Abstract

The primary cells that participate in islet transplantation are the endocrine cells. However, in the islet microenvironment, the endocrine cells are closely associated with the neurovascular tissues consisting of the Schwann cells and pericytes, which form sheaths/barriers at the islet exterior and interior borders. The two cell types have shown their plasticity in islet injury, but their roles in transplantation remain unclear. In this research, we applied 3-dimensional neurovascular histology with cell tracing to reveal the participation of Schwann cells and pericytes in mouse islet transplantation. Longitudinal studies of the grafts under the kidney capsule identify that the donor Schwann cells and pericytes re-associate with the engrafted islets at the peri-graft and perivascular domains, respectively, indicating their adaptability in transplantation. Based on the morphological proximity and cellular reactivity, we propose that the new islet microenvironment should include the peri-graft Schwann cell sheath and perivascular pericytes as an integral part of the new tissue.

Abbreviations: 2-D, 2-dimensional; 3-D, 3-dimensional; GFP, green fluorescence protein; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; NG2, neuron-glial antigen 2

Keywords: 3-D histology, Islet transplantation, Schwann cells, Pericytes, Revascularization, Reinnervation

Highlights

-

•

3-D neurovascular histology with cell tracing is used to study islet transplantation.

-

•

Donor islet Schwann cells and pericytes participate in graft neurovascular regeneration.

-

•

Islet graft microenvironment includes Schwann cell sheath and perivascular pericytes.

1. Introduction

The goal of islet transplantation is to use the donor β-cells to restore the insulin production and glycemic regulation in patients with type 1 diabetes to avoid serious complications (Barton et al., 2012, Goland and Egli, 2014). For long-term graft survival, neurovascular regeneration in the new islet microenvironment is essential for the engraftment process (Jansson and Carlsson, 2002, Persson-Sjogren et al., 2000, Reimer et al., 2003). The graft–host integration through the neurovascular networks is important for grafts to receive nutrients and stimulations from the circulation and nerves to maintain survival and respond to physiological cues. Thus, identification of the mechanisms and cellular players that participate in islet neurovascular regeneration holds the key to improving the outcome of transplantation.

In the pancreas, the endocrine islets receive rich neurovascular supplies, which consist of not only the nerves (sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory nerves; Ahren, 2012, Borden et al., 2013, Tang et al., 2014) and blood vessels, but also the Schwann cells (the glial cells of the peripheral nervous system) and pericytes residing at the exterior and interior boundaries of the islet, facing the exocrine pancreas and endothelium, respectively (Donev, 1984, Hayden et al., 2008, Richards et al., 2010, Sunami et al., 2001). Morphologically, the islet Schwann cell network resides in the islet mantle, forming a mesh-like sheath (with apparent openings) surrounding the islet. The Schwann cells also release neurotrophic factors such as the nerve growth factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) to the islet microenvironment to support the “neuroendocrine” tissue (Mwangi et al., 2008, Teitelman et al., 1998).

The pericytes, also known as the mural cells, reside on the abluminal side of the blood vessels, guarding the vascular network. The pericyte and endothelium interactions are important for the angiogenesis and survival of endothelial cells (Armulik et al., 2005, Lindahl et al., 1997, von Tell et al., 2006). Particularly in angiogenesis, the release of platelet-derived growth factor from the endothelial cells recruits pericytes to establish their physical contact for paracrine signaling to stabilize the vascular system.

While sheathing the islets and blood vessels, in the pancreas the Schwann cells and pericytes also react to the islet injury and lesion formation in experimental diabetes (Tang et al., 2013, Teitelman et al., 1998, Yantha et al., 2010). For example, in the rodent model of islet injury induced by the streptozotocin injection, both Schwann cells and pericytes become reactive in response to the islet microstructural and vascular damages (Tang et al., 2013, Teitelman et al., 1998). In the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model, the islet lesion induced by lymphocytic infiltration leads to peri-lesional and perivascular Schwann cell activation occurring at the front of lymphocytic infiltration in insulitis (Tang et al., 2013). Regarding the pericytes, their cellular responses were also found in the islet injuries induced by streptozotocin injection and lymphocytic infiltration with global (streptozotocin injection) and localized (NOD mice) changes of pericyte density (Tang et al., 2013). Importantly, the plasticity of Schwann cells and pericytes in response to islet injury suggests their potential reactivity in islet transplantation, in which the injuries occur both to the donor islets and at the transplantation site of the recipient.

To elucidate the ability of Schwann cells and pericytes in the participation of islet graft neurovascular regeneration, in this research we transplanted the mouse islets under the kidney capsule and prepared transparent graft specimens by tissue clearing (or optical clearing, use of an immersion solution of high refractive index to reduce scattering in optical microscopy; Chiu et al., 2012, Fu et al., 2009, Fu and Tang, 2010, Liu et al., 2015) to characterize the 3-dimensional (3-D) features of the Schwann cell and vascular networks, which otherwise cannot be easily portrayed by the standard microtome-based histology. We also transplanted the labeled islets with the nestin (the marker of neurovascular stem/progenitor cells; Dore-Duffy et al., 2006, Mignone et al., 2004, Treutelaar et al., 2003) promoter-driven green fluorescence protein (GFP) expression in the Schwann cells and pericytes (Alliot et al., 1999, Clarke et al., 1994, Frisen et al., 1995) to trace their locations and activities in the recipient.

Taking advantage of the 3-D features of the islet graft neurovascular network, in this research we demonstrate: (i) the regeneration of the islet Schwann cell sheath and the perivascular pericyte population after islet transplantation under the kidney capsule and (ii) the contribution of the donor islet Schwann cells and pericytes to the regeneration process. In this article, we present the morphological and quantitative data of the islet graft Schwann cell network and pericytes and discuss the implications of their participation in the islet graft neurovascular regeneration.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Animals and Islet Transplantation

Male inbred C57BL/6 (B6) mice, age 8–12 weeks, were used as the donors and recipients for islet transplantation. The nestin-GFP transgenic donor mice used in this research have been developed previously (Mignone et al., 2004). In these animals, the GFP expression is under the control of the 5.8-kb promoter and the 1.8-kb second intron of the nestin gene, which encodes a type VI intermediate filament protein. The nestin-GFP+ mice and their nestin-GFP− littermates, age 8–12 weeks, were used as the donors and recipients, respectively, to avoid rejection. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital approved all procedures with these mice.

All recipient mice used in this research were diabetic prior to islet transplantation. The diabetic B6 and nestin-GFP− mice were induced by a single intra-peritoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, 200 mg/kg body weight). Before transplantation, diabetic recipients were confirmed by hyperglycemia, weight loss, and polyuria; only the mice with blood glucose levels higher than 350 mg/dl two weeks after the STZ injection were transplanted. Blood glucose concentration was measured from the tail tip with a portable glucose analyzer (One Touch II, LifeScan Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA).

Islet isolation was performed under sodium amobarbital-induced anesthesia with the donor pancreases distended with 2.5 ml of digestion solution (ductal injection of RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1.5 mg/ml of collagenase; RPMI: Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; collagenase: Sigma, from Clostridium histolyticum, type XI), excised, and incubated in a water bath at 37 °C. Afterward, the islets were purified by a density gradient (Histopaque-1077, Sigma) and then handpicked under a stereo microscope. Islets with a diameter between 75 and 250 μm were collected for transplantation. Three hundred islets were syngeneically transplanted under the left kidney capsule on the same day of isolation. Mice with reversal of diabetes to normoglycemia two weeks post-transplantation were defined as mice with engrafted islets and included in the study (Juang et al., 2014).

2.2. Tissue Labeling

Blood vessels of the kidney and islet graft were labeled by vessel painting (Fu et al., 2010, Juang et al., 2014) via cardiac perfusion of the lectin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (30 μg/g of body weight, Invitrogen, Cat No. W11261) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde perfusion fixation. Afterward, grafts under the kidney capsule were harvested and the vibratome sections of the tissue (~ 400 μm) were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 1 h at 25 °C. The fixed tissues were then immersed in 2% Triton X-100 solution for 2 h at 25 °C for permeabilization.

