Abstract

Background

Recent proposals suggest that risk-stratified analyses of clinical trials be routinely performed to better enable tailoring of treatment decisions to individuals. Trial data can be stratified using externally developed risk models (e.g. Framingham risk score), but such models are not always available. We sought to determine whether internally developed risk models, developed directly on trial data, introduce bias compared to external models.

Methods and Results

We simulated a large patient population with known risk factors and outcomes. Clinical trials were then simulated by repeatedly drawing from the patient population assuming a specified relative treatment effect in the experimental arm, which either did or did not vary according to a subjects baseline risk. For each simulated trial, two internal risk models were developed on either the control population only (internal controls only, ICO) or on the whole trial population blinded to treatment (internal whole trial, IWT). Bias was estimated for the internal models by comparing treatment effect predictions to predictions from the external model.

Under all treatment assumptions, internal models introduced only modest bias compared to external models. The magnitude of these biases were slightly smaller for IWT models than for ICO models. IWT models were also slightly less sensitive to bias introduced by overfitting and less sensitive to falsely identifying the existence of variability in treatment effect across the risk spectrum than ICO models.

Conclusions

Appropriately developed internal models produce relatively unbiased estimates of treatment effect across the spectrum of risk. When estimating treatment effect, internally developed risk models using both treatment arms should, in general, be preferred to models developed on the control population.

Keywords: clinical trials, modeling

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are generally considered positive if the mean outcome in treated patients is superior to the mean outcome in the control arm. While this approach has the virtue of simplicity, it has been criticized for offering limited guidance for whether individual patients ought be treated. In some strongly positive trials, it is possible that a majority of patients receive little to no benefit, or even harm from treatment. 1,2 Unfortunately, patients have so many characteristics that might potentially influence the benefit of therapy that examining each using traditional subgroup analyses is often not informative. In addition to the well appreciated issues of multiplicity leading to false positives and low power leading to false negatives, traditional subgroup analyses may fail to detect clinically-relevant differences in treatment effects between groups that can be identified only when a combination of clinical variables are considered.3–5

It is increasingly recognized that a patient’s baseline risk is a fundamental determinant of treatment benefit. Indeed, many treatment guidelines have adopted risk-sensitive treatment recommendations. Perhaps the most notable examples within the field of preventive cardiology are recommendations to initiate statin6,7 or aspirin8 therapy contingent on baseline risk of cardiovascular disease. While there are many examples in other fields as well, the empirical evidence supporting these guidelines is not always clear and details on how to implement guidelines is often lacking.9 A better evidence base for risk-based treatment recommendations might be available if clinical trials were analyzed using multivariable risk prediction methods, and it has recently been proposed that such methods be routinely applied.10 This approach can provide better estimates of how the degree of benefit and/or harm of a medical intervention varies across patients in the trial based upon their overall risk of the study’s outcomes. This technique relies on a modeling approach that separately estimates baseline risk — typically, although not necessarily11,12, using an independently derived predictive model to estimate the baseline outcome risk for individual study subjects (e.g. Framingham risk score for the prediction of stroke/MI risk) and then estimates treatment effect as a function of this baseline risk. Such a model tests whether lower risk subjects receive similar proportional benefit as higher risk subjects using a treatment-baseline risk interaction term. While not exploring every potentially clinically-relevant hypothesis regarding heterogeneity of treatment effect (HTE), this approach examines the influence of a highly relevant mathematical determinant of treatment effect that integrates many patient characteristics in a multivariable framework, greatly mitigating some of the limitations of conventional subgroup analyses by minimizing the risk of multiple comparisons producing spurious findings5,13 and delivers “individualized” estimates of treatment effect.14–17 An additional virtue of this approach is that even when the proportional treatment effect does not differ across the spectrum of baseline risk (i.e. relative risk is constant across the baseline risk spectrum), this approach is well-suited to showing how absolute treatment benefit varies based on baseline risk, which is often the most relevant metric for clinical decision-making.

