Abstract

Manipulation of sex determination pathways in insects provides the basis for a wide spectrum of strategies to benefit agriculture and public health. Furthermore, insects display a remarkable diversity in the genetic pathways that lead to sex differentiation. The silkworm, Bombyx mori, has been cultivated by humans as a beneficial insect for over two millennia, and more recently as a model system for studying lepidopteran genetics and development. Previous studies have identified the B. mori Fem piRNA as the primary female determining factor and BmMasc as its downstream target, while the genetic scenario for male sex determination was still unclear. In the current study, we exploite the transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate a comprehensive set of knockout mutations in genes BmSxl, Bmtra2, BmImp, BmImpM, BmPSI and BmMasc, to investigate their roles in silkworm sex determination. Absence of Bmtra2 results in the complete depletion of Bmdsx transcripts, which is the conserved downstream factor in the sex determination pathway, and induces embryonic lethality. Loss of BmImp or BmImpM function does not affect the sexual differentiation. Mutations in BmPSI and BmMasc genes affect the splicing of Bmdsx and the female reproductive apparatus appeared in the male external genital. Intriguingly, we identify that BmPSI regulates expression of BmMasc, BmImpM and Bmdsx, supporting the conclusion that it acts as a key auxiliary factor in silkworm male sex determination.

Author Summary

The sex determination system extremely diverse among organisms including insects in which even each order occupy a different manner of sex determination. The silkworm, Bombyx mori, is a lepidopteran model insect with economic importance. The mechanism of the silkworm sex determination has been in mystery for a long time until a Fem piRNA was identified as the primary female sex determinator recently. However, genetic and phenotypic proofs are urgently needed to fully exploit the mechanism, especially of the male sex determination. In the current study, we provided comprehensively genetic evidences by generating CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout mutations for those genes BmSxl, Bmtra2, BmImp, BmImpM, BmPSI and BmMasc, which were considered to be involved in insect sex determination. The results showed that mutations of BmSxl, BmImp and BmImpM had no physiological and morphological effects on the sexual development while Bmtra2 depletion caused Bmdsx splicing disappeared and induced embryonic lethality. Importantly, the BmPSI regulates expression of BmMasc, BmImpM and Bmdsx, supporting the conclusion that it acts as a key auxiliary factor to regulate the male sex determination in the silkworm.

Introduction

Genetic systems for sex determination in insects show high diversity in different species. Sex determination in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is controlled hierarchically by X:A > Sxl > tra/tra2 > dsx and fru [1, 2]. The X:A ratio of 1 promotes transcription of Sex-lethal (Sxl) and results in feminization, while 0.5 to Sxl suppression and male differentiation [3–10]. Sxl proteins control the splicing of female transformer (tra) mRNAs that give rise to functional proteins, while no functional Sxl proteins exist in the male [11,12]. The search of homolog genes in the sex determination of D. melanogaster has been found a conserved relationship among dsx/tra across dipterans [13, 14] In another Diptera, Musca domestica, female employs a FD allele which is encoded by the tra gene [15]. The medfly, Ceratitis capitata, has an as yet unidentified dominant male-determining factor on the Y chromosome [16]. The sex determination factors (F or M) in these two insects control the downstream gene doublesex (dsx) to generate sex-specific splicing isoforms. In contrast to Drosophila, Cctra and Mdtra seem to initiate an autoregulatory mechanism in XX embryos that provides continuous tra female-specific function and acts as a cellular memory maintaining the female pathway [17–19]. Many other insect species also exploit tra as the sex determination factor. For example, the honeybee, Apis mellifera, uses the complementary sex determiner gene (csd) to regulate feminization, which activates the feminizer gene (fem) by directing splicing to form the female functional Fem protein [20]. This fem gene is considered an orthologue of Cctra gene [21]. The tra gene in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum, controls female sex determination by regulating dsx sex-specific splicing [22]. Also, Lucilia cuprina and Nasonia vitripennis, are reported to use tra as a female-determining signal [23, 24]. Recently, Hall et al. identified Nix a distant homolog of transformer2 (tra2) from Aedes aegypti as the male-determining factor [25]. These data shows that the dsx/tra axis is conserved in many insect species and tra is the key gene around which variation in sex determining mechanisms has evolved in all insect species with the exception of Aedes and Lepidopteran insects.

Species of lepidoptera exhibit markedly different sex determination pathways from those seen in the flies, bees and beetles [26]. In the silkworm Bombyx mori, females possess a female-determining W chromosome have heteromorphic sex chromosomes (ZW) and males are homomorphic (ZZ) [27]. No tra ortholog has been identified in this order, possibly as a result of highly divergent sequence [28]. Bioinformatic analyses fail to identify a tra ortholog in B. mori and no dsxRE (dsx cis-regulatory element) binding sites are found in the target gene ortholog, Bmdsx, resulting in the default mode of female-specific splicing of the latter [29, 30]. BmPSI (P-element somatic inhibitor) and BmHrp28 (hnRNPA/B-like 28) were reported to regulate Bmdsx splicing through binding CE1 sequences of the female-specific exon 4 of Bmdsx pre-mRNA [30, 31]. Another potential regulator, BmImp (IGF-II mRNA binding protein), enhances the male-specific splicing of Bmdsx pre-mRNA by increasing RNA binding activity of BmPSI [32]. The Z-linked BmImp binds to the A-rich sequences in its own pre-mRNA to induce the male-specific splicing of its pre-mRNA, and this splicing pattern is maintained by an autoregulatory mechanism, being BmImpM (the male-specific splicing form of BmImp) able to bind its corresponding pre-mRNA [33]. Since BmPSI or BmImp products do not exhibit any sequence similarities to known Ser/Arg (SR) proteins, such as Tra and Tra2, the regulatory mechanisms of sex-specific alternative splicing of Bmdsx that of exon skipping is distinct from that of Dmdsx that of 3’ alternative splice[34]. Recently, the product of the W chromosome-derived B. mori sex determination factor fem (female-enriched PIWI-interacting RNA) was identified to target the downstream gene BmMasc for controlling Bmdsx sex-specific splicing [35]. This remarkable finding reveals that fem is the primary female sex determinator in the silkworm. However, the genetic relationship among these genes in B. mori sex determination is still in mystery.