Three different primary antibodies were used to immunolabel the tissues following the protocol outlined below. The antibodies used were polyclonal rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Schwann cell marker) antibody (DAKO, Z0334; Carpinteria, CA, USA), a rabbit anti-neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2, pericyte marker) antibody (AB5320; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and polyclonal guinea pig anti-insulin (Gene Tex, Irvine, CA, USA) antibody. Before applying the antibody, the tissue was rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This was followed by a blocking step, incubating the tissue with the blocking buffer (2% Triton X-100, 10% normal goat serum, and 0.02% sodium azide in PBS). The primary antibody was then diluted in the dilution buffer (1:50, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1% normal goat serum, and 0.02% sodium azide in PBS) to replace the blocking buffer and incubated for one day at 15 °C.

Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody and Alexa Fluor 546 conjugated goat anti-guinea pig secondary antibody (1:200, Invitrogen) were used to reveal the immunostained structures. Nuclear staining by propidium iodide (50 μg/ml, Invitrogen) was performed at room temperature for 1 h to reveal the nuclei, if necessary. The labeled specimens were then immersed in the optical-clearing solution (FocusClear™ solution, CelExplorer, Hsinchu, Taiwan or RapiClear 1.52 solution, SunJin Lab, Hsinchu, Taiwan) before being imaged via confocal microscopy.

2.3. Confocal Microscopy

Imaging of the tissue structure was performed with a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with an objective of 25 × LD ‘Plan-Apochromat’ glycerine immersion lenses (working distance: 570 μm) (optical section: 5 μm; Z-axis increment: 2.5 μm) and an objective of 40 × LD ‘C-Apochromat’ water immersion lenses (working distance: 620 μm) (optical section: 3 μm; Z-axis increment: 1.5 μm) under a regular or tile-scan mode with automatic image stitching. The laser-scanning process was operated under the multi-track scanning mode to sequentially acquire signals, including the transmitted light signals. The Alexa Fluor 647-labeled structures were excited at 633 nm and the fluorescence was collected by the 650- to 710-nm band-pass filter. The propidium iodide-labeled nuclei and the Alexa Fluor 546-labeled structures were excited at 543 nm and the signals were collected by the 560- to 615-nm band-pass filter. The lectin-Alexa Fluor 488-labeled blood vessels were excited at 488 nm and the fluorescence was collected by the 500- to 550-nm band-pass filter.

2.4. Image Projection and Analysis

The LSM 510 software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and the Avizo 6.2 image reconstruction software (VSG, Burlington, MA, USA) were used for projection, signal segmentation, and analysis of the confocal images. In the supplemental videos, image stacks were recorded using the “Movie Maker” function of Avizo with the increase in display time in association with the depth of the optical section. In Supplemental Video S3, the “Camera Rotation” function of Avizo was used to adjust the projection angles of the 3-D images.

In the neurovascular density analysis, both the 3-week and 6-week grafts were acquired from four recipients. Four or five image stacks were taken from each animal to assess their graft blood vessel, pericyte, and Schwann cell network densities. The blood vessel, pericyte, and Schwann cell network densities of the pancreatic islets from three normal B6 mice were used as the control.

Quantitation of the graft neurovascular tissue density was illustrated in Juang et al. (2014). The same tissue labeling, imaging, and quantitation processes were conducted on the transplanted islets under the kidney capsule and pancreatic islets in situ to compare the tissue densities on the same basis. In estimation of the density, feature extraction and image segmentation were first performed by the “Label Field” function of Avizo to collect the voxels of the grafts and those of the blood vessels (signals from vessel painting) or Schwann cell network (GFAP signals). Afterward, voxels of the blood vessels (or Schwann cell network) in the acquired image stack were divided by those of the grafts × 100% to estimate the blood vessel density (or Schwann cell network density). Quantification of pericytes was performed by counting the pericytes in the segmented volume of interest to estimate the cell densities (number of pericytes per 106 μm3 of graft). While counting the pericytes, both the NG2 and nuclear signals were used to define a pericyte —an NG2 immunoreactive cell body with at least two processes contacting the blood vessels (Tang et al., 2013). Signal or pericyte densities derived from different image stacks of the same animal were first normalized and then averaged over the other animals in the same group.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The quantitative values are presented as means ± standard deviation. Statistical differences were determined by the unpaired Student's t test. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Labeling and 3-D Imaging of Islet Schwann Cells and Pericytes In Situ

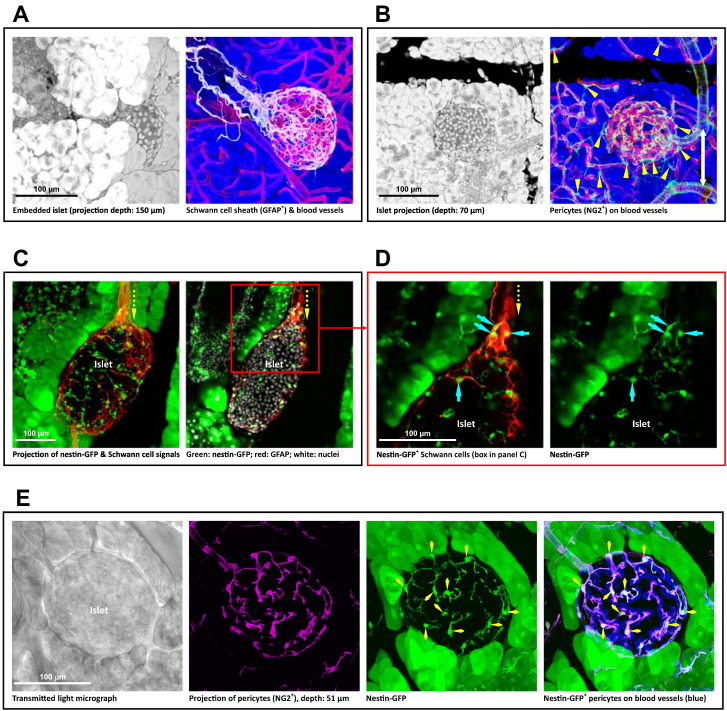

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2) are the two classic markers for immunohistochemical identification of the Schwann cells and pericytes, respectively (Bergers and Song, 2005, Tang et al., 2013, Winer et al., 2003). Fig. 1A and B shows the in-depth imaging and projection of the islet GFAP+ Schwann cell sheath and the perivascular NG2+ pericytes in situ. The images were derived from 3-D islet neurovascular histology with tissue clearing (Tang et al., 2014). Technically, due to the dispersed nature of the neurovascular networks, the standard microtome-based 2-D tissue analysis is limited in presenting the network structure. 3-D imaging and identification of the two cell types are essential to illustrate their morphologies in space.

Fig. 1.

Labeling and 3-D imaging of islet Schwann cells and pericytes in situ. (A) Islet Schwann cell sheath. The field of interest (left panel, an islet embedded in the exocrine tissue) and the islet Schwann cell network (right panel; white: Schwann cell marker GFAP; red: blood vessels; blue: counterstain of exocrine acini) are presented in projection. Note: in-depth recording of the islet is presented in the last third of Supplemental Video S3. (B) Pancreatic islet pericytes. The NG2+ pericytes (green) reside on the abluminal domain of blood vessels with a higher density associated with the islet than acini. Arrow head: pericyte cell body. White arrow: pericyte encircling the arteriole. (C and D) Nestin-GFP expression in the islet Schwann cell population. Panel C shows the projection (depth: 40 μm) and 2-D image (optical section: 5 μm) of an islet in the nestin-GFP transgenic mice with prominent GFP expression in the exocrine acini (Delacour et al., 2004), but not in the endocrine cells (Treutelaar et al., 2003). The yellow arrow indicates the Schwann cell plexus (red) entering the islet from the neuro-insular complex at the pole. The box in panel C is enlarged in panel D to identify the nestin-GFP expression in the Schwann cells (overlap of green and red). Cyan arrows indicate the Schwann cell bodies carrying the nestin-GFP expression. (E) Nestin-GFP expression in the islet pericyte population. The transmitted light image shows the islet boundary. Magenta: NG2 staining of pericytes. Green: nestin-GFP expression. Blue: blood vessels. The overlap of NG2 (magenta) and GFP (green) highlights the nestin-GFP expression in the perivascular pericytes (white). Arrows indicate the pericyte cell bodies.