One proposal suggests that externally developed risk prediction tools should be routinely used for multivariable risk assessment of HTE.10 However, some clinical trials lack validated preexisting risk models for their main outcome (particularly composite outcomes) or the data may in other respects not be fully compatible with a published model (e.g. model variables may be differently defined). In cases where no well accepted external model exists to estimate baseline outcome risk, it is tempting to use the RCT data itself to design a baseline risk model and examine treatment effect across risk defined by that internal risk model — an approach recently applied to the JUPITER trial.17 Yet whether internally developed risk tools may introduce bias in the estimation of treatment effect across different risk categories has not been formally evaluated. An additional important question is what are the relative merits and risks of developing internal models on the whole trial population — including those patients who receive treatment — versus on the untreated (control) arm only. Deriving a model using only the control arm has intuitive appeal — since arguably such a model best represents the patients pre-treatment baseline risk; yet, this approach may also lead to differences in model fitness between trial arms, thus inducing bias. Using simulation analyses based on cardiovascular disease prevention trials we sought to examine whether using internal models developed either on the whole trial or in the controls only, compared to using an external model, results in biased estimates of the relationship between baseline risk and treatment effect.

Methods

Overview

To compare internal and external model bias and determine whether internal whole trial (IWT) or internal controls only (ICO) models lead to less bias and under what circumstances, we compared ICO, IWT and external models under a variety of treatment effect scenarios. Specifically, we designed four different treatment effect scenarios that varied the magnitude of the treatment effect and whether there was a main treatment effect (i.e., an average positive effect in the study population representing a constant relative risk reduction), risk-stratified HTE (i.e., the treatment effect varied as a function of a subject’s baseline risk for the study’s outcome) or both. For each of the four scenarios, we simulated a very large study population with risk factors that predicted outcomes in a pre-specified pattern (true risk factors), other potential risk factors that correlated with those risk factors and with outcomes (confounders), and pre-specified treatment effects. Thereby, we were able to create an external model with optimal validity (i.e. the model that would result from a large unbiased sample of the parent population) to estimate baseline risk for each scenario. Next, we repeatedly randomly sampled, with replacement, from each of the four parent populations to determine the statistical power and potential estimation biases of examining risk-stratified HTE in trials of varying sizes if we used a IWT model to predict baseline risk, vs. a ICO model vs. an optimized valid external model.

We chose a simulation approach for this analysis instead of estimating these effects in an actual trial because of the intrinsic challenge of determining “ground truth” when application of different models arrive at discordant conclusions. Given that this simulation approach requires some assumptions, we also applied a similar analytic approach to an actual trial where a widely used external risk model could be compared to an internal model. Specifically, we compared the Framingham risk score18 (external model) to internal models in the Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial (LRC-CPPT)19— to determine if a widely different interpretation may arise thereby calling into question simulation assumptions. (Appendix 1) The LRC-CPPT analysis plan was reviewed and approved by the Tufts Institutional Review Board. The authors had complete access to all LRC-CPPT trial data.

Simulated Treatment Scenarios/Patient Populations

Treatment scenarios were conceptually formulated as medication-based cardiovascular disease prevention trials. In all of the scenarios, patients were at risk for cardiovascular events and the magnitude of this risk could be predicted based on the presence or absence of six specific binary risk factors. These risk factors independently predicted cardiovascular events with odds ratios between 1.5 and 3.0, approximating the associations for binary variable in commonly used risk prediction models, 18,20 for each of the 200,000 simulated patients in each of the parent populations. Treated patients had a fixed low risk of competing treatment-related adverse outcomes that was independent of all risk factors. Finally, 6 additional variables designed to simulate potential confounders were generated which had variable correlations with both the “true” risk factors as well as with the cardiovascular outcomes.

The four treatment scenarios were differentiated based on the pre-specified treatment effects. Two different types of treatment effects were specified. First, there was a mean overall treatment effect — whether the treatment group had, on the whole, favorable outcomes compared to the control group. This effect represented the standard definition of whether a trial is positive. Second, we specified HTE — varying treatment benefit based on baseline risk. The four treatment scenarios explored different combinations of these treatment effects, Table 1. Treatment scenario populations were developed using previously described methods based on Monte Carlo Simulation.5

Table 1.

