Abstract

Tolerance of plants to abiotic stressors such as drought and salinity is triggered by complex multicomponent signaling pathways to restore cellular homeostasis and promote survival. Major plant transcription factor families such as bZIP, NAC, AP2/ERF, and MYB orchestrate regulatory networks underlying abiotic stress tolerance. Sucrose non-fermenting 1-related protein kinase 2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways contribute to initiation of stress adaptive downstream responses and promote plant growth and development. As a convergent point of multiple abiotic cues, cellular effects of environmental stresses are not only imbalances of ionic and osmotic homeostasis but also impaired photosynthesis, cellular energy depletion, and redox imbalances. Recent evidence of regulatory systems that link sensing and signaling of environmental conditions and the intracellular redox status have shed light on interfaces of stress and energy signaling. ROS (reactive oxygen species) cause severe cellular damage by peroxidation and de-esterification of membrane-lipids, however, current models also define a pivotal signaling function of ROS in triggering tolerance against stress. Recent research advances suggest and support a regulatory role of ROS in the cross talks of stress triggered hormonal signaling such as the abscisic acid pathway and endogenously induced redox and metabolite signals. Here, we discuss and review the versatile molecular convergence in the abiotic stress responsive signaling networks in the context of ROS and lipid-derived signals and the specific role of stomatal signaling.

Keywords: transcription factor, Arabidopsis; lipid signaling; ROS; drought; MAP kinase

INTRODUCTION

Survival of plants under adverse environmental conditions relies on integration of stress adaptive metabolic and structural changes into endogenous developmental programs. Abiotic environmental factors such as drought and salinity are significant plant stressors with major impact on plant development and productivity thus causing serious agricultural yield losses (Flowers, 2004; Godfray et al., 2010; Tester and Langridge, 2010; Agarwal et al., 2013). The complex regulatory processes of plant drought and salt adaptation involve control of water flux and cellular osmotic adjustment via biosynthesis of osmoprotectants (Hasegawa et al., 2000; Flowers, 2004; Munns, 2005; Ashraf and Akram, 2009; Agarwal et al., 2013). Salinity induced imbalance of cellular ion homeostasis is coped with regulated ion influx and efflux at the plasma membrane and vacuolar ion sequestration (Hasegawa et al., 2000). Significantly, drought and salinity have additionally major detrimental impacts on the cellular energy supply and redox homeostasis that are balanced by global re-programming of plant primary metabolism and altered cellular architecture (Chen et al., 2005; Baena-González et al., 2007; Jaspers and Kangasjärvi, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010). In this review we focus on recent advances in understanding cellular signaling networks of biotechnological relevance in plant drought and salt adaptation. Here, we focus on induced rather than intrinsic tolerance mechanisms and do not explicitly distinguish between stress survival and tolerance. Known research findings on hormonal signal perception and transduction were integrated in the context of plant signaling networks under drought and salinity. We particularly aimed on reviewing links of drought and salt induced signal transduction to plant hormonal pathways, metabolism, energy supply and developmental processes.

PLANT HORMONES: PIVOTAL ROLES IN PLANT STRESS SIGNALING

Plant hormones function as central integrators that link and re-program the complex developmental and stress adaptive signaling cascades. The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) functions as a key regulator in the activation of plant cellular adaptation to drought and salinity and has a pivotal function as a growth inhibitor (Cutler et al., 2010; Raghavendra et al., 2010; Weiner et al., 2010). Additionally, the view of function of ABA as a linking hub of environmental adaptation and primary metabolism is increasingly emerging. Intriguingly, ABA triggers both transcriptional reprogramming of cellular mechanisms of abiotic stress adaptation and transcriptional changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism indicating function of ABA at the interface of plant stress response and cellular primary metabolism (Seki et al., 2002; Li et al., 2006; Hey et al., 2010).

Abscisic acid signals are perceived by different cellular receptors and a concept of activation of specific cellular ABA responses by perception in the distinct cellular compartments is currently emerging. The nucleocytoplasmic receptors PYR/PYL/RCARs (PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE/ PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE-LIKE/REGULATORY COMPONENT OF ABA RECEPTORS) bind ABA and inhibit type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs) such as ABI1 and ABI2 (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). Inactivation of PP2Cs activates accumulation of active SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASES (SnRK2s; Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Umezawa et al., 2009; Vlad et al., 2009). The SnRK2s regulate ABA-responsive transcription factors including AREB/ABFs [ABA-RESPONSIVE PROMOTER ELEMENTS (ABREs) BINDING FACTORS (ABFs)] and activate ABA-responsive genes and ABA-responsive physiological processes (Umezawa et al., 2009; Vlad et al., 2009). Recently, function of plasma membrane-localized G protein-coupled receptor-type G proteins (GTGs) as ABA receptor in Arabidopsis has been shown (Pandey et al., 2009). Binding of ABA by GTG1/GTG2 and ABA hyposensitivity of GTG1/GTG2 Arabidopsis loss of function mutants supported a function of GTG1 and GTG2 as membrane-localized ABA receptors (Pandey et al., 2009). Extending the concept of involvement of GTG1 and GTG2 in ABA signaling, a role of the proteins in growth and development of Arabidopsis seedlings and in pollen tube growth by function as voltage-dependent anion channels has been reported (Jaffé et al., 2012). Thus, linking and dynamic integration of GTG1 and GTG2 in cellular ABA signaling and developmental regulation seems likely. Intriguingly, evidence for a third pathway of ABA perception has been emerging with the H subunit of Mg-chelatase (CHLH/ABAR). Integration of CHLH/ABAR in the cellular ABA signaling cascade as a chloroplastic ABA receptor and by plastid-to-nucleus retrograde signaling via the ABA responsive nucleocytoplasmic transcription repressor WRKY40 has been reported (Shen et al., 2006; Shang et al., 2010; Du et al., 2012). These findings strongly suggest contribution of a chloroplast-localized pathway to modulate cellular ABA signaling (Shen et al., 2006; Shang et al., 2010; Du et al., 2012).

Currently, increasing evidence has been emerging for modulation of ABA-mediated environmental signaling by interaction and competition with hormonal key regulators of plant cellular developmental and metabolic signaling. The complex and divergent endogenous and exogenous signals perceived by plant cells during development and environmental adversity are linked and integrated by distinct and interactive hormonal pathways. Particularly, convergence and functional modulation of ABA signaling by the plant growth regulating phytohormones gibberellic acid (GA) has a key regulatory function in the plant cellular network of stress and developmental signaling (Golldack et al., 2013). According to accepted concepts, in Arabidopsis GA signaling is mediated by binding of GA to GID1a/b/c that are GA receptor orthologs of the rice GA receptor gene OsGID1 (GA INSENSITIVE DWARF 1; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005; Griffiths et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2008). GA responsive GRAS [for GA Insensitive (GAI), REPRESSOR of ga1-3 (RGA), SCARECROW (SCR)] transcription factors function as major regulators in plant GA-controlled development. Cellular accumulation of the GRAS protein subgroup of DELLA proteins (GAI, RGA, RGL1, RGL2, RGL3) represses GA signaling and restrains growth and development (Cheng et al., 2004; Tyler et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004). Interaction of DELLA proteins with the GA receptor GID1 induces degradation of the DELLA proteins and activates the function of GA (Cheng et al., 2004; Tyler et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004). GA signals mediate binding of DELLA proteins to GID1 that is followed by conformational conversion of DELLA proteins. The modified DELLAs are recognized by the the F-box protein SLEEPY1 (SLY1) in Arabidopsis (Silverstone et al., 2001, 2007; Fu et al., 2002; Sasaki et al., 2003; Dill et al., 2004). Subsequently, DELLAs are polyubiquitinated by the SCFSLY1/GID2 ubiquitin E3 ligase complex and degraded via the 26S proteasome pathway (Silverstone et al., 2001; Fu et al., 2002; Sasaki et al., 2003; Dill et al., 2004).

