Abstract

Purpose

Antagonists to A3 adenosine receptors (ARs) lower mouse intraocular pressure (IOP), but extension to humans is limited by species variability. We tested whether the specific A3AR antagonist MRS 1292, designed to cross species, mimicks the effects of other A3AR antagonists on cultured human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial (NPE) cells and mouse IOP.

Methods

NPE cell volume was monitored by electronic cell sorting. Mouse IOP was measured with the Servo-Null Micropipette System.

Results

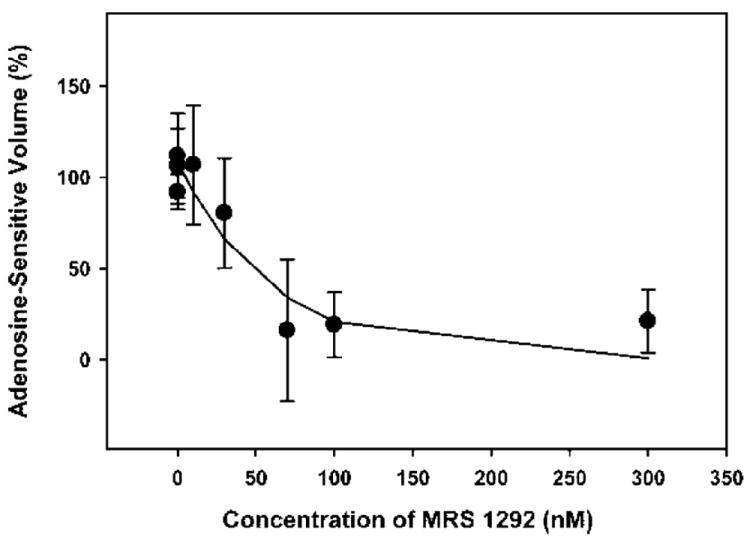

Adenosine triggered A3AR-mediated shrinkage of human NPE cells. Shrinkage was blocked by MRS 1292 (IC50 = 42 ± 11 nM, p < 0.01) and by another A3AR antagonist effective in this system, MRS 1191. Topical application of the A3AR agonist IB-MECA increased mouse IOP. MRS 1292 reduced IOP by 4.0 ± 0.8 mmHg at 25-μM droplet concentration (n = 10, p < 0.005).

Conclusions

MRS 1292 inhibits A3AR-mediated shrinkage of human NPE cells and reduces mouse IOP, consistent with its putative action as a cross-species A3 antagonist.

Keywords: A3 adenosine receptors, aqueous humor inflow, Cl− channels, intraocular pressure, MRS 1292

INTRODUCTION

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is determined by the rate of inflow of aqueous humor across the ciliary epithelium and the resistance to outflow from the anterior chamber. At fixed outflow resistance, an increase in inflow will increase IOP until the sum of the pressure-dependent and pressure-independent outflows matches inflow. Many transport components underlying inflow are known (Fig. 1), but their regulation is poorly understood. For example, the normal 50–60% fall in ciliary epithelial secretion of aqueous humor during sleep remains unexplained.1 Clarifying the mechanisms and regulation of aqueous humor formation can lead to novel strategies for lowering IOP, the only intervention known to retard the onset and progression of blindness in glaucoma.2-4

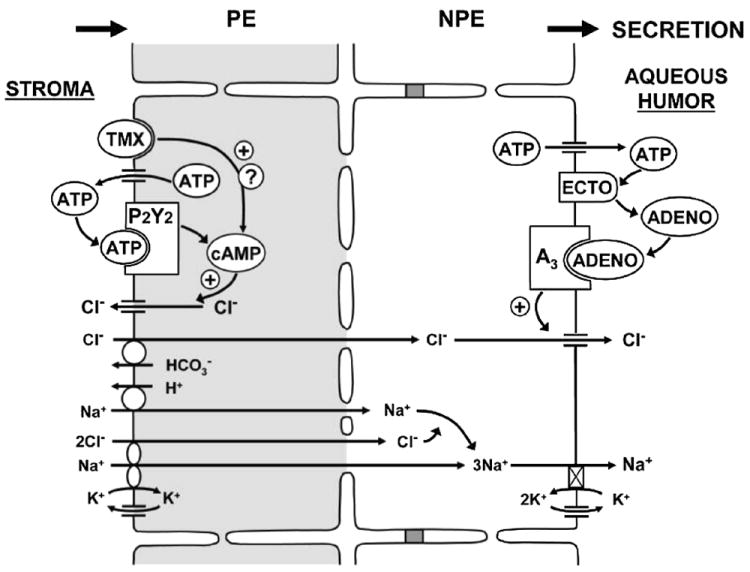

FIGURE 1.

