ABSTRACT

The extraordinary diversity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope (Env) glycoprotein poses a major challenge for the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. One strategy to circumvent this problem utilizes bioinformatically optimized mosaic antigens. However, mosaic Env proteins expressed as trimers have not been previously evaluated for their stability, antigenicity, and immunogenicity. Here, we report the production and characterization of a stable HIV-1 mosaic M gp140 Env trimer. The mosaic M trimer bound CD4 as well as multiple broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, and biophysical characterization suggested substantial stability. The mosaic M trimer elicited higher neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers against clade B viruses than a previously described clade C (C97ZA.012) gp140 trimer in guinea pigs, whereas the clade C trimer elicited higher nAb titers than the mosaic M trimer against clade A and C viruses. A mixture of the clade C and mosaic M trimers elicited nAb responses that were comparable to the better component of the mixture for each virus tested. These data suggest that combinations of relatively small numbers of immunologically complementary Env trimers may improve nAb responses.

IMPORTANCE The development of an HIV-1 vaccine remains a formidable challenge due to multiple circulating strains of HIV-1 worldwide. This study describes a candidate HIV-1 Env protein vaccine whose sequence has been designed by computational methods to address HIV-1 diversity. The characteristics and immunogenicity of this Env protein, both alone and mixed together with a clade C Env protein vaccine, are described.

INTRODUCTION

The generation of HIV-1 Env glycoprotein immunogens that can elicit binding and neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against diverse, circulating HIV-1 strains is a major goal of HIV-1 vaccine development (1–5). The surface Env glycoprotein, which is the primary target of neutralizing antibodies, comprises the gp120 receptor-binding subunit and the gp41 fusion subunit, and it is present as the trimeric spike (gp120/gp41)3 on the virion surface. During the course of natural HIV-1 infection, nearly all individuals induce anti-Env antibody responses but generally with poor neutralization breadth (6–8). It has been reported that approximately 10 to 25% of HIV-1-infected individuals have the ability to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) (9). However, a recent evaluation of a large global panel of sera from infected individuals showed that many individuals make nAb responses against a significant fraction of viruses (10).

One strategy to address HIV-1 sequence diversity involves the construction of bioinformatically optimized “mosaic” antigens (11), which are in silico recombined HIV-1 sequences designed for improved coverage of global HIV-1 diversity. Several proof-of-concept immunogenicity studies in nonhuman primates have demonstrated that vector-encoded mosaic antigens can augment the depth and breadth of cellular immune responses and also improve antibody responses compared to results with consensus and/or natural sequence antigens (12–15). We have also recently reported the protective efficacy of vector-based HIV-1 mosaic antigens against acquisition of SHIV-SF162P3 challenges in rhesus monkeys (16). However, the generation of HIV-1 mosaic Env trimers as protein immunogens has not previously been described.

In this study, we report the production and characterization of a mosaic M (MosM) gp140 trimer. The mosaic M gp140 trimer bound CD4 as well as multiple bnAbs, including VRC01, 3BNC117, PGT121, PGT126, PGT145, PG9, and PG16, and biophysical studies suggested substantial stability. The mosaic M gp160 also exhibited functional capacity to infect target cells. Immunogenicity studies in guinea pigs showed that the mosaic M gp140 elicited high binding antibody titers, cross-clade tier 1 TZM.bl nAbs, and detectable tier 2 A3R5 nAbs that were a different spectrum than spectra elicited by our clade C gp140 trimer. The nAb response elicited by a mixture of the mosaic M gp140 and our clade C gp140 proved superior to either trimer alone, and the combination induced nAb responses comparable to the better single immunogen in the mixture for each virus tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and expression of mosaic HIV-1 Env proteins.

The mosaic M Env gene sequences have been described previously (12, 15, 16). The mosaic gp140s were engineered to contain point mutations to eliminate cleavage and fusion activity (11, 12). To maximize expression in human cell lines, human codon-optimized mosaic M gp140s were synthesized by GeneArt (Life Technologies) with a C-terminal T4 bacteriophage fibritin foldon trimerization domain. A polyhistidine motif was included to facilitate protein purification in one version of the protein. Genes were cloned into the SalI-BamHI restriction sites of a pCMV eukaryotic expression vector, inserts were verified by diagnostic restriction digests, DNA was sequenced, and expression testing was performed using 10 μg of DNA with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) in 293T cells. Stable cell lines for natural C clade isolate C97ZA.012 (NatC) (17) and MosM gp140 Env trimers were generated by Codex Biosolutions.

For protein production, the stable cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], penicillin-streptomycin and puromycin) to confluence and then were changed to Freestyle 293 expression medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with the same antibiotics. Cell supernatants were harvested at 96 to 108 h after medium change, and His-tagged gp140 proteins were purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Qiagen) and size exclusion chromatography as previously described (17, 18). The synthetic gene for full-length MosM gp120 was generated from the MosM gp140 construct. The synthetic gene for full-length MosM gp160 used in the TZM.bl assay was synthesized by GeneArt (Life Technologies) and cloned into a pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen).

The MosM gp140 without a polyhistidine tag was inserted into the pcDNA2004(Neo) vector (GeneArt), which is optimized for expression in PER.C6 cells. Stable MosM gp140-expressing PER.C6 suspension cells were used to produce MosM gp140 trimer without a polyhistidine tag either in batch or fed-batch mode. The MosM gp140 was Galanthus nivalis lectin (Vector Laboratories)-purified from the supernatant followed by gel filtration chromatography.

Biophysical characterization of MosM gp140.

The biophysical properties of MosM gp140 without a polyhistidine tag produced in PER.C6 cells were determined by size exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS), SEC–quasi-elastic light scattering (SEC-QELS), dynamic light scattering (DLS), far-UV circular dichroism (CD), SDS-PAGE, and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) as detailed below.

SEC-MALS/SEC-QELS.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using an analytical column (TSKgel G3000SWxl; Tosoh Bioscience) equilibrated with 150 mM sodium phosphate and 50 mM sodium chloride at pH 7.0. Typically, 125 μg of protein was injected and separated at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. For molar mass determination, in-line UV (Agilent 1260 Infinity MWD; Agilent Technologies), refractive index (Optilab T-rEX; Wyatt Technology), and eight-angle static light-scattering (Dawn HELEOS; Wyatt Technology) detectors were used. Replacement of one of the static light-scattering detectors by a dynamic light-scattering detector (DynaPro NanoStar; Wyatt Technology) enabled determination of hydrodynamic radii simultaneously. The stability of the MosM gp140 protein was studied by SEC-multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) upon incubation for 30 min at 50, 60, 70, 80, or 90°C. Astra Software, including the protein conjugate analysis function, was used for data analysis.

For determination of hydrodynamic radii in batch mode, a dynamic light-scattering detector was used (DynaPro Plate Reader; Wyatt Technology). Light-scattering intensity was detected at 25°C at a concentration of 1 mg/ml during 20 acquisitions of 5 s each. Hydrodynamic radii were determined using the regularization function in the Dynamics software.

Far-UV CD.

Secondary structure analysis was performed using a circular dichroism (CD) spectrometer (model 420; AVIV Biomedical, Inc.) equipped with a recirculating chiller (Thermocube 200/300/400; Solid State Cooling Systems). Far-UV CD spectra were recorded with rectangular 1-mm-path-length quartz cuvettes at concentrations of 3 to 4 μM, using a 0.5-nm (determination of intrinsic properties) or 1-nm (stability study) step width and an averaging time of 4 s. Far-UV CD was recorded after incubation at 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90°C for 10 min. After correction of the signal for baseline drift and contribution of buffer components, the molar residual ellipticity (MRE; in degrees cm2 dmol−1) was calculated based on the following equation: (0.1 × θλ)/[d × M × (number of amino acids], where θλ is the observed ellipticity in millidegrees, d is the path length of the cuvette in cm, and M is the molar concentration.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis SDS-PAGE.

Samples were prepared under nonreducing conditions by addition of LDS sample buffer (NP0007; Life Technologies) and incubation for 10 min at 70°C or 30 min at 98°C. For reducing conditions, LDS sample buffer and a dithiothreitol (DTT)-based reducing reagent (NP0004; Life Technologies) were added, and samples were incubated for 10 min at 98°C. Samples (10 μg/lane) and HiMark Prestained Protein Standard (LC5699, Life Technologies) were applied on the gel (EA03752BOX; Life Technologies). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC).

Measurements were performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (MicroCal VP-Capillary DSC System; GE Healthcare). Samples were buffer exchanged to phosphate-buffered saline and diluted to 3 to 4 μM. Scans were recorded from 25°C to 110°C at a scan rate of 60°C/h. Data were processed using MicroCal VP-Capillary DSC Control Software, version 2.0.

Recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 vector.

Replication-incompetent, E1/E3-deleted recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 (rAd26) vector expressing MosM gp140 was prepared as previously described (12).

Western blot immunodetection.

