Review of myeloperoxidase supporting optimal microbicidal activity in the phagosomes of human neutrophils.

Keywords: innate immunity, host defense, phagosomes, neutrophils

Abstract

Successful immune defense requires integration of multiple effector systems to match the diverse virulence properties that members of the microbial world might express as they initiate and promote infection. Human neutrophils—the first cellular responders to invading microbes—exert most of their antimicrobial activity in phagosomes, specialized membrane-bound intracellular compartments formed by ingestion of microorganisms. The toxins generated de novo by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase and delivered by fusion of neutrophil granules with nascent phagosomes create conditions that kill and degrade ingested microbes. Antimicrobial activity reflects multiple and complex synergies among the phagosomal contents, and optimal action relies on oxidants generated in the presence of MPO. The absence of life-threatening infectious complications in individuals with MPO deficiency is frequently offered as evidence that the MPO oxidant system is ancillary rather than essential for neutrophil-mediated antimicrobial activity. However, that argument fails to consider observations from humans and KO mice that demonstrate that microbial killing by MPO-deficient cells is less efficient than that of normal neutrophils. We present evidence in support of MPO as a major arm of oxidative killing by neutrophils and propose that the essential contribution of MPO to normal innate host defense is manifest only when exposure to pathogens overwhelms the capacity of other host defense mechanisms.

Introduction

The immune response required to control microbial invasion involves orchestration of many cell types and antimicrobial agents. Redundant and overlapping activities provide a robustness to host defense that copes effectively with most countermeasures mustered by diverse potential pathogens. Neutrophils—the most abundant white blood cells in circulation—are the primary defenders of the innate immune system. These phagocytic cells ingest bacteria into phagosomes where most microbes are killed and digested (Fig. 1). Neutrophils contain a rich supply of the green heme enzyme MPO, which in combination with H2O2 and chloride, constitutes a potent antimicrobial system [2]. In spite of its powerful antimicrobial action in vitro, it is frequently argued that MPO is not important for microbial killing by neutrophils and at best, serves a redundant function, easily substituted by other killing mechanisms. These conclusions are based on observations that most individuals with MPO deficiency have few infectious problems. It has also been proposed [3], although subsequently challenged [4, 5], that MPO serves only to eliminate oxidants generated as an inadvertent byproduct of antimicrobial responses of neutrophils. In this review, we counter that view with compelling evidence that neutrophils use MPO as a major defender against myriad bacteria. Biochemical data demonstrate that MPO generates by far the most lethal antimicrobial toxins that neutrophils can harness and that the enzyme is active inside phagosomes where it produces oxidants that react with ingested bacteria. Many species of bacteria are killed slowly by neutrophils that lack MPO, and MPO KO mice succumb to large bacterial inoculations that normal mice handle with ease. Although humans deficient in MPO generally enjoy good health, they can incur serious and unusual infections, particularly if other elements of immunity are compromised, as occurs in diabetes. We present evidence in support of MPO as a major arm of oxidative killing by neutrophils. We also propose that at low levels of exposure to pathogens, MPO is not essential to prevent infections, as other antimicrobial agents easily foil invasion. The vital role of MPO in innate host defense will manifest only when exposure to pathogens overwhelms the capacity of other host defense mechanisms.

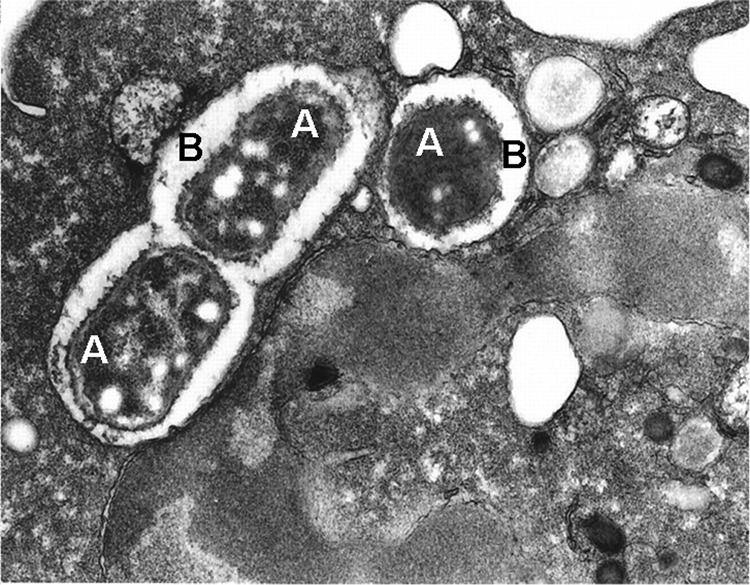

Figure 1. Phagocytosis of bacteria by a neutrophil.

A thin section electron micrograph of a single neutrophil with three Escherichia coli (A), visible within two phagocytic vacuoles (B). Reprinted from ref. [1].

A BRIEF HISTORY

MPO has sparked the curiosity of scientists for nearly 150 years. Initially, the distinctive green tinge that it gives pus and phlegm captured the attention of Edwin Klebs, of Klebsiella pneumoniae fame. He found that an extract from the guaiacum plant turned blue when mixed with pus and concluded that the leukocytes in pus must contain an oxidase. Georges Linossier [6], however, added H2O2 to the mix and elicited more intense color development. The Frenchman realized that the enzyme was in fact a peroxidase, using H2O2 to oxidize the polyphenol guaiaconic acid to an intensely colored, highly conjugated quinone. Cytochemical studies dating back to the early 1900s suggested the presence of a peroxidase in the cytoplasmic granules of some neutrophils. This peroxidase is now known to be present in human, simian, and canine neutrophils, among others, at very high levels [7]. Kjell Agner [8, 9] first isolated the peroxidase from canine pus in the early 1940s and named the enzyme verdoperoxidase because of its intense green color. However, Theorell and Akeson [10] changed the name to “myeloperoxidase” to reflect its myeloid origin and to distinguish it from the green-brown lactoperoxidase purified from milk. In 1960, James Hirsch and Zanvil Cohn [11] described in detail a degranulation process in phagocytes in which the membranes of cytoplasmic granules fuse with the phagocytic compartment (phagosome). The common membrane ruptured, and the contents of the granules were discharged into the phagosome. Cohn and Hirsch [12] then isolated granules from rabbit granulocytes and showed that they contain several hydrolases as well as an antimicrobial protein that Hirsch called phagocytin [13]. The concept that granule components are released into the phagosome to kill ingested organisms was thus born. Subsequent studies indicated that one of the granule enzymes discharged into the phagosome by human neutrophils was MPO [14], that the neutrophil was capable of halogenating ingested bacteria in the presence of radiolabeled iodide [15], and that an isolated MPO/halide system is potently microbicidal [2, 16].

ENZYMOLOGY OF MPO

When neutrophils encounter opsonized microbes, they ingest them into phagosomes, undergo a burst of oxygen consumption, and release proteins from granules into the phagosomal space. MPO accounts for ∼5% of total neutrophil protein and is a major granule constituent. The enzyme responsible for the oxygen consumption is a NADPH oxidase complex. It assembles primarily in the phagosomal membrane and channels electrons from NADPH in the cytoplasm across the membrane to oxygen, generating superoxide anions within the phagosome. As this electron transfer creates a charge imbalance that would otherwise depolarize the membrane, NADPH oxidase activity is accompanied by activation of a voltage-gated proton channel [17–19]. Superoxide undergoes dismutation, a reaction that maintains the intraphagosomal pH near neutrality [20], and yields H2O2

MPO oxidizes chloride and other halides (bromide, iodide, and the pseudohalide thiocyanate) to generate their respective hypohalous acids [21–23]. Kinetic studies have shown that chloride and thiocyanate are the most favored [24, 25]. The reaction involves two-electron oxidation of the halide by Compound I (see Fig. 2) with a net reaction of

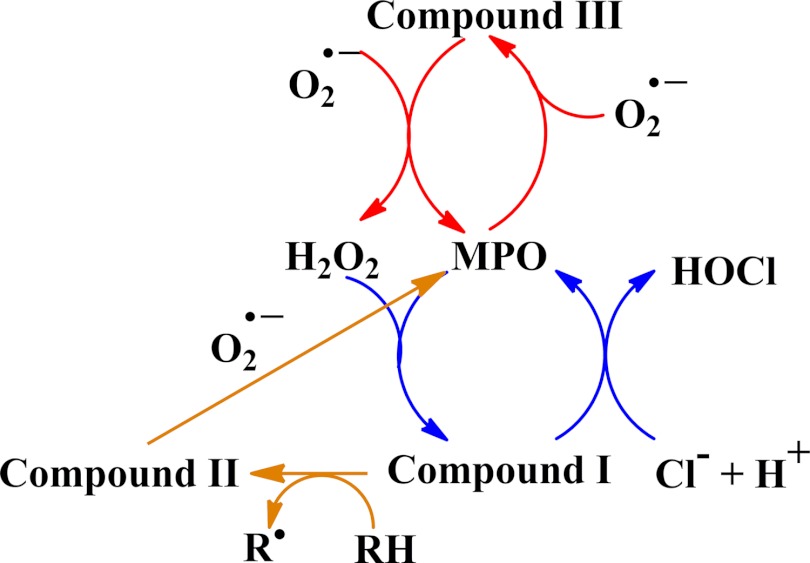

Figure 2. Reactions catalyzed by MPO inside the neutrophil phagosome.

