Abstract

Recent genome-wide analyses in human lung cancer revealed that EPHA2 receptor tyrosine kinase is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and high levels of EPHA2 correlate with poor clinical outcome. However, the mechanistic basis for EPHA2-mediated tumor promotion in lung cancer remains poorly understood. Here we show that the JNK/c-JUN signaling mediates EPHA2-dependent tumor cell proliferation and motility. A screen of phospho-kinase arrays revealed a decrease in phospho-c-JUN levels in EPHA2 knockdown cells. Knockdown of EPHA2 inhibited p-JNK and p-c-JUN levels in approximately 50% of NSCLC lines tested. Treatment of parental cells with SP600125, a JNK inhibitor, recapitulated defects in EPHA2-deficient tumor cells; whereas constitutively activated JNK mutants were sufficient to rescue phenotypes. Knockdown of EPHA2 also inhibited tumor formation and progression in xenograft animal models in vivo. Furthermore, we investigated the role of EPHA2 in cancer stem-like cells. RNAi-mediated depletion of EPHA2 in multiple NSCLC lines decreased the ALDH positive cancer stem-like population and tumor spheroid formation in suspension. Depletion of EPHA2 in sorted ALDH positive populations markedly inhibited tumorigenicity in nude mice. Furthermore, analysis of a human lung cancer tissue microarray revealed a significant, positive association between EPHA2 and ALDH expression, indicating an important role for EPHA2 in human lung cancer stem-like cells. Collectively, these studies revealed a critical role of JNK signaling in EPHA2-dependent lung cancer cell proliferation and motility and a role for EPHA2 in cancer stem-like cell function, providing evidence for EPHA2 as a potential therapeutic target in NSCLC.

Keywords: receptor tyrosine kinase, EPHA2, JNK, c-JUN, non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Recent technological advances in analyzing the human cancer genome permit the study of gene copy number, expression level, and mutation status in human tumor tissue. These studies uncovered previously unknown genetic alterations and aberrant expression in the genes encoding Eph receptor tyrosine kinases (1, 2). EPH receptors belong to a large family of RTKs. Since their discovery in the 90s, EPH molecules have been increasingly recognized as key regulators of both normal development and disease [reviewed in (3–5)]. The EPH receptor family can be divided into two subclasses, EPHA and EPHB, based on sequence similarity and preference for binding either the GPI-anchored EPHRIN-A ligands or the transmembrane EPHRIN-B ligands. Both A and B class EPH molecules are single transmembrane-spanning domain receptors with distinct domains for ligand binding, receptor clustering, and signaling. Binding of EPHRINS to EPH receptors induces receptor clustering and activation. In addition to ligand-induced receptor activities, EPH receptors can also be activated by other cell-surface receptors, such as EGFR and ERBB2 (6, 7). Multiple intracellular signaling pathways have been linked to EPH receptors, including RAS/RAF/MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, SRC, FAK, ABL, and RHO/RAC/CDC42 [reviewed in (3–5)].

Analyses of the lung cancer genome revealed that both mRNA and protein levels of EPHA2 are elevated and high levels of EPHA2 correlate with smoking, K-RAS mutation, brain metastasis, disease relapse, and poor patient survival in several studies with large numbers of human tumor samples [reviewed in (1), (8–10)]. In addition, a gain-of-function EPHA2 mutation has also been identified in human squamous lung cancer specimens (10), suggesting an oncogenic role for EPHA2 in lung cancer. Overexpression of EPHA2 in BEAS-2B immortalized lung epithelial cell line increased colony formation in soft agar, decreased FAS ligand-mediated apoptosis, and increased invasion in transwell assays (10). In a separate study, EPHRIN-A1 ligand stimulation in multiple NSCLC lines reduced colony size in clonogenic growth assay and decreased motility in a wound closure assay, suggesting that tumor promoting function of EPHA2 receptor in lung cancer is ligand-independent (11). Although these early studies established a role for EPHA2 in tumor promotion in cultured lung cancer cells, the in vivo role and mechanistic basis of EPHA2 in these cancer cells remain poorly understood. In addition, the potential role of EPHA2 in lung cancer stem-like cells (CSC) has not been investigated.

In this study, we sought to establish the mechanism of action for EPHA2-mediated tumor promotion in multiple NSCLC lines. We used antibody arrays to identify EPHA2 downstream targets, and a combination of shRNA-mediated gene silencing, small molecule kinase inhibitor, and rescue of the knockdown phenotype by expressing constitutively activated mutants for target validation. Furthermore, we analyzed the role of EPHA2 in lung cancer stem-like population. Collectively, these studies established mechanistic basis for EPHA2-dependent lung cancer cell proliferation, motility, and cancer stem-like cell function, and provided evidence for EPHA2 as a potential therapeutic target in NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, plasmids, and reagents

Human NSCLC cell lines were provided by the Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) in lung cancer at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. The cell lines were validated with DNA finger printing through the Vanderbilt Technology for Advanced Genomics Core facility in the fall of 2013. They were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Human EPHA2 cDNA was obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL) and subcloned into pCLXSN retroviral vector containing Neomycin gene for G418 selection. Human c-JUN cDNA and constitutively activated JNK1 and JNK2 were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA) and subcloned into pCLXSN retroviral vector. Hairpin shRNAs targeting human EPHA2 were purchased from Open Biosystems. JNK inhibitor SP600125 was purchased from Cell Signaling (Denvers, MA). Human Phospho-kinase antibody array and Lung cancer tissue microarray were purchased from R&D System (Minneapolis, MN) and US Biomax (Rockville, MD), respectively.

Lentiviral shRNA knockdown and retroviral overexpression experiments

shRNA construct in the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector containing the following EPHA2 targeting sequence was used: 5′-CGGACAGACATATGGGATATT-3′. Vector control (pLKO.1) or EPHA2 shRNA lentiviral particles were produced by co-transfection of HEK 293T cells with targeting plasmids and packaging vectors, psPAX2 and pMD.2G, using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Viral supernatants were collected by centrifugation and were used to infect NSCLC cells for 24 hours. Cells were changed to new growth medium for another 24 hours, followed by puromycin selection (2 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, ST. Louis, MO) for 3–5 days.

Retroviruses carrying vector (pCLXSN), pCLXSN-EPHA2, pCLXSN-JNK-CA, or pCLXSN-c-JUN were produced by co-transfection of HEK293T cells with overexpression plasmids and packaging vector, pCLAmpho. Viral supernatants were used to infect NSCLC cells, followed by selection of 800 μg/ml G418 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 days.

Cell growth Assays

Cell growth was measured by MTT, colony formation, and BrdU assays. For MTT assay, 2.5×103 cells were plated into each well of 96-well plate in 100μl of complete growth medium. JNK inhibitor was added on the second day after cell attachment. Cell viability was measured by incubating cells with 20μl of 5 μg/ml Tetrazolium salt 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified by reading absorbance at 590 nm using Microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). For colony formation assay, 200 or 400 cells in complete growth medium were plated into each well of a 12-well plate. Cells were growing for 10–14 days, and the medium was changed every three days. At the end of the experiment, cell colonies were stained with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) and the foci were photographed. For BrdU incorporation assay, 2×104 cells/well in complete growth medium were plated onto matrigel coated 2-well LabTekII chamber slide. Cells were starved for 20 hours, followed by 10 μg/ml BrdU labeling in the presence of 0.5% FBS for 16 hours. BrdU detection was performed using BrdU staining kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). BrdU positive cells were enumerated in four random fields, at 40× magnification, per chamber and proliferation index was calculated as the percentage of BrdU+ nuclei/total nuclei.