Purinergic regulation of inflow. NaCl is thought to be taken up from the stroma by Na+-K+-2Cl− symports and Na+/H+ and antiports of the PE cells, to permeate gap junctions into the NPE cells and to be released into the aqueous humor by Na+,K+- activated ATPase and Cl− channels of the NPE cells.44 ATP released by PE cells can trigger production of cAMP, which acts directly on maxi-Cl− channels to enhance Cl− return to the stroma, thereby reducing net secretion.5,34 ATP-stimulated recycling is enhanced by the anti-estrogen tamoxifen.33 At the opposite tissue surface, ATP released by NPE cells can be metabolized to adenosine that, by stimulating A3-regulated Cl− channels, can increase net secretion.21,22,26

Many hormones, drugs, and signaling cascades have been reported to modify inflow.5 Purinergic modulation, especially by A3 adenosine receptors (A3ARs), is of particular interest because of its likely physiologic6-8 and pathophysiologic importance.9,10 A3 adenosine receptors upregulate Cl− channels of the nonpigmented ciliary epithelial (NPE) cell layer abutting the aqueous humor in vitro, an action expected to increase inflow and IOP in vivo. As predicted, A3AR agonists increase, and A3AR antagonists decrease, IOP in mice.6

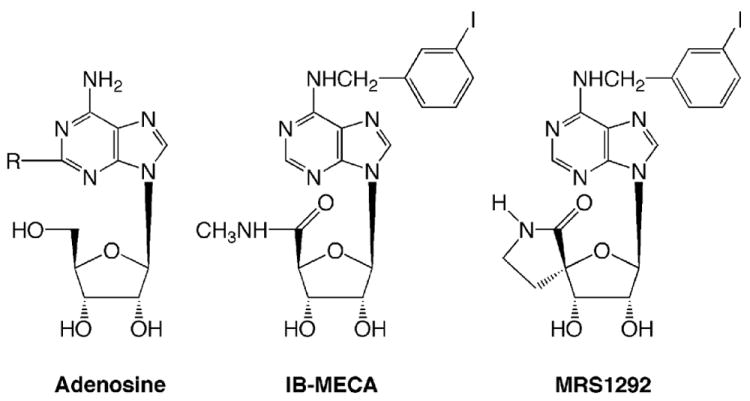

Although the results obtained with A3AR antagonists are promising, striking species differences have been noted in adenosine-receptor pharmacology, especially for antagonists to A3ARs.11,12 Highly selective and potent A3AR antagonists have been unavailable for non-primate species.13-15 In contrast to the species diversity of responses to antagonists, adenosine agonists characteristically display high affinity across species.16 Recently, structural modification of the highly specific, cross-species agonist IB-MECA17-20 has been found to retain high affinity to A3ARs, but with zero efficacy.13 This new A3AR antagonist, a cyclized 4′,5′ -uronamide derivative (MRS 1292; Fig. 2) displays Ki values at both human A1 and A2A receptors of >10,000 nM (Jacobson et al., unpublished observations). Because the Ki value at the human A3 receptor is 29 nM (compound 14),13 this compound is highly selective for the A3 receptor. However, the efficacy across species remains to be tested.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of the physiologic agonist adenosine, the full agonist IB-MECA, and the current nucleoside derivative MRS 1292, an antagonist of A3ARs.

In the current study, we have tested the effects of MRS 1292 on human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial (NPE) cells, a potential therapeutic target, and the mouse, the most promising species available for transgenic studies of the molecular pharmacology and genetics of glaucoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Strategies

We chose to test the effects of MRS 1292 on cultured human NPE cells for two reasons. First, human cells in vitro are expected to mimic the functional properties of human NPE cells in vivo more closely than other species. Second, A3 receptors are the only ARs that regulate Cl− channels and cell volume in these cells,21 simplifying the experimental protocol. Under baseline conditions, there is little tonic activity of A3 receptors in these cells.21,22 We can, however, stimulate all ARs nonselectively with the physiologic agonist adenosine and determine the effects of MRS 1292 on the changes in cell volume uniquely triggered by A3ARs.