The catalytic activities of MPO that will occur in the phagosome include production of HOCl (blue) and dismutation of superoxide (red). Superoxide should also recycle Compound II formed by reduction of Compound I (orange) and maintain the dominant activities of MPO [28].

HOCl has strong microbicidal properties, and the prevailing view is that chloride is the physiological halide for the MPO-mediated antimicrobial system [26]. (HOCl has a pKa of 7.5 at 30°C, so it exists as a mixture of HOCl and OCl− form at neutral pH. It is here designated as HOCl.) At an extracellular chloride concentration of 122 mM, an intraphagosomal chloride concentration of 73 mM has been measured [27]. This value was obtained with MPO inhibited and does not take into account whether chloride is depleted during the formation of HOCl. If the chloride concentration is maintained, it should allow efficient phagosomal HOCl formation [28].

Peroxidases, including MPO, can catalyze halogenation reactions, whereby a halogen can be incorporated into a biological substrate such as tyrosine. MPO is unique among the animal peroxidases in supporting chlorination of substrates at physiologic pH, a property that serves as a biochemical fingerprint for the presence of enzymatically active MPO in tissue. The presence of chlorinated proteins in atheromatous plaques has been offered as evidence that MPO contributes to the initiation or promotion of a variety of cardiovascular diseases (reviewed in refs. [29, 30]). Very recently, vascular peroxidase 1, the human homologue of the insect protein peroxidasin, has been identified in cardiac and vascular tissue [31, 32] and has been demonstrated to have the capacity to chlorinate target proteins, albeit much less efficiently than does MPO. Peroxidasin has also been shown to catalyze cross-links between cysteine and lysine residues in type IV collagen to form sulfilimine bonds. The reaction requires the intermediacy of hypohalous acids, which suggests that it does indeed produce these oxidants in vivo [33]. Whether HOCl is responsible for cross-links remains equivocal.

Thiocyanate is readily oxidized by MPO and H2O2 [24, 25]. The product HOSCN is a much weaker oxidant than is HOCl and less microbicidal [34] but can penetrate cell membranes and oxidize intracellular sulfhydryl groups [35]. However, it is difficult to envisage that sufficient thiocyanate could be maintained in the phagosome to support substantial HOSCN production. Iodide is the most effective halide substrate on a molar basis, but its concentration in biological fluids is too low (<0.1 μM) to be a significant substrate. Bromide, at physiological concentrations, is a less-effective substrate than is chloride [36], but neutrophils do produce HOBr at physiological concentrations of chloride and bromide [37]. Also, the decreased levels of 3-bromotyrosine, as well as 3-chlorotyrosine, seen in the peritoneal fluid of MPO-deficient compared with WT mice in a sepsis model imply that some MPO-dependent HOBr formation occurs in vivo [38].

MPO also catalyzes the oxidation of a large number of classic peroxidase substrates, including tyrosine [21, 39]. The mechanism involves an initial reaction of H2O2 with ferric MPO to form Compound I, which is then reduced in a one-electron step to Compound II. A further one-electron reduction of Compound II recycles the ferric enzyme, and in both steps, substrate-free radicals are generated. Although these reactions occur in vivo, no studies have shown that the radical products of MPO contribute to neutrophil antimicrobial activity. Nitrite, for example, is oxidized by MPO/H2O2 to a nitrating species (NO2) that exhibits antimicrobial activity in vitro [40–44]. However, it was not possible to detect nitration reactions in the neutrophil phagosome, even when the cells were suspended in high nitrite-containing medium, implying that nitrite oxidation by MPO may not contribute significantly to neutrophil microbicidal activity [26, 45, 46].

In addition to chloride, superoxide likely reacts with MPO in the phagosome [22, 47]. Concentrations of MPO and superoxide are high [28], and two MPO-catalyzed reactions are likely. Sequential reactions of superoxide with the ferric and Compound III forms of MPO should be responsible for most of the superoxide dismutation, and oxidation of superoxide to oxygen by Compound I should be relevant when the chloride concentration is low. In addition, superoxide should maintain the dominant activities of the enzyme by recycling any Compound II that is formed through the one-electron reduction of Compound I (Fig. 2). On this basis, the most favorable reactions catalyzed by MPO in the phagosome should be dismutation of superoxide and conversion of the H2O2 produced to HOCl.

MPO, HOCl PRODUCTION, AND NEUTROPHIL MICROBICIDAL ACTIVITY

Rapid and sustained antimicrobial action in neutrophils depends on synergistic cooperation among the many toxic agents generated in and delivered to the phagosome [26, 48]. NADPH oxidase activity is required for neutrophils to provide broad-spectrum microbicidal activity. With a Michaelis constant for oxygen of 10 μM [49], the phagocyte NADPH oxidase operates in normal tissues and should be limited by hypoxia only when tissue perfusion or viability is severely compromised. Neutrophils from patients with CGD, which lack a functional NADPH oxidase, kill many microbial species poorly, and patients with the condition suffer from life-threatening infections [50, 51]. Several lines of evidence support H2O2 as the product of the NADPH oxidase required for microbicidal activity. Enzymes such as catalase, which consume H2O2, protect certain organisms from the toxic effect of neutrophils in vitro, staphylococcal strains rich in catalase are more virulent in vivo [52], and the introduction of H2O2 into the cell reverses the microbicidal defect in CGD neutrophils [53–56]. Glucose oxidase, which forms H2O2 and not superoxide, can be used for this purpose, indicating that H2O2 is effective even when the cells remain deficient in superoxide. Furthermore, strains of streptococci, pneumococci, and lactobacilli that generate H2O2 in large amounts are killed efficiently by CGD neutrophils and rarely cause infections in patients with CGD [57–59]. Presumably, these organisms provide neutrophils lacking an endogenous H2O2-generating system with the H2O2 required for their own destruction.

However, the bulk of evidence suggests that under the conditions within the phagosome, H2O2 alone is not a particularly effective microbicidal agent (vide infra) and is much more likely to act via MPO. It is well established that reagent HOCl or HOCl generated by a MPO/H2O2/chloride system is extremely effective at killing a wide range of microorganisms. The questions to be answered in the context of events within neutrophil phagosomes relate to how efficiently HOCl is produced and how extensively it contributes to neutrophil-mediated killing. Neutrophils responding to a soluble stimulus, such as PMA, convert a high proportion of the oxygen consumed in the respiratory burst (reported values of 28–72%) to HOCl [60–62]. In the phagosome, with an estimated concentration in the millimolar range [28, 63], MPO should react with almost all of the H2O2 generated. There is no doubt that HOCl is produced in the phagosomes of human neutrophils. Jiang et al. [64], using phagocytosable particles with fluorescein covalently bound to their surface, detected the conversion of fluorescein to its chlorinated derivative (see Fig. 3). They concluded that the “demonstration that HOCl is produced within phagosomes in sufficient concentrations to kill bacteria on a time scale associated with death constitutes strong evidence in support of a primary role for HOCl in the microbicidal action of neutrophils”. Recent studies using fluorescent probes with good specificity for HOCl have also detected HOCl inside phagocytosing neutrophils [65–70] and show promise for obtaining more quantitative information.

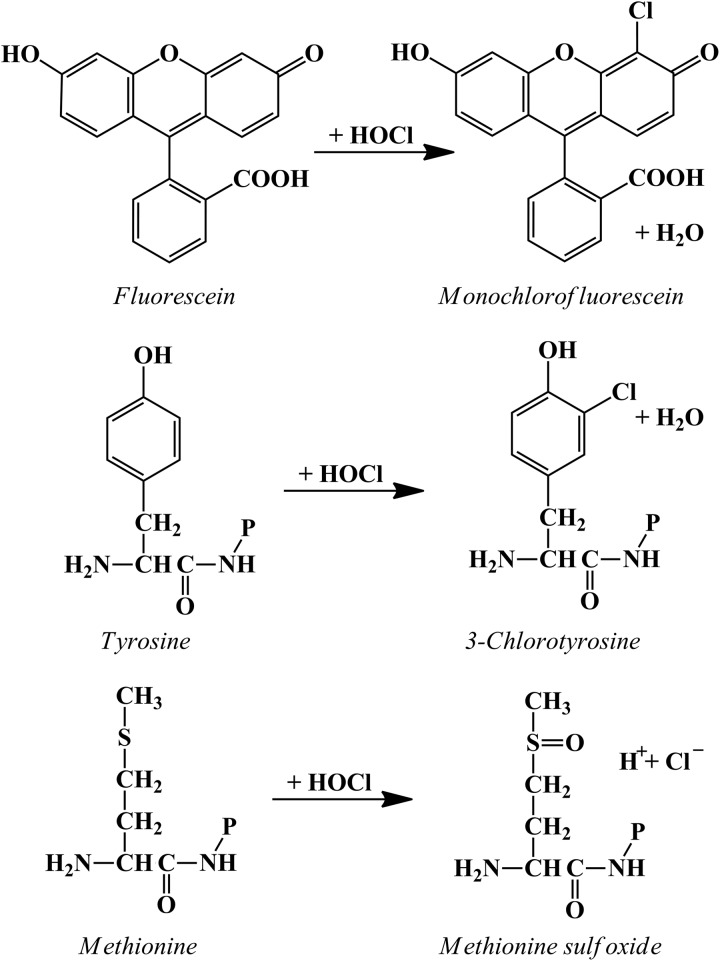

Figure 3. Reactions of HOCl that have been used to demonstrate that MPO is active inside neutrophil phagosomes.

