Abstract

Adoptive therapy with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) redirected T cells recently showed remarkable anti-tumor efficacy in early phase clinical trials; self-repression of the immune response by T-cell secreted cytokines, however, is still an issue raising interest to abrogate the secretion of repressive cytokines while preserving the panel of CAR induced pro-inflammatory cytokines. We here revealed that T-cell activation by a CD28-ζ signaling CAR induced IL-10 secretion, which compromises T cell based immunity, along with the release of pro-inflammatory IFN-γ and IL-2. T cells stimulated by a ζ CAR without costimulation did not secrete IL-2 or IL-10; the latter, however, could be induced by supplementation with IL-2. Abrogation of CD28-ζ CAR induced IL-2 release by CD28 mutation did not reduce IL-10 secretion indicating that IL-10 can be induced by both a CD28 and an IL-2 mediated pathway. In contrast to the CD28-ζ CAR, a CAR with OX40 (CD134) costimulation did not induce IL-10. OX40 cosignaling by a 3rd generation CD28-ζ-OX40 CAR repressed CD28 induced IL-10 secretion but did not affect the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, T-cell amplification or T-cell mediated cytolysis. IL-2 induced IL-10 was also repressed by OX40 co-signaling. OX40 moreover repressed IL-10 secretion by regulatory T cells which are strong IL-10 producers upon activation. Taken together OX40 cosignaling in CAR redirected T cell activation effectively represses IL-10 secretion which contributes to counteract self-repression and provides a rationale to explore OX40 co-signaling CARs in order to prolong a redirected T cell response.

Keywords: CD28, IL-10, OX40, adoptive cell therapy, chimeric antigen receptor

Introduction

Adoptive cell therapy with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-redirected T cells showed remarkable anti-tumor efficacy in recent clinical trials.1 Patients' T cells are ex vivo engineered with a CAR which redirects the T cell through the extracellular antibody-derived binding domain toward target cells in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent fashion.2 CAR intracellular signaling domain, which most frequently is the CD3ζ endodomain derived from the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex, mediates T-cell activation upon target engagement and initiates a plethora of effector functions including the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, cytolysis of target cells and amplification of redirected T cells. Both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells can specifically be redirected by an engineered CAR; both T-cell subsets are required for a potent and sustained anti-tumor response.3 CAR redirected T-cell activation, however, is short-term when no appropriate costimulation simultaneously to CD3ζ signaling occurs and when target cells lack costimulatory ligands. A costimulatory endodomain like CD28 was therefore fused to the CD3ζ CAR endodomain to prolong T-cell survival and to produce efficient killing, cytokine release and T-cell proliferation.4-7 Signaling through the fused CD28 endodomain thereby strengthens the CAR redirected T-cell response through the induction of IL-2 and the increase of IFNγ.4 Upon CD28 and CD3ζ TCR mediated activation T cells upregulate “late” costimulatory molecules of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family including 4-1BB (CD137) and OX40 (CD134) which are involved in prolonging T-cell persistence and inducing T-cell memory.8-10 For instance OX40 is upregulated 24 h after antigen engagement in presence of CD28 costimulation11,12 and further augments CD28 activated T-cell responses with respect to proliferation, cytokine responses and survival.13,14 Several lines of evidences imply that the success of a redirected T-cell therapy of cancer depends on the maintenance of T cell effector functions in the long-term which can be ensured by integrating the primary TCR and CD28 signal with late costimulatory signals. Consequently, Pule et al.15 hypothesized that the combination of CD28 and OX40 endodomains in cis with CD3ζ in a CAR will improve redirected T-cell effector functions and enhance anti-tumor activity.

The T-cell response is physiologically limited by various mechanisms, one of which are repressive cytokines like IL-10 which are present in high concentrations in the tumor microenvironment, are produced by both tumor and stroma cells and which impair an anti-tumor response.16 CD28 costimulation of T cells also induces IL-10 secretion17 which in turn compromises T-cell based immunity18 through downregulation of MHC molecules,19 of the CD28 ligands CD80 and CD86 and of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs).20,21 As a consequence the antigen-driven T-cell amplification is turned off, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines is repressed and anti-inflammatory cytokines are released which contribute to a further polarization of the immune response. In addition to effector T cells, CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are potent IL-10 producers moreover repressing the T-cell attack.22 Adoptive T-cell therapy of cancer aims to tip the balance by promoting T-cell activation while reducing repression, both contributing to the overall therapeutic success. We here revealed that (1) CD28-ζ CAR redirected T cells upregulate IL-10 secretion upon antigen engagement, (2) IL-10 is also induced when ζ CAR T cells are activated in presence of IL-2, and (3) that IL-10 induced by either mechanism can be abrogated by co-signaling through OX40 in both CD4+ helper and regulatory T cells. Consequently, combined signaling through a CD28-ζ-OX40 CAR repressed IL-10 without affecting the other T-cell effector functions like secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. We assume such dual costimulatory CAR of benefit in improving T-cell anti-tumor immunity in long-term.

