Abstract

Background:

The prognostic value of CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation in colorectal cancer remains controversial. We systematically reviewed the evidence for assessment of CDKN2A methylation in colorectal cancer to elucidate this issue.

Methods:

Pubmed, Embase and ISI web of knowledge were searched to identify eligible studies to evaluate the association of CDKN2A hypermethylation and overall survival and clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer patients. Combined hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were pooled using a random-effects model.

Results:

A total of 11 studies encompassing 3440 patients were included in the meta-analysis. CDKN2A hypermethylation had an unfavourable impact on OS of patients with colorectal cancer (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.29–2.11). Subgroup analysis indicated that CDKN2A hypermethylation was significantly correlated with OS in Europe (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.28–1.74) and Asia (HR 3.30; 95% CI 1.68–6.46). Furthermore, there was a significant association between CDKN2A hypermethylation and lymphovascular invasion (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.15–2.47), lymph node metastasis (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.09–2.59) and proximal tumour location (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.34–3.26) of colorectal cancer.

Conclusion:

This meta-analysis indicated that CDKN2A hypermethylation might be a predictive factor for unfavourable prognosis of colorectal cancer patients.

Keywords: CDKN2A, methylation, colorectal cancer, prognosis

Colorectal cancer is the third most frequent malignancy worldwide, and represents the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths, leading to an estimated 608 000 deaths by 2008 (Ferlay et al, 2010). Despite recent advances in the management of colorectal cancer and new developments of cancer surveillance, the majority of colorectal cancer patients are still diagnosed at an advanced stage when the therapeutic options are limited, and the 5-year survival rate of colorectal cancer patients remains much lower than expected (Ferlay et al, 2010; Jemal et al, 2010).

Many efforts have been made to identify the molecular prognostic biomarkers including epigenetic markers for patients with colorectal cancer, in order to make a better selection of therapeutic approaches after surgery and improve patients' survival (Draht et al, 2012). CDKN2A gene functions as an important tumour suppressor in various human malignancies including colorectal cancer, and its activation prevents carcinogenesis via induction of cell growth arrest and senescence (Collado et al, 2007; Rayess et al, 2012). CDKN2A promoter methylation is a frequent epigenetic event and an important mechanism leading to silencing and dysfunction of CDKN2A gene, which further results in uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumour development and progression (Samowitz et al, 2005). Ever since Liang et al (1999) reported that the presence of CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation predicted shorter survival in colorectal cancer patients, the prognostic value of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer have been widely investigated, owing to the fact that these results exhibited an increasing relevance with clinical practice. Although multiple studies were conducted on colorectal cancer patients, whether CDKN2A hypermethylation is a predictive factor for poor prognosis remains controversial, and several studies in this field possessed a small sample size. Therefore, we conducted the present meta-analysis to appraise the prognostic value of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted and reported this systematic review and meta-analysis following the PRISMA statement (Moher et al, 2009). The following were the criteria for the eligibility of included studies: (1) the study assessed the association between CDKN2A methylation and overall survival (OS) of patients with colorectal cancer; (2) the study evaluated the methylation status of CDKN2A promoter in primary tumour tissues after surgical resection; (3) the study provided a hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) directly or gave the data, which allow for the estimation of the HR and 95% CI; (4) the sample size of the study is not <40 patients.

Pubmed, Embase and ISI web of knowledge were searched by using the combinations of following terms: ‘CDKN2A', ‘p16', ‘methylation', ‘colon', 'rectum', 'colorectal', ‘cancer', ‘carcinoma', ‘prognosis', ‘prognostic' and ‘survival'. The search concluded in February 2013, and no lower date limit was used. We only included the studies that were published in the English language, given the fact that other languages were often not available for both authors and readers.

The bibliographies in selected articles were also examined to identify other relevant studies. Conference abstracts were not in the scope of this analysis owing to the insufficient data provided by the authors. All studies were carefully examined to avoid the inclusion of the duplicate data. Two reviewers (XX and CW) assessed the eligibility of the screened studies independently. Agreement was reached for the discrepancies by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted independently by two authors (XX and CW) from each eligible study. The predefined form used for data extraction documented the most relevant items including author's name, year of publication, study location, number of patients, methylation detection method, methylation rate and follow-up.