Reactions with tyrosine and methionine are shown for residues on proteins (−P) [45, 62, 72, 73].

The earliest evidence that the product of the MPO-H2O2-halide system attacks the microbe within the phagosome was the MPO-dependent iodination of phagosomal constituents, seen by light and electron microscopic autoradiographic techniques [15]. Measurements of chlorinated tyrosine residues [46, 62, 71] or methionine sulfoxide [72] in proteins have shown more directly that HOCl formed in the phagosome reacts with engulfed bacteria (Fig. 3). Studies of patients with CF are of interest in this regard [71], as the primary defect in CF is a loss of chloride transport as a result of mutations in the CFTR, which acts as a chloride channel. CFTR is present in the phagolysosomes but not the plasma membrane of neutrophils [71]. Neutrophils from patients with CF have a defect in their ability to chlorinate intraphagosomal bacterial proteins [46, 62, 71], leading to the suggestion that chloride must be transported into the phagosome so as not to limit HOCl production.

Neutrophil and bacterial proteins are targets for the HOCl (or reactive iodine) generated during phagocytosis. Indeed, the bulk of chlorination [62] and iodination [74] is detected on neutrophil rather than microbial components. This distribution of halogenated targets is not surprising in view of the very high concentration of released granule proteins that would be targets in the phagosomal environment. The major proportion of neutrophil protein chlorination occurs within the phagosome [75], and granule enzymes are inactivated by oxidants present in the phagosome [76]. Despite the extensive targeting of phagosomal contents for HOCl, several studies have demonstrated that the amount of HOCl detected is in sufficient excess to be microbicidal to the ingested bacterium [68, 72].

One potential consequence of reacting with neutrophil-derived phagosomal constituents is that HOCl could be consumed before reaching the bacterium. With some bacteria, this could be counteracted by binding of MPO to their surface [77–79], although calculations predict that there would be enough sites to bind only a small proportion of phagosomal MPO [28]. Another possible consequence is that secondary products from reactions of HOCl with neutrophil proteins could themselves contribute to microbicidal activity. There is a kinetic hierarchy for the reaction of HOCl with protein [28, 80]. Although halogenation of tyrosine residues is a useful marker, it is a slow reaction that accounts for only a miniscule fraction of the HOCl consumed [81]. Cysteine and methionine residues are most reactive and likely to scavenge most of the HOCl at low concentrations, after which amino groups react, resulting in the production of chloramines [80]. Although chloramine formation in phagosomes has not been shown directly, detection of 3-chlorotyrosine in proteins within phagosomes provides good evidence that chloramines are formed, as the most likely mechanism involves chlorine transfer from juxtaposed chloramine residues [82, 83]. Chloramines are weaker oxidants than is HOCl but retain bactericidal capabilities longer [84, 85]. Furthermore, protein chloramines can decompose to form toxic aldehydes and low molecular-weight chloramines [86–91]. Chloramines and aldehydes are more stable and diffusible than is HOCl and therefore, could contribute to MPO-dependent microbicidal activity. Taken together, it is likely that reactions of HOCl with host proteins in phagosomes do not eclipse antimicrobial action but provide a variety of active species that can extend microbial killing in time and space.

The same hierarchy of targets for HOCl also applies to reactions with bacteria [26]. Tyrosine chlorination will be a minor reaction, and there is no evidence that it per se is toxic. The kinetically more favored reactions with sulfhydryl groups, iron-sulfur centers, and methionines would be expected to precede chlorination and be more important contributors to microbial death. Evidence in support of direct involvement of methionine oxidation is the attenuation of the microbicidal effect of HOCl by bacterial methionine sulfoxide reductases [72].

Products derived from MPO affect aspects of the inflammatory response beyond oxidation and killing of microbes in the phagosome. Extracellular MPO can modify inflammatory mediators. For example, MPO-derived HOCl may regulate proteolytic events at sites of acute inflammation by activating proteases such as matrix metalloproteinase-7 [92] and inactivating protease inhibitors, including TIMP [93] and α-1 antiprotease [94]. As a consequence of these reactions, MPO can create an enhanced proteolytic environment that contributes to liquefaction, necrosis, and abscess formation. Severe neutrophil-mediated lung inflammation has been observed in MPO-deficient mice exposed to zymosan [95], suggesting that in that setting, MPO attenuates lung damage. Furthermore, it was demonstrated recently that MPO KO mice are defective in the oxidation and clearance of single-walled carbon nanotubes from the lungs of these animals, whereas the inflammatory response is more robust than in WT mice [96]. These results provide strong support for two roles of MPO in the inflammatory response, i.e., oxidative degradation of foreign particles and the eventual attenuation of inflammation. MPO may also play a role in the action of neutrophil extracellular traps, the extracellular networks of DNA, histones, and granular proteins, including MPO, which extrude from neutrophils after agonist activation of the cells, trapping extracellular bacteria [97–99].

MPO-DEFICIENT NEUTROPHILS

Biomedical researchers have enjoyed notable success by carefully observing the results of so-called “experiments of nature”, whereby a spontaneous genetic mutation results in a clinical phenotype whose explication provides novel insights into normal biology. For example, investigations in the late 1960s that linked the infectious complications in boys with CGD [100] with the absence of agonist-dependent oxygen consumption by their neutrophils provided the seminal clue to discovery of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase and its contribution to optimal microbicidal activity [101–104].

In 1969, Lehrer and Cline [105] described a diabetic patient with systemic candidiasis and a complete absence of MPO. Until the mid-1970s, the clinical descriptions of patients with MPO deficiency were consistent with the notion that MPO was essential for normal host defense against infection; only 15 patients (in 12 families) had been reported [105–112], many of whom suffered visceral or disseminated infections with Candida, a clinical observation that correlated well with in vitro data (vide infra). Most of the affected patients also had diabetes mellitus, hinting that carbohydrate intolerance or its metabolic consequences may contribute to the compromised host defense observed. However, the introduction of automated flow cytometry to clinical hematology laboratories radically changed recognition of the prevalence of MPO deficiency [113–115]. In contrast to inherited MPO deficiency being a rare occurrence, cytochemistry screening revealed a prevalence of one in 2000–4000 healthy individuals in North America and Europe [116–118], and one in 57,000 in Japan [119]. Furthermore, these data triggered a dramatic revision in the appreciation of the consequences of MPO deficiency. Rather than suffering severe or fatal fungal infections, the vast majority of individuals identified as MPO-deficient through screening large populations is apparently healthy. Case reports have linked MPO deficiency with a variety of clinical disorders, including dermatologic syndromes with or without associated defects in neutrophil chemotaxis [111, 120–122] and disseminated candidiasis in the setting of preeclampsia [123] or prematurity [124], although the causal link with MPO deficiency is lacking. MPO deficiency has also been associated with clinical settings unrelated to host defense against infection, with reports of increased susceptibility to malignant diseases [125–133] and decreased susceptibility to neutrophil-mediated vascular dysfunction [118].

In vitro studies of neutrophils from MPO-deficient subjects complement in vivo observations. The requirement for MPO in the in vitro killing of a variety of organisms by human neutrophils is illustrated in Fig. 4. Data were selected from studies in which MPO-deficient cells were used or the enzyme was inhibited with specific or nonspecific heme poisons. The initial study, showing a marked impairment in the killing of S. aureus by MPO-deficient neutrophils, has been observed repeatedly for several other microorganisms (Fig. 4A) [131]. MPO-deficient neutrophils exhibit a profound defect in candidacidal activity (Fig. 4B). For example, MPO-deficient leukocytes in one study killed 0.1% of ingested C. albicans in 3 h under conditions in which 30% were killed by normal neutrophils [105]. Others observed that the extent of killing at 45 min was only 20% of normal [135]. MPO-deficient neutrophils also kill many bacterial species much more slowly than do normal neutrophils. For example, with the use of Serratia marcescens and S. aureus as test organisms, incubation of bacteria with MPO-deficient neutrophils for 3–4 h was required to induce the same degree of killing as that produced by normal cells in 30–45 min [138]. Other more recent studies have also observed a 60–70% decrease in staphylococcal killing [135, 139] (Fig. 4C). When the the staphylocidal activity of normal, MPO-deficient, and CGD neutrophils was compared (Fig. 4A) [134], MPO-deficient cells exhibited a lag period, following which the organisms were killed, whereas the killing defect in CGD cells remained constant throughout the incubation. It can be concluded from all of these studies that MPO-mediated microbicidal activity predominates during the early postphagocytic period in normal neutrophils. Microbicidal systems independent of MPO kill more slowly but are ultimately effective in MPO-deficient cells. Furthermore, MPO-independent processes in some situations become more effective over time, as observed in Fig. 4A [134].

Figure 4. Impaired bacterial killing by MPO-deficient human neutrophils.

(A) Staphylocidal activity of leukocytes from normal individuals and those with MPO deficiency (MPO-def) or CGD [134]. (B) Bacterial killing, measured as the loss of viable organisms at 30 min, by normal (open bars), CGD (light gray bars), and MPO-deficient (dark gray bars) neutrophils using an optimized method for disruption of bacteria [135]. S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; C. albicans, Candida albicans. (C) Rate constants for killing of S. aureus by neutrophils from an individual with MPO deficiency or those from normal donors in the absence or presence of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), an inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase, or azide and 2-TX, which inhibit MPO [136, 137]. Data have been replotted from the original references.

