Abstract

Background

Acinetobacter baumannii is becoming an increasing menace in health care settings especially in the intensive care units due to its ability to withstand adverse environmental conditions and exhibit innate resistance to different classes of antibiotics. Here we describe the biological contributions of abeD, a novel membrane transporter in bacterial stress response and antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii.

Results

The abeD mutant displayed ~ 3.37 fold decreased survival and >5-fold reduced growth in hostile osmotic (0.25 M; NaCl) and oxidative (2.631 μM–6.574 μM; H2O2) stress conditions respectively. The abeD inactivated cells displayed increased susceptibility to ceftriaxone, gentamicin, rifampicin and tobramycin (~ 4.0 fold). The mutant displayed increased sensitivity to the hospital-based disinfectant benzalkonium chloride (~3.18-fold). In Caenorhabditis elegans model, the abeD mutant exhibited (P<0.01) lower virulence capability. Binding of SoxR on the regulatory fragments of abeD provide strong evidence for the involvement of SoxR system in regulating the expression of abeD in A. baumannii.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the contributions of membrane transporter AbeD in bacterial physiology, stress response and antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii for the first time.

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a nosocomial pathogen that causes a wide range of clinical illnesses in immunocompromised patients including bacteremia, pneumonia, meningitis, urinary tract, wound and skin infections [1]. Overall mortality rates for nosocomial Acinetobacter infection have been reported to range from 19 to 54% [2, 3]. A report from India suggests that around ~ 10% of all hospital-acquired infections were caused by A. baumannii [4, 5]. The pathogen has attracted the attention of researchers globally as it has the ability to attain antibiotic resistance genes, resist desiccation and stay on abiotic surfaces for long [1]. Though A. baumannii has the ability to acquire additional resistance elements, overproduction of membrane transporters having wide spectrum antibiotic preference is also well correlated with the multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype displayed by this notorious human pathogen [6, 7]. The efflux pumps in prokaryotic kingdom are structurally diverse and belong to one of the five different super families: major facilitator super family (MFS), multiple antimicrobial and toxic compounds extrusion family (MATE), small multidrug resistance family (SMR) ATP-binding cassette family (ABC) and resistance nodulation cell division family (RND). Among these, the RND-type efflux pump is the predominant one known to be involved in antibiotic resistance across Gram-negative bacteria [8, 9, 10].

The first characterized efflux pump AdeABC is regulated by AdeRS and Magnet et al has demonstrated its specificity to different classes of antibiotics [11, 12]. Damier et al identified the AdeN modulated intrinsic tripartite efflux pump AdeIJK and demonstrated its functions in conferring broad-spectrum antimicrobial resistance [13, 14]. Coyne et al demonstrated functions of LysR regulated AdeFGH in mediating increased resistance to diverse substrates [15]. The clinical isolate A. baumannii AYE strain (Genbank accession number: NC_010401, 4 Mb, 3712 proteins, GC: 39.3% with 86Kb resistance island) was involved in national level outbreak in France in 2001 and is known to harbor several genes annotated as putative efflux pumps [16]. Our subsequent analysis revealed the presence of an uncharacterized open reading frame [lacking cognate membrane fusion protein (MFP) and outer membrane protein (OMP)] that exhibited identity to AcrD-like transporter genes. Here, we have elucidated the unprecedented physiological contributions of the acrD homolog (designated as abeD) and its regulation in A. baumannii for the first time.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, media and methods

A. baumannii AYE strain was procured from ATCC. E. coli KAM32, a highly susceptible strain that lacks major multidrug efflux pumps (acrAB and ydhE) was used as a host for heterologous studies (kindly provided as a gift by Dr. Tomofusa Tsuchiya). The Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar (Difco, Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) was used and 400 mg/L hygromycin or 200 mg/L zeocin was added when required. Standard techniques were performed following manufacturer’s instruction or as described previously [17, 18, 19]. Custom-synthesized primers were used in this study (Eurofins MWG operons, Germany).

Generation of ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD constructs in A. baumannii

The putative acrD homolog, ABAYE0827 (designated abeD) spans from nucleotides 884427 to 887522 bps (abeD: 3096bp, 1031aa, 113Kda) in genome sequence of A. baumannii AYE. A 930bp partial gene was amplified by PCR using ΔabeD-F/ΔabeD-R primers (Table 1) and cloned into hygromycin cassette containing pUC4K derived suicide vector. The recombinant construct pUC-abeD was electroporated into A. baumannii, and disruption was confirmed by Southern and sequencing analysis, the obtained strain was denoted as ΔabeD. With zeo-NT and zeo-CT primers (Table 1), the zeocin resistance marker was amplified from pCR Blunt II-TOPO vector (Life Technologies) and cloned into the shuttle vector pWH1266. Using FLabeD-F and FLabeD-R primers (Table 1), the full-length transporter gene along with its promoter was cloned in the modified pWH1266. The generated construct was electroporated into ΔabeD to obtain the complemented strain ΔabeDΩabeD.

Table 1. Primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Primer sequences (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| ΔabeD-F | ATTCAGACCTCTAAGCTCATCCACCAAACT |

| ΔabeD -R | AAAGTTTTCGAAAGTTGAATAATTTTTACT |

| FLabeD -F | GACTCAAGTTTCGGTGCTTTGTTTGACATGATCATGAAGAATT |

| FLabeD-R | GAAAAGTTAATCTTAATATACTTGATTTGATGCCCGTTTT |

| zeo-NT | ACATTCAAATATGTATCCGCTCATGAGACAATAAC |

| zeo-CT | TCAGTCCTGCTCCTCGGCCACGAAGTGCACGC |

| AB2390-NT | TATACATATGAGTGAAAGGAATCAAAGTCGTTTG |

| AB2390-CT | TCTAGGATCCCTATGGTCTTTCTAAAATACGTGG |

| promabeD-F | GGCTGCTCGGTATGATGTCGTTAATTAACA |

| promabeD-R | TGCTTTGTTTGACATGATCATGAAGAATTC |

| AB0827RTF | ATTGGTTTAGCGTGGACAGG |

| AB0827RTR | ATAGATGTCATTACGGCGGC |

| RTrpoBNT | GCGGTTGGTCGTATGAAGTT |

| RTrpoBCT | TGGCGTTGATCATATCCTGA |

Bacterial growth curves

The growth profile of WT (control strain: A. baumannii, AYE), ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD were examined in LB broth having different pH [17, 20]. Absorbance was measured continuously for 10h at an interval of every 30 mins at OD600nm using Bioscreen C automated growth analysis system (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). Every time the media was prepared freshly and independent experiments were carried out and the average of such three experiments is plotted here.