3.2. Nestin-GFP Labeling of Islet Schwann Cells and Pericytes

Nestin is an intermediate filament protein identified as a stem/progenitor cell marker to indicate the glial cell and pericyte plasticity in the brain (Dore-Duffy et al., 2006, Mignone et al., 2004). In the pancreas, we applied the nestin-GFP expression (i.e., GFP expression driven by the nestin promoter) in the Schwann cells and pericytes to indicate their reactivity and trace the donor Schwann cells and pericytes in the process of islet transplantation.

Fig. 1C and D shows the gross view and zoom-in examination of the overlap of the nestin-GFP signals and the GFAP+ Schwann cell network of islet in situ. The overlap of the nestin-GFP signals and the NG2+ perivascular pericytes is presented in Fig. 1E. The results indicate that both the islet Schwann cells and pericytes are similar to their counterparts in the central nervous system in the nestin promoter activity. This expression pattern allowed us to use the nestin-GFP+ donor islets to trace the Schwann cells and pericytes in islet transplantation.

Note that in comparison with the Schwann cells and pericytes, the islet endocrine cells are (i) negative in the nestin-GFP expression (Treutelaar et al., 2003) and (ii) without the cellular processes extending from the cell body. In this research, we use both features, in addition to immunohistochemistry (GFAP or NG2 staining), to distinguish the Schwann cells and pericytes from the endocrine cells. Regarding the exocrine acinar cells in the pancreas, these cells are positive in nestin-GFP expression (as revealed in Fig. 1C–E and Delacour et al., 2004). However, they were separated from the isolated islets before transplantation. Thus, the acinar cells do not influence the Schwann cell and pericyte tracing in islet transplantation.

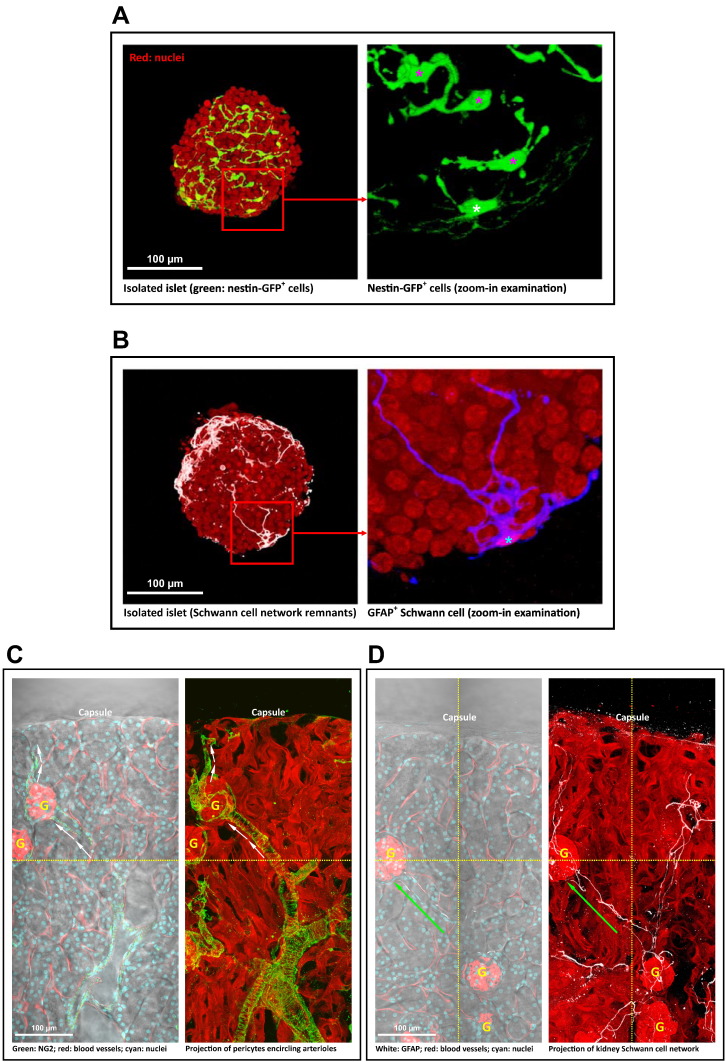

3.3. Schwann Cells and Pericytes in Islet and Kidney Before Transplantation

Fig. 2A shows a typical isolated islet before transplantation. From the nestin-GFP signals, we observed that the Schwann cells and pericytes remained associated with the islet with distinct cell bodies and processes in the mantle (Schwann cells) and core (pericytes). In addition to the nestin-GFP signals, we also used the GFAP immunostaining to confirm the presence of Schwann cells in the islet mantle (Fig. 1B). Because the pericyte surface marker NG2, a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, was disturbed by collagenase digestion in the process of harvesting islets from the pancreas, NG2 immunohistochemistry cannot be used to confirm the islet pericytes at this stage.

Fig. 2.

Pericytes and Schwann cells in isolated islets and renal microenvironment before transplantation. (A) Pericyte population in isolated islet. Left: gross view. Right: zoom-in examination of the nestin-GFP signals (box in the left). The in-depth projection of the nestin-GFP+ cells shows the intra-islet pericytes (magenta asterisk) and the peri-islet Schwann cell (yellow asterisk). (B) Peri-islet Schwann cell in isolated islet. GFAP staining identifies the Schwann cell (asterisk) with processes extending from the cell body. Red: nuclei. White (left, gross view)/blue (right, zoom-in examination): GFAP. (C) NG2 staining of renal pericytes. Left: overlay of transmitted light and fluorescence image. Right: projection of fluorescence signals (depth: 81 μm). The projection shows that the processes of pericytes encircle the afferent and efferent arteriole (arrows) and follow the blood vessel into the glomerulus (letter ‘G’). (D) GFAP staining of renal Schwann cell network. The 2-D image and 3-D projection (depth: 99 μm) show that the Schwann cell fibers follow the arteriole in elongation (arrow) and associate with the glomeruli. Images were stitched (dotted lines) to create a wider view of the renal microenvironment. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Regarding the kidney pericytes and Schwann cell network, Fig. 2C and D shows the gross views of the kidney microstructures and their association with the two cell types. Specifically, both the kidney pericytes and Schwann cell network follow the arterioles in extension and associate with the glomeruli. The kidney pericytes also encircle the renal arteriole (Fig. 2C), which is similar to the pancreatic pericytes that encircle the pancreatic arteriole (Fig. 1B).

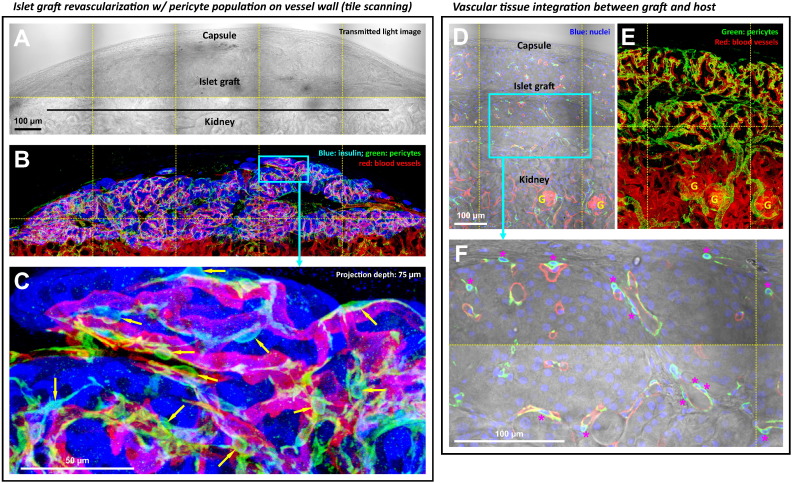

3.4. Islet Graft Revascularization and the Perivascular Pericytes

Six weeks after islet transplantation under the kidney capsule, we prepared transparent graft specimens (Fig. 3A) and applied 3-D histology to examine the graft microstructure and revascularization. Fig. 3B and C shows the gross view and zoom-in examination of the graft with fluorescence signals derived from the β-cells (insulin staining), blood vessels, and pericytes. In-depth projection of the vasculature reveals the perivascular pericytes with prominent cell bodies and processes residing on the walls of microvessels, resembling the pericyte morphology in the pancreatic islet in situ (Fig. 1B). The in-depth recording of the graft pericytes is presented in Supplemental Video S1.