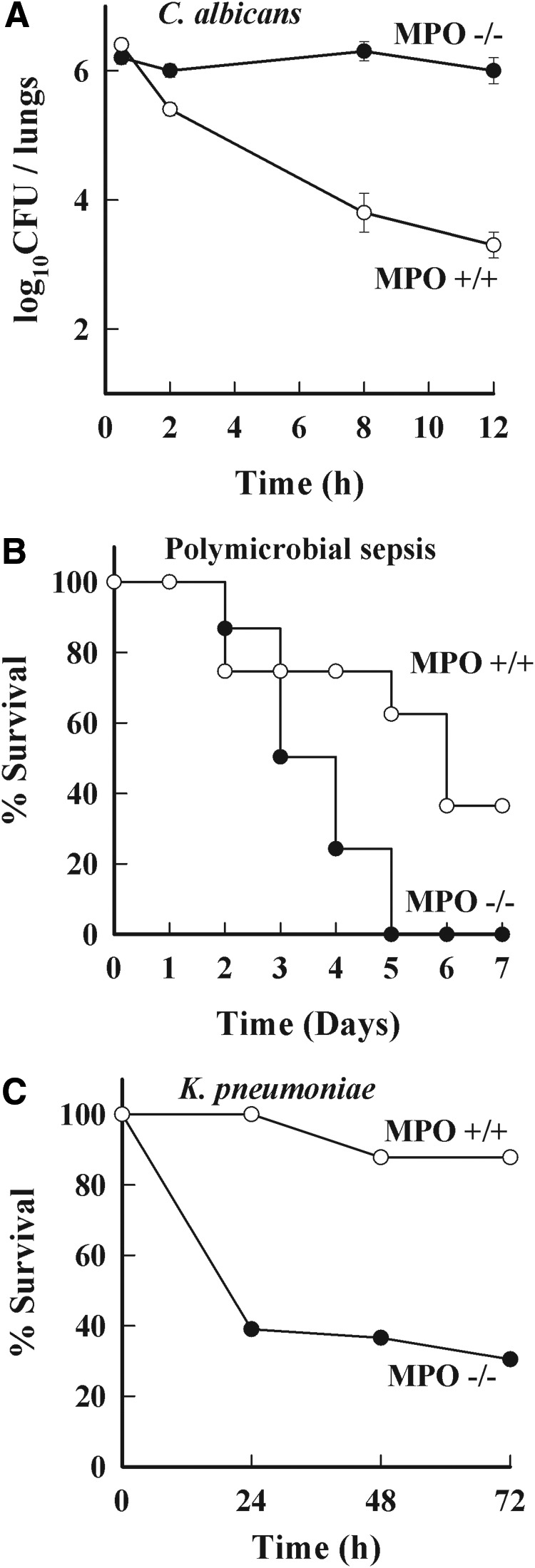

Evidence from nonhuman animals and in vitro studies provides additional insights into how MPO contributes to normal neutrophil biology (Fig. 5). Aratani et al. [140] first reported MPO KO mice and examined their host defenses and neutrophil function [140, 142–149]. MPO-deficient mice have increased susceptibility to intratracheal C. albicans infection, whereas the clearance of i.p. S. aureus is normal [140]. They also are considerably more susceptible than are WT mice to i.p. K. pneumoniae infection [141], to the development of pulmonary infection following the intranasal instillation of certain fungi or bacteria [143, 145], and to intra-abdominal infection by endogenous organisms in the cecal ligation and puncture model [38]. The complex inter-relationships between reactive nitrogen species and ROS becomes manifest in MPO KO mice. The augmented expression of NOS and NO production in MPO-deficient mice results in less sepsis-induced lung injury and death [148], and MPO-deficient mice have diminished endotoxin-induced acute lung injury [95, 149]. In a study comparing the susceptibility to fungal infection with WT, MPO-deficient, and CGD mice, it was concluded that when the fungal load is low, ROS formed by the NADPH oxidase of neutrophils are adequate to control infection in the absence of MPO but that at high fungal load, products of the respiratory burst and MPO are needed [144, 146, 150].

Figure 5. Susceptibility of MPO-deficient mice to infections.

(A) Pulmonary infection with C. albicans in WT (○) and homozygous mutant mice (●). Mice were injected intratracheally with 4.3 × 106 CFU C. albicans. At the indicated times after the challenge, whole lungs were homogenized, and aliquots of the homogenates were plated. Five mice or more were used in each group. Results represent mean ± sd log10 CFU/organ [140]. (B) Mortality was monitored in WT (○) and littermate MPO-deficient mice (●) after inducing sepsis by ligating and puncturing the blind-ended cecum to release intestinal microflora into the abdominal cavity [38]. (C) Mortality rates in MPO-deficient and WT mice in response to i.p. challenge with K. pneumoniae [141]. Data have been replotted from the original references.

It should be emphasized that mice are not humans and that murine models do not always mirror the human situation [39, 151–155]. Mouse neutrophils lack defensins [156], and their MPO level is 10–20% that of human cells [7]. Furthermore, the iNOS system with its associated microbicidal activity appears to be more highly developed in rodent than in human phagocytes and is thus more likely to compensate for the absence of MPO in mice than in humans. Nevertheless, the findings with MPO-deficient mice demonstrate a vital role for MPO in overcoming high exposure to fungi and to some bacterial species.

EFFECTS OF PEROXIDASE INHIBITORS ON NEUTROPHIL MICROBICIDAL ACTIVITY

The importance of MPO in killing by isolated neutrophils is also evident from studies with azide and other peroxidase inhibitors (Fig. 4C). Numerous studies have shown that bactericidal activity of normal neutrophils is strongly inhibited by azide [139, 157–160]. The more specific MPO inhibitors—4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide and 2-TX—have also been shown to decrease the overall killing rate by 60–70% compared with an 80% decrease when the NADPH oxidase is inhibited [136, 137]. Thus, the 1974 conclusion of Koch [159]—that “the azide-sensitive antimicrobial system seems to be by far the most important of many possible systems for the initial inactivation of a number of microorganisms”—still holds true today.

But, do MPO-deficient leukocytes accurately reflect the contribution of MPO to the microbicidal activity of normal cells? Phrased differently, are MPO-deficient neutrophils and normal neutrophils the same in all aspects except the presence of MPO in the latter? Early work by Klebanoff [157] suggests that the answer may be “no”. As well as showing that the three test microorganisms were killed less well by MPO-deficient neutrophils or by normal cells in the presence of azide, this study showed that azide has no effect on the activity of MPO-deficient neutrophils. Furthermore, killing by MPO-deficient neutrophils was more efficient than that of azide-treated normal cells. These results suggest that MPO-deficient cells have increased activity of azide-insensitive, MPO-independent antimicrobial systems and therefore, that conclusions based on the observed microbicidal activity of MPO-deficient cells may underestimate the contribution of MPO to the killing by normal cells. Possible explanations for the enhanced activity include an adaptation of deficient cells to the long-term absence of MPO or an enhanced capacity to induce other antimicrobial systems such as those involving iNOS [148]. In light of MPO-mediated modification of host-derived phagosomal contents, it is also likely that potential antimicrobial agents that are normally inactivated by HOCl and its derivatives retain activity in MPO-deficient neutrophils and thus, contribute to bactericidal action. However, the interpretation of studies of azide-treated normal neutrophils is not straightforward. In some studies, the rate of killing by normal neutrophils treated with azide or 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide was the same as that of MPO-deficient cells [136, 139]. Furthermore, MPO would likely generate azidyl radicals from azide [161, 162], which could selectively inactivate antimicrobial proteins in normal but not in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Additional studies using more specific MPO inhibitors, such as the 2-TX [137], are needed to explain the interesting antimicrobial activities of azide-treated normal neutrophils.

MPO-INDEPENDENT ANTIMICROBIAL SYSTEMS

The evidence discussed above makes a convincing case that MPO provides neutrophils with their most effective mechanism for killing most organisms. However, it is also clear that neutrophils have other antimicrobial activities that need to be considered as alternatives to MPO-dependent killing.

ROS operating in the absence of MPO

The microbicidal activity of MPO-deficient as well as normal neutrophils is inhibited by anaerobiosis [133] or inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity [139], indicating that neutrophils can kill oxidatively in the absence of MPO, albeit much less effectively. The major NADPH oxidase products superoxide and H2O2, acting directly or indirectly, must be responsible for this activity. These species are likely to reach higher-than-normal levels in the phagosomes of MPO-deficient neutrophils, as they would not be consumed by MPO [28] and as NADPH oxidase activity extends for longer in deficient cells [111, 134, 163, 164]. The precise mechanism whereby they kill is incompletely characterized. We consider the various options below.

Superoxide

Superoxide is generally considered to be a sluggish radical that does not have the necessary reactivity to be directly toxic to microbes. In addition, killing of bacteria exposed to extracellular superoxide-generating systems has not been observed. However, superoxide generated intracellularly can be microbicidal [165–169]. Enzymes containing Fe-S clusters are prime targets, and the results are inactivation of the enzymes and release of iron that can generate toxic Fenton reaction products, as discussed below. Although superoxide does not readily pass through membranes, it is proposed from kinetic modeling studies that the phagosomal superoxide concentration is extremely high, reaching ∼25 μM in normal cells and increasing to >100 μM in the absence of MPO [28]. The activity of superoxide at these concentrations has not been tested in any experimental studies, and the possibility that such concentrations could attack sensitive sites and have microbicidal activity warrants evaluation.