Growth inhibition assay

The growth inhibition assay to identify the occurrence of active efflux was performed as mentioned before with slight modifications [17, 20]. The WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD cultures at OD600nm = 0.1 were inoculated into LB medium with gentamicin (16.0 mg/L) in different experiments either alone or with efflux pump inhibitor phenylalanine arginyl β-naphthylamide; PAβN at 25mg/L or 50mg/L (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The growth of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD was measured at OD600nm at 37°C periodically in Bioscreen C automated growth analysis system. Other inhibitors carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone; CCCP 2.5 mg/L, 2, 4, Dinitrophenol DNP 2.5 mg/L; verampamil; VER 2.5 mg/L, reserpine; RES 2.5 mg/L (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were also used in our study in independent experiments. The experiments were performed at least six times.

Assays to measure motility behavior and biofilm forming ability

For motility assay, the A. baumannii cultures grown to OD600nm = 1.0 was spotted in the center of the plate having different agar concentrations and incubated for 10h at 37°C [17, 20]. Upon their growth in an outward manner they formed a halo and the diameter indicated their extent of motility. Crystal violet binding assay to estimate biofilm forming ability was performed as described before [17, 20]. Cultures grown to OD600nm = 0.1 was inoculated into LB broth and incubated at 37°C shaking for 24 hours. The biofilm was stained and reading was taken at OD570nm using Synergy H1 Hybrid microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski VT).

Oxidative and nitrosative challenge assays

As to test the role of abeD in oxidative stress tolerance, disc assay was performed in which paper disks were treated with various amount of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), air dried as reported before [21, 22]. The WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD were grown to OD600nm = 0.1 and plated on an agar plate. The paper disks were placed at the center and incubated at 37°C, the zone of inhibition was measured after 16h. Growth capabilities of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD in presence of different amounts of H2O2 were monitored and compared with WT by measuring the absorbance at OD600nm periodically in Bioscreen C automated growth analysis system [17]. The survival ability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to different oxidative challenges was tested as described before [17]. Acidified sodium nitrite and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were used to generate nitrosative stress and ability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to withstand the stress of these NO-releasing agents were tested as reported before [17, 23].

Various stress challenge assays

The survival capability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to different stress conditions at various concentrations was performed as mentioned before [17, 20]. In this study wide range of substrates were tested for e.g. sodium chloride (NaCl), bile salt deoxycholate, antibiotics (gentamicin, kanamycin, neomycin), efflux pump substrates (ethidium bromide (EtBr), acriflavine, saffranine) and disinfectants (benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine and triclosan). All experiments were carried out independently for three times.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing and OMP preparation

Analysis of antibiotic susceptibilities for WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD was examined using commercial discs (Hi-Media, Bombay, India) as described previously following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [17, 20]. The antibiotics tested were amikacin: AMK (10 mg/L), ampicillin: AMX (30 mg/L), ceftazidime: CAZ (30 mg/L), chloramphenicol: CHL (30 mg/L), clindamycin: CLD (10 mg/L), colistin: CST (10 mg/L), ceftriaxone: CTR (10 mg/L), gentamicin: GEN (30 mg/L), kanamycin: KAN (30 mg/L), methicillin: MET (30 mg/L), minocycline: MIN (10 mg/L), meropenem: MRP (10 mg/L), nalidixic acid: NAL (30 mg/L), neomycin: NEO (30 mg/L), ofloxacin: OFL (10 mg/L), oxacillin: OXA (10 mg/L), piperacillin: PIP (10 mg/L), polymyxin B: PMB (300 mg/L), rifampicin: RIF (30 mg/L), spectinomycin: SPT (10 mg/L), sparfloxacin: SPX (30 mg/L), tetracycline: TET (30 mg/L), ticarcillin: TIC (75 mg/L), tobramycin: TOB (30 mg/L) and vancomycin: VAN (10 mg/L). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for different antibiotics was determined using either E-strips or spotting on agar plates with different antibiotic concentrations as described before [17]. The OMPs from WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD were prepared following procedure as described previously [17].

Fluorimetric efflux studies

The fluorimetric EtBr assay was carried out as mentioned briefly. The cultures were grown to OD600nm = 0.6 and pelleted. Further it was washed in PBS and resuspended to OD600nm = 0.3. Glucose was added to the cellular suspension to a final concentration of 0.4% (v/v) and aliquots of 0.095 ml were transferred to 96 well plate. EtBr was added in aliquots of 0.005 ml to obtain final concentrations that ranged from 1.0 to 6.0mg/L. The fluorescence at emission 600nm/excitation 530nm was monitored for one hour in Synergy H1 Hybrid microplate reader and automatically recorded for each well after every 1 min at 37°C under the conditions described above. The effect of inhibitor CCCP in the accumulation of EtBr was determined under conditions that optimize efflux (presence of glucose and incubation at 37°C). The experiment was performed with the freshly autoclaved medium in triplicates at least six independent times before plotting the graph.

Cloning of SoxR regulator and Gel shift assays

The A. baumannii strain AYE (4 Mb, 3712 proteins, GC: 39.3% with 86Kb resistance island) has ~ 214 signaling proteins in its genome www.mistb.com and functions of only few have been elucidated so far [16]. The MerR type DNA-binding HTH-type transcriptional regulator ABAYE2390 (soxR; 453bp, 150aa and 17.01 kDa) was cloned and expressed in our lab in our previous study. The purified protein and the radiolabelled abeD promoter fragment was used in gel shift assay. The binding specificity was confirmed using appropriate controls as described previously [17, 20].

RNA isolation and real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the log-phase cultures using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA isolation was done two independent times, quantified and PCR reactions with Maxima SYBR Green qPCR master mix (Fermentas) were performed using gene specific primers [17]. In the RT-PCR analysis rpoB (RTrpoBNT/CT) was used as an internal control and the specific amplification was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [24], and the experiments were performed more than three times.

Caenorhabditis elegans killing assay

Bacterial virulence assays were performed using nematode model, C. elegans strain Bristol N2 as reported previously [25]. To examine the ability of WT, ΔabeD, ΔabeDΩabeD and E. coli OP50 strains to kill C. elegans, bacterial lawns of A. baumannii and E. coli control strain were prepared on nematode growth (NG) media and incubated at 37°C for 6h. The plates were kept at room temperature for 1hr and then seeded with L4-stage worms (25 to 30 per plate). Further, the seeded plates were incubated at 25°C and examined for live worms under a stereomicroscope (Leica MS5) after every 24 hours. When the worm did not react to touch, it was considered dead. For each strain, experiments were performed three times with five replicates respectively.

