SUMMARY

Pain processing in the spinal cord has been postulated to rely on nociceptive transmission (T) neurons receiving inputs from nociceptors and Aβ mechanoreceptors, with Aβ inputs gated through feed-forward activation of spinal inhibitory neurons (IN). Here we used intersectional genetic manipulations to identify these critical components of pain transduction. Marking and ablating six populations of spinal excitatory and inhibitory neurons, coupled with behavioral and electrophysiological analysis, showed that excitatory neurons expressing somatostatin (SOM) represent T-type cells, whose ablation causes loss of mechanical pain. Inhibitory neurons marked by the expression of dynorphin (Dyn) represent IN-type neurons, which are necessary to gate Aβ fibers from activating SOM+ neurons to evoke pain. Therefore, peripheral mechanical nociceptors and Aβ mechanoreceptors, together with spinal SOM+ excitatory and Dyn+ inhibitory neurons form a microcircuit that transmits and gates mechanical pain.

INTRODUCTION

The dorsal spinal cord is the integrative center that processes and transmits a variety of somatic sensory modalities, such as pain, itch, cold, warm and touch. In the past century, two dominant theories, specificity versus pattern, have been proposed to explain how pain modality is encoded. In late 1960s, Perl and colleagues identified nociceptors in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and nociceptive relay neurons in the dorsal spinal cord, lending support for the existence of pain-specific circuits (Bessou and Perl, 1969; Burgess and Perl, 1967; Christensen and Perl, 1970). Meanwhile, the pattern theory argues that processing of pain-related information can be modulated by brain states and by inputs from other types of sensory fibers (Head, 1905; Melzack and Wall, 1982; Noordenbos, 1987). In particular, the gate control theory of pain, proposed by Melzack and Wall in 1965 and revised in 1978, argues that spinal nociceptive transmission (T) neurons also receive inputs from low threshold Aβ mechanoreceptors, but this input is gated by feed-forward activation of inhibitory neurons (INs) located in the substantia gelatinosa (lamina II) of the dorsal horn (Melzack and Wall, 1965; Wall, 1978) (Figure 1A).

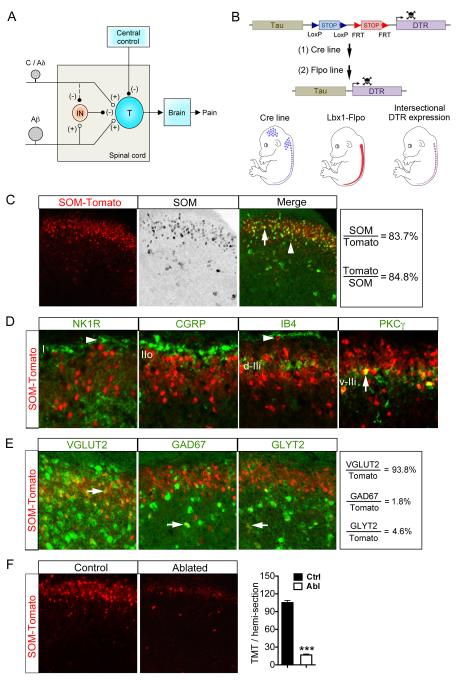

Figure 1. Intersectional Ablation of SOM lineage Neurons in Spinal Dorsal Horn.

(A) Schematics showing the modified gate control theory of pain. “T” represents a spinal pain transmission neuron. “IN”: an inhibitory neuron. “(+)” and “(−)” represent excitatory and inhibitory inputs, respectively. The dashed line from C/Aδ to IN indicates that C/Aδ fibers might activate an unknown pathway to silence IN activity, but this pathway and descending modulation from brain were not studied here.

(B) Schematics showing strategy of intersectional ablation in the dorsal spinal cord. “DTR”: diphtheria toxin receptor.

(C, D) Double staining of Tomato with SOM mRNA (C) or with other markers (D), on saggital (NK1R) or transverse (others) lumbar spinal sections of adult SOM-Tomato mice. Arrows indicate co-localization. Arrowheads indicate lamina I neurons with singular expression of NK1R or Tomato.

(E) Double labeling of Tomato and with indicated mRNAs. Arrows indicate co-localization.

(F) Ablation of SOM-Tomato+ neurons in lumbar dorsal spinal cord [105 ± 4 in control (“Ctrl”) group vs 17 ± 2 in ablated (“Abl”) group, n = 15-17 hemi-sections from 3 mice per group; p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test]. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S1.

Nearly 50 years later, numerous studies tried to test the key argument of the gate control theory of pain (Braz et al., 2014; Mendell, 2014). Firstly, this theory correctly predicts that disinhibition could be a reason for the manifestation of mechanical allodynia or pain evoked by innocuous mechanical stimuli (Prescott et al., 2014; Price et al., 2009; Sandkühler, 2009; Zeilhofer et al., 2012). Secondly, electrophysiological studies have revealed the existence of a polysynaptic excitatory circuit that links Aβ fibers from lamina III to lamina I ascending projection neurons (Baba et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2013; Miraucourt et al., 2007; Torsney and MacDermott, 2006).

Despite this progress, precise identities of spinal neurons that transmit and gate pain-related information remain unknown (Braz et al., 2014; Prescott et al., 2014). Dorsal horn excitatory and inhibitory neurons are extremely heterogeneous, as indicated by distinct molecular markers, firing patterns, and morphologies (Ribeiro-da-Silva and De Koninck, 2008; Todd, 2010). To identify spinal neurons required to process somatic sensory information, one effective approach has been the usage of saporin-conjugated peptides to ablate spinal neurons expressing specific peptide receptors (Carstens et al., 2010; Mantyh et al., 1997; Mishra and Hoon, 2013; Sun et al., 2009). However, this approach has a potential complication, which is that intrathecal injection of a saporin-conjugated peptide might ablate central terminals originating from primary sensory neurons that also express the receptor for this particular peptide. Thus, to date, it is still not known if there are spinal excitatory neurons required to sense specific pain sub-modalities, such as thermal versus mechanical. Nor is it known about the identities of the inhibitory neurons that gate pain-related information.

Here we have designed an intersectional genetic strategy (Dymecki and Kim, 2007) that allows us to specifically mark and ablate a cohort of molecularly defined subpopulations of spinal excitatory or inhibitory neurons. Subsequent behavioral and electrophysiological studies have identified two populations of spinal neurons, the somatostatin (SOM) lineage excitatory neurons and the dynorphin (Dyn) lineage inhibitory neurons, as parts of the spinal circuit that transmits and gates mechanical pain.

RESULTS

Intersectional Genetic Ablation of Dorsal Spinal Excitatory and Inhibitory Neurons

To map spinal circuits processing somatic sensory information, we used an intersectional genetic strategy to ablate individual populations of spinal excitatory and inhibitory neurons. To do this, three sets of mouse lines are involved (Figure 1B). The first one is the intersectional TauloxP-STOP-loxP-FRT-STOP-FRT-DTR (or TauDTR/+) mice, in which the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) gene (Saito et al., 2001) is driven from the pan-neuronal Tau promoter (Figure 1B). The DTR expression is, however, not activated until after removal of two STOP cassettes by the Cre and flippase (Flpo) DNA recombinases. The second line is Lbx1Flpo/+, in which Flpo is driven from the Lbx1 promoter. Importantly, Lbx1-Flpo drove reporter expression only in neurons derived from the dorsal spinal cord and the dorsal hindbrain (Figure S1A and S1B). Moreover, the Lbx1 lineage neurons include all of inhibitory neurons located in the dorsal horn (Gross et al., 2002; Müller et al., 2002), and excitatory neurons required to sense pain and itch (Xu et al., 2013). The third set of mouse lines includes various Cre lines. By crossing these three sets of mouse lines together (TauDTR/+, Lbx1Flpo/+ and Cre mice), only spinal neurons that express both Cre and Flpo will remove both STOP cassettes and activate DTR expression (Figure 1B). Upon diphtheria toxin (DTX) injection, these DTR-expressing spinal neurons can be ablated selectively.