Apoptosis assay

Tumor cells were serum starved for 48 hours and apoptosis measured by Annexin V-FLUOS Staining Kit (Roche) per manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, cells were gently trypsinized and washed once with serum containing medium. Cell suspensions were incubated with Annexin-V-Fluorescein and Propidium idodide to detect phosphoserine on the outer leaflet of apoptotic cell membranes and to differentiate from necrotic cells, respectively. Annexin-V Fluorescein labeled cells were detected by FACS analysis. For tumor xenografts, apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay on tumor sections, as described previously (12).

Transwell migration assay

Tumor cell migration was assessed by a modified Boyden chamber assay using 8mm pore size Transwell (Costar). The transwell inserts were pre-treated with 1% BSA in Opti-MEMI medium for 30 minutes. Tumor cells (1×104 of H1975, 2 ×104 of A549, or 3 ×104 of H1650 for 24hr migration, and 2×104 of H1975, 4 ×104 of A549 for 6hr migration) were plated on top of the transwell. Growth medium was added to the lower chamber and cells were allowed to migrate for 6 or 24 hours. Cells that passed through the transwell membrane and stayed on the bottom of membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet, photographed and counted.

Screen of phospho-kinase array

Human phospho-kinase antibody arrays were purchased from R&D system (Catalog # ARY003). Capture antibodies were pre-spotted in duplicate on nitrocellulose membranes by the manufacturer. Membranes were incubated with blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Cell lysates derived from control and EPHA2 knockdown H1975 cells (500 μg protein) were mixed with a cocktail of biotinylated detection antibodies. The sample/antibody mixture was then incubated with the array overnight at 4°C, followed by three washes in washing buffer. Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase and chemiluminescent detection reagents were subsequently added and chemiluminescence was detected in the same manner as a Western blot. Densitometry was performed on scanned blots using NIH Image J software version 1.45 to quantify the average pixel density/spotted area after normalization to the pixel density of the background controls. Data are representation of two independent experiments.

Tumor Sphere assay

Cells (0.5×104/well for A549, 1×104/well for H1975) were plated into 6-well plates with ultra-low attachment surface in serum-free medium DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with commercial hormone mix B27 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), EGF (20 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), bFGF (20 ng/ml, R&D Systems), and heparin (2 μg/ml, Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Floating sphere cultures were kept for 7–9 days. EGF and bFGF were replenished every 3 days. Plates were scanned and numbers of tumor sphere per well were enumerated automatically using The GelCountTM system (Oxford Optronix, United Kingdom).

Antibodies, western blot analysis and immunofluorescence

Antibodies against the following proteins were used: EPHA2 (1:1000, D7, Millipore, Temecula, CA); EPHA2 (1:1000, c-20), ACTIN (1:1000, I-19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); pThr183/Tyr185 SAPK/JNK, SAPK/JNK, pSer63-c-JUN, c-JUN, pSer473 AKT, AKT, pThr202/Tyr204 ERK, ERK, pSer235/236 pS6, S6, NOTCH3, SOX2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); ALDH (1:5000, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Western blot analyses were performed by standard methods using indicated antibodies. Densitometry was performed on scanned blots using NIH Image J software version 1.45 to quantify the average pixel density/band area after normalization to the pixel density of the corresponding loading controls. Data are representation of 3–4 independent experiments.

For immunofluorescence studies, 2×104 cells were plated onto matrigel coated 2-well LabTekII chamber slide. Cells were fixed next day with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and blocked with 0.3% Triton X-100, 3% BSA in PBS, followed by incubation with anti-p-c-JUN (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. The primary antibody was detected by incubation with the Alexa-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen, Life Technologies) for 1 hour at room temperature. The slides were mounted with ProLong Antifade reagent with Dapi (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) and photographed.

Immunohistochemistry

Lung cancer tissue microarray (TMA) (US Biomax, Rockville, MD) or xenograft tumor sections from A549 and H1975 cells were stained by immunohistochemistry as described previously (13). Briefly, rehydrated paraffin sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in citrated buffer (2 mM citric acid, 10 mM sodium citrated, pH 6.0) using the PickCell Laboratories 2100 Retriever. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked by 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes. Sections were incubated with blocking solution and stained with primary antibodies (anti-EPHA2 1:25, anti-p-c-JUN 1:100, anti-ALDH 1:100) overnight at 4°C. Sections were subsequently washed and stained with biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by avidin-peroxidase reagent and DAB substrate. After hematoxylin counterstain, sections were mounted and photographed on an Olympus BX60 microscope using a digital camera and NIH Scion Image software.

For quantification of lung cancer TMAs, relative expression was scored using a continuous scale as follows: 0 = 0–10% positive tumor epithelium, 1 = 10–25% positive tumor epithelium, 2 = 25–50% positive tumor epithelium, and 3 = >50% positive tumor epithelium/core. TMA cores were scored blind by three independent individuals, the average of which was reported here. Differential expression between tissue samples and correlation between EPHA2 and ALDH expression were quantified and statistically analyzed using the Chi square analysis.

In vivo tumor studies

8-week-old nude mice were purchased from Harlan-Sprague-Dawley and used for vivo tumor evaluation. The animals were housed under pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were performed in accordance with the Association and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International guidelines and with approval by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To evaluate the role of EPHA2 on tumor growth, 2.5×106 EPHA2 knockdown cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of the nude mice, and the same numbers of vector control cells were injected contralaterally. Tumor progression was monitored by palpation and tumor size measured by a digital caliper. At the end of the 4 weeks, tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: volume=length×width2×0.52.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

The cell profile of ALDH was determined by flow cytometry analysis using the Aldefluor assay kit (Stem Cell Technologies) per manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, cells were incubated in Aldefluor assay buffer containing efflux inhibitor and the ALDH substrate. Cells that could catalyze substrate to its fluorescent product were considered ALDH+. Sorting gates for FACS were drawn relative to cell baseline fluorescence, which was determined by the addition of the ALDH-specific inhibitor DEAB during the incubation and DEAB-treated samples as negative controls. Nonviable cells were identified by 7-aminoactinomycin D inclusion. Flow cytometry analyses were performed on FACScan or FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

For comparisons between two groups, Student t test was used, and for analysis with multiple comparisons, analyses of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used, using PRISM software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Chi-square analysis was used for categorical outcomes. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and the exact tests used for each experiment were listed in the text and in the figure legend. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Phosphorylation of JNK and c-JUN is regulated by EPHA2 in lung cancer cells