We chose to test MRS 1292 on the mouse, again for two reasons. Transgenic mice provide a convenient opportunity for studying the molecular physiology and pharmacology in the living animal (e.g., Avila et al.7). Second, measurement of IOP permitted us to assess the effects of MRS 1292 on the target parameter. However, the adenosine-stimulation protocol was not used in the mouse because it not only stimulates A3 receptors but also activates other ARs that have independent effects on IOP. Here, we directly assessed the effect of MRS 1292 on the living mouse by monitoring IOP before and after drug application.

Cultured NPE Cells

The NPE cells studied were from clone-4, derived from a primary culture of human nonpigmented ciliary epithelium.23 Confluent human NPE cells21 were harvested from a T-75 flask by trypsinization 3–10 days after passage.24,25 An 0.5-ml aliquot of the suspended cells was added to 20 ml of each test solution which included (in mM): 110.0 NaCl, 15.0 HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1- piperazineethanesulfonic acid], 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 30.0 NaHCO3, and 10.0 glucose, at a pH of 7.4 and osmolality of 298–305 mOsm. Gramicidin D (5 μM) was present in all solutions to provide a K+-release pathway so that release of KCl, and secondarily water, was limited solely by Cl− release.24 One aliquot of cells in suspension was untreated and the other three aliquots were exposed in parallel to different experimental solutions on the same day. The same amount of solvent vehicle (DMSO) was added to the control and experimental aliquots, and the order of studying the suspensions was varied to preclude time-dependent artifacts. Cell volume was monitored with a Coulter counter (model ZBI-Channelyzer II, Beckmann Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) with an aperture of 100 μm. The cell volume was measured as the peak of the distribution function.

Cell shrinkage was fit as a function of time (t) to the exponential function:

| (1) |

where Δv∞ (in %) is the steady-state shrinkage and τ (in min) is the time constant of the shrinkage. Fits were generated by nonlinear least-squares regression analysis, allowing both Δv∞ and τ to be variables.26

Mouse Intraocular Pressure

Black Swiss outbred mice of mixed sex, 7–9 weeks old and ~30 g in weight (Taconic, Inc., Germantown, NY, USA) were maintained under 12-hr light-dark illumination cycle and allowed unrestricted access to food and water. All procedures conformed to the ARVO Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice were anesthetised with intraperitoneal ketamine (250 mg/kg) supplemented by topical proparacaine HCl 0.5% (Allergan, Hormigueros, Puerto Rico) for the IOP measurements.

IOP was monitored with the Servo-Null-Micropipette System (SNMS), a highly reliable electro physiologic approach that has been extensively validated and used in previous studies.6,7,27-29 Data reported were obtained from one eye of each mouse studied. Mean values of IOP were calculated by averaging 3–5 min of data acquired at 3 Hz before and after drug application. Thus, each mean was obtained from ~540 to 900 measurements.

Drugs were applied topically in 10-μl drops with an Eppendorf pipette at the stated concentrations. The agents were initially dissolved in DMSO and then added to a saline solution containing benzalkonium chloride to enhance corneal permeabililty. The final droplet solution contained the drugs at the stated concentrations together with ≤0.5% DMSO and 0.0005% benzalkonium chloride at an osmolality of 295–300 mOsm. Control saline solutions (0.9% NaCl) did not contain DMSO and benzalkonium. We have previously found that the DMSO-benzalkonium solution itself does not affect mouse IOP at DMSO concentrations as high as 10% and a benzalkonium concentration of 0.003%.27

Drugs

Adenosine, N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (IB-MECA), MRS 1191, and benzalkonium chloride were purchased from RBI Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). MRS 1292 was synthesized as previously described.13