Supernatants (20 μl) obtained 48 h after transient transfection of 293T cells with pCMV-MosM.3.1 (MosM), -MosM.3.2, or -MosM.3.3 gp140 expression constructs were separately mixed with reducing sample buffer (Pierce), heated for 5 min at 100°C, and run on a precast 4 to 15% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad). Protein was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using an iBlot dry blotting system (Invitrogen), and membrane blocking was performed overnight at 4°C in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline–0.2% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma)–5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk powder (PBS-T). Following overnight blocking, the PVDF membrane was incubated for 1 h with PBS-T containing a 1:2,000 dilution of monoclonal antibody penta-His-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Qiagen), washed five times with PBS-T, and developed using an Amersham ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare). For Western blot immunodetection using 2F5 and 4E10 monoclonal antibodies, clade A (92UG037.8) gp140 (17, 18) and MosM gp140 proteins were processed as described above and detected with an anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

SPR.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding assays were conducted on a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare) at 25°C utilizing HBS-EP (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% P20 surfactant) running buffer (GE Healthcare). Immobilization of soluble two-domain CD4 (19) (1,500 resonance units [RU]) or protein A (ThermoScientific) to CM5 chips was performed according to the manufacturer's (GE Healthcare) recommendations. Immobilized IgGs were captured at 300 to 750 RU. Binding experiments were conducted at a flow rate of 50 μl/min with a 2-min association phase and 5-min dissociation phase. Regeneration was conducted with a single injection of 35 mM NaOH and 1.3 M NaCl at 100 μl/min, followed by a 3-min equilibration phase in HBS-EP buffer. Injections over blank surfaces were subtracted from the binding data for analyses. Binding kinetics were determined using BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare) and the Langmuir 1:1 binding model with the exception of PG16, which was determined using a bivalent analyte model. All samples were run in duplicate and yielded similar kinetic results. Soluble two-domain CD4 and PG9 and PG16 Fabs were produced as described previously (17, 19). 17b hybridoma was provided by James Robinson (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA) and purified as previously described (17). VRC01 was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. VRC01 was provided by John Mascola (VRC, NIH, Bethesda, MD) (20). 3BNC117 was provided by Michel Nussenzweig (Rockefeller University, New York, NY). PGT121, PGT126, and PGT145 were provided by Dennis Burton (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). 2F5, 4E10, PG9, and PG16 were obtained commercially (Polymun Scientific). GCN gp41-inter (21) was used as a positive control in 4E10 and 2F5 SPR analyses.

Animals and immunizations.

Outbred female Hartley guinea pigs (Elm Hill) (n = 10/group) were housed at the Animal Research Facility of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center under approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocols. Guinea pigs were immunized intramuscularly (i.m.) with either MosM or NatC gp140 Env trimer or both (100 μg/animal) at weeks 0, 4, and 8 in 500-μl injection volumes divided between the right and left quadriceps. The adjuvant was either 15% (vol/vol) oil-in-water Emulsigen (MVP Laboratories)-PBS and 50 μg of immunostimulatory dinucleotide type B oCpG DNA (5′-TCGTCGTTGTCGTTTTGTCGTT-3′) (Midland Reagent Company) (17) or the immune-stimulating complex (ISCOM)-based Matrix M (Novavax). The groups of animals receiving the mixture of NatC and MosM (NatC+MosM) gp140s were given a dose of 50 μg of each trimer, for a total of 100 μg per animal. In heterologous prime-boost regimens, a rAd26 vector expressing MosM gp140 (1 × 1010 virus particles [vp]/animal) was administered i.m. at week 0 in 500 μl of PBS-sucrose, and animals were boosted at weeks 8, 12, and 16 with either MosM, NatC, or bivalent NatC+MosM gp140 Env protein trimers (100 μg/animal) in Adju-Phos alum (Brenntag, Denmark) adjuvant. Serum samples were obtained from the vena cava of anesthetized animals at 4 weeks after each immunization.

ELISAs.

Serum binding antibody titers against MosM or NatC gp140 Env trimer were determined by endpoint enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) as previously described (17, 18). Endpoint titers were defined as the highest reciprocal serum dilution that yielded an absorbance of >2-fold over background values. For the detection of membrane-proximal external region (MPER) epitopes in the MosM trimer, ELISA plates were coated with either 2F5 or 4E10 IgG, antigen was added, and epitopes were detected utilizing anti-His tag-HRP monoclonal antibody (MAb; Abcam). 2F5 and 4E10 were obtained commercially (Polymun Scientific), and GCN gp41-inter (21) was used as a positive control in 4E10 and 2F5 ELISAs.

TZM.bl neutralization assay.

Neutralizing antibody responses against tier 1 HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses were measured using luciferase-based virus neutralization assays with TZM.bl cells as previously described (17, 18, 22). These assays measure the reduction in luciferase reporter gene expression levels in TZM.bl cells following a single round of virus infection. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated as the serum dilution that resulted in a 50% reduction in relative luminescence units compared with the virus control wells after the subtraction of cell control relative luminescence units. The panel of 11 tier 1 viruses analyzed included easy-to-neutralize tier 1A viruses (SF162.LS and MW965.26) and an extended panel of tier 1B viruses (DJ263.8, Bal.26, TV1.21, MS208, Q23.17, SS1196.1, 6535.3, ZM109.F, and ZM197M) (22) (23). Murine leukemia virus (MuLV) negative controls were included in all assays.

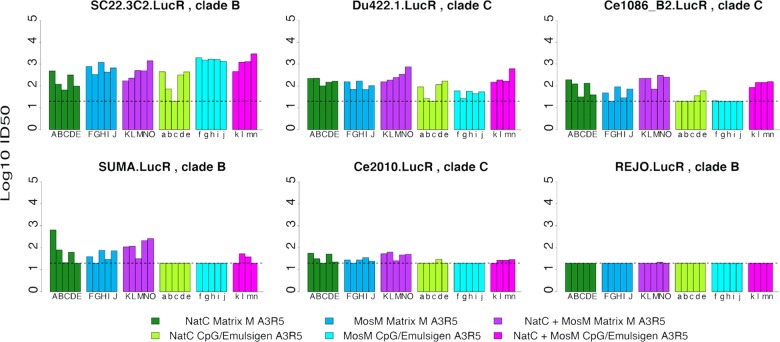

A3R5 neutralization assay.

Additional nAb responses were evaluated using an A3R5 assay as previously described (17). Briefly, serial dilutions of serum samples were performed in 10% RPMI growth medium (100 μl per well) in 96-well flat-bottomed plates. Infectious molecular clone (IMC) HIV-1 expressing Renilla luciferase (24) was added to each well in a volume of 50 μl, and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. A3R5 cells were then added (9 × 104 cells per well in a volume of 100 μl) in 10% RPMI growth medium containing DEAE-dextran (11 μg/ml). Assay controls included replicate wells of A3R5 cells alone (cell control) and A3R5 cells with virus (virus control). After samples were incubated for 4 days at 37°C, 90 μl of medium was removed from each assay well, and 75 μl of cell suspension was transferred to a 96-well white, solid plate. Diluted ViviRen Renilla luciferase substrate (Promega) was added to each well (30 μl), and after 4 min the plates were read on a Victor 3 luminometer. The A3R5 cell line was provided by R. McLinden and J. Kim (U.S. Military HIV Research Program, Rockville, MD). Tier 2 clade B IMC Renilla luciferase-expressing viruses included SC22.3C2.LucR, SUMA.LucR, and REJO.LucR. Tier 2 clade C IMC Renilla luciferase-expressing viruses included Du422.1.LucR.T2A.ecto, Ce2010_F5.LucR.T2A.ecto, and Ce1086_B2.LucR.T2A.ecto and were provided by C. Ochsenbauer (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL). Viral stocks were prepared in 293T/17 cells as previously described (24).

Statistical analyses.

For both the TZM.bl and A3R5 data described above, the neutralization scores used for plotting and for statistical considerations are provided as the IC50 titer of the postvaccination serum with the prevaccination background subtracted as previously described (25). All reactivity that was below the level of assay detection (<20) was assigned the value 20 for plotting and statistical purposes. Titers within a 3-fold range are considered “concordant”; thus, we considered titer differences of the geometric mean group response that were >0.5 log as indicative of robust differences. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package R (http://www.r-project.org/). Nonparametric Wilcoxon tests were used to compare distributions of values between vaccine groups, Fisher's exact test was used to compare the relative proportions of responses that were above the level of detection in different vaccine groups, and the R package lme4 (26) was used to model the relative impact of different variables on neutralization sensitivity levels.

RESULTS

Expression and stability of the mosaic M gp140 trimer.

