Abstract

Aging reduces the number of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the bone marrow which leads to impairment of osteogenesis. However, if MSCs could be directed toward osteogenic differentiation, they could be a viable therapeutic option for bone regeneration. We have developed a method to direct the MSCs to the bone surface by attaching a synthetic high affinity and specific peptidomimetic ligand (LLP2A) against integrin α4β1 on the MSC surface, to a bisphosphonate (alendronate, Ale) that has high affinity for bone. LLP2A-Ale increased MSCs migration and osteogenic differentiation in vitro. A single intravenous injection of LLP2A-Ale increased trabecular bone formation and bone mass in both xenotransplantation and immune competent mice. Additionally, LLP2A-Ale prevented trabecular bone loss after peak bone acquisition was achieved or following estrogen deficiency. These results provide a proof of principle that LLP2A-Ale can direct MSCs to the bone to form new bone and increase bone strength.

Introduction

A decrease in the number of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the bone marrow with aging leads to reduced osteogenesis and bone formation 1–3. Bone regeneration through induction of MSCs could promote osteogenesis and provide a rational therapeutic strategy for preventing age-related osteoporosis. Both autologous and allogeneic stem cells have been successfully infused for the treatments of degenerative heart, neuronal diseases or for injury repair 4–6. However, systemic infusions of MSCs in vivo have failed to promote an osteogenic response in bone due to the inability of MSCs to home to the bone surface unless they were genetically modified 7–10 or following certain conditions such as injuries 8,11,12. This has become a major obstacle for MSC transplantation13,14. Even if the transplanted MSCs make it to “bone”, they are usually observed engrafted in the upper metaphysis, the epiphysis, within bone marrow sinusoids or the Haversian system 14–16 rather than at the bone surface. Subsequently, the cells are removed from bone marrow within 4–8 weeks and do not show long term engraftment14,15,17.

MSCs within the bone marrow have multi-lineage potential that give rise to a number of cell types including osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes 18,19. MSCs undergo osteogenic differentiation in the bone marrow 9,20, and mobilization of the osteoblastic progenitors to the bone surface is a critical step in osteoblast maturation and formation of mineralized tissue 21,22. Bone cells at all maturation stages are dependent on cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions23,24. Once the osteoblastic progenitors are “directed” to the bone surface, they synthesize a range of proteins including osteocalcin, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, osteonectin, collagen-I and fibronectin that will further enhance the adhesion and maturation of osteoblasts25,26. These interactions are largely mediated by transmembrane integrin receptors that primarily utilize an arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) sequence to identify and bind to specific ligands. MSCs express integrins α1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 11, CD51 (integrin αV), and CD29 (integrins β1) 27, while integrins with β1 subunit are reported to be expressed in the osteoblasts 23,25. Integrin α5 is required for MSC osteogenic differentiation 28, and overexpression of α4 integrin in MSCs has been reported to increase homing of MSCs to bone 29. These studies suggest a therapeutic strategy for bone regeneration could be directed toward the integrins that are present on the MSCs surface and could bring the MSCs to the bone surface.

We used a one-bead-one compound (OBOC) combinatorial library method to develop a high affinity and specific peptidomimetic ligand, LLP2A, against activated α4β1 integrin (IC50 = 2 pM) 30. However, scrambled LLP2A ligand, loses its affinity to α4β130. We conjugated the LLP2A to a bisphosphonate, alendronate, which served as a bone seeking component, to “direct” cells and the compound to bone. We hypothesized this hybrid compound, LLP2A-alendronate (LLP2A-Ale, Supplementary Fig. 1), could be used to direct MSCs to bone and augment bone formation.

Results

General in vivo and in vitro effects

We treated the mice with a wide range of LLP2A-Ale doses (0.03 nmol – 2 nmol) and did not observe any organ toxicity as evaluated by standard measurements of weight, kidney and liver function, and calcium metabolism. Also, we did not observe extraskeletal calcifications in mice treated with either LLP2A or LLP2A-Ale.