Description of treatment effects in 4 different treatment scenarios

| Heterogeneity of Treatment Effect (HTE) | No HTE | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Treatment Effect | Scenario 1 | Scenario 4 |

| No mean Treatment Effect | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 |

Trial Simulations

Individual trials, and their results, were simulated by repeated random draws with replacement from each scenario’s large parent population. In the base case, we drew 3,000 intervention subjects and 3,000 control subjects for each of the 4 scenarios. This sample size was selected for two reasons. First, it represented a well-powered study for detecting a main absolute outcome difference of 1.5% between the control and treatment arms. Second, it conformed to an oft-cited heuristic for adequate sample size to enable development of an ICO model without significant over-fitting as it included about 10 events per predictor variable (EPV)21 in the control arm. For each treatment scenario, we performed 1,000 simulated trials and analyzed each trial for the treatment’s main effect and its interaction with baseline risk using treatment outcome models developed in each trial.

Model Development

Prior to performing the simulated trials, we developed an optimized valid external baseline risk model for the large parent population using only the 6 true risk factors in each of the treatment scenario populations using logistic regression. Results using this external model serve as the “gold standard” for comparison against results generating using the internal models. Then, within each of the simulated trials we used logistic regression to develop ICO and IWT baseline risk models predicting cardiovascular outcomes using both the 6 true risk factors as well as the 6 confounders as predictor variables. The ICO model was derived on the control trial population only, while the IWT model was derived on the whole trial — both the control and treatment arms. For each subject in each simulated trial, we were then able to develop separate risk estimates from each of the three models: external, IWT, and ICO.

Estimating Treated and Untreated Outcomes

Mean treatment effect and HTE and were evaluated using logistic regression including 3 terms: predicted risk from the baseline risk model (IWT, ICO, external), a treatment indicator variable and an interaction between treatment and baseline risk. The treatment indicator coefficient measures whether, and to what extent, a constant relative risk reduction exists across the risk spectrum while the treatment-baseline risk interaction term measures whether differential treatment benefit exists on part of the risk spectrum. (e.g. higher relative risk reduction in high risk patients vs. low risk patients). These models enabled estimation of the individual’s risk of the overall outcome with and without treatment for each of the three baseline risk models. For analyses that compare regression coefficients, baseline risk information was included in each treatment model using the percentile rank of risk from each baseline risk model to standardize baseline risks across models. Without such standardization, baseline risk would be systematically lower or higher for the IWT group compared to the external and ICO models, depending on the direction of treatment effect.

Estimating Model Bias & Statistical Power

Bias was estimated for each of the 5 trial scenarios using all three models using three separate approaches. First, the proportion of cases where the internal model outcome risk confidence interval included the optimized valid external point estimate was tabulated. Second, the average point estimate was estimated for each model type over each risk decile and compared to the estimated actual risk reduction (untreated risk – treated risk) across the series of simulated trials. Finally, the treatment and HTE regression coefficients and degree of confidence interval coverage of the internal models were compared with the external model.

Power was estimated by the percentage of statistically significant main effects and interaction effects, when these effects were present in the parent population. Sensitivity, specificity and inter-model reliability using Cohen’s kappa were estimated by comparing the classifications of both coefficients of the ICO and IWT models to those using the optimized valid external model.

Sensitivity to Overfitting

Our base case trial scenarios were designed so that the ratio of events to predictor variables (EPV) included in the model was slightly greater than 1:10 to limit bias due to over-fitting.21 In real world scenarios, it may be the case that there are a large number of potentially important predictors or a relatively small number of outcomes and thus that the models will be more susceptible to overfitting. To test how ICO and IWT models perform in these contexts we setup a separate series of trials by varying the number of patients to adjust the EPV from 5 to 15.

Results

Predictiveness of Baseline Risk Models

The predictiveness of the three baseline risk models is displayed in Table 2. As expected, the IWT and ICO models were slightly more predictive of outcomes in the simulated trials than was the external model when less than 10 predictor variables per outcome were included. This increased predictiveness, however, is merely an indication of modest over-fitting in the IWT and ICO models, since the external model represents an optimized valid model and predictiveness for both IWT and ICO models decreased as over-fitting was reduced.

