Abstract

This study examined the feasibility of using home telehealth monitoring to improve clinical care and promote symptom self-management among veterans with multiple sclerosis (MS). This was a longitudinal cohort study linking mailed survey data at baseline and 6-month follow-up with information from home telehealth monitors. The study was conducted in two large Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) MS clinics in Seattle, Washington, and Washington, DC, and involved 41 veterans with MS. The measures were demographic information and data from a standardized question set using a home telehealth monitor. Participants reported moderate levels of disability (median Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS] score, 6.5) and substantial distance from the nearest VA MS clinic (mean distance, 93.6 miles). Of the participants, 61.0% reported current use of MS disease-modifying treatments. A total of 85.4% of participants provided consistent data from home monitoring. Overall satisfaction with home telehealth monitoring was high, with 87.5% of participants rating their experience as good or better. The most frequently reported symptoms at month 1 were fatigue (95.1%), depression (78.0%), and pain (70.7%). All symptoms were reported less frequently by month 6, with the greatest reduction in depression (change of 23.2 percentage points), although these changes were not statistically significant. Home telehealth monitoring is a promising tool for the management of chronic disease, although substantial practical barriers to efficient implementation remain.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disorder of the central nervous system that has been estimated to affect as many as 400,000 people in the United States and 2.1 million people worldwide.1 It typically includes acute exacerbations and remissions, with progression of disability over time. It is characterized by a heterogeneous array of symptoms that vary considerably from person to person, including sensory and motor deficits, fatigue, pain, cognitive impairment, depression, and difficulties with both bowel and bladder function.2–4 The disease is typically diagnosed in early adulthood and is associated with a relatively normal lifespan. As a result, individuals often face the challenge of extended illness with significant clinical morbidity.

The Wagner Model of Chronic Illness Care represents one paradigm for providing care to individuals with MS. The Wagner Model proposes that traditional outpatient models of acute care are inadequate for the management of chronic diseases, and that the provision of care should be redesigned at a systems level and be realigned according to the longer-term needs of specific patient populations.5 The challenges of a chronic illness are often well known to providers and their patients. Instead of discrete episodes of care, focused on diagnosis and brief intervention, care of individuals with MS requires ongoing management and coordination. Interventions may take many forms—including patient education, medication and symptom monitoring, and self-management support—to address aspects of the illness (eg, fatigue) as well as proactive self-care (eg, medication adherence).6 The ultimate goal is to establish an ongoing relationship between an informed and active patient and a prepared and proactive team.7

One essential underpinning of the Wagner Model is the use of clinical information systems to support disease monitoring and care coordination.6 Home telehealth monitoring is an important component of a clinical information infrastructure that is well suited to this purpose. Home telehealth monitoring can be used to ask individuals with MS about their disease process and the development and impact of new symptoms, as well as inquire about health behaviors that promote effective self-management. Telehealth counseling in general has been shown to be an effective means of promoting positive health behaviors, reducing the impact of secondary conditions across a variety of populations with disabling illnesses, including MS.8

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been a leader in the development and use of multiple telehealth modalities in the past decade (eg, home telehealth monitoring, clinical video teleconferencing) and is currently expanding telehealth programs and integrating them with the electronic medical record.9 In 2003, the VA introduced a national home telehealth program,10 and as of fiscal year 2010 over 46,000 patients had been enrolled.11 Telehealth is an important tool for the VA Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence (MSCoE), where many patients are separated from specialty clinics by distance and disability.12

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing a disease-management protocol delivered via a home telehealth program in the VA health-care system to support effective chronic illness management for individuals with MS. To do so, we examined rates of symptom reporting among individuals with MS, reductions in symptoms over the course of monitoring, and overall patient satisfaction with the telehealth experience.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two large VA MS clinics located in Seattle, Washington, and Washington, DC. Both clinics are multidisciplinary regional centers and part of the VA MS Center of Excellence network (www.va.gov/ms). To be included in the study, participants must have had a diagnosis of MS meeting the McDonald criteria13 and a landline telephone (necessary to make use of VA home telehealth technology). Individuals were excluded at the discretion of the MS treatment provider when they did not have cognitive, sensory, or motor capabilities allowing them to complete question sets or operate a home telehealth monitor. Participants were included in the final study sample if they completed a baseline questionnaire and participated in home monitoring for at least 1 month (N = 41). There were 21 veterans with MS recruited from the VA Medical Center (VAMC)–Seattle and 20 recruited from the VAMC–Washington, DC.