RESULTS

Cultured Human NPE Cells

Cultured human NPE cells suspended in control solution containing gramicidin D displayed slight shrinkage over the 60 min of study (Δv∞ = 1.2 ± 0.1%; Fig. 3). Adenosine (10 μM) increased the degree of shrinkage several-fold. MRS 1292 significantly reduced the magnitude (Δv∞ = 1.9 ± 0.2%, p < 0.001 by Student’s t test; Fig. 3) and slowed the rate of the adenosine-triggered shrinkage. In the presence of MRS 1292, the time constant (τ) of the shrinkage was prolonged from 3.8 ± 0.6 to 11.7 ± 2.6 min (p < 0.02). In the presence of the 1,4-dihydropyridine A3 antagonist MRS 1191,11 adenosine-treated cells displayed no exponential shrinkage. MRS 1191 has been previously used successfully to antagonize human,11,21,22 rat,11 and mouse6 ARs. Further details are provided in the legend to Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

A3AR antagonists inhibit adenosine-triggered shrinkage of cultured human NPE cells. Cells were suspended in isotonic (Iso) solution containing gramicidin (Gram). Adenosine (10 μM) triggered shrinkage. Both the novel A3AR antagonist MRS 1292 (100 nM) and the established antagonist MRS 119121 (100 nM) prevented that shrinkage (N = 10, passages 10–14). Cells were pretreated with the antagonists for 2 min before initiating the measurements. Solid curves are nonlinear least-square fits to Eq. (1): control (Δv∞ = 1.2 ± 0.1%; τ = 4.5 ± 1.7 min), adenosine (Δv∞ = 4.2 ± 0.2%; τ = 3.8 ± 0.6 min), and adenosine + MRS 1292 (Δv∞ = 1.9 ± 0.2%; τ = 11.7 ± 2.6 min). The symbols Δv∞ and τ symbolize the steady-state shrinkage and the time constant of that shrinkage, respectively. Cells exposed to adenosine and MRS 1191 did not display exponential shrinkage and their volumes could not be fit to Eq. (1) so that the data points are connected by interrupted lines.

The concentration-response relationship for the action of MRS 1292 on adenosine-triggered shrinkage is presented in Figure 4 (n = 19, including the experiments of Fig. 3). The IC50 estimated from the exponential fit was 41 ± 11 nM.

FIGURE 4.

Concentration-response relationship of MRS 1292. The cell shrinkages were measured after 60 min of exposure, as in the experiments of Figure 3, and corrected for the shrinkage displayed by the parallel control aliquots of cells. The curve was generated from an exponential two-parameter fit of the results.

INTRAOCULAR PRESSURE OF LIVING MICE

Topical addition of droplets containing 25 μM of the putative antagonist MRS 1292 produced a maximum reduction in IOP by 8–19 min (mean 15 ± 1 min) of 4.4 ± 0.8 mm Hg (n = 10, p < 0.005, Student’s t test; Fig. 5). In comparison, addition of the same volume of saline at the same osmolality produced no significant change in IOP (−0.3 ± 1.2 mmHg, n = 6, p > 0.8) 14 min later.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of topical control physiologic saline (n = 6), the antagonist MRS 1292 (at a droplet concentration of 25 μM, n = 10), and of the agonist IB-MECA at droplet concentrations of 14 nM (n = 5), 140 nM (n = 6), and 1,400 nM (n = 4) on IOP of living mice. Values are means ± SEs.

In agreement with our previous observations,6,7 the A3AR agonist IB-MECA produced a rapid increase in IOP of 4.6 ± 1.6 mmHg (n = 6, p < 0.05 by Student’s t test; Fig. 5) at 140 nM. At a 10-fold lower concentration, IB-MECA increased IOP by 2.2 ± 0.5 mm Hg (p < 0.02; Fig. 5). In contrast, at a very high droplet concentration (1400 nM), IB-MECA exerted no significant effect (−1.2 ± 1.9 mmHg; Fig. 5), presumably because of cross-reaction with A2AARs.6,30-32

DISCUSSION

Purine receptors modulate cell activity in the outflow and inflow pathways of the aqueous humor. Regulation of inflow reflects yin-yang modulation of ciliary epithelial secretion.33 Activating PE-cell ATP receptors can reduce,25,33,34 and activating NPE-cell ARs can increase,21,22,26 net secretion, leading to corresponding changes in IOP. The current work focuses on the development of cross-species A3 antagonists potentially useful in glaucoma by reducing inflow and IOP.