Cloning of abeD in E. coli KAM32 for heterologous studies

The uncharacterized abeD homolog was amplified using primer pairs FLabeD-F/FLabeD-R, and cloned into PCR-XL-TOPO vector (Invitogen) following standard procedures. The obtained recombinant construct pabeD was transformed into E. coli KAM32 to obtain E. coli KAM32/pabeD which was further used for antibiotic susceptibility, oxidative disc and fluorimetric assays for functional characterization.

Bioinformatic analysis and Statistical analysis

To perform the homology searches, similarity and identity analysis, conserved domain architecture analysis, NCBI internet server was used. Data are shown as an average ± the standard error. Standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft-Excel. On raw data, statistical analysis was done with the help of paired Student’s t-test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

In silico analysis of RND type membrane transporter AbeD

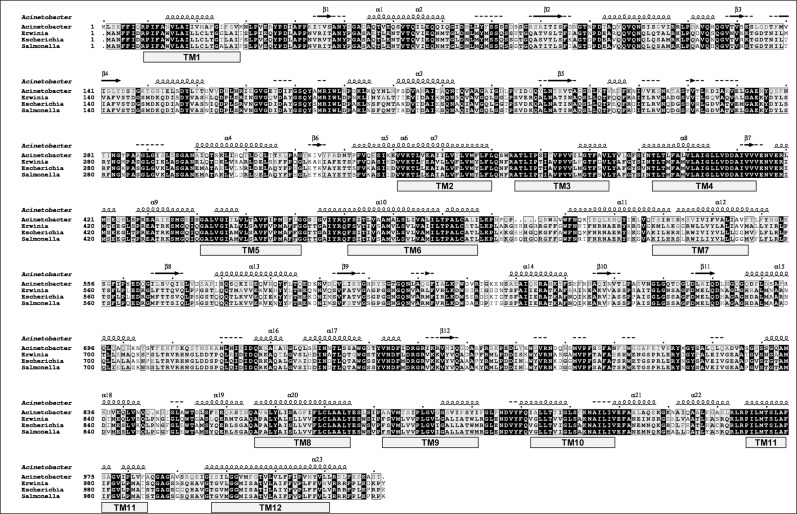

The transporter AbeD is a 1031 aa long protein, predicted to be a member of Gram-negative bacterial hydrophobe/amphiphile efflux-1 family that belongs to RND superfamily. The sequence alignment of AbeD displays 47.1% identity and 68.5% similarity to the E.coli AcrD protein, 47.6% identity and 68.8% similarity with AcrD of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, 47.7% identity and 69.5% similarity with AcrD of Erwinia amylovora, 53.6% identity and 74.8% similarity with AcrD of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (YP_002027309.1), ~ 53.6 to ~ 54.9% identity and ~ 74.9% similarity with AcrD of A.venetianus (ENV36179.1), A. oleivorans (ADI89711.1), A. nosocomialis (ERL67989.1), A. guillouiae (ENU59765.1), 61.4% identity and 80.5% similarity with AcrD of Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 (ACIAD2836) [Fig 1]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using AbeD and other characterized members of Enterobacteriaceae and AbeD formed a separate cluster, indicating that it’s divergent from its homologs (data not shown). The AbeD protein is conserved (100% identity) across different A. baumannii strains (YP_002324730.1, YP_002320396.1, EJO40799.1, EKL39351.1 and EKP54977.1). The clustal comparison of proteins exhibited that they were well conserved across Acinetobacters. Further analysis of AbeD revealed the presence of β-sheet, α-helical domains, and 12 transmembrane domains. Interestingly, the essential charged residues in E.coli AcrB in the transmembrane domain, D408, D409, E415 (in TM4), K933 (in TM10) and T970 (in TM11) are well conserved in AbeD, which are responsible for proton relay pathway / transport. Overall, in silico analysis suggests that AbeD is indeed an putative transporter protein that belongs to the RND-type and its characterization would shed let light on its biological relevance.

Fig 1. Alignment of multiple AbeD sequences and its homologs.

Sequence alignments were made in CLUSTAL Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo) and formatting using the ESPript server (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi). The accession numbers of AbeD from A. baumannii is CAM85780.1, Erwinia amylovora ATCC 49946 is YP_003539485.1, Escherichia coli is YP_490697.1, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is ADX18241.1. The predicted secondary structural elements of A. baumannii AbeD are shown on the lines above the sequence alignment using PSIPRED (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred). Transmembrane regions TM1 to TM12 were predicted using HMMTOP (http://www.enzim.hu/hmmtop/index.php). The arrows indicate β-sheet and the coils indicate α-helices respectively. Residues strictly conserved have a black background and is indicated by bold letters; residues conserved between groups are boxed.

Characterization of AbeD in heterologous host

Here, we deciphered the functions of AbeD in E. coli KAM32. The antibiotic susceptibilities indicated that abeD does confer drug resistance in heterologous host [S1A Fig], but to get a clearer picture, the precise MICs were determined. The abeD—transformed cells (E. coli KAM32/pabeD) displayed higher (fold increase in brackets) MIC for erythromycin (4-fold), ertapenem (5-fold), and amikacin (2.7-fold) [Table 2]. Results obtained from oxidative disc assay indicated the importance of AbeD transporter in conferring tolerance against oxidative stress [S1B Fig]. The fluorimetric efflux assay using EtBr as a substrate confirmed the functions of AbeD in active efflux mechanism [S1C and S1D Fig]. To elucidate the functions of membrane transporter in native host, the gene was inactivated and various experiments were performed to delineate its physiological relevance by using A. baumannii AYE as the model strain.

Table 2. Determination of MIC for KAM32/pabeD and KAM32/vector.

| Antibiotics | KAM32/vector | KAM32/pabeD | Fold change a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | 0.75 | 2 | 2.66 |

| Amoxycillin/Sulbactam | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | 0.75 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Erythromycin | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Ertapenem | 0.012 | 0.064 | 5.33 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.023 | 0.058 | 2.51 |

| Meropenem | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Ticarcillin | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Trimethoprim | 0.032 | 0.064 | 2 |

E-strips were used to determine the precise MIC for different group of antibiotics such as Amikacin, Amoxycillin/Sulbactam, Ceftazidime, Clindamycin, Erythromycin, Ertapenem, Levofloxacin, Meropenem, Ticarcillin and Trimethoprim following the CLSI guidelines.

