Abstract

Purpose

The incidence rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Korea have been increasing during the past decade. Therefore, it is important to understand the characteristics, including survival, of Korean CRC patients. The aim of this study was to use the nationwide cancer registry to evaluate the characteristics of Korean CRC, focusing on the survival, according to tumor location, sex, and specific age groups.

Methods

Using the Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR), we analyzed a total of 226,352 CRC cases diagnosed from 1993 to 2010. The five-year relative survivals were compared for the proximal colon, the distal colon, and the rectum. Survival rates were compared between men and women and between patients of young age (less than 40 years old) and patients of advanced age (70 years old or older).

Results

The 5-year survival rates were improved in all subsites between 1993 and 2010. Distal colon cancer showed favorable survival compared to proximal colon or rectal cancer. Females demonstrated worse survival for local or regional cancers, and this difference was significant in for patients in their seventies. Young patients (<40 years old) showed better survival rates for overall and proximal colon cancer comparable to those for older patients (≥40 years old), but advanced age patients (≥70 years old) had worse survivals for all tumor subsites compared to their younger counterparts (<70 years old). These trends were similar in distant CRC.

Conclusion

Korean CRC has certain distinct characteristics of survival according to tumor location, sex, and age. Despite the limitations of available data, this study contributes to a better understanding of survival differences in Korean CRC.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms; Korean, Survival

INTRODUCTION

As a result of the increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) since 1999, it has become the third most common cancer in Korea, with an age-standardized incidence rate of 36.9/100,000 in 2010 [1]. During the past decades, there have been many significant changes in the diagnosis and treatment of CRC, and these may lead to an improved prognosis in Korea. There have been several reports on the incidence of cancer and the survival of patients with cancer, including CRC [2-4]. However, those reports have not fully addressed the variations in the survival features according to tumor location, sex, specific age group, and stage. In addition, the significance of these factors for the survival was not assessed based on a nationwide database.

The Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) was initiated as a nation-wide, hospital-based cancer registry in Korea in 1980 and has covered the entire population since 1999. Under the national medical insurance system, this registry collects information mostly on cancer cases across the country. Thus, an analysis of this registry can be informative and provide an understanding of the features of CRC in Korea. The aim of this study was to use the KCCR data to evaluate the characteristics of Korean CRC, focusing on the variation in survival according to a specific age group, sex, or tumor location.

METHODS

Age, sex, tumor location, and stage were obtained from the Korea National Cancer Incidence Database (KNCI DB). This database between 1993 and 2010 was employed for the current analysis. The KCCR covered a total of 226,352 CRCs in this period.

We measured the 5-year relative survivals for the following time periods; 1993-1995, 1996-2000, 2001-2005, and 2006-2010. Anatomical subsites were defined as the proximal colon (from the cecum including appendix to the splenic flexure of the colon), the distal colon (from the descending colon to the sigmoid colon), and the rectum. The surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) stages (local, regional, distant, and unknown disease) could be accessed from 2005 to 2010. We used the 5-year relative survival rate (RSR), adjusted for the mortality expected among other peoples of the same age and sex. The RSR were calculated using the Ederer II method [5]. We also estimated survival differences by sex (male and female) and by age at diagnosis (39 years or younger, 40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and 70 years or older).

To describe characteristics of young-age cancer, we defined it as cancer that developed in a person under the age of forties, and we compared the survival for that group of patient with the survivals for other age groups. We also defined advanced-age cancer as a cancer that develops in a person older than seventies, and we compared the survival for that group with the survivals for other age groups. In addition, we examined survival differences between young-age and advanced-age cancer by using the distant disease (SEER stage) of CRC.