Table 2. Model Predictiveness.

For each of the three models, the predictiveness of the baseline risk prediction model (predicting cardiovascular outcomes in the trial) is displayed. The 90th percentile confidence intervals are displayed in parentheses for all models except for the external risk prediction models as there was only one external risk prediction model for each treatment scenario.

| IWT (90% CI) | ICO (90% CI) | External (90% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes Per Predictor | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | |

| Mean Treatment Effect Present | |||||||

| Scenario 1: Mean Treatment effect + HTE | 0.75 (0.70 - 0.79) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.77) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.76) | 0.76 (0.70 - 0.81) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.78) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.77) | 0.73 |

| Scenario 4: Mean effect + no HTE | 0.73 (0.69 - 0.77) | 0.72 (0.69 - 0.75) | 0.72 (0.69 - 0.74) | 0.73 (0.68 - 0.79) | 0.72 (0.68 - 0.75) | 0.72 (0.68 - 0.75) | 0.71 |

| No Mean Treatment Effect | |||||||

| Scenario 2: No mean effect + HTE | 0.75 (0.71 - 0.79) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.77) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.76) | 0.76 (0.70 - 0.81) | 0.75 (0.71 - 0.78) | 0.74 (0.71 - 0.77) | 0.74 |

| Scenario 3: No mean effect or HTE | 0.73 (0.69 - 0.77) | 0.73 (0.70 - 0.75) | 0.72 (0.70 - 0.75) | 0.74 (0.69 - 0.80) | 0.73 (0.69 - 0.76) | 0.73 (0.69 - 0.76) | 0.72 |

Model Bias — Treatment Effect Comparisons across Model Types

In the basecase, which had 10 control events per predictor variable (EPV), we found minimal bias in treatment outcome risk predictions when comparing the true treatment effects (those found using an optimized valid external model) compared to either internal model. The confidence intervals for point estimates from both internal models included the treatment outcome predicted by the external model models for every treatment scenario in nearly all cases — at least 99.7% of ICO and 99.9% of IWT outcome risk predictions included the external risk point estimate within their confidence intervals.

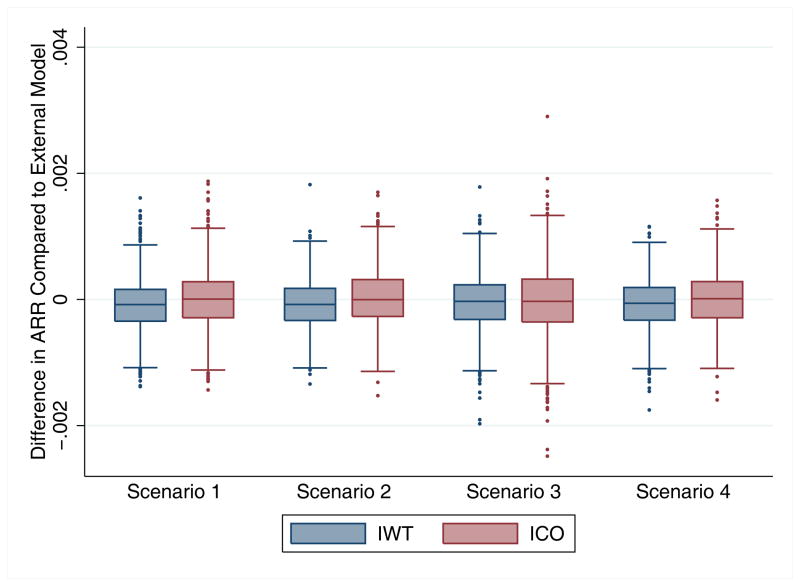

Both ICO and IWT models produced, on average, minimal bias in the estimation of the mean treatment effect compared to the optimal valid external model. The distribution of mean IWT biases was slightly narrower than the distribution of mean ICO biases and these results over 1,000 simulations are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean Bias in Treatment Effect. Box plot representing the distribution of mean treatment effect bias (difference in predicted absolute risk reduction (ARR)) from the IWT and ICO models compared to the external model. The box represents the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles

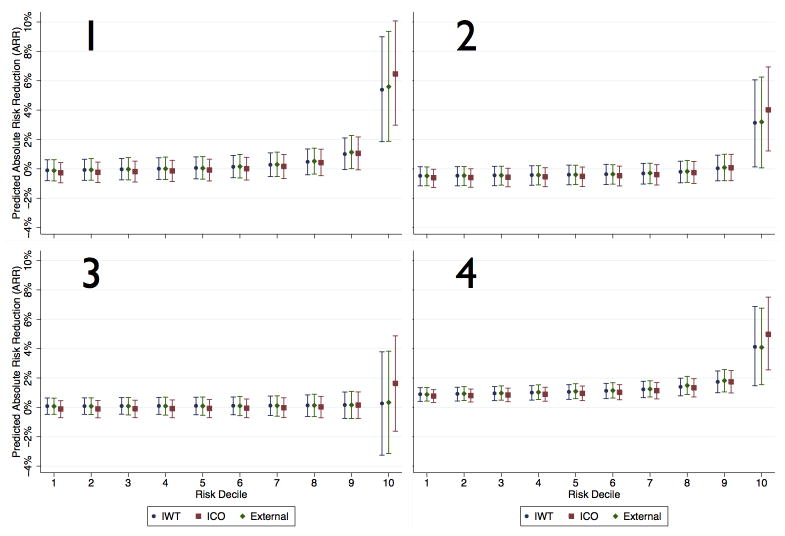

The minimally biased predicted treatment effects of IWT and ICO models holds across the risk spectrum — neither IWT nor ICO models result in substantial bias in either high or low risk patients regardless of treatment status or the presence/absence of HTE. IWT models predicted a fairly similar treatment effect size across the risk spectrum compared to external models. Conversely, ICO models tended to slightly under-predict treatment effect in lower risk patients and over-predict treatment effect size in the highest risk patients. This effect is due to the model fit being better in the control group, potentially inducing a spurious risk-by-treatment interaction. However, the magnitude of both effects is modest in our simulations. (Figure 2) Bias was further quantified by comparing the regression treatment-risk interaction and treatment indicator coefficients from the internal treatment outcome models to the external models and results are summarized in Appendix 2.

Figure 2.

Estimated treatment effects (ARR) across the spectrum of baseline risk. Each sub-figure represents the outcome/risk distribution for the 4 treatment scenarios for each of the three types of models. Estimated treatment effects are on the y-axis and the decile of baseline risk on the X-axis. Error bars signify 95% confidence intervals across the series of simulated trials.

Model Power

Because the overall treatment effect and HTE were specified in each of our treatment scenarios, we were able to determine how often the three modeling approaches correctly identified significant treatment indicator variables and treatment-interaction effects over 1,000 simulated trials in. Both IWT and ICO models had excellent agreement with external models on the treatment indicator variables (all kappa values > 0.80). Conversely, ICO models had higher sensitivity (i.e., a lower false negative rate) but at a cost of a higher false positive rate (i.e., finding a significant effect when their was no HTE). For example, the false negative rate in Scenario 1, in which HTE was present, was only 25.3% by ICO vs. 47.3% by IWT, but in Scenario 3, in which there was no HTE, ICO models had a false positive HTE of 14% compared to 5.4% for IWT models. (Table 3)

Table 3. Power Estimates.

