Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a fundamental role in innate immunity and provide a link between innate and adaptive responses to an allograft; however, whether the development of acute and chronic allograft rejection requires TLR signaling is unknown. Here, we studied TLR signaling in a fully MHC-mismatched, life-sustaining murine model of kidney allograft rejection. Mice deficient in the TLR adaptor protein MyD88 developed donor antigen-specific tolerance, which protected them from both acute and chronic allograft rejection and increased their survival after transplantation compared with wild-type controls. Administration of an anti-CD25 antibody to MyD88-deficient recipients depleted CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells and broke tolerance. In addition, defective development of Th17 immune responses to alloantigen both in vitro and in vivo occurred, resulting in an increased ratio of Tregs to Th17 effectors. Thus, MyD88 deficiency was associated with an altered balance of Tregs over Th17 cells, promoting tolerance instead of rejection. This study provides evidence that targeting innate immunity may be a clinically relevant strategy to facilitate transplantation tolerance.

The success of transplantation is limited by the requirement to use lifelong immunosuppression to prevent allograft rejection. Current immunosuppression strategies are both incompletely effective at preventing acute and chronic rejection1,2 and result in complications, which limit graft and patient survival.3–5 Immunosupression primarily targets the adaptive alloimmune response; however, recent data have revealed a likely requirement for innate immunity in allograft rejection in both mediating inflammation and promoting an effective adaptive alloimmune response.6–8

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are innate immune receptors expressed by a variety of immune cell types and a number of nonimmune cells, including kidney tubular epithelial cells9 and glomerular endothelial cells.10,11 TLRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns that are present on microorganisms and also recognize endogenous ligands released from damaged tissue.9 All TLRs, except TLR3, can signal through an adaptor molecule, myeloid differentiation primary response gene (88) (MyD88), which leads to nuclear translocation of NF-κB, with consequent upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) and chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2); this upregulation contributes to local inflammation and leukocyte accumulation.

Engagement of TLRs initiates an innate immune response that subsequently promotes the development of effective adaptive immunity12 through activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including upregulation of MHC class II antigens, costimulatory molecules, chemokines, and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23). After organ transplantation, these TLR-driven innate immune responses are important for the promotion of ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)9 and the initiation of adaptive alloimmunity, which causes acute and chronic rejection.

Significant and nonredundant roles have been shown for TLR2 and TLR4 signaling in kidney IRI.9,13,14 We previously reported that IRI resulted in upregulation of TLR4 and its endogenous ligands high-mobility group protein B1(HMGB1), hyaluronan, and biglycan within the kidney and that TLR4 activation through the MyD88 pathway is a key mediator of kidney IRI.9 We subsequently showed potential for blockade of the endogenous TLR ligand HMGB1 through TLR4 signaling to prevent kidney IRI.15 In humans, the presence of a hypofunctioning TLR4 polymorphism has been associated with protection from IRI, manifesting as a reduced incidence of delayed graft function after kidney transplantation.16

Given the importance of TLR/MyD88 signaling in kidney IRI, the association between reduced TLR4 function and improved outcomes in human kidney transplantation, and the emerging roles for innate immunity in modulating adaptive immunity, we hypothesized that TLR signaling through MyD88 is required for the development of kidney allograft rejection. In the current set of experiments, we compared MyD88−/− and wild-type (WT) mice after receipt of life-sustaining fully MHC‐mismatched kidney allografts. We herein present data that show how the absence of TLR signaling by MyD88 protected mice from acute and chronic rejection through the development of donor-specific tolerance.

Results

Absence of MyD88 Signaling Prolongs Kidney Allograft Survival

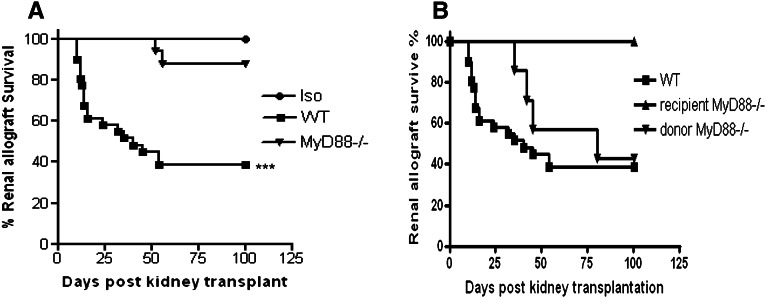

We transplanted BALB/c.MyD88−/−(H2-Kd) kidneys into C57BL/6.MyD88−/− recipients (H2-Kb) as MyD88−/− allografts. Survival to 100 days was observed in all isografts. WT mice rejected their WT allografts with a mean graft survival of 40 days, whereas MyD88−/− allografts displayed prolonged survival (Figure 1A). When MyD88 was absent from recipients, five of five allografts survived to 100 days (Figure 1B). When only the allograft was MyD88-deficient, survival was modestly prolonged over WT allografts; however, only three of seven recipients survived to 100 days (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Absence of MyD88 signaling prolongs kidney allograft survival. (A) Absence of MyD88 signaling in both donor and recipient prolongs kidney allograft survival. Survival to 100 days was observed in all isografts (n=6) and 15 of 17 MyD88−/− allografts (n=17) but only 12 of 31 WT allografts (n=31; ***P<0.001 WT allografts versus MyD88−/− allografts and isografts). (B) When MyD88 was absent from recipients, five of five allografts survived to 100 days (n=5; P<0.05, WT allografts versus MyD88−/− recipients). When only the allograft was MyD88-deficient, three of seven WT recipients survived to 100 days (n=7).

Absence of MyD88 Signaling Protects against Acute Kidney Rejection at Day 14

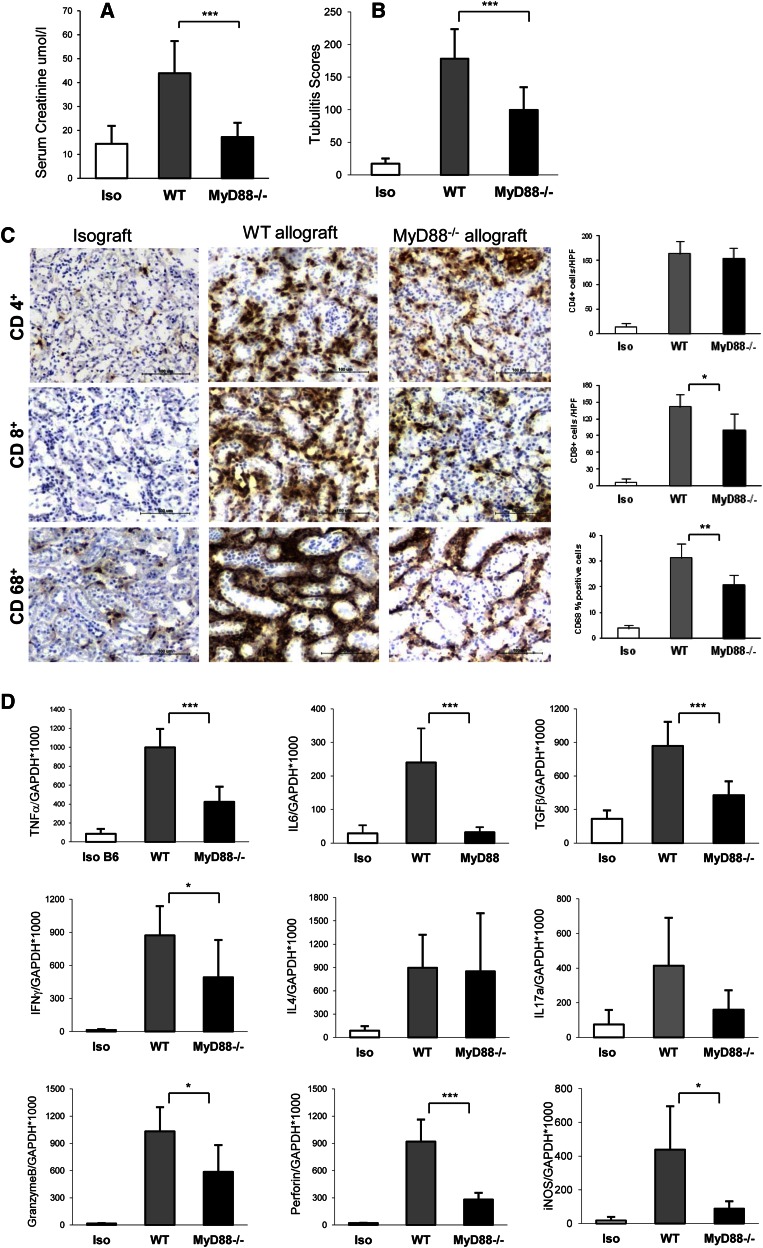

Significant kidney dysfunction in WT allografts was evident and reflected by a tripling of serum creatinine compared with isografts (Figure 2A). Kidney function was preserved in MyD88−/− and recipient MyD88−/− donor MyD88+/+ allografts equally, whereas only partial preservation of function was seen in recipient MyD88+/+ donor MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 1A).