Novel contributions of AbeD in general physiology in A. baumannii

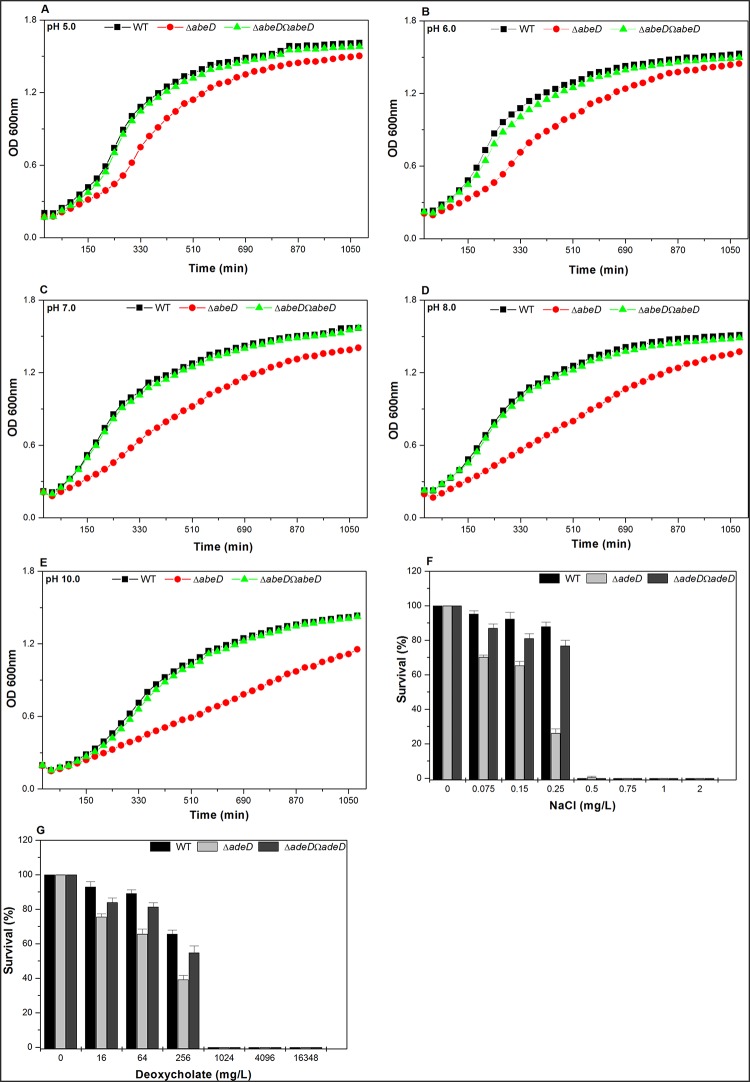

Southern analysis and DNA sequencing confirmed the inactivation of abeD in A. baumannii AYE [S2 Fig] and the constructs were further used for functional characterization. Analysis of growth profiles in LB at different pH revealed that abeD mutant exhibited 1.62-fold ± 0.0215 (at pH 5.0) [Fig 2A], 1.65-fold ± 0.06 (at pH 6.0) [Fig 2B], 1.72-fold ± 0.036 (at pH 7.0) [Fig 2C], 1.85-fold ± 0.057 (at pH 8.0) [Fig 2D] and 1.6 fold ± 0.047 (at pH 10.0) [Fig 2E] stunted growth compared to WT strain respectively (P<0.001). Overall results demonstrated that loss of abeD did affect the growth capability in A. baumannii. Secondly, on spotting the cultures on plates with different agar concentrations, the WT profusely grew outwardly from the point of inoculation while the mutant could not; clearly indicating the loss in motility behavior [S3A Fig]. Thirdly the adherence property of strains was tested by measuring their ability to form biofilm and we found ΔabeD exhibited only ~ 1.2-fold ± 0.047 lesser ability compared to WT strain [S3B Fig] which tells that role of AbeD in this phenomenon was merely marginal. The capability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to grow under different osmotic stress challenges were tested, and in the presence of 0.25M NaCl, survival ability of WT was ~ 3.37 fold ±0.017 higher in comparison to ΔabeD irrespective of the starting inoculum of the culture (P = 0.0119) [Fig 2F]. When tested with sodium deoxycholate (bile salt), for e.g. in the presence of 256 mg/L of salt, survival ability of WT was ~ 1.67 fold higher (±0.022) compared to ΔabeD (P = 0.005) [Fig 2G]. Conclusively, we found abeD disruption affected bacterial growth and ability to tolerate gastrointestinal-like stress challenges.

Fig 2. Impact of abeD disruption on growth and physiology in A. baumannii.

The influence of AbeD on growth of bacteria was monitored in WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD in LB medium at pH (5.0 (A), 6.0 (B), 7.0 (C), 8.0 (D), 10.0 (E). The average of independent experiments done three times is used to plot the graph. The survival capability of native strain to grow in the presence of NaCl was monitored and it was higher when compared to ΔabeD regardless of the inoculum size (F). The capacity of WT to grow in the presence of deoxycholate was compared to ΔabeD, the completely transcomplemented ΔabeDΩabeD strain restored the ability to tolerate the stress (G).

Functions of AbeD in oxidative and nitrosative stress tolerance in A. baumannii

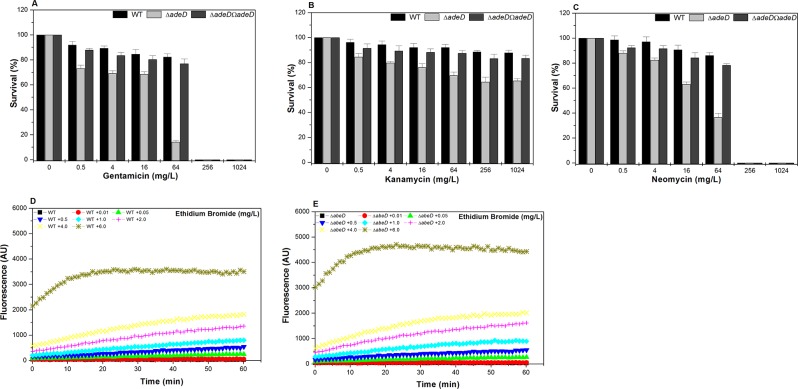

The H2O2 disc assay showed that the abeD mutant at 2.631μM was 1.78-fold and 5.262 μM was 1.52-fold sensitive than the wild-type (P = 0.00467) [Fig 3A]. The abeD mutant displayed 9.67-fold (P = 0.0003) [mean of fold differences of growth for WT/mutant for 18h], 5.49-fold (P = 0.0002), 8.52-fold (P = 0.0005), 4.24-fold (P = 0.0006) decreased growth with respect to WT in LB in presence of 2.631 μM, 3.9465 μM, 5.262 μM and 6.5775 μM concentrations of H2O2 respectively [Fig 3B]. In oxidative survival assay, the abeD mutant exhibited 1.6-fold (P = 0.0011) and 2.4-fold (P = 0.00032) reduced survival compared to WT strain when exposed to 2.3682 mM and 3.1576 mM concentrations of H2O2 respectively [Fig 3C]. The contribution of abeD in mediating protection against nitrosative stress response was tested similarly as mentioned above and we found that the ability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to grow in LB broth containing SNP and nitrite in different concentrations at pH 7.0 and 6.0 was only marginally affected. Survival assay using SNP also reconfirmed our observations [data not shown]. Therefore, results depict the crucial contributions of AbeD in salvaging against oxidative assails in A. baumannii for the very first time.