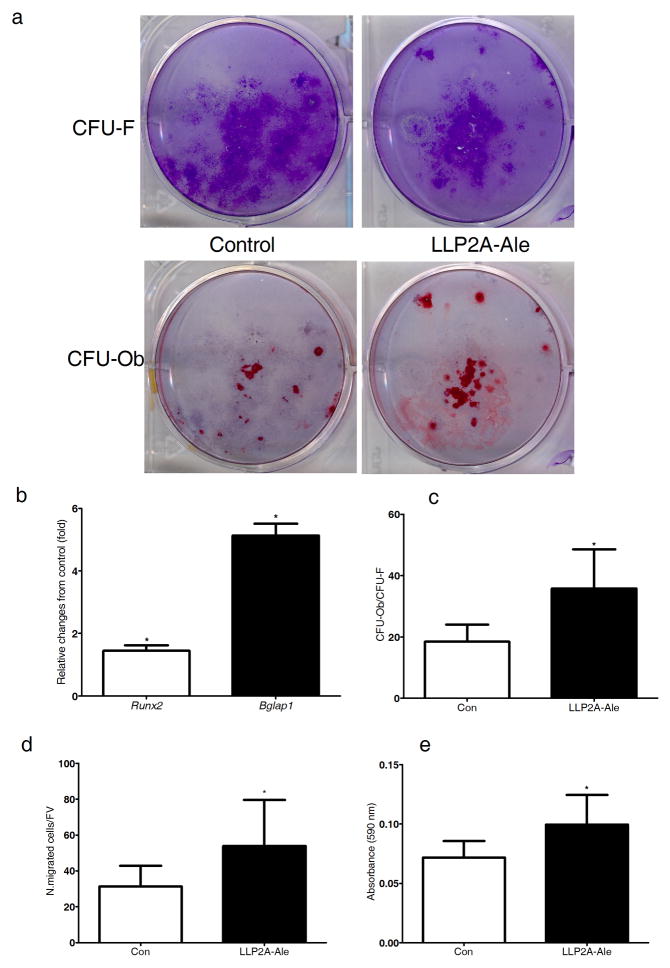

We used color-coded peptide-beads (rainbow beads) to semi-quantitatively determine the integrin profiles of MSCs undergoing osteogenic differentiation 31. We found that α4β1 integrin was highly expressed in the osteoprogenitor cells and had high affinity to LLP2A (Supplementary Fig. 2). LLP2A-Ale increased both MSC osteoblast maturation and function (Fig. 1a, c) as well as their migration (Fig. 1d, e) but did not affect their chondrogenic or adipogenic potentials.

Figure 1. LLP2A-Ale increases MSC migration and BMSC osteoblastic differentiation.

Primary BMSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium (control, Con) or with LLP2A-Ale (45nM) for 14–21 days. (a) Representative plates for total colony forming units (CFU-F) stained with crystal violet. (b) Osteoblastic units (CFU-Ob) stained with Alizarin Red in the same plates. (c) Relative Runx2 and Bglap1 expression at days 14 of the culture. (d) Transwell assays for the migration of mouse MSCs with control or addition of LLP2A-Ale cultured in serum-free media for 10 hours. The migrated cells were counted and then (e) the crystal violet staining was eluted and read at OD 590 nm. N. migrated cell/FV, number of migrated cells per field of view. *, P < 0.05 verse control. All the experiments were done in triplicate. Data are represented as Mean ± SD.

LLP2A-Ale increases MSCs bone homing and retention

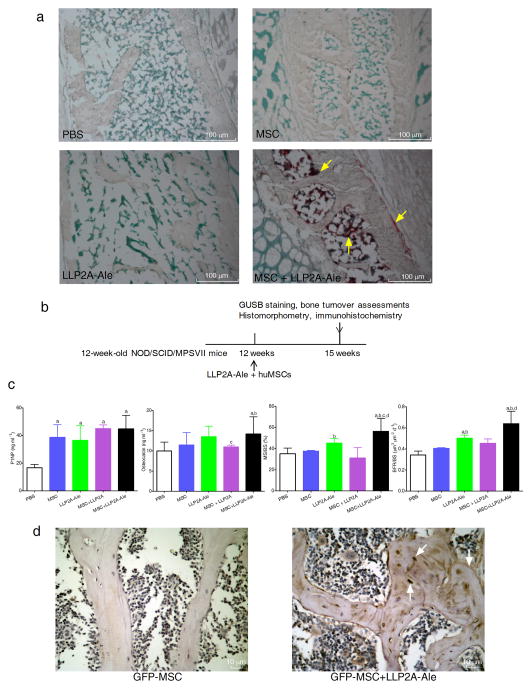

To determine if LLP2A-Ale could direct transplanted MSCs to bone, we performed a xenotransplantation study. We intravenously (IV) injected human MSCs (huMSCs) or with LLP2A-Ale to NOD/SCID/MPSVII mice. Twenty-four hours after the IV injection, we observed a number of huMSCs adjacent to the periosteal, endocortical and trabecular bone surfaces in the lumbar vertebral bodies (LVB) only in mice co-injected with LLP2A-Ale and huMSCs (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. LLP2A-Ale increases homing and retention of the transplanted MSC to bone.

