Abstract

Despite generally lower socioeconomic status and worse access to healthcare, Latinos have better overall health outcomes and longer life expectancy than non-Latino Whites. This “Latino Health Paradox” has been partially attributed to healthier cardiovascular (CV) behaviors among Latinos. However, as Latinos become more acculturated, differences in some CV behaviors disappear. This study aimed to explore how associations between acculturation and CV behaviors among Latinos vary by country of origin. Combined weighted data from the 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) were used to investigate associations between acculturation level and CV behaviors among Latinos by country of origin. Among all Latinos, increased acculturation was associated with more smoking, increased leisure-time physical activity, and greater consumption of fast foods, but no change in fruit/vegetable and less soda intake. These trends varied, however, by Latino sub-groups from different countries of origin. Country of origin appears to impact associations between acculturation and CV behaviors among Latinos in complex ways.

Keywords: Acculturation Cardiovascular behaviors Latinos Country of origin

Background/Introduction

In 2010, Latinos comprised about 48 million (15.5%) of the US population. With 50% of recent population growth attributable to Latinos, that figure is expected to exceed 100 million (about 25%) by 2050 [1]. The US Latino population is extremely diverse in terms of socioeconomic status (SES) and culture, much of which is determined by country of origin. While approximately three-fourths of US Latinos are of Mexican (66%) or Puerto Rican (9%) origin, the remaining quarter represent nearly 20 countries [2].

Despite socioeconomic diversity among Latinos, they are more than twice as likely to live in poverty compared with non-Latino White (52% vs. 23.6%, respectively), and nearly three times more likely to lack health insurance (35% vs. 12%, respectively) [3]. Nevertheless, Latinos enjoy better overall health outcomes and longer life expectancy, an observation that has been termed the “Latino Health Paradox” [4, 5]. Although the Latino Health Paradox is still not entirely understood, many have posited that—along with factors such as selective migration of healthier Latinos to the US [5]—the phenomenon is at least partially attributable to Latinos having relatively favorable health behavior profiles [4–6]. Compared with non-Latino Whites, Latinos are less likely to smoke, and more likely to eat a healthy diet and participate in occupational physical activity [7–9]. Extensive research has demonstrated, however, that as Latinos become more acculturated (acquiring attitudes and behaviors of the “dominant” American culture), they tend to smoke more and eat a less healthy diet [7, 8]. The association between acculturation and physical activity remains less clear, but most evidence points toward more acculturated Latinos engaging in more leisure-time but less occupational physical activity [9].

While many studies have explored associations between acculturation and cardiovascular (CV) risk factors, relatively few have examined the role of country or region of origin in modifying this relationship. Given the political, socioeconomic and cultural diversity of nations in Latin America, country of origin may impact baseline CV behaviors of Latinos in the US, as well as how the acculturation process influences behavior over time [10–12].

The purpose of the present study was to explore how associations between acculturation level and three CV behaviors (smoking, diet, and physical activity) varied by country of origin among Latinos living in the US. First, we hypothesized that the distribution of Latinos by acculturation level would vary based upon country of origin. Second, we hypothesized that the relationship between acculturation level and CV behaviors would be modified by country of origin. Specifically, we expected that among Latinos from countries of origin with disproportionately low levels of acculturation, increasing acculturation would be associated with more dramatic “Americanization” of CV behaviors, and vice versa.

Methods

Data Source

We used cross-sectional combined data from the 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS). The CHIS is a biennial 2-stage random digit-dial telephone survey of non-institutionalized adults in California that interviews one adult in each household sampled. The CHIS gathers information on a wide range of health topics [13]. We excluded from our analysis participants who had their CHIS questions answered by another individual, or proxy. The final sample included 60,638 non-Latinos Whites and 16,000 Latinos.