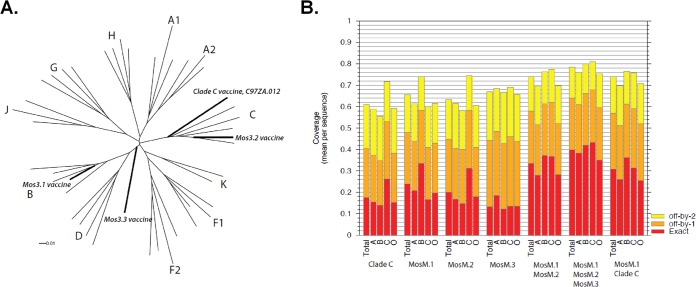

We have previously described the mosaic M Env gene sequences (12, 16). MosM.3.1 Env (whose nomenclature has been simplified here to MosM Env) is more closely related to clade B natural strains, whereas MosM.3.2 Env is most closely related to clade C natural strains, and MosM.3.3 is not particularly associated with any clade but captured complementary forms of epitopes that are common throughout the M group and not already represented in MosM and MosM3.2 (Fig. 1). The mosaic forms, in combination, optimize potential coverage of linear epitopes in the population, but MosM combined with the natural isolate C97ZA.012 (17, 18, 27) (whose nomenclature has been simplified here to NatC) enhanced potential linear epitope coverage to levels approached using two mosaic trimers (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Phylogeny and theoretical coverage of mosaic Env immunogens. (A) Phylogenetic tree illustrating sequence associations of gp140 vaccine candidate sequences and representative sequences from different clades. The subtype reference alignment (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/NEWALIGN/align.html) from the Los Alamos HIV database is used here to provide context to illustrate the subtype associations of the different mosaic sequences. Representative sequences of major clades are shown, with the clade indicated by the letter, and vaccine candidates studied here are indicated in bold italics. The mosaics were intended to be used in combination, and when combined they maximize M group epitope coverage but slightly favor B and C subtypes as these clades are most heavily sampled. This tree was generated using PhyML (47) (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/PHYML/interface.html), using an HIVb model and parameters estimated from the data. (B) Potential epitope coverage of different potential vaccines and vaccine combinations. We tested the potential epitope coverage (linear 9-mers), restricted to only one Env per person, or a total of 4,186 sequences: 1,501 clade B, 1,031 clade C, 226 clade A, and 1,428 other subtypes and recombinants, grouped together (category O). Because HIV database sampling is biased toward B and C clades, the coverage is naturally slightly better for these subtypes than for other subtypes; still, using combinations of mosaics gives relatively good potential epitope coverage of all subtypes (11; http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/MOSAIC/epicover.html). Vaccine combinations are labeled across the bottom. The average fractions of 9-mers per natural strain perfectly matched by the vaccines are indicated by the red bars; the fractions with an 8/9 match or better are indicated by orange, and a 7/9 match or better is indicated by yellow. The only mosaic protein that was stable and well expressed as a trimer, MosM (MosM.1) fortuitously turns out to be an excellent complement to the natural C clade protein (NatC; here, Clade C), C97ZA.012, that we had previously targeted for vaccine design because of it expression, stability, and antigenic and immunogenic attributes when expressed as a trimer (compare the MosM.1+MosM.2 [MosM.3.2] to MosM.1+Clade C). The coverage of 9-mers for MosM and NatC, the series of coverage graphs on the far right, approaches the coverage of 9-mers for MosM and MosM.3.2, which were optimized for 9-mer coverage.

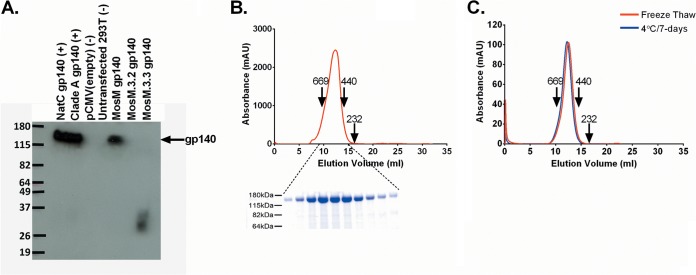

Eukaryotic pCMV DNA vectors expressing HIV-1 MosM, MosM.3.2, and MosM.3.3 gp140 were transfected into 293T cells, and protein expression and stability were assessed after 48 h. Western blot analysis revealed a band of the expected size only for MosM gp140 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that MosM gp140 was more stable than MosM.3.2 gp140 and MosM.3.3 gp140. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using material generated from a stable 293T cell line expressing the MosM gp140 demonstrated a monodispersed peak, confirming the homogeneity of the trimer (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the preliminary stability of the MosM trimer, 100 μg of protein underwent a freeze-thaw cycle or was stored for 7 days at 4°C and reevaluated by SEC and showed no signs of aggregation, dissociation, or degradation (Fig. 2C). Given the reduced stability of MosM.3.2 and the good theoretical coverage of MosM combined with NatC, we focused on the combination of MosM and NatC for the rest of this study.

FIG 2.

Expression and stability of the MosM trimer. (A) Western blot showing expression of HIV-1 MosM, MosM.3.2, and MosM.3.3 gp140s at 48 h after transient transfection of 293T cells. NatC gp140 and clade A (92UG037.8) gp140 were used as positive controls. (B) Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profile of the purified mosaic MosM trimer with SDS-PAGE of peak fractions. AU, arbitrary units. (C) SEC profile of the MosM trimer after freeze-thaw and incubation at 4°C for 7 days.

Biophysical characterization of the MosM gp140 trimer.

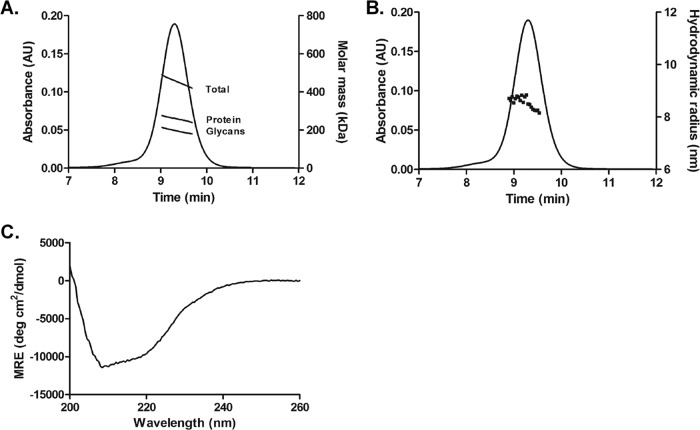

The mass and size of MosM gp140 produced in stable PER.C6 cell clones were assessed under native conditions by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) coupled with online multiangle light-scattering (MALS) and dynamic light-scattering (DLS) detectors. The molar mass of the glycoprotein was determined by SEC-MALS to be 454 ± 36 kDa, which indicated that the MosM gp140 was trimeric (Fig. 3A). By applying protein conjugate analysis, the estimated molecular mass of the protein component was 258 ± 20 kDa, which corresponds within experimental error to the theoretical molecular mass of an unglycosylated protein trimer. The amount of glycosylation was estimated to be 198 ± 18 kDa, which showed that the level of glycosylation in MosM trimer is significantly higher than previously reported for the BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer (28). The tight packing of the MosM gp140 was further confirmed by both batch and online DLS measurements, which showed that the estimated hydrodynamic radius of the protein was 8.2 to 8.8 nm, similar to the reported 8.1-nm hydrodynamic radius of the BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer (28), accounting for the increased glycosylation (Fig. 3B). The secondary structure of the MosM trimer was assessed by far-UV circular dichroism (CD) (Fig. 3C) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (data not shown). As expected, both far-UV CD and FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the presence of alpha-helical and beta-sheet secondary structure elements. The mean residue molar ellipticity was assessed from the far-UV CD spectrum as approximately −11,000 degrees cm2 dmol−1.

FIG 3.

Biophysical characterization of MosM trimer. (A) SEC-MALS profile of the MosM trimer. The total mass of the molecule and the mass contributions of the protein and glycan components are shown for the 9.0- to 9.7-min elution interval as determined from protein conjugate analysis (B) SEC-QELS analysis. The SEC profile of the MosM trimer is shown together with the hydrodynamic radii derived from the autocorrelation functions. (C) Far-UV CD analysis. The mean residue molar ellipticity (MRE) is shown as a function of wavelength between 200 and 260 nm.

The thermal stability of the MosM trimer was assessed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), far-UV CD, and SEC-MALS. No unfolding transitions were detected by DSC upon applying a temperature ramp up to 110°C (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, no significant changes in secondary structure were detected upon exposure of the protein to temperatures up to 90°C, as shown by the unaltered far-UV CD spectra (Fig. 4B). The robustness of the protein was also confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy (data not shown). The SEC-MALS experimental data indicated that the trimer molecule underwent a partial dimerization to a hexamer at temperatures above 70°C, but no further aggregation or dissociation (Fig. 4C). In particular, based on the quantitative recoveries from the SEC column, no higher-molecular-weight entities were formed at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the hydrodynamic radius of the trimer did not change upon its exposure to elevated temperatures, thus confirming its remarkable stability.

FIG 4.

Thermal stability of the MosM trimer. (A) DSC thermal scanning of the MosM trimer. Heat capacity (Cp) was followed as a function of temperature up to 110°C showing no dissociation (black line). For comparison, the DSC profile of a typical monoclonal antibody is shown (blue line). (B) Far-UV CD spectra of the MosM trimer recorded at 25°C and after 10 min of subsequent heating at 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90°C. (C) SEC-MALS profiles of the MosM trimer in the absence of heat stress and upon incubation for 30 min at 50, 60, 70, 80, or 90°C. Quantitative recoveries from the SEC column demonstrate that no high-molecular-weight species were formed during incubation. (D) SDS-PAGE of the MosM trimer under nonreducing conditions after heat treatment for 10 min at 70°C (lane 1) or 30 min at 98°C (lane 2) and under reducing conditions after heat treatment for 10 min at 98°C (lane 3). The molecular mass ladder used as a standard for molecular mass determination is shown in lane 4.

