Abstract

Objective

To analyse gene expression patterns and to define a specific gene expression signature in patients with the severe end of the spectrum of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). The molecular consequences of interleukin 1 inhibition were examined by comparing gene expression patterns in 16 CAPS patients before and after treatment with anakinra.

Methods

We collected peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 22 CAPS patients with active disease and from 14 healthy children. Transcripts that passed stringent filtering criteria (p values ≤ false discovery rate 1%) were considered as differentially expressed genes (DEG). A set of DEG was validated by quantitative reverse transcription PCR and functional studies with primary cells from CAPS patients and healthy controls. We used 17 CAPS and 66 non-CAPS patient samples to create a set of gene expression models that differentiates CAPS patients from controls and from patients with other autoinflammatory conditions.

Results

Many DEG include transcripts related to the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses, oxidative stress, cell death, cell adhesion and motility. A set of gene expression-based models comprising the CAPS-specific gene expression signature correctly classified all 17 samples from an independent dataset. This classifier also correctly identified 15 of 16 postanakinra CAPS samples despite the fact that these CAPS patients were in clinical remission.

Conclusions

We identified a gene expression signature that clearly distinguished CAPS patients from controls. A number of DEG were in common with other systemic inflammatory diseases such as systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The CAPS-specific gene expression classifiers also suggest incomplete suppression of inflammation at low doses of anakinra.

INTRODUCTION

Autoinflammatory diseases are characterised by episodic attacks of systemic inflammation without an infectious trigger and by the lack of auto-antibodies or antigen-specific, autoreactive T cells in peripheral blood.1

The cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), also known as the cryopyrinopathies, include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (MIM120100), Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS; MIM191900), and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID/CINCA; MIM607115). CAPS patients present with overlapping and variable degrees of systemic inflammation ranging from the milder familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome to the more severe NOMID/CINCA. NOMID/CINCA patients have an early onset of systemic inflammation as manifested by fever, urticaria-like rash, a characteristic arthropathy and central nervous system (CNS) inflammation.

The cryopyrinopathies are caused by dominantly inherited or de novo missense mutations in NLRP3, a gene that encodes NLRP3 (also known as cryopyrin). However, NLRP3 mutations are not identified in all patients, suggesting genetic heterogeneity. Cryopyrin is a part of an intracellular multiprotein complex, the inflammasome, which regulates host defence by activating caspase-1, also known as the interleukin (IL) 1β converting enzyme.2,3 The animal model and in-vitro studies have established that the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in response to a variety of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and danger-associated molecular patterns. However, as of yet, the final common signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome—if such a common signal actually exists—has not been definitely identified.4 The double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase has recently been implicated in the activation of inflammasome.5 In-vitro studies suggest that cryopyrin mutations are gain of function and result in the mutant protein being constitutively active. Cultured monocytes from NOMID and MWS patients show an ATP-independent increase in IL-1β and IL-18 secretion and accelerated IL-1β secretion.3,6–8 Targeted therapy of CAPS patients with IL-1 inhibitors causes a rapid and dramatic improvement of clinical symptoms accompanied by a decrease in acute phase reactants.9–12 Although the patients are clinically much improved, it remains a question as to whether current doses of IL-1 inhibitors completely suppress the inflammation at the cellular level.

To understand the pathogenesis of systemic inflammation better, we sought to identify genes with expression significantly altered in CAPS patients relative to healthy controls, and to compare these differentially expressed genes (DEG) to those expressed in patients with other systemic inflammatory diseases. Gene expression patterns in paired samples from NOMID/MWS patients before and after treatment with anakinra were analysed to identify transcripts responsive to IL-1 inhibition. In addition, we developed a specific, model-based, gene expression signature that can accurately distinguish CAPS patients from patients with other types of systemic inflammation and healthy controls, even when the CAPS patients were treated with suppressive doses of anakinra.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Sample collection and processing

Blood samples were obtained from 66 patients with systemic autoinflammatory syndromes (23 CAPS, 29 tumour necrosis factor receptor 1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), eight hyper IgD syndrome (HIDS), six pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and cystic acne (PAPA) and 20 healthy adult controls. All blood specimens were processed within 60 min of drawing to minimise ex-vivo changes in gene expression. The clinical features of NOMID/CINCA patients have been described in another study.10 In addition, RNA samples from 14 paediatric patients were utilised in the CAPS versus control analysis (figure 1) and in the predictive model building. For participation in the study all patients (or parents/legal guardians of minors) provided written informed consent as approved by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases institutional review board.

