ABSTRACT

The UL133–138 locus present in clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes proteins required for latency and reactivation in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and virion maturation in endothelial cells. The encoded proteins form multiple homo- and hetero-interactions and localize within secretory membranes. One of these genes, UL136 gene, is expressed as at least five different protein isoforms with overlapping and unique functions. Here we show that another gene from this locus, the UL138 gene, also generates more than one protein isoform. A long form of UL138 (pUL138-L) initiates translation from codon 1, possesses an amino-terminal signal sequence, and is a type one integral membrane protein. Here we identify a short protein isoform (pUL138-S) initiating from codon 16 that displays a subcellular localization similar to that of pUL138-L. Reporter, short-term transcription, and long-term virus production assays revealed that both pUL138-L and pUL138-S are able to suppress major immediate early (IE) gene transcription and the generation of infectious virions in cells in which HCMV latency is studied. The long form appears to be more potent at silencing IE transcription shortly after infection, while the short form seems more potent at restricting progeny virion production at later times, indicating that both isoforms of UL138 likely cooperate to promote HCMV latency.

IMPORTANCE Latency allows herpesviruses to persist for the lives of their hosts in the face of effective immune control measures for productively infected cells. Controlling latent reservoirs is an attractive antiviral approach complicated by knowledge deficits for how latently infected cells are established, maintained, and reactivated. This is especially true for betaherpesviruses. The functional consequences of HCMV UL138 protein expression during latency include repression of viral IE1 transcription and suppression of virus replication. Here we show that short and long isoforms of UL138 exist and can themselves support latency but may do so in temporally distinct manners. Understanding the complexity of gene expression and its impact on latency is important for considering potential antivirals targeting latent reservoirs.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a betaherpesvirus that causes birth defects and disease in immunocompromised and immunosuppressed patients and has been associated with cancers, cardiovascular disease, and immune dysfunction (1–3). HCMV productively (lytically) infects differentiated cells, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells, and latently infects incompletely differentiated cells of the myeloid lineage, such as monocytes and CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) (4, 5). Productive infection in multiple cell types within the human host facilitates viral dissemination, while latency ensures lifelong persistence despite an effective immune response against lytic-phase antigens. Periodic reactivations of latent infections into the productive phase perpetuate both lifelong infection and virus spread to new hosts. No drugs that target latent reservoirs exist. Antiviral drugs targeting active replication are effective but have deleterious side effects and select for drug-resistant viruses (6).

The development of facile viral genetics (7) permitted the evaluation of viral sequences that are required for, augment, or are dispensable for productive infection of fibroblasts (8). While many of the mechanisms important to productive infection are well understood in fibroblasts (3), the mechanisms critical to latency remain poorly defined. However, in the last decade, an in vitro system to model experimental HCMV latency emerged, permitting genetic (9–15) and molecular (16–18) analyses of latently infected cells. During latency, the expression of productive-phase genes is suppressed. For this suppression to occur, the accumulation of the viral immediate early (IE) proteins that stimulate lytic infection must be controlled. IE protein accumulation is limited during latency by both transcriptional (19–21) and posttranscriptional (22) suppression. Transcriptional suppression of viral IE genes during latency is instituted, in part, by the viral UL138 protein (16).

HCMV UL138 resides within a clustered set of ULb′ genes (UL133, UL135, and UL136 genes) encoding proteins that all localize within secretory membranes, including the Golgi apparatus (12). Genetic analyses indicate that UL135 and some UL136 isoforms are required for efficient productive infection in endothelial cells (23–25) and that UL138, when expressed in the presence of UL133 and UL136 but in the absence of UL135, impairs efficient productive infection of fibroblasts (13). Notably, viruses deficient in UL133, UL138, or the soluble 23-/19-kDa isoforms of UL136 generate many infectious virus progeny in CD34+ hematopoietic cells, whereas wild-type viruses generate few such progeny (11, 12, 15). Molecular studies have revealed that UL135 and UL136 promote cytoplasmic maturation of viral particles in endothelial cells (23, 24), UL135 impairs immune synapse formation (26), and UL138 promotes cell surface expression of the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) receptor (TNFR) (27, 28) as well as impairs cell surface expression of the multidrug resistance-associated protein-1 (MRP1) (18).

During latency, UL138 also promotes the suppression of IE1 gene transcription that is driven by the major immediate early promoter (MIEP). MIEP-directed transcription initiates productive replication in fibroblasts when the viral pp71 protein, a component of the virion tegument delivered upon infection, migrates to the nucleus and degrades Daxx, thereby counteracting histone deacetylase (HDAC)-mediated repression (29). When HCMV infects incompletely differentiated myeloid cells, in which it enters latency, tegument-delivered pp71 remains in the cytoplasm and IE1 transcription is suppressed (20, 21, 30, 31). For high-passage-number laboratory strains, the intrinsic defense instituted by Daxx may be the only significant restriction to IE1 transcription during latency because IE1 transcription from AD169 can be rescued in THP-1 and CD34+ cells (20, 21) by either Daxx knockdown or the HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A (TSA) or valproic acid (VPA). Unlike AD169, low-passage-number strains impose additional restrictions (21), one of which is enacted by UL138. UL138 impairs the recruitment of cellular lysine demethylases (KDMs) to the MIEP, thereby stabilizing repressive epigenetic histone modifications and silencing IE1 transcription (16).

Estimates of the protein-coding capacity of HCMV have substantially increased with recent studies (32, 33) and suggest a complexity in viral protein expression and likely function not previously appreciated. Genomic approaches have also cataloged previously undetected transcribed and translated sequences during both lytic and latent infections (34–37). The UL136 gene described above generates a series of coterminal protein isoforms with both overlapping and distinct functions (9, 15), illustrating the functional impact of previously unrecognized viral coding capacity. Here we show that UL138 gene also produces two coterminal proteins originating from separate in-frame methionine codons that support HCMV latency with different temporal phenotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, infections, and transfections.

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDFs) (Clonetics), human fetal lung fibroblasts (MRC-5) (CCL-171; ATCC), THP-1 monocytes (TIB-202; ATCC), and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (WA01; WiCell) were maintained as previously described (9, 20, 31). Primary human CD34+ cells derived from cord blood were either purchased from Lonza (2C-101) and cultured as previously described (21) or isolated from deidentified donors at the University of Arizona Medical Center and cultured as previously described (38). For infection, cells were incubated with virus in minimal volume for 1 h at 37°C followed by addition of medium to normal culture volumes. Fibroblasts were transfected with 2 μg plasmid DNA per 1 × 106 cells using the Amaxa nucleofection system for primary human fibroblasts (VPI-1002; Lonza), according to the manufacturer's instructions. THP-1 monocytes were transfected with 2.5 μg plasmid DNA per 1 × 106 cells using TransIT-2020 (MIR 5400; Mirus), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

BAC mutagenesis.

A derivative of AD169 expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged UL138 has been previously described (16) and was used to generate additional mutants using a two-step red recombination procedure (39). To create AD169-UL138HA-Δ1–15, amino acids 1 to 15 of UL138 were deleted using the following primers: 5′-GGA TAA ATA GTG CGA TGG CGT TTG TGG GAG AAC GCA GTA GCG ATG CTC GTG CTG ATC GTG GCC TAG GGA TAA CAG GGT AAT CGA TTT-3′ and 5′-GTA AGC TAG ATA GCA GAG AAT GGC CAC GAT CAG CAC GAG CAT CGC TAC TGC GTT CTC CCA CAA GCC AGT GTT ACA ACC AAT TAA CC-3′. To create AD169-UL138HA-M16I, methionine 16 was mutated to an isoleucine using the following primers: 5′-ACG ATC TGC CGC TGA ACG TCG GGT TAC CCA TCA TCG GCG TGA TCC TCG TGC TGA TCG TGG CCA TTC TAG GGA TAA CAG GGT AAT CGA TTT-3′ and 5′-CAA TGG TAA GCT AGA TAG CAG AGA ATG GCC ACG ATC AGC ACG AGG ATC ACG CCG ATG ATG GGT AA GCC AGT GTT ACA ACC AAT TAA CC-3′. A derivative of TB40/E expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) has been previously described (40) and was used to generate additional mutants using a two-step galK-based approach (9). Primers utilized are listed in Table 1. Viruses were recovered by cotransfection of the recombinant bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and a pp71 expression plasmid into fibroblasts.

