Abstract

The definitive classification or diagnosis of gout normally relies upon the identification of MSU crystals in SF or from tophi. Where microscopic examination of SF is not available or is impractical, the best approach may differ depending upon the context. For many types of research, clinical classification criteria are necessary. The increasing prevalence of gout, advances in therapeutics and the development of international research collaborations to understand the impact, mechanisms and optimal treatment of this condition emphasize the need for accurate and uniform classification criteria for gout. Five clinical classification criteria for gout currently exist. However, none of the currently available criteria has been adequately validated. An international project is currently under way to develop new validated gout classification criteria. These criteria will be an essential step forward to advance the research agenda in the modern era of gout management.

Keywords: gout, classification, urate, research

Introduction

Classification criteria are designed to mimic a gold standard in order to distinguish between disease and no disease or between different diseases. Their purpose is to ensure relative homogeneity of participants of clinical research, including clinical trials and epidemiological studies. Unbiased and reliable classification criteria are essential for research in rheumatic disease. Specific recommendations exist regarding the development and validation of classification criteria for rheumatic disease [1]. Development requires identification of possible inclusion and exclusion criteria. A large sample of patients with and without disease should be studied to determine which criteria (or combination of criteria) best differentiate those with and without disease. The final classification criteria should then be validated in a large sample of cases and controls distinct from patients used to develop the criteria.

Why do we need gout classification criteria?

The classification of a patient as having gout normally relies upon the identification of MSU crystals in SF or tissue [2]. Where examination of SF is impractical, the best approach differs depending on the context: in clinical management of individual patients, all available information should be carefully weighed and considered by the physician, whereas in clinical research, classification criteria are necessary.

Important advances have been made that emphasize the need for robust gout classification criteria. These advances include new (and expensive) pharmaceuticals and the need for accurate case definition for recruitment into clinical trials; the advent of new imaging modalities that have the potential to change the way gout is classified and the need for accurate phenotyping for large genetic studies, such as genome-wide association studies. Because of potential anticipated as well as unknown adverse effects of new agents for gout (including biologics), classification criteria need to have acceptably high specificity to ensure trial enrolment is targeting those with definite gout. At the same time, with the rise in the incidence/prevalence of gout worldwide, uniform criteria with appropriate sensitivity and specificity are needed for epidemiological studies as well as phenotyping for genetic studies. New imaging modalities that were not available when prior criteria were developed need to be evaluated for their utility in aiding accurate classification of persons with gout.

Limitations of current gout classification criteria

There have been five published classification criteria for gout [3–7] (Table 1). None of the published gout criteria meet the requirements for valid classification criteria (Table 2). The Rome and New York criteria [3, 4] identify key features of gout but were not developed through observed prospective data and have been tested only to a limited extent. A study of 22 patients with clinically diagnosed gout in Sudbury, Massachusetts, found that 8 patients satisfied the Rome criteria only, 4 satisfied the New York criteria only and 10 satisfied both sets (sensitivity of 0.82 and 0.64 for the Rome and New York criteria, respectively) [8]. A much larger study of consecutive rheumatology clinic attendees from six European centres (59 patients with gout and 761 patients with other rheumatic diseases) reported that the specificity of both sets were very high (0.99 for both Rome and New York criteria) but the sensitivity was not (0.64 and 0.80 for the Rome and New York criteria, respectively) [9]. The inclusion of tophi as key features may limit the sensitivity of these criteria in patients in early disease, since only 31% of patients with gout had a definite tophus in the larger study.

Table 1.

Published gout classification criteria

| Rome 1963 [3] |

| 1. Serum uric acid >7 mg/dl in men and >6 mg/dl in women |

| 2. Presence of tophi |

| 3. MSU crystals in SF or tissue |

| 4. History of attacks of painful joint swelling with abrupt onset and resolution within 2 weeks |

| Case definition: Two or more of any criteria. |

| New York 1966 [4] |

| 1. At least two attacks of painful joint swelling with complete resolution with 2 weeks |

| 2. A history or observation of podagra |

| 3. Presence of tophi |

| 4. Rapid response to colchicine treatment, defined as a major reduction in the objective signs of inflammation within 48 h |

| Case definition: Two or more of any criteria or presence of MSU crystals in SF or on deposition. |

