Abstract

Objectives

Chromatin-associated repression is one mechanism that maintains HIV-1 latency. Inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDAC) reverses this repression resulting in viral expression from quiescently infected cells. Clinical studies with the HDAC inhibitor valproic acid (VPA) failed to substantially decrease the latent pool within resting CD4+ cells. Here we compared the efficacy of ITF2357, an orally active and safe HDAC inhibitor, with VPA for HIV-1 expression from latently infected cells in vitro. We also evaluated the effect of ITF2357 on the surface expression of CXCR4 and CCR5.

Methods

Latently infected cell lines were incubated with either ITF2357 or VPA and p24 levels were measured. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of un-infected donors were treated with ITF2357 and HIV-1 co-receptors expression was assessed by flow cytometry.

Results

At clinically relevant concentrations, ITF2357 increased p24 by 15-fold in ACH2 cells and by 9-fold in U1 cells whereas VPA increased expression less than 2-fold. Analogues of ITF2357 primarily targeting HDAC-1 increased p24 up to 30-fold. In CD4+ T-cells treated with ITF2357, CXCR4 expression decreased by 54% (P<0.001).

Conclusion

ITF2357 is superior to VPA in inducing HIV-1 from latently infected cells. Safely used in humans, ITF2357 is an attractive candidate for HIV-1 clinical purging.

Keywords: HIV-1, latency, histone deacetylase inhibitors, CCR5, CXCR4

Introduction

Since the introduction of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) more than a decade ago, HIV-1 infection can be well controlled, with HIV-1 viremia below detectable levels. However, eradication of HIV-1 infection with prolonged HAART therapy is still not feasible. Following discontinuation of HAART, rebound viremia occurs, typically after two weeks 1-4. The source of viral re-emergence is from a long-lived pool, most likely the latently infected memory T-cell reservoir, harboring integrated HIV-1 proviral DNA 2. Well established techniques are available to quantify the latent pool and it is estimated that one in every million memory cells of an HIV-1 positive patient bears a replication competent integrated provirus5, 6.

The latent reservoir of HIV-1 within resting CD4+ cells is established early after acute infection and the initiation of HAART during this period does not prevent its establishment 6-8. The latent pool is an extremely stable reservoir, having a half-life of 6-44 months even in treated patients who are continuously aviremic for long periods of time6, 9-12. Having this prolonged half-life, a complete decay of the reservoir is not expected before 70 years of treatment making eradication improbable. These time frames might be somewhat shorter by starting HAART early during acute infection or by intensifying HAART but not sufficient as a practical method for eradication 13, 14.

Mechanisms that maintain the proviral DNA transcriptionally inactive in the quiescent cells (see review in 15, 16) include chromatin-associated regulation. In the latent cell, the integrated proviral DNA is densely organized in nucleosomes. The HIV-1 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR), containing the promoter and enhancer elements, binds several transcription factors and is arranged in two nucleosomes (nuc-0 and nuc-1)17. The NFκB p50 homodimer, as well as AP-4, YY1 and LSF1 recruit histone deacetylase (HDAC)-1 to the LTR, which in turn results in deacetylation of local histones, compaction of the chromatin and prevention of RNA polymerase-II binding18-21. In vitro studies have demonstrated that activation of the latent cell pool by different stimuli would reverse the repressive effect of the p50 homodimer-HDAC-1 complex by the binding of cytosolic NFκB p50-RelA heterodimer 19, 22. This would enable the recruitment of histones acetyltransferase (HAT), acetylaton of the local histones, relaxation of the chromatin and initiation of transcription 19, 23, 24.

Inhibition of the enzymatic activity of HDAC-1 and likely HDAC-2 and 3 by synthetic inhibitors of HDACs (HDACi) leads to activation of the HIV-1 LTR and HIV-1 gene expression. Moreover, unlike cell activators of NFκB, such as IL-2, OKT3 or TNFα, HDACi facilitate gene expression without general activation cytokines and the T-cell25, 26.

In vitro, various HDACi induce HIV-1 gene expression from latently infected cells line27-29. Valproic acid (VPA), a carboxilate HDACi prescribed for seizures and psychiatric disorders, has been combined with HAART in small clinical trials but without the desirable significant decrease of the latent reservoir 26, 30-32. The studies with VPA, a non-specific weak HDACi, have not resolved the potential of HDACi to purge the virus.

ITF2357 is a hydroxamic acid-containing HDACi that has anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties in vitro and in vivo33-36. At therapeutic plasma levels of 125-250nM, there is no cell-toxicity in vitro and only minor reversible thrombocytopenia occurs in patients37. As an anti-inflammatory agent, twelve weeks of daily ITF2357 has been given to children with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA) with no safety issues and promising clinical improvement 38. Since ITF2357 was shown to be a potent anti-inflammatory drug that is effective in nano-molar concentrations for cytokines suppression, we hypothesized it would be a potent stimulator of HIV-1 gene expression in latently infected cell lines. We also examined the effects of three analogues of ITF2357, with a higher affinity and specificity for HDAC-1. Because of the importance of the chemokine co-receptors for HIV-1 cell entry, we evaluated surface expression of CCR5 and CXCR4 on primary human mononuclear blood cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and cell lines

ITF2357 and analogues were synthesized by the chemical department of Italfarmaco (Cinisello Balsamo, Italy). VPA and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). RPMI 1640, FCS and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Cellgro (Manassas, VA). ITF2357 and analogues were first dissolved in DMSO and then further diluted in RPMI (final concentration of DMSO was 0.01%).

The U1 and ACH2 cell lines were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Cells were cultured in flasks, washed in RPMI and resuspended in RPMI/10% FCS to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL. 250μL of cells, 200μL of media and 50μL of HDACi/media containing 0.01% DMSO were aliquoted into 48-well polystyrene tissue culture plate (Falcon, Lincoln Park, NJ). After 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C/5%CO2, 50μL of supernatant were removed for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay and Triton-X-100 (0.5% vol/vol final concentration) was added to each culture. p24 assays of lysates were done immediately.

Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays

p24 was measured using specific antibodies immobilized on magnetic beads as described previously 39.