Results

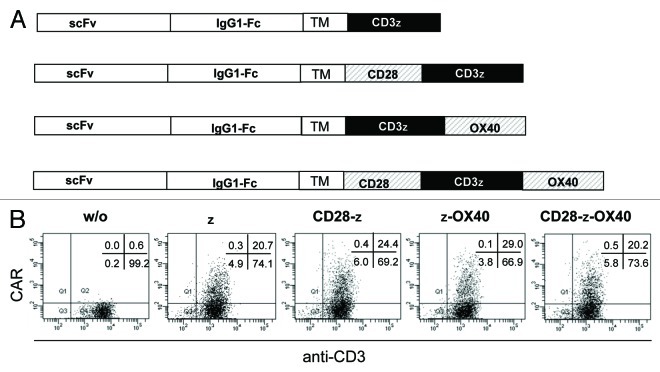

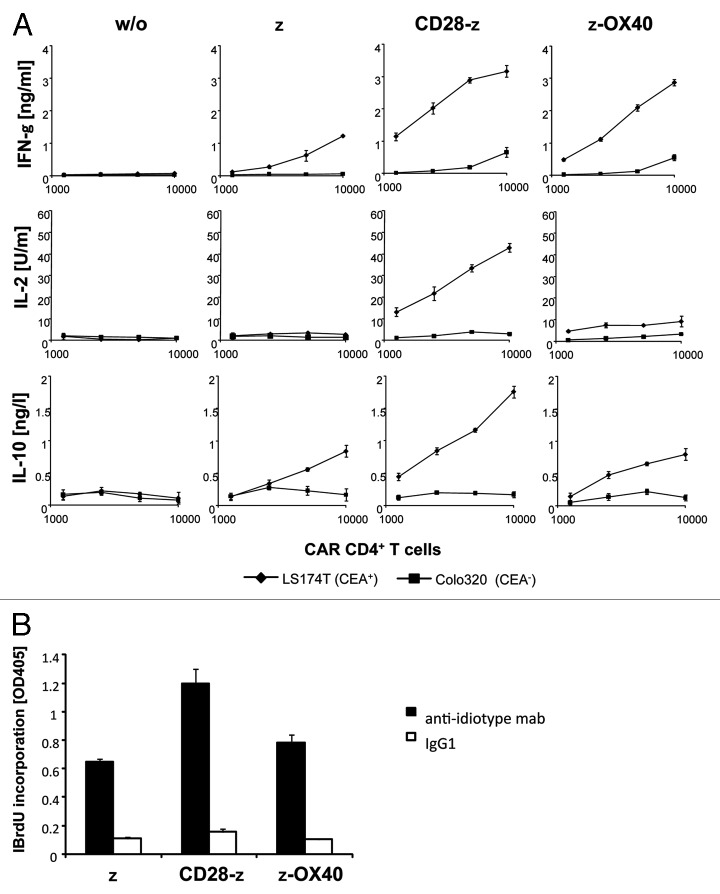

We screened the cytokine profiles of CAR redirected human CD4+ T cells upon engagement of CAR-defined antigen. While the CARs have the same extracellular binding domain for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), the signaling moiety is composed of the CD3ζ endodomain fused to the intracellular CD28 or OX40 chain, respectively, providing different costimuli (Fig. 1A). Upon retroviral transduction, CARs were expressed on the surface of human T cells with nearly same efficiencies (Fig. 1B). A CD3ζ CAR without costimulatory domain was expressed in CD4+ T cells for comparison. Engineered T cells were co-incubated with CEA+ and CEA- tumor cells, respectively, to record CAR-driven T-cell activation. Engineered T cells were activated to secrete IFNγ upon co-incubation with CEA+ but not with CEA- tumor cells demonstrating the specificity of CAR mediated T-cell activation (Fig. 2A). IFNγ secretion was substantially enhanced by CD28 and OX40 costimulation, respectively. IL-2, however, is secreted only upon CD28 costimulation. T-cell amplification was most effectively induced by the CD28ζ CAR and less by ζ and ζOX40 CAR stimulation (Fig. 2B). CD28ζ CAR engagement moreover induced secretion of IL-10 in high levels which were much lower without CD28 or with OX40 costimulation.

Figure 1. CAR expression by engineered T cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the expression cassettes for the anti-CEA chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) which harbor the same extracellular binding domains and different signaling endodomains. TM: transmembrane domain. (B) CD4+ T cells were retrovirally transduced to express the respective CAR on the cell surface. CAR expression was recorded by incubation with a FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb and a PE-conjugated anti-human IgG1 mAb, which binds to the extracellular CAR spacer domain, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Figure 2. CD28ζ CAR induces IL-10 secretion by engineered T cells. CD4+ T cells were engineered with the anti-CEA CAR and (A) coincubated (1.25 × 103−1 × 104 CAR T cells/well) for 48 h with CEA+ LS174T or CEA- Colo320 tumor cells (each 2.5 x 104 cells/well) or (B) incubated (2.5 x 104/well) in microtiter plates that were coated with 10 µg/ml of the CAR-specific anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 which binds to the CAR BW431/26 scFv domain to specifically stimulate CAR T cells, or an isotype control mAb (IgG1). The number of CAR expressing T cells was adjusted to equal numbers by adding non-transduced cells from the same donor. Cytokines in the supernatant were recorded by ELISA, proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation. Data represent the mean of triplicates ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