RESULTS

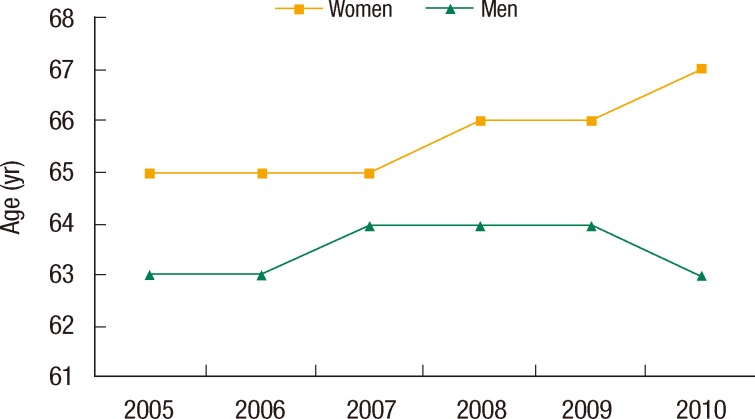

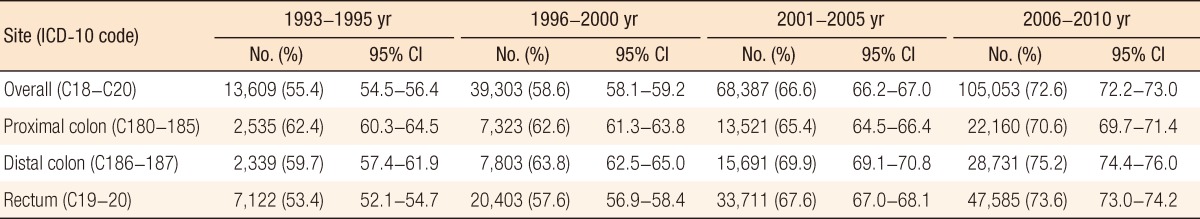

Table 1 shows the 5-year relative survivals for proximal colon, distal colon, and rectal cancers by time period. Survival has improved significantly for all tumor sites of CRC. Distal colon cancer showed the most favorable survival compared to proximal colon cancer or rectal cancer, except for the 1993-1995 period. This finding was reaffirmed by the survival analysis according to SEER stage (Table 2).

Table 1.

Five-year relative survival (%) by time period

ICD, international classification of disease; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

Five-year relative survival of colorectal cancer by tumor distribution according to SEER stage

SEER, surveillance epidemiology and end results; CI, confidence interval.