Cytotoxicity assay

Acute cytotoxicity was determined using LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit II according to manufacturer's instructions (Vision, Mountain View, CA). In some experiments, cytotoxicity was verified using Cell-titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit according to manufacturer's protocol. (Promega, Madison, WI).

HDAC inhibition assay

Human recombinant enzymes were purchased from BPS Biosciences (Torrance, CA). Class I isoforms HDAC1, 2, 3; Class IIb HDAC6, 10 and Class IV HDAC11 were tested using the synthetic fluorogenic substrate Fluor-de-lys (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Class IIa isforms were tested using the derivative of Boc-L-Lys-MCA (TFAL), described as specific substrate for these enzymes40. Assay of human recombinant HDAC8 was performed using HDAC8 Fluorimetric Drug Discovery Kit (Enzo) according to manufacturer's instructions. Each inhibitor was dissolved in DMSO and then further diluted in assay buffer. Concentrations of DMSO less than 0.5% did not affect the activity of the assay. The assays were performed by pre-incubating each enzyme with the inhibitors for 15 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was initiated by adding the substrate at 37°C and allowed to proceed for 60 minutes. The fluorescent signal was generated by adding 50μL of a 2-fold concentrated developing solution (Enzo) containing 4μM trichostatin A. The fluorescence generated was detected at wavelengths 355nm (excitation) and 460nm (emission).

Preparation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

These studies were approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Blood was taken from healthy HIV-1 negative human subjects according to previously described methods.41

Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface molecules

PBMC were incubated with ITF2357, VPA or vehicle media (containing the same concentrations of 0.01% DMSO). After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS/1%BSA, incubated for 15 minutes with FcR-Binding Inhibitor (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with monoclonal antibodies as follows: anti-CD4 (Per-CP; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-CD3 (FITC; R&D Systems), anti-CXCR4 (APC; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ), anti-CCR5 (PE; BD), anti-CD14 (eFluor 450; eBioscience). Appropriate fluorescence minus one (FMO) (T-cells) or isotype antibodies (monocytes) were used in each experiment. Cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using LSR-II (BD). Lymphocyte gating was based on forward and side scatter and was further analyzed to identify CD3+ CD4+ cells on which CCR5 and CXCR4 expression were determined. Monocytes were identified by CD14+ expression. All experiments were done in duplicate and at least 200,000 events were collected. Whole blood was diluted 1:4 in RPMI and incubated with HDACi or media alone. After incubation blood was washed twice with PBS/1%BSA/0.02% sodium azide. 100μl of each sample was stained and fixed as described above. Data analysis was done using FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

RNA isolation and real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated using mirVana kits (Ambion, Austin, TX), followed by determination of RNA concentrations using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Reverse transcription and TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCRs) were then performed using the following primers and probes: CXCR4, β-Actin and GAPDH. All RT-PCR reagents and devices were by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Relative quantities were calculated by the ΔΔCT method as described previously 42.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the percent of cytotoxicity and co-receptors expression were analyzed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney unpaired test. All reported P values were two tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Comparison of VPA and ITF2357 in latently infected HIV-1 cell lines

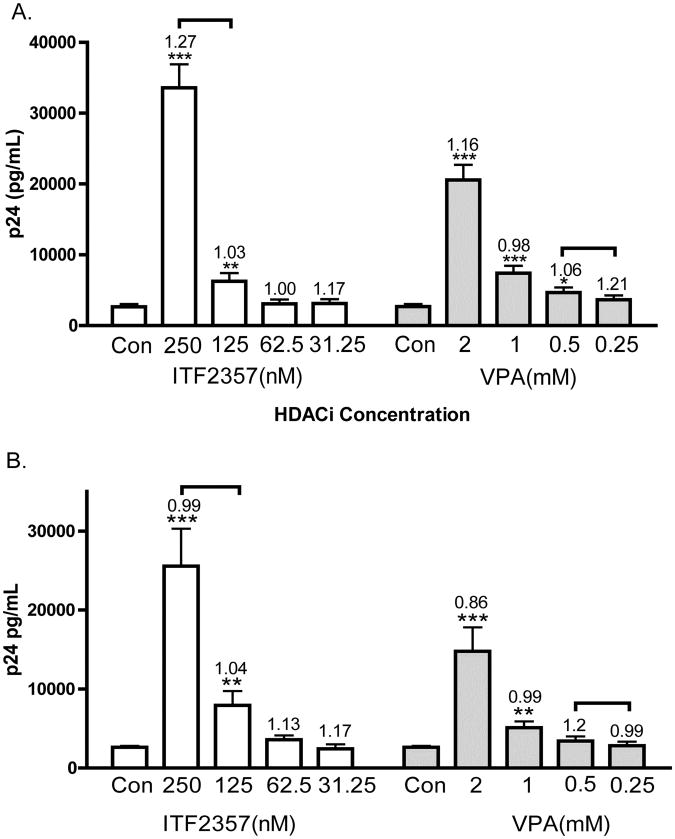

We compared the ability of VPA and ITF2357 to induce the expression of HIV-1 in a dose response study that included the plasma concentrations of each HDACi achieved in humans. As shown in Figure 1A, after 24 hours of incubation, ACH2 cells responded to VPA with a doubling of p24 at 1mM and an 8.7-fold increase at 2mM; however, these plasma concentrations of VPA are often toxic in humans. Upon 24 hours of incubation of ACH2 cells with ITF2357, a two-fold increase was observed at 125nM whereas there was a 15-fold increase at 250nM. Unlike VPA, these levels of HIV-1 expression at 250nM ITF2357 are at concentrations sustained in humans without side effects. As shown in brackets of Figure 1A, a mean therapeutic concentration of ITF2357 is 200nM and 0.25-0.6mM (40-100 μg/mL) for VPA.

Figure 1. HIV-1 expression in ACH2 and U1 cells stimulated by ITF2357 or VPA.

(A) Mean ±SEM p24 pg/mL in ACH2 cells of 20 separate experiments. (B) Mean ±SEM p24 pg/mL in U1 cells of 22 separate experiments. Numbers above error bars indicate the mean fold change of cell death as determined by LDH cytotoxicity assay. The levels of LDH for each experiment without HDAC inhibitors were set at 1.0 and fold increases calculated. The brackets above the error bars indicate the range of therapeutic plasma levels for each HDAC inhibitors.