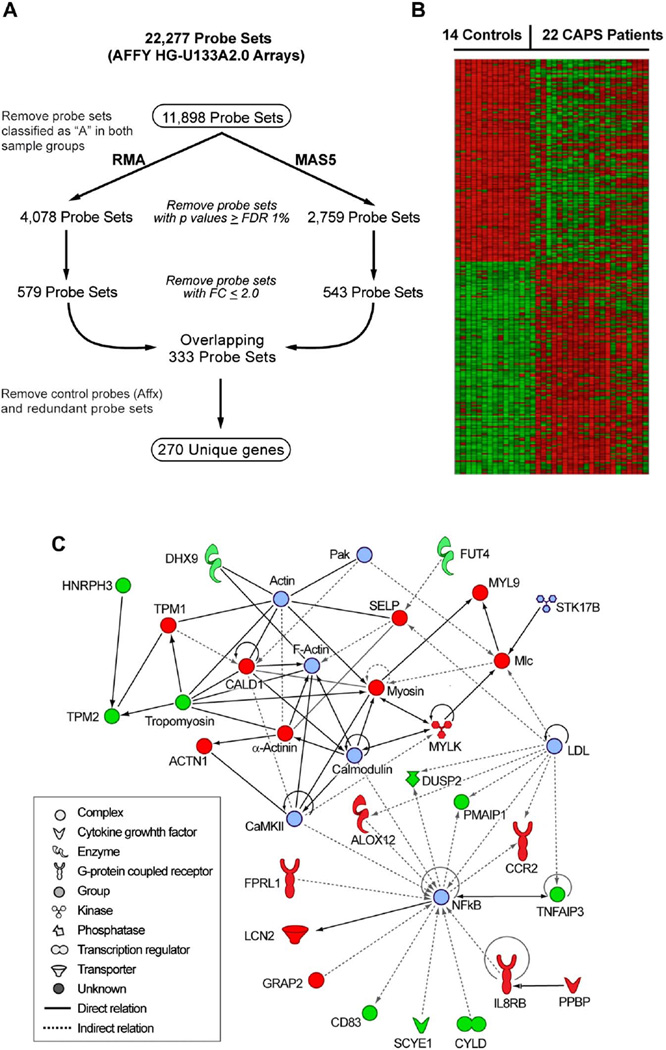

Figure 1.

Genes that are differentially expressed (DEG) in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) patients relative to controls. (A) Workflow used to establish 270 DEG in 22 CAPS patients relative to 14 healthy individuals. (B) Heatmap depicting these 270 DEG. Expression values are normalised per gene to the average expression value of the 14 healthy controls. Data were parsed into five bins. The heatmap was generated using HeatMap Builder V.1.0. (C) Functional interactome depicting known relationships among a subset (n=27) of the 270 DEG. Red and green shapes denote genes that are upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in CAPS patients relative to controls, whereas light blue shapes were not differentially expressed but were introduced by the software to maximise functionality among these 35 focus molecules (nodes).

Experimental details

Experimental details on RNA sample preparation, microarray procedures and data analysis, gene expression modelling, quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)–PCR, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and TXNIP experiments are available in the supplementary Materials and methods (available online only).

RESULTS

Differentially expressed genes in CAPS patients versus healthy controls

We compared gene expression patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from 22 mostly paediatric patients with NOMID or MWS during active disease (ie, before treatment with anakinra) to those from 14 healthy children. The disease activity score was high in all CAPS cases at the time of sample collection as indicated by the diary score, elevated sedimentation rate (mean 44 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (mean 4.6 mg/dl) (see supplementary table S1, available online only). All patients presented with evidence of current or previous CNS disease at the time of sampling.