Exposure Variable: Acculturation

In this study, acculturation was defined as “the acquisition of the cultural elements of the dominant society—language, food choice, dress, music, sports, etc” [9]. To measure acculturation we utilized a 6-item scale adapted from a 7-item acculturation scale developed and validated by Johnson-Kozlow [14] for use with the CHIS. The scale was based upon a unidimensional model of acculturation, in which acquisition of the new culture is assumed to occur in a unidirectional fashion. Continuous acculturation scores were calculated for Latino participants based on data from 6 variables: interview language, primary language used at home, English proficiency, citizenship status, birthplace, and percent of life spent in the US. We excluded from our scale one English proficiency variable used by Johnson-Kozlow because it was a recoded variable (from the question: “Would you say you speak English…?”) that was constructed by recoding the 5 original response options (speak only English, speak English very well, speak English well, do not speak English well, and speak English not at all) into only 3 categories (speak only English, speak English very well, and do not speak English well). We chose to keep the variable with 5 response options, while excluding the recoded variable with only 3 options, because the first variable was more descriptive and because including a second variable based upon the same data would have placed higher weight on English proficiency in our acculturation scale. Raw acculturation scores (ranging from 0 to 23) were scaled to a t-score distribution (mean = 50, SE = 10) and used to separate Latinos at natural breakpoints into 3 approximately equally sized groups of low (n = 4,886), moderate (n = 5,371), and high (n = 5,743) acculturation. The ranges of raw scores for each acculturation group (with t-scores in parenthesis) were: low = 0–10 (31.7–40.7), moderate = 11–17 (42.9–56.3), and high = 18–23 (58.5–60.8).

Outcome Variables: Smoking, Diet, and Physical Activity

Participants were classified as current, former, or never smokers based on 2 CHIS questions. First, participants were asked if they had ever smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime. Those who responded negatively were classified as never smokers. Participants who responded positively to the first question were asked if they smoked cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all, with those who responded “every or some days” designated as current smokers, and “not at all” as former smokers.

Dietary behaviors are evaluated in the CHIS by responses to questions that measure frequency of consumption (number of times per month, week, or day) of the following foods: fruits, vegetables, fast food, and soda. The CHIS does not collect information on portion sizes of foods consumed. We combined data for fruits and vegetables to calculate percent achieving 5-a-day recommendations. Data for fast food and soda consumption were tabulated as dichotomous variables (consumption of none vs. one or more daily). If participants needed clarification, soda was defined as “drinks such as Coke or 7-up” and fast food as “food from restaurants such as McDonald's, KFC, Taco Bell, etc.”

The CHIS captures physical activity as number of minutes per week spent in moderate and/or vigorous physical activity. As recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), to convert CHIS data to weighted metabolic equivalents (METs), we multiplied minutes spent in moderate and vigorous activity by 3.3 and 8.0, respectively. Once CHIS data were converted to METs-min and moderate and vigorous activity combined, we categorized individuals as meeting or not meeting the 2007 ACSM recommendations (450-MET-min per week) for aerobic physical activity [15].

Effect Modifier: Country/Region of Origin

Using the UCLA definitions of race and ethnicity, the CHIS asks participants to self-identify their ethnicity as Latino or non-Latino, and then to select the racial group that best describes them [13]. We used responses to both of these questions to include in our analysis the following groups: Latinos (of all racial groups), and non-Latino Whites (the reference group). Latinos were then stratified by self-reported country or region of origin. While Latinos are allowed to select or “write-in” any country of origin, due to limited sample sizes for certain groups the 2005 and 2007 CHIS surveys report data only for the following Latino countries or regions of origin: Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Central America, Puerto Rico, South America, Europe (Spain), other, and 1 + country of origin. The “other” and “1 + country of origin” groups were removed from the analysis due to limited ability to infer about their particular heritage. We also excluded the European (Spanish) group to keep the data Latino-specific. Since Latinos of Guatemalan and Salvadoran heritage were reported separately, the Central American category included Costa Ricans, Hondurans, Nicaraguans and Panamanians. The South American category included Argentines, Bolivians, Chileans, Colombians, Ecuadorians, Paraguayans, Peruvians, Uruguayans and Venezuelans. CHIS data are not reported for Latino countries or regions in the Caribbean (such as Cuba and the Dominican Republic) beyond Puerto Rico, due to small sample sizes of those populations in California.

Statistical Analysis

SAS and SUDAAN statistical software packages were used to perform weighted statistical analysis. Non-Latino Whites and Latinos of low, moderate and high acculturation were described with respect to gender, age, education, income, employment, marital status, and BMI (Table 1). All demographic variables were found to be statistically different (P < 0.0001) between groups and, therefore, were included in the final multivariate analysis reported as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and tests for linear trends.