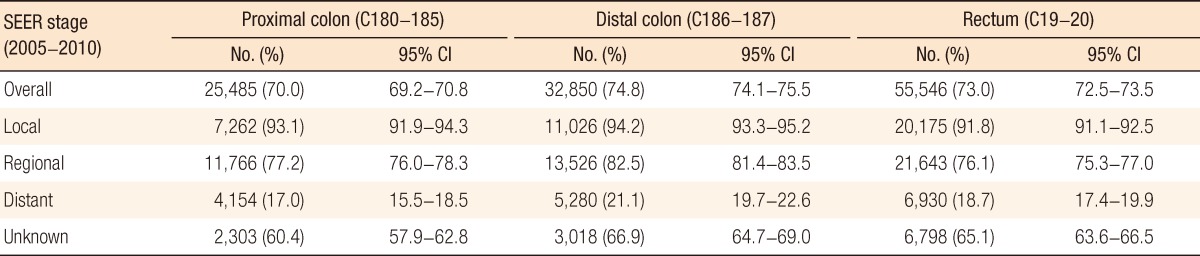

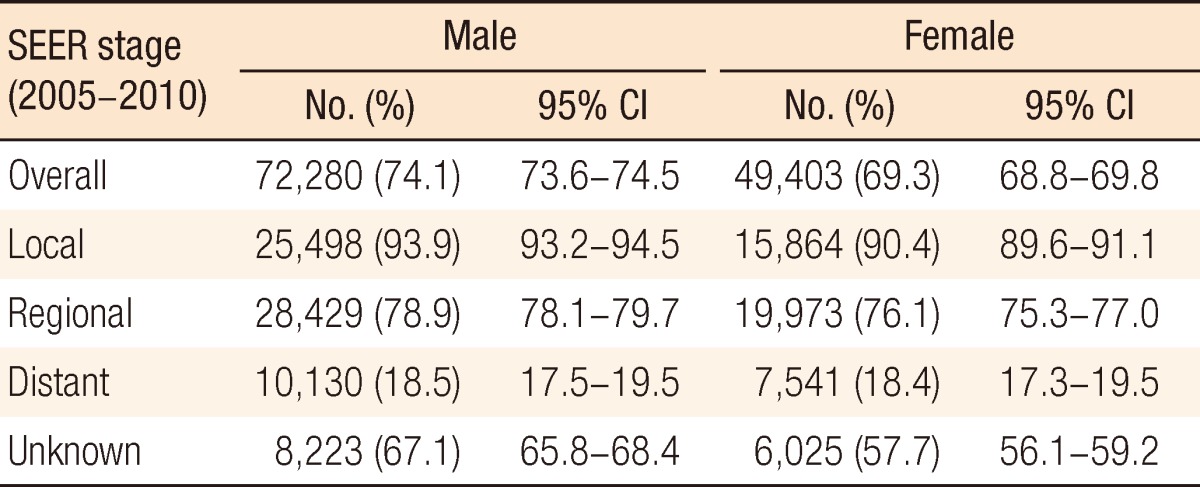

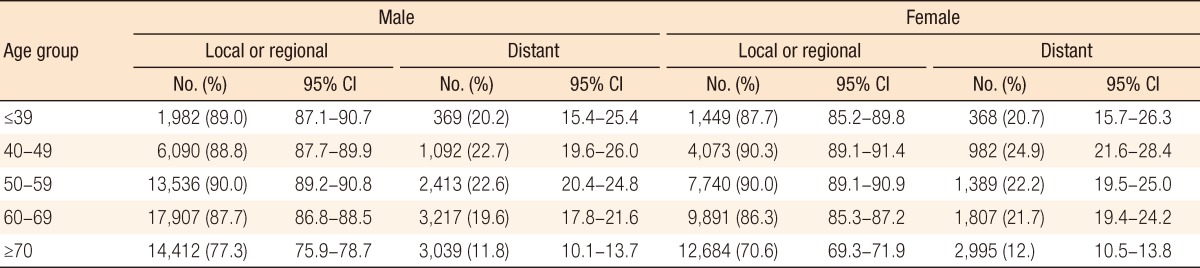

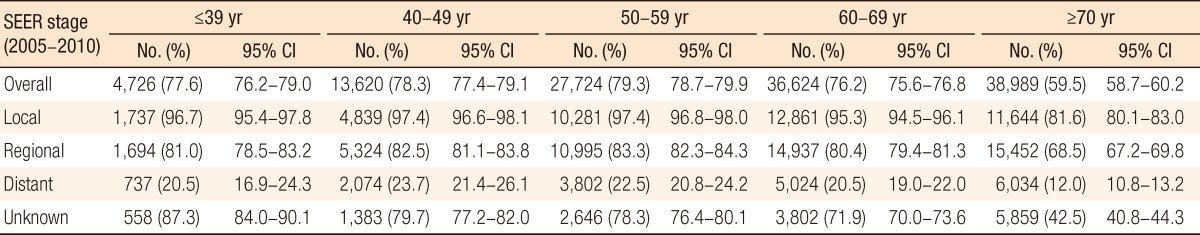

In general, females showed worse survival than males (Table 3). In the comparison of sex difference by SEER stage, we observed that elderly women (more than 70 years old), especially those with local or regional disease, had a significantly lower survival rate than men (Table 4). In addition, women were diagnosed at an older age than men. The distribution of age at the time of diagnosis was shifted slightly to older age in females while median age in men remained fairly stable between 2005 and 2010 (Fig. 1). The elderly patients, more than 70 years of age, showed a survival that was somewhat divergent from the survivals of other age groups. Poor survival rate was mostly seen among the SEER stage in this age group (Table 5). This is quite similar to what was observed in the survivals for both men and women. The poor survival of elderly women may largely contribute to the survival difference.

Table 3.

Five-year relative survival of colorectal cancer by sex according to disease state

SEER, surveillance epidemiology and end results; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Five-year relative survival of colorectal cancer by sex according to age group (2005-2010)

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Time trends of median age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer between men and women.

Table 5.

Five-year relative survival of colorectal cancer by age group according to disease state

SEER, surveillance epidemiology and end results; CI, confidence interval.