Figure 2.

Absence of MyD88 signaling was protective against acute rejection. (A) Loss of kidney function, as indicated by a significant elevation of serum creatinine, was evident in WT allografts (n=12) but not MyD88−/− allografts (n=9) at day 14 post-transplant compared with isografts (n=5; ***P<0.001). (B) Tubulitis was present in MyD88−/− allografts (n=7), although it was significantly diminished compared with WT allografts (n=9; ***P<0.001). (C) Interstitial infiltrates in the allografts at day 14 after kidney transplant. Representative sections of kidney grafts at day 14 post-transplant were stained for CD4, CD8, CD68, and CD11c by immunochemistry. Substantial infiltration of CD4+ cells was evident in WT and MyD88−/− allografts versus isografts (P<0.001). CD8+ cell infiltration was attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts versus WT allografts (*P<0.05). Significant macrophage (CD68+) accumulation was evident in the WT allografts compared with isografts but significantly reduced in MyD88−/− allografts (**P<0.01). (D) Absence of MyD88 signaling resulted in reduced mRNA expression of proinflammatory and Th1 cytokines and cytotoxic molecules at day 14 after kidney transplant. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Isografts are n=5, WT allografts are n=9, and MyD88−/− allografts are n=7.

WT allografts exhibited severe tubulitis compared with isografts. Tubulitis was present in MyD88−/− allografts and allografts where either donor or recipient was MyD88−/−, although it was significantly diminished compared with WT allografts (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 1B).

Substantial infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells was evident in WT allografts versus isografts (P<0.001) (Figure 2C). CD8+, although not CD4+, cell infiltration was attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 2C). Extensive macrophage (CD68+) accumulation was evident in WT allografts compared with isografts; however, this accumulation was markedly diminished in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 2C).

Reduced Expression of Proinflammatory and Th1 Cytokines and Cytotoxic Molecules in MyD88−/− Allografts at Day 14

WT allografts showed strong upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and TGF-β) and cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17) compared with isografts (Figure 2D). All proinflammatory cytokines and IFN-γ were reduced in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts (Figure 2D), whereas upregulation of IL-4 was of a similar magnitude to the magnitude in WT allografts. MyD88−/− allografts showed a nonsignificant trend to reduced expression of IL-17 compared with WT allografts (P=0.06) (Figure 2D). Cytotoxic molecules (perforin, granzyme, and inducible nitric oxide synthase) are mediators of kidney damage during acute rejection. All were upregulated in WT allografts compared with isografts but attenuated in the absence of MyD88 (Figure 2D).

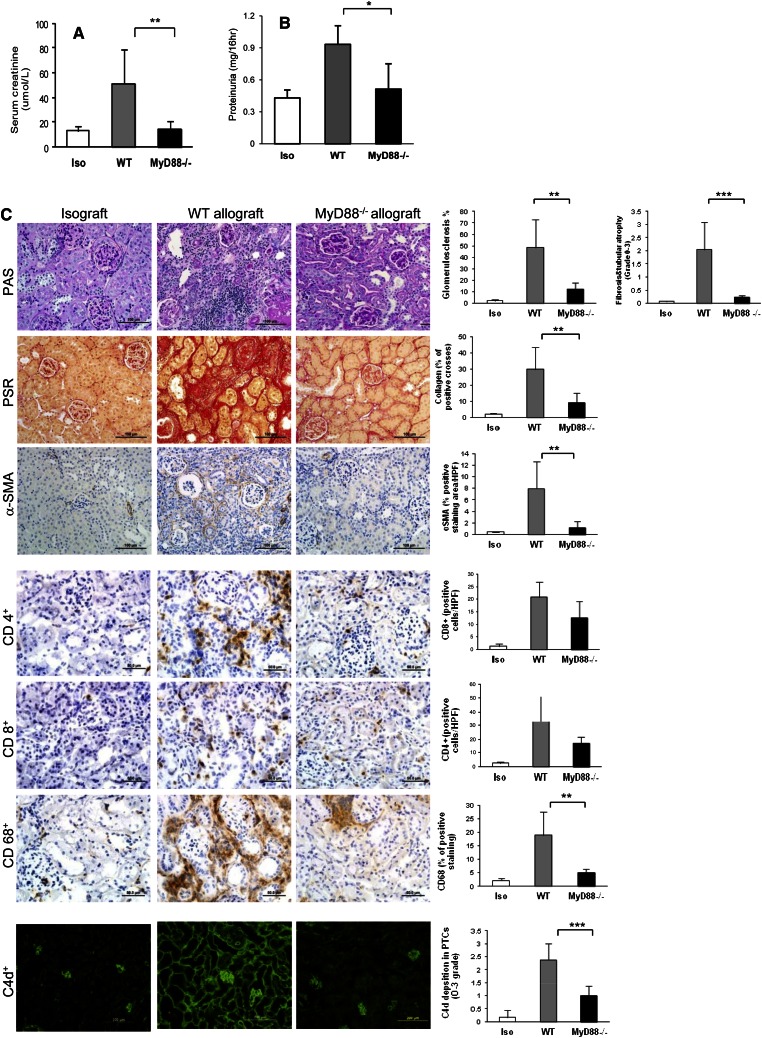

MyD88 Deficiency Is Protective against Chronic Allograft Injury at Day 100 Post-Transplantation

By day 100 post-transplantation, surviving WT mice had developed significant kidney allograft dysfunction, which was evidenced by increased serum creatinine and proteinuria for WT allografts versus isografts (Figure 3, A and B). Kidney function remained normal in MyD88−/− allografts and was comparable with kidney function of isografts. Proteinuria in MyD88−/− allograft mice was similar to isografts and significantly less than WT allografts (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

MyD88 deficiency prevents the allograft from chronic rejection at day 100 after kidney transplant. (A) Serum creatinine was significantly lower in MyD88−/− allografts than WT allografts (**P<0.01). (B) Proteinuria was significantly diminished in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts and not significantly different to isografts (*P<0.05). (C) Illustration of representative sections of the histologic changes on PAS, PSR, and immunochemistry staining for α-SMA, CD4, CD8, CD68, and CD11c and fluorescence staining for C4d in isografts, WT, and MyD88−/− allografts. Significant glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy were evident in WT allografts compared with isografts (P<0.01) and MyD88−/− allografts (**P<0.01). WT allografts had significantly higher expression of collagen than isografts (P<0.01) and MyD88−/− allografts (P<0.01). Significant α-SMA staining was evident throughout the cortex of WT allografts but largely absent in isografts and MyD88−/− allografts (**P<0.01). Interstitial infiltrates in the allograft at day 100 after kidney transplant. The CD4+ and CD8+ infiltrates were significantly increased in WT allografts and to a lesser degree, in MyD88−/− allografts compared with isografts (P<0.05). MyD88−/− allografts had significantly reduced CD68+ cell accumulation compared with WT allografts. Prominent C4d staining was present diffusely in peritubular capillaries in WT allografts at day 100 post-transplant, whereas fluorescence intensity of C4d deposition was significantly diminished in MyD88−/− allografts (***P<0.001). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=5 for isografts; n=8 for each allograft group).

WT allografts developed severe glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy, whereas these changes were absent in isografts and attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 3). To verify interstitial fibrosis, we stained collagen and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). The expression of interstitial collagen and α-SMA was significantly higher in WT allografts versus isografts and significantly reduced in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 3C).

Significant CD4+ and CD8+ cell accumulation was evident in WT allografts compared with isografts (P<0.05), with a modest reduction in MyD88−/− mice compared with WT (Figure 3C). There was a significant increase in CD68+ in WT allografts compared with isografts (P<0.01), which was attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 3C). There was no significant difference between isografts and MyD88−/− mice.

In human kidney transplantation, complement split product C4d deposition in peritubular capillaries (PTCs) is a marker of antibody-mediated rejection and is associated with development of transplant glomerulopathy. Prominent C4d staining was present diffusely in almost all cross-sections of PTCs, with a bright, broad linear pattern in WT allografts (Figure 3C). Fluorescence intensity of C4d deposition in PTCs was significantly reduced in MyD88−/− allografts. Consistent with this result, WT allograft recipients exhibited higher titers of donor-specific antibody, both IgG2a and IgG1 subclasses, compared with MyD88−/− allografts (Supplemental Figure 2).

