Abstract

Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) are pattern-recognition receptors similar to toll-like receptors (TLRs). While TLRs are transmembrane receptors, NLRs are cytoplasmic receptors that play a crucial role in the innate immune response by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Based on their N-terminal domain, NLRs are divided into four subfamilies: NLRA, NLRB, NLRC, and NLRP. NLRs can also be divided into four broad functional categories: inflammasome assembly, signaling transduction, transcription activation, and autophagy. In addition to recognizing PAMPs and DAMPs, NLRs act as a key regulator of apoptosis and early development. Therefore, there are significant associations between NLRs and various diseases related to infection and immunity. NLR studies have recently begun to unveil the roles of NLRs in diseases such as gout, cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndromes, and Crohn's disease. As these new associations between NRLs and diseases may improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and lead to new approaches for the prevention and treatment of such diseases, NLRs are becoming increasingly relevant to clinicians. In this review, we provide a concise overview of NLRs and their role in infection, immunity, and disease, particularly from clinical perspectives.

Keywords: Innate immunity, pattern recognition receptors, NOD-like receptors, inflammasomes

INTRODUCTION

Essential to a host's immune responses to pathogens is discrimination of non-self molecules from self molecules. The innate immune system, which plays a pivotal role in the first line of host defense against infection, is equipped with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) not found in the host and then activate the host's immune response.1,2 Many PRRs have been identified since toll-like receptors (TLRs) were first identified as PRRs about two decades ago.3 Based on distinct genetic and functional differences, PRRs are currently classified into five families:4 TLRs, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectins (CTLs), and absent-in-melanoma (AIM)-like receptors (ALRs). TLRs and CTLs are located in the plasma membrane, while the NLRs, RLRs, and ALRs are intracellular PRRs.

The recognition by NLRs of PAMPs and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from microbial structures or self-or environment-derived molecules leads to the induction of the innate immune response.5 In humans, there are 22 known NLRs,6 all of which are associated with many human diseases.7 Readers who wish to know further basic aspects of NLRs should consult other excellent and recent reviews.4,7 In this review, we will provide a concise overview of the members of the NLR family and their role in infection, immunity, and disease, especially from clinical perspectives.

CLASSIFICATION AND STRUCTURE OF THE NLR FAMILY

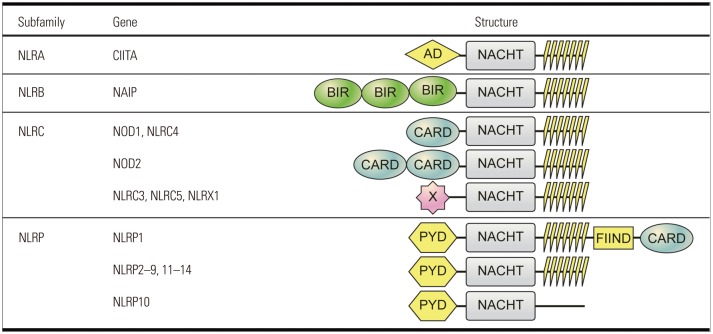

NLR proteins have a common domain organization with a central NOD (NACHT: NAIP, CIITA, HET-E, and TP-2), N-terminal effector domain, and C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) (Fig. 1).6 The NACHT domain (consisting of seven distinct conserved motifs, including the ATP/GTPase-specific P-loop, the Mg2+-binding site, and five more-specific motifs) is involved in dNTPase activity and oligomerization.8 The C-terminal LRR domain is involved in ligand binding or activator sensing. The N-terminal domain performs effector functions by interacting with other proteins. There are four recognizable N-terminal domains, which are used to classify NLRs into four subfamilies: the acidic transactivation domain (NLRA), the baculoviral inhibitory repeat-like domain (NLRB), the caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD; NLRC), and the pyrin domain (NLRP) (Fig. 1).6

Fig. 1. Classification and protein structure of human NOD-like receptor family (based on Ref. 6). AD, acidic transactivation domain; NACHT, for NAIP, CIITA, HET-T, and TP-1; BIR, baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis repeat; CARD, caspase activation and recruitment domain; X, unidentified; PYD, pyrin domain, FIIND, function to find domain;  , leucine-rich repeat; NOD, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain.

, leucine-rich repeat; NOD, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain.

The NLRA subfamily includes only one member, the MHC-II transactivator (CIITA). Similarly, the human NLRB subfamily has only one member, NAIP. The NLRC subfamily consists of six members: NLRC1 (NOD1), NLRC2 (NOD2), NLRC3, NLRC4, NLRC5, and NLRX1. NLRC3, NLRC5, and NLRX1 are classified as belonging to the NLRC subfamily due to their homology and phylogenetic relationship, although their N-terminal domains have not been named.4,6,9 The NLRP subfamily consists of 14 members, NLRP1-14. No LRR domain is observed in NLRP10, which may indicate a role for this protein as a signaling adaptor rather than as an NLR sensor.7