We then measured the effect of ITF2357 and VPA in U1 cells. As shown in Figure 1B, mean levels of p24 were 0.9, 1.3, 2.7 and 9.1-fold higher than control cultures at ITF2357 concentrations of 31, 62, 125, 250nM, respectively. VPA at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2mM dose-dependently increased p24 production by 0.9, 1.2, 1.8 and 5.5 fold. Similar to the data in ACH2 cells, VPA at clinical relevant concentrations (indicated in brackets) did not double the levels of p24. In contrast, ITF2357 increased HIV-1 production by nearly 3-fold at 125nM and 9-fold increase was observed at 250nM.

In order to ascertain that the stimulation of HIV-1 expression by either ITF2357 or VPA was due to stimulation of HIV-1 expression by HDAC inhibitors and not due to cell stress, LDH cytotoxicity assays were performed. The numbers above each error bar in Figures 1A indicate the mean fold change in cell death compared to control cultures set as 1.0. In ACH2 cells, ITF2357 concentrations of 31, 62, 125 and 250nM increased LDH levels by 1.1, 1.0, 1.0 and 1.2 fold, respectively. At VPA concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2mM, the mean percent cytotoxicity was different by 1.2, 1.1, 0.9 and 1.2 fold, respectively. None of these values was significantly higher than the mean cell death of the control cultures. Similarly, levels of cell death in U1 cells were not significantly different from untreated cultures.

Comparison of time-dependent stimulation of HIV-1 by VPA and ITF2357 in ACH2 cells

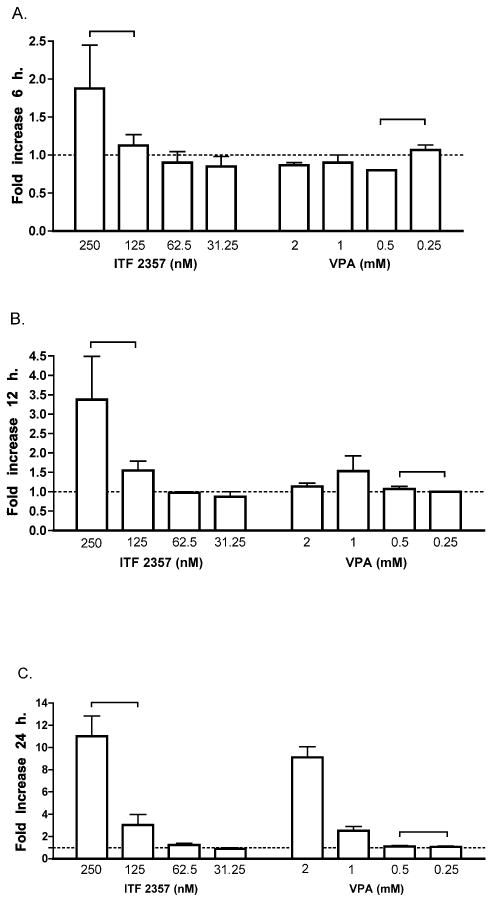

In clinical trials, the total daily dose of ITF2357 is 1.5mg/kg administered in two divided oral doses; the daily dose of VPA is 15mg/kg in three divided oral doses. Therefore, we investigated the effect of ITF2357 and VPA at different time points. Cultures were incubated for either 6, 12 or 24 hours with either ITF2357 or VPA. As shown in Figure 2, after 6 hours of exposure to VPA, there was no induction of p24 at any concentration. On the other hand, ITF2357 at 250nM increased p24 levels 1.9-fold over control levels (set at 1 for 6 hours). After 12 hours of incubation, there was no increase with any concentration of VPA compared to a 3.4-fold increase at 250nM of ITF2357. Lower concentrations of ITF2357 did not show increase in p24 after 12 hours of incubation. By 24 hours, there were increases comparable to those shown in Figure 1A for ITF2357 and VPA.

Figure 2. Time-dependent HIV-1 production in ACH2 cells exposed to VPA or ITF2357.

Mean ±SEM fold-increase in levels of p24. The level of p24 for each experiment without HDAC inhibitors was set at 1.0 and fold increase values calculated. All experiments were performed in triplicate in three independent experiments. Dashed line represents control cultures set at 1.0. The brackets indicate the range of therapeutic plasma levels for each HDAC inhibitor. (A) p24 fold increase after incubation of 6 hours with either ITF2357 or VPA. (B) p24 fold increase after incubation of 12 hours. (C) p24 after 24 hours of incubation.