Three-month-old MSPVII mice received a single intravenous injection of PBS, huMSCs (5 × 105), LLP2A-Ale, or huMSCs + LLP2A-Ale. The mice were sacrificed at 24 hours (a) or after three weeks (b) n = 6~12/group. Following sacrifice, lumbar vertebral bodies (LVB) were harvested. Frozen LVB sections were obtained and stained using naphthol-AS-BI-β-Dglucuronid as a substrate. At 24-hours after the transplantation, human MSCs, make visible by red staining (yellow arrows) accumulated in bone marrow, adjacent to both trabecular and periosteal bone surfaces in mice treated with huMSCs + LLP2A-Ale (a). (c) Serum bone turnover markers and bone formation measured at the 5th LVB three weeks after the injection and MSC transplantation. (d) Mice received one single intravenous dose of LLP2A-Ale (0.9 nmol/mouse) and GFP-MSC (5 × 105) or GFP-MSC. n = 6/group. Mice were sacrificed three weeks after the injection. Representative LVB images were taken from mice received GFP-MSC or GFP-MSC + LLP2A-Ale. GFP+ brown stained cells were sparsely observed within bone marrow, adjacent to the trabecular bone surface and within bone matrix (white arrows) in GFP-MSC + LLP2A-Ale treated mice. MS/BS, mineralizing surface; BFR/BS, bone surface-based bone formation rate. a, P < 0.05 vs. PBS; b, P < 0.05 vs. MSC; c, P < 0.05 vs. LLP2A-Ale; d, P < 0.05 vs. MSC + LLP2A. Data are represented as Mean ± SD.

At three weeks, huMSC cells were observed adjacent to the bone surface and embedded within in the bone matrix only in the huMSC+LLP2A-Ale treated group, suggesting that there was retention of the transplanted huMSCs (Supplementary Fig. 3a) in bone. We observed significantly higher levels of procollagen type I amino-terminal prepeptide (P1NP), an early osteoblast differentiation marker, in LLP2A-Ale or MSC treated groups. While osteocalcin, an osteoblast maturation marker, and bone formation parameters were significantly higher in LLP2A-Ale and MSCs + LLP2A-Ale treated groups compared to PBS or MSC controls (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2b–c).

In mice that were treated with green fluorescent protein (GFP) labeled mouse MSCs or with LLP2A-Ale, the combination treatment significantly increased the number of the GFP-positive osteoblasts and osteocytes at both the trabecular (Fig. 2d) and cortical bone regions (Supplementary Fig. 3b) of the LVB at three weeks. Collectively, these data demonstrate that LLP2A-Ale can direct transplanted MSCs to bone, and this increased the MSCs homing and retention to bone and enhanced endosteal and periosteal bone formation in this xenotransplantation model.

LLP2A-Ale augments bone formation in immunocompetent mice

To determine if LLP2A-Ale could augment endogenous bone formation in immune competent mice without MSC transplantation, we used two-month-old female 129SvJ mice that received two doses of LLP2A-Ale that represented the significantly effective dose and maximum anabolic dose in our preliminary studies. Two days after the IV injections, expressions of LLP2A, Runx2, or bromodeoxyuridine+ (Brdu) cell populations were mainly found expressed within the bone marrow in the LLP2A-treated group but expressed at the bone surface in the LLP2A-Ale group (Supplementary Fig. 4). LLP2A and Brdu were not detectable in the LVB by 21 days.

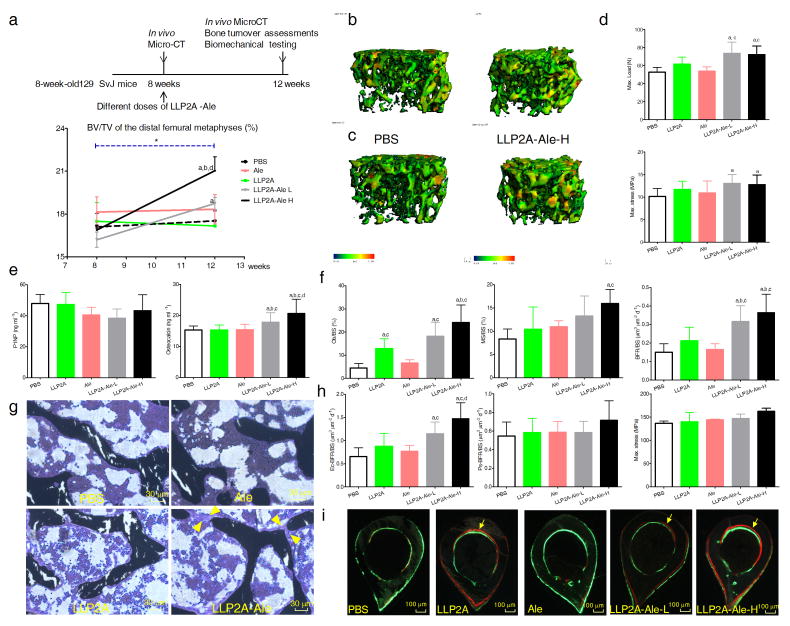

LLP2A-Ale increased the distal femoral (DF) trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) and thickness from baseline; and both doses of LLP2A-Ale increased BV/TV (Fig. 3a–c) with increased maximum load and strength as compared to the control groups at 12-weeks (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3d). LLP2A-Ale dose-dependently increased osteocalcin (Fig. 3e), did not change total TGF-β1 (Supplementary Fig. 5b), and increased surface-based bone formation parameters at the DF (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3f). More importantly, LLP2A-Ale treatment increased osteoblast surface and formed bridges between adjacent trabeculae (Fig. 3g). Bone formation rates on the endocortical surfaces of the tibial shafts were increased in groups that had LLP2A component (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3h, i).