In total we ablated and analyzed 6 lineages of spinal neurons, with a specific goal of identifying neurons involved with transmission and/or gate control of mechanical pain. Three lineages represent predominantly excitatory neurons marked by Cre driven from the somatostatin gene (SOM-Cre), the calbindin 2/calretinin gene (Calb2-Cre) or the preprotachykinin 2 gene (Tac2-Cre) (Mar et al., 2012; Taniguchi et al., 2011). We found that only SOM lineage excitatory neurons are required to sense mechanical pain (see below). Three other lineages of spinal neurons are mainly inhibitory and are marked by Cre driven from the preprodynorphin gene (Pdyn-IRES-Cre, referred here to as Dyn-Cre) (Krashes et al., 2014), the neuropeptide Y gene (Npy-Cre), or the choline acetyltransferase gene (ChAT-Cre) (Rossi et al., 2011). We found that only the Dyn lineage inhibitory neurons are required to gate mechanical pain. In the remaining text, we will present evidence supporting that SOM excitatory neurons and Dyn inhibitory neurons form a circuit for a gate control of mechanical pain.

Genetic Marking of Spinal SOM Lineage Excitatory Neurons

To mark SOM lineage neurons with Tomato expression, we crossed SOMCre/+ mice (Taniguchi et al., 2011) with ROSA26CAG-loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato reporter mice, simplified as ROSA26tdTomato/+ mice (Madisen et al., 2010), with resulting double heterozygous mice referred to as SOM-Tomato. Double staining shows that 84% (1022/1221) of Tomato+ neurons exhibit detectable SOM mRNA, and 85% (1022/1205) of SOM mRNA+ neurons coexpress Tomato (Figure 1C), indicating that SOM-Cre faithfully marks most SOM+ neurons. The 16% of SOM-Tomato+ neurons without detectable SOM mRNA could represent neurons with transient SOM expression.

We next determined laminar distribution of SOM-Tomato+ neurons. NK1R expression marks a large fraction of ascending projection neurons located in dorsal horn lamina I (Todd, 2010). SOM-Tomato+ neurons are located mainly ventral to NK1R+ neurons, with almost none (0/98) of lamina I neurons with high NK1R expression coexpressing SOM-Tomato (Figure 1D). Lamina II is subdivided into three sub-layers. The outer layer (IIo) is innervated by CGRP+ peptidergic DRG neurons. The dorsal inner layer (d-IIi) is innervated by DRG neurons labeled by isolectin B4 (IB4), and the ventral inner layer (v-IIi) is partly defined by interneurons that express protein kinase C γ (PKCγ) (Braz et al., 2014; Todd, 2010). SOM-Tomato+ neurons are intermingled with CGRP+ terminals in IIo and with IB4+ terminals in d-IIi. The ventral limit of dense SOM-Tomato+ neurons matches with dense PKCγ+ neurons in v-IIi, and a subset of PKCγ+ neurons coexpress Tomato (Figure 1D). Double staining with NeuN, which marks most, but not all, dorsal horn neurons, shows that SOM-Tomato+ neurons represent 7% (25/348) and 37% (711/1926) of NeuN+ neurons in lamina I and lamina II, respectively (Figure S1C). Thus, SOM-Tomato+ neurons are confined mainly to lamina II, but also scattered in laminae I and III-V (Figure 1C and 1D).

Regarding neurotransmitter phenotypes, 94% (1139/1214) of Tomato+ neurons express the vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT2 (Figure 1E), a marker for glutamatergic excitatory neurons (Fremeau et al., 2004). SOM-Tomato+ neurons represent 19% (62/329) and 53% (884/1677) of VGLUT2+ neurons in lamina I and lamina II, respectively. Only ~2% (21/1277) of SOM-Tomato+ neurons express the GABAergic inhibitory neuron marker GAD67 (Zeilhofer et al., 2012). Additionally, about 5% (65/1417) of SOM-Tomato+ neurons express the glycinergic inhibitory neuron marker GLYT2 (Zeilhofer et al., 2012), which scatter mainly in laminae III-V (Figure 1E). Thus, a majority of SOM-Tomato+ neurons are excitatory, consistent with previous reports (Yasaka et al., 2010). These SOM-Tomato+ excitatory neurons are heterogeneous, with distinct firing patterns and morphologies (Figure S1D and S1E).

Ablation of SOM Lineage Neurons Leads to Loss of Acute Mechanical Pain

To ablate SOM lineage neurons, we crossed SOMCre/+ mice with TauDTR/+ and Lbx1Flpo/+ mice. To monitor ablation efficacy, they were further crossed with ROSATomato/+ reporter mice to mark SOM lineage neurons. The resulting TauDTR/+;ROSATomato/+;Lbx1Flpo/+;SOMCre/+ quadruple heterozygous mice were injected twice with DTX, and these mice are referred to as SOM ablated (Abl) mice. Four weeks after DTX injection, SOM-Tomato+ neurons were ablated in lumbar dorsal spinal cord by 82% (Figure 1F), and in the hindbrain spinal trigeminal nucleus (Sp5) (Figure S2A), but not in DRGs or other brain regions (Figure S2A).

We next performed behavioral analyses in SOM Abl mice, using littermates that lacked DTR expression but received the same DTX injections as controls. We found that ablation of SOM neurons did not affect sensorimotor coordination or the senses of innocuous touch, heat or cold (Figure S2B-S2H). In contrast, mechanical pain was markedly impaired. We first used von Frey filaments to deliver punctate mechanical stimuli onto the plantar hindpaw. SOM Abl mice showed no response at all, even with the maximal strength (2.56 g for the cutoff) used by the up-down method (Figure 2A) (Chaplan et al., 1994), and this loss is further confirmed by measuring withdrawal percentages to repeated von Frey fiber stimulation (Figure 2B). We next performed the pinprick test onto the hindpaw plantar surface, which evoked withdrawal responses in control mice, but not in SOM Abl mice (Figure 2C). We finally performed the pinch test, by placing an alligator clamp onto the hindpaw plantar surface, and measured licking responses. Licking behavior involves supraspinal processing of noxious sensory information and is considered to be a readout of feeling pain (Wang et al., 2013). The duration of licking is greatly reduced in SOM Abl mice (Figure 2D), further suggesting impairment of mechanical pain. In contrast, neither Tac2 nor Calb2 lineage neurons play major roles in sensing mechanical pain, except a loss of sensing light punctate mechanical stimuli in Calb2 Abl mice (Figures S3-S5).

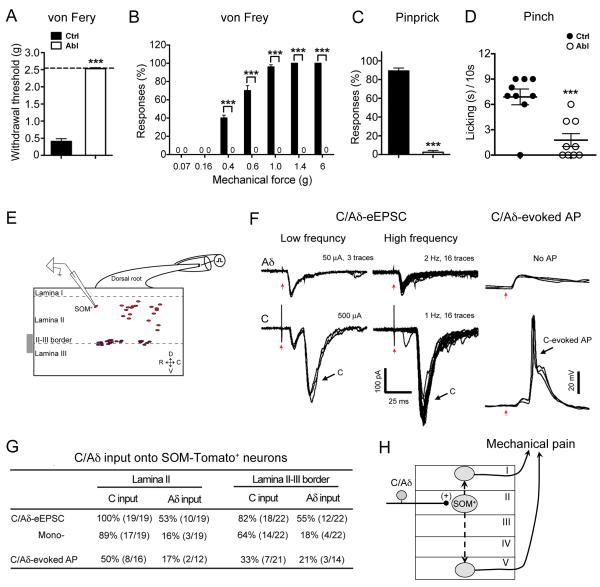

Figure 2. Loss of Acute Mechanical Pain in SOM Abl Mice and C/Aδ Inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ Neurons.

(A) Increase of withdrawal thresholds to von Frey fiber stimulation in SOM Abl mice (“Abl”) by up-down method [n = 13 in control (“Ctrl”) group, n = 11 in Abl group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test].

(B) Reduced withdrawal percentages in SOM Abl mice in response to von Frey filaments (n = 5 in each group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test)

(C) Lost response to pinprick stimulation in SOM Abl mice (n = 13 in Ctrl group, n = 11 in Abl group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test).

(D) Greatly attenuated licking/flinching response to pinching in Abl mice (n = 9 in Ctrl group, n = 9 in Abl group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test).

(E) Schematics showing relative positions of recorded SOM-Tomato+ neurons.

(F) Typical traces of C/Aδ-evoked EPSCs and APs showing C/Aδ-fiber inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ neurons. Red arrows indicate stimulation artifacts.

(G) The table is a summary of inputs in 41 recorded SOM-Tomato+ neurons from 8 mice.