Fig 3. Hydrogen peroxide stress assays.

A, The behavior of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD strains. The ability of WT, ΔabeD to resist various levels of H2O2 was tabulated performing disc diffusion assay and ΔabeD remained sensitive to the challenges. B, The impact of various concentrations of H2O2 on the growth ability of WT and ΔabeD. The differences between WT and ΔabeD are statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all different H2O2 concentrations used. C, The survival ability of WT and ΔabeD towards varied concentrations of H2O2 was elucidated as described previously. The differences between WT and ΔabeD are statistically significant (P < 0.05) for all concentrations used.

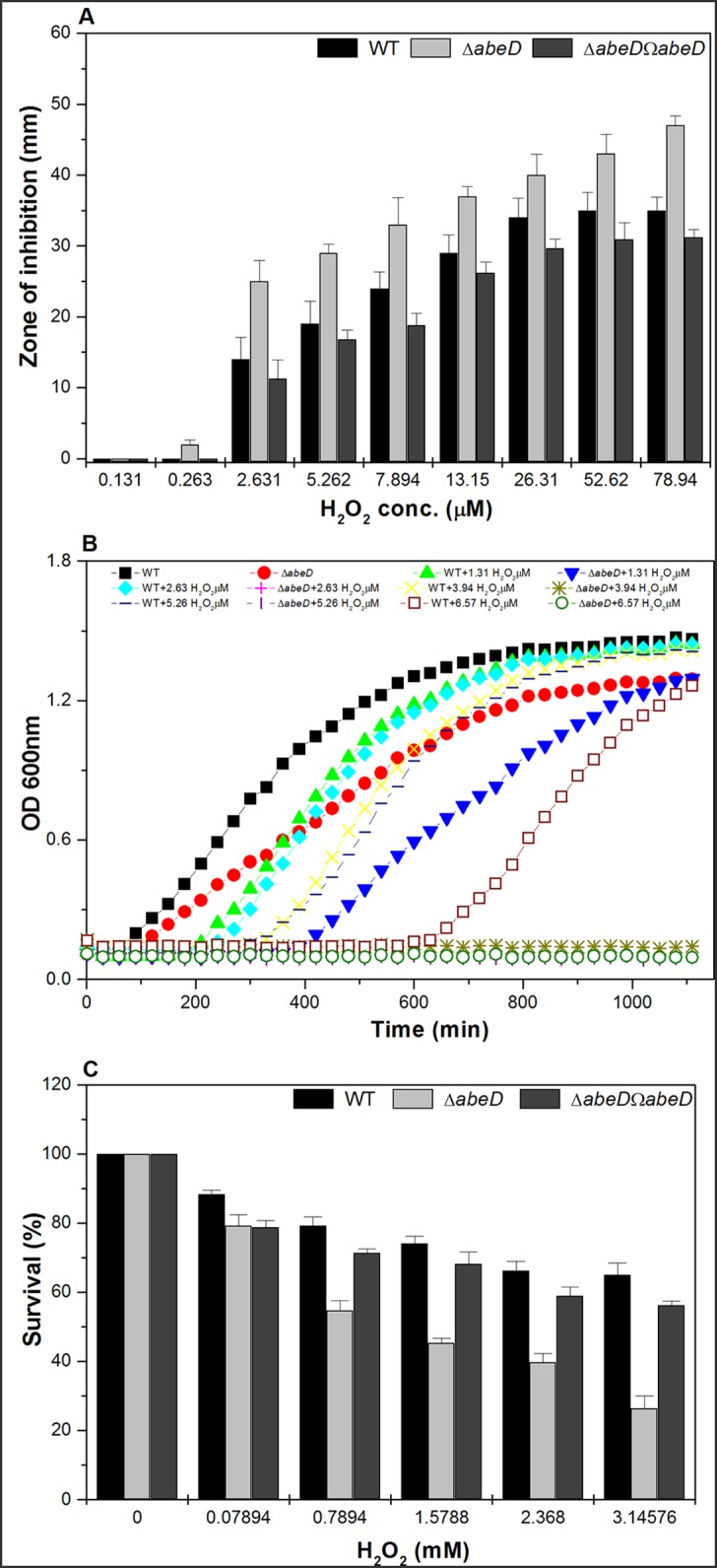

Prominent functions of AbeD in mediating antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii

The study illustrated that ΔabeD showed increased susceptibility towards ceftriaxone, gentamicin, rifampicin, and tobramycin [Table 3]. The survival ability of WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD to different classes of antibiotics were tested, and WT displayed higher survival ability compared to mutant e.g. gentamicin (P = 0.010, Fig 4A), kanamycin (P = 0.002, Fig 4B) and neomycin (P = 0.0016, Fig 4C). Interestingly, the total CFU count of WT at 64 mg/L of gentamicin and neomycin was 5.825-fold ± 0.058 and 2.361-fold ± 0.078 higher than ΔabeD cells respectively. Overall, results demonstrate that abeD is a novel multidrug resistance determinant in A. baumannii. Similarly, the abeD mutant cells showed decreased survival ability when exposed to various efflux based substrates such as EtBr (P = 0.0201, S4A Fig), acriflavine (P = 0.034, S4B Fig), safranin (P = 0.0014, S4C Fig) indicating AbeD transporter to have broad substrate specificity.

Table 3. MIC determination for different antibiotics using WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD.

| Antibiotics | WT | ΔabeD | Fold change a | ΔabeDΩabeD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin | 256 | 128 | 2 | 256 |

| Cefepime | 256 | 128 | 2 | 256 |

| Ceftriaxone | 256 | 64 | 4 | 256 |

| Ertapenem | >32 | 16 | 2 | >32 |

| Erythromycin | 16 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| Gentamicin | 128 | 32 | 4 | 128 |

| Neomycin | 60 | 30 | 2 | 60 |

| Norfloxacin | 240 | 120 | 2 | 240 |

| Piperacillin | 120 | 60 | 2 | 120 |

| Rifampicin | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Tobramycin | 10 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| Vancomycin | 8 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

E-strips were used to determine the precise MIC for different group of antibiotics such as amikacin, cefepime, ceftriaxone, ertapenem, erythromycin, gentamicin, neomycin, norfloxacin, piperacillin, rifampicin, tobramycin and vancomycin following the CLSI guidelines. Units for MIC values are mg/L and only few representative drugs are shown here.

a Fold change is the ratio of MICs for WT and ΔabeD.

