SUMMARY

Female sex workers (FSWs) bear a disproportionately large burden of HIV infection worldwide. Despite decades of research and programme activity, the epidemiology of HIV and the role that structural determinants have in mitigating or potentiating HIV epidemics and access to care for FSWs is poorly understood. We reviewed available published data for HIV prevalence and incidence, condom use, and structural determinants among this group. Only 87 (43%) of 204 unique studies reviewed explicitly examined structural determinants of HIV. Most studies were from Asia, with few from areas with a heavy burden of HIV such as sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, and eastern Europe. To further explore the potential effect of structural determinants on the course of epidemics, we used a deterministic transmission model to simulate potential HIV infections averted through structural changes in regions with concentrated and generalised epidemics, and high HIV prevalence among FSWs. This modelling suggested that elimination of sexual violence alone could avert 17% of HIV infections in Kenya (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 1–31) and 20% in Canada (95% UI 3–39) through its immediate and sustained effect on non-condom use) among FSWs and their clients in the next decade. In Kenya, scaling up of access to antiretroviral therapy among FSWs and their clients to meet WHO eligibility of a CD4 cell count of less than 500 cells per μL could avert 34% (95% UI 25–42) of infections and even modest coverage of sex worker-led outreach could avert 20% (95% UI 8–36) of infections in the next decade. Decriminalisation of sex work would have the greatest effect on the course of HIV epidemics across all settings, averting 33–46% of HIV infections in the next decade. Multipronged structural and community-led interventions are crucial to increase access to prevention and treatment and to promote human rights for FSWs worldwide.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, sex workers are disproportionately affected by the HIV pandemic.1 The authors of a review of HIV burden in female sex workers (FSWs) in 50 low-income and middle-income countries reported an overall HIV prevalence of 11·8% (95% CI 11·6– 12·0), with a pooled odds of HIV infection of 13·5 (10·0–18·1) compared with the general population of women of reproductive age.2 In many high-income countries and regions, such as Canada, the USA, and Europe, epidemics that initially escalated in people who inject drugs in the mid-1990s shifted to FSWs.3, 4 In settings such as Russia and central and eastern Europe, the scarce data available suggests emerging or established epidemics among FSWs who inject drugs.5, 6 Heterogeneity in HIV prevalence among FSWs varies substantially both across and within regions due to social, political, economic, and cultural factors,7 yet an understanding of how structural factors (eg, contextual factors external to the individual) shape HIV acquisition and transmission risks has only just begun to emerge.

Sex workers—those who exchange sex for money—can be female, male, or transgender. Although most sex workers are female and patronised by male clients (sex buyers), sizeable populations of male and transgender sex workers are present in many settings.8, 9 The work environment and community organisation of sex work varies substantially, including formal sex work establishments (eg, massage parlours, brothels, or other in-call venues (eg, hotels, lodges, and saunas), and outdoor settings (eg, streets, parks, and markets). Sex workers might solicit clients independently, both on-street and off-street (eg, self-advertisement online, in newspapers, or by phone or text), or might work for a manager or pimp. In some cases, sex workers might additionally work cooperatively in microbrothels (two or more sex workers working together).

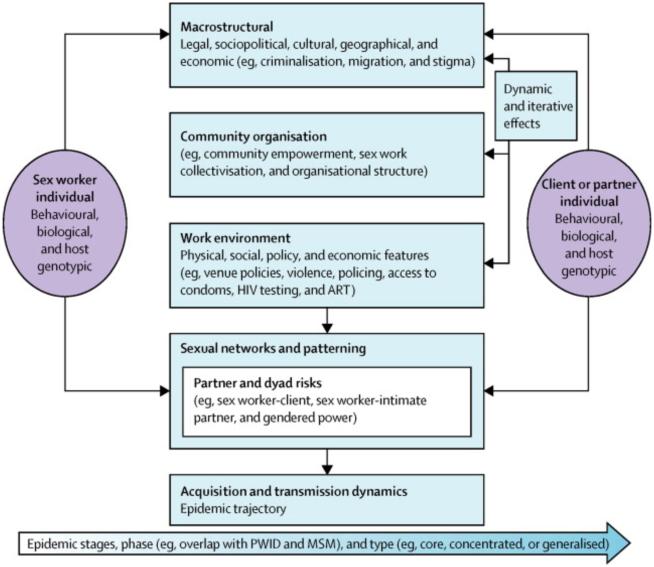

Research and programmes in the past decade suggest that behavioural and biomedical interventions among FSWs alone have had only modest effects on the reduction of HIV at the population-level,2, 10 which has led to calls for combination HIV prevention that includes structural interventions. For example, efforts to roll out antiretroviral therapy (ART) or distribute condoms to FSWs in settings where criminalisation and stigma deter access to condoms or health services continue to hamper HIV prevention, treatment, and care efforts.1, 11, 12 Growing interest has arisen in structural determinants of HIV risk and ecological models that account for these risks among FSWs and other key affected populations (eg, people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men).13, 14, 15 Social epidemiology efforts in sex work have increasingly considered both structure and biology (and behaviour) within a structural determinants framework (figure 1) to better delineate the complex interplay and heterogeneity of HIV acquisition and transmission, and, more aptly, predict epidemic trajectories and intervention targets.13, 16, 17, 18

Figure 1. Structural HIV determinants framework for sex work.

Adapted with permission from Shannon and colleagues.19 ART=antiretroviral therapy. PWID=people who inject drugs. MSM=men who have sex with men.

Despite efforts to consider structural HIV determinants in programmes,16 social science,14, 18 and epidemiological15, 17 literature, the extent to which empirical work characterises the epidemiology of structural factors and HIV among FSWs worldwide, alongside behavioural and biological factors, has yet to be considered. We did a comprehensive search for recent published reports on HIV and FSWs (Jan 1, 2008, to Dec 31, 2013), and assessed the extent to which this literature regarded structural determinants in the mitigation or potentiation of HIV acquisition and transmission risk (panel 1). To further consider key structural factors from our report and available context-specific epidemiological, qualitative, and grey literature, we then modelled potential aversion of HIV infections through structural changes in three cities with high HIV prevalence among FSWs: two low-income and middle-income countries—one concentrated (India) and one generalised (Kenya) epidemic—and one high-income city with overlap with an epidemic of injecting drug use (Canada). These models allowed us to assess heterogeneity of epidemics and key structural determinants, and the potential effect of single and combined interventions (eg, structural changes) in different epidemic contexts.

STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS OF HIV

Systematic review

To consider the centrality of structural determinants in HIV epidemics among FSWs, we mapped present epidemiological reports on a structural determinants framework for HIV and sex work (figure 1).19 Of the 3214 relevant publications retrieved, 149 (73%) of 204 unique studies reported at least one structural determinant (table, appendix), but only 87 (43%) were designed a priori to examine one or more structural determinants of HIV, HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI), or condom use. Of these, 81 (93%) were from low-income and middle-income countries, with most from Asia (35 from India and 13 from China), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (14 studies). Few reports originated from heavy or increasing HIV burden settings of sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, or eastern Europe. Most studies documented associations between structural factors and condom use, rather than HIV (or HIV and STI) infection.

Table.