We use here a binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate somatic mutations in sex determination pathway genes in B. mori. Three genes, BmMasc, BmPSI and BmImp, are involved in sex regulation only in lepidopteran insects, and two, Bmtra2 and BmSxl, are structural orthologs of the key sex regulation factors in Drosophila. We focus on the sexually dimorphic traits of reproductive structures and sex-specific alternative splicing forms of Bmdsx, the bottom gene of the sex determination. The results show that BmPSI and BmMasc affect Bmdsx splicing and the male reproductive tissues, supporting the conclusion that they have roles in sex determination. Disruption of BmImp or Bmtra2 causes severe developmental defects in both sexes, supporting their critical roles other than sex determination. Furthermore, loss-of-function mutations of BmPSI altered transcriptional or post-transcriptional (splicing) of BmMasc, BmImp and Bmdsx in males. These data strongly support the conclusion that BmPSI plays a key auxiliary in male sex determination in B. mori.

Results

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of sex determination genes

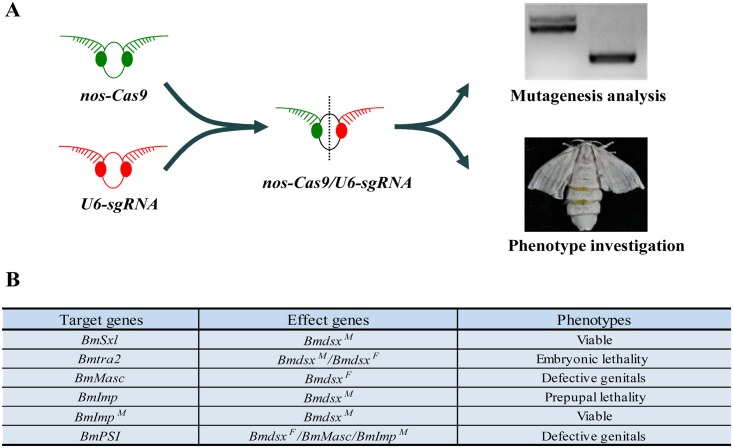

We established a binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system to make somatic mutagenesis targeting selected genes. This system contains two separated lines, one is to express Cas9 protein under the control of a B. mori nanos promoter (nos-Cas9) and another is to express sequence-specific sgRNAs under the control of a B. mori U6 promoter (U6-sgRNA). Two independent lines of nos-Cas9 and from three to 29 independent lines of each U6-sgRNA construct were obtained following piggyBac-mediated transgenesis (S1 Table). Genomic mutagenesis in F0 animals was confirmed by genomic PCR, and subsequent physiological phenotypes were investigated (Fig 1). The results confirm that the transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system works effectively (S1–S5 Figs).

Fig 1. Loss-of-function analysis of B.mori sex determination genes.

(A) Schematic representation of functional analysis using the transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system. nos-Cas9 (green) transgenic moths were crossed with U6-sgRNA (red) transgenic moths and the F0 heterozygotes were analyzed as for genotypic and phenotypic effects. (B) Genes affected and major phenotypic effects observed in mutants.

BmPSI regulates transcription of BmMasc and BmImpM

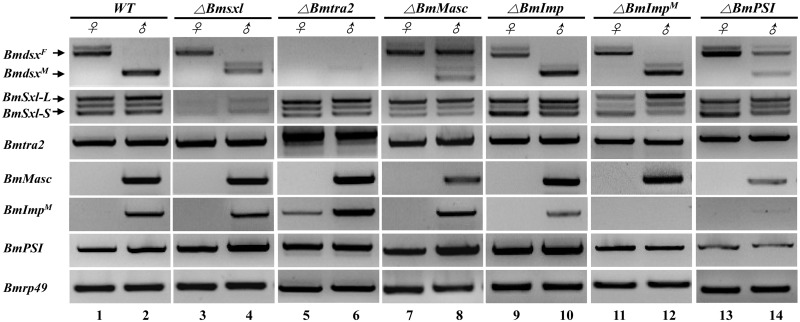

Bmdsx is the conserved downstream component of the silkworm sex determination pathway and mutations in BmPSI and BmMasc had an effect on its splicing. Mutations in BmSxl, BmImp and BmImpM resulted in the appearance of a larger BmdsxM (the male-specific splicing form of Bmdsx) mRNA isoform while the profile of BmdsxF (the female-specific splicing form of Bmdsx) appeared unaltered (Fig 2, lanes 4, 10 and 12). Sequence analysis of the larger BmdsxM isoform revealed an 81base-pairs (bp) length fragment insertion, creating a novel splice variant (S6 Fig). All Bmdsx isoforms were absent in both sexes in individuals carrying mutations in Bmtra2 (Fig 2, lanes 5 and 6). Mutations in BmMasc and BmPSI in males resulted in a decreased accumulation of BmdsxM and the appearance of BmdsxF (Fig 2, lanes 8 and 14), which was consistent with previous report when BmMasc expression was disrupted by using RNAi [35].

Fig 2. PCR-based gene amplification analyses for targeted genes in wild type (WT) and mutant animals.

Six genes, BmSxl, Bmtra2, BmMasc, BmImp, BmImpM, and BmPSI, were mutated and corresponding expression files were listed. Expression of Bmdsx was investigated as a general indicator. BmdsxF and BmdsxM represent the female- and male-specific splicing isoforms of Bmdsx, respectively. BmSxl-L and BmSxl-S represent two different isoforms of the BmSxl gene. The lower panel shows amplification of the rp49 transcript, which serves as an internal control for RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

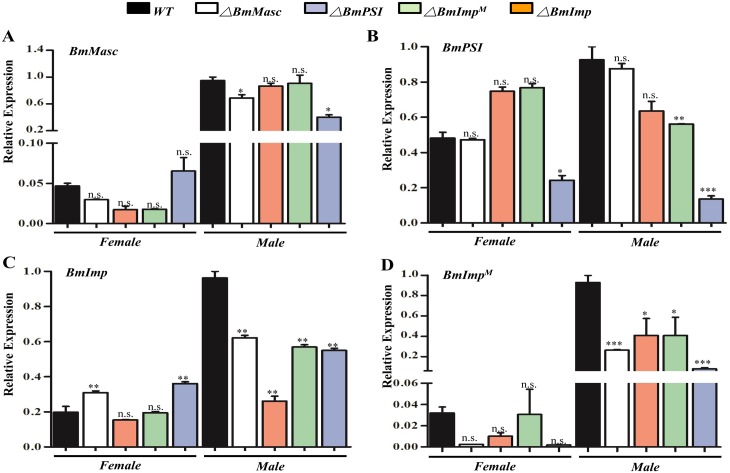

RT-PCR-based analysis revealed that mutations in BmSxl, BmMasc, BmImp and BmImpM had no or minor effect on other genes at transcriptional or post-transcriptional (splicing) levels except Bmdsx. The male-specific BmImp (BmImpM) isoform appeared in female Bmtra2 mutants (Fig 2, lanes 5 and 6). This supports the conclusion that Bmtra2 is not only involved in regulating Bmdsx, but also has a role in splicing regulation of BmImpM. Interestingly, the abundance of BmMasc and BmImpM transcripts decreased in BmPSI mutant males (Fig 2, lane 14). Q-RT-PCR analysis showed that BmImpM and BmMasc mRNA levels decreased by 92% and 60%, respectively, in BmPSI mutant males (Fig 3). These results support the conclusion that BmPSI regulates BmMasc and BmImpM at the splicing level. In contrast to the results in males, with the exception of Bmtra2, no effects on transcript profiles were seen in any of the mutant females.

