Abstract

While only 5% of the human genome is conserved across mammals, a substantially larger portion is biochemically active, raising the question of whether the additional elements evolve neutrally or confer a lineage-specific fitness advantage. To address this question, we integrate human variation information from the 1000 Genomes Project and activity data from the ENCODE Project. A broad range of transcribed and regulatory non-conserved elements show decreased human diversity, suggesting lineage-specific purifying selection. Conversely, conserved elements lacking activity show increased human diversity, suggesting that some recently became non-functional. Regulatory elements under human constraint in non-conserved regions were found near color vision and nerve-growth genes, consistent with purifying selection for recently-evolved functions. Our results suggest continued turnover in regulatory regions, with at least an additional 4% of the human genome subject to lineage-specific constraint.

Initial sequencing of the human genome revealed that 98.5% of human DNA does not code for protein (1), raising the question of what fraction of the remaining genome is functional. Mammalian conservation suggests that ~5% of the human genome (2–3) is conserved due to non-coding and regulatory roles, but more than 80% is transcribed, bound by a regulator, or associated with chromatin states suggestive of regulatory functions (4–6). This discrepancy may result from non-consequential biochemical activity or lineage-specific constraint (7–8). Similarly, evolutionary turnover in regulatory regions (9–11) may be due to non-consequential activity in neutrally-evolving regions in each species, or turnover in functional elements associated with turnover in activity. To resolve these questions, we need new methods for measuring constraint within a species, rather than between species.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within human populations have been identified only every 153 bases per average (12), compared to 4.5 substitutions per site among the genomes of 29 mammals (2), making it impossible to detect individual constrained elements (13). Instead, aggregate measures of human diversity across thousands of dispersed elements are needed. Such measures have been used to show that human constraint correlates with mammalian conservation (4, 14–17), mRNA splice sites (18), regulatory elements (19), and that similar selective pressures act in human and across mammals (2). However, differences between mammalian and human constraint remain unresolved. Recent positive selection has been detected by unexpectedly many recent substitutions (20) or extreme patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and population differentiation (21). However, recent negative selection has not been investigated, as the paucity of variants segregating in the global population makes a selective decrease in the diversity of any given locus indistinguishable from a fortuitous one.

Combining population genomic information from the 1000 Genomes Project (12) and biochemical data of the ENCODE project (5) we estimated constraint associated with diverse genomic functions in aggregate over 1567 Mb of `previously-unannotated' regions encompassing 4.7 million SNPs, excluding exons, proximal promoter regions, and artifact-prone regions (22) (Fig. 1A). On the basis of SNP density, heterozygosity, and derived allele frequency (DAF), we developed a statistical procedure for measuring genome-wide constraint accounting for mutation rate biases and interdependence of allele frequencies due to LD (22). All P values are derived from this test unless otherwise noted. To distinguish whether the increased human constraint in active regions (5) could be due solely to mammalian conservation (Figs. 1B, S1), rather than lineage-specific constraint, we specifically studied regions not conserved across mammals.

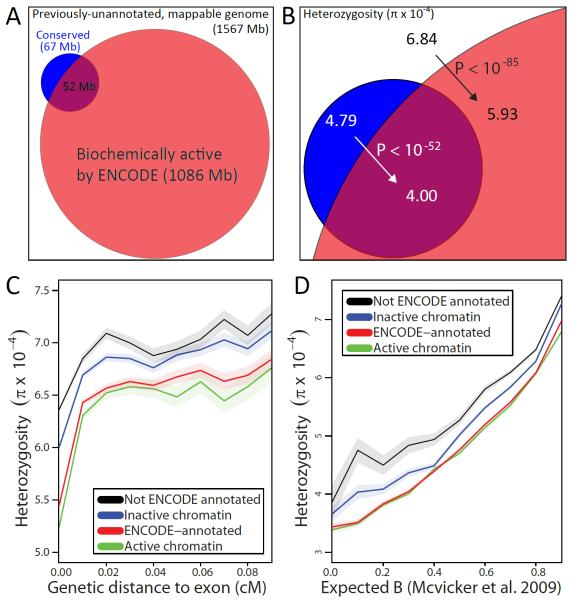

Fig. 1.