H2O2

H2O2 has microbicidal properties but generally exerts direct toxicity only at millimolar concentrations, whereas the H2O2 concentration in the phagosome of normal neutrophils is estimated to be in the low micromolar range [28]. Although the concentration of H2O2 will be greater in the absence of MPO, diffusion through the phagosome membrane would likely limit it to ∼30 μM, and thus, H2O2 would not be expected to exert a direct microbicidal effect [28]. However, H2O2 is considerably more toxic when it is generated continuously rather than being added as a bolus that can be degraded rapidly, and extended exposure to steady-state concentrations in the micromolar range can kill E. coli [170]. Mutants that lack H2O2 scavenging enzymes are even more susceptible. As with superoxide, iron sulfur clusters are sensitive bacterial targets for H2O2, which can also undergo further reaction with the released iron via the Fenton reaction to generate hydroxyl radicals and related reactive species that cause further damage [26, 165]

For example, hydroxyl radicals generated next to the bacterial chromosome may mediate the toxicity to DNA [165]. Ferric ions generated in this process are recycled by reductants supplied through cellular metabolism, allowing Fe to play a catalytic role. Thus, studies with reagent H2O2 demonstrate that low, steady-state concentrations can kill under some circumstances and suggest that H2O2 could contribute to antimicrobial action in the phagosome.

Hydroxyl radical and other secondary oxidants

Although hydroxyl radicals produced inside bacteria may contribute to killing by H2O2, it is unlikely that hydroxyl radical production by neutrophils themselves plays a significant role in their microbicidal activity. There is little evidence that Fenton-like reactions occur in the phagosome, and although hydroxyl radicals can be produced from HOCl and superoxide, this is likely to be a minor reaction [28], and it would not be relevant to MPO deficiency

Furthermore, even if hydroxyl radicals were formed in the phagosomal space, they would be too reactive to diffuse far enough to reach critical microbial targets [171]. Singlet oxygen is another potential microbicide that could theoretically be generated from H2O2 and OCl− [172], but the low H2O2 concentration and neutral pH do not favor its formation in the phagosome. Reports that neutrophils produce ozone must be reassessed because of the nonspecificity of the detectors used [173]. Therefore, none of these secondary oxidants should be relevant in MPO deficiency.

Reactive nitrogen intermediates

NO is formed in relatively large amounts in rat neutrophils [174–177], where it contributes to microbicidal activity. NO-mediated toxicity may be, in part, a result of the nitrosation of microbial or tissue components [178, 179], but in neutrophils, its diffusion-controlled reaction with superoxide is likely to occur, and much of its toxicity may be via peroxynitrite [180]

Peroxynitrite is itself a good oxidant and readily decomposes or reacts with bicarbonate ions to give the more reactive radical species, NO2, ·OH, and carbonate radicals [181]. These reactive nitrogen intermediates have microbicidal properties, in part, through the oxidation of nonprotein and protein sulfhydryl groups [182–185]. NO is consumed by neutrophils [186–188], largely by reaction with superoxide, and peroxynitrite formation by murine neutrophils has been detected [174, 189]. Thus peroxynitrite may contribute to the MPO-independent antimicrobial activity of murine phagocytes. The MPO system in neutrophils may also inhibit NO production through the formation of chlorinated l-arginine, which inhibits all forms of NOS [190].

NO production by human, as opposed to rodent, neutrophils has been controversial [191, 192]. In some studies, NOS [193] and NO production [194] were undetectable, whereas others reported constitutive NOS II expression [195] and NO generation [196–198]. Based on current evidence, it appears that NO production by isolated human neutrophils is very low, but it can be enhanced by exposure to cytokines, chemotactic factors, and various other inflammatory mediators [199–204]. It is also higher in neutrophils isolated from patients with a range of infectious or inflammatory conditions [191, 205–211]. These findings indicate that human neutrophils are more limited than are mouse cells in their capacity to produce NO but imply that it could be formed when the cells are attracted to a site of infection. NO synthesis is not activated by the phagocyte respiratory burst, so it does not necessarily follow that NO and superoxide are generated simultaneously [26]. However, even with constitutive expression, any NO that diffuses into the phagosome should make peroxynitrite and especially in MPO deficiency, could contribute to antimicrobial activity. Further study with appropriately primed MPO-deficient cells is needed to test this hypothesis.

Granule proteins

Assessment of the contribution of granule proteins to the microbicidal activity of phagocytes requires recognition of what constitutes success in the neutrophil phagosome. For an immune response to infection to successfully restore the host to a healthy baseline state, invading agents must be killed and microbial remnants degraded and eliminated. Considered in this context, granule proteins may directly mediate killing of ingested microbes, act synergistically with other granule proteins or oxidants to support killing, degrade microbial proteins or lipids postmortem, or serve multiple roles.

Fusing with nascent phagosomes during phagocytosis, the granules of human neutrophils include a variety of proteins (reviewed in refs. [212, 213]) implicated in the microbicidal activity of phagocytes (reviewed in ref. [214]). Many colocalize with MPO in azurophilic granules and include at least 10 proteins: lysozyme, bactericidal permeability-increasing protein, the α-defensins (human neutrophil defensins 1–4), and the four serine proteases with cidal activity (serprocidins: azurocidin, proteinase-3, cathepsin G, and elastase). In addition, other granules contain cathelicidins, lactoferrin, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, gelatinase, and Group II PLA2 [215]. A cationic protein with chymotrypsin-like esterase activity has been detected in neutrophil granules [216]; however, the microbicidal activity of this protein is not dependent on its proteinase activity, as microbicidal activity is unaffected by heat treatment and the subsequent loss of esterase activity [216, 217] but rather, is dependent on its cationic properties [216–220]. The dissociation of antibacterial action from enzymatic activity is true for many of the seprocidins, including elastase.

The antimicrobial activity of cationic proteins alone is less than that of the MPO system. For example, we compared the staphylocidal activity of a human neutrophil granule cationic protein preparation provided by Inge Olssen with that of the MPO system. Whereas the cationic proteins at a concentration of 50 μg/ml had a small but significant staphylocidal effect after 2 h of incubation, the MPO system, with MPO at 2 μg/ml, was strongly bactericidal at the earliest time-point examined (7.5 min). These findings do not necessarily reflect the relative roles of these systems under other experimental conditions, with other peptide or protein preparations, against other microorganisms, or in the intact cell where oxygen may be limiting and the cationic protein concentration high. However, they do emphasize the relatively greater microbicidal potential of the MPO system against some organisms.

Proteinases

Considerable evidence implicates serine proteinases released from extravasated neutrophils in the damage associated with their tissue infiltration. Do these enzymes also contribute to the intraphagosomal antibacterial activities of neutrophils? Studies of this question began with Aaron Janoff and J. Blondin [221] in the mid-1970s, when they reported that neutrophil elastase at 20 μg/ml lysed the cell walls of autoclaved S. aureus and Micrococcus roseus under conditions in which unheated organisms were unaffected. Further studies with E. coli led to the conclusion that “PMN elastase participates in E. coli digestion once the microbes have been ingested and killed by the leukocytes. Our data do not shed light on the possibility of a direct bactericidal role for this leukocyte enzyme” [222, 223]. Consistent with these observations, Odeberg and Olsson [224] reported that neutrophil elastase at 20 μg/ml was not itself microbicidal to S. aureus or E. coli but did inflict sublethal changes that rendered the organisms more susceptible to the toxic effect of the MPO-H2O2-chloride system and to the chymotrypsin-like cationic protein. More recently, neutrophil elastase was shown to be lethal to K. pneumoniae in association with major morphological changes in the organisms [141, 225]. Furthermore, neutrophil elastase has been reported to degrade the outer membrane protein A of E. coli [226] and to cleave the flagellin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [227]. When interpreting in vitro studies with isolated microbicidal systems, it is important to recognize that these systems operate in the phagosome in the presence of each other and that evolution may have selected for synergies and interactions that we have yet to recognize. Collectively, these data suggest that although proteinases alone are only selectively bactericidal, they act synergistically with the MPO system to promote microbial killing and degradation.

Studies of mice with a genetic absence of elastase and/or cathepsin G have stimulated a re-examination of the role of the serine proteinases elastase and cathepsin G in the microbicidal activity of neutrophils. Mutant mice show increased susceptibility to challenge by some pathogens but normal resistance to others [225]. As there is not much overlap in the vulnerability of the individual mutants, the unifying theme of the studies is that just as with MPO deficiency, elimination of a single neutrophil-defense component leaves the host mostly intact but with a susceptibility to a select subset of potential pathogens. When interpreting mouse models of pyogenic infection, be they WT or MPO-, cathepsin-, or elastase-deficient, it is important to keep in mind that human and murine neutrophils differ in many significant ways [154, 155, 228–230].

Taken together, these studies describe a variety of processes capable of killing microorganisms in the absence of MPO. The contribution that each makes is incompletely defined and varies by organism species and growth state (e.g., Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria) [225]. Nonetheless, all act more slowly than does the MPO system and as illustrated in the KO mice, can be overwhelmed by challenge with a high microbial load.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

When Klebanoff and colleagues discovered the potent microbicidal properties of the MPO, H2O2, plus halide systems, and established that all components were present and active in human neutrophil phagosomes [16, 134, 157], it was concluded that MPO must be a major contributor to host resistance to infection. This view was buttressed by the very high abundance of the enzyme in human neutrophils. MPO abundance and neutrophil kinetic data imply that an uninfected adult must synthesize hundreds of milligrams of enzyme each day, a significant metabolic investment. Finally, reports of individuals found to be genetically MPO-deficient upon evaluation for causes of rare spontaneous, systemic Candida infections seemed to cement the links between MPO deficiency and impaired innate immunity.