Fig 3. Q-RT-PCR analysis for investigation of BmMasc, BmImpM, BmImp and BmPSI transcript abundance in corresponding mutants.

(A-D) Relative mRNA expression levels of BmMasc, BmPSI, BmImp and BmImpM in mutant males and females, respectively. Three individual biological replicates were performed in q-RT-PCR. Error bar: SD; *, ** and *** represented significant differences at the 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 level (t-test) compared with the control.

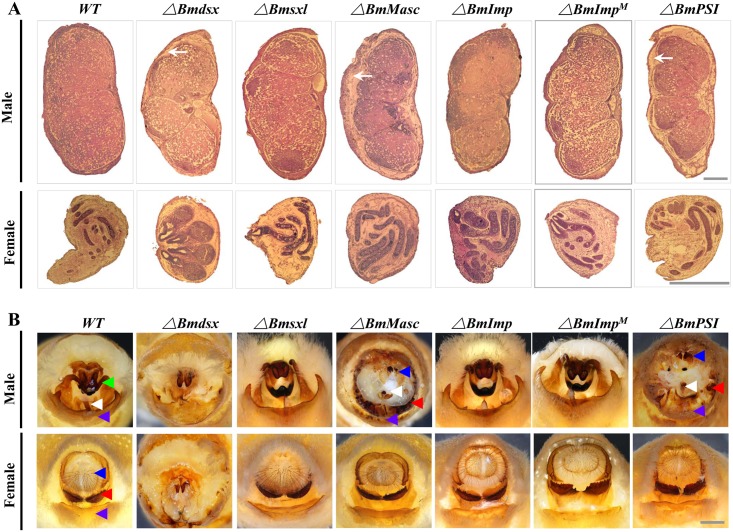

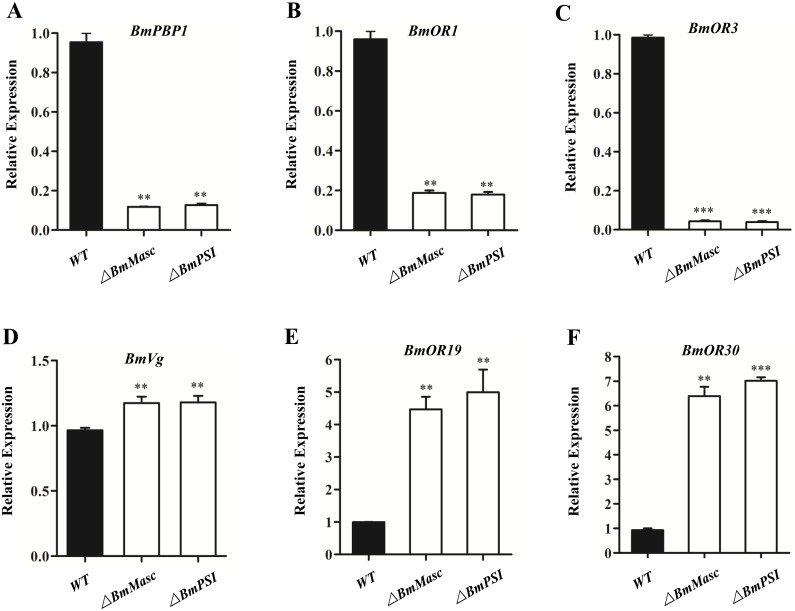

BmPSI and BmMasc control male sexual differentiation

The morphology of the external and internal genitalia provides a direct index of sexual differentiation in B. mori. Mutations in BmMasc result in males with degenerative testes similar to that observed with Bmdsx mutants (Fig 4A, lanes 2 and 4). The external genitalia of males exhibit characteristics of the copulatory organs of both males and females including the female-specific ventral chitin plate and genital papillae (Fig 4B, lanes 2 and 4). The testes and external genitalia of mutant BmPSI males are similar phenotypes of mutations in BmdsxM or BmMasc and result in male sterility (Fig 4A, lane 7; Fig 4B, lane 7). The external and internal genitalia appear normal in both males and females with mutations in BmSxl, BmImp, and BmImpM, (Fig 4A, lanes 3, 5, 6; Fig 4B, lanes 3, 5, 6). The putative dsx target male-specific expression genes in the male olfactory system, pheromone binding protein 1 (BmPBP1), olfactory receptors (BmORs) BmOR1, BmOR3, were significantly down-regulated in the BmMasc and BmPSI male mutants (Fig 5A–5C). In contrast, the female-specific expression genes in the female oogenesis and olfactory system, vitellogenin (BmVg), BmOR19, BmOR30, were significantly up-regulated in the BmMasc and BmPSI male mutants (Fig 5D–5F). These morphological results and corresponding gene expression profiles provide additional support for the conclusion that BmPSI and BmMasc control male sexual differentiation.

Fig 4. Morphological changes in sexually-dimorphic reproductive system structures in wild-type (WT) and mutant silkworms.

(A) Morphology of internal gonad structure in paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Gonads are dissected from wild-type and mutant males and females on the fourth day of the fifth-instar. White arrows show the separation of the testis envelope from the testicular lobe. Scale bars: 250μm. (B) Gross morphology of external genitalia of control and mutant adults. Key to arrows: red, ventral chitin plate; blue, genital papillae; white, penis; green, clasper; and purple, ventral plates. Scale bars: 1mm.

Fig 5. Q-RT-PCR analysis of the putative downstream genes of Bmdsx in the BmMasc and BmPSI mutants.

(A-F) Relative mRNA expression levels of BmPBP1, BmOR1, BmOR3, BmVg, BmOR19 and BmOR30 in mutant males. Three individual biological replicates were performed in q-RT-PCR. Error bar: SD; ** and *** represented significant differences at the 0.01, 0.001 level (t-test) compared with the control.