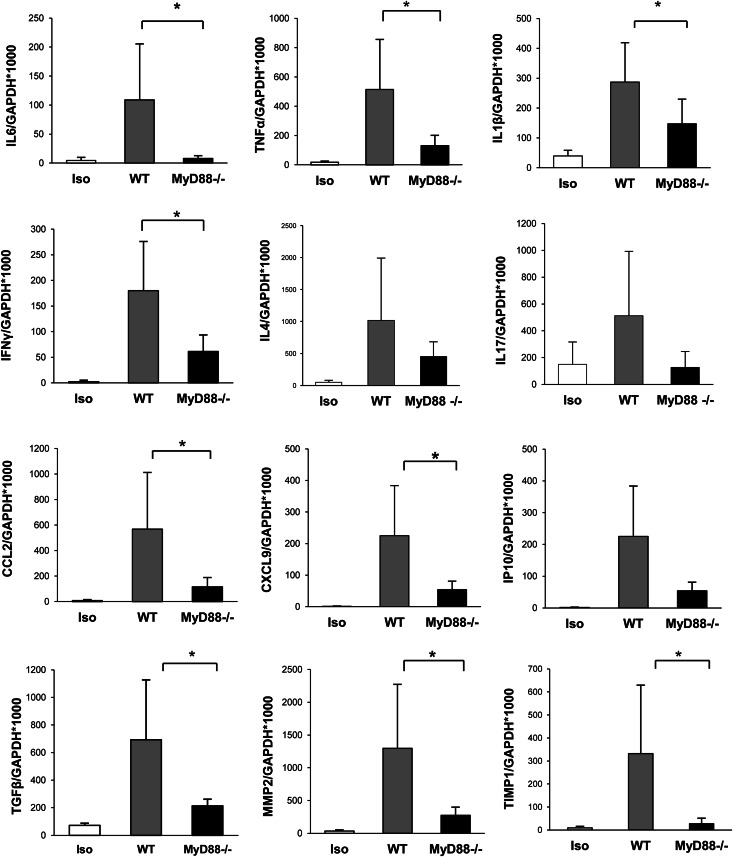

Absence of MyD88 Signaling Results in Reduced mRNA Expression of Proinflammatory and Th1 Cytokines, Chemokines, and Fibrosis-Related Genes

Expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) was upregulated in WT allografts compared with isografts (P<0.01) and partially reduced in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT (Figure 4). IFN-γ mRNA was increased in WT allografts compared with isografts (P<0.001) but not MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 4). IL-4 mRNA expression in WT and MyD88−/− allografts was higher than in isografts (Figure 4). IL-17 expression was upregulated in WT allografts compared with isografts but not MyD88−/− allografts (P=0.08) (Figure 4). Expression of chemokines (CCL2, chemokine [C-X-C motif] ligand 9 [CXCL9], and CXCL10) was significantly higher in WT mice compared with isografts (P<0.05) (Figure 4). MyD88−/− mice showed significantly reduced expression of CCL2 and CXCL9 compared with WT mice (Figure 4), consistent with our findings by immunohistology of a reduction in infiltrating CD68+ cells in MyD88−/− allografts. WT allografts showed a higher expression of fibrosis-related genes (TGF-β, matrix metalloproteinase 2 [MMP2], and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 [TIMP1]) compared with isografts (P<0.01), and these results were attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Absence of MyD88 signaling resulted in reduced mRNA expression of proinflammatory and Th1 cytokines, chemokines, and fibrosis-related genes. IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression was attenuated in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts. IFN-γ mRNA expression was reduced in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts. IL-4 mRNA expression in WT and MyD88−/− allografts was higher than in isografts, with no significant difference between MyD88−/− and WT mice. Upregulated IL-17 expression was evident in WT allografts compared with isografts and reduced in MyD88−/− allografts (P=0.08). CCL2 and CXCL9 expression were significantly reduced in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts. Expression of the fibrosis-related genes TGF-β, MMP2, and TIMP1 were reduced in MyD88−/− allografts versus WT (*P<0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=5 for isografts; n=8 for each allograft group).

Donor Antigen-Specific Immune Tolerance in the Absence of MyD88

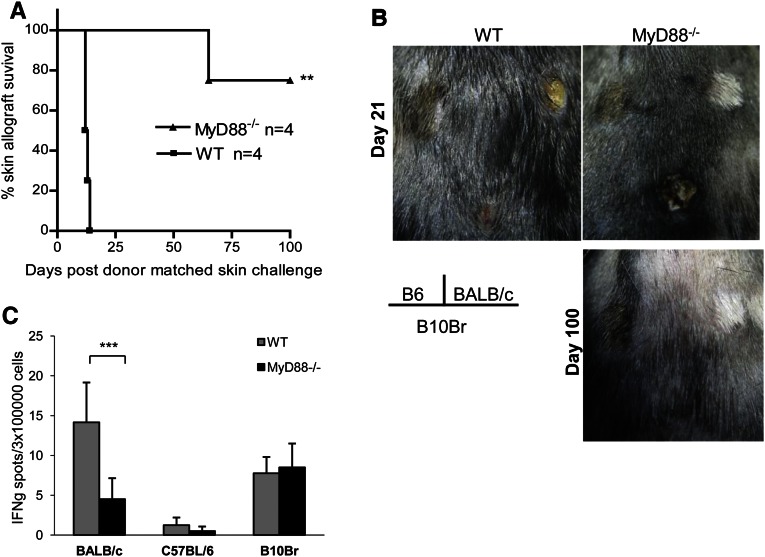

To test for immune tolerance, a subset of both WT and MyD88−/− kidney allograft acceptors received skin grafts from BALB/c (donor-matched allograft), C57BL/6 (isograft), and B10Br (third-party allograft) mice at day 150 after kidney transplant. WT mice rejected skin allografts from both donor-matched BALB/c and third-party B10Br mice at 12–14 days (Figure 5, A and B). MyD88−/− recipients accepted donor-matched skin allografts for over 75 days after skin transplant but rejected B10Br third-party allografts by day 15 (Figure 5, A and B). Skin isografts on WT and MyD88−/− kidney allograft recipients remained intact. Placement of skin grafts disrupted kidney graft acceptance in WT recipients; all of the recipients died between 34 and 107 days after skin allograft challenge, whereas MyD88−/− recipients retained normal kidney function, which was evidenced by normal serum creatinine (13.3±3.1 µmol/L) when euthanized at day 180 after skin grafting. Consistent with donor antigen-specific tolerance, MyD88−/− splenocytes harvested from an MyD88−/−allograft acceptor at day 100 after kidney transplantation stimulated with donor-matched allogeneic spleen cells produced significantly less IFN-γ than similarly stimulated WT splenocytes from a WT allograft acceptor as assessed by ELISPOT (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Donor antigen-specific immune tolerance in the absence of MyD88. WT and MyD88−/− kidney allograft acceptors received skin grafts from BALB/c (donor-matched allograft), C57BL/6 (isograft), and B10Br (H-2k; third-party allograft) mice at day 150 after kidney transplant. (A) Skin graft survival curves for donor-matched BALB/c skin challenges in WT and MyD88−/− acceptors. (B) WT acceptors rejected skin allografts from both donor-matched BALB/c and third-party B10Br mice. In contrast, MyD88−/− recipients accepted donor-matched skin allografts for over 100 days after skin transplant but rejected B10Br third-party allografts. Skin isografts on WT and MyD88−/− kidney allograft recipients remained intact. (C) MyD88−/− splenocytes from an MyD88−/− kidney allograft acceptor at day 100 post-transplant stimulated with donor-matched allogeneic spleen cells produced significantly less IFN-γ than similarly stimulated WT splenocytes from a WT allograft acceptor (***P<0.001). Data are mean ± SD (n=4 for each group).

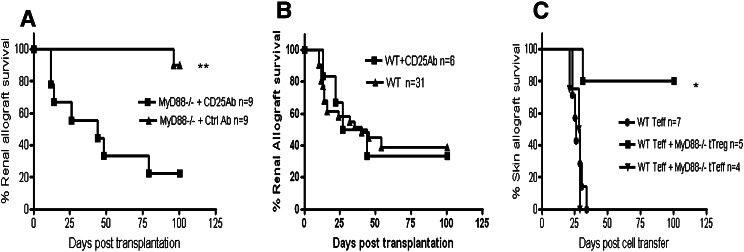

Allograft Tolerance in the Absence of MyD88 Signaling Is Dependent on a CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Regulatory Mechanism

We hypothesized that long-term allograft tolerance in the absence of MyD88 signaling may be dependent on immune regulation mediated by CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells (Tregs). To test this hypothesis, we treated MyD88−/− mice with an anti-CD25 mAb. This depleted CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ cells by >90% and abrogated graft acceptance (Figure 6A). Administration of anti-CD25 mAb to WT allograft recipients did not alter rejection kinetics (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Allograft tolerance in the absence of MyD88 signaling was dependent on a CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory mechanism. (A) Administration of anti-CD25 Ab to deplete CD4+CD25+ Tregs abrogated graft acceptance in MyD88−/− recipients (**P<0.01). (B) Administration of anti-CD25 Ab did not alter allograft rejection kinetics in WT recipients. (C) Transferable tolerance. CD4+CD25+ Tregs isolated from long-term C57BL/6.MyD88−/− acceptors were adoptively cotransferred with WT CD4+CD25− T effectors into C57BL/6.RAG−/− recipients that were previously transplanted with a BALB/c skin graft; skin grafts remained intact, whereas transfer of WT Teffs either alone or with Teffs from long-term MyD88−/− acceptors caused graft loss (*P<0.05).

