This prospective study aims to determine physician- and patient-perceived barriers to breast cancer clinical trial enrollment for older patients.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Clinical trials, Elderly

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Cite reasons given by patients older than 65 years for their decisions to participate or not to participate in clinical trials.

Cite reasons given by physicians for their decisions not to enroll patients older than 65 years in clinical trials or discuss enrollment with these patients.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Purpose.

Patients older than 65 years are underrepresented in clinical trials. We conducted a prospective study (SWOG S0316) to determine physician- and patient-perceived barriers to breast cancer clinical trial enrollment for older patients.

Methods.

Eight geographically diverse SWOG institutions participated. The study assessed patients' and physicians' decisions to enroll in or decline clinical treatment trials, including demographics, trial availability, and eligibility. Patient and physician questionnaires elicited concerns related to treatment, medical status, age, family, and financial or transportation concerns.

Results.

A total of 1,079 patients were registered and eligible and 909 (84%) returned for follow-up. The major reason for nonaccrual was either trial unavailability or ineligibility (60%). Older patients were less likely to be eligible for trials (65% for age ≥65 years vs. 78% for age <65 years). If eligible, trial participation rates did not differ significantly by age (34% for age ≥65 years vs. 40% for age <65 years). Patients ≥65 years more often were concerned about side effects, had friends opposed to participation, or believed that participation would not benefit other generations. When trials were available and patients were eligible, physicians discussed trial participation with 76% of patients <65 years versus 58% of patients ≥65 years of age. For patients ≥65 years, 11% of physicians indicated age as a reason they did not enroll a patient in a clinical trial.

Conclusion.

Trial unavailability or patient ineligibility were the major reasons for lack of enrollment in breast cancer clinical trials for patients of all ages in this prospective study. Older patients were less likely to be eligible for trials, but if eligible they participated at similar rates to younger patients.

Introduction

More than 60% of patients with cancer in the United States are 65 years of age or older [1, 2]. We lack clear treatment guidelines for this population, in part because of their underrepresentation in clinical trials [1, 2]. Federal agencies and cancer cooperative groups have mandated the recruitment of women and minorities to oncology clinical trials [3–7]. In contrast, enrollment of older patients has received little attention. By 2030, approximately 20% of the U.S. population is expected to be 65 years of age or older, with the resultant major increase in cancer burden in this group [8]. Adequate representation of older patients in cancer clinical trials is therefore paramount to developing effective treatment approaches for this population.

Hutchins et al. previously reported that patients ≥65 years of age represented only 25% of participants in SWOG trials even though this age group represented 63% of the U.S. population of patients with cancer [1]. This disparity was more pronounced in trials of breast cancer treatment. Although 49% of breast cancers occurred in patients ≥65 years of age, only 9% of all patients enrolled in SWOG breast cancer trials were ≥65 years of age. Underrepresentation of elderly patients in clinical trials may stem from medical comorbidities, trial eligibility criteria, or patient and/or physician misconceptions as to the risks of enrollment. Kemeny et al. showed that 34% of patients >65 years of age with stage II breast cancer were offered a clinical trial compared to 68% of younger patients [9].

Melisko et al. assessed the attitudes of patients of all ages about participation in breast cancer clinical trials between 1997 and 2000 [10]. Physicians not linked to these patients were also surveyed. The authors found that patients emphasized concerns regarding toxicity, extra time, and randomization, whereas physician-reported barriers were the extra time required for staff, extra costs, and randomization.

A review of existing studies of barriers to elderly participation in breast cancer clinical trials was conducted by Townsley et al. [11]. They reported that physician perceptions of potential toxicities and comorbidity-related questions about treatment tolerability represented the most important physician-driven barriers. Older breast cancer patients, however, did not view toxicity concerns as important but emphasized the lack of autonomy with randomization as a barrier to trial participation. Kemeny et al. also reported that both younger and older patients viewed the inability to choose their treatment as the most important reason for not enrolling in a clinical trial [9]. Because of the retrospective nature and small size of these prior studies, age-dependent variation in reasons for trial nonparticipation could not be assessed.

We designed a large prospective survey study to determine the patient and provider-driven factors responsible for the underrepresentation of older patients in cancer clinical trials. This article reports physician- and patient-perceived barriers to enrollment in SWOG breast cancer clinical trials, with particular focus on differential barriers between older (≥65 years) and younger patients.

Patients and Methods

SWOG protocol S0316 was a prospective survey study conducted between 2004 and 2008, which included breast, lung, and colorectal cancers. However, the lung and colorectal arms of the trial were closed early due to insufficient accrual and are not included in this report. Eight geographically diverse SWOG institutions (five academic and three community based) participated in S0316.

Enrollment Criteria

Patients with breast cancer were registered prior to systemic treatment decision-making. In order to be eligible for our study, patients had to be new to the institution or, if known to the institution, to have a new diagnosis or new stage presentation of breast cancer. Patients were also required to be 18 years of age or older, to be able to read and comprehend English, and to have a diagnosis of stage I–IV invasive cancer for which systemic chemotherapy would be considered. Stages I–IV were included to capture the largest and broadest patient population. The study design included both older and younger women. All surveyed patients were asked about their treatment trial participation (regardless of whether a treatment trial was offered or a patient participated in one). The study protocol and informed consent document were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the participating SWOG sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to S0316 study enrollment.