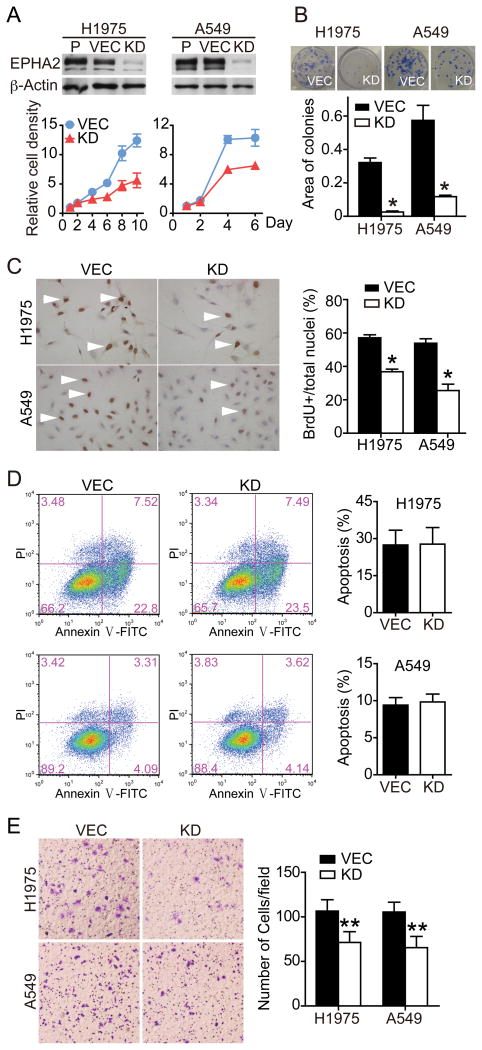

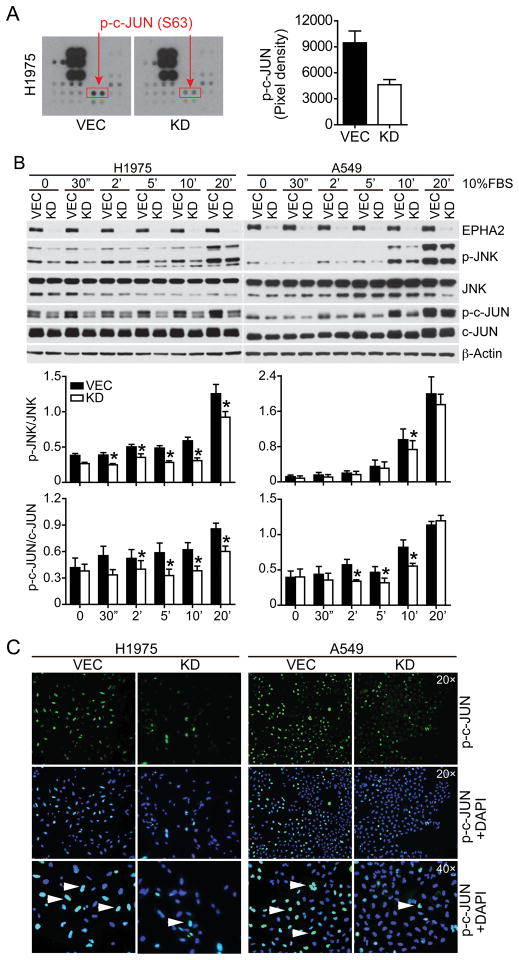

Previous studies showed that knockdown of EPHA2 receptor in cultured lung cancer cells inhibited proliferation (11). Conversely, expression of EPHA2 in immortalized BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells increased cell survival and invasion (10). Consistent with these observations, shRNA-mediated stable knockdown of EPHA2 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) lines inhibited tumor cell proliferation and motility (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). To identify signaling pathways downstream of EPHA2 receptor that mediate tumor-promoting effects in cancer cells, cell lysates derived from vector-control or EPHA2 shRNA knockdown H1975 cells were used to screen two human phospho-kinase antibody arrays (human phospho-kinase antibody array and human phospho-RTK antibody array). As shown in Figure 2A, phosphorylation at Ser63 residue of c-JUN is decreased in EPHA2 knockdown cells, relative to vector control cells, in two independent experiments, suggesting that EPHA2 may regulate the JNK/c-JUN pathway in lung cancer cells.

Figure 1. Depletion of EPHA2 by shRNA inhibits tumor cell growth and motility.

H1975 and A549 cells were transduced with lentiviruses carrying control vector or shRNAs against EPHA2. EPHA2 protein depletion by shRNA-mediated stable knockdown was confirmed by western blot analysis (A). Cell viability, clonal growth, proliferation and apoptosis were measured by MTT (A), colony formation (B), BrdU incorporation (C), and Annexin V stain (D), respectively. Cell migration in response to serum stimulation for 6 hours was assessed by the transwell migration assay (E). Data were pooled from 2–3 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SEM. P, Parental control; VEC, vector; KD, knockdown. *p<0.05, **P<0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Figure 2. Regulation of JNK and c-JUN activity by the EPHA2 receptor.

(A) EPHA2 was knocked down in H1975 cells and cell lysates were used to probe duplicates of phospho-kinase antibody arrays, one of which is shown. Arrow indicates the location of p-c-JUN on the blot. Pixel density of p-c-JUN was quantified for each blot and the average value is shown in the bar graph. VEC, vector control; KD, EPHA2 shRNA knockdown. (B) H1975 or A549 cells were serum starved overnight and p-c-JUN and pJNK levels were measured by western blot analysis in response to 10% FBS following a time course. Shown are immunoblots representative of 4 independent experiments. Densitometry analyses for 4 independent blots are summarized in the bar graph. *p<0.05, (two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Immunofluorescence of phospho-c-JUN in vector control or EphA2 knockdown H1975 or A549 cells. Nuclear staining of p-c-JUN (green, arrowhead) is confirmed by co-staining with DAPI (blue).

To determine if depletion of EphA2 affects JNK/c-JUN signaling in response to serum stimulation, H1975 or A549 cells were serum starved overnight and stimulated with 10% FBS following a time course, and phosphorylated levels of JNK and c-JUN were determined by western blot analysis. We found that p-JNK/JNK and p-c-JUN/c-JUN levels were consistently decreased in EPHA2 knockdown cells in four independent experiments (Figure 2B). Interestingly, we also found that total c-JUN levels appear to be decreased in EPHA2 deficient cells. Next, we sought to investigate whether phosphorylation of c-JUN and JNK are altered in other EPHA2-depleted NSCLC cells. Consistent with observations in H1975 and A549 cells, knockdown of EphA2 resulted in decrease of p-c-JUN and pJNK levels in 4 and 5 out of 10 NSCLC lines tested, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Once phosphorylated, c-JUN enters the nucleus and regulates transcription (14, 15). Accordingly, we assessed nuclear c-JUN expression by immunofluorescence. The number of cells expressing nuclear c-JUN is markedly decreased in EPHA2 knockdown cells relative to vector control cells (Figure 2C), indicating that EPHA2 regulates c-JUN activity. Collectively, pJNK and p-c-JUN levels were reproducibly and significantly decreased in approximately 50% of EPHA2 knockdown cell lines tested, whereas phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK were not changed in most cell lines (Supplementary Figure 2).

JNK signaling mediates EPHA2-dependent tumor cell proliferation and motility

JNK was originally shown to mediate cell apoptosis in response to a variety of stress signals (14, 15). However, emerging evidence suggests that JNKs play a critical role in cell growth and survival in tumor cells (14–17). Indeed, JNK is activated in NSCLC and promotes neoplastic transformation in human bronchial epithelial cells (18). JNK2-α appears to be the major JNK isoform that plays a critical role in lung cancer (19). Therefore, the JNK/c-JUN pathway may, at least in part, mediate EPHA2-dependent regulation of tumor cell behavior. To investigate whether JNK/c-JUN pathway is necessary and sufficient for cell proliferation and motility, we used two complementary approaches: a JNK kinase inhibitor, SP600125, and two constitutively activated JNK mutants (JNK1-CA and JNK2-CA).