Table 1.

Demographics by level of acculturation among Latinos living in California

| Demographics | Low acculturation (n = 4,886) | Mod. acculturation (n = 5,371) | High acculturation (n = 5,743) | White non-Latino (n = 60,638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 5,469,491 | N = 5,278,654 | N = 4,855,993 | N = 25,455,913 | |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Men | 50.46 | 52.32 | 49.74 | 48.86 |

| Women | 49.54 | 47.68 | 50.26 | 51.14 |

| Age (mean, SE) | 39.48 (0.21) | 39.42 (0.27) | 37.61 (0.25) | 48.66 (0.07) |

| % education less than HS diploma | 73.17 | 31.51 | 10.78 | 5.41 |

| Household income in USD (mean, SE) | 23,064 (350) | 47,103 (727) | 64,008 (925) | 86,901 (417) |

| % unemployed and looking for work | 3.31 | 6.12 | 5.03 | 2.16 |

| % married or living with partner | 73.58 | 62.33 | 54.28 | 64.60 |

| BMI (mean, SE) | 28.41 (0.14) | 27.46 (0.12) | 27.83 (0.14) | 26.25 (0.03) |

P-values for difference between acculturation groups for all variables above were < 0.0001

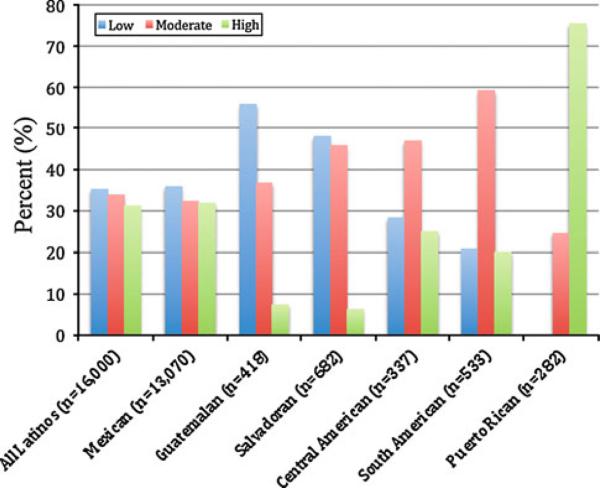

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the distribution of acculturation levels for all Latinos and each Latino sub-group (Fig. 1). Using non-Latino Whites as the reference group (OR = 1), adjusted ORs were calculated by level of acculturation and country/region of origin for the following CV behaviors: never having smoked, consuming 5 + fruits/vegetables per day, consuming any daily fast food and soda, and meeting 2007 ACSM physical activity recommendations. Finally, to measure the significance (P < 0.05) of the observed trends in ORs reported by acculturation level for each Latino sub-group, we constructed special contrasts that test for linear trends within the adjusted logistic regression models and report the P-value for each test.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of acculturation levels (Low acculturation: raw score = 0–10 (t-score = 31.7–40.7); Moderate acculturation: raw score = 11–17 (t-score = 42.9–56.3); High acculturation: raw score = 18–23 (t-score = 58.5–60.8)) by country/region of origin among Latinos in California

Results

Level of Acculturation by Country/Region of Origin

The distribution between low, moderate, and high acculturation levels for all Latinos was roughly one-third in each group (Fig. 1), with the Mexican group mirroring data for all Latinos. The Guatemalan (55.93%) and Salvadoran (47.94%) samples were skewed toward low acculturation, while the Central (46.84%) and South (59.3%) American samples were concentrated in the moderate acculturation range. The Puerto Rican sample was skewed toward high acculturation, with 75.44% in that group and no participants reporting low acculturation.

