Summary

Compared to xenografts from previously established cell-lines, patient-derived xenografts may more faithfully recapitulate the molecular diversity, cellular heterogeneity, and histology seen in patient tumors, although other limitations of murine models remain. The ability of these models to inform clinical development and answer mechanistic questions will determine their ultimate utility.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Julien et al provide a detailed description of an extensive body of work in patient-derived xenografts from colorectal cancer patients(1). Like many efforts described by Robert Burns’ famous line in his poem “The Mouse”, the ultimate success of “The best laid plans of mice and men” remains to be seen. In contrast to the most commonly utilized cell line xenograft model, patient-derived xenografts are established from the immediate transfer of fresh tumor tissue from patients into immunosuppressed mice. After a period of stagnant or indolent growth, these xenografts enter a logarithmic growth phase suitable for harvesting and reimplantation in successive generations of mice with a high tumor take rate. An enlarging body of work suggests patient-derived xenografts may represent an informative model for development of novel therapeutics, with the hope that they can more faithfully predict the subsequent clinical success and allow mechanistic studies of agent action that are not possible in patients themselves. To fully utilize the potential of this approach, however, fundamental model development steps such as those rigorously described by Julien et al. will be needed in a variety of tumors(1, 2).

The limitations of current preclinical models have been well described and are increasingly cited as a key cause of the low success rate of oncology drug development(3). Historically, panels of cell lines, many dating back decades, have been utilized to screen novel therapeutics for clinical activity and select tumor subtypes for further exploration. In vivo studies will commonly utilize a small subset of these cell line panels in order to identify tumor types of interest and to make "go-no go" decisions for drug development. Previous coordinated efforts have been undertaken to improve the predictive nature of these preclinical studies, as exemplified by spheroid studies which ultimately have not improved preclinical predictions.

