ABSTRACT

Sorting nexin 27 (SNX27) controls the endosomal-to-cell-surface recycling of diverse transmembrane protein cargos. Crucial to this function is the recruitment of SNX27 to endosomes which is mediated by the binding of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) by its phox homology (PX) domain. In T-cells, SNX27 localizes to the immunological synapse in an activation-dependent manner, but the molecular mechanisms underlying SNX27 translocation remain to be clarified. Here, we examined the phosphoinositide-lipid-binding capabilities of full-length SNX27, and discovered a new PtdInsP-binding site within the C-terminal 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain. This binding site showed a clear preference for bi- and tri-phosphorylated phophoinositides, and the interaction was confirmed through biophysical, mutagenesis and modeling approaches. At the immunological synapse of activated T-cells, cell signaling regulates phosphoinositide dynamics, and we find that perturbing phosphoinositide binding by the SNX27 FERM domain alters the SNX27 distribution in both endosomal recycling compartments and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-enriched domains of the plasma membrane during synapse formation. Our results suggest that SNX27 undergoes dynamic partitioning between different membrane domains during immunological synapse assembly, and underscore the contribution of unique lipid interactions for SNX27 orchestration of cargo trafficking.

KEY WORDS: Sorting nexin, Phox homology domain, Endosome, FERM domain, Immunological synapse, Phosphoinositide

INTRODUCTION

Phosphatidylinositol phospholipids (PtdInsPs) or phosphoinositides serve as spatial cues that are central to the regulation of numerous cellular processes including membrane trafficking and signal transduction (Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006; Lemmon, 2008; Vanhaesebroeck et al., 2010). These lipids act as biochemical labels that serve to recruit various peripheral membrane proteins to intracellular organelles of the secretory and endocytic system, and in collaboration with proteins that contain lipid-binding domains they elicit specific spatio-temporal signals vital for cellular homeostasis. One such lipid-binding protein superfamily is the phox homology (PX)-domain-containing proteins, also referred to as sorting nexins (SNXs). The PX protein family comprises 49 distinct molecules that possess a PtdInsP-binding PX domain in tandem with many different functional modules (Cullen, 2008; Teasdale and Collins, 2012). The PX proteins decorate various endocytic and secretory organelles, predominantly associating with phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P)-enriched endosomal membranes.

PX-FERM proteins (SNX17, SNX27 and SNX31) are a sub-group of the PX superfamily that contain a defining PtdInsP-binding PX domain, and a C-terminal 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain with an atypical tertiary structure (Ghai and Collins, 2011; Ghai et al., 2011). SNX27 also has an N-terminal PSD95, Discs large, zonula occludens-1 (PDZ) domain that makes it unique within the PX protein family. Previous studies have shown that the PX domain of these proteins binds with high specificity to PtdIns3P, driving their localization to PtdIns3P-enriched early endosomes (Ghai et al., 2011; Stockinger et al., 2002). PX-FERM proteins can then interact with cargo containing NPxY or NxxY motifs, and also PDZ-binding motif (PDZbm) cargo, in the case of SNX27, at the early endosomal membrane (Balana et al., 2011; Bottcher et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2011; Ghai et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2011; Hayashi et al., 2012; Joubert et al., 2004; Knauth et al., 2005; Lauffer et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2007; Steinberg et al., 2013; Temkin et al., 2011; Valdes et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013). This influences the routing of transmembrane cargo trafficking, away from degradative late endosomes and into recycling and retrieval pathways from the endosome back to the plasma membrane. SNX27 has been found to mediate endosomal recycling together with the retromer protein assembly and the actin remodeling Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome and SCAR homolog (WASH)-containing multiprotein complex called the wash regulatory complex (SHRC) (Steinberg et al., 2013; Temkin et al., 2011).

At steady state, SNX27 is found on early endosomal membranes (Gallon et al., 2014; Ghai et al., 2011; Lauffer et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2007; Steinberg et al., 2013; Temkin et al., 2011; Tseng et al., 2014); however in tumor-engaged natural killer cells (MacNeil and Pohajdak, 2007) and antigen-presenting cell (APC)-responsive T-cells (Rincón et al., 2011), endosomal SNX27 undergoes rapid polarization to the immunological synapse. The engagement of T-cells activates distinct members of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) family, causing PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to be concentrated at the immunological synapse (Koyasu, 2003; Lafont et al., 2000). The sustained accumulation of PtdInsP(3,4,5)P3 at the T-cell–APC contact zone has been revealed in several studies that followed the recruitment of a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding pleckstrin homology (PH)-domain-containing protein to the immunological synapse in a PI3K-dependent manner (Costello et al., 2002; Harriague and Bismuth, 2002; Le Floc'h et al., 2013). We and others have found that, upon T-cell activation, SNX27 is sorted into two pools at the immunological synapse, where it is found at both the plasma membrane and on transferrin receptor (TfR)-positive intracellular vesicles thought to be recycling endosomes (MacNeil and Pohajdak, 2007; Rincón et al., 2011; Rincón et al., 2007). In addition, SNX27 was also found in plasma-membrane-enriched membrane fractions in cell surface biotinylation experiments (Hayashi et al., 2012). The mechanism of SNX27 relocalization to the immunological synapse remains unknown.

Here, we use structural modeling, lipid-binding experiments and mutagenesis to identify a new phosphoinositide-binding site within the C-terminal FERM domain of SNX27. Using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) we show that SNX27 binds strongly to the plasma-membrane-enriched phosphoinositides PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns(3,4)P2, as well as the late endosomal phospholipid PtdIns(3,5)P2, but not to early endosome-enriched PtdIns3P. This interaction is mediated by a highly basic surface of the FERM domain that is conserved in SNX27, but is not present in other PX-FERM proteins. Homology modeling and docking studies show that the SNX27 atypical FERM domain binds PtdInsPs in a manner that is distinct to that of distantly related FERM, pleckstrin homology (PH) and phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains. We next analyzed the contribution of the PtdInsP-binding site to SNX27 localization during immunological synapse formation. Although not strictly required for polarized SNX27 accumulation at the cell–cell contact area, impaired PtdInsP recognition by the FERM domain affected the sustained localization of the protein at the polarized recycling endosomal compartment, and impaired its colocalization with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-enriched membranes during initial synapse formation. Our experiments suggest that recognition of PtdInsP derivatives by the SNX27 FERM domain contributes to the dynamic distribution of SNX27 at the immunological synapse.

RESULTS

SNX27 binds a range of PtdInsPs through its atypical FERM domain

We have previously shown that the SNX27 PX domain interacts with the endosomal lipid PtdIns3P with high specificity, similarly to SNX17 (Ghai et al., 2011). Recently it has also been shown that the related protein SNX31 also binds exclusively to PtdIns3P (Vieira et al., 2014). Studies of full-length SNX17 confirmed that this protein showed identical specificity for PtdIns3P as its isolated PX domain (Ghai et al., 2011). Here, we tested the affinity of full-length SNX27 for various PtdInsP species by ITC using water-soluble diC8 lipids. Remarkably, we observed that SNX27 interacts robustly with all PtdInsP species tested. Under the conditions used the binding is enthalpically driven with dissociation constants (Kds) ranging from 3 to 7 µM. (Fig. 1; supplementary material Table S1). This broad PtdInsP specificity is in contrast to the strong PtdIns3P specificity of full-length SNX17, or the isolated SNX27 PX domain (Ghai et al., 2011), and indicates that other domains of SNX27 contribute to additional PtdInsP interactions.

Fig. 1.

SNX27 binds PtdInsP lipids through its FERM domain. The binding of SNX27 or the SNX27 FERM domain to water-soluble PtdInsP species was measured by ITC. The full-length SNX27 protein is able to bind to all PtdInsPs tested, whereas the FERM domain binds bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsP species but not PtdIns3P. For detailed results refer to supplementary material Table S1. Experiments were performed at 25°C using 20 µM protein in the cell and 500 µM PtdInsPs injected from the syringe. Top panels show raw data, and bottom panels show integrated normalized data.