Among the 22 NOMID/MWS patients were two mutation-negative patients who were clinically diagnosed as having NOMID and who responded to anakinra therapy. Data analysis was performed as outlined in figure 1A. A set of 270 unique genes was derived from overlapping the RMA and MAS5 gene lists that resulted after removing transcripts with a fold change (FC) between 2.0 and −2.0, and with a p value ≤ false discovery rate 1% (see supplementary table S2, available online only). Analysis of variance showed disease status as the major source of variation in this dataset and argued against major confounding variables, such as age and processing/batch effects. Approximately equal numbers of genes were identified as downregulated (n=134) and upregulated (n=136) in CAPS patients relative to healthy controls (figure 1B). Examination of the 270 DEG in functional gene networks identified the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signalling pathway as the most significant network (figure 1C).

Genes involved in regulation of innate and adaptive immunity

The stringent list of 270 DEG included a number of transcripts related to the regulation of immune processes, inflammation, cell adhesion and motility. As expected, we found the transcription of many cytokines, chemokines and their receptors to be highly upregulated in CAPS patients. Some of them did not meet the criteria for the most stringent list of 270 DEG (IL-1β (FC=2.25, p=0.005); IL-1R2 (FC=3, p=0.02); IL-1RN (FC=1.76, p=0.008), but independent validation of these microarray results in the same cohort of patients was previously reported.10 The gene expression of the known markers of neutrophilic inflammation, IL8RB (FC=3.6, p=0.0006) and S100A12 (FC=2.23, p=0.0001), and the chemokine receptor CCR2 (FC=2.36, p=1 × 10−5) were found to be highly upregulated in PBMC from CAPS patients. The autocatalysis of caspase-1 following ATP-induced activation of the nucleotide receptor, P2×7, requires the efflux of potassium ions from the cell via potassium channels, including KCNJ15.13 The transcription of KCNJ15 was highly upregulated in CAPS patients (FC=7.3, p=6×10−5) as well as in PBMC from patients with a similar disease, systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA).14 The elevated expression of two G-protein coupled receptors, FPR1 and FPRL1, which mediate chemotaxis, degranulation and superoxide production in mammalian phagocytic cells, was validated using qRT–PCR (see supplementary figure S1A, available online only). One of the significantly downregulated genes, CYLD, encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme known to repress the activation of NF-κB by specific tumour necrosis factor receptors.15,16 The IL1RN is known to decrease the expression of human CYLD messenger RNA,16 thus CYLD is probably downregulated in CAPS patients as a result of the compensatory upregulation of endogenous IL-1Ra.

Although autoinflammatory diseases are mediated by neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, we found that several DEG encoded markers characteristic of cells involved in adaptive and humoral immunity (GRAP2, CD69, CD83, CLEC1B, CLEC2D, PTCRA, TRA, RGS1). The maturation of CD4 lymphocytes depends on the leukocyte-specific adaptor protein GRAP2 (FC=2.86 p=8×10−6), which is important for T cell receptor signalling. The CD69 expression is induced on activation of T cells. CD83 is expressed on dendritic cells, which are considered to be part of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. CLEC1B, CLEC2D encode C-type lectin receptors expressed in myeloid and natural killer cells, and are thought to act as innate immune receptors. PTCRA and TRA are T cell-specific genes, which regulate T cell development.