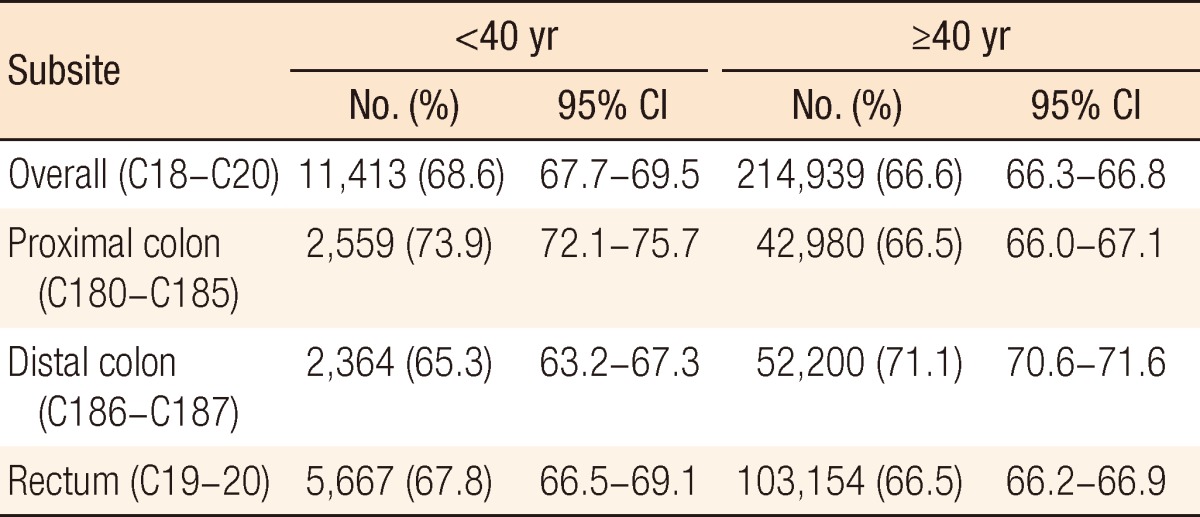

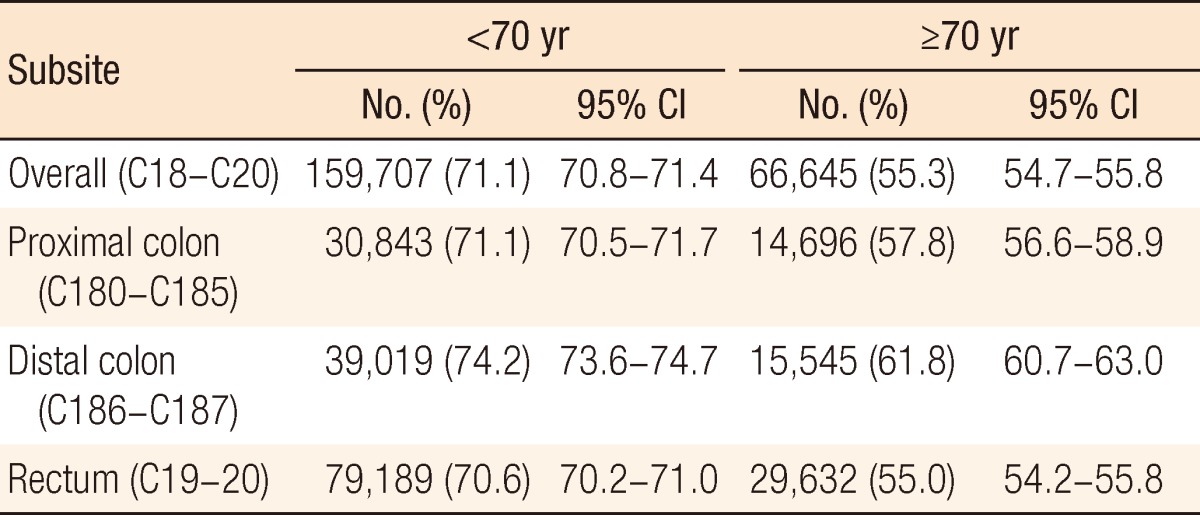

Generally, CRC is regarded as a disease of older patients. Nevertheless, the incidence of CRC at 39 years of age or younger was about 5% in Korea. Except for distal colon cancer, the survival in young patients was slightly higher than the survivals in patients in their forties and in even older patients (Table 6). On the contrary, CRC in the advanced-age group (70 or older) a total incidence of 29.4% and showed a low survival rate for all tumor subsites compared to CRC in patients younger than 70 years of age (Table 7).