Data Collection

All patients at each site who met our survey study enrollment criteria above were offered S0316 participation. A Clinical Research Associate (CRA) form indicating the course of treatment decision-making was required for all patients within 6 months of registration to the study. Enrolled patients immediately completed a patient demographic questionnaire. Patients with a therapeutic clinical trial available for the patient's disease site and stage and who were eligible for the clinical trial completed either the Patient Participation questionnaire or the Patient Refusal questionnaire, depending on their treatment decision. A Physician Treatment questionnaire was completed by physicians within 2 months of a treatment decision for each case in which a patient was eligible for an available onsite trial but not enrolled in a clinical trial.

Study Questionnaires

At the time this study was developed, there was no validated measure for examining barriers to enrolling patients in clinical trials. Studies reported in the literature examined this question with single-item measures of the reasons patients gave for enrolling or not enrolling in a clinical trial and, similarly, the reasons physicians gave for offering trial participation to patients (particularly for patients ≥65 years of age) [10, 12–16]. We reviewed this literature and prepared two questionnaires for patients and one for physicians to complete.

Patient Questionnaires.

The Patient Participation questionnaire had 22 specific items and the Patient Refusal questionnaire had 23 specific items. For each, we report on the proportion of patients answering that the statement was true for them. Both the Patient Participation and Patient Refusal questionnaires were based primarily on items used in a study by Ellis et al. [12]. Additional factors included in the patient questionnaires were also adapted from other previously published studies [13–16]. These items were designed and reported as individual outcomes as opposed to aggregate total or subscale scores. Response options for the two patient questions involved first indicating if the factor or statement was true for the patient (false, true, not applicable); if true, patients indicated the level of importance for participating or not participating on a trial (very important, somewhat important, not important).

All items in each survey were reviewed by two participating medical oncologists (J.R.G., K.S.A.). In addition, a behavioral scientist at a participating institution, the nurse/data manager from that institution, and one to two patients at that institution reviewed the patient questionnaire items. Finally, a representative of SWOG's Lay Advocates Committee also reviewed the patient questionnaire items and provided comments.

Physician Questionnaire.

The Physician Treatment questionnaire had 21 specific items addressing why the physician did not discuss a trial with the patient when there was an available trial for this patient. If the physician did discuss a trial with an eligible patient but the patient did not enroll, there were 11 specific items and one other reason option addressing the physician's perception of why the patient did not enroll in the trial. Response options included the following: influenced my decision a great deal, influenced my decision some, did not influence my decision at all.

The physician was also asked to indicate whether they recommended the available trial as the physician's first choice for the patient's treatment or as one of many options for treatment. We did not ask the physician to answer questions when the patient agreed to participate in the clinical trial. Items for the Physician Questionnaire were based on previously published studies [11, 17–21]. Again, these items are reported as single items and not aggregated as subscale or total scale outcomes. The SWOG study investigators reviewed the Physician Questionnaire prior to its finalization.

Additional Questionnaires.

Patients completed a demographic questionnaire that included marital status, education level, travel distance to clinic, type of transportation used to get to the clinic, and household income. Site staff maintained a log of patients who did not participate in S0316 with reasons noted. Site staff also completed a form for each patient that indicated whether there were available clinical trial(s) for that patient and whether the patient agreed or did not agree to be treated in the trial.

Monthly conference calls of SWOG investigators were conducted to ensure consistency across sites for determination of trial eligibility and survey study enrollment.

Statistical Considerations

The primary goal of this study was to compare patient- and physician-perceived barriers to enrollment to cancer clinical trials by age group (<65 vs. ≥65) using the Patient Refusal Questionnaire and the Physician Treatment Questionnaire, respectively. We planned to test four prespecified items by age: two from the Patient Refusal questionnaire (concern about how treatment would be paid for and concern that tests and procedures would take too much time and effort) and two from the Physician Treatment questionnaire (toxicity and patient age as reasons for not discussing participation). A total of 150 patients eligible for a clinical trial who did not participate would give 80% power to detect a difference of 30% between older and younger patients for any of the four prespecified items, assuming a ratio of patients <65 years versus ≥65 years of 2:1, an α value of 0.0125 to adjust for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni adjustment; overall α = .05), and two-sided testing.

Secondary endpoints included the proportion of patients who participated in S0316 and the reasons for nonparticipation in S0316. Barriers to enrollment in therapeutic cancer clinical trials were evaluated, including estimations of the proportion of patients for whom a clinical trial was available, the rate of eligibility, and the rate of clinical trial participation. Finally, among patients who did participate in a clinical trial, the reasons for participation were assessed according to the Patient Participation questionnaire. Comparisons between younger and older patients were assessed in all instances.

Differences in proportions were tested using the χ2 test. Logistic regression was used to assess potential differential patterns of enrollment according to disease type (newly diagnosed vs. recurrent) using an interaction term.

Results

An accrual feasibility analysis was conducted in March 2007, which showed insufficient accrual to continue enrollment to the lung and colorectal strata. These strata were closed on April 15, 2007. The breast stratum reached full accrual and is the focus of this report.