FUNCTION OF NLRs

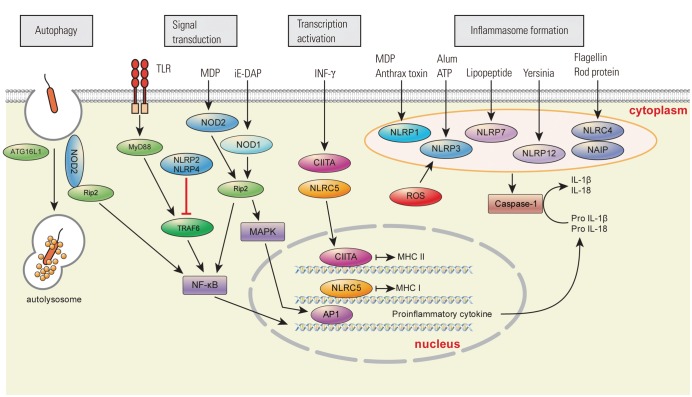

The NLRs recognize various ligands from microbial pathogens (peptidoglycan, flagellin, viral RNA, fungal hyphae, etc.), host cells (ATPs, cholesterol crystals, uric acid, etc.), and environmental sources (alum, asbestos, silica, alloy particles, UV radiation, skin irritants, etc.). Most NLRs act as PRRs, recognizing the above ligands and activate inflammatory responses. However, some NLRs may not act as PRRs but instead respond to cytokines such as interferons. The activated NLRs show various functions that can be divided into four broad categories: inflammasome formation, signaling transduction, transcription activation, and autophagy (Fig. 2).4 Below, we describe each function.

Fig. 2. Functions of NOD-like receptors. The NLRs activities can be divided into four broad categories; autophagy, signal transduction, transcription activation, and inflammasome formation. NOD2 induces autophagy to remove pathogens by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. NOD1 and NOD2 recognize γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP) and muramyl dipeptide (MDP) respectively; thereafter they activate the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. NLRP2 and NLRP4 act as negative regulators of NF-κB pathway by modifying TRAF6. CIITA and NLRC5 are transactivators of major histocompatibility complexes (MHC). Inflammasome-forming NLRs (orange circle) convert procytokines to active IL-1β and IL-18 by activating caspase-1. NOD, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain; NLRs, NOD-like receptors; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TRAF, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor; IL, interleukin; INF-γ, interferon-γ.

Inflammasome formation

Inflammasome is a multimeric protein complex that activates caspase-1.10 Activation of caspase-1 results in the processing and maturation of proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 as well as an inflammatory cell death termed pyroptosis (Fig. 2).10 As IL-1β is a potent mediator of inflammatory responses, its overproduction is associated with many autoinflammatory syndromes, such as gout and periodic fever syndromes, which include Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) and cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndromes (CAPS).11,12 Pyroptosis is an inflammatory cell death that results in the release of DAMPs and reinforcement of the immune response. Inflammasomes are activated by eight members of NLRs (NLRP1, NLRP2, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP7, NLRP12, NLRC4, and NAIP) and AIM2, which is not discussed in this review (Table 1).7,10

Table 1. Functions and Associated Diseases of Human NOD-Like Receptors.

| Sub-family | NLR | Signaling pathway | Function | Associated diseases | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLRA | CIITA | MHC-II transcriptional regulator | Regulation of MHC-II expression | Bare lymphocyte syndrome, Hodgkin disease, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma | 35, 85 |

| NLRB | NAIP | TAK1-dependent JNK1 activation, inflammasome assembly | Flagellin sensing, pyroptosis, inhibition of apoptosis | Increased susceptibility to legionella, spinal muscular dystrophy | 18, 19, 77, 86 |

| NLRC | NOD1 | RIP2-dependent NF-kB and MAPK activation | PRR for DAP | Asthma, inflammatory bowel diseases | 22, 83, 84 |

| NOD2 | RIP2-dependent NF-kB and MAPK activation | PRR for MDP and viral ssRNA, autophagy | Crohn's disease, Blau syndrome, atopic eczema, atopic dermatitis, susceptibility to leprosy and tuberculosis | 23, 25, 34, 39, 75, 79, 80, 81, 82 | |

| NLRC3 | Interaction with STING to reduce STING-TBK1 association | Negative regulation of T cell activation and TLR response | 27, 29, 87 | ||

| NLRC4 | Inflammasome formation | PRR for flagellin and rod protein, pyroptosis, phagosome maturation | Increased susceptibility to bacterial infection | 7, 16, 17, 88 | |

| NLRC5 | MHC-I regulation, type I interferon response | MHC-I upregulation, regulates innate immune response | 36, 89 | ||

| NLRX1 | Mitochondria | ROS generation, viral-induced autophagy | Increased susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B | 40, 90, 91 | |

| NLRP | NLRP1 | Inflammasome formation | PRR for MDP, anthrax lethal toxin | Vitiligo, celiac disease, Addison's disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, giant cell arteritis, congenital toxoplasmosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer's disease, corneal intraepithelial dyskeratosis | 14, 20, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 92 |

| NLRP2 | Inflammasome formation | Negative regulation of NF-kB, embryonic development | Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome | 26, 70, 93, 94 | |