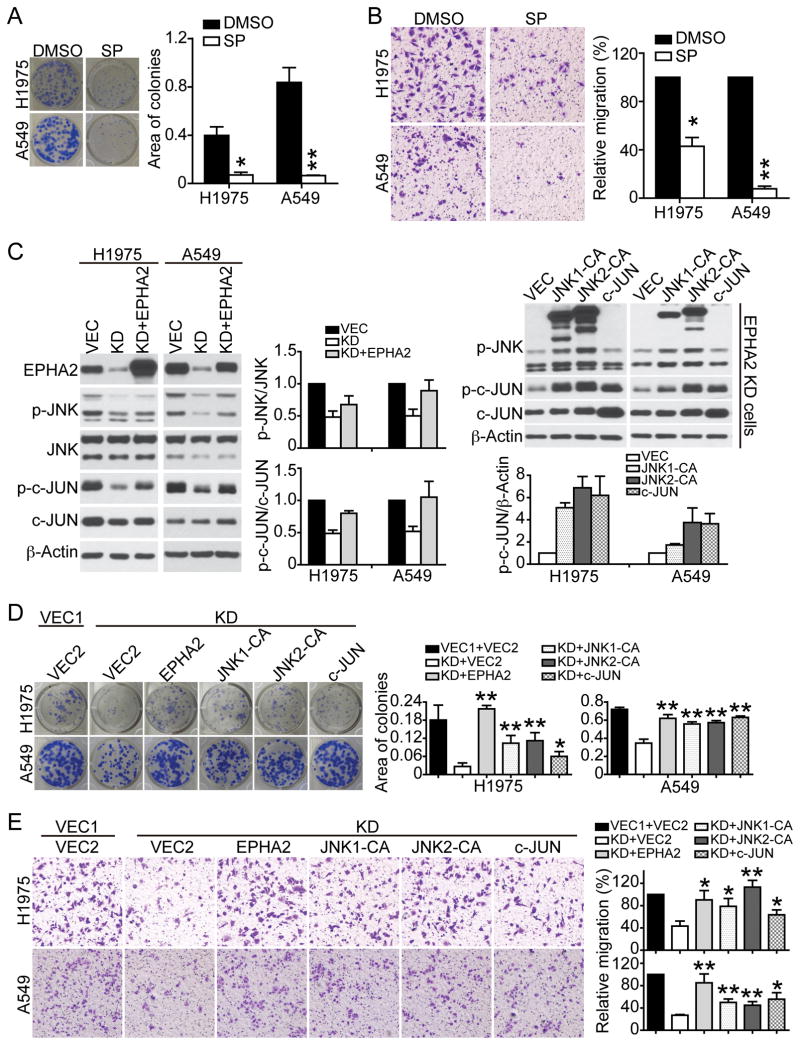

Treatment of either A549 or H1975 cells with JNK inhibitor SP600125 inhibited p-JNK and p–c-JUN levels (Supplementary Figure 3A) and reduced cell viability, colony formation and tumor cell motility in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A & 3B, Supplementary Figure 3B), suggesting that the JNK/c-JUN pathway is required in lung cancer cells. To investigate whether the JNK/c-JUN pathway mediates EPHA2 receptor signaling, we utilized previously characterized constitutively activated MKK7-JNK1 and MKK7-JNK2 fusion mutants [here after termed JNK-CA, (20)]. Re-expression of wild-type EPHA2 receptor in EPHA2-knockdown cells rescued p-JNK and p-c-JUN levels, colony formation, and cell motility (Figure 3C–E), demonstrating that phenotypes in EPHA2 knockdown cells are not due to off-target effects. Expression of JNK1-CA, JNK2-CA, or c-JUN rescued phenotypes in the EPHA2 knockdown cells to the comparable level as wild-type EPHA2 (Figure 3C–E), indicating that activated JNK1/2 or overexpression of c-JUN is sufficient to restore function in these cells. Collectively, these data suggest that JNK/c-JUN pathway mediates EPHA2-dependent tumor cell proliferation and motility.

Figure 3. JNK/c-JUN signaling mediates EphA2-dependent tumor cell growth and motility.

(A&B) A549 or H1975 cells were treated with DMSO or 10 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 for 24 hours. Cell growth (A) and motility (B) in response to 10% serum in the presence of DMSO or SP600125 were assessed by colony formation assay and transwell migration assay, respectively. Shown are images from one experiment that are representative of three independent experiments. Data were pooled and presented as mean ± SEM. (C) EPHA2 knockdown A549 or H1975 cells were transduced with retroviruses expressing wildtype EPHA2, constitutively activated JNK1-CA, JNK2-CA, wildtype c-JUN, or vector control. Expression of JNK1-CA, JNK2-CA, or c-JUN, as well as phosphorylation of JNK and c-JUN was analyzed by western blot analysis. Densitometry analyses for 3 independent experiments for each condition are summarized in the bar graph. (D&E) The effects of JNK1-CA or JNK2-CA on clonogenic cell growth (D) and motility (E) were determined by colony formation assay and transwell migration assay, respectively. Shown are images from one experiment that are representative of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

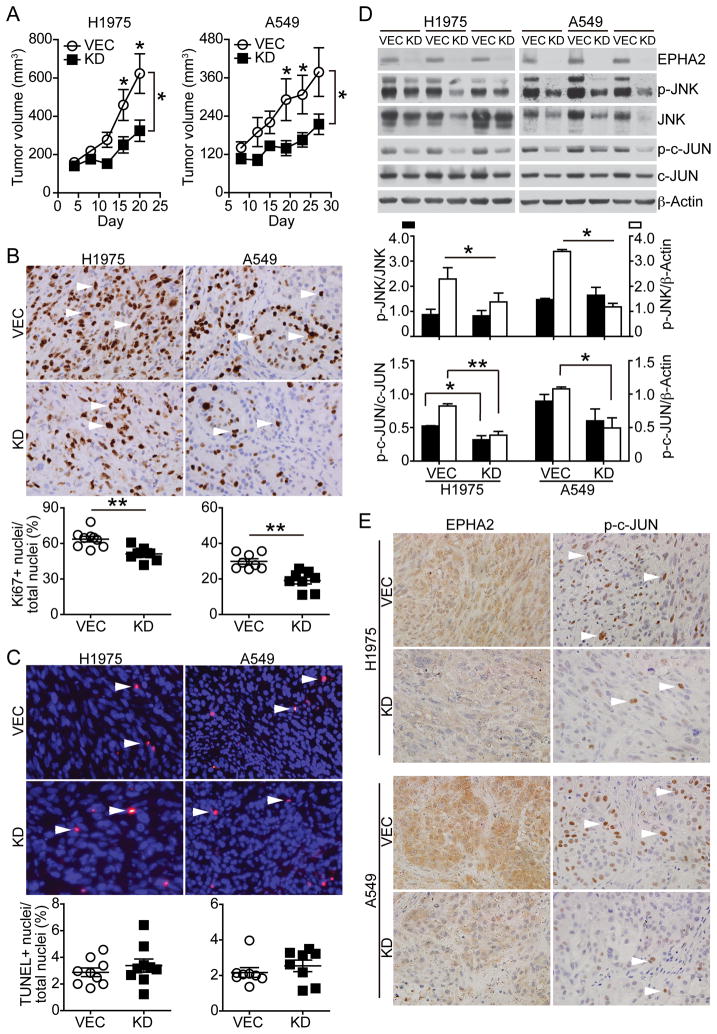

Loss of EPHA2 inhibits JNK/c-JUN signaling and suppresses tumor formation and tumor growth in vivo