Structural drivers: mitigating and potentiating of HIV risk among female sex workers, 2008–13

| Association with HIV (or HIV and STI) infection |

Association with non- condom use |

|

|---|---|---|

| Macrostructural | ||

| Laws and policies governing sex work (eg, red-light district demolition due to legal changes and enforcement of criminal sanctions) |

Negative | Positive |

| Regulation of sex workers (eg, mandatory government registration) |

.. | Negative |

| Stigma (eg, sex work-related stigma or discrimination) |

.. | Positive |

| Food insecurity (eg, childhood malnourishment) | .. | Positive |

| Economic insecurity due to restrictive laws or policies for women or sex workers |

.. | Positive |

| Migration and mobility patterns (eg, internal mobility, sex work at religious festivals, international migration, or mobility for sex work) |

Positive or negative | Positive or negative |

| Residential instability (eg, evictions due to policies on sex work or women) |

.. | Positive |

| Geographical district, region, or country of residence (eg, residence in a higher-prevalence district or rural vs urban) |

Positive | Positive or negative |

| Sex trafficking (eg, forced sexual labour) | Positive | Positive |

| Historical gender-based violence (physical or sexual) |

.. | Positive |

| Foster care history | Positive | .. |

| Gender empowerment | .. | Negative |

| Higher education and literacy level | Positive or negative | Negative |

| Community organisation | ||

| Community mobilisation | Negative | Negative |

| Sex work collectivisation (eg, collective agency, social cohesion and mutual aid among sex workers, and collective identity) |

.. | Negative |

| Peer leadership, education, or outreach (eg, frequency of contact with coworkers) |

Negative | Negative |

| Sex work drop-in spaces | Negative | Negative |

| Sex worker advocacy or outreach to police and government (eg, collective action) |

Negative | Negative |

| Other forms of social or community participation (eg, participation in non-sex worker community organisations or social networks) |

.. | Negative |

| Social features of work environment | ||

| Physical and sexual violence (perpetrated by clients, police, managers, and pimps) |

Positive | Positive |

| Local policing practices (eg, displacement, harassment, fines, arrest, incarceration, raids, and confiscation of condoms) |

Positive | Positive |

| Presence of management (eg, manager, pimp, or administrator) |

Positive | Positive |

| Supportive management practices (eg, owner or management support for condom use and HIV and STI prevention, and manager protection) |

.. | Negative |

| Peer norms and support (eg, peer or coworker support for condom use and HIV and STI prevention, and condom use norms) |

.. | Negative |

| Drug and alcohol use in workplace (eg, forced alcohol use or drug or alcohol use during sex with clients) |

Positive | Positive |

| Access to and control over social resources (eg, forms of government identification) |

.. | Negative |

| Physical features of work environment | ||

| Sex work venues | Positive or negative | Positive or negative |

| Access to or coverage of condoms (eg, free or subsidised condoms, condom availability and affordability, and community-level increase in harm reduction supplies) |

Negative | Negative |

| Access to or coverage of HIV care continuum (eg, HIV testing and treatment, and access to HIV- related care and interventions) |

Positive or negative | Negative |

| Access to or coverage of sexual and reproductive health care (eg, STI testing and treatment, and contraceptive use) |

Positive or negative | Positive or negative |

| Policy features of work environment | ||

| Venue-based policies (eg, 100% condom use, other venue condom use rules or policies, and supportive sexual health policies) |

Negative | |

| Economic features of work environment | ||

| Poverty-related and economic pressures (including poor living conditions and homelessness), economic drivers of sex work (eg, children and debt) |

Positive | Positive or negative |

| Economic incentive and client demand for non- condom use |

Positive | Positive |

| Delay or refusal of payment for sex, or property stolen |

.. | Positive |

| Bribes or fines (by police or managers; eg, police accepted bribes or gifts, or sex workers had sex with police to avoid arrest) |

.. | Positive |

| Higher income, prices charged for services, and control over prices charged |

Negative | Positive or negative |

| Other income sources and financial support | Negative | Negative |

| Under contract | .. | Negative |

The appendix lists all published studies retrieved (2008∓13) in the report and references for this table. STI=sexually transmitted infection. ..=variable was not measured in any of the available published data.

Macrostructural factors

Macrostructural factors increasingly play a central part in HIV epidemic structures among FSWs and operate in iterative pathways with other structural determinants and behavioural and biological factors. An increasing number of reports show how punitive laws and policies governing sex work, including criminalisation of some or all aspects of sex work, incarceration, demolition of red-light districts (due to punitive policy changes) and legal restrictions on where sex workers operate, elevate HIV acquisition and transmission risks.23, 24 Criminalisation and punitive policies on sex work have been shown to enact stigma,25, 26 increase food and economic insecurity,27, 28 and residential instability (due to evictions)29 among FSWs, and have been associated with inconsistent condom use. Where FSWs have constrained rights and access to resources due to their status as sex workers and women, gender-based violence26, 30 and sex trafficking (forced sexual labour)28, 30, 31 have been consistently linked to increased odds of HIV infection and condom non-use. By contrast, gender empowerment29 and higher education and literacy29, 32 continue to mitigate HIV risk among FSWs.

Migration and mobility have particularly complex and non-linear effects on HIV risk pathways among FSWs, both mitigating and conferring HIV risk. Internal domestic and circular migration and mobility (eg, intraurban or intradistrict mobility, and short-term travel to sex-work hotspots)33, 34, 35, 36 have been associated with enhanced HIV vulnerability, whereas long durations of mobility and international migration from non-endemic settings have been linked to high rates of condom use37 and low HIV prevalences.38 The complexity of migration and HIV is characterised by other geographical features and epidemic structures (eg, immigration or emigration to higher-prevalence settings and rural vs urban migration) that might confer or mitigate HIV risk among FSWs.

Community organisation

The role of community organisation in the reduction of HIV risk through increased condom use and lower HIV prevalence among FSWs at the population level is increasingly important. The available data for sex worker organisation is largely restricted to India,25, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 where substantial resource investments have been made in community empowerment efforts among sex workers as part of broader HIV prevention efforts. Aside from a few reports from China,32 Kenya,44 and Latin America,45, 46 gaps in data for community empowerment up to now can be attributed in large part to scarcity of resources to assess grassroots sex worker efforts and macrostructural constraints of criminalisation and stigma that restrict the ability of FSWs to organise. Community organisation has been considered both as a broad process or intervention of community empowerment, as exemplified by Songachi and Avahan models in India,25, 39, 47 or as a specific component of community organisation (eg, sex work drop-in spaces or social cohesion). For example, substantial increases in condom use (and decreased STI prevalence) were noted after the Ashodaya sex work collective intervention in Mysore, India, which combined community mobilisation, sex worker-led outreach, sex worker advocacy to police and local government, and improved sexual health services tailored to sex workers.25

Work environment

The work environment consists of intersecting social, physical, policy, and economic features of places within which FSWs work (eg, venues, streets and public spaces, online, and other off-street self-advertising spaces).

The social features of work environments assessed in more than 100 publications are measured as both downstream products of and interactions with macrostructural factors (eg, laws and policies). Within criminalised environments, physical and sexual violence in the workplace, whether by clients, police, managers, pimps, or predators posing as clients, are among the most ubiquitous and influential determinants of HIV acquisition and transmission risk among FSWs, linked to inconsistent condom use, client condom refusal, condom use failure and breakage,22, 24, 26, 28, 33, 43, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 and HIV infection.5, 33, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 In addition to police abuse as a human rights violation, law enforcement strategies and local policing of sex work, including arrests and incarceration,26, 38, 61, 63, 64, 65 raids,64 displacement,24 and confiscation of condoms or syringes,64, 66 are key barriers to HIV prevention efforts among FSWs worldwide, which reduces or eliminates the ability to negotiate male condom use24, 51, 61, 63, 64, 66 and increases HIV prevalence and incidence.38, 65, 66

Physical features of the work environment (eg, venue characteristics or typology) are very context-specific and heterogeneous in structuring of HIV risk patterning in FSWs.23, 24, 34, 37, 41, 55, 57, 63, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 Few investigators have examined the nuanced and intersecting influence of policy, social, and physical features of the work environment in the mitigation or conferment of HIV risk among FSWs. The authors of these studies examined how supportive venue-based policies30, 32, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81 or managerial practices (eg, client sign-in, safety mechanisms, or removal of violent clients)48, 69, 76, 77, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 and physical features (eg, types or layout of venues) of sex work establishments are associated with increased condom use, often through synergistic effects with other social features of increased peer or sex worker support.32, 52, 53, 69, 72, 76, 79, 81, 83, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 Work environments for FSWs are shaped by economic features (eg, economic pressures, client financial incentives for non-condom use, refusal of payment, and bribes or fines by state agents [eg, police] to avoid arrest) resulting from macrostructural forces of poverty, laws, and access to resources and are associated with non-condom use27, 28, 29, 30, 40, 41, 48, 64, 70, 83, 84, 87, 91, 92, 93 and HIV infection among FSWs.36, 65, 75, 94 Conversely, higher income and absence of economic dependence among FSWs mitigate HIV risks, including increased condom use40, 48, 80, 86, 87 and lower HIV prevalence.43, 71, 73, 74, 81, 94