Table 6.

Five-year survival rates in colorectal cancer according to patients aged <40 years and ≥40 years (the Korea Central Cancer Registry, 1993-2010)

CI, confidence interval.

Table 7.

Five-year survival rates in colorectal cancer according to patients aged <70 years and ≥70 years (the Korea Central Cancer Registry, 1993-2010)

CI, confidence interval.

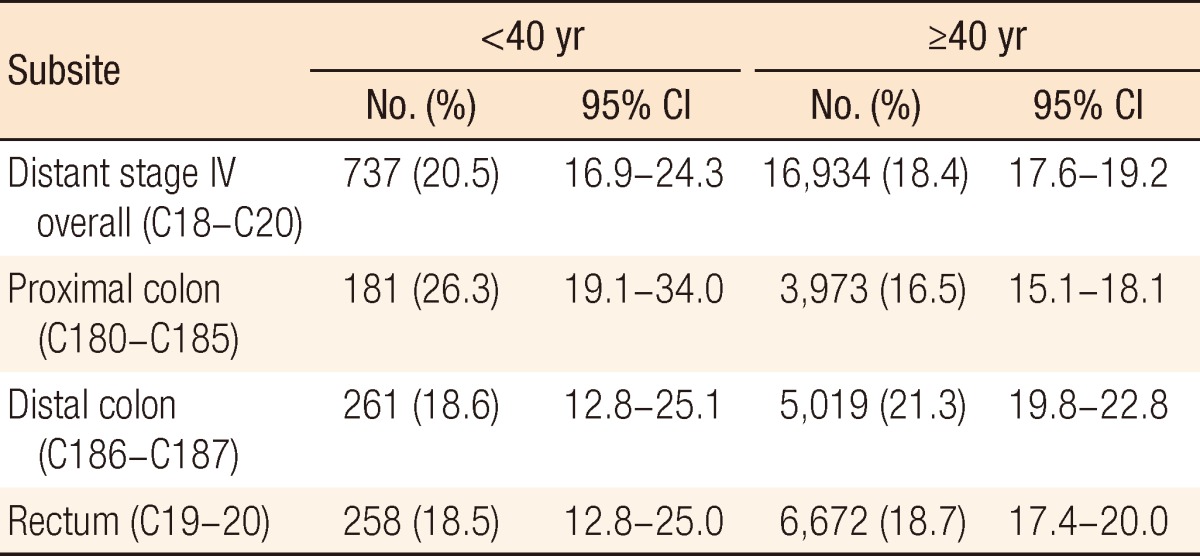

These findings continued to overall survival with distant disease. Our detailed analysis showed better survival in distant disease from proximal colon cancer in the young-age group, but survivals from tumors at other sites did not show significant differences (Table 8). In the advanced-age group, the survival with distant disease was lower for all tumor subsites than it was for the other age groups (Table 9).

Table 8.

Five-year survival rates in distant colorectal cancer (stage IV) according to patients aged <40 years and ≥40 years (the Korea Central Cancer Registry, 2005-2010)

CI, confidence interval.