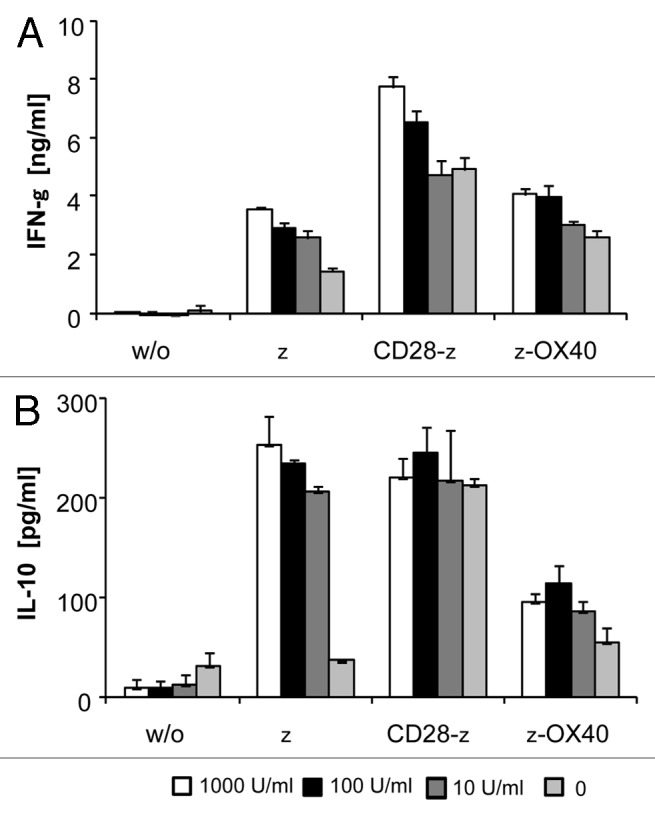

Since CD28 costimulation in contrast to OX40 additionally induced IL-2, we asked whether IL-10 secretion is induced by IL-2 independently of costimulation. To address the question in a thoroughly controlled setting, ζCAR engineered T cells were specifically stimulated by the immobilized anti-idiotypic antibody BW2064, which is directed toward the scFv CAR domain, in presence or absence of added IL-2. As shown in Figure 3, IL-2 enhanced, along with IFNγ, IL-10 secretion of ζ CAR engineered T cells upon CAR engagement with antigen. IL-2 did not induce IL-10 secretion, however, when T cells were stimulated by the OX40ζ CAR. As controls IL-2 increased IL-10 secretion by CD28ζ CAR modified T cells whereas IL-2 did not induce IL-10 in non-modified T cells without ζ stimulation. Taken together, IL-2 in the context of ζ CAR signaling induced IL-10 which is not the case in presence of OX40 costimulation.

Figure 3. Added IL-2 induced IL-10 secretion in ζ CAR, but not in ζ-OX40 CAR stimulated T cells. CAR engineered CD4+ T cells (2.5 × 104 cells/well) were incubated for 48 h in the presence of added IL-2 (10–1,000 U/ml) in microtiter plates coated with the CAR-specific anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 (2.5 µg/ml coating solution). Plates coated with an antibody of irrelevant specificity served as control (w/o). Culture supernatants were recorded for cytokines by ELISA. Data represent the mean of triplicates ± SEM. A representative experiment out of three is shown.