| ARA preliminary classification criteria for acute gout 1977 [5] |

| 1. More than one attack of acute arthritis |

| 2. Maximum inflammation developed within 1 day |

| 3. Oligoarthritis attack |

| 4. Redness observed over joints |

| 5. First MTP joint painful or swollen |

| 6. Unilateral first MTP joint attack |

| 7. Unilateral tarsal joint attack |

| 8. Tophus (suspected or proven) |

| 9. Hyperuricaemia (more than 2 s.d. greater than the normal population average) |

| 10. Asymmetric swelling within a joint on X-ray |

| 11. Subcortical cysts without erosions on X-ray |

| 12. Complete termination of an attack |

| Case definition: 6 of 12 clinical criteria required or presence of MSU crystals in SF or in tophus. |

| Mexico 2010 [6] |

| 1. Current or past history of more than one attack of arthritis |

| 2. Rapid onset of pain and swelling (less than 24 h) |

| 3. Mono and/or oligoarticular attacks |

| 4. Podagra |

| 5. Joint erythema |

| 6. Unilateral tarsal joint attack |

| 7. Tophus (suspected or proven) |

| 8. Hyperuricaemia (more than 2 s.d. greater than the normal population average) |

| Case definition: MSU crystal identification or four of eight criteria required. |

| Netherlands 2010 [7] |

| 2 Male sex |

| 2 Previous patient-reported arthritis attack |

| 0.5 Onset within 1 day |

| 1 Joint redness |

| 2.5 MTP1 involvement |

| 1.5 Hypertension or more than one cardiovascular disease |

| 3.5 Serum uric acid level > 5.88 mg/dl |

| 13 Presence of a tophus |

| Case definition: Each item contributes its weighted score as shown. A summed score of 4 or less excludes gout; 8 or more suggests gout; between 4 and 8 suggests the need for SF analysis. |

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of current gout classification criteria

| Criteria | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Crystal-proven gout used to define cases in development of criteria? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rome 1963 [3] | 0.64–0.82 | 0.99a | No |

| New York 1966 [4] | 0.64–0.80 | 0.99a | No |

| ARA 1977 [5] | 0.70–0.85 | 0.64–0.97 | No |

| Mexico 2010 [6] | 0.88–0.97 | 0.96 | No |

| Netherlands 2010 [7] | Not reported | Not reported | Yes |

aWhen MSU crystal identification included in the definition.

The 1977 ARA criteria, now more than 30 years old, were informed by data to identify the acute arthritis of primary gout [5] (Table 1). Survey criteria that do not require joint aspiration were also described for use in epidemiological studies (11 items). The cases and controls were drawn from 706 patients submitted by 38 rheumatologists across the USA. Only patients with RA, acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis and acute septic arthritis were accepted as controls. Important disease mimics including OA and PsA were not included. The gold standard chosen for the classification criteria was physician diagnosis. Many patients had incomplete data (for example, approximately half of the cases and the controls did not have SF analysis). The observed performance of the proposed clinical criteria that do not require joint or tophus aspiration was sensitivity 85% and specificity 97%. External validation of the clinical components of ARA criteria against a gold standard of SF analysis has been reported in two studies [10, 11]. In these studies, the sensitivity was 70% and 80% and specificity was 79% and 64%. In contrast, in patients with crystal proof, the sensitivity of two of three clinical components of the Rome criteria was 67% and specificity was 89% [10].

These results underscore the need for better criteria and that the gold standard for diagnosis remains identification of MSU crystals in SF, preferably in the acute phase. Notwithstanding the problems of classification for acute gouty arthritis, there is also a need for classification criteria for intercritical or chronic gout. In most clinical research settings, participants will not have acute gout at the time of evaluation, so it is clearly necessary to develop classification criteria that do not require current evidence of active joint inflammation.

There have been two further criteria recently proposed for diagnosis, not classification, developed in Mexico and the Netherlands [6, 7] (Table 1). The study from Mexico considered only patients with physician-diagnosed gout from rheumatology clinics. It proposed a simplified version of the 1977 ARA criteria based on the frequency of the items present in this population of patients. Because there were no control patients, the specificity of the suggested criteria could not be determined. A second study from this group showed a very high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (96%) in rheumatology clinic patients with crystal-proven gout and other rheumatic diseases (OA, SpA and RA) [12]. However, the non-gout control patients in this study did not undergo SF analysis and the high rate of tophi (81%) in the gout cases limit general applicability. The Dutch study aimed to develop a diagnostic decision aid for general practitioners, rather than classification criteria. The patients for this study were required to have monoarthritis, so that the decision rule is not applicable to patients who present with more than one affected joint. Discriminating features included risk factors for gout (such as serum urate levels, male gender and cardiovascular disease) rather than actual manifestations of gout.