Figure 3. LLP2A-Ale increases trabecular bone mass in immune competent mice.

(a) Two-month-old female 129SvJ mice received a single intravenous injection of PBS, alendronate (Ale), LLP2A or LLP2A-Ale [Low (0.36nmol/mouse or High (0.9nmol/mouse)]. n = 8/group. (b) Representative 3-dimensional thickness maps from microCT scans of trabecular bone from the distal femur metaphyses at baseline (8-week-old) or (c) from the same animals and at the same bone sites 4 weeks after a single injection (12-week-old). The width of the trabecular is color-coded, the blue-green color represents thin trabeculae and yellow-red color represents thick trabeculae. (d) Maximum load and maximum stress of the 6th lumbar vertebral bodies at 12 weeks of age, 4 weeks following one injection. (e) Bone turnover markers measured from the serum. (f) Surface-based bone histomorphometry was performed on the right distal femurs. Ob/BS, osteoblast surface; MS/BS, mineralizing surface; BFR/BS, bone surface-based bone formation rate. (g) Representative images from the trabecular bone of the distal femurs. Yellow arrowheads illustrate osteoblastic bridges between the trabeculae in an LLP2A-Ale treated mouse. (h) Surface-based bone histomorphometry was performed at the endosteal surface (Ec) and the periosteal surface (Ps) four weeks after the injections. Maximum stress of the femurs performed four weeks after the injections. (i) Representative cross sections of the tibial shafts from PBS, LLP2A, LLP2A or LLP2A-Ale treatment groups. Yellow arrows illustrate double labeled bone surfaces. a, P < 0.05 vs. PBS; b, vs. LLP2A; c, vs. Ale; d, vs. LLP2A-Ale-L. Data are represented as Mean ± SD.

LLP2A-Ale prevents trabecular bone losses induced by aging or estrogen deficiency

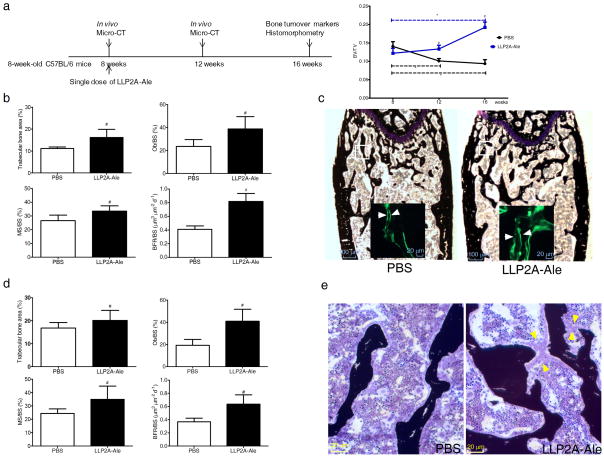

The C57BL/6 mice usually achieve their peak bone mass by six to eight weeks of age and this is followed by a approximately 50% decline in both bone formation and bone mass from 2–4 months of age 32,33. LLP2A-Ale prevented age-related trabecular bone loss after peak bone acquisition was achieved (Fig. 4a) with increased bone formation parameters at the DF (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b, c) as well as at the LVB (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4d, e). Osteoblast bridges were observed in both trabecular bone sites (Fig. 4e). These data suggest that one IV injection of LLP2A-Ale prevented age-related reductions in trabecular bone mass and bone formation for up to eight weeks in C57BL/6 mouse strain.

Figure 4. LLP2A-Ale prevents age-related trabecular bone loss.

(a) Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice received one single intravenous injection of PBS or LLP2A-Ale (0.9nmol/mouse, n = 6/group). Repeated microCT scans were performed at the distal femurs to obtain changes of trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) over the experimental period. (b) Trabecular bone area, osteoblast surface (Ob/BS), mineralizing surface (MS/BS) and bone formation rate/bone surface (BFR/BS) performed at the distal femoral metaphyses. (c) Representative distal femur sections from PBS or LLP2A-Ale-treated mice at 16 weeks. White squares represent selected areas under higher magnification fluorescence images that demonstrate mineral apposition. White arrows illustrate the distances between the double labels. (d) Trabecular bone area, Ob/BS, MS/BS and BFR/BS performed at the 5th lumbar vertebral body (LVB) sections from PBS or LLP2A-Ale-treated mice at 16 weeks. (e) Representative images taken from the trabecular bone at the 5th-LVB. Yellow arrow heads illustrates osteoblastic bridges in a LLP2A-Ale treated mouse. #, P < 0.05 vs. PBS at the same time point (8 or 16 weeks). *, P < 0.05 from the baseline. Data are represented as Mean ± SD.