Acculturation and CV Behaviors Among all Latinos

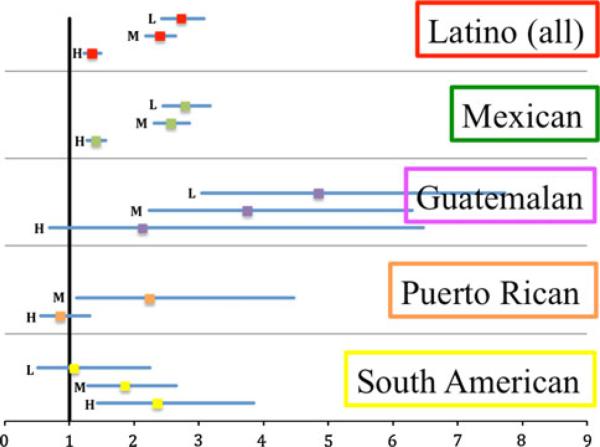

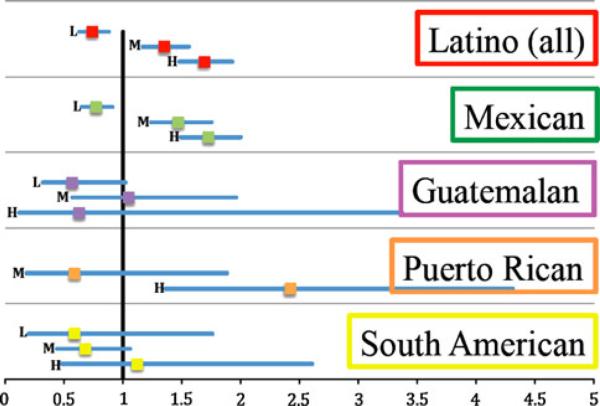

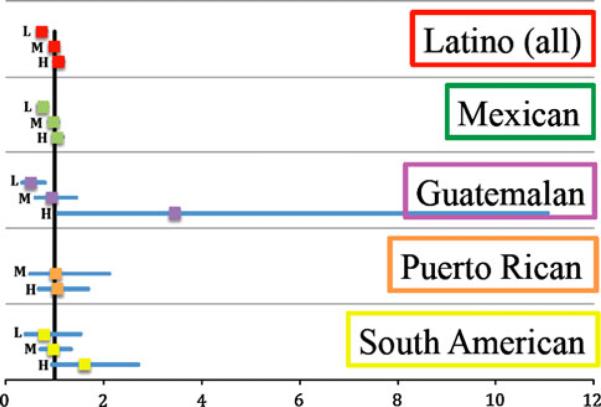

Among all Latinos, increased acculturation level was associated with higher smoking rates (P < 0.0001). Adjusted ORs (with 95% CIs) of being a never smoker were 2.73 (2.43–3.08), 2.40 (2.18–2.64), and 1.35 (1.23–1.49) for the low, moderate, and high acculturation groups, respectively (Fig. 2). Dietary data for all Latinos showed increased acculturation level was associated with more consumption of fast food (P < 0.0001). Adjusted ORs of consuming any daily fast food were 0.74 (0.63–0.88), 1.35 (1.17–1.56), and 1.69 (1.48–1.93) for the low, moderate, and high acculturation groups, respectively (Fig. 3). We found no observable trends by acculturation level in the odds of meeting 5-a-day fruit and vegetable consumption recommendations among all Latinos. Conversely, among all Latinos increased acculturation level was associated with decreased soda consumption (P < 0.0001), with the adjusted ORs of consuming any daily soda being 1.74 (1.54–1.96), 1.60 (1.46–1.75), and 1.40 (1.27–1.54) for the low, moderate, and high acculturation groups, respectively. Finally, among all Latinos increased acculturation was associated with an increase in leisure-time physical activity (P = 0.0001). Adjusted ORs of meeting ACSM physical activity recommendations were 0.74 (0.66–0.83), 0.99 (0.91–1.07), and 1.08 (0.99–1.18) for the low, moderate, and high acculturation groups, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted (The adjusted ORs presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4 are adjusted for all demographic variables shown in Table 1 (gender, age, education, household income, employment and marital status, and BMI)) ORs (with 95% CIs) of being a never smoker for low, moderate, and high acculturation levels by country/region of origin (The reference group for adjusted ORs in Figs. 2, 3, 4 is non-Latino Whites (OR = 1)). L low acculturation (raw score: 0–10, t-score: 31.7–40.7), M moderate acculturation (raw score: 11–17, t-score: 42.9–56.3), H high acculturation (raw score: 18–23, t-score: 58.5–60.8) *Note: There were no Puerto Ricans with a low acculturation score

Fig. 3.