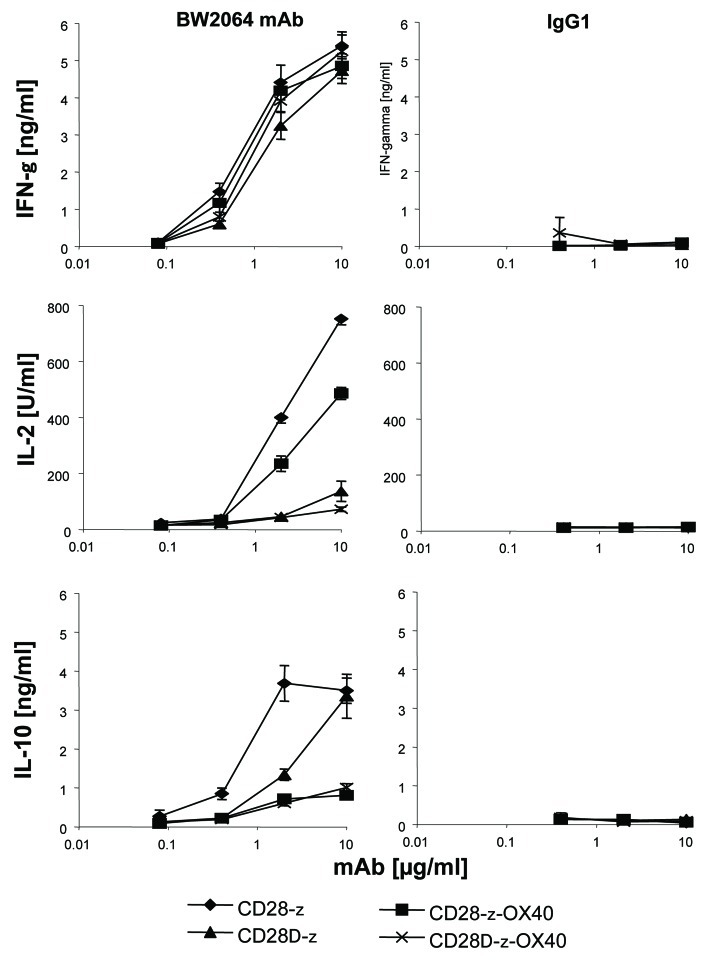

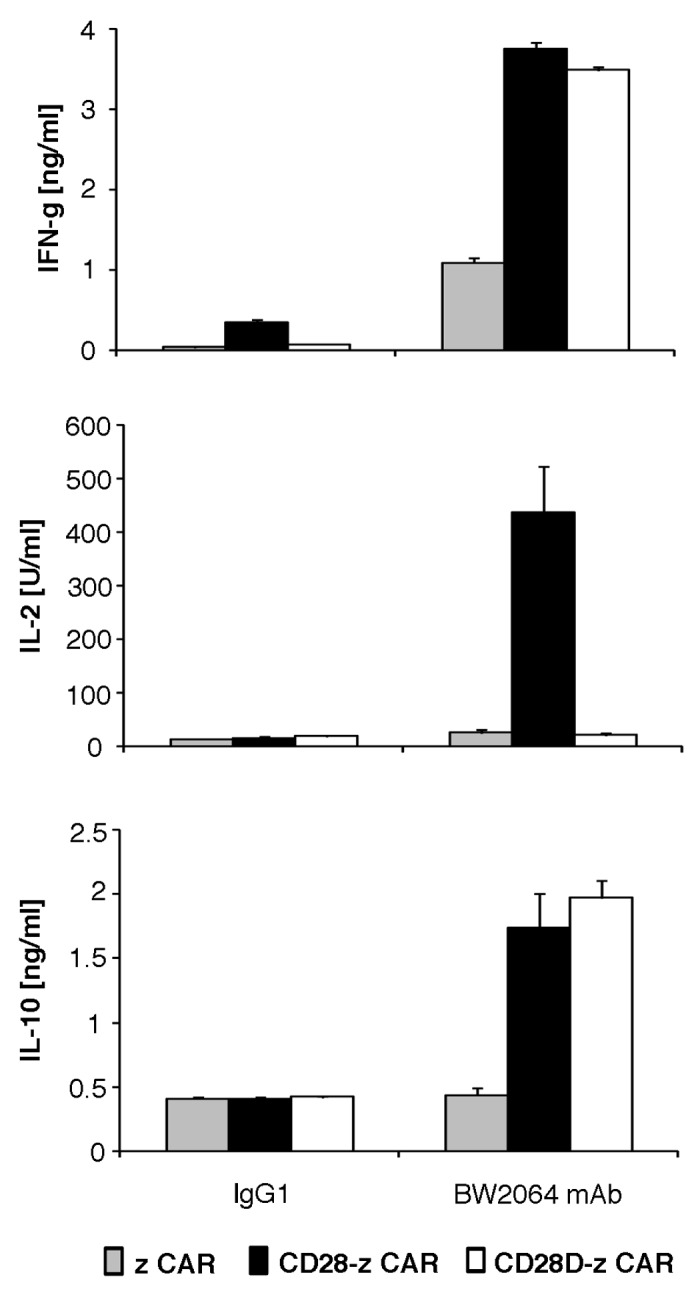

Since CD28ζ CAR signaling induced IL-2 secretion we asked whether IL-10 secretion is due to autocrine acting IL-2 upon CD28 mediated release. We abrogated IL-2 release by abrogating lck binding to CD28 by mutation of the lck binding motif in the CAR CD28 signaling moiety. CD4+ T cells were engineered with the mutated CD28Δζ CAR or for comparison with the ζ and CD28ζ CAR, respectively, and stimulated through binding to the CAR antigen. As summarized in Figure 4, the CD28Δ CAR did not induce IL-2 secretion while IL-10 and IFNγ secretion are not altered compared with the wild-type CD28ζ CAR. Cytokine secretion was specifically induced by CAR engagement of antigen because coincubation with an irrelevant antigen did not induce IL-10 secretion. Data indicate that at least two pathways can induce IL-10 secretion in CAR engineered T cells, one via IL-2 and the other via CD28 independently of IL-2 induction.

Figure 4. The modified CD28Δζ CAR which lacks IL-2 induction also mediated IL-10 secretion. The anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 which binds to the scFv domain of the CAR and an isotype control mAb IgG1 were coated onto microtiter plates (10 µg/ml coating solution). CD4+ T cells were engineered to express CARs with ζ, CD28ζ and CD28Δζ signaling domains, respectively, and incubated for 48 h in coated microtiter plates (2.5 × 104 CAR T cells/well). Culture supernatants were tested by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-10, respectively. The assays were performed three times in triplicates; data represent mean values ± SEM of a representative experiment.

Since ζOX40 CAR redirected T cells did not produce IL-10 in presence of added IL-2, we asked whether OX40 costimulation prevents CD28 mediated IL-10 secretion. To address the issue, we made use of a CD28-OX40 dual costimulatory CAR. For comparison, we used a CD28Δζ and CD28ΔOX40 CAR which were deficient in IL-2 induction. CARs were expressed in CD4+ T cells and triggered by immobilized, CAR-specific antigen. As summarized in Figure 5, CD28ζ CAR T cells did not secrete IL-10 when costimulated by OX40. IL-10 is also repressed in presence of OX40 co-signaling when T cells were stimulated by the mutated CD28Δζ CAR. For comparison, all CARs induced similar amounts of secreted IFNγ indicating a similar T cell activation potency. IL-2 is secreted upon CD28ζ and CD28ζOX40 CAR signaling indicating the functional integrity of the CD28 domain while IL-2 is not induced by the mutant CD28Δζ and the CD28ΔOX40 CAR as expected. In summary, data indicate that OX40 in a combined CD28-OX40 CAR repressed CD28 induced IL-10 secretion by redirected T cells.