(A) Only a small fraction (purple) of biochemically-active regions (red) overlaps conserved elements (blue). (B) Active regions (red) show reduced heterozygosity relative to inactive regions outside conserved elements (white), suggesting lineage-specific purifying selection (black arrow). Conserved elements that lack activity (blue) show increased human heterozygosity relative to active conserved regions (purple), suggesting recent loss of selective constraint (white arrow). (C–D) Comparison of mean heterozygosity for ENCODE-annotated elements (red) vs. non-ENCODE elements (black) and active chromatin (green) vs. inactive (blue) shows a consistent reduction at varying genetic distances from exons (C) and varying expected background selection (D), confirming the heterozygosity reduction is due to purifying selection. Shaded regions represent a 95% confidence interval on the mean heterozygosity assuming independence between bases.

Remarkably, non-conserved active regions showed significant evidence of purifying selection: SNP density was 10% lower (P<10−64), heterozygosity 13% (P<10−85), and DAF 5% (P<10−65), compared to reductions of 28%, 33%, and 16% respectively for conserved regions. As non-conserved regions cover a >10-fold larger fraction of the genome, this suggests that a significant fraction of human constraint lies outside mammalian-conserved regions. The observed decrease in diversity is not due to undetected conserved regions or the threshold used to defined conserved elements (Fig. S2), nor to background selection (23) (Fig. 1C,D), biased gene conversion (Table S1), or decreased mapping to non-reference alleles (22) (Table S2).

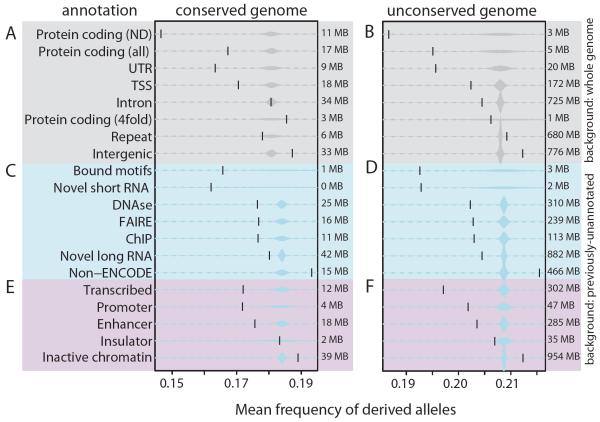

The level of human-specific constraint varies with the observed biochemical activity (Figs. 2, S3–S5, Table S3–S4). Short non-coding RNAs are as strongly constrained as protein-coding regions. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are significantly constrained in human, even though they lack significant mammalian conservation (5), suggesting primarily lineage-specific functions. These results are not explained by local mutation rate variation nor transcription-mediated repair, as DAF is robust to both.

Fig. 2.

Mean frequency of derived alleles (vertical bar) relative to samples of similar size (distribution) from the specified background for previous annotations (grey), ENCODE (blue) and chromatin states (red). Sizes of regions are shown.

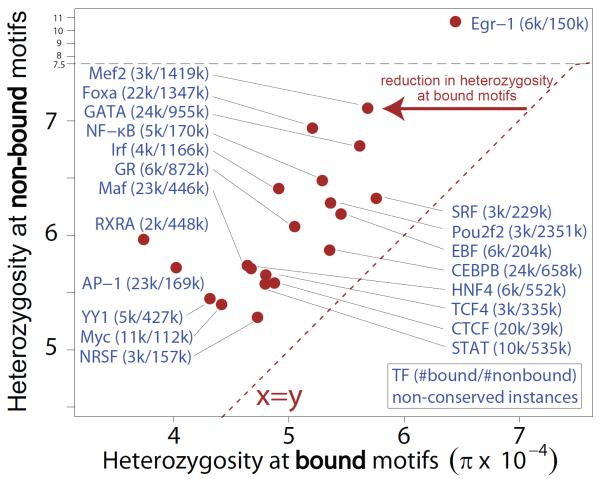

We also found human-specific constraint across non-conserved regulatory features (Fig. 2C,D). Regulatory motifs bound by their regulators show constraint similar to coding regions, and consistently higher than for non-bound instances (P = 9.5 × 10−7, binomial test) (Fig. 3). Regulatory regions defined by different assays, including DNase hypersensitivity and transcription factor binding, show significant and similar levels of human constraint. Different chromatin states (5, 24) show levels of constraint according to their roles (Fig. 2E,F), with promoter states similar to previously-annotated TSS-proximal regions, enhancer states significant but weaker, and insulators similar to background regions, consistent with enhancer and promoter regions requiring a larger number of motifs than insulator regions. In contrast, regions that do not overlap with active ENCODE elements and inactive chromatin states show even lower constraint than ancestral repeats (Fig. 2B,D,F), suggesting they may provide a more accurate neutral reference than repeats that can have exapted functions (25).