Fig. 3.

Regeneration of the graft perivascular pericyte population six weeks after islet transplantation. (A and B) Gross view of islet graft under the kidney capsule. Panels A and B were taken under the same view to show the perivascular pericytes (NG2+, green). (C) Zoom-in examination of perivascular pericytes in the islet graft domain (box in B). Arrows indicate the pericyte cell bodies. (D and E) Gross view of the graft-kidney vascular integration. Panel D: overlay of the transmitted light and fluorescence image. Panel E: projection of fluorescence signals. Panels D and E were taken under the same view. The gross view shows the vascular connections between the islet graft and the kidney parenchyma. (F) Zoom-in examination of the perivascular pericytes. Asterisk indicates the pericyte cell body with the nucleus (blue) enclosed by the NG2 signals (green). Red: blood vessels.

In addition, we used tile scanning to acquire a gross view of the vascular connections between the islet graft and the kidney parenchyma to demonstrate the graft–host integration (Fig. 3D and E). The gross view also reveals a higher NG2 staining density associated with the islet graft than that of the kidney (Fig. 3E), showing the intrinsic difference between the islet and renal tissues in vascular compositions and arrangements.

Finally, from the histological point of view, the preparation of transparent graft specimens by tissue clearing allowed us to simultaneously acquire the transmitted light and fluorescence signals with high definition to confirm and illustrate the graft and renal structures in space (Fig. 3A/B and D/E). The high-definition images also allowed us to identity and count the cell bodies of pericytes by overlaying the NG2 and nuclear signals of the graft (Fig. 3F). This approach is used in Fig. 7B to quantify and compare the pericyte densities of the islet graft and that of the pancreatic islet in situ.

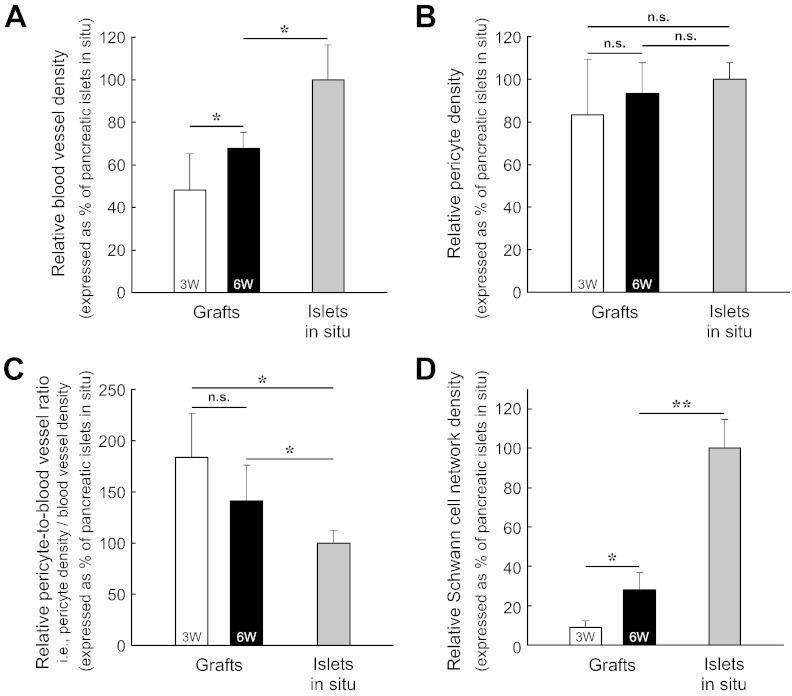

Fig. 7.

Quantitation of islet graft revascularization and Schwann cell network regeneration. (A) Increase in blood vessel density of islet grafts after transplantation. 3W: 3-week grafts. 6W: 6-week grafts. The difference in the blood vessel density (blood vessel volume/tissue volume) was statistically significant between the 3-week and 6-week grafts (*p < 0.05) and between the 6-week grafts and the islets in situ (*p < 0.05). (B) Maintenance of pericyte population in the islet graft. The pericyte density (number of NG2+ pericytes/tissue volume) of the 3-week and 6-week grafts was only marginally lower than that of the pancreatic islets in situ. The difference in pericyte density was not significant among the three tissue conditions. (C) Higher pericyte-to-blood vessel ratio of the islet grafts than that of the pancreatic islets in situ. The y-axis “pericyte-to-blood vessel ratio” of this figure was derived from the values of the y-axes of Fig. 7A and B: the pericyte density divided by the blood vessel density, which is equal to the number of pericytes per blood vessel volume. The two graft conditions were statistically different from the in-situ islets in the ratio (*p < 0.05). But, the ratio was not statistically different between the two graft conditions. (D) Graft Schwann cell network regeneration. The difference in the Schwann cell network density (GFAP staining signals/tissue volume) was statistically significant among the three tissue conditions (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). Data are presented as means ± SD.

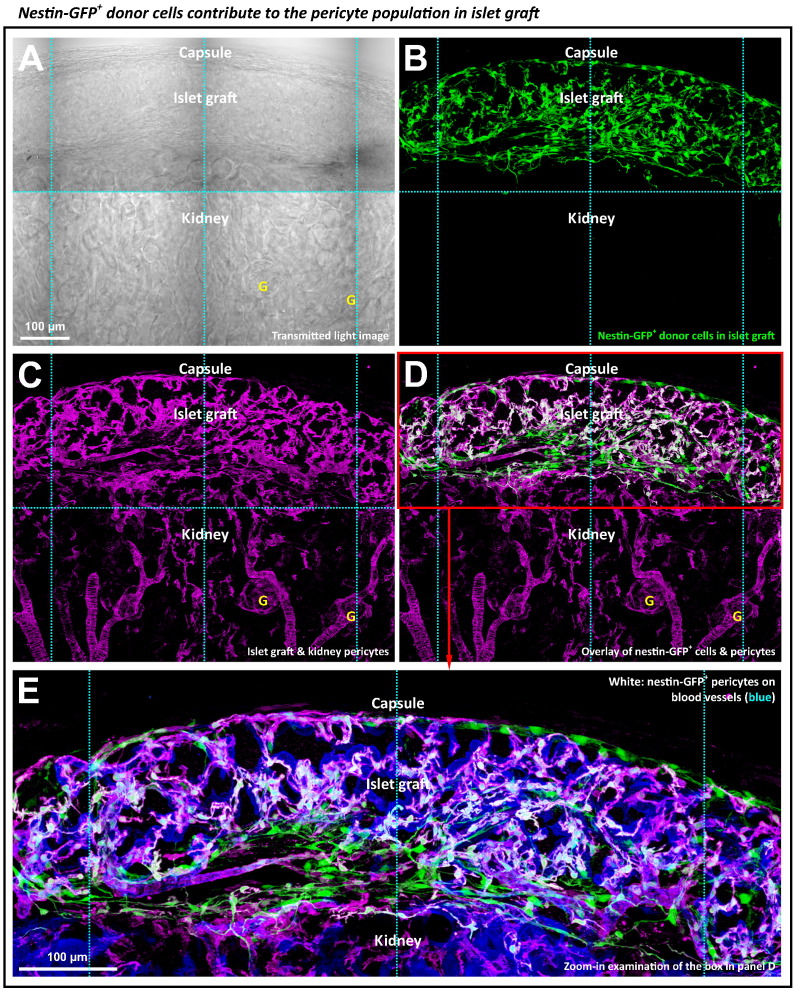

3.5. Donor Islet Pericytes Contribute to the Pericyte Population in the Islet Graft

Next, we transplanted the nestin-GFP-labeled donor islets to trace and examine the origin of the islet graft pericyte population (Fig. 4). Six weeks after the transplantation, we observed strong GFP expression in the islet graft (Fig. 4A and B), indicating that the nestin-GFP-labeled Schwann cells and pericytes were staying active in their new microenvironment. Importantly, the overlap of the nestin-GFP and NG2 signals (Fig. 4C and D and Supplemental Video S2) indicates that a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ cells was derived from the donor pericytes. The high-definition image presented in Fig. 4E highlights the prominent presence of the donor pericytes on the walls of the graft microvessels. Also, because we used the cardiac perfusion of the lectin-dye conjugates to label the mouse vasculature, we confirmed that the revealed graft microvessels, which consist of both the endothelium and pericytes, were functional. Supplemental Fig. S1 presents an additional example of the perivascular donor pericytes in a panoramic fashion.