Suboptimum access to safe and appropriate condoms, sexual health care, HIV testing, and ART remain major shortfalls in the fight against the worldwide HIV epidemic among FSWs. Where FSWs report adequate access to condoms, sexual health care (eg, STI testing and contraceptives) and HIV care (eg, HIV testing, ART, and sex worker-tailored clinics), increases are noted in condom use and reduced condom breakage,39, 40, 32, 44, 47, 67, 79, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99 and lower HIV prevalence.100, 101 Condom coverage must include condom access (eg, free or subsidised condoms at the workplace, the ability to carry condoms while working, and contact with peer condom distribution), availability and affordability, linked to reduced HIV acquisition and transmission among FSWs.25, 30, 39, 40, 44, 47, 68, 70, 79, 82, 84, 87, 93, 95, 97, 98, 99, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107

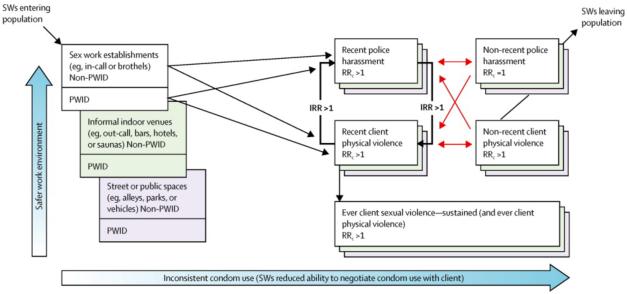

MODELLING HIV EPIDEMICS IN FEMALE SEX WORK

We assessed the population-level effect of some of the structural drivers with deterministic transmission dynamic models to simulate the course of HIV epidemics and potential HIV infections averted through structural changes in regions with concentrated and generalised epidemics and high HIV prevalence among FSWs (appendix). Guided by our systematic review and context-specific epidemiological, qualitative, and grey literature, our modelling considers exposures to context-specific structural factors, which reflects the heterogeneity of epidemic structures in female sex work across settings. Our modelling elucidates the associations between key macrostructural factors (eg, law or policy changes), community organisation (eg, sex worker collectives or sex worker-led outreach), and intersecting social, physical, and policy features of the work environment (eg, safe vs unsafe work environments, time-varying exposure to police harassment, physical and sexual violence, and scale-up of ART coverage). These factors are associated with different partner or dyad HIV risks (eg, condom use, client condom refusal, and number of clients) and individual behavioural (eg, duration of sex work or alcohol or injection use) and biological (eg, STI co-infection rates) factors in each setting (figure 2, appendix). Our modelling, which focuses on sexual transmission, also factors in HIV infection from unsafe syringe sharing (Canada) and increased sexual risks through binge alcohol use (Kenya). We assumed that FSWs can be repeatedly exposed to violence and police harassment at rates that are specific to each setting and work environment, and that the structural factors confer or mitigate HIV risk through their potential effect on condom use in the short and long term. The model accounts for changes in coverage and ART eligibility criteria108 and the documented increases in condom use over time for each setting (appendix). We explored the potential effect of scaling up of ART coverage to meet the WHO guidelines of offering ART at a CD4 cell count of less than 500 cells per μL for FSWs alone and for both FSWs and their clients. We calibrated the models and analysed them within a Bayesian framework with available data to define plausible uniform ranges around model parameters.109 We used many sets of fitting parameters to reproduce the reported HIV prevalence in each setting to predict the effect of single and combined structural changes on the course of HIV epidemics from 2014 to 2021, through both immediate and sustained effect on condom use.

Figure 2. Model of dynamic pathways between macrostructural (eg, law reforms) and social, policy, and physical features of the work environment (eg, access to safer work venues, violence, and policing) on HIV acquisition in female sex workers in Vancouver, Canada.

The flowchart represents the dynamic and iterative pathways between various structural conditions (eg, recent or non-recent exposure to police harassment or client physical violence, or a lifetime exposure to sexual violence), which vary by work environment (represented by the coloured boxes). Female sex workers (FSWs; PWID or non-PWID) are assumed to work in a given work environment for their lifetime. FSWs on the far left have not experienced any violence yet. FSWs can be repeatedly exposed to different violence events at a frequency specific to their work environment; orange arrows show the flow of FSWs between recent and non-recent exposure to violence. IRR >1 shows the increase in the rate of exposure to recent police harassment if recently exposed to client physical violence or vice versa (bold arrows). RRc >1 denotes the increased risk of inconsistent condom use after a recent or non-recent exposure to the given form of violence or police harassment for the duration that they have been in that situation. PWID=people who inject drugs. IRR=incident rate ratio. RRc=inconsistent condom use risk ratio. SW=sex worker.

DIVERSITY AND CONTEXT

Case 1: Vancouver, Canada

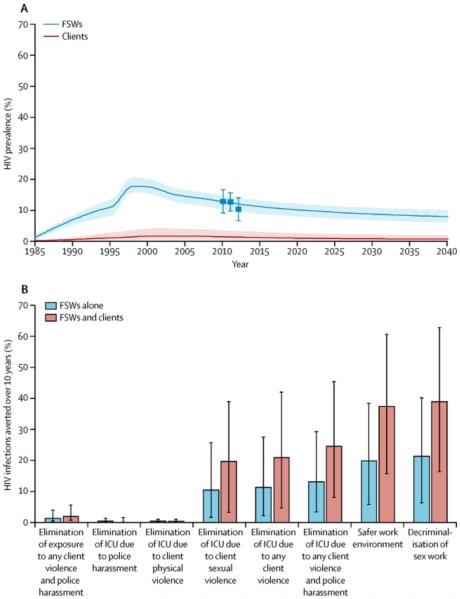

Vancouver provides a key example of a concentrated, high-prevalence epidemic among key populations. As elsewhere in North America, the epidemic in Vancouver first emerged in men who have sex with men in the 1980s.110 By the mid-1990s, an explosive HIV outbreak occurred in people who inject drugs, with HIV incidence peaking at around 18 cases per 100 person-years in 1996 and 1997,111 declining to fewer than three per 100 person-years in 2007 because of substantially improved coverage of syringe distribution, other harm reduction, and ART.112 The epidemic among street FSWs emerged alongside the epidemic among people who inject drugs, partly due to overlap between drug-using FSWs, clients, and non-paying partners.113, 114 Because HIV incidence due to syringe sharing declined substantially, a temporal shift has occurred from illicit drug injection-acquired to sexually transmitted HIV infections in people who inject drugs and FSWs in the past 10 years.115, 116 Alongside the HIV epidemic and decline of HIV within people who inject drugs, STI epidemics have continued to escalate, suggesting that sexual risks precipitate HIV transmission in key populations.116 Data for non-injecting FSWs previous to 2010 are scarce. Nevertheless, modelling suggests that overall HIV prevalence in FSWs might have peaked at around 18% in 2000 and declined to 12% in 2011 (figure 3), and that HIV transmission after 2002 seems to be due predominantly to sexual transmission and, to a lesser extent, unsafe injection practices. Many infections have been averted with increased access to the HIV care continuum (eg, HIV testing and ART) through government-sponsored treatment as prevention efforts, although suboptimal access still remains among women and other subpopulations of indigenous and migrant FSWs (Deering et al, unpublished).117

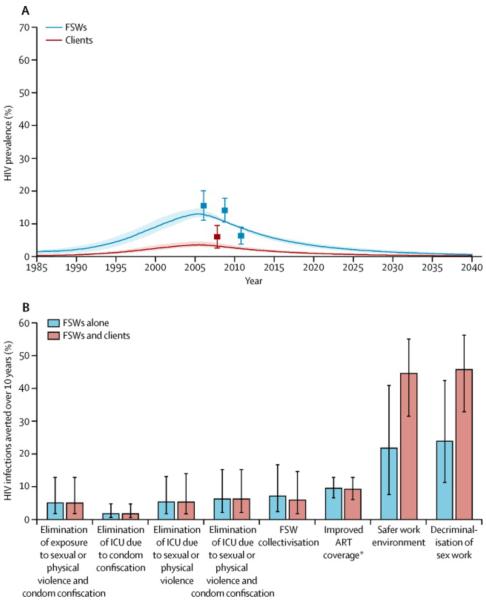

Figure 3. HIV prevalence and percentage of infections potentially averted in FSWs and their clients in the next 10 years through structural changes in Vancouver, Canada.