A linking function of DELLA proteins at the interface of ABA-mediated abiotic stress responses and GA-controlled developmental signaling has been supported by modified salt tolerance of the quadruple DELLA mutant with functional losses of rga, gai, rgl1, and rgl2 (Achard et al., 2006). Interestingly, the RING-H2 zinc finger factor XERICO regulates tolerance to drought and ABA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Ko et al., 2006). In addition, XERICO is a transcriptional downstream target of DELLA proteins indicating function of XERICO as a node of plant abiotic stress responses and development by linking GA and ABA signaling pathways (Ko et al., 2006; Zentella et al., 2007; Ariizumi et al., 2013).

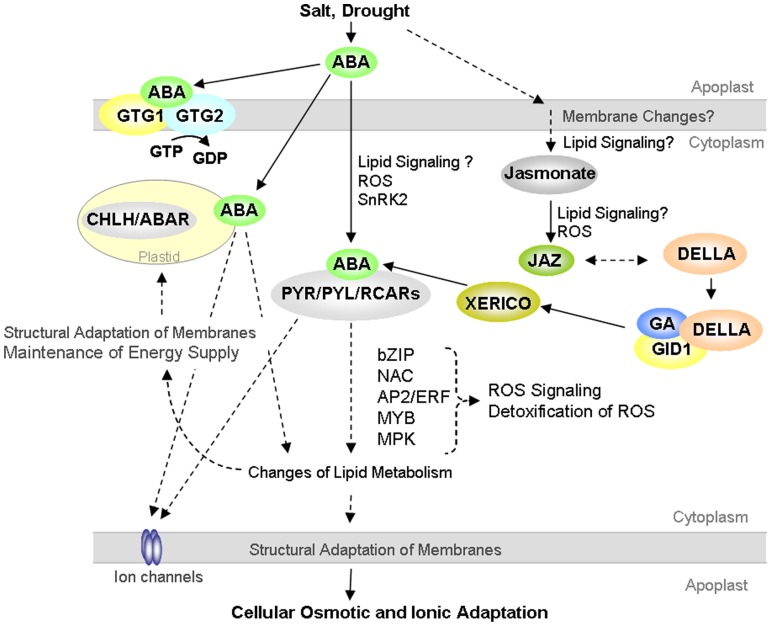

Recently, interesting evidence has been also provided for a convergence and crosstalk of GA and ABA signaling with the developmental regulator jasmonate in plant responses to drought. Jasmonates are membrane-lipid derived metabolites that originate from linolenic acid and have signaling functions in plant growth and biotic stress responses (e.g., Wasternack, 2007; Wasternack and Hause, 2013). Drought-induced transcriptional regulation of the rice JA receptor protein OsCOI1a (CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1) and of key regulators of JA signaling OsJAZ (jasmonic acid ZIM-domain proteins) indicate significant integration of JA metabolism and signaling in plant abiotic stress responses (Du et al., 2013a; Lee et al., 2013). Importantly, expression of the DELLA protein RGL3 responds to JA, and additionally RGL3 interacts with JAZ proteins (Wild et al., 2012). These recent research advances emphasize function of DELLAs as an interface of ABA, GA and jasmonic acid signaling and suggest pivotal functional involvement of lipid-derived signaling in abiotic stress responses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proposed model on crosstalk of abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellic acid (GA), and jasmonate signaling in plant cellular responses to the abiotic stressors drought and salt. Hypothesized links are illustrated with dashed lines. The lines and arrows illustrate pathways that are not shown and described in detail. Compare text for details.

MAJOR PLANT TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR FAMILIES: KEY PLAYERS IN THE REGULATORY NETWORKS UNDERLYING PLANT RESPONSES TO ABIOTIC STRESS

Comprehensive research on diverse abiotic stress responsive transcription factors shed light on the cellular mechanisms defining plant environmental adaptation (Golldack et al., 2011). Significantly, the majority of ABA-regulated genes share the conserved ABA-responsive cis element (ABRE; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005, 2006). Besides the AREB/ABF (ABA-responsive element binding protein/ABRE-binding factor) family, the DREB/CBF subfamily of the AP2/ERF transcription factors has a central function in regulating plant adaptation to adversity via ABA dependent and independent pathways (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005, 2006). Significant evidence for a linking function of DREB/CBF in integrating environmentally derived signals and plant development was early provided by DREB/CBF overexpressing Arabidopsis with increased tolerance to drought, salt, and cold that was counterbalanced by serious developmental defects (Kasuga et al., 1999). Supporting this functional connection, cold responsive CBF1 regulated GA biosynthesis and accumulation of the DELLA protein RGA thus suggesting integration of AP2/ERF in abiotic stress signaling and GA-regulated plant development (Achard et al., 2008). The bZIP-type AREB/ABF transcription factors AREB1, AREB2, and AREB3 target cooperatively ABRE-dependent gene expression via a suggested interaction with the sucrose non-fermenting 1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) protein kinase SRK2D/SnRK2.2 (Yoshida et al., 2010). In addition, the Arabidopsis transcription factor bZIP24 controls reprogramming of a broad array of salinity dependent and developmental gene expression indicating a pivotal role of the factor in maintaining plant development under conditions of adversity (Yang et al., 2009).

The view of an integrative function of many transcription factors in linking and balancing related or seemingly unrelated cellular responses is further supported by other drought and salt responsive transcription factors. Intriguingly, the picture is increasingly emerging that plant signaling does not function as independent and paralleled pathways but cellular crosstalks and hubs within the signaling network exist. The view is increasingly emerging that stress adaptive signaling is tightly linked to the cellular primary metabolism, energy supply and developmental processes. Thus, the tomato NAC-type (NAM, ATAF1,2, CUC2) transcription factor SlNAC1 was responsive to multiple abiotic and biotic stresses (Ma et al., 2013). Regulation of the factor by ABA, methyl jasmonate, gibberellin, and ethylene indicates a node role of the factor in diverse signal transduction pathways in tomato (Ma et al., 2013). The ABA-responsive NAC-transcription factor VNI2 (VND-INTERACTING1) is a repressor of xylem vessel formation and has additional functions in leaf aging thus integrating plant senescence to ABA signaling (Yang et al., 2011). As another example, the NAC transcription factor ANAC042 (JUB1, JUNGBRUNNEN 1) links leaf senescence to hyperosmotic salinity response and is involved in H2O2 signaling (Wu et al., 2012). Over-expression of the drought and ABA responsive rice NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC10 allowed identification of NAC dependent target genes that included AP2 and WRKY-type transcription factors (Jeong et al., 2010). These findings strongly indicate a hub role of NAC transcription factors in stress relevant hierarchic regulatory pathways.