Effect of ITF2357 analogues on HIV-1 expression

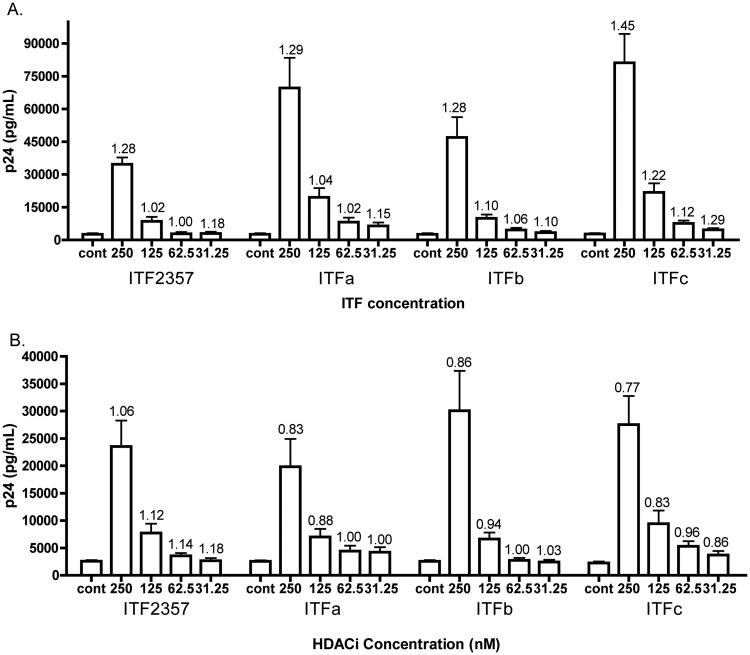

Since ITF2357 was more effective at inducing HIV-1 expression than VPA at clinically relevant concentrations, we evaluated three hydroxamic acid-containing analogues. Table 1 compares the mean concentration of ITF2357, three analogues of ITF2357 as well as VPA and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), to inhibit 50% of the enzymatic activity of different HDACs. We next compared the effect of increasing concentrations of each analogue on p24 production from ACH2 cells. As shown in Figure 3A, each of the three analogues induced higher levels of HIV-1 compared to the same concentrations of ITF2357. For example at 125nM, there was a mean increase of 2-fold by ITF2357 whereas two analogues (ITFa and ITFc) resulted in nearly 10-fold increases. At 250nM, these two analogues induced 27 and 35-fold increases, respectively, compared to a 15-fold increase by ITF2357. The higher level of HIV-1 expression was observed with analogues that exhibited the greatest potency in inhibiting the Class-I HDAC inhibitors: HDAC-1, HDAC-2 and HDAC-3. As shown in Figure 3A, cell death as determined by LDH activity after 24 hours was not significantly different in cells exposed to the analogues compared to untreated cells.

Table 1. IC50 (in nM) of different human HDAC inhibitors1.

| Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | ClassIIa | ClassIIa | ClassIIa | ClassIIa | ClassIIb | ClassIIb | Class IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | HDAC-1 | HDAC-2 | HDAC-3 | HDAC-8 | HDAC-4 | HDAC-5 | HDAC-7 | HDAC-9 | HDAC-6 | HDAC-10 | HDAC-11 |

| ITF2357 | 133 | 293 | 136 | 837 | 1059 | 532 | 524 | 512 | 312 | 331 | 287 |

| ITFa | 81 | 72 | 117 | 144 | >10000 | nd | 7372 | >10000 | 469 | 260 | 314 |

| ITFb | 62 | 29 | 269 | 438 | 4541 | nd | 1728 | 4109 | 2751 | 125 | 412 |

| IFTc | 16 | 59 | 32 | 8583 | 1885 | nd | 1635 | 1033 | 1725 | 436 | 125 |

| VPA | 3940 | >5000 | >5000 | 1590 | >5000 | >5000 | >5000 | >5000 | >5000 | nd | nd |

| SAHA | 89 | 707 | 182 | 1494 | >10000 | nd | >10000 | >10000 | 358 | 143 | 175 |

Mean values of at least three separate determinations.

nd denodes not done.

Figure 3. HIV-1 expression in ACH2 and U1 cells by ITF2357 and three analogues.

p24 (A) Mean ±SEM p24 in pg/ml/mL in ACH2 cells of 17 separate experiments. (B) Mean ±SEM p24 in pg/ml/mL in U1 cells of 16 separate experiments. Numbers above error bars indicate the mean fold change of cell death as determined by LDH cytotoxicity assay. The levels of LDH for each experiment without HDAC inhibitors were set at 1.0 and mean fold increases calculated.

In U1 cells, the three analogues induced similar increases in p24 to that of ITF2357. For example, as shown in Figure 3B, levels of p24 were 8.4-fold for ITFa at 250nM compared to 10.1-fold for ITF2357. At the same concentration, ITFb and ITFc yielded increases of 9.2 and 11.6 fold. As in ACH2 cells, cytotoxicity was measured in each experiment and is shown above error bars (Figure 3B). In fact, each analogue resulted in less cytototoxicity compared to ITF2357 but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

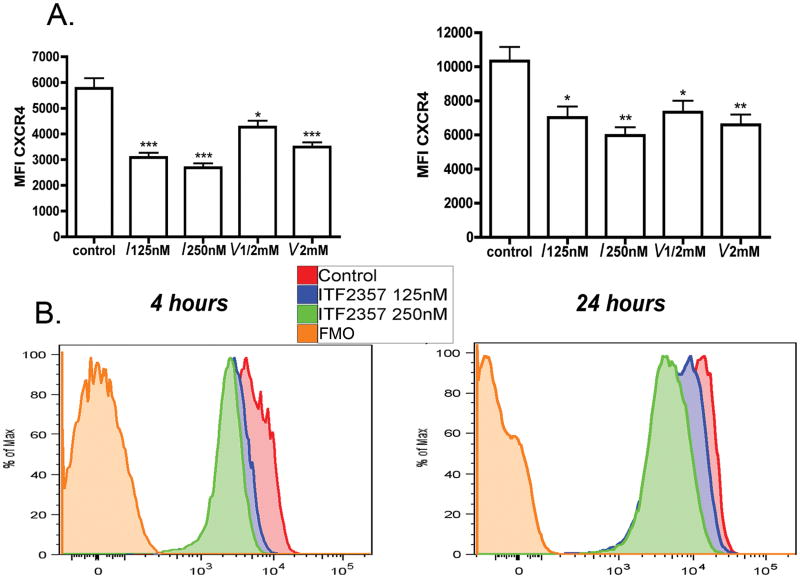

Expression of CXCR4 on CD4+ T-cells

PBMC from 7 healthy donors were incubated in the presence of ITF2357, VPA or media. After 4 and 24 hours, the surface expression of HIV-1 co-receptors was evaluated. We observed no changes in CCR5 surface expression on CD3+ CD4+ cells, as measured by both MFI as well as percent of positive cells. Moreover, as shown in Figure 4A and 4B, at therapeutically relevant concentrations of ITF2357 of 125nM and 250nM and of VPA at 0.5mM there was a dose-dependent decrease in the MFI of CXCR4. At 4 hours, a decrease of 47% (P<0.001) and 54% (P<0.001) was observed for 125nM and 250nM, respectively. At 24 hours, MFI ± SEM levels decreased by 32% (P=0.011) and 42% (P=0.002) for 125nM and 250nM of ITF2357, respectively. In unfractionated whole blood, we observed a similar trend in co-receptors expression in response to ITF2357 (data not shown). Consistent with the reduction of surface CXCR4 expression, steady-state mRNA levels of CXCR4 after 2 and 4 hours, as measured by RT-PCR, were reduced by 65% in cultures treated with 250nM of ITF2357 compared to control cultures (data not shown).

Figure 4. CXCR4 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes.