Enrollment Rate

A total of 1,102 patients with breast cancer were enrolled in the study. In all, 23 patients were ineligible: 13 patients had a cancer for which systemic chemotherapy would not be considered, 5 patients did not have cancer, 3 patients were not new to the institution, and 2 patients did not read and understand English. Log data from Seattle Cancer Care Alliance showed an estimated 24% of patients who entered the clinic and were eligible for this study were enrolled. The estimated reasons for nonenrollment to this study were survey ineligibility (24%), patient missed by CRA (28%), patient refusal (27%, mostly due to patient lack of interest or emotional distress), scheduling (2%), and other/miscellaneous (19%).

Patterns of Enrollment

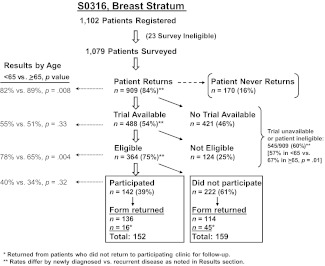

Patterns of enrollment are shown schematically in Figure 1. Of note, 60% of patients were not candidates for clinical trial participation due to either trial unavailability or ineligibility. In addition, 25% of patients for whom a therapeutic clinical trial was available were not eligible for the clinical trial. A reason for ineligibility was identified for 92% of the 124 ineligible patients with an available trial. The most common reasons for ineligibility were comorbid conditions (31%), prior treatment/prior malignancy (21%), and the nature of the tumor (18%; e.g., two simultaneous primary tumors, tumor too small, estrogen/progesterone-receptor negative, metastatic disease). There were no statistically significant differences in reasons for ineligibility by age group (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Among patients who returned to the institution, the clinical trial participation rate was 16% (142 of 909 patients). Older patients were more likely to return to the clinic than younger patients (89% vs. 82%, p = .008), and there was a similar rate of trial availability among those who returned by older versus younger age (51% vs. 55%, p = .33). Older patients were less likely to be eligible if a trial was available (65% vs. 78%, p = .004). However, older patients had similar rates of trial participation when they were eligible (34% vs. 40%, p = .32).

The clinical trial participation rate was lower among recurrent patients (8% vs. 16%, p = .05). Recurrent patients were also less likely to return to the clinic than newly diagnosed patients (66% vs. 88%, p < .001), less likely to have a trial available (33% vs. 56%, p < .001), and less likely to be eligible if a trial was available (54% vs. 76%, p = .005). However, there was no evidence that the age-related decision-making patterns shown in Figure 1 differed by recurrence status (interaction of age and recurrence status ≫.05 in each case).

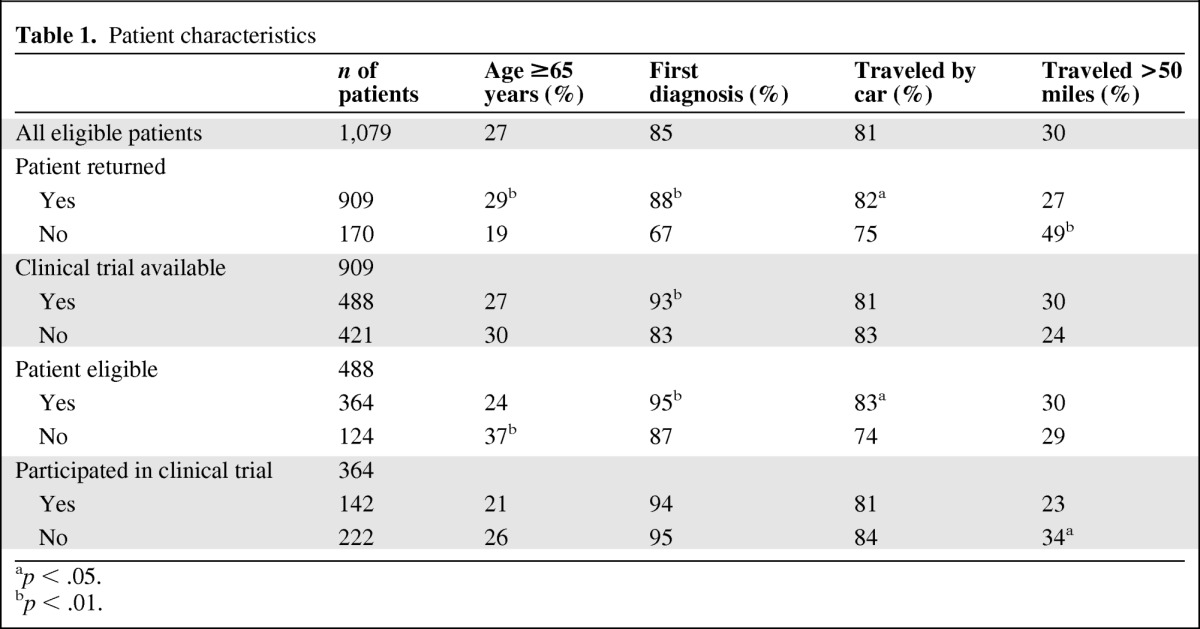

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 27% of all patients eligible for the survey were 65 years or older. Most patients were attending the clinic due to first diagnosis of disease (85%), most traveled by car (81%), and 30% traveled more than 50 miles. Patients who did not return to the clinic for follow-up were significantly younger, less likely to be at their first diagnosis, less likely to have traveled by car, and more likely to have traveled a greater distance. Patients who returned and were eligible for an available clinical trial were more likely to be younger, to be at first diagnosis, and to have traveled by car. The subset of patients who returned, were eligible, and who participated in a clinical trial were less likely to have traveled a long distance.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

ap < .05.

bp < .01.