(A) Predicted HIV prevalence in FSWs between 1985 and 2040. Squares show the empirical estimates (and 95% CIs) from the data; bold line shows the median (shaded area shows 95% CI) of the model predictions from the multivariate parameter fits. (B) Predicted fractions of new HIV infections that could be averted in FSWs and their clients from structural changes in 2014–24; vertical bars show 95% uncertainty intervals. Elimination of exposure means no future exposure to this form of violence. Elimination of ICU means an immediate and lasting reduction of ICU associated with past exposure to the form of violence. The values used to construct the graphs and data for HIV prevalence and infections averted assuming no structural changes are made can be found in the appendix. FSW=female sex worker. ICU=inconsistent condom use.

Work environments in Canada

Patterns of HIV prevalence in FSWs are very heterogeneous by work environment exposures. In Vancouver, estimates put HIV prevalence at 20% in FSWs working in informal indoor venues (eg, bars or hotels), 12% on the street, and 3% in formal sex work establishments (eg, in-call venues).118 Because work environments represent a dynamic interplay of changing structural conditions (eg, legal changes and police crackdowns), historical exposure to street-based sex work114 could remain important to understand the epidemic structure among FSWs in concentrated epidemics.

Despite the criminalised nature of sex work in Canada, in-call venues have existed for a long time in the form of licensed brothels (ie, massage parlours and health enhancement centres) and microbrothels. As described by FSWs (panel 2), efforts have been made to implement new models of safer indoor work spaces within women-only, low-income housing (eg, with supportive management policies and safety measures onsite).123 Longitudinal data suggests that working in formal or in-call sex work establishments reduces rates of non-condom use118 and STIs124 compared with street and informal indoor venues. Modelling predicts that interventions to promote access to safer work environments for FSWs could avert 37% (95% UI 16–61) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients in Vancouver in the next decade through the combined effect on reduced violence, police harassment, and non-condom use (figure 3).

Criminalisation, policing, and violence in Canada

Within a criminalised environment, workplace sexual violence is very prevalent and seems to have a sustained negative effect on condom use (Figure 2 and Figure 3). 30% of FSWs have experienced police harassment or workplace violence in formal indoor establishments compared with 70% in informal indoor or outdoor venues.118 The elimination of future exposure to sexual violence might only have a small effect (2% [95% UI 1–4] in 10 years) in view of the sustained negative effects on condom use negotiation. However, if support and resources were in place to address both immediate and sustained effects of historical sexual violence among FSWs (eg, peer support, counselling, and housing) on non-condom use, the elimination of client sexual violence alone could avert 20% (95% UI 3–39) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next decade in Vancouver (figure 3).

As described by sex workers (panel 2), police harassment (without arrest) can directly influence HIV acquisition risk by forcing FSWs to rush transactions with their clients, forgo condoms, or engage in risky sexual practices, or by displacement of FSWs to isolated or hidden venues, where they have less ability to control transactions (eg, client selection, types of sexual acts, or condom use).120 Police harassment without arrest (eg, raids, forced detainment, or coercion) is very prevalent in Vancouver—62% of FSWs report ever experiencing police harassment in their lifetimes and 40% do so within the past 6 months. Recent exposure to police harassment is estimated to increase the rate of client violence by 1·0–5·2 times125 due to reduced ability to screen clients and displacement to more isolated and hidden venues, thereby increasing FSWs' risk of HIV acquisition (figure 2). Police harassment and physical violence alone have an immediate and transient effect on the reduction of condom use after a recent exposure to the violence, whereas sexual violence seems to negatively affect condom use in the short and long term (figure 2). Because of the dynamic and iterative effects of violence and policing, the independent addressing of police harassment or physical violence alone would have a negligible effect. However, elimination of both police harassment and sexual and physical violence coupled with support to address long-term effects of violence could avert 24% (95% UI 8–45) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients in Vancouver in the next decade (figure 3) through its direct and sustained effect on condom use.

In Canada, a Supreme Court decision to strike down criminal laws targeting sex work has allowed the government to potentially decriminalise sex work by the end of 2014, providing a unique opportunity to model the potential effect of law reforms on the HIV epidemic. Our modelling suggests that nearly 39% (95% UI 16–63) of infections could be averted among FSWs and their clients in the next decade by decriminalisation of sex work (figure 3) through immediate and sustained effects on violence, police harassment, and safe work environments, and associated condom use. These predictions represent the maximum effect that interventions reducing violence or police harassment or legislation can have because the complete elimination of violence or stigma could be challenging.

Case 2: Mombasa, Kenya

Kenya has a generalised epidemic of HIV, with prevalence remaining about 6–7% since 2007.126 FSWs have the highest HIV burden in Kenya, with an explosive HIV epidemic emerging in the 1980s among FSWs, peaking at 80% in 1983.127 HIV incidence declined substantially after the scale-up of HIV prevention and treatment for FSWs in Nairobi from an estimated 18 cases per 100 person-years in 1985 to fewer than five cases per 100 person-years in 2005.127 Estimates suggest that 29·3–47·0% of all Kenyan FSWs are living with HIV.44, 127, 128 Continued high HIV burden among FSWs and absence of sustained coverage of HIV prevention and care services tailored to FSWs is largely attributed to a dearth of strategies to mitigate structural determinants of HIV (eg, stigma, discrimination, violence, and criminalisation).128

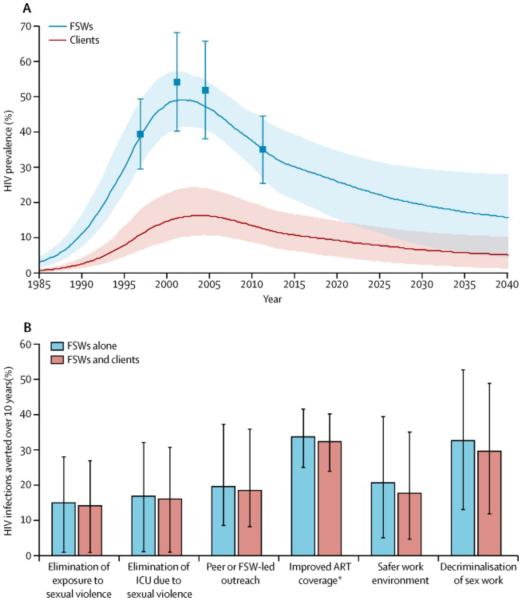

Mombasa is an economic centre of Kenya's Coast Province, with important tourism, port, rail, and industrial enterprises serving as a client base, and a large FSW population (appendix). An estimated 6% of the female population in Mombasa engaged in sex work in the past 12 months.44 Modelling results show that with increased condom use, HIV prevalence (and incidence) among Mombasa FSWs declined from roughly 50% (18 cases per 100 person-years) in the mid-1990s to less than 30% (fewer than five cases per 100 person-years) in 2010–15 (figure 4).44, 129

Figure 4. HIV prevalence and percentage of infections potentially averted in FSWs and their clients in the next 10 years through structural changes in Mombasa, Kenya.

(A) Predicted HIV prevalence in FSWs between 1985 and 2040. Squares show the empirical estimates (and 95% CIs) from the data; bold line shows the median (shaded area shows 95% CI) of the model predictions from the multivariate parameter fits. (B) Predicted fractions of new HIV infections that could be averted in FSWs and their clients from structural changes in 2014–24; vertical bars show 95% uncertainty intervals. Elimination of exposure means no future exposure to this form of violence. Elimination of ICU means an immediate and lasting reduction of ICU associated with past exposure to the form of violence. FSW=female sex worker. ICU=inconsistent condom use. ART=antiretroviral therapy. *Increase in CD4 eligibility according to WHO guidelines to less than 500 cells per μL. The values used to construct the graphs and data for HIV prevalence and infections averted assuming no structural changes are made can be found in the appendix.