PBMC were treated with ITF2357 and VPA for either 4 or 24 hours. Percent of CXCR4 expressing cells was determined by four-color flow cytometry. The concentration for each HDACi are shown under each bar (I- ITF2357; V- VPA) . (A) Mean MFI ± SEM of CXCR4 on CD4+ T-cells after 4 hours (left) and 24 hours (right) incubation. The data are from seven different donors. (B) A representative experiment showing percent of maximal CXCR4 MFI of control cultures compared to 125nM and 250nM of ITF2357 at 4 (left) and 24 hours. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01. *** P<0.001 compared to control expression level.

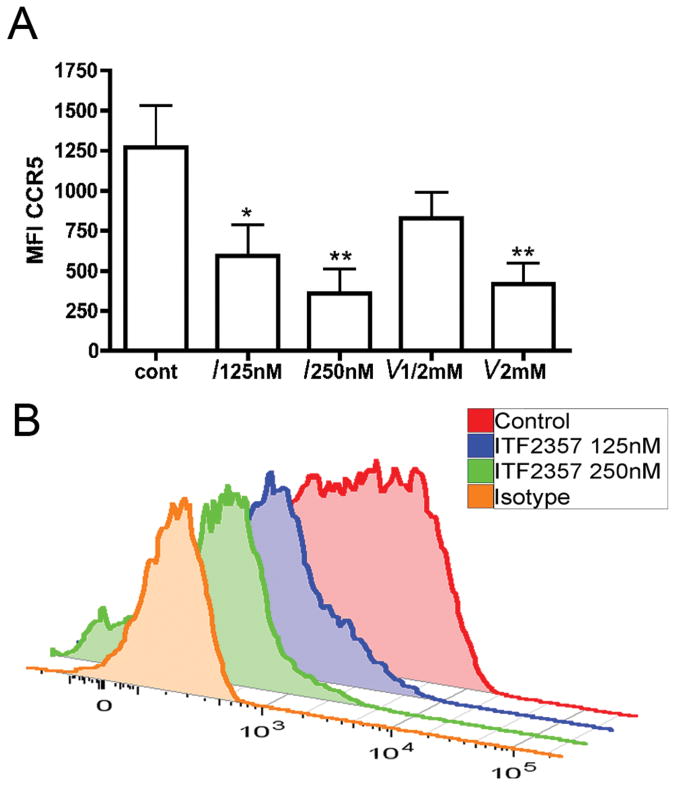

Expression of CCR5 on monocytes

As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, gating on CD14+ monocytes after 24 hours revealed a markedly decreased expression of CCR5 at both 125nM and 250nM of ITF2357 (MFI±SEM of 595 ±191, P=0.02 and 357 ±153 P=0.007, respectively). These changes were not observed with VPA at clinically relevant concentrations. We also studied the effect of ITF2357 on CCR5 gene expression in PBMC of three donors. PBMC were stimulated with LPS (100ng/mL) in the absence or presence of ITF2357 (100nM). After 4 hours, mRNA was obtained and gene expression was determined by Affimetrix chip analysis. Compared to LPS only, there was a 4.3-fold reduction in LPS-stimulated CCR5 gene expression (P<0.01).

Figure 5. Effect of HDACi on MFI of CCR5 in mononcytes.

PBMC were treated with ITF2357 and VPA for 24 hours and then subjected to flow cytometry for CCR5 expression. The concentration of each HDACi are shown under each bar (I- ITF2357; V- VPA). (A) MFI ±SEM in 7 donors. (B) A representative experiment showing MFI of CCR5 in isotype control, control culture, ITF2357 125nM and 250nM. * P<0.05. ** P<0.01

To demonstrate that the decrease in co-receptor surface expression was not due to cell death, levels of LDH were measured in the supernatants of PBMC. There was no increase in LDH released from cultures exposes to ITF2357 or VPA after 4 and 24 hours compared to control. Moreover, Annexin V and PI staining of PBMCs or isolated monocytes treated with up to 300 nM of ITF2357 was not different to that of control cultures36. In addition, surface expression of CD3 and CD4 did not change in response to HDAC exposure. We conclude that the decrease in co-receptor expression is specific for ITF2357 and not due to cell stress.

Discussion

The reservoir of latently infected memory CD4+ T-cells represents a major obstacle in eliminating HIV-1 infection. Although consistent with reversing viral latency, HDAC inhibitors have not been fully exploited to purge the virus from the quiescent pool. In the present report, we demonstrate that ITF2357 exhibits a greater induction of HIV-1 than VPA, the only HDAC inhibitor that has been evaluated in vivo for HIV-1 purging. ITF2357 increased p24 production in a macrophage as well as T-cell line. Based on the present study, we propose that ITF2357 would be superior to VPA in clinical trials. Clearly, the next step is to compare viral induction of resting CD4+ T-cells from aviremic HIV-1 positive donors when exposed to ITF2357 or VPA in vitro.

There are three major advantages of ITF2357. First, at clinically achievable blood levels, ITF2357 induces at least a 10-fold increase in HIV-1 from latently infected cell in vitro compared to less than 2-fold for VPA. Second, oral ITF2357 is well tolerated in humans, including children38. Third, ITF2357 did not increase CCR5 surface expression on CD4+ T-cells, despite the fact that HDAC inhibitors often increase gene expression. It would be counter-productive if agents stimulating latent virus up-regulated CCR5 and CXCR4 surface expression. In fact, surface expression of CXCR4 on CD4+ T-cells and CCR5 on monocytes was reduced by 50% by ITF2357. Although downregulation of CXCR4 by HDAC inhibitors has been observed in leukemic cells 43, this property of ITF2357 was unexpected in primary blood monocytes and T-cells from healthy donors. Consistent with decreasing co-receptors surface expression, ITF2357 reduced steady-state mRNA levels of CXCR4 and CCR5 in PBMC, as measured by RT-PCR and also by gene chip expression, respectively. To our knowledge, this is the first time that this inhibitory role of HDAC inhibitors on CD4+ T-cells and monocytes has been demonstrated

One possible explanation for the decreased co-receptor gene expression is that ITF2357 directly inhibits transcription. Another possibility is that ITF2357 up-regulates transcriptional repressors. Although several pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, and interleukin-1β negatively regulate CXCR4 transcription44, a cytokine-mediated mechanism is unlikely since ITF2357 decreases the synthesis of these cytokines induced by Toll-like receptor ligands in PBMCs36.