The strategy of exploiting A3 antagonists was initially suggested by in vitro evidence that adenosine stimulates A3AR-mediated Cl− channels in freshly dissociated bovine and cultured human NPE cells and in NPE cells of rabbit ciliary epithelium.21,22,26 The in vitro results led to the prediction that agonists of A3ARs would raise, and antagonists of A3ARs would lower, IOP. This prediction was subsequently confirmed by IOP measurements in living mice.6,7

Modulation of IOP by A3ARs is likely of both physiologic and pathophysiologic importance. Knockout of A3ARs reduces baseline levels of IOP,7 and topical application of A3AR antagonists to nonhuman primates lowers IOP.8 As a potential link to clinical glaucoma, A3ARs of NPE cells are upregulated by an order of magnitude in the pseudoexfoliation syndrome, a major cause of secondary open-angle glaucoma.9 The aqueous humor concentration of adenosine is also elevated in glaucomatous patients,10 but whether the association represents a cause or an effect is unknown.

In previous studies, A3 antagonists were found both to block adenosine-triggered shrinkage of cultured human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells21 and to lower intraocular pressure.6-8 In those studies, non-purine antagonists of the receptor, such as the dihydropyridine MRS 1191 and the pyridine MRS 1523, were used. Most of these heterocyclic derivatives suffer from a lack of generality of the A3 affinity across species. For example, note the high ratio of the binding affinities of rat to human A3 receptors in Table 1. This nongenerality of antagonist selectivity has limited the ability to evaluate the potential clinical relevance of the known A3 antagonists in animal models, in which the A3 selectivity of the compounds would be greatly diminished. However, the current antagonist MRS 1292 is a nucleoside derivative13 structurally related to the agonist IB-MECA, whose high affinity of IB-MECA at A3 receptors extends across species. MRS 1292 is A3-receptor-selective in both the human and the rat.13 Note that the ratio of rat-to-human affinities for A3 receptors is similar for MRS 1292 and selective A3 agonists (Table 1). In this study, we have found that MRS 1292 acts as an A3 adenosine-receptor antagonist in mimicking effects of nonpurine A3 antagonists on cultured human NPE cells and mouse IOP.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the Binding Affinities (Ki Values in nM) of Various A3 Adenosine Receptor Ligands in Rat (r) and Human (h) Species. (The Compounds are Selective in Binding to the Human A3 Adenosine Receptor, Unless Noted.)

| Compound | Ratio (r/h) | Ki hA3 | Ki rA3 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antagonists (non-nucleoside) | ||||

| MRS 1067 | 10 | 561 | 5,500 | 37 |

| MRS 1097 | 39 | 108 | 4,160 | 38 |

| MRS 1191 | 45 | 31.4 | 1,420 | 39,40 |

| MRS 1220 | >1000 | 0.65 | >1000 | 39,40 |

| MRS 1523 | 6.0 | 18.9 | 113 | 40 |

| MRE 3008F20 | >30,000 | 0.29 | >10,000 | 41 |

| XACa | 760 | 38 | 29,000 | 41,42 |

| OT-7999 | >16,000 | 0.61 | >10,000 | 8 |

| Agonists (nucleoside) | ||||

| IB-MECA | 0.61 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 39,43 |

| Cl-IB-MECA | 0.72 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 13,39 |

| DBXRM | 0.28 | 816 | 229 | 13,39 |

| Antagonist (nucleoside) | ||||

| MRS1292 | 1.7 | 29.3 | 49 | 13 |

Nonselective.

The precise concentration of MRS 1292 in the aqueous humor resulting from our topical applications is unknown: The cornea is a significant barrier to topical delievery of nucleosides into the aqueous humor,35 but the mouse anterior chamber volume is only ~2 μl,27 so that we cannot readily measure drug concentration in the aqueous humor. To estimate an approximate range, we have calculated a “penetrance,” defined as the ratio of the the published Ki value at receptors in vitro to the minimally effective droplet concentration, for a number of adenosine agonists and antagonists. This penetrance ranges from 1:100 to 1:1000 for purinergic drugs we have tested in the mouse and is not very different from the drug penetrance of 1:100 for agents applied topically to rabbits and primates, as well.6 This rule of thumb also applies to acylguanidine blockers and bumetanide, whose topical effects we have also studied in the mouse eye.28 Thus, the approximately 1:1000 penetrance we have noted with MRS 1292 in the present experiments is consistent with our past studies of mouse intraocular pressure.