Since 2006, ART has been provided to individuals with HIV for free in Kenya. Despite high coverage in the general Kenyan population (estimated at 83% of ART-eligible people in 2011; ie, roughly 40% of all HIV-positive people),126 about 20–30% of all HIV-positive FSWs were reportedly receiving ART based on a CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells per μL.130 Once on ART, much the same rates of retention and virological suppression were reported among FSWs compared with the general population of women, highlighting existing gaps in HIV testing and access to and initiation of ART. As described by sex workers (panel 2), denial of health care access, including ART refusal, is a major structural barrier to HIV prevention and care among FSWs in Kenya, as elsewhere in East Africa, and is associated with heavy criminalisation, stigma, and violence.12 Scale-up of ART access to meet WHO guidelines of a CD4 cell count of less than 500 cells per μL for FSWs would have substantial effect (appendix), with the largest gains on the epidemic seen in ART scale-up for both FSWs and their clients, averting 34% (95% UI 25–42) of HIV infections over the next decade (figure 4), although evidence suggests that removal of structural barriers, including law reform and stigma, remain crucial.1, 12 In addition to the critical need for ART access for FSWs, the ART prevention capacity, particularly in generalised epidemics, of infection avoidance among FSWs by enhanced ART coverage for clients remains pivotal.

Criminalisation and client, police, and stranger sexual violence in Kenya

Sex work is criminalised by both national laws and municipal bylaws in Kenya, with sex worker arrests for loitering for the purpose of selling sex, importuning, and indecent exposure, rather than for clients. Kenyan sex workers describe similar experiences to Vancouver—of how criminalisation compromises HIV prevention by rushed transactions due to fear of arrest, bribes, extortion, sexual coercion, and the forgoing of condoms, and the deterrence of sex workers from reporting violence to authorities (panel 2).122

Sexual violence against FSWs by police, clients, or strangers is endemic in Kenya, with estimates in Mombasa ranging from 29% to 32% in 2007.129 Sexual violence is precipitated by macrostructural determinants, including stigma, criminalisation, and gendered cultural norms (panel 2).44, 129 Modelling suggests that elimination of sexual violence could avert 17% (95% UI 1–31) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next 10 years, coupled with support to address long-term effects of historical sexual violence, due to its immediate and sustained effect on non-condom use (figure 4, appendix).

Work environments in Kenya

Sex work in Mombasa is most common within entertainment establishments (72% in bars or nightclubs), followed by homes (21%) and the street (7%).44 Sparse data exists for features of the work environment, although binge alcohol use is widespread in bars and associated with a reduced ability among FSWs to negotiate client condom use and condom breakage, heightened sexual violence, and HIV infection.129 Substance use in the coastal province is common, with 33% of FSWs estimated to binge drink and most (80%) reporting exchanging sex while intoxicated, with increasing use of khat (77%; amphetamine derivatives), heroin, cocaine, and glue (6%).129, 131 No data for client substance use patterns exist, although estimates among the general male population in Mombasa are similar to that of FSWs.129, 131 Nightclub-based FSWs (who report the most binge drinking) are younger, earn more, and use condoms the most compared with bar or lodge-based FSWs, who charge less and use condoms less frequently, showing the influence of social and physical features of bar venues.129 Modelling suggests that 21% (95% UI 5–35) of HIV infections of FSWs and their clients could be averted through safer work environments over 10 years (figure 4) through combined elimination of increased sexual violence and non-condom use risks associated with binge drinking. Interventions that moderate the work environment (eg, supportive management and venue-based policies, and peer harm reduction) remain pivotal.

Peer and sex worker-led interventions in Kenya

Mapping estimates suggest that large gaps exist in condom access for FSWs, with an estimated 25% of bars with condom dispensers and 29% accessed by peer outreach.105, 132 Sex worker-led outreach can promote consistent condom use directly through enhanced condom coverage in venues and indirectly through peer education around condom negotiation with clients and shifting sex industry norms on condom use.32, 69, 72, 76, 79, 81, 83, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 Sex worker-led interventions are a key component of community empowerment, as shown in several low-income and middle-income countries. In Mombasa, peer or sex worker-led outreach implemented between 2000 and 2005 was associated with a more than three-fold increase in consistent condom use,44 although coverage was less than 30%. Human rights violations and harassment of outreach workers have been reported in Mombasa, which could deter scale up in the absence of structural change (panel 2).119 Scaling up of sex worker-led outreach to even modest coverage could prevent 20% (95% UI 8–36) of HIV infections in the next 10 years (figure 4). Combined structural changes to decriminalise sex work could avert 33% (95% UI 13–53) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next 10 years through a combined effect on sexual violence, safer work environments, and increased condom use (figure 4).

Case 3: Bellary, India

South India is experiencing a predominately heterosexual HIV epidemic among FSWs.133 Although national adult HIV prevalence is less than 1%, India has the largest burden of HIV after South Africa and Nigeria, with an estimated 2·5 million people living with HIV. In the past decade, India has seen substantial progress in the curbing of HIV prevalence among FSWs, although substantial heterogeneity exists. FSWs remain 54-times more likely to be infected with HIV over their lifetime compared with the general population of women of reproductive age.2

In response to a growing HIV epidemic among FSWs in 2003 in Karnataka and other high-prevalence states, the Bill & Melinda Gates's Avahan, Indian AIDS initiative rapidly scaled up HIV prevention efforts. By 2008, more than 75% of the estimated target population (217 000 FSWs) in the 69 Avahan districts across four southern states were being contacted monthly.134

Karnataka (population ~54 million) ranks in the top four Indian states for HIV epidemic severity. Bellary, a high-prevalence district (overall HIV prevalence of 1·2% in 2011) in central Karnataka has a predominately urban epidemic (population of Bellary ~2 million), concentrated among FSWs and men who have sex with men.96 Work environments vary substantially between districts, with home or independent-based and street-based sex work, and to a lesser extent, brothel-based work, with an increased use of phone or text communications and mobility.49 As in Mombasa, industries (mining and chalking) in urban Bellary provide a large client base. Avahan was initiated in Bellary in 2004 and substantial progress has been made (a reduction in HIV prevalence from 15·7% in 2005 to 6·4% in 2011; figure 5).71

Figure 5. HIV prevalence and percentage of infections potentially averted in female sex workers (FSWs) and their clients in the next 10 years through structural changes in Bellary, India.

(A) Predicted HIV prevalence in FSWs between 1985 and 2040. Squares show the empirical estimates (and 95% CIs) from the data; bold line shows the median (shaded area shows 95% CI) of the model predictions from the multivariate parameter fits. (B) Predicted fractions of new HIV infections that could be averted in FSWs and their clients from structural changes in 2014– 24; vertical bars show 95% uncertainty intervals. Elimination of exposure means no future exposure to this form of violence. Elimination of ICU means an immediate and lasting reduction of ICU associated with past exposure to the form of violence. *Increase in CD4 eligibility according to WHO guidelines to less than 500 cells per μL. The values used to construct the graphs and data for HIV prevalence and infections averted assuming no structural changes are made can be found in the appendix. FSW=female sex worker. ICU=inconsistent condom use. ART=antiretroviral therapy.