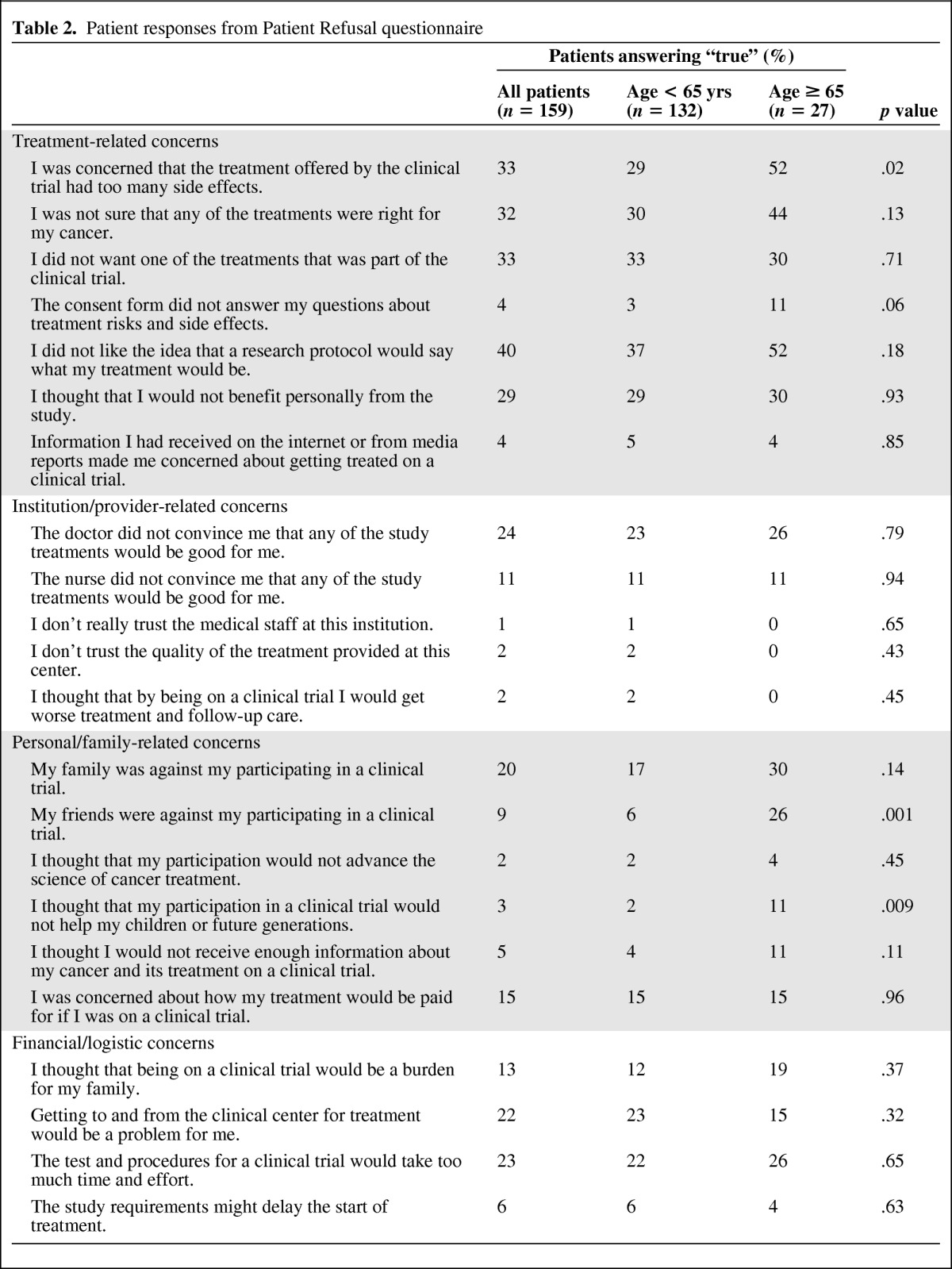

Patients Who Did Not Participate in a Clinical Trial

A total of 159 questionnaires were available for analysis of reasons for nonparticipation in a clinical trial (Table 2). Two items were tested as primary endpoints. There were no differences by age with respect to the proportion of patients who were concerned about how their treatment would be paid for (p = .96) or thought the tests and procedures for a clinical trial would take too much time and effort (p = .65). Older and younger patients' responses as to why they did not participate in a trial were very similar. Significant differences between groups were observed for 3 of 22 survey items.

Table 2.

Patient responses from Patient Refusal questionnaire

Treatment-specific concerns (treatment side effects, dislike of a particular treatment) and negative attitudes towards clinical trials (dislike of the idea that a research protocol would determine treatment, unsure that any of the treatments was right for their cancer) represented the most commonly cited reasons for refusal to participate among both younger and older patients. A higher percentage of older versus younger patients had concerns about treatment side effects (52% vs. 29%, p = .02). A trend towards significance was noted in the percentage citing the lack of autonomy in a trial (52% older vs. 37% younger patients, p = .18).

Family-related and personal concerns appeared to play a greater role in older patients' decisions not to participate in a trial. Although not statistically significant, a greater percentage of older patients cited family opposition as a reason for nonparticipation (30% older vs. 17% younger). Older patients were also significantly more likely to have friends who were opposed to their participation (p = .001). They were also more likely than younger patients to believe their involvement would not benefit future generations (11% vs. 2%, p = .009). There was no difference in the proportion of older and younger patients who felt that being on a trial would be burdensome to family or that transportation to and from the center for treatment would be problematic, despite the finding that fewer older patients traveled by car (72 vs. 84% of younger patients). Very few patients (1%–2%) elected not to participate because of mistrust of their providers or institution.