| NLRP3 | Inflammasome formation | PRR for DAMPs | Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome, gout, type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, psoriasis, increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infections, Inflammatory bowel diseases, type 2 diabetes | 4, 44, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 95 | |

| NLRP4 | DTX4-dependent TBK1 degradation, beclin-1 dependent autophagy | Negative regulation of type I interferon, autophagy | 28 | ||

| NLRP5 | Unknown | Embryogenesis | 96 | ||

| NLRP6 | Inflammasome formation | Negative regulation of NF-kB | Colitis and colon cancer | 30, 71 | |

| NLRP | NLRP7 | Inflammasome formation | PRR for lipopeptide | Hydatidiform mole, testicular seminoma, endometrial cancer | 21, 72, 73, 74 |

| NLRP8 | Unknown | Unknown | |||

| NLRP9 | Unknown | Unknown | |||

| NLRP10 | Unknown | Dendritic cell migration | Increased susceptibility to bacterial infection, atopic dermatitis | 7, 97, 98 | |

| NLRP11 | Unknown | Unknown | |||

| NLRP12 | Inflammasome formation | Negative regulation of NF-kB | Atopic dermatitis, periodic fever syndrome | 31, 75, 76, 99 | |

| NLRP13 | Unknown | Unknown | |||

| NLRP14 | Unknown | Spermatogensis | Spermatogenic failure | 100 |

PRR, pattern recognition receptor; DAP, diaminopimelic acid; MDP, muramyl dipeptide; TLR, toll-like receptor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns, NOD, nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain; NLR, NOD-like receptor; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; RIP2, receptor interacting protein 2; NF-kB, nuclear factor kappa B; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; STING, stimulator of interferon genes; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Inflammasome formation is triggered by either pathogen-associated or sterile activators. Pathogen-associated activators of inflammasomes include various PAMPs derived from bacteria [pore-forming toxins, lethal toxins, flagellin/rod proteins, muramyl dipeptide (MDP), RNA, and DNA], viruses (RNA and M2 protein), fungus (β-glucans, hyphae, mannan, and zymosan), and protozoa (hemozoin).10 Sterile activators include self-derived DAMPs (ATP, cholesterol crystals, monosodium urate/calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals, glucose, amyloid β, and hyaluronan) and environment-derived stimulants (alum, asbestos, silica, alloy particles, UV radiation, and skin irritants).10 When the eight NLRs detect these PAMPs and DAMPs (Fig. 2), NLRs recruit apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) via a pyrin-pyrin domain interaction.13 Subsequently, pro-caspase-1 binds to ASC through CARD-CARD domains, which completes the formation of inflammasome.13 NLRP1 contains the CARD domain that can interact directly with procaspase-1 and can thus form inflammasomes without ASC.14 NLRC4, which has no pyrin domain, can form two types of inflammasomes. The recruitment of ASC to the NLRC4 inflammasome results in IL-1β and IL-18 production, while NLRC4 inflammasome formed without the recruitment of ASC results in pyroptosis.15

NAIP and NLRC4 form NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasomes upon recognition of bacterial flagellin and the bacterial type III secretion system.16,17,18 Therefore, NAIP and NLRC4 are linked to susceptibility to bacterial infections.7,19 NLRP1 inflammasomes are activated by MDP,14 a common peptidoglycan motif in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and by anthrax lethal toxin.20 NLRP3-inflammasome activation is triggered by various PAMPs and DAMPs including alum, silica, ATP, and uric acid.4 NLRP7 can recognize bacterial lipopeptide.21

Signaling transduction

NOD1 recognizes γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), which is a peptidoglycan component found only in Gram-negative bacteria.22 NOD2 recognizes MDP from both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.23 Both NOD1 and NOD2 activate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) signaling pathway, which plays an important role in regulating the host immune response (Fig. 2). Specifically, recognition of cytosolic peptidoglycan ligands allows NOD1/NOD2 to interact with a common downstream adaptor molecule, receptor interacting protein 2 (RIP2), which is a serine/threonine kinase that can activate NF-kB.24 Activated NF-kB can move to the nucleus and enhance transcription of proinflammatory cytokines.22,25 In contrast to NOD1/NOD2, NLRC3, and NLRP2/4 act as negative regulators of the NF-kB pathway by modifying tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) (Fig. 2).26,28,29 NLRP6 and NLRP12 are also suggested as negative regulators.30,31

In addition to activating the NF-kB pathway, NOD1/NOD2 activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-signaling pathway, which results in proinflammatory cytokine secretion (Fig. 2).32,33 NOD2 can also sense viral ssRNA, after which it activates interferon production and antiviral defense.34