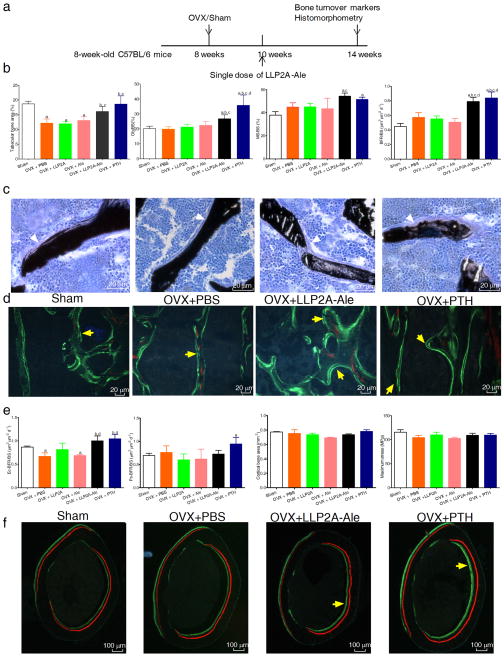

To determine whether LLP2A-Ale could prevent bone loss in a disease state, 10-week-old ovariectomized (OVX) mice were treated with PBS, Ale, LLP2, LLP2A-Ale or PTH 2-weeks after ovariectomy (Fig. 5a). LLP2A-Ale treatment increased osteoblast numbers (osteoblast surface) and their activities (mineralizing surface) and BFR/BS at the LVB (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5b–d). Both LLP2A-Ale and PTH increased endocortical bone formation from OVX (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5e, f). Cortical bone thickness and maximum stress were not significantly altered by OVX, Ale, and LLP2A, one single IV injection of LLP-Ale or four weeks of PTH treatment (Fig. 5e). This data suggested the activation of endosteal bone formation by LLP2A-Ale that was comparable to that of PTH in this acute estrogen deficiency model.

Figure 5. LLP2A-Ale partially prevents trabecular bone loss and increases endosteal bone formation in ovariectomized mice.

(a) Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were ovariectomized. One single intravenous injection of LLP2A-Ale was given two-weeks after OVX. PTH was given subcutaneously at 25 μg/kg/d, 5x/week for 4 weeks. Mice were sacrificed at 14 weeks of age. n = 6~8/group. (b) Histomorphometric analyses of the 5th lumbar vertebral bodies included trabecular bone area (%), osteoblast surface (Ob/BS), mineralizing surface (MS/BS) and bone formation rate/bone surface (BFR/BS). (c) Representative images from the trabecular bone at the 5th lumbar vertebral bodies. White arrowheads illustrate osteoblasts. (d) Representative fluorescent images from the trabecular bone at the 5th lumbar vertebral trabeculae. Yellow arrows illustrate double labeled trabecular bone surfaces. (e) Histomorphometry analyses of the right mid-femurs included bone formation at the endosteal (Ec) or periosteal (Ps.) bone surfaces, and cortical bone thickness. Three-point bending was performed on left femurs to obtain maximum stress of the femurs. (f) Representative images from the mid-femur sections. Short yellow arrows illustrated double labeled endocortical bone surfaces. a, p < 0.05 versus Sham; b, P < 0.05 vs. OVX+PBS, c, P < 0.05 vs. OVX+ LLP2A; d, P < 0.05 vs. OVX+Ale. Data are represented as Mean ± SD.

Discussion

MSCs are precursors of osteoblasts. MSCs do not readily migrate to the bone and this creates a major obstacle for the use of MSCs for bone regeneration. We have developed a ligand that targets integrin α4β1, a protein highly expressed by MSCs undergoing osteoblast differentiation. Instead of using genetically modified MSCs, we attached LLP2A to a bisphosphonate to guide the MSCs to the bone surface. Bisphosphonates are prescribed to reduce bone resorption and improve bone strength. Since we used approximately 1/10th of the therapeutic dose of alendronate in our compound, we did not observe any anti-resorptive effects. We observed an uncoupling of bone remodeling with bone formation and no significant changes in bone resorption during this short-term study period. This uncoupling of bone remodeling in favor of bone formation is also observed with short term treatment with the anabolic agent, hPTH (1–34)34. We hypothesized that we would also see a return to coupling of bone turnover with this intervention after a longer treatment period. Additionally, the current alendronate concentrations used in these studies did not suppress TGF-β1 secretion, a growth factor critical in coupling bone resorption and endogenous stem cell recruitment to bone35.