We next sought to determine whether tolerance was transferrable. CD4+CD25+ Tregs were isolated and purified from long-term C57BL/6.MyD88−/− acceptors and adoptively cotransferred with WT CD4+CD25− T effectors (Teffs) into C57BL/6.RAG−/− recipients that were previously transplanted with a BALB/c skin graft. Skin grafts showed long-term survival in four of five mice compared with 100% graft loss from mice that received either WT CD4+CD25− Teffs alone or with C57BL/6.MyD88−/− CD4+CD25− Teffs (Figure 6C).

Increased Ratio of Tregs/Th17 Teffs Cells in MyD88−/− Allografts

There was a significant increase in CD4+FoxP3+ cells as a percentage of total CD4+ splenocytes obtained from WT allograft recipients, and to a greater extent, there was a significant increase in MyD88−/−allograft recipients compared with isograft recipients at day 14 post-transplant (Figure 7A). There was no significant difference in the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes producing either IL-17 or IFN-γ obtained from WT or MyD88−/− allograft recipients (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 7.

An increased ratio of T regulatory/Th17 effector cells in MyD88−/− allografts. (A) CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells were significantly increased in MyD88−/− spleen (n=6 for WT isograft, n=3 for MyD88−/− isograft, and n=10 for each allograft group) and MyD88−/− allografts (n=5) compared with WT allografts (n=4) by flow cytometry analysis (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). (B) IL-17 and IFN-γ production by T cells isolated from allografts at day 14 after kidney transplant. The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells producing IL-17 obtained from WT allografts (n=5) were significantly higher than percentages from MyD88−/− allografts (n=4; **P<0.01). (C) The percentage of T cells producing IFN-γ was similar in WT and MyD88−/− allografts (n=8 each). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

We isolated CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes from kidney grafts at day 14. CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs were significantly increased in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts (Figure 7A). The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells producing IL-17 obtained from WT allografts were significantly higher than the percentages from MyD88−/− allografts (Figure 7B), whereas the percentage of T cells producing IFN-γ was similar in both (Figure 7C).

To confirm the role of Th17 in kidney allograft rejection in our model, we transplanted BALB/c.IL17−/− (H2-Kd) kidneys into C57BL/6.IL17−/− recipients (H2-Kb) as IL17−/− allografts. IL17−/− allografts displayed prolonged survival compared with WT allografts (P<0.05; data not shown).

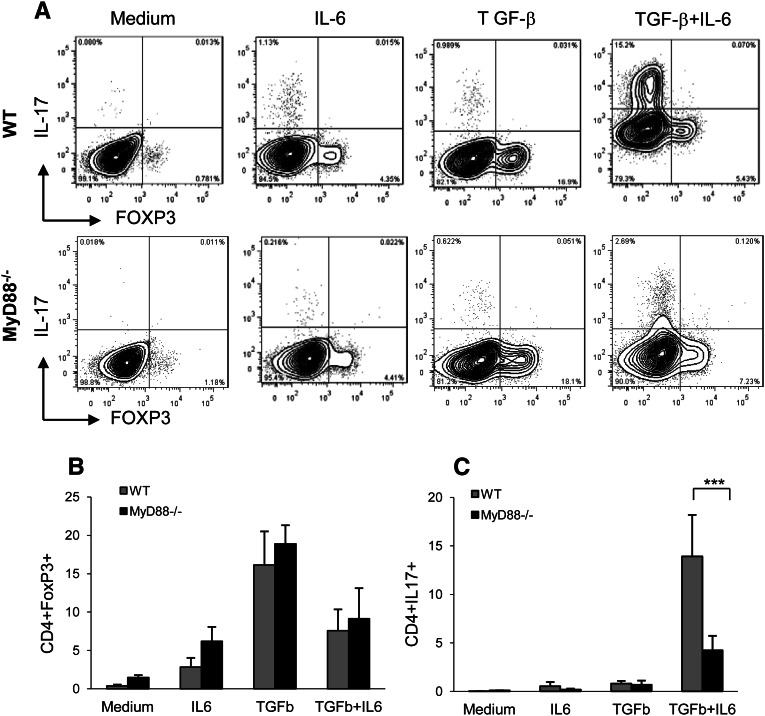

Absence of MyD88 Impairs Alloreactive Th17 Development, Resulting in an Increased Ratio of Tregs/Th17 Teffs Cells in Mixed Lymphocyte Cultures

We examined whether the absence of MyD88 would produce less IL-6 and consequently, an increased ratio of Treg/Th17 cells in an alloreactive mixed lymphocyte culture under conditions promoting either iTreg or Th17 differentiation.

CD4+ T cells obtained from naïve C57BL/6.WT or C57BL/6.MyD88−/− mice, stimulated with BALB/c.WT or BALB/c.MyD88−/− allogenic splenocytes in the absence of exogenous TGF-β and IL-6, did not result in the induction of either Foxp3+ Tregs or IL-17 Teffs (Figure 8A). The addition of TGF-β to WT and MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells in culture resulted in the generation of Foxp3+ Tregs but not Th17 cells, whereas the addition of IL-6 in the presence of TGF-β to WT CD4+ T cells promoted Th17 differentiation (Figure 8, B and C). C57BL/6.MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells stimulated with BALB/c.MyD88−/− allogenic splenocytes in the presence of exogenous TGF-β generated a comparable number of FoxP3+ Tregs compared with WT (Figure 8B), whereas MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6 generated significantly smaller numbers of IL-17–producing T cells compared with WT (Figure 8C). These results suggest that absence of MyD88 impairs alloreactive Th17 differentiation, resulting in an increased ratio of Tregs/Th17 Teffs in the alloreactive culture system in vitro.

Figure 8.

Absence of MyD88 signaling-impaired alloreactive Th17 development results in an increased ratio of T regulatory/Th17 effector cells in mixed lymphocyte cultures. (A) A representative flow cytometry analysis for reciprocal expression of FoxP3+ and IL-17+ in CD4+ T cells. (B) CD4+ T cells obtained from naïve C57BL/6.WT or C57BL/6.MyD88−/− mice, stimulated with BALB/c.WT or BALB/c.MyD88−/− allogeneic splenocytes in the absence of exogenous TGF-β and IL-6, did not result in the induction of either Foxp3+ Tregs or IL-17 T effectors. Addition of TGF-β to WT and MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells in culture generated a comparable number of Foxp3+ Tregs. (C) Addition of IL-6 in the presence of TGF-β to WT CD4+ T cells during differentiation increased the yield of Th17 cells, whereas MyD88−/− CD4+ T cells under the same conditions differentiated into significantly fewer numbers of IL-17–producing T cells compared with WT CD4+ T cells (***P<0.001). Combined data from four independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD (n=5–9 each).

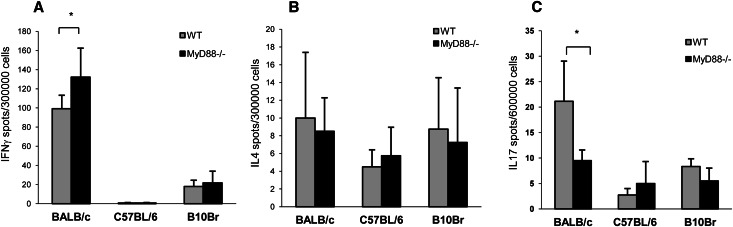

MyD88−/− Mice Exhibit Fewer Donor-Specific Th17 Immune Responders as Assessed by ELISPOT

To investigate whether MyD88−/−-tolerant mice generated fewer donor-specific Th17 cells, we measured T cell production of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 in response to allostimulation by ELISPOT assay. WT and MyD88−/− splenocytes, primed and stimulated with allogeneic cells, produced higher numbers of donor-reactive IFN-γ spots than splenocytes similarly stimulated with syngenic or third-party (B10Br) cells (Figure 9A). IL-4 production was not different between WT and MyD88−/− spleen cells (Figure 9B). The number of IL-17–producing cells was significantly greater in WT compared with MyD88−/− splenocytes after donor allostimulation (Figure 9C), with no significant difference after stimulation by either isogenic or third-party control cells.

