Abstract

TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate), a well-known activator of protein kinase C (PKC), can experimentally induce reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in certain latently infected cells. We selectively blocked the activity of PKC isoforms by using GF 109203X or rottlerin and demonstrated that this inhibition largely decreased lytic KSHV reactivation by TPA. Translocation of the PKCδ isoform was evident shortly after TPA stimulation. Overexpression of the dominant-negative PKCδ mutant supported an essential role for the PKCδ isoform in virus reactivation, yet overexpression of PKCδ alone was not sufficient to induce lytic reactivation of KSHV, suggesting that additional signaling molecules participate in this pathway.

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8, is causally implicated in KS, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL; also known as body cavity-based lymphoma), and a subset of multicentric Castleman's disease (1, 10, 47, 48). Like all other herpesviruses, primary infection with KSHV precedes lifelong latent infection, while virus reactivation may occur and lead to an increased risk for disease development (21). Only a few viral proteins are expressed during KSHV latency, whereas extensive KSHV genome expression and productive viral DNA replication characterize the lytic phase of virus infection (19, 29, 43, 46). Detection of KSHV in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and KSHV seropositivity are strongly predictive of the development of KS, whereas active replication of KSHV in circulating lymphoid cells is likely responsible for the spread of virus to the endothelium and the onset of KS (8, 51, 62). Relatively little is presently known about the host and cellular factors that can affect and play a role in the intracellular signaling pathways of virus reactivation.

Major tools for studying KSHV biology are latently infected B-cell lines, derived from patients with PEL, in which the virus undergoes spontaneous lytic reactivation in a small steady fraction of the cells (44, 46). Increased, but limited, virus reactivation is observed following exposure of these cell lines to a variety of stimuli such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) (9, 11, 52) and gamma interferon (9), hypoxic conditions (16), coinfection by another viral agent (27, 36, 57), and treatment with chemical reagents such as n-butyrate (37), ionomycin (9, 67), 5-azacytidine (12), and the potent protein kinase C (PKC) activator 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (39, 44). In addition, ectopic expression of the KSHV lytic replication and transcription activator (KSHV/Rta), encoded by viral open reading frame (ORF) 50, is generally sufficient to disrupt virus latency and induce lytic virus reactivation (33, 61). Thus, it is likely that at least part of the effect of agents that activate the virus lytic cycle is through the transcriptional and posttranscriptional activation of this gene; yet, the upstream signaling cascades that influence the expression of KSHV/Rta have not been fully elucidated (7, 12, 22, 26, 32, 33, 41, 61).

The PKC family, comprised of 12 structurally related lipid-regulated serine-threonine kinases, plays a central role in the transduction of a variety of signals that affect cellular functions and proliferation (45). Diacylglycerols (DAG) and calcium ions are the naturally occurring activators of certain members of this family. Phorbol esters, such as TPA, compete with DAG for the same binding site and function as potent PKC agonists (2, 17, 49). Yet, nonkinase DAG and phorbol ester receptors, such as the Ras guanyl releasing protein (RasGRP) and chimaerins, have also been described previously (18, 45, 55).

Our study was designed to determine the role of PKC in KSHV lytic reactivation by TPA and to identify specific PKC isoforms that contribute to the disruption of the latency of KSHV and to virus reactivation. We demonstrate that the activity of PKCδ is required, yet not sufficient, for TPA-mediated virus reactivation.

Selective inhibitors of PKC isoforms inhibit KSHV lytic reactivation.