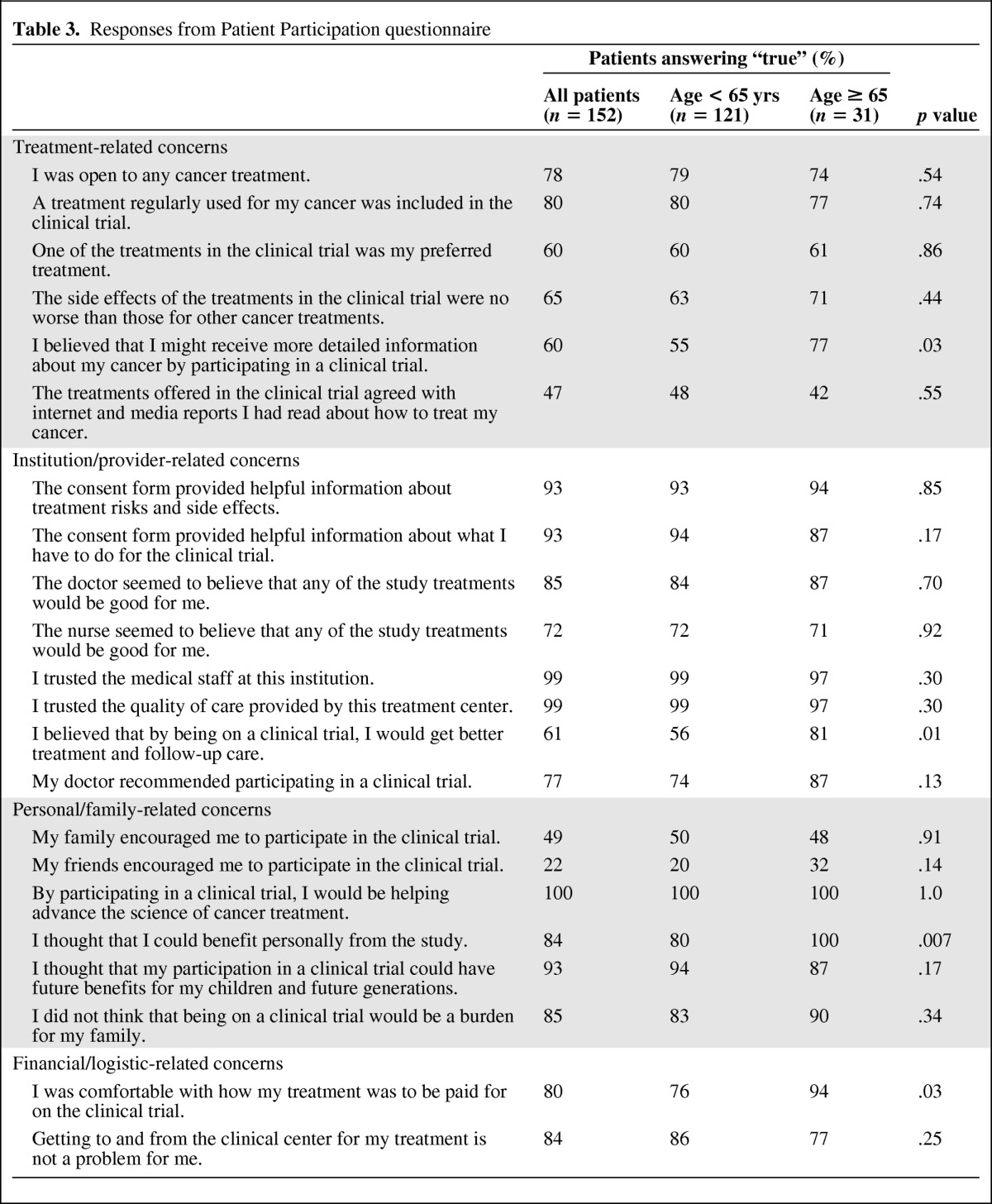

Patients Who Did Participate in a Clinical Trial

A total of 152 questionnaires were available for analysis. Results are shown in Table 3. Reasons for participation were also similar between age groups. Not surprisingly, given the altruism inherent to clinical trial participation, the most common reason cited for participating in a clinical trial was a belief in helping advance the science of cancer treatment (100%). Trust in the medical staff/institution (99%) and belief that participation would benefit future generations (93%) were also cited frequently as reasons for participation. Older patients were no more concerned about side effects of clinical trial treatments and were just as likely as younger patients to feel that they were well educated about the trial via consent forms and from doctors and nurses. Older patients were actually more likely to express the belief that being on a clinical trial would provide better treatment and follow-up care (p = .01) and were more comfortable with how the clinical trial was paid for (p = .03).

Table 3.

Responses from Patient Participation questionnaire

Physician Treatment Questionnaire

The Physician Treatment questionnaire was completed only for those patients who were eligible for an available clinical trial but did not participate. The mean time to completion of the physician survey following the patient treatment decision was 7 days. Physicians discussed trial participation with 71% of patients who did not participate. This rate differed significantly by age group, with clinical trial participation discussed with 76% of patients <65 years and 58% of patients ≥65 years (p = .008).