TABLE 1.

Primers used to construct TB40/E virusesa

| Protocol | Primer name | Orientation | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAC recombineering | ΔUL138<galK> | Forward | GTTCCCGCGCGAGTGCTGTACAAAAGAGAGAGACTGGGACGTAGATCCGGACAGAGGACGGTCACCCCTGTTGACAATTAATCATCGGCA |

| Reverse | GAGTAGATCGAGCAGAGAATGTCAAAACGACATTACCGCGATCCGCTCCCCTCTTTTTTCTTTTTCTCATTCAGCACTGTCCTGCTCCTT | ||

| UL136(bp640) | Forward | GGTACATGTGGCGGTCCAAGC | |

| UL139(−367bp) | Reverse | CCTCACCGTCCATCGTCCG | |

| Phusion mutagenesis | UL1383XFlag | Forward | [Phos]CGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTGAATGAGAAAAAGAAAAAAGAGGGGAGCGGATCGCGG |

| Reverse | [Phos]ATGTCATGATCTTTATAATCACCGTCATGGTCTTTGTAGTCACCGCCACCGCCCGTGTATTCTTG | ||

| UL138-M1A | Forward | [Phos]GACGGTCACCGCGGACGATCTG | |

| Reverse | [Phos]CTCTGTCCGGATCTACGTCCCAGTCTCT | ||

| UL138-M16A | Forward | [Phos]CATCGGCGTGGCGCTCGTGCTG | |

| Reverse | [Phos]ATGGGTAACCCGACGTTCAGCGGCAGAT | ||

| UL138-M40A | Forward | [Phos]ACTGGTGCGCGCGTTTTTGAGC | |

| Reverse | [Phos]TTGAAGGTGTCGTGCCAATGGTAAGC |

[Phos] indicates a 5′ phosphate group.

Inhibitors and antibodies.

When indicated, VPA (1 mM; Sigma) was added 3 h prior to infection of THP-1 cells or at the time of infection of primary CD34+ cells. The following antibodies were from commercial sources: anti-HA (HA.11; Covance), anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; AM4300; Applied Biosystems), anti-tubulin (DM 1A; Sigma), anti-beta actin (ab8226; Abcam), anti-GM130 (catalog number 610822; BD Transduction Laboratories), and anti-Flag (M2; Sigma).

Western blot and indirect immunofluorescence assays.

Cells were lysed in either radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA; Thermo), 1% SDS, or 1× passive lysis (Promega) buffer, and equal amounts of lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Optitran (GE Healthcare) or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF; Millipore) membranes, and analyzed by Western blotting as previously described (9, 30). For indirect immunofluorescence, adherent NHDFs and suspension THP-1 or CD34+ cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, and processed as previously described (20, 21, 29). Images were recorded with a Nikon Confocal Laser Scanning microscope using Prairie View software.

Luciferase assays.

One million THP-1 cells cultured in medium without antibiotics were cotransfected with 20 ng pGL3-MIEP firefly reporter plasmid, 40 ng pRL-TK Renilla reporter plasmid, and 3 μg pSG5-EV (empty vector) or decreasing amounts of pSG5-UL138HA, pSG5-UL138HA-Δ1–15, or pSG5-UL138HA-M16I (3.0 μg, 2.0 μg, 1.0 μg, and 0.25 μg, respectively) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total pSG5 was normalized to 3 μg for each transfection with a pSG5-EV. Medium was changed 24 h posttransfection. Luciferase activity was assayed at 48 h posttransfection using a dual-luciferase reporter system (E1960; Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described (16).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

For transcript analysis, total RNA was isolated using a Total RNA minikit (IB47232; IBI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of total RNA were treated with DNase I (M6101; Promega) and converted to cDNA using the Superscript III first-strand synthesis Supermix for qPCR (11751; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using an ABI7900HT real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and iTaq SYBR green Supermix (catalog number 172-5124; Bio-Rad) with primer sets specific for exon 3 of IE1/IE2 (41) and GAPDH (42). Melting curve analysis confirmed the presence of a single PCR product for each primer set. Data were analyzed with SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems), and viral gene expression was normalized to cellular GAPDH and expressed relative to untreated AD169-infected controls using the ΔΔCT method, where CT is threshold cycle (43). Conventional reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed as previously described (16).

Latency maintenance assays.

Latency maintenance assays in ESCs (16) and CD34+ cells (15) were performed as previously described.

RESULTS

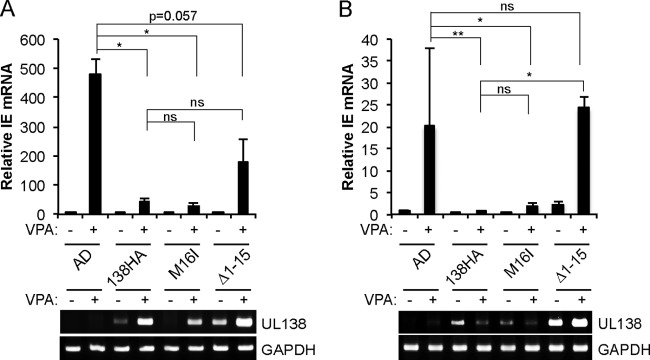

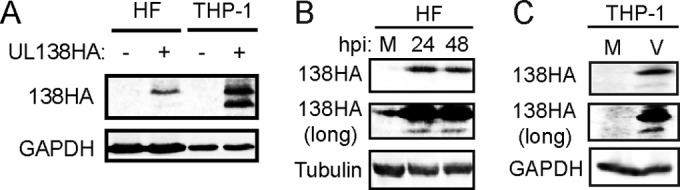

Upon transfection of an expression plasmid carrying a UL138 allele with an added C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag, NHDF lysates contained a single HA-reactive band on Western blots (Fig. 1A) consistent with expression of full-length UL138 (here called pUL138-L for “long”). However, THP-1 lysates (Fig. 1A) contained approximately equimolar levels of this seemingly full-length protein and one of smaller size (here called pUL138-S for “short”). Both pUL138-L and pUL138-S were detected in NHDFs (Fig. 1B) infected with AD-138HA, a laboratory strain AD169-based recombinant (16) expressing C-terminally HA tagged UL138. The steady-state levels of pUL138-S were much lower than those of pUL138-L. We also detected both pUL138-L and pUL138-S in AD-138HA-infected THP-1 cells (Fig. 1C). Once again, pUL138-S accumulated to much lower levels than did pUL138-L. Furthermore, pUL138-S was also detected during infection of MRC5s or THP-1s with a TB40/E clinical strain in which the 3× Flag epitope tag was added to the C terminus of the endogenous UL138 gene (see Fig. 8). Our ability to visualize pUL13-S expression is frustratingly inconsistent (Fig. 1; see also below) due to the low-level expression of the isoform (expected for a latency protein), which hovers near our limits of detection. Various and sundry attempts to increase sensitivity (higher multiplicities of infection [MOIs], new virus preps, different time points, different lysis buffers and protocols, immunoprecipitation [IP]-Western, VPA treatment, stabilization with proteasome inhibitors) have failed to increase the frequency with which pUL138-S is detected (please see Discussion for more details on pUL138-S low-level expression). Nevertheless, because both the long and short forms of pUL138 can be visualized with antibodies to C-terminal epitope tags, and because disruption of the first translation initiation site results in increased accumulation of pUL138-S, we conclude that the UL138 gene is capable of producing two protein isoforms with identical carboxy termini.

FIG 1.