Methodological assessment

Methodological assessment for each of the included studies was performed by three investigators (XX, CW and CM) and scored them using REMARK guidelines and ELCWP quality scale (Steels et al, 2001; McShane et al, 2005). The three investigators reported the quality scores of reviewed studies independently, and reach a consensus value for each item.

Statistical analysis

For the quantitative aggregation of the survival data, HRs and their 95% CIs were used to assess the impact of CDKN2A hypermethylation on survival of colorectal cancer patients. Studies reporting results of multivariate or univariate analysis for survival were used for the aggregation of the survival data. If HRs and their corresponding SEs were not directly reported in the included studies, they were estimated according to the available survival data by using a method reported by Parmar et al (1998). The individual HR estimates were pooled into a summary HR using the approach provided in a previous published study (Yusuf et al, 1985). For the analysis of the association of CDKN2A hypermethylation and clinicopathological features, odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CIs were applied to estimate the effect. An observed HR or OR >1 implied a worse survival for the group with CDKN2A hypermethylation or the significant association between CDKN2A hypermethylation and clinicopathological characteristics, respectively. We pooled HRs and ORs of the studies by using Review Manager Version 5.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Publication bias was assessed by using a method reported by Egger et al (1997a). We also explored reasons for inter-study heterogeneity using meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis by study location, publication year, number of patients, methylation rate and quality score. The analysis of publication bias and meta-regression was performed by using STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Sensitivity analysis was conducted by omission of each single study to investigate the stability of the results.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

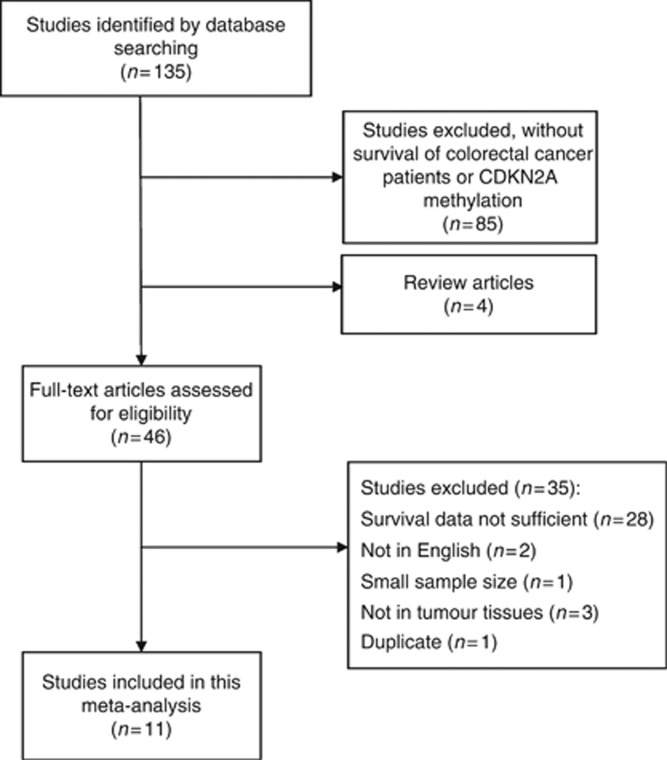

Through the database search, a total of 135 articles were identified for initial evaluation (Figure 1). After excluding the studies out of the scope of our meta-analysis, 46 studies evaluating the prognostic effect of CDKN2A hypermethylation in patients with colorectal cancer were considered for further assessment in detail. By further review, 28 were excluded because the estimation of HRs in these studies was not allowed because of the insufficient data provided by the authors, three were excluded because the authors determined the methylation status of CDKN2A promoter by using DNA from other than tumour tissues (e.g., serum), one was excluded because it had overlapped data with another study, two were excluded because the studies were not publications in English, and one was excluded because of the small sample size in this study. Therefore, 11 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were finally enrolled in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Liang et al, 1999; Esteller et al, 2001; Maeda et al, 2003; Ward et al, 2003; Ishiguro et al, 2006; Shen et al, 2007; Barault et al, 2008; Kim et al, 2010; Shima et al, 2011a; Bihl et al, 2012; Veganzones-de-Castro et al, 2012; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion.

The characteristics of the 11 eligible studies are extracted and summarised in Table 1. One study assessed the patients from China, one from Korea, two from Japan, two from Spain, one from France, one from Switzerland, two from USA and one from Australia. The total study sample size was 3440 with a mean of 313 (range, 84–902 patients). Four of these studies included <100 patients and 5 studies enrolled >200 patients (Table 1). These eligible studies were published from 1999 to 2012.