Drought and ABA-responsive NAC factors are likely to control and link subclusters of cellular stress adaptation processes under control of diverse subsets of specific transcription factors such as members of the AP2 and WRKY families. Thus, hypersensitivity to drought of an Arabidopsis WRKY63 loss of function mutant was related to reduced ABA sensitivity in guard cells indicating specific control of abiotic stress adaptation by this WRKY transcription factor (Ren et al., 2010). ABA and salt responsive Arabidopsis WRKY33 downstream targets genes with functions in detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as glutathione S-transferase GSTU11, peroxidases, and lipoxygenase LOX1 (Jiang and Deyholos, 2009). According to the involvement of WRKY33 in osmotic stress responses, ROS detoxification and ROS scavenging, a role of WRKY controlled cellular ROS levels in abiotic stress signaling seems likely. Extending and supplementing this concept, the WRKY-type transcription factor ThWRKY4 from Tamarix hispida controls cellular accumulation of ROS via regulating expression and activity of antioxidant genes such as superoxide dismutase and peroxidase (Zheng et al., 2013). Modified tolerance of ThWRKY4 overexpressing plants to salt and oxidative stress was referred to ThWRKY4-mediated cellular protection against toxic ROS levels (Zheng et al., 2013). Accordingly, an involvement of WRKY in linking osmotic and oxidative stress defense as well as in ROS mediated signaling crosstalks is suggested.

Another crucial and undervalued mechanism of plant adaptation to drought and salinity is the maintenance of cell wall development and generation of the extracellular matrix in terms of plant development and of protection against water loss. Intriguingly, transcriptional expression of the Arabidopsis R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB41 was induced by drought, salt, and ABA (Cominelli et al., 2008; Lippold et al., 2009). Modified drought sensitivity of AtMYB41 overexpressing Arabidopsis was linked to lipid metabolism, cell wall expansion, and cuticle deposition demonstrating a key function of AtMYB41 in plant drought protection and survival via primary lipid metabolism and cuticle formation (Cominelli et al., 2008). Recently, function of AtMYB41 was also linked to primary carbon metabolism indicating a relationship between cuticle deposition, plant tolerance against desiccation as well as cellular lipid and carbon metabolism (Cominelli et al., 2008; Lippold et al., 2009). The salt-responsive rice R2R3-type MYB transcription factor OsMPS (MULTIPASS) targets genes with function in biosynthesis of phytohormones and of the cell-wall (Schmidt et al., 2013a). These recent research advances highlight the importance of a functional plant extracellular matrix and of cuticular polymer biosynthesis for plant salt and drought adaptation. Accordingly, a key function of stress responsive transcription factors in integrating cuticle formation in the cellular primary metabolism in response to environmental adversity is supported and likely.

LIPIDS: STILL AN ENIGMA IN ABIOTIC STRESS ADAPTATION AND STRESS DERIVED SIGNALING?

Plant adaptation to a changing water and ionic status in the surrounding environment requires rapid and sensitive sensing of the stress situation and stress induced signaling. A crucial and existential challenge for plant cells is the maintenance of integrity of cellular membranes both at the plasma membrane and of the enodomembranes. Thus, plants ensure homeostasis of metabolism and cellular energy supply. Additionally, increasing evidence for pivotal involvement of lipid-derived signaling in primary sensing of environmental changes and in triggering and regulating cellular hormonal signaling cascades has been emerging (Figure 1). Interestingly, vice versa ABA transcriptionally downstream targets lipid metabolism and lipid transfer proteins suggesting tight interaction of ABA-dependent signaling and lipid metabolic pathways to maintain structure and function of cellular membranes (Seki et al., 2002; Li et al., 2006). Thus, ABA-triggered modification of primary lipid metabolism contributes unequivocally to stress adaptive reorganization of membranes and to the maintenance of cellular energy supply under abiotic stress conditions and limitation in water supply. Increased transpirational water loss of Arabidopsis mutants with a functional knock out of LTP3 (Lipid Transfer Protein 3) suggests lipid-based adaptive changes of membranes and the plant cuticle to regulate water loss and transpiration under drought (Guo et al., 2013).

Drought-induced changes of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) contents in the chloroplast envelope and in thylakoid membranes in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) have been suggested to stabilize and maintain lamellar bilayer structure and thus the function of chloroplasts under drought stress (Torres-Franklin et al., 2007). In support of these findings, changes of MGDG in the drought tolerant resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum during desiccation are likely to contribute to membrane stabilization and to the maintenance of photosynthetic energy supply (Gasulla et al., 2013). The Arabidopsis cold-responsive SFR2 (SENSITIVE TO FREEZING 2) mediates removal of monogalactolipids from the chloroplast envelope membrane and stabilizes membranes during freezing indicating that structural re-shaping of chloroplast membranes is an essential and general mechanism of plant cellular dehydration responses (Moellering et al., 2010).

Next to strong evidences for a fundamental importance of lipid mediated re-organization of cellular membranes to cope with changes in the plant water status, also comprehensive evidence for functions of lipid signaling in plant drought and salt responses has been emerging. In rice, levels of PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate), PA (phosphatidic acid), and DGPP (diacylglycerolpyrophosphate) increased upon salt stress (Darwish et al., 2009). Based on these findings involvement of phospholipase C and diacylglycerol kinase in salt stress induced signaling has been hypothesized (Darwish et al., 2009). Function of phospholipase C was linked to ABA signaling and stomatal regulation indicating a functional role of phosphoinositides in guard cell signaling (Hunt et al., 2003; Mills et al., 2004). The inositol phosphate myo-inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) has a role as an ABA-responsive signaling molecule that regulates stomatal closure via cellular calcium and the plasma membrane potassium conductance (Lemtiri-Chlieh et al., 2003). Phosphoinositides have key roles in regulating membrane peripheral signaling proteins and influence the activity of integral proteins and ion channels (Suh et al., 2006; Falkenburger et al., 2010). Importantly, work on inhibitors of phosphoinositide-dependent phospholipases C (PI-PLCs) in Arabidopsis has provided considerable insight in the drought stress related lipid signaling by identifying links of phosphoinositides to the DREB2 pathway (Djafi et al., 2013).

A role of lipid-derived messengers in ABA signaling was also evident by ACBP1 (acyl-CoA-binding protein 1) regulated expression of PHOSPHOLIPASE Dα1 (PLDα1; Du et al., 2013b). PHOSPHOLIPASE Dα1 has a function in the biosynthesis of the ABA regulating lipid messenger PA indicating that modulation of cellular lipid profiles is essential for regulation of abiotic stress related ABA signaling (Du et al., 2013b; Jia et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2013).