Adjusted ORs (with 95% CIs) of consuming any daily fast food for low, moderate, and high acculturation levels by country/region of origin. L low acculturation (raw score: 0–10, t-score: 31.7–40.7), M moderate acculturation (raw score: 11–17, t-score: 42.9–56.3), H high acculturation (raw score: 18–23, t-score: 58.5–60.8). *Note: There were no Puerto Ricans with a low acculturation score

Fig. 4.

Adjusted ORs (with 95% CIs) of meeting ACSM physical activity recommendations for low, moderate, and high acculturation levels by country/region of origin. L low acculturation (raw score: 0–10, t-score: 31.7–40.7), M moderate acculturation (raw score: 11–17, t-score: 42.9–56.3), H high acculturation (raw score: 18–23, t-score: 58.5–60.8). *Note: There were no Puerto Ricans with a low acculturation score

Acculturation and Smoking by Country/Region of Origin

Figure 2 is a forest plot of the adjusted ORs (with non-Latino Whites as the reference group, OR = 1) of being a never smoker for low, moderate, and high acculturation by country/region of origin. As seen among all Latinos, increased acculturation was associated with lower odds of being a never smoker among Mexicans (P < 0.0001). We found no significant associations between acculturation and smoking rates among Guatemalans (P = 0.2480), Salvadorans (P = 0.8381), Central Americans (P = 0.1624), and Puerto Ricans (P = 0.4896).1 In contrast, among Latinos of South American origin, smoking rates for those in the low acculturation group were similar to non-Latinos Whites, while increased acculturation was associated with reduced smoking rates (P = 0.0003).

Acculturation and Diet by Country/Region of Origin

Figure 3 shows a forest plot with adjusted ORs of consuming any daily fast food for low, moderate, and high acculturation by country/region of origin. Increased acculturation was associated with more consumption of daily fast food among Mexicans (P < 0.0001), Central Americans (P = 0.0164), and Puerto Ricans (P = 0.0028). However, we found no association between acculturation and fast food consumption among Guatemalans (P = 0.7610), Salvadorans (P = 0.1014), and South Americans (P = 0.7293).

The adjusted ORs of consuming 5-a-day fruits and vegetables did not change significantly by acculturation level among any of the Latino sub-groups (P > 0.05). For all acculturation levels and Latino groups, consumption of 5-a-day fruits and vegetables was either similar to or less than that observed for the non-Latino White reference group.

Increased acculturation was associated with reduced adjusted ORs of daily soda consumption for Mexicans (P < 0.0001). Soda consumption among the other Latino sub-groups was more similar to that of non-Latino Whites, with no significant change by level of acculturation (P > 0.05).

Acculturation and Physical Activity by Country/Region of Origin

Figure 4 displays adjusted ORs of meeting 2007 ACSM physical activity recommendations for low, moderate, and high acculturation by country/region of origin. Increased acculturation was associated with increased odds of meeting ACSM recommendations among Mexicans (P = 0.0043) and Guatemalans (P = 0.0183). However, we found no associations between acculturation and physical activity among Salvadorans (P = 0.0767), Central Americans (P = 0.7212), South Americans (P = 0.0722), and Puerto Ricans (P = 0.7959).

Discussion

As the US Latino population expands dramatically, implications of the Latino Health Paradox will become increasingly important to the overall health of the nation. With substantial prior evidence supporting better overall health outcomes [4] and a recent 2010 CDC report showing longer life expectancy [5] among Latinos compared with non-Latino Whites, the media, researchers, healthcare providers and policy-makers alike will undoubtedly direct increased attention toward this important public health phenomenon.

While we cannot ignore the disparities in SES and access to healthcare that account for the negative side of the Latino Health Paradox [3], the positive side must also be recognized and efforts should target the maintenance of traditionally healthier CV behaviors found among Latinos [4]. Prior research suggests that increased acculturation among Latinos threatens certain public health benefits of the Latino Health Paradox, due to an association between increased acculturation and less healthy, more “Americanized” CV behaviors [4–6]. However, although US Latinos originate from nearly 20 countries of origin, few studies have addressed the impact of country of origin on associations between acculturation and CV behaviors [9–12]. Using data from the CHIS, this study confirmed our overall hypothesis that country/region of origin does impact associations between acculturation and CV behaviors, but also demonstrated that the observed trends are more complex than our sub-hypothesis would suggest.