For all three models, the number of trials (out of 1,000) in which the treatment and HTE coefficients were statistically significant. For the ICO and IWT models, the categorization of significant coefficients is compared to external models using sensitivity, specificity and kappa.

| Treatment Scenario | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| External Model | Treatment Coefficient | Significant N(%) | 312 | 49 | 53 | 979 |

| HTE Coefficient | Significant N(%) | 529 | 494 | 55 | 42 | |

| Internal Model – Whole Trial (IWT) | HTE Coefficient | Significant N(%) | 526 | 491 | 54 | 71 |

| Sensitivity vs. External | 89.04% | 85.83% | 63.64% | 54.76% | ||

| Specificity vs. External | 88.32% | 86.76% | 97.99% | 94.98% | ||

| Kappa vs. External | 0.7733 | 0.7259 | 0.6216 | 0.374 | ||

| Internal Model – Controls Only (ICO) | HTE Coefficient | Significant N(%) | 747 | 733 | 140 | 128 |

| Sensitivity vs. External | 98.87% | 97.98% | 61.82% | 52.38% | ||

| Specificity vs. External | 52.44% | 50.79% | 88.78% | 88.92% | ||

| Kappa vs. External | 0.5264 | 0.4849 | 0.2929 | 0.2087 | ||

Sensitivity to Overfitting

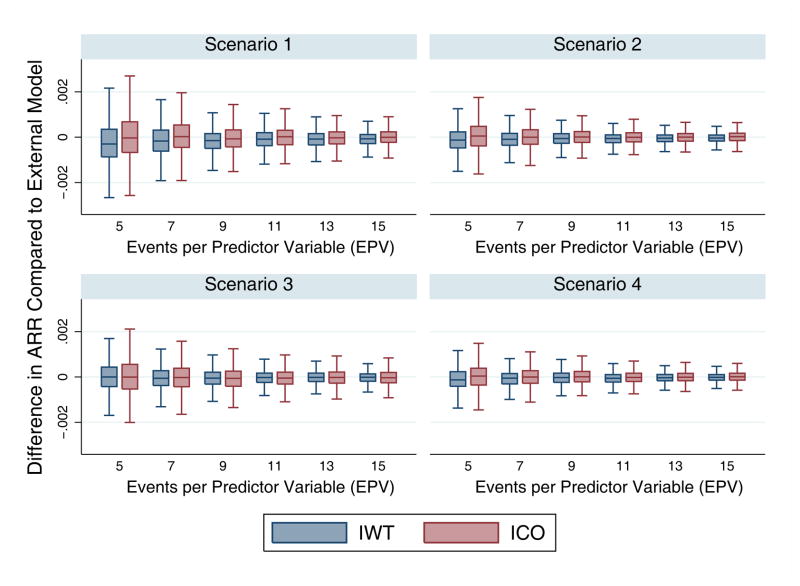

Risk of over-fitting is an intrinsic weakness of ICO models compared to IWT models, given that they are derived on a smaller population. Potentially more important, differential fitting between treatment arms might induce or exaggerate HTE compared to an IWT model developed “blinded” to treatment. To explore the magnitude of these effects, we built IWT and ICO models with varying degrees of over-fitting, ranging from highly overfit models (5 EPV) to relatively conservative models (15 EPV). For both models the distribution of treatment effect bias was more tightly distributed around zero as the EPV increased. For all scenarios and for a given EPV, there was a slightly wider distribution of bias in ICO models than in IWT models, Figure 3. As anticipated, the direction of this bias tended to exaggerate HTE, with more benefit seen in higher risk patients due to increased risk heterogeneity in the control arm.

Figure 3.

Change in Mean Treatment Effect Bias with change in Overfitting. The x-axis represents the number of events per predictor variable (EPV), and thus the left side of the x-axis represents the most overfit models and the right side the least overfit models. The y-axis represents the mean treatment effect bias (difference in absolute risk reduction) from the IWT and ICO models compared to the external model.

Discussion

This study has two key findings. First, we found that when internal models are developed appropriately (having at least 10 control group EPV) they produced relatively unbiased estimates of treatment effect across the spectrum of baseline risk. Second, we found that IWT models should, in general, be preferred to ICO models as they offer narrower distribution of treatment-effect biases, slightly less sensitivity to over-fitting and less susceptibility to false positive identification of HTE.