Procedures

This was an observational study examining a cohort of veterans with MS over 6 months. Upon confirmation of eligibility and acquisition of written informed consent, participants were enrolled in the VA Care Coordination and Home Telehealth program (CCHT) and were issued a Viterion 100 home-based telehealth monitor (Viterion TeleHealthcare, Tarrytown, NY). The monitor operated over a traditional analog telephone line using a text-based interface. The Viterion system fully complies with governmental regulations on data transmission and security. Participants were asked to respond to a standardized set of questions addressing common MS-related symptoms (described below) once per week. Responses from this disease-management protocol were forwarded to a secure web portal that could display data graphically and stratify them by importance (eg, low fatigue, moderate fatigue, extreme fatigue). Responses were monitored by a care coordinator who alerted treating providers about the presence of significant symptoms.

Demographic data and clinical data were collected at baseline at both facilities and through an additional survey at VA Puget Sound. Satisfaction data were also collected at 6-month follow-up at VA Puget Sound. All study procedures were approved by the VA human subjects committees at each study site.

Measures

MS Disease-Management Protocol

The presence of MS-related symptoms was determined by a standardized question set addressing eight core symptom areas: neurologic symptoms, pain, fatigue, bladder function, bowel function, depression, adherence to MS disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), and side effects of DMTs. The question set was developed through an interactive and iterative process between veterans with MS and VA MS Center of Excellence staff. Questions within each core area were based on branching logic, such that responses to initial questions dictated whether additional questions were asked (eg, individuals who responded that they were not taking an MS DMT did not then receive the questions about adherence or side effects). Participants received between 8 and 33 questions weekly, depending on their responses. Responses across core areas were summarized and dichotomized to reflect the presence or absence of a symptom (eg, new neurologic problem, pain, fatigue) during each recording week. Responses were further collapsed to report the presence or absence of a symptom during each of the 6 months of study participation.

Demographic Information

Age, gender, race, marital status, employment, years since diagnosis of MS, primary means of transportation to VA appointments, number of miles to the VA medical center where MS care was received, and travel time to that same medical center were collected from the medical record or survey data at baseline for all participants.

Clinical Information

Information on disease subtype, disability, and DMT use was obtained at baseline. MS disease subtype was collected from the medical record. MS-related disability was categorized according to the criteria established by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) at baseline.14 The EDSS uses information typically obtained from neurologic examination to categorize functioning along a scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (death) in half-point increments. A patient self-report version of this instrument is also available that demonstrates good agreement with examination-based ratings.15 The examination-based rating was used in Washington, DC. The self-report–based rating was used in Seattle. Finally, information on current use of a DMT for MS was collected and included the following: interferon beta-1a (Avonex), interferon beta-1a (Rebif), interferon beta-1b (Betaseron), or glatiramer acetate (Copaxone).

Satisfaction with Telehealth Monitoring

Satisfaction with telehealth monitoring was assessed with seven individual questions addressing ease of use, reliability, and satisfaction with use. Ease of use questions included the phrases “home telehealth is easy to understand” and “home telehealth is easy to use,” and reliability questions included the phrases “home telehealth works as it is supposed to” and “home telehealth works when I need it.” Individuals were asked to rate these statements using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Answers were dichotomized into responses reflecting “agree” and “strongly agree” versus all others. Satisfaction was examined with the questions “How did you like using the health monitor?” (with responses ranging from “poor” to “excellent”), “Do you think this monitor improved your MS care?” (yes or no), and, finally, “If you had the choice, would you rather use the home telehealth monitor than go to an appointment at the MS clinic?” (yes or no).

Data Analysis

Participant characteristics at baseline were examined using percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Responses to questions from the disease-management protocol were categorized in two ways. First, responses were tabulated to identify the number of individuals who reported symptoms in each cluster at any level of severity. Second, responses were tabulated to identify the reporting of symptoms in each cluster at the highest level of severity. The frequency of item reporting using these two different cut points was summarized with proportions. Similarly, responses to the satisfaction survey were examined using frequency counts and percentages. Changes in the proportion of individuals reporting each symptom between month 1 and month 6 were examined using the McNemar test for dependent proportions.