Table 1. Major features of the included studies.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Follow-up (months) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study location | Number of patients | Methylation rate (%) | Methylation detection method | Stage | Median | Range | Survival analysis |

|

Barault et al, 2008 |

France |

582 |

26.3 |

MSP |

I–IV |

— |

— |

Multivariate |

|

Bihl et al, 2012 |

Switzerland |

422 |

20.6 |

Pyrosequencing and MSP |

I–IV |

60 |

46–74 |

Multivariate |

|

Esteller et al, 2001 |

Spain |

86 |

34.9 |

MSP |

Dukes' A–C |

68 |

16–89 |

Univariate |

|

Ishiguro et al, 2006 |

Japan |

88 |

22.7 |

MSP |

I–IV |

53.2 |

— |

Univariate |

|

Kim et al, 2010 |

Korea |

131 |

10.7 |

MSP |

I–IV |

49 |

1–116 |

Univariate |

|

Liang et al, 1999 |

China |

84 |

28.6 |

MSP |

Dukes' B2 |

— |

60–86 |

Univariate |

|

Maeda et al, 2003 |

Japan |

90 |

13.3 |

qMSP |

II–IV |

54.5 |

— |

Univariate |

|

Shen et al, 2007 |

USA |

182 |

17.0 |

MSP |

IV |

14 |

— |

Univariate |

|

Shima et al, 2011a, |

USA |

902 |

29.8 |

qMSP |

I–IV |

146 |

— |

Multivariate |

|

Veganzones-de-Castro et al, 2012 |

Spain |

318 |

24.8 |

qMSP |

Dukes' A–D |

92 |

75–111 |

Univariate |

| Ward et al, 2003 | Australia | 555 | 23.1 | MSP | I–IV | 32 | 1–60 | Univariate |

Abbreviations: MSP=methylation-specific PCR; qMSP=quantitive MSP.

Study results report and meta-analysis

CDKN2A gene was found to be methylated in 23% of total colorectal cancer patients. The survival data by multivariate analysis can be obtained from three studies (27.3% Table 1). Five of 11 studies (45.5%) revealed that CDKN2A hypermethylation was a poor prognostic factor for survival of patients, and 6 (54.5%) reported that CDKN2A hypermethylation did not have an unfavourable impact on survival.

The individual HRs of the 11 included studies were estimated using the methods reported by Parmar et al (1998). Five of these 11 studies directly provided their HRs. Two studies reported the total number of events and the log-rank statistic or its P-value according to which HRs can be approximated. In the four remaining studies, HRs had to be extrapolated from the graphical representations of the survival distributions.

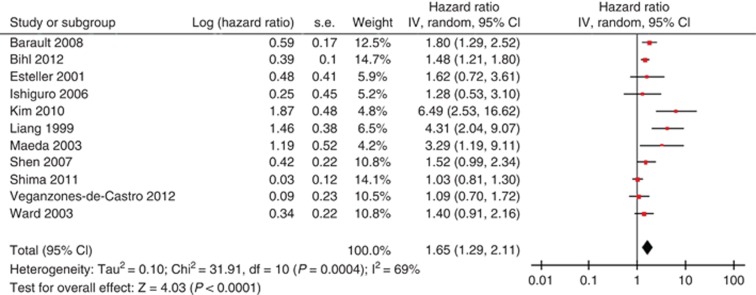

Figure 2 demonstrates a forest plot of the individual HRs and results from the meta-analysis. Overall, CDKN2A hypermethylation in the primary tumour had significant association with an enhanced mortality risk of colorectal cancer patients in the random-effects model (combined HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.29–2.11), despite the exhibition of heterogeneity among studies (I2 69%, P=0.0004). For the exploration of the source of heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were conducted by study location, publication year, number of patients and methylation rate, REMARK score and ELCWP score. Study location was found to be significantly correlated with the inter-study heterogeneity (P=0.008) while other covariates was not (Table 2). Furthermore, subgroup analysis revealed that the significant correlation between CDKN2A hypermethylation and OS was present in Europe (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.28–1.74) and Asia (HR 3.30; 95% CI 1.68–6.46). We also observed the significant association of CDKN2A hypermethylation and OS of patients in studies with REMARK score >12 (HR 1.75, 1.22–2.51), further confirming the prognostic role of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Of note, the pooled HR estimate by multivariate analysis was 1.38 (95% CI: 1.02–1.87), suggesting that CDKN2A hypermethylation might be an independent prognostic factor for patients with colorectal cancer.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of impact of CDKN2A hypermethylation on overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Results are presented as individual and pooled HR, and 95% CI.