Alongside Avahan, a slower rollout of ART across India began in 2004, with eligibility criteria shifting from a CD4 cell count of up to 250–350 cells per μL in 2012 to meet international guidelines.135 By 2012, 19% of the 2·3 million adults with HIV in India were estimated to be on ART, with much variability in coverage.136 However, because referral for semi-annual HIV screening among FSWs is a key component of India's targeted intervention programme,137 HIV screening among FSWs is higher than it is for the overall population, although linkage to and retention of ART could be lower.137

Criminalisation, violence, and policing in India

Although buying or selling of sex is not illegal in India, the Indian Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, enacted in 1956, criminalises most aspects of sex work, including solicitation and living off the avails by third parties. Violence is common, although in Karnataka, structural and sex worker-led interventions (policy level, police or stakeholder engagement, and training) have reduced violence against FSWs.22, 25 Prevalence of recent client physical and sexual violence in Bellary reduced from 35% to 9% between 2006 and 2008.22, 33 Elimination of sexual and physical violence could avert a further 5% (95% UI 2–14) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next 10 years through its immediate effect on condom use (figure 5). Fear of condom confiscation due to recent arrest or intimidation is common and associated with a transient increased risk of non-condom use.7, 119 Based on the large-scale reductions in violence already reported because of structural and sex worker-led efforts, elimination of both police condom confiscation and physical and sexual violence through their immediate and sustained effect on condom use could avert 6% (95% UI 2–15) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next decade (figure 5). However, decriminalisation of sex work would have the largest effect: it would avert 46% (95% UI 33–56) of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next decade (figure 5) through its immediate and sustained effect on violence, policing, and safer work environments.

Community empowerment in India

After the Sonagachi model in Kolkata,138 the Avahan intervention in Karnataka and other states included structural and community empowerment components to address both macrostructural (eg, stigma) and work environment (eg, violence) determinants of HIV. Ashodaya, the first of the Avahan interventions, is now regarded as best practice.25, 121 Avahan assessments suggest that the combined multicomponent structural and community empowerment intervention could have averted 33–62% of all infections in FSWs and 39–66% of all infections in clients within 5 years in Bellary97 through membership in sex work collectives, access to STI clinics and peer-led outreach, 24 h crisis lines and drop-in centres, and sex worker advocacy efforts directed towards local government and police (table).21

POLICY AND PREVENTION IMPLICATIONS

In our report, fewer than half the recent epidemiological studies on HIV acquisition and transmission risk among FSWs explicitly considered structural determinants, yet the literature underscores the centrality of structural determinants for this component of the worldwide HIV epidemic. Because sub-Saharan Africa has a substantial portion of the HIV epidemic among FSWs, and Russia and eastern Europe have growing (and in some cases rapidly expanding) HIV epidemics among FSWs, gaps in data for individual and structural determinants of HIV in these regions is concerning.

Our findings show the challenges in the prevention of HIV infections through structural factors that interact in many dynamic pathways (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 4). Science needs to move beyond binary and linear models to more complex, multilevel, and multimethod approaches that consider theoretical and structural contributions to HIV risk—alongside interpersonal, behavioural, and biological contributions—among FSWs to inform HIV prevention. Dialogue across social science and epidemiological research is needed. Several macrostructural features, including stigma,25, 26 mobility, and migration33, 34, 35, 36, 54, 68, 72, 139 are difficult to measure and require complex and dynamic methods to better delineate their role in the conferring or potentiating of HIV risk.

In two settings with severe epidemics of sexual violence (Canada and Kenya), the reduction or elimination of sexual violence and its short-term and long-term negative results could substantially avert HIV infections in the next 10 years. In Mombasa, sexual violence by clients, police, and strangers affected a third of FSWs, suggesting a crucial need for structural changes at the macro level (eg, laws, policies, and stigma) and in the work environments they engender. Safe work environments need to be promoted, with supportive managerial practices and venue-based policies shown to reduce inconsistent condom use and HIV incidence,30, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80 including harm reduction policies to reduce alcohol binge use within entertainment establishments.69

In Vancouver, which has piloted some innovative venue-based models of safe work environments with supportive management policies and practices,123 full access to safer work environments could avert up to 37% of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients (figure 3), although scale-up and coverage is probably only feasible alongside macropolicy support. Furthermore, researchers have shown that even in criminalised contexts, FSWs' engagement of police and other stakeholders (eg, managers, business owners, or government officials) can change work environments by the reduction or elimination of stigma, violence, and police harassment, and increase engagement in care.22, 25, 49

Across both concentrated (India and Canada) and generalised (Kenya) epidemics, decriminalisation of sex work could have the largest effect on the course of the HIV epidemics, averting 33–46% of HIV infections over the next decade. Calls for removal of all legal restrictions targeting sex work have been supported by international policy bodies, including WHO, UNAIDS, UNDP, and the UN Population Fund,1 and a recent unanimous decision by the Supreme Court of Canada. Ultimately, evidence must drive government responses in law and policy revisions to ensure the health and human rights of sex workers.

In India, where the effect of structural interventions and community empowerment efforts (eg, Avahan) on the HIV epidemic has been well documented, further sex worker collectivisation could avert 6% (95% UI 4–14) of new infections in FSWs and their clients within 10 years (figure 5). Although this gain is modest, 25–35% of HIV infections have already been averted through combined structural and community empowerment efforts over the course of Avahan.97 By contrast, in Kenya, where structural constraints (eg, criminalisation, stigma, and gender inequities) have restricted the ability of FSWs to organise,44, 119, 122 even modest coverage of sex worker-led outreach could avert 20% (95% UI 8–36) of HIV infections in the next decade (figure 4).

Our review and modelling underscore the need for multicomponent and multipronged HIV prevention efforts that promote structural changes to ensure improved access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care. Based on the well-established role of ART for prevention, modelling data suggest that scale-up of ART coverage to meet WHO guidelines of a CD4 cell count of less than 500 cells per μL can make substantial gains in the reduction of morbidity and mortality, and a population-level effect on acquisition and transmission for FSWs and their clients. The largest gains are to be had in generalised epidemic settings; in Mombasa, Kenya, ART coverage for both clients and FSWs could avert 34% of infections in the next decade (figure 4). The full effect of ART scale-up will probably only be possible alongside structural changes to address macrodeterminants, community organisation, and work environment factors that influence FSWs' abilities to engage in the HIV continuum of care (eg, voluntary testing and linkage to and retention of care).

Similarly, we noted that condom access (not just coverage) is a key issue, including availability of free or subsidised condoms in the workplace, the ability to carry condoms, and access to sex worker outreach distribution.25, 30, 39, 40, 44, 47, 68, 70, 79, 82, 84, 87, 93, 95, 97, 98, 99, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 In Kenya, where condoms are available in less than a third of bars and lodges,105 sex worker-led outreach models are critical, alongside supportive venue-based policies on and practices in condom use.

Finally, because little research has assessed HIV epidemic responses and the potentially substantial role of addressing HIV among FSWs and their clients (and other key populations) in generalised HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, our findings support the role of structural responses to sex work in the alteration of the course of HIV epidemics.

CONCLUSION

Macrostructural changes are urgently needed to laws and policies (eg, decriminalisation of sex work) and the work environment features (eg, reductions to policing and violence and safer work environments) they engender in order to stem HIV epidemics among FSWs and their clients across diverse epidemic settings. Coverage and equitable access to condoms, ART, and HIV prevention, treatment, and care lag unacceptably behind that of the general population. To generate substantial change among FSWs, scale-up needs to coincide with structural changes, sex worker-led interventions, and engagement through community empowerment. Further data for the many dynamic feedback loops between macrostructural, community organisation-related, and intersecting physical, social, economic, and policy features of work environments within the sex industry are very context specific and necessary to inform policy and programmatic changes. Our findings confirm calls for multipronged structural and community-led interventions, alongside biomedical interventions, that substantially reduce HIV burden and promote human rights for sex workers worldwide.1

PANEL 1. SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND MODELLING: MEASUREMENT OF STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS OF HIV

Systematic review and modelling

The role that structural determinants have in HIV epidemics and access to care for female sex workers (FSWs) is poorly understood. We aimed to review available published data for HIV prevalence and incidence, condom use, and structural determinants among this group through a systematic search of published sources. We extracted details regarding study information (year, setting, study dates, and participants); study design (sample size, geographical location, type of study [longitudinal or cross-sectional], and whether pathways were explored through interaction or stratified analyses); specific outcomes of interest (HIV infection, HIV or sexually transmitted disease infection, or condom use); individual behavioural or biological partner or dyad factors, or structural factors (risks or protective). We recorded whether or not each study had aimed, a priori, to measure and analyse structural determinants of HIV. We then modelled key structural drivers from the systematic review to assess the population-level effect of structural changes using deterministic transmission dynamic models to simulate the course of HIV epidemics and potential HIV infections averted in regions with concentrated and generalised epidemics, and high HIV prevalence among FSWs (Canada, Kenya, and India). Full details of the search and modelling are presented in the appendix.