The high stability of the MosM trimer was also shown by the difficulty unfolding the protein even in SDS-PAGE loading buffer at elevated temperatures. The MosM trimer could still be observed on a nonreduced gel after the protein was incubated with SDS-containing buffer at 70°C (Fig. 4D). The trimer band disappeared while some amounts of dimer were still detected when the sample was incubated for 30 min at 98°C in SDS loading buffer on a nonreduced gel, indicating that the trimer units were not held together via disulfide bridges (Fig. 4D).

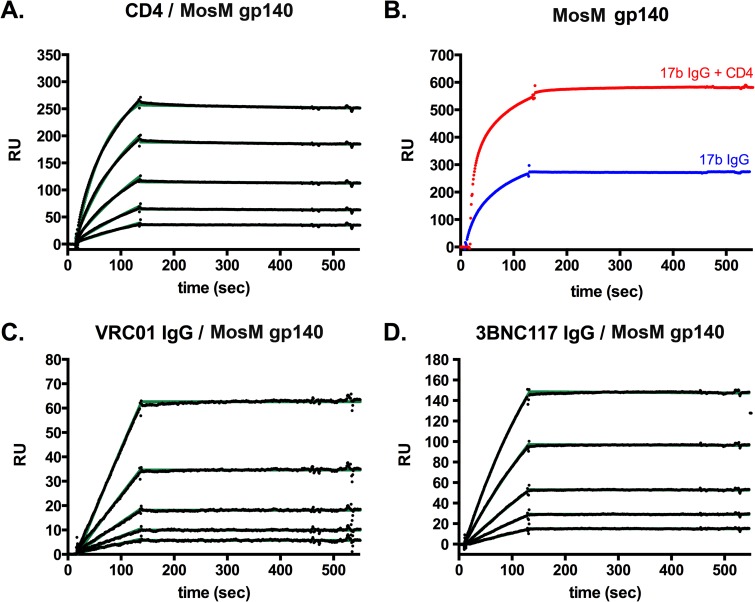

Antigenicity of the mosaic M gp140 trimer.

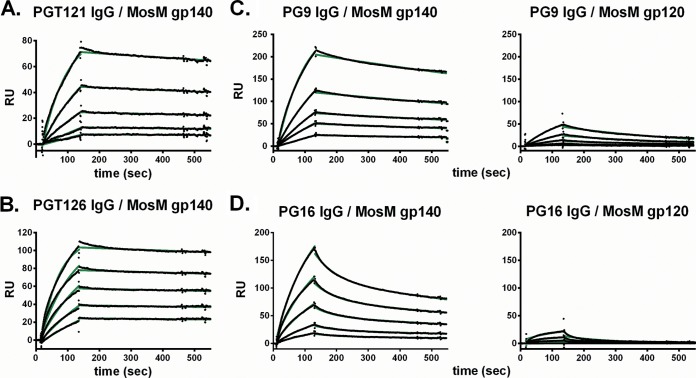

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies were next performed to determine whether the MosM trimer could bind CD4 and broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. The MosM trimer bound CD4 at a high affinity, demonstrating that the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) is present and accessible (Fig. 5A). We next evaluated the ability of the MosM trimer to bind the monoclonal antibody (MAb) 17b in the presence and absence of bound CD4. 17b recognizes a CD4-induced (CD4i) epitope exposed by CD4 binding and the formation of the bridging sheet and coreceptor binding site in gp120 (29, 30). The MosM trimer showed 17b binding in the absence of CD4, but there was a clear increase following CD4 binding, as expected (Fig. 5B). We next observed that the broadly neutralizing CD4bs-specific MAbs VRC01 and 3BNC117 (20, 31) bound the MosM gp140 with high affinity (Fig. 5C and D). Moreover, the broadly neutralizing N332 glycan-dependent MAbs PGT121 and PGT126 also bound the trimer with high affinity (Fig. 6A and B). PG9 and PG16 have been reported to bind preferentially to Env trimers and target V2 glycans (32, 33). PG9 bound the MosM gp140 trimer with high affinity (5.8 × 10−8 M) and the corresponding MosM gp120 monomer with a 22-fold lower affinity (1.3 × 10−6 M) and substantially lower magnitude (Fig. 6C). The PG9 Fab bound to the MosM gp140 trimer with a similar affinity (5.5 × 10−8 M) as the complete PG9 IgG (data not shown), confirming the high-affinity PG9 binding. Similarly, PG16 bound the MosM gp140 trimer with a higher affinity than the corresponding gp120 monomer (Fig. 6D) although the off-rate was higher for PG16 than PG9.

FIG 5.

SPR binding profiles of the MosM trimer to CD4, 17b, VRC01, and 3BNC117. For all bnAb binding experiments, protein A was irreversibly coupled to a CM5 chip, and IgGs were captured. (A) Soluble, two-domain CD4 was irreversibly coupled to a CM5 chip, and MosM gp140 was flowed over the chip at concentrations of 62.5 to 1,000 nM. (B) 17b IgG was captured, and MosM gp140 was flowed over bound IgG at a concentration of 1,000 nM in the presence (red trace) or absence (blue trace) of CD4 bound to the immunogen. (C and D) VRC01 IgG or 3BNC117 IgG was captured, and MosM gp140 was flowed over the bound IgGs at concentrations of 62.5 to 1,000 nM. All sensograms are presented in black; kinetic fits are in green. RU, resonance units.

FIG 6.

SPR binding profiles of the MosM trimer to glycan-dependent bnAbs PGT121 and PGT126 and trimer-dependent bnAbs PG9 and PG16. For all experiments, protein A was irreversibly coupled to a CM5 chip, and IgGs were captured. MosM gp140 was flowed over bound PGT121 IgG (A) and PGT126 IgG (B) at concentrations of 62.5 to 1,000 nM. MosM gp140 or gp120 was flowed over bound PG9 IgG (C) and PG16 IgG (D). Sensograms are presented in black, and kinetic fits are in green. RU, resonance units.

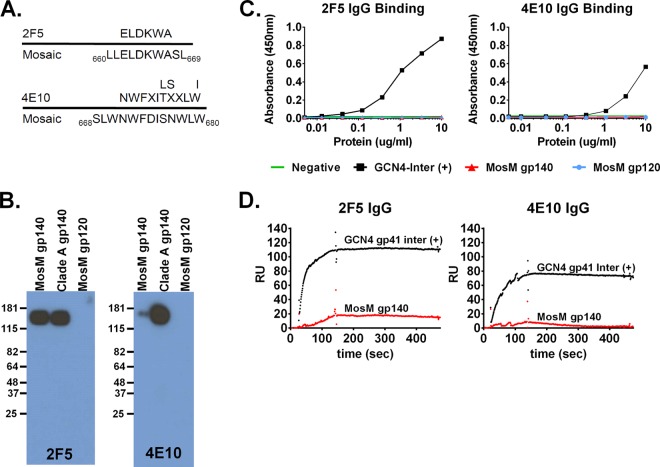

We also assessed 2F5 and 4E10 binding to membrane-proximal external region (MPER) epitopes. 2F5 and 4E10 bind to linear epitopes (34, 35). The 2F5 epitope was present in the linear MosM gp140 sequence, as confirmed by sequence alignment (Fig. 7A) and Western blot (Fig. 7B) analyses. However, by SPR and ELISA, the intact MosM gp140 trimer was unable to bind 2F5, suggesting that the MPER epitope is not accessible in the trimer structure, presumably as a result of being buried (35) (Fig. 7C and D), similar to our previous findings with the NatC trimer (17). Alternatively, it is possible that the absence of a lipid membrane (36, 37) in the MosM gp140 trimer may have reduced 2F5 binding.

FIG 7.

Lack of presentation of membrane-proximal external region epitopes by the MosM trimer. (A) Sequence alignment of the 2F5 and 4E10 epitope sequences to MosM gp140 trimer sequence. (B) Western blot of 2F5 and 4E10 bound to MosM gp140, 92UG037.8 gp140 (positive control), and MosM gp120 (negative control). (C) 2F5 and 4E10 binding ELISA of MosM gp140. GCN4-inter, clade A (92UG037.8) gp41-inter (positive control). The dotted line indicates assay background threshold. (D) SPR binding of protein A-captured 2F5 and 4E10 to MosM gp140.

Taken together, the biochemical, biophysical, and antigenicity data suggest the robustness of the MosM gp140 trimer. This is based on the expected molecular mass and hydrodynamic radius, its remarkable stability, and its capacity to bind all CD4 binding site-, V3 glycan-, and V2 glycan-specific broadly neutralizing MAbs that we have tested, except for 2F5 and 4E10 as expected.

