Abstract

We aim to provide an overview of clinical and demographical features and neuropathological research on frontotemporal dementia (FTD) from China over the past decade. We reviewed the demographic features, clinical presentations, and neuropathology of the FTD-spectrum disorders from the 49 cases in China published since 1998. On the basis of these findings, we retrospect the history and speculate on future progress in terms of FTD in China. We found that most published papers comprise case reports with a few retrospective studies with small sample sizes. Behavior variant FTD (bvFTD) was the most common diagnostic subtype, of which 35% were associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Parkinsonian syndrome. More than 47% patients with FTD had age onset before 65. There were no differences in age of onset and sex distribution between diagnostic subtypes. The spectrum of neuropathological diagnosis of bvFTD was frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD) with tau protein or ubiquitin-immunopositive inclusions, and FTLD without intracellular inclusions. Median survival in bvFTD was 14 years. This paper provides an overview of the current status and pointers for future research directions of FTD in China.

1. Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a clinically and pathologically heterogeneous syndrome, characterized by progressive decline in behavior or language functions associated with frontal and temporal lobe degeneration (FTLD) [1–4]. Although FTD was first described in the early 1900s as an early-onset disorder presenting before the age of 65, it has only recently been appreciated as a leading cause of dementia, and to be more common than previously recognized in advanced age [5]. Extensive worldwide studies on FTD have been conducted, including epidemiological investigations, cohort, and retrospective studies [6–8]. An interesting study, in terms of the distribution of FTD across four ethnic groups, claimed that it was as common in Asians as Caucasians [9]. Unfortunately, the epidemiological and demographic characteristics of FTD in China have not been investigated to date, where millions of patients suffer from Alzheimer's disease (AD) [10, 11]. Given that FTD is the second most common early-onset dementia after AD in the west [1–4], the epidemiology of FTD of China is of considerable interest.

Since the introduction of standardized clinical diagnostic criteria for FTD [12] into China, there has been an increasing interest in each of the three clinical variants: bvFTD [13–28], semantic dementia (SD) [29–31], and progressive noninfluent aphasia (PFNA) [32–37]. However, the level of research has been limited to case reports and occasional retrospective studies with small sample size. Diagnostic accuracy remains a problem, and there is a lack of collaboration between study centers or sites [27]. As a result, the profile of FTD in China remains obscure compared to the western world.

We reviewed the demographic features, clinical presentations, and neuropathology of the FTD-spectrum disorders from the 49 cases in China published since 1998. On the basis of these findings, we speculate on future progress in China and highlight the importance of international collaboration.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We first searched the Cochrane Library (issue 1, 2011) for all systematic reviews that included cases of Chinese FTD. Subsequently, we searched MEDLINE (1948 to present), EMBASE (1980 to present), PsychInFO (1987 to present), and Chinese main medical databases: Chongqing VIP Database (VIP), Wan Fang Database, Chinese hospital knowledge database (CHKD), and Chinese biomedical database (CBM-disc, 1978 to present) were searched to locate all case reports or case series published in the last 12 years (1998–2010) associated with FTD. The key words used in the search included “frontotemporal lobar degeneration,” “frontotemporal dementia,” “Pick disease,” “progressive non-influent aphasia,” “semantic dementia,” “primary progressive aphasia,” and intervention-specific terms such as “China” and “Chinese.” Every paper relating FTD was reviewed, and the reference lists were also examined to identify possible missed cases. No language restriction was applied.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Cases were included in this analysis if patients satisfied the clinical diagnosis criteria of any of the three variants of FTD [12]. For bvFTD, these include (1) insidious onset and gradual progression; (2) early decline in social interpersonal conduct; (3) early impairment in regulation of personal conduct; (4) early emotional blunting; (5) early loss of insight. Patients met the criteria for semantic dementia if they exhibited (1) insidious onset and gradual progression; (2) a language disorder characterized by empty fluent speech, loss of word meaning, or semantic paraphasias; (3) a perceptual disorder characterized by impaired recognition of familiar faces or object identity; (4) preserved perceptual matching and drawing reproduction; (5) preserved single-word repetition; (6) preserved ability to read aloud and write to dictation orthographically regular words. Finally, patients meet the criteria for PNFA if they had (1) insidious and gradual progression and (2) nonfluent spontaneous speech with at least one of agrammatism, phonemic paraphasias, or anomia. Patients were diagnosed as probable or possible amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) according to the El Escorial criteria [38]. Our exclusion criteria were if (1) the article had very limited information for FTD-related studies [39, 40]; (2) the patient was not Han Chinese ethnicity [41]. Duplicated cases were only counted once, if it appeared in several publications [42–45]. Overall, 49 cases from 25 publications were included in this report.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