Both PDZ and FERM domains have been shown to have PtdInsP-binding activities in some proteins (reviewed in Balla, 2005). To define the alternative PtdInsP-binding domain of SNX27, we next tested both a construct lacking the PDZ domain (i.e. containing only the PX and FERM domain), and a construct containing the SNX27 FERM domain only. The PtdInsP binding of these constructs was again assessed using ITC. We observed that the PDZ-domain-deficient SNX27 interacts with all the PtdInsPs tested identically to the full-length protein (supplementary material Fig. S1; Table S1), confirming that the PDZ domain of SNX27 does not play a role in the interaction with PtdInsPs, and in line with previous studies (Lunn et al., 2007). Notably, although the SNX27 PDZ domain possesses a distinct positively charged basic surface (Balana et al., 2011; Gallon et al., 2014), this is clearly not involved in PtdInsP binding.

Similar to the full-length protein, we found that the SNX27 FERM domain alone interacts with all the tested bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsPs (often referred to as PIP2 and PIP3, respectively) (Fig. 1; supplementary material Table S1). However, the mono-phosphorylated PtdIns3P showed a greatly reduced affinity, with a Kd of greater than 100 µM, versus 7 µM for the full-length protein, and a markedly reduced enthalpy of binding. Taken together, these results suggest that SNX27 possesses two alternative PtdInsP-headgroup-binding sites, a PtdIns3P-specific binding pocket within the PX domain (Ghai et al., 2011), and a new site within the FERM domain that preferentially recognizes both bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsP species.

A new PtdInsP-binding site on the atypical SNX27 FERM domain

The finding that SNX27 is the only member of the PX-FERM family that can recognize PtdInsPs other than PtdIns3P prompted further investigation of the structural mechanism underpinning its differing PtdInsP specificity. Recently, we reported the crystal structure of the structurally atypical SNX17 FERM domain (Ghai et al., 2013), which is closely related to SNX27, and employed this as a template to generate a SNX27 homology model (Fig. 2). As expected, the SNX27 model is highly similar to the SNX17 atypical FERM domain in overall structure, possessing the three modules, F1, a truncated F2 and F3. One major difference is that SNX27 lacks the extended loop formed between the β5C–β6C secondary structure elements seen in the SNX17 F3 subdomain. This observation is in agreement with structure-based sequence alignment of the F3 subdomain of the PX-FERM proteins (Fig. 2C).

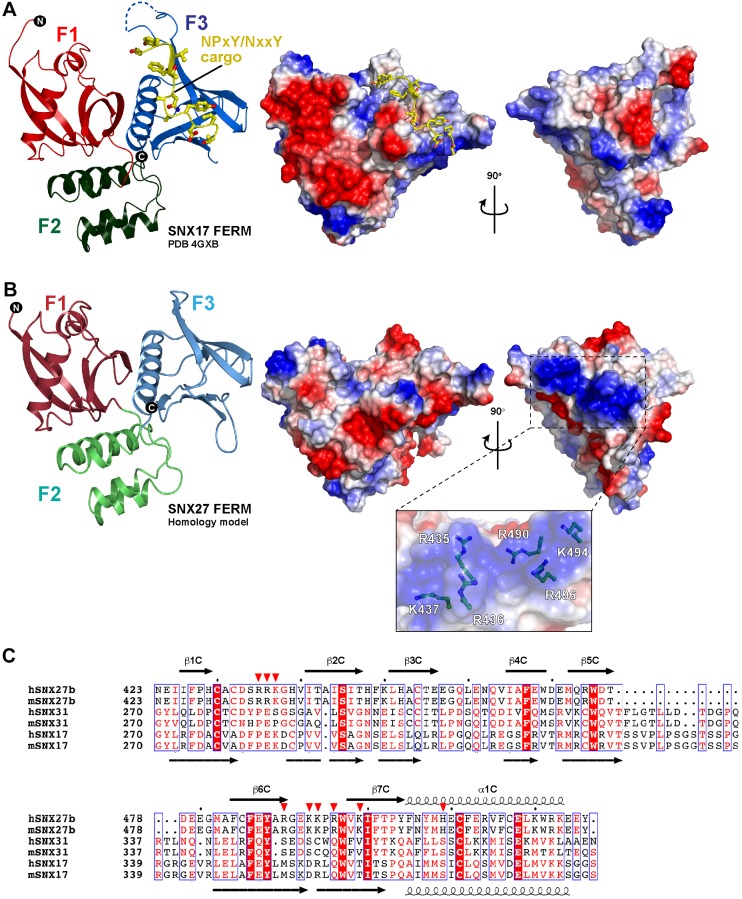

Fig. 2.

Homology modeling reveals a putative PtdInsP-binding site in the SNX27 F3 subdomain. (A) The left panel shows the crystal structure of the SNX17 FERM domain in complex with an NPxY/NxxY sorting peptide from P-selectin, highlighting the three sub-modules F1, F2 and F3 in red, green and blue, respectively (PDB ID 4GXB) (Ghai et al., 2013). The right panels show perpendicular views of the SNX17 surface colored for electrostatic potential. Negatively charged surfaces are red and positively charged surfaces are blue, colors are contoured from −0.5 V to +0.5 V. (B) The human SNX27 FERM domain homology model is shown with analogous representations to those shown for SNX17 in A. The inset shows the positively charged putative PtdInsP-binding region with specific side chains forming the pocket. (C) A combined sequence alignment and secondary structure comparison of the F3 subdomain of human (h) and mouse (m) SNX17, SNX27 and SNX31. Secondary structure predictions for SNX27 were calculated with JPRED (Cole et al., 2008; www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/www-jpred/) and are indicated above. Secondary structure elements for SNX17 derived from the crystal structure are indicated below the alignment. Alignments were made with ESPript 2.2 (Gouet et al., 1999) (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/). Red inverted triangles indicate the positively charged amino acids constituting the basic patch on the F3 module of SNX27, which are absent in SNX17 and SNX31. Structural images were rendered with CCP4mg (McNicholas et al., 2011).

The most striking new feature of the SNX27 FERM domain is the presence of a highly positively charged region between the β1C–β2C loop and β6C strand of the F3 submodule. This basic patch of SNX27 is comprised of a cage of positively charged arginine and lysine residues, and is a likely candidate site for interaction with negatively charged PtdInsP species (Fig. 2B). Comparison of the SNX27 FERM domain homology model with SNX17 in complex with the P-selectin intracellular domain (ICD) (Ghai et al., 2013) reveals that this putative PtdInsP-binding pocket is on the reverse face of the F3 submodule to the NPxY/NxxY motif present in the cargo.

To confirm that this positively charged pocket constitutes the PtdInsP-binding site, several charge-reversal mutations were made in the putative binding site of full length SNX27 including a triple mutant R435E/R436E/K437E (which we refer to as RRK/E), and single point mutations of R490E and R496E. All three mutants were subjected to circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and showed identical secondary structures to the wild-type protein indicating they are correctly folded (supplementary material Fig. S2). Confirming the importance of this basic patch, all mutants inhibited the interaction with bi- and tri-phosphosphorylated PtdInsP species tested under these conditions (Fig. 3A). However, all mutants exhibited PtdIns3P-binding characteristics indistinguishable from wild-type SNX27, confirming that the PX domain alone mediates the PtdIns3P interaction (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, reciprocal mutation of the PX domain PtdIns3P-binding site (R196A/Y197A), perturbed the PtdIns3P interaction but had no effect on the binding of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data show that these basic residues of the FERM domain mediate association of SNX27 with bi- and tri-phosphosphorylated PtdInsP but not the endosomal-enriched PtdIns3P.

Fig. 3.

Mutational analysis confirms the putative PtdInsP-binding site on the SNX27 FERM domain. (A) The amino acids contributing to the basic patch on the F3 region of the SNX27 FERM domain (see Fig. 2B,C) were mutated to test the effect on PtdInsP binding by using ITC. The binding of SNX27 R490E, R496E, R435E/R436E/K437E (RRK-E) and wild-type (WT) SNX27 are shown in red, green, blue and black respectively. No binding signal was observed for any of the mutants, confirming the basic region on SNX27 F3 is the PtdInsP-binding site. All mutants were correctly folded as shown in supplementary material Fig. S1. (B) All SNX27 FERM domain mutants demonstrate binding to PtdIns3P with identical affinity to wild-type SNX27. (C) Mutation of the SNX27 PX domain (R196A/Y197A) abolishes PtdIns3P binding (red trace) but does not inhibit PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 binding (black trace). Refer to supplementary material Table S1 for detailed thermodynamic parameters. All experiments were performed at 25°C using 20 µM protein in the cell and 500 µM PtdInsPs injected from the syringe. Top panels show raw data and bottom panels show integrated normalized data.