The view of the importance of MPO to innate immunity was tempered, however, by discovery of adults with inherited, complete MPO deficiency but unremarkable infectious disease histories. Alternative physiologic roles for MPO, independent of the generation of microbicidal HOCl, were then proposed, although none have, to date, been proven.

MPO systems generating HOCl are quite active in human neutrophils, and despite myriad alternative consumptive pathways, lethal amounts of HOCl reach microbes in the phagosome. It has also been observed that neutrophils deficient in MPO kill many species of pathogenic microbes more slowly than do normal neutrophils and that mice deficient in MPO succumb more readily to certain pathogens than do normal animals. Based on the evidence accumulated over the last one-half century, the process by which neutrophils generate superoxide and then use MPO to convert it to HOCl and bactericidal chloramines is depicted in Fig. 6.

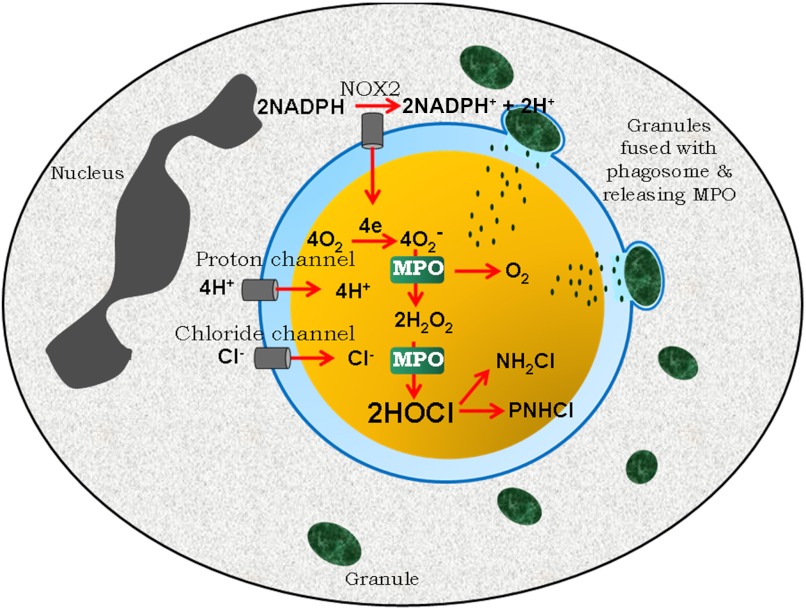

Figure 6. The MPO-mediated antimicrobial system: properties of MPO are well-suited to conditions of the neutrophil phagosome (blue) in the production of microbicidal concentrations of HOCl.

Contact with an ingestible particle triggers assembly from cytoplasmic and intrinsic membrane precursors of a NADPH oxidase (NOX2), which transfers electrons from cytoplasmic (gray) NADPH to dissolved molecular oxygen in the phagosome. A voltage-gated proton channel concurrently allows for transfer of H+ to balance charge and to provide protons for subsequent reactions. Granules (green) containing MPO fuse with the phagosome and release their contents. The superoxide formed by NADPH oxidase is expected to react predominantly with the ferric and Compound III forms of MPO. The net result is efficient dismutation that generates from superoxide and protons, molecular oxygen, and H2O2 in equal amounts. Chloride is available to the phagosome from a combination of pinocytosis during phagocytosis and transport through one or more chloride channels, including the CFTR that is defective in CF patients. MPO then catalyzes the H2O2-mediated oxidation of chloride to form HOCl, which reacts with the bacterium (yellow) or neutrophil proteins to produce cytotoxic chloramines [monochloramine (NH2Cl) and protein chloramine (PNHCl)]. See text for a review of evidence that microbicidal amounts of HOCl can be generated in phagosomes of human PMN.

A persisting question then is why there is such a heavy commitment to daily MPO production for what appears to be a modest increment in host immune defense. Perhaps effective sanitation, ready access to antibiotics, and other hygienic features of modern society have created a sophisticated environment free of the high microbial burdens that the MPO system preferentially targets. Such conditions differ significantly from living conditions in our recent evolutionary past or even present conditions in less-developed areas of the modern world and thus, render MPO-dependent defenses less important.

Resolution of such questions, together with a more detailed understanding of the modifications of microbial metabolism and structure that contribute most to MPO-mediated lethality, remains as an area for further study. Similarly, the complex inter-relationships between oxidants and nonoxidative mediators of microbial killing in the phagosome and how they modify, help, and hinder each other remain as fruitful topics for further inquiry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (A.J.K. and C.C.W.), by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant RO1 AI07958 (W.M.N.), and by support in part from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research Development, 1I01BX000513-01 (W.M.N.).

Footnotes

- 2-TX

- 2-thioxanthine

- CF

- cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CGD

- chronic granulomatous disease

- H2O2

- hydrogen peroxide

- HOBr

- hypobromous acid

- HOCl

- hypochlorous acid

- HOSCN

- hypothiocyanous acid

- KO

- knockout

- NO2

- nitrogen dioxide

- OCl−

- hypochlorite ion

AUTHORSHIP

All authors contributed equally to this work.