Transcription activation

Antigen presentation by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules is central to the function of the adaptive immune system. Therefore, the regulation of these MHC genes and their accessory molecules is crucial for the adaptive immune response. In 1993, NLRA (CIITA) was found to function as a transactivator of MHC class II gene expression. Complementary experiments showed that the NLRA fully corrected the MHC class II regulatory defect of cells from patients with bare lymphocyte syndrome. This rare genetic disorder is characterized by severe combined immunodeficiency and a complete lack of the expression of MHC class II molecules in all tissues.35 Recent studies have shown that NLRC5 plays a crucial role in the expression of the MHC class I gene. NLRC5 induced by interferon-γ acts as a transactivator of the MHC class I gene by assembling regulatory factor X (RFX), cAMP-responsive-element-binding protein 1 (CREB1), activating transcription factor 1 (ATF1), and nuclear transcription factor Y (NFY) on the SXY module in the MHC class I promoter.36,37 Although MHC-I and -II expression depends on several transcription factors such as NF-kB, the IFN regulatory factor family, RFX, CREB1, ATF1, and NFY, MHC expression requires the presence of the NLRA and NLRC5.4,37

Autophagy

Autophagy is a fundamental cellular homeostatic mechanism in which cells autodigest parts of their cytoplasm for removal or turnover. Based on the target of degradation, autophagy has been described as mitophagy, reticulophagy, and pexophagy for autodigestion of the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and peroxisomes, respectively. In contrast to autophagy, xenophagy refers to an autophagic pathway that targets intracellular bacteria and viruses.38 Autophagy is mediated by unique organelles called autophagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes and allow lysosomal enzymes to degrade the sequestered cytoplasmic materials in autolysosomes.38 Autophagosome formation involves many autophagy-related (ATG) proteins.38

NOD1 and NOD2 can induce autophagy to remove pathogens by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry (Fig. 2).39 NLRX1, located in mitochondria, regulates virus-induced autophagy by interacting with the Tu translation elongation factor of mitochondria (TUFM) that then interacts with ATG5-ATG12 and ATG16L1.40 NLRP4 is known as a negative regulator of autophagic processes through an association with beclin1, one of the key initiators of the autophagic process.41

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF NLR

In addition to NLRs playing a crucial role in defending against pathogens as a pattern recognition receptor, they also have other functions unrelated to pathogen detection, such as apoptosis and playing a role in early development. Therefore, their abnormalities are linked to various diseases associated with infections, inflammation, and cancer. Understanding their roles in the pathogenesis of certain diseases may help us develop new drugs or new approaches to prevent and treat these diseases. Genome-wide association studies have shown a significant association of polymorphisms of NLR genes with various diseases.7,10 NLR-associated diseases are summarized in Table 1. Described below are several examples of NLR studies that have shed new insights into disease mechanisms.

Autoinflammatory diseases and NLRs

Autoinflammatory diseases are self-directed inflammatory diseases involving innate immune cells without autoantibodies or autoreactive T cells, whereas autoimmune diseases involve dysfunctional adaptive immune systems producing autoreactive B or T cells.42 Reflecting the important roles of NLRs in inflammation, abnormalities of NLRs have been associated with several (but not all) autoinflammatory diseases. Based on the genes involved, autoinflammatory diseases can be classified into monogenic and polygenic diseases.11,42 Monogenic autoinflammatory diseases are caused by abnormalities of a single gene and include FMF (MEFV), CAPS (NLRP3), deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN), TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TNFRSF1A), hyperimmunoglobulinemia D with periodic fever syndrome (MVK), and Blau syndrome (NOD2).11,42 Polygenic autoinflammatory diseases include gout and Crohn's disease.11,42 Most autoinflammatory diseases can be explained by the overproduction of IL-1, which occurs as a consequence of inflammasome activation.11 For example, FMF is the most prevalent hereditary autoinflammatory disease in the world and is characterized by recurrent one- to three-day attacks of fever, serositis presenting as abdominal or pleuritic chest pain, and arthritis.11,12 FMF is caused by mutations of the MEFV gene, which encodes pyrin.12 Although the association between FMF and pyrin mutations is well established, how pyrin mutation develops into FMF has not been explained. The MEFV gene does not belong to the NLRs family; however, the mutation of the MEFV gene leads to dysregulation of caspase-1, which is similar to the result of NLRP3 (NLR family, "pyrin" domain containing 3) activation.11 Nevertheless, the involvement of NLR genes with some autoinflammatory diseases reflects their important roles in inflammation.

Diseases associated with inflammasome-forming NLRs

Although several NLRs can form inflammasome,7,10 the NLRP3 inflammasome has been the most studied. Studies found that NLRP3 can recognize a wide range of endogenous and exogenous DAMPs such as uric acid, alum, silica, and asbestos.10 Below are descriptions of how NLRP3 is associated with gout, silicosis, asbestosis, and CAPS and how it is related to the role of alum as a vaccine adjuvant.