Genes regulating bone biology

The network analysis of 270 DEG identified a cluster of genes regulated by the JUN (AP1) transcription factor, which is known to be downstream of IL-1. The downregulation of JUN has been associated with osteopetrosis due to impaired osteoclastogenesis in mice, while in-vitro blockade of c-Jun signalling inhibited soluble RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation.17 Although we have not observed a statistically significant difference in the JUN expression between five (four NOMID, one NOMID/MWS) patients with a bony overgrowth versus 17 patients who did not present with a bony overgrowth, the downregulation of JUN (see supplementary table S2, available online only) could play a role in the bony overgrowth in NOMID patients. We also identified DEG related to bone morphogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation, BMP6 and SPARC (osteonectin). BMP-6 is a growth factor produced by bone marrow mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells and is important for the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts, chondrocytes and other cells.18 Based on our data, the bone pathology in CAPS patients may be at least in part mediated by infiltrating inflammatory cells (PBMC). It is also possible that CAPS patients with the bone pathology may carry susceptibility alleles in other genes that are necessary to develop this disease complication. Our finding implicates genes of the JUN pathway as possible candidates.

Transcription of ROS-associated genes

ROS, generated by NADPH oxidase, have been implicated as a possible common signal for the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in rats and mice.19,20 It has also been shown that the ROS-producing mitochondria are essential for the NLRP3 inflammasome activation in THP1 cells and in Nlrp3−/− bone-marrow-derived macrophages.21 Unstimulated CAPS monocytes have an altered basal redox state and produce a significantly higher level of ROS than healthy donors or patients with SoJIA.22 However, more recent data suggested the role for ROS in priming the expression of NLRP3 and not in the direct activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.23 The microarray data from CAPS patients versus healthy controls identified the altered expression of genes associated with the generation and propagation of ROS signalling (GPX1, GUCY1B3, NDUFA5). We then investigated the expression of genes that are known to be involved in the ROS signalling pathway by qRT–PCR (see supplementary figure S1A, available online only). The expression of the integral membrane subunit of NADPH oxidase, p22-phox (CYBA), and one of the cytosolic components, p40-phox (NCF4), were found to be upregulated in CAPS patients compared to controls, along with the expression of TXN and SOD2, which encode the ROS detoxifying proteins thioredoxin and superoxide dismutase 2, respectively. In contrast, the expression of TXNIP, a TXN-interacting protein hypothesised to be a ROS-sensitive NLRP3 ligand and activator, was significantly downregulated in CAPS patients relative to controls (see supplementary figure S1A, available online only).24 To validate the TXNIP gene expression data we evaluated the protein expression in cultured macrophages from CAPS patients. Although the protein data were in agreement with the microarray data in three out of four mutation-positive patients, we were not able to draw a meaningful conclusion (see supplementary figure S1B, available online only). The one mutation-positive patient with increased TXNIP expression had more active disease when sampled than the other three patients. In contrast, two mutation-negative MWS patients had protein expression similar to control samples. The downregulation of TXNIP (VDUP1) is probably a compensatory mechanism to counterbalance the constitutively active NLRP3 inflammasome in CAPS patients.

We used dihydrorhodamine 123 to measure the total oxidative capacity in patient cells and found a small but statistically significant increase in ROS production both in unstimulated and PMA-stimulated cells (see supplementary figure S1C, available online only).25 All the patients were on treatment with anakinra at the time of sampling their cells. Our study suggests that cellular ROS production probably helps propagate the continuous IL-1β-mediated systemic inflammation triggered by autocrine feedback loops.

The transcriptional changes of α-synuclein

CAPS patients present with CNS disease mediated by IL-1β-induced inflammation. Although low levels of CIAS1 were detected in the brain, it is unclear, as it is in chondrocytes, whether IL-1β is produced locally by CNS cells or by infiltrating inflammatory cells. α-Synuclein (SNCA) is primarily expressed in brain tissue; however, the SNCA mRNA and protein (α-syn) was increased in lipopolysaccharide and IL-1β-stimulated cultured human macrophages,26 and the transcription of SNCA appears high in unstimulated human granulocytes (see supplementary figure S2, available online only). α-Syn may play a role in amplification of the inflammatory process following activation of microglia (the innate immune cells in CNS) with lipopolysaccharide and on secretion of various proinflammatory cytokines.27 Our findings (see supplementary table S2 and figure S2, available online only) suggest that the function of α-synuclein is not exclusive to the CNS and that the expression of α-synuclein may modulate inflammatory responses in PBMC and in granulocytes.