(H) Schematics showing that SOM-Tomato+ neurons in lamina II receive mono-C/Aδ input and transmit noxious signaling to lamina I and/or V pain output neurons, either directly or indirectly (dashed arrows). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S1-S5.

C and Aδ Fiber Inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ Neurons in Lamina II

We next examined sensory afferent inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ neurons. We first performed dorsal root compound action potential recordings to determine electric stimulation intensities required to activate Aβ, Aδ and C fibers. In total, 6 mice at P23-P26 were used. The thresholds for Aβ, Aδ and C fibers, as indicated by fast, medium, and slow conduction velocities, are 12-16 μA, 30-35 μA and 150-300 μA, respectively (Figure S1F and S1G). Accordingly, the intensity ranges used in this study for different fibers are: ≤ 25 μA for Aβ, 30-100 μA for Aδ, and 150-500 μA for C fibers.

We next prepared spinal cord slices with attached dorsal root, and whole-cell patch configuration was used to record synaptic inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ neurons directly visualized under a fluorescent microscope. Three recording conditions were used. Firstly, to detect both large and small evoked excitatory postsynaptic current (eEPSC), we held membrane potential at −70 mV to minimize evoked inhibitory postsynaptic current (eIPSC) (Yoshimura and Nishi, 1995). High-frequency stimulation was then used to determine monosynaptic inputs, as indicated by one-on-one responses (Baba et al., 2003; Lu and Perl, 2005; Torsney and MacDermott, 2006). It should be noted that a lack of one-on-one responses to high-frequency stimulation is often used to indicate polysynaptic inputs (Baba et al., 2003; Torsney and MacDermott, 2006), but could also indicate monosynaptic inputs with feed-forward inhibition (Bruno, 2011). Secondly, by holding membrane potential at −45 mV, both eEPSCs and eIPSCs can be recorded. Thirdly, we used current clamp mode to record evoked excitatory postsynaptic potenials (eEPSPs) to determine whether the stimulation drove action potential (AP) firing at resting membrane potential.

We first recorded Aδ and C fiber inputs that are known to include nociceptors (Aβ inputs will be described in the next section). In total, 41 SOM-Tomato+ neurons from 8 mice at P23-P30 were recorded. We found that 100% of SOM-Tomato+ neurons in lamina II receive C fiber inputs, 89% (17/19) of them receive monosynaptic inputs indicated by one-on-one responses to high-frequency stimulations at 1 Hz, and 50% (8/16) of them generated AP output (Figure 2E-2G). A majority of SOM-Tomato+ neurons located at the lamina II-III border (18/22) also received C fiber inputs, 33% of which generated AP output (Figure 2E-2G). Finally, over half of SOM-Tomato+ neurons received Aδ fiber inputs, but only 17-21% of them generated AP outputs (Figure 2G).

Earlier in vivo extracellular recordings showed that spinal neurons located in IIo and d-IIi predominantly receive nociceptive inputs (Bennett et al., 1980; Cervero et al., 1979; Cervero et al., 1976; Christensen and Perl, 1970; Kumazawa and Perl, 1978; Light et al., 1979). Given the loss of acute mechanical pain in SOM Abl mice, C and/or Aδ neurons that form synaptic connections with SOM-Tomato+ neurons in IIo and d-IIi likely represent mechanical nociceptors. These lamina II SOM-Tomato+ neurons may be directly or indirectly connected to projection neurons enriched in lamina I and lamina V (Todd, 2010) (summarized in Figure 2H). SOM-Tomato+ neurons in v-IIi and at II-III border might receive inputs from low threshold C/Aδ mechanoreceptors (Abraira and Ginty, 2013).

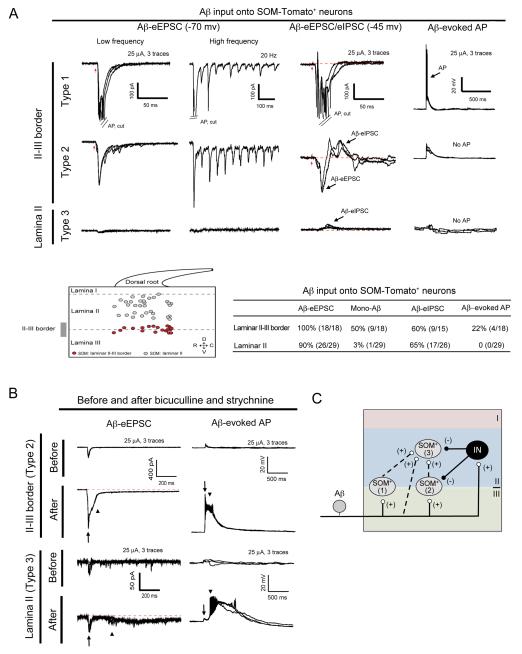

Aβ Inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ Neurons in the Spinal Dorsal Horn

According to the gate control theory, spinal pain transmission neurons also receive inputs from low-threshold Aβ mechanoreceptors that normally terminate in lamina III-V (Figure 1A). To assess Aβ inputs onto SOM-Tomato+ neurons, the dorsal root was stimulated at the Aβ intensity range (≤ 25 μA) and in total, 47 SOM-Tomato+ neurons from 9 mice at P23-P30 were recorded. We identified three types of SOM-Tomato+ neurons. Both type 1 and type 2 neurons are located at the II-III border, and type 1 cells (4/18) receive monosynaptic Aβ inputs with AP output, and type 2 cells (14/18) receive fast Aβ inputs with feed-forward inhibition and do not generate Aβ-evoked APs under normal ACSF recording conditions. In the presence of bicuculline and strychnine, type 2 neurons can, however, generate Aβ-evoked fast APs, and a subset of them fire slow APs, as well (Figure 3A and 3B), indicating that Aβ inputs onto type 2 neurons are gated by bicuculline-sensitive GABAA and/or strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors. 5 of 14 type 2 neurons show relatively large Aβ-evoked EPSCs and generated one-on-one responses to high-frequency stimulation, indicating monosynaptic inputs (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Aβ Input onto SOM-Tomato+ Neurons in Different Spinal Laminae.

(A) Aβ input onto SOM-Tomato+ neurons. Upper lane shows three typical traces. Middle showing the relative positions and summary of Aβ inputs onto 47 SOM-Tomato+ neurons from 9 mice. SOM+ neurons are divided into three types (1-3). Red arrows indicate stimulation artifacts.

(B) Aβ-evoked EPSCs and EPSPs in type 2 or 3 SOM-Tomato+ neurons before and after bath application of bicuculline (10 μM) and strychnine (2 μM). Arrows and arrowheads indicate fast and slow eEPSCs/eEPSPs/APs, respectively. 4 mice were used. (C) Schematics showing Aβ inputs into types 1-3 of SOM-Tomato+ neurons. “IN”: inhibitory neurons. See also Figure S1.

Type 3 neurons represent most SOM-Tomato+ neurons within lamina II. Like type 2 neurons, they receive fast (latency < 10 ms) Aβ inputs without AP output (Figure 3A). Importantly, the amplitudes of Aβ-evoked fast EPSCs do not increase in the presence of bicuculline and strychnine (Figure 3B), thereby distinguishing them from type 2 neurons. Bicuculline and strychnine treatment did, however, result in long-lasting Aβ-evoked EPSCs with a slow onset (with latency ≥ 10 ms) and multiple APs (Figure 3B). As described below, SOM-Tomato+ neurons are required to transmit Aβ inputs onto lamina I and II neurons. Thus, type 3 neurons receive a fast Aβ input (either directly or indirectly via type 1 neurons) that is gated through a mechanism insensitive to bicuculline and strychnine, and a slow Aβ input (possibly via type 2 neurons) that is gated by bicuculline/strychnine-sensitive feed-forward inhibition (summarized in Figure 3C).