Clinically, the cell surface density of co-receptors has a major role in HIV-1 infection. CCR5 density on CD4+ T-cells is an important driver of R5 HIV-1 replication 45 and positively correlated with viral load 46and disease progression47. The density of CCR5 can also determine the susceptibility of macrophages and monocytes to infection by R5 strains48, 49. The emergence of X4 strain is associated with disease progression and a rapid decline in CD4+ T-cells 50 and a link between CXCR4 density and X4 emergence has been suggested. There is an ongoing issue whether residual viremia in HIV-1 patients under HAART represents new cycles of viral replication13 or virus output from stable reservoirs 51. These studies are based on viremia under steady state conditions. However, although treated, HIV-1 patients often have transient rebounds of viremia. Therefore, the reduction in co-receptor surface expression by ITF2357 is valuable if added to the HAART regimen.

Attractive as the concept of HIV-1 purging by HDAC inhibitors is, clinical trials using VPA did not reduce the size of the latent pool within resting CD4+ T cells. As the probability of side effects and particularly severe thrombocytopenia increases significantly at VPA plasma concentrations above 110μg/mL in females and 135μg/mL in males (see 52for review). To induce more viral expression with higher concentrations of VPA would be impractical. As shown in the present study, ITF2357 is significantly more effective than VPA in inducing HIV-1 production from U1 and ACH2 cells. Another hydroxamic acid containing HDACi, SAHA, is also more potent than VPA for HIV-1 induction in vitro27. The comparison of HDAC inhibition between ITF2357 and SAHA is shown in Table 1. In unpublished data from our laboratory, ITF2357 is 50-100 times more potent than SAHA in HIV-1 expression from U1 and ACH2 cells. Also, we describe here that two hydroxamic acid-containing analogues of ITF2357, ITFa and ITFc, at comparable nanomolar concentrations, induced p24 to higher levels compared to the parent compound.

HDACs are divided into 3 major classes. Class I is comprised of HDAC-1, 2, 3 and 8. Class II is comprised of HDAC 4, 5, 6, 7 and 10. HDAC-11 has properties of both class I and class II. The class III HDAC are not affected by HDAC inhibitors. Various pharmacological agents such as pyrrole-imidazole polyamides, trichostatin A, SAHA or phorbol esters effectively prevent the recruitment of HDAC-1 to the HIV-1 promoter allowing hyperacetylation of H3 and H423, 53, 54. In addition, a link between HDAC-2 and HDAC-3 and the HIV-1 LTR has been suggested55, 56. As shown in Table 1, we compared the ability of four hydroxamic acid-containing HDAC inhibitors to reduce the enzymatic activity of HDACs by 50%. In addition, the ability of VPA to inhibit the same HDACs was determined in the same assays. In each case, the IC50 of each the four hydroxamic acid-containing HDAC inhibitors and VPA were compared to induction of HIV-1 in U1 and ACH2 cells.

In general, there was greater induction of HIV-1 expression with analogues with the lowest IC50 for Class I HDACs 1, 2 and 3. These observations are consistent with the molecular association between the HIV-1 LTR and HDACs 1, 2 and 3. In contrast, VPA is impressively a weak inhibitor of each HDAC compared to ITF2357 and analogues (Table 1). In fact, the IC50 for VPA for HDAC inhibition is not achievable clinically and therefore not surprisingly, VPA failed to efficiently induce HIV-1 expression in vitro in the present study. Thus testing the hypothesis of HDAC inhibition for HIV-1 purging from latently infected cells should be re-visited using HDAC inhibitors such as ITF2357 or its analogues with specificity and potency for class I HDACs.

Consistent with the present observations, Archin et al demonstrated that HDAC inhibitors specifically targeting class I HDACs induced HIV-1 gene expression from cell lines and resting CD4+ T cells of aviremic patients57. An additive effect was seen with inhibition of HDAC-6. Our findings support those data regarding the selectivity of the class I HDACs 1, 2 and 3 inhibition and the potency of induction of HIV-1 gene expression. For example, in ACH2 cells, ITFc, a specific inhibitor of HDAC-1, 2 and 3 was twice as active in inducing p24 (35 fold) compared to ITF2357 (15-fold). However, inhibiton of HDAC-6 is inconsistent with the effectiveness of the three analogues, which were poor inhibitors of HDAC-6, particularly ITFc. Importantly, preserving the deacetylated status of HDAC-6 might protect CD4+ cells from HIV-1 infection and Env-mediated syncytia formation58.

In the study by Archin et al, out of four HDAC inhibitors that were active in inducing HIV-1 gene expression in cells lines, only two recovered replication competent virus from resting CD4+ T cells of infected patients. We propose that from the data of the present study, ITF2357 or its analogues would be effective inducers of virus outgrowth from resting CD4+ cells of aviremic HIV-1 infected patients. The analogues have minor antiproliferative properties, which Archin et al suggested may interfere with maintaining the cell line in vitro potency in resting CD4+ of infected patients. However, since cell lines do not reflect the status HIV-1 of resting CD4+ T cells, measuring recovery of replication competent virus from these cells would clearly be necessary.

Safety is always a consideration when evaluating a drug in a disease with no immediate danger to the patient. In testing the hypothesis that HDAC inhibition will purge the latent pool of HIV-1, VPA falls short due to a low level of expression compared to ITF2357. Oral ITF2357 is safe and effective in humans. In healthy human subjects in a Phase I trial, a single dose of ITF2357 of 1.5mg/Kg resulted in a peak plasma level of 200nM 37. In a Phase II trial in children with active SoJIA, a daily oral dose of ITF2357 at 1.5 mg/kg for 12 weeks exhibited no organ toxicity and achieved significant (p<0.01) reduction in parameters of systemic disease as well as the number of painful joints 38.

