is in stark contrast to patients with platinum-sensitive recurrences, who can expect response rates of 30% to 90% to additional platinum agents. In a recent study comparing survival outcomes in the resistance setting, Slaughter et al24 reported that patients with acquired platinum resistance had a median overall survival from the date of platinum resistance of 21.9 months, which was not statistically different from that in patients with primary platinum-resistant disease.

Despite the caveat that the population evaluated was largely racially homogenous, this expansion cohort study of IMGN853 among patients with FRα-positive, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer reports promising activity in a population of patients with few effective durable therapies. The ORR of 26% and median PFS of 4.8 months compare favorably with those of other available agents. For example, both pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and topotecan are widely used as second-line treatments for recurrent EOC.25 However, in an earlier phase III trial directly comparing these two chemotherapeutics, both agents were equally ineffective in the subset of patients with EOC defined by chemotherapy-resistant disease (ORR, 12% v 7%; median PFS, 9.1 v 13.6 weeks, respectively).26 Gemcitabine demonstrated an ORR of 29% and median time to progression of 20 weeks in a separate phase III trial in recurrent EOC,27 which included patients who had experienced treatment failure within 12 months of receipt of only one prior regimen of platinum plus paclitaxel. Of particular note, when patients in our study were stratified based on number of prior therapies, the cohort of individuals enrolled who had received one to three prior lines (ie, early acquisition of platinum resistance) demonstrated a response rate of 39% and median PFS of 6.7 months. These efficacy measures are comparable to those observed in the pivotal AURELIA (Avastin Use in Platinum-Resistant Epithelial Ovarian Cancer) trial (response rate, 31%; median PFS, 6.7 months),28 which led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of bevacizumab for use alongside chemotherapy in patients with platinum-resistant EOC who have received no more than two prior therapeutic regimens.

The principal AE seen in patients was diarrhea, with a majority of cases being mild (grade 1 or 2) and readily managed by appropriate supportive measures. Treatment-emergent ocular disorders, primarily blurred vision and corneal keratopathy, were also observed at a relatively high frequency during the study. Although these events were not severe (≤ grade 2) and did not result in long-term damage, they were managed with dose modification (delay and/or reduction) and responsible for the study discontinuation of only one patient. In this regard, ocular AEs have emerged as an important consideration for a number of ADCs undergoing clinical trials,29 and the profile of visual disturbances and corneal abnormalities seen with IMGN853 treatment was consistent with those most frequently observed with a variety of other ADCs. The etiology of such events is not well understood; keratopathy has occurred with a diverse range of ADCs that target different antigens and use different cytotoxic payloads.29 Early recognition of these ocular AEs prompted the mandating of daily lubricating eye drops for all patients receiving IMGN853 approximately midway through the expansion phase. Implementation of this proactive measure, in conjunction with other ocular management procedures (eg, avoidance of contact lenses, regular cleaning and warm compress use, sunglasses in daylight, and so on), subsequently decreased both the incidence and grade of visual disturbances in patients in the study.30 Separately, the ongoing phase I trial was amended to include an expansion cohort implementing primary prophylaxis with corticosteroid eye drops to determine the effectiveness of this strategy in reducing the prevalence of ocular toxicities.

A key feature of ADCs is that they are designed to deliver cytocidal amounts of therapeutic agents directly to the site of tumors,31,32 including compounds that, on their own, are too toxic to be clinically useful. A majority of ADCs currently undergoing clinical evaluation, including IMGN853, use highly cytotoxic tubulin-targeting compounds (eg, maytansinoids, auristatins) as their payload.33 The cytotoxin used in IMGN853 is DM4, a thiol-containing derivative of maytansine, which inhibits microtubule assembly in a manner similar to that of vinca alkaloids but with up to 1,000-fold greater potency.34 The results presented here confirm that conjugation of this antimitotic agent to a tumor-selective antibody affords a means of achieving a meaningful therapeutic window, as evidenced by the low systemic toxicities and robust antitumor activity seen in this patient population. Indeed, the efficacy data support the clinical exploitation of FRα as an avenue for targeted therapeutic intervention in ovarian cancer, particularly in those patients with elevated endogenous receptor expression.