Under a range of treatment effect scenarios, both ICO and IWT models arrived at similar estimates of the study population’s heterogeneity of baseline risk and how the relative and absolute treatment effect varied as a function of baseline risk (risk-based heterogeneity of the treatment effect [HTE]), just as long as model development considered no more than 1 risk factor for every 10 outcomes present in the control group (10 EPV). This implies that development of internal models is a practical strategy to test for HTE. This has the potential to greatly increase the degree to which clinical trial results can be used to better inform individual patient treatment decisions in instances in which external risk models do not already exist for a study’s outcome measure. We would still argue that when valid externally-developed prediction tools are available, their use should be preferred, not because of greater internal validity but because the use of an external tool is a better test of the external validity of HTE results, likely offers superior calibration, and permits easier translation into practice through a variety of techniques.10,22 In particular, to make risk-based treatment decisions, it is essential that the risk model is well-calibrated to the target population. Given the differences between patients that enroll in trials and patients in the broader population,23 this an important limitation of directly applying internal risk models to the broader target population. Consequently, if clinically-important HTE is discovered with an internally-developed model, that should motivate the more difficult step of developing and validating an appropriate risk model for clinical translation.

When developing internal models, this study suggests that IWT models should be favored over ICO models. This finding was mainly due to IWT models being insensitive to overfitting, whereas over-fitting ICO models differentially across study arms leads to more bias in the magnitude of risk-based HTE. Further, even in the absence of over-fitting, ICO models are intrinsically more susceptible to falsely identifying risk-base HTE when none exists due to an under-estimation of the true standard error.

In addition, this study illustrates the importance of avoiding over-fitting by ensuring that an adequate number of events per variable included in the baseline risk model. We observed an increase in bias in both IWT and ICO models as EPV decreased. Our data suggest that applying the conventional rule of thumb (at least 10 predictor variables for each binary outcome in the dataset), results in the introduction of minimal bias into treatment effect estimates across the spectrum of baseline risk, although this should ideally be tested in other scenarios. Although this might create a problem in some small studies or studies with a small number of outcomes, for most clinical trials following this rule of thumb will merely require only considering risk factors for which there is strong empirical or theoretical reasons to suspect that they are substantially associated with the risk of the outcome.

This study is limited by the assumptions of our simulation environment. While this study explored a wide variety of treatment effects, in order to maintain a comprehensible degree of complexity we made some potentially limiting assumptions in setting up our treatment scenarios. Most notably, we modeled a disease-treatment context with relatively low outcome risk, relying on moderately predictive models in the context of moderate degrees of confounding and assuming a constant risk of baseline adverse effects. While assuming a constant absolute risk of adverse effects across patients at different outcome risks may seem like a substantive limitation, it is a commonly applied assumption24,25 and studies that have modeled differential risks of benefits and harms have not found substantial divergence.26,27 Regardless, when modeling actual trials the possibility of differential harms across risk strata should be explicitly explored empirically. While it is uncertain whether our conclusions would hold under differing assumptions, these parameters were chosen because they were felt to apply to a wide variety of real world clinical contexts.

While simulation studies require potentially limiting assumptions, those assumptions were necessary in this context because of the intrinsic challenges of studying this question using data from actual trials. If internal and external models applied to an actual trial were discordant it would be impossible to determine if that disagreement reflected limited calibration of the external model in the trial population or biases in the internal model. Thus, this study provides important evidence that using carefully developed internal models results in similar estimates of treatment effect size and similar estimates of how treatment effect varies as an effect of risk compared to optimized valid external models.

Internal models are powerful tools to estimate treatment effect across the risk spectrum. Since these models appear to introduce minimal bias compared to external models, they should have an important role in targeting cardiovascular treatments to appropriate treatment populations when external models are not available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared using LRC-CPPT Research Materials obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the LRC-CPPT or the NHLBI. The authors would also thank Tim Hofer for his assistance in developing the code to develop the simulated populations.

Funding Sources

Funded by a PCORI Methodology Grant. Dr. Burke was funded by an Advanced Fellowship from the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and by NINDS grant number 1K08NS082597.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

James F Burke, Email: jamesbur@umich.edu.

Rodney A Hayward, Email: rhayward@med.umich.edu.