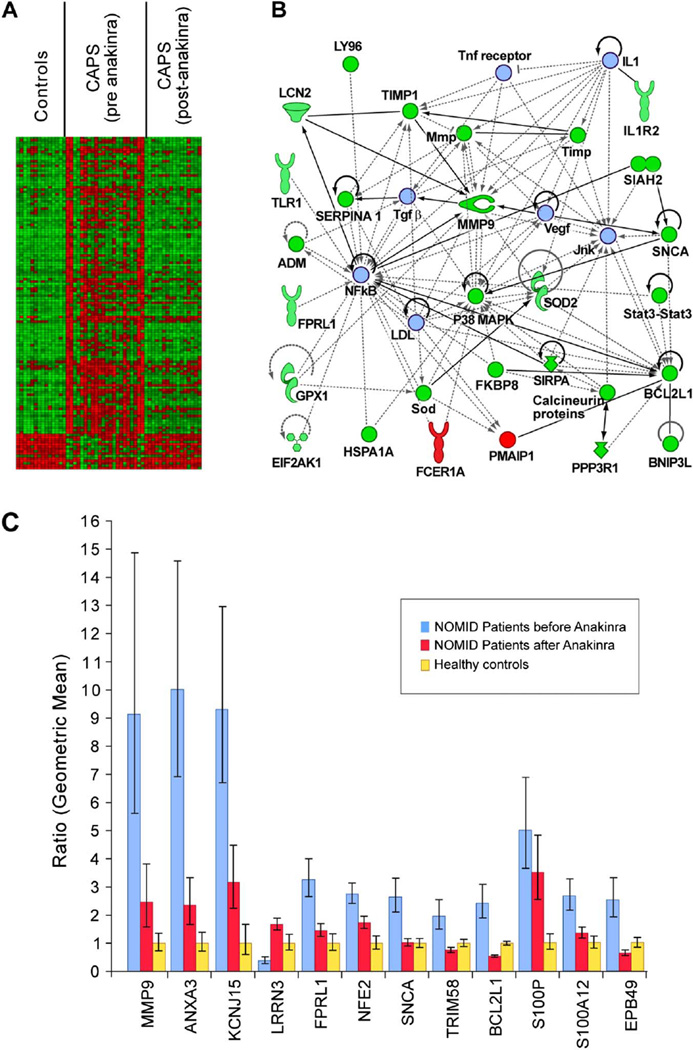

The transcriptional effect of anakinra treatment

The ability of anakinra to modulate gene expression was investigated on comparison of 16 paired PBMC samples collected before and after treatment. We identified 263 anakinra-responsive transcripts using a filtering approach detailed in supplementary figure S3 (available online only). The statistical power inherent in paired samples analyses required more relaxed filtering criteria than applied in figure 1A. To minimise further the number of false positives, we overlapped these 263 transcripts with the gene list generated from the CAPS versus controls analysis using the same criteria for the analysis of paired samples (false discovery rate 10%; FC ≥1.4 or ≤1.4). One hundred and forty unique genes remained in the merged dataset (see supplementary figure S3 and table S3, available online only). The majority of the DEG were downregulated as one would expect based on the reduction of inflammatory symptoms observed with the treatment (figure 2A). Pathway analysis showed that many of the anakinra-responsive genes are associated with P38 MAPK, NF-κB and MMP9 pathways (figure 2B). We validated a set of the DEG by qRT–PCR in CAPS samples and healthy controls. We confirmed three genes (MMP9, ANXA3, KCNJ15) as particularly highly expressed in untreated CAPS samples (figure 2C). The expression of MMP9, ANXA3, KCNJ15, S100P and NFE2 was downregulated by IL-1β blockade but not completely normalised to levels observed in healthy individuals.

Figure 2.