By using a xenotransplantation model, LLP2A-Ale increased homing and retention of the transplanted MSCs to bone, which indicates a breakthrough in the application of using transplanted MSCs to augment bone formation. The transplanted human or mouse MSCs were found embedded in bone matrix as osteocytes or adjacent to the bone surface as osteoblasts. Apart from increasing bone formation rates at both the endocortical and trabecular surfaces, the periosteal bone formation rate was also increased following MSC transplantation and LLP2A-Ale treatment. This is important as the total cross-sectional area increase by periosteal expansion is the most significant determinant of bone strength 36. Our finding that LLP2A-Ale can direct transplanted human MSCs to the bone is of major significance. This approach provides a means to overcome a major obstacle for using MSCs in the treatment of bone degenerative diseases and as such represents a new and novel treatment option for osteoporosis.

Furthermore, LLP2A-Ale might also increase endogenous MSC osteoblast differentiation and augment bone formation. Although we could not directly track the endogenous MSCs lineage commitment to osteoblasts as there is no single marker that allows us to define or track the migration of the endogenous MSCs to bone or their osteoblast differentiation in vivo. However, we were able to partially overcome this limitation by using control groups with equivalent doses of alendronate and LLP2A. Since LLP2A is a specific ligand for activated α4β1 integrin, our findings support the previous report that targeting α4 alone could increase MSC bone homing 37. However, LLP2A by itself failed to induce any significant changes in bone architectures. In contrast, LLP2A-Ale enhanced osteoblast maturation and functions as evidenced by increased osteocalcin levels and increased bone formation that was primary seen at the trabecular and endocortical bone surfaces that are in close contact with bone marrow. LLP2A-Ale not only increased vertebral maximum load, but also increased the maximum bone stress, a parameter that is independent of bone shape, suggesting LLP2A-Ale treatment increased bone quality in addition to the increase in bone mass. Similarly, LLP2A-Ale prevents trabecular bone loss after the peak bone mass has been achieved and partially prevents rapid trabecular bone loss induced by ovariectomy. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that LLP2A-Ale might be able to increase the migration of endogenous MSCs to bone, stimulate osteoblastic differentiation, augment bone formation and increase bone mass in young mice and prevent trabecular bone losses associated with aging or estrogen deficiency. These results differ from what we observed in NOD/SCID/MPSVII mice received MSC + LLP2A-Ale treatment, where the combination treatment also increased periosteal bone formation. This may due to either the lack of periosteal effects by LLP2A-Ale itself or it may require more than one injection or longer treatment period to achieve cortical bone responses.

In summary, we have shown that LLP2A-Ale augments endogenous bone formation and directs the transplanted MSCs to the bone to augment bone formation and bone mass. This novel approach to increase the homing and retention of the MSCs to bone should now be examined in both preclinical and clinical studies for the treatment of osteoporosis and fracture repair.

Methods

Synthesis of LLP2A-Ale

LLP2A-Ale was synthesized through conjugation of Ale-SH to LLP2A-Mal via Michael addition. The synthetic scheme is shown in supplementary Fig. 1. LLP2A-Ale was made through conjugation of LLP2A-maleimide (LLP2A-Mal) with thiolyated aledronate (Ale-SH). In brief, Ale-SH was dissolved in PBS buffer (pH7.2) containing 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), then a solution of LLP2A-Mal (1.2 eq.) in a small amount of DMSO was added to the Ale-SH solution. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and lyophilized. The powder was re-dissolved in a small amount of water and passed through a Varian MEGA BOND ELUT C18 column and eluted. The eluents were collected and checked by Mass Spec and the eluents with pure product were combined and lyophilized to yield a white powder. MALDI-TOF MS: Calculated: 1899.83 (bisphosphonic acid). Found: 1900.78 (MH+).

In vitro cell differentiation arrays of MSCs into osteogenic, chondrogenic or adipogenic lineages

Mouse MSCs were obtained under a material transfer agreement between UC Davis and Texas A&M Institute for Regenerative Medicine. These cells were relatively pure population of stromal cells that were negative for CD11b, CD45 and CD34 and positive for CD29, CD31, CD106. For osteogenic differentiation, the passage 6 mouse MSCs were used. On days 14 of the culture, a set of cells was used for RNA extraction and RT-PCR for osteoblast gene markers, Runx2 and Bglap1. At days 21, another set of cells were with 0.2% crystal violet in 2% ETOH and then photographed. The numbers of purple-stained colonies bigger than 1 mm in diameter were recorded. The plates were then eluted with 0.2% Triton TX100. The total eluted solution was run in spectrophotometer at 590 nm absorbance. The same set of plates was then stained with alizarin red (AR) to monitor mineralization nodule formation. For the chondrogenesis micromass culture, the MSCs were cultured using a STEMPRO Chondrogenesis Differentiation Kit (GIBCO Invitrogen Cell Culture) and stained with Alcian. For adipogenesis differentiation, the MSCs were cultured using a STENPRO Adipogenesis Differentiation Kit (GIBCO Invitrogen Cell Culture) and stained with Oil Red O for lipoid deposits.