Figure 5. OX40 costimulation repressed CD28 CAR mediated IL-10 secretion in redirected T cells. Serial dilutions of the anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 and an isotype control mAb IgG1 were coated onto microtiter plates (0.01–10 µg/ml). CD4+ T cells were engineered with the CEA-specific CD28ζ, CD28Δζ, CD28OX40, and CD28ΔOX40 CAR, respectively, and incubated for 48 h in coated microtiter plates (2.5 × 104 CAR T cells/well). Culture supernatants were recorded by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-10, respectively. The assays were performed three times; data represent mean values of triplicates ± SEM of a representative experiment.

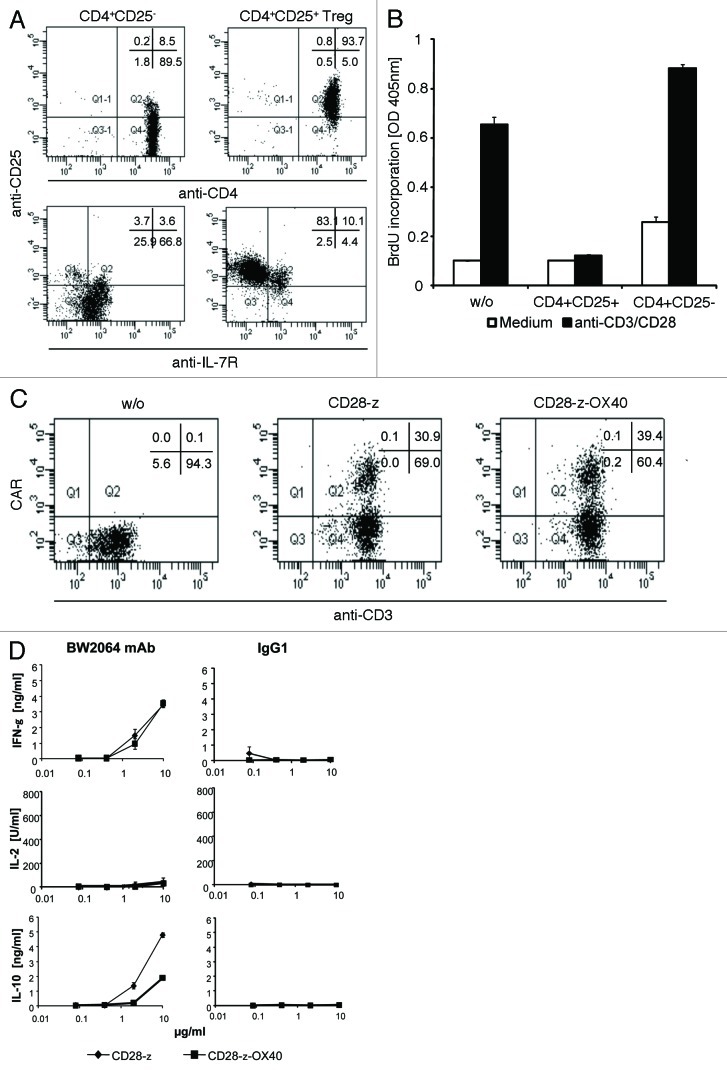

Treg cells are strong producers of IL-10. We therefore asked whether CAR mediated OX40 co-signaling does also repress IL-10 secretion by Treg cells. Human CD4+CD25+IL-7R- T cells were isolated from the peripheral blood (Fig. 6A). Cells were activated and expanded as recently described.23 Expanded cells were verified as Treg cells by a standard suppressor assay (Fig. 6B). We engineered Treg cells with CD28ζ and CD28OX40 CARs with similar efficiencies (Fig. 6C). Upon CD28ζ and CD28OX40 CAR redirected activation, Treg cells secreted same amounts of IFNγ indicating a similar degree in CAR mediated activation (Fig. 6D). No IL-2 is induced as expected for Treg cells. CD28ζ CAR modified Treg cells, however, secreted high amounts of IL-10 which were substantially reduced when redirected by the CD28OX40 CAR. Data indicate that OX40 costimulation as provided by a CD28OX40 CAR repressed IL-10 secretion in Treg cells as it did in effector T cells.

Figure 6.

IL-10 secretion was repressed in CD28OX40 CAR redirected Treg cells. (A) Isolation of CD4+CD25+IL-7R- Treg cells. CD4+CD25-IL-7R+ and CD4+CD25+IL-7R- T cells were isolated from peripheral blood by MACS procedures. Isolated T cells were incubated with anti-IL-7R-FITC, anti-CD25-PE and anti-CD4-APC mAbs, respectively, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Isolated T reg cells were activated and expanded in the presence of IL-2 (1,000 U/ml) on solid phase bound agonistic anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs (each 10 µg/ml). Cells were rested for 48 h without stimuli and tested for suppressor activity. Allogeneic CD4+ responder cells (1 × 104 cells/well) and Treg cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were cocultivated for 5 d in the presence or absence of agonistic anti-CD3 (10 µg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml) antibodies, pulsed with BrdU and proliferation determined by a cell ELISA. (C) CD4+CD25+IL-7R- regulatory T cells express CARs with high efficacy. Isolated CD4+CD25+IL-7R- regulatory T cells were retrovirally transduced to express the anti-CEA CARs which harbor either the CD28ζ or CD28ΟX40 signaling domain. CAR engineered T cells were detected by a PE-conjugated anti-human IgG1 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Serial dilutions of the anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 were coated on microtiter plates (0.01 - 10 µg/ml). CD4+CD25+IL7R- T cells were engineered with the CD28ζ or CD28-CD3ζOX40 CAR, respectively, adjusted to equal numbers of CAR expressing cells and incubated for 48 h in coated microtiter plates (1 × 104 CAR T cells/well). Culture supernatants were recorded by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-10, respectively. The assays were performed three times; data represent mean values of triplicates ± SEM of a representative experiment.