MSU crystal identification: the gold standard

For most rheumatic diseases, a pathological diagnosis is not available and the gold standard is often expert physician judgement (ideally made over a reasonable follow-up duration). This is not the case in gout, where the identification of tissue or SF MSU crystals is considered pathognomonic and the gold standard for diagnosis. Although the pathological diagnosis of gout through identification of MSU crystals is a major advantage when developing gout classification criteria, this gold standard does have its limitations. Most importantly, MSU crystal identification is dependent on an operator who requires adequate training in SF crystal analysis [13, 14]. Other joint crystals and artefacts may mimic MSU crystals, and both false-positive and false-negative results may occur [15–17]. Another important consideration is that SF MSU crystals are present in a proportion of patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia; that is, elevated serum urate concentrations without overt clinical manifestations of gout [18, 19]. Whether these people should be considered as having gout can be debated. MSU crystals may also be present in patients presenting with joint inflammation due to concomitant rheumatic conditions, including septic arthritis, acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis, PsA and rarely RA, but these patients should still be classified as having gout, but with confounding features. Following long-term intensive urate-lowering therapy, a negative urate balance is reached and MSU crystals will become undetectable [20]. A further barrier to crystal identification may be expertise in joint aspiration; while joint aspiration is standard in secondary rheumatology care, these skills may not be universally present in primary care where most gout is diagnosed and managed. Furthermore, gout frequently presents in small joints that may be poorly accessible to joint aspiration. Therefore inclusion of MSU crystal identification as the gold standard for classification development risks oversampling patients with large joint arthropathy or tophaceous gout (if tophi are easily accessible for aspiration), which may be a source of bias when developing classification criteria using MSU crystals as the gold standard.

Imaging considerations

The 1977 ARA classification criteria for the acute arthritis of primary gout include plain radiographic changes of asymmetric swelling within a joint and subcortical cysts without erosions [5]. These changes may be observed in conditions other than gout and are a late feature of disease [21]. Other plain radiographic features of gout such as soft-tissue opacifications with densities between soft tissue and bone, articular and periarticular bone erosions and osteophytes at the margins of opacifications or erosions have low sensitivity (31%) but high specificity (93%) for a clinical diagnosis of gout [22].

No published classification criteria include advanced imaging techniques for the detection of gout. Recent reports suggest that US and dual energy computed tomography (DECT) may allow accurate identification of some patients with gout. The double contour sign on US is defined as a hyperechoic band over anechoic cartilage [23] and is thought to represent MSU crystals coating articular cartilage [24]. A number of different groups have reported that the presence of the double contour sign on US has high specificity for gout (95–100%) with variable sensitivity (21–92%) [22, 23, 25–28]. Only a few imaging studies have used microscopically proven disease as a gold standard [23, 26]. A complicating issue is that these US features can also be present in people with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia [18, 28, 29]. DECT is a recently developed imaging method that allows visualization of urate deposits through detection of the chemical composition of urate. High sensitivity and specificity has been reported for crystal-proven gout by several groups [30–33]. It should be noted that most advanced imaging studies have examined the classification accuracy in patients with established disease, where joint aspirate could be achieved or other clinical criteria would be satisfied. False-negative cases have been reported [34]. The role of these techniques for gout classification in patients with early disease and any additional benefit over microscopic or clinical criteria requires careful consideration.

Scope of gout classification criteria

The purpose of classification criteria is to robustly define cases of gout for the purposes of research. It is not intended that these criteria be used for gout diagnosis in clinical practice. In clinical practice the diagnosis of gout should be made by microscopy, and if this is not possible, a tentative clinical diagnosis is made taking into account history, examination, imaging and laboratory findings in an individualized manner. Gout may present in a number of different ways: recurrent flares, chronic gouty arthropathy and tophaceous disease. Gout classification criteria should accurately capture patients with these various disease states. However, the scope of classification criteria does not include definition of these disease states in patients with gout. Furthermore, the classification of gout applies to patients with clinical features of gout and does not aim to define a pre-gout state that may potentially be characterized by deposition of urate crystals in the absence of clinical manifestations.