Structural determinants

To identify structural determinants, we mapped present epidemiological reports on a structural determinants framework for HIV and sex work19 (figure 1, table), and drew on earlier work by Diez Roux and Aiello17, Blanchard and Aral16, Rhodes and colleagues18, Overs20, Strathdee13, and others. Structural determinants (risk or protective factors) operate at macrostructural (eg, social, economic, and health-related policies governing sex work; mobility and migration of sex workers and their clients; geography and sociopolitical transitions; and stigma and cultural norms), community organisation (eg, community empowerment, sex work collectivisation, or leadership), and work environment (eg, physical, social, policy, and economic features, such as venue-based policies, violence, policing, and managerial practices) levels. These various structural determinants can act iteratively and dynamically with interpersonal (eg, partner or dyad factors, such as condom use, types of sexual exchanges, and sexual networks), individual behavioural (eg, drug use or duration in sex work), and biological (eg, sexually transmitted disease co-infection) factors to confer or mitigate HIV acquisition and transmission risk among FSWs.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies that examine multivariate risk or mitigating factors for HIV infection (or HIV or sexually transmitted infections) or (male) condom use among FSWs. We excluded studies that focused solely on adolescent (<18 years), transgender, or male sex workers, or transactional sex (exchange of sex for non-monetary goods). We excluded qualitative studies, non-primary research (eg, reviews, modelling studies, and commentaries), studies in which HIV infection, HIV or sexually transmitted infection, or condom use were not analysed as individual outcomes, studies that did not report multivariate analyses of the outcome, and those that did not report stratified results among FSWs.

Epidemiological data gaps, biases, and contexts

Our systematic review of available epidemiological literature (appendix) does not account for the vast empirical and theoretical social science and grey literature on factors that mitigate or potentiate epidemics among FSWs. Structural determinants that have not been well operationalised, such as stigma, support the increasing need for dialogue between epidemiologists, social scientists, and the community to ensure the diversity of the sex industry and FSWs' lived experiences are shown. Despite efforts to review non-English language reports in Russia, China, Kenya, and India, other countries are not represented here.

Both the available evidence and our modelling of key structural factors identified elucidate the heterogeneous nature of epidemics among FSWs, including the dynamic interplay of structural, behavioural, and biomedical factors that are context specific and modified by variations in epidemic structure (eg, concentrated or generalised; Figure 1 and Figure 2). As such, scarce or unavailable data (including longitudinal, qualitative, and grey literature) on key structural determinants parameters (eg, policing exposures in Kenya and India) and their evolution over time hindered our ability to consider some key contextual elements in the modelling of epidemic trajectories, which led to a potential underestimation of their effect on HIV risk structuring among FSWs. Of particular importance is the concerning dearth of epidemiological, qualitative, and grey literature on structural determinants of HIV among FSWs in high-burden countries of sub-Saharan Africa, given that this region has a substantial portion of the epidemic among FSWs worldwide. In addition, most of the available data are drawn from cross-sectional studies. In our modelling analysis, we show many different influences of structural determinants through recurrent dynamic stages and we highlight the gaps in epidemiological data on non-linear, dynamic, and iterative HIV transmission pathways, and the need for more complex, multilevel, and mixed methods studies. For example, data for Vancouver show that to tackle only one form of violence is probably insufficient to curb HIV acquisition and transmission risk, supporting the need for combined structural HIV interventions to both support FSWs' rights and ensure access to biomedical interventions for prevention, treatment, and care. Of note, our findings might overestimate the effect of structural interventions because we provided estimates of HIV infections averted if the longer-term excess risk associated with non-condom use was wholly eliminated immediately after implementation. In reality, a reduction in structural determinants (eg, violence or police harassment) and an increased ability of FSWs to negotiate condom use, for example, might occur slowly. In some instances, community empowerment might lead to a transient period of increased violence by clients or regular partners,21, 22 which would reduce short-term intervention effect. Access, not just coverage, remains crucial for prevention and treatment; however, our modelling of antiretroviral therapy coverage does not take into account potential structural barriers to access to treatment, such as stigma.

PANEL 2. FEMALE SEX WORKERS' VOICES FROM KENYA, INDIA, AND CANADA: STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS AND HIV

Direct and indirect effects of policing

Kenya

“It was June, they [the police] found me on the street, took all my condoms I had and destroyed them”119

“It happened last week. The City Council Police told me I was dirtying the town with condoms and took all my condoms”

“Sex workers fear harassment and intimidation by police, so they do not carry condoms” (peer outreach worker)119

Canada (Vancouver)

“You know, you get all these asshole cops and security kicking us off… pushing us into darker and darker areas, you know. That has got to stop… and down here… they'll [the police] pick you up… and make you do something for them just so you can stay there to work. And that's more or less their turf…”120

“We still have to hide any condoms we have onsite in case the police find them”

Violence by clients, police, strangers, intimate partners, and third parties

India (Karnataka)

“My good friend used to come to the [sex work drop-in centre]… her boyfriend drinks alcohol and she was murdered by [him and his friends]. They put stones in her mouth, but she was not dead. Then they put rope around her neck and petrol on her and burned her and she is dead.”121

“He [a goonda (or hired thug)] put handcuffs on me and told me I had to go to the police station, but he took me to a remote place instead. 12 members had sex with me and snatched my money and purse. I have bite marks on my chest [lifts sari to show marks].”121

Canada (Vancouver)

Kenya (Mombasa)

“A client may have skin sores all over the body and you only notice when he undresses and because of fear [of HIV or sexually transmitted infections] you mention it, but instead he beats you up and forces himself on you.”122

Stigma and denial of health services and antiretroviral therapy

Kenya (Mombasa)

“When I fell sick and went to a health centre and they realised that I was a sex worker, they did not treat me like a human being… I was told that he had no time for me. So I left without getting treatment.”

“They [sex workers] fear that if tested positive they will be mistreated.”12

Safer work environments (with supportive management and venue policies, and sex worker and peer support)

India (Karnataka)

“I hear and see mistreatment of sex workers by clients but I will throw them [violent clients] out of the lodge. I call the police patrol too, the mobile jeep, and get the client [out of there].”121

Canada (Vancouver)

“[When violence happens onsite]…the staff have come and they've told him to leave, or they even got the police to get him to leave. They do that right away. It took four cops to get this guy to leave. Then they barred him [from the venue].”123

“All I have to do is yell, and every girl in my building will be there, right? The guy gets scared and leaves. 16 girls show up at your door, banging on your door. He's gonna go, right? People are remembered there too, right?”123

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Science Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Social Sciences Citation Index, Sociological Abstracts, and CAB Direct (CAB Abstracts & Global Health) for peer reviewed reports published in any language from Jan 1, 2008, to Dec 31, 2013, assessing determinants of HIV infection or incidence, or condom use among female sex workers. The search terms used were “Sex work*” OR “sex worker” OR prostitute* OR prostitut* OR “prostitution” OR “commercial sex worker*” OR “sex workers” for sex work, “risk factor” OR “risk factors” OR correlate* OR determinant* OR predictor* OR risk* for risk or protective correlates, “Condom use” OR “non-condom use” OR “condom non-use” OR “unprotected sex” OR “condom refusal” OR condom* OR “condom negotiation” OR “condoms utilization” OR “condoms utilisation” OR “condoms/utilization” OR “condoms/utilization” for condom use, HIV* OR “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “HIV infections” OR AIDS* OR “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” OR “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” OR HIV/AIDS* for HIV. SMG and PD did initial screening and eight reviewers (SMG, PD, PM, SR-P, MR, JL, SAS, and KS) extracted data from relevant reports.