Fig 4. Contributions of AbeD in antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii.

Survival assays using gentamicin (A), kanamycin (B), neomycin (C) are shown in bar graphs. Using the A. baumannii strains WT (D) and ΔabeD (E) cells EtBr accumulation assay at final concentrations that ranged from 0.01 mg/L to 6.0 mg/L was tested as described in methods section. The fluorescence was monitored in spectrofluorometer (Hitachi) at 37°C.

Impact on active efflux capability in abeD isogenic mutant in A. baumannii

Growth inhibition assay using different substrates and efflux pump inhibitor were performed for e.g. gentamicin; 16.0 mg/L, with PAβN 25 mg/L [S4D Fig] or PAβN 50 mg/L [S4E Fig]; and kanamycin [data not shown] which pinpointed lower growth by mutant indicating diminished efflux capacity in the disrupted construct. To verify the crucial role of AbeD in active efflux, cells were processed as described before to decipher the difference in accumulation ability between WT and ΔabeD using the efflux substrate EtBr. As the mutant lacks functional AbeD transporter, the degree of fluorescence was lower in WT [Fig 4D] relative to mutant [Fig 4E]. We also observed variations in OMP profile indicating expression of additional proteins for e.g. ~25 kDa, ~35 kDa and ~40 kDa possibly to oppose MDR stress in ΔabeD (data not shown). Overall results converge to say that AbeD is involved in conferring MDR exploiting active efflux mechanism.

Disinfectant challenge assays using WT and abeD isogenic mutant

Assays using WT, abeD and abeDΩabeD in presence of varied concentrations of benzalkonium chloride [P = 0.025] [S5A Fig], chlorhexidine [P = 0.017] [S5B Fig] and triclosan [P = 0.0259] [S5C Fig] and growth inhibition assay with chlorhexidine [data not shown] authenticated the ability of AbeD in conferring biocide resistance in A. baumannii. So far data discussed in this report demonstrate that AbeD possess wide substrate preference and confers antimicrobial resistance by active efflux mechanism in A. baumannii.

Expression analysis in A. baumannii

The expression of abeD was deciphered in different clinical strains from our collection. (Strains were randomly collected, from different Medical centers in India, isolated during 2012–2014; identified by gyrA sequencing; extremely MDR; diversity of resistome identified; manuscript under preparation). The expression of abeD relative to the sensitive strain A. baumannii SDF, was checked in A. baumannii AYE and 10 different MDR strains and we found an increased expression of abeD transporter (4.92 to 12.13 ± 2.21 fold) (P<0.005, Student's t-test). The transcription of other resistance genes in the mutant was also analyzed which was found to be increased as shown in Table 4. We postulate that to compensate for the loss of functional abeD, probably the mutant is exhibiting increased expression of other efflux pumps as shown in Table 4. Overall, study conclusively proves abeD to be the novel addition in the arsenal of multidrug resistance determinants in A. baumannii.

Table 4. Expression analysis in WT and abeD mutant strains.

| Gene | Description | Average fold change |

|---|---|---|

| ABAYE1822 | adeB; RND protein; K18146 multidrug efflux pump | 9.05 ±2.05 |

| ABAYE1823 | adeC; outer membrane protein; K18147 outer membrane protein | 6.4 ±1.84 |

| ABAYE0747 | RND protein (AdeB-like); K18138 multidrug efflux pump | 17.8 ±2.12 |

| ABAYE0746 | outer membrane protein AdeC-like; K18139 outer membrane protein | 11.8 ± 2.32 |

| ABAYE3381 | norM; multidrug ABC transporter; K03327 multidrug resistance protein, MATE family | 1.52 ± 0.87 |

| ABAYE1181 | multidrug resistance efflux protein; K03297 small multidrug resistance family protein | 1.15 ±0.74 |

| ABAYE3515 | hypothetical protein; K03298 drug/metabolite transporter, DME family | 3.48 ±0.98 |

| ABAYE3514 | tolC; channel-tunnel spanning the outer membrane and periplasm segregation of daughter chromosomes | 5.21 ±1.03 |

| ABAYE0640 | Outer membrane protein OmpA-like | 2.0 ±0.57 |

| ABAYE0924 | porin protein associated with imipenem resistance | 12.13 ±2.63 |

Impact of abeD in virulence

The Caenorhabditis elegans—A. baumannii infection model was employed to determine the involvement of abeD in virulence [25]. The WT and ΔabeD strains were examined for their abilities to kill C. elegans. The wild type strain displayed 12% and 25% killing at 96 and 120 h respectively. However, the mutant strain killed only 6% of the worms after 96 h (P<0.01). The E.coli strain OP50 was used as negative control. Thus, our findings demonstrate that the abeD mutant kills C. elegans more slowly than WT strain.

Regulatory role of SoxR on abeD in A. baumannii

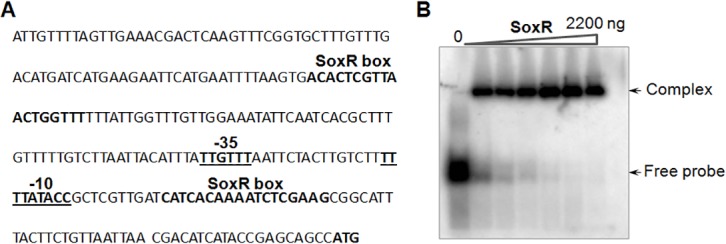

Promoter region analysis of abeD indicates presence of putative SoxR binding site [Fig 5A] and to decipher the possible interaction of SoxR with the promoter of abeD, gel shift assays using purified SoxR and 32P-labeled abeD promoter fragment was performed. Data analysis demonstrated clear retardation of complexes on autorad and binding was found specific on using appropriate controls [Fig 5B].

Fig 5. SoxR regulates abeD in A. baumannii.

A, The sequence analysis of the promoter region of efflux gene abeD. The distance from start site is shown as numbers within brackets. The underlined regions represent the -35 and -10 region of the promoter. The probable SoxR attaching site has been bolded. B, Binding assays using SoxR protein to promoter region of abeD was tested at various concentrations. Lane 1: represents free probe, lanes 2–7 represents different protein range of SoxR regulator (0–2200ng) respectively.

Discussion

Bacteria extrude drugs predominantly via tripartite multidrug efflux pumps spanning both inner and outer membranes and the periplasm. Besides, bacteria also possess orphan membrane transporter without their cognate membrane fusion protein in their genomes. Such transporters have been identified in many bacteria and well characterized in E. coli, popularly known as AcrD and their substrate specificity have been reported previously [26]. AcrD is known to have 12 transmembrane-spanning domains (TMD) and 2 large periplasmic loops.