Table 2. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis of the studies reporting the association of CDKN2A hypermethylation and overall survival of cancer patients.

| |

|

|

Pooled HRs (95% CI) |

|

Heterogeneity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified analysis | No. of studies | No. of patients | Fixed | Random | Meta-regression P-value | I2(%) | P-value |

| Study location |

|

|

|

|

0.008 |

|

|

| Europe |

4 |

1408 |

1.49 (1.28, 1.74) |

1.49 (1.27, 1.76) |

|

4 |

0.37 |

| Asia |

4 |

393 |

3.32 (2.14, 5.15) |

3.30 (1.68, 6.46) |

|

56 |

0.08 |

| USA |

2 |

1084 |

1.13 (0.92, 1.39) |

1.20 (0.83, 1.74) |

|

59 |

0.12 |

| Oceania |

1 |

555 |

1.40 (0.91, 2.16) |

1.40 (0.91, 2.16) |

|

– |

– |

| Publication year |

|

|

|

|

0.510 |

|

|

| ≥2007 |

6 |

1085 |

1.73 (1.35, 2.21) |

1.85 (1.29, 2.65) |

|

44 |

0.11 |

| >2007 |

5 |

2355 |

1.37 (1.20, 1.56) |

1.52 (1.09, 2.13) |

|

80 |

0.0004 |

| No. of patients |

|

|

|

|

0.226 |

|

|

| <200 |

6 |

661 |

2.14 (1.61, 2.85) |

2.45 (1.46, 4.10) |

|

63 |

0.02 |

| >200 |

5 |

2779 |

1.33 (1.18, 1.51) |

1.34 (1.08, 1.65) |

|

58 |

0.05 |

| Methylation rate (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.592 |

|

|

| <24 |

6 |

1468 |

1.56 (1.33, 1.82) |

1.76 (1.27, 2.43) |

|

57 |

0.04 |

| >24 |

5 |

1972 |

1.31 (1.11, 1.56) |

1.57 (1.03, 2.39) |

|

78 |

0.001 |

| REMARK score (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.770 |

|

|

| <12 |

5 |

1001 |

1.54 (1.19, 2.00) |

1.54 (1.19, 2.00) |

|

0 |

0.65 |

| >12 |

6 |

2439 |

1.42 (1.25, 1.61) |

1.75 (1.22, 2.51) |

|

83 |

0.0001 |

| ELCWP score (%) |

|

|

|

|

0.279 |

|

|

| <66 |

6 |

1399 |

1.64 (1.40, 1.92) |

1.92 (1.36, 2.70) |

|

57 |

0.04 |

| >66 | 5 | 2041 | 1.24 (1.05, 1.47) | 1.45 (1.01, 2.08) | 73 | 0.006 | |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.

In addition, we assessed the association between CDKN2A hypermethylation and clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer patients. As indicated in Table 3, CDKN2A hypermetylation had a significant association with lymphovascular invasion (positive vs negative: OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.15–2.47), lymph node metastasis (positive vs negative: OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.09–2.59) and tumour location (proximal vs distal: OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.34–3.26). The meta-analysis of the correlation between CDKN2A hypermethylation and lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, Duke's stage and tumour size did not exhibit inter-study heterogeneity (I2 0%), whereas the analysis of other clinicopathological parameters exhibited heterogeneity (I2 51–92%).