A strategy to develop new gout classification criteria

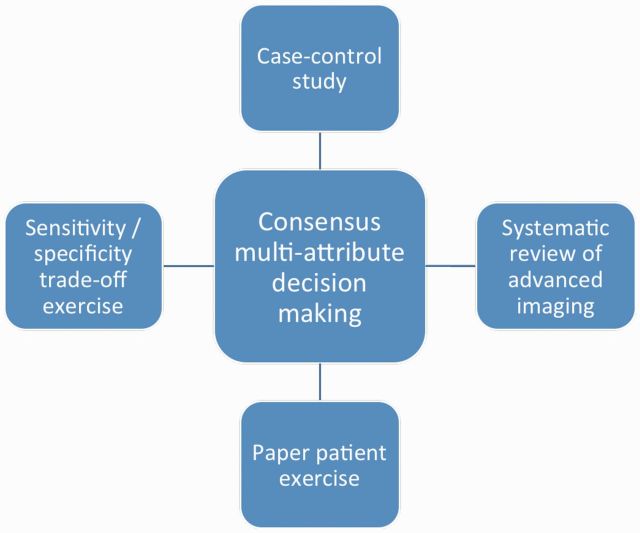

The ACR and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have recently funded an international project to develop new gout classification criteria. The intent of criteria derived from this work is to improve the case definition for gout among both primary and secondary care populations. The intended use of classification criteria in this setting includes case ascertainment for recruitment into clinical studies, including observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Following item generation processes involving both physicians and patients [35], two parallel approaches will be used to determine the key combination of elements that best define gout. The first approach will involve prospectively recruiting 860 patients with suspected gout into a multicentre international study. All participants will have synovial or tissue analysis (by an observer certified in crystal identification) to determine true status classification. The second approach will be a paper patient exercise where 30 patient profiles that represent a spectrum of gout probability will be ranked by an expert panel. Additional data will be a systematic review of the diagnostic utility of advanced imaging for gout and analysis of trade-offs of sensitivity and specificity for different contexts of classification. A structured consensus process will then integrate these sources of data into agreed classification criteria. The overall project strategy is shown schematically in Fig.1. The final criteria will be in a format similar to the 2010 ACR/EULAR RA criteria [36]. It is possible that different but equivalent versions of criteria will be recommended (with or without advanced imaging). The final criteria will be externally validated using a test sample from the multicentre international study and an existing primary care dataset.

Fig. 1.

Gout classification project structure.

Summary

Gout is now the most common inflammatory arthritis [37]. The increasing prevalence of gout, advances in therapeutics and the development of large international research collaborations to understand the impact, mechanisms and optimal treatment of this condition emphasize the need for accurate and robust classification criteria for this disease. These criteria will be an essential step forward to progress the research agenda in the modern era of gout management.

Rheumatology key messages.

Unbiased and reliable classification criteria are essential for research in rheumatic disease.

Current classification criteria for gout are limited by low sensitivity and incomplete validation.

An international project is under way to develop classification criteria that closely mimic crystal-proven gout.

Acknowledgements

The authors are members of the Gout Classification Project Steering Committee.

Funding: This work is funded by the ACR and EULAR.

Disclosure statement: N.D. has received consultancy fees from Takeda, Ardea, Novartis, Fonterra and Metabolex. She has received speaker fees from Savient and Novartis and grant support from Fonterra. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Singh JA, Solomon DH, Dougados M, et al. Development of classification and response criteria for rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:348–52. doi: 10.1002/art.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1301–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellgren JH, Jeffery MR, Ball JF. The epidemiology of chronic rheumatism. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Decker JL. Report from the subcommittee on diagnostic criteria for gout. In: Bennett PH, Wood PHN, eds. Population studies of the rheumatic diseases. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium, New York, June 5–10, 1966. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica Foundation, 1968:385–7.