In Vitro migration assays for migration of mouse bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs)

Cell migration assays were performed using Transwell migration chambers (diameter 6.5 mm, pore size 8μmm; Corning Inc.) coated with 0.5 μg/ml type I collagen. The coated filters were and placed into the lower chamber containing serum-free medium supplemented with 45nM LLP2A-Ale. BMSCs were added to the upper compartment of the transwell chamber and allowed to migrate to the underside of the top chamber for 10 hours. None migrated cells on the upper membrane were removed and the migrated cells were fixed, stained with crystal violet and counted. Subsequently, stained cells were eluted from membranes and absorbance measurements were performed using optical density (OD) 590nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Human mesenchymal stem cell (huMSC) culture

Bone marrow aspirates from human healthy donors were purchased from Lonza. For MSC isolation and expansion, bone marrow aspirates were passed through 90um pore strainers for isolation of bone spicules. Then, bone marrow aspirates were diluted with equal volume of PBS and centrifuged over Ficoll (GE Healthcare) for 30 minutes at 700 × g. Next, mononuclear cells and bone spicules were plated in plastic culture flasks, using MEM-alpha (HyClone Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals). After 2 days, non-adherent cells were removed by 2–3 washing steps with PBS. MSCs from passages 6 were used for this experiment 14.

All animals were treated according to the USDA animal care guidelines with the approval of the UC Davis Committee on Animal Research. We published the methods for Micro-CT, biochemical markers of bone turnover, bone histomorphometry, immunohistochemistry and biomechanical testing previously 38–40.

Histochemical analyses of enzyme activity

Following sacrifice, small portions of organs were harvested and frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature embedding media (Sakura) and sectioned at 12 μm. GUSB -specific histochemical analysis was performed using naphthol-AS-BI-β-D-glucuronide (Sigma-Aldrich) as a substrate, followed by counterstaining with methyl green 14.

Statistics

The group means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for all outcome variables. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate parameters derived from repeated in-vivo micro-CT scans such as the trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) and Bonferroni posthoctests were used to compare time (age)-dependent changes within the same treatment group or between the treatment groups at the same time point. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine differences between the groups for the other outcome measures obtained at the end of the studies (SPSS Version 12, SPSS Inc.). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants nos. NIAMS-5R21AR057515 (to WY) and 1K12HD05195801 that is co-funded by US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) and the US National Institute of Aging (NIA).

Some of the materials employed in this work were provided by the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Scott & White through a grant from NCRR of the NIH, Grant # P40RR017447.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W. Yao, N.E. Lane and K. Lam designed the study. M. Guan and W. Yao performed the animal study, collected data from cell culture, biochemistry, microCT, bone histomorphometry and analyzed all the data. R.W. Liu, L.P. Weng and K. Lam synthesized theLLP2A-Ale. J. Nolta and P. Zhou performed human MSC cultures and designed the experiments using the NCOD/SCID/MPSVII mice. J.J Jia and M. Shahnazari performed immunohistochemistry and helped with animal studies. B. Panganiban and R. Ritchie performed biomechanical testing and analyzed data. All authors edited the paper.