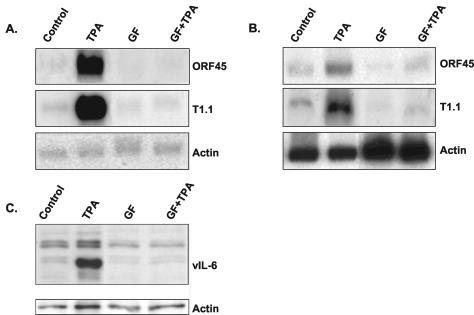

To establish the role of PKC in KSHV lytic reactivation, we investigated the effects of selective PKC inhibitors in PEL-derived KSHV-infected BCP-1 (5) and BCBL-1 (44) cell lines. These experiments were crucial, since not all phorbol ester responses can be attributed to the activities of PKC isoforms (45). As previously reported, we obtained KSHV lytic reactivation after TPA stimulation (39, 44, 46). This was evident by the induction of the expression of the immediate-early KSHV/ORF45 transcript (66), the T1.1 early transcript (65), and the early lytic protein viral IL-6 (vIL-6) (38) 24 h after stimulation (Fig. 1). Inhibition of the TPA-mediated virus reactivation was evident when 5 μM GF 109203X (bisindolylmaleimide I) (56), which inhibits the PKC α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ isoforms (31), was added 30 min prior to the addition of TPA.

FIG. 1.

Effect of TPA and inhibitor of PKC on KSHV reactivation. Northern blot hybridizations with T1.1 and KSHV/ORF45 probes of total RNA extracted from BCP-1 (A) and BCBL-1 (B) cells 24 h after treatment. Cells were subcultured at 2 × 105 cells per milliliter, incubated overnight, and exposed to 20 ng of TPA (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, Mo.)/ml or 5 μM GF 109203X (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) for 24 h or exposed to 5 μM GF 109203X for 30 min before the addition of TPA for 24 h. Untreated cells were used as controls. The GAPDH transcript was analyzed as a control for equal RNA loading. Protein extracts were prepared from BCP-1 cells, and equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were loaded per lane. Following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose, blots were probed for vIL-6 by Western blot analysis. Actin antibody was used to control for equal loading (C). The results shown are representative of those from three similar experiments.

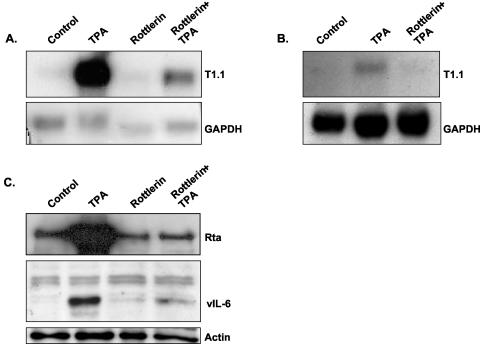

To further evaluate the role of PKC in TPA stimulation of KSHV reactivation, we treated the cells with 5 μM rottlerin, a selective inhibitor of PKCδ (24). Results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that rottlerin largely reduced the TPA-dependent induction of KSHV in BCP-1 and BCBL-1 cells, suggesting an essential role for PKCδ activity in virus reactivation. Of note, we monitored possible toxic effects of the pharmacological treatments by cell cycle analysis with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter and found that treatment with rottlerin alone induced high levels of cell death in BCBL-1 but not in BCP-1 cells, whereas combined treatment with rottlerin and TPA avoided this response (data not shown). This effect probably reflects the nonspecific activity of rottlerin.

FIG. 2.

Effect of the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin on TPA-dependent virus lytic induction. Cells were pretreated with 5 μM rottlerin (Calbiochem) for 30 min followed by 24 h of treatment with 20 ng of TPA/ml. RNA extracts from BCP-1 (A) and BCBL-1 (B) cells were then analyzed for the T1.1 early transcript by Northern blot hybridization, and protein extracts from BCP-1 cells were assayed for the expression of KSHV/Rta and vIL-6 by Western blot analysis (C). As shown, TPA induced virus reactivation, whereas pretreatment with rottlerin inhibited the TPA-induced virus reactivation. The results shown are representative of those from three similar experiments.