Loss of Aβ Inputs onto Superficial Dorsal Horn Neurons in SOM Abl Mice

We next recorded Aβ inputs in spinal cord slices prepared from control and SOM Abl mice with and without the presence of bicuculline/strychnine. In total, 16 control mice (P23-P30) and 9 ablated mice (P26-P30; 7-12 days after the first DTX injection) were used. In II-III border neurons from control mice, Aβ fiber stimulation under the normal ACSF recording conditions drove AP firing in 5% (2/38) of recorded neurons (see below, Figure 7A), and this percentage increased to 74% (14/19) in the presence of bicuculline and strychnine, with Aβ stimulation evoking both fast and slow AP firing (Figure 4A). In other words, Aβ inputs onto 69% (74% – 5%) of II-III border neurons are gated through bicuculline-sensitive GABAA and/or strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors. In SOM Abl mice, none (0/24) of II-III border neurons could generate Aβ-evoked APs (Figure 4A). In I/IIo neurons from control mice, Aβ fiber stimulation under normal ACSF recording conditions drove AP firing in 7% (5/69) of neurons (see below, Figure 7A), and this percentage was increased to 85% (11/13) in the presence of bicuculline and strychnine (Figure 4A), with Aβ stimulation evoking slow, but no fast, AP firing. In SOM Abl mice, only 4% (1/23) of I/IIo neurons could generate AP firing under the same disinhibition conditions. Collectively, these results show that SOM-Tomato+ neurons are required to relay Aβ inputs from the lamina II-III border to lamina I (Figure 4B).

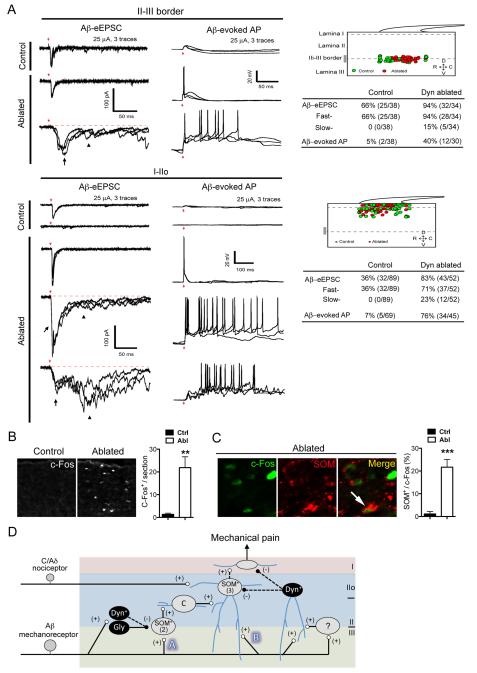

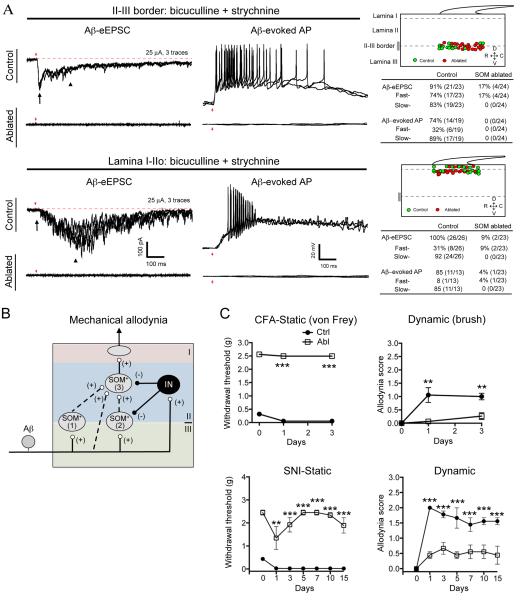

Figure 7. Dyn Neurons Gate Mechanical Pain.

(A) Aβ-evoked EPSCs/APs in the spinal dorsal horn of control and Dyn Abl mice. Left panel showing typical traces. Right panel indicates positions of recorded neurons and summary. 27 control mice and 11 ablated mice were used. Red arrows indicate stimulation artifacts. Black arrows indicate fast eEPSCs. Arrowheads indicated slow eEPSCs.

(B) Brush-evoked c-Fos induction in the dorsal spinal cord of Dyn Abl and control mice [n = 12 sections in control (“Ctrl”) group, n = 9 sections in Abl group, 3 mice in each group; **, p < 0.01, Student’s unpaired t test].

(C) Double immunostaining of c-Fos with SOM (arrow) following back brush stimuli in Dyn Abl and control mice (n = 12 thoracic spinal sections in Ctrl and Abl groups, 4 mice in each group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test).

(D) Schematic showing circuitry processing mechanical pain-related information. Vertical neurons in lamina IIo, belonging to type 3 SOM+ neurons [“(3)”], receive inputs from C/Aδ mechanical nociceptors, and also from Aβ mechanoreceptors through two pathways: indirect (“A”) and direct (“B”). Pathway “A” is transmitted through type 2 SOM+ [“(2)”] neurons at the II-III border, via transient-central (“C”) cells and vertical cells in lamina IIo, and finally to lamina I projection neurons, although it is not known if the connection from vertical cells to projection neurons is direct or indirect. Type 2 SOM+ neurons may include PKCγ+ neurons. Pathway “A” is partly gated by Dyn+ neurons. Pathway “B” is indicated by direct Aβ inputs onto lamina IIo neurons, and is gated by dorsally located Dyn+ neurons that receive Aβ inputs with AP output, either directly or via type 1 SOM+ neurons or unidentified interneurons (“?”). Dashed arrows indicate that SOM+ neurons might receive direct inhibitory inputs from Dyn+ neurons, but further studies are required to confirm this. Our data do not rule out that Dyn+ neurons might also directly gate lamina I projection neurons. For details, see Discussion. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 4. Loss of Aβ Inputs onto Lamina I/II Neurons and Mechanical Allodynia in SOM Abl mice.

(A) Aβ-evoked EPSCs/APs in spinal neurons from control and SOM Abl mice. Left panel shows typical traces and right panel includes the positions of recorded neurons and summary. Red arrows indicate stimulation artifacts. Black arrows and Arrowheads indicate fast and slow eEPSCs, respectively.

(B) Schematics showing SOM neurons linking Aβ fibers to lamina I neurons, which is gated by inhibitory neurons.

(C) Loss of static (von Frey assay) and dynamic (brush assay) mechanical allodynia following peripheral inflammation and nerve injury in SOM Abl mice (“Abl”, open rectangle) in comparison with control (“Ctrl”, solid circles) (n = 6-7 in each group; p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S2.

Loss of Mechanical Allodynia in SOM Abl Mice

A hallmark of inflammatory and neuropathic pain is the manifestation of allodynia or pain evoked by low-threshold mechanical stimuli (Zeilhofer et al., 2012). With the loss of Aβ inputs onto superficial dorsal horn neurons of SOM Abl mice, we next asked whether mechanical allodynia was compromised. To model inflammatory pain, complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) was injected into the plantar of the hindpaw, and to assess neuropathic pain, we used the spared nerve injury (SNI) model (Decosterd and Woolf, 2000). Two types of mechanical allodynia, static and dynamic, are observed in human patients (Campbell and Meyer, 2006). Static allodynia is evoked by punctate stimuli and measured by the von Frey assay. Dynamic allodynia is evoked by movement across the skin and mediated by Aβ fibers (Campbell et al., 1988; Koltzenburg et al., 1992). In mice, dynamic allodynia was measured by stroking the hindpaw plantar with a soft paintbrush, using the scoring system developed by Dr. Enrique José Cobos (personal communication). The typical response of naive mice to dynamic stimuli is briefly lifting the paw and walking away. This response was used for the touch assay described in Figure S2C, but for allodynia measurement, this baseline response was scored as 0. After inflammation and nerve lesions, dynamic allodynia is scored as the following, with 1 for sustained lifting of the paw towards the body, 2 for strong lateral lifting above the level of the body, and 3 for flinching or licking of the affected paw. Strikingly, both static and dynamic allodynia were abolished or greatly reduced in SOM Abl mice (Figure 4C and Figure S2I), without affecting heat hyperalgesia (Figure S2J). In contrast, nerve lesion-induced mechanical allodynia is unaffected in either Tac2 Abl mice (Figure S3I) or Calb2 Abl mice (Figures S5K).

Genetic Marking and Ablation of Dyn-expressing Spinal Inhibitory Neurons

The above studies show that Aβ input onto most SOM-Tomato+ neurons is gated by feed-forward inhibition. In the remaining sections, we will present evidence supporting the model that the Dyn lineage inhibitory neurons marked by Dyn-Cre act to gate mechanical pain.