Fig. 4.

Tracing the donor pericytes in islet graft. (A–D) Transmitted light and fluorescence images of the graft derived from the nestin-GFP+ donor islets. Panels A–D were taken under the same view. In panel D, overlay of the nestin-GFP (green, panel B) and NG2 (magenta, panel C) signals reveals a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells as the pericytes (white, overlap of green and magenta). The nestin-GFP+ donor pericytes reside in the graft domain, not in the kidney parenchyma. Letter ‘G’ indicates the glomerulus. Projection depth: 75 μm. (E) Zoom-in visualization of the nestin-GFP+ perivascular pericytes in panel D. Blue: blood vessels.

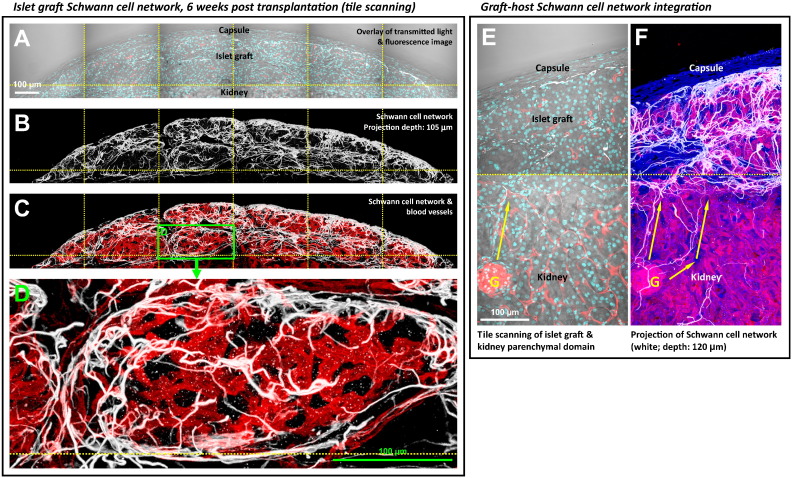

3.6. Regeneration of Islet Graft Schwann Cell Sheath

Similar to the reestablishment of the perivascular pericyte population, regeneration of the islet graft Schwann cell network also occurred in the process of islet engraftment under the kidney capsule. Six weeks after islet transplantation, Fig. 5A–D shows the gross view and zoom-in examination of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath. Specifically, the dense Schwann cell network regenerated at the peri-graft area, such as in the capsule-graft interface and at the boundaries of the aggregated islets. The morphology of the peri-graft Schwann cell sheath resembles that of the pancreatic islet Schwann cell sheath in situ (Fig. 1A). A 360° panoramic presentation of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath is illustrated in Supplemental Video S3.

Fig. 5.

Regeneration of graft Schwann cell sheath six weeks after islet transplantation. (A–C) Gross view of islet graft under the kidney capsule. Panels A–C were taken under the same view. Cyan: nuclei. White: GFAP+ Schwann cell network. Red: blood vessels. (D) Zoom-in examination of the peri-graft Schwann cell network (box in C). The image shows the graft Schwann cell sheath with high definition. (E and F) Integration of the graft-kidney Schwann cell network. Overlay of the transmitted light and fluorescence image (panel E) identifies the graft and kidney microstructures. Projection of the fluorescence signals (panel F) shows the graft-host neurovascular integration with apparent coupling of the Schwann cell networks as well as the microvessels between the graft and kidney. Arrows indicate the extension of the kidney Schwann cell fibers toward the graft domain.

Fig. 5E and F and Supplemental Fig. S2 show the tile-scanning images of the graft and the kidney parenchyma to illustrate the graft–host neurovascular integration. The coupling of the graft and the kidney Schwann cell networks and microvessels can be seen at the graft–host interfaces. The tile-scanning images also show that the density of the Schwann cell network in the graft domain is markedly higher than that of the kidney domain, which reflects the intrinsic difference between the islets and the renal microstructures, such as the glomeruli, in association with the neural tissues.

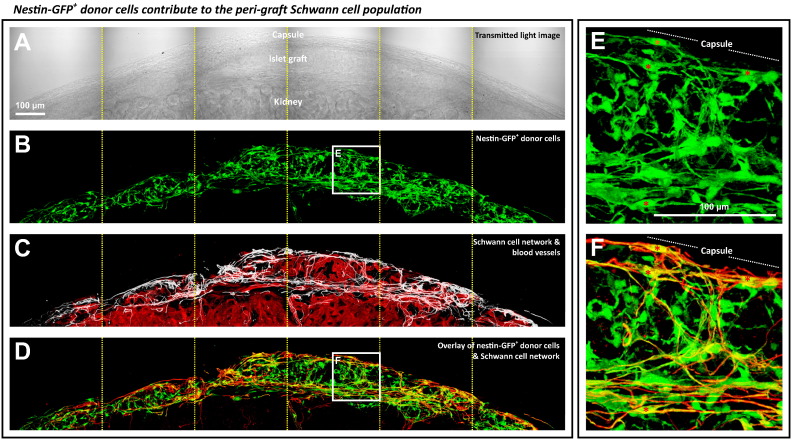

3.7. Donor Islet Schwann Cells Contribute to Regeneration of Peri-graft Schwann Cell Network

We next used the nestin-GFP+ islets in transplantation to identify the source of the islet graft Schwann cells. Fig. 6 shows the gross view and zoom-in examination of the overlap of the nestin-GFP and GFAP signals, confirming a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ cells as the GFAP+ Schwann cells. These cells primarily resided at the peri-graft domain with slender and prolonged processes extending from the cell bodies. Supplemental Video S4 shows the in-depth recording of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells contributing to the peri-graft Schwann cell sheath. Note that the apparent nestin promoter activity of the Schwann (glial) cells in islet transplantation (Fig. 6) was similar to that of the glial cells of the central nervous system in response to injury (Frisen et al., 1995).

Fig. 6.

Tracing the donor Schwann cells in islet graft. (A–D) Transmitted light and fluorescence images of the graft derived from transplantation of the nestin-GFP+ donor islets. Panels A–D were taken under the same view. In panel D, overlay of the nestin-GFP (green, panel B) and the Schwann cell marker GFAP (red, white in panel C) signals reveals a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ cells carrying the GFAP expression at the peri-graft area (yellow, overlap of green and red). Projection depth: 99 μm. (E and F) Zoom-in examination of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells with the Schwann cell marker GFAP expression (boxes in panels B and D). Asterisks indicate the nestin-GFP+ Schwann cells with processes extending from the cell body at the peri-graft area.

3.8. Quantitative Assessment of Graft Revascularization and Schwann Cell Network Regeneration

Using the 3-D image data, we next quantified the vascular and Schwann cell network densities of the 3-week and 6-week grafts and compared them with those of the pancreatic islets in situ to analyze the engraftment process.