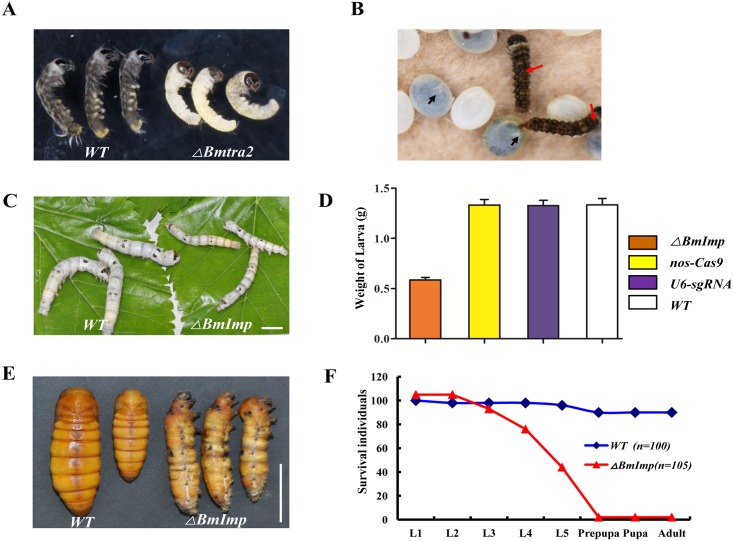

Bmtra2 and BmImp have pleiotropic effects in development

Mutations in Bmtra2 result in lethality at later embryonic stages (Fig 6A and 6B). This phenotype is similar to that reported in the honeybee in which down-regulation of Amtra2 causes embryonic viability and affects the female-specific splicing of fem and Amdsx transcripts [36]. Also, in T. castaneum, only a few eggs could be produced by animals after the parental RNAi of Tctra-2 and these eggs ultimately failed to hatch [37]. This is different from Dipteran species, in which tra2 has no vital function in embryogenesis [38]. The similarity of these phenotypes supports the hypothesis that Bmtra2 and its orthologs have an essential, ancestrally- and evolutionarily-conserved function in embryogenesis that is not related to sex determination that predates the divergence of the Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera.

Fig 6. Pleiotropic effects of mutations in the Bmtra2 and BmImp genes.

(A and B) Embryonic lethality in progeny of the mating of nos-Cas9 and U6-Bmtra2-sgRNA: F0 individuals complete embryogenesis (A) but fail to hatch (B). Embryos appear intact at eight days after oviposition and died on the twelfth day. Red arrows indicate control and black arrows indicate mutants. (C-F) Loss of BmImp function affects growth and metamorphic development. (C and D) Phenotypes of larvae resulted from crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmImp-sgRNA at the fifth day of the final larval instar. Smaller larvae are from mutant insects and larger larvae were from controls as showed in C. Scale bar: 1 cm. Data are from the crosses of ΔBmImp (nos-Cas9/U6-sgRNA), nos-Cas9 (nos-Cas9/-), U6-sgRNA (-/U6-sgRNA) and WT (wild-type) as shown in D. E, Most larvae do not complete metamorphosis and die at the prepupal stage. Morphology of fifth instar larvae (ΔBmImp) compared to control. F, percent of wild-type (control, blue line) and mutant (ΔBmImp, red line) silkworms progressed through development. Key: L1-5, last day of the first, second, third and fourth larval instars, respectively. Data are from ΔBmImp (n = 105) and control (n = 100) animals.

Two distinct types of mutations were induced in BmImp, the first one targets all splice variants (BmImp), and the second one is only in the male-specific splice variant (BmImpM) (S4 Fig). However, neither had an effect on the morphology of the genitalia despite the observed effect on BmdsxF. While the growth indices of BmImpM mutant silkworms were normal, the body size and weight of the BmImp mutants was smaller than wild-type animals (Fig 6C and 6D). They failed to molt at each larval instar and the majority died at the later larval and prepupal stages (Fig 6E and 6F).

Discussion

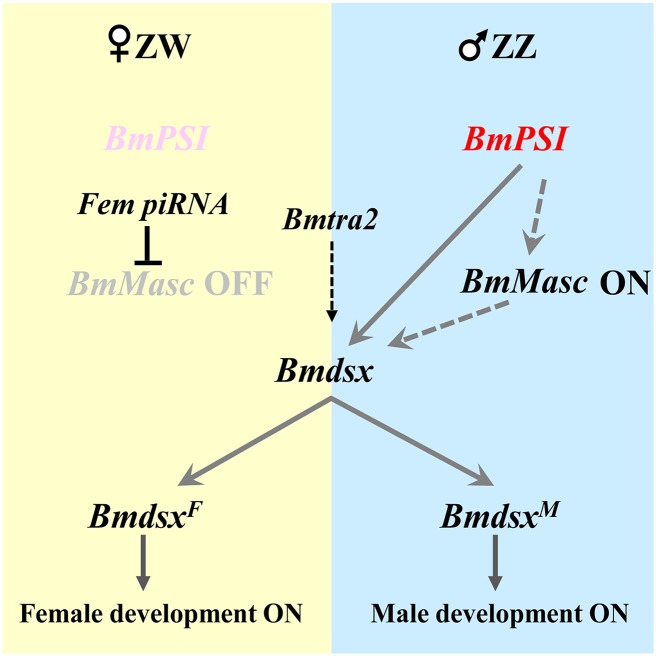

We provide here genetic evidence for the proposed sex determination pathway in B. mori that emphasizes the key roles of the products of the BmPS1 and BmMasc genes in male determination and differentiation (Fig 7). B. mori has the ZZ/ZW sex chromosome system in which the female is ZW (heterogametic) and the male is ZZ (homogametic). The Fem piRNA gene is located on the W chromosome and maintains feminization through downregulating BmMasc expression. Without the BmMasc protein in ZW embryos, the default (full-length) splicing isoform of Bmdsx (BmdsxF) activates downstream gene expression and produces female-specific development. BmPSI is not involved in this pathway, since mutations in it have no observable effects on female differentiation. BmPSI protein in males interacts with the Bmdsx pre-mRNA and generates the male-specific Bmdsx splice variant (BmdsxM) [30]. The BmMasc product might play the role of a recruitment or splicing factor to participate in this event. BmMasc is expressed normally in males due to lack of Fem piRNA, and thus may be controlled by BmPSI.

Fig 7. Proposed genetic cascade of sex determination in B. mori.