The sequence alignment of SNX17, SNX31 and SNX27 F3 lobes shows that the positively charged residues of the lipid-binding pocket of SNX27 are not conserved between the PX-FERM family members, as was also evident from comparison of the electrostatic surface potentials of SNX17 and SNX27 (Fig. 2). Although the PX-FERM family members all bind similar NPxY/NxxY peptide motifs, such as those found in APP and P-selectin, through their FERM domains (Ghai et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2011), the PtdInsP-binding activity of the SNX27 FERM domain is a specific innovation.

Mechanism of PtdInsP binding by the SNX27 FERM domain

The potential mode of SNX27 FERM binding to bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsPs was further investigated by molecular docking using the HADDOCK program (Dominguez et al., 2003). We defined Arg435, Arg436, Lys437, Arg490, Lys493, Lys494, Arg496 and Arg499 as ‘active’ (i.e. lipid-interacting) residues based on the mutagenesis data, solvent accessibility and sequence conservation, and imposed proximity restraints between these residues and the bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsPs. The in silico docked structures define putative intermolecular contacts formed by phospholipids with the SNX27 FERM domain. Models shown in Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B suggest that the 3-phosphate of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in the docked structure forms a hydrogen bond with Arg496, that the 4-phosphate forms a hydrogen bond with Arg490 and that the 5-phosphate is hydrogen bonded with the Arg436 side chain. We also docked PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns(4,5)P2 with the SNX27 FERM domain homology model (Fig. 4C,D). In all of the docked structures we found that the residues from the basic patch of the SNX27 FERM domain formed a network of hydrogen bonds with the lipid headgroups, that the 5-phosphate moiety contacted the side chain of Arg436, and the 1-phosphate is in contact with Lys499. Note that no stable contacts were made between SNX27 and the acyl chain of the docked PtdInsPs, and lysine residues around the putative lipid-binding pocket contributed to the complementary electrostatic environment.

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of binding to PtdInsP species by the SNX27 FERM domain. (A) SNX27 FERM domain binding to PtdInsP headgroups was modeled in silico using HADDOCK (de Vries et al., 2010) for molecular docking. Docking restraints were imposed based on mutagenesis data, sequence conservation and solvent accessibility considerations. The SNX27 FERM domain is represented as an electrostatic surface highlighting the PtdInsP-binding site as a red-dashed bordered ellipse. The structure depicts the docked complex with the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 headgroup. (B–D) Close up of the PtdIns-binding site of the SNX27 FERM domain showing the docking coordination of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(3,5)P3 and PtdIns(4,5)P2, respectively. The SNX27 FERM domain is shown as light-blue ribbons with the coordinating amino acids depicted in blue ball and sticks, and the PtdInsP headgroups are shown as red and white ball and sticks. (E) Ribbon representation of SNX27 FERM domain model with docked PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 compared to the crystal structure of the radixin FERM domain in complex with Ins(1,4,5)P3 (PDB ID 1GC6). The three submodules F1, F2 and F3 are colored as in Fig. 3 and the bound PtdInsPs are depicted in ball and stick representation. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 binds to the β1–β2 loop of the F3 lobe of SNX27, whereas Ins(1,4,5)P3 binds radixin in the cleft between the F1 and F3 modules. (F) The SNX27 F3-domain–PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 model is compared with the PH domains of PLCδ1 (PDB ID 1MAI) and Grp1 (PDB ID 1FHW) in complex with Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 respectively. PLCδ1 binds PtdInsPs in the so-called ‘canonical’ orientation whereas Grp1 binds PtdInsPs in the ‘non-canonical’ mode. Also shown is the structure of the Dab1 PTB domain in complex with Ins(4,5)P2 and ApoER2 peptide (PDB ID 1NU2). All structures were superimposed on each other and are shown with the same orientation. The PtdInsP molecules are shown as red and white ball and stick models. In the case of Dab1, the ApoER2 peptide is shown in yellow and is rendered in ball and stick representation. The residues coordinating the PtdInsP are shown in blue ball and stick representation. The comparisons highlight that the SNX27 PtdInsP pocket is unique, but is in approximately the same location as seen for canonical PH domain interactions. (G) Schematic of a membrane-anchored SNX27 FERM domain bound to an NPxY/NxxY peptide sequence from a transmembrane cargo and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, demonstrating the synergistic recognition of membrane ligands through structurally distinct regions in the FERM domain. The schematic combines the SNX27 homology model with docked PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and the P-selectin NPxY/NxxY cargo peptide from the crystal structure of the complex with the homologous SNX17 FERM domain (Ghai et al., 2013).

To date only one structure of a FERM domain in complex with a PtdInsP ligand has been reported; that of radixin in complex with Ins(1,4,5)P3 (Hamada et al., 2000). Although the overall fold of the radixin FERM domain is related to SNX27, our data shows that the SNX27 FERM domain associates with phospholipids in a completely different manner (Fig. 4E,F). In radixin, the Ins(1,4,5)P3 ligand sits in a basic cleft between the F1 and F3 subdomains. This basic cleft is absent in SNX27, which instead interacts with phospholipids through the basic patch in the β1C–β2C loop region of the F3 lobe.

Despite little sequence similarity, the F3 lobe of the FERM domain is structurally related to a distinct domain class called the PH and PTB fold. Many PH domains, and a number of PTB domains, have also been shown to bind to specific PtdInsPs to enable membrane recruitment. PH domains generally use one of two possible binding modes, referred to as canonical and non-canonical (DiNitto and Lambright, 2006). Comparison of SNX27 to several PH and PTB domain structures suggests a binding mechanism distinct from any of these arrangements (Fig. 4F). The PH domains of both PLCδ1 (Ferguson et al., 1995) and Grp1 (Ferguson et al., 2000) bind PtdInsPs in a superficially similar location, but employ different side chains. The Dab1 PTB domain (Stolt et al., 2003) uses a structurally unique surface including an additional α-helix not present in SNX27 or the PH domain family. The SNX27 PtdInsP-binding mechanism is thus distinct from that of these distantly related domains. Similar to the Dab1 PTB domain, however, the SNX27 F3 lobe is able to recognize both transmembrane cargo peptide sequences and PtdInsP lipids through discrete binding surfaces (Fig. 4G).

PtdInsP binding by the SNX27 FERM domain is not required for endosomal localization in HeLa cells

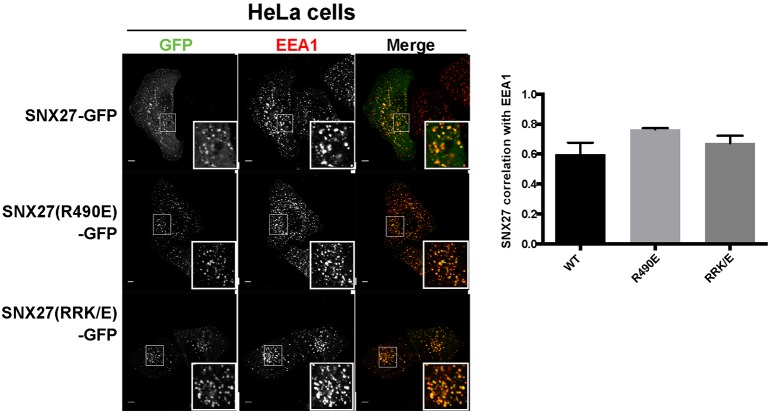

SNX27 has been shown to associate primarily with early endosomal membranes in most cell types (Balana et al., 2011; Gallon et al., 2014; Ghai et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2011; Joubert et al., 2004; Lauffer et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2007; MacNeil et al., 2007; MacNeil and Pohajdak, 2007; Tseng et al., 2014). It has been recently observed that, compared to its homologs SNX17 and SNX31, SNX27 might be less sensitive to PtdIns3P-depletion by the drug wortmannin or mutation of the canonical PtdIns3P-binding pocket of the PX domain, suggesting that it has additional membrane-anchor points (Tseng et al., 2014). Here, we again confirmed that SNX27 is recruited to early endosomal membranes by comparing the intracellular localization of SNX27–GFP to that of the known endosomal marker (EEA1) in HeLa and A431 cells (Fig. 5; supplementary material Fig. S3). We also found that the SNX27(R490E)–GFP and SNX27(RRK/E)–GFP PtdInsP-binding mutants showed strong overlap with the early endosomal marker in both cell types, consistent with their normal interaction with the endosomal lipid PtdIns3P in vitro. This data confirms that in HeLa and A431 cells SNX27 is endosomal, and FERM domain mutations have little effect on endosomal localization.