SnRK2 AND MAPK: ANOTHER CHAPTER IN PLANT ABIOTIC STRESS SIGNALING

Protein kinases of diverse types and families are central integrators of plant abiotic stress signaling that link cellular metabolic signaling to stress adaptive physiological processes as regulation of ionic and osmotic homeostasis and to concerted changes of ROS in stressed plant cells (Figure 1). Accepted models emphasize hub functions of yeast sucrose non-fermenting 1 (SNF1) serine-threonine protein kinase, homologous mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and plant SnRKs [Snf (sucrose non-fermenting)-1-related protein kinases] in the cellular carbon and energy metabolism (Halford and Hey, 2009). In plants, SnRK1 subgroup kinases have reported functions in metabolic signaling and development (Zhang et al., 2001; Halford et al., 2003). Considerable insight into protein kinase functions in plant abiotic stress adaptation has been provided by elucidation of the SOS pathway with central functions in maintenance and regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Intriguingly, the SnRK3 SOS2-like (Salt Overly Sensitive3) protein kinases interact with SOS3-like calcium-binding proteins to activate the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 via the SOS pathway (Chinnusamy et al., 2004; Du et al., 2011). Recent research highlights direct interaction of SnRK2.8 and the ABA responsive NAC (NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2) transcription factor NTL6 indicating integration of a SnRK2-type kinase in the ABA controlled cellular framework of abiotic stress adaptation (Kim et al., 2012). Extending these findings, in rice, the SnRK2 kinase SAPK4 links regulation of ion homeostasis to scavenging of ROS thus suggesting interaction of ionic and oxidative stress signaling pathways in plant adaptation to adversity (Diédhiou et al., 2008). Consistent with these findings, a node function of SnRK2-type kinases in ABA signaling and ROS generation has been elucidated in stomatal guard cells. The ABA responsive SnRK2 OST1 (OPEN STOMATA 1) regulates stomatal closure by modulating the cellular production of H2O2 via NADPH oxidases (Sirichandra et al., 2009; Vlad et al., 2009). Arabidopsis OST1 mutants provided evidence for a role of OST1 in the regulation of inward K+ channels, Ca2+ -permeable channels and the slow anion channel SLAC1 thus supporting a hub function of OST1 in linking ABA, ion channels and NADPH oxidases in the regulation of stomatal apertures in guard cells (Sirichandra et al., 2009; Vlad et al., 2009; Acharya et al., 2013). As a fascinating finding, the Arabidopsis snrk2.2/2.3/2.6 triple-mutant with decreased sensitivity to ABA allowed identification of SnRK2 phosphorylation targets that included proteins with functions in chloroplasts, in signal transduction and in the regulation of flowering (Wang et al., 2013). These research advances provide insights in SnRK2-mediated regulatory crosstalks and interactions of developmental, metabolic and stress adaptive processes in the plant cellular signaling framework.

Recent advances on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) mediated signal transduction cascades have provided another pivotal understanding of the integration of physiological and cellular responses to environmental adversity. MAPK cascades functionally link MAP3Ks (MAP2K kinase) serine/threonine kinases, MAP2K (MAPK kinase) dual-specificity kinases and MAPK serine/threonine kinases (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008). As an accepted concept of functional importance in abiotic stress adaptation, involvement of MAPKs in drought and salt adaptation have been reported for wide ranging plant species such as rice, Arabidopsis to alfalfa SIMK and SIMKK (Kiegerl et al., 2000; Ning et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Recent research highlights a central role of Arabidopsis MKK4 in the osmotic stress response by regulation of MPK3 activity, accumulation of ROS and targeting the ABA biosynthetic process via NCED3 (NINE-CIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE 3; Kim et al., 2011). Several studies indicated a hub function of MPK6 as another member of the MAPK cascade in linking of osmotic stress responses to ROS and oxidative bursts. Thus, recent research has identified abiotic stress induced ROS accumulation under control of MPK6, MKK1, and MKKK20 supporting a dynamic control of the signaling component ROS by MPK6 and other components of the MAPK pathway (Xing et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012).

Novel findings uncover links of the MAPK cascade to cellular lipid transfer processes indicating a coupling of MAP-type kinases to stress adaptive changes of membranes, intracellular membrane trafficking or probably to stress-dependent lipid signaling. Thus, recent research advances proved direct regulation of MPK6 mediated phosphorylation of the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 by NaCl and by PA supporting relationships of lipids to MAPK signaling in plant salt stress responses (Yu et al., 2010). Integration of MPK6 in differential signaling pathways has been additionally reported by interaction of MPK6 with the Arabidopsis C2H2-type zinc finger protein ZAT6 that functions both in plant developmental processes and in osmotic stress responses (Liu et al., 2013b). In several recent studies, emphasis has been placed on detailed characterization of co-regulation and interaction of the MAP kinase pathway and ROS signaling within the cellular signaling framework thus further strengthening the understanding of MAP kinase as a hub in signaling under environmental adversity. In rice, the salt responsive MAPK cascade is linked to ROS signaling by the transcription factor SERF1 (salt-responsive ERF1; Schmidt et al., 2013b). Cotton MAPK GhMPK16 is functionally involved in pathogen resistance, drought tolerance and ROS accumulation indicating a role of GhMPK16 as an interface between biotic and abiotic stress signaling (Shi et al., 2011).

ROS SIGNALING IN PLANTS UNDER DROUGHT AND SALT STRESS

Current concepts emphasize a central function of cellular ROS as a signaling interface in plant drought and salt adaptation hat links stress signals to regulation of metabolism and the cellular energy balance (Figure 1). Significantly, environmental adversity such as drought and salinity impairs cellular ionic and osmotic homeostasis but additionally compromises photosynthesis, cellular energy depletion, and redox imbalances (e.g., Baena-González et al., 2007; Abogadallah, 2010; Jaspers and Kangasjärvi, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010). Excess generation and accumulation of ROS such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide cause oxidative damages in the apoplastic compartment and damages of cellular membranes by lipid peroxidation and have an extensive impact on ion homeostasis by interfering ion fluxes (Baier et al., 2005). Excess ROS amounts are particularly scavenged by antioxidant metabolites such as ascorbate, glutathione, tocopherols and by ROS detoxifying enzymes as superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, and catalase (Mittler, 2002; Neill et al., 2002). Current models emphasize a dual regulatory function of ROS as a signaling molecule in plant drought and osmotic stress tolerance by sensing the cellular redox state and in retrograde signaling. Studies on transcription factors of the WRKY and basic-helix-loop helix types enhanced the understanding of crosstalks of osmotic and oxidative stress responsive signaling pathways significantly. Thus, Arabidopsis WRKY33 responds to osmotic and oxidative stresses (Miller et al., 2008). Regulatory function of bHLH92 and WRKY33 in ROS detoxification by targeting peroxidases and glutathione-S-transferases suggested a function of the transcription factors in linking ROS scavenging to osmotic and oxidative stress induced signaling (Miller et al., 2008; Jiang and Deyholos, 2009; Jiang et al., 2009). Recent research advances linked the regulation of Arabidopsis salt and osmotic stress tolerance to ROS-responsive WRKY15 and mitochondrial retrograde signaling (Vanderauwera et al., 2012). Another recent advance in understanding the importance of ROS in plant salt responses was the discovery of a coupled function of plastid heme oxygenases and ROS production in salt acclimation (Xie et al., 2011). These findings strongly suggest involvement of the chloroplast to nucleus signaling pathway in plant salt adaptation (Xie et al., 2011). Additionally, work on cross-species expression of a SUMO conjugating enzyme has provided considerable insight into the links of ROS, ABA dependent signaling and the sumoylation pathway in plant salt and drought tolerance (Karan and Subudhi, 2012). Functional relation of the maize bZIP transcription factor ABP9, glutamate carboxypeptidase AMP1, and the ankyrin-repeat protein ITN1 to ABA signaling, ROS generation and ROS scavenging further support interaction and correlation of ABA and ROS related pathways as signaling nodes in plant adaptation to drought and salt (Sakamoto et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2013).