The transcriptional effects of anakinra therapy. (A) Heatmap depicting the top 140 genes (see supplementary figure S2, available online only), the expression of which is significantly altered by anakinra treatment and that are differentially expressed in CAPS patients relative to healthy controls. The gene expression data for each individual were normalised per gene to the average expression value of the 14 controls. For visualisation the data for each probe set were routed to 10 equal bins (row-based normalisation) using a linear colour gradient from green (lowest value) to red (highest value). Each row represents one gene and each column represents one biological replicate array. (B) Functional interactome depicting direct and indirect relationships that are known to exist among a subset (n=28) of the 140 genes that best characterise the transcriptional response to anakinra in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) patients. Red and green shapes denote genes that are upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in CAPS patients before treatment with anakinra. The seven molecules represented by light blue shapes were not differentially expressed but were introduced by the software to maximise functionality among these 35 focus molecules. The shapes are as depicted in the figure1C legend. (C) The relative expression of 10 genes determined to be anakinra responsive by microarray was validated by quantitative reverse transcription PCR in CAPS patients before (blue bars) and after (red bars) anakinra treatment and in healthy controls (yellow bars). The blue and red bars represent the average fold change in CAPS patients before anakinra and after anakinra, respectively, after normalising the average value in healthy controls (yellow bars) to 1. Error bars and fold-change calculations are as described in figure 2A. All genes are significantly differentially expressed (p<0.05) in CAPS patients compared to controls and in CAPS patients before treatment with anakinra compared to controls and not in CAPS patients after initiating anakinra treatment compared to controls with the exception of BCL2L1, which appears to be over-normalised by anakinra (ie, significant when CAPS patients after initiating anakinra treatment are compared to controls).

Gene expression signature in CAPS patients

We used a supervised linear computer algorithm, LDA, to construct gene expression classifiers (see supplementary Materials and methods, available online only). Individual samples were randomly selected from each group and assigned to training (17 CAPS; 66 non-CAPS comprising 30 healthy controls, 25 TRAPS, six HIDS, five PAPA) and test datasets (six CAPS; 11 non-CAPS comprising four healthy controls, four TRAPS, two HIDS, one PAPA) to test the performance of the classifiers.

Using the training set we constructed nine classifiers (models), each consisting of 10 independent variables (non-redundant genes) (see supplementary table S4, available online only). The accuracy of our classification scheme was evaluated by full leave one out crossvalidation (LOOCV), in which a model was completely rebuilt without the removed sample, and by testing our models in the independent test set using a simple voting scheme. The voting scheme was applied to take advantage of the multiple models to achieve a high level of prediction accuracy. The class assignments from the nine models were averaged to determine the majority classification of each sample (see supplementary table S5, available online only). The overall average classification rate from LOOCV validation was 92.8%, with 77 out of 83 training samples being correctly classified. While model no. 1 is the best predictor of class assignment in LOOCV, the multimodel voting approach outperforms all of the independent models in predicting class assignment of the samples from the independent test datasets. In particular, only the combined model voting approach was correct in classifying all 17 samples in the test set (table 1), which included two mutation-negative NOMID patients.

Table 1.

Results from deploying Models on an independent test set of 17 samples

| Class prediction | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | No. correct | Overall | |

| 1 | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | 9/9 | CAPS |

| 2 | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | 7/9 | CAPS |

| 3 | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | 9/9 | CAPS |

| 4 | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | 6/9 | CAPS |

| 5 | CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | 7/9 | CAPS |

| 6 | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | 6/9 | CAPS |

| 1 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 2 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 3 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | 8/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 4 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 5 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 6 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 7 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 8 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | 9/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 9 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | 6/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 10 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | 6/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 11 | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | Non-CAPS | CAPS | Non-CAPS | 7/9 | Non-CAPS |

| 16/17 | 16/17 | 15/17 | 15/17 | 14/17 | 16/17 | 15/17 | 12/17 | 15/17 | 17/17 | |||

CAPS, cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes.

The set of nine models correctly classified all but one of 16 CAPS samples obtained after treatment with anakinra (see supplementary table S6, available online only), raising the question as to whether there is still some level of residual IL-1 activity and inflammation not being suppressed by anakinra.