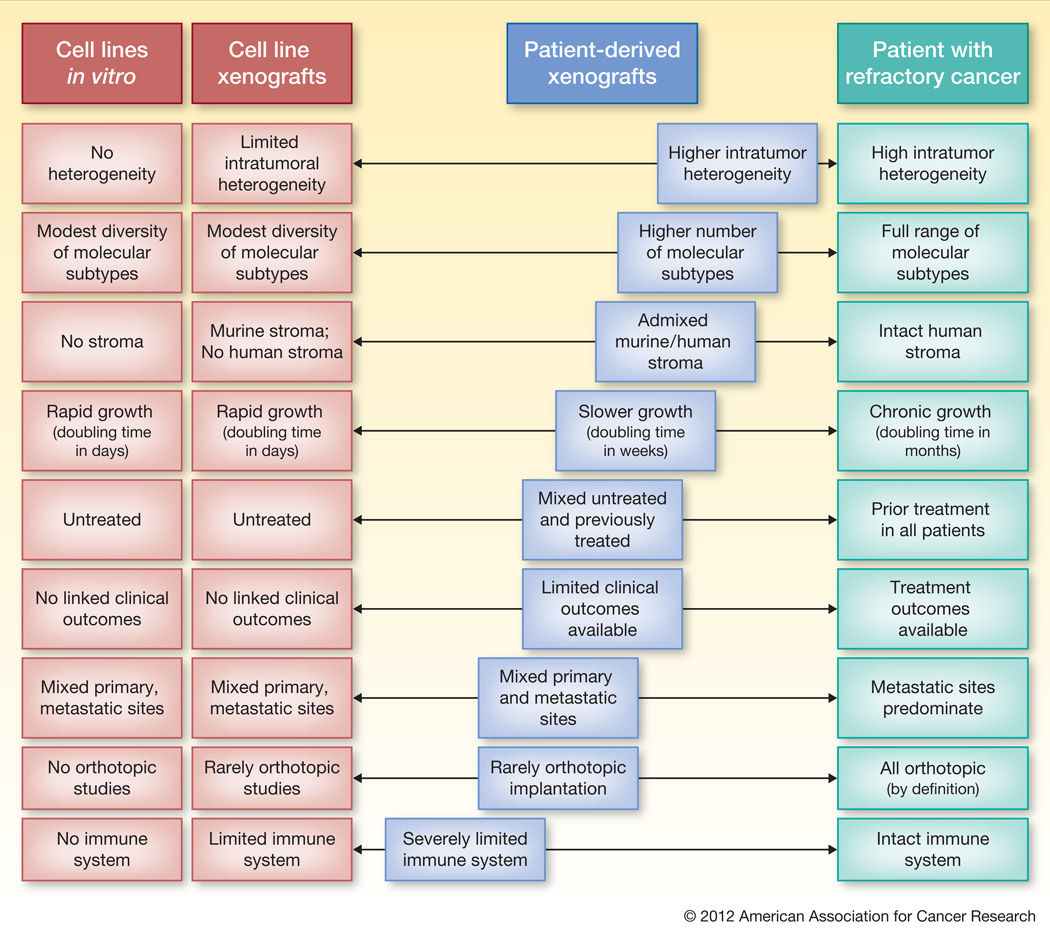

Increasingly over the past several years, patient-derived xenografts, or tumorgrafts, have been utilized for proof of concept studies(4). Ultimately the success of this model will come with time as it is integrated into development of novel therapeutics. Several characteristics suggest these models made better recapitulate the human model. A review of the features of the patient derived xenografts that most closely resemble this patient model is instructive to understand the strengths and weaknesses of this approach. (Figure)

Figure.

Cell line based models have been criticized for their poor ability to predict outcomes for advanced cancer patients(3). Patient-derived xenografts have several characteristics that better recapitulate the clinical reality for patients. This tumor model “abacus” highlights areas of strength and weakness of patient-derived xenografts compared the cell line and human models. Blue squares further to the right represent positive characteristics of the patient-derived xenografts that are closer to the tumor biology of the patient.

The most commonly cited benefit of the patient derived xenograft model is the maintained intra-tumor heterogeneity and histologic characteristics seen in primary tumors. Cell lines, and by extension cell line xenografts, undergo extensive evolutionary selection through years of growth in monolayers and rarely recapitulate the histology of parental tumors when reimplanted. While studies, including the one presented in this issue, demonstrate the sustained histologic features over time, it is unclear whether the molecular heterogeneity seen in early passages of the tumor will be maintained over subsequent generations. Earlier studies of in vitro colony-formation from patient tumors failed to provide clinical relevance, which was attributed in part to the survival of only the most aggressive tumor clones(5).

The second key and frequently cited feature is the ability to maintain a component of human stroma in early passages. Detailed evaluation of the stromal component, however, suggests that there is less stroma in the early passage tumors than is seen in parental tumor, but that this tumor to stromal ratio is sustained with subsequent passages. Eventually the human stroma is replaced by stroma of murine origin, although the timing of this remains to be further clarified. While there is evidence that the human-derived xenograft can be partially supported by murine stroma, there are key differences in the ligand repertoire that may be critical to the tumor phenotype. Gene expression profiles from early and late passage xenograft reflect these changes in stromal characteristics, but also provide unique research opportunities to differentiate tumor and stromal compartments through dedicated murine and human arrays.

Cancer cell lines have been criticized for their modest diversity of molecular subtypes and skewing towards subtypes of increased affinity to growth in a monolayer and culture. Profiling of tumors using the blunt metrics of mutational frequency in this colorectal cancer xenograft set suggests that a more complete spectrum of molecular subtypes may be present. For example, tumors with a PI3KCA mutant and KRAS/BRAF wild-type genotype were successfully established – although this subtype is exceedingly rare in the available colorectal cancer cell lines(6). However for other tumor types with lower overall engraftment rates there may be substantial biases induced in the biology of those tumors that can be established. In addition further molecular profiling beyond mutation spectrum will be required to characterize these xenograft tumor banks.