Table 3. Meta-analysis of the association between CDKN2A hypermethylation and clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer.

| |

|

|

Pooled OR (95%CI) |

|

Heterogeneity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratification of CRC | No. of studies | No. of patients | Fixed | Random | P-value | I2(%) | P-value |

| Gender |

6 |

2369 |

1.31 (1.09, 1.58) |

1.27 (0.94, 1.71) |

0.12 |

51 |

0.07 |

| Stage of disease |

3 |

1168 |

1.24 (0.95, 1.62) |

1.63 (0.84, 3.16) |

0.14 |

65 |

0.06 |

| Dukes' stage |

2 |

406 |

1.49 (0.94, 2.35) |

1.49 (0.94, 2.35) |

0.09 |

0 |

0.51 |

| Lymphovascular invasion |

3 |

784 |

1.68 (1.15, 2.47) |

1.68 (1.15, 2.47) |

0.008 |

0 |

0.89 |

| Lymph node metastasis |

2 |

496 |

1.68 (1.09, 2.59) |

1.68 (1.09, 2.59) |

0.02 |

0 |

0.99 |

| Grade of differentiation |

7 |

2597 |

0.55 (0.42, 0.72) |

1.23 (0.39, 3.83) |

0.72 |

92 |

<0.00001 |

| Mucinous type |

4 |

1379 |

1.36 (0.94, 1.94) |

0.98 (0.35, 2.71) |

0.97 |

82 |

0.001 |

| Tumour location |

7 |

2616 |

2.68 (2.23, 3.23) |

2.09 (1.34, 3.26) |

0.001 |

77 |

0.0002 |

| Tumour size | 2 | 369 | 1.08 (0.56, 2.09) | 1.07 (0.54, 2.10) | 0.81 | 0 | 0.32 |

Abbreviations: CRC=colorectal cancer; CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

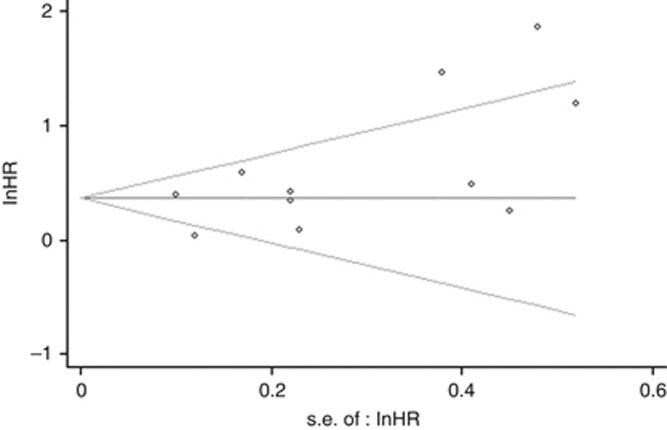

Sensitivity analysis revealed that omitting any single study did not affect the pooled HR significantly. The evaluation of publication bias indicated that the Egger test reached the significance (P=0.063<0.1) for studies involved in the analysis of OS. The funnel plots for publication bias also demonstrated a certain degree of asymmetry (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for the evaluation of potential publication bias in the impact of CDKN2A hypermethylation on overall survival of colorectal cancer patients.The funnel graph plots the log of HR against the standard error of the log of the HR (an indicator of sample size). The circles indicate the individual studies in the meta-analysis. The line in the centre represents the pooled HR. The Egger test for publication bias was significant (P=0.063<0.1).

Discussion

Although promoter methylation of a number of tumour suppressors (e.g., RASSF1A, MGMT) have been studied for their prognostic value in colorectal cancer patients recently, the identification of an epigenetic marker with established predictive value for survival of colorectal cancer patients remains a issue that needs to be addressed (Shima et al, 2011b; Chen et al, 2012). CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation been found to lead to silencing of the tumour-suppressor CDKN2A gene, which might further result in the development, progression and invasion of colorectal cancer, and could be associated with poor prognosis of patients (Tada et al, 2003; Rayess et al, 2012). Despite an increasing number of studies performed on promoter status of CDKN2A gene, there is still controversy over the prognostic value of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. We thus conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether CDKN2A hypermethylation could predict the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients.

This study aggregated the outcomes of 3440 colorectal cancer patients from 11 individual trials, revealing that CDKN2A hypermethylation is a significant predictor for poor OS of colorectal cancer patients (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.29–2.11). The significant association between CDKN2A hypermethylation and OS of patients was also present in the analysis of studies following REMARK guidelines more rigorously (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.22–2.51), further confirming the prognostic role of CDKN2A hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Moreover, the significant associations were exhibited between CDKN2A hypermethylation and clinicopathological parameters such as lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastasis.