First, the findings of this study demonstrate Latinos of differing countries/regions of origin exhibit varied levels of acculturation. Typical immigration routes as well as unique socio-political contexts of Latin American nations may influence acculturation profiles of Latino sub-groups living in the US [5, 10–12]. For example, the more traditional and indigenous cultures in Guatemala as compared with other Latin American nations could result in Guatemalans immigrating to the US to be less acculturated. On the other hand, Puerto Rico's status as a US territory and geographical distance from California may play a role in the higher acculturation level found among Puerto Ricans in the state.

Our data support prior research indicating that increased acculturation is associated with higher smoking rates among all Latinos [4, 9, 11]. However, the lack of association between acculturation and smoking found among Guatemalans and Salvadorans contradicts our sub-hypothesis since, among Latinos from these countries of origin with relatively low acculturation levels, the acculturation process did not have a larger impact on “Americanization” of CV health behaviors. Alternatively, among the South American sample, lower acculturation was associated with higher smoking rates, and increased acculturation was associated with reduced smoking. This finding could be attributable to higher rates of smoking observed in South America compared with other Latin American countries. For example, male and female smoking rates are approximately 2 and 9 times higher, respectively, in Chile (41.7 and 30.5%) compared with El Salvador (21.5 and 3.4%) [16].

This study showed that among all Latinos increased acculturation was associated with higher consumption of fast food, a finding that is consistent with prior research [1, 4, 7–9]. We found an opposite trend in soda consumption among all Latinos, however, and no observable trend in consumption of fruits and vegetables by acculturation level. These latter two findings contradict prior research, which has shown increased acculturation among Latinos is typically associated with increased soda [8] and decreased fruit and vegetable consumption [7–10]. It is unclear why data from the 2005 and 2007 CHIS show atypical results in terms of soda and fruit and vegetable intake among all Latinos, but the divergence may be related to the acculturation experience of California Latinos being somehow different than that of the overall US Latino population.

Similar to smoking results, fast food data for the Guatemalan and Salvadoran samples do not support our sub-hypothesis, since these predominantly low acculturation sub-groups showed no association between acculturation level and fast food consumption. Together, these findings suggest Guatemalans and Salvadorans may possess protective cultural factors such as familismo—a perspective in which needs of the family are placed over needs of the individual—that selectively shield against acquiring unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and fast food consumption [5, 6]. Similarly, fast food data for Puerto Ricans also did not support our sub-hypothesis, as this disproportionately high acculturation group exhibited a dramatic rise in fast food consumption with increased acculturation. Due to Puerto Rico's status as a US territory and resultant inflated exposure to “Americanized” customs as compared with other Latin American regions, Puerto Ricans may lack similar protective cultural factors that Guatemalans and Salvadorans enjoy.

We found a small but statistically significant increase in leisure-time physical activity with increased acculturation among all Latinos. Although there exists a debate in the literature as to the extent and direction of this association, our findings are consistent with several studies that report increased leisure-time physical activity to be one of the health benefits of increased acculturation among Latinos [9]. The Guatemalan sample demonstrated the largest significant increase in leisure-time physical activity with increased acculturation, which supports our sub-hypothesis of observing a magnified association between acculturation and acquisition of “Americanized” CV behaviors among disproportionately low acculturation groups. Although prior studies have shown reduced occupational physical activity with increased acculturation among Latinos [7], we were unable to explore this behavior because it was not included in the 2005 and 2007 CHIS surveys.

Our study has several limitations. Primarily, because the sample comprises only Latinos in California, the findings may not be generalizable to the entire US Latino population. Although California has a large and diverse Latino population compared with most US states, due to the composition of California's Latino population and resultant reporting by CHIS important Latino sub-groups such as Dominicans and Cubans were not included in the analysis, while results for Central and South Americans were limited to region of origin [13]. In addition, the large CIs observed for ORs of certain Latino sub-groups (e.g., Guatemalans and Puerto Ricans) are at least partially attributable to the small sample sizes of those groups in CHIS. We have attempted to address this limitation through calculating tests for linear trends for each set of ORs and including P-values for the tests to demonstrate which trends achieve or lack statistical significance.