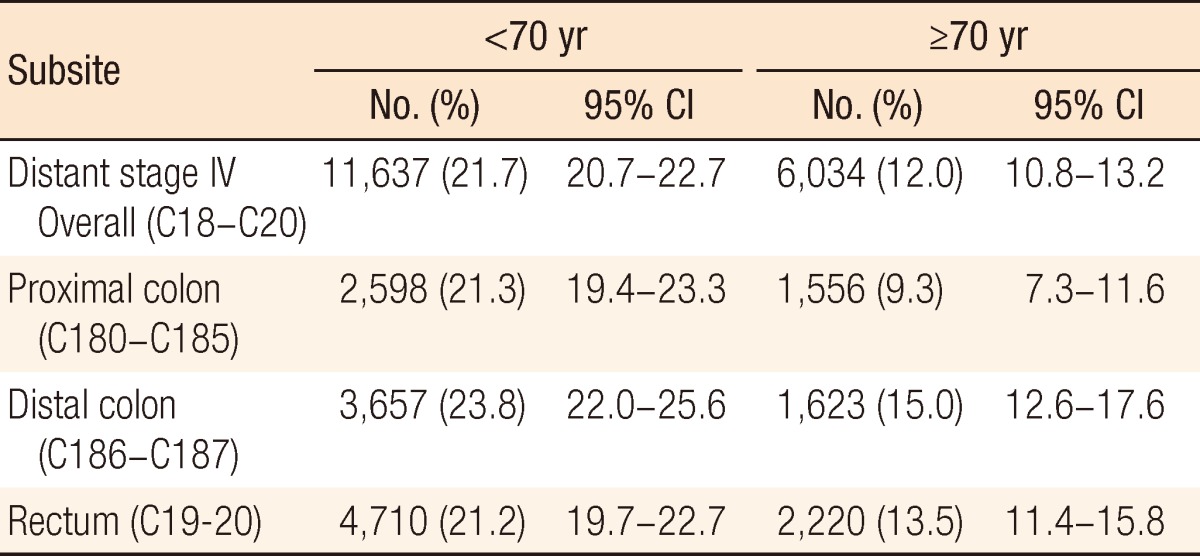

Table 9.

Five-year survival rates in distant colorectal cancer (stage IV) according to patients aged <70 years and ≥70 years (the Korea Central Cancer Registry, 2005-2010)

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Survival for CRC has improved in Korea during the last decades. Although this better prognosis may not adequately reflect the important progress in the diagnosis and the management of CRC, it is evident that many Korean clinicians have made an effort to improve survival. Many studies have reported a right shift in the incidence of CRC, and that may be due to the greater likelihood of a scope examination [6-9].

A previous study supports this finding, an increase in the incidence of distal colon, followed by proximal colon cancer. On the contrary, over the period, there has been a slow, but steady, decline in the proportion of rectal cancers among CRCs [4]. Recently, the prognosis for patients with proximal colon cancer was worse than that for patients with distal colon [10-13]. However, the reason for and the clinical implication of the difference in survival remain unclear, although many distinct characteristics have been assessed. Weiss et al. [14] reported that no difference in 5-year mortality was observed between right- and left-sided colon cancers. In addition, they showed that proximal colon cancer had a lower mortality in stage II whereas and a higher mortality in stage III. They suggested that tumor biology, including microsatellite instability (MSI), may be associated with this finding. MSI was found more in stage II proximal colon cancer, and this was related to a favorable prognosis. We also demonstrated that survival for right-sided colon cancer was poorer than that of distal colon and that this difference was more significant over regionally advanced disease.

Preoperative chemoradiation has recently been a main treatment option in rectal cancer. Although down-staging of rectal cancer may occur after this therapy, this study was reflective of only final pathologic staging. Thus, for a better understanding of rectal cancer survival, the proportion of patients with preoperative chemoradiation must be considered.

In Korea, a significantly high rate of increase of CRC was observed among males [1]. Male gender was suggested to be a risk factor for CRC; this finding was associated with smoking and alcohol consumption [15-19]. Gender differences in CRC have been studied based on tumor site and patient characteristics. Women are more likely to develop proximal colon cancer with MSI-H (high) [20, 21]. Although the reason for this gender difference is unknown, this may be responsible for the better prognosis in women. Moreover, the survival after resection has been observed to be longer in women than men [22], and female cancer patients in Korea show an improved survival for the majority of solid tumors [23]. However, females had worse survival than males in our CRC data. This difference was prominent in patients with over seventies. Household income and the economic recession were shown to possibly be related to reluctance to undergo CRC screening [24]. Also elderly women were reported to undergo less aggressive medical therapy for advanced disease [22]. Therefore, this finding may be associated with socioeconomic factors and with the hesitancy to undergo aggressive therapy in elderly Korean women. These patients may also be less likely to be afforded regular health monitoring and may have fewer opportunities for earlier diagnosis. Age played a certain role in poor survival and may be an impediment to continued improvements in the prognosis.

In metastatic CRC, Hendifar et al. [25] observed that younger women had longer survival than men whereas older women had shorter survival. They reported that this finding might be related to estrogen, which has been associated with the prevention of colon cancer. Our data support this finding, as shown Table 4.