In conclusion, this present study demonstrates that at clinically relevant doses, ITF2357 induces HIV-1 production from latently infected cell lines, and at the same time reduces the MFI of HIV-1 entry co-receptors. For targeting clearance of HIV-1 infection, ITF2357 might be an effective addition to the HAART regimen of HIV-1 patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tania Azam for her assistance and Dr. Elizabeth Connick and Dr. Thomas Campbell for their helpful comments.

SM., CAD, PM, GF and MFN designed the study. SM, GF, AF, AK and MFN performed the experiments. SM, CAD, PM, and GF wrote the manuscript. BEP, SM and AK analyzed the flow cytometry.

Each author read and approved the text as submitted to JAIDS.

SM and AF performed the statistical analysis.

These studies were supported by NIH Grants AI 15614 and CA 046934. Funding was also provided by Italfarmarco, SpA, Cinisello Balsamo, Italy.

Supported by NIH Grant AI 15614 and CA 046934. Funding was also provided by Italfarmarco, S.p.A., Cinisello Balsamo, Italy.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. PM and GF are employees of Italfarmaco. CAD is a consultant to Italfarmaco.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Imamichi H, Crandall KA, Natarajan V, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasi species that rebound after discontinuation of highly active antiretroviral therapy are similar to the viral quasi species present before initiation of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2001 Jan 1;183(1):36–50. doi: 10.1086/317641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Chung C, Hu BS, et al. Genetic characterization of rebounding HIV-1 after cessation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Invest. 2000 Oct;106(7):839–845. doi: 10.1172/JCI10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey RT, Jr, Bhat N, Yoder C, et al. HIV-1 and T cell dynamics after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with a history of sustained viral suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Dec 21;96(26):15109–15114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun TW, Davey RT, Jr, Ostrowski M, et al. Relationship between pre-existing viral reservoirs and the re-emergence of plasma viremia after discontinuation of highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Nat Med. 2000 Jul;6(7):757–761. doi: 10.1038/77481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D, et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997 May 8;387(6629):183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997 Nov 14;278(5341):1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun TW, Engel D, Berrey MM, Shea T, Corey L, Fauci AS. Early establishment of a pool of latently infected, resting CD4(+) T cells during primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Jul 21;95(15):8869–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lori F, Jessen H, Lieberman J, et al. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection with hydroxyurea, didanosine, and a protease inhibitor before seroconversion is associated with normalized immune parameters and limited viral reservoir. J Infect Dis. 1999 Dec;180(6):1827–1832. doi: 10.1086/315113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D, et al. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med. 2003 Jun;9(6):727–728. doi: 10.1038/nm880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Ramratnam B, Tenner-Racz K, et al. Quantifying residual HIV-1 replication in patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 27;340(21):1605–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramratnam B, Mittler JE, Zhang L, et al. The decay of the latent reservoir of replication-competent HIV-1 is inversely correlated with the extent of residual viral replication during prolonged anti-retroviral therapy. Nat Med. 2000 Jan;6(1):82–85. doi: 10.1038/71577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun TW, Nickle DC, Justement JS, et al. HIV-infected individuals receiving effective antiviral therapy for extended periods of time continually replenish their viral reservoir. J Clin Invest. 2005 Nov;115(11):3250–3255. doi: 10.1172/JCI26197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramratnam B, Ribeiro R, He T, et al. Intensification of antiretroviral therapy accelerates the decay of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and decreases, but does not eliminate, ongoing virus replication. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Jan 1;35(1):33–37. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun TW, Justement JS, Moir S, et al. Decay of the HIV reservoir in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy for extended periods: implications for eradication of virus. J Infect Dis. 2007 Jun 15;195(12):1762–1764. doi: 10.1086/518250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams SA, Greene WC. Regulation of HIV-1 latency by T-cell activation. Cytokine. 2007 Jul;39(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quivy V, De Walque S, Van Lint C. Chromatin-associated regulation of HIV-1 transcription: implications for the development of therapeutic strategies. Subcell Biochem. 2007;41:371–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verdin E, Paras P, Jr, Van Lint C. Chromatin disruption in the promoter of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 1993 Aug;12(8):3249–3259. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coull JJ, Romerio F, Sun JM, et al. The human factors YY1 and LSF repress the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat via recruitment of histone deacetylase 1. J Virol. 2000 Aug;74(15):6790–6799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6790-6799.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams SA, Chen LF, Kwon H, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Verdin E, Greene WC. NF-kappaB p50 promotes HIV latency through HDAC recruitment and repression of transcriptional initiation. EMBO J. 2006 Jan 11;25(1):139–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He G, Margolis DM. Counterregulation of chromatin deacetylation and histone deacetylase occupancy at the integrated promoter of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the HIV-1 repressor YY1 and HIV-1 activator Tat. Mol Cell Biol. 2002 May;22(9):2965–2973. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.2965-2973.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai K, Okamoto T. Transcriptional repression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by AP-4. J Biol Chem. 2006 May 5;281(18):12495–12505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams SA, Kwon H, Chen LF, Greene WC. Sustained induction of NF-kappaB is required for efficient expression of latent human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007 Jun;81(11):6043–6056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02074-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lusic M, Marcello A, Cereseto A, Giacca M. Regulation of HIV-1 gene expression by histone acetylation and factor recruitment at the LTR promoter. EMBO J. 2003 Dec 15;22(24):6550–6561. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thierry S, Marechal V, Rosenzwajg M, et al. Cell cycle arrest in G2 induces human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcriptional activation through histone acetylation and recruitment of CBP, NF-kappaB, and c-Jun to the long terminal repeat promoter. J Virol. 2004 Nov;78(22):12198–12206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12198-12206.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ylisastigui L, Archin NM, Lehrman G, Bosch RJ, Margolis DM. Coaxing HIV-1 from resting CD4 T cells: histone deacetylase inhibition allows latent viral expression. Aids. 2004 May 21;18(8):1101–1108. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehrman G, Hogue IB, Palmer S, et al. Depletion of latent HIV-1 infection in vivo: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet. 2005 Aug 13-19;366(9485):549–555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archin NM, Espeseth A, Parker D, Cheema M, Hazuda D, Margolis DM. Expression of latent HIV induced by the potent HDAC inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009 Feb;25(2):207–212. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon G, Moog C, Obert G. Valproic acid reduces the intracellular level of glutathione and stimulates human immunodeficiency virus. Chem Biol Interact. 