In addition, CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation was also found to have a significant correlation with proximal tumour location. Various environmental and genetic factors contribute to carcinogenesis and progression of colorectal cancer while their roles are different for proximal and distal tumours. Increasing evidence has shown that CpG island methylator phenotypes (CIMPs) and microsatellite instability are associated with proximal tumours while chromosomal instability with distal tumours (Iacopetta, 2002). This distinction might lead to the different sensitivities of proximal and distal tumours to fluorouracil-based chemotherapy and thus different management options for the tumours in the two locations (Elsaleh et al, 2000).

A significant heterogeneity of the included studies was observed in this systematic review except for the analysis of studies on OS in Europe. In sensitivity analysis, omission of any individual study did not reduce the heterogeneity or help to elucidate the source of heterogeneity. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis indicated that study location might account for part of inter-study heterogeneity. Moreover, subgroup analysis indicated that CDKN2A hypermethylation was significantly correlated with poor prognosis of patients in Europe (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.28–1.74) and Asia (HR 3.30, 95% CI 1.68–6.46) while not in other study locations. As the characteristics of colorectal cancer in different regions might differ because of diverse environmental factors and genetic and epigenetic background of human races, the prognostic value of biomarkers such as CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation in colorectal cancer might be different among different study locations. However, the pooled analysis of all included studies from different regions in this meta-analysis indicated an overall predictive role of CDKN2A hypermethylation for poor survival in colorectal cancer patients. More multicenter studies might further clarify whether CDKN2A serves as a prognostic factor for colorectal cancer patients worldwide.

As for the detection of methylation status of CDKN2A promoter in tumour tissues, the studies included in this meta-analysis used either MSP that is a semi-quantitative approach or qMSP that is a quantitative approach. Moreover, the studies did not apply the same PCR primers and the CDKN2A promoter regions examined for methylation status was also not always uniform, leading to a potential bias because the sensitivity and specificity of MSP or qMSP might depend on the primers used, regions detected and other PCR conditions. Subgroup analysis was not possible to be conducted to address this technical issue, because the small groups of studies used the same primers and other PCR conditions. Furthermore, owing to the fact that an optimal threshold has not been defined for qMSP or pyrosequencing, the cutoff defining a colorectal cancer with CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation is not identical, which might also potentially generate a certain degree of heterogeneity.

The approach of extrapolating the HRs from studies was also a potential factor that might lead to bias. If HRs were not directly provided by the studies, we calculated them according to the data reported in the publications or estimated them by extrapolating the information from the survival curves. Although two of the investigators (XX and CW) extracted the survival rates according to the graphical representation of the survival curves, this did not completely rule out inaccuracy during reading the survival rates. The estimated HRs might thus be not as reliable as those retrieved directly from reported statistics. However, we compared our estimated HRs and 95% CIs with the results reported in papers and did not identify any major deviation of our results from the results available in the publications.

Egger tests and funnel plots exhibited a certain degree of publication bias for the analysis of association between CDKN2A methylation and OS. As known, studies that did not possess statistically significant results are less frequently published, and even if these results are published, they are more frequently reported in a brief way and not easily available for analysis. It should be also noted that the positive studies are more frequently published in English language, while those negative ones tend to be more often published in native languages (Egger et al, 1997b). This analysis only included fully published studies in English, whereas unpublished studies and conference abstracts were not enrolled, because the data that can be used for methodological evaluation and meta-analysis were only available in full published studies. Moreover, studies that did not report sufficient data for estimation of HRs were ruled out from this systematic review, and this might potentially generate bias. However, we conducted a complete literature search through the above databases for the eligible studies to minimise the possible bias, and the large sample of colorectal cancer patients (n=3440) enrolled in this analysis ensures the reliability and stability of the results.

In addition, CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation is a frequent epigenetic event, and is often included in the panel of genes for the assessment of the CIMP in colorectal cancer. Several studies in this meta-analysis included the analysis on the prognostic value of CIMP, which included CDKN2A, hypermethylation and other gene methylations (Ward et al, 2003; Shen et al, 2007; Barault et al, 2008; Kim et al, 2010; Shima et al, 2011a). Whereas, these studies usually applied the CIMPs comprising various gene patterns different among studies, which might lead to the difficulty of direct comparison and could generate more heterogeneity if the data were pooled. Therefore, more homogenous studies on the association between identical CIMP and cancers are needed in the future to allow for the meta-analysis on the prognostic value of CIMP in colorectal cancer.