DISCLOSURES

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the granting agencies. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Iovine N. M., Elsbach P., Weiss J. (1997) An opsonic function of the neutrophil bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein depends on both its N- and C-terminal domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10973–10978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klebanoff S. J. (2005) Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77, 598–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Segal A. W. (2005) How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 197–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vethanayagam R. R., Almyroudis N. G., Grimm M. J., Lewandowski D. C., Pham C. T., Blackwell T. S., Petraitiene R., Petraitis V., Walsh T. J., Urban C. F., Segal B. H. (2011) Role of NADPH oxidase versus neutrophil proteases in antimicrobial host defense. PLoS One 6, e28149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grimm M. J., Vethanayagam R. R., Almyroudis N. G., Lewandowski D., Rall N., Blackwell T. S., Segal B. H. (2011) Role of NADPH oxidase in host defense against aspergillosis. Med. Mycol. 49 (Suppl. 1), S144–S149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Linossier G. (1898) Contribution a l'etude des ferments oxidants, sur la peroxidase du pups. C. R. Soc. Biol. Paris 50, 373–375 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rausch P. G., Moore T. G. (1975) Granule enzymes of polymorphonuclear neutrophils: a phylogenetic comparison. Blood 46, 913–919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agner K. (1941) Verdoperoxidase. A ferment isolated from leucocytes. Acta Chem. Scand. 2 (Suppl. 8), 1–62 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agner K. (1943) Verdoperoxidase. Adv. Enzymol. 3, 137–148 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Theorell H., Akeson A. (1943) Highly purified milk peroxidase. Arkiv Kemi Mineralogi Geologi 17B, 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirsch J. G., Cohn Z. A. (1960) Degranulation of polymorphonuclear leucocytes following phagocytosis of microorganisms. J. Exp. Med. 112, 1005–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohn Z. A., Hirsch J. G. (1960) The isolation and properties of the specific cytoplasmic granules of rabbit polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 112, 1015–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirsch J. G. (1956) Phagocytin: a bactericidal substance from polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J. Exp. Med. 103, 589–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klebanoff S. J. (1970) Myeloperoxidase-mediated antimicrobial systems and their role in leukocyte function. In Biochemistry of the Phagocytic Process (Schultz J., ed.), North Holland, Amsterdam, 89–110 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klebanoff S. J. (1967) Iodination of bacteria: a bactericidal mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 126, 1063–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klebanoff S. J. (1968) Myeloperoxidase-halide-hydrogen peroxide antibacterial system. J. Bacteriol. 95, 2131–2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeCoursey T. E. (2008) Voltage-gated proton channels: what's next? J. Physiol. 586, 5305–5324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El Chemaly A., Okochi Y., Sasaki M., Arnaudeau S., Okamura Y., Demaurex N. (2010) VSOP/Hv1 proton channels sustain calcium entry, neutrophil migration, and superoxide production by limiting cell depolarization and acidification. J. Exp. Med. 207, 129–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Demaurex N., El Chemaly A. (2010) Physiological roles of voltage-gated proton channels in leukocytes. J. Physiol. 588, 4659–4665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cech P., Lehrer R. I. (1984) Phagolysosomal pH of human neutrophils. Blood 63, 88–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. (1997) Myeloperoxidase: a key regulator of neutrophil oxidant production. Redox Report 3, 3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kettle A. J., Maroz A., Woodroffe G., Winterbourn C. C., Anderson R. F. (2011) Spectral and kinetic evidence for reaction of superoxide with compound I of myeloperoxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 2190–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harrison J. E., Schultz J. (1976) Studies on the chlorinating activity of myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1371–1374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Dalen C. J., Whitehouse M. W., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (1997) Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem. J. 327, 487–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Furtmuller P. G., Burner U., Obinger C. (1998) Reaction of myeloperoxidase compound I with chloride, bromide, iodide, and thiocyanate. Biochemistry 37, 17923–17930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hurst J. K. (2012) What really happens in the neutrophil phagosome? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 508–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Painter R. G., Wang G. (2006) Direct measurement of free chloride concentrations in the phagolysosomes of human neutrophils. Anal. Chem. 78, 3133–3137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winterbourn C. C., Hampton M. B., Livesey J. H., Kettle A. J. (2006) Modeling the reactions of superoxide and myeloperoxidase in the neutrophil phagosome: implications for microbial killing. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39860–39869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nicholls S. J., Hazen S. L. (2005) Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1102–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nussbaum C., Klinke A., Adam M., Baldus S., Sperandio M. (2012) Myeloperoxidase—a leukocyte-derived protagonist of inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal., Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng G., Salerno J. C., Cao Z., Pagano P. J., Lambeth J. D. (2008) Identification and characterization of VPO1, a new animal heme-containing peroxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1682–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng G., Li H., Cao Z., Qiu X., McCormick S., Thannickal V. J., Nauseef W. M. (2011) Vascular peroxidase-1 is rapidly secreted, circulates in plasma, and supports dityrosine cross-linking reactions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 1445–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhave G., Cummings C. F., Vanacore R. M., Kumagai-Cresse C., Ero-Tolliver I. A., Rafi M., Kang J. S., Pedchenko V., Fessler L. I., Fessler J. H., Hudson B. G. (2012) Peroxidasin forms sulfilimine chemical bonds using hypohalous acids in tissue genesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 784–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ashby M. T. (2008) Inorganic chemistry of defensive peroxidases in the human oral cavity. J. Dent. Res. 87, 900–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang J., Slungaard A. (2006) Role of eosinophil peroxidase in host defense and disease pathology. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 445, 256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomas E. L., Fishman M. (1986) Oxidation of chloride and thiocyanate by isolated leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9694–9702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chapman A. L., Skaff O., Senthilmohan R., Kettle A. J., Davies M. J. (2009) Hypobromous acid and bromamine production by neutrophils and modulation by superoxide. Biochem. J. 417, 773–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gaut J. P., Yeh G. C., Tran H. D., Byun J., Henderson J. P., Richter G. M., Brennan M. L., Lusis A. J., Belaaouaj A., Hotchkiss R. S., Heinecke J. W. (2001) Neutrophils employ the myeloperoxidase system to generate antimicrobial brominating and chlorinating oxidants during sepsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11961–11966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davies M. J., Hawkins C. L., Pattison D. I., Rees M. D. (2008) Mammalian heme peroxidases: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1199–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klebanoff S. J. (1993) Reactive nitrogen intermediates and antimicrobial activity: role of nitrite. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14, 351–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gaut J. P., Byun J., Tran H. D., Lauber W. M., Carroll J. A., Hotchkiss R. S., Belaaouaj A., Heinecke J. W. (2002) Myeloperoxidase produces nitrating oxidants in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 1311–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eiserich J. P., Cross C. E., Jones A. D., Halliwell B., van der Vliet A. (1996) Formation of nitrating and chlorinating species by reaction of nitrite with hypochlorous acid. A novel mechanism for nitric oxide-mediated protein modification. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19199–19208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van der Vliet A., Eiserich J. P., Halliwell B., Cross C. E. (1997) Formation of reactive nitrogen species during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7617–7625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eiserich J. P., Hristova M., Cross C. E., Jones A. D., Freeman B. A., Halliwell B., van der Vliet A. (1998) Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature 391, 393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jiang Q., Hurst J. K. (1997) Relative chlorinating, nitrating, and oxidizing capabilities of neutrophils determined with phagocytosable probes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32767–32772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rosen H., Crowley J. R., Heinecke J. W. (2002) Human neutrophils use the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-chloride system to chlorinate but not nitrate bacterial proteins during phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30463–30468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kettle A. J., Anderson R. F., Hampton M. B., Winterbourn C. C. (2007) Reactions of superoxide with myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry 46, 4888–4897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nauseef W. M. (2007) How human neutrophils kill and degrade microbes: an integrated view. Immunol. Rev. 219, 88–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gabig T. G., Bearman S. I., Babior B. M. (1979) Effects of oxygen tension and pH on the respiratory burst of human neutrophils. Blood 53, 1133–1139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Segal B. H., Leto T. L., Gallin J. I., Malech H. L., Holland S. M. (2000) Genetic, biochemical, and clinical features of chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 79, 170–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Assari T. (2006) Chronic granulomatous disease; fundamental stages in our understanding of CGD. Med. Immunol. 5, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mandell G. L. (1975) Catalase, superoxide dismutase, and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo studies with emphasis on staphylococcal-leukocyte interaction. J. Clin. Invest. 55, 561–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Root R. K. (1974) Correction of the function of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) granulocytes (PMN) with extracellular H2O2. Clin. Res. 22, 452A [Google Scholar]

- 54. Johnston R. B., Jr., Baehner R. L. (1970) Improvement of leukocyte bactericidal activity in chronic granulomatous disease. Blood 35, 350–355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ismail G., Boxer L. A., Baehner R. L. (1979) Utilization of liposomes for correction of the metabolic and bactericidal deficiencies in chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr. Res. 13, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gerber C. E., Bruchelt G., Falk U. B., Kimpfler A., Hauschild O., Kuci S., Bachi T., Niethammer D., Schubert R. (2001) Reconstitution of bactericidal activity in chronic granulomatous disease cells by glucose-oxidase-containing liposomes. Blood 98, 3097–3105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kaplan E. L., Laxdal T., Quie P. G. (1968) Studies of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease of childhood: bactericidal capacity for streptococci. Pediatrics 41, 591–599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Klebanoff S. J., White L. R. (1969) Iodination defect in the leukocytes of a patient with chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. N. Engl. J. Med. 280, 460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mandell G. L., Hook E. W. (1969) Leukocyte bactericidal activity in chronic granulomatous disease: correlation of bacterial hydrogen peroxide production and susceptibility to intracellular killing. J. Bacteriol. 100, 531–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Foote C. S., Goyne T. E., Lehrer R. I. (1983) Assessment of chlorination by human neutrophils. Nature 301, 715–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thomas E. L., Grisham M. B., Jefferson M. M. (1983) Myeloperoxidase-dependent effect of amines on functions of isolated neutrophils. J. Clin. Invest. 72, 441–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chapman A. L., Hampton M. B., Senthilmohan R., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (2002) Chlorination of bacterial and neutrophil proteins during phagocytosis and killing of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9757–9762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reeves E. P., Nagl M., Godovac-Zimmermann J., Segal A. W. (2003) Reassessment of the microbicidal activity of reactive oxygen species and hypochlorous acid with reference to the phagocytic vacuole of the neutrophil granulocyte. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 643–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jiang Q., Griffin D. A., Barofsky D. F., Hurst J. K. (1997) Intraphagosomal chlorination dynamics and yields determined using unique fluorescent bacterial mimics. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 10, 1080–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Koide Y., Urano Y., Hanaoka K., Terai T., Nagano T. (2011) Development of an Si-rhodamine-based far-red to near-infrared fluorescence probe selective for hypochlorous acid and its applications for biological imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5680–5682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang Z., Zheng Y., Hang W., Yan X., Zhao Y. (2011) Sensitive and selective off-on rhodamine hydrazide fluorescent chemosensor for hypochlorous acid detection and bioimaging. Talanta 85, 779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen X., Lee K. A., Ha E. M., Lee K. M., Seo Y. Y., Choi H. K., Kim H. N., Kim M. J., Cho C. S., Lee S. Y., Lee W. J., Yoon J. (2011) A specific and sensitive method for detection of hypochlorous acid for the imaging of microbe-induced HOCl production. Chem. Commun. (Camb). 47, 4373–4375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yan Y., Wang S., Liu Z., Wang H., Huang D. (2010) CdSe-ZnS quantum dots for selective and sensitive detection and quantification of hypochlorite. Anal. Chem. 82, 9775–9781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tlili A., Dupre-Crochet S., Erard M., Nusse O. (2011) Kinetic analysis of phagosomal production of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 50, 438–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schwartz J., Leidal K. G., Femling J. K., Weiss J. P., Nauseef W. M. (2009) Neutrophil bleaching of GFP-expressing staphylococci: probing the intraphagosomal fate of individual bacteria. J. Immunol. 183, 2632–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Painter R. G., Valentine V. G., Lanson N. A., Jr., Leidal K., Zhang Q., Lombard G., Thompson C., Viswanathan A., Nauseef W. M., Wang G., Wang G. (2006) CFTR expression in human neutrophils and the phagolysosomal chlorination defect in cystic fibrosis. Biochemistry 45, 10260–10269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rosen H., Klebanoff S. J., Wang Y., Brot N., Heinecke J. W., Fu X. (2009) Methionine oxidation contributes to bacterial killing by the myeloperoxidase system of neutrophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18686–18691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hazen S. L., Hsu F. F., Mueller D. M., Crowley J. R., Heinecke J. W. (1996) Human neutrophils employ chlorine gas as an oxidant during phagocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1283–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Segal A. W., Garcia R. C., Harper A. M. (1983) Iodination by stimulated human neutrophils. Studies on its stoichiometry, subcellular localization and relevance to microbial killing. Biochem. J. 210, 215–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Green J. N. (2009) Oxidant production inside the phagosomes of neutrophils. Ph.D. thesis/dissertation, University of Otago [Google Scholar]