Fig. 3.

Average heterozygosity for bound regulatory motif instances (x-axis) and non-bound regulatory motif instances (y-axis), evaluated in non-conserved regions of the genome to estimate lineage-specific constraint. Shown are all transcription factors with at least 30 kb of bound instances (red points). Numbers in parentheses indicate number of bound and number of non-bound instances, respectively.

Comparison with primate constraint suggests evolutionary turnover. Mammalian-conserved regions lacking ENCODE activity show reduced human constraint relative to active regions (SNP density P<10−41, heterozygosity P<10−52, DAF P<10−14) (Fig. 1B, S1), suggesting recent loss in function and activity. These also show higher primate divergence relative to active regions, suggesting some loss of constraint likely predates human-macaque divergence. Conversely, a fraction of lineage-specific elements likely arose in the common ancestor of primates, as human-macaque divergence mirrors human diversity for both active and inactive non-conserved regions (Fig. S6).

To gain insights into the functional adaptations likely involved in this turnover, we applied our aggregation approach to regulatory regions associated with genes of different functions (22). We found that highly-constrained non-conserved enhancers are associated with retinal cone cell development (P<10−4 in GO) and nerve growth (P<10−5 in GO, Reactome, and KEGG; Fig. S7). This evidence of recent purifying selection for regulation of the nervous system and color vision is intriguing given their accelerated evolution in primates (20, 26–27).

We next studied how the number of aggregated regions affects the ability to discriminate functional elements based on their increased human constraint (Fig. S8). We found no discriminative power for individual elements, despite a significant global reduction in heterozygosity (P<10−20, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test on heterozygosity of individual elements), but discriminative power increased significantly as the sample size grew (22).

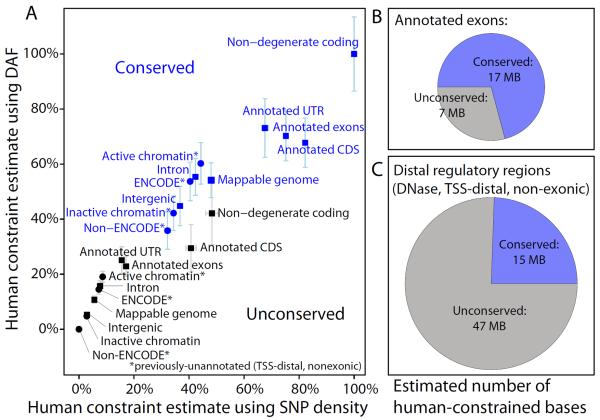

We estimated the proportion of the human genome under constraint (PUC) after correcting for background selection (Fig. S9), and found remarkable agreement between our orthogonal metrics (Fig. 4A). We estimate that an additional 137 Mb (4%) of the human genome is under lineage-specific purifying selection (Table S6), consistent with a recent cross-species extrapolation (28).

Fig. 4.

Estimated proportion of bases under constraint (PUC) in human using SNP density (x-axis) and DAF (y-axis), across previously-annotated elements (squares) and newly-annotated ENCODE elements (circles), in both conserved (blue) and non-conserved (black) regions. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals on the estimates. Each metric was linearly scaled between 0% for non-ENCODE non-conserved regions and 100% for conserved non-degenerate coding positions in each background selection bin separately (Fig. S8)

Our results suggest that almost half of human constraint lies outside mammalian-conserved regions, even though the strength of human constraint is higher in conserved elements. Protein-coding constraint occurs primarily in conserved regions while regulatory constraint is primarily lineage-specific (Fig. S10), as proposed during mammalian radiation (29). While differences in activity between mammals (10–11) can be interpreted as lack of functional constraint (30), our results suggest instead that turnover in activity is accompanied by turnover in selective constraint. A minority of new regulatory elements lie in recently-acquired primate specific regions (5) but the bulk lies in mammalian-aligned regions that provided raw materials for regulatory innovation.