Despite favorable efficacy outcomes, however, responding patients in this trial eventually experienced progression during IMGN853 therapy, and the underlying reason or reasons remain to be defined. In preclinical leukemic models, P-glycoprotein activity was shown to attenuate DM4 cytotoxicity, although this mechanism was not sufficient to account for resistance observed in patient-derived samples.35 Overall, further elucidation of potential mechanisms of inherent and acquired resistance to IMGN853 will be informative for the continued application of this promising therapeutic. Moreover, the integration of molecularly targeted agents with alternate mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities to established chemotherapeutic regimens has proven important in the management of EOC, best exemplified by the approval of bevacizumab as part of combination treatments. It is reasonable to suggest that such an approach may also be effective in delaying or counteracting the development of resistance to IMGN853 (via targeting differentially resistant clones) as well as in providing an opportunity for improved therapeutic outcomes. Preclinically, IMGN853 can potentiate the activity of conventional agents indicated for use in EOC (including carboplatin, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and bevacizumab),36 which in turn has prompted the clinical exploration of IMGN853-based combinations in an ongoing phase IB study (FORWARD II; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02606305).

In summary, IMGN853 possesses favorable tolerability and is active in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, evidenced by encouraging response rates and PFS. The activity seen in these patients was considered at least as good as that with standard of care for this difficult-to-treat population of patients with ovarian cancer; for patients with medium or high FRα expression who have received fewer lines of prior therapy, the efficacy seems to be better than that of standard single-agent chemotherapy. On the basis of these findings, a randomized phase III trial comparing the safety and efficacy of IMGN853 with those of physicians’ choice of chemotherapy in platinum-resistant patients with three or fewer previous therapies and medium or high FRα expression (FORWARD I; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02631876) is being conducted.

Footnotes

Supported by ImmunoGen.

Presented in part at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 3-7, 2016, Chicago, IL.

Clinical trial information: NCT01609556.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kathleen N. Moore, David M. O’Malley, Rodrigo Ruiz-Soto, Michael J. Birrer

Provision of study materials or patients: David M. O’Malley, Ursula A. Matulonis, Jason A. Konner, Raymond P. Perez, Todd M. Bauer

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: Kathleen N. Moore, Todd M. Bauer, Rodrigo Ruiz-Soto, Michael J. Birrer

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Safety and Activity of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine (IMGN853), a Folate Receptor Alpha–Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate, in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer: A Phase I Expansion Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Kathleen N. Moore

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech (Inst), ImmunoGen (Inst), Advaxis, AstraZeneca (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, VBL Therapeutics (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Novacure

Lainie P. Martin

Consulting or Advisory Role: ImmunoGen

Research Funding: AbbVie (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: ImmunoGen

David M. O’Malley

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Janssen Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen

Research Funding: AstraZeneca (Inst), Clovis Oncology (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), VentiRx (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), ImmunoGen (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), Ergomed (Inst), Ajinomoto (Inst), Tesaro (Inst), Ludwig Cancer Research (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Stemcentrx (Inst), Cerulean Pharma (Inst), Pharma Mar (Inst)

Ursula A. Matulonis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, ImmunoGen, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Genentech

Jason A. Konner

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech, Clovis Oncology

Research Funding: Genentech, AstraZeneca, TapImmune

Raymond P. Perez

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pharmaceutical Research Associates

Research Funding: Eli Lilly (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Dompé Farmaceutici (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Agensys (Inst), ImmunoGen (Inst), TetraLogic Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Altor BioScience (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Onyx Pharmaceuticals (Inst), MedImmune (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Regeneron (Inst)

Todd M. Bauer

No relationship to disclose

Rodrigo Ruiz-Soto

Employment: ImmunoGen

Stock or Other Ownership: ImmunoGen

Michael J. Birrer

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures. 2016 http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/