To directly determine the in vivo role of EPHA2 in lung cancer, EPHA2 knockdown A549 or H1975 cells were injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flank of a nude mouse, and control cells carrying the empty vector were injected contralaterally in the same mouse. Loss of EPHA2 in knockdown tumors significantly inhibited tumor volume in the xenograft animal models (mean A549 tumor volume: vector control 419 ± 236 mm3 versus EPHA2 shRNA 225 ± 90 mm3; mean H1975 tumor volume: vector control 623 ± 310 mm3 versus EPHA2 shRNA 324 ± 166 mm3, p<0.05, paired t test) (Figure 4A). Tumors were harvested at the end of the studies and tumor sections were subjected to Ki67 immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay for assessing proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. Consistent with in vitro data, we found that tumor cell proliferation was decreased in EPHA2 knockdown tumors as compared to vector control tumors, whereas apoptosis levels were not significantly changed between the two groups (Figure 4B & 4C). Analysis of tumor lysates revealed that EPHA2 was stably knocked down in tumors after grown in vivo for 30 days. Both phosphorylation and total levels of c-JUN were decreased in EphA2-deficient H1975 tumors, whereas there was a predominant reduction in total JNK and c-JUN levels in both EPHA2-deficient H1975 and A549 tumors (Figure 4D). Expression of EPHA2 and p-c-JUN was further analyzed in adjacent tumor sections by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 4E, EPHA2 receptor and p-c-JUN were co-expressed in the control tumors, whereas nuclear staining of p-c-JUN is markedly decreased in EPHA2 knockdown tumors. Taken together, these results show that EPHA2 promotes tumor growth of NSCLC, such that depletion of EPHA2 limited progression of this aggressive NSCLC xenografts model.

Figure 4. EPHA2-deficiency inhibits tumor growth in vivo.

(A) Two and half million of EPHA2 knockdown A549 or H1975 cells were injected into nude mice subcutaneously. Control cells carrying empty vector were injected contralaterally in the same mouse (n=9 per group). Tumor size was measured by a digital caliper and tumor volume calculated. The observed reduction in tumor volume in EPHA2 knockdown tumors was statistically significant for both A549 and H1975 tumors (two-tailed Student’s t test, *p<0.05). (B&C) Tumors were collected 25–30 days after injection. Tumor sections were subjected to Ki67 immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay to detect proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. Ki67 positive nuclei (brown, arrowhead) or TUNEL positive nuclei (red, arrowhead) were quantified and proliferation or apoptosis index was calculated as Ki67+ nuclei/ total nuclei or TUNEL+ nuclei/total nuclei. **p<0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t test). (D&E) Expression of EPHA2, phosphorylated and total levels of JNK and c-JUN in tumor lysates was determined by western blot analyses (D) and immunohistochemistry (E). Immunoblots of three EPHA2 knockdown or vector control tumors were shown (D). Densitometry analyses for blots are shown in the bar graph. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

To further investigate whether loss of EPHA2 affects lung cancer formation in vivo, we knocked down EPHA2 in A549 and H1975 cells that express luciferase. EPHA2 depletion in these knockdown cells was confirmed by FACS and western blot analysis (Supplementary Figure 4). Serial diluted EPHA2 knockdown tumor cells (2.5×105, 2.5×104, 2.5×103) were injected subcutaneously into nude mice, and same numbers of control cells carrying the empty vector were injected contralaterally in the same mouse. Tumor formation was monitored by bioluminescence weekly. Vector control A549 and H1975 cells exhibited a greater frequency of tumor formation, particularly at low numbers of injected cells, compared with EPHA2 knockdown counterparts (Supplementary Figure 4). Collectively, our tumor xenograft data suggest that EPHA2 receptor regulates both tumor formation and tumor growth in vivo.

EPHA2 silencing suppresses ALDH positive stem-like cell-enriched populations, tumor sphere formation, and tumorigenicity in vivo

Recent evidence suggests that human lung cancers harbor cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) or tumor initiating/ propagating cells (TICs/TPCs) that facilitate tumor cell heterogeneity, metastases, and therapeutic resistance (21, 22). Because CSCs/TICs/TPCs are intimately linked with tumor initiation and knockdown of EPHA2 affects tumor formation in vivo, we tested if EPHA2-deficiency affects CSC/TIC/TPC populations in lung cancer cells.

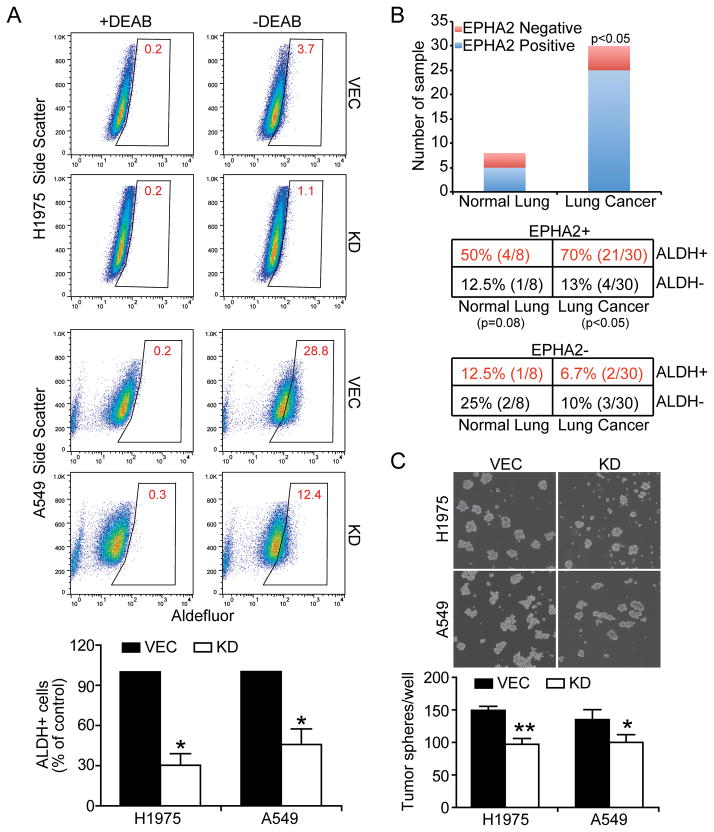

ALDH has recently been identified as a marker for lung cancer cells with stem cell-like properties, and ALDH+ cells were shown to be highly tumorigenic compared to ALDH-counterparts (23, 24). Accordingly we used the Aldefluor assay to quantify the percentage of ALDH+ cells in vector control and EPHA2 knockdown lung cancer cell lines. Cells were incubated in Aldefluor assay buffer containing efflux inhibitor and the ALDH substrate. Cells that could catalyze substrate to its fluorescent product were considered ALDH positive. Sorting gates for FACS were drawn relative to cell baseline fluorescence, which was determined by the addition of the ALDH-specific inhibitor DEAB during the incubation and DEAB-treated samples serve as negative controls. As shown in Figure 5A, a subpopulation of ALDH+ cells was detected by flow cytometry in control A549 and H1975 cells, and the ALDH+ subpopulations significantly decreased in corresponding EPHA2 knockdown cells. Depletion of EphA2 also reduced ALDH+ populations in H23 and H1650 cells (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 5. The effects of EPHA2 receptor on ALDH-positive cancer stem-like populations and tumor sphere formation.