Results

Participant Characteristics

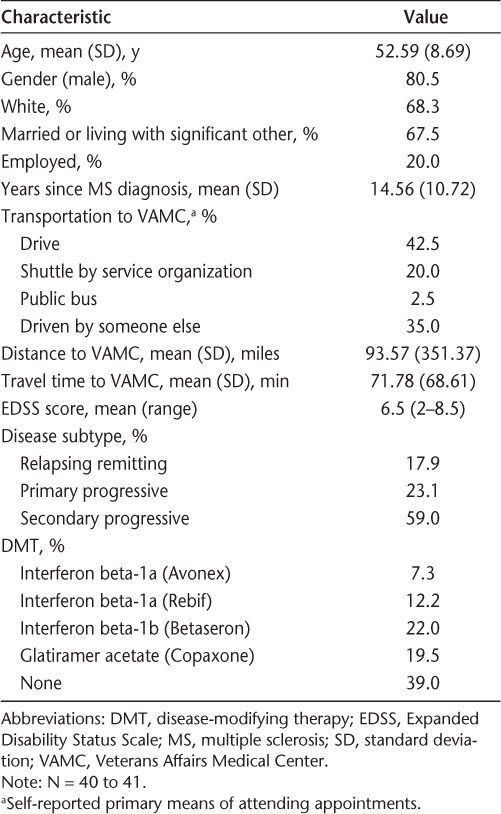

The mean age of participants was 52.6 years, and the average number of years since diagnosis with MS was 14.6. The majority of participants were male, white, and either married or living with a significant other. Only one-fifth were employed. Over half (59.0%) had been diagnosed with secondary progressive MS. The median EDSS score was 6.5 (range, 2.0–8.5), reflecting a wide range of disability but suggesting that, on average, individuals needed bilateral assistance to ambulate short distances. Over half (61.0%) were currently receiving a DMT. The primary method of transportation to VA medical appointments was either driving or being driven by someone else. The average distance to a VA medical center was over 90 miles, and the average travel time was over 1 hour, although time and distance were often considerably greater in some rural areas. Demographic characteristics of the study sample are shown in greater detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

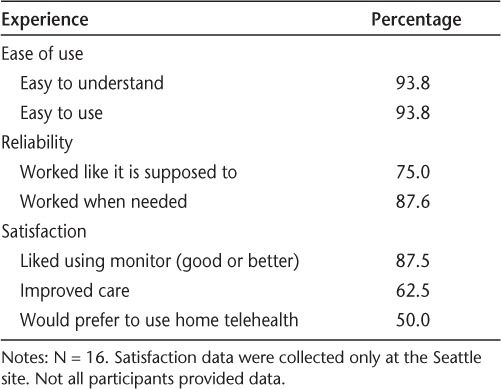

Participant Experiences with Telehealth Monitoring

Overall, 65.9% of participants provided self-reported symptom data across all 6 months of study monitoring, and 85.4% provided data for 5 of the 6 months. In general, participants reported few difficulties using home telehealth monitors. Over 90% of individuals stated that they were both easy to understand and easy to use. With respect to reliability, 75% or greater noted that the monitor worked “like it was supposed to” and “when needed.” Satisfaction ratings were generally high, with 87.5% rating the experience good or better, 62.5% feeling that the monitor improved their care, and 50.0% preferring the monitor to an in-person clinic visit. Additional information on participant experiences is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Telehealth experiences

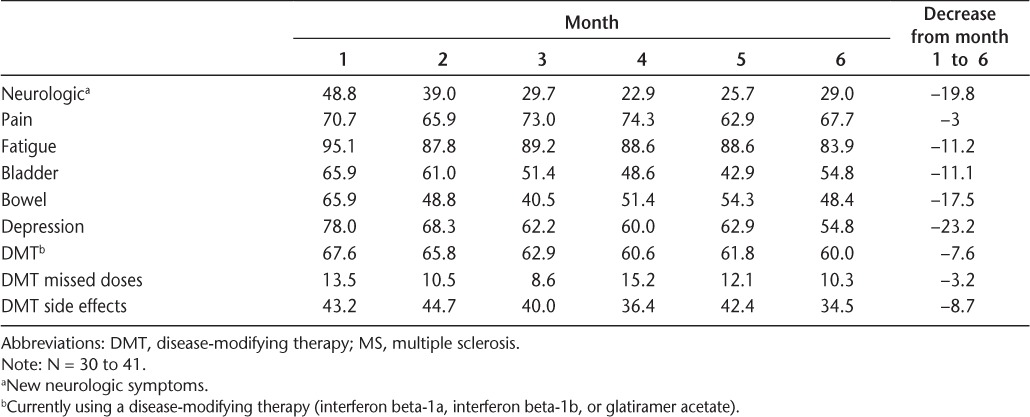

Reporting of Symptoms During Telehealth Monitoring

Based on the six questions reflecting MS-related symptoms, the most frequently reported symptoms at month 1 were fatigue (95.1%), depression (78.0%), and pain (70.7%). These symptoms were also reported at follow-up, with rates of 83.9% for fatigue, 54.8% for depression, and 67.7% for pain. Approximately two-thirds of individuals were receiving DMTs during the study period. Additional information on symptom reporting and the use of DMTs over the study period can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentages of individuals reporting MS-related monitoring items