References

- 1.Stolzing A, Jones E, McGonagle D, Scutt A. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Consequences for cell therapies. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2008;129:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsara O, et al. Effects of Donor Age, Gender, and In Vitro Cellular Aging on the Phenotypic, Functional, and Molecular Characteristics of Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011 doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonyadi M, et al. Mesenchymal progenitor self-renewal deficiency leads to age-dependent osteoporosis in Sca-1/Ly-6A null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5840–5845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1036475100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, et al. A nerve graft constructed with xenogeneic acellular nerve matrix and autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5312–5324. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedram MS, et al. Transplantation of a combination of autologous neural differentiated and undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells into injured spinal cord of rats. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:457–463. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Yan F, Lei L, Li Y, Xiao Y. Application of autologous cryopreserved bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for periodontal regeneration in dogs. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;190:94–101. doi: 10.1159/000166547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutwald R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and inorganic bovine bone mineral in sinus augmentation: comparison with augmentation by autologous bone in adult sheep. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.06.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vertenten G, et al. Evaluation of an injectable, photopolymerizable, and three-dimensional scaffold based on methacrylate-endcapped poly(D,L-lactide-co-epsilon-caprolactone) combined with autologous mesenchymal stem cells in a goat tibial unicortical defect model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1501–1511. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halleux C, Sottile V, Gasser JA, Seuwen K. Multi-lineage potential of human mesenchymal stem cells following clonal expansion. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2001;2:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longobardi L, et al. Subcellular localization of IRS-1 in IGF-I-mediated chondrogenic proliferation, differentiation and hypertrophy of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Growth Factors. 2009;27:309–320. doi: 10.1080/08977190903138874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapel A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells home to injured tissues when co-infused with hematopoietic cells to treat a radiation-induced multi-organ failure syndrome. J Gene Med. 2003;5:1028–1038. doi: 10.1002/jgm.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granero-Molto F, et al. Regenerative effects of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in fracture healing. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1887–1898. doi: 10.1002/stem.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, Caplan AI. The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000047856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyerrose TE, et al. In vivo distribution of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in novel xenotransplantation models. Stem Cells. 2007;25:220–227. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho SW, et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing RANK-Fc or CXCR4 prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1979–1987. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jürg A, Gasser LCC, Lynne K. Kamibayashi. Intravenously Administered Mesenchymal OVX-Induced Bone Loss in Distribution of Labelled MSCs. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granero-Molto F, et al. Regenerative Effects of Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Fracture Healing. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1887–1898. doi: 10.1002/stem.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen M, Friedenstein AJ. Stromal stem cells: marrow-derived osteogenic precursors. Ciba Found Symp. 1988;136:42–60. doi: 10.1002/9780470513637.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruder SP, Fink DJ, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells in bone development, bone repair, and skeletal regeneration therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56:283–294. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muraglia A, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Clonal mesenchymal progenitors from human bone marrow differentiate in vitro according to a hierarchical model. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 (Pt 7):1161–1166. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams GB, et al. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen XD, Dusevich V, Feng JQ, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1943–1956. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grzesik WJ, Robey PG. Bone matrix RGD glycoproteins: immunolocalization and interaction with human primary osteoblastic bone cells in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:487–496. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vukicevic S, Luyten FP, Kleinman HK, Reddi AH. Differentiation of canalicular cell processes in bone cells by basement membrane matrix components: regulation by discrete domains of laminin. Cell. 1990;63:437–445. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90176-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gronthos S, Simmons PJ, Graves SE, Robey PG. Integrin-mediated interactions between human bone marrow stromal precursor cells and the extracellular matrix. Bone. 2001;28:174–181. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gronthos S, Stewart K, Graves SE, Hay S, Simmons PJ. Integrin expression and function on human osteoblast-like cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1189–1197. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooke G, Tong H, Levesque JP, Atkinson K. Molecular trafficking mechanisms of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells derived from human bone marrow and placenta. Stem Cells Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamidouche Z, et al. Priming integrin alpha5 promotes human mesenchymal stromal cell osteoblast differentiation and osteogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18587–18591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812334106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee S, et al. Pharmacologic targeting of a stem/progenitor population in vivo is associated with enhanced bone regeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:491–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI33102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng L, et al. Combinatorial chemistry identifies high-affinity peptidomimetics against alpha4beta1 integrin for in vivo tumor imaging. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:381–389. doi: 10.1038/nchembio798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo J, et al. Rainbow beads: a color coding method to facilitate high-throughput screening and optimization of one-bead one-compound combinatorial libraries. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:599–604. doi: 10.1021/cc8000663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao W, et al. Inhibition of the progesterone nuclear receptor during the bone linear growth phase increases peak bone mass in female mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao J, Venton L, Sakata T, Halloran BP. Expression of RANKL and OPG correlates with age–related bone loss in male C57BL/6 mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:270–277. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato M, et al. Abnormal bone architecture and biomechanical properties with near-lifetime treatment of rats with PTH. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3230–3242. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dao MA, Taylor N, Nolta JA. Reduction in levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(kip-1) coupled with transforming growth factor beta neutralization induces cell-cycle entry and increases retroviral transduction of primitive human hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13006–13011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seeman E. Periosteal bone formation--a neglected determinant of bone strength. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:320–323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar S, Ponnazhagan S. Bone homing of mesenchymal stem cells by ectopic alpha 4 integrin expression. FASEB J. 2007;21:3917–3927. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8275com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parfitt AM, et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao W, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced bone loss in mice can be reversed by the actions of parathyroid hormone and risedronate on different pathways for bone formation and mineralization. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3485–3497. doi: 10.1002/art.23954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao W, et al. Overexpression of secreted frizzled-related protein 1 inhibits bone formation and attenuates parathyroid hormone bone anabolic effects. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:190–199. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.