(A) Control or EPHA2 knockdown H1975 or A549 cells were incubated in Aldefluor assay buffer containing efflux inhibitor and the ALDH substrate. Cells that could catalyze substrate to its fluorescent product were considered ALDH+. Sorting gates for FACS were drawn relative to cell baseline fluorescence, which was determined by the addition of the ALDH-specific inhibitor DEAB during the incubation and DEAB-treated samples as negative controls. Nonviable cells were identified by 7-AAD inclusion. Data were pooled from 3 independent experiments and ALDH+ populations in EPHA2 knockdown cells were presented as % of vector control cells. *p<0.05. (B) EPHA2 and ALDH expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry in adjacent sections of a tissue microarray containing tissues from 30 lung cancer micro-samples and 8 normal control lung samples. The aggregate numbers of anti- EPHA2 positive (blue) and negative (red) samples in normal and cancer samples were summarized in the graph. The numbers of anti-ALDH or anti- EPHA2 positive and negative samples in normal and tumor samples were presented in the table and the association of EPHA2 and ALDH expression was tested statistically (Chi square test, p<0.05 in lung cancer samples). (C) A549 (5,000/well) and H1975 (10,000/well) single cell suspension were plated in 6-well dish in serum-free spherical culture medium for 7 and 10 days, respectively, and photographed. Plates were scanned and numbers of tumor sphere per well were enumerated automatically using The GelCountTM system. Images from one experiment representative of 3 independent experiments are shown. *p< 0.05, **p<0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

To relate the findings to human lung cancer, we analyzed the expression of EPHA2 and ALDH on adjacent sections of human lung cancer tissue microarrays. Consistent with previous studies, we observed significantly elevated EPHA2 protein expression in human lung tumor samples relative to normal, adjacent control lung tissue (5/8 EPHA2+ normal lung tissue samples versus 25/30 EPHA2+ lung cancer tissue samples; p<0.05, Chi Square analysis). Furthermore, we observed a positive correlation between EPHA2 expression and ALDH expression in a significant number of human lung cancer samples (21/30, 70%) relative to samples that were EPHA2 positive but ALDH negative (4/30, 13%) (p<0.05, Chi Square analysis)(Figure 5B). Together, these data demonstrate the relevance of our studies in human cancer.

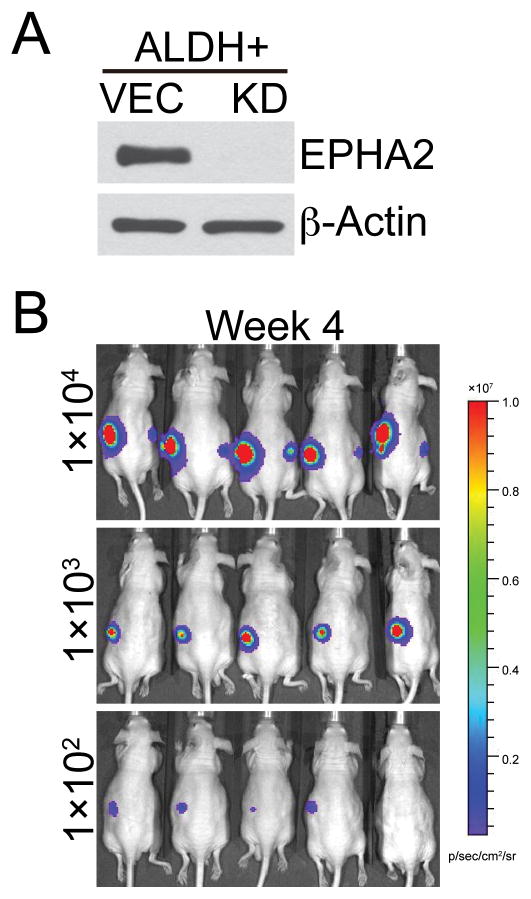

In addition to expressing stem cell markers, CSCs/TICs/TPCs are capable of propagation of isolated tumor cells as spheroids in suspension, and exhibit a high capacity for tumorigenic growth in mouse xenografts. We found that knockdown of EPHA2 significantly suppressed sphere-forming ability and in vitro self-renewal capacity of A549 and H1975 cells (Figure 5C). To test the role of EPHA2 in tumorigenic capacity of cancer stem-like cells, ALDH positive populations were sorted from A549 cells by FACS (Supplementary Figure 6) and subsequently transduced with either control virus or lentiviral shRNA against EPHA2 (Figure 6A). Serial dilutions of control or EPHA2 knockdown ALDH-positive cells (104, 103, 102 cells) were then injected into nude mice and tumor development was monitored weekly by bioluminescence imaging (Figure 6B). Compared to unsorted populations, control ALDH+ cells develop tumors much sooner (7 weeks in unsorted cells versus 3 weeks in ALDH+ cells), suggesting that CSCs/TICs/ TPCs are enriched in ALDH+ populations. Furthermore, while 100% of mice injected with 1000 ALDH+ vector control cells formed tumors at week 4, none of the mice injected with 1000 ALDH+ EPHA2 knockdown cells developed tumor. When 100 ALDH+ cells were injected, 80% of mice carrying vector control cells formed tumors at week 4, compared to 0% of mice carrying EPHA2 knockdown cells (Table 1). Collectively, our data on stem cell marker analysis, spheroid formation assay, and in vivo tumorigenicity suggest a role for EPHA2 in regulating cancer stem-like populations.

Figure 6. Loss of EPHA2 inhibits tumorigenic capacity of cancer stem-like enriched populations in vivo.

(A) ALDH positive populations in luciferase-expressing A549 cells were isolated by FACS sorting. EPHA2 expression was subsequently silenced by lentiviral shRNA transduction as determined by western blot analysis. (B) Limiting dilutions of vector control or EPHA2 knockdown stem-like cell enriched populations were injected into the left and right flanks of nude mice, respectively. Tumor formation was monitored weekly by palpation and luminescence imaging. Shown are bioluminescence images of mice at 4 weeks post injection (B). Tumor incidence was presented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Tumor incidence in ALDH+ populations.

| shRNA | Cell number | Tumor incidence |

|---|---|---|

| VEC | 1 × 104 | 5/5 (100%) |

| 1 × 103 | 5/5 (100%) | |

| 1 × 102 | 4/5 (80%) | |

|

| ||

| KD | 1 × 104 | 5/5 (100%) |

| 1 × 103 | 0/5 (0%) | |

| 1 × 102 | 0/5 (0%) | |

ALDH positive populations in A549 cells were isolated by FACS. Limiting dilutions of vector control (VEC) or EPHA2 knockdown (KD) stem-like cell enriched populations were injected into nude mice and tumor formation was monitored by luminescence imaging four weeks post transplantation.