Figure 9.

MyD88−/− recipients generated a diminished donor-specific Th17 immune response as assessed by ELISPOT. (A) MyD88−/− splenocytes primed and stimulated with allogeneic cells produced more donor-reactive IFN-γ–producing cells than similarly stimulated WT controls (*P<0.05). (B) IL-4 production was not different in allostimulated WT compared with MyD88−/− spleen cells. (C) MyD88−/− splenocytes primed and stimulated with allogeneic cells produced significantly less IL-17 than similarly stimulated WT splenocytes (*P<0.05). Representative data from two independent experiments are presented (mean ± SD, n=4 or n=8 each).

Discussion

IRI is an inevitable consequence of kidney implantation, and it leads to rapid activation of an innate immune response causing kidney injury. In the present study, we found that expression of both TLR2 and -4 and their endogenous ligands, including HMGB1, hyaluronan, and biglycan, was similarly increased in kidney grafts after transplantation (Supplemental Figure 4). These results, taken together with observational studies showing TLR4 and ligand upregulation within hours of human transplantation,16 suggest that TLR activation is a mediator of the innate immune response within the newly transplanted kidney.

Modulation of the graft microenvironment by this early innate response may be a prerequisite for the full development of adaptive alloimmunity and subsequent allograft rejection. In an allosensitized mouse model, allografts were acutely rejected in the presence of inflammation caused by ischemia reperfusion but not in its absence.6 In humans, observational studies have shown improved outcomes of lung and kidney allografts in patients with hypofunctioning TLR4 polymorphisms.17–19 Experimental work has shown that, although the absence of MyD88 signaling was sufficient to prevent minor MHC mismatched skin graft rejection,20 survival of fully mismatched allogeneic skin and heart transplants was not prolonged.21 A recent study reported that recipient MyD88 contributes to chronic graft dysfunction.22

Against this background, the importance of MyD88 signaling in the development of kidney allograft rejection was not fully understood. The current study found that mice genetically deficient in MyD88 developed donor-specific tolerance across a full MHC mismatch that was robust, which was shown by acceptance of donor-matched skin but rejection of third-party grafts. Our observations that CD25 depletion was sufficient to break tolerance and that tolerance was associated with impaired Th17 responses to alloantigen provide new evidence highlighting the extent to which adaptive alloimmunity may be controlled by the innate immune system.

TLRs can trigger activation of several arms of the adaptive immune response, generating effectors including Ig, Th1 and Th17 CD4+ effector T cells, and CD8+ effector T cells. The MyD88 pathway is known to be important in generating Th1 responses.12 Studies in allotransplant models seem partially consistent with this data. Gene expression of IFN-γ but not IL-4 was diminished in draining lymph nodes retrieved from MyD88−/− skin allograft recipients compared with WT recipients.20 In the present study, we found that IFN-γ mRNA expression was significantly reduced in MyD88−/− allografts compared with WT allografts. However, IL-4 mRNA expression was comparable, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from WT and MyD88−/− kidney allografts at day 14 post-transplant contained comparable numbers of IFN-γ–producing T cells. Consistent with this result, recent experimental data in transplantation has provided evidence that MyD88 signaling is not critical for allogeneic dendritic cells (DCs) or APCs to activate alloprimed T cells,21 although MyD88 deficiency led to a reduction in allogeneic T cell priming and consequent Th1 immunity in a skin transplant model.21

Although IFN-γ is an essential component of Th1-driven immune responses, it is also a critical cytokine in tolerance. IFN-γ has been shown to act as a protective factor against the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,23 and IFN-γ is specifically required for the induction of tolerance to alloantigens in several transplantation models.24–27 IFN-γ seems to be required for the generation and function of allospecific Tregs during the development of operational tolerance to donor alloantigens in vivo.28 IFN-γ conditioning ex vivo generates CD25+CD62L+FoxP3+ Tregs that prevent allograft rejection29 and shapes the alloreactive T cell repertoire by inhibiting Th17 responses and generating functional FoxP3+ Tregs.30

Activation of TLRs may regulate the development of Th17 cells. TLR signaling through MyD88 leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, a potent Th17 differentiation cytokine. Naïve T cells in the presence of IL-6 combined with TGF-β differentiate into Th17. Th17 cells are important for the clearance of pathogens but have also been found to have pathogenic roles in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.31–35 Evidence has emerged that Th17 cells are active in the process of IRI and allograft rejection. IL-17A−/− and IL-17R−/− mice were found to be protected from kidney IRI36 and elevation of IL-17 mRNA, and protein has been identified in the early stages of rat and human kidney allograft rejection, suggesting a role for Th17 cells, particularly in the initiation of rejection.37–39 It has been shown, using mice deficient in the Th1-specific transcription factor T-bet, that Th17 cells can mediate cardiac allograft rejection40 and are responsible for costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection.41,42 In the current study, we found that WT allografts expressed significantly higher amounts of IL-6 and TGF-β than MyD88−/− allografts, and IL-17 mRNA was significantly increased in WT allografts (Supplemental Figure 5). CD4+ and CD8+ cells isolated from WT allografts contained higher percentages of IL-17–producing cells than those cells from MyD88−/− allografts. WT splenocytes primed and stimulated with donor-matched allogeneic cells produced significantly higher numbers of IL-17–producing cells than similarly stimulated MyD88−/− splenocytes. Finally, we confirmed that IL17−/− mice displayed prolonged kidney allograft survival, suggesting that Th17 cells contribute to rejection in our model.

Th17 cells share a complex relationship with Tregs and may modulate Treg-induced transplant tolerance. Naïve T cells in the presence of TGF-β may differentiate into either Th17 or induced Tregs, with Th17 development promoted and induced Treg generation blocked by the concomitant presence of IL-6.43–45 IL-6, produced in response to TLR engagement by agonists, rendered activated T cells refractory to the suppressive activity of Tregs,46 and nTregs, in the presence of IL-6, can themselves differentiate into Th17 cells.47 In transplantation, the activation of innate immunity through TLR signaling triggered by IRI leads to an inflammatory milieu characterized by increased production of key cytokines, including IL-6. The resultant increase in IL-6 may lead to induction of Th17 cells but also inhibition of Tregs, promoting graft rejection over tolerance. Administration of the exogenous TLR9 ligand CpG at the time of transplant abrogated costimulation blockade-induced cardiac allograft acceptance in WT mice by the induction of IFN-γ and IL-17 production by intragraft CD4+ T cells and the prevention of induced Treg development.48 Consistent with this concept, our data show that IL-6 expression was reduced in MyD88−/− versus WT allografts. We also found a significantly higher number of CD4+ and CD8+ IL-17–producing T cells in rejecting WT allografts versus tolerant MyD88−/− allografts, whereas CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs were significantly increased in tolerant MyD88−/− spleen and allografts compared with rejecting WT counterparts. Our results suggest that absence of MyD88 impairs Th17 development, resulting in an increased ratio of Tregs over Th17. A recent study showed that absence of TLR/MyD88 signaling in DCs impairs Th17 cell development in response to phagocytosis of infected apoptotic cells, and instead, it supports Treg development.49 Indeed, our in vitro data also showed that absence of MyD88 impairs Th17 development and results in an increased ratio of Tregs/Th17effs in an alloreactive culture in vitro.

TLR activation may prevent experimental transplantation tolerance. Peritransplant infection triggers TLR signaling, which abrogates transplantation tolerance induced by costimulatory blockade. Administration of TLR agonists abrogated costimulation blockade-induced prolongation of skin allograft survival50–52 and prevented cardiac allograft acceptance, which was associated with impaired intragraft recruitment and function of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells.50,52 Conversely, impaired innate responses in MyD88-deficient recipients promoted costimulation blockade-induced allograft acceptance by the impairment of DC production of IL-6, reduced T cell activation, and enhanced T cell suppression mediated by CD4+CD25+ Tregs.53 We found a high frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ cells within spleens and kidney allografts of tolerant MyD88−/− recipients, whereas depletion of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells in tolerant MyD88−/− recipients broke tolerance. We were also able to transfer graft acceptance by CD4+CD25+ Tregs. Collectively, our data identify CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs as critical mediators of tolerance development and maintenance in MyD88−/− recipients in this model.

One limitation of our data is the lack of specificity of MyD88 for the TLRs, because both IL-1 and -18 can also signal through MyD88. Studies using caspase-1–deficient recipients that cannot activate MyD88 through IL-1 and -18 have shown that TLR–MyD88 signaling is critical for the rejection of minor mismatched skin allografts20 and costimulation blockade-induced skin allograft acceptance.53 We previously showed that IL-18 does not impact on the development of kidney allograft rejection in our model.54 Thus, we believe that TLR-mediated activation of the MyD88 pathway is critical in our model, and the findings are unlikely to be attributable to either IL-1 or -18.