Gout is a common metabolic disease described from 2600 BC as podagra, although today it is understood as uric acid arthropathy.43 It is characterized by recurrent, sudden, and severe attacks of pain, redness, and tenderness in joints due to deposition of monosodium urate, a crystallized form of uric acid. However, it was unclear how uric acid could cause inflammatory events until uric acid was found to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.44 The NLRP3 inflammasome becomes activated in response to uric acid, and its activation induces the formation of IL-1, which leads to the development of gouty arthropathy. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that IL-1-blocking therapy results in significant relief of pain and a reduction in the occurrence of acute flare-ups in gouty patients.11

Silicosis, an occupational disease related to mining and con-struction work, is characterized by pulmonary fibrosis after inhalation exposure to silica. Asbestosis is a similar pulmonary fibrotic disorder following inhalation of asbestos. A recent study showed that silica and asbestos can cause alveolar macrophages to activate NLRP3 inflammasome and produce IL-1β, which leads to the development of pulmonary fibrosis.45

CAPS are rare autoinflammatory diseases, which include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle-Wells syndrome, and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease.46 Patients with CAPS usually present to physicians with overlapping symptoms such as fever, urticarial skin rash, varying degrees of arthralgia/arthritis, and neutrophil-mediated inflammation.46 CAPS are associated with gain-of-function mutations in the NLRP3 gene,46,47,48 with these mutations inducing an overproduction of IL-1β, which causes CAPS.46,47,48 When IL-1-blocking therapy was given to CAPS patients, significant clinical responses were reported.49

Aluminum hydroxide (alum) has been used as a vaccine adjuvant since the 1920s; however, its mechanism of action was unknown. However, recently, a link has been reported between alum and the NLRP3 inflammasome.50 Alum promotes local necrosis in vaccinated muscle tissue, which leads to the release of DAMPs such as uric acid. DAMPs as well as the alum itself activate NLRP3 inflammasome, which enhances the immune response to vaccine.50 Gaining a better understanding of the role that alum adjuvant plays in the immune response may lead to the development of new vaccine adjuvants.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the NLRP3 gene are associated with many disorders such as type 1 diabetes,51 celiac disease,51 psoriasis,52 increased susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infections,53 and inflammatory bowel diseases.54 NLRP3 is also associated with type 2 diabetes in obese individuals.55 NLRP3 inflammasome in adipose tissue macrophages senses ceramides generated from free fatty acids in obese patients, which can cause obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance.55 The development of an effective inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome could, thus, provide a potential therapeutic agent for these NLRP3-associated diseases.56

In addition to the NLRP3 inflammasome, the other NLR inflammasomes are also associated with many diseases. NLRP1 polymorphisms are significantly associated with vitiligo,57,58 celiac disease,59 Addison's disease,60,61 type 1 diabetes,60 autoimmune thyroid disorders,62 systemic lupus erythematosus,63 systemic sclerosis,64 giant cell arteritis,65 congenital toxoplasmosis,66 rheumatoid arthritis,67 Alzheimer's disease,68 and corneal intraepithelial dyskeratosis.69 NLRP2 gene mutations are associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, which is a congenital overgrowth syndrome associated with developmental abnormalities and a predisposition to embryonic tumors.70 NLRP6 expression is predominantly localized in intestinal tissue and is associated with increased susceptibility to colitis and colon cancer in a mouse model.71 Mutations in the maternal gene NLRP7 are associated with recurrent hydatid moles,72 and increased NLRP7 gene expression is observed in testicular seminoma73 and endometrial cancer.74 NLRP12 mutations are associated with atopic dermatitis75 and hereditary periodic fever syndrome.76 NAIP gene mutations are associated with spinal muscular atrophies that are characterized by autosomal recessive disorder and spinal cord motor neuron depletion.77

Diseases associated with non-inflammasome-forming NLRs

Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory disease in the gastrointestinal tract. Mutations of the NOD2 gene are associated Crohn's disease, although many patients with Crohn's disease do not have NOD2 mutations.25,78 Most NOD2 mutations (93%) in Crohn's disease patients are located in the leucine-rich-repeat region,4,78 which is responsible for ligand binding. Loss-of-function mutation of NOD2 prevents responses to bacterial MDP in the gut, which might lead to proliferation of commensal or pathogenic gut microbiota in the crypts and disruption of mucosal integrity.4

Mutations and SNPs of the NOD2 gene are also associated with Blau syndrome, which is characterized by familial granulomatous arthritis, uveitis, and skin granulomas.79 Atopic eczema,80 atopic dermatitis,75 and susceptibility to leprosy81 and tuberculosis82 are associated with NOD2 gene mutations. Polymorphisms of the NOD1 gene are linked to asthma83 and inflammatory bowel diseases.84

Bare lymphocyte syndrome type II, also called hereditary MHC class II deficiency, is a severe combined immunodeficiency that results from a lack of expression of MHC class II molecules in all tissues.35 Patients with this disease suffer from multiple infections and frequently die at an early age.35 Loss-of-function due to NLRA mutations leads to reduced expression of MHC class II genes that affect CD4+ T cell function, which in turn causes immune deficiency. Therefore, bare lymphocyte syndrome is an attractive candidate for gene therapy.