Discussion

Recent efforts in analyzing cancer genome have identified EPHA2 as one of the genes that are elevated in human lung cancer, and high levels of EPHA2 are associated with poor clinical outcomes. However, mechanistic basis for EPHA2 in lung cancer promotion remains poorly understood. In this study, we found that EphA2 regulates tumor cell proliferation and motility through the JNK-c-JUN pathway. In addition, we provide evidence that EPHA2 is important for cancer stem-like cell function. Collectively, these data identified JNK/c-JUN as a major signaling pathway that is activated by oncogenic EPHA2 receptor in non-small cell lung cancer, and a critical role for EPHA2 in cancer stem-like cells.

Multiple intracellular signaling pathways have been linked to EPHA2 receptor in cancer cells [reviewed in (2, 25)]. Ligand stimulation of EPHA2 has been shown to inhibit ERK and AKT phosphorylation, and tumor cell proliferation and motility in prostate and lung cancer cells, as well as in malignant glioma cells (11, 26, 27). Conversely, ligand-independent EPHA2 signaling and cross-talk with ERBB family receptors is linked to tumor cell proliferation and motility and up-regulation of pERK and RHO-GTP levels (6, 7, 26) in breast cancer and malignant glioma cells. In lung cancer, although ephrins are expressed, the tumor promotion role of EPHA2 appears to be ligand-independent, as we were unable to detect significant levels of EPHA2 receptor phosphorylation without exogenous EPHRIN-A1 stimulation, and ligand stimulation induced opposing phenotypes from EPHA2 receptor overexpression (11). It is currently unclear why ERK and AKT activities do not appear to be consistently affected by EPHA2 knockdown in NSCLC lines tested. Because of high mutation rates in lung cancer, it is possible that there are unidentified mutations in genes that act downstream of EPHA2 and affect ERK/AKT activities in these cell lines. Regardless of mechanisms, our data suggest that ERK/AKT are not direct targets of ligand-independent EPHA2 signaling in majority of the lung cancer cells.

JNK was originally shown to mediate cell apoptosis in response to a variety of stress signals (14, 15). However, emerging evidence suggests that JNKs play a critical role in cell growth and survival in tumor cells (16, 17)[reviewed in (14, 15)]. For example, JNK activity is up-regulated in colorectal cancer. Activation of JNK increases cell proliferation, probably through regulation of mTORC1 signaling via phosphorylation of Raptor, as well as modulation of transcription of cyclin E via activation of c-JUN (28). In lung cancer, JNK is phosphorylated at Thr183/Tyr185 in NSCLC biopsy samples, and promotes tumor cell proliferation and motility (18, 19). However, it is not known what signal activates JNK in the lung cancer cells thus far. Here we provide evidence that JNK activity in lung cancer cells is regulated by EPHA2 receptor. First, knockdown of EPHA2 significantly inhibited phosphorylation levels of both JNK and c-JUN in multiple lung cancer cell lines (Figure 2). Furthermore, treatment of JNK inhibitor recapitulates phenotypes in EPHA2 knockdown cells, whereas overexpression of a constitutively activated JNK-CA rescued defects in EPHA2-deficient lung cancer cells (Figure 3). Together, these data identified JNK/c-JUN as a previously unknown target of EPHA2 receptor signaling in cancer.

How EPHA2 regulates the JNK/c-JUN signaling pathway remains to be determined. JNK activity was reported to be regulated by RHO family small GTPases (29, 30). We and others have previously shown that EPHA2 regulates RHO activity in breast cancer and prostate cancer cells (7, 31–33), suggesting the possibility of RHO GTPases as candidates to link EPHA2 to JNK/c-JUN. In addition to regulation of JNK/c-JUN activities, EPHA2 also affects JNK/c-JUN protein levels. We found that depletion of EPHA2 leads to decreased total levels of JNK and c-JUN in some cell lines and tumor xenografts (Figures 2 and 4, and Supplementary Figure 2), whereas mRNA levels of JNK1, JNK2, or c-JUN are not significantly changed (Supplementary Figure 2). In the case of c-JUN, phosphorylation by JNK at Ser63 and Ser73 is known to increase its activity and protect c-JUN from ubiquitination and subsequent degradation (34). Thus it is possible that decreased c-JUN phosphorylation in EPHA2 knockdown cells leads to reduced c-JUN protein stability. In addition, EPHA receptors are known to regulate mTORC1 activity in the nervous system and cancer cells (35, 36), and overexpression of EPHA2 in immortalized lung epithelial cells BES2B increased phosphorylation of mTOR and S6K1 (10). Indeed, we also observed a decrease of pS6 in several EPHA2 knockdown NSCLC lines (Supplementary Figure 2). Because one of the major functions of mTORC1 is cap-dependent protein synthesis (37), it is also possible that EPHA2 regulates the protein synthesis of JNK and/or c-JUN through activation of mTOR complex 1.

Although our studies suggest that JNK signaling mediates EPHA2-dependent tumor cell proliferation and motility in lung cancer, it cannot be excluded that other signaling pathways may also play a role downstream of EPHA2 receptor in subsets of lung cancer. Thus far, JNK/c-JUN activities are affected in 5 out of 10 cell lines tested (Supplementary Figure 2). Other signaling pathways known to act downstream of EPHA2 receptor, such as the mTOR pathway, RHO family GTPases, STAT 3 transcription factor, and FAK kinase, will be alternative avenues to pursue in subsets of lung cancer cells that JNK activities are not altered upon EPHA2 knockdown.

EPHA2 receptor has been implicated in stem cell biology previously. EPHA2 is highly expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells (38, 39) and its expression is regulated by E-cadherin in ES cells (39). More recently, EPHA2 is also shown to drive self-renewal and tumorigenicity in human glioblastoma stem-like cells (40). Studies presented in this report demonstrated a critical role of EPHA2 in lung cancer stem-like cells. EPHA2 expression is correlated with cancer stem cell marker ALDH expression (23, 24) in human lung cancer tissue microarray (Figure 5B). Knockdown of EPHA2 in lung cancer cells significantly reduced ALDH+ populations and the ability to form spheroids in suspension (Figure 5A and 5C). Furthermore, RNAi-mediated depletion of EPHA2 in stem-like cell enriched sorted population inhibited tumorigenicity in vivo (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 6), suggesting an important role of EPHA2 in lung cancer stem-like cell function.

The identification of JNK/c-JUN pathway as a downstream target of EPHA2 receptor in NSCLCs, as well as the role of EPHA2 in cancer stem-like cells, opens up exciting opportunities for potential molecularly targeted therapies in lung cancer. Although early versions of JNK inhibitors displayed poor kinase selectivity and low efficacy, a new generation of more potent and selective irreversible JNK inhibitors has been identified (41) and may be developed for molecularly targeted therapy in NSCLC. In addition, a variety of strategies have been developed to target EPHA2, including activating monoclonal antibody, ephrin ligands, ligand-mimic peptides against EPHA2, and selective kinase inhibitors [reviewed in (42, 43)]. As cancer stem-like cells are often resistant to therapies and the fact that cancer stem-like cells depend on EPHA2 for self-renewal in lung cancer, targeting EPHA2 may hold promise for treatment of drug-resistant lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs through a VA Merit Award (J. Chen), NIH RO1 grants CA95004 (J. Chen) and CA148934 (D. Brantley-Sieders), and a pilot project grant from the VICC Lung SPORE program P50CA090949 (J. Chen). This work was also supported in part by the resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # P30 CA068485 utilizing the Translational Pathology, Flow Cytometry, and Small Animal Imaging Shared Resources.