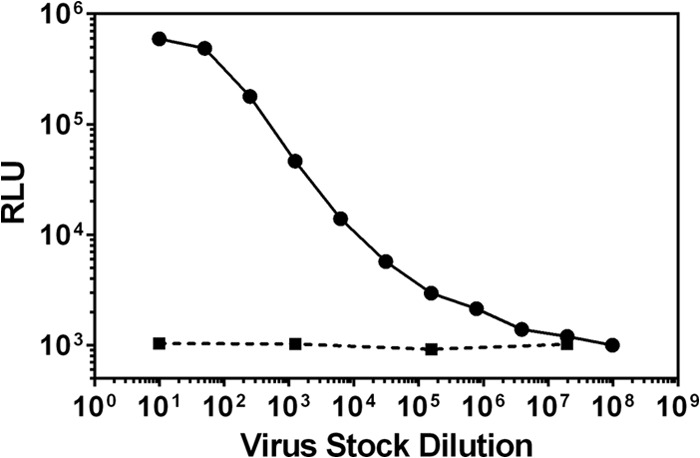

Functionality of mosaic M gp140 trimer.

We next evaluated whether the MosM Env protein was functional. Full-length MosM gp160 was used to generate pseudovirions to assess infectivity in TZM.bl cells (17, 18, 22, 40). We observed that, over a broad titration range, MosM gp160 Env readily infected TZM.bl target cells overexpressing CD4 and coreceptors CCR5/CXCR4 (Fig. 8). These data show that the synthetic MosM Env has the functional ability to infect TZM.bl target cells.

FIG 8.

MosM gp160 Env pseudovirion infection of TZM.bl cells. Pseudovirions generated with full-length MosM gp160 Env were used to infect target TZM.bl cells expressing CD4 and coreceptors CCR5/CXCR4 in the TZM.bl assay. The dashed line indicates background of TZM.bl cells alone without virus (negative control). RLU, relative luminescence units.

Immunogenicity of the mosaic M gp140 trimer.

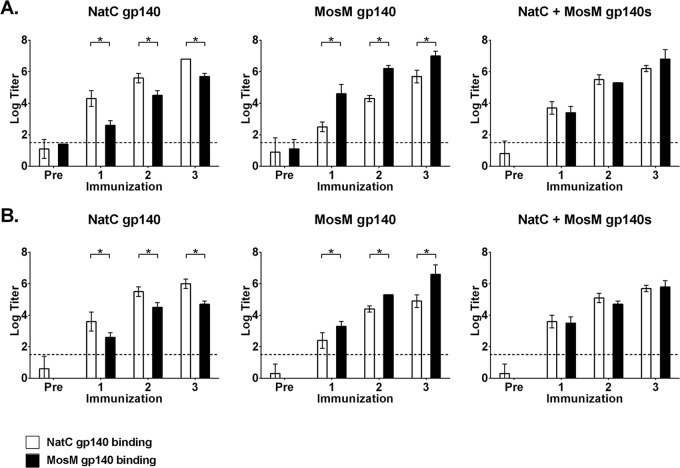

Guinea pigs (n = 10/group) were immunized three times at monthly intervals with 100 μg of MosM gp140 trimer, 100 μg of NatC gp140 trimer (17, 18), or a mixture of 50 μg of both trimers. Half of the animals were immunized with ISCOM-based Matrix M adjuvant, and half were immunized with CpG/Emulsigen adjuvants (17, 41). High-titer, binding antibodies by ELISA were elicited by all the vaccination regimens with comparable kinetics (Fig. 9). These responses were detectable after a single immunization and increased after the second and third immunizations. Peak binding antibody titers ranged from 5 to 7 logs. Binding antibody titers elicited by the NatC and MosM trimers were higher against their respective homologous antigens (P < 0.05), whereas the bivalent MosM and NatC mixture induced comparable responses to both antigens (Fig. 9). ELISA titers were similar using trimers with or without the His tag as coating antigens (data not shown).

FIG 9.

ELISA antibody endpoint binding titers in guinea pigs. Serum obtained 4 weeks after each immunization with NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM gp140s in Matrix M (A) or CpG/Emulsigen (B) adjuvant was assessed by ELISA against MosM and NatC gp140 trimer antigens. Data are presented as geometric mean titers at each time point ± standard deviations. The horizontal broken line indicates assay background threshold. *, P < 0.05 (unpaired t test). Pre, preimmunization.

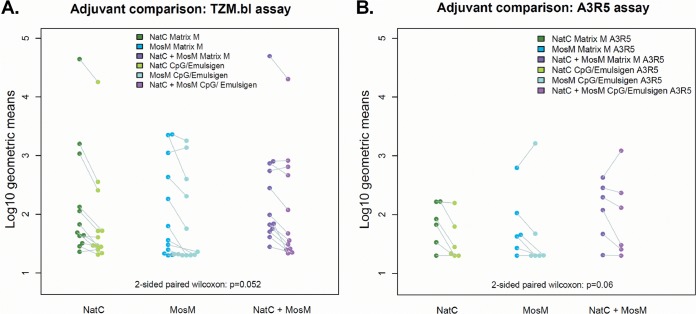

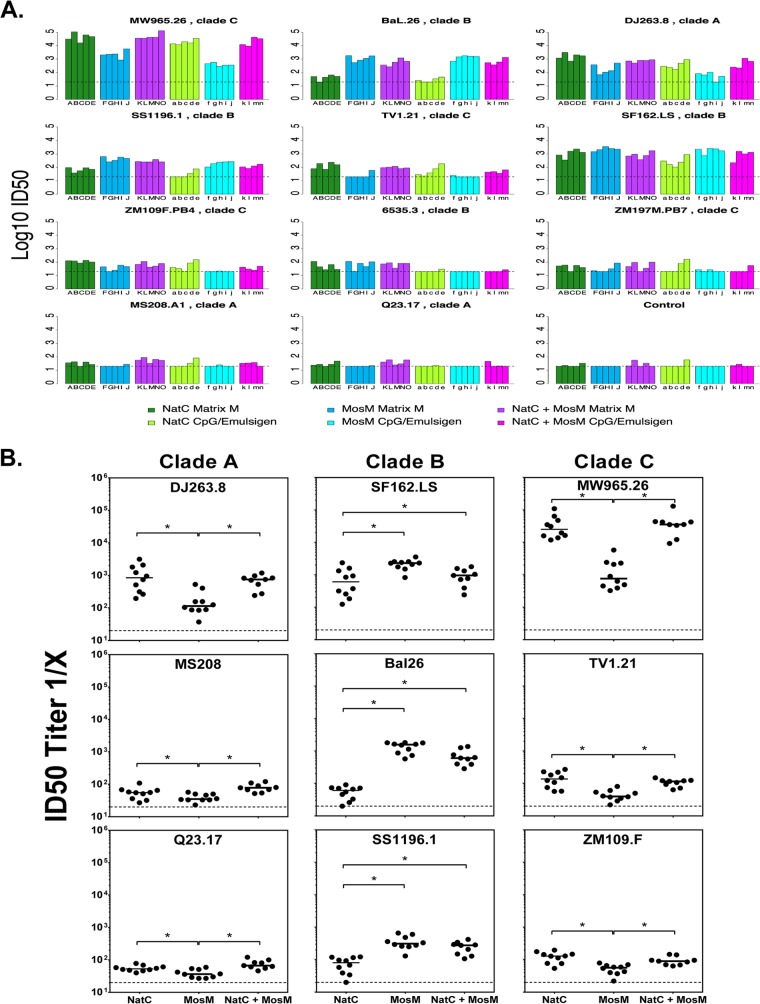

We next assessed serum nAb responses elicited in these animals after the third vaccination using both TZM.bl and A3R5 nAb assays (17, 18, 22, 40). For the TZM.bl assays, we included a multiclade panel of tier 1 pseudoviruses comprising easy-to-neutralize tier 1A viruses (SF162.LS and MW965.26) and an extended panel of intermediate tier 1B viruses (DJ263.8, Bal.26, TV1.21, MS208, Q23.17, SS1196.1, 6535.3, ZM109.F, and ZM197M) (22, 23). Background prevaccination titers were negative or low in all animals (<20) (data not shown). We observed a trend for slightly increased responses with the Matrix M adjuvant compared with CpG/Emulsigen adjuvant (P = 0.05 and 0.06 for the TZM.bl and A3R5 assays, respectively) (Fig. 10).

FIG 10.

Adjuvant comparison. (A) Adjuvant comparison in the TZM.bl assay. (B) Adjuvant comparison in the A3R5 assay. In a two-sided test, there was a marginal significance level, suggesting that Matrix M was slightly more potent than CpG/Emulsigen (P = 0.05 for the TZM.bl assay; P = 0.06 for the A3R5 assays).

The nAb responses elicited by the bivalent NatC+MosM trimer mixture were comparable to the better of the two immunogens in the cocktail for each virus tested (Fig. 11A). Thus, there was no apparent loss of potency due to dilution or competition in the NatC+MosM mixture, and the overall response to the NatC+MosM cocktail was thus superior to either immunogen alone. A statistical breakdown of the data, comparing response level distributions by a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test, is provided in Table 1 and summarized in Fig. 11B. Specifically, using the TZM.bl assay, for 2 (ZM197M and 6535) of the 11 viruses, the responses were indistinguishable between the three vaccine groups although responses to both of these viruses were borderline. For 6 of the 11 viruses, the responses to the individual MosM and NatC monovalent immunogens were significantly different, and the NatC+MosM combined vaccine was comparable to the higher of the two monovalent vaccines in each case. A similar trend was observed for SF162.LS. The NatC+MosM combination yielded a more potent response than both monovalent vaccines for one virus (MS208), whereas the NatC gp140 slightly outperformed the bivalent NatC+MosM vaccine for one virus (ZM109F). Overall, these data suggest that the MosM and NatC gp140 Env trimers were immunologically complementary and could be effectively combined as a mixture that was superior to either trimer alone in terms of nAb coverage. Less clear differences were observed for tier 2 viruses in A3R5 neutralization assays (Fig. 12).