THE SPECIFIC FUNCTION OF STOMATAL SIGNALING IN PLANT DROUGHT AND SALT TOLERANCE

Constant dynamic regulation of stomatal aperture is obligatory for successful adaptation of plants to abiotic stresses. Prevention of excess water loss via transpiration depends on reliable adjustment of stomatal closure to environmental adversity. Hence, elucidation of sensing and signaling in stomatal guard cells has been attracting particular attention to understand regulation of stomatal conductance under conditions of drought and salinity. As another example, in maize mutants of the E3 ubiquitin ligase ZmRFP1, enhanced drought tolerance and decreased ROS accumulation indicated linked regulation of stomatal closure and ROS scavenging (Liu et al., 2013a). The Arabidopsis plasma membrane receptor kinase, GHR1 (GUARD CELL HYDROGEN PEROXIDE-RESISTANT1) linked ABA and H2O2 signaling in stomatal closure (Hua et al., 2012). In addition, GHR1 regulated an S-type anion channel suggesting a node function of this receptor kinase in ion homeostasis, ABA and H2O2 mediated signaling pathways in guard cells (Hua et al., 2012).

As aforementioned, the SnRK2 protein kinase OST1 (SnRK2 OPEN STOMATA 1) is a central regulator of stomatal aperture and links guard cell movement to the ABA signaling network (Sirichandra et al., 2009). OST1 targets NADPH oxidases, inward K+ channels, Ca2+ -permeable channels and the slow anion channel SLAC1 in stomatal guard cells (Sirichandra et al., 2009; Vlad et al., 2009; Acharya et al., 2013). In addition, the SnRK2 protein kinase OST1 also targets voltage-dependent quickly activating anion channels of the R-/QUAC-type in guard cells (Imes et al., 2013). These data suggest coordinated control of SLAC1-mediated transport of chloride and nitrate and QUAC1-mediated transport of malate in the same ABA signaling pathway (Imes et al., 2013). Recently, the finding of direct dephosphorylation of SLAC1 by the PP2C (protein phosphatase 2C) ABI1 provided interesting evidence for a specific alternative regulatory mechanism of the anion channel SLAC1 (Brandt et al., 2012).

Recent research uncovered co-regulation of ABA-induced stomatal closure, guard cell H+-ATPase and Mg-chelatase H subunit (CHLH; Tsuzuki et al., 2013). CHLH/ABAR is involved in the chlorophyll biosynthetic process and a function of CHLH/ABAR as a chloroplastic ABA receptor via plastid-to-nucleus retrograde ABA signaling has been suggested (Shen et al., 2006; Shang et al., 2010; Du et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, functional mutation of CHLH affected phosphorylation of H+-ATPase and blue light dependent stomatal regulation (Tsuzuki et al., 2013). These findings validate importance of CHLH in linking the ABA signaling network to the regulation of ionic homeostasis and blue light responses in guard cells and plant drought tolerance (Tsuzuki et al., 2013). Interestingly, ABA-dependent regulation of stomatal closure responds to mutation of the phosphate transporter PHO1 and the vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit A (Zimmerli et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013). Again, these results support interaction and co-regulation of ion homeostasis in guard cells via ion transport, ABA signaling, and regulation of stomatal aperture (Zimmerli et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013). Intriguingly, the transporter ZIFL1 (Induced Facilitator-Like 1) mediates potassium fluxes and has a dual function in regulating both cellular auxin transport and stomatal closure (Remy et al., 2013).