In conclusion, our study has showed that, in the absence of MyD88, mice developed donor-specific kidney allograft tolerance, which was associated with impairment of Th17 and Th1 effectors, resulting in an increased ratio of Tregs over Th17 cells. Our data imply that inhibiting innate immunity may be a potential clinically relevant strategy to facilitate transplantation tolerance.

Concise Methods

Animals

Male WT:BALB/c (H2-Kd) donor, C57BL/6 (H2-Kb) recipient, and C57BL/6.RAG−/− mice were obtained from the Animal Resource Center, Perth, Australia. MyD88−/− on BALB/c or C57BL/6 backgrounds (designated as BALB/c.MyD88−/− and B6.MyD88−/− mice) was provided by the Animal Service of The Australian National University with permission from Professor S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). The mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility within the University of Sydney. Male mice aged 10–14 weeks were used in all experiments. Experiments were conducted using established guidelines for animal care and approved by the animal ethics committee of the University of Sydney.

Experimental Design

Five groups of mice received a kidney transplant: (1) WT allografts (C57BL/6 mice that received a kidney from a BALB/c donor); (2) MyD88−/− allografts (C57BL/6.MyD88−/− mice that received a BALB/c.MyD88−/− donor kidney); (3) isografts (C57BL/6 recipients of a C57BL/6 kidney); (4) donor MyD88−/− allografts (C57Bl/6 WT mice that received a kidney from a BALB/c.MyD88−/− donor); and (5) recipient MyD88−/− allografts (C57BL/6.MyD88−/− mice that received a kidney from a BALB/c WT donor).

Survival Experiment

To determine the importance of MyD88 signaling in allograft rejection, MyD88−/− allografts (n=17), donor MyD88−/− allografts (n=7), and recipient MyD88−/− allografts (n=5) were compared with WT allografts (n=31) and isografts (n=6). For those recipients surviving to day 150, a proportion of MyD88−/− allografts (n=4) and WT allografts (n=4) received full-thickness skin grafts from three sources: BALB/c (kidney donor-matched skin allograft), C57BL/6 (syngeneic), and B10Br (third-party allografts). Grafts were observed regularly for signs of rejection to at least day 100.

Time Course Study

To examine intragraft events and mechanisms, groups of WT allografts and MyD88−/− allografts were killed early (day 14) and late (day 100) to compare differences in acute and chronic rejection, respectively.

Mouse Kidney Transplantation

Orthotopic kidney transplants were performed on the animals as previously described. Briefly, the left kidney of the donor animal was flushed with heparinized saline and removed together with ureter and vessels en mass, including a small (1–2 mm) bladder cuff attached to the distal ureter. The recipient animal underwent a left-sided nephrectomy, and the transplanted kidney was placed orthotopically on day 0. Urinary tract reconstruction was established by either inserting the ureter into the bladder (day 14 experiment only) or suturing the bladder patch to a cystostomy located on the bladder dome55 (a bladder-to-bladder anastomosis) for survival study and day 100 experiments. All transplanted mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of ampicillin at the time of transplant surgery. No immunosuppressive therapy was administered. The recipient’s right native kidney was removed at days 3–7, necessitating the graft to be life-sustaining. Animals with technical graft failure or wound infection became overtly ill (and were euthanized) or died within 4 days of the contralateral nephrectomy and were removed from the study.

Skin Transplantation

Full-thickness tail skin grafts were placed on graft beds prepared on recipients at day 150 after kidney allograft transplantation. Grafts were covered with protective bandages for 7 days. Rejection was defined as graft necrosis of the entire graft area. Recipients that accepted their allograft showed preserved graft size and hair growth.

Blood and Tissue Samples

Blood and kidney tissues were harvested at time of euthanasia. Tissue slices were fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin for paraffin embedding, frozen in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek Inc., Torrance, CA), or snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent mRNA extraction.

Assessment of Kidney Function

Serum creatinine was measured using the modified Jaffe rate reaction by the Biochemistry Department of The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

Histology

All histologic analysis was performed in a blinded manner. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining was performed on 3 μm paraffin kidney sections to assess tubulitis, glomerulosclerosis, and interstitial fibrosis.

Tubulitis was examined on 250 tubular cross-sections per animal. Each tubular cross-section was assessed as (1) normal, (2) mild tubulitis (defined as two or three infiltrating mononuclear cells per tubular cross-section and disruption of the basement membrane), or (3) severe tubulitis (defined as greater than or equal to four infiltrating mononuclear cells per tubular cross-section). A score for the degree of tubulitis was calculated for each animal as per a modified method described previously, where each normal tubule was assigned a value of one and the number of tubules affected with mild and severe tubulitis was multiplied by two or three, respectively. The total tubulitis score for each animal was the sum of these figures.

Glomerulosclerosis was quantitated by the presence of PAS-positive staining material involving >30% of each glomerulus as described previously.56 All glomeruli per section were scored to determine the percentage of glomeruli displaying glomerulosclerosis.

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy were graded using the Banff 97 scoring criteria on a scale of one to three: 1, mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (<25% of cortical area); 2, moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (26%–50% of cortical area); 3, severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy/loss (>50% of cortical area). If changes were minimal but not absent, the score of 0.5 was applied. Using an ocular grid, the score of each sample was counted at least in 15–25 consecutive fields across a full section (×200 magnification) and averaged for each graft.

Picro-Sirius red (PSR) staining was performed on 5-μm paraffin sections. Interstitial PSR staining area for collagen was assessed by point counting using an ocular grid as described in the work by McWhinnie et al.57 in at least 12 consecutive fields (×200 magnification). Only interstitial collagen was counted, and vessels and glomeruli were excluded. The result was expressed as the percentage of positive staining area per field.

Immunohistochemisty Staining

Acetone-fixed frozen sections (7 µm) were exposed to 0.06% H2O2 in PBS, blocked with a biotin blocker system (DAKO Corporation), and then blocked in 10% normal horse serum. Primary antibody, rat anti-mouse CD68 antibody (ABD Serotec), CD4 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), CD8 (BD Biosciences), and hamster anti-mouse CD11c (BD Biosciences) were applied to the sections for 60 minutes. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections of 5 µm thickness were deparaffinized and boiled for 15 minutes in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for α-SMA (Abcam, MA), HMGB1 (Abcam, MA), and hyaluronan detection. Sections were blocked in 20% normal goat serum and incubated with rabbit anti–α-SMA or anti-HMGB1 for 1 hour. Endogenous peroxidase activity was then quenched in 3% H2O2 in methanol. Concentration-matched Ig was used as an isotype negative control. Sections were incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody: anti-rat IgG, anti-hamster IgG, or anti-rabbit Ig (BD Biosciences). Instead of a primary antibody, a biotinylated hyaluronan-binding protein (Seikagaku Corp. Japan) at 5 μg/ml was used for hyaluronan staining. Vector stain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories Inc.) was applied to the tissue and followed by 3,3′diaminobenzidine substrate-chromogen solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). The slides were counterstained with Harris’ hematoxylin.

Quantification of Immunohistochemistry

Analysis of the cellular infiltrates for CD4 and CD8 was performed in a blinded manner by assessing 20 consecutive high-power fields (HPFs; ×400 magnification) of the cortex in each section. Using an ocular grid, the number of cells staining positively for each antibody was counted and expressed as cells per HPF. Analysis of CD68+ and CD11c+ infiltrates was performed using a digital image analysis program (Automated Cellular Imaging System ACIS III; Dako, Aliso Viejo, CA). An area of cortex was analyzed for interstitial cellular-positive staining versus counter-stained area. The results were expressed as percentage of positive staining. Analysis of α-SMA staining was assessed by point counting using an ocular grid as described above. Staining around the vessels was not included. The result was expressed as the percentage of positive staining area per HPF.

Immunofluorescence

For C4d immunofluorescent staining, frozen sections were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 20 minutes and incubated with rat anti-mouse antibodies to C4d (Abcam plc, Cambridge, MA) for 60 minutes followed by anti-rat IgG conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Staining for C4d was considered positive when the peritubular capillaries were diffusely (all HPFs) and brightly stained. Scoring of C4d staining was based on the percentage of stained tissue on immunofluorescence that had a linear, circumferential staining pattern in PTCs following the Banff 07 scoring criteria on a scale of zero to three: 0, negative (0%); 1, minimal C4d stain/detection (1<10%); 2, focal C4d stain/positive (10%–50%); 3, diffuse C4d stain/positive (>50%).

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from kidney tissue and cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using oligo d(T)16 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the SuperScript III Reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen).