The Fem piRNA derived from female W chromosome downregulates Masc expression (yellow panel) [27]. Absence of Masc products and inactive BmPSI result in splicing that produces the female-specific isoform of Bmdsx (BmdsxF), which contain all of the exons of the gene. BmdsxF products induce female determination and differentiation of morphological sex characteristics. Thus, female development is the default sex determination pathway. Masc products are expressed normally in the male due to the lack of Fem and presence of active BmPSI, and this results in splicing of the male-specific isoform of Bmdsx (BmdsxM, blue panel), which contain exons of 1, 2, 5 of the Bmdsx pre-mRNA. BmdsxM products promote male development. The tra2 product also is involved in the regulation of Bmdsx.

Significant differences are evident in the B. mori sex-determination system when compared to D. melanogaster. Sxl has a major and early role in sex determination in the fruit fly. Its ‘on/off’ status serves as the primary signal to trigger somatic sex differentiation by controlling its own splicing (autocatalytically) and of tra [38]. However, Sxl does not show sex-specific splicing and function in other dipterans [39]. Furthermore, the silkworm ortholog, BmSxl, has two splicing isoforms, neither of which is regulated in a sex-specific manner [40]. Depletion of Bmsxl induced a longer BmdsxM sex-specific splicing form appeared, just as seen in BmImp or BmImpM disruption. Although the potential role of this splicing form was unclear, it did not bring any phenotypic consequence in male sexual dimorphism. The presence of a longer BmdsxM splicing form might because the spliceosome is complex machinery containing up to 300 proteins and loss of additional auxiliary factors having little roles [41, 42].

Dmtra2 is a co-binding protein of sex determination key gene Dmtra, and acts on the D. melanogaster sex-determination cascade to regulate both somatic sexual differentiation and male fertility [43]. However, the ortholog encoding the tra appears to not exist in the silkworm, and therefore Bmtra2 might have distinct roles. Bmtra2 could regulate female-specific splicing of Dmdsx and RNAi knockdown of Bmtra2 in the early embryo could cause abnormal testis formation in B. mori [44]. Our data support the conclusion that Bmtra2 regulates Bmdsx in both males and females, and has sex-independently essential roles during embryogenesis although the mechanism of embryonic lethality induced by Bmtra2 mutagenesis is not known. Another phenomena is BmImpM appeared in the Bmtra2 mutants, indicating that Bmtra2 is involved in regulating the upstream transcriptional factors of BmImpM. It is similar with Dmtra2 which regulates many downstream genes [45].

The BmImp gene was firstly identified in the silkworm as a co-binding protein with BmPSI [32]. BmImp produces two splice variants, one of which (BmImpM) is expressed in various tissues only in males and is proposed to be an essential regulator in the B. mori sex determination cascade [33]. BmImpM could bind the Bmdsx pre-mRNA and knock-down of its product induced the female-specific Bmdsx splicing form in male cell lines and embryos [33, 46]. We cannot account for the differences in our results, but speculate that they could be a consequence of different methods between RNAi and Cas9-mediated gene silencing, or different materials between cell lines and the intact animal. However, our phenotypic results are consistent with those seen in D. melanogaster and the mouse. In the fruit fly, loss-of-function Imp mutations were zygotic lethal which through imprecise P excision, or mutants die later as pharate adults by two loss-of-function alleles, H44 and H149 [47, 48]. Imp1 mutations in mice produced animals that were ~40% smaller than wild-type controls, and these exhibited high perinatal mortality [49]. Our experiments in which we mutate all isoforms of BmImp or only BmImpM did not result in any effects on sexual organs or sex determination genes. We conclude that BmImp and BmImpM are not essential for sex regulation but are needed for development.

BmMasc had been identified as a downstream target of Fem-piRNA which could induce BmdsxF in male embryos after siRNA-mediated knocking down [35]. BmMasc also controls dosage compensation in male embryos, and male embryos injected with BmMasc siRNA did not hatch normally [35]. Kiuchi et al. [35] used two siRNAs to knockdown BmMasc and reported detecting BmdsxF in male embryo and the down-regulation of BmImpM. They proposed that BmImpM and Bmdsx are located downstream of BmMasc in the sex determination cascade. In contrast, our genetic analyses show no evidence of an effect of BmMasc on BmImpM. We propose that BmMasc controls male sexual differentiation by regulating Bmdsx but has no regulatory effect on BmImpM. It is still unclear how BmMasc regulates Bmdsx.

F or M factors have been identified as the tra or tra2 gene in several insect species, and these factors directly regulated the dsx gene [25, 50]. Previous reports concluded that BmPSI could directly bind Bmdsx pre-mRNA and that the BmImpM product increased BmPSI RNA binding activity in vitro [32]. Mutations of DmPSI in D. melanogaster strongly affect 43 splicing events and DmImp is one of the downstream genes targeted by it [51, 52]. We found that BmImp and BmImpM had minor effects on BmdsxF splicing in our molecular genetic analyses. Furthermore, BmPSI did regulate expression of Bmdsx, BmImpM and BmMasc in vivo. It is unknown how BmPSI regulates the splicing of Bmdsx and other potential splicing factors involved in this process. Nonetheless, these data support the conclusion that BmPSI is at least a key auxiliary factor in the silkworm male sexual differentiation gene cascade, and provide the basis for the hypothesis that the BmPSI gene has a major initial role in the sex determination cascade.

Materials and Methods

Silkworm strains

Silkworms of the same genetic background (Nistari, a multivoltine, nondiapausing strain) were used in all experiments. Wild-type (WT) and mutant larvae were reared on fresh mulberry leaves under standard conditions [53].

Plasmid construction and germline transformation

A binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system was established to target selected genes. The piggyBac-based plasmid, pBac[IE1-EGFP-nos-Cas9] (nos-Cas9), was constructed to express the Cas9 nuclease in germ-line cells under the control of the B. mori nanos (nos) promoter with the EGFP fluorescence marker gene under the control of the IE1 promoter. The plasmid pBac[IE1-DsRed2-U6-sgRNA] (U6-sgRNA) was constructed to express single guide RNAs (sgRNA) under the control of the silkworm U6 promoter and the DsRed fluorescence marker gene also under control of the IE1 promoter. The sgRNAs targeting sequences were designed by manually searching genomic regions that match the 5′-GG-N18-NGG-3′ rule [54]. sgRNA sequences were checked bioinformatically for potential off-target binding using CRISPRdirect (http://crispr.dbcls.jp/) by performing exhaustive searches against silkworm genomic sequences [55]. All sgRNA and oligonucleotide primer sequences for plasmid construction are listed in S2 Table. U6-dsx-sgRNA line from our previous report [56]. Each nos-cas9 or U6-sgRNA plasmid mixed with a piggyBac helper plasmid [53] was microinjected separately into fertilized eggs at the preblastoderm stage. G0 adults were mated to WT moths, and resulting G1 progeny scored for the presence of the marker gene product using fluorescence microscopy (Nikon AZ100) (S1 Table).