FIG 11.

TZM.bl nAb responses in guinea pigs. Animals immunized with either NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM trimers were assayed against tier 1A viruses (SF162.LS and MW965.26) and an extended panel of tier 1B viruses (DJ263.8, Bal.26, TV1.21, MS208, Q23.17, SS1196.1, 6535.3, ZM109.F, and ZM197M). (A) Darker colors indicate the Matrix M adjuvant, whereas the equivalent lighter colors indicate the CpG/Emulsigen adjuvants. Individual animals are labeled with the letters of the alphabet, with uppercase for animals vaccinated with the Matrix M adjuvant and lowercase for CpG/Emulsigen, and are ordered the same way for each virus tested. The viruses are ordered such that the top row and the first two panels in the second row (MW965.26, BaL.26, DJ263.8, SS1196.1, TV1.21) had the most distinctive behavior in terms of virus sensitivity to neutralizing activity raised by each vaccine (over a half-log difference between the geometric means of the groups). The bottom right shows a representative MuLV negative control. There were only four animals in the CpG/Emulsigen, bivalent NatC+MosM vaccine group as one was lost during bleeding procedures. ID50, 50% infective dose. (B) Summary figure comparing the nAb responses to the MosM, NatC, and bivalent NatC+MosM trimers to nine clade A, B, and C viruses. *, P < 0.05.

TABLE 1.

A summary of the P values from Wilcoxon rank sum tests comparing group responses to different vaccinesa

| Assay and clade | Virus |

P value for: |

Titer difference | Pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MosM vs NatC | MosM vs NatC+MosM | NatC vs NatC+MosM | Single x bivalent | ||||

| TZM.bl | |||||||

| B | SF162 | 0.095 | NA | NA | 0.075 | −0.32 | NatC+MosM ∼ MosM ∼ NatC |

| C | ZM109F | 0.008 | 0.095 | 0.032 | NA | 0.49 | NatC > NatC+MosM ∼ MosM |

| C | MW965 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.69 | NA | 1.3 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ≫ MosM |

| C | TV1 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.69 | NA | 0.73 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ≫ MosM |

| B | BaL | 0.008 | 0.15 | 0.008 | NA | −1.4 | NatC+MosM ∼ MosM ≫ NatC |

| A | DJ263 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.095 | NA | 0.94 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ≫ MosM |

| B | SS1196 | 0.008 | 0.075 | 0.008 | NA | 0.81 | NatC+MosM ∼ MosM ≫ NatC |

| A | MS208 | 0.075 | NA | NA | 0.007 | 0.18 | NatC+MosM > MosM ∼ NatC |

| A | Q23 | 0.044 | 0.010 | 0.14 | NA | 0.14 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC > MosM |

| C | ZM197 M | 0.40 | NA | NA | 0.38 | 0.15 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ∼ MosM |

| B | 6535 | 0.55 | NA | NA | 0.58 | −0.11 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ∼ MosM |

| A3R5 | |||||||

| C | Du422 | 0.22 | NA | NA | 0.013 | 0.2 | NatC+MosM ≫ NatC ∼ MosM |

| B | SC22 | 0.032 | 0.55 | 0.095 | NA | −0.58 | NatC+MosM ∼ MosM ≫ NatC |

| C | Ce1086 | 0.22 | NA | NA | 0.013 | 0.27 | NatC+MosM > NatC ∼ MosM |

| C | Ce2010 | 0.60 | NA | NA | 0.098 | 0.10 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ∼ MosM |

| B | SUMA | 0.75 | NA | NA | 0.075 | 0.20 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ∼ MosM |

In this analysis, we considered a two-sided P value of <0.05 using a Wilcoxon rank test to compare the Matrix M vaccine groups shown in Fig. 9 to 11 to be indicative of a difference between groups. If the P value was <0.05 for a given virus in a comparison of the MosM and NatC gp140 vaccine groups, we considered the monovalent groups to be distinctive and compared each of them to the bivalent NatC+MosM vaccine group. If the P value was >0.05, we considered the response between the groups to be equivalent and compared the combined monovalent groups to the bivalent group (single x bivalent). The outcome is summarized in the Pattern column as follows: ∼, response levels were approximately the same between two groups; >, one or two of the groups had higher responses. If the Wilcoxon test indicated that there was a difference in the distributions and if the geometric means were greater than half a log different, the higher response is indicated (≫). The difference between average values of the log10 neutralization titers of two monovalent vaccine groups is also shown. The six groups that differ by >0.5 log in their mean responses are indicated in bold. NA, not applicable.

FIG 12.

A3R5 nAb responses in guinea pigs. Animals immunized with either NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM trimers were assayed against three tier 2 clade B viruses (SC22.3C2, SUMA, and REJO) and three tier 2 clade C viruses (Du422.1, Ce2010, and Ce1086_B2). Individual animals are labeled with the letters of the alphabet, with uppercase for animals vaccinated with the Matrix M adjuvant and lowercase letters for CpG/Emulsigen adjuvant, and are ordered the same way for each virus tested.

To evaluate the complexity of the interactions between variables that might impact neutralization sensitivity, each assay was analyzed separately using an inverse Gaussian generalized model. Animals and viruses were included in the model as random effects. For fixed effects, we started testing the larger possible model, which included vaccine, clade, adjuvant, and all their possible interactions, and then scaled down the model in a stepwise manner, eliminating one variable at a time until we minimized the Akaike information coefficient (AIC). We initially fit the whole data set with 11 viruses and both adjuvants (Table 2). The best model had a significant interaction between vaccine and clade (P < 2.2e−16). This statistical analysis confirms that the MosM trimer, which is more clade B like (Fig. 1A), elicits stronger responses to the clade B viruses, whereas the NatC trimer elicits stronger responses to clade C as well as clade A viruses. A significant effect from the adjuvant (P = 0.0074) was also observed, indicating the higher potency of the Matrix M adjuvant.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the results of an inverse Gaussian generalized model with virus and animal as random effectsa

| Intercept | Estimated effect | SE | t value | Pr(>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant Matrix M | 2.2 | 0.18 | 11.97 | <2e−16*** |

| Vaccine NatC+MosM | 0.21 | 0.050 | 4.17 | 3.1e−05*** |

| Vaccine MosM | 0.089 | 0.084 | 1.06 | 0.29 |

| Clade B | −0.10 | 0.24 | −0.42 | 0.68 |

| Clade C | 0.98 | 0.24 | 4.07 | 4.80e−05*** |

| Vaccine NatC+MosM:CladeB | 0.31 | 0.10 | 3.06 | 0.0022** |

| Vaccine MosM:CladeB | 0.71 | 0.10 | 7.36 | 1.82e−13*** |

| Vaccine NatC+MosM:CladeC | −0.18 | 0.10 | −1.78 | 0.075 |

| Vaccine MosM:CladeC | −0.21 | 0.09 | −2.42 | 0.015* |

We initially fit the whole data set with 11 viruses and both adjuvants. The best model had a significant interaction between vaccine and clade (P < 2.2e−16) and a significant effect from the adjuvant (P = 0.0074). Matrix M responses were on average 1.6 times higher than CpG/Emulsigen responses. The summary shows the estimated effects (in logarithmic scale). Effects of categorical variables are with respect to the reference category: the row labeled Adjuvant Matrix M, for example, shows the effect of Matrix M compared to the Emulsigen adjuvant. Vaccine NatC+MosM and Vaccine Mosaic M show the estimated effects with respect to the reference category, which in this case is the NatC vaccine. The estimate indicates the relative impact, on a log scale, of a given factor relative to the adjuvant CpG/Emulsigen (Matrix M is log 0.2 higher), the NatC vaccine, and the virus clade A. The colon (:) indicates an interaction between two variables. Asterisks indicate levels of significance (*, modest significance; **, high significance; ***, extreme significance).