Breaks in the NLRA gene were found to occur in B-cell lymphomas, such as primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. In addition, NLRA gene alterations have been associated with decreased survival in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma.85

CONCLUSION

NLRs are important in the recognition of PAMPs and DAMPs; they also play a crucial role in immune response and pathogen detection. However, NLRs are also important in basic biologic processes, such as apoptosis and embryonic development. Many human NLRs remain poorly characterized and understood. Thus, as we learn more about the function of human NLRs, we will find their pathogenic roles in more diseases and develop novel strategies for treating and/or preventing these diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dong-Su Jang, MFA (Medical Illustrator, Medical Research Support Section, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea), for his help with the illustrations.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Janeway CA., Jr Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R. Approaching the asymptote: 20 years later. Immunity. 2009;30:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motta V, Soares F, Sun T, Philpott DJ. NOD-like receptors: versatile cytosolic sentinels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:149–178. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong E, Lee JY. Intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of innate immune receptors. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:379–392. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.3.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin J, Boss JM, Davis BK, et al. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong Y, Kinio A, Saleh M. Functions of NOD-Like Receptors in Human Diseases. Front Immunol. 2013;4:333. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koonin EV, Aravind L. The NACHT family - a new group of predicted NTPases implicated in apoptosis and MHC transcription activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:223–224. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01577-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jesus AA, Goldbach-Mansky R. IL-1 blockade in autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:223–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061512-150641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozkurede VU, Franchi L. Immunology in clinic review series; focus on autoinflammatory diseases: role of inflammasomes in autoinflammatory syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:382–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kufer TA, Sansonetti PJ. NLR functions beyond pathogen recognition. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:121–128. doi: 10.1038/ni.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, et al. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miao EA, Leaf IA, Treuting PM, Mao DP, Dors M, Sarkar A, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amer A, Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Ozören N, Brady G, et al. Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35217–35223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franchi L, Amer A, Body-Malapel M, Kanneganti TD, Ozören N, Jagirdar R, et al. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kofoed EM, Vance RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011;477:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamboni DS, Kobayashi KS, Kohlsdorf T, Ogura Y, Long EM, Vance RE, et al. The Birc1e cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor contributes to the detection and control of Legionella pneumophila infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:318–325. doi: 10.1038/ni1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang TJ, Basu S, Zhang L, Thomas KE, Vogel SN, Baillie L, et al. Bacillus anthracis spores and lethal toxin induce IL-1beta via functionally distinct signaling pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1574–1584. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khare S, Dorfleutner A, Bryan NB, Yun C, Radian AD, de Almeida L, et al. An NLRP7-containing inflammasome mediates recognition of microbial lipopeptides in human macrophages. Immunity. 2012;36:464–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jéhanno M, Viala J, et al. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science. 2003;300:1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, et al. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi K, Inohara N, Hernandez LD, Galán JE, Núñez G, Janeway CA, et al. RICK/Rip2/CARDIAK mediates signalling for receptors of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Nature. 2002;416:194–199. doi: 10.1038/416194a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruey JM, Bruey-Sedano N, Newman R, Chandler S, Stehlik C, Reed JC. PAN1/NALP2/PYPAF2, an inducible inflammatory mediator that regulates NF-kappaB and caspase-1 activation in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51897–51907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conti BJ, Davis BK, Zhang J, O'connor W, Jr, Williams KL, Ting JP. CATERPILLER 16.2 (CLR16.2), a novel NBD/LRR family member that negatively regulates T cell function. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18375–18385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui J, Li Y, Zhu L, Liu D, Songyang Z, Wang HY, et al. NLRP4 negatively regulates type I interferon signaling by targeting the kinase TBK1 for degradation via the ubiquitin ligase DTX4. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:387–395. doi: 10.1038/ni.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider M, Zimmermann AG, Roberts RA, Zhang L, Swanson KV, Wen H, et al. The innate immune sensor NLRC3 attenuates Toll-like receptor signaling via modification of the signaling adaptor TRAF6 and transcription factor NF-kB. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:823–831. doi: 10.1038/ni.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Lukens JR, Vogel P, Bertin J, Lamkanfi M, et al. NLRP6 negatively regulates innate immunity and host defence against bacterial pathogens. Nature. 2012;488:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lich JD, Williams KL, Moore CB, Arthur JC, Davis BK, Taxman DJ, et al. Monarch-1 suppresses non-canonical NF-kappaB activation and p52-dependent chemokine expression in monocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178:1256–1260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Girardin SE, Tournebize R, Mavris M, Page AL, Li X, Stark GR, et al. CARD4/Nod1 mediates NF-kappaB and JNK activation by invasive Shigella flexneri. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:736–742. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, et al. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. Implications for Crohn's disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabbah A, Chang TH, Harnack R, Frohlich V, Tominaga K, Dube PH, et al. Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/ni.