To sum up, this meta-analysis indicated that CDKN2A hypermethylation was significantly associated with poor OS as well as lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and proximal tumour location in colorectal cancer. CDKN2A hypermethylation might be a predictive factor of poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer particularly in Europe and Asia, and might predict invasion and metastasis. However, more prospective studies with homogeneity are needed to further confirm the results in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81000887); Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20090171120064); and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (B2010077).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, de la Vega MF, Martin L, Roignot P, Rat P, Bouvier AM, Laurent-Puig P, Faivre J, Chapusot C, Piard F. Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8541–8546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihl MP, Foerster A, Lugli A, Zlobec I. Characterization of CDKN2A(p16) methylation and impact in colorectal cancer: systematic analysis using pyrosequencing. J Transl Med. 2012;10:173. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SP, Wu CC, Huang SY, Kang JC, Chiu SC, Yang KL, Pang CY. β-Catenin and K-ras mutations and RASSF1A promoter methylation in Taiwanese colorectal cancer patients. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:1277–1281. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draht MX, Riedl RR, Niessen H, Carvalho B, Meijer GA, Herman JG, van Engeland M, Melotte V, Smits KM. Promoter CpG island methylation markers in colorectal cancer: the road ahead. Epigenomics. 2012;4:179–194. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997a;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Zellweger-Zähner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet. 1997b;350:326–329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaleh H, Joseph D, Grieu F, Zeps N, Spry N, Iacopetta B. Association of tumour site and sex with survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:1745–1750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M, González S, Risques RA, Marcuello E, Mangues R, Germà JR, Herman JG, Capellà G, Peinado MA. K-ras and p16 aberrations confer poor prognosis in human colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:299–304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:403–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro A, Takahata T, Saito M, Yoshiya G, Tamura Y, Sasaki M, Munakata A. Influence of methylated p15 and p16 genes on clinicopathological features in colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1334–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JC, Choi JS, Roh SA, Cho DH, Kim TW, Kim YS. Promoter methylation of specific genes is associated with the phenotype and progression of colorectal adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1767–1776. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0901-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang JT, Chang KJ, Chen JC, Lee CC, Cheng YM, Hsu HC, Wu MS, Wang SM, Lin JT, Cheng AL. Hypermethylation of the p16 gene in sporadic T3N0M0 stage colorectal cancers: association with DNA replication error and shorter survival. Oncology. 1999;57:149–156. doi: 10.1159/000012023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Kawakami K, Ishida Y, Ishiguro K, Omura K, Watanabe G. Hypermethylation of the CDKN2A gene in colorectal cancer is associated with shorter survival. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:935–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Br J Cancer. 2005;93:387–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 (7:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayess H, Wang MB, Srivatsan ES. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1715–1725. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, Levin TR, Sweeney C, Murtaugh MA, Wolff RK, Slattery ML. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:837–845. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steels E, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, Branle F, Lemaitre F, Mascaux C, Meert AP, Vallot F, Lafitte JJ, Sculier JP. Role of p53 as a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:705–719. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Catalano PJ, Benson AB, 3rd, O'Dwyer P, Hamilton SR, Issa JP. Association between DNA methylation and shortened survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6093–6098. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima K, Nosho K, Baba Y, Cantor M, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Prognostic significance of CDKN2A (p16) promoter methylation and loss of expression in 902 colorectal cancers: cohort study and literature review. Int J Cancer. 2011a;128:1080–1094. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima K, Morikawa T, Baba Y, Nosho K, Suzuki M, Yamauchi M, Hayashi M, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. MGMT promoter methylation, loss of expression and prognosis in 855 colorectal cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2011b;22:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9698-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T, Watanabe T, Kazama S, Kanazawa T, Hata K, Komuro Y, Nagawa H. Reduced p16 expression correlates with lymphatic invasion in colorectal cancers. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1756–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veganzones-de-Castro S, Rafael-Fernández S, Vidaurreta-Lázaro M, de-la-Orden V, Mediero-Valeros B, Fernández C, Maestro-de las Casas ML. p16 gene methylation in colorectal cancer patients with long-term follow-up. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2012;104:111–117. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082012000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RL, Cheong K, Ku SL, Meagher A, O'Connor T, Hawkins NJ. Adverse prognostic effect of methylation in colorectal cancer is reversed by microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3729–3736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27:335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]