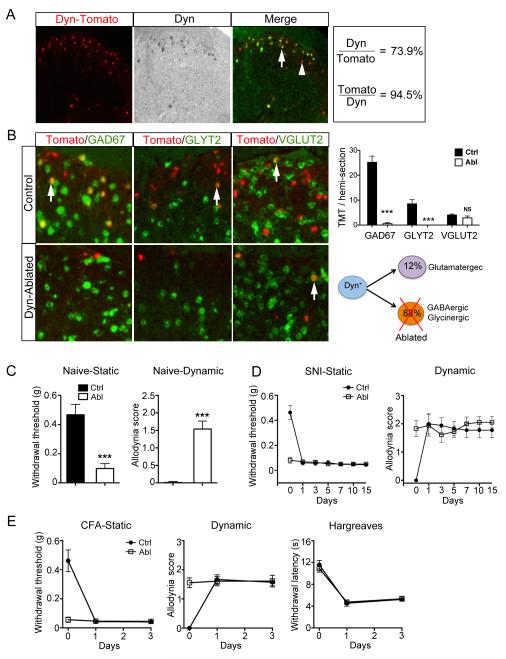

We crossed DynCre/+ mice with the RosaTomato/+ reporter to mark Dyn lineage neurons. 74% (147/199) of Dyn-Tomato+ neurons exhibited detectable Dyn mRNA and 95% (173/183) of neurons with detectable Dyn mRNA coexpressed Tomato (Figure 5A). Thus, Dyn-Cre marks most neurons with persistent Dyn expression, and a small number of neurons that likely express Dyn transiently. Dyn-Tomato+ neurons are located mainly in laminae I and II, and minorly in laminae III-V (Figure 5A). 86% (151/175) of them are GAD67+ GABAergic inhibitory neurons, but only a small subset of GAD67+ neurons coexpress Dyn-Tomato (Figure 5B). 28% (51/189) of Dyn-Tomato+ neurons are GLYT2+ glycinergic inhibitory neurons, and they are located close to the II-III border (Figure 5B). Only 12% (24/202) are VGLUT2+ glutamatergic neurons (Figure 5B). The predominant association with inhibitory neurons is consistent with previous reports (Sardell et al., 2011). Consistently, half of the Dyn-Tomato+ neurons exhibit tonic firing (Figure S7A), a pattern shared by many inhibitory interneurons (Yasaka et al., 2010).

Figure 5. Spontaneous Development of Mechanical Allodynia in Dyn Abl mice.

(A) Double staining of Tomato and Dyn mRNA in the spinal cord of Dyn-Tomato mice.

(B) Double staining of Tomato and indicated mRNAs in Dyn-Tomato control mice and Dyn Abl mice. Right panel (upper) is quantification analysis. Schematics in lower right showing selective ablation of inhibitory Dyn lineage neurons.

(C) Reduction of withdrawal threshold to static stimuli (von Frey assay) and increase in dynamic allodynia score (brush assay) in Dyn neuron-ablated (“Abl”) mice [n = 15 in control (“Ctrl”) group, n = 10 in Abl group; ***, p < 0.001, Student’s unpaired t test].

(D, E) After spared nerve injury (SNI) (D) or peripheral inflammation by CFA treatment (E), control mice show a reduction in withdrawal thresholds to static stimuli by von Frey assay and an increase of dynamic allodynia score by the brush assay (n = 7, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis). No difference before and after nerve injury or inflammation in Abl mice (n = 6; p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S6 and S7.

To examine the function of Dyn lineage neurons, we generated Dyn Abl mice, as how we generated SOM Abl mice. The vast majority of Dyn-Tomato+ inhibitory neurons marked by GAD67 or GLYT2 were ablated in the dorsal horn (Figure 5B) and the hindbrain Sp5 nucleus, but not in other brain areas, and the ablation did not affect afferent projections (Figure S7B). However, DTX treatment did not ablate Dyn-Tomato+ VGLUT2+ glutamatergic neurons (Figure 5B), suggesting that these excitatory neurons might originate from Lbx1-negative spinal neurons (Gross et al., 2002; Müller et al., 2002).

Spontaneous Development of Mechanical Allodynia in Dyn Abl Mice

We next performed behavioral analyses in Dyn Abl mice, using littermates as controls. We found that Dyn Abl and control mice did not exhibit differences in locomotion coordination (data not shown), or in responses to heat or cold stimuli (Figure S7D-S7G). Furthermore, ablation of Dyn-Tomato+ neurons in adult mice did not change itch sensitivity (for discussion, see Figure S7H-S7M). Strikingly, Dyn Abl mice showed spontaneous development of both static and dynamic mechanical allodynia (Figure 5C). Moreover, the values of allodynia cannot be further increased by inflammation or nerve injury (Figure 5D and 5E). In contrast, no allodynia developed upon ablation of ChAT (Figure S6) or Npy (described elsewhere) lineages of inhibitory neurons. Thus, Dyn lineage neurons are uniquely required to gate mechanical pain.

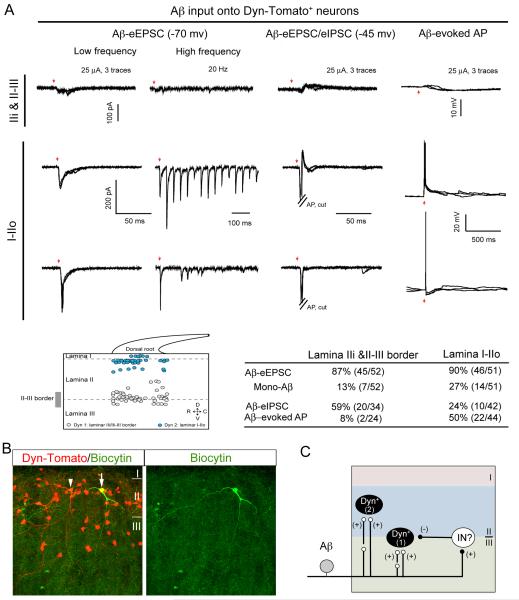

Dyn-Tomato+ Neurons in Lamina IIo Receive Aβ Inputs with AP Firing

We next examined afferent inputs onto Dyn-Tomato+ neurons. In total, 103 Dyn-Tomato+ neurons from 16 mice at P24-P30 were recorded. At Aβ stimulation intensity range, eEPSCs can be detected in the vast majority of Dyn-Tomato+ neurons at −70 mV (Figure 6A). However, the strength of Aβ input is quite different in different laminae. In IIi and at the II-III border, most Dyn-Tomato+ neurons (22/24) receive Aβ input with small eEPSCs and feed-forward inhibition, and only a few of them (2/24) produce Aβ-evoked APs. In contrast, Dyn-Tomato+ neurons in laminae I and IIo receive monosynaptic or polysynaptic Aβ input with less feed-forward inhibition, and more than half of them produce Aβ-evoked APs (Figure 6A). Dorsally located Dyn-Tomato+ neurons include vertical cells that send dendrites all the way to lamina III-IV (Figure 6B), thereby forming an anatomical basis for receiving direct Aβ inputs.

Figure 6. Aβ Input onto Dyn-Tomato+ Neurons.

(A) Aβ input onto Dyn-Toamto+ neurons. Upper lanes show typical traces. Middle showing the relative positions and summary of recorded Dyn-Tomato+ neurons from 13 mice. Red arrows indicate stimulation artifacts.

(B) Biocytin labeling showing vertical dendritic arborization of a biocytin-injected Dyn-Tomato+ neuron (arrow) and an uninjected Dyn-Tomato+ neuron (arrowhead) in lamina IIo.

(C) Schematics showing Dyn-Tomato+ neurons in lamina IIi and at II-III border (“1”) that receive Aβ input with strong feed-forward inhibition, and in laminae I-IIo (“2”) that receive Aβ input with AP output. Not shown are small subsets of types 1 and 2 cells located in I/IIo and at II-III border, respectively.

Dyn-Tomato+ Neuron Ablation leads to Aβ-evoked AP firing in Superficial Dorsal Horn Neurons

We next recorded randomly picked neurons located at different laminae under normal ACSF recording conditions in control and Dyn Abl mice. At the II-III border, neurons receiving Aβ inputs are increased from 66% (25/38) in control mice to 94% (32/34) in Dyn Abl mice (Chi-square test, p< 0.01; Figure 7A), and neurons generating Aβ-evoked APs are increased by 35%, from 5% (2/38) in control mice to 40% (12/30) in Dyn Abl mice (Chi-square test, p< 0.001; Figure 7A). Note that Aβ stimulation evoked fast EPSCs in all responsive neurons at the II-III border in both control and ablation mice, but slow EPSCs only in a subset of neurons in Abl mice (15%; 5/34). Thus, Dyn neurons are required to gate Aβ inputs onto a portion of II-III border neurons.