The relation between young age and prognosis remains controversial. Some studies showed poor survival in younger patients, with advanced disease, later stage or aggressive histology [26-29]. Cancer in the young-age group may be associated with proximal location, a mucinous or poorly-differentiated component, and familial history. On the other hand, some studies have shown no differences in survival between younger and older patients with CRC [30-33].

The incidence of CRC at 39 years or younger was reported between 1.6% and 23% and our data showed 5%. We found that young patients showed comparable survival with patients aged more than 40 years. However, young patients with distal colon cancer should be considered on poor survival. In addition, this finding may be interpreted carefully in the relatively low portion of young age patients and the survival difference should be followed for a better understanding of outcomes according to age.

Elderly age had worse survival than younger age at all SEER stage and tumor sites. Elderly patients were less likely received additional therapy for their disease and to be offered chemotherapy. Comorbidities and poor performance state may also have impacted on their limitation of treatment. It was reported that selective elderly patients who receive chemotherapy were similar to the survival of younger patients [34]. In addition, age was not necessarily influence on the survival under chemotherapy group despite the regimen [35, 36]. Therefore, our data can support the concept that low survival with elderly patients (more than 70 years) may reflect patient selection in Korea. However, treatment rate may have been increased in Korean elderly patients and this difference should be followed continuously.

In metastatic CRC, survival rates of young age under 40 years showed comparable survival except proximal colon cancer which showed better survival compared to their counterpart. Elderly patients more than 70 years also demonstrated poor survival at all tumor sites.