Jason P Nelson, Email: JNelson2@tuftsmedicalcenter.org.

David M Kent, Email: dkent1@tuftsmedicalcenter.org.

References

- 1.Kent DM, Hayward RA, Griffith JL, Vijan S, Beshansky JR, Califf RM, Selker HP. An independently derived and validated predictive model for selecting patients with myocardial infarction who are likely to benefit from tissue plasminogen activator compared with streptokinase. Am J Med. 2002;113:104–111. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kent DM, Hayward RA. Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients: the need for risk stratification. JAMA. 2007;298:1209–1212. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Prediction of benefit from carotid endarterectomy in individual patients: a risk-modelling study. European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1999;353:2105–2110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov S, Warlow C, Barnett H. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet. 2004;363:915–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15785-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP. Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CNB, Brewer HB, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Stone NJ National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson J. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2008;94:1331–1332. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker RC, Meade TW, Berger PB, Ezekowitz M, O’Connor CM, Vorchheimer DA, Guyatt GH, Mark DB, Harrington RA American College of Chest Physicians. The primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133:776S–814S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu T, Vollenweider D, Varadhan R, Li T, Boyd C, Puhan MA. Support of personalized medicine through risk-stratified treatment recommendations - an environmental scan of clinical practice guidelines. BMC medicine. 2013;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JPA, Altman DG, Hayward RA. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials. 2010;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Follmann DA, Proschan MA. A multivariate test of interaction for use in clinical trials. Biometrics. 1999;55:1151–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovalchik SA, Varadhan R, Weiss CO. Assessing heterogeneity of treatment effect in a clinical trial with the proportional interactions model. Statist Med. 2013;32:4906–4923. doi: 10.1002/sim.5881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell PM. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothwell PM, Mehta Z, Howard SC, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP. From subgroups to individuals: general principles and the example of carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2005;365:256–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent DM, Ruthazer R, Griffith JL, Beshansky JR, Concannon TW, Aversano T, Grines CL, Zalenski RJ, Selker HP. A Percutaneous Coronary Intervention–Thrombolytic Predictive Instrument to Assist Choosing Between Immediate Thrombolytic Therapy Versus Delayed Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:790–795. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kent D, Selker H, Ruthazer R, Bluhmki E. The stroke-thrombolytic predictive instrument: a predictive instrument for intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006 doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000249054.96644.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorresteijn JAN, Visseren FLJ, Ridker PM, Wassink AMJ, Paynter NP, Steyerberg EW, van der Graaf Y, Cook NR. Estimating treatment effects for individual patients based on the results of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5888. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease Using Risk Factor Categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Lipid Research Clinics Investigators. The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial. Results of 6 years of post-trial follow-up. JAMA. 1984;251:351–364. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03340270029025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano JM, Cook NR. C-Reactive Protein and Parental History Improve Global Cardiovascular Risk Prediction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Fonseca FAH, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJP, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ JUPITER Study Group. Number needed to treat with rosuvastatin to prevent first cardiovascular events and death among men and women with low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: justification for the use of statins in prevention: an intervention trial evaluating rosuvastatin (JUPITER) Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:616–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.848473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorresteijn JAN, Boekholdt SM, van der Graaf Y, Kastelein JJP, LaRosa JC, Pedersen TR, DeMicco DA, Ridker PM, Cook NR, Visseren FLJ. High-Dose Statin Therapy in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2013;127:2485–2493. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorresteijn JAN, Visseren FLJ, Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Wassink AMJ, Buring JE, van der Graaf Y, Cook NR. Aspirin for primary prevention of vascular events in women: individualized prediction of treatment effects. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2962–2969. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sussman JB, Vijan S, Choi H, Hayward RA. Individual and Population Benefits of Daily Aspirin Therapy: A Proposal for Personalizing National Guidelines. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:268–275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiteley WN, Adams HP, Jr, Bath PM, Berge E, Sandset PM, Dennis M, Murray GD, Wong KSL, MDPAS Targeted use of heparin, heparinoids, or low-molecular-weight heparin to improve outcome after acute ischaemic stroke: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.