The UL138 gene is expressed as long and short isoforms. (A) Lysates from normal human dermal fibroblasts (HF) or THP-1 cells transfected with an empty vector (−) or with a plasmid expressing C-terminally HA-tagged UL138 (+) were harvested at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. GAPDH serves as a loading control. (B) Lysates from NHDFs mock infected (M) or infected with AD169-UL138HA at an MOI of 1 were collected at the indicated hours postinfection (hpi) and analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. A long exposure is also shown. Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) VPA-treated THP-1 cells were mock infected (M) or infected with AD169-UL138HA (V) at an MOI of 3. At 24 h postinfection, lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. A long exposure is also shown. GAPDH served as a loading control.

FIG 8.

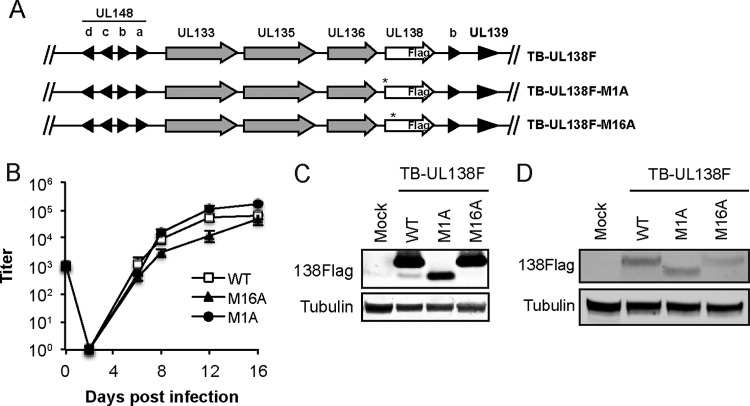

TB40/E-UL138F mutant viruses express pUL138-L or pUL138-S. (A) Schematic of TB-UL138F wild-type, M1A, and M16A viruses. (B) MRC-5 fibroblasts were infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 0.02, and virus accumulated in the cells and medium was quantitated by 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) at the indicated times. Data are the means ± SEM from 3 biological replicates. (C) Lysates from MRC-5 fibroblasts mock infected or infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 2 for 72 h were analyzed by Western blotting with the Flag antibody. Tubulin served as a loading control. (D) Lysates from THP-1 cells mock infected or infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 4 for 72 h were analyzed by Western blotting with the Flag antibody. Tubulin served as a loading control.

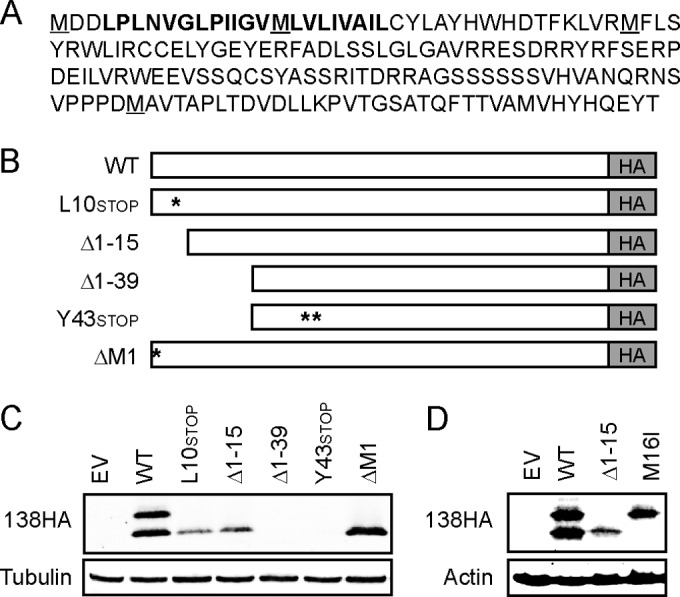

The UL136 gene generates multiple protein isoforms through alternative transcription initiation and, likely, translation initiation from sequential in-frame methionine codons (9, 44). To evaluate the potential transcriptional mechanisms responsible for the expression of two pUL138 isoforms, we used 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) over a time course of infection to detect any transcripts with transcriptional start sites (TSS) within the UL138 coding sequence (cds). Our analyses detected transcripts just upstream of the first methionine codon (M1) of UL138 gene but did not detect transcripts initiating within the UL138 cds (data not shown), consistent with previous data (11, 45) and suggesting that the two pUL138 isoforms may be encoded on every pUL138-specific transcript. The UL138 cds contains four in-frame methionine (M) codons (M1, M16, M40, and M134), the last three of which represent potential start sites for a smaller, coterminal protein (Fig. 2A). As proteins initiating at the final methionine (M134) would seem to be significantly smaller than the observed size of pUL138-S (Fig. 1), we focused a mutagenesis approach (Fig. 2B) on M16 and M40.

FIG 2.

pUL138-S initiates from methionine 16. (A) Amino acid sequence of full-length UL138. Potential in-frame methionine start sites are underlined. Putative transmembrane domain is shown in bold. (B) Schematic of UL138HA mutant alleles in the pSG5 expression vector. (C) Lysates from THP-1 cells transfected with an empty vector (EV) or the indicated UL138HA allele were collected at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. Tubulin served as a loading control. (D) Lysates from THP-1 cells transfected with an empty vector (EV) or plasmids encoding wild-type, Δ1–15, or M16I UL138HA were collected at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. Actin served as a loading control.

Converting codon 10, which normally encodes leucine (L), into a stop codon (L10stop), deleting the first 15 codons (Δ1–15), or deleting codon 1, normally encoding methionine (ΔM1), had no effect on the expression of pUL138-S in transfected THP-1 cells (Fig. 2C). However, converting codon 43, which normally encodes a tyrosine (Y), into a stop codon (Y43stop) abrogated the ability to detect pUL138-S (Fig. 2C), indicating that either M16 or M40 was the potential start site for pUL138-S translation. Because deleting the first 39 codons (Δ1–39) but retaining the M40 codon also abrogated the ability to detect pUL138-S (Fig. 2C), we suspected that translational initiation at M16 was responsible for generating pUL138-S. To directly test this prediction, we generated an allele (M16I) in which codon 16, normally encoding methionine, was changed to one encoding isoleucine (I). The M16I allele generated pUL138-L but not pUL138-S (Fig. 2D). We conclude that pUL138-L initiates from translation at codon M1 and that pUL138-S initiates from translation at codon M16. It remains possible that translational initiation at M40 or even M134 also generates protein. In fact, we have on occasion observed smaller HA-reactive bands on Western blots of lysates from UL138-HA-transfected cells, but those species have not been consistently observed or mapped.