Fig. 5.

Endosomal localization of SNX27 in HeLa cells is not dependent on FERM domain interaction with PtdInsP lipids. HeLa cells were transfected with GFP–SNX27, GFP–SNX27 R490E and RRK/E mutants and colocalization with the early endosomal marker EEA1 was assessed by using immunofluorescence microscopy. Wild-type (WT) GFP–SNX27 and its mutants all display the typical punctate staining of the early endosome and overlap extensively with EEA1. Similar results are found in A431 cells (supplementary material Fig. S3). Scale bars: 5 µm. The graph in the right panel shows Pearson correlation coefficients (means±s.e.m.) for the colocalization of SNX27 with EEA1, demonstrating no alteration in intracellular distribution for the PtdInsP-binding mutants.

The PtdInsP-binding site of the SNX27 FERM domain contributes to its localization to recycling endosomes in T lymphocytes

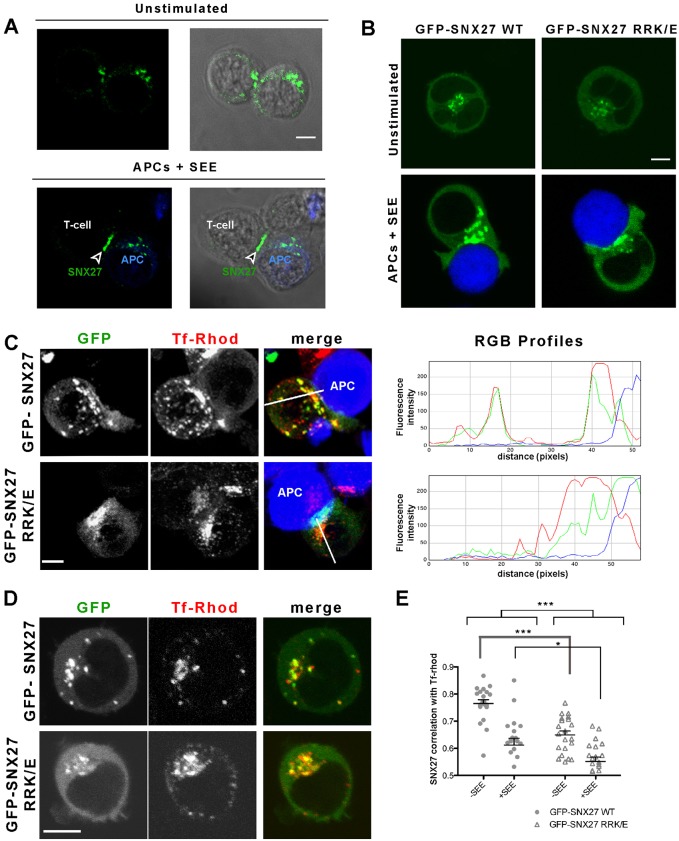

In T-cells challenged with activated APCs, GFP–SNX27 localizes to the immunological synapse, where it is observed on intracellular TfR-positive vesicles believed to represent endosomal recycling compartments (ERCs), and also on regions of the cell surface coincident with the supramolecular activation clusters (SMACs) formed at the cell–cell adhesion (Rincón et al., 2011). As shown in Fig. 6A, we confirmed that the endogenous SNX27 protein (detected by indirect antibody labeling) is also found in vesicular structures (Fig. 6A, top), and is recruited to the immunological synapse in Jurkat T-cells interacting with APCs charged with Staphylococcal enterotoxin E (SEE) superantigen (Fig. 6A, bottom).

Fig. 6.

SNX27 recruitment to recycling endosomes is enhanced by PtdInsP-binding to the FERM domain. (A) Endogenous SNX27 is found on punctate membrane structures in unstimulated Jurkat T-cells (top). Following activation by SEE-charged APCs, SNX27 is recruited to the T-cell immunological synapse (arrowhead). Scale bar: 3 µm. (B) Recruitment of the PtdInsP-binding mutant GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) is very similar to the wild-type (WT) GFP–SNX27 protein at the immunological synapse following APC stimulation. At the immunological synapse, SNX27 is found at the plasma membrane and internal vesicles as shown previously (Rincón et al., 2011). Scale bar: 3 µm. (C) Z-stack projection showing that, following synapse formation, wild-type GFP–SNX27 but not the PtdInsP-binding mutant colocalizes with TfR-positive compartments, suggesting a defect in the ability of the mutant to stably associate with endosomal recycling compartments (ERCs). Densitometric analysis of the distribution of GFP–SNX27 WT or the RRK/E mutant and Tf–Rhodamine (Tf-Rhod) along the line in each type of cells is shown in the panels on the right. (D) At steady-state, both the wild-type GFP-SNX27 and the PtdInsP-binding mutant GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) are colocalized with Tf-positive ERCs, but quantification of colocalization of WT and mutant SNX27 with Tf-Rhod (E) suggests its overall ERC membrane localization is significantly reduced. The bars show the mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001 (two-way ANOVA; n>15). Representative experiments are shown for A–D. Scale bar: 3 µm.

Endocytic trafficking and endosomal recycling of receptors is crucial for maintaining the synapse (reviewed in Finetti and Baldari, 2013; Yuseff et al., 2009). In addition, various signaling processes are upregulated at the synapse, one result of which is increased local concentrations of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 through the action of PI3K (Costello et al., 2002; Harriague and Bismuth, 2002; Le Floc'h et al., 2013). We hypothesized that the PtdInsP-binding site of the SNX27 FERM domain might therefore play a role in recruitment to the immunological synapse. As shown in Fig. 6B, the PtdInsP-binding mutant GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) displays punctuate endosomal localization in unstimulated Jurkat T-cells, as in HeLa and A431 cells (Fig. 5; supplementary material Fig. S3). As originally described (Rincón et al., 2011), when in contact with SEE-loaded APCs, some GFP–SNX27-positive vesicles showed an initial rapid displacement to the contact area, followed by relocation of the entire GFP–SNX27-positive compartment at later time points (Fig. 6B). The PtdInsP-binding mutant GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) showed a very similar recruitment to the immunological synapse as the wild-type protein, suggesting that the PtdInsP-binding site within the FERM domain is not absolutely required for SNX27 polarized localization (Fig. 6B).

To better assess differences in endosomal localization during immunological synapse formation, we measured the overlap of both GFP–SNX27 and GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant with internalized TfR (as labeled by Rhodamine-coupled Tf) as a marker for ERCs. After stimulation of T-cells by SEE-charged APCs, TfR-enriched endosomes localized to the cell–cell contact area. RGB profiles showed that GFP–SNX27 maintained significant overlap with the TfR-positive recycling organelles, with some labeling at the contact area (Fig. 6C, top). The PtdInsP-binding mutant was also found at the cell–cell contact but failed to colocalize with TfR-positive recycling compartments following immunological synapse formation (Fig. 7C, bottom). A similar analysis in resting cells showed that the GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant colocalized with vesicles positive for endocytosed TfR (Fig. 6D). However, there was a significant decrease in TfR colocalization for the GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant compared with wild-type SNX27, both during basal and polarized recycling conditions (Fig. 6E). This defect was the result of diminished GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) endosomal association, measured as the ratio of punctate-to-cytosolic fluorescence (supplementary material Fig. S4). Overall, whereas blocking PtdInsP binding by the FERM domain did not grossly impair SNX27 membrane localization during immunological synapse formation, an increased cytosolic fluorescence in cells expressing the GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant appeared to correlate with defective localization to the endosomal recycling compartments. Time-lapse imaging of Jurkat T-cells simultaneously transfected with cherry–SNX27 and GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) proteins further confirmed similar translocation dynamics with loss of endosomal labeling of the FERM mutant (supplementary material Movie 1).

Fig. 7.