Discussion

We here demonstrate that CD28ζ CAR redirected T cells secrete high amounts of IL-10 which is also the case when ζ CAR T cells were stimulated in presence of IL-2. Since CD28Δζ CAR T cells which do not produce IL-2 upon CAR engagement still secrete IL-10 we conclude that IL-10 secretion by activated T cells can be induced by CD28 costimulation independently of IL-2 signaling. Simultaneous OX40 costimulation by a CAR repressed both IL-2 and CD28 mediated IL-10 secretion. IL-10 repression was not due to an impaired overall signaling because IFNγ and IL-2 secretion were not altered by OX40 costimulation.

Endodomains from single costimulatory molecules linked to CD3ζ in a CAR are sufficient to activate the killing machinery and to increase T-cell proliferation and IFNγ release.24 OX40 and 4-1BB CARs less enhance T cell proliferation when inserted in cis in a ζCAR compared with a CD28ζ CAR.24 OX40 cosignaling did not substantially increase the cytolytic activity and T cell amplification. While CD3ζ CAR T cells fail to sustain their function in the long-term, T cells redirected by the CD28-OX40 CAR produced lasting anti-tumor activity in a xenograft metastatic model.6,25 CD28-OX40 redirected T cells, however, were unable to completely eradicate the disease which may be due in part to inefficiently sustaining human T cell function in the mouse. We assume that the combined CD28-OX40 CAR signaling moreover promotes the expansion of naïve T cells in absence of the appropriate ligands on target cells or APCs. While CD28 activation initiates clonal expansion of naïve T cells and IL-2 secretion, in the absence of additional cooperative signals only a small number of antigen-responding T cells persist and the majority of T cells undergo apoptosis.26 In this context fusion of the “late” costimulatory OX40 signal in cis to the CD28ζ “early” signal in a combined CAR will be of benefit compared with OX40 or CD28 costimulation only. Consequently, incorporation of the OX40 signaling domain favors the expansion, persistence and effector functions of those cells27 which likely occurs because both costimulatory domains produce greater activation of NFκB than either domain alone. CD28 and OX40 activate NFκB by different pathways, i.e., CD28 via Vav and PI3K and OX40 via TRAF2. NFκB independent signals via Akt and AP1 are additionally transmitted.10,28

The different costimulatory CARs produce different patterns of secreted cytokines; CD28ζ CAR T cells in particular produce IL-2 and IL-10 which both were not secreted by ζOX40 CAR T cells.25 T cells redirected by the CD28-OX40 CAR produced IL-2 and increased IFNγ after stimulation which is in accordance to previous reports.6,15 The CD28Δζ CAR which did not produce IL-2 due to the mutated lck binding domain in the CD28 signaling moiety displays a more favorite panel of secreted cytokines with high IFNγ levels without providing IL-2 supporting Treg cell survival and repression.29 Proliferation of engineered effector T cells is likewise sustained by the modified CAR. Pule et al.15 reported that CD3ζ and OX40ζ CAR T cells did not produce IL-10, which is in accordance to our observation, CD28-OX40 CAR T cells, however, were found to secrete IL-10 in nearly the same but hardly detectable levels as CD28 CAR T cells. The divergent observation may be due to the different arrangement of the signaling domains in cis described in the Pule report,15 i.e., a CAR with CD28 followed by OX40 followed by CD3ζ, whereas we used a CAR with OX40 in a terminal position. Both CARs have CD28 in a membrane proximal position and have the same trans-membrane domain which determines the level of surface CAR expression.30 CARs in which CD28 is merely membrane distal are not functional in CD3ζ costimulation.31 CARs with CD28 trans-membrane domain show higher expression on the T-cell surface than CARs with a CD3ζ membrane domain which is in accordance to Pule et al.15 Combining “early” with “late” costimulatory signals in cis in a CAR, however, has its limitation since it does not completely recapitulate the temporo-spatial features of the sequential signaling events as they physiologically occur to sustain T-cell activation.7,27

Repression of IL-10 by signaling through a CD28-ζ-OX40 CAR likely prevents auto-repression of CAR redirected T cells through a prolonged cellular immune response. IL-10 repression will moreover be of interest when combining the “T-body” approach with vaccination against tumor associated antigens32 and prevent accumulation of IL-10 in the tumor microenvironment that in turn may compromise the anti-tumor response.16

There may be concerns to transduce T cells by a retrovirus with a CAR with strong and lasting proliferative signals. Retroviral integration potentially can induce T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia due to LMO2 overexpression in patients with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency who received hematopoietic stem cells engineered to constitutively express the common γ-chain receptor.33 In contrast to retroviral modification of hematopoietic stem cells, engineering mature T cells in experimental models did not or very rarely result in malignant transformation.34,35

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

293T cells are human embryonic kidney cells that express the SV40 large T antigen.36 The CEA-expressing colon carcinoma cell line LS174T (ATCC CCL 188) and the CEA-negative cell line Colo320 (ATCC CCL 220.1) were obtained from ATCC. The anti-CEA mAb BW431/26 and the anti-id mAb BW2064/36 with specificity for the anti-CEA mAb BW431/26 were described earlier.37 OKT3 (ATCC CRL 8001) is a hybridoma cell line that produces the anti-CD3 mAb OKT3. All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, 10% (v/v) FCS (all Life Technologies). OKT3 mAb was affinity purified from hybridoma supernatants utilizing goat anti-mouse IgG2a antibodies (Southern Biotechnology) that were immobilized on N-hydroxy-succinimid-ester-(NHS)-activated sepharose as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences). The goat anti-human IgG antibody and its biotin-, FITC- or PE-conjugated F(ab´)2 derivatives were purchased from Southern Biotechnology. The anti-IFNγ mAb NIB42 and the biotinylated anti-IFNγ mAb 4S.B3, the anti-IL-2 mAb 5344.111 and the biotinylated anti-IL-2 mAb B33–2, and the anti-human IL-10 mAb 4D5 and the biotinylated anti-human IL-10 mAb 6D4/D6/G2 were all purchased from BD Bioscience.