KEY MESSAGES.

Sex workers face a disproportionately large burden of HIV across concentrated and generalised epidemic settings, with substantial heterogeneity in HIV epidemics and structural determinants, as well as features that are very context specific.

Fewer than half of epidemiological studies on HIV acquisition and transmission risk among female sex workers explicitly considered structural determinants.

Epidemiology of HIV and structural determinants among female sex workers is disproportionately drawn from Asia, with large gaps in heavy burden regions of sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, and eastern Europe.

In Canada and Kenya, where sexual violence has an immediate and sustained effect on non-condom use, elimination of violence by clients, police, and strangers could avert 17–20% of HIV infections among female sex workers and their clients over the next decade.

Coverage of and access to prevention and treatment among female sex workers lag behind the general population and scale-up to optimal coverage of condoms and HIV care continuum will probably only be feasible alongside other structural change. In heavy HIV-burden settings, such as Mombasa, where antiretroviral therapy and condom access remain suboptimal, scale-up of antiretroviral therapy access to WHO guidelines of a CD4 cell count of less than 500 cells per μL for both FSWs and their clients could avert 34% of HIV infections and even modest scale-up of sex worker-led outreach could avert 20% of HIV infections among FSWs and their clients over the next decade.

Interventions to promote access to safer sex work environments (eg, changes to venue, management, and policing policies, and access to prevention) could avert a substantial proportion of infections across diverse settings

Modelling suggests that across both generalised and concentrated HIV epidemics, decriminalisation of sex work could have the largest effect on the course of the HIV epidemic, averting 33–46% of incident infections over the next decade through combined effects on violence, police harassment, safer work environments, and HIV transmission pathways.

Acknowledgments

This Review was partly supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA028648, R01DA033147), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the United Nations Population Fund. KS is partially supported by a Canada Research Chair in Global Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS. SAS is partially supported by a NIDA merit award (R37 DA019829). For assistance with the report, we thank Jinghua Li, Nancy Stimson, Ursula Ellis, and Katherine Miller.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO Guidelines: prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections for sex workers in low- and middle-income countries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strathdee SA, Sherman SG. The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4 suppl 3):iii7–14. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Edlin BR. Sexual transmission of HIV-1 among injection drug users in San Francisco, USA: risk-factor analysis. Lancet. 2001;357:1397–401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04562-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD. Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:278–83. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uusküla A, Fischer K, Raudne R. A study on HIV and hepatitis C virus among commercial sex workers in Tallinn. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:189–91. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shannon K, Csete J. Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. JAMA. 2010;304:573–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baral SD, Friedman MR, Geibel S, et al. Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60801-1. published online July 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(14)60801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Radix A, et al. HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. published online July 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, Cowan F. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:659–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shannon K, Montaner JS. The politics and policies of HIV prevention in sex work. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:500–02. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15:450–65. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2012;376:268–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes T. The risk environment: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:8594. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blankenship KM, Bray S, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl A):S11–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchard JF, Aral SO. Emergent properties and structural patterns in sexually transmitted infection and HIV research. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;85(suppl 3):iii4–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diez Roux AV, Aiello AE. Multilevel analysis of infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S25–33. doi: 10.1086/425288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the Risk Environment: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives for a Social Epidemiology of HIV Risk among IDU and SW. In: O’Campo P, Dunn JR, editors. Rethinking social epidemiology: towards a science of change. University of Toronto Press; Toronto: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon K, Goldenberg G, Deering K, Strathdee SA. HIV infection among female sex workers in concentrated and high prevalence epidemics: why a structural determinants framework is needed. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:174–82. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overs C. An analysis of HIV prevention programming to prevent HIV transmission during commercial sex in developing countries. WHO; Geneva: 2002. Sex workers: part of the solution. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reza-Paul S, Lorway R, O’Brien N, et al. Sex worker-led structural interventions in India: a case study on addressing violence in HIV prevention through the Ashodaya Samithi collective in Mysore. India J Med Res. 2012;135:98–106. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.93431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beattie TS, Bhattacharjee P, Ramesh BM, et al. Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:476. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahmanesh M, Wayal S, Copas A, Patel V, Mabey D, Cowan F. A study comparing sexually transmitted infections and HIV among ex-Red-Light District and non-Red-Light District sex workers after the demolition of Baina Red-Light District. JAIDS. 2009;52:253–57. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Rusch M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:659–65. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reza-Paul S, Beattie T, Syed HU, et al. Declines in risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infection prevalence following a community-led HIV preventive intervention among female sex workers in Mysore, India. AIDS. 2008;22(suppl 5):S91–100. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343767.08197.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pando MA, Coloccini RS, Reynaga E, et al. Violence as a barrier for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Argentina. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed E, Silverman JG, Stein B, et al. Motherhood and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: the need to consider women’s life contexts. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:543–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saggurti N, Verma RK, Halli SS, et al. Motivations for entry into sex work and HIV risk among mobile female sex workers in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2011;43:535–54. doi: 10.1017/S0021932011000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, Devireddy V, Blankenship KM. The role of housing in determining HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: considering women’s life contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:710–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urada LA, Morisky DE, Pimentel-Simbulan N, Silverman JG, Strathdee SA. Condom negotiations among female sex workers in the Philippines: environmental influences. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decker MR, McCauley HL, Phuengsamran D, Janyam S, Silverman JG. Sex trafficking, sexual risk, sexually transmitted infection and reproductive health among female sex workers in Thailand. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:334–39. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.096834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang DM, Tao XR, Liao MZ, et al. An integrated individual, community, and structural intervention to reduce HIV/STI risks among female sex workers in China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:717. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramesh S, Ganju D, Mahapatra B, Mishra RM, Saggurti N. Relationship between mobility, violence and HIV/STI among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:764. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobela F, Pepin J, Gbeleou S, et al. A tale of two countries: HIV among core groups in Togo. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:216–23. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c170f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decker MR, Wirtz AL, Baral SD, et al. Injection drug use, sexual risk, violence and STI/HIV among Moscow female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:278–83. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaines T, Rusch M, Brouwer K, et al. The Effect of geography on HIV and sexually transmitted infections in Tijuana’s red light district. J Urban Health. 2013;90:915–20. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9735-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao X, Wang W. Sentinel surveillance of HIV/AIDS in female sex workers in Kecheng district of Quzhou city, Zhejiang province, 2011. Dis Surveill. 2012;27:300–03. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldenberg SM, Chettiar J, Simo A, et al. Early sex work initiation independently elevates odds of HIV infection and police arrest among adult sex workers in a Canadian setting. J Acqir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:122–28. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a98ee6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deering KN, Boily MC, Lowndes CM, et al. A dose-response relationship between exposure to a large-scale HIV preventive intervention and consistent condom use with different sexual partners of female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(suppl 6):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blankenship KA, West BS, Kershaw TS, Biradavolu MR. Power, community mobilization, and condom use practices among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2008;22(suppl 5):S109–16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000343769.92949.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erausquin JT, Biradavolu M, Reed E, Burroway R, Blankenship KM. Trends in condom use among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: the impact of a community mobilization intervention. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(suppl 2):ii49–54. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanchard AK, Mohan HL, Shahmanesh M, et al. Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bharat S, Mahapatra B, Roy S, Saggurti N. Are female sex workers able to negotiate condom use with male clients? The case of mobile FSWs in four high HIV prevalence states of India. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luchters S, Chersich MF, Rinyiru A, et al. Impact of five years of peer-mediated interventions on sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lippman SA, Donini A, Diaz J, Chinaglia M, Reingold A, Kerrigan D. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: the Encontros intervention in Brazil. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S216–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerrigan D, Telles P, Torres H, Overs C, Castle C. Community development and HIV/STI-related vulnerability among female sex workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:137–45. doi: 10.1093/her/cym011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mainkar MM, Pardeshi DB, Dale J, et al. Targeted interventions of the Avahan program and their association with intermediate outcomes among female sex workers in Maharashtra, India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(suppl 6):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]