Importantly, no report discusses the functions of the uncharacterized AcrD homolog in A. baumannii though it is present in all sequenced genomes including ABAYE0827 in A. baumannii AYE strain, ACICU_02904 in A. baumannii ACICU; AB57_3075 in A. baumannii AB0057; ABBFA_000816 in A. baumannii AB307-0294; ABK1_2958 in A. baumannii 1656–2; A1S_2660 in A. baumannii ATCC 17978 and ACIAD2836 in Acinetobacter sp. ADP1. In this report, we discuss the functions of AcrD homolog (RND-type transporter), abeD in mediating stress response and antimicrobial resistance in the human pathogen A. baumannii.

Recently, Hood et al, has demonstrated that exposure of A. baumannii to 0.2 M of NaCl, up-regulates expression of 150 genes, of which 20% are classified as transport proteins and precisely 14 belonged to different classes of efflux pumps including the RND-type [27]. Interestingly we found a ~ 3.37 fold reduced ability of ΔabeD to survive under high osmotic stress relative to its native strain irrespective of bacterial inoculum indicating a possible role of abeD in osmotic stress tolerance. The pathogen resists high bile salt to persist in the host. In Helicobacter pylori hefABC efflux pump is demonstrated to have a role in bile resistance [28] and similar involvement of abeD in bile tolerance adds to the understanding on multifaceted functions of RND efflux pumps in bacteria. The abeD mutant was found sensitive to H2O2 than WT indicating that AbeD might participate alone or along with additional factors to extrude the reactive oxygen radicals and help the pathogen survive inside the host, studies to prove the postulate is strictly warranted. Preliminary evidence for the role of AbeD in virulence using C. elegans model indicates it’s another facet of functions. However, studies pertaining to identify the cascade of genes involved in pathogenesis of A. baumannii would require comprehensive analysis.

With respect to its substrate specificity, we found that inactivation of abeD decreased resistance to ceftriaxone, gentamicin, rifampicin, and tobramycin in A. baumannii AYE strain. The AcrD type efflux transporter present in the genome of Erwinia amylovora Ea1189 was characterized and results showed it had a crucial role in conferring resistance to clotrimazole and luteolin [29]. A published report demonstrated that AcrD of E. coli confers wide resistance profile such as aminoglycosides, bile acids, novobiocin and fusidic acid [26]. The AbeD displayed selective specificity towards benzalkonium chloride, which validates its role in disinfectant tolerance in A. baumannii for the first time. In conjunction, the expression of mexCD-oprJ was found to be elevated in P. aeruginosa cells when treated with hospital based biocide such as CHX and benzalkonium chloride [30]. It would be worthy to state here that inactivation of AbeD homolog in soil dwelling bacteria A. baylyi, rendered cells sensitive to ofloxacin, nalidixic acid, rifampicin, meropenem and gentamicin, besides demonstrating its role in oxidative stress tolerance (In preparation).

SoxR is a member of the MerR family of transcriptional activators which dimerizes in liquid form, and the 17-kDa contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster. The superoxide radicals are sensed by SoxR using the CXXC-coordinated [2Fe-2S]-cluster which ultimately leads to transcriptional activation of hierarchical signaling cascade [31, 32]. Studies have reported that upon sensing the environmental assail, the MerR regulator disorders the conformation of the targeted promoter such that transcription can be initiated upon binding of RNA polymerase [33, 34, 35]. Recently we showed that the MerR-type transcriptional regulator SoxR has a role in regulating the expression of abuO in A. baumannii [17]. Interestingly, binding assays and expression analysis provided first evidence for the possible involvement of SoxR in also regulating expression of abeD in A. baumannii. Remarkably, the expression of abuO was increased in abeD mutant indicating that A. baumannii exploits alternative resistance determinants to combat the antibiotic stress.

The results discussed in this report mark just the beginning, the impact of ΔsoxR on antimicrobial susceptibility and how it regulates efflux pumps is an unexplored area in the field, and studies pertaining to this are our current focus of research.

Conclusions

The novel resistance determinant AbeD participates along with other mechanisms in mediating tolerance to stress physiology and antimicrobial resistance in A. baumannii.

Supporting Information

The efflux pump abeD transformed in KAM32 was subjected to antibiotic susceptibilities (A), oxidative disc assay (B) and fluorimetric efflux assay using efflux pump substrate EtBr with control (C) and abeD expressing cells (D).

(TIF)

Southern blot hybridization of digested A. baumannii chromosomal DNA with the abeD probe. W represents WT, M represents abeD mutant and the genomic DNA was digested with BglII, HindIII, KpnI, PstI, XbaI and XhoI respectively. The autorad shows the presence of abeD in WT and the shift in size of the band in M indicates disruption of abeD in mutant.

(TIF)

A, The mean diameter of halos obtained from independent experiments is plotted with standard deviations. P value for the differences between WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD strains were <0.01. B, The ability of A. baumannii ΔabeD and WT cells in forming biofilm on glass tubes. The data are the means of measurements performed three times.

(TIF)

Survival assays using EtBr (A), acriflavine (B), safranin (C) are shown in bar graphs. Growth inactivation assay was performed using WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD cells by adding gentamicin either in absence or presence of PAβN at either 25mg/L (D) or 50mg/L (E) respectively.

(TIF)

Biocide tolerance was tested by performing survival assays using WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD in presence of different concentrations of benzalkonium chloride [A], chlorhexidine [B] and triclosan [C].