Generation and expression of recombinant anti-CEA CARs

The generation of the retroviral expression cassettes for the recombinant BW431/26-scFv-Fcζ, the BW431/26-scFv-Fc-CD28ζ, the BW431/26-scFv-Fc-OX40 and the BW431/26-scFv-Fc-CD28OX40 CARs was described in detail.4,24,38 Retroviral transduction of T cells with CARs was described in detail elsewhere;36,38 CAR expression was monitored by flow cytometric analyses. Isolation, propagation and retroviral gene transfer of CD4+CD25+FoxP3high regulatory T cells was performed as recently described.23 The CD28 endodomain with a mutated Lck binding motive was generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Briefly, retroviral expression vectors for recombinant CARs harboring a chimeric CD28ζ or CD28OX40 signaling domain were PCR-amplified utilizing the following oligonucleotids: S-CD28Δ (sense): cccacccgcaagcattaccagGCctatgccGCCGcacgcgacttcgcaGcctAT; AS-CD28δ (antisense): ATAGGCTGCGAAGTCGCGTGCGGCGGCATAGGCCTGGTAATGCTTGCGGGTGGG.

The reaction product was treated with DpnI, transformed into E. coli DH5, and mutations were verified by sequence analysis.

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS)

Peripheral blood lymphocytes from healthy donors were isolated by density centrifugation and monocytes were depleted by plastic adherence. Non-adherent lymphocytes were washed with cold PBS containing 0.5% (w/v) BSA, 1% (v/v) FCS, 2 mM EDTA. CD4+ T cells were isolated by magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) utilizing the “CD4+ T cell isolation kit” (Miltenyi Biotec) routinely resulting in > 95% purity. CD4+CD25+FoxP3high Treg cells were isolated utilizing the “Treg isolation kit II” (Miltenyi Biotec).

Immunofluorescence analyses

CAR engineered T cells were identified by two color immunofluorescence utilizing a PE-conjugated F(ab')2 anti-human IgG1 antibody (0.1 μg/ml) and a FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb (UCHT-1, 1:20). Regulatory T cells were identified by multi color immunofluorescence utilizing an APC-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb (Dako), a PE-conjugated anti-CD25 mAb (Miltenyi) and a FITC-conjugated anti-CD127 (IL-7R) mAb (eBioscience). Immunofluorescence was analyzed using a FACScanTM cytofluorometer equipped with the CellQuest research software (Becton Dickinson).

CAR mediated T cell activation

CD4+ T cells were engineered with anti-CEA CARs and cultivated in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2 (10–1,000 U/ml) in microtiter plates (Polysorb, Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) (2.5 × 104 receptor grafted T cells/well) which were pre-coated with the anti-idiotypic mAb BW2064 or an IgG1 mAb for control (each 0.01–10 µg/ml). In another set of experiments CAR engineered T cells were cocultivated for 48 h in 96-well round bottom plates with CEA+ LS174T and CEA- Colo320 tumor cells (each 2.5 × 104 cells/well). After 48 h culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-10 secretion, respectively. Briefly, cytokines in the supernatants were bound to the solid phase capture antibodies (each 1 µg/ml) and detected by the biotinylated detection antibodies (each 0.5 µg/ml). The reaction product was visualized by a peroxidase-streptavidin-conjugate (1:10,000) and ABTS® (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). T cell proliferation was determined by BrdU-incorporation utilizing the “5-Bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine Labeling and Detection Kit III” (Roche Biochemicals).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Deutsche Krebshilfe, Bonn, the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung, München, and the Köln Fortune Program of the Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- IFN

interferon

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- scFv

single-chain fragment of variable region antibody

- XTT

2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulphonyl)-5[(phenyl-amino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/19855