The canonical pathway analysis of 90 genes comprising the CAPS gene expression signature identified inducible costimulator (also known as activation-inducible lymphocyte immunomediatory molecule) and nuclear factor of activated T cells as the most significant pathways by p value (see supplementary table S7, available online only).

DISCUSSION

This study examines the gene expression profiles in untreated CAPS patients relative to healthy controls. DEG include transcripts involved in the regulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses, and other cellular processes such as oxidative stress and apoptosis. We show that the transcription of many genes is significantly altered in PBMC from NOMID/MWS patients with active disease. The network analysis of DEG identified the major network centred on NF-κB, which is in concordance with the observation that IL-1 is a known inducer of NF-κB28 and with a study showing that NF-κB plays a major role in the priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome.29 Genes regulated by IL-1 inhibition were examined by comparing gene expression patterns in paired samples of CAPS patients before and after treatment with anakinra. Our data suggest that the level of treatment used in these patients (at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg of anakinra per day) was insufficient to suppress inflammation.

To establish whether the stringent list of 270 DEG that distinguish CAPS patients from controls (figure 1) is legitimate, we compared our gene list to the published profiles for PBMC of patients with SoJIA compared to controls. Fifty-five unique genes (marked by * in supplementary table S2, available online only) were differentially expressed in both CAPS and SoJIA patients.30 Comparison of the 333 probe sets, representing the top 270 genes that are upregulated in CAPS patients, to the 305 probe sets upregulated in SoJIA patients with active versus inactive disease, resulted in the identification of seven overlapping genes (marked by +in supplementary table S2, available online only) (P. Woo, personal communication).31 It is thus likely that a subset of these 55 genes defines a general innate immune signature. However, the possibility remains that technical artefacts (chip/probe design, processing effects) could influence this overlap.

Anakinra treatment downregulated many genes involved in the regulation of immune responses (CCR1, IL1R2, MMP9, PPM1A, S100P, S100A12, STAT3), apoptosis (BCL2L1, BNIP3L, SNCA), cell adhesion (ITGA, ITGB), haemoglobin synthesis and metabolism. MAP2K3, SLC25A37 and PIM were identified as anakinra-responsive genes in this study, and in a study of eight SoJIA patients.30 We found only 15 transcripts to be upregulated with anakinra and they include several immune receptors (CD1C, TRA, HLA-DPA1, FCER1A) and CDKN1C, a negative regulator of cell proliferation. Larger patient cohorts and meta-analyses of studies involving IL-1β blockers are necessary to validate the anakinra-responsive genes presented here, likewise the gene expression profiles in untreated CAPS patients relative to healthy controls. It may also be of interest to examine gene expression profiles in CAPS patients who require higher doses of anakinra to control their disease.

The transcriptional effect of various IL-1 inhibitors is of great interest to many. In a recent paper by Quartier et al,32 patients affected with another IL-1-mediated disease, systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, developed a de-novo IFN signature after anakinra treatment. In particular transcripts encoding IP-10/CXCL10, TRAIL, OAS1, GBP1, IP10, RSAD2 and SERPING1 were significantly upregulated in systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. None of these transcripts was found on our most stringent list of 140 anakinra-responsive genes, although this result might be influenced by a cell-specific source of RNA (whole blood vs PBMC). On the less stringent list of 263 anakinra-responsive transcripts (see supplementary figure S3, available online only), we found several genes that are known as interferon-regulated genes (IFITM2, IFITM3, IFNGR1, MX1, STAT1, STAT3). An upregulation of type I IFN-regulated transcripts might thus be a common signature in patients undergoing treatment with IL-1 inhibitors.