SNX27 transiently accumulates at discrete PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns3P-enriched sites during initial T-cell–APC contact. Jurkat T-cells were stimulated with SEE-pulsed APCs after co-transfection of the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding probe DsRed2–PH-Akt with either GFP–SNX27 (A) or GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) mutant (B). At the initial contact, wild-type GFP–SNX27 shows strong overlap with the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 probe, but not at later times (20 min), as GFP–SNX27 accumulates in intracellular compartments and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 shows an apparent redistribution to peripheral cell contact areas. In contrast, the PtdInsP-binding mutant SNX27 shows little colocalization with the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 probe at any stage during synapse formation. Arrows indicate the location of the immunological synapse. (C) In resting T-cells, both GFP–SNX27 and GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) show significant colocalization with PtdIns3P-positive intracellular compartments. Resting Jurkat T-cells were co-transfected with the PtdIns3P-binding probe Cherry–FYVE and either GFP–SNX27 or the GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) mutant. The accumulation of SNX27 and DsRed2-PH-AKT at the initial synapse is shown in expanded regions. (D) Following stimulation with SEE-pulsed APCs, intracellular PtdIns3P-postive vesicles localized to the contact area outside the limits of the immunological-synapse-concentrated GFP–SNX27 and GFP–SNX27 (RRK/E) mutant pools. Scale bars: 3 µm.

Polarized generation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 correlates with initial membrane recruitment of SNX27 during immunological synapse formation

Activation of type I PI3K is one of the initial signals triggered by T-cell receptor (TCR)–APC contact. Generation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 by PI3K at the membrane triggers activation of downstream signals, facilitating actin reorganization and increased endocytosis. We next compared the recruitment of SNX27 to the immunological synapse with a fluorescent sensor domain for PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (DsRed2–PH-Akt). In resting cells the Akt PH domain showed plasma membrane localization, and was then rapidly concentrated at the contact area on initial formation of the immunological synapse (Fig. 7A,B), similar to what has been observed previously (Costello et al., 2002; Harriague and Bismuth, 2002). Interestingly at later times the Akt PH domain accumulated at the distal and peripheral areas of cell–cell contacts, possibly as a result of the strong signals provided by integrin or other adhesion molecules at this zone. GFP–SNX27 consistently showed clear colocalization with DsRed2–PH-Akt at the initial contact but not at later times of synapse maturation, where it accumulated in distinct vesicular compartments (Fig. 7A,B). These experiments suggest that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 might promote initial SNX27 localization at the immunological synapse membrane, but that SNX27 localization does not strictly follow PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 at all time points. Interestingly, in the case of the PtdInsP-binding mutant GFP–SNX27(RRK/E), we could never detect any colocalization with the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 sensor, although central immunological synapse localization was observed at later times. Immunological synapse formation contributes to sustained signaling through delivery of signaling and scaffold proteins such as the TCR or LAT from endosomal recycling pools (Das et al., 2004; Larghi et al., 2013). PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 dynamics point to an initial accumulation of this lipid prior to polarized recycling, and suggest that recognition of PtdInsP lipids by the SNX27 FERM domain could favor its localization to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-enriched membrane microdomains during these early stages.

Although endosomal localization of SNX27 requires PtdIns3P binding by its PX domain (Lunn et al., 2007), a proportion of SNX27 still accumulates at the immunological synapse even after PX domain mutation (Rincón et al., 2011). We next compared the dynamics of GFP–SNX27 or the GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant with a well-characterized PtdIns3P sensor formed by two tandem Fab1p, TOTB, Vac1, EEA1 (FYVE) domains fused to cherry protein (cherry–FYVE) (Wen et al., 2008). Both GFP–SNX27 and the GFP–SNX27(RRK/E) mutant show substantial overlap with PtdIns3P-positive intracellular compartments in unstimulated T-cells (Fig. 7C). When in contact with SEE-loaded APCs, however, PtdIns3P-enriched vesicles accumulated at discrete locations delimiting the GFP–SNX27-positive compartment, often at two major foci at the periphery of the synapse (Fig. 7D; supplementary material Movie 2). Taken together, these results suggest that SNX27 localization at the immunological synapse is not strictly dependent on either PtdIns3P or PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 association, but that dynamic changes in its PtdInsP interactions might lead to segregation to distinct membrane domains.

DISCUSSION

Diverse cellular stimuli can lead to changes in the membrane lipid composition that modulate the recruitment of numerous protein machineries regulating signaling, trafficking, and membrane remodeling. SNX27 is known to associate with early endosomes and control sorting of PDZbm- and, potentially, NPxY/NxxY-containing cargo to the cell surface (Balana et al., 2011; Ghai et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2011; Joubert et al., 2004; Lauffer et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2007). This early endosomal recruitment is dependent on PX-domain–PtdIns3P interaction. Our data demonstrates, however, that SNX27 not only binds to PtdIns3P but also recognizes bi- and tri-phosphorylated PtdInsPs. Comprehensive biophysical studies in conjunction with mutagenesis and molecular modeling indicate that SNX27 has two distinct PtdInsP-headgroup-binding sites. Within its PX domain is the canonical and well-characterized PtdIns3P-specific binding pocket required for endosomal localization (Ghai et al., 2013; Lunn et al., 2007; Rincón et al., 2011). Within the FERM domain, however, is a second previously unidentified site with high affinity for PtdInsP species enriched at the plasma membrane and late endosomal compartments.

PX-FERM proteins SNX17, SNX27 and SNX31 possess overlapping lipid- and cargo-binding properties, that might confer some redundant functional characteristics to these molecules (Ghai et al., 2013). SNX27, however, possesses a unique PDZ domain involved in alternative cargo trafficking (Cai et al., 2011; Gallon et al., 2014; Lauffer et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2007; Steinberg et al., 2013; Temkin et al., 2011; Valdes et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013), and our results now suggest an additional unique property of this protein with respect to lipid headgroup association, such that it interacts with PtdInsP species not bound by the other family members. Sequence analyses of the PX-FERM proteins highlight positively charged residues found exclusively in SNX27, which are structurally predicted to form a contiguous basic surface on the F3 module, and we find this pocket is required for the differing PtdInsP-binding specificities of the protein. The PtdInsP-binding site on the atypical SNX27 FERM domain is entirely distinct from other structurally related FERM, PTB and PH domains, although the binding location is superficially in a similar location to a ‘canonical’ PH domain interaction site. Interestingly, the SNX27 PtdInsP-binding pocket is adjacent to the NPxY/NxxY cargo recognition site (Ghai et al., 2013), separated only by three antiparallel β-strands (Fig. 4G). This raises the possibility that cargo and PtdInsP binding by the FERM domain might be allosterically regulated. It is also important to note that the soluble signaling molecule Ins(1,4,5)P3 (IP3), derived from PtdIns(4,5)P2 by phospholipase Cγ, will likely bind to SNX27 in a similar manner to that by membrane-associated PtdInsP headgroups, and could potentially mediate such allosteric effects if they occur.

Apart from allosteric regulation, coordinated binding of NPxY/NxxY cargo and PtdInsP lipids by the SNX27 FERM domain might impact on membrane attachment through the process of coincidence detection (Carlton and Cullen, 2005; Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006). This phenomenon has been observed in Rap1-interacting adaptor molecule (RIAM), which contains both Ras-association and PH domains and requires both Rap1 GTPase interaction, mediated by the Ras-association domain, and PtdInsP binding, mediated by the PH domain, for cell surface recruitment in activated T-cells (Wynne et al., 2012). The previous findings showing that SNX27 can associate with a small GTPase through its Ras-association-domain-related F1 module (Balana et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2013; Ghai and Collins, 2011; Ghai et al., 2011; Loo et al., 2014), and the discovery here that it can bind PtdInsP species through the F3 module present a tempting parallel to the RIAM system, and suggests that PtdInsP, cargo and GTPase interactions may co-operatively contribute to membrane localization of SNX27 following certain cell stimuli.