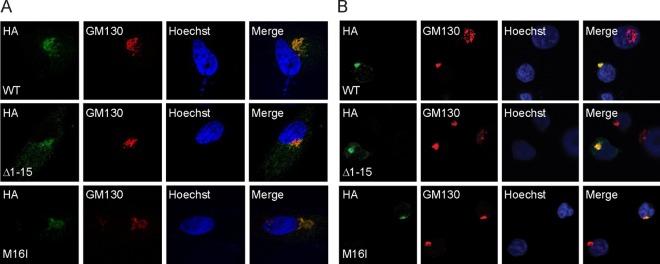

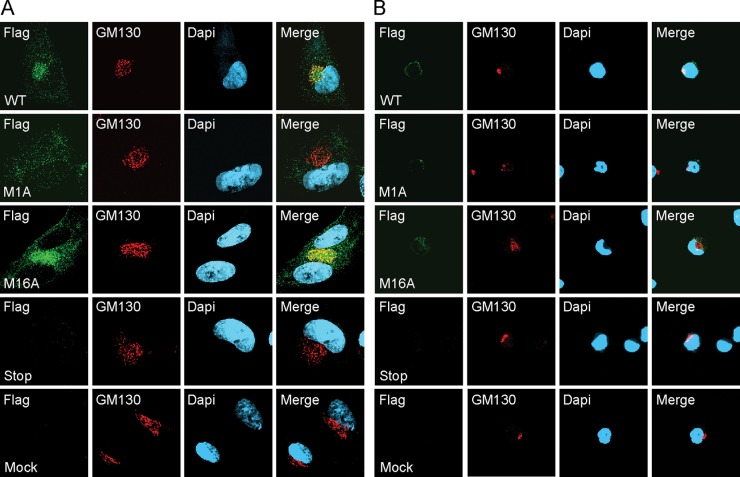

The long form of the UL138 protein contains an amino-terminal signal sequence and a putative transmembrane domain (Fig. 2A) and is a membrane-localized resident of the Golgi apparatus (11). Methionine 16, where translation of the short form begins, is distal to the signal sequence and within the putative transmembrane domain. Therefore, pUL138-S is unlikely to be a transmembrane protein. During transient expression, both pUL138-L and pUL138-S localize to the Golgi apparatus in NHDFs (Fig. 3A) and in THP-1 cells (Fig. 3B), identified by costaining for the Golgi body resident protein (46) golgin A2/Golgi matrix protein (GM) 130 (additional images are provided in Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). In a portion of cells, pUL138-S also showed a more diffuse cytoplasmic localization. We conclude that both pUL138-L and pUL138-S localize to the Golgi apparatus during transient transfection.

FIG 3.

Ectopically expressed pUL138-L and pUL138-S localize to the Golgi apparatus. NHDFs (A) and THP-1 cells (B) were transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type (WT), Δ1–15, or M16I UL138HA virus. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were stained with antibodies against HA and the Golgi body marker GM130 and imaged by indirect immunofluorescence. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst stain.

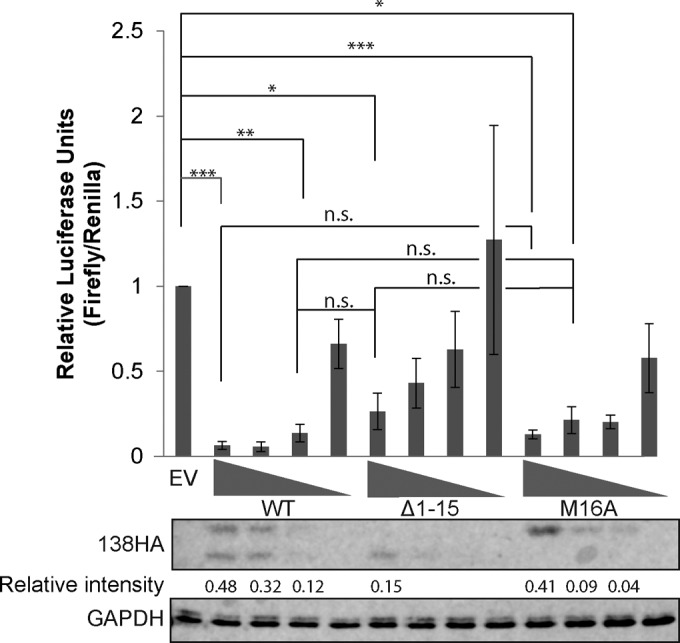

Despite its localization in the Golgi body, UL138 has profound impacts on viral gene expression in the nuclei of latently infected myeloid cells (16), where it silences IE1 transcription by preventing the recruitment of cellular KDMs to the viral MIEP. As an initial test of the individual abilities of pUL138-L and pUL138-S to modulate MIEP function, we used a transient-transfection reporter assay in THP-1 cells. Transfection of different amounts of expression constructs encoding either wild-type UL138 (that makes both pUL138-L and pUL138-S), one encoding only pUL138-S (Δ1–15), or one encoding only pUL138-L (M16I) generated the predicted protein products to differing levels and allowed us to compare how well equivalent levels of protein isoforms could suppress a cotransfected MIEP reporter (Fig. 4). When roughly equivalent levels of proteins were compared, we found no statistical differences in the ability of wild-type UL138, pUL138-S, or pUL138-L to silence the MIEP. We conclude that both pUL138-L and pUL138-S repress an MIEP reporter in THP-1 cells.

FIG 4.

Both pUL138-L and pUL138-S repress an MIEP reporter in THP-1 cells. A luciferase reporter driven by the HCMV MIEP was cotransfected with a control TK-driven Renilla luciferase reporter and either an empty vector (EV) or an expression plasmid for wild-type, Δ1–15, or M16I UL138HA alleles in decreasing amounts from 3 μg to 0.25 μg. Total pSG5 transfected was brought up to 3 μg with pSG5 empty vector. The ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity was determined 48 h posttransfection. Data represent means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from three experiments. Lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Numbers under the 138HA Western blot represent 138HA band intensity when detectable relative to GAPDH intensity as quantified on LiCor Odyssey. Statistical comparisons were done between EV and UL138 isoforms with similar expression levels: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05) by Student's t test.

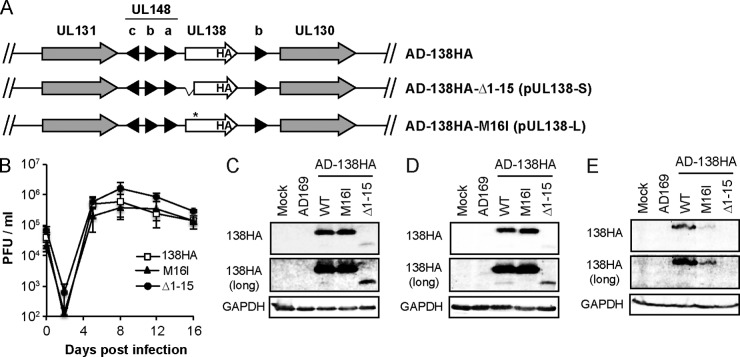

A more physiologic test for viral transcriptional regulation requires targeted promoters to be in their native context (the viral genome) and modulating genes to be expressed at endogenous levels. We previously accomplished this by making a recombinant virus (AD-UL138HA) expressing the wild-type UL138 gene (with an additional C-terminal HA tag) from its native promoter within the context of the laboratory-adapted strain AD169 genome (16). Here we made two additional AD169-based recombinant viruses, one (AD-UL138HA-M16I) encoding only pUL138-L and another (AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15) encoding only pUL138-S (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

AD169-UL138HA mutant viruses express pUL138-L or pUL138-S. (A) Schematic of AD169-UL138HA wild-type, Δ1–15, and M16I viruses. (B) NHDFs were infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 0.2, and cell-free virus was collected and analyzed by plaque assay at the indicated times. Data are the means ± SEM from 4 biological replicates. (C and D) Lysates from NHDFs (C) or MRC5s (D) mock infected or infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 1 for 24 h were analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. (E) Lysates from VPA-treated THP-1 cells mock infected or infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 3 for 24 h were analyzed by Western blotting with an HA antibody. Long exposures are also shown. GAPDH served as a loading control.