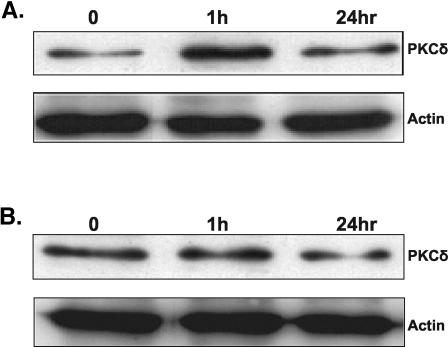

Expression and translocation of PKCδ prior to and after the addition of TPA.

To further study the possible involvement of the PKCδ isoform in TPA-induced lytic reactivation of KSHV, we examined the effect of TPA stimulation on the expression and translocation of PKCδ. These experiments were necessary since prolonged exposure to TPA is known to induce down-regulation of the classical and novel PKC isoforms (45) and translocation of PKC is characteristic of PKC activation (6, 45). We detected expression of PKCδ in both cell lines (Fig. 3A and B) while an elevated level of expression was noted in BCP-1 cells 1 h after TPA stimulation. The cellular localization varied between cell lines, yet transient translocation of PKCδ was evident upon TPA stimulation both in BCP-1 and BCBL-1 cells (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG. 3.

Expression and translocation of PKCδ in BCP-1 and BCBL-1 cells that were treated with TPA. The expression of the PKCδ isoform was examined by using anti-human PKCδ (nPKCδ C-20; Santa Cruz) rabbit polyclonal immunoglobulin G in protein extracts from BCP-1 (A) and BCBL-1 (B) cells growing under standard growth conditions and from cells that were treated with TPA for 30 min, 60 min, and 24 h. The membrane was then probed with antiactin antibody. Fixed BCP-1 (C) and BCBL-1 (D) cells were incubated with rabbit anti-PKCδ antibody followed by an anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate. Propidium iodide (PI) staining was used to mark nuclei. Cells were visualized by confocal microscopy (Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal scan head mounted on a Nikon microscope). The results are from one of three similar experiments.

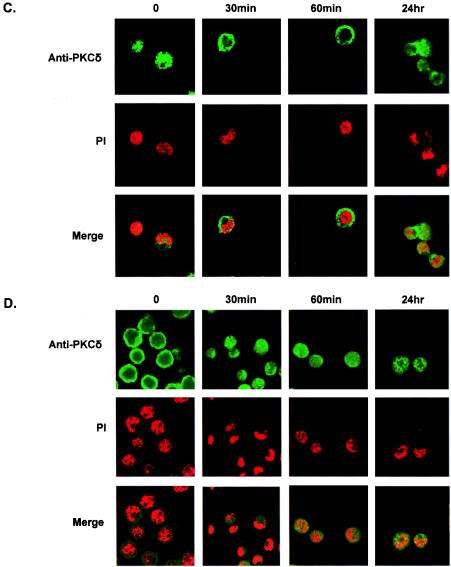

Ectopic expression of dominant-negative PKCδ inhibits TPA-mediated KSHV reactivation.