In conclusion, recent research advances have elucidated a molecular cellular signaling network for the understanding how plants control and regulate adaptation to the abiotic stresses drought and salinity. Essentially, molecular signaling components in plant adaptation to environmental adversity have been connected to hub transcription factors, MAPK pathways, ROS and lipid-derived pathways. Importantly, it is expected that further and perspective advances in the network modeling of cellular abiotic stress signaling will provide new and efficient strategies for improving environmental tolerance in crops.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abogadallah G. M. (2010). Antioxidative defense under salt stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 5 369–374 10.4161/psb.5.4.10873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Cheng H., De Grauwe L., Decat J., Schoutteten H., Moritz T., et al. (2006). Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science 311 91–94 10.1126/science.1118642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Gong F., Cheminant S., Alioua M., Hedden P., Genschik P. (2008). The cold-inducible CBF1 factor-dependent signaling pathway modulates the accumulation of the growth-repressing DELLA proteins via its effect on gibberellin metabolism. Plant Cell 20 2117–2129 10.1105/tpc.108.058941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya B. R., Jeon B. W., Zhang W., Assmann S. M. (2013). Open Stomata 1 (OST1) is limiting in abscisic acid responses of Arabidopsis guard cells. New Phytol. 200 1049–1063 10.1111/nph.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P. K., Shukla P. S., Gupta K., Jha B. (2013). Bioengineering for salinity tolerance in plants: state of the art. Mol. Biotechnol. 54 102–123 10.1007/s12033-012-9538-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T., Hauvermale A. L., Nelson S. K., Hanada A., Yamaguchi S., Steber C. M. (2013). Lifting della repression of Arabidopsis seed germination by nonproteolytic gibberellin signaling. Plant Physiol. 162 2125–2139 10.1104/pp.113.219451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M., Akram N. A. (2009). Improving salinity tolerance of plants through conventional breeding and genetic engineering: an analytical comparison. Biotechnol. Adv. 27 744–752 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-González E., Rolland F., Thevelein J. M., Sheen J. (2007). A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448 938–942 10.1038/nature06069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier M., Kandlbinder A., Golldack D., Dietz K. J. (2005). Oxidative stress and ozone: perception, signalling and response. Plant Cell Environ. 28 1012–1020 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01326.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt B., Brodsky D. E., Xue S., Negi J., Iba K., Kangasjärvi J., et al. (2012). Reconstitution of abscisic acid activation of SLAC1 anion channel by CPK6 and OST1 kinases and branched ABI1 PP2C phosphatase action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 10593–10598 10.1073/pnas.1116590109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Hong X., Zhang H., Wang Y., Li X., Zhu J. K., et al. (2005). Disruption of the cellulose synthase gene, AtCesA8/IRX1, enhances drought and osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 43 273–283 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Qin L., Lee S., Fu X., Richards D. E., Cao D., et al. (2004). Gibberellin regulates Arabidopsis floral development via suppression of DELLA protein function. Development 131 1055–1064 10.1242/dev.00992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V., Schumaker K., Zhu J. K. (2004). Molecular genetic perspectives on cross-talk and specificity in abiotic stress signalling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 55 225–236 10.1093/jxb/erh005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet J., Hirt H. (2008). Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem. J. 413 217–226 10.1042/BJ20080625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cominelli E., Sala T., Calvi D., Gusmaroli G., Tonelli C. (2008). Over-expression of the Arabidopsis AtMYB41 gene alters cell expansion and leaf surface permeability. Plant J. 53 53–64 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Finkelstein R. R., Abrams S. R. (2010). Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 651–679 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish E., Testerink C., Khalil M., El-Shihy O., Munnik T. (2009). Phospholipid signaling responses in salt-stressed rice leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 986–997 10.1093/pcp/pcp051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diédhiou C. J., Popova O. V., Dietz K. J., Golldack D. (2008). The SNF1-type serine-threonine protein kinase SAPK4 regulates stress-responsive gene expression in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 8:49 10.1186/1471-2229-8-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill A., Thomas S. G., Hu J., Steber C. M., Sun T. P. (2004). The Arabidopsis F-box protein SLEEPY1 targets GA signaling repressors for GA-induced degradation. Plant Cell 16 1392–1405 10.1105/tpc.020958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djafi N., Vergnolle C., Cantrel C., Wietrzyñski W., Delage E., Cochet F., et al. (2013). The Arabidopsis DREB2 genetic pathway is constitutively repressed by basal phosphoinositide-dependent phospholipase C coupled to diacylglycerol kinase. Front. Plant Sci. 4:307 10.3389/fpls.2013.00307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Liu H., Xiong L. (2013a). Endogenous auxin and jasmonic acid levels are differentially modulated by abiotic stresses in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 4:397 10.3389/fpls.2013.00397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z. Y., Chen M. X., Chen Q. F., Xiao S., Chye M. L. (2013b). Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP1 participates in the regulation of seed germination and seedling development. Plant J. 74 294–309 10.1111/tpj.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du S. Y., Zhang X. F., Lu Z., Xin Q., Wu Z., Jiang T., et al. (2012). Roles of the different components of magnesium chelatase in abscisic acid signal transduction. Plant Mol. Biol. 80 519–537 10.1007/s11103-012-9965-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Lin H., Chen S., Wu Y., Zhang J., Fuglsang A. T., et al. (2011). Phosphorylation of SOS3-like calcium-binding proteins by their interacting SOS2-like protein kinases is a common regulatory mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 156 2235–2243 10.1104/pp.111.173377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger B. H., Jensen J. B., Dickson E. J., Suh B. C., Hille B. (2010). Phosphoinositides: lipid regulators of membrane proteins. J. Physiol. 588 3179–3185 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Martinez C., Gusmaroli G., Wang Y., Zhou J., Wang F., et al. (2008). Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451 475–479 10.1038/nature06448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers T. J. (2004). Improving crop salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 55 307–319 10.1093/jxb/erh003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Richards D. E., Ait-ali T., Hynes L. W., Ougham H., Peng J., et al. (2002). Gibberellin-mediated proteasome-dependent degradation of the barley DELLA protein SLN1 repressor. Plant Cell 14 3191–3200 10.1105/tpc.006197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasulla F., Vom Dorp K., Dombrink I., Zähringer U., Gisch N., Dörmann P., et al. (2013). The role of lipid metabolism in the acquisition of desiccation tolerance in Craterostigma plantagineum: a comparative approach. Plant J. 75 726–741 10.1111/tpj.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray H. C., Beddington J. R., Crute I. R., Haddad L., Lawrence D., Muir J. F., et al. (2010). Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327 812–818 10.1126/science.1185383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golldack D., Li C., Mohan H., Probst N. (2013). Gibberellins and abscisic acid signal crosstalk: living and developing under unfavorable conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 32 1007–1016 10.1007/s00299-013-1409-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golldack D., Lüking I., Yang O. (2011). Plant tolerance to drought and salinity: stress regulating transcription factors and their functional significance in the cellular transcriptional network. Plant Cell Rep. 30 1383–1391 10.1007/s00299-011-1068-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J., Murase K., Rieu I., Zentella R., Zhang Z. L., Powers S. J., et al. (2006). Genetic characterization and functional analysis of the GID1 gibberellin receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 3399–3414 10.1105/tpc.106.047415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Yang H., Zhang X., Yang S. (2013). Lipid transfer protein 3 as a target of MYB96 mediates freezing and drought stress in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 64 1755–1767 10.1093/jxb/ert040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford N. G., Hey S. J. (2009). Snf1-related protein kinases (SnRKs) act within an intricate network that links metabolic and stress signalling in plants. Biochem. J. 419 247–259 10.1042/BJ20082408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford N. G., Hey S., Jhurreea D., Laurie S., McKibbin R. S., Paul M., et al. (2003). Metabolic signalling and carbon partitioning: role of Snf1-related (SnRK1) protein kinase. J. Exp. Bot. 54 467–475 10.1093/jxb/erg038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa P. M., Bressan R. A., Zhu J. K., Bohnert H. J. (2000). Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu. Rev. Plant Phys. 51 463–499 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey S. J., Byrne E., Halford N. G. (2010). The interface between metabolic and stress signalling. Ann. Bot. 105 197–203 10.1093/aob/mcp285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua D., Wang C., He J., Liao H., Duan Y., Zhu Z., et al. (2012). A plasma membrane receptor kinase, GHR1, mediates abscisic acid- and hydrogen peroxide-regulated stomatal movement in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 2546–2561 10.1105/tpc.112.100107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L., Mills L. N., Pical C., Leckie C. P., Aitken F. L., Kopka J., et al. (2003). Phospholipase C is required for the control of stomatal aperture by ABA. Plant J. 34 47–55 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imes D., Mumm P., Böhm J., Al-Rasheid K. A., Marten I., Geiger D., et al. (2013). Open stomata 1 (OST1) kinase controls R-type anion channel QUAC1 in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 74 372–382 10.1111/tpj.12133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé F. W., Freschet G. E., Valdes B. M., Runions J., Terry M. J., Williams L. E. (2012). G protein-coupled receptor-type G proteins are required for light-dependent seedling growth and fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 3649–3668 10.1105/tpc.112.098681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers P, Kangasjärvi J. (2010). Reactive oxygen species in abiotic stress signaling. Physiol. Plant. 138 405–413 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. S., Kim Y. S., Baek K. H., Jung H., Ha S. H., Do Choi Y., et al. (2010). Root-specific expression of OsNAC10 improves drought tolerance and grain yield in rice under field drought conditions. Plant Physiol. 153 185–197 10.1104/pp.110.154773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Tao F., Li W. (2013). Lipid profiling demonstrates that suppressing Arabidopsis phospholipase Dδ retards ABA-promoted leaf senescence by attenuating lipid degradation. PLoS ONE 8:e65687 10.1371/journal.pone.0065687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Deyholos M. K. (2009). Functional characterization of Arabidopsis NaCl-inducible WRKY25 and WRKY33 transcription factors in abiotic stresses. Plant Mol. Biol. 69 91–105 10.1007/s11103-008-9408-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Yang B., Deyholos M. K. (2009). Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis bHLH92 transcription factor in abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 282 503–516 10.1007/s00438-009-0481-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karan R., Subudhi P. K. (2012). A stress inducible SUMO conjugating enzyme gene (SaSce9) from a grass halophyte Spartina alterniflora enhances salinity and drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 12:187 10.1186/1471-2229-12-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga M., Liu Q., Miura S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (1999). Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat. Biotechnol. 17 287–291 10.1038/7036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiegerl S., Cardinale F., Siligan C., Gross A., Baudouin E., Liwosz A., et al. (2000). SIMKK, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase, is a specific activator of the salt stress-induced MAPK, SIMK. Plant Cell 12 2247–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M., Woo D. H., Kim S. H., Lee S. Y., Park H. Y., Seok H. Y., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis MKKK20 is involved in osmotic stress response via regulation of MPK6 activity. Plant Cell Rep. 31 217–224 10.1007/s00299-011-1157-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. H., Woo D. H., Kim J. M., Lee S. Y., Chung W. S., Moon Y. H. (2011). Arabidopsis MKK4 mediates osmotic-stress response via its regulation of MPK3 activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 412 150–154 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J. H., Yang S. H., Han K. H. (2006). Upregulation of an Arabidopsis RING-H2 gene, XERICO, confers drought tolerance through increased abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 47 343–355 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Seo J. S., Cho J. H., Jung H., Kim J. K., Lee J. S., et al. (2013). Oryza sativa COI homologues restore jasmonate signal transduction in Arabidopsis coi1-1 mutants. PLoS ONE 8:e52802 10.1371/journal.pone.0052802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemtiri-Chlieh F., MacRobbie E. A., Webb A. A., Manison N. F., Brownlee C., Skepper J. N., et al. (2003). Inositol hexakisphosphate mobilizes an endomembrane store of calcium in guard cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10091–10095 10.1073/pnas.1133289100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lee K. K., Walsh S., Smith C., Hadingham S., Sorefan K., et al. (2006). Establishing glucose- and ABA-regulated transcription networks in Arabidopsis by microarray analysis and promoter classification using a Relevance Vector Machine. Genome Res. 16 414–427 10.1101/gr.4237406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold F., Sanchez D. H., Musialak M., Schlereth A., Scheible W. R., Hincha D. K., et al. (2009). AtMyb41 regulates transcriptional and metabolic responses to osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149 1761–1772 10.1104/pp.108.134874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xia Z., Wang M., Zhang X., Yang T., Wu J. (2013a). Overexpression of a maize E3 ubiquitin ligase gene enhances drought tolerance through regulating stomatal aperture and antioxidant system in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 73 114–120 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. M., Nguyen X. C., Kim K. E., Han H. J., Yoo J., Lee K., et al. (2013b). Phosphorylation of the zinc finger transcriptional regulator ZAT6 by MPK6 regulates Arabidopsis seed germination under salt and osmotic stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 430 1054–1059 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Bahn S. C., Qu G., Qin H., Hong Y., Xu Q., et al. (2013). Increased expression of phospholipase Dα1 in guard cells decreases water loss with improved seed production under drought in Brassica napus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 11 380–389 10.1111/pbi.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N. N., Zuo Y. Q., Liang X. Q., Yin B., Wang G. D., Meng Q. W. (2013). The multiple stress-responsive transcription factor SlNAC1 improves the chilling tolerance of tomato. Physiol. Plant. 10.1111/ppl.12049 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Szostkiewicz I., Korte A., Moes D., Yang Y., Christmann A., et al. (2009). Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324 1064–1068 10.1126/science.1172408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G., Shulaev V., Mittler R. (2008). Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 133 481–489 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G., Suzuki N., Ciftci-Yilmaz S., Mittler R. (2010). Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 33 453–467 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills L. N., Hunt L., Leckie C. P., Aitken F. L., Wentworth M., McAinsh M. R., et al. (2004). The effects of manipulating phospholipase C on guard cell ABA-signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 55 199–204 10.1093/jxb/erh027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 7 405–410 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering E. R., Muthan B., Benning C. (2010). Freezing tolerance in plants requires lipid remodeling at the outer chloroplast membrane. Science 330 226–228 10.1126/science.1191803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. (2005). Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol. 167 645–663 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill S., Desikan R., Hancock J. (2002). Hydrogen peroxide signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5 388–395 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00282-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning J., Li X., Hicks L. M., Xiong L. (2010). A Raf-like MAPKKK gene DSM1 mediates drought resistance through reactive oxygen species scavenging in rice. Plant Physiol. 152 876–890 10.1104/pp.109.149856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S., Nelson D. C., Assmann S. M. (2009). Two novel GPCR-type G proteins are abscisic acid receptors in Arabidopsis. Cell 136 136–148 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Fung P., Nishimura N., Jensen D. R., Fujii H., Zhao Y., et al. (2009). Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324 1068–1071 10.1126/science.1173041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra A. S., Gonugunta V. K., Christmann A., Grill E. (2010). ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 15 395–401 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy E., Cabrito T. R., Baster P., Batista R. A., Teixeira M. C., Friml J., et al. (2013). A major facilitator superfamily transporter plays a dual role in polar auxin transport and drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 901–926 10.1105/tpc.113.110353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Chen Z., Liu Y., Zhang H., Zhang M., Liu Q., et al. (2010). ABO3, a WRKY transcription factor, mediates plant responses to abscisic acid and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63 417–429 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04248.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H., Matsuda O., Iba K. (2008). ITN1, a novel gene encoding an ankyrin-repeat protein that affects the ABA-mediated production of reactive oxygen species and is involved in salt-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 56 411–422 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03614.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Itoh H., Gomi K., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ishiyama K., Kobayashi M., et al. (2003). Accumulation of phosphorylated repressor for gibberellin signaling in an F-box mutant. Science 299 1896–1898 10.1126/science.1081077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R., Schippers J. H., Mieulet D., Obata T., Fernie A. R., Guiderdoni E., et al. (2013a). MULTIPASS, a rice R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, regulates adaptive growth by integrating multiple hormonal pathways. Plant J. 76 258–273 10.1111/tpj.12286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R., Mieulet D., Hubberten H. M., Obata T., Hoefgen R., Fernie A. R., et al. (2013b). Salt-responsive ERF1 regulates reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling during the initial response to salt stress in rice. Plant Cell 25 2115–2131 10.1105/tpc.113.113068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki M., Narusaka M., Ishida J., Nanjo T., Fujita M., Oono Y., et al. (2002). Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant J. 31 279–292 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Yan L., Liu Z. Q., Cao Z., Mei C., Xin Q., et al. (2010). The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell 22 1909–1935 10.1105/tpc.110.073874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. Y., Wang X. F., Wu F. Q., Du S. Y., Cao Z., Shang Y., et al. (2006). The Mg-chelatase H subunit is an abscisic acid receptor. Nature 443 823–826 10.1038/nature05176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhang L., An H., Wu C., Guo X. (2011). GhMPK16, a novel stress-responsive group D MAPK gene from cotton, is involved in disease resistance and drought sensitivity. BMC Mol. Biol. 12:22 10.1186/1471-2199-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Wang Z., Meng P., Tian S., Zhang X., Yang S. (2013). The glutamate carboxypeptidase AMP1 mediates abscisic acid and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 199 135–150 10.1111/nph.12275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone A. L., Jung H. S., Dill A., Kawaide H., Kamiya Y., Sun T. P. (2001). Repressing a repressor: gibberellin-induced rapid reduction of the RGA protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13 1555–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone A. L., Tseng T. S., Swain S., Dill A., Jeong S. Y., Olszewski N. E., et al. (2007). Functional analysis of SPINDLY in gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 143 987–1000 10.1104/pp.106.091025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichandra C., Gu D., Hu H. C., Davanture M., Lee S., Djaoui M., et al. (2009). Phosphorylation of the Arabidopsis AtrbohF NADPH oxidase by OST1 protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 583 2982–2986 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B. C., Inoue T., Meyer T., Hille B. (2006). Rapid chemically induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science 314 1454–1457 10.1126/science.1131163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester M., Langridge P. (2010). Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science 327 818–822 10.1126/science.1183700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Franklin M. L., Gigon A., de Melo D. F., Zuily-Fodil Y., Pham-Thi A. T. (2007). Drought stress and rehydration affect the balance between MGDG and DGDG synthesis in cowpea leaves. Physiol. Plant. 131 201–210 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki T., Takahash K., Tomiyama M., Inoue S., Kinoshita T. (2013). Overexpression of the Mg-chelatase H subunit in guard cells confers drought tolerance via promotion of stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 4:440 10.3389/fpls.2013.00440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler L., Thomas S. G., Hu J., Dill A., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., et al. (2004). Della proteins and gibberellin-regulated seed germination and floral development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135 1008–1019 10.1104/pp.104.039578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ashikar M., Nakajima M., Itoh H., Katoh E., Kobayashi M., et al. (2005). GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 encodes a soluble receptor for gibberellin. Nature 437 693–698 10.1038/nature04028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Sugiyama N., Mizoguchi M., Hayash S., Myouga F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2009). Type 2C protein phosphatases directly regulate abscisic acid-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 17588–17593 10.1073/pnas.0907095106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderauwera S., Vandenbroucke K., Inzé A., van de Cotte B., Mühlenbock P., De Rycke R., et al. (2012). AtWRKY15 perturbation abolishes the mitochondrial stress response that steers osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 20113–20118 10.1073/pnas.1217516109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad F., Rubio S., Rodrigues A., Sirichandra C., Belin C., Robert N., et al. (2009). Protein phosphatases 2C regulate the activation of the Snf1-related kinase OST1 by abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 3170–3184 10.1105/tpc.109.069179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Xue L., Batelli G., Lee S., Hou Y. J., Van Oosten M. J., et al. (2013). Quantitative phosphoproteomics identifies SnRK2 protein kinase substrates and reveals the effectors of abscisic acid action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 11205–11210 10.1073/pnas.1308974110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C. (2007). Jasmonates: an update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot. 100 681–697 10.1093/aob/mcm079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C., Hause B. (2013). Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann. Bot. 111 1021–1058 10.1093/aob/mct067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. J., Peterson F. C., Volkman B. F., Cutler S. R. (2010). Structural and functional insights into core ABA signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 495–502 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild M., Davière J. M., Cheminant S., Regnault T., Baumberger N., Heintz D., et al. (2012). The Arabidopsis DELLA RGA-LIKE3 is a direct target of MYC2 and modulates jasmonate signaling responses. Plant Cell 24 3307–3319 10.1105/tpc.112.101428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A., Allu A. D., Garapati P., Siddiqui H., Dortay H., Zanor M. I., et al. (2012). JUNGBRUNNEN1, a reactive oxygen species-responsive NAC transcription factor, regulates longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 482–506 10.1105/tpc.111.090894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. J., Xu S., Han B., Wu M. Z., Yuan X. X., Han Y., et al. (2011). Evidence of Arabidopsis salt acclimation induced by up-regulation of HY1 and the regulatory role of RbohD-derived reactive oxygen species synthesis. Plant J. 66 280–292 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04488.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Jia W., Zhang J. (2008). AtMKK1 mediates ABA-induced CAT1 expression and H2O2 production via AtMPK6-coupled signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 54 440–451 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2005). Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 10 88–94 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2006). Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 781–803 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang O., Popova O. V., Süthoff U., Lüking I., Dietz K. J., Golldack D. (2009). The Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factor AtbZIP24 regulates complex transcriptional networks involved in abiotic stress resistance. Gene 436 45–55 10.1016/j.gene.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. D., Seo P. J., Yoon H. K., Park C. M. (2011). The Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor VNI2 integrates abscisic acid signals into leaf senescence via the COR/RD genes. Plant Cell 23 2155–2168 10.1105/tpc.111.084913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., Fujita Y., Sayama H., Kidokoro S., Maruyama K., Mizoi J., et al. (2010). AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 61 672–685 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Ito T., Zhao Y., Peng J., Kumar P., Meyerowitz E. M. (2004). Floral homeotic genes are targets of gibberellin signaling in flower development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 7827–7832 10.1073/pnas.0402377101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Nie J., Cao C., Jin Y., Yan M., Wang F., et al. (2010). Phosphatidic acid mediates salt stress response by regulation of MPK6 in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 188 762–773 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R., Zhang Z. L., Park M., Thomas S. G., Endo A., Murase K., et al. (2007). Global analysis of della direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 3037–3057 10.1105/tpc.107.054999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Niu X., Liu J., Xiao F., Cao S., Liu Y. (2013). RNAi-directed downregulation of vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit a results in enhanced stomatal aperture and density in rice. PLoS ONE 8:e69046 10.1371/journal.pone.0069046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang L., Meng H., Wen H., Fan Y., Zhao J. (2011). Maize ABP9 enhances tolerance to multiple stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis by modulating ABA signaling and cellular levels of reactive oxygen species. Plant Mol. Biol. 75 365–378 10.1007/s11103-011-9732-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Shewry P. R., Jones H., Barcelo P., Lazzeri P. A., Halford N. G. (2001). Expression of antisense SnRK1 protein kinase sequence causes abnormal pollen development and male sterility in transgenic barley. Plant J. 28 431–441 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Liu G., Meng X., Liu Y., Ji X., Li Y., et al. (2013). A WRKY gene from Tamarix hispida, ThWRKY4, mediates abiotic stress responses by modulating reactive oxygen species and expression of stress-responsive genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 82 303–320 10.1007/s11103-013-0063-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Lee B. H., Dellinger M., Cui X., Zhang C., Wu S., et al. (2010). A cellulose synthase-like protein is required for osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63 128–140 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04227.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli C., Ribot C., Vavasseur A., Bauer H., Hedrich R., Poirier Y. (2012). PHO1 expression in guard cells mediates the stomatal response to abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 72 199–211 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]