References

- 1.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, Schindler DG. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:720–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moeller M, Kershaw MH, Cameron R, Westwood JA, Trapani JA, Smyth MJ, et al. Sustained antigen-specific antitumor recall response mediated by gene-modified CD4+ T helper-1 and CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11428–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hombach A, Sent D, Schneider C, Heuser C, Koch D, Pohl C, et al. T-cell activation by recombinant receptors: CD28 costimulation is required for interleukin 2 secretion and receptor-mediated T-cell proliferation but does not affect receptor-mediated target cell lysis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1976–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finney HM, Akbar AN, Lawson ADG. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J Immunol. 2004;172:104–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkie S, Picco G, Foster J, Davies DM, Julien S, Cooper L, et al. Retargeting of human T cells to tumor-associated MUC1: the evolution of a chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunol. 2008;180:4901–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai C, Mihara K, Andreansky M, Nicholson IC, Pui C-H, Geiger TL, et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18:676–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawicki W, Bertram EM, Sharpe AH, Watts TH. 4-1BB and OX40 act independently to facilitate robust CD8 and CD4 recall responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:5944–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serghides L, Bukczynski J, Wen T, Wang C, Routy J-P, Boulassel M-R, et al. Evaluation of OX40 ligand as a costimulator of human antiviral memory CD8 T cell responses: comparison with B7.1 and 4-1BBL. J Immunol. 2005;175:6368–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:609–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderhead DM, Buhlmann JE, van den Eertwegh AJ, Claassen E, Noelle RJ, Fell HP. Cloning of mouse Ox40: a T cell activation marker that may mediate T-B cell interactions. J Immunol. 1993;151:5261–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redmond WL, Ruby CE, Weinberg AD. The role of OX40-mediated co-stimulation in T-cell activation and survival. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:187–201. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i3.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen AI, McAdam AJ, Buhlmann JE, Scott S, Lupher ML, Jr., Greenfield EA, et al. Ox40-ligand has a critical costimulatory role in dendritic cell: T cell interactions. Immunity. 1999;11:689–98. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiba H, Oshima H, Takeda K, Atsuta M, Nakano H, Nakajima A, et al. CD28-independent costimulation of T cells by OX40 ligand and CD70 on activated B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:7058–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulè MA, Straathof KC, Dotti G, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK. A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol Ther. 2005;12:933–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato T, Terai M, Tamura Y, Alexeev V, Mastrangelo MJ, Selvan SR. Interleukin 10 in the tumor microenvironment: a target for anticancer immunotherapy. Immunol Res. 2011;51:170–82. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rafiq K, Charitidou L, Bullens DM, Kasran A, Lorre´ K, Ceuppens J, et al. Regulation of the IL-10 production by human T cells. Scand J Immunol. 2001;53:139–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5771–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, Roncarolo MG, te Velde A, Figdor C, et al. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corinti S, Albanesi C, la Sala A, Pastore S, Girolomoni G. Regulatory activity of autocrine IL-10 on dendritic cell functions. J Immunol. 2001;166:4312–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yue FY, Dummer R, Geertsen R, Hofbauer G, Laine E, Manolio S, et al. Interleukin-10 is a growth factor for human melanoma cells and down-regulates HLA class-I, HLA class-II and ICAM-1 molecules. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:630–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970516)71:4<630::AID-IJC20>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maynard CL, Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zindl CL, Rudensky AY, et al. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3- precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:931–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hombach AA, Kofler D, Rappl G, Abken H. Redirecting human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood with pre-defined target specificity. Gene Ther. 2009;16:1088–96. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hombach AA, Abken H. Costimulation by chimeric antigen receptors revisited the T cell antitumor response benefits from combined CD28-OX40 signalling. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2935–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yvon E, Del Vecchio M, Savoldo B, Hoyos V, Dutour A, Anichini A, et al. Immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma using genetically engineered GD2-specific T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5852–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gramaglia I, Jember A, Pippig SD, Weinberg AD, Killeen N, Croft M. The OX40 costimulatory receptor determines the development of CD4 memory by regulating primary clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2000;165:3043–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Dotti G, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14:1264–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane LP, Weiss A. The PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway and T cell activation: pleiotropic pathways downstream of PIP3. Immunol Rev. 2003;192:7–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2003.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kofler DM, Chmielewski M, Rappl G, Hombach A, Riet T, Schmidt A, et al. CD28 costimulation Impairs the efficacy of a redirected t-cell antitumor attack in the presence of regulatory t cells which can be overcome by preventing Lck activation. Mol Ther. 2011;19:760–7. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bridgeman JS, Hawkins RE, Hombach AA, Abken H, Gilham DE. Building better chimeric antigen receptors for adoptive T cell therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2010;10:77–90. doi: 10.2174/156652310791111001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finney HM, Lawson AD, Bebbington CR, Weir AN. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J Immunol. 1998;161:2791–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang H-R, Gilham DE, Mulryan K, Kirillova N, Hawkins RE, Stern PL. Combination of vaccination and chimeric receptor expressing T cells provides improved active therapy of tumors. J Immunol. 2006;177:4288–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Lunzen J, Glaunsinger T, Stahmer I, von Baehr V, Baum C, Schilz A, et al. Transfer of autologous gene-modified T cells in HIV-infected patients with advanced immunodeficiency and drug-resistant virus. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1024–33. doi: 10.1038/mt.sj.6300124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newrzela S, Cornils K, Heinrich T, Schläger J, Yi J-H, Lysenko O, et al. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis can contribute to immortalization of mature T lymphocytes. Mol Med Published Online First. 2011;27 doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weijtens ME, Willemsen RA, Hart EH, Bolhuis RL. A retroviral vector system ‘STITCH’ in combination with an optimized single chain antibody chimeric receptor gene structure allows efficient gene transduction and expression in human T lymphocytes. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1195–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaulen H, Seemann G, Bosslet K, Schwaeble W, Dippold W. Humanized anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody: strategies to enhance human tumor cell killing. Year Immunol. 1993;7:106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hombach A, Wieczarkowiecz A, Marquardt T, Heuser C, Usai L, Pohl C, et al. Tumor-specific T cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: CD3 zeta signaling and CD28 costimulation are simultaneously required for efficient IL-2 secretion and can be integrated into one combined CD28/CD3 zeta signaling receptor molecule. J Immunol. 2001;167:6123–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]