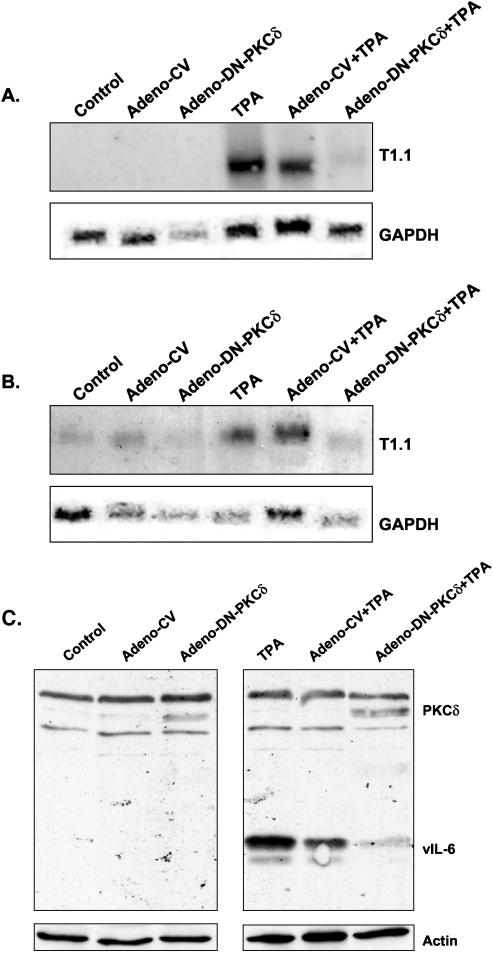

Though rottlerin has been widely used to study the role of PKCδ (14, 34, 64), some questions about the use of this compound have been raised recently (15, 30, 35, 54). Therefore, we further explored the role of PKCδ in virus lytic reactivation by employing recombinant adenoviral vectors (28) to transiently overexpress a mouse kinase-defective K376R PKCδ mutant (4). Overexpression of the transduced gene was confirmed by Western blot analysis with antibodies to the PKCδ that barely recognize the human isoform (nPKCδ rabbit polyclonal immunoglobulin G; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). In accord with the findings obtained with rottlerin, expression of the dominant-negative PKCδ mutant largely inhibited KSHV lytic reactivation (Fig. 4). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that KSHV lytic reactivation by TPA depends to a large extent on the activity of PKCδ.

FIG. 4.

Dominant-negative PKCδ expressed by an adenovirus vector inhibits TPA-mediated KSHV reactivation. Cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus vector that expresses dominant-negative PKCδ (Adeno-DN-PKCδ). Twenty-four hours after the adenoviral transduction, cells were either treated with TPA or left untouched. RNA extracts from BCP-1 (A) and BCBL-1 (B) cells were then analyzed for the T1.1 early transcript. Expression of the ectopically expressed mouse dominant-negative PKCδ and vIL-6 was monitored in BCP-1 cells by Western blot analysis 24 h after the addition of TPA (C). Infection with empty adenovirus vector (Adeno-CV) was used as a control. Actin antibody was used to control for equal loading. The results shown are representative of those from three similar experiments.

Ectopic expression of PKCδ does not affect KSHV lytic reactivation.

Based on the findings that inhibition of PKCδ activity by rottlerin or by ectopic expression of the kinase-inactive PKCδ inhibited TPA-mediated KSHV lytic reactivation, we further investigated the role of PKCδ activation in KSHV lytic reactivation. We transduced the PKCδ with a recombinant adenovirus and assayed its effect on virus reactivation in the absence of and following the addition of TPA. Ectopic expression of PKCδ did not induce virus reactivation nor synergize with TPA in the induction of lytic KSHV reactivation. Similar results were obtained with bistratene A, a cyclic polyether toxin that activates PKCδ (23, 58-60) (data not shown).

Taken together, our data suggest the following: (i) PKC is an important mediator in regulating KSHV lytic reactivation after TPA stimulation, (ii) activation of PKCδ is essential for TPA-mediated KSHV lytic reactivation, and (iii) stimulation of PKCδ is not sufficient to induce KSHV lytic reactivation. Our experiments suggest that non-PKC phorbol ester receptors, such as RasGRP and chimaerins, probably do not play a primary role in TPA-mediated virus reactivation; however, this pathway could have a secondary role that has not been explored. Notably, we observed translocation of PKCδ in the majority of cells that were treated with TPA, though virus activation occurs only in a small fraction of the cells (63). This implies that additional cellular molecules may act as rate-limiting factors for virus reactivation. It is also reasonable to assume that methylations, deletions, or rearrangements of key genes on the KSHV genome prevent KSHV reactivation in a subset of cells regardless of the cellular condition. Downstream effectors of PKC in this pathway have yet to be identified. Since PKC activation frequently leads to activation of members of the mitogen-activated protein kinases that can also be activated in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli and stress, one may envision a number of alternative signal transducing pathways that could induce lytic KSHV reactivation. In addition, isoforms of PKC may posttranslationally modulate the DNA-binding and transcriptional activity of KSHV/Rta.