Fig. 7A shows that in revascularization the blood vessel density (blood vessel volume/tissue volume) of the 3-week and 6-week grafts reached 48% and 68% of that of the pancreatic islets in situ, respectively. In comparison, the pericyte density (number of pericytes/tissue volume) of the 3-week and 6-week grafts was markedly higher at 83% and 93% of that of the pancreatic islets in situ, respectively, without significant difference among the three tissue conditions (Fig. 7B; Supplemental Fig. S3A shows the 3-week graft). Importantly, the results of the blood vessel and pericyte densities shown in Fig. 7A and B lead to a higher pericyte-to-blood vessel ratio (i.e., the pericyte density divided by the blood vessel density) of the 3-week and 6-week grafts, with increase of 84% and 41% over that of the pancreatic islets in situ, respectively (Fig. 7C). This higher pericyte-to-blood vessel ratio of the transplanted islets reveals a unique vascular feature in graft angiogenesis, which is similar to the increase in the pericyte density of the pancreatic islet after injury (Tang et al., 2013).

In comparison with the revascularization, the regeneration of the islet graft Schwann cell network was significantly delayed in the first three weeks after transplantation. The network density (GFAP staining signals/tissue volume) of the 3-week graft was only 9% of that of the pancreatic islets in situ (Fig. 7D; Supplemental Fig. S3B shows the 3-week graft). For the 6-week graft, the network density increased 2.1 fold from that of the 3-week graft and reached 28% of that of the pancreatic islets in situ. Interestingly, although the network density of the 6-week graft remained significantly lower than that of the islets in situ, the Schwann cell sheath was prominently seen at the graft boundaries (Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

4. Discussion

The plasticity of glial cells and pericytes has been shown in injuries occurring to the central nervous system and pancreatic islets in diseases with progressive lesion formation such as Alzheimer's disease and insulitis in experimental type 1 diabetes (Beach et al., 1989, Tang et al., 2013) and in acute conditions such as stroke, traumatic central nervous system injury, and islet injury induced by streptozotocin injection (Goritz et al., 2011, Pekny and Nilsson, 2005, Tang et al., 2013, Teitelman et al., 1998). In this research, we demonstrate the adaptability of islet Schwann (glial) cells and pericytes in response to islet transplantation, in which the Schwann cell network and the pericyte population reestablished at the graft exterior and interior boundaries, re-associating with the engrafted islets. We traced the donor Schwann cells and pericytes using the nestin-GFP+ transgenic islets to confirm their contribution to the regeneration. The 3-D graft microstructure, vasculature, and Schwann cell network were presented with high definition to facilitate qualitative and quantitative analyses of the tissue networks to characterize the graft neurovascular regeneration.

The classic view of the graft neurovascular regeneration is the in-growth of blood vessels and nerves from the host tissue to the transplanted islets (Jansson and Carlsson, 2002, Persson-Sjogren et al., 2000, Vajkoczy et al., 1995). Although Nyqvist et al. (2005) reported that the donor islet endothelial cells also participate in the formation of the graft microvessels after islet transplantation under the kidney capsule, the donor endothelial cells seems to cover only a limited area of the graft vasculature, indicating that the endothelial cells from the host kidney are the major contributor to the graft angiogenesis.

In this research, however, we show that the Schwann cells and pericytes derived from the donor islets were the major contributors to the Schwann cell sheath and the perivascular pericyte population of the grafts (Fig. 4, Fig. 6): both were abundantly associated with the engrafted islets, a sharp contrast to the intrinsic densities of the two cell types in the kidney (Fig. 2C and D and Supplemental Fig. S1, Supplemental Fig. S2). The prominent presence of Schwann cells and pericytes and their known functions of releasing the neurotrophic and angiogenic factors suggest the roles of the two cell types in attracting the nerves and blood vessels to facilitate graft neurovascular regeneration, despite prior research focusing mainly on the transplanted endocrine cells in the recruiting process (Brissova et al., 2006, Jansson and Carlsson, 2002, Myrsen et al., 1996, Persson-Sjogren et al., 2000, Vasir et al., 1998).

Although the survival of β-cells accounts for the success of islet transplantation, other cell types transplanted with the islets have also been described to correlate with the outcome of transplantation. For example, Street et al. (2004) reported a positive correlation between the long-term metabolic success of the islet recipients and the number of the ductal cells transplanted with the islets following the Edmonton Protocol. In this research, we used the mouse model to reveal the participation of the donor islet Schwann cells and pericytes in the process of transplantation. Although the roles of the human islet Schwann cells and pericytes in islet transplantation remain to be established, we suggest two of their potential impacts on the engraftment process: first, the neurovascular regeneration (as discussed earlier) and second, the host immunological response, due to the immunogenicity of the donor Schwann cells and pericytes (both of which are the antigen-presenting cells; Balabanov et al., 1999, Gulati, 1998, Lilje, 2002, Thomas, 1999) and their presence at the graft boundaries.

The technical advance of the islet graft 3-D histology with tissue clearing (Juang et al., 2014) has made possible the visualization of the graft Schwann cell network and pericyte population with high definition. Without tissue clearing, the kidney and pancreatic islets are intrinsically opaque because of the higher refractive index of the tissue constituents such as the phospholipids and proteins than that of the water molecules, leading to scattering when light enters the tissue matrix in optical microscopy. Tissue clearing substantially reduces light scattering by replacing the surrounding fluids with a solution of high refractive index, thereby matching the optical properties between the tissue constituents and the immersion solution to improve light transmission for different optical applications such as the optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging (Khan et al., 2004) and confocal and two-photon microscopy (Chung and Deisseroth, 2013, Erturk et al., 2012, Genina et al., 2010, Ke et al., 2013, Marx, 2014).

However, 3-D imaging with tissue clearing has the following limitations. First, because the clearing process changes the osmotic pressure of the environment, tissue fixation with chemicals such as paraformaldehyde is required to maintain the tissue volume. Because of the harsh condition, tissue clearing is not compatible with in vivo imaging such as the real-time blood flow microscopy and the functional calcium imaging to acquire the functional data from the grafts. Second, the 3-D imaging approach is not compatible with the super-resolution microscopy to examine the pericyte-endothelial and the Schwann cell-islet interfaces to characterize the potential cellular interactions. Electron microscopy of the cellular interfaces will be needed in the future to define the ultrastructures of the two cell types after transplantation.

Despite the limitations, preparation of transparent grafts allowed us to use deep-tissue microscopy to identify the slender processes of the Schwann cells and pericytes in space, which otherwise cannot be easily characterized with the standard 2-D histology. In addition, the transparent grafts allowed us to apply transmitted light microscopy to reveal the tissue architectures and boundaries and use them as the landmarks to confirm the signals derived from fluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy. This verification step is particularly important in characterization of the transplanted islets with novel details of anatomy, as illustrated in this research, to avoid uncertainties in depicting the islets in an ectopic environment.

In conclusion, using the mouse model of islet transplantation, we have identified the participation of the donor islet Schwann cells and pericytes in graft neurovascular regeneration. Before this research, the Schwann cells and pericytes were overlooked in islet transplantation due to the challenge of seeing their 3-D features after transplantation. Here, we applied the newly developed 3-D histology with tissue clearing to identify the formation of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath and perivascular pericyte population in neurovascular regeneration. Our work demonstrates the adaptability of the islet Schwann cells and pericytes in transplantation. This discovery will lay the foundation to study the roles of the two cell types in human islet transplantation and their influences on the function of islet endocrine cells in an ectopic environment.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

(Related to Fig. 4.)

Panoramic projection of nestin-GFP+ donor islet cells and their contribution to graft pericytes. The panoramic view of the islet graft was derived by stitching and projection of high-resolution confocal image stacks. Viewers can zoom in to specify the nestin-GFP+ donor cells (panels A and D) under the kidney capsule and the NG2+ pericytes (panels B and E) in both the islet graft and kidney parenchymal domain. In panels C and F, overlay of the two signals, green (nestin-GFP expression) and magenta (NG2+ pericytes), reveals a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells as the perivascular pericytes (white). They resided in the graft domain, but not in the kidney parenchymal domain. Letter ‘G’ indicates the glomerulus.

(Related to Fig. 5E and F.)

Panoramic projection of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath. This figure shows the gross view of the images presented in Fig. 5E and F. Viewers can zoom in to specify the peri-graft Schwann cell network. The gross view also shows a higher density of the GFAP+ Schwann cell fibers at the graft domain in comparison with that in the kidney parenchymal domain. The distribution indicates an intrinsic difference between the islets and the renal microstructures, such as the glomeruli, in association with the neural tissue.