The CAPS modelling, based on a training set of 83 microarrays, identified 90 transcripts with a combined expression pattern capable of correctly classifying a set of 17 independent samples. Multiple LDA models were created and used collectively to achieve high specificity and sensitivity in a set of independent samples. Only 10/90 CAPS classifier genes are anakinra-responsive genes (see supplementary table S3, available online only), which suggests that these genes may be directly associated with the underlying pathology irrespective of treatment. The pathway analysis of 90 genes from the CAPS-specific gene expression signature supports the role for activated T cells (inducible costimulator and nuclear factor of activated T cells pathways). These data provide evidence that adaptive immunity is activated in this prototypic autoinflammatory disease, possibly as a result of downstream perturbations in cytokine signalling. The CAPS-specific gene expression signature was accurate in identifying correctly 16 post-anakinra samples, thus suggesting that the inflammation was not completely suppressed although all patients were in clinical remission.10 This observation may have important implications for the long-term care of these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Florence Allantaz and Virginia Pascual for providing RNA samples that they could use for paediatric controls. They thank Dr Patricia Woo for providing the list of 305 probe sets that are upregulated in SoJIA patients, and also Drs Elaine Remmers and Igor Dozmorov for helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript.

Funding This study was supported by the intramural research programme of the NIAMS and NHGRI at the NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Ethics approval This study received ethics approval from the NIAMS/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Institutional Review Board.

Patient consent Obtained.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Genetics of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases: past successes, future challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, et al. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle–Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tschopp J, Schroder K. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: the convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nri2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu B, Nakamura T, Inouye K, et al. Novel role of PKR in inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release. Nature. 2012;488:670–674. doi: 10.1038/nature11290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3340–3348. doi: 10.1002/art.10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen R, Verhard E, Lankester A, et al. Enhanced interleukin-1beta and interleukin-18 release in a patient with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3329–3333. doi: 10.1002/art.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattorno M, Tassi S, Carta S, et al. Pattern of interleukin-1beta secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide and ATP before and after interleukin-1 blockade in patients with CIAS1 mutations. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3138–3148. doi: 10.1002/art.22842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, McDermott MF. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in the Muckle–Wells syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2583–2584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306193482523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:581–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldbach-Mansky R. Current status of understanding the pathogenesis and management of patients with NOMID/CINCA. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0165-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1355–1359. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, et al. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1479–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trompouki E, Hatzivassiliou E, Tsichritzis T, et al. CYLD is a deubiquitinating enzyme that negatively regulates NF-kappaB activation by TNFR family members. Nature. 2003;424:793–796. doi: 10.1038/nature01803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurgin V, Novick D, Werman A, et al. Antiviral and immunoregulatory activities of IFN-gamma depend on constitutively expressed IL-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5044–5049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611608104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda F, Nishimura R, Matsubara T, et al. Critical roles of c-Jun signaling in regulation of NFAT family and RANKL-regulated osteoclast differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:475–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vukicevic S, Grgurevic L. BMP-6 and mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz CM, Rinna A, Forman HJ, et al. ATP activates a reactive oxygen species-dependent oxidative stress response and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2871–2879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608083200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, et al. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, et al. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2010;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tassi S, Carta S, Delfino L, et al. Altered redox state of monocytes from cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes causes accelerated IL-1beta secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9789–9794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000779107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauernfeind F, Bartok E, Rieger A, et al. Cutting edge: reactive oxygen species inhibitors block priming, but not activation, of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2011;187:613–617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulua AC, Simon A, Maddipati R, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote production of proinflammatory cytokines and are elevated in TNFR1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) J Experiment Med. 2011;208:519–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanji K, Mori F, Imaizumi T, et al. Upregulation of alpha-synuclein by lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1 in human macrophages. Pathol Int. 2002;52:572–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appel SH. CD4+ T cells mediate cytotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:13–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI38096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonizzi G, Piette J, Merville MP, et al. Cell type-specific role for reactive oxygen species in nuclear factor-kappaB activation by interleukin-1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183:787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allantaz F, Chaussabel D, Stichweh D, et al. Blood leukocyte microarrays to diagnose systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and follow the response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2131–2144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogilvie EM, Khan A, Hubank M, et al. Specific gene expression profiles in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1954–1965. doi: 10.1002/art.22644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:747–754. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.