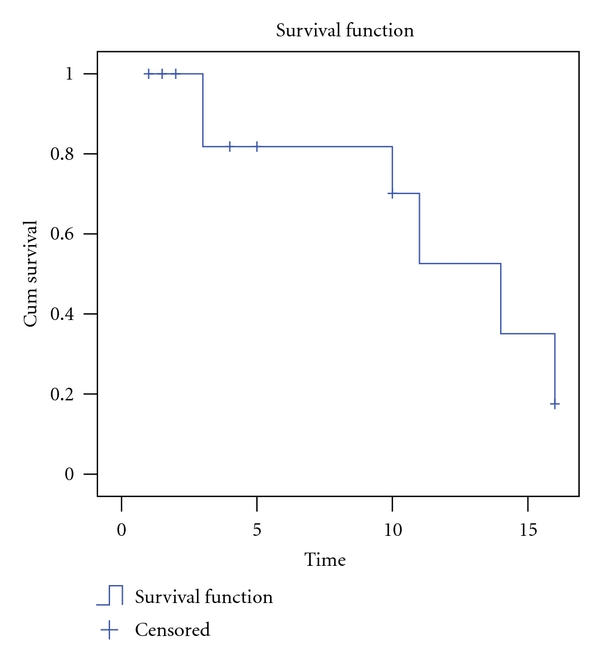

For each individual case of FTD, the variables collected included age, gender, ethnicity, family history of dementia, concomitant disorders, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, and neuropathological diagnosis. Descriptive analysis was performed to examine the distribution of demographic characteristics. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test, while ANOVA was used for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to assess the cumulative survival rate of FTD.

3. Results

3.1. Diagnostic Subgroups

From January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2010, 49 patients of Han Chinese descent were diagnosed as having FTD across Northern and Eastern China. The cases first presented to memory clinics or department of neurology (43/49); psychiatric clinics (3/49); GPs (general practitioners); others (3/49).

Overall, bvFTD was the most common diagnostic subgroup and accounted for 71.4% of all diagnoses (n = 35). PNFA was the second most common (n = 8), followed by SD (n = 6). Of the bvFTD patients, 17.1% (n = 6) and 20.0% (n = 7) were initially diagnosed possible ALS or Parkinsonian syndrome, respectively whereas none of SD or PNFA patients had a concomitant ALS or Parkinsonian syndrome.

3.2. Age of Onset and Family History

Age of onset ranged from 20 to the eighth decade. Patients with bvFTD tended to have a younger age of onset compared to patients with PNFA or SD, but this was not statistically significant as shown in Table 1 (F = 2.523, P = 0.096). Approximately 45.7% of bvFTD patients (n = 16), 37.5% of PNFA patients (n = 3), and 66.7% of SD patients (n = 4) were diagnosed before the age of 65. Overall, more than 47% FTD patients had the disease before 65. Seven bvFTD cases, but not from the other two groups, reported family histories.

Table 1.

Demographic variables by diagnosis.

| Variable∖subgroups | bvFTD | PFNA | SD | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE score at the initial assessment | 13.9 ± 6.7 | 15.3 ± 9.6 | 15.8 ± 10.7 | 14.7 ± 8.0 |

| Age at onset (years) | 53.8 ± 14.8 | 64.1 ± 10.1 | 63.8 ± 9.9 | 57.8 ± 13.8 |

| Male/sex | 16/35 | 6/8 | 3/6 | 25/49 |

3.3. Gender and Educations

Female patients comprised of 54.3%, 25%, and 50% of the bvFTD, PNFA, and SD subtypes, respectively. No significant differences in gender were demonstrated by crosstab chi-square analyses by sites and diagnostic subgroups (Fisher exact test, P = 0.387), although there appeared to be less females in the PNFA subgroup. Level of education varied greatly among patients with FTD, some were university graduates, and some were illiterate.