- 76. Voetman A. A., Weening R. S., Hamers M. W., Meerhof L. J., Bot A. A. A. M., Roos D. (1981) Phagocytosing human neutrophils inactivate their own granular enzymes. J. Clin. Invest. 67, 1541–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Miyasaki K. T., Zambon J. J., Jones C. A., Wilson M. E. (1987) Role of high-avidity binding of human neutrophil myeloperoxidase in the killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 55, 1029–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Allen R. C., Stephens J. T., Jr., (2011) Myeloperoxidase selectively binds and selectively kills microbes. Infect. Immun. 79, 474–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Allen R. C., Stephens J. T., Jr., (2011) Reduced-oxidized difference spectral analysis and chemiluminescence-based Scatchard analysis demonstrate selective binding of myeloperoxidase to microbes. Luminescence 26, 208–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pattison D. I., Davies M. J. (2006) Reactions of myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants with biological substrates: gaining chemical insight into human inflammatory diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 13, 3271–3290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (2000) Biomarkers of myeloperoxidase-derived hypochlorous acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 29, 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bergt C., Fu X., Huq N. P., Kao J., Heinecke J. W. (2004) Lysine residues direct the chlorination of tyrosines in YXXK motifs of apolipoprotein A-I when hypochlorous acid oxidizes high density lipoprotein 5. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7856–7866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Domigan N. M., Charlton T. S., Duncan M. W., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (1995) Chlorination of tyrosyl residues in peptides by myeloperoxidase and human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16542–16548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Thomas E. L. (1979) Myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-chloride antimicrobial system: effect of exogenous amines on antibacterial action against Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 25, 110–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Grisham M. B., Jefferson M. M., Melton D. F., Thomas E. L. (1984) Chlorination of endogenous amines by isolated neutrophils. Ammonia-dependent bactericidal, cytotoxic and cytolytic activities of the chloramines. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 10404–10413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zgliczynski J. M., Stelmaszynska T., Domanski J., Ostrowski W. (1971) Chloramines as intermediates of oxidative reaction of amino acids by myeloperoxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 235, 419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Thomas E. L., Learn D. B. (1991) Myeloperoxidase: catalyzed oxidation of chloride and other halides: the role of chloramines. In Peroxidases in Chemistry and Biology, Vol. I (Everse J., Everse K. E., Grisham M. B., eds.), CRC, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 83–103 [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hazen S. L., d'Avignon A., Anderson M. M., Hsu F. F., Heinecke J. W. (1998) Human neutrophils employ the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-chloride system to oxidize α-amino acids to a family of reactive aldehydes. Mechanistic studies identifying labile intermediates along the reaction pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4997–5005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hazen S. L., Hsu F. F., d'Avignon A., Heinecke J. W. (1998) Human neutrophils employ myeloperoxidase to convert α-amino acids to a battery of reactive aldehydes: a pathway for aldehyde generation at sites of inflammation. Biochemistry 37, 6864–6873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weiss S. J., Lampert M. B., Test S. T. (1983) Long-lived oxidants generated by human neutrophils: characterization and bioactivity. Science 222, 625–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Coker M. S., Hu W. P., Senthilmohan S. T., Kettle A. J. (2008) Pathways for the decay of organic dichloramines and liberation of antimicrobial chloramine gases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 2334–2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Fu X., Parks W. C., Heinecke J. W. (2008) Activation and silencing of matrix metalloproteinases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 2–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wang Y., Rosen H., Madtes D. K., Shao B., Martin T. R., Heinecke J. W., Fu X. (2007) Myeloperoxidase inactivates TIMP-1 by oxidizing its N-terminal cysteine residue: an oxidative mechanism for regulating proteolysis during inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31826–31834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Clark R. A., Stone P. J., El Hag A., Calore J. D., Franzblau C. (1981) Myeloperoxidase-catalyzed inactivation of α1-protease inhibitor by human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 3348–3353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Takeuchi K., Umeki Y., Matsumoto N., Yamamoto K., Yoshida M., Suzuki K., Aratani Y. (2012) Severe neutrophil-mediated lung inflammation in myeloperoxidase-deficient mice exposed to zymosan. Inflamm. Res. 61, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Shvedova A. A., Kapralov A. A., Feng W. H., Kisin E. R., Murray A. R., Mercer R. R., St Croix C. M., Lang M. A., Watkins S. C., Konduru N. V., Allen B. L., Conroy J., Kotchey G. P., Mohamed B. M., Meade A. D., Volkov Y., Star A., Fadeel B., Kagan V. E. (2012) Impaired clearance and enhanced pulmonary inflammatory/fibrotic response to carbon nanotubes in myeloperoxidase-deficient mice. PLoS One 7, e30923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Metzler K. D., Fuchs T. A., Nauseef W. M., Reumaux D., Roesler J., Schulze I., Wahn V., Papayannopoulos V., Zychlinsky A. (2011) Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood 117, 953–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Papayannopoulos V., Metzler K. D., Hakkim A., Zychlinsky A. (2010) Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell Biol. 191, 677–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Parker H., Albrett A. M., Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. (2012) Myeloperoxidase associated with neutrophil extracellular traps is active and mediates bacterial killing in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. J. Leukoc. Biol. 91, 369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Holmes B., Quie P. G., Windhorst D. B., Good R. A. (1966) Fatal granulomatous disease of childhood. An inborn abnormality of phagocytic function. Lancet 1, 1225–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Baehner R. L., Nathan D. G. (1967) Leukocyte oxidase: defective activity in chronic granulomatous disease. Science 155, 835–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Johnston R. B., Jr., Keele B. B., Jr., Misra H. P., Lehmeyer J. E., Webb L. S., Baehner R. L., Rajagopalan K. V. (1975) The role of superoxide anion generation in phagocytic bactericidal activity. Studies with normal and chronic granulomatous disease leukocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 55, 1357–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Quie P. G. (1993) Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood: a saga of discovery and understanding. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 12, 395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Quie P. G., White J. G., Holmes B., Good R. A. (1967) In vitro bactericidal capacity of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: diminished activity in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. J. Clin. Invest. 46, 668–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Lehrer R. I., Cline M. J. (1969) Leukocyte myeloperoxidase deficiency and disseminated candidiasis: the role of myeloperoxidase in resistance to Candida infection. J. Clin. Invest. 48, 1478–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Cech P., Papathanassiou A., Boreux G., Roth P., Miescher P. A. (1979) Hereditary myeloperoxidase deficiency. Blood 53, 403–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Grignaschi V. J., Sperperato A. M., Etcheverry M. J., Macario A. J. L. (1963) Un nuevo cuadro citoquimico: negatividad espontanea de las reacciones de peroxidasas, oxidasas y lipido en la progenie neutrofila y en los monocitos de dos hermanos. Rev. Asoc. Med. Argent. 77, 218–221 [Google Scholar]

- 108. Huhn D., Belohradsky B. H., Haas R. (1978) Familiarer myeloperoxidasedefekt und akute myeloische Leukamie. Acta Haematol. 59, 129–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kitahara M., Simonian Y., Eyre H. J. (1979) Neutrophil myeloperoxidase: a simple reproducible technique to determine activity. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 93, 232–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Moosmann K., Bojanovsky A. (1975) Rezidivierende candidosis bei myeloperoxydasemangel. Mschr. Kinderheilk. 123, 408–409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Rosen H., Klebanoff S. J. (1976) Chemiluminescence and superoxide production by myeloperoxidase-deficient leukocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 58, 50–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Undritz E. (1966) Die aluis-grignaschi-anomalie: der erblich-konstitutionelle peroxydasedefekt der neutrophilen und monozyten. Blut 14, 129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Kitahara M., Eyre H. J., Simonian Y., Atkin C. L., Hasstedt S. J. (1981) Hereditary myeloperoxidase deficiency. Blood 57, 888–893 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Kutter D. (1998) Prevalence of myeloperoxidase deficiency: population studies using Bayer-Technicon automated hematology. J. Mol. Med. 76, 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kutter D., Al-Haidari K., Thoma J. (1994) Prevalence of myeloperoxidase deficiency: simple methods for its diagnosis and significance of different forms. Klin. Lab. 40, 342–346 [Google Scholar]

- 116. Marchetti C., Patriarca P., Solero G. P., Baralle F. E., Romano M. (2004) Genetic studies on myeloperoxidase deficiency in Italy. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57, S10–S12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Parry M. F., Root R. K., Metcalf J. A., Delaney K. K., Kaplow L. S., Richar W. J. (1981) Myeloperoxidase deficiency. Prevalence and clinical significance. Ann. Intern. Med. 95, 293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Rudolph T. K., Wipper S., Reiter B., Rudolph V., Coym A., Detter C., Lau D., Klinke A., Friedrichs K., Rau T., Pekarova M., Russ D., Knöll K., Kolk M., Schroeder B., Wegscheider K., Andresen H., Schwedhelm E., Boeger R., Ehmke H., Baldus S. (2011) Myeloperoxidase deficiency preserves vasomotor function in humans. Eur. Heart. J. 33, 1625–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Nunoi H., Kohi F., Kajiwara H., Suzuki K. (2003) Prevalence of inherited myeloperoxidase deficiency in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 47, 527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Kusenbach G., Rister M. (1985) Der myeloperoxidase—mangel als ursache rezidivierender infektionen. Klin. Padiatr. 197, 443–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Robertson C. F., Thong Y. H., Hodge G. L., Cheney K. (1979) Primary myeloperoxidase deficiency associated with impaired neutrophil margination and chemotaxis. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 68, 915–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Stendahl O., Lindgren S. (1976) Function of granulocytes with deficient myeloperoxidase-mediated iodination in a patient with generalized pustular psoriasis. Scand. J. Haematol. 16, 144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kalinski T., Jentsch-Ullrich K., Fill S., Konig B., Costa S. D., Roessner A. (2007) Lethal candida sepsis associated with myeloperoxidase deficiency and pre-eclampsia. APMIS 115, 875–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]