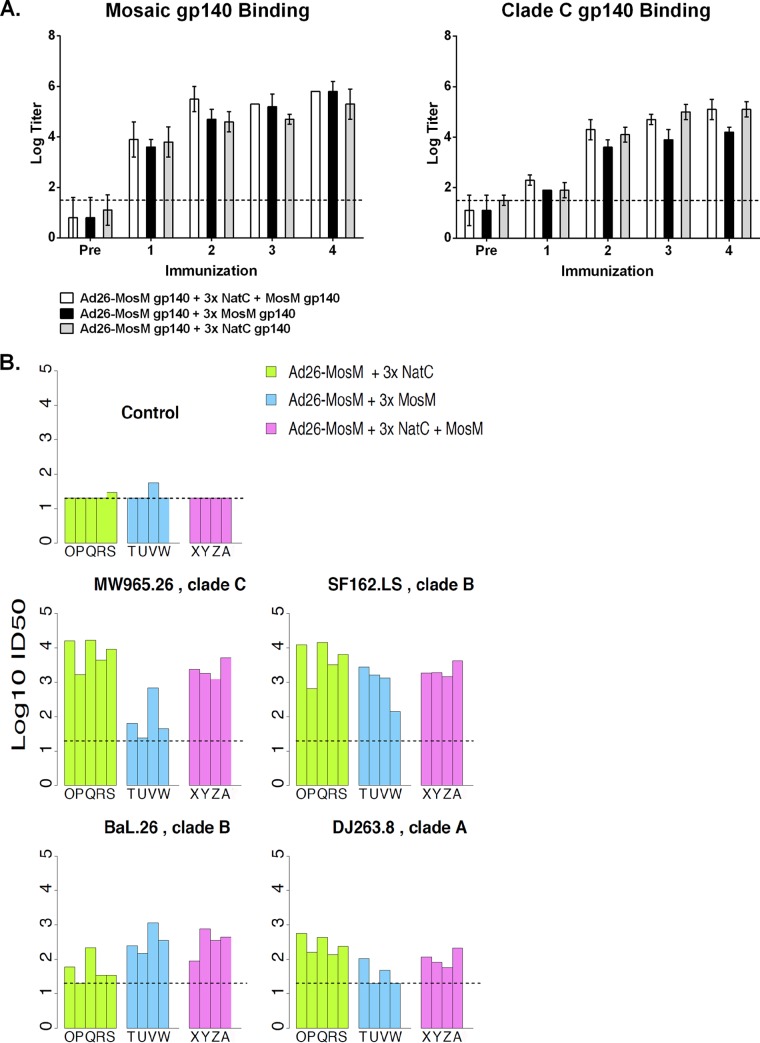

Finally, we assessed nAb responses following priming with a replication-incompetent rAd26 vector expressing the MosM gp140 protein, followed by three protein boosts with the NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM gp140 trimers (Fig. 13; Table 3). This experiment suggests that the mixture of the MosM and NatC trimers was superior to either trimer alone also in the context of a prime-boost vaccine regimen.

FIG 13.

ELISA and TZM.bl nAb responses with heterologous rAd26-prime, protein-boost regimens. (A) Serum obtained 4 weeks after a single priming immunization with rAd26-MosM gp140 and 4 weeks after each NatC, MosM, or MosM+NatC trimer boost was tested in endpoint ELISAs against MosM and NatC trimer antigens. Data are presented as geometric mean titers at each time point ± standard deviations. The dashed line indicates the assay background threshold. (B) Week 20 sera from animals primed with rAd26-MosM gp140 and boosted three times with either the NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM gp140 were tested in the TZM.bl assay against MW965.26, SF162.LS, Bal.26, and DJ263.8. Individual animals are represented by uppercase letters. The top left panel shows a representative MuLV negative control.

TABLE 3.

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination TZM.bl assay comparisona

| Clade | Virus |

P values based on a 2-sided Wilcoxon rank statistic |

Boost pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MosM vs NatC | MosM vs NatC+MosM | NatC vs NatC+MosM | |||

| C | MW965.26 | 0.0079 | 0.014 | 0.19 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ≫ MosM |

| B | SF162.LS | 0.056 | 0.17 | 0.28 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC ∼ MosM |

| B | BaL.26 | 0.018 | 0.88 | 0.018 | NatC+MosM ∼ MosM ≫ NatC |

| A | DJ263.8 | 0.009 | 0.056 | 0.063 | NatC+MosM ∼ NatC > MosM |

The table summarizes comparisons the Env nAb responses in guinea pigs primed with rAd26-MosM gp140 and boosted with either NatC, MosM, or bivalent NatC+MosM trimers. The mean response of the log titers for vaccines MosM and NatC single antigen boost vaccines for each Env differed by more than half a log in each case. ~, response levels were approximately the same between two groups; >, one or two of the groups had higher responses. If the Wilcoxon test indicated that there was a difference in the distributions, and the geometric means were greater than half a log different, the higher response is indicated by “≫.”

DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the biophysical properties, antigenicity, and immunogenicity of a novel, bioinformatically optimized mosaic M gp140 Env trimer. Although this Env sequence was developed by a sliding linear optimization algorithm (12), the MosM gp140 trimer protein proved remarkably robust. It exhibited the expected hydrodynamic radius, marked thermostability, and ability to bind multiple broadly neutralizing MAbs.

The NatC trimer was predicted to be a good immunologic complement to the MosM trimer in terms of theoretical global coverage (Fig. 1). In guinea pigs, the MosM trimer elicited nAbs primarily against clade B viruses, whereas the NatC trimer (17, 18) induced nAbs primarily against clades A and C viruses (Fig. 11; Tables 1 and 2). Mixing the MosM trimer with the NatC trimer resulted in a cocktail that induced nAb responses that were superior to those obtained using either trimer alone. These findings suggest that it may be possible to improve nAb responses with a relatively small number of Env immunogens. However, the development of Env immunogens that can generate cross-clade, tier 2 nAb responses remains a major unsolved challenge for the HIV-1 vaccine field.

Our studies extend previous efforts in the field to develop HIV-1 Env immunogens aimed at increasing nAb breadth. Prior studies have reported the generation of chronic, transmitter/founder, and consensus Envs (25), DNA/Ad prime-boost regimens with multiple diverse Env immunogens (42), polyvalent HIV-1 gp120 Env cocktails delivered by DNA/prime protein-boost regimens (43), and polyvalent DNA/Ad Env immunizations (44). These preclinical studies have highlighted potential benefits of Env cocktails. The feasibility and utility of multivalent Env vaccination have also been explored in clinical trials (45, 46). The current study extends these prior studies and shows that a bivalent combination of the MosM and NatC trimers resulted in improved nAb responses compared with either trimer alone in guinea pigs.

In conclusion, our studies show the production and immunogenicity of a stable mosaic M gp140 Env trimer. Our data suggest that the mosaic M trimer can immunologically complement a natural clade C Env trimer and that the combination of the two trimers results in improved nAb responses compared with either trimer alone. These data suggest that multivalent mixtures of carefully selected trimers may represent a promising strategy to improve nAb breadth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Peng, J. Chen, H. Inganäs, D. Tomkiewicz, H. Verveen, H. van Nes, G. Perdok, K. Hegmans, J. Meijer, R. van Schie, N. Kroos, R. Janson, M. Pau, M. Weijtens, H. Schuitemaker, A. Eerenberg, J. Goudsmit, J. Robinson, J. Mascola, M. Nussenzweig, and D. Burton for generous advice, assistance, and reagents. VRC01 was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

We acknowledge support from NIAID grants AI078526, AI084794, and AI096040, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grants OPP1033091 and OPP1040741, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard.