Real-Time PCR

Specific Taqman primers and probes for TLR2, TLR4, HMGB1, biglycan, HAS1, HAS2, hsp60, hsp70, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IFN-γ, CCL2, CXCL10, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were previously described.9,54,58 Specific Taqman primers and probes for GranzymeB (Mm00442834_m1), Perforin1 (Mm00812512_m1), TGF-β1 (Mm01178820_m1), IL-17 (Mm00439619_m1), CXCL9 (Mm01345157_m1), MMP2 (Mm00439506_m1), and TIMP1 (Mm01341361_m1) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). cDNA was amplified in 1× Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with gene-specific primers and probes in the Rotor-Gene 6000 system (Corbett Life Science). Data were analyzed using Rotor-Gene 6000 Analysis Software (Corbett Life Science). All results are expressed as ratio to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cell Isolation from Allografts

Cell suspensions from the kidney grafts were isolated as previously described.56 Kidney cortex was minced and underwent digestion with collagenase and deoxyribonuclease (Sigma-Aldrich); then, they passed through a 250-μm sieve. Cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 40% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI-1640 medium, and overlayed on a 66.7% Percoll solution. Gradient separation was carried out at 2100 rpm for 20 minutes at room temperature. Spleen and blood cells were also isolated from mice using standard methods.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Donor-specific alloantibody titers were measured by flow cytometry. Dilutions (1/10 and 1/20) of mouse serum from transplanted mice were incubated with BALB/c (donor) splenocytes for 1 hour at 4°C. After washing three times, the donor cells were incubated with either rat FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a (BD Biosciences). The median fluorescence intensity of the stained samples was determined by flow cytometry. All analyses were performed on a FACS CALIBUR flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with Cellquest Pro software (BD Biosciences). Results were read as median fluorescent intensity.

FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4–5), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-mouse CD8 (clone 53–6.7), APC-Cy7–conjugated anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11), and isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences. APC-conjugated anti-mouse IL-17A (clone TC11–18H10) was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and PE-conjugated anti-mouse FoxP3 (clone FJK-16s) was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). IFN-γ and IL-17A intracytoplasmic stainings were performed after cell incubation with 10 μg/ml PMA and 500 ng/ml ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) for 4 hours; then, the cells were stained for surface markers for 40 minutes, washed, fixed with CytoFix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences), permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences), and labeled with anticytokine antibodies. FoxP3 staining was performed after cell surface marker labeling using eBioscience fixation/permeabilization and permeabilization buffers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytometry analysis was performed on a Canto cytometer using FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with FLOWJO software (Tree Star, Inc).

CD25+ Cell Depletion

To deplete CD4+CD25+ cells in vivo, mice received rat anti-mouse CD25 mAb (clone PC-61, rat IgG1; BioXcell, NH) or isotype rat IgG (0.5 mg/mouse) intraperitoneally on days −2, 0, and 2 and 2 weeks post-transplantation (n=9). CD25+ cell depletion was confirmed between days 14 and 21 after kidney transplantation by staining blood white cells with anti-CD25 (clone 7D4 or 3C7; BD Biosciences, Pharmingen, CA).

CD4+ T Cell Enrichment and Cell Sorting

To purify CD4+CD25+ (Tregs) and CD4+CD25− (Teffs), spleen cells were enriched for CD4+ T cells using a mouse CD4+ T cell enrichment kit (EasySep; StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The enriched CD4+ T cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 and APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD25 (clone PC-61; BD Biosciences), and then, they were sorted for CD4+CD25+ or CD4+CD25− cells (>95% purity) by FACS.

Adoptive Transfer

C57BL/6.RAG−/− mice received full-thickness BALB/c skin grafts 2 weeks before receiving adoptive transfers through tail vein injection of either 2 × 105 CD4+CD25+ (Tregs) or CD4+CD25− (Teffs) harvested from C57BL/6.MyD88−/− recipients that had accepted their BALB/c.MyD88−/− kidney allografts for >200 days; 1 × 105 CD4+CD25− T effectors harvested from naïve WT C57BL/6 mice were coinfused.

In Vitro T Cell Differentiation

CD4+ T cells from the spleens of WT and MyD88−/− mice on C57BL/6 backgrounds were purified using anti-CD4 beads (Miltenyi) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified CD4+ T cells were stimulated with allogeneic, irradiated splenocytes from BALB/c or BALB/c.MyD88−/− mice in a 48-well plate under iTreg differentiation conditions (TGF-β; 10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of IL-6 (20 ng/ml) in complete RPMI-10 medium for 5 days. Cells were supplemented with recombinant IL-2 (50 U/ml) at 24 and 72 hours.

ELISPOT Analysis of Donor-Specific IFNγ, IL4, and IL17 Production

ELISpotPLUS kits for IFNγ, IL4, and IL17 (Mabtech AB, Stockholm, Sweden) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described.54 Responder splenocytes were isolated from mice (C57BL/6 WT and C57BL/6 MyD88−/−) primed 14 days prior with 1.5 × 107 BALB/c splenocytes administered by tail vein injection or from WT and MyD88−/− kidney allograft acceptors at 100 days after kidney transplant. Stimulator splenocytes from naïve BALB/c, C57BL/6, or B10.BR mice were isolated and irradiated. Responder and irradiated stimulator splenocytes were each added at 3 × 105 cells/well to a final volume 100 μl and incubated for 24 hours with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The plates were washed, and the appropriate biotinylated detection antibody (Mabtech) (diluted to 1 μg/ml in PBS containing 1.5% FCS) was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washings, streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (1:1000) was added for 60 minutes at room temperature. The wells were washed and then developed with filtered substrate solution BCIP/NBT-plus (Mabtech) until distinct spots emerged. Concanavalin A was added to some wells with responder cells only as a positive, technical control; negative control wells with stimulator only and medium only were also performed on each plate. All combinations were performed at least in triplicate. Spots were counted using an automated AID ELISPOT reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strasberg, Germany).