The structural basis for the conversion of a full agonist, IB-MECA, into an antagonist is in the addition of a spirolactam ring, which rigidifies the ribose moiety.13 This has been proposed to preclude a required conformational change of the ribose moiety in order for the receptor-bound nucleoside to activate the A3 receptor.36 A conformational change within the receptor involving transmembrane helical domain 6 and a conserved tryptophan residue in that helix has already been proposed, based on mutagenesis and molecular modeling studies. Thus, this conformationally constrained ligand (i.e., the nucleoside MRS 1292) behaves as an A3 receptor antagonist in the mouse eye, as in studies of the heterologously expressed recombinant human A3 receptor. With the current evidence that MRS1292 works in the mouse, we suggest that this compound may be the antagonist of choice for additional animal testing, both for more fully understanding the role of A3 ARs in regulating IOP and for potentially using A3 antagonists in glaucoma treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by research grants EY 08343 (MMC), EY013624 (MMC), and core grant EY01583 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest: R.A.S., K.A.J., and M.M.C. are co-inventors on patent applications and issued patents assigned to the University of Pennsylvania and NIH dealing with the use of A3 adenosine-receptor antagonists as agents in treating glaucoma. K.A.J. is a co-inventor of MRS 1292 on a patent assigned to the National Institutes of Health. The other authors have no commercial conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Hui Yang, Department of Physiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Marcel Y. Avila, Department of Physiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Kim Peterson-Yantorno, Department of Physiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Miguel Coca-Prados, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Richard A. Stone, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Kenneth A. Jacobson, Molecular Recognition Section, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Mortimer M. Civan, Department of Physiology and Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