3.4. MMSE Score at First Visit

Only 19 of the 49 cases were presented with an MMSE score (9 with bvFTD; 6 with SD; 4 with PNFA group). A one-way analysis of variance showed no significant difference (13.9 ± 6.7; 15.3 ± 9.6; 15.7 ± 10.7) between diagnostic subgroups (F = 0.092, P = 0.91).

3.5. Neuropathological Diagnosis and Survival Curve Analysis

We found no reports of genetic screening. There are three neuropathological studies reporting a total of five FTD cases [14, 21, 46]. Table 2 summarizes the neuropathological diagnostic breakdown and demographic characteristics for the five cases.

Table 2.

Characteristics by neuropathological diagnosis.

| Neuropathological diagnosis | Age at onset (years) | Age at death (years) | Initial MMSE score | Family history |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) FTLD-τ | 60, 72 | 76, 86 | N/A, 8 | No |

| (2) FTLD-U | 58 | 61 | 22–30 | No |

| (3) FTLD without intracellular inclusions | 67, 43* | 78, 46* | N/A | No |

N/A = not available; *Ubiquitin immunohistology examination was not performed on this case (with possibility of FTLD-U).

Median survival of 35 bvFTD cases presented in this study was 14 years from symptom onset (Figure 1). The survival curve demonstrated that most cases would progress for 10–15 years from time of diagnosis till death.

Figure 1.

Survival curve of bvFTD in the present study.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to summarize demographic and clinical data from published cases in China according to the diagnostic criteria for FTD and its subgroups (bvFTD, PNFA, and SD). On the background of low diagnostic accuracy and lack of epidemiological data, this paper summarizes 49 cases from 24 articles and one small size retrospective study from multiple centers that demonstrated pathological features of FTD in China.

4.1. The Influences of Culture Background for Medical Service for FTD in China

The present study appeared to yield similar results compared to previous investigations from the west. BvFTD was the most common diagnostic subgroup and accounted for over half of all FTD diagnoses [6, 47]. SD and PNFA were less common and accounted for 12.2% and 16.3%, respectively. Interestingly, patients often favored neurology department or memory clinic over psychiatric clinic, although the first symptoms of FTD cases are frequently behavioral and psychiatric changes. This paradoxical phenomenon can be attributed to two potential factors. Firstly, families in the Chinese culture are often ashamed of psychiatric diseases, hence favoring seeking help in neurology clinics. Secondly, most specialists for cognitive disease are neurologists, and memory clinics or centers are generally run by neurology departments in China. Hence, the culture background may play an important role in the paradigm of delivering medical services to FTD patients in China, which is similar to Alzheimer's type dementia [48].

4.2. The Research History in Terms of FTD in China

The earliest clinical and neuropathological studies of dementia in China were by Tong and Wang in 1982 on Alzheimer's type dementia [49], and by Wang and her coworkers on Pick disease in 1993 [46]. The first confirmed case was a 93-year-old woman with ten-year history characterized by impairment of personal conduct and behavioral disorders with a positive family history. She died of acute respiratory failure, and autopsy results revealed typical Pick bodies. In retrospect, the earliest case might have been observed in 1960 but not recognised as such at the time [25]. Dr. Xu reported a 40-year-old male who presented with bizarre sexual behavior, as he bit off one third of his newly wed wife tongue on the first night of their wedding. He was referred to the psychiatric clinic, and a pneumoencephalography was performed with no abnormalities detected. He was suspected to have schizophrenia. Pneumoencephalography was repeated eight months later, revealing asymmetric frontotemporal lobe atrophy [25]. We suspect that FTD is not a rare disease in China, yet, to our surprise, there were only 49 FTD cases reported from China in the past 12 years. The overlap between FTD and Alzheimer's disease and psychiatric disorders, lack of neuropathological confirmation in most institutions in China, and the fact that clinicians are not fully aware of this disorder are the main causes for the underdiagnosis. Although brain MRI has been taken as a routine clinical examination for patients with dementia, most Chinese neurologists are short of neuropsychological training for FTD diagnosis.