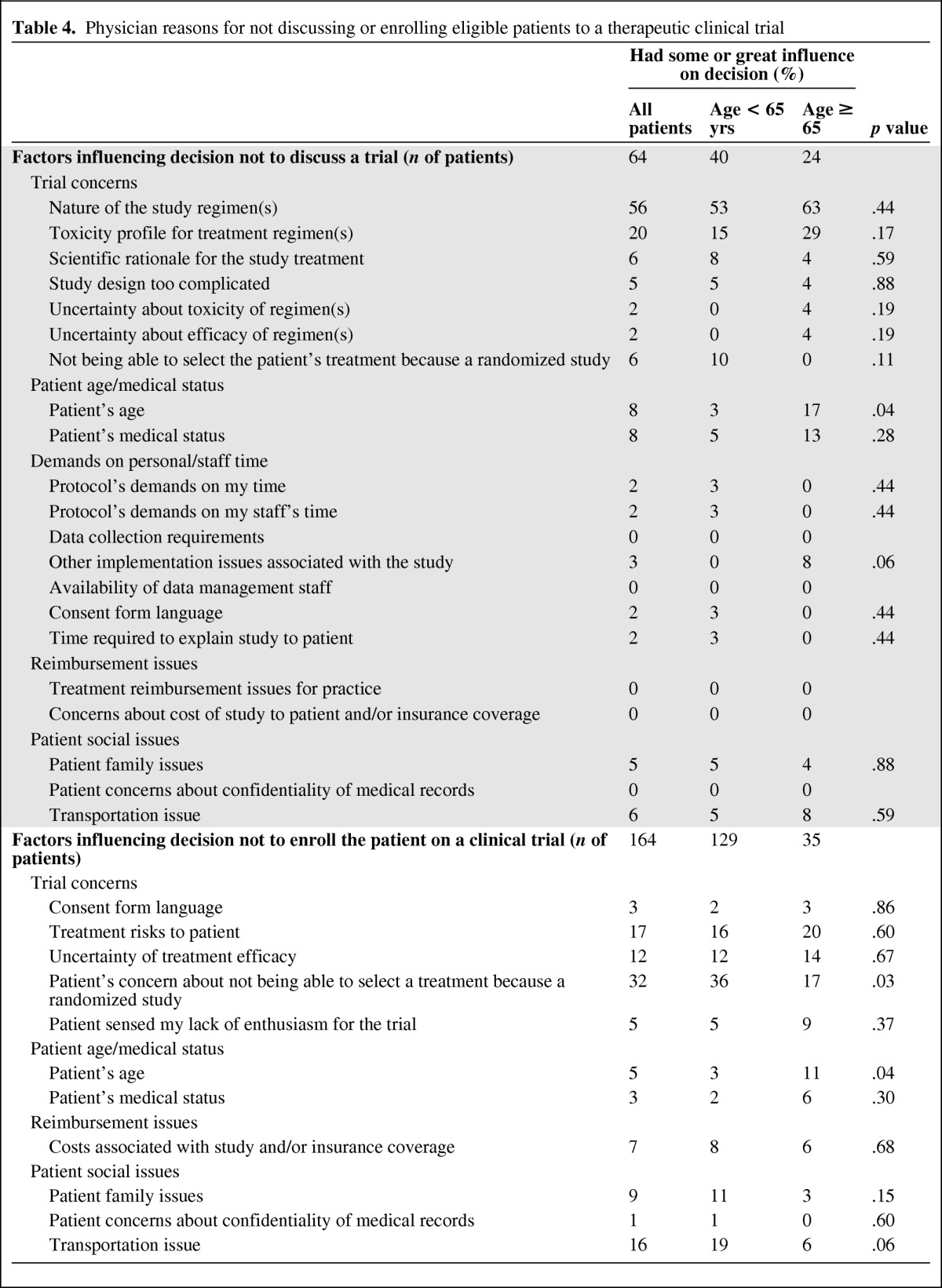

The most common reasons that physicians did not discuss clinical trials with patients were the nature of the study regimens (56% of all patients) and the toxicity profile of the treatment regimens (20% of all patients; Table 4). Among the 164 patients with whom clinical trial participation was discussed but the physician did not enroll the patient, the main reason the physician indicated for not enrolling a patient was the patient's concern about not being able to select a treatment because it was a randomized study (32% of all patients; 17% of patients age ≥65 years vs. 36% of patients <65 years, p = .03; Table 4).

Table 4.

Physician reasons for not discussing or enrolling eligible patients to a therapeutic clinical trial

Two items were tested as primary endpoints (Table 4). There was a trend towards more physicians citing toxicity as a reason not to discuss clinical trials with older patients (29% for patients ≥65 years of age vs. 15% for patients <65 years of age), although this difference was not statistically significant (p = .17). However, a greater proportion of physicians cited patient age as a factor when deciding not to discuss a clinical trial with older patients (17% of patients ≥65 years vs. 3% of patients <65 years, p = .04). If a trial was discussed, physicians also cited patient age as a factor when deciding not to enroll older patients into a trial (11% of patients ≥65 years vs. 3% of patients <65 years, p = .04). Taken together, physicians cited concern about patient's age as a reason the patient did not participate for 14% of older patients and 3% of younger patients (p = .002).