Emerging evidence points to central roles for PKC isoforms during various phases of infection with different viruses. Activation of PKCζ during primary de novo infection has been recently reported to play an essential role during the initial stages of KSHV infection (42). Similarly, the entry of several other enveloped viruses, including rhabdoviruses, alphaviruses, poxviruses, adenoviruses, and influenza virus, has been proposed to require the activity of PKC (13, 50). Enhancer activation of the human immunodeficiency virus provirus is affected by PKC (20), and the use of synthetic analogues of DAG in conjunction with highly active antiretroviral therapy has been recently proposed (25). Infection with murine cytomegalovirus has been shown to recruit cellular PKC for phosphorylation and dissolution of the nuclear lamina (40). Alternatively, during infection, viruses may target PKC isoforms, which may in turn alter the natural functions of the infected cells (3, 53, 68). Thus, the variable effects of PKC on a range of signal transduction pathways may alter the outcomes of virus exposure and infection both in vitro and in vivo. This may also provide, in the future, a potential therapeutic means to interfere with the consequence of virus infection. As the distinct characteristics attributed to the various PKC isoforms suggest that the composition of PKC isoforms in a particular cell type should determine its cellular response, extensive exploration of the involvement of PKC in KSHV lytic reactivation in a variety of cell types is necessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuan Chang and Patrick Moore for providing cell lines and antibodies to KSHV vIL-6 and Don Ganem for providing antibodies to KSHV/Rta.