While many researchers have argued for a theoretical shift to employ bidimensional rather than unidimensional models of acculturation, this study was restricted to a unidimensional scale because the CHIS collects only proxy measures of acculturation (i.e., language, citizenship, percent of life spent in US) and is cross-sectional in design [9]. Furthermore, because most CHIS data are retrospective and self-reported, our analysis is subject to both recall and social desirability bias (i.e., participants may underestimate unhealthy behaviors, while overestimating healthy ones). Finally, as a telephone survey, the CHIS may exhibit a selection bias toward more acculturated Latinos owning telephones [14]. Despite the study's limitations, the findings contribute to the limited literature on acculturation and CV behaviors among Latino sub-groups, and suggest complex differences by country or region of origin.

The findings from this study have implications for both clinical practice and future research. First, benefits of the Latino Health Paradox depend upon maintaining certain healthy Latino behaviors (e.g., low smoking rates, healthier diet, and occupational physical activity), with selective “Americanization” of other behaviors such as more leisure-time physical activity [9]. Clinicians should take into consideration the role acculturation may play in impacting CV behaviors among Latinos so they can be both culturally sensitive and effective when counseling their Latino patients about CV risk. Further, this study highlights complex differences between Latino sub-groups in terms of acculturation level and CV behaviors, arguing in favor of practitioners tailoring messages to Latino patients about CV risk according to country or region of origin.

Future research should focus on exploring how country of origin and other factors (e.g., gender, urban vs. rural residence, etc.) influence the Latino Health Paradox at multiple levels, including SES, access to healthcare, CV behaviors, and health outcomes. Large cross-sectional surveys should expand beyond proxy measures of acculturation to include bidimensional scales (e.g., collecting data on reverse and circular migration), as unidimensional models such as that used here present multiple theoretical dilemmas and do not fully capture the diversity of ways in which Latinos acculturate into American society [9]. Finally, funding for prospective studies could allow researchers to investigate potential causality between acculturation and health behaviors among Latinos, rather than simply associations.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Diaz is supported by a grant from the NIH/National Cancer Institute (K07CA106780).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Pérez-Escamilla R. Dietary quality among Latinos: is acculturation making us sick? J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(6):988–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.014. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pew Hispanic Center [Accessed online on 2/13/2011];Country of origin profiles. at: http://pewhispanic.org/data/origins/

- 3.Mead H, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in US health care: a chartbook. [Accessed online on 2/13/11];The Commonwealth Fund. 2008 Mar; at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Chartbooks/2008/Mar/Racial-and-Ethnic-Disparities-in-U-S–Health-Care–A-Chartbook.aspx.

- 4.Abraido-Lanza AF, et al. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation?: implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias E. United States life tables by Hispanic origin. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2010;2(152) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo LC, et al. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J Pers. 2009;77(6):1707–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérez-Escamilla RP, Putnik P. The role of acculturation in nutrition, lifestyle and incidence of type 2 diabetes among Latinos. J Nutr. 2007;137(4):860–70. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.860. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala GX, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(8):1330–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.05.009. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara M, et al. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colon-Ramos U, et al. Differences in fruit and vegetable intake among Hispanic subgroups in California: results from the 2005 California health interview survey. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(11):1878–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.015. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Stable EJ, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1424–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1424. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neighbors CJ, et al. Leisure-time physical activity disparities among Hispanic subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;96(8):1460–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096982. CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Accessed online on 2/13/2011];California Health Interview Survey. at: www.chis.ucla.edu.

- 14.Johnson-Kozlow M. Colorectal cancer screening of Californian adults of Mexican origin as a function of acculturation. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):454–61. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9236-9. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haskell WL, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendations for adults from the American college of sports medicine and the American heart association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. PubMedCrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafey O, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. [Accessed online on 2/13/11];American Cancer Society. (3rd ed.). 2010 at: http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/