In laminae I and IIo, neurons receiving Aβ inputs are increased from 36% (32/89) in control mice to 83% (43/52) in Dyn Abl mice (Chi-square test, p< 0.001; Figure 7A). Moreover, Aβ stimulation only generated fast APs in 7% (5/69) of neurons in control mice, but can generate fast and/or slow APs in 76% (34/45) in Dyn Abl mice (Chi-square test, p< 0.001; Figure 7A). More surprisingly, 31% (16/52) of I-IIo neurons received monosynaptic Aβ inputs with AP firing, which was rarely observed in control mice (1%; 1/69; Chi-square test, p < 0.001). It should be noted that for control mice recorded in the presence of bicuculline/strychnine, Aβ stimulation mainly evokes slow, but not fast, AP firing in I/IIo neurons (see above, Figure 4). Thus, Dyn lineage inhibitory neurons provide two gating mechanisms for I/IIo neurons: (1) a bicuculline/strychnine-sensitive one that prevents slow Aβ-evoked AP firing, and (2) a bicuculline/strychnine-insensitive one that prevents fast Aβ-evoked AP firing.

Low Threshold Mechanical Stimuli Activate SOM+ Neurons in Dyn Abl Mice

We next tested whether low-threshold mechanical force can activate SOM+ pain transmission neurons upon ablation of Dyn-Tomato+ inhibitory neurons. To do this, we brushed one side of shaved back skin, and monitored the activation of spinal neurons by c-Fos induction. We found that this low-threshold brushing stimulus induced c-Fos in thoracic dorsal horn neurons of Dyn Abl mice, but rarely in control littermates (Figure 7B). Double immunostaining showed that 21.7 ± 3.4% of these c-Fos+ neurons showed detectable expression of the SOM peptide (Figure 7C), while the few c-Fos+ neurons in control mice showed almost no SOM expression (1.1 ± 1.1%). Thus, Dyn+ inhibitory neurons are required to prevent low-threshold mechanical stimuli from activating SOM+ pain transmission neurons (summarized in Figure 7D).

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that SOM lineage excitatory neurons, enriched in lamina II, are required to sense mechanical pain, but not thermal pain. SOM neurons are also part of polysynaptic circuits linking Aβ fibers to pain output neurons, and their ablation results in the loss of mechanical allodynia induced by inflammation or nerve lesions. Furthermore, we showed that Aβ input onto superficial dorsal horn neurons is gated through feed-forward activation of the Dyn lineage inhibitory neurons.

Lamina Organization in Transmitting Mechanical Pain-related Information

Dorsal horn neurons are organized into laminae (Rexed, 1952). Ascending projection neurons are enriched in laminae I and scattered throughout III-VI, whereas neurons in lamina II mainly belong to local interneurons (Braz et al., 2014; Todd, 2010; Willis et al., 2001). In a landmark study published in 1970, Christensen and Perl discovered that nociceptive neurons in lamina I either respond to noxious mechanical stimuli alone or are polymodal, responding to both noxious heat and mechanical stimuli (Christensen and Perl, 1970). Only a few spinothalamic projection neurons in lamina I respond selectively to noxious heat (Han et al., 1998). SOM-Tomato+ neurons are enriched in lamina II, with little overlap with NK1R+ lamina I ascending projection neurons. How then can mechanical pain be selectively lost following ablation of SOM neurons?

It should be noted that prior in vivo recordings have not been able to determine whether lamina I projection neurons receive mono- or polysynaptic inputs from primary afferents. In lamina II, neurons located in IIo and d-IIi predominantly receive nociceptive inputs, based on extracellular recording (Bennett et al., 1980; Cervero et al., 1979; Cervero et al., 1976; Christensen and Perl, 1970; Kumazawa and Perl, 1978; Light et al., 1979). Other studies indicate that vertical cells in IIo and d-IIi are the only output neurons that project their axons from lamina II to lamina I (Bennett et al., 1980; Gobel, 1978; Light et al., 1979; Lu and Perl, 2005; Molony et al., 1981; Price et al., 1979). We found that SOM neurons do include vertical cells (Figure S1E). Thus, mechanical nociceptors must transmit noxious mechanical information to lamina I projection neurons via lamina II SOM neurons (and/or those few SOM neurons scattered in laminae I and III-V) (Figure 2H), although it is not known whether SOM+ neurons connect with ascending projection neurons directly or indirectly. Furthermore, by comparing behavioral phenotypes of SOM versus Calb2 Abl mice, we reveal separate spinal neuronal populations transmitting light punctate versus intense noxious mechanical information (Figure S5L).

In contrast to the abolition of mechanical pain, SOM Abl mice show normal nocifensive responses to noxious heat and cold stimulation. Previous in vivo recordings showed that heat stimuli evoke firing in neurons located predominantly in lamina I/IIo and in lamina V, but only rarely in lamina II (Furue et al., 1999). The enrichment of SOM+ neurons in lamina II may explain why thermal pain is unaffected in SOM Abl mice, although our studies do not rule out a redundant role of SOM+ neurons in processing thermal information. The polymodal nature of lamina I and possibly lamina V neurons might be due to the convergence of direct inputs from heat fibers and indirect inputs from mechanosensitive nociceptors via lamina II SOM neurons. Thus, our studies gain insight into how different modalities of nociceptive information are transmitted through distinct dorsal horn laminae.

Identification of spinal circuits for a gate control of mechanical pain

The gate control theory postulates that spinal pain transmission (T) neurons receive inputs from both nociceptors and Aβ mechanoreceptors, with Aβ inputs gated through feed-forward activation of spinal inhibitory neurons (IN). Our data suggest that the SOM lineage of excitatory neurons and the Dyn lineage of inhibitory neurons represent the T and IN neurons, respectively. The original gate theory designates T cells as the ascending projection neurons, but our studies show that T neurons can be lamina II interneurons. We found that lamina II SOM+ neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from mechanical nociceptors, as well as Aβ inputs with feed-forward inhibition. Strikingly, ablation of SOM neurons leads to a virtual loss of Aβ fiber inputs onto the superficial dorsal horn. Consistently, chronic mechanical allodynia induced by inflammation or nerve lesions, which is partly caused by disinhibition that allows low-threshold mechanical stimuli to activate pain transmission neurons, is abolished in SOM Abl mice (Sandkühler, 2009; Woolf and Doubell, 1994; Zeilhofer et al., 2012). Several lines of evidence support the Dyn lineage neurons functioning as IN-type inhibitory neurons. Firstly, Aβ stimulation is able to evoke AP firing in a subset of Dyn neurons. Secondly, ablation of Dyn neurons leads to Aβ-evoked AP firing in most lamina I/II neurons, leading to spontaneous development of mechanical allodynia. It should be noted that the Dyn peptide has both pro-nociceptive and anti-nociceptive roles (Lai et al., 2006), and our data suggest that the net output of the Dyn lineage neurons is, however, inhibitory. The induction of c-Fos in SOM+ neurons by skin brushing in Dyn Abl mice, but not in control mice, suggests that Dyn inhibitory neurons normally acts to prevent low threshold mechanical stimuli from activating SOM+ pain transmission neurons.

Dyn neurons gate two polysynaptic excitatory circuits linking Aβ fibers to lamina I pain output neurons via lamina II SOM+ neurons. In pathway A (“A” in Figure 7D), Lu and others showed that Aβ fibers form monosynaptic connection to PKCγ+ excitatory neurons at the II-III border, which are in turn connected to lamina II transient central and vertical cells, and finally to lamina I projection neurons (Lu et al., 2013). These PKCγ+ neurons at the II-III border likely represent type 2 SOM-Tomato+ described in Figure 3 since both types of neurons receive Aβ inputs that is gated through bicuculline/strychnine-sensitive feed-forward inhibition (Lu et al., 2013), and such Aβ inputs are completely lost in SOM Abl mice. Lu et al further reported a ventrally located glycinergic inhibitory gate at the II-III border (Lu et al., 2013). Dyn+ neurons contribute to this ventral gate since 35% of II-III border neurons gain the ability to generate Aβ-evoked AP output in Dyn Abl mice. The degree of gate opening (35%) is, however, less than the 69% caused by bicuculline/strychnine treatment in control mice, indicating the existence of Dyn-independent ventral gates.