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between graft survival times were calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival curves with the log-rank test. Statistical differences between the two groups were analyzed by unpaired two-tailed t tests, and multiple groups were compared using one- or two-way ANOVA with posthoc Bonferroni correction (Graph Pad Prism 4.0 software). P values<0.05 were considered significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the expertise of Dr. Brian Howden, who performed the transplant surgeries, and thank Ms. T. Corpuz and Dr. Vacher-Coponat for their technique assistance.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grants 512489 and 1029601.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012010052/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McDonald S, Russ G, Campbell S, Chadban S: Kidney transplant rejection in Australia and New Zealand: Relationships between rejection and graft outcome. Am J Transplant 7: 1201–1208, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier-Kriesche HU, Steffen BJ, Chu AH, Loveland JJ, Gordon RD, Morris JA, Kaplan B: Sirolimus with neoral versus mycophenolate mofetil with neoral is associated with decreased renal allograft survival. Am J Transplant 4: 2058–2066, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O’Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR: The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 349: 2326–2333, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, van Leeuwen MT, Stewart JH, Law M, Chapman JR, Webster AC, Kaldor JM, Grulich AE: Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA 296: 2823–2831, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briganti EM, Russ GR, McNeil JJ, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ: Risk of renal allograft loss from recurrent glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 347: 103–109, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalasani G, Li Q, Konieczny BT, Smith-Diggs L, Wrobel B, Dai Z, Perkins DL, Baddoura FK, Lakkis FG: The allograft defines the type of rejection (acute versus chronic) in the face of an established effector immune response. J Immunol 172: 7813–7820, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obhrai J, Goldstein DR: The role of toll-like receptors in solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 81: 497–502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nankivell BJ, Alexander SI: Rejection of the kidney allograft. N Engl J Med 363: 1451–1462, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, Yin J, Bertolino P, Eris JM, Alexander SI, Sharland AF, Chadban SJ: TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 117: 2847–2859, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anders HJ, Banas B, Schlöndorff D: Signaling danger: Toll-like receptors and their potential roles in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 854–867, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, John R, Richardson JA, Shelton JM, Zhou XJ, Wang Y, Wu QQ, Hartono JR, Winterberg PD, Lu CY: Toll-like receptor 4 regulates early endothelial activation during ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 79: 288–299, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R: Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2: 947–950, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leemans JC, Stokman G, Claessen N, Rouschop KM, Teske GJ, Kirschning CJ, Akira S, van der Poll T, Weening JJ, Florquin S: Renal-associated TLR2 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. J Clin Invest 115: 2894–2903, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shigeoka AA, Holscher TD, King AJ, Hall FW, Kiosses WB, Tobias PS, Mackman N, McKay DB: TLR2 is constitutively expressed within the kidney and participates in ischemic renal injury through both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol 178: 6252–6258, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu H, Ma J, Wang P, Corpuz TM, Panchapakesan U, Wyburn KR, Chadban SJ: HMGB1 contributes to kidney ischemia reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1878–1890, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krüger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, Lerner SM, Ames S, Bromberg JS, Lin M, Walsh L, Vella J, Fischereder M, Krämer BK, Colvin RB, Heeger PS, Murphy BT, Schröppel B: Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 3390–3395, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Davis RD, Herczyk WF, Howell DN, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA: The role of innate immunity in acute allograft rejection after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 628–632, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Mir S, Smith SR, Kuo PC, Herczyk WF, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA: Donor polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor-4 influence the development of rejection after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant 20: 30–36, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ducloux D, Deschamps M, Yannaraki M, Ferrand C, Bamoulid J, Saas P, Kazory A, Chalopin JM, Tiberghien P: Relevance of Toll-like receptor-4 polymorphisms in renal transplantation. Kidney Int 67: 2454–2461, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein DR, Tesar BM, Akira S, Lakkis FG: Critical role of the Toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein MyD88 in acute allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 111: 1571–1578, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesar BM, Zhang J, Li Q, Goldstein DR: TH1 immune responses to fully MHC mismatched allografts are diminished in the absence of MyD88, a toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein. Am J Transplant 4: 1429–1439, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Schmaderer C, Kiss E, Schmidt C, Bonrouhi M, Porubsky S, Gretz N, Schaefer L, Kirschning CJ, Popovic ZV, Gröne HJ: Recipient Toll-like receptors contribute to chronic graft dysfunction by both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling. Dis Model Mech 3: 92–103, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu CQ, Wittmer S, Dalton DK: Failure to suppress the expansion of the activated CD4 T cell population in interferon gamma-deficient mice leads to exacerbation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 192: 123–128, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishimoto K, Sandner S, Imitola J, Sho M, Li Y, Langmuir PB, Rothstein DM, Strom TB, Turka LA, Sayegh MH: Th1 cytokines, programmed cell death, and alloreactive T cell clone size in transplant tolerance. J Clin Invest 109: 1471–1479, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konieczny BT, Dai Z, Elwood ET, Saleem S, Linsley PS, Baddoura FK, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Lakkis FG: IFN-gamma is critical for long-term allograft survival induced by blocking the CD28 and CD40 ligand T cell costimulation pathways. J Immunol 160: 2059–2064, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassan AT, Dai Z, Konieczny BT, Ring GH, Baddoura FK, Abou-Dahab LH, El-Sayed AA, Lakkis FG: Regulation of alloantigen-mediated T-cell proliferation by endogenous interferon-gamma: Implications for long-term allograft acceptance. Transplantation 68: 124–129, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markees TG, Phillips NE, Gordon EJ, Noelle RJ, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA: Long-term survival of skin allografts induced by donor splenocytes and anti-CD154 antibody in thymectomized mice requires CD4(+) T cells, interferon-gamma, and CTLA4. J Clin Invest 101: 2446–2455, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawitzki B, Kingsley CI, Oliveira V, Karim M, Herber M, Wood KJ: IFN-gamma production by alloantigen-reactive regulatory T cells is important for their regulatory function in vivo. J Exp Med 201: 1925–1935, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng G, Wood KJ, Bushell A: Interferon-gamma conditioning ex vivo generates CD25+CD62L+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells that prevent allograft rejection: Potential avenues for cellular therapy. Transplantation 86: 578–589, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng G, Gao W, Strom TB, Oukka M, Francis RS, Wood KJ, Bushell A: Exogenous IFN-gamma ex vivo shapes the alloreactive T-cell repertoire by inhibition of Th17 responses and generation of functional Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 38: 2512–2527, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y: Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol 171: 6173–6177, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang XO, Chang SH, Park H, Nurieva R, Shah B, Acero L, Wang YH, Schluns KS, Broaddus RR, Zhu Z, Dong C: Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. J Exp Med 205: 1063–1075, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzartos JS, Friese MA, Craner MJ, Palace J, Newcombe J, Esiri MM, Fugger L: Interleukin-17 production in central nervous system-infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol 172: 146–155, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gan PY, Steinmetz OM, Tan DS, O’Sullivan KM, Ooi JD, Iwakura Y, Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR: Th17 cells promote autoimmune anti-myeloperoxidase glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 925–931, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Li M, Kausman JY, Semple T, Edgtton KL, Borza DB, Braley H, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: Th1 and Th17 cells induce proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2518–2524, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Huang L, Vergis AL, Ye H, Bajwa A, Narayan V, Strieter RM, Rosin DL, Okusa MD: IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 120: 331–342, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loong CC, Hsieh HG, Lui WY, Chen A, Lin CY: Evidence for the early involvement of interleukin 17 in human and experimental renal allograft rejection. J Pathol 197: 322–332, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh HG, Loong CC, Lui WY, Chen A, Lin CY: IL-17 expression as a possible predictive parameter for subclinical renal allograft rejection. Transpl Int 14: 287–298, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinmetz OM, Summers SA, Gan PY, Semple T, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: The Th17-defining transcription factor RORγt promotes glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 472–483, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan X, Paez-Cortez J, Schmitt-Knosalla I, D’Addio F, Mfarrej B, Donnarumma M, Habicht A, Clarkson MR, Iacomini J, Glimcher LH, Sayegh MH, Ansari MJ: A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med 205: 3133–3144, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan X, Ansari MJ, D’Addio F, Paez-Cortez J, Schmitt I, Donnarumma M, Boenisch O, Zhao X, Popoola J, Clarkson MR, Yagita H, Akiba H, Freeman GJ, Iacomini J, Turka LA, Glimcher LH, Sayegh MH: Targeting Tim-1 to overcome resistance to transplantation tolerance mediated by CD8 T17 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 10734–10739, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burrell BE, Csencsits K, Lu G, Grabauskiene S, Bishop DK: CD8+ Th17 mediate costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection in T-bet-deficient mice. J Immunol 181: 3906–3914, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK: Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441: 235–238, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Afzali B, Lombardi G, Lechler RI, Lord GM: The role of T helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T cells (Treg) in human organ transplantation and autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Immunol 148: 32–46, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heidt S, Segundo DS, Chadha R, Wood KJ: The impact of Th17 cells on transplant rejection and the induction of tolerance. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 15: 456–461, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasare C, Medzhitov R: Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science 299: 1033–1036, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu L, Kitani A, Fuss I, Strober W: Cutting edge: Regulatory T cells induce CD4+CD25-Foxp3- T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta. J Immunol 178: 6725–6729, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Ahmed E, Wang T, Wang Y, Ochando J, Chong AS, Alegre ML: TLR signals promote IL-6/IL-17-dependent transplant rejection. J Immunol 182: 6217–6225, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM: Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature 458: 78–82, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen L, Wang T, Zhou P, Ma L, Yin D, Shen J, Molinero L, Nozaki T, Phillips T, Uematsu S, Akira S, Wang CR, Fairchild RL, Alegre ML, Chong A: TLR engagement prevents transplantation tolerance. Am J Transplant 6: 2282–2291, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thornley TB, Brehm MA, Markees TG, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Welsh RM, Rossini AA, Greiner DL: TLR agonists abrogate costimulation blockade-induced prolongation of skin allografts. J Immunol 176: 1561–1570, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porrett PM, Yuan X, LaRosa DF, Walsh PT, Yang J, Gao W, Li P, Zhang J, Ansari JM, Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Koulmanda M, Strom TB, Turka LA: Mechanisms underlying blockade of allograft acceptance by TLR ligands. J Immunol 181: 1692–1699, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker WE, Nasr IW, Camirand G, Tesar BM, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR: Absence of innate MyD88 signaling promotes inducible allograft acceptance. J Immunol 177: 5307–5316, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wyburn K, Wu H, Chen G, Yin J, Eris J, Chadban S: Interleukin-18 affects local cytokine expression but does not impact on the development of kidney allograft rejection. Am J Transplant 6: 2612–2621, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martins PN: Technique of kidney transplantation in mice with anti-reflux urinary reconstruction. Int Braz J Urol 32: 713–718, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu H, Wang YM, Wang Y, Hu M, Zhang GY, Knight JF, Harris DC, Alexander SI: Depletion of gammadelta T cells exacerbates murine adriamycin nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1180–1189, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McWhinnie DL, Thompson JF, Taylor HM, Chapman JR, Bolton EM, Carter NP, Wood RF, Morris PJ: Morphometric analysis of cellular infiltration assessed by monoclonal antibody labeling in sequential human renal allograft biopsies. Transplantation 42: 352–358, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu H, Craft ML, Wang P, Wyburn KR, Chen G, Ma J, Hambly B, Chadban SJ: IL-18 contributes to renal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2331–2341, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.