4.3. The Current Features of FTD in China

Our study showed that features of FTD in China are largely similar to those reported in western countries with subtle differences [6, 38, 50]. As we gain more knowledge of FTD as a disease entity, we have observed that more FTD cases have been diagnosed compared to 20 years ago, and FTD has become one of most frequently diagnosed neurodegenerative dementias after AD in some memory clinics [51].

Similar to previous studies [6, 52], age of onset in FTD varied widely from the 20s to the 80s. Overall, 23 of the 49 cases had an age of onset at 65 years or younger accounting for 47% of the total. Patients with bvFTD appear to have a younger age of onset compared to patients with PFNA and SD. This is consistent with the average onset age of bvFTD, PFNA, and SD is 57, 65, and 59 from a joint British-Australian study [52].

Except in bvFTD (20% positive family history), family history does not appear to play an important role in PFNA and SD. Unfortunately, the education levels obtained for cases included in this study are ambiguous, as only the occupations are available but not the exact level of education received. Thus, we can only infer that the patients with FTD included a wide range, from professors to the illiterate.

The distribution of FTD across sexes appears roughly equal with some studies reporting a predominance in men although this has not been a consistent finding [6, 46, 53, 54]. Our study supported the equal sex distributions in bvFTD, but gender predominance in the other two subtypes could not be determined due to very small sample sizes.

Median survival in bvFTD in our study was 14 years from symptom onset which is consistent with other reports of 6–11 years [53–55]. ALS and parkinsonian syndrome can coexist with any of the FTD clinical variants but is most commonly associated with bvFTD [56, 57]. Our study found that 17% (n = 6) of the bvFTD patients also had possible ALS, whereas none of SD and none of PNFA patients had concomitant ALS. The bvFTD subgroup showed significant overlap with the atypical Parkinsonism associated with cortical basal degeneration (CBD).

Neuropathological diagnosis was carried out in 5 cases of bvFTD who showed gross atrophy of the frontal and anterior temporal lobes macroscopically. The neuropathological diagnoses included FTLD with tau-positive inclusions (FTLD-τ), FTLD with ubiquitin-positive and tau-negative inclusions (FTLD-U), and FTLD without tau-positive or ubiquitin-positive inclusions. The spectrums of neuropathological diagnosis are similar to previous studies [6].

4.4. The Progression of FTD Research in China

There is an increasing trend for FTD research in China in the past ten years. Unfortunately almost all research has focused on clinical aspects rather than neuropathology. Compared to Europe, North America, and Australia, studies of FTD in China are in a preliminary stage. Our review highlights the lack of neuropathological and genetic studies and of a unified clinical rating scale for FTD. For example, a myriad of single rating scales, including MMSE, Hasegawa Dementia Scale (HDS) [16, 31], Wechsler Adult Memory Scale (WAMS) [25], or the Chinese version of the revised Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE-R) [58] were employed for screening in different memory clinics, which made comparison between cases difficult.

Therefore, a crucial development will be the application of consistent cognitive and behavioral rating scales for studies of FTD. This should be supplemented by genetic screening, particularly for mutations of the MAPT and progranulin in FTD patients with a strong family history. Longitudinal clinical followup would achieve better management of FTD and provide potential neuropathological diagnosis. We recommend the establishment of a multicenter work group in China which, we feel, would be a more efficient approach to epidemiological and clinical studies in the future.

In conclusion, this paper provides preliminary data to aid the understanding of the current situation of FTD in China. This review highlighted the importance of establishing a standardised protocol across different clinical/medical research sites to form a large combined cohort, in order to facilitate the exploring of epidemiological, clinical, and biological features of FTD, hence ultimately improving clinical diagnosis accuracy and quality of life for patients with FTD in the world including China.

Authors' Contribution

R.-J. Ren and Y. Huang contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor John Hodges from Frontier (Frontotemporal Dementia Research Group), Neuroscience Research Australia for his valuable comments on this paper, and Mr. Ning Song from the University of New South Wales for English proof reading.