This work was supported by the Association for International Cancer Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antman, K., and Y. Chang. 2000. Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1027-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashendel, C. L., J. M. Staller, and R. K. Boutwell. 1983. Protein kinase activity associated with a phorbol ester receptor purified from mouse brain. Cancer Res. 43:4333-4337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann, M., O. Gires, W. Kolch, H. Mischak, R. Zeidler, D. Pich, and W. Hammerschmidt. 2000. The PKC targeting protein RACK1 interacts with the Epstein-Barr virus activator protein BZLF1. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3891-3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blass, M., I. Kronfeld, G. Kazimirsky, P. M. Blumberg, and C. Brodie. 2002. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C δ is essential for its apoptotic effect in response to etoposide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:182-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boshoff, C., S. J. Gao, L. E. Healy, S. Matthews, A. J. Thomas, L. Coignet, R. A. Warnke, J. A. Strauchen, E. Matutes, O. W. Kamel, P. S. Moore, R. A. Weiss, and Y. Chang. 1998. Establishing a KSHV+ cell line (BCP-1) from peripheral blood and characterizing its growth in Nod/SCID mice. Blood 91:1671-1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodie, C., and P. M. Blumberg. 2003. Regulation of cell apoptosis by protein kinase c delta. Apoptosis 8:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, H. J., M. J. Song, H. Deng, T. T. Wu, G. Cheng, and R. Sun. 2003. NF-κB inhibits gammaherpesvirus lytic replication. J. Virol. 77:8532-8540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, T. B., M. Borok, L. Gwanzura, S. MaWhinney, I. E. White, B. Ndemera, I. Gudza, L. Fitzpatrick, and R. T. Schooley. 2000. Relationship of human herpesvirus 8 peripheral blood virus load and Kaposi's sarcoma clinical stage. AIDS 14:2109-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, J., R. Renne, D. Dittmer, and D. Ganem. 2000. Inflammatory cytokines and the reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic replication. Virology 266:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, Y., E. Cesarman, M. S. Pessin, F. Lee, J. Culpepper, D. M. Knowles, and P. S. Moore. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee, M., J. Osborne, G. Bestetti, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 2002. Viral IL-6-induced cell proliferation and immune evasion of interferon activity. Science 298:1432-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, J., K. Ueda, S. Sakakibara, T. Okuno, C. Parravicini, M. Corbellino, and K. Yamanishi. 2001. Activation of latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by demethylation of the promoter of the lytic transactivator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4119-4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constantinescu, S. N., C. D. Cernescu, and L. M. Popescu. 1991. Effects of protein kinase C inhibitors on viral entry and infectivity. FEBS Lett. 292:31-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crosby, D., and A. W. Poole. 2003. Physical and functional interaction between PKCdelta and Fyn tyrosine kinase in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 278:24533-24541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies, S. P., H. Reddy, M. Caivano, and P. Cohen. 2000. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem. J. 351:95-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis, D. A., A. S. Rinderknecht, J. P. Zoeteweij, Y. Aoki, E. L. Read-Connole, G. Tosato, A. Blauvelt, and R. Yarchoan. 2001. Hypoxia induces lytic replication of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Blood 97:3244-3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driedger, P. E., and P. M. Blumberg. 1980. Specific binding of phorbol ester tumor promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:567-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebinu, J. O., D. A. Bottorff, E. Y. Chan, S. L. Stang, R. J. Dunn, and J. C. Stone. 1998. RasGRP, a Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein with calcium- and diacylglycerol-binding motifs. Science 280:1082-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhari, F. D., and D. P. Dittmer. 2002. Charting latency transcripts in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by whole-genome real-time quantitative PCR. J. Virol. 76:6213-6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faulkner, N. E., B. R. Lane, P. J. Bock, and D. M. Markovitz. 2003. Protein phosphatase 2A enhances activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by phorbol myristate acetate. J. Virol. 77:2276-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao, S. J., L. Kingsley, D. R. Hoover, T. J. Spira, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, P. Parry, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gradoville, L., J. Gerlach, E. Grogan, D. Shedd, S. Nikiforow, C. Metroka, and G. Miller. 2000. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 50/Rta protein activates the entire viral lytic cycle in the HH-B2 primary effusion lymphoma cell line. J. Virol. 74:6207-6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths, G., B. Garrone, E. Deacon, P. Owen, J. Pongracz, G. Mead, A. Bradwell, D. Watters, and J. Lord. 1996. The polyether bistratene A activates protein kinase C-delta and induces growth arrest in HL60 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 222:802-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gschwendt, M., H. J. Muller, K. Kielbassa, R. Zang, W. Kittstein, G. Rincke, and F. Marks. 1994. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamer, D. H., S. Bocklandt, L. McHugh, T. W. Chun, P. M. Blumberg, D. M. Sigano, and V. E. Marquez. 