Although the precise role of SNX27 at the immunological synapse is still unclear, its recruitment to the T-cell–APC contact zone suggests that it plays a role in recycling, transport and signaling of cargo receptors required for maintenance and signaling of the immunological synapse, in complex with retromer and the SHRC actin-remodeling assembly (Gallon et al., 2014; Piotrowski et al., 2013; Steinberg et al., 2013; Temkin et al., 2011). The synapse is exquisitely regulated through a balance of endocytosis and recycling of many different receptors (reviewed in Finetti and Baldari, 2013; Yuseff et al., 2009). These include several crucial molecules, such as LAT, CD3 and LFA-1, which have potential SNX27-binding NPxY/NxxY sequences, and others including CD28 and the T-cell receptor (TCR) itself whose recycling depends on SHRC activity (Piotrowski et al., 2013). In fact the β2 integrin subunit of LFA-1 has been shown to bind SNX27 in vitro in peptide arrays (Ghai et al., 2013). Furthermore, the interaction of SNX27 with cytoplasmic signaling molecules, including small GTPases (Balana et al., 2013; Ghai et al., 2011), diacylglycerol kinase ζ (DGKζ) (Rincón et al., 2011; Rincón et al., 2007), and cytohesin-associated scaffolding protein (CASP) (MacNeil et al., 2007), suggests that it has an additional or related role in the scaffolding of signaling complexes.

The formation of the immunological synapse is initiated by signaling through the TCR, which triggers a complex rearrangement of the cytoskeleton together with polarization of the microtubule-organizing centre (MTOC) and internal organelles including the Golgi, secretory vesicles and recycling endosomes (Finetti and Baldari, 2013; Yuseff et al., 2009). Many PtdInsP-binding proteins are recruited to the cell surface through the binding of PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, the latter generated transiently through the action of PI3K enzymes stimulated by cell signaling. In activated T-cells, these lipids accumulate at the immunological synapse and are able to recruit a variety of effector molecules (Costello et al., 2002; Harriague and Bismuth, 2002; Koyasu, 2003; Zhang et al., 2009), and PtdInsPs are also essential mediators of cytoskeletal and actin remodeling at the membrane interface (Saarikangas et al., 2010). We postulated that polarized recruitment of SNX27 to the immunological synapse might at least in part be regulated by association with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 upon cell stimulation, and our data suggests that SNX27 recruitment during the initial stages of immunological synapse formation might be promoted by PtdInsP interaction with the FERM domain. However, although SNX27 appears to colocalize with PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-rich membrane regions at early stages, it is excluded from such regions at later stages of immunological synapse formation. Thus, SNX27 does not remain stably associated with these membrane domains at all times. Similarly, prior to T-cell activation, SNX27 is present on PtdIns3P-enriched organelles (presumably early or sorting endosomes), but at later times it also localizes to distinct membrane regions. In addition, perturbing the FERM domain PtdInsP interaction significantly reduces the association of SNX27 with endosomal recycling compartments. Overall, this suggests a model where the localization of SNX27 at the synapse involves dynamic partitioning between different membrane domains, which is regulated in ways that remain to be defined. Further experiments will be required to determine whether the ability of SNX27 to bind PtdInsP normally during immunological synapse formation affects SNX27 function in the recycling of cargo during antigen recognition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular biology and cloning

In vitro assays with purified proteins used mouse SNX27 isoform b (UniProt Q3UHD6-2), except that human SNX27 isoform a (UniProt Q96L92) was used in Fig. 3C; for localization studies in HeLa and A431 cells mouse SNX27 isoform b was used (Fig. 5; supplementary material Fig. S3); for cellular studies in Jurkat T-cells, mouse SNX27 isoform a was used (Figs 6,7). For bacterial expression, cDNAs encoding mouse SNX27 isoform b (amino acids 1–526), SNX27ΔPDZ (amino acids 156–526) and SNX27 FERM (amino acids 271–526) were cloned into the pMCSG7 vector for expression with an N-terminal His tag and a tobacco etch virus cleavage site (Eschenfeldt et al., 2009). All mutant constructs were generated using the QuikChange® Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Human SNX17 was cloned into pEGFP-N1 for expression in mammalian cells with a C-terminal GFP tag. Mouse SNX27b and R490, R496 and R435E/R436E/K437E (RRK/E) mutants were cloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector for expression in HeLa and A431 cells with a C-terminal GFP tag. The mouse GST-tagged SNX27a and SNX27 (R196A/Y197A) constructs were as described previously (Rincón et al., 2011), as was the mouse N-terminal GFP-tagged SNX27a in pEGFP-C2 (Rincón et al., 2007). Mouse GFP–SNX27a RRK/E was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis as described above. The pDsRed2-PH-Akt was prepared by excising the PH domain from the PMT2-PH construct (a gift from Julian Downward, Division of Cancer Biology, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK) and subcloned into the pDsRed2 vector. The pmCherry-C2-2xFYVE construct (cherry–FYVE) was as described previously and was a kind gift from Frederic Meunier (Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) (Wen et al., 2008).

Recombinant protein expression and purification

SNX27 constructs were expressed and purified as described previously (Ghai et al., 2011). Briefly, proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3)/pLysS Escherichia coli cells at 20°C, followed by induction with 0.5 mM IPTG, and cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C). The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20 mM imidazole, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% IGEPAL, 50 µg/ml benzamidine, 100 units DNaseI, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). His-tagged proteins were purified using affinity chromatography with Ni-NTA resin. The affinity tag was removed by adding 1 mg/ml TEV protease and proteins eluted in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The eluted proteins were further purified using gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex200 column. For ITC experiments, proteins were gel filtered in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 200 mM NaCl. All the mutant proteins were tested for their folding relative to the wild-type protein using circular dichroism (supplementary material Fig. S2).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The affinities of SNX27, SNX27ΔPDZ and SNX27 FERM and various mutants for PtdInsPs were determined using a Microcal iTC200 instrument. Soluble diC8 PtdInsPs were purchased from Echelon Biosciences. Experiments were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl. The PtdInsPs at 0.5 mM were titrated into 0.025 mM proteins in 13× 3.1 µl aliquots at 25°C. Data was processed using ORIGIN to extract the thermodynamic parameters ΔH, Ka (1/Kd) and the stoichiometry n. ΔG and ΔS were derived from the equation ΔG = −RTlnKa and ΔG = ΔH − TΔS.

Homology modeling of the SNX27 FERM domain and in silico docking of phosphoinositides

The SNX17 FERM domain crystal structure (PDB ID 4GXB) (Ghai et al., 2013) was used as the template molecule to generate a homology model of the human SNX27 FERM domain. The FERM domain of SNX27 has 24% sequence identity with SNX17 but the predicted secondary structure is highly similar (Ghai et al., 2011). The SNX27 homology model was built using the SWISS-MODEL server (Arnold et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2009), and was of high quality with a Qmean score of 0.67. Other homology modeling programs produced highly similar structures (data not shown).

The SNX27 FERM-domain–PtdInsP complexes were generated using HADDOCK 2.1 in the CNS suite (Brunger et al., 1998; Dominguez et al., 2003). The SNX27 FERM domain homology model was used as a starting structure. The topology and parameter files of the PtdInsP molecules to be docked [PtdIns(3,5)P2, PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3] were created using the PRODRG server (Schuttelkopf and van Aalten, 2004). Based on the SNX27 sequence, solvent accessibility, and our mutagenesis data, active residues were assigned (Arg435, Arg436, Lys437, Arg490, Arg493, Arg494, Arg496 and Arg499) and the PtdInsP molecules were considered as a single residue. The rigid-body energy minimization protocol generated 1000 solutions initially, out of which the 200 structures with lowest total energy were selected and subjected to simulated semi-flexible annealing. All 200 solutions were refined by an explicit water refinement step, and the final model selected is the average of the 200 models that HADDOCK generates.

Stimulation of Jurkat T-cells with APCs

Jurkat T-cells (human acute T-cell leukaemia cells) in logarithmic growth phase were transfected (1.2×107 cells in 400 µl complete medium) with 20 µg plasmid DNAs by electroporation with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad; 270 V, 975 µF); cells were assayed 24 hours after transfection. Raji B cells (human B cell lymphoma), used as APCs, were stained with 50 mM 7-amino-4-chloromethylcoumarin (CMAC) and were pulsed with 1 µg/ml bacterial superantigen Staphylococcus enterotoxin E (SEE) (Toxin Technology) (Fraser et al., 2000) (1 hour, 37°C). Raji B cells were then washed and then mixed 1∶1 with Jurkat T-cells for the indicated times.

Immunofluorescence microscopy imaging

Immunofluorescence microscopy of HeLa and A431 cells was performed as described previously (Ghai et al., 2011). Briefly, A431 and HeLa cells were transiently transfected with mammalian expression constructs for GFP–SNX27 or its mutants using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated in a blocking buffer of 2% BSA in PBS, pH 7.4. Primary, then secondary antibodies, were diluted in blocking buffer, and the cells were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature. Monolayers were washed with blocking solution followed by PBS, before being mounted and examined using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal fluorescent microscope using a 63× objective. Data were analyzed using Zeiss LSM 5.0 and Adobe Photoshop software.