In pathway B (“B” in Figure 7D), Aβ fibers may provide direct inputs onto vertical cells located at IIo. Prior studies showed that IIo vertical cells send their dendrites ventrally, reaching the II-III border or even laminae III and IV (Bennett et al., 1980; Gobel, 1978; Light et al., 1979; Lu and Perl, 2005; Molony et al., 1981; Price et al., 1979). The presence of numerous spines in distal dendrites (Gobel, 1978) indicates that these neurons receive synaptic inputs from a region enriched with Aβ terminals, as confirmed by laser scanning photostimulation studies (Kato et al., 2009; Kosugi et al., 2013). This direct pathway likely depends on type 3 SOM neurons since these neurons include vertical cells (Figure S1E) and receive fast Aβ-evoked EPSCs (Figure 3B). However, to prevent pain from being evoked by innocuous mechanical stimuli, these vertical cells in IIo have to be gated, and we found that Dyn neurons are again involved. Indeed, to our surprise, Dyn neurons that receive Aβ input with AP output are mainly located in laminae I and IIo. Moreover, dorsally located Dyn neurons include vertical cells with ventrally projected dendrites, thereby placing them in a perfect position to receive direct Aβ inputs, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via type 1 SOM+ neurons), and feed-forwardly inhibit nearby vertical excitatory neurons (Figure 7D). Indeed, this direct Aβ-evoked pathway B becomes open in Dyn Abl mice, as indicated by 31% of lamina IIo neurons that gain the ability to receive fast monosynaptic Aβ inputs with AP firing. Interestingly, this Dyn-dependent dorsal gate is mediated through a mechanism that is insensitive to bicuculline/strychnine, thereby distinguishing it from the ventral gate that is sensitive to bicuculline/strychnine. Direct Aβ-evoked inhibitory inputs onto IIo nociceptive neurons can explain why Aβ stimulation has analgesic effects (Bini et al., 1984; Head, 1905; Salter and Henry, 1990; Wall and Sweet, 1967), a feature proposed by the original gate control theory (Melzack and Wall, 1965; Wall, 1978)

Concluding Remarks

This study gives us an opportunity to remember the wisdom articulated in the 1960s and 1970s by two late sensory titans: Patrick Wall and Edward Perl. The requirement of SOM neurons for sensing mechanical pain, but not touch or temperatures, supports the existence of specific pain-related circuits argued by Perl. The enrichment of SOM neurons in the substantia gelatinosa (Rexed’s lamina II) also suggests a critical role of this lamina in processing mechanical pain. SOM neurons are heterogeneous and further studies are warranted to determine if they transmit other modalities, such as mechanical itch. Meanwhile, the finding that SOM neurons receive Aβ inputs with feed-forward inhibition via Dyn inhibitory neurons supports the core argument of the gate theory proposed by Wall (and Melzack). Thus, pain is encoded through a hybrid mechanism that combines Perl’s specificity and Wall’s pattern theories, a mechanism recently referred to as the population coding theory (Ma, 2010, 2012; Prescott et al., 2014). Clinically, mechanical pain treatment represents a big challenge (Lolignier et al., 2014). Our study suggests that drugs targeted at reducing excitatory output from SOM neurons or enhancing inhibitory output from Dyn neurons could be ideally used to attenuate mechanical allodynia, without affecting the senses of temperature and touch that are vital for daily life.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Genetic Marking and Ablation of Spinal Neurons

The SOM, Tac2, Calb2, Dyn, ChAT and Npy lineage neurons in the dorsal spinal cord were labeled by crossing various Cre lines with the tdTomato report line. These Cre lines were then crossed with Tau-DTR and Lbx1-Flpo mice to drive DTR expression selectively in specific spinal lineage neurons. DTR-expressing neurons were ablated upon intraperitoneal injection with diphtheria toxin (DTX) at day 1 and day 4. Details of mouse lines and intersectional ablation could be found in the Extended Experimental Procedures.

In Situ Hybridization (ISH), Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

ISH and IHC (Liu et al., 2010) were performed using standard methods (see Extended Experimental Procedures).

Behavioral Testing

Surgery and behavior testing were performed as previously described (Knowlton et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2010). Sensorimotor coordination was measured by rotarod, innocuous touch sensations were measured using sticky tape and brushing assays, thermal sensations were measured by the Hargreaves, hot plate, cold plate, and acetone evaporation assays, and mechanical pain were measured by von Frey, pinprick, and pinch assays. Static allodynia was measured using von Frey assay, and dynamic allodynia was measured using the scoring system developed by Dr. Enrique José Cobos (see Extended Experimental Procedures for details).

Spinal Cord Slice Preparation, Patch Clamp Recording and Biocytin labeling

The lumbar spinal cord of mice (P23-P30) was removed and then sagittal spinal cord slices (350-500 μm) with dorsal roots (8-18 mm) attached were cut. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed. To reveal neuron morphology, biocytin was filled in the targeted neuron after a minimum of 20 min in the whole-cell, tight-seal patch-clamp configuration (see Extended Experimental Procedures for details).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. The p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically different (see Extended Experimental Procedures for details).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Z. Josh Huang and the Jackson laboratory for the SOM-IRES-Cre and Calb2-IRES-Cre mice, GENSAT and MMRRC at University of California, Davis for the NPY-Cre mice, the Allen Brain Institute and the Jackson Laboratory for the Rosa26LSL-tdTomato mice, and Dr. Susan Dymecki for the ROSA26CAG-FRT-STOP-FRT-GFP mice. We thank Drs. Yan Lu, Clifford Woolf, and Fu-Chia Yang for critical comments on the manuscript, Dr Yan Lu for his advice on spinal cord slice recording, and Dr. Enrique José Cobos for providing the scoring system in measuring dynamic allodynia. The Ma lab was supported by NIH grants (R01NS086372, NS047710 and P01 NS047572), the Goulding lab is supported by NIH grants (R01NS086372), and the Lowell lab was supported by NIH grants (R01 DK075632, R37 DK053477, R01 DK071051, R01 DK089044, R01 DK096010, P30 DK057521, and P30 DK046200). M.K. was supported by F32 DK089710. L.C. and Y.W. were supported by Grants from the Nature Science Foundation of China (81171224 and 81100815).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