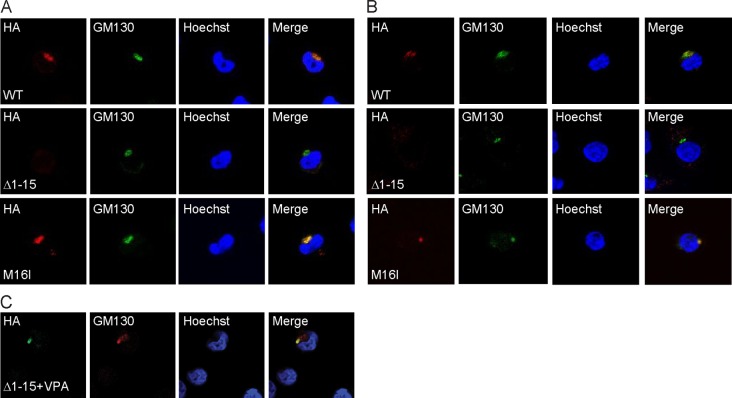

AD-UL138HA-M16I and AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 replicate with kinetics similar to those of wild-type virus in NHDFs (Fig. 5B). As shown earlier (Fig. 1B), wild-type virus expresses both long and short forms of UL138 upon infection of NHDFs (Fig. 5C) or MRC5s (Fig. 5D). AD-UL138HA-M16I expresses only pUL138-L, while AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 expresses only pUL138-S in NHDFs (Fig. 5C) or MRC5s (Fig. 5D). As shown earlier, pUL138-L accumulates to greater levels during infection than does pUL138-S. In THP-1 cells, we detected pUL138-L made by both wild-type virus and AD-UL138HA-M16I but were unable to detect pUL138-S made by either wild-type or AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 (Fig. 5E). That we could detect it under similar conditions in other experiments (Fig. 1C; see also Fig. 8D) underscores that the steady-state level achieved by pUL138-S is at or below our limit of detection. Nevertheless, we conclude that AD-UL138HA-M16I generates only pUL138-L and AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 generates only pUL138-S. pUL138-L expressed by these AD169-based viruses localized to the Golgi apparatus in THP-1 cells (Fig. 6A) and primary CD34+ cells (Fig. 6B). We were unable to detect pUL138-S in THP-1 or CD34+ cells by indirect immunofluorescence after AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 infection (Fig. 6A and B). However, when we infected VPA-treated THP-1 cells with AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15, we were able to visualize pUL138-S in a small number of cells, in which it localized to the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

UL138 proteins produced from AD169-based viruses localize to the Golgi apparatus. THP-1 (A) or VPA-treated primary CD34+ cells (B) were infected for 24 h with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 3 or 1, respectively, and then stained with antibodies for UL138 (HA) and the Golgi marker GM130 and imaged by indirect immunofluorescence. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst stain. (C) THP-1 cells treated with VPA were infected with AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 at an MOI of 1 for 18 h and processed as described above.

Consistent with previous work, IE transcription in THP-1 (Fig. 7A) and CD34+ (Fig. 7B) cells was rescued by VPA addition upon infection with AD169 but not the AD-UL138HA that expresses both protein isoforms of UL138. VPA was unable to rescue IE transcription from AD-UL138HA-M16I genomes in either THP-1 (Fig. 7A) or CD34+ (Fig. 7B) cells, indicating that pUL138-L suppresses IE transcription in these assays. AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 showed lower IE mRNA levels in the presence of VPA than did wild-type AD169 in THP-1 cells, indicating that pUL138-S also suppressed IE transcription (Fig. 7A). pUL138-S was not as strong of a repressor as pUL138-L or wild-type UL138 when expressed from the AD169 genome in THP-1 cells. Interestingly, the transcriptional repression associated with the presence of the UL138 Δ1–15 allele (Fig. 7A) indicates that pUL138-S has significant biological consequences at levels below the limit of detection on our Western blots.

FIG 7.

UL138 isoforms suppress VPA-responsive IE transcription during experimental latency. (A) RNA from THP-1 cells infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 1 in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 mM VPA for 18 h was analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of IE exon 3. Viral gene expression was normalized to cellular GAPDH and expressed relative to untreated AD169-infected cells. Data are the means ± SEM from 4 biological replicates. Conventional RT-PCR analysis for the indicated genes is presented under the graph. (B) RNA from primary CD34+ cells infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 1 in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 mM VPA for 24 h was analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of IE exon 3 as described for panel A. Data are the means ± SEM from at least 4 biological replicates. Conventional RT-PCR analysis for the indicated genes is presented under the graph. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.06) by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In CD34+ cells, IE transcription from AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 genomes was fully activated by VPA (Fig. 7B). At present, it is unclear if the difference between the ability of AD-UL138HA-Δ1–15 to repress VPA-induced IE transcription in THP-1 and CD34+ cells represents a cell type specificity for function or expression of pUL138-S (see Discussion). We conclude that pUL138-L silences IE transcription during the early stages of experimental latent infections (e.g., the first 18 to 24 h). While pUL138-S shares this ability, the magnitude of the effect is reduced and may show a dependence on cell type or whether latency was achieved naturally (in vivo) or experimentally (in vitro) (see Discussion).

UL138-null viruses made by either deletion of the entire open reading frame (14) or insertion of an in-frame stop codon (11) generate more infectious progeny than wild-type virus does after infection of CD34+ cells. Because the stop codon replaced methionine 16, this mutant (as well as the deletion virus) expresses neither pUL138-L nor pUL138-S. We therefore asked whether the long or short form of UL138 (or both) suppresses infectious virion formation during latency. Such experiments require the use of low-passage-number virus strains. Thus, we created TB40/E-UL138-3xFlag-based recombinant viruses encoding either an allele that expresses only pUL138-L (TB-UL138F-M16A) or an allele that expresses only pUL138-S (TB-UL138F-M1A) (Fig. 8A). TB-UL138F-M16A and TB-UL138F-M1A replicate with kinetics similar to those of wild-type virus in MRC5s (Fig. 8B) and synthesize UL138 proteins of the expected sizes in MRC5 (Fig. 8C) and THP-1 (Fig. 8D) cells.

As previous reports have demonstrated differences in localization between proteins expressed exogenously and those expressed in the natural context of low-passage-number virus strains (9), we addressed the localization of the two pUL138 protein isoforms during infection of MRC5s and THP-1 cells with TB-UL138F mutants. pUL138 colocalized with the Golgi body in addition to being distributed in puncta throughout the cytoplasm in both MRC5s (Fig. 9A) and THP-1 cells (Fig. 9B) infected with the parental TB-UL138F virus expressing both pUL138 isoforms. Colocalization of pUL138-S with the Golgi apparatus was not observed during infection with TB-UL138F-M1A in either cell type. Rather, pUL138-S exhibited a cytosolic distribution (Fig. 9A and B). In contrast, pUL138-L exhibited Golgi body and punctate cytosolic staining during infection with TB-UL138F-M16A similar to what was seen with the wild type in both cell types (Fig. 9A and B). As expected, no pUL138 staining was observed in either TB-UL138stop or mock infection (Fig. 9A and B). Together, these data suggest that during TB40/E infection of MRC5s, pUL138-L is Golgi body localized, while both isoforms are also distributed in the cytosol. As localization of pUL138-S during TB40/E infection differed from its localization in the context of transient expression (Fig. 3) or during recombinant AD-UL138HA infection (Fig. 6), it is possible that viral factors specific to clinical strains modulate the localization of pUL138-S. Given their demonstrated interactions with pUL138 (47), other proteins from the UL133-UL138 locus are candidates for this putative function.

FIG 9.

UL138 proteins produced from TB40/E-based viruses localize to the Golgi apparatus and cytoplasm. (A) MRC5 fibroblasts were infected for 48 h with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 2 and stained with antibodies for UL138 (FLAG) and the Golgi marker GM130 and imaged by indirect immunofluorescence. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (B) THP-1 cells were infected for 48 h with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 2 and analyzed as described above.