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors remain obliged to our Director Dr. Girish Sahni, CSIR-Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, for giving excellent atmosphere for executing the study. VBS, MV, AM remains thankful to DBT and CSIR for their fellowships.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Funding from CSIR (BSC0210H, OLP0061) and DBT (BT/PR14304/BRB/10/822/2010, BT/HRD/NBA/34/01/2012) is highly acknowledged, however they had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Howard A, O'Donoghue M, Feeney A, Sleator RD. 2012. Acinetobacter baumannii: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Virulence 2012. May 1;3(3):243–50. 10.4161/viru.19700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durante-Mangoni E, Zarrilli R. Global spread of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: molecular epidemiology and management of antimicrobial resistance. Future Microbiol. 2011. April;6(4):407–22. 10.2217/fmb.11.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007.An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii . Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007. December;5(12):939–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rynga D, Shariff M, Deb M. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from Delhi, India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015. September 4;14(1):40 10.1186/s12941-015-0101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nachimuthu R, Subramani R, Maray S, Gothandam KM, Sivamangala K, Manohar P, et al. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from Tamil Nadu. J Chemother. 2015. July 22:1973947815Y0000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoon EJ, Nait Chabane Y, Goussard S, Snesrud E, Courvalin P, De E, et al. Contribution of Resistance-Nodulation-Cell Division Efflux Systems to Antibiotic Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Acinetobacter baumannii. MBio. 2015. March 24;6(2). pii: e00309–15. 10.1128/mBio.00309-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coyne S, Courvalin P, Périchon B. Efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011. March;55(3):947–53. 10.1128/AAC.01388-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piddock LJ. Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006. April;19(2):382–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piddock LJ. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps—not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006. August;4(8):629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poole K. Efflux pumps as antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Ann Med. 2007;39(3):162–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T. Resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pump involved in aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strain BM4454. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001. December;45(12):3375–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marchand I, Damier-Piolle L, Courvalin P, Lambert T. Expression of the RND-type efflux pump AdeABC in Acinetobacter baumannii is regulated by the AdeRS two-component system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004. September;48(9):3298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Damier-Piolle L, Magnet S, Brémont S, Lambert T, Courvalin P. AdeIJK, a resistance-nodulation-cell division pump effluxing multiple antibiotics in Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008. February;52(2):557–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenfeld N, Bouchier C, Courvalin P, Périchon B. Expression of the resistance-nodulation-cell division pump AdeIJK in Acinetobacter baumannii is regulated by AdeN, a TetR-type regulator. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012. May;56(5):2504–10. 10.1128/AAC.06422-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coyne S, Rosenfeld N, Lambert T, Courvalin P, Périchon B. Overexpression of resistance-nodulation-cell division pump AdeFGH confers multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010. October;54(10):4389–93. 10.1128/AAC.00155-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fournier PE, Vallenet D, Barbe V, Audic S, Ogata H, Poirel L, et al. Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii . PLoS Genet. 2006. January;2(1):e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Srinivasan VB, Vaidyanathan V, Rajamohan G. AbuO, a TolC-like outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii, is involved in antimicrobial and oxidative stress resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015. February;59(2):1236–45. 10.1128/AAC.03626-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Srinivasan VB, Rajamohan G, Gebreyes WA. Role of AbeS, a novel efflux pump of the SMR family of transporters, in resistance to antimicrobial agents in Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009. December;53(12):5312–6. 10.1128/AAC.00748-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajamohan G, Srinivasan VB, Gebreyes WA. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel efflux pump, AmvA, mediating antimicrobial and disinfectant resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010. September;65(9):1919–25. 10.1093/jac/dkq195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Srinivasan VB, Rajamohan G. KpnEF, a new member of the Klebsiella pneumoniae cell envelope stress response regulon, is an SMR-type efflux pump involved in broad-spectrum antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013. September;57(9):4449–62. 10.1128/AAC.02284-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hennequin C, Forestier C. oxyR, a LysR-type regulator involved in Klebsiella pneumoniae mucosal and abiotic colonization. Infect Immun. 2009. December;77(12):5449–57. 10.1128/IAI.00837-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coudeyras S, Nakusi L, Charbonnel N, Forestier C. A tripartite efflux pump involved in gastrointestinal colonization by Klebsiella pneumoniae confers a tolerance response to inorganic acid. Infect Immun. 2008. October;76(10):4633–41. 10.1128/IAI.00356-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stevanin TM, Ioannidis N, Mills CE. Flavohemoglobin Hmp affords inducible protection for Escherichia coli respiration, catalyzed by cytochromes bo' or bd, from nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2000. November 17;275(46):35868–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001. December;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, Mekalanos JJ, Ornston LN, Gerstein M, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007. March 1;21(5):601–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenberg EY, Ma D, Nikaido H. AcrD of Escherichia coli is an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J Bacteriol. 2000. March;182(6):1754–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hood MI, Jacobs AC, Sayood K, Dunman PM, Skaar EP. Acinetobacter baumannii increases tolerance to antibiotics in response to monovalent cations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010. March;54(3):1029–41. 10.1128/AAC.00963-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trainor EA, Horton KE, Savage PB, Testerman TL, McGee DJ. Role of the HefC efflux pump in Helicobacter pylori cholesterol-dependent resistance to ceragenins and bile salts. Infect Immun. 2011. January;79(1):88–97. 10.1128/IAI.00974-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pletzer D, Weingart H. Characterization of AcrD, a resistance-nodulation-cell division-type multidrug efflux pump from the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora . BMC Microbiol. 2014. January 21;14:13 10.1186/1471-2180-14-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fraud S, Campigotto AJ, Chen Z, Poole K. MexCD-OprJ multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement in chlorhexidine resistance and induction by membrane-damaging agents dependent upon the AlgU stress response sigma factor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008. December;52(12):4478–82. 10.1128/AAC.01072-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hidalgo E, Ding H, Demple B. Redox signal transduction: mutations shifting [2Fe-2S] centers of the SoxR sensor-regulator to the oxidized form. Cell. 1997. January 10;88(1):121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Storz G, Imlay JA. Oxidative stress. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999. April;2(2):188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hobman JL, Wilkie J, Brown NL. A design for life: prokaryotic metal-binding MerR family regulators. Biometals. 2005. August;18(4):429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003. June;27(2–3):145–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McEwan AG, Djoko KY, Chen NH, Couñago RL, Kidd SP, Potter AJ, et al. Novel bacterial MerR-like regulators their role in the response to carbonyl and nitrosative stress. Adv Microb Physiol. 2011;58:1–22. 10.1016/B978-0-12-381043-4.00001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The efflux pump abeD transformed in KAM32 was subjected to antibiotic susceptibilities (A), oxidative disc assay (B) and fluorimetric efflux assay using efflux pump substrate EtBr with control (C) and abeD expressing cells (D).

(TIF)

Southern blot hybridization of digested A. baumannii chromosomal DNA with the abeD probe. W represents WT, M represents abeD mutant and the genomic DNA was digested with BglII, HindIII, KpnI, PstI, XbaI and XhoI respectively. The autorad shows the presence of abeD in WT and the shift in size of the band in M indicates disruption of abeD in mutant.

(TIF)

A, The mean diameter of halos obtained from independent experiments is plotted with standard deviations. P value for the differences between WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD strains were <0.01. B, The ability of A. baumannii ΔabeD and WT cells in forming biofilm on glass tubes. The data are the means of measurements performed three times.

(TIF)

Survival assays using EtBr (A), acriflavine (B), safranin (C) are shown in bar graphs. Growth inactivation assay was performed using WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD cells by adding gentamicin either in absence or presence of PAβN at either 25mg/L (D) or 50mg/L (E) respectively.

(TIF)

Biocide tolerance was tested by performing survival assays using WT, ΔabeD and ΔabeDΩabeD in presence of different concentrations of benzalkonium chloride [A], chlorhexidine [B] and triclosan [C].

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.