- 5.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895–900. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelaez-Ballestas I, Hernandez Cuevas C, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. Diagnosis of chronic gout: evaluating the American College of Rheumatology proposal, European League against Rheumatism recommendations, and clinical judgment. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1743–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssens HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1120–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Sullivan JB. Gout in a New England town. A prevalence study in Sudbury, Massachusetts. Ann Rheum Dis. 1972;31:166–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.31.3.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rigby AS, Wood PHN. Serum uric acid levels and gout: what does this herald for the population? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:395–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malik A, Schumacher HR, Dinnella JE, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid crystal analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:22–4. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181945b79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Limited validity of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for classifying patients with gout in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;69:1255–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez-Mellado J, Hernandez-Cuevas CB, Alvarez-Hernandez E, et al. The diagnostic value of the proposal for clinical gout diagnosis (CGD) Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1873-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher HR, Chen LX, Mandell BF. The time has come to incorporate more teaching and formalized assessment of skills in synovial fluid analysis into rheumatology training programs. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1271–3. doi: 10.1002/acr.21714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schumacher HR, Chen LX, Zhang LY. Diagnosis of crystal-associated disease: where do we stand? Bioanalysis. 2011;3:1081–3. doi: 10.4155/bio.11.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon C, Swan A, Dieppe P. Detection of crystals in synovial fluids by light microscopy: sensitivity and reliability. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:737–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.9.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schumacher HR, Reginato AJ. Atlas of synovial fluid analysis and crystal identification. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen TL, Rasker JJ. Therapeutic consequences of crystals in the synovial fluid: a review for clinicians. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:1032–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Miguel E, Puig JG, Castillo C, et al. Diagnosis of gout in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: a pilot ultrasound study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:157–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouault T, Caldwell DS, Holmes EW. Aspiration of the asymptomatic metatarsophalangeal joint in gout patients and hyperuricemic controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:209–12. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, et al. Treatment of chronic gout. Can we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout? J Rheumatol. 2001;28:577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama DA, Barthelemy C, Carrera G, et al. Tophaceous gout: a clinical and radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:468–71. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rettenbacher T, Ennemoser S, Weirich H, et al. Diagnostic imaging of gout: comparison of high-resolution US versus conventional X-ray. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:621–30. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0802-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiele RG, Schlesinger N. Diagnosis of gout by ultrasound. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1116–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grassi W, Meenagh G, Pascual E, et al. ‘Crystal clear’—sonographic assessment of gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright SA, Filippucci E, McVeigh C, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography of the first metatarsal phalangeal joint in gout: a controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:859–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottaviani S, Richette P, Allard A, et al. Ultrasonography in gout: a case-control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippucci E, Riveros MG, Georgescu D, et al. Hyaline cartilage involvement in patients with gout and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. An ultrasound study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:178–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard RG, Pillinger MH, Gyftopoulos S, et al. Reproducibility of musculoskeletal ultrasound for determining monosodium urate deposition: concordance between readers. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1456–62. doi: 10.1002/acr.20527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pineda C, Amezcua-Guerra LM, Solano C, et al. Joint and tendon subclinical involvement suggestive of gouty arthritis in asymptomatic hyperuricemia: an ultrasound controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R4. doi: 10.1186/ar3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi HK, Al-Arfaj AM, Eftekhari A, et al. Dual energy computed tomography in tophaceous gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1609–12. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi HK, Burns LC, Shojania K, et al. Dual energy CT in gout: a prospective validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:466–71. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glazebrook KN, Guimaraes LS, Murthy NS, et al. Identification of intraarticular and periarticular uric acid crystals with dual-energy CT: initial evaluation. Radiology. 2011;261:516–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bongartz T, Glazebrook KN, Kavros SJ, et al. Diagnosis of gout using dual-energy computed tomography: an accuracy and diagnostic yield study. Chicago, IL: American College of Rheumatology Annual Scientific Meeting, November 4–9, 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glazebrook KN, Kakar S, Ida CM, et al. False-negative dual-energy computed tomography in a patient with acute gout. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:138–41. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318253aa5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prowse RL, Dalbeth N, Kavanaugh A, et al. A Delphi exercise to identify characteristic features of gout—a study of opinions from patients and physicians, as the first stage in developing new classification criteria for gout. J Rheumatol. 2013 doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121037. Feb 15 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41. doi: 10.1002/art.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]