- 2.Davis A, Tinker AV, Friedlander M. “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: What is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bookman MA. Extending the platinum-free interval in recurrent ovarian cancer: The role of topotecan in second-line chemotherapy. Oncologist. 1999;4:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, et al. Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:389–393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore ME, Fryatt I, Wiltshaw E, et al. Treatment of relapsed carcinoma of the ovary with cisplatin or carboplatin following initial treatment with these compounds. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90174-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose PG, Fusco N, Fluellen L, et al. Second-line therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin for recurrent disease following first-line therapy with paclitaxel and platinum in ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1494–1497. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elnakat H, Ratnam M. Distribution, functionality and gene regulation of folate receptor isoforms: Implications in targeted therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1067–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salazar MD, Ratnam M. The folate receptor: What does it promise in tissue-targeted therapeutics? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:141–152. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledermann JA, Canevari S, Thigpen T. Targeting the folate receptor: Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to personalize cancer treatments. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2034–2043. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalli KR, Oberg AL, Keeney GL, et al. Folate receptor alpha as a tumor target in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toffoli G, Russo A, Gallo A, et al. Expression of folate binding protein as a prognostic factor for response to platinum-containing chemotherapy and survival in human ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:121–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980417)79:2<121::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marchetti C, Palaia I, Giorgini M, et al. Targeted drug delivery via folate receptors in recurrent ovarian cancer: A review. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1223–1236. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S40947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergote IB, Marth C, Coleman RL. Role of the folate receptor in ovarian cancer treatment: Evidence, mechanism, and clinical implications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10555-014-9539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assaraf YG, Leamon CP, Reddy JA. The folate receptor as a rational therapeutic target for personalized cancer treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2014;17:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutz RJ. Targeting the folate receptor for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 2015;4:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert JM. Drug-conjugated antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76:248–262. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erickson HK, Widdison WC, Mayo MF, et al. Tumor delivery and in vivo processing of disulfide-linked and thioether-linked antibody-maytansinoid conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:84–92. doi: 10.1021/bc900315y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong EE, Erickson H, Lutz RJ, et al. Design of coltuximab ravtansine, a CD19-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for the treatment of B-cell malignancies: Structure-activity relationships and preclinical evaluation. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:1703–1716. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovtun YV, Audette CA, Ye Y, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates designed to eradicate tumors with homogeneous and heterogeneous expression of the target antigen. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3214–3221. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ab O, Whiteman KR, Bartle LM, et al. IMGN853, a folate receptor-α (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, exhibits potent targeted antitumor activity against FRα-expressing tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1605–1613. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borghaei H, O’Malley DM, Seward SM, et al. : Phase 1 study of IMGN853, a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) in patients (Pts) with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) and other FRA-positive solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 5558)

- 23.Martin LP, Moore KN, O'Malley DM, et al. : Association of folate receptor alpha (FRα) expression level and clinical activity of IMGN853 (mirvetuximab soravtansine), a FRα-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), in FRα-expressing platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients (pts). Mol Cancer Ther 14:12s 2015 (suppl; abstr C47)

- 24.Slaughter K, Holman LL, Thomas EL, et al. Primary and acquired platinum-resistance among women with high grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye H, Karim AA, Loh XJ. Current treatment options and drug delivery systems as potential therapeutic agents for ovarian cancer: A review. Mater Sci Eng C. 2014;45:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, et al. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: A randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–3322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrandina G, Ludovisi M, Lorusso D, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:890–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1302–1308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eaton JS, Miller PE, Mannis MJ, et al. Ocular adverse events associated with antibody-drug conjugates in human clinical trials. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31:589–604. doi: 10.1089/jop.2015.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore KN, Martin LP, Matulonis UA, et al. : IMGN853 (mirvetuximab soravtansine), a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC): Single-agent activity in platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients (pts). J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr 5567)

- 31.Chari RV. Targeted cancer therapy: Conferring specificity to cytotoxic drugs. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:98–107. doi: 10.1021/ar700108g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chari RV, Miller ML, Widdison WC. Antibody-drug conjugates: An emerging concept in cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:3796–3827. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas A, Teicher BA, Hassan R. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e254–e262. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raufi A, Ebrahim AS, Al-Katib A. Targeting CD19 in B-cell lymphoma: Emerging role of SAR3419. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:225–233. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S45957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang R, Cohen S, Perrot JY, et al. P-gp activity is a critical resistance factor against AVE9633 and DM4 cytotoxicity in leukaemia cell lines, but not a major mechanism of chemoresistance in cells from acute myeloid leukaemia patients BMC Cancer 9199, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponte JF, Coccia J, Lanieri L, et al. : Preclinical evaluation of mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853) combination therapy in ovarian cancer xenograft models. Mol Cancer Ther 14:12s 2015 (suppl; abstr C170)