(Related to Fig. 7.)

Pericyte population and Schwann cell network in 3-week grafts. (A) Pericyte population. Panel (i): merged display of the islet graft microstructure, vasculature, and pericyte population under the kidney capsule. Panel (ii): NG2 staining of the pericyte population. The images show the graft revascularization three weeks after transplantation with a prominent presence of the pericytes. (B) Schwann cell network. Panel (i): transmitted light image. Panel (ii): merged display of the Schwann cell network and blood vessels. Panel (iii): projection of the Schwann cell network. Panels (i)–(iii) were taken under the same view. The panoramic display shows that the development of the peri-graft Schwann cell network was still in progress three weeks after transplantation.

(Related to Fig. 3.)

3-D imaging of perivascular pericyte population in the optically cleared islet graft specimen. Two examples were recorded in the first two-thirds of the video (overlay of transmitted light and fluorescence signals). The last third of the video shows the pancreatic islet pericytes in situ, serving as the control and reference to the graft pericytes.

(Related to Fig. 4.)

Tracing the nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells and their contribution to the graft pericytes. The nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells (green) are presented in the upper panel. The lower panel shows the NG2 staining of perivascular pericytes (magenta). The nestin-GFP+ pericytes are identified in the graft domain (white, overlap of green and magenta), not in the kidney parenchyma. The result confirms the donor cells' contribution to the graft pericyte population. The two panels are presented in parallel to simultaneously show the same optical section of the graft.

(Related to Fig. 5.)

3-D imaging and 360° panoramic projection of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath. This video focuses on the middle area of Fig. 5A and B to present the islet graft Schwann cell sheath with high definition. The last third of the video shows the pancreatic islet Schwann cell sheath in situ, serving as the control and reference to the graft Schwann cell sheath.

(Related to Fig. 6.)

Contribution of nestin-GFP+ donor cells to the peri-graft Schwann cell sheath. The upper panel shows an in-depth recording of the overlap of the nestin-GFP (green) and GFAP (red) signals. The result indicates a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells as the GFAP+ Schwann cells with their cell bodies and/or processes highlighted in yellow (overlap of green and red) at the peri-graft area. The nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells are presented in the lower panel as the control. The two panels are presented in parallel to simultaneously show the same optical section of the graft.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the experimental conception and design; J.H.J. and C.H.K. contributed to transplantation; S.J.P. and S.C.T. contributed to specimen preparation and microscopy; S.C.T. prepared the figures and drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content; J.H.J. and S.C.T. directed the research project. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain Research Center in National Tsing Hua University for technical support of confocal imaging. This work was supported in part by grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG3C0191 and CMRPG3D0601) and the National Science Council Taiwan (NSC 102-2314-B-182A-012-MY3) to J.H.J., and the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX103-10332EI) and National Science Council (NSC 102-2628-B-007-002-MY2) to S.C.T.

References

- Ahren B. Islet nerves in focus—defining their neurobiological and clinical role. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3152–3154. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliot F., Rutin J., Leenen P.J., Pessac B. Pericytes and periendothelial cells of brain parenchyma vessels co-express aminopeptidase N, aminopeptidase A, and nestin. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;58:367–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A., Abramsson A., Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ. Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanov R., Beaumont T., Dore-Duffy P. Role of central nervous system microvascular pericytes in activation of antigen-primed splenic T-lymphocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;55:578–587. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<578::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton F.B., Rickels M.R., Alejandro R., Hering B.J., Wease S., Naziruddin B., Oberholzer J., Odorico J.S., Garfinkel M.R., Levy M. Improvement in outcomes of clinical islet transplantation: 1999–2010. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1436–1445. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach T.G., Walker R., McGeer E.G. Patterns of gliosis in Alzheimer's disease and aging cerebrum. Glia. 1989;2:420–436. doi: 10.1002/glia.440020605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G., Song S. The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:452–464. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden P., Houtz J., Leach S.D., Kuruvilla R. Sympathetic innervation during development is necessary for pancreatic islet architecture and functional maturation. Cell Rep. 2013;4:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissova M., Shostak A., Shiota M., Wiebe P.O., Poffenberger G., Kantz J., Chen Z., Carr C., Jerome W.G., Chen J. Pancreatic islet production of vascular endothelial growth factor—a is essential for islet vascularization, revascularization, and function. Diabetes. 2006;55:2974–2985. doi: 10.2337/db06-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y.C., Hua T.E., Fu Y.Y., Pasricha P.J., Tang S.C. 3-D imaging and illustration of the perfusive mouse islet sympathetic innervation and its remodelling in injury. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3252–3261. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K., Deisseroth K. CLARITY for mapping the nervous system. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:508–513. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S.R., Shetty A.K., Bradley J.L., Turner D.A. Reactive astrocytes express the embryonic intermediate neurofilament nestin. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1885–1888. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delacour A., Nepote V., Trumpp A., Herrera P.L. Nestin expression in pancreatic exocrine cell lineages. Mech. Dev. 2004;121:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donev S.R. Ultrastructural evidence for the presence of a glial sheath investing the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas of mammals. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;237:343–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00217154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P., Katychev A., Wang X., Van Buren E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:613–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erturk A., Becker K., Jahrling N., Mauch C.P., Hojer C.D., Egen J.G., Hellal F., Bradke F., Sheng M., Dodt H.U. Three-dimensional imaging of solvent-cleared organs using 3DISCO. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:1983–1995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisen J., Johansson C.B., Torok C., Risling M., Lendahl U. Rapid, widespread, and longlasting induction of nestin contributes to the generation of glial scar tissue after CNS injury. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:453–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.Y., Tang S.C. At the movies: 3-dimensional technology and gastrointestinal histology. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(1100–1105):1105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.Y., Lin C.W., Enikolopov G., Sibley E., Chiang A.S., Tang S.C. Microtome-free 3-dimensional confocal imaging method for visualization of mouse intestine with subcellular-level resolution. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:453–465. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.Y., Lu C.H., Lin C.W., Juang J.H., Enikolopov G., Sibley E., Chiang A.S., Tang S.C. Three-dimensional optical method for integrated visualization of mouse islet microstructure and vascular network with subcellular-level resolution. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010;15:046018. doi: 10.1117/1.3470241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genina E.A., Bashkatov A.N., Tuchin V.V. Tissue optical immersion clearing. Expert Rev. Med. Devices. 2010;7:825–842. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goland R., Egli D. Stem cell-derived beta cells for treatment of type 1 diabetes? EBioMedicine. 2014;1:93–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goritz C., Dias D.O., Tomilin N., Barbacid M., Shupliakov O., Frisen J. A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue. Science. 2011;333:238–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1203165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati A.K. Immune response and neurotrophic factor interactions in peripheral nerve transplants. Acta Haematol. 1998;99:171–174. doi: 10.1159/000040832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M.R., Karuparthi P.R., Habibi J., Lastra G., Patel K., Wasekar C., Manrique C.M., Ozerdem U., Stas S., Sowers J.R. Ultrastructure of islet microcirculation, pericytes and the islet exocrine interface in the HIP rat model of diabetes. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2008;233:1109–1123. doi: 10.3181/0709-RM-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson L., Carlsson P.O. Graft vascular function after transplantation of pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2002;45:749–763. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang J.H., Peng S.J., Kuo C.H., Tang S.C. Three-dimensional islet graft histology: panoramic imaging of neural plasticity in sympathetic reinnervation of transplanted islets under the kidney capsule. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;306:E559–E570. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00515.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke M.T., Fujimoto S., Imai T. SeeDB: a simple and morphology-preserving optical clearing agent for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1154–1161. doi: 10.1038/nn.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.H., Choi B., Chess S., Kelly K.M., McCullough J., Nelson J.S. Optical clearing of in vivo human skin: implications for light-based diagnostic imaging and therapeutics. Lasers Surg. Med. 2004;34:83–85. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilje O. The processing and presentation of endogenous and exogenous antigen by Schwann cells in vitro. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:2191–2198. doi: 10.1007/s000180200018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P., Johansson B.R., Leveen P., Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.A., Chung Y.C., Shen M.Y., Pan S.T., Kuo C.W., Peng S.J., Pasricha P.J., Tang S.C. Perivascular interstitial cells of Cajal in human colon. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;1:102–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx V. Microscopy: seeing through tissue. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:1209–1214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone J.L., Kukekov V., Chiang A.S., Steindler D., Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi S., Anitha M., Mallikarjun C., Ding X., Hara M., Parsadanian A., Larsen C.P., Thule P., Sitaraman S.V., Anania F. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor increases beta-cell mass and improves glucose tolerance. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:727–737. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrsen U., Keymeulen B., Pipeleers D.G., Sundler F. Beta cells are important for islet innervation: evidence from purified rat islet-cell grafts. Diabetologia. 1996;39:54–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00400413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyqvist D., Kohler M., Wahlstedt H., Berggren P.O. Donor islet endothelial cells participate in formation of functional vessels within pancreatic islet grafts. Diabetes. 2005;54:2287–2293. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekny M., Nilsson M. Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis. Glia. 2005;50:427–434. doi: 10.1002/glia.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson-Sjogren S., Forsgren S., Taljedal I.B. Peptides and other neuronal markers in transplanted pancreatic islets. Peptides. 2000;21:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer M.K., Mokshagundam S.P., Wyler K., Sundler F., Ahren B., Stagner J.I. Local growth factors are beneficial for the autonomic reinnervation of transplanted islets in rats. Pancreas. 2003;26:392–397. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200305000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards O.C., Raines S.M., Attie A.D. The role of blood vessels, endothelial cells, and vascular pericytes in insulin secretion and peripheral insulin action. Endocr. Rev. 2010;31:343–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street C.N., Lakey J.R., Shapiro A.M., Imes S., Rajotte R.V., Ryan E.A., Lyon J.G., Kin T., Avila J., Tsujimura T. Islet graft assessment in the Edmonton Protocol: implications for predicting long-term clinical outcome. Diabetes. 2004;53:3107–3114. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunami E., Kanazawa H., Hashizume H., Takeda M., Hatakeyama K., Ushiki T. Morphological characteristics of Schwann cells in the islets of Langerhans of the murine pancreas. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 2001;64:191–201. doi: 10.1679/aohc.64.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.C., Chiu Y.C., Hsu C.T., Peng S.J., Fu Y.Y. Plasticity of Schwann cells and pericytes in response to islet injury in mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2424–2434. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2977-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.C., Peng S.J., Chien H.J. Imaging of the islet neural network. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2014;16(Suppl. 1):77–86. doi: 10.1111/dom.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman G., Guz Y., Ivkovic S., Ehrlich M. Islet injury induces neurotrophin expression in pancreatic cells and reactive gliosis of peri-islet Schwann cells. J. Neurobiol. 1998;34:304–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199803)34:4<304::aid-neu2>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas W.E. Brain macrophages: on the role of pericytes and perivascular cells. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1999;31:42–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutelaar M.K., Skidmore J.M., Dias-Leme C.L., Hara M., Zhang L., Simeone D., Martin D.M., Burant C.F. Nestin-lineage cells contribute to the microvasculature but not endocrine cells of the islet. Diabetes. 2003;52:2503–2512. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajkoczy P., Olofsson A.M., Lehr H.A., Leiderer R., Hammersen F., Arfors K.E., Menger M.D. Histogenesis and ultrastructure of pancreatic islet graft microvasculature. Evidence for graft revascularization by endothelial cells of host origin. Am. J. Pathol. 1995;146:1397–1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasir B., Aiello L.P., Yoon K.H., Quickel R.R., Bonner-Weir S., Weir G.C. Hypoxia induces vascular endothelial growth factor gene and protein expression in cultured rat islet cells. Diabetes. 1998;47:1894–1903. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.12.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Tell D., Armulik A., Betsholtz C. Pericytes and vascular stability. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:623–629. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer S., Tsui H., Lau A., Song A., Li X., Cheung R.K., Sampson A., Afifiyan F., Elford A., Jackowski G. Autoimmune islet destruction in spontaneous type 1 diabetes is not beta-cell exclusive. Nat. Med. 2003;9:198–205. doi: 10.1038/nm818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yantha J., Tsui H., Winer S., Song A., Wu P., Paltser G., Ellis J., Dosch H.M. Unexpected acceleration of type 1 diabetes by transgenic expression of B7-H1 in NOD mouse peri-islet glia. Diabetes. 2010;59:2588–2596. doi: 10.2337/db09-1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(Related to Fig. 4.)