References

- 1.Tolnay M, Probst A. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update on clinical, pathological and genetic findings. Gerontology. 2001;47(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000052763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolnay M, Probst A. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration—tau as a pied piper? Neurogenetics. 2002;4(2):63–75. doi: 10.1007/s10048-002-0140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampathu DM, Neumann M, Kwong LK, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. American Journal of Pathology. 2006;169(4):1343–1352. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galimberti D, Scarpini E. Genetics and biology of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2010;3(2):129–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borroni B, Alberici A, Grassi M, et al. Is frontotemporal lobar degeneration a rare disorder? Evidence from a preliminary study in Brescia County, Italy. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;19(1):111–116. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IRA, et al. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the consortium for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathologica. 2007;114(1):5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinovici GD, Miller BL. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(5):375–398. doi: 10.2165/11533100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda M, Ishikawa T, Tanabe H. Epidemiology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2004;17(4):265–268. doi: 10.1159/000077151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou CE, Yaffe K, Pérez-Stable EJ, Miller BL. Frequency of dementia etiologies in four ethnic groups. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2006;22(1):42–47. doi: 10.1159/000093217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Katzman R, Salmon D, et al. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender and education. Annals of Neurology. 1990;27(4):428–437. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang ZX, Zahner GEP, Román GC, et al. Dementia subtypes in China: prevalence in Beijing, Xian, Shanghai, and Chengdu. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62(3):447–453. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang LN, Zhu MW, Feng YQ, Wang ZF, Jia JJ, Xie HG. Clinical, neuroimaging and neuropathology report of three cases with frontotemporal dementia. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2005;12:741–745. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao X, Cao BZ, Chang GF, Zhang Y, Jin S. Clinicopathological characteristics of frontotemporal dementia in one patient. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2004;8(19):3730–3731. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia JJ, Lu WP, Wang LN, Tang HC, Yin L. Diagnosis of Pick disease. Chinese Journal of Medical Imaging Technology. 2001;17:318–320. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JN. Variant Pick Disease in one patient. Journal of Clinical Psychosomatic Diseases. 2007;13:p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng HY, Wang B, Zhang D, Li XS. Diagnosis pick disease with MRI. Chinese Journal of Radiology. 2005;39:p. 1307. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma AJ, Zhang BS, Liu Y, Yin JZ. Imaging manifestations of two patients with frontotemporal dementia. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2006;39:128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu GY, Shen L, Wang ZY, et al. Significance of plasma von Willebrand factor level and von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease activity in patients with chronic renal diseases. Chinese Medical Journal. 2008;121(2):133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Liu B, Liu X, Chen ZG, Li NN, Luo XD. Functional MRI investigation of brain functional connectivity in resting-state of Parkinson’s disease patients. Chinese Journal of Medical Imaging Technology. 2009;25(6):989–992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin S, Zhao J, Jiang X. Clinical and pathologpcal studies on frontal lobe dementia. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2002;35(4):194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng X, Wu JJ, Guo QH, Lu JH, Dong Q. Dementia-amyotrophic lateral sclerrosis in one patient. Chinese Journal of Clinical Neurosciences. 2005;13:316–317. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng F. Pick disease in one patient. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine. 1999;19:p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu MN. Motor neuron disease complicated by frontotemporal dementia: a case report. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University. 2009;30(1):115–116. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan XF. Memory deficit, eccentric behavior, sexual hyperfunction—case discussion in behavioral Medical Branch of Shanghai Medicine Association. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 1999;11:185–187. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao F, Fan DS, Wang HL, et al. Survey of cognitive function in motor neuron disease. Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine. 2009;48(1):31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Zhang ZX, Yuan J, Wang JT, Qiao L. Clinical and imaging characteristics analysis of 14 patients with frontotemporal dementia. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2009;42:742–744. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang LH, Li XY, Fang YY. Frontotemporal degeneration complicated by motor neuron disease: one case report. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2010;36:567–568. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo QH, Hong Z, Fu JH, Yu H, Lv CZ. Semantic dementia: a study for a Chinese patient with severe left temporal lobe atrophy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;11:253–256. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo QH, Hong Z, Yu H, Lv CZ, Zhou Y. Study on clinical, cognitive and MRI fearures of patients with semantic dementia: report of 3 cases. Chinese Journal of Neuromedicine. 2004;3:363–365. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang DW, Zhang ZN, Song XL, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: one case report. Practical Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2009;6:154–155. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao J, Li F, Zhu CH, et al. Characteristics in neuropsychology and changes in cortex metabolism of non-fluency aphasia type frontotemporal dementia. Chinese Journal of Neurology . 2009;42:733–736. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Y, Zhang Y. Primary progressive aphasia syndrome: one case report. Chinese Journal of Geriatrics. 2003;22:p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang QW, Wang XJ, Lin JZ, Zheng WH. Primary progressive aphasia: one case report. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2009;35:314–315. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L. Primary progressive aphasia syndrome: one case report. Chinese Journal of Difficult and Complicated Cases. 2010;9:789–790. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao DX, Zhang T. Intracerebral image features of the patient with primary progressive aphasia: one case of nuclear magnetic resonance analysis. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005;9(40):142–144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen B, Ma Q, Ma Y. Primary progressive aphasia: a case analysis. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2002;35(3):162–164. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks BR, Antel J, Bradley W, et al. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1994;124, supplement:96–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao YM. Case report of mongolian medicine treatment on Pick disease. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy. 1998;31:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang GF, Wang LN, He SZ, Ji JG, Yao JH, Peng LW. Proteomic study of Pick’s disease. Chinese Journal of Neurology. 2006;39(2):96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang Z, Huang HY, Chen L, et al. Human fetal olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation for frontotemporal dementia in 1 case. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitative Tissue Engineering Research. 2007;11(20):4038–4040. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang YM, Wang YJ, Han ZZ, Shu H. Clinical report of a case of primary progressive aphasia. Chinese Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;27:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhan YM, Wang YJ, Guan XT, et al. MRI report of a case with primary progressive aphasia. Chinese Journal of Geriatric Heart Brain and Vessel Diseases. 2005;7:172–174. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang YM, Wang YJ, Zhou Y, Han ZZ, Shu H. Primary progressive aphasia: a case study. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2005;9(5):165–167. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang YM, Huang Y, Sun XJ, Han ZZ, Loy CT, Wang YJ. Clinical and imaging features of a Chinese-speaking man with semantic dementia. Journal of Neurology. 2008;255(2):297–298. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang LN, Liu ZY, Zhao Y, Wang CD. Neuropathological diagnosis for Alzheimer disease and Pick disease (three brain only autopsy cases report) Chinese Journal of Geriatrics. 1993;12:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lough S, Hodges JR. Measuring and modifying abnormal social cognition in frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(2):639–646. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheng B, Law CB, Yeung KM. Characteristics and diagnostic profile of patients seeking dementia care in a memory clinic in Hong Kong. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(2):392–400. doi: 10.1017/S104161020800817X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tong QJ, Wang ZY. Alzheimer type dementia: a case report. Chinese Journal of Geriatrics. 1982;1:246–247. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;58(11):1615–1621. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo QH, Lv CZ. Aetiology of memory impairment in China. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2004;2:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodges JR, Davies RR, Xuereb JH, et al. Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Annals of Neurology. 2004;56(3):399–406. doi: 10.1002/ana.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61(3):349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, et al. Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65(5):719–725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173837.82820.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rascovsky K, Salmon DP, Lipton AM, et al. Rate of progression differs in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65(3):397–403. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171343.43314.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lomen-Hoerth C. Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2004;17(4):337–341. doi: 10.1159/000077167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merrilees J, Klapper J, Murphy J, Lomen-Hoerth C, Miller BL. Cognitive and behavioral challenges in caring for patients with frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 2010;11(3):298–302. doi: 10.3109/17482961003605788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mioshi E, Hodges JR. Commonly used cognitive screening instruments for diagnosis of dementia. Journal of Internal Medicine Concepts & Practice. 2009;4:247–250. [Google Scholar]