Genotyping and phenotypic analysis

Each U6-sgRNA transgenic line was mated individually with the nos-Cas9 line to derive mutated F0 animals. Genomic DNA of mutated animals was extracted at the embryonic or larval stage using standard SDS lysis-phenol treatment after incubation with proteinase K, followed by RNase treatment and purification. The resulting individual DNA samples from mutant animals were separated by sex using gene amplification with primers specific to the W chromosome (S2 Table). For two sgRNA sites, mutation events were detected by amplification using gene-specific primers which set on the upstream or downstream of the each target (S2 Table). Amplified products were visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis running 30 min at 100V. Amplicons were sub-cloned into the pJET-1.2 vector (Fermentas) and the positive clones of each we pick six were sequenced. For the one sgRNA, a restriction enzyme (HpyAV, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) cutting site adjacent to the AGG (PAM sequence) was selected to analyze the putative mutations by restriction enzyme digestion (RED) assay. The RED assay was carried out as previous report [57].

Phenotypic analysis focused light-microscope examination of the morphology of secondary sexual characteristics including internal and external genitalia. Photographs were taken with NRK-D90 (B) or DS-Ri1 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) digital cameras. Testes or ovaries were dissected from fourth-day, fifth-instar larvae and fixed overnight in Qurnah’s solution (anhydrous ethanol: acetic acid: chloroform = 6:1:3v/v/v). Tissues were dehydrated, cleared three times using anhydrous ethanol and xylene, respectively, and embedded in the paraffin overnight. Tissue sections (8 μm) were cut (Leica; RM2235) and stained using a mixture of hematoxylin and eosin solution. All pictures were taken under a microscope (Olympus BX51) using differential interference contrast with the appropriate filter.

Qualitative and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from silkworm at different stages using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase-free DNAse I (Ambion). cDNAs were synthesized using the Omniscript Reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen) in a 20 μl reaction mixture containing 1 μg total RNA. RT-PCR reactions were carried out using KOD plus polymerase (Toyobo) with gene-specific primers (S2 Table). Amplification of the B. mori ribosomal protein 49 (Bmrp49) was used as a positive control.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Q-RT-PCR) assays were performed using SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on an Eppendorf Real-time PCR System Mastercycler realplex (Eppendorf). Q-RT-PCR reactions were carried out with gene-specific primers (S2 Table). A 10-fold serial dilution of pooled cDNA was used as the template to make standard curves. Quantitative mRNA measurements were performed in three independent biological replicates and normalized to Bmrp49 mRNA.

Statistics

Experimental data were analyzed with the Student’s t-test. t-test: *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01,***, p < 0.001. At least three independent replicates were used for each treatment and the error bars show means ± S.E.M.

Supporting Information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmSxl gene. Exons are shown as boxes. Untranslated regions are shown as black boxes and coding regions as open boxes. Thin lines represent the intron and numbers are the lengths in kilobase-pairs (kb). Target site locations are noted and PAM sequences are shown in red. (B) The binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system in this study contains two lines, one contains the full Cas9 ORF driven by the nanos (nos) promoter, and another contains one U6 promoter-driven sgRNA. These two lines also have the reporter genes EGFP or DsRed2, respectively, under the control of the IE1 promoter. (C) RED analysis in the WT and Bmsxl male and female mutants. (D) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmSxl-sgRNA strains. The targeting sequence is in blue and PAM sequence in red. The deletion size is indicated by the number of base pairs (bp).

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the Bmtra2 gene. (B) The binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting Bmtra2. (C) PCR analysis of Bmtra2 male and female mutants. (D) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6- Bmtra2-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmMasc gene. (B) PCR analysis of BmMasc male and female mutants. (C) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmMasc-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

(A) and (D) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the Imp gene. (B) and (E) PCR analysis of BmImp and BmImpM male and female mutants. (C) and (F) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmImp-sgRNA or U6-BmImpM-sgRNA strains, respectively.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmPSI gene. (B) PCR analysis of BmPSI male and female mutants. (C) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmPSI-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

The longer transcript (BmdsxM-L) contains an 81bp fragment between the exon1 and exon2.

(TIF)

RT-PCR amplification the exon1 of Bmdsx from different sexes of WT and mutant animals. Three male or female Bmtra2 mutants were used (1–3). The lower panel shows amplification of the rp49 transcript.

(TIF)

The white bars indicate wild type females and the dot bars indicate wild type males. The results are expressed as the means±SD of three independent biological replicates.

(TIF)