Several current limitations of the patient-derived xenograft model as currently implemented can be addressed to better recapitulate patients with refractory and metastatic cancer. Many patient-derived xenografts are established from the primary tumors of previously untreated patients and thereby fails to reproduce a chemotherapy-refractory patient population in whom most novel therapeutics will undergo their initial trials(7). While several series, including the current bank of colorectal cancer xenografts described in this issue, are partially composed of tumors from metastatic sites, these reflect uncommon patients with oligo-metastatic disease who underwent potentially curative surgical resection. Instead of relying on surgical specimens, biopsy samples can be engrafted, thereby extending the application of the model to a wider range of patients and improving the ability to study changes in the tumor at a time when clinical resistance develops. Concerted efforts, including development of methods to reproducibly engraft biopsy samples will be needed to improve the clinical applicability of the xenograft panels.

The critical limitation of either cell line or patient-derived xenografts is the requirement to utilize immunosuppressed mice. As an increasing number of clinical questions incorporate immune-based therapies, alternate models will need to be pursued. In addition several well-established limitations of murine models remain, including the imperfect modeling of drug distribution and metabolism, and a more rapid tumor growth rate than is seen in most cancer patients. Implantation of these tumors into the same organ from which they were harvested may improve the clinical relevance of these models but will require optimized methodology for labeling and imaging these tumors(8, 9).

The development of the patient-derived xenograft models also introduce potential logistic challenges including assessment of the ability to freeze and reestablish tumors after months to years of storage, and the minimization of warm ischemia time in more complex surgical resections. Close coordination with the surgeons and implantation of the specimens as rapidly as possible after devascularization of the specimen improves engraftment rates and may be increasingly critical for tumors with low-engraftment rates.

Efforts to pair the clinical outcomes from patients and the response of the corresponding xenografts have shown early success(10, 11). While the clinical utility of prospective efforts will be hampered by the time-frame required for such testing, the variable engraftment rates, and potential regulatory hurdles, it remains an important proof-of-principle for the ability of xenograft to predict efficacy of novel therapeutics. Ultimately, validation of this approach will come with successful selection of important biology amenable to pharmaceutical intervention and the corresponding ability to reduce early drug development failures. Only then will we finally disprove the conclusion of Burns’ poem: “The best laid plans of mice and men / Often go awry.”

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: CA136980 (SK), CA95060 (SK, GP) and a gift from the Perot Foundation (G.P.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of relevance

References

- 1.Julien S, Merino-Trigo A, Lacroix L, Pocard M, Goere D, Mariani P, et al. Characterization of a large panel of patient-derived tumor xenografts representing the clinical heterogeneity of human colorectal cancer. Clin Can Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0372. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim MP, Evans DB, Wang H, Abbruzzese JL, Fleming JB, Gallick GE. Generation of orthotopic and heterotopic human pancreatic cancer xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1670–1680. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis LM, Fidler IJ. Finding the tumor copycat. Therapy fails, patients don't. Nat Med. 2010;16:974–975. doi: 10.1038/nm0910-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fichtner I, Slisow W, Gill J, Becker M, Elbe B, Hillebrand T, et al. Anticancer drug response and expression of molecular markers in early-passage xenotransplanted colon carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney DN, Winkler CF. In vitro assays of chemotherapeutic sensitivity. Important Adv Oncol. 1985:78–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihle NT, Powis G, Kopetz S. PI-3-Kinase inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:190–198. doi: 10.2174/156800911794328448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MP, Truty MJ, Choi W, Kang Y, Chopin-Lally X, Gallick GE, et al. Molecular profiling of direct xenograft tumors established from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(Suppl 3):395–403. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1839-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troiani T, Schettino C, Martinelli E, Morgillo F, Tortora G, Ciardiello F. The use of xenograft models for the selection of cancer treatments with the EGFR as an example. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suetsugu A, Katz M, Fleming J, Truty M, Thomas R, Saji S, et al. Imageable fluorescent metastasis resulting in transgenic GFP mice orthotopically implanted with human-patient primary pancreatic cancer specimens. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1175–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeRose YS, Wang G, Lin YC, Bernard PS, Buys SS, Ebbert MT, et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nat Med. 2011;17:1514–1520. doi: 10.1038/nm.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hidalgo M, Bruckheimer E, Rajeshkumar NV, Garrido-Laguna I, De Oliveira E, Rubio-Viqueira B, et al. A pilot clinical study of treatment guided by personalized tumorgrafts in patients with advanced cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1311–1316. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]