Discussion

This study was the first large prospective survey study to elucidate both physician- and patient-perceived barriers to trial enrollment of older patients in cancer clinical trials. Overall, the majority of patients did not enroll in a clinical trial because of trial unavailability or ineligibility (60%). Nonetheless, clinical trial participation was high in this group of institutions (16%) when compared to national estimates of about 3% [22]. We found that the underrepresentation of older patients in clinical trials was in large part driven by the lack of clinical trials for which they were eligible. Although there were similar rates of trial availability for their cancer, older patients were significantly less likely to be eligible. Our study was not able to elucidate the basis for this disparity in eligibility, as reasons for ineligibility seemed to be similar across age groups.

Younger and older patients shared similar reasons for nonparticipation in clinical trials. In both age groups, the lack of autonomy over treatment choice and treatment toxicities in a clinical trial superseded any concerns about cost or effort related to clinical trials. These findings support and expound upon those of the pilot study by Kemeny et al., which showed lack of autonomy over treatment choice to be the primary reason for trial nonparticipation among patients of all ages [9]. Unlike the Kemeny et al. study, which relied on reporting up to 2 years after diagnosis, the prospective nature of our study likely reduced reporter bias (both from the physician and patient) attributable to the problem of memory loss in reporting of attitudes and behavior. In addition, the larger size of our study population afforded us the ability to identify significant differences in reasons given for trial nonparticipation among older versus younger patients, namely concerns over treatment side effects and lack of support from friends among older patients.

The differences between the perceptions of older patients and their physicians on the reasons for trial underenrollment are highlighted by comparing the results of our study to that of Kornblith et al. [20]. In the physician survey study by Kornblith et al., the majority of physicians cited transportation needs and patient difficulty in understanding the trial as two of the most important reasons why it was difficult to accrue older patients with breast cancer to clinical trials. In our study, neither of these factors were cited as important by the majority of patients ≥65 years in their decision not to participate in a clinical trial. In fact, we found that only 11% of older patients felt the consent form did not answer their questions or that they would not receive enough information about their treatment or cancer if enrolled in a trial.

Not unexpectedly, we found that physicians were significantly less likely to discuss clinical trial participation with older patients despite their eligibility for an available trial. The Kemeny et al. study showed that 34% of patients with stage II breast cancer who were ≥65 years of age were offered clinical trial participation, as compared to 68% of patients <65 years of age [9]. Our study was strengthened by an increased number of physicians surveyed (228 vs. 66 in Kemeny et al.) and a prospective design; therefore, it was able to show that physician concerns over study regimen or toxicity profile were similar for patients who were <65 or ≥65 years of age. However, physicians were far more likely to cite patient age alone as a reason for not discussing or enrolling a patient in a trial among the older patients—a factor which the Kemeny et al. study did not assess.

Age bias has previously been shown to impact oncologists' decisions to offer therapeutic clinical trials to older patients. In one earlier survey study, 51% of U.S. oncologists stated they excluded patients on the basis of age alone [23]. Our results suggest that advancing age remains an independent barrier to trial enrollment. One likely reason for this is that physicians harbor fears about excessive toxicity, intolerance, or lack of survival benefit among older patients. These fears are enabled by a lack of existing data on the efficacy of chemotherapy for patients >70 years of age with preexisting medical conditions [8, 24]. In addition, studies of age-related variation in the response to and toxicity of chemotherapy have yielded conflicting results [25, 26].

A study by Chen et al. provides preliminary information on the ability of older patients (≥70 years of age) to tolerate chemotherapy [27]. The single arm study of 37 patients reported statistically significant but small differences in physical function, functional status, and depression at the end of treatment. However, no significant impact was found on patients' independence, quality of life, or comorbidities. The authors suggested an important role for comprehensive geriatric assessment and monitoring to help both physicians and patients predict the magnitude of effects of chemotherapy on older patients.

To elucidate the risks and benefits of newer treatments, older patients need to be included in all phases of clinical trial development, particularly in phase I studies to assess variable toxicities among older patients and/or those with more comorbidities present. It is critical that investigators develop a priori recruitment goals for patients ≥65 years of age when designing a therapeutic clinical trial. A framework for deciding upon a recruitment goal has been outlined by Bolen et al., which takes into consideration the current adequacy of care, burden of disease among groups, and the known biologic or cultural differences between groups [28]. It has been successfully demonstrated by Moinpour et al. in a prostate cancer randomized controlled prevention trial that set an a priori recruitment goal for African American men based upon the national proportion of African American men in the age subset they were evaluating [29].

Increasing knowledge about older patients' responses to treatment and the impact that comorbidities have on tolerance of treatment will likely reduce the current age disparity in trial enrollment. Given older patients' willingness to participate in clinical trials, it would also be prudent to educate older patients about the benefits of clinical trials soon after diagnosis so that they are empowered to inquire about the possibility of trial enrollment when meeting with their oncologist [12].

Our trial does have potential interpretation and design limitations. First, findings may not represent patient attitudes in the general population because the study was conducted in a set of institutions with dedicated interest in the conduction of clinical trials. Also, by nature of its design, this study suffered from substantial attrition before reasons for nonenrollment could be assessed. In addition, we did not restrict by or capture the stage of disease on patients. Therefore, we could not assess the impact of cancer stage in patient reasons for nonenrollment, although the impact according to newly diagnosed versus recurrent stage was assessed.