(A-C) Relative mRNA expression levels of BmPSI, BmImpM and BmMasc in BmPSI mutant males and females at the embryonic (144 h after post-oviposition), larval (third day of fifth larvae instar) and pupal (the third day) stages, respectively. The white bars indicate wild type females and the dot bars indicate wild type males. The purple bars indicate mutant females and the dot bars with purple indicate mutant males. Three individual biological replicates were performed in q-RT-PCR. Error bar: SD; *, ** and *** represented significant differences at the 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 level (t-test) compared with the control. (D) PCR-based gene amplification analyses for Bmdsx splicing in BmPSI mutant animals. BmdsxF and BmdsxM represent the female- and male-specific splicing isoforms of Bmdsx, respectively. The lower panel shows amplification of the rp49 transcript, which serves as an internal control for RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Martin Beye and Zhijian Jake Tu for improving this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB11010600) and the National Science Foundation of China (31420103918, 31530072, 31372257 and 31572330). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Murray SM, Yang SY, Van Doren M (2010) Germ cell sex determination: a collaboration between soma and germline. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 722–729. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gempe T, Beye M (2011) Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. Bioessays 33: 52–60. 10.1002/bies.201000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson JW, Quintero JJ (2007) Indirect effects of ploidy suggest X chromosome dose, not the X:A ratio, signals sex in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 5: e332 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González AN, Lu H, Erickson JW (2008) A shared enhancer controls a temporal switch between promoters during Drosophila primary sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:18436–18441. 10.1073/pnas.0805993105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham PL, Yanowitz JL, Penn JK, Deshpande G, Schedl P (2011) The translation initiation factor eIF4E regulates the sex-specific expression of the master switch gene Sxl in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet 7: e1002185 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashiyama K, Hayashi Y, Kobayashi S (2011) Drosophila Sex lethal gene initiates female development in germline progenitors. Science 333: 885–888. 10.1126/science.1208146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson ML, Nagengast AA, Salz HK (2010) PPS, a large multidomain protein, functions with sex-lethal to regulate alternative splicing in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 6: e1000872 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappes G, Deshpande G, Mulvey BB, Horabin JI, Schedl P (2011) The Drosophila Myc gene, diminutive, is a positive regulator of the Sex-lethal establishment promoter, Sxl-Pe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 1543–1548. 10.1073/pnas.1017006108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lott SE, Villalta JE, Schroth GP, Luo S, Tonkin LA, Eisen MB (2011) Noncanonical compensation of zygotic X transcription in early Drosophila melanogaster development revealed through single-embryo RNA-seq. PLoS Biol 9(2): e1000590 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicoso B, Bachtrog D (2013) Reversal of an ancient sex chromosome to an autosome in Drosophila. Nature 499: 332–335. 10.1038/nature12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siera SG, Cline TW (2008) Sexual back talk with evolutionary implications: stimulation of the Drosophila sex-determination gene sex-lethal by its target transformer. Genetics 180: 1963–1981. 10.1534/genetics.108.093898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans DS, Cline TW (2013) Drosophila switch gene Sex-lethal can bypass its switch-gene target transformer to regulate aspects of female behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: E4474–4481. 10.1073/pnas.1319063110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhulst EC, van de Zande L, Beukeboom LW (2010) Insect sex determination: it all evolves around transformer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20: 376–383. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gempe T, Beye M (2011) Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. Bioessays 33: 52–60. 10.1002/bies.201000043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hediger M, Henggeler C, Meier N, Perez R, Saccone G, et al. (2010) Molecular characterization of the key switch F provides a basis for understanding the rapid divergence of the sex-determining pathway in the housefly. Genetics 184: 155–170. 10.1534/genetics.109.109249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willhoeft U, Franz G (1996) Identification of the sex-determining region of the Ceratitis capitata Y chromosome by deletion mapping. Genetics 144: 737–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pane A, Salvemini M, Delli Bovi P, Polito C, Saccone G (2002) The transformer gene in Ceratitis capitata provides a genetic basis for selecting and remembering the sexual fate. Development 129(15): 3715–3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pane A, De Simone A, Saccone G, Polito C (2005) Evolutionary conservation of Ceratitis capitata transformer gene function. Genetics 171: 615–624. 10.1534/genetics.105.041004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saccone G, Salvemini M, Polito LC (2011) The transformer gene of Ceratitis capitata: a paradigm for a conserved epigenetic master regulator of sex determination in insects. Genetica 139: 99–111. 10.1007/s10709-010-9503-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beye M, Hasselmann M, Fondrk MK, Page RE, Omholt SW (2003) The gene csd is the primary signal for sexual development in the honeybee and encodes an SR-type protein. Cell 114: 419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasselmann M, Gempe T, Schiøtt M, Nunes-Silva CG, Otte M, et al. (2008) Evidence for the evolutionary nascence of a novel sex determination pathway in honeybees. Nature 454: 519–522. 10.1038/nature07052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shukla JN, Palli SR (2012) Sex determination in beetles: production of all male progeny by parental RNAi knockdown of transformer. Sci Rep 2: 602 10.1038/srep00602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verhulst EC, Beukeboom LW, van de Zande L (2010) Maternal control of haplodiploid sex determination in the wasp Nasonia. Science 328: 620–623. 10.1126/science.1185805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Concha C, Scott MJ (2009) Sexual development in Lucilia cuprina (Diptera, Calliphoridae) is controlled by the transformer gene. Genetics 182: 785–798. 10.1534/genetics.109.100982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall AB, Basu S, Jiang X, Qi Y, Timoshevskiy VA, et al. (2015) A male-determining factor in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science 348: 1268–1270. 10.1126/science.aaa2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagaraju J, Gopinath G, Sharma V, Shukla JN (2014) Lepidopteran sex determination: a cascade of surprises. Sex Dev 8: 104–112. 10.1159/000357483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bull JJ. Evolution of Sex Determining Mechanisms. Menlo Park, California: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia Q, Zhou Z, Lu C, Cheng D, Dai F, et al. (2004) A draft sequence for the genome of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori). Science 306: 1937–1940. 10.1126/science.1102210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki MG, Ohbayashi F, Mita K, Shimada T (2001) The mechanism of sex-specific splicing at the doublesex gene is different between Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 31: 1201–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki MG, Imanishi S, Dohmae N, Nishimura T, Shimada T, et al. (2008) Establishment of a novel in vivo sex-specific splicing assay system to identify a trans-acting factor that negatively regulates splicing of Bombyx mori dsx female exons. Mol Cell Biol 28: 333–343 10.1128/MCB.01528-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Zhao M, Li D, Zha X, Xia Q, et al. (2009) BmHrp28 is a RNA-binding protein that binds to the female-specific exon 4 of Bombyx mori dsx pre-mRNA. Insect Mol Biol 18: 795–803. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki MG, Imanishi S, Dohmae N, Asanuma M, Matsumoto S (2010) Identification of a male-specific RNA binding protein that regulates sex-specific splicing of Bmdsx by increasing RNA binding activity of BmPSI. Mol Cell Biol 30: 5776–5786. 10.1128/MCB.00444-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki MG, Kobayashi S, Aoki F (2014) Male-specific splicing of the silkworm Imp gene is maintained by an autoregulatory mechanism. Mech Dev 131: 47–56. 10.1016/j.mod.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki MG (2010) Sex determination: insights from the silkworm. J Genet 89: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiuchi T, Koga H, Kawamoto M, Shoji K, Sakai H, et al. (2014) A single female-specific piRNA is the primary determiner of sex in the silkworm. Nature 509: 633–636. 10.1038/nature13315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nissen I, Müller M, Beye M (2012) The Am-tra2 gene is an essential regulator of female splice regulation at two levels of the sex determination hierarchy of the honeybee. Genetics 192: 1015–1026. 10.1534/genetics.112.143925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shukla JN, Palli SR (2013) Tribolium castaneum Transformer-2 regulates sex determination and development in both males and females. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 43(12): 1125–1132. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boggs RT, Gregor P, Idriss S, Belote JM, McKeown M. (1987) Regulation of sexual differentiation in D. melanogaster via alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene. Cell 50: 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Klein J, Nei M (2014) Evolution of the sex-lethal gene in insects and origin of the sex-determination system in Drosophila. J Mol Evol 78: 50–65. 10.1007/s00239-013-9599-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niimi T, Sahara K, Oshima H, Yasukochi Y, Ikeo K, et al. (2006) Molecular cloning and chromosomal localization of the Bombyx Sex-lethal gene. Genome 49: 263–268. 10.1139/g05-108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bessonov S, Anokhina M, Will CL, Urlaub H, Lührmann R (2008) Isolation of an active step I spliceosome and composition of its RNP core. Nature 452: 846–850. 10.1038/nature06842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nilsen TW, Graveley BR (2010) Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 463: 457–463. 10.1038/nature08909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belote JM, Baker BS (1983) The dual functions of a sex determination gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol 95: 512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki MG, Suzuki K, Aoki F, Ajimura M (2012) Effect of RNAi-mediated knockdown of the Bombyx mori transformer-2 gene on the sex-specific splicing of Bmdsx pre-mRNA. Int J Dev Biol 56: 693–699. 10.1387/ijdb.120049ms [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoiber MH, Olson S, May GE, Duff MO, Manent J, et al. (2015) Extensive cross-regulation of post-transcriptional regulatory networks in Drosophila. Genome Res 25: 1692–702. 10.1101/gr.182675.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakai H, Sakaguchi H, Aoki F, Suzuki MG (2015) Functional analysis of sex-determination genes by gene silencing with LNA-DNA gapmers in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mech Dev 137: 45–52. 10.1016/j.mod.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munro TP, Kwon S, Schnapp BJ, St Johnston D (2006) A repeated IMP-binding motif controls oskar mRNA translation and anchoring independently of Drosophila melanogaster IMP. J Cell Biol 172: 577–88. 10.1083/jcb.200510044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boylan KL, Mische S, Li M, Marqués G, Morin X, et al. (2008) Motility screen identifies Drosophila IGF-II mRNA-binding protein—zipcode-binding protein acting in oogenesis and synaptogenesis. PLoS Genet 4: e36 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen TV, Hammer NA, Nielsen J, Madsen M, Dalbaeck C, et al. (2004) Dwarfism and impaired gut development in insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein 1-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol 24: 4448–4464. 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4448-4464.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verhulst EC, van de Zande L, Beukeboom LW (2010) Insect sex determination: it all evolves around transformer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20: 376–383. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labourier E, Blanchette M, Feiger JW, Adams MD, Rio DC (2002) The KH-type RNA-binding protein PSI is required for Drosophila viability, male fertility, and cellular mRNA processing. Genes Dev 16: 72–84. 10.1101/gad.948602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blanchette M, Green RE, Brenner SE, Rio DC (2005) Global analysis of positive and negative pre-mRNA splicing regulators in Drosophila. Genes Dev 19: 1306–1314. 10.1101/gad.1314205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan A, Fu G, Jin L, Guo Q, Li Z, et al. (2013) Transgene-based female-specific lethality system for genetic sexing of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 6766–6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Li Z, Xu J, Zeng B, Ling L, et al. (2013) The CRISPR/Cas System mediates efficient genome engineering in Bombyx mori. Cell Res 23: 1414–1416. 10.1038/cr.2013.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naito Y, Hino K, Bono H, Ui-Tei K (2015) CRISPRdirect: software for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNA with reduced off-target sites. Bioinformatics 31: 1120–1123. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J, Zhan S, Chen S, Zeng B, Li Z, James AA, Tan A, Huang Y (2017) Sexually dimorphic traits in the silkworm, Bombyx mori, are regulated by doublesex. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 80: 42–51. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu GH, Xu J, Cui Z, Dong XT, Ye ZF, et al. (2016) Functional characterization of SlitPBP3 in Spodoptera litura by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 75: 1–9. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmSxl gene. Exons are shown as boxes. Untranslated regions are shown as black boxes and coding regions as open boxes. Thin lines represent the intron and numbers are the lengths in kilobase-pairs (kb). Target site locations are noted and PAM sequences are shown in red. (B) The binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system in this study contains two lines, one contains the full Cas9 ORF driven by the nanos (nos) promoter, and another contains one U6 promoter-driven sgRNA. These two lines also have the reporter genes EGFP or DsRed2, respectively, under the control of the IE1 promoter. (C) RED analysis in the WT and Bmsxl male and female mutants. (D) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmSxl-sgRNA strains. The targeting sequence is in blue and PAM sequence in red. The deletion size is indicated by the number of base pairs (bp).