Change in Symptoms During Telehealth Monitoring

Overall, the frequency with which MS-related symptoms were reported declined over the course of the study period. The greatest decline in the frequency of reporting was seen in depression (change of 23.2 percentage points), followed by neurologic symptoms (19.8), bowel symptoms (17.5), and fatigue (11.2). The proportions of individuals who reported pain and missed doses of the DMT were fairly stable over the study period (decline of approximately 3 percentage points). Despite what were in some cases substantial reductions in the reporting of symptom and medication items from month 1 to month 6, none of these reductions was statistically significant, owing in large part to the modest sample size of the study. Additional information can be found in Table 3.

Discussion

Feasibility of Home Monitoring in MS Care

This study presents the results of a home telehealth demonstration project intended to collect and transmit relevant data from individuals with MS receiving care in the VA health-care system. Overall, participants in the project maintained active engagement in the process of symptom monitoring and rated their experiences with telehealth monitoring favorably. Over 85% provided data for 5 of the 6 study months and reported that they were satisfied with the experience. Half preferred the monitor to an in-person clinic visit. The findings suggest that telehealth monitoring for MS symptom management is both feasible and acceptable to those who use it.

The only other study to objectively evaluate home telehealth clinical monitoring of patients with MS was by Zissman et al.16 In their study of 40 patients with MS over 6 months, a telehealth tool was implemented in the intervention group. As in our study, there was high patient satisfaction with telehealth. Additionally, the group found a 35% reduction in costs for 67% of the telehealth sample.16

Using Telehealth Monitoring to Reduce Barriers to Care

Disease monitoring via telehealth represents a particularly promising mechanism for improving access to care.17 Over 50% of veterans with MS receiving VA health services live more than 1 hour away from their nearest medical center, and well over one-third live more than 2 hours away.18 Individuals who live farther away from medical centers and in more rural areas have greater barriers to receiving routine and recommended annual specialty care visits. Telehealth monitoring could serve to improve communication and facilitate the discussion between proactive patients and knowledgeable providers that is championed in the Wagner Model of Chronic Illness Care.

Reporting of MS-Related Symptoms

Participants reported many MS-related symptoms at a high rate, with two-thirds or more reporting fatigue, depression, and pain at the beginning and end of the home monitoring process. Rates of reporting for fatigue were generally in line with established literature for community samples,19 and rates for pain were similar to the upper range reported in existing studies,4,20 but rates for depression were higher than in other community samples21 and veteran samples using similar if not identical instruments.3,22,23 The results underscore that these symptoms are common and often persistent experiences for individuals with MS.

Reductions in the Reporting of Symptoms

The proportion of individuals who reported MS-related symptoms declined during the course of the study period for every individual symptom monitored. In some cases, as with depression, the reduction was substantial (from 78.0% to 54.8%); however, owing to the limited sample size, no symptom reduction was statistically significant. This finding is subject to some very important limitations (listed below) but nonetheless provides promising preliminary evidence that monitoring may be of direct value to patients in their chronic illness care over time. One explanation of these findings is that participation in a home telehealth program encouraged individuals to engage in a process of self-management of their chronic illness. Self-management has many definitions but is often described as performing the tasks required to live well with a chronic condition and includes managing symptoms, treating physical and psychosocial consequences, and engaging in lifestyle changes.24,25 One common element of self-management is self-monitoring.26 Future studies are necessary to confirm the hypothesis that symptom monitoring in itself prompted individuals to improve self-care.

Experiences with the Implementation of Telehealth Monitoring

The implementation of telehealth monitoring was associated with several benefits and barriers that are worthy of note. Study staff had little difficulty deploying in-home monitoring devices using established VA protocols, and participants largely found the in-home monitoring device to be easy to use. However, the home monitor's reliance on standard telephone lines meant that individuals without landlines (nearly one-quarter of US households and growing annually)27 were unable to benefit from the service. Also, the programming language of the units limited the ability to create question sets that were flexible in terms of the number, type, and frequency of questions asked. Additional flexibility would have many advantages, including reducing participant burden and better matching of clinical assessment to the needs of individual patients. For example, if pain was not reported on two consecutive occasions, a more adaptive question set could automatically taper the frequency of this question. Anecdotally, some study participants noted that the most negative aspect of monitoring was the repetition of questions perceived to be irrelevant or unchanging over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results of this study are subject to some important limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and it is unclear to what extent the results may be generalized to the larger population of veterans with MS or individuals with MS more globally. The psychometric properties of symptom monitoring via home telehealth technology have not been rigorously evaluated, and thus the validity and reliability of the assessment items remain to be established. The study sample reflected the experience of a single disease cohort, and there was no control group. Thus, reductions in symptom reporting over time might also have been influenced by normal time trends (eg, regression to the mean) or the effects of serial assessment. Similarly, the modest sample size limited the ability to stratify patients or to make statistical inferences about changes over time. This study did not evaluate the number and types of ancillary clinical services that were received as a result of monitoring (eg, clinic or telephone encounters with providers occurring as a result of symptom reporting during the study period).