B.D., S.B., W.K., and X.R. performed histochemical and behavioral analyses; L.C. performed electrophysiological recording; O.B., C.P., L.G., M.K., T.V., S.R., and B.B.L. provided unpublished mouse lines; Q.M., M.G. and Y.W. supervised the whole study; Q.M., B.D., L.C., S.B. and M.G. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abraira VE, Ginty DD. The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron. 2013;79:618–639. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Ataka T, Wakai A, Okamoto M, Woolf CJ. Removal of GABAergic inhibition facilitates polysynaptic A fiber-mediated excitatory transmission to the superficial spinal dorsal horn. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:818–830. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Abdelmoumene M, Hayashi H, Dubner R. Physiology and morphology of substantia gelatinosa neurons intracellularly stained with horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:809–827. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessou P, Perl ER. Response of cutaneous sensory units with unmyelinated fibers to noxious stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1969;32:1025–1043. doi: 10.1152/jn.1969.32.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bini G, Cruccu G, Hagbarth KE, Schady W, Torebjörk E. Analgesic effect of vibration and cooling on pain induced by intraneural electrical stimulation. Pain. 1984;18:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90819-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braz J, Solorzano C, Wang X, Basbaum AI. Transmitting pain and itch messages: a contemporary view of the spinal cord circuits that generate gate control. Neuron. 2014;82:522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno RM. Synchrony in sensation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PR, Perl ER. Myelinated afferent fibres responding specifically to noxious stimulation of the skin. J Physiol. 1967;190:541–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006;52:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JN, Raja SN, Meyer RA, Mackinnon SE. Myelinated afferents signal the hyperalgesia associated with nerve injury. Pain. 1988;32:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens EE, Carstens MI, Simons CT, Jinks SL. Dorsal horn neurons expressing NK-1 receptors mediate scratching in rats. Neuroreport. 2010;21:303–308. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328337310a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F, Iggo A, Molony V. An electrophysiological study of neurones in the Substantia Gelatinosa Rolandi of the cat’s spinal cord. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1979;64:297–314. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1979.sp002484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F, Iggo A, Ogawa H. Nociceptor-driven dorsal horn neurones in the lumbar spinal cord of the cat. Pain. 1976;2:5–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(76)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen BN, Perl ER. Spinal neurons specifically excited by noxious or thermal stimuli: marginal zone of the dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 1970;33:293–307. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymecki SM, Kim JC. Molecular neuroanatomy’s “Three Gs”: a primer. Neuron. 2007;54:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RTJ, Voglmaier S, Seal RP, Edwards RH. VGLUTs define subsets of excitatory neurons and suggest novel roles for glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furue H, Narikawa K, Kumamoto E, Yoshimura M. Responsiveness of rat substantia gelatinosa neurones to mechanical but not thermal stimuli revealed by in vivo patch-clamp recording. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 2):529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobel S. Golgi studies of the neurons in layer II of the dorsal horn of the medulla (trigeminal nucleus caudalis) J Comp Neurol. 1978;180:395–413. doi: 10.1002/cne.901800213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross MK, Dottori M, Goulding M. Lbx1 specifies somatosensory association interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord. Neuron. 2002;34:535–549. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZS, Zhang ET, Craig AD. Nociceptive and thermoreceptive lamina I neurons are anatomically distinct. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:218–225. doi: 10.1038/665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head H. the afferent nervous system from a new aspect. Brain. 1905;28:100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kato G, Kawasaki Y, Koga K, Uta D, Kosugi M, Yasaka T, Yoshimura M, Ji RR, Strassman AM. Organization of intralaminar and translaminar neuronal connectivity in the superficial spinal dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5088–5099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6175-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton WM, Palkar R, Lippoldt EK, McCoy DD, Baluch F, Chen J, McKemy DD. A sensory-labeled line for cold: TRPM8-expressing sensory neurons define the cellular basis for cold, cold pain, and cooling-mediated analgesia. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2837–2848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1943-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzenburg M, Lundberg LE, Torebjörk HE. Dynamic and static components of mechanical hyperalgesia in human hairy skin. Pain. 1992;51:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90262-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi M, Kato G, Lukashov S, Pendse G, Puskar Z, Kozsurek M, Strassman AM. Subpopulation-specific patterns of intrinsic connectivity in mouse superficial dorsal horn as revealed by laser scanning photostimulation. J Physiol. 2013;591(Pt 7):1935–1949. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.244210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes MJ, Shah BP, Madara JC, Olson DP, Strochlic DE, Garfield AS, Vong L, Pei H, Watabe-Uchida M, Uchida N, et al. An excitatory paraventricular nucleus to AgRP neuron circuit that drives hunger. Nature. 2014;507:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Perl ER. Excitation of marginal and substantia gelatinosa neurons in the primate spinal cord: indications of their place in dorsal horn functional organization. J Comp Neurol. 1978;177:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Luo MC, Chen Q, Ma S, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Porreca F. Dynorphin A activates bradykinin receptors to maintain neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1534–1540. doi: 10.1038/nn1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light AR, Trevino DL, Perl ER. Morphological features of functionally defined neurons in the marginal zone and substantia gelatinosa of the spinal dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:151–171. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Abdel Samad O, Duan B, Zhang L, Tong Q, Ji RR, Lowell B, Ma Q. VGLUT2-dependent glutamate release from peripheral nociceptors is required to sense pain and suppress itch. Neuron. 2010;68:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolignier S, Eijkelkamp N, Wood JN. Mechanical allodynia. Pflugers Arch. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1532-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Dong H, Gao Y, Gong Y, Ren Y, Gu N, Zhou S, Xia N, Sun YY, Ji RR, et al. A feed-forward spinal cord glycinergic neural circuit gates mechanical allodynia. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4050–4062. doi: 10.1172/JCI70026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Perl ER. Modular organization of excitatory circuits between neurons of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (laminae I and II) J Neurosci. 2005;25:3900–3907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0102-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. Labeled lines meet and talk: population coding of somatic sensations. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120:3773–3778. doi: 10.1172/JCI43426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. Population coding of somatic sensations. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantyh PW, Rogers SD, Honore P, Allen BJ, Ghilardi JR, Li J, Daughters RS, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Simone DA. Inhibition of hyperalgesia by ablation of lamina I spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1997;278:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar L, Yang FC, Ma Q. Genetic marking and characterization of Tac2-expressing neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system. Mol Brain. 2012;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R, Wall PD. The challenge of pain. Basic Books; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mendell LM. Constructing and deconstructing the gate theory of pain. Pain. 2014;155:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miraucourt LS, Dallel R, Voisin DL. Glycine inhibitory dysfunction turns touch into pain through PKCgamma interneurons. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SK, Hoon MA. The cells and circuitry for itch responses in mice. Science. 2013;340:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1233765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molony V, Steedman WM, Cervero F, Iggo A. Intracellular marking of identified neurones in the superficial dorsal horn of the cat spinal cord. Q J Exp Physiol. 1981;66:211–223. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1981.sp002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller T, Brohmann H, Pierani A, Heppenstall PA, Lewin GR, Jessell TM, Birchmeier C. The homeodomain factor Lbx1 distinguishes two major programs of neuronal differentiation in the dorsal spinal cord. Neuron. 2002;34:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00689-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordenbos W. Some historical aspects. Pain. 1987;29:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SA, Ma Q, De Koninck Y. Normal and abnormal coding of somatosensory stimuli causing pain. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nn.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, Hayashi H, Dubner R, Ruda MA. Functional relationships between neurons of marginal and substantia gelatinosa layers of primate dorsal horn. J Neurophysiol. 1979;42:1590–1608. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.6.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TJ, Cervero F, Gold MS, Hammond DL, Prescott SA. Chloride regulation in the pain pathway. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:149–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexed B. The cytoarchitectonic organization of the spinal cord in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1952;96:414–495. doi: 10.1002/cne.900960303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-da-Silva A, De Koninck Y. Morphological and neurochemical organization of the spinal dorsal horn (Elsevier) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Rossi J, Balthasar N, Olson D, Scott M, Berglund E, Lee CE, Choi MJ, Lauzon D, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. Melanocortin-4 receptors expressed by cholinergic neurons regulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;13:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Iwawaki T, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Noda M, Inui Y, Mekada E, Kimata Y, Tsuru A, Kohno K. Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:746–750. doi: 10.1038/90795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Henry JL. Differential responses of nociceptive vs. non-nociceptive spinal dorsal horn neurones to cutaneously applied vibration in the cat. Pain. 1990;40:311–322. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkühler J. Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:707–758. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardell TC, Polgár E, Garzillo F, Furuta T, Kaneko T, Watanabe M, Todd AJ. Dynorphin is expressed primarily by GABAergic neurons that contain galanin in the rat dorsal horn. Mol Pain Mol Pain. 2011;76 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YG, Zhao ZQ, Meng XL, Yin J, Liu XY, Chen ZF. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science. 2009;325:1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1174868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsiani D, Fu Y, Lu J, Lin Y, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsney C, MacDermott AB. Disinhibition opens the gate to pathological pain signaling in superficial neurokinin 1 receptor-expressing neurons in rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1833–1843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4584-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD. The gate control theory of pain mechanisms. A re-examination and re-statement. Brain. 1978;101:1–18. doi: 10.1093/brain/101.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PD, Sweet WH. Temporary abolition of pain in man. Science. 1967;155:108–109. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3758.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Eberhart D, Urban R, Meda K, Solorzano C, Yamanaka H, Rice D, Basbaum AI. Excitatory superficial dorsal horn interneurons are functionally heterogeneous and required for the full behavioral expression of pain and itch. Neuron. 2013;78:312–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WDJ, Zhang X, Honda CN, Giesler GJJ. Projections from the marginal zone and deep dorsal horn to the ventrobasal nuclei of the primate thalamus. Pain. 2001;92:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Doubell TP. The pathophysiology of chronic pain--increased sensitivity to low threshold A beta-fibre inputs. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:525–534. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Lopes C, Wende H, Guo Z, Cheng L, Birchmeier C, Ma Q. Ontogeny of excitatory spinal neurons processing distinct somatic sensory modalities. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14738–14748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5512-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasaka T, Tiong SY, Hughes DI, Riddell JS, Todd AJ. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain. 2010;151:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Nishi S. Primary afferent-evoked glycine- and GABA-mediated IPSPs in substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;482(Pt 1):29–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer HU, Wildner H, Yévenes GE. Fast synaptic inhibition in spinal sensory processing and pain control. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:193–235. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.