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the Bmtra2 gene. (B) The binary transgenic CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting Bmtra2. (C) PCR analysis of Bmtra2 male and female mutants. (D) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6- Bmtra2-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmMasc gene. (B) PCR analysis of BmMasc male and female mutants. (C) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmMasc-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

(A) and (D) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the Imp gene. (B) and (E) PCR analysis of BmImp and BmImpM male and female mutants. (C) and (F) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmImp-sgRNA or U6-BmImpM-sgRNA strains, respectively.

(TIF)

(A) Schematic representation of the exon/intron boundaries of the BmPSI gene. (B) PCR analysis of BmPSI male and female mutants. (C) Various mutations were induced in F0 founder animals following crosses between nos-Cas9 and U6-BmPSI-sgRNA strains.

(TIF)

The longer transcript (BmdsxM-L) contains an 81bp fragment between the exon1 and exon2.

(TIF)

RT-PCR amplification the exon1 of Bmdsx from different sexes of WT and mutant animals. Three male or female Bmtra2 mutants were used (1–3). The lower panel shows amplification of the rp49 transcript.

(TIF)

The white bars indicate wild type females and the dot bars indicate wild type males. The results are expressed as the means±SD of three independent biological replicates.

(TIF)

(A-C) Relative mRNA expression levels of BmPSI, BmImpM and BmMasc in BmPSI mutant males and females at the embryonic (144 h after post-oviposition), larval (third day of fifth larvae instar) and pupal (the third day) stages, respectively. The white bars indicate wild type females and the dot bars indicate wild type males. The purple bars indicate mutant females and the dot bars with purple indicate mutant males. Three individual biological replicates were performed in q-RT-PCR. Error bar: SD; *, ** and *** represented significant differences at the 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 level (t-test) compared with the control. (D) PCR-based gene amplification analyses for Bmdsx splicing in BmPSI mutant animals. BmdsxF and BmdsxM represent the female- and male-specific splicing isoforms of Bmdsx, respectively. The lower panel shows amplification of the rp49 transcript, which serves as an internal control for RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.