Panoramic projection of nestin-GFP+ donor islet cells and their contribution to graft pericytes. The panoramic view of the islet graft was derived by stitching and projection of high-resolution confocal image stacks. Viewers can zoom in to specify the nestin-GFP+ donor cells (panels A and D) under the kidney capsule and the NG2+ pericytes (panels B and E) in both the islet graft and kidney parenchymal domain. In panels C and F, overlay of the two signals, green (nestin-GFP expression) and magenta (NG2+ pericytes), reveals a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells as the perivascular pericytes (white). They resided in the graft domain, but not in the kidney parenchymal domain. Letter ‘G’ indicates the glomerulus.

(Related to Fig. 5E and F.)

Panoramic projection of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath. This figure shows the gross view of the images presented in Fig. 5E and F. Viewers can zoom in to specify the peri-graft Schwann cell network. The gross view also shows a higher density of the GFAP+ Schwann cell fibers at the graft domain in comparison with that in the kidney parenchymal domain. The distribution indicates an intrinsic difference between the islets and the renal microstructures, such as the glomeruli, in association with the neural tissue.

(Related to Fig. 7.)

Pericyte population and Schwann cell network in 3-week grafts. (A) Pericyte population. Panel (i): merged display of the islet graft microstructure, vasculature, and pericyte population under the kidney capsule. Panel (ii): NG2 staining of the pericyte population. The images show the graft revascularization three weeks after transplantation with a prominent presence of the pericytes. (B) Schwann cell network. Panel (i): transmitted light image. Panel (ii): merged display of the Schwann cell network and blood vessels. Panel (iii): projection of the Schwann cell network. Panels (i)–(iii) were taken under the same view. The panoramic display shows that the development of the peri-graft Schwann cell network was still in progress three weeks after transplantation.

(Related to Fig. 3.)

3-D imaging of perivascular pericyte population in the optically cleared islet graft specimen. Two examples were recorded in the first two-thirds of the video (overlay of transmitted light and fluorescence signals). The last third of the video shows the pancreatic islet pericytes in situ, serving as the control and reference to the graft pericytes.

(Related to Fig. 4.)

Tracing the nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells and their contribution to the graft pericytes. The nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells (green) are presented in the upper panel. The lower panel shows the NG2 staining of perivascular pericytes (magenta). The nestin-GFP+ pericytes are identified in the graft domain (white, overlap of green and magenta), not in the kidney parenchyma. The result confirms the donor cells' contribution to the graft pericyte population. The two panels are presented in parallel to simultaneously show the same optical section of the graft.

(Related to Fig. 5.)

3-D imaging and 360° panoramic projection of the islet graft Schwann cell sheath. This video focuses on the middle area of Fig. 5A and B to present the islet graft Schwann cell sheath with high definition. The last third of the video shows the pancreatic islet Schwann cell sheath in situ, serving as the control and reference to the graft Schwann cell sheath.

(Related to Fig. 6.)

Contribution of nestin-GFP+ donor cells to the peri-graft Schwann cell sheath. The upper panel shows an in-depth recording of the overlap of the nestin-GFP (green) and GFAP (red) signals. The result indicates a subpopulation of the nestin-GFP+ donor cells as the GFAP+ Schwann cells with their cell bodies and/or processes highlighted in yellow (overlap of green and red) at the peri-graft area. The nestin-GFP+ islet donor cells are presented in the lower panel as the control. The two panels are presented in parallel to simultaneously show the same optical section of the graft.