This study also has notable strengths. Individuals were recruited at multiple study sites and followed longitudinally according to standardized protocols. Data on the feasibility and acceptability of telehealth monitoring were also collected across multiple modalities (eg, examination of actual self-monitoring behavior as well as self-reported experience with telehealth). Future studies would benefit from larger samples to strengthen generalizability. Monitoring periods should be longer to help establish what duration and pattern of assessment (focused and episodic or continuous) is most appropriate. Monitoring should include the quantification of clinical services received during the study period to examine the relationship between monitoring and health-care encounters. Finally, future studies should examine the relationship between monitoring, the concurrent and subsequent provision of services, meaningful patient-reported outcomes (eg, disease morbidity, quality of life), and health-care administrative outcomes (eg, fewer emergency department visits or inpatient hospitalizations).

PracticePoints

As with many chronic illnesses, the care of individuals with MS requires ongoing management and coordination.

Home telehealth monitoring is a promising practice to promote disease self-management among people with MS and to coordinate and adjust ongoing clinical services.

Implementation of telehealth monitoring is feasible, and patient satisfaction rates are high.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs MS Centers of Excellence West and East, and by a Rehabilitation Research and Development Service Career Development Award (B3319VA and B4927W) to Dr. Turner.

References

- 1.National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Multiple Sclerosis Information Sourcebook. New York, NY: Information Resource Center and Library of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson KJ. Quality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology. 1997;48:74–80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RM, Turner AP, Hatzakis M, Jr, Bowen JD, Rodriquez AA, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and correlates of depression among veterans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64:75–80. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000148480.31424.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsh AT, Turner AP, Ehde DM, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and impact of pain in multiple sclerosis: physical and psychologic contributors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorstyn DS, Mathias JL, Denson LA. Psychosocial outcomes of telephone-based counseling for adults with an acquired physical disability: a meta-analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0022249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chumbler NR, Haggstrom DA, Saleem J. Implementation of health information technology in Veterans Health Administration to support transformational change: telehealth and personal health records. Med Care. 2011;49(suppl):S36–S42. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d558f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darkins A, Ryan P, Kobb R. Care coordination/home telehealth: the systematic implementation of health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management to support the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:1118–1126. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0021. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Telehealth Quarterly. http://www.telehealth.va.gov/newsletter/2011/031711-Newsletter_Vol10Iss02.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2012.

- 12.Wallin MT. Integrated multiple sclerosis care: new approaches and paradigm shifts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:ix–xiv. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2010.03.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowen J, Gibbons L, Gianas A, Kraft GH. Self-administered Expanded Disability Status Scale with functional system scores correlates well with a physician-administered test. Mult Scler. 2001;7:201–206. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zissman K, Lejbkowicz I, Miller A. Telemedicine for multiple sclerosis patients: assessment using Health Value Compass. Mult Scler. 2012;18:472–480. doi: 10.1177/1352458511421918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatzakis M, Jr, Haselkorn J, Williams R, Turner A, Nichol P. Telemedicine and the delivery of health services to veterans with multiple sclerosis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:265–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Culpepper WJ, II, Cowper-Ripley D, Litt ER, McDowell TY, Hoffman PM. Using geographic information system tools to improve access to MS specialty care in Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:583–591. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.10.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupp LB. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: definition, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:225–234. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Overvad K, Hansen HJ, Koch-Henriksen N, Bach FW. Pain in patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1089–1094. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1862–1868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallin MT, Wilken JA, Turner AP, Williams RM, Kane R. Depression and multiple sclerosis: review of a lethal combination. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:45–62. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2004.09.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner AP, Williams RM, Bowen JD, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Suicidal ideation in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1073–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams K, Greiner AC, Corrigan JM, editors. Institute of Medicine 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plow MA, Finlayson M, Rezac M. A scoping review of self-management interventions for adults with multiple sclerosis. PM&R. 2011;3:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Ganesh N, Davern ME, Boudreaux MH, Soderberg K. Wireless substitution: state-level estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January 2007–June 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;39:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]