Resection of primary tumor in stage IV CRC has been controversial to benefit in survival [37]; however, recently, this may effect on the improvement of survival [38-42]. Young or elder patient may have extensive metastatic tumor burden and less likely to undergo resection of tumor. Therefore, investigation and comparison of accurate resection rate according to age group can explain this survival difference. In summary, although this study is based on the KCCR with limited availability, such as limited information on SEER stage before 2005, it provides valuable information about survival characteristics of Korean CRC from nationwide database.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Grant (NCC-1310220).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013;45:1–14. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin A, Joo J, Bak J, Yang HR, Kim J, Park S, et al. Site-specific risk factors for colorectal cancer in a Korean population. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:11–24. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin A, Kim KZ, Jung KW, Park S, Won YJ, Kim J, et al. Increasing trend of colorectal cancer incidence in Korea, 1999-2009. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:219–226. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ederer F, Heise H. Instructions to IBM 650 programmers in processing survival computations. Methodological note No. 10. End results evaluation section. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cucino C, Buchner AM, Sonnenberg A. Continued rightward shift of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1035–1040. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saltzstein SL, Behling CA. Age and time as factors in the left-to-right shift of the subsite of colorectal adenocarcinoma: a study of 213,383 cases from the California Cancer Registry. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:173–177. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225550.26751.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh H, Demers AA, Xue L, Turner D, Bernstein CN. Time trends in colon cancer incidence and distribution and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy utilization in Manitoba. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1249–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen IK, Bray F. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence in Norway 1962-2006: an interpretation of the temporal patterns by anatomic subsite. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:721–732. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng X, Chen VW, Steele B, Ruiz B, Fulton J, Liu L, et al. Subsite-specific incidence rate and stage of disease in colorectal cancer by race, gender, and age group in the United States, 1992-1997. Cancer. 2001;92:2547–2554. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011115)92:10<2547::aid-cncr1606>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meguid RA, Slidell MB, Wolfgang CL, Chang DC, Ahuja N. Is there a difference in survival between right-versus left-sided colon cancers? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2388–2394. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0015-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benedix F, Kube R, Meyer F, Schmidt U, Gastinger I, Lippert H, et al. Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:57–64. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c703a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suttie SA, Shaikh I, Mullen R, Amin AI, Daniel T, Yalamarthi S. Outcome of right- and left-sided colonic and rectal cancer following surgical resection. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G, et al. Mortality by stage for right-versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: Medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botteri E, Iodice S, Raimondi S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Cigarette smoking and adenomatous polyps: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:388–395. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2406–2415. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmeister M, Schmitz S, Karmrodt E, Stegmaier C, Haug U, Arndt V, et al. Male sex and smoking have a larger impact on the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia than family history of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung SJ, Kim YS, Yang SY, Song JH, Park MJ, Kim JS, et al. Prevalence and risk of colorectal adenoma in asymptomatic Koreans aged 40-49 years undergoing screening colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, Polychronopoulos E, Xinopoulos D, Linos A, et al. Alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer in a Mediterranean population: a case-control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:703–710. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31824e612a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsaleh H, Joseph D, Grieu F, Zeps N, Spry N, Iacopetta B. Association of tumour site and sex with survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:1745–1750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashktorab H, Smoot DT, Carethers JM, Rahmanian M, Kittles R, Vosganian G, et al. High incidence of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer from African Americans. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1112–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulson EC, Wirtalla C, Armstrong K, Mahmoud NN. Gender influences treatment and survival in colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1982–1991. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181beb42a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung KW, Park S, Shin A, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Jun JK, et al. Do female cancer patients display better survival rates compared with males? Analysis of the Korean National Registry data, 2005-2009. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myong JP, Kim HR. Impacts of household income and economic recession on participation in colorectal cancer screening in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1857–1862. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendifar A, Yang D, Lenz F, Lurje G, Pohl A, Lenz C, et al. Gender disparities in metastatic colorectal cancer survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6391–6397. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parramore JB, Wei JP, Yeh KA. Colorectal cancer in patients under forty: presentation and outcome. Am Surg. 1998;64:563–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minardi AJ, Jr, Sittig KM, Zibari GB, McDonald JC. Colorectal cancer in the young patient. Am Surg. 1998;64:849–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin JT, Wang WS, Yen CC, Liu JH, Yang MH, Chao TC, et al. Outcome of colorectal carcinoma in patients under 40 years of age. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:900–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairley TL, Cardinez CJ, Martin J, Alley L, Friedman C, Edwards B, et al. Colorectal cancer in U.S. adults younger than 50 years of age, 1998-2001. Cancer. 2006;107(5 Suppl):1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung YF, Eu KW, Machin D, Ho JM, Nyam DC, Leong AF, et al. Young age is not a poor prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1255–1259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitry E, Benhamiche AM, Jouve JL, Clinard F, Finn-Faivre C, Faivre J. Colorectal adenocarcinoma in patients under 45 years of age: comparison with older patients in a well-defined French population. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:380–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02234737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Yo CK. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schellerer VS, Merkel S, Schumann SC, Schlabrakowski A, Fortsch T, Schildberg C, et al. Despite aggressive histopathology survival is not impaired in young patients with colorectal cancer: CRC in patients under 50 years of age. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar R, Jain K, Beeke C, Price TJ, Townsend AR, Padbury R, et al. A population-based study of metastatic colorectal cancer in individuals aged ≥ 80 years: findings from the South Australian Clinical Registry for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:722–728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho C, Ng K, O'Reilly S, Gill S. Outcomes in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with capecitabine: a population-based analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2005;5:279–282. doi: 10.3816/ccc.2005.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khattak MA, Townsend AR, Beeke C, Karapetis CS, Luke C, Padbury R, et al. Impact of age on choice of chemotherapy and outcome in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scoggins CR, Meszoely IM, Blanke CD, Beauchamp RD, Leach SD. Nonoperative management of primary colorectal cancer in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:651–657. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Cohen AM, Wong WD. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:722–728. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo LJ, Leu SY, Liu MC, Jian JJ, Hongiun Cheng S, Chen CM. How aggressive should we be in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1646–1652. doi: 10.1007/BF02660770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook AD, Single R, McCahill LE. Surgical resection of primary tumors in patients who present with stage IV colorectal cancer: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data, 1988 to 2000. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:637–645. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Koch R, Ludwig K. Factors predicting survival in stage IV colorectal carcinoma patients after palliative treatment: a multivariate analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:211–217. doi: 10.1002/jso.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konyalian VR, Rosing DK, Haukoos JS, Dixon MR, Sinow R, Bhaheetharan S, et al. The role of primary tumour resection in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:430–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]