We declare that we have no financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Barouch DH. 2008. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature 455:613–619. 10.1038/nature07352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlsson Hedestam GB, Fouchier RA, Phogat S, Burton DR, Sodroski J, Wyatt RT. 2008. The challenges of eliciting neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 and to influenza virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:143–155. 10.1038/nrmicro1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. 2010. The role of antibodies in HIV vaccines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28:413–444. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava IK, Ulmer JB, Barnett SW. 2005. Role of neutralizing antibodies in protective immunity against HIV. Hum. Vaccin. 1:45–60. 10.4161/hv.1.2.1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson KE, Barouch DH. 2013. A global approach to HIV-1 vaccine development. Immunol. Rev. 254:295–304. 10.1111/imr.12073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalish ML, Baldwin A, Raktham S, Wasi C, Luo CC, Schochetman G, Mastro TD, Young N, Vanichseni S, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, et al. 1995. The evolving molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 envelope subtypes in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand: implications for HIV vaccine trials. AIDS 9:851–857. 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korber B, Gaschen B, Yusim K, Thakallapally R, Kesmir C, Detours V. 2001. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br. Med. Bull. 58:19–42. 10.1093/bmb/58.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louwagie J, Janssens W, Mascola J, Heyndrickx L, Hegerich P, van der Groen G, McCutchan FE, Burke DS. 1995. Genetic diversity of the envelope glycoprotein from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates of African origin. J. Virol. 69:263–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. 2009. Neutralizing antibodies generated during natural HIV-1 infection: good news for an HIV-1 vaccine? Nat. Med. 15:866–870. 10.1038/nm.1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hraber P, Seaman MS, Bailer RT, Mascola JR, Montefiori DC, Korber BT. 2014. Prevalence of broadly neutralizing antibody responses during chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 28:163–169. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R, Kuiken C, Haynes B, Letvin NL, Walker BD, Hahn BH, Korber BT. 2007. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat. Med. 13:100–106. 10.1038/nm1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barouch DH, O'Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Sun YH, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Lynch DM, Clark SL, Backus K, Perry JR, Seaman MS, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Szinger JJ, Fischer W, Muldoon M, Korber B. 2010. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat. Med. 16:319–323. 10.1038/nm.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santra S, Liao HX, Zhang R, Muldoon M, Watson S, Fischer W, Theiler J, Szinger J, Balachandran H, Buzby A, Quinn D, Parks RJ, Tsao CY, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK, Haynes BF, Korber BT, Letvin NL. 2010. Mosaic vaccines elicit CD8+ T lymphocyte responses that confer enhanced immune coverage of diverse HIV strains in monkeys. Nat. Med. 16:324–328. 10.1038/nm.2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santra S, Muldoon M, Watson S, Buzby A, Balachandran H, Carlson KR, Mach L, Kong WP, McKee K, Yang ZY, Rao SS, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Korber BT, Letvin NL. 2012. Breadth of cellular and humoral immune responses elicited in rhesus monkeys by multi-valent mosaic and consensus immunogens. Virology 428:121–127. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson KE, SanMiguel A, Simmons NL, Smith K, Lewis MG, Szinger JJ, Korber B, Barouch DH. 2012. Full-length HIV-1 immunogens induce greater magnitude and comparable breadth of T lymphocyte responses to conserved HIV-1 regions compared with conserved-region-only HIV-1 immunogens in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 86:11434–11440. 10.1128/JVI.01779-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barouch Dan H, Kathryn Stephenson E, Erica Borducchi N, Smith K, Stanley K, Anna McNally G, Liu J, Abbink P, Lori Maxfield F, Michael Seaman S, Dugast A-S, Alter G, Ferguson M, Li W, Patricia Earl L, Moss B, Elena Giorgi E, James Szinger J, Leigh Eller A, Erik Billings A, Rao M, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Weijtens M, Maria Pau G, Schuitemaker H, Merlin Robb L, Jerome Kim H, Bette Korber T, Nelson Michael L. 2013. Protective efficacy of a global HIV-1 mosaic vaccine against heterologous SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Cell 155:531–539. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs JM, Nkolola JP, Peng H, Cheung A, Perry J, Miller CA, Seaman MS, Barouch DH, Chen B. 2012. HIV-1 envelope trimer elicits more potent neutralizing antibody responses than monomeric gp120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:12111–12116. 10.1073/pnas.1204533109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkolola JP, Peng H, Settembre EC, Freeman M, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, Lynch DM, La Porte A, Simmons NL, Bradley R, Montefiori DC, Seaman MS, Chen B, Barouch DH. 2010. Breadth of neutralizing antibodies elicited by stable, homogeneous clade A and clade C HIV-1 gp140 envelope trimers in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 84:3270–3279. 10.1128/JVI.02252-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman MM, Seaman MS, Rits-Volloch S, Hong X, Kao CY, Ho DD, Chen B. 2010. Crystal structure of HIV-1 primary receptor CD4 in complex with a potent antiviral antibody. Structure 18:1632–1641. 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, McKee K, O'Dell S, Louder MK, Wycuff DL, Feng Y, Nason M, Doria-Rose N, Connors M, Kwong PD, Roederer M, Wyatt RT, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR. 2010. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 329:856–861. 10.1126/science.1187659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frey G, Chen J, Rits-Volloch S, Freeman MM, Zolla-Pazner S, Chen B. 2010. Distinct conformational states of HIV-1 gp41 are recognized by neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:1486–1491. 10.1038/nsmb.1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mascola JR, D'Souza P, Gilbert P, Hahn BH, Haigwood NL, Morris L, Petropoulos CJ, Polonis VR, Sarzotti M, Montefiori DC. 2005. Recommendations for the design and use of standard virus panels to assess neutralizing antibody responses elicited by candidate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccines. J. Virol. 79:10103–10107. 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10103-10107.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seaman MS, Janes H, Hawkins N, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, Giri A, Coffey RT, Harris L, Wood B, Daniels MG, Bhattacharya T, Lapedes A, Polonis VR, McCutchan FE, Gilbert PB, Self SG, Korber BT, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR. 2010. Tiered categorization of a diverse panel of HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses for assessment of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 84:1439–1452. 10.1128/JVI.02108-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmonds TG, Ding H, Yuan X, Wei Q, Smith KS, Conway JA, Wieczorek L, Brown B, Polonis V, West JT, Montefiori DC, Kappes JC, Ochsenbauer C. 2010. Replication competent molecular clones of HIV-1 expressing Renilla luciferase facilitate the analysis of antibody inhibition in PBMC. Virology 408:1–13. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao HX, Tsao CY, Alam SM, Muldoon M, Vandergrift N, Ma BJ, Lu X, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Bowman C, Parks R, Chen H, Blinn JH, Lapedes A, Watson S, Xia SM, Foulger A, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Swanstrom R, Montefiori DC, Gao F, Haynes BF, Korber B. 2013. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of transmitted/founder, consensus, and chronic envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 87:4185–4201. 10.1128/JVI.02297-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates DM. 2010. lme4: mixed-effects modeling with R. http://lme4.r-forge.r-project.org/lMMwR/lrgprt.pdf

- 27.Rodenburg CM, Li Y, Trask SA, Chen Y, Decker J, Robertson DL, Kalish ML, Shaw GM, Allen S, Hahn BH, Gao F, UNAIDS and NIAID Networks for HIV Isolation and Characterization 2001. Near full-length clones and reference sequences for subtype C isolates of HIV type 1 from three different continents. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 17:161–168. 10.1089/08892220150217247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Julien JP, Lee JH, Cupo A, Murin CD, Derking R, Hoffenberg S, Caulfield MJ, King CR, Marozsan AJ, Klasse PJ, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Wilson IA, Ward AB. 2013. Asymmetric recognition of the HIV-1 trimer by broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:4351–4356. 10.1073/pnas.1217537110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen B, Vogan EM, Gong H, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. 2005. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature 433:834–841. 10.1038/nature03327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648–659. 10.1038/31405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, Diskin R, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Pietzsch J, Fenyo D, Abadir A, Velinzon K, Hurley A, Myung S, Boulad F, Poignard P, Burton DR, Pereyra F, Ho DD, Walker BD, Seaman MS, Bjorkman PJ, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. 2011. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 333:1633–1637. 10.1126/science.1207227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, O'Dell S, Patel N, Shahzad-ul-Hussan S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Zhou T, Zhu J, Boyington JC, Chuang GY, Diwanji D, Georgiev I, Kwon YD, Lee D, Louder MK, Moquin S, Schmidt SD, Yang ZY, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Koff WC, Walker LM, Phogat S, Wyatt R, Orwenyo J, Wang LX, Arthos J, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Schief WR, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Kwong PD. 2011. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 480:336–343. 10.1038/nature10696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Protocol GPI, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2009. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326:285–289. 10.1126/science.1178746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardoso RM, Brunel FM, Ferguson S, Zwick M, Burton DR, Dawson PE, Wilson IA. 2007. Structural basis of enhanced binding of extended and helically constrained peptide epitopes of the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody 4E10. J. Mol. Biol. 365:1533–1544. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. 2004. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J. Virol. 78:10724–10737. 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alam SM, McAdams M, Boren D, Rak M, Scearce RM, Gao F, Camacho ZT, Gewirth D, Kelsoe G, Chen P, Haynes BF. 2007. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J. Immunol. 178:4424–4435. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, Ortel TL, Liao HX, Alam SM. 2005. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science 308:1906–1908. 10.1126/science.1111781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reference deleted.

- 39. Reference deleted.

- 40.Montefiori DC. 2009. Measuring HIV neutralization in a luciferase reporter gene assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 485:395–405. 10.1007/978-1-59745-170-3_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ioannou XP, Griebel P, Hecker R, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2002. The immunogenicity and protective efficacy of bovine herpesvirus 1 glycoprotein D plus Emulsigen are increased by formulation with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Virol. 76:9002–9010. 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9002-9010.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seaman MS, Leblanc DF, Grandpre LE, Bartman MT, Montefiori DC, Letvin NL, Mascola JR. 2007. Standardized assessment of NAb responses elicited in rhesus monkeys immunized with single- or multi-clade HIV-1 envelope immunogens. Virology 367:175–186. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Pal R, Mascola JR, Chou TH, Mboudjeka I, Shen S, Liu Q, Whitney S, Keen T, Nair BC, Kalyanaraman VS, Markham P, Lu S. 2006. Polyvalent HIV-1 Env vaccine formulations delivered by the DNA priming plus protein boosting approach are effective in generating neutralizing antibodies against primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from subtypes A, B, C, D and E. Virology. 350:34–47. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakrabarti BK, Ling X, Yang ZY, Montefiori DC, Panet A, Kong WP, Welcher B, Louder MK, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. 2005. Expanded breadth of virus neutralization after immunization with a multiclade envelope HIV vaccine candidate. Vaccine 23:3434–3445. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy JS, Co M, Green S, Longtine K, Longtine J, O'Neill MA, Adams JP, Rothman AL, Yu Q, Johnson-Leva R, Pal R, Wang S, Lu S, Markham P. 2008. The safety and tolerability of an HIV-1 DNA prime-protein boost vaccine (DP6-001) in healthy adult volunteers. Vaccine 26:4420–4424. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S, Kennedy JS, West K, Montefiori DC, Coley S, Lawrence J, Shen S, Green S, Rothman AL, Ennis FA, Arthos J, Pal R, Markham P, Lu S. 2008. Cross-subtype antibody and cellular immune responses induced by a polyvalent DNA prime-protein boost HIV-1 vaccine in healthy human volunteers. Vaccine 26:3947–3957. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59:307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]