Genome-wide association studies suggest that 85% of disease-associated variants are non-coding (8), a fraction similar to the proportion of human constraint we estimate lies outside protein-coding regions (Table S6). This suggests that mutations outside conserved elements play important roles in both human evolution and disease, and that large-scale experimental assays in multiple individuals, cell types and populations can provide a means to their systematic discovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the ENCODE Project Consortium data producers and the ENCODE Data Analysis Center for coordinating access and performing quality control and peak-calling analysis, the Analysis Working Group of the ENCODE Project Consortium for feedback throughout this project, especially E. Birney, I. Dunham, M. Gerstein, R. Hardison, J. Stamatoyannopoulos, J. Herrero, S. Parker, P. Sabeti, S. Sunyaev, R. Altshuler, P. Kheradpour, J. Ernst, and other members of the Kellis lab for discussions. L.W. and M.K. were funded by NIH grants R01HG004037 and RC1HG005334 and NSF CAREER grant 0644282. Data from the ENCODE consortium is available from the UCSC Genome Browser at http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE and data from the 1000 Genomes Project is available at http://www.1000genomes.org/data/. ENCODE annotations, mammalian constraint, human diversity, background selection, and filtering information for every SNP and every human nucleotide are available at http://compbio.mit.edu/human-constraint/.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: L.D.W. and M.K. designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Lander ES, et al. Nature. 2001 Feb 15;409:860. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Nature. 2011 Oct 27;478:476. doi: 10.1038/nature10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponting CP, Hardison RC. Genome Res. 2011 Nov;21:1769. doi: 10.1101/gr.116814.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birney E, et al. Nature. 2007 Jun 14;447:799. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The ENCODE Project Consortium doi:10.1038/nature11247, (In review)

- 6.Ernst J, et al. Nature. 2011 May 5;473:43. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson MR, et al. Science. 2012 May 17; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindorff LA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jun 9;106:9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe CB, et al. Science. 2011 Aug 19;333:1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1202702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brawand D, et al. Nature. 2011 Oct 20;478:343. doi: 10.1038/nature10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt D, et al. Science. 2010 May 21;328:1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1186176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.1000 Genomes Project Consortium Nature. 2010 Oct 28;467:1061. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eddy SR. PLoS Biol. 2005 Jan;3:e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asthana S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 24;104:12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake JA, et al. Nat Genet. 2006 Feb;38:223. doi: 10.1038/ng1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torgerson DG, et al. PLoS Genet. 2009 Aug;5:e1000592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman S, et al. Science. 2007 Aug 17;317:915. doi: 10.1126/science.1142430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomelin D, Jorgenson E, Risch N. Genome Res. 2010 Mar;20:311. doi: 10.1101/gr.094151.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mu XJ, Lu ZJ, Kong Y, Lam HY, Gerstein MB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Sep 1;39:7058. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard KS, et al. Nature. 2006 Sep 14;443:167. doi: 10.1038/nature05113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabeti PC, et al. Science. 2006 Jun 16;312:1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1124309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. SOM.

- 23.McVicker G, Gordon D, Davis C, Green P. PLoS Genet. 2009 May;5:e1000471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst J, Kellis M. Nat Biotechnol. 2010 Aug;28:817. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bejerano G, et al. Nature. 2006 May 4;441:87. doi: 10.1038/nature04696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorus S, et al. Cell. 2004 Dec 29;119:1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs GH. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;739:156. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1704-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meader S, Ponting CP, Lunter G. Genome Res. 2010 Oct;20:1335. doi: 10.1101/gr.108795.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Nature. 2007 May 10;447:167. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li XY, et al. PLoS Biol. 2008 Feb;6:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. Bioinformatics. 2010 Mar 15;26:841. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrow J, et al. Genome Biol. 2006;7(Suppl 1):S4, 1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karolchik D, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004 Jan 1;32:D493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paten B, et al. Genome Res. 2008 Nov;18:1829. doi: 10.1101/gr.076521.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garber M, et al. Bioinformatics. 2009 Jun 15;25:i54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibbs RA, et al. Science. 2007 Apr 13;316:222. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabriel SB, et al. Science. 2002 Jun 21;296:2225. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartl DL, Clark AG. Principles of population genetics. ed. 4th Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Mass: 2007. p. xv.p. 652. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flicek P, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Nov 28; [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jan;40:D109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Croft D, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Jan;39:D691. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramanian A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 25;102:15545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berglund J, Pollard KS, Webster MT. PLoS Biol. 2009 Jan 27;7:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.