2003. Rational design of drugs that induce human immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 77:10227-10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haque, M., D. A. Davis, V. Wang, I. Widmer, and R. Yarchoan. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) contains hypoxia response elements: relevance to lytic induction by hypoxia. J. Virol. 77:6761-6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington, W., Jr., L. Sieczkowski, C. Sosa, S. Sue, J. P. Cai, L. Cabral, and C. Wood. 1997. Activation of HHV-8 by HIV-1 tat. Lancet 349:774-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He, T. C., S. Zhou, L. T. da Costa, J. Yu, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1998. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2509-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenner, R. G., M. M. Alba, C. Boshoff, and P. Kellam. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent and lytic gene expression as revealed by DNA arrays. J. Virol. 75:891-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keenan, C., N. Goode, and C. Pears. 1997. Isoform specificity of activators and inhibitors of protein kinase C gamma and delta. FEBS Lett. 415:101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiss, Z., H. Phillips, and W. H. Anderson. 1995. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X, a selective inhibitor of protein kinase C, does not inhibit the potentiating effect of phorbol ester on ethanol-induced phospholipase C-mediated hydrolysis of phosphatidylethanolamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1265:93-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukac, D. M., L. Garibyan, J. R. Kirshner, D. Palmeri, and D. Ganem. 2001. DNA binding by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic switch protein is necessary for transcriptional activation of two viral delayed early promoters. J. Virol. 75:6786-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukac, D. M., R. Renne, J. R. Kirshner, and D. Ganem. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandil, R., E. Ashkenazi, M. Blass, I. Kronfeld, G. Kazimirsky, G. Rosenthal, F. Umansky, P. S. Lorenzo, P. M. Blumberg, and C. Brodie. 2001. Protein kinase Calpha and protein kinase Cdelta play opposite roles in the proliferation and apoptosis of glioma cells. Cancer Res. 61:4612-4619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGovern, S. L., and B. K. Shoichet. 2003. Kinase inhibitors: not just for kinases anymore. J. Med. Chem. 46:1478-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merat, R., A. Amara, C. Lebbe, H. de The, P. Morel, and A. Saib. 2002. HIV-1 infection of primary effusion lymphoma cell line triggers Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) reactivation. Int. J. Cancer 97:791-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, G., L. Heston, E. Grogan, L. Gradoville, M. Rigsby, R. Sun, D. Shedd, V. M. Kushnaryov, S. Grossberg, and Y. Chang. 1997. Selective switch between latency and lytic replication of Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus and Epstein-Barr virus in dually infected body cavity lymphoma cells. J. Virol. 71:314-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore, P. S., C. Boshoff, R. A. Weiss, and Y. Chang. 1996. Molecular mimicry of human cytokine and cytokine response pathway genes by KSHV. Science 274:1739-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore, P. S., S. J. Gao, G. Dominguez, E. Cesarman, O. Lungu, D. M. Knowles, R. Garber, P. E. Pellett, D. J. McGeoch, and Y. Chang. 1996. Primary characterization of a herpesvirus agent associated with Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Virol. 70:549-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muranyi, W., J. Haas, M. Wagner, G. Krohne, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2002. Cytomegalovirus recruitment of cellular kinases to dissolve the nuclear lamina. Science 297:854-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura, H., M. Lu, Y. Gwack, J. Souvlis, S. L. Zeichner, and J. U. Jung. 2003. Global changes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J. Virol. 77:4205-4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naranatt, P. P., S. M. Akula, C. A. Zien, H. H. Krishnan, and B. Chandran. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus induces the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-PKC-zeta-MEK-ERK signaling pathway in target cells early during infection: implications for infectivity. J. Virol. 77:1524-1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paulose-Murphy, M., N. K. Ha, C. Xiang, Y. Chen, L. Gillim, R. Yarchoan, P. Meltzer, M. Bittner, J. Trent, and S. Zeichner. 2001. Transcription program of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus). J. Virol. 75:4843-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renne, R., W. Zhong, B. Herndier, M. McGrath, N. Abbey, D. Kedes, and D. Ganem. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2:342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ron, D., and M. G. Kazanietz. 1999. New insights into the regulation of protein kinase C and novel phorbol ester receptors. FASEB J. 13:1658-1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarid, R., O. Flore, R. A. Bohenzky, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1998. Transcription mapping of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1). J. Virol. 72:1005-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarid, R., S. J. Olsen, and P. S. Moore. 1999. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: epidemiology, virology, and molecular biology. Adv. Virus Res. 52:139-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schulz, T. F., J. Sheldon, and J. Greensill. 2002. Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8). Virus Res. 82:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharkey, N. A., K. L. Leach, and P. M. Blumberg. 1984. Competitive inhibition by diacylglycerol of specific phorbol ester binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:607-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sieczkarski, S. B., H. A. Brown, and G. R. Whittaker. 2003. Role of protein kinase C betaII in influenza virus entry via late endosomes. J. Virol. 77:460-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith, M. S., C. Bloomer, R. Horvat, E. Goldstein, J. M. Casparian, and B. Chandran. 1997. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 DNA in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions and peripheral blood of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients and correlation with serologic measurements. J. Infect. Dis. 176:84-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song, J., T. Ohkura, M. Sugimoto, Y. Mori, R. Inagi, K. Yamanishi, K. Yoshizaki, and N. Nishimoto. 2002. Human interleukin-6 induces human herpesvirus-8 replication in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line. J. Med. Virol. 68:404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tardif, M., M. Savard, L. Flamand, and J. Gosselin. 2002. Impaired protein kinase C activation/translocation in Epstein-Barr virus-infected monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24148-24154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tillman, D. M., K. Izeradjene, K. S. Szucs, L. Douglas, and J. A. Houghton. 2003. Rottlerin sensitizes colon carcinoma cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis via uncoupling of the mitochondria independent of protein kinase C. Cancer Res. 63:5118-5125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tognon, C. E., H. E. Kirk, L. A. Passmore, I. P. Whitehead, C. J. Der, and R. J. Kay. 1998. Regulation of RasGRP via a phorbol ester-responsive C1 domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6995-7008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toullec, D., P. Pianetti, H. Coste, P. Bellevergue, T. Grand-Perret, M. Ajakane, V. Baudet, P. Boissin, E. Boursier, F. Loriolle, et al. 1991. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 266:15771-15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vieira, J., P. O'Hearn, L. Kimball, B. Chandran, and L. Corey. 2001. Activation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) lytic replication by human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 75:1378-1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watters, D., B. Garrone, G. Gobert, S. Williams, R. Gardiner, and M. Lavin. 1996. Bistratene A causes phosphorylation of talin and redistribution of actin microfilaments in fibroblasts: possible role for PKC-delta. Exp. Cell Res. 229:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watters, D. J., and P. G. Parsons. 1999. Critical targets of protein kinase C in differentiation of tumour cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58:383-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Way, K. J., E. Chou, and G. L. King. 2000. Identification of PKC-isoform-specific biological actions using pharmacological approaches. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 21:181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.West, J. T., and C. Wood. 2003. The role of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus-8 regulator of transcription activation (RTA) in control of gene expression. Oncogene 22:5150-5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitby, D., M. R. Howard, M. Tenant-Flowers, N. S. Brink, A. Copas, C. Boshoff, T. Hatzioannou, F. E. Suggett, D. M. Aldam, A. S. Denton, et al. 1995. Detection of Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus in peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals and progression to Kaposi's sarcoma. Lancet 346:799-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu, F. Y., Q. Q. Tang, H. Chen, C. ApRhys, C. Farrell, J. Chen, M. Fujimuro, M. D. Lane, and G. S. Hayward. 2002. Lytic replication-associated protein (RAP) encoded by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus causes p21CIP-1-mediated G1 cell cycle arrest through CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10683-10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhong, M., Z. Lu, and D. A. Foster. 2002. Downregulating PKC delta provides a PI3K/Akt-independent survival signal that overcomes apoptotic signals generated by c-Src overexpression. Oncogene 21:1071-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong, W., and D. Ganem. 1997. Characterization of ribonucleoprotein complexes containing an abundant polyadenylated nuclear RNA encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8). J. Virol. 71:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu, F. X., T. Cusano, and Y. Yuan. 1999. Identification of the immediate-early transcripts of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 73:5556-5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zoeteweij, J. P., A. V. Moses, A. S. Rinderknecht, D. A. Davis, W. W. Overwijk, R. Yarchoan, J. M. Orenstein, and A. Blauvelt. 2001. Targeted inhibition of calcineurin signaling blocks calcium-dependent reactivation of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Blood 97:2374-2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zrachia, A., M. Dobroslav, M. Blass, G. Kazimirsky, I. Kronfeld, P. M. Blumberg, D. Kobiler, S. Lustig, and C. Brodie. 2002. Infection of glioma cells with Sindbis virus induces selective activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta. Implications for Sindbis virus-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23693-23701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]