Despite its limitations, however, the prospective design of this study and the participation of both community and academic centers lend credence to its generalizability to the broader U.S. population of patients with breast cancer. In addition, it is the internal comparison between age cohorts that was most important and readily evaluable in our study. We demonstrated that if a trial is available and the patient is eligible, older and younger patients enroll at the same rate. We also documented that in the modern systemic treatment era, physicians are still less inclined to offer clinical trials to older individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators of SWOG, all the patients who are represented in our analysis, Patricia Arlauskas from the SWOG Publications Office, and the Associate Chair for the Cancer Control and Prevention Committees of SWOG, Dr. Frank Meyskens.

This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the National Cancer Institute (grants CA32102, CA38926, CA20319, CA45560, CA35119, CA46441, CA37981, CA73590, CA35431, CA14028, and CA37429).

Results presented in part at the 32nd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 10–13, 2009, San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Joseph M. Unger, Carol M. Moinpour, Antoinette J. Wozniak, J. Wendall Goodwin, Pamela A. Williams, Laura F. Hutchins, Carolyn C. Gotay, Kathy S. Albain

Provision of study material or patients: Julie R. Gralow, J. Wendall Goodwin, Laura F. Hutchins

Collection and/or assembly of data: Joseph M. Unger, Julie R. Gralow, Primo N. Lara Jr, Laura F. Hutchins

Data analysis and interpretation: Sara H. Javid, Joseph M. Unger, Julie R. Gralow, Carol M. Moinpour, Carolyn C. Gotay, Kathy S. Albain

Manuscript writing: Sara H. Javid, Joseph M. Unger, Julie R. Gralow, Carol M. Moinpour, Antoinette J. Wozniak, Pamela A. Williams, Carolyn C. Gotay, Kathy S. Albain

Final approval of manuscript: Sara H. Javid, Joseph M. Unger, Julie R. Gralow, Carol M. Moinpour, Antoinette J. Wozniak, J. Wendall Goodwin, Primo N. Lara Jr, Pamela A. Williams, Laura F. Hutchins, Carolyn C. Gotay, Kathy S. Albain

References

- 1.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancik R, Ries LA. Aging and cancer in America. Demographic and epidemiologic perspectives. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmucker DL, Vesell ES. Underrepresentation of women in clinical drug trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:11–15. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinn VW. Women, research, and the National Institutes of Health. Am J Prev Med. 1992;8:324–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration. Guideline for the study and evaluation of gender differences in the clinical evaluation of drugs: Notice. Fed Regist. 1993;58:39406–39416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merkatz RB, Temple R, Sobel S, et al. Women in clinical trials of new drugs: A change in Food and Drug Administration policy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:292–296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307223290429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton P. FDA lifts ban on women in early drug tests, will require companies to look for gender differences. JAMA. 1993;269:2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trimble EL, Carter CL, Cain D, et al. Representation of older patients in cancer treatment trials. Cancer. 1994;74(7 Suppl):2208–2214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2208::aid-cncr2820741737>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2268–2275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melisko ME, Hassin F, Metzroth L, et al. Patient and physician attitudes toward breast cancer clinical trials: Developing interventions based on understanding barriers. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6(1):45–54. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2005.n.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3112–3124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis PM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, et al. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: Understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3554–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klabunde CN, Springer BC, Butler B, et al. Factors influencing enrollment in clinical trials for cancer treatment. South Med J. 1999;92:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199912000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara PN, Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright JR, Crooks D, Ellis PM, et al. Factors that influence the recruitment of patients to Phase III studies in oncology. The Perspective of the Clinical Research Associate. Cancer. 2002;95:1584–1591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne CA, Xu R, Raich P, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an easy-to-read informed consent statement for clinical trial participation: A study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:836–842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor KM, Margolese RG, Soskolne CL. Physicians' reasons for not entering eligible patients in a randomized clinical trial of surgery for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1363–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405243102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson AB, III, Pregler JP, Bean JA, et al. Oncologists' reluctance to accrue patients onto clinical trials: An Illinois Cancer Center study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:2067–2075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.11.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albrecht TL, Blanchard C, Ruckdeschel JC, et al. Strategic physician communication and oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3324–3332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblith AB, Kemeny M, Peterson BL, et al. Survey of oncologists' perceptions of barriers to accrual of older patients with breast carcinoma to clinical trials. Cancer. 2002;95:989–996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yee KWL, Pater JL, Pho L, et al. Enrollment of older patients in cancer treatment trials in Canada: Why is age a barrier? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1618–1623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites in National Cancer Institute cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:812–816. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.12.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson AB, 3rd, Pregler JP, Bean JA, et al. Oncologists' reluctance to accrue patients onto clinical trials: An Illinois Cancer Center study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:2067–2075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.11.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;352:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christman K, Muss HB, Case LD, et al. Chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer in the elderly. The Piedmont Oncology Association experience. JAMA. 1992;268:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crivellari D, Aapro M, Leonard R, et al. Breast cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1882–1890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Cantor A, Meyer J, et al. Can older cancer patients tolerate chemotherapy? Cancer. 2003;97:1107–1114. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolen S, Tilburt J, Baffi C, et al. Defining “success” in recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;106:1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moinpour CM, Atkinson JO, Thomas SM, et al. Minority recruitment in the prostate cancer prevention trial. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:S85–S91. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]