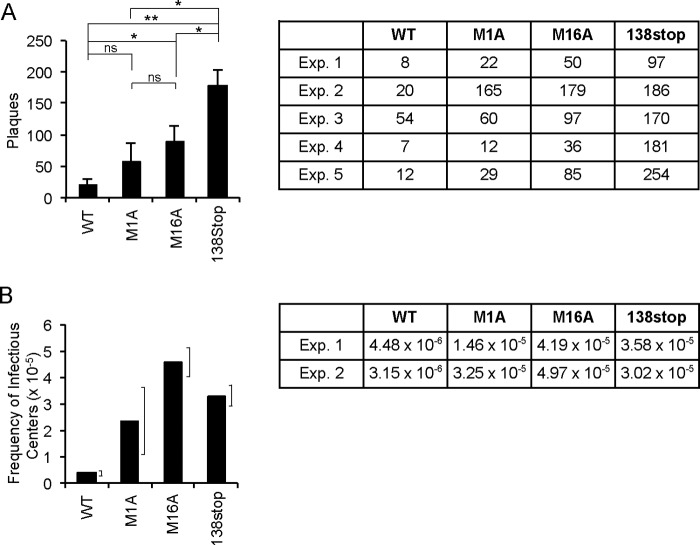

Because TB40/E maintains an additional, unidentified restriction to viral IE1 transcription in undifferentiated myeloid cells treated with VPA (16), we cannot use IE mRNA levels as a measure of function for the short- or long-form proteins in this context. However, viruses lacking the UL138 gene make significantly greater numbers of infectious particles during experimental latent infections than do UL138-expressing viruses (11, 12, 14). Therefore, we asked if pUL138-S, pUL138-L, or both proteins could suppress productive replication during latency. We performed assays in ESCs because they provide a robust readout (16, 31) and in CD34+ cells because of their physiologic relevance (11, 12, 14). In ESCs infected with wild-type virus for 10 days, very few infectious progeny virions were produced, whereas infections with a UL138-null virus (M16stop) produced ∼15-fold-greater numbers of infectious virus (Fig. 10A). TB-UL138F-M1A showed an ability to suppress progeny virion formation during 10 days of experimental latency that was statistically indistinguishable from wild-type virus. In contrast, TB-UL138F-M16A produced more infectious virus than the wild-type but less than the UL138-null virus. From these data, we conclude that pUL138-S prevents infectious virion formation during experimental latency in ESCs as efficiently as wild-type UL138 and that pUL138-L also suppresses infectious virion formation during experimental latency in ESCs, but not as effectively as wild-type UL138.

FIG 10.

pUL138-S suppresses progeny virion formation during HCMV latency in ESCs. (A) Infectious virions produced by ESCs infected with the indicated TB40/E-based viruses at an MOI of 2 for 10 days were quantified by plaque assay. Data from 5 biological replicates are graphed and shown in table format. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.1) by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. (B) Infectious virions produced by CD34+ cells infected with the indicated TB40/E-based viruses at an MOI of 2 for 10 days were quantified by TCID50 assay. Data from 2 biological replicates are graphed and shown in table format. Brackets represent the ranges of the data.

In CD34+ cells (Fig. 10B), wild-type virus produced very few infectious centers while the UL138-null virus produced ∼8-fold more. TB-UL138F-M1A and TB-UL138F-M16A both produced quantities of infectious virus more similar to the quantities produced by a UL138-null virus than to those of a wild-type virus. Thus, while pUL138-L appears to be more potent than pUL138-S at silencing IE transcription at the beginning of latency (Fig. 7B), pUL138-S is more efficient than pUL138-L at suppressing replication, at least in the context of ESC infection (Fig. 10A). In total, we conclude that both the long and short forms of UL138 promote HCMV latency.

DISCUSSION

The work presented here maps and analyzes a novel isoform of the HCMV latency determinant UL138. No transcriptional start sites within the UL138 cds have been mapped (11, 33, 37), and inhibiting translation initiation at codon 1 by mutation does not preclude the production of pUL138-S (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that pUL138-S is likely to be expressed from the same transcript encoding pUL138-L. We mapped the translational start site of pUL138-S to the codon for M16 (Fig. 2), indicating that this isoform does not represent a cleavage or degradation product of the full-length (long) protein. Taken together, these data suggest that pUL138-S most likely arises via alternative translation mechanisms. Recently, lactimidomycin-stalled (initiating) ribosomes were detected within the UL138 gene at both codon 1 (∼93%) and codon 16 (∼7%), providing independent evidence for translation of a short form of pUL138 (33). An internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-like element has been previously shown to support translation of pUL138-L from transcripts with open reading frames upstream of the UL138 cds (45). Although this study did not examine the expression of pUL138-S, it is possible that the IRES-like element could also support expression of pUL138-S. When the methionine at codon 1 of UL138 is mutated (ΔM1 or M1A), the accumulation of pUL138-S increases (Fig. 2C and 8C), which is a result consistent with a leaky scanning mechanism of translation (48).

The differences in pUL138-S localization in AD169 and TB40/E infections could be due to the differences in the context of expression. In AD169 infection, expression of pUL138-S was achieved by deletion of the first 15 amino acids, whereas in TB40/E infection the first methionine codon was disrupted. These differences in mutagenesis approaches may contribute to changes in expression levels and may contribute to differences in the results obtained with the different strains. However, it should also be noted that pUL138 is expressed in the context of the UL133-UL138 locus in TB40/E infection. It is possible that expression of other UL133-UL138 proteins influences the function of pUL138 isoforms, as pUL133, pUL135, and pUL136 are known to interact with pUL138 (47). We also cannot exclude the possibility that other less well defined differences between AD169 and TB40/E influence pUL138 isoform localization and function.

Golgi body localization or retention signals within UL138 have not been demonstrated. The N-terminal signal sequence and putative transmembrane domain should be absent and disrupted, respectively, in pUL138-S, yet this protein can be found at the Golgi apparatus as well as the cytoplasm. There is some heterogeneity of pUL138-S localization when expressed in different contexts. Why this occurs is unclear but could result from, among other things, differences in expression levels, cis-acting mRNA sequences (49), or other viral proteins present during infection. pUL138-L interacts with a number of the other proteins encoded within the UL133-UL138 locus (47). While it is small enough to diffuse freely through nuclear pores, pUL138-S is not detected in the nucleus. This may be due in part to the low levels of the protein achieved in cells during infection. However, transient transfection results in the relatively abundant accumulation of pUL138-S but not its nuclear localization. It remains to be determined how UL138 exerts transcriptional effects in the nucleus from its position at the Golgi apparatus and in the cytoplasm.

pUL138-S is expressed at low levels during infection and accumulates to much lower levels than pUL138-L, making it difficult to detect. In our reporter assays (Fig. 4), we needed to transfect three times the amount of Δ1–15 encoding plasmid to achieve protein levels similar to those generated by wild-type or M16A alleles. Viral proteins in persistent infections, for example, the HCMV UL136 protein and the human papillomavirus E7 protein, are often found at low levels, presumably to limit immune detection (9, 50, 51). Low-level protein accumulation may result from weak transcription, inefficient translation, codon usage, poor protein stability, or a combination of these factors. For example, the UL138 gene in TB40/E has a codon adaption index (CAI) (52) of 0.7 (GenScript), which is considered suboptimal for expression. Intriguingly, it may also result from microRNA (miRNA)-mediated translational repression, as a viral microRNA, miR-UL36, has been reported to downregulate UL138 (53) and is expressed during both experimental and natural latent infections (54). Regulation by cellular miRNAs is also possible, as has been detected for viral IE1 transcripts in latently infected cells (22, 55). The very low levels of UL138 proteins detected are consistent with viral attempts at immune evasion during latency, as UL138 possesses known cytotoxic T-cell-specific epitopes (56). Interestingly, the identified CD8+ T cell epitope is from the amino terminus of the protein found in pUL138-L but not pUL138-S (56).

Reporter assays (Fig. 4) and quantitation of IE transcripts in the presence of VPA (Fig. 7) indicate that the long form of UL138 may play a more prominent role than the short form at suppressing IE gene expression during latency. In contrast, assays in ESCs (Fig. 10A) indicate that the short isoform better suppresses infectious virion production during latency than does the long form. These subtle differences in function may reflect a time dependence in activity. One possible model is that early and prominent accumulation of pUL138-L silences IE transcription at the beginning of latency prior to the protein being downregulated. At later times, weaker expression of pUL138-S might suppress progeny virion production without resulting in the presentation of UL138 epitopes unique to the long form and recognized by CD8+ T cells (56). Interestingly, C-terminal peptides found in pUL138-S elicit a CD4+ T cell response that includes secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine cellular interleukin-10 (cIL-10) (57). Thus, pUL138-S might promote latency by a combination of transcriptional repression of lytic-phase genes and by protecting latently infected cells from immune detection and clearance.