References

- 1.Brubaker RF. Clinical measurement of aqueous dynamics: Implications for addressing glaucoma. In: Civan MM, editor. Eye’s Aqueous Humor: From Secretion to Glaucoma. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 234–284. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:498–505. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:487–497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The AGIS investigators. The advanced glaucoma intervention study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Do C-W, Civan MM. Basis of chloride transport in ciliary epithelium. J Membr Biol. 2004;200:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avila MY, Stone RA, Civan MM. A1-, A2A- and A3-subtype adenosine receptors modulate intraocular pressure in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:241–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avila MY, Stone RA, Civan MM. Knockout of A3 adenosine receptors reduces mouse intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3021–3026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamura T, Kurogi Y, Hashimoto K, Sato S, Nishikawa H, Kiryu K, Nagao Y. Structure-activity relationships of adenosine A3 receptor ligands: new potential therapy for the treatment of glaucoma. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3775–3779. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Decking U, Haubs D, Kruse FE, Junemann A, Coca-Prados M, Naumann GO. Selective upregulation of the A3 adenosine receptor in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome and glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2023–2034. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daines BS, Kent AR, McAleer MS, Crosson CE. Intraocular adenosine levels in normal and ocular-hypertensive patients. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2003;19:113–119. doi: 10.1089/108076803321637645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson KA, Park KS, Jiang JL, Kim YC, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Ji XD. Pharmacological characterization of novel A3 adenosine receptorselective antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linden J. Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:775–787. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao ZG, Kim SK, Biadatti T, Chen W, Lee K, Barak D, Kim SG, Johnson CR, Jacobson KA. Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4471–4484. doi: 10.1021/jm020211+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. 2-Chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine, adenosine A1 receptor agonist, antagonizes the adenosine A3 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;443:39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Romagnoli R, Merighi S, Varani K, Borea PA, Spalluto G. A3 adenosine receptor ligands: history and perspectives. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:103–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200003)20:2<103::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park KS, Hoffmann C, Kim HO, Padgett WL, Brambilla R, Motta C, Abbracchio MP, Jacobson KA. Activation and desensitization of rat A3-adenosine receptors by selective adenosine derivatives and xanthine-7-ribosides. Drug Dev Res. 1998;44:97–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2299(199806/07)44:2/3<97::AID-DDR7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HO, Ji XD, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5’-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takano H, Bolli R, Black RG, Jr, Kodani E, Tang XL, Yang Z, Bhattacharya S, Auchampach JA. A1 or A3 adenosine receptors induce late preconditioning against infarction in conscious rabbits by different mechanisms. Circ Res. 2001;88:520–528. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong H, Shlykov SG, Molina JG, Sanborn BM, Jacobson MA, Tilley SL, Blackburn MR. Activation of murine lung mast cells by the adenosine A3 receptor. J Immunol. 2003;171:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson KA, Kim SK, Costanzi S, Gao ZG. Purine receptors: GPCR structure and agonist design. Molecular Interventions. 2004;4:337–347. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.6.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Carré DA, McGlinn AM, Coca-Prados M, Stone RA, Civan MM. A3 adenosine receptors regulate Cl− channels of nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C659–C666. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.3.C659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carré DA, Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Civan MM. Similarity of A3-adenosine and swelling-activated Cl(-) channels in nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C440–C451. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Vasallo P, Ghosh S, Coca-Prados M. Expression of Na,K-ATPase alpha subunit isoforms in the human ciliary body and cultured ciliary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1989;141:243–252. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Civan MM, Coca-Prados M, Peterson-Yantorno K. Pathways signaling the regulatory volume decrease of cultured nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:2876–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischhauer JC, Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Civan MM. PGE2, Ca2+, and cAMP mediate ATP activation of Cl− channels in pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1614–C1623. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carré DA, Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Civan MM. Adenosine stimulates Cl− channels of nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1354–1361. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avila MY, Carré DA, Stone RA, Civan MM. Reliable measurement of mouse intraocular pressure by a servo-null micropipette system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1841–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avila MY, Seidler RW, Stone RA, Civan MM. Inhibitors of NHE-1 Na+/H+ exchange reduce mouse intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1897–1902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitsamer HA, Kiel JW, Harrison JM, Ransom NL, McKinnon SJ. Tonopen measurement of intraocular pressure in mice. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crosson CE. Adenosine receptor activation modulates intraocular pressure in rabbits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:320–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crosson CE, Gray T. Characterization of ocular hypertension induced by adenosine agonists. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1833–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian B, Gabelt BT, Crosson CE, Kaufman PL. Effects of adenosine agonists on intraocular pressure and aqueous humor dynamics in cynomolgus monkeys. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:979–989. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell CH, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Civan MM. Tamoxifen and ATP synergistically activate Cl- release by cultured bovine pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. J Physiol. 2000;525((Pt) 1):183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Do C-W, Peterson-Yantorno K, Mitchell CH, Civan MM. cAMP-Activated Maxi-Cl- Channels in native bovine pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1003–1011. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00175.2004. Epub 2004 Jun 09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien WJ, Edelhauser HF. The corneal penetration of trifluorothymidine, adenine arabinoside, and idoxuridine: a comparative study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:1093–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao ZG, Chen A, Barak D, Kim SK, Muller CE, Jacobson KA. Identification by site-directed mutagenesis of residues involved in ligand recognition and activation of the human A3 adenosine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19056–19063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110960200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller CE. A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2001;1:417–427. doi: 10.2174/1389557510101040417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rhee AM, Jiang JL, Melman N, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Interaction of 1,4-dihydropyridine and pyridine derivatives with adenosine receptors: selectivity for A3 receptors. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2980–2989. doi: 10.1021/jm9600205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptors: novel ligands and paradoxical effects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li AH, Moro S, Forsyth N, Melman N, Ji XD, Jacobson KA. Synthesis, CoMFA analysis, and receptor docking of 3,5-diacyl-2, 4-dialkylpyridine derivatives as selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1999;42:706–721. doi: 10.1021/jm980550w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varani K, Merighi S, Gessi S, Klotz KN, Leung E, Baraldi PG, Cacciari B, Romagnoli R, Spalluto G, Borea PA. [3H]MRE 3008F20: a novel antagonist radioligand for the pharmacological and biochemical characterization of human A3 adenosine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:968–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji X-d, von Lubitz D, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Species differences in ligand affinity at central A3-adenosine receptors. Drug Devel Res. 1994;33:51–59. doi: 10.1002/ddr.430330109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao ZG, Blaustein JB, Gross AS, Melman N, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted adenosine derivatives: selectivity, efficacy, and species differences at A3 adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Civan MM, Macknight AD. The ins and outs of aqueous humour secretion. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]