Footnotes

Disclosure of any potential Conflict of Interest: none.

References

- 1.Brantley-Sieders DM. Clinical relevance of Ephs and ephrins in cancer: Lessons from breast, colorectal, and lung cancer profiling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.014. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquale EB. Eph receptors and ephrins in cancer: bidirectional signaling and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:165–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:475. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquale EB. Developmental Cell Biology: Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–75. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen AB, Pedersen MW, Stockhausen MT, Grandal MV, van Deurs B, Poulsen HS. Activation of the EGFR gene target EphA2 inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced cancer cell motility. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:283–93. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brantley-Sieders DM, Zhuang G, Hicks D, Fang WB, Hwang Y, Cates JM, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 promotes mammary adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis and metastatic progression in mice by amplifying ErbB2 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:64–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI33154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinch MS, Moore MB, Harpole DHJ. Predictive value of the EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase in lung cancer recurrence and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:613–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brannan JM, Dong W, Prudkin L, Behrens C, Lotan R, Bekele BN, et al. Expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 is increased in smokers and predicts poor survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4423–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faoro L, Singleton PA, Cervantes GM, Lennon FE, Choong NW, Kanteti R, et al. EphA2 mutation in lung squamous cell carcinoma promotes increased cell survival, cell invasion, focal adhesions, and mTOR activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18575–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brannan JM, Sen B, Saigal B, Prudkin L, Behrens C, Solis L, et al. EphA2 in the early pathogenesis and progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:1039–49. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brantley DM, Cheng N, Thompson EJ, Lin Q, Brekken RA, Thorpe PE, et al. Soluble EphA receptors inhibit tumor angiogenesis and progression in vivo. Oncogene. 2002;21:7011–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brantley-Sieders DM, Jiang A, Sarma K, Badu-Nkansah A, Walter DL, Shyr Y, et al. Eph/ephrin profiling in human breast cancer reveals significant associations between expression level and clinical outcome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weston CR, Davis RJ. The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opi Cell Biol. 2007;19:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen F. JNK-induced apoptosis, compensatory growth, and cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:379–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess P, Pihan G, Sawyers CL, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Survival signaling mediated by c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase in transformed B lymphoblasts. Nat Genet. 2002;32:201–5. doi: 10.1038/ng946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durbin AD, Somers GR, Forrester M, Pienkowska M, Hannigan GE, Malkin D. JNK1 determines the oncogenic or tumor-suppressive activity of the integrin-linked kinase in human rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1558–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI37958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatlani TS, Wislez M, Sun M, Srinivas H, Iwanaga K, Ma L, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is activated in non-small-cell lung cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:2658–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nitta RT, Del Vecchio CA, Chu AH, Mitra SS, Godwin AK, Wong AJ. The role of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2-α-isoform in non-small cell lung carcinoma tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2011;30:234–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei K, Nimnual A, Zong WX, Kennedy NJ, Flavell RA, Thompson CB, et al. The Bax subfamily of Bcl2-related proteins is essential for apoptotic signal transduction by c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4929–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4929-4942.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen LV, Vanner R, Dirks P, Eaves CJ. Cancer stem cells: an evolving concept. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:133–43. doi: 10.1038/nrc3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan JP, Spinola M, Dodge M, Raso MG, Behrens C, Gao B, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity selects for lung adenocarcinoma stem cells dependent on notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9937–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, Todd NW, Deepak J, Xing L, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:330–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J. Regulation of tumor initiation and metastatic progression by Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Adv Cancer Res. 2012;114:1–20. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386503-8.00001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miao H, Li DQ, Mukherjee A, Guo H, Petty A, Cutter J, et al. EphA2 mediates ligand-dependent inhibition and ligand-independent promotion of cell migration and invasion via a reciprocal regulatory loop with Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao H, Wei B-R, Peehl DM, Li Q, Alexandrou T, Schelling JR, et al. Activation of EphA receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits the Ras/MAPK pathway. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;13:527–30. doi: 10.1038/35074604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujishita T, Aoki M, Taketo MM. JNK signaling promotes intestinal tumorigenesis through activation of mTOR complex 1 in Apc(Δ716) mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1556–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marinissen MJ, Chiariello M, Tanos T, Bernard O, Narumiya S, Gutkind JS. The small GTP-binding protein RhoA regulates c-jun by a ROCK-JNK signaling axis. Mol Cell. 2004;14:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coso OA, Chiariello M, Yu JC, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, et al. The small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81:1137–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaught D, Chen J, Brantley-Sieders DM. Regulation of mammary gland branching morphogenesis by EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2572–81. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang WB, Ireton RC, Zhuang G, Takahashi T, Reynolds A, Chen J. Overexpression of EPHA2 receptor destabilizes adherens junctions via a RhoA-dependent mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:358–68. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parri M, Taddei ML, Bianchini F, Calorini L, Chiarugi P. EphA2 reexpression prompts invasion of melanoma cells shifting from mesenchymal to amoeboid-like motility style. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2072–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs SY, Dolan L, Davis RJ, Ronai Z. Phosphorylation-dependent targeting of c-Jun ubiquitination by Jun N-kinase. Oncogene. 1996;13:1531–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nie D, Di Nardo A, Han JM, Baharanyi H, Kramvis I, Huynh T, et al. Tsc2-Rheb signaling regulates EphA-mediated axon guidance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:163–72. doi: 10.1038/nn.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang NY, Fernandez C, Richter M, Xiao Z, Valencia F, Tice DA, et al. Crosstalk of the EphA2 receptor with a serine/threonine phosphatase suppresses the Akt-mTORC1 pathway in cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2011;23:201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Nachebeh A, Scherer C, Ganju P, Reith A, Bronson R, et al. Germline inactivation of the murine Eck receptor tyrosine kinase by retroviral insertion. Oncogene. 1996;12:979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orsulic S, Kemler R. Expression of Eph receptors and ephrins is differentially regulated by E-cadherin. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 (Pt 10):1793–802. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binda E, Visioli A, Giani F, Lamorte G, Copetti M, Pitter KL, et al. The EphA2 receptor drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity in stem-like tumor-propagating cells from human glioblastomas. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:765–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang T, Inesta-Vaquera F, Niepel M, Zhang J, Ficarro SB, Machleidt T, et al. Discovery of potent and selective covalent inhibitors of JNK. Chemistry & biology. 2012;19:140–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wykosky J, Debinski W. The EphA2 receptor and ephrinA1 ligand in solid tumors: function and therapeutic targeting. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1795–806. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noberini R, Lamberto I, Pasquale EB. Targeting Eph receptors with peptides and small molecules: progress and challenges. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2012;23:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.