We were unable to detect the suppressive functions of pUL138-S observed in THP-1s or ESCs in the context of CD34+ HPCs. The cell-type-dependent differences may reflect different kinetics of isoform synthesis or accumulation, cell type specificity for function, or a combination of these features. Interestingly, an unbiased examination of HCMV latent transcripts (36) demonstrated that the fraction of all mapped HCMV latent messages represented by UL138 was ∼5-fold higher during experimental infection of monocytes than during natural infection of these cells but ∼15-fold lower in experimental latent infection of CD34+ cells than in natural infections. Thus, it appears that UL138 is expressed better in monocytes in vitro and better in CD34+ cells in vivo, at least at the transcript level. The low levels of UL138 expression in in vitro systems may contribute to the difficulty in discerning functional outcomes of pUL138-S in CD34+ cells.

We describe pUL138 as silencing transcription because it clearly represses an HCMV promoter, the MIEP. pUL138 decreases luciferase enzymatic activity when the gene encoding the protein is driven by the MIEP but not when it is expressed from the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter (16), making posttranscriptional regulation of this reporter mRNA unlikely. Furthermore, pUL138 expression has been shown to modify the chromatin structure of the MIEP in a manner correlated with transcriptional repression (16). Thus, despite its cytoplasmic localization, pUL138 modulates viral transcription. However, because of its cytoplasmic localization, supplementary effects on mRNA stability or translation are not excluded by any of our data. More work is required to determine if pUL138 regulates latent viral gene expression posttranscriptionally in addition to its transcriptional effects.

While UL138 has been associated with multiple effects during HCMV infection (13, 16, 18), previous studies did not take into account the individual roles of the pUL138 protein isoforms. Our current study demonstrates that the two protein isoforms of pUL138 may have both overlapping and distinct functions during HCMV infection. In recent years, many studies have contributed to a body of work that begins to effectively demonstrate the power and function of increased coding capacity in HCMV through transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational mechanisms (9, 15, 32, 33, 37, 58, 59). Further, many examples of viral protein isoforms that have similar or unique functions exist (60–67), but these examples likely only begin to scratch the surface of the important roles that protein isoforms play in viral infection and virus-host interactions. More work is needed to fully understand the functions of the two pUL138 isoforms and how their functions, in cooperation with the UL133-138 locus, contribute to the persistence of HCMV within the human host.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Diccon Fiore for expert technical assistance, Nat Moorman for help with bioinformatics, and the members of the Goodrum and Kalejta labs for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to R.F.K. (AI074984) and F.G. (AI079059). E.R.A. was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

S.H.L. and R.F.K. designed all experiments. S.H.L. and K.C. generated mutant alleles and recombinant viruses. S.H.L. and C.B.G. performed reporter and immunofluorescence assays; K.C. performed CD34+ cell latency maintenance assays, growth curves, and immunofluorescence assays; E.R.A. performed RNA and protein expression experiments, growth curves, and immunofluorescence assays; J.-H.L. performed ESC latency maintenance and immunofluorescence assays; and M.R. performed protein expression experiments. K.C., E.R.A., R.F.K., and F.G. analyzed the data. R.F.K. and F.G. wrote the paper with comments from all authors.

We declare that we have no competing interests. Data related to this paper may be requested from R.F.K. and F.G.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01547-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boeckh M, Geballe AP. 2011. Cytomegalovirus: pathogen, paradigm, and puzzle. J Clin Invest 121:1673–1680. doi: 10.1172/JCI45449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt W. 2008. Manifestations of human cytomegalovirus infection: proposed mechanisms of acute and chronic disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 325:417–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. 2007. Cytomegaloviruses, p 2701–2673. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodrum F, Caviness K, Zagallo P. 2012. Human cytomegalovirus persistence. Cell Microbiol 14:644–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinzger C, Digel M, Jahn G. 2008. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 325:63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurain NS, Chou S. 2010. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:689–712. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00009-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messerle M, Hahn G, Brune W, Koszinowski UH. 2000. Cytomegalovirus bacterial artificial chromosomes: a new herpesvirus vector approach. Adv Virus Res 55:463–478. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu D, Silva MC, Shenk T. 2003. Functional map of human cytomegalovirus AD169 defined by global mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:12396–12401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635160100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caviness K, Cicchini L, Rak M, Umashankar M, Goodrum F. 2014. Complex expression of the UL136 gene of human cytomegalovirus results in multiple protein isoforms with unique roles in replication. J Virol 88:14412–14425. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02711-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humby MS, O'Connor CM. 2016. HCMV US28 is important for latent infection of hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Virol 90:2959–2970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02507-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrucelli A, Rak M, Grainger L, Goodrum F. 2009. Characterization of a novel Golgi-localized latency determinant encoded by human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 83:5615–5629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01989-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umashankar M, Petrucelli A, Cicchini L, Caposio P, Kreklywich CN, Rak M, Bughio F, Goldman DC, Hamlin KL, Nelson JA, Fleming WH, Streblow DN, Goodrum F. 2011. A novel human cytomegalovirus locus modulates cell type-specific outcomes of infection. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002444. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umashankar M, Rak M, Bughio F, Zagallo P, Caviness K, Goodrum FD. 2014. Antagonistic determinants controlling replicative and latent states of human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 88:5987–6002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrum F, Reeves M, Sinclair J, High K, Shenk T. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus sequences expressed in latently infected individuals promote a latent infection in vitro. Blood 110:937–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caviness K, Bughio F, Crawford LB, Streblow DN, Nelson JA, Caposio P, Goodrum F. 2016. Complex interplay of the UL136 isoforms balances cytomegalovirus replication and latency. mBio 7(2):e01986. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01986-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Albright ER, Lee JH, Jacobs D, Kalejta RF. 2015. Cellular defense against latent colonization foiled by human cytomegalovirus UL138 protein. Sci Adv 1:e1501164. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rauwel B, Jang SM, Cassano M, Kapopoulou A, Barde I, Trono D. 2015. Release of human cytomegalovirus from latency by a KAP1/TRIM28 phosphorylation switch. Elife 4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weekes MP, Tan SY, Poole E, Talbot S, Antrobus R, Smith DL, Montag C, Gygi SP, Sinclair JH, Lehner PJ. 2013. Latency-associated degradation of the MRP1 drug transporter during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. Science 340:199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1235047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connor CM, Nukui M, Gurova KV, Murphy EA. 2016. Inhibition of the FACT complex reduces transcription from the human cytomegalovirus major major immediate early promoter in models of lytic and latent replication. J Virol 90:4249–4253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression is silenced by the Daxx-mediated intrinsic immune defense when model latent infections are established in vitro. J Virol 81:9109–9120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saffert RT, Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. 2010. Cellular and viral control over the initial events of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency in CD34+ cells. J Virol 84:5594–5604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00348-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connor CM, Vanicek J, Murphy EA. 2014. Host microRNA regulation of human cytomegalovirus immediate early protein translation promotes viral latency. J Virol 88:5524–5532. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00481-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bughio F, Elliott DA, Goodrum F. 2013. An endothelial cell-specific requirement for the UL133-UL138 locus of human cytomegalovirus for efficient virus maturation. J Virol 87:3062–3075. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02510-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bughio F, Umashankar M, Wilson J, Goodrum F. 2015. Human cytomegalovirus UL135 and UL136 genes are required for post-entry tropism in endothelial cells. J Virol 89:6536–6550. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00284-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caviness K, Bughio F, Crawford LB, Streblow DN, Nelson JA, Caposio P, Goodrum F. 2016. Complex interplay of the UL136 isoforms balances cytomegalovirus replication and latency. mBio 7:e01986. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01986-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton RJ, Prod'homme V, Purbhoo MA, Moore M, Aicheler RJ, Heinzmann M, Bailer SM, Haas J, Antrobus R, Weekes MP, Lehner PJ, Vojtesek B, Miners KL, Man S, Wilkie GS, Davison AJ, Wang EC, Tomasec P, Wilkinson GW. 2014. HCMV pUL135 remodels the actin cytoskeleton to impair immune recognition of infected cells. Cell Host Microbe 16:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le VT, Trilling M, Hengel H. 2011. The cytomegaloviral protein pUL138 acts as potentiator of TNF receptor 1 surface density to enhance ULb′-encoded modulation of TNF-{alpha} signaling. J Virol 85:13260–13270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06005-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montag C, Wagner JA, Gruska I, Vetter B, Wiebusch L, Hagemeier C. 2011. The latency-associated UL138 gene product of human cytomegalovirus sensitizes cells to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) signaling by upregulating TNF-alpha receptor 1 cell surface expression. J Virol 85:11409–11421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05028-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. 2006. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic immune defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate-early gene expression. J Virol 80:3863–3871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3863-3871.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albright ER, Kalejta RF. 2013. Myeloblastic cell lines mimic some but not all aspects of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency defined in primary CD34+ cell populations. J Virol 87:9802–9812. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01436-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. 2013. Human embryonic stem cell lines model experimental human cytomegalovirus latency. mBio 4:e00298-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00298-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stern-Ginossar N, Ingolia NT. 2015. Ribosome profiling as a tool to decipher viral complexity. Annu Rev Virol 2:335–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-054854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern-Ginossar N, Weisburd B, Michalski A, Le VT, Hein MY, Huang SX, Ma M, Shen B, Qian SB, Hengel H, Mann M, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS. 2012. Decoding human cytomegalovirus. Science 338:1088–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1227919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung AK, Abendroth A, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. 2006. Viral gene expression during the establishment of human cytomegalovirus latent infection in myeloid progenitor cells. Blood 108:3691–3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-026682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodrum FD, Jordan CT, High K, Shenk T. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression during infection of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells: a model for latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:16255–16260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252630899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossetto CC, Tarrant-Elorza M, Pari GS. 2013. Cis and trans acting factors involved in human cytomegalovirus experimental and natural latent infection of CD14 (+) monocytes and CD34 (+) cells. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003366. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tirosh O, Cohen Y, Shitrit A, Shani O, Le-Trilling VT, Trilling M, Friedlander G, Tanenbaum M, Stern-Ginossar N. 2015. The transcription and translation landscapes during human cytomegalovirus infection reveal novel host-pathogen interactions. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005288. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umashankar M, Goodrum F. 2014. Hematopoietic long-term culture (hLTC) for human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. Methods Mol Biol 1119:99–112. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-788-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tischer BK, von Einem J, Kaufer B, Osterrieder N. 2006. Two-step red-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques 40:191–197. doi: 10.2144/000112096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinzger C, Hahn G, Digel M, Katona R, Sampaio KL, Messerle M, Hengel H, Koszinowski U, Brune W, Adler B. 2008. Cloning and sequencing of a highly productive, endotheliotropic virus strain derived from human cytomegalovirus TB40/E. J Gen Virol 89:359–368. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang J, Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. 2011. Elongin B-mediated epigenetic alteration of viral chromatin correlates with efficient human cytomegalovirus gene expression and replication. mBio 2:e00023-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juckem LK, Boehme KW, Feire AL, Compton T. 2008. Differential initiation of innate immune responses induced by human cytomegalovirus entry into fibroblast cells. J Immunol 180:4965–4977. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao H, Lee JH, Kondo R, Katata M, Imadome K, Miyado K, Inoue N, Fujiwara S, Nakamura H. 2014. The highly conserved human cytomegalovirus UL136 ORF generates multiple Golgi-localizing protein isoforms through differential translation initiation. Virus Res 179:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grainger L, Cicchini L, Rak M, Petrucelli A, Fitzgerald KD, Semler BL, Goodrum F. 2010. Stress-inducible alternative translation initiation of human cytomegalovirus latency protein pUL138. J Virol 84:9472–9486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00855-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura N. 2010. Emerging new roles of GM130, a cis-Golgi matrix protein, in higher order cell functions. J Pharmacol Sci 112:255–264. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09R03CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrucelli A, Umashankar M, Zagallo P, Rak M, Goodrum F. 2012. Interactions between proteins encoded within the human cytomegalovirus UL133-UL138 locus. J Virol 86:8653–8662. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00465-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozak M. 2002. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene 299:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weis BL, Schleiff E, Zerges W. 2013. Protein targeting to subcellular organelles via MRNA localization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833:260–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K. 2009. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology 384:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smotkin D, Wettstein FO. 1987. The major human papillomavirus protein in cervical cancers is a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein. J Virol 61:1686–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharp PM, Li WH. 1987. The codon adaptation index—a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res 15:1281–1295. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y, Qi Y, Ma Y, He R, Ji Y, Sun Z, Ruan Q. 2013. Down-regulation of human cytomegalovirus UL138, a novel latency-associated determinant, by hcmv-miR-UL36. J Biosci 38:479–485. doi: 10.1007/s12038-013-9353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meshesha MK, Bentwich Z, Solomon SA, Avni YS. 2016. In vivo expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) microRNAs during latency. Gene 575:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan D, Flores O, Umbach JL, Pesola JM, Bentley P, Rosato PC, Leib DA, Cullen BR, Coen DM. 2014. A neuron-specific host microRNA targets herpes simplex virus-1 ICP0 expression and promotes latency. Cell Host Microbe 15:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tey SK, Goodrum F, Khanna R. 2010. CD8+ T-cell recognition of human cytomegalovirus latency-associated determinant pUL138. J Gen Virol 91:2040–2048. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020982-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mason GM, Jackson S, Okecha G, Poole E, Sissons JG, Sinclair J, Wills MR. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated proteins elicit immune-suppressive IL-10 producing CD4(+) T cells. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003635. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webel R, Hakki M, Prichard MN, Rawlinson WD, Marschall M, Chou S. 2014. Differential properties of cytomegalovirus pUL97 kinase isoforms affect viral replication and maribavir susceptibility. J Virol 88:4776–4785. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00192-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathers C, Spencer CM, Munger J. 2014. Distinct domains within the human cytomegalovirus U(L)26 protein are important for wildtype viral replication and virion stability. PLoS One 9:e88101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cen O, Longnecker R. 2015. Latent membrane protein 2 (LMP2). Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 391:151–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leelawong M, Lee JI, Smith GA. 2012. Nuclear egress of pseudorabies virus capsids is enhanced by a subspecies of the large tegument protein that is lost upon cytoplasmic maturation. J Virol 86:6303–6314. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07051-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oksayan S, Wiltzer L, Rowe CL, Blondel D, Jans DA, Moseley GW. 2012. A novel nuclear trafficking module regulates the nucleocytoplasmic localization of the rabies virus interferon antagonist, P protein. J Biol Chem 287:28112–28121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rechsteiner MP, Berger C, Zauner L, Sigrist JA, Weber M, Longnecker R, Bernasconi M, Nadal D. 2008. Latent membrane protein 2B regulates susceptibility to induction of lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Virol 82:1739–1747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01723-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sadler R, Wu L, Forghani B, Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, Ganem D. 1999. A complex translational program generates multiple novel proteins from the latently expressed kaposin (K12) locus of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 73:5722–5730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schommartz T, Loroch S, Alawi M, Grundhoff A, Sickmann A, Brune W. 2016. Functional dissection of an alternatively spliced herpesvirus gene by splice site mutagenesis. J Virol 90:4626–4636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02987-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toptan T, Fonseca L, Kwun HJ, Chang Y, Moore PS. 2013. Complex alternative cytoplasmic protein isoforms of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen 1 generated through noncanonical translation initiation. J Virol 87:2744–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang G, Chan B, Samarina N, Abere B, Weidner-Glunde M, Buch A, Pich A, Brinkmann MM, Schulz TF. 2016. Cytoplasmic isoforms of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus LANA recruit and antagonize the innate immune DNA sensor cGAS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E1034–E1043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516812113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.