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steimle V, Otten LA, Zufferey M, Mach B. Complementation cloning of an MHC class II transactivator mutated in hereditary MHC class II deficiency (or bare lymphocyte syndrome) Cell. 1993;75:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biswas A, Meissner TB, Kawai T, Kobayashi KS. Cutting edge: impaired MHC class I expression in mice deficient for Nlrc5/class I transactivator. J Immunol. 2012;189:516–520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi KS, van den Elsen PJ. NLRC5: a key regulator of MHC class I-dependent immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:813–820. doi: 10.1038/nri3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Travassos LH, Carneiro LA, Ramjeet M, Hussey S, Kim YG, Magalhães JG, et al. Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:55–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei Y, Wen H, Yu Y, Taxman DJ, Zhang L, Widman DG, et al. The mitochondrial proteins NLRX1 and TUFM form a complex that regulates type I interferon and autophagy. Immunity. 2012;36:933–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Shiina M, Ogata K, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F. NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic processes through an association with beclin1. J Immunol. 2011;186:1646–1655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGonagle D, McDermott MF. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pillinger MH, Rosenthal P, Abeles AM. Hyperuricemia and gout: new insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dostert C, Pétrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aksentijevich I, D Putnam C, Remmers EF, Mueller JL, Le J, Kolodner RD, et al. The clinical continuum of cryopyrinopathies: novel CIAS1 mutations in North American patients and a new cryopyrin model. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1273–1285. doi: 10.1002/art.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jesus AA, Silva CA, Segundo GR, Aksentijevich I, Fujihira E, Watanabe M, et al. Phenotype-genotype analysis of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS): description of a rare non-exon 3 and a novel CIAS1 missense mutation. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:134–138. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:301–305. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imagawa T, Nishikomori R, Takada H, Takeshita S, Patel N, Kim D, et al. Safety and efficacy of canakinumab in Japanese patients with phenotypes of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome as established in the first open-label, phase-3 pivotal study (24-week results) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oleszycka E, Lavelle EC. Immunomodulatory properties of the vaccine adjuvant alum. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;28:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pontillo A, Brandao L, Guimaraes R, Segat L, Araujo J, Crovella S. Two SNPs in NLRP3 gene are involved in the predisposition to type-1 diabetes and celiac disease in a pediatric population from northeast Brazil. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:583–589. doi: 10.3109/08916930903540432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlström M, Ekman AK, Petersson S, Söderkvist P, Enerbäck C. Genetic support for the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in psoriasis susceptibility. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:932–937. doi: 10.1111/exd.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontillo A, Brandão LA, Guimarães RL, Segat L, Athanasakis E, Crovella S. A 3'UTR SNP in NLRP3 gene is associated with susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:236–240. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181dd17d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179–188. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Muñoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:248–255. doi: 10.1038/nm.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alkhateeb A, Qarqaz F. Genetic association of NALP1 with generalized vitiligo in Jordanian Arabs. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:631–634. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin Y, Mailloux CM, Gowan K, Riccardi SL, LaBerge G, Bennett DC, et al. NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1216–1225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pontillo A, Vendramin A, Catamo E, Fabris A, Crovella S. The missense variation Q705K in CIAS1/NALP3/NLRP3 gene and an NLRP1 haplotype are associated with celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:539–544. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Magitta NF, Bøe Wolff AS, Johansson S, Skinningsrud B, Lie BA, Myhr KM, et al. A coding polymorphism in NALP1 confers risk for autoimmune Addison's disease and type 1 diabetes. Genes Immun. 2009;10:120–124. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zurawek M, Fichna M, Januszkiewicz-Lewandowska D, Gryczyn ´ska M, Fichna P, Nowak J. A coding variant in NLRP1 is associated with autoimmune Addison's disease. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:530–534. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alkhateeb A, Jarun Y, Tashtoush R. Polymorphisms in NLRP1 gene and susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity. 2013;46:215–221. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2013.768617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pontillo A, Girardelli M, Kamada AJ, Pancotto JA, Donadi EA, Crovella S, et al. Polimorphisms in inflammasome genes are involved in the predisposition to systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:271–278. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2011.637532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dieudé P, Guedj M, Wipff J, Ruiz B, Riemekasten G, Airo P, et al. NLRP1 influences the systemic sclerosis phenotype: a new clue for the contribution of innate immunity in systemic sclerosis-related fibrosing alveolitis pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:668–674. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Serrano A, Carmona FD, Castañeda S, Solans R, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Cid MC, et al. Evidence of association of the NLRP1 gene with giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:628–630. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Witola WH, Mui E, Hargrave A, Liu S, Hypolite M, Montpetit A, et al. NALP1 influences susceptibility to human congenital toxoplasmosis, proinflammatory cytokine response, and fate of Toxoplasma gondii-infected monocytic cells. Infect Immun. 2011;79:756–766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00898-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sui J, Li H, Fang Y, Liu Y, Li M, Zhong B, et al. NLRP1 gene polymorphism influences gene transcription and is a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis in han chinese. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:647–654. doi: 10.1002/art.33370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pontillo A, Catamo E, Arosio B, Mari D, Crovella S. NALP1/NLRP1 genetic variants are associated with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:277–281. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318231a8ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Soler VJ, Tran-Viet KN, Galiacy SD, Limviphuvadh V, Klemm TP, St Germain E, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies a mutation for a novel form of corneal intraepithelial dyskeratosis. J Med Genet. 2013;50:246–254. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meyer E, Lim D, Pasha S, Tee LJ, Rahman F, Yates JR, et al. Germline mutation in NLRP2 (NALP2) in a familial imprinting disorder (Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome) PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen GY, Liu M, Wang F, Bertin J, Núñez G. A functional role for Nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Immunol. 2011;186:7187–7194. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murdoch S, Djuric U, Mazhar B, Seoud M, Khan R, Kuick R, et al. Mutations in NALP7 cause recurrent hydatidiform moles and reproductive wastage in humans. Nat Genet. 2006;38:300–302. doi: 10.1038/ng1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Okada K, Hirota E, Mizutani Y, Fujioka T, Shuin T, Miki T, et al. Oncogenic role of NALP7 in testicular seminomas. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:949–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohno S, Kinoshita T, Ohno Y, Minamoto T, Suzuki N, Inoue M, et al. Expression of NLRP7 (PYPAF3, NALP7) protein in endometrial cancer tissues. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2493–2497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Macaluso F, Nothnagel M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, Bechara FG, Epplen JT, et al. Polymorphisms in NACHT-LRR (NLR) genes in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:692–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jéru I, Duquesnoy P, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Cochet E, Yu JW, Lackmy-Port-Lis M, et al. Mutations in NALP12 cause hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1614–1619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708616105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roy N, Mahadevan MS, McLean M, Shutler G, Yaraghi Z, Farahani R, et al. The gene for neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is partially deleted in individuals with spinal muscular atrophy. Cell. 1995;80:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cézard JP, Belaiche J, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miceli-Richard C, Lesage S, Rybojad M, Prieur AM, Manouvrier-Hanu S, Häfner R, et al. CARD15 mutations in Blau syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weidinger S, Klopp N, Rummler L, Wagenpfeil S, Novak N, Baurecht HJ, et al. Association of NOD1 polymorphisms with atopic eczema and related phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang FR, Huang W, Chen SM, Sun LD, Liu H, Li Y, et al. Genomewide association study of leprosy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2609–2618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Austin CM, Ma X, Graviss EA. Common nonsynonymous polymorphisms in the NOD2 gene are associated with resistance or susceptibility to tuberculosis disease in African Americans. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1713–1716. doi: 10.1086/588384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hysi P, Kabesch M, Moffatt MF, Schedel M, Carr D, Zhang Y, et al. NOD1 variation, immunoglobulin E and asthma. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:935–941. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McGovern DP, Hysi P, Ahmad T, van Heel DA, Moffatt MF, Carey A, et al. Association between a complex insertion/deletion polymorphism in NOD1 (CARD4) and susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1245–1250. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steidl C, Shah SP, Woolcock BW, Rui L, Kawahara M, Farinha P, et al. MHC class II transactivator CIITA is a recurrent gene fusion partner in lymphoid cancers. Nature. 2011;471:377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature09754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanna MG, da Silva Correia J, Ducrey O, Lee J, Nomoto K, Schrantz N, et al. IAP suppression of apoptosis involves distinct mechanisms: the TAK1/JNK1 signaling cascade and caspase inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1754–1766. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1754-1766.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang L, Mo J, Swanson KV, Wen H, Petrucelli A, Gregory SM, et al. NLRC3, a member of the NLR family of proteins, is a negative regulator of innate immune signaling induced by the DNA sensor STING. Immunity. 2014;40:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Benko S, Magalhaes JG, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. NLRC5 limits the activation of inflammatory pathways. J Immunol. 2010;185:1681–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tattoli I, Carneiro LA, Jéhanno M, Magalhaes JG, Shu Y, Philpott DJ, et al. NLRX1 is a mitochondrial NOD-like receptor that amplifies NF-kappaB and JNK pathways by inducing reactive oxygen species production. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:293–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhao Q, Peng L, Huang W, Li Q, Pei Y, Yuan P, et al. Rare inborn errors associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2012;56:1661–1670. doi: 10.1002/hep.25850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Minkiewicz J, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Keane RW. Human astrocytes express a novel NLRP2 inflammasome. Glia. 2013;61:1113–1121. doi: 10.1002/glia.22499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng H, Chang B, Lu C, Su J, Wu Y, Lv P, et al. Nlrp2, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in the mouse. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Manji GA, Wang L, Geddes BJ, Brown M, Merriam S, Al-Garawi A, et al. PYPAF1, a PYRIN-containing Apaf1-like protein that assembles with ASC and regulates activation of NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11570–11575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fernandes R, Tsuda C, Perumalsamy AL, Naranian T, Chong J, Acton BM, et al. NLRP5 mediates mitochondrial function in mouse oocytes and embryos. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:138, 1–10. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eisenbarth SC, Williams A, Colegio OR, Meng H, Strowig T, Rongvaux A, et al. NLRP10 is a NOD-like receptor essential to initiate adaptive immunity by dendritic cells. Nature. 2012;484:510–513. doi: 10.1038/nature11012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hirota T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Tsunoda T, Tomita K, Sakashita M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/ng.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vladimer GI, Weng D, Paquette SW, Vanaja SK, Rathinam VA, Aune MH, et al. The NLRP12 inflammasome recognizes Yersinia pestis. Immunity. 2012;37:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Westerveld GH, Korver CM, van Pelt AM, Leschot NJ, van der Veen F, Repping S, et al. Mutations in the testis-specific NALP14 gene in men suffering from spermatogenic failure. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3178–3184. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]