1994 Jun;91(2-3):111–121. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witvrouw M, Schmit JC, Van Remoortel B, et al. Cell type-dependent effect of sodium valproate on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997 Jan 20;13(2):187–192. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Archin NM, Eron JJ, Palmer S, et al. Valproic acid without intensified antiviral therapy has limited impact on persistent HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells. Aids. 2008 Jun 19;22(10):1131–1135. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fd6df4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sagot-Lerolle N, Lamine A, Chaix ML, et al. Prolonged valproic acid treatment does not reduce the size of latent HIV reservoir. Aids. 2008 Jun 19;22(10):1125–1129. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282fd6ddc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siliciano JD, Lai J, Callender M, et al. Stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in patients receiving valproic acid. J Infect Dis. 2007 Mar 15;195(6):833–836. doi: 10.1086/511823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carta S, Tassi S, Semino C, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors prevent exocytosis of interleukin-1beta-containing secretory lysosomes: role of microtubules. Blood. 2006 Sep 1;108(5):1618–1626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golay J, Cuppini L, Leoni F, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor ITF2357 has anti-leukemic activity in vitro and in vivo and inhibits IL-6 and VEGF production by stromal cells. Leukemia. 2007 Sep;21(9):1892–1900. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy P, Sun Y, Toubai T, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition modulates indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-dependent DC functions and regulates experimental graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jul;118(7):2562–2573. doi: 10.1172/JCI34712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leoni F, Fossati G, Lewis EC, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor ITF2357 reduces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro and systemic inflammation in vivo. Mol Med. 2005 Jan-Dec;11(1-12):1–15. doi: 10.2119/2006-00005.Dinarello. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oldoni T, Furlan A, Monznani V, Dinarello CA. Decreased whole blood cytokine production during a phase I trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor ITF2357. Cytokine. 2009;48:120. abs. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vojinovic J, Dinarello CA, Damjanov N, Oldoni T. Safety and efficacy of oral ITF2357 in patients with active systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SOJIA). Results of phase II, open label, international, multicentre clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumat. 2008;58:S943. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nold MF, Nold-Petry CA, Pott GB, et al. Endogenous IL-32 controls cytokine and HIV-1 production. J Immunol. 2008 Jul 1;181(1):557–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones P, Bottomley MJ, Carfi A, et al. 2-Trifluoroacetylthiophenes, a novel series of potent and selective class II histone deacetylase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008 Jun 1;18(11):3456–3461. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Netea MG, Nold-Petry CA, Nold MF, et al. Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2009 Mar 5;113(10):2324–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nold-Petry CA, Nold MF, Zepp JA, Kim SH, Voelkel NF, Dinarello CA. IL-32-dependent effects of IL-1beta on endothelial cell functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Mar 10;106(10):3883–3888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813334106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crazzolara R, Johrer K, Johnstone RW, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors potently repress CXCR4 chemokine receptor expression and function in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2002 Dec;119(4):965–969. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta SK, Lysko PG, Pillarisetti K, Ohlstein E, Stadel JM. Chemokine receptors in human endothelial cells. Functional expression of CXCR4 and its transcriptional regulation by inflammatory cytokines. J Biol Chem. 1998 Feb 13;273(7):4282–4287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heredia A, Gilliam B, DeVico A, et al. CCR5 density levels on primary CD4 T cells impact the replication and Enfuvirtide susceptibility of R5 HIV-1. Aids. 2007 Jun 19;21(10):1317–1322. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32815278ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynes J, Portales P, Segondy M, et al. CD4+ T cell surface CCR5 density as a determining factor of virus load in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2000 Mar;181(3):927–932. doi: 10.1086/315315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reynes J, Portales P, Segondy M, et al. CD4 T cell surface CCR5 density as a host factor in HIV-1 disease progression. Aids. 2001 Sep 7;15(13):1627–1634. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fear WR, Kesson AM, Naif H, Lynch GW, Cunningham AL. Differential tropism and chemokine receptor expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in neonatal monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages, and placental macrophages. J Virol. 1998 Feb;72(2):1334–1344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1334-1344.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rana S, Besson G, Cook DG, et al. Role of CCR5 in infection of primary macrophages and lymphocytes by macrophage-tropic strains of human immunodeficiency virus: resistance to patient-derived and prototype isolates resulting from the delta ccr5 mutation. J Virol. 1997 Apr;71(4):3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3219-3227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connor RI, Sheridan KE, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau NR. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1--infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997 Feb 17;185(4):621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dinoso JB, Kim SY, Wiegand AM, et al. Treatment intensification does not reduce residual HIV-1 viremia in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jun 9;106(23):9403–9408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903107106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morselli PL, Franco-Morselli R. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs in adults. Pharmacol Ther. 1980;10(1):65–101. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(80)90009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ylisastigui L, Coull JJ, Rucker VC, et al. Polyamides reveal a role for repression in latency within resting T cells of HIV-infected donors. J Infect Dis. 2004 Oct 15;190(8):1429–1437. doi: 10.1086/423822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quivy V, Adam E, Collette Y, et al. Synergistic activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter activity by NF-kappaB and inhibitors of deacetylases: potential perspectives for the development of therapeutic strategies. J Virol. 2002 Nov;76(21):11091–11103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11091-11103.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marban C, Suzanne S, Dequiedt F, et al. Recruitment of chromatin-modifying enzymes by CTIP2 promotes HIV-1 transcriptional silencing. EMBO J. 2007 Jan 24;26(2):412–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malcolm T, Chen J, Chang C, Sadowski I. Induction of chromosomally integrated HIV-1 LTR requires RBF-2 (USF/TFII-I) and Ras/MAPK signaling. Virus Genes. 2007 Oct;35(2):215–223. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Archin NM, Keedy KS, Espeseth A, Dang H, Hazuda DJ, Margolis DM. Expression of latent human immunodeficiency type 1 is induced by novel and selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Aids. 2009 Sep 10;23(14):1799–1806. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ec1dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Alvarez S, Gordon-Alonso M, et al. Histone deacetylase 6 regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Mol Biol Cell. 2005 Nov;16(11):5445–5454. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]