For imaging of Jurkat T-cells, at 24 hours after transfection, cells were washed and maintained in HEPES-buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; 25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 132 mM NaCl, 0.1% BSA), transferred to chambered coverslips coated with poly-DL-lysine, and allowed to attach for at least 5 minutes at 37°C. For time-lapse fluorescence, microscopy cells were placed on a heated plate, pulsed and stained APCs were added during acquisition. For quantitative analysis and detection of endogenous SNX27 [mouse monoclonal (1C6), Abcam], after incubation of Jurkat T-cells with APCs for the indicated times, cells were fixed for 4 minutes in cold methanol, and coverslips were mounted on glass slides. Cells were imaged on an FV1000 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and images were processed using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). To quantify the amount of GFP–SNX27 constructs accumulated at a region of interest of the T-cell, we used an ImageJ plugin (Rincón et al., 2011) that measures average intensity value of the image in a small circular area; we monitored background (Bg), the cytosol of the T-cell (T), and the ERC (S) when the fluorescent protein was expressed by only one of the two cells. Average pixel value was computed for each measurement (Bg, T, S). From these observed values, we separated the contribution of each component (background, cytosol, and T-cell at ERC). Finally, we computed the ratio between fluorescence at the two regions of interest. Ratio values were represented as dot plots, with each dot representing an individual cell. Pearson's correlation coefficients were also produced with ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

To analyze Pearson's correlation coefficient data for GFP–SNX27 and Tf–Rhodamine, we used a two-way ANOVA test, respectively. Pairs of distribution ratios (S:T) from different GFP–SNX27 constructs were tested by Student's t-tests. We applied a Bonferroni correction to the confidence thresholds to account for the multiple comparisons performed. Both analyses were performed using PRISM software. Differences were considered not significant (ns) when P>0.05, significant (*) when P<0.05, very significant (**) when P<0.01 and extremely significant (***) when P<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Microscopy of HeLa and A431 cells was performed at the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF)/Institute for Molecular Bioscience Dynamic Imaging Facility for Cancer Biology, which was established with the support of the ACRF.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

I.M. and B.M.C. designed research; R.G., M.T.-L, S.J.N, Z.Y. and T.C. performed research; R.G., M.T.-L, I.M., R.D.T. and B.M.C. analyzed data; and R.G., M.T.-L. R.D.T., I.M. and B.C. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the Australian Research Council [grant number DP120103930 to B.M.C. and R.D.T.]; and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia [grant numbers APP1025538, APP1042082, APP1058734 to B.M.C. and R.D.T.]; and grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation [grant number BFU2013-47640 to I.M.], RETIC Cancer Program [grant number RD12/0036/0059 to I.M.], and the Madrid Regional Government (Immunothercam) [grant number S2010/BMD-2326 to I.M.]. B.M.C. was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship Award [grant number FT100100027] and currently holds an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship [grant number APP1061574]. R.D.T. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship [grant number APP1041929]. M.T. receives an FPI fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.158204/-/DC1

References

- Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. (2006). The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22, 195–201 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balana B., Maslennikov I., Kwiatkowski W., Stern K. M., Bahima L., Choe S., Slesinger P. A. (2011). Mechanism underlying selective regulation of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels by the psychostimulant-sensitive sorting nexin 27. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5831–5836 10.1073/pnas.1018645108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balana B., Bahima L., Bodhinathan K., Taura J. J., Taylor N. M., Nettleton M. Y., Ciruela F., Slesinger P. A. (2013). Ras-association domain of sorting Nexin 27 is critical for regulating expression of GIRK potassium channels. PLoS ONE 8, e59800 10.1371/journal.pone.0059800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla T. (2005). Inositol-lipid binding motifs: signal integrators through protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions. J. Cell Sci. 118, 2093–2104 10.1242/jcs.02387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottcher R. T., Stremmel C., Meves A., Meyer H., Widmaier M., Tseng H. Y., Fassler R. (2012). Sorting nexin 17 prevents lysosomal degradation of beta1 integrins by binding to the beta1-integrin tail. Nat. Cell Biol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S. et al. (1998). Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 10.1107/S0907444998003254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L., Loo L. S., Atlashkin V., Hanson B. J., Hong W. (2011). Deficiency of sorting nexin 27 (SNX27) leads to growth retardation and elevated levels of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2C (NR2C). Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1734–1747 10.1128/MCB.01044-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton J. G., Cullen P. J. (2005). Coincidence detection in phosphoinositide signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 540–547 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C., Barber J. D., Barton G. J. (2008). The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W197–W201 10.1093/nar/gkn238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello P. S., Gallagher M., Cantrell D. A. (2002). Sustained and dynamic inositol lipid metabolism inside and outside the immunological synapse. Nat. Immunol. 3, 1082–1089 10.1038/ni848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P. J. (2008). Endosomal sorting and signalling: an emerging role for sorting nexins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 574–582 10.1038/nrm2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das V., Nal B., Dujeancourt A., Thoulouze M. I., Galli T., Roux P., Dautry-Varsat A., Alcover A. (2004). Activation-induced polarized recycling targets T cell antigen receptors to the immunological synapse; involvement of SNARE complexes. Immunity 20, 577–588 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00106-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries S. J., van Dijk M., Bonvin A. M. (2010). The HADDOCK web server for data-driven biomolecular docking. Nat. Protoc. 5, 883–897 10.1038/nprot.2010.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. (2006). Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 443, 651–657 10.1038/nature05185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNitto J. P., Lambright D. G. (2006). Membrane and juxtamembrane targeting by PH and PTB domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 850–867 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez C., Boelens R., Bonvin A. M. (2003). HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 10.1021/ja026939x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenfeldt W. H., Stols L., Millard C. S., Joachimiak A., Donnelly M. I. (2009). A family of LIC vectors for high-throughput cloning and purification of proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology: High-throughput protein expression and purification, vol. 498 Doyle S A, ed105–115Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson K. M., Lemmon M. A., Schlessinger J., Sigler P. B. (1995). Structure of the high affinity complex of inositol trisphosphate with a phospholipase C pleckstrin homology domain. Cell 83, 1037–1046 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90219-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson K. M., Kavran J. M., Sankaran V. G., Fournier E., Isakoff S. J., Skolnik E. Y., Lemmon M. A. (2000). Structural basis for discrimination of 3-phosphoinositides by pleckstrin homology domains. Mol. Cell 6, 373–384 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00037-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finetti F., Baldari C. T. (2013). Compartmentalization of signaling by vesicular trafficking: a shared building design for the immune synapse and the primary cilium. Immunol. Rev. 251, 97–112 10.1111/imr.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J., Arcus V., Kong P., Baker E., Proft T. (2000). Superantigens - powerful modifiers of the immune system. Mol. Med. Today 6, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallon M., Clairfeuille T., Steinberg F., Mas C., Ghai R., Sessions R. B., Teasdale R. D., Collins B. M., Cullen P. J. (2014). A unique PDZ domain and arrestin-like fold interaction reveals mechanistic details of endocytic recycling by SNX27-retromer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E3604–E3613 10.1073/pnas.1410552111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai R., Collins B. M. (2011). PX-FERM proteins: A link between endosomal trafficking and signaling? Small GTPases 2, 259–263 10.4161/sgtp.2.5.17276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai R., Mobli M., Norwood S. J., Bugarcic A., Teasdale R. D., King G. F., Collins B. M. (2011). Phox homology band 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin-like proteins function as molecular scaffolds that interact with cargo receptors and Ras GTPases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7763–7768 10.1073/pnas.1017110108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai R., Bugarcic A., Liu H., Norwood S. J., Skeldal S., Coulson E. J., Li S. S., Teasdale R. D., Collins B. M. (2013). Structural basis for endosomal trafficking of diverse transmembrane cargos by PX-FERM proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E643–E652 10.1073/pnas.1216229110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D. I., Métoz F. (1999). ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada K., Shimizu T., Matsui T., Tsukita S., Hakoshima T. (2000). Structural basis of the membrane-targeting and unmasking mechanisms of the radixin FERM domain. EMBO J. 19, 4449–4462 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriague J., Bismuth G. (2002). Imaging antigen-induced PI3K activation in T cells. Nat. Immunol. 3, 1090–1096 10.1038/ni847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H., Naoi S., Nakagawa T., Nishikawa T., Fukuda H., Imajoh-Ohmi S., Kondo A., Kubo K., Yabuki T., Hattori A. et al. (2012). Sorting nexin 27 interacts with multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4) and mediates internalization of MRP4. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15054–15065 10.1074/jbc.M111.337931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert L., Hanson B., Barthet G., Sebben M., Claeysen S., Hong W., Marin P., Dumuis A., Bockaert J. (2004). New sorting nexin (SNX27) and NHERF specifically interact with the 5-HT4a receptor splice variant: roles in receptor targeting. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5367–5379 10.1242/jcs.01379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F., Arnold K., Künzli M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. (2009). The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D387–D392 10.1093/nar/gkn750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauth P., Schlüter T., Czubayko M., Kirsch C., Florian V., Schreckenberger S., Hahn H., Bohnensack R. (2005). Functions of sorting nexin 17 domains and recognition motif for P-selectin trafficking. J. Mol. Biol. 347, 813–825 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyasu S. (2003). The role of PI3K in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 313–319 10.1038/ni0403-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont V., Astoul E., Laurence A., Liautard J., Cantrell D. (2000). The T cell antigen receptor activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-regulated serine kinases protein kinase B and ribosomal S6 kinase 1. FEBS Lett. 486, 38–42 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02235-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larghi P., Williamson D. J., Carpier J. M., Dogniaux S., Chemin K., Bohineust A., Danglot L., Gaus K., Galli T., Hivroz C. (2013). VAMP7 controls T cell activation by regulating the recruitment and phosphorylation of vesicular Lat at TCR-activation sites. Nat. Immunol. 14, 723–731 10.1038/ni.2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauffer B. E., Melero C., Temkin P., Lei C., Hong W., Kortemme T., von Zastrow M. (2010). SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 190, 565–574 10.1083/jcb.201004060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Floc'h A., Tanaka Y., Bantilan N. S., Voisinne G., Altan-Bonnet G., Fukui Y., Huse M. (2013). Annular PIP3 accumulation controls actin architecture and modulates cytotoxicity at the immunological synapse. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2721–2737 10.1084/jem.20131324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A. (2008). Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 99–111 10.1038/nrm2328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo L. S., Tang N., Al-Haddawi M., Dawe G. S., Hong W. (2014). A role for sorting nexin 27 in AMPA receptor trafficking. Nat. Commun. 5, 3176 10.1038/ncomms4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn M. L., Nassirpour R., Arrabit C., Tan J., McLeod I., Arias C. M., Sawchenko P. E., Yates J. R., 3rd, Slesinger P. A. (2007). A unique sorting nexin regulates trafficking of potassium channels via a PDZ domain interaction. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1249–1259 10.1038/nn1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil A. J., Pohajdak B. (2007). Polarization of endosomal SNX27 in migrating and tumor-engaged natural killer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 146–150 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil A. J., Mansour M., Pohajdak B. (2007). Sorting nexin 27 interacts with the Cytohesin associated scaffolding protein (CASP) in lymphocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 359, 848–853 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas S., Potterton E., Wilson K. S., Noble M. E. (2011). Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 386–394 10.1107/S0907444911007281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski J. T., Gomez T. S., Schoon R. A., Mangalam A. K., Billadeau D. D. (2013). WASH knockout T cells demonstrate defective receptor trafficking, proliferation, and effector function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 958–973 10.1128/MCB.01288-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón E., Santos T., Avila-Flores A., Albar J. P., Lalioti V., Lei C., Hong W., Mérida I. (2007). Proteomics identification of sorting nexin 27 as a diacylglycerol kinase zeta-associated protein: new diacylglycerol kinase roles in endocytic recycling. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1073–1087 10.1074/mcp.M700047-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón E., Sáez de Guinoa J., Gharbi S. I., Sorzano C. O., Carrasco Y. R., Mérida I. (2011). Translocation dynamics of sorting nexin 27 in activated T cells. J. Cell Sci. 124, 776–788 10.1242/jcs.072447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarikangas J., Zhao H., Lappalainen P. (2010). Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton-plasma membrane interplay by phosphoinositides. Physiol. Rev. 90, 259–289 10.1152/physrev.00036.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüttelkopf A. W., van Aalten D. M. (2004). PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1355–1363 10.1107/S0907444904011679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg F., Gallon M., Winfield M., Thomas E., Bell A. J., Heesom K. J., Tavare J. M., Cullen P. J. (2013). A global analysis of SNX27-retromer assembly and cargo specificity reveals a function in glucose and metal ion transport. Nat. Cell Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger W., Sailler B., Strasser V., Recheis B., Fasching D., Kahr L., Schneider W. J., Nimpf J. (2002). The PX-domain protein SNX17 interacts with members of the LDL receptor family and modulates endocytosis of the LDL receptor. EMBO J. 21, 4259–4267 10.1093/emboj/cdf435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolt P. C., Jeon H., Song H. K., Herz J., Eck M. J., Blacklow S. C. (2003). Origins of peptide selectivity and phosphoinositide binding revealed by structures of disabled-1 PTB domain complexes. Structure 11, 569–579 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00068-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale R. D., Collins B. M. (2012). Insights into the PX (phox-homology) domain and SNX (sorting nexin) protein families: structures, functions and roles in disease. Biochem. J. 441, 39–59 10.1042/BJ20111226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin P., Lauffer B., Jäger S., Cimermancic P., Krogan N. J., von Zastrow M. (2011). SNX27 mediates retromer tubule entry and endosome-to-plasma membrane trafficking of signalling receptors. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 715–721 10.1038/ncb2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng H. Y., Thorausch N., Ziegler T., Meves A., Fässler R., Böttcher R. T. (2014). Sorting nexin 31 binds multiple β integrin cytoplasmic domains and regulates β1 integrin surface levels and stability. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 3180–3194 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes J. L., Tang J., McDermott M. I., Kuo J. C., Zimmerman S. P., Wincovitch S. M., Waterman C. M., Milgram S. L., Playford M. P. (2011). Sorting Nexin 27 regulates trafficking of a PAK interacting exchange factor (betaPIX)-G-protein-coupled receptor kinase interacting protein (GIT) complex via a PDZ domain interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39403–39416 10.1074/jbc.M111.260802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck B., Guillermet-Guibert J., Graupera M., Bilanges B. (2010). The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 329–341 10.1038/nrm2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira N., Deng F. M., Liang F. X., Liao Y., Chang J., Zhou G., Zheng W., Simon J. P., Ding M., Wu X. R. et al. (2014). SNX31: a novel sorting nexin associated with the uroplakin-degrading multivesicular bodies in terminally differentiated urothelial cells. PLoS ONE 9, e99644 10.1371/journal.pone.0099644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao Y., Zhang X., Badie H., Zhou Y., Mu Y., Loo L. S., Cai L., Thompson R. C., Yang B. et al. (2013). Loss of sorting nexin 27 contributes to excitatory synaptic dysfunction by modulating glutamate receptor recycling in Down's syndrome. Nat. Med. 19, 473–480 10.1038/nm.3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen P. J., Osborne S. L., Morrow I. C., Parton R. G., Domin J., Meunier F. A. (2008). Ca2+-regulated pool of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate produced by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase C2alpha on neurosecretory vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5593–5603 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne J. P., Wu J., Su W., Mor A., Patsoukis N., Boussiotis V. A., Hubbard S. R., Philips M. R. (2012). Rap1-interacting adapter molecule (RIAM) associates with the plasma membrane via a proximity detector. J. Cell Biol. 199, 317–330 10.1083/jcb.201201157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuseff M. I., Lankar D., Lennon-Duménil A. M. (2009). Dynamics of membrane trafficking downstream of B and T cell receptor engagement: impact on immune synapses. Traffic 10, 629–636 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00913.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. T., Li H., Cheung S. M., Costantini J. L., Hou S., Al-Alwan M., Marshall A. J. (2009). Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-regulated adapters in